Over the last 20 years, the inclusion of women and ethnic minorities in national parliaments has increasingly been seen as an indicator of the strength of democracy in established democracies and as a sine qua non of democratization in the developing world. Much has been written about the growing numbers and influence of women members of parliament (MPs) in the legislatures of the world (for example, see Baldez Reference Baldez2003; Krook Reference Krook2009; Wolbrecht, Baldez, and Beckwith Reference Wolbrecht, Beckwith and Baldez2008). In 2012, the Inter Parliamentary Union identified 7,443 female members of national lower houses (20% of the total). A similar literature is emerging on the existence and influence of ethnic minority MPs in national legislatures. One of the largest surveys to date of minority MP presence covers 50 nations and identifies more than a thousand MPs with an ethnic minority background (see Reynolds Reference Reynolds2006). Such descriptive (sometimes called “passive” or “symbolic”) representation does not necessarily imply that the group members vote together or that individual representatives see themselves as primarily “women MPs” or “minority MPs.” But without some visible inclusion of the faces and voices of the historically marginalized, it is unlikely that the interests of such groups will be at the forefront of decision makers’ minds.

The literature on openly lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) MPs in national parliaments is undeveloped. Although there have been important studies of their presence in individual national parliaments (see Rayside Reference Rayside1998 on Britain, the United States, and Canada) as well as analyses of gay legislators in U.S. state legislatures (see Haider-Markel Reference Haider-Markel2007; Reference Haider-Markel2010; Haider-Markel, Joslyn, and Kniss Reference Haider-Markel, Joslyn and Kniss2000) there is very little cross-national research on the existence and influence of open LGBT MPs in national parliaments. Although the number of these legislators is dwarfed by the number of female and minority MPs, analyzing the sexual orientation aspect of descriptive representation is nevertheless important. First, scholars, democracy advocacy groups, and good governance promoters recognize that inclusive legislatures are better at crafting stable societies and, more broadly, “just” policy prescriptions (see, for example, Hartzell and Hoddie Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2003; Norris Reference Norris2008). Sexual orientation diversity has begun to be highlighted as a significant and component part of manifest inclusion,Footnote 1 but to date, scholarly attention to the phenomenon lags behind. The mainstreaming in academic and public policy research of the role of gay politicians will give rise to a better understanding of the strategies and mechanisms that facilitate the creation of inclusive legislatures. Second, “gay issues,” whether they involve same-sex marriage or partnership rights, are increasingly a wedge issue in election campaigns around the world. Homophobia is a visceral weapon for politicians as far apart as Zimbabwe, Malaysia, and the United States. As such issues become more central to national campaigns, it can be argued that the need to represent the community at risk becomes more pressing. This article seeks to answer three interrelated questions: How many “out” LGBT legislators have there been in national parliaments, what explains the cross-national variation in LGBT legislative presence, and what is the relationship between the election of gay legislators and progressive policy that treats gay, straight, and transgender citizens equally?Footnote 2

This work rests on the theory that the presence of LGBT legislators in a national assembly will make more likely the passage of laws that heighten equality on the basis of sexual orientation, and I present strong evidence to suggest that to be the case. The models described later in this article demonstrate that the number and presence of LGBT MPs are consistently associated with enhanced national gay rights. This effect holds even after accounting for social values (tolerance of homosexuality) and a variety of other factors. Although these findings echo the evidence that shows how the descriptive representation of women and ethnic groups can enhance protections for those communities of interests, LGBT MPs seem distinctive in the power of their presence. In most countries female voters are large in number and geographically dispersed, and they rarely coalesce around a single party. Women in elected office may advocate for their gender, but do so within the constraints of party politics and other interests. LGBT voters are also usually geographically dispersed and can split across ideologies and parties. Although ethnic minority voters may be concentrated enough both geographically and politically to elect candidates of choice without the support of others, LGBT voters almost never have that opportunity.

Studies have shown that female legislators may need a critical mass of legislators to be influential (Bratton Reference Bratton2005: Grey Reference Grey2002), but enhancing gay rights through gay MPs does not necessarily require such a critical mass. Fewer gay MPs may have an equal or greater impact than their female or minority colleagues. The great difference between women, ethnic minorities, and LGBT individuals as political blocs is that of their visibility. As a community LGBT people around the world have been marginalized, demonized, and driven underground for most of modern history. Unlike some marginalized communities, gay and transgender people are rarely geographically segregated or separated from their societies, but they lack visibility. Their absence as a legitimate, visible, and mainstream interest group has fed distrust and discrimination based on the fear generated by unfamiliarity. The impact that out gay elected officials have on the voting behavior of their colleagues and resulting public policy may be higher than that of female and minority MPs precisely because their visibility in office is such a new and, in some cases, jarring phenomenon.

That new-found legislative presence and political viability feed into a climate of transformation of values. First, individual legislators can nurture familiarity and acceptance from their straight colleagues. As I describe in detail later, there is strong evidence that, in general, heterosexuals become more supportive of gay rights when they know someone who is gay. Globally there are billions of people who do not realize that they know someone who is gay— perhaps a family member, friend, or colleague at work. Second, out LGBT MPs are symbols of social progress that reinforce new norms of (voting) behavior. Finally, gay MPs can be legislative entrepreneurs—advocating, setting agendas, and building alliances with straight legislators to put equality issues on agendas and marshal majorities in their favor.

THE NUMBERS OF OPEN LGBT ELECTED OFFICIALS

To gauge whether LGBT MPs affect public policy one first needs to quantify their presence cross-nationally. I analyzed the legislatures of 96 nation-states between 1976 and 2011. Such data had not been systematically gathered or presented before, and two issues of data collection arose: How does one identify openly gay MPs, and what type of legislation serves to indicate the attitude of the state toward sexual orientation equality? To address the first issue, I used a simple rule of thumb: I included MPs only if at some point they publicly stated or acknowledged that they are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender. They may have done so through the media, campaign literature, biographies, or personal websites. I did not include politicians who denied that they were gay. However, MPs who acknowledged their sexual orientation after being outed while in office were included because they had made a clear statement. I gathered data on MPs in national legislatures by consulting a number of sources, including country experts and experts in the LGBT field, politicians’ personal websites, and media reports. This method undoubtedly undercounted the actual number of LGBT MPs, but this research is focused explicitly on openly LGBT MPs.

