American federalism affords the individual states the power to establish qualifications for voting. Throughout most of American history this has included setting the minimum voting age. Although scholars have examined the evolution of several state electoral laws, most accounts of changes to the voting age have focused exclusively on the adoption of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment. Even those studies centered on youth enfranchisement have tended to focus predominantly on the nationwide change. There was, however, a compelling moment that is often overlooked. In 1943, Georgia’s state constitution was amended to lower the voting-age qualification to eighteen years of age. In doing so, it became the first—and for twelve years, the only—state in the Union to establish a voting-age requirement below twenty-one. This instance of electoral progressivism in the mid-twentieth century Deep South presents an important historical puzzle.

Although the existing literature on voting rights and youth enfranchisement includes a few discussions of Georgia’s reform, scholars have paid little attention to how the voting-age requirement was successfully lowered in Georgia when similar reforms were unsuccessful in other states, and none have systematically explored the impetus behind the change. For example, in a book entirely dedicated to documenting the history of lowering the voting age in the United States, Wendell Cultice simply notes that “it was typically American tradition that out of the flurry of state proposals to enfranchise men and women under the age of twenty-one, conservative Georgia would permit the ship of suffrage to sail in political waters eighteen years in depth.”Footnote 1 Yet, this arguably shallow and curious treatment of the issue seems almost generous compared to the more common mentions of Georgia’s reform as either a small step in the eventual passage of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment, as one of the many accomplishments of Governor Ellis Arnall, or as a modest footnote explaining how the denominator term is calculated in studies on voter turnout.Footnote 2

Unlike previous work, this study highlights the events in Georgia that led to the adoption of such a progressive reform. It is centered on understanding the motivation for the voting-age reform in early 1940s Georgia, and determining whether there was something inherently unique driving the reform’s eventual success in the state. Given its long tradition of restricting voting rights, it is especially curious that Georgia was the only state to lower its voting age at the time. Indeed, when the franchise was extended to youths in Georgia, individuals had to satisfy a property requirement, a year-long state residency requirement, pay a poll tax, and pass a literacy test in order to qualify to vote.Footnote 3 In addition to the limiting, and often explicitly racist, disposition toward enfranchisement in the state, there were several peculiarities in the reform process. For example, unlike all other expansions of suffrage in American history, there is no evidence that the Georgian youth, or any other group, lobbied for the reform in the state. Further, the discourse surrounding the reform reveals no reason why lowering the voting age was unique to Georgia qua Georgia. Thus, this study explores the important question: Why Georgia?

The narratives presented in this work suggest that the impetus behind the successful passage of the voting-age amendment in Georgia was the dedication of its young governor—Ellis Gibbs Arnall. Of course, policymaking, especially of this magnitude, rarely happens in a vacuum. As such, I argue that a combination of Arnall’s entrepreneurial proclivities and political ambition, his ability to harness intraparty factionalism and a cry for New Deal–inspired liberalism, and strategic timing, led to the amendment’s eventual success. Ultimately, this study demonstrates that Arnall’s dedication to the movement coupled with the volatility of Georgian politics at the time allowed Georgia to emerge as a curious and unappreciated pioneer on the road to early youth enfranchisement in the United States.

In the following sections, I will, first, offer a brief history of youth enfranchisement in the United States highlighting the role that the federal government and the individual states played in the eventual ratification of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment. Then, I explore a number of possible explanations for Georgia’s early-mover status. This leads to an in-depth discussion of the instrumental role that Georgia’s governor, Ellis Arnall, played in prioritizing the voting-age issue, and in the amendment’s eventual success in 1943. This detailed legislative history highlights the anti-“old guard” sentiment that prevailed in Georgia at the time Arnall was elected, and ultimately helped him assemble a political coalition in support of the reform. Next, I offer a number of reasons why Arnall championed the legislation; arguing that his eventual success hinged on a moment of growing intraparty factionalism in the state, and was based on his entrepreneurial tendencies and strategic timing. As a comparison, I also show that the dynamics that were central to Georgia’s success in 1943 were specific to Georgia and were not present twelve years later when Kentucky’s voting age was lowered. Finally, the article concludes with a discussion of the implications that Georgia’s amendment had for the progression of the youth enfranchisement movement in the United States, and explores its place within a more broadly shifting wartime culture.

The History of Youth Enfranchisement in the United States

From the nation’s founding until 1971, almost all jurisdictions in the United States required individuals to be at least twenty-one years of age in order to vote. This provision was even enshrined in Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Indeed, twenty-one has long been considered the age of political maturity required for participation in most democratic systems. Interestingly, the reason for twenty-one, as opposed to any other age had little to do with civic experience. It was an anachronism of the feudal era, representing “the age at which most males were physically capable of carrying armor.”Footnote 4 This norm—rooted in colonial and British precedents—has been a surprisingly constant feature of American voting laws.

Despite the consistency of actual voting-age requirements, expanding youth enfranchisement has been routinely discussed throughout American history. Although proposals to lower the voting age were occasionally offered as far back as the nineteenth century, the issue has arisen most frequently during times of war. Indeed, discussions about voting-age requirements and compulsory military service have been wholly intertwined throughout much of the debate. This connection was solidified in earnest during World War II when Congress and President Roosevelt aimed to meet the growing need for military personnel by lowering the draft age from twenty to eighteen years old. This decision generated a flurry of proposals that the voting age be similarly lowered, and motivated the first of many “old enough to fight, old enough to vote” arguments.Footnote 5

Debates over expanding the franchise took place in the US capitol and under many state domes throughout World War II. For example, multiple proposals to lower the voting age were introduced in both houses of Congress during the war. Responding to escalating war efforts, Senator Harley Kilgore (D-WV) introduced the first such measure in 1941, and Senator Arthur Vandenberg (R-MI) and Representatives Jennings Randolph (D-WV) and Victor Wickersham (D-OK) proposed similar measures in 1942. In making his case for the national legislation, Representative Randolph (D-WV) drew on the military argument noting that “one-quarter of the army, half the marine corps, and more than a third of the navy consisted of men under age twenty-one.”