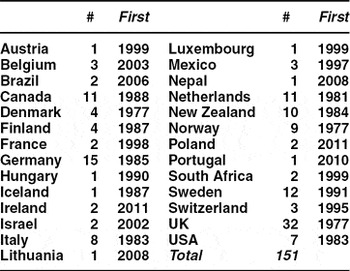

Of the 96 nations analyzed, I identified a total of 151 LGBT MPs elected to the national assemblies of 27 countries at any time between 1976 and 2011; there is no evidence to suggest that any other nations elected out LGBT MPs.Footnote 3 Of these openly gay MPs, there were 111 gay men, 32 lesbians, 5 bisexuals, and 3 transgender (see summary in Table 1 and full details in the Online Appendix).Footnote 4 In 2011, there were 96 MPs in office in 24 countries (72 gay men, 19 lesbians, 4 bisexual, and 1 transgender MP).Footnote 5 The largest number was 24 serving in the British House of Commons, and the largest percentage was 6% in the New Zealand parliament. The number of out LGBT MPs has increased substantially over the last 40 years, but the total numbers remain small. It was difficult to determine who was the “first” openly gay MP.Footnote 6 Marilyn Waring was elected as an MP in New Zealand in 1975, was outed by a newspaper in 1976, and, on the advice of her party leader, refused to comment. Maureen Colquhoun was a British MP between 1974–79, came out as a lesbian in 1977, and was defeated in 1979. Coos Huijsen was elected to the Dutch parliament in 1972 and reelected in 1976 and 1977, but did not come out until 1977.

TABLE 1. LGBT Members of Parliament 1976–2011 (National Assembly)

The number of gay MPs has increased over time: there were 6 MPs in 1983, 8 in 1988, 35 in 1998, 59 in 2003, 78 in 2008, and 96 in 2011. The proportion of gay men to lesbians—about three to one—has remained fairly constant over time. LGBT MPs have also been overwhelming from the majority ethnic group within their nation-state. Of the 151 openly gay MPs in the dataset only 7 were ethnic minority LGBT MPs – Jani Petteri Toivola (Finland) is of Kenyan and Finnish descent, Tofik Dibi is a Dutch Muslim of Moroccan descent (Netherlands), Charles Chauvel (New Zealand) is of Tahitian ancestry, and Louisa Wall and Georgina Beyer (New Zealand) are Maori, whereas the two South African MPs are both white South Africans of European ancestry.

Forty of the MPs were not out at the time of their first election to parliament, but came out during their time in office; the other 111 were out when first elected. The incidence of out candidates being elected has increased dramatically over time. From 1976–99, when 65 LGBT MPs were in office, only 31 (48%) were out when first elected. After 1999, 80 of the 86 (93%) MPs in office were out when elected.

The vast majority of LGBT MPs have been elected in the established democracies of Western Europe, North America, and Australasia; in 2011, 87 of the 96 were in office in these three regions. Of the remaining LGBT MPs, three were from Central/Eastern Europe, two from Africa, two from Latin America, and one each from the Middle East and Asia. Austria, Hungary, and Portugal have had gay MPs in the past, but none in 2011. Three openly gay individuals have become prime minister: Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir in Iceland in February 2009, Elio Di Rupo in Belgium in December 2011, and Per-Kristian Foss briefly as acting prime minister of Norway in 2002. Since 1997 there have been 27 LGB cabinet ministers—22 men and 5 women—in 17 countries, and 26 senators (or lords/barons) have served in the upper legislative chambers of 10 countries.

EXPLAINING DIFFERING LEVELS OF LGBT CANDIDATE SUCCESS

If the presence of open LGBT officeholders does dramatically move the needle on progressive law, it is important to determine what factors facilitate and hinder the election of openly gay candidates. Although there is evidence that the marginalization of women and ethnic groups has parallels with that of sexual orientation minorities, the nature of political mobilization and appropriate remedies to address such exclusion for each of the communities can be quite different. As Htun (Reference Htun2004) notes, women usually are dispersed across territory and across partisan divisions, whereas ethnic groups can be geographically concentrated and are more likely to vote as a bloc for a political party. For Htun this dispersion or lack of it affects both potential remedies and the ultimate goal of group representation. Women are more likely to seek (and achieve) representation through quotas and list proportional representation systems; however, once they have power, they “realign themselves as a category,” and their group identity “tends to weaken and dissipate.” In contrast, ethnic minorities seek group rights that are “reinforcing rather than self-cancelling” and lobby for reserved seats to have their “particularism recognized and legitimized” (Htun Reference Htun2004, 451).

In theoretical terms, are LGBT communities similar to women, to ethnic groups, or to neither? Like women, LGBT citizens are geographically and ethnically dispersed, but unlike women, they do tend to vote for parties that are sympathetic to their group's needs. LGBT representatives may cut across partisan lines in many countries, but once a significant number of LGBT MPs are elected they are likely to continue to promote policies that are, to some degree, based on their sexual orientation identity. In terms of remedies for underrepresentation, LGBT groups are perhaps more akin to ethnic groups in requiring reserved seats, but they have never received such recognition and gay MPs have been elected in many different electoral systems.

A variety of variables could account for the differing levels of electoral success of openly gay candidates for national office, and explaining electoral success helps us better understand what drives the relationship between descriptive and substantive representation. On the institutional level, political party ideology is an important variable affecting candidate selection and placement; the type of electoral system is a key determinant of electoral success. Historically, left parties have been more likely to have ideologies rooted in the protection and promotion of marginalized communities, whereas socially liberal parties have been more likely to be tolerant of different sexual orientations. We know that electoral systems can shape the access that minorities have to elected office. Previous studies have found significant links between proportional representation and district size and the probability of ethnic minority and female success (for summaries of the literature see Reynolds Reference Reynolds1999; Reference Reynolds2006; Reference Reynolds2011). Thus, the electoral system also should affect the electoral success of representatives of a marginalized and geographically dispersed community like LGBTs.

Sociocultural variables such as the level of social acceptance of homosexuality and the religious orientation of the greater society also could have an impact on the electoral success of openly gay candidates. The higher the acceptance of sexual diversity among the population as a whole, the more likely it is that openly gay candidates will be selected and elected. In much of the developed world, gay rights have been incrementally gathering steam since the late 1980s, tracking a growing public acceptance of homosexuals. But the dynamics of social acceptance are not simple. As Adam (Reference Adam2003) notes, for a time the United States bucked the progressive trend with the striking down of existing equality laws in cities and the emergence of the “Defense of Marriage Amendment” (DOMA) movements that sought to block future attempts to expand marriage rights to same-sex couples. Yet Adam does not consider this “American exceptionalism” a symptom of persistent or indeed growing intolerance of gay people. He points to the way in which regional clusters of states and politicians have pressed for gay equality while DOMA advocates gained ground elsewhere (Adam Reference Adam2003). Similarly, Rayside (Reference Rayside2008, 4) describes how American local and state governments, courts, and businesses have acted as “pioneers in responding favorably to [lesbian and gay] activist pressure,” even as a backlash against some of these advances washed over the polity from 2004 onward. Finally, one might hypothesize that the level of democracy also influences the hurdles placed in front of the election of openly gay political candidates. Established democracies are more likely to be based on a civil rights foundation, with higher levels of social tolerance and open LGBT activism.

The data partially confirm these presumptions, but the evidence on what leads to the electoral success of LGBT MPs leaves significant space for the impact of the legislators themselves on public policy. Figure 1 demonstrates that the majority of open LGBT MPs have been members of left or green parties. In 2011, 51 of the 96 gay MPs were members of Social Democratic, Socialist, Communist, or Green parties. Proportionately, Green parties have elected more LGBT MPs than any other political movement over the last 40 years. However, a surprisingly large and growing number of MPs have come from conservative parties. In 2011 there were 22 (23%) Conservative/Right MPs, almost as large as the cohort of centrist/liberal MPs, demonstrating the most rapid growth among any political ideology. In the United Kingdom, the burgeoning number of LGBT Conservative MPs rests in part on Prime Minster David Cameron's decision to promote a number of out candidates in the 2010 British general election.Footnote 7 Certainly, left or socially liberal parties are more likely to have ideologies sympathetic to gay inclusion, but voter hostility to gay equality (and party leadership reticence) still precludes mainstream parties from putting up substantive numbers of openly gay candidates. As the total number of gay MPs grows, however, we might expect a higher proportion to come from left or liberal parties.

FIGURE 1. Political Ideology and LGBT MPs.

Political history suggests that the type of electoral systems matters greatly to the chances of openly gay candidates being elected. For instance, in the early 1970s, Harvey Milk attempted twice to win election to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, but under the “at large” (bloc vote) system used, he was unable to attract enough votes citywide to be elected. However, in 1977, when the election system was changed to one of single-member districts, Milk won election from a district centered on the Castro and Haight-Ashbury neighborhoods. List proportional representation (PR) systems are the most inclusive of women and minority candidates and tend to give political parties a means of bypassing some of the prejudices of the electorate, by putting minority candidates on their lists. These candidate lists are either closed (thus unalterable by the voters) or open to some degree, but are often difficult for the electorate to reorder. It is true that when ethnic groups are heavily concentrated geographically they are able to win seats in single-member district systems, but first-past-the-post (FPTP) systems give an incentive for parties to run lowest common denominator candidates, who are very often straight males from the dominant ethnic group. Thus women and gay candidates have a particularly difficult time winning FPTP seats unless some special mechanisms are in place (e.g., reserved quota seats or affirmative action districting).Footnote 8 On average, about 10% fewer women are elected under FPTP than under list PR systems (see Reynolds Reference Reynolds1999).

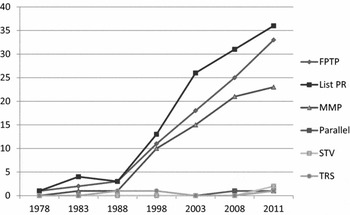

However, the expectation that LGBT members are clearly more likely to be elected from list PR systems than from majoritarian systems is confounded by the data as shown in Figure 2. The number of gay MPs elected under single-member district systems has tracked closely the number elected by the list PR system. In 2011 there were only three fewer FPTP gay MPs than list PR MPs. It is true that if one aggregates all PR systems – list, mixed member proportional (MMP), and the single transferable vote (STV) – then more LGBT MPs are elected by PR methods, but the theory that “hiding” on a list of candidates is the only way for openly gay candidates to be elected is not borne out by the data. The relative success of gay MPs in New Zealand, Germany, Italy, Hungary, and Mexico indicates that MMP systems produce the highest proportion of gay MPs.

FIGURE 2. Electoral Systems and LGBT MPs.

Is there evidence to suggest that the majority of gay MPs are elected from relatively safe seats? If one takes marginal seats to be those single-member districts held with less than a 5% majority, just more than one-third of first-time successful out candidates won marginal seats (1993–2011), and the introduction of a gay candidate was not the cause of the competitiveness of the race. Thus, it is not clear that the seats won by open LGBT MPs are more likely to be “safe” party seats. Last, are single-member district LGB MPs elected only in urban and more liberal areas? To the contrary: Only 21 of the 62 LGB MPs were elected from urban districts, whereas 41 were elected from predominantly rural or suburban ones. Even among those MPs from nonurban areas who were not out when first elected and subsequently acknowledged their sexual orientation, the vast majority successfully defended their rural district seats.

Except for Nepal, all the countries where LGBT MPs have been elected were “democracies,” but the bivariate correlation between the percentage of gay MPs and the POLITY IV score for democracy has never been high (.18 in 1998, .29 in 2003, .28 in 2008, and .29 in 2011). Most of the 27 countries with openly gay MPs are long-established democracies; the exceptions are South Africa, Mexico, Brazil, and Lithuania whose democratic regimes may be too young to be considered consolidated. However, having open LGBT MPs is not inevitable, even in a progressive and democratic polity. Most striking are the cases of Andorra, Colombia, and Spain, which have high scores on the LGBT law scale (see the later discussion), but have never had openly gay MPs in their national assemblies. Unsurprisingly, LGBT MPs were found more often in countries where public opinion leaned toward the “homosexuality is justifiable” end of the scale, but Brazil, Mexico, Lithuania, Poland, and South Africa had gay MPs, even with most voters categorizing homosexuality as unjustifiable.

The OLS models for 2003, 2008, and 2011 (see Table 2) provide clearer evidence for what suppresses the number of gay MPs than for what facilitates their electoral success. In 2003 and 2008 the percentage of gay MPs was best predicted by social attitudes to homosexuality, but the raw number of gay MPs was only predicted by social attitudes in 2003 and not at all in subsequent years. The attitude effect appears to be usurped by the positive effect of European Union membership in 2008 and 2011, although this positive effect is not present for EU members in 2003.

TABLE 2. LGBT MPs as Dependent Variable

Baselines: left government, FPTP System, Protestant.

*p < .1; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

The variables suppressing the number of gay MPs in a national legislature are more obvious. Right-wing governments tend to be associated with fewer LGBT MPs than left-wing governments in 2003 and 2011, but that effect may wane as more established socially liberal but economically conservative political parties promote gay candidates in Europe. As noted earlier, the electoral system seems not to affect the election of gay MPs clearly in the way hypothesized. In 2003 the PR system was unexpectedly correlated with a suppression of the number of out LGBT MPs, but in 2008 and 2011 that correlation was reversed, with the PR system being associated with a slightly increased chance of having an LGBT MP. The religious orientation of the state is often significant. When compared to a baseline of Protestantism, fewer LGBT MPs are associated with Catholicism, Eastern Orthodox, and “other” religions, and Islam suppressed the number in 2008 and 2011 (but not in 2003).

LEGAL EQUALITY AND LGBT REPRESENTATION

There is clear evidence to suggest that the inclusion of marginalized groups is correlated with policy benefits for that group. Summarizing the gender representation literature, Reingold notes that a “clear empirical link” has been established “between women's descriptive and substantive representation” (2008, 128). The causal links may sometimes be murky, but women in office are more likely to take liberal positions, support feminist proposals, and take the lead on women's issues. Thus, their presence in legislatures leads to a greater likelihood of “women-friendly” policies being adopted (Bratton and Ray Reference Bratton and Ray2002; Crowley Reference Crowley2004; Saltzstein Reference Saltzstein1986; Reingold Reference Reingold, Wolbrecht, Beckwith and Baldez2008). Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler find that descriptive representation increases legislative responsiveness to women's policy concerns and legitimizes the body in the eyes of many women. The levels of representation are highly determined by the type of electoral system (Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler2005). Similarly, in the realm of ethnic politics the election of black and Hispanic state legislators in the United States has produced policy outcomes that benefit the communities represented (Bratton and Ray Reference Bratton and Ray2002; Bratton and Haynie Reference Bratton and Haynie1999; Eisinger Reference Eisinger1983; Preuhs Reference Preuhs2007; Saltzstein Reference Saltzstein1989).

Research on openly lesbian and gay officials in American state legislatures, pioneered by Donald Haider-Markel, mirrors the findings for women and ethnic minorities. Smith and Haider-Markel (Reference Smith and Haider-Markel2002) and Haider-Markel (Reference Haider-Markel2007) show that increased LGBT representation is associated with the adoption of policies that benefit LGBT people. Haider-Markel, Joslyn, and Kniss (Reference Haider-Markel, Joslyn and Kniss2000) find that even a small number of openly gay legislators has a positive effect on the adoption of domestic partner benefits. This effect persists above and beyond those of ideology, interest group strength, and public opinion. Moreover, higher numbers of LGBT legislators increase the likelihood of laws that ban discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Although these studies also found that the presence of LGBTs in public office can heighten a legislative backlash against gay rights, overall, the presence of openly gay legislators has produced a positive net result for the LGBT community (Haider-Markel, Reference Haider-Markel2007). Haider-Markel (Reference Haider-Markel2010) presents qualitative narratives from California, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Oregon, Virginia, and the state of Washington that describe LGBT legislators playing leading roles in promoting and advocating for bills that advance LGBT civil rights. Such legislators described themselves as much as educators as policy makers. He bolsters this qualitative evidence with a quantitative analysis of pro-LGBT and antidiscrimination bills offered in U.S. state houses between 1992 and 2007: “Even controlling for other factors, such as state and legislative characteristics, higher LGBT representation in state legislatures does lead to greater substantive representation in terms of LGBT related bills introduced and adopted” (2010, xii).

How might descriptive representation lead to substantive policy change when the number of LGBT legislators is so small? Critical mass theory posits that the number and proportion of minority group legislators have to reach a certain level before significant policy impacts are felt. Grey (Reference Grey2002) and Saint-Germain (Reference Saint-Germain1989) place that threshold at 15%. Yet as Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967) notes, the mere presence of marginalized community representatives in a legislature is a significant, if still symbolic, sign of tolerance. Bratton (Reference Bratton2005) and Crowley (Reference Crowley2004) find that the presence of even a small number of “token” women makes a significant difference to public policy issues that primarily affect women. Indeed, Bratton (Reference Bratton2005, 121)argues that “women serving in legislatures with little gender balance are actually more successful relative to men than their counterparts in more equitable settings.” This suggests that the very nature of a “token” legislative insurgency enhances the influence of the group seeking policy change.

There is evidence that familiarity breeds tolerance (see Haider-Markel Reference Haider-Markel2010; Lewis Reference Lewis2011; Smith and Haider-Markel Reference Smith and Haider-Markel2002). The presence of minority members in a legislature aids in breaking down intolerance and in building alliances that cut across preexisting cleavages within society. Openly gay MPs sometimes act as advocates for “gay issues,” but they almost always must build alliances with heterosexual allies because they have never been numerous enough to act as a voting bloc with leverage. They can be legislative entrepreneurs who help set agendas and educate their colleagues on related issues (see Haider-Markel Reference Haider-Markel2010). Even unsuccessful campaigns for office may assist in creating a more positive environment for the passage of progressive law. Wald, Button, and Rienzo (Reference Wald, Button and Rienzo1996) find that antidiscrimination policies were more likely in U.S. cities where open LGBT politicians had run for office but lost. Lewis and Pitts (2009) find that American states with gay rights laws have higher numbers of partnered gay and lesbian employees than the regular workforce, but the direction of causality is unclear.

In addition to representation, several sociopolitical variables have been suggested to help explain the passage of gay-friendly legislation. One would expect the level of societal acceptance of homosexuality to affect the scope degree of progressive LGBT law. In those countries where acceptance of homosexuality is high and a majority of the electorate supports same-sex marriage and adoption rights (e.g., Sweden, the Netherlands, and Iceland), advocating equal rights for LGBTs should be a vote-winning strategy for any political party, which will feel pressure to respond to public opinion. Frank and McEneaney (Reference Frank and McEneaney1999) and Kollman (Reference Kollman2007) note the impact that LGBT human rights advocacy groups have had on the diffusion of progressive same-sex legislation around the world. The openness of local policy makers to influence by such transnational networks is conditioned by the social attitudes of citizens and the perceived legitimacy of international norms. Diffusion of these new “human rights norms” occurs through networks of governmental actors, judges, legislators, and bureaucrats (see Greenhill Reference Greenhill2010; Slaughter Reference Slaughter2004), as well as through nongovernmental activities (see Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1999). In EU member states, antidiscrimination legislation is mandated by the Treaty of Amsterdam (1999), which prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation in certain fields. The statistical analyses in Table 3 show that EU membership is a significant predictor of enhanced gay rights in 2003 but not in 2008 or 2011, implying that the Treaty of Amsterdam had an initial impact that waned over time.

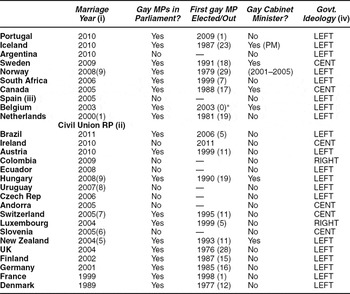

TABLE 3. Marriage and Civil Unions/Registered Partnerships

Notes: (i) Year 2008(9) year passed (year enacted).

(ii) RP = registered partnership.

(iii) Jeronimo Saavedra Acevedo, Spanish MP (1977–96) did not come out until 2000.

(iv) Government (executive) ideology at time of marriage/civil union legislation.

* Elio Di Rupo, the prime minister of Belgium in 2011, was in the National Assembly from 1987–89 but was not out at that time. After serving in other high-level positions, he returned to parliament in 2003.

The analysis in the remainder of this articles tests this hypothesis: The more open LGBT MPs there are in parliament, the more progressive a nation's legislation will be when it comes to issues of gay rights. I hypothesize that gay MPs increase the likelihood of progress toward legal equality, play a role in developing tolerance, and create an environment more conducive to the election of gay MPs. As the election of a gay MP becomes less jarring, gay rights become sequentially more likely and social attitudes more progressive. To test this theory, I first examined the specific relationship between gay MPs and gay marriage/civil unions laws and then used a series of cross-sectional regressions to assess the impact of gay MPs on broader policy issues, measured through a cumulative score of the national law in relationship to six areas relating to LGBT issues. Along with the LGBT MP variable, I included control measures for (i) social attitudes (a society's tolerance of homosexuality as measured by the World Values Survey [WVS] and Pew Global Attitudes Survey), (ii) level of democracy (as measured by POLITY IV on a 21-point scale ranging from −10 [hereditary monarchy] to +10 [consolidated democracy]), (iii) development (the annual United Nations Human Development Index), (iv) European Union membership (yes or no by year), (v) government type (left, center, or right), and (vi) electoral system (plurality-majority, semi-proportional representation, or proportional representation).

To what extent do openly gay legislators affect public policy in areas of legislation that directly affect the LGBT community? A variety of elements may contribute to the passage of laws providing equal rights and protections for gay men, lesbians, and transgender individuals (see M. Smith Reference Smith2008). To delve into the relationship between the presence of gay legislators and progressive law I collected data relating to six key legal areas:

-

1. Are same-sex acts between consenting adults legal?

-

2. Are same-sex couples allowed to marry or form civil unions/partnerships?

-

3. Can same-sex couples and gay individuals adopt children?

-

4. Are there national/federal laws against discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation?

-

5. Is homophobia a distinct category of hate crime law?

-

6. Does the nation-state ban gay people from military service?Footnote 9

For each country, I generated a summary score of sexual orientation equality policies, with higher values indicating more equality in laws according to these six elements. Each variable represented a distinct legal right/protection or denial of a right. If same-sex relationships were illegal under the law, the country scored −1; if they were legal, the country scored 0. If a country offered full marriage rights to same-sex couples, it scored 1; if civil unions or registered partnerships were offered, it scored 1; if neither was available, the score was 0. Child adoption rights scored 1, partial rights scored 0.5, and no rights scored 0. National laws against discrimination scored 1; no laws scored 0. If sexual orientation was a part of hate crime law, the country scored 1; if it was not it scored 0. Finally, if LGBTs were banned from the military, the country scored -1; if they were not, the score was 0. I summed the six scores to create a single indicator of LGBT rights. The scores ranged from a possible −2 to 6.Footnote 10

I coded the 96 countries for which data (primarily measures of social tolerance) were available: 27 have or have had in the past openly LGBT MPs and 69 had not. The highest equality law scores were achieved in 2011 in Sweden and the Netherlands (who received a maximum score), with Belgium, Canada, Iceland, Norway, South Africa, and Spain close behind. The most homophobic legal constructs (where there are no gay rights and homosexuality is illegal) were in Algeria, Bangladesh, Egypt, Lebanon, Malaysia, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Tanzania, Trinidad and Tobago, Uganda, Uzbekistan, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, although de facto practice in the treatment of LGBT persons varies across these cases (other countries demonstrate similarly oppressive laws but they are not in my dataset). The equality law scores simultaneously demonstrate the advances that gay rights have made around the world and the continuing chasm between the rights of heterosexual and LGBT people. In 2003 the average score of all cases was 0.47 (on the −2/6 scale); in 2008 it had risen to 0.98, and by 2011 it was 1.18. The largest increase in scores between 2003 and 2011 occurred in Andorra, Argentina, Brazil, Serbia, and Uruguay, even though other countries had higher overall scores. In my dataset the overall LGBT legal rights score did not decline in any country between 2003 and 2011, increased in 48 nations, and stayed the same in the other 48.

Most progress has been achieved in laws that ban discrimination in employment/services. In 2003 only 22 of the 96 countries had such provisions on the books, but by 2011 that number had more than doubled to 47. In 2003 same-sex couples were only allowed to adopt children in 5 countries, but by 2011 they were allowed to do so in 17. There has been less dramatic progress in the passage of hate crime laws: 15 countries had such laws in 2003, compared to 20 in 2011. Last, in 2003, 27 countries allowed LGBT citizens into their military forces, whereas 24 nations banned them from serving. Eight years later, the comparable figures were 36 and 21.

In 2003 only 2 nations recognized gay marriage (Belgium and the Netherlands), but by the end of 2011, 10 nations offered same-sex marriage. In the United States six states had gay marriage laws, along with the District of Columbia and two Native American tribal jurisdictions (California's law was struck down by referendum in November 2008, but the state of Washington, Maryland, and Maine instituted same-sex marriage in December 2012 and January 2013). As of 2011 civil unions or registered partnerships were much more common, available (to some degree) in an additional 19 countries.

One must stress that significant constitutional or legal protections of gay rights do not guarantee that homophobia, hate, and discrimination aimed against LGBT people are wiped out in a society. South Africa most vividly illustrates this truism with strong constitutional protections overlaying a social order that continues to be deeply homophobic in many regards (see Hunter Gault Reference Hunter Gault2012). Nevertheless, legal and constitutional provisions pushing toward equality represent significant advances for gay rights in substance and symbolism.

In bivariate terms, I found a relationship between gay MPs’ presence and progressive law. The 27 countries who have elected at least one LGBT MP averaged 3.6 on the law scale in 2011, in contrast to the 69 nations with no gay MPs that averaged 0.3; in essence, nations with gay MPs have significant equality clauses in their laws, whereas those nations without gay MPs have virtually no gay rights. But does a nation implement progressive laws when its parliament includes a handful of dynamic and persuasive openly gay MPs? Or are we more likely to see openly gay MPs in a polity that has already demonstrated its commitment to equality through progressive laws that were initially promoted and passed by straight legislators? This question is partially addressed by an analysis of those countries in which same-sex marriage is legal in 2011.

Table 3 shows data on same-sex marriage and partnership laws, whether there were gay MPs in the legislatures that adopted the laws, and the length of time between the election of the first gay MP and the law being passed. Of the 10 countries with same-sex marriage on the books as of 2012, eight (except for Argentina and Spain) had openly gay MPs in their chambers at the time the law was passed. Those eight countries first elected a gay MP between 1 and 29 years prior to the legislative change (an average of 14 years between the first openly gay MP, either elected or to come out, and the passage of a gay marriage law). Of the 18 countries with civil union or registered partnership laws, 11 had openly gay MPs when their laws were passed or had a gay MP previously (an average of 12 years between the first openly gay MP and the passage of the law). These patterns are confirmed by the universe of countries that have had open LGBT MPs. Nineteen of the nations with openly gay MPs (before the passage of the law) passed same-sex marriage or civil union/partnership laws (70%),Footnote 11 whereas only 9 of the 69 countries without gay MPs (13%) have such laws.Footnote 12 In reality, the latter figure is even smaller for we know that among the remaining 97 member states of the United Nations that are not in my dataset none have elected gay MPs to their parliaments or have gay marriage/civil union laws. Thus the true figure is 5% (9/167). Thus, a country that has elected an LGBT member to parliament is 14 times more likely to have marriage equality or civil union/registered partner laws than a country without an elected gay MP. It is also the case that a country is more likely to have some type of same-sex marriage or partnership recognition if ideologically the government is left of center, with or without openly gay MPs. Thus full marriage equality is made more likely by a combination of left-leaning governments and openly gay MPs in parliament. In sum, the countries with the most progressive LGBT rights have had some level of gay representation for the longest time and continue to do so today. The variation across the 96 cases in my dataset has remained remarkably constant.

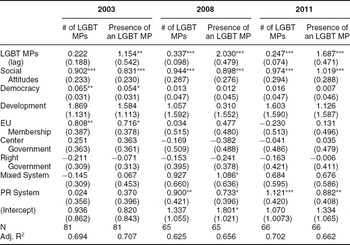

The multivariate OLS regression results discussed in this section consider the relationship between the presence of out LGBT MPs and the progressiveness of law (see Table 4). In each specification I offer results for both the number of gay MPs and a variable for presence of any LGBT MPs or not.Footnote 13 Given that it will take a while for the presence of open gay MPs to have an effect on their colleagues, the gay MP variables are lagged by one time period. Thus when the dependent variable is the law summary score for 2003 the MP data are from 1998, when the law summary score is for 2008 the MPs are from 2003, and when the law summary score is for 2011 the MP totals are from 2008. The independent variables are given for the same year as the summary law score dependent variable.Footnote 14 In all specifications (bar one) and time periods, having open gay, lesbian, bisexual, and/or transgender MPs is statistically significant and powerful in explaining the variation in national law on sexual orientation issues. This remains true when one controls for other plausible explanations.

For the simple yes/no variable, the presence of any LGBT MP in 1998 resulted in a 2003 law score 1.2 points higher on average than in countries without an LGBT MP, presence in 2003 implied that the law score is 2.0 points higher in 2008, and presence in 2008 resulted in a 2011 law score 1.7 points higher on average than countries without an LGBT MP, controlling for all other variables.Footnote 15 Table 4 also shows that having one additional LGBT MP in 2003 increased the 2008 law score by 0.3, and having one more in 2008 gave a 0.2 higher score in 2011, controlling for all other variables. There is a consistently strong and significant relationship between the presence of open LGBT MPs and the resulting passage of progressive laws.

The results demonstrate that a society's view of homosexuality also has strong and consistent effects on legal equality. Selection of the most appropriate statistical model depends on whether one theorizes that the relationship between the effects of LGBT legislators and changing social attitudes is additive or multiplicative. That is, does one expect that the presence of MPs and changing social views will act in a self-reinforcing cycle in which presence plus tolerance equals more progressive law (i.e., additive), or that the presence of a gay MP will have more (or less) of an effect on law when social attitudes are more (or less) tolerant (i.e., multiplicative)? If the expectation is multiplicative one should include an interaction term between the MP and attitudes variables. Although it is plausible that the presence of gay MPs will transform the views of a deeply homophobic society (and affect the voting behavior of their parliamentary colleagues) more than a gay legislator in an already relatively progressive polity, it is equally plausible that gay MPs will have more impact in a society receptive to change but not quite yet at the point of full equal rights. Thus, the models specified in Table 4 assume an additive relationship between these two independent variables. Running the models with an interaction term provides support for the belief that the relationship is additive and not multiplicative.Footnote 16 In 2003 and 2008, a change in social attitudes of one standard deviation increased the law score by 0.9 on average; in 2011 that corresponding change yielded an increase of 1.0.

TABLE 4. LGBT Law as Dependent VariableFootnote 20

Baselines: Left government; FPTP System; Protestant

*p < .1; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

NB: Lagged LGBT MPs = 1998 for 2003, 2003 for 2008, and 2008 for 2011.

The effects of democracy and EU membership are inconsistent. The effect of democracy was significant in 2003 but not in 2008 or 2011, and even in 2003 the effect was small. Going from a 0 to 10 in the POLITY scale, a huge jump, would only have had an impact of 0.5 in 2003, which is half of the effect of having an LGBT MP. The lack of a strong statistical association with democracy occurred because of the diffusion of some gay rights to middle ranking democracies and the fact that many full democracies continue to have limited equality at the national level on issues of sexual orientation. EU membership was correlated with higher law scores in 2003 but not in 2008 or 2011, suggesting that the power of EU membership to influence domestic law came at a time of its growth in membership accession a decade ago. Government ideology was not significant in these models, but the type of electoral system did matter in 2008 and 2011. In 2008, countries with proportional representation systems and mixed systems had higher law scores when compared to a baseline of those with FPTP systems, whereas in 2011 PR again had a positive effect but the mixed system did not.

It is plausible that religion would affect the degree of equality under law above and beyond social values, but the models using religion (in countries categorized by a dominant or plurality national religion—Protestant, Christian, Eastern Orthodox, Islam, or other [Buddhist, Hindu, Shinto, Animist])—showed no demonstrable effect. This lack of effect stems from the complex relationship between organized religion and tolerance. Although most organized religious institutions have negative attitudes toward homosexuality, some are more overtly discriminatory than others. Indeed, even within Protestantism one finds widely divergent degrees of tolerance and support for gay people and legal equality. American evangelicals often lead anti-gay movements, but Quakers and some denominations of Anglicans and Baptists have strongly affirmed gay rights in the United States (Adam Reference Adam2003, 263). In 2008, the Lutheran Church of Sweden announced its full support for gay marriage. Catholics are deeply split, but have collectively become the most progressive Christians in the United States on the issue of gay rights (Considine Reference Considine2011), whereas Spain, Portugal and Argentina all have gay marriage laws despite their strong Catholic orientations. Miriam Smith (Reference Smith2008) outlines how evangelicals were much less mobilized in anti-gay crusades in Canada than their counterparts south of the border. Furthermore, a simple “dominant” religion dummy fits poorly with the many heterogeneous nation-states that do not have a dominant (majority) religion. Religious intensity or religiosity may be a better indicator, but this variable is difficult to operationalize across such a large dataset.

The statistical relationship between out LGBT MPs and gay legal rights appears strong and robust, but are there reasons to believe that selection effects skew the results? Does the presence of open LGBT MPs have any effect on law over and above that of progressive social attitudes in making a country more inclined to support gay rights?Footnote 17 After detailed analysis there is good reason to believe that selection effects are not a serious problem in the models discussed earlier. When the models were run with social attitudes as the dependent variable, the significance of gay MPs as a predictor was inconsistent over time. Thus they did not show whether one causes or precedes the other, but only that they were correlated with each other. The most plausible explanation drawn from all the evidence is that gay MPs and social attitudes form a virtuous cycle. As hypothesized earlier, LGBT MPs are more likely to be found in more tolerant societies, but once they are in office they influence the dialogue and crafting of laws in a way that has positive effects on societal attitudes. The election of gay MPs, the enhancement of gay rights, and the emergence of progressive social attitudes are mutually reinforcing phenomena.

A supporting piece of evidence supporting the theory that LGBT MPs have a positive role to play in transforming attitudes once they assume office is that, when LGBT MPs are elected and subsequently run for reelection, they are overwhelmingly successful, regardless of whether they were initially elected as out candidates or came out (or were outed) while in office. The evidence for this proposition is most clear for those LGBT MPs who were elected as individual candidates in single-member districts. Fifty-seven MPs in my dataset were elected from single-member districts in either FPTP, two-round systems, or from the single-member mandates in mixed electoral systems (1973–2011: Canada, France, Germany, New Zealand, United States, and the United Kingdom). Twenty-nine were out when elected, and 28 came out during their time in office. Of these 28 MPs, 19 were reelected after coming out, of whom 13 increased their majorities. The average size of the majority of winning candidates in elections immediately after coming out was 21 percent, which was almost double the winning margin of first-time MPs. The margin of election victory in first-time races won by out candidates was 12% compared to 14% for candidates who were not openly gay. Only three MPs lost their seats after coming out (and Mario Silva held his Canadian riding once before losing in 2011). Four others retired or resigned before standing for reelection, and in 2012 three others waited to present themselves to the electorate now that they were out. This compares to reelection rates of those MPs who were out when first elected. Fifteen of those 29 MPs were reelected, 12 had not yet had the opportunity to present themselves to the electorate again, one chose to not run again, and one lost his seat (Rob Oliphant who was swept away by the anti-Canadian Liberal party tide of 2011). Incumbency advantage is certainly the underlying cause of the strong reelection rates, but the fact that incumbency still works for LGB MPs who come out while in office suggests that familiarity breeds respect and tolerance rather than contempt.

If openly gay MPs do indeed make a difference to public policy, then what is the mechanism at work? As noted earlier, minority MPs can act as advocates, educators, and physical embodiments of a community shut out of public life. LGBT legislators have an effect on two levels: First, they have a direct impact on colleagues who promote and draft laws,Footnote 18 and second, their visibility affects the views on equal rights and perceptions of gay people held by the electorate writ large. When gay legislators become individuals with names, talents and foibles, aging parents and young children, hobbies, sporting obsessions, and opinions about the latest TV show, it becomes more difficult for their parliamentary colleagues to overtly discriminate against (or fail to protect) them through legislation. Harvey Milk extrapolated on the importance of openly gay candidates running for and then winning office in his “Hope” speech of 1978:

Like every other group, we must be judged by our leaders and by those who are themselves gay, those who are visible. For invisible, we remain in limbo—a myth, a person with no parents, no brothers, no sisters, no friends who are straight, no important positions in employment. A tenth of a nation supposedly composed of stereotypes and would be seducers of children. . . . A gay person in office can set a tone, can command respect not only from the larger community, but from the young people in our own community who need both examples and hope (as quoted in Shilts Reference Shilts1982, 362).

The US based Gay and Lesbian Victory Institute notes that, when cabinet minister, Gabor Szetey, came out in 2007 in Hungary, the event prompted a widespread evaluation of attitudes toward LGBT individuals within the government. This led to the government passing a law allowing registered civil unions for same-sex couples. The German Green Party MP Volker Beck has held various high-level positions in the Bundestag since 1994. His campaign for equal rights led him to be known as the “father of the German registered partnership act” of 2001. Gay marriage passed unanimously in the Icelandic legislature in 2010. On the day the law went into effect, Prime Minister Jóhanna Sigurðardótti legally changed her registered partnership to a marriage. The effect of individual advocacy is perhaps no more profound and surprising than in Nepal. Sunil Babu Pant was elected to the Nepali Constitutional Assembly in 2008 and immediately embarked on a campaign to educate his parliamentary colleagues on what he calls a “third gender,” or lesbian, gay, and transgender people. In that deeply socially conservative country, the Supreme Court ruled that sexual minorities had the same rights as other citizens (Pokharel Reference Pokharel2008). Socially conservative LGBT allies in the United States have cited family and personal relationships as spurs for their support of marriage equality; for example, the Republican politicians Dick Cheney, Jon Huntsman, and Wade Kach (Cooper and Peters, Reference Cooper and Peters2012). The Portuguese Prime Minister, Jose Socrates, made gay marriage part of his reelection platform in 2009, citing the impact of a childhood friend who was gay and how moved he was by the movie Milk. Socrates’, legislation was passed and came into effect in June 2010 (Benjamin Reference Benjamin2012).

These examples are supported by Gregory Lewis's analysis of public opinion in the United States. Lewis posed this question: Does knowing a gay, lesbian, or bisexual person increase an individual's likelihood of supporting gay rights? An analysis of 27 opinion surveys starting in 1983 confirmed that “people who know LGBs are much more likely to support gay rights,” even after controlling for demographic, political, and religious variables, and “the effect holds for every issue, in every year, for every type of relationship, and for every demographic, religious and political subgroup” (Lewis Reference Lewis2011, 217). In June 2012, for the first time, an absolute majority of Americans supported gay marriage—54% for versus 42% against; that support was mirrored by 60% of Americans saying they had a close friend or family member who was gay (compared to 49% in 2010).Footnote 19 Jonathan Gottschall broadens the benefits of straight-gay familiarity to even attachments to fictional characters, noting that

when we are absorbed in fiction, we form judgments about the characters exactly as we do with real people, and extend those judgments to the generalizations we make about groups. When straight viewers watch likeable gay characters on shows like Will and Grace, Modern Family, Glee, and Six Feet Under they come to root for them, to empathize with them — and this seems to shape their attitudes toward homosexuality in the real-world. Studies indicate that watching television with gay friendly themes lessens viewer prejudice, with stronger effects for more prejudiced viewers (Gottschall Reference Gottschall2012).

CONCLUSION

Marginalized communities often seek political representation as a means of protection, advancement, and integration. Whether they achieve representation in elected bodies is a product of the marginalized group's size, geographical concentration, social status, and capacity to make alliances with other interest groups. To date, the study of descriptive representation has overwhelmingly focused on women as a unit of analysis. However, a myriad of other groups, also tethered by traits rather than beliefs, seek and often would benefit from having their own voice within the chambers of government. Women, LGBT people, young people, and the disabled share political interests within their respective “groups,” but they are fragmented geographically, ethnically, and often ideologically. For LGBT people, such fragmentation places yet another hurdle to winning elective office, alongside all of the other hurdles of legal and communal discrimination.

There has been significant progress over the last decade on issues of legal equality. In 2003, only 2 countries recognized gay marriage nationally; by 2011, that number had risen to 11. In terms of their scores on the summary score of equality laws, half of all countries improved, whereas half stayed the same between 2003 and 2011, and there was no backsliding. This article offers strong evidence that the presence, even in small numbers, of out lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender MPs in national legislatures encourages the adoption of gay-friendly legislation. Indeed, the mere existence of politicians who are open about their LGBT sexual orientation has a significant impact on electoral and identity politics. In all model specifications the presence of LGBT MPs is correlated with significant improvements in overall gay rights, and a nation that has elected out MPs is 14 more likely to have marriage equality or civil partnership laws than one without gay MPs.

The direct relationship between out LGBT MPs and public policy appears to be at least as compelling as it is for other marginalized groups, if not more so, because the total number of MPs is small but the statistical relationship between those elected officials and legal progress is strong. LGBT MPs improve policy outcomes above and beyond a society's increasing support for civil rights. The variables are likely to be self-reinforcing: Social and legal progress leads to a better climate for the election of LGBT candidates that then improves equality laws for gay people, but the presence of LGBT MPs is a discrete factor that moves the needle in favor of gay rights. Further, the evidence suggests that LGBT MPs do not require the same type of critical mass as is often cited as a requirement for women to make a difference. In the dataset, a single out LGBT MP is often correlated with improved legal rights, controlling for other determining variables. Narrative evidence shows that openly gay legislators act as mold breakers and trailblazers, giving symbolic hope to younger generations and slowly lessening the shock of difference in the legislative chamber. They are able to change the perspectives and voting behavior of their straight colleagues and put issues of sexual orientation equality on the agenda.

Why do MPs come out while in office? Of the 40 MPs who have come out while in office a number were outed in controversial circumstances; for example, Barney Frank (1987) and Steve Gunderson (1994) in the United States and Michael Brown (1994) in the UK. However, the vast majority came out voluntarily. Based on my interviews with LGB MPs the benefits of coming out are clustered along four lines. First, representatives feel relief at not having to live a lie and hide any longer, which centers them personally. They feel more at peace with themselves and their convictions and thus are happier and more confident. Second, voters appreciate personal honesty even if they may have issues with homosexuality. Third, some parties see sexual orientation diversity as a component part of their desire to be seen as inclusive and modern. This leads to LGB candidates being sought out and promoted by a central party hierarchy (e.g., the UK Conservative Party). Last, as public opinion moves toward supporting equality issues, having an out LGBT candidate is less of an electoral burden that it once was.

The research shows that the opportunities for success vary considerably across nations and across time, but the impact of out MPs appears to be consistent regardless of context. It is sobering to note that when Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir was chosen as prime minister of Iceland in 2009, the focus on her sexual orientation was a curiosity largely promoted by the international media and not the Icelanders themselves, but most openly gay politicians remain a curiosity in their own countries.

What does this research suggest about future strategies for LGBT rights advocates? The public acceptance of gay people is a predictor of progressive law. At first glance this finding is unsurprising. However, it does indicate that politicians and governments have been responding to public opinion, and it suggests that, if the general public becomes more supportive of sexual orientation equality, then governments may respond with broader laws accepting gay marriage, adoption, legal protections, and the like. This article indicates that making even small gains in winning elective office pays large dividends in social and legal progress. This finding suggests that groups that promote, train, and provide resources to openly LBGT candidates (regardless of political affiliation) are on the correct track if they wish to see equalization of the law when it comes to sexual orientation and civil rights. Pouring large amounts of time and money into electing even a single openly gay senator, representative, or state official may strengthen the effort to breaking down stereotypes and ease the passage of nondiscriminatory law.

Globally, the trajectory is clear. More and more openly gay candidates are winning office, and legal equality, across a variety of domains, is gathering momentum. Until 2009, there had never been an openly gay prime minister or president elected to office; in 2012 there were two. Fifteen years ago, there had never been an openly gay cabinet minister, but since then there have been at least 27.

Ultimately, most political leaders are rational actors who wish to maximize their power and influence. If voters (both straight and gay) warm to issues of sexual orientation equality, then it will become a strategic vote-winning strategy for parties to champion such issues and run high-profile gay candidates. Such has been the trend of women's representation in Scandinavia, where female candidates often experience electoral success and political parties seek them out.

Future research should track more closely the way in which LGBT representation fits into critical mass theory. We also need to better understand the driving characteristics of politicians who are openly gay. The second phase of this project will move beyond the quantitative data to survey and interview LGBT MPs around the world, gauging the interaction between their sexual orientation, policy advocacy, and role as representatives. Just as in the case of women MPs, we would expect most openly gay MPs to act as role models for other gay politicians. Wolbrecht and Campbell find evidence that the presence of high-profile women politicians inspires adolescent girls to become engaged in politics (Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2006; Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007). If the dynamics of gender representation are mirrored, we would predict that the first small wave of open LGBT MPs will be followed by a larger wave of gay elected politicians who are faced with reduced (if not eliminated) hurdles to office. Nevertheless, just being gay does not necessarily guarantee that the politician will view LGBT rights as a central, or even peripheral, part of his or her mission as a representative. Some openly gay MPs argue that their sexual orientation is a private matter irrelevant to their political views. The robust correlation between the presence of out MPs and more progressive public policy on sexual orientation issues suggests that there is a mechanism by which their presence alters the values, opinions, and voting behavior of their straight colleagues. Further study of the interaction between LGBT MPs and their colleagues is needed to examine in detail the mechanism(s) at work, but there is reason to believe that merely by their presence a legislator who happens to be LGBT changes the discourse around gay rights.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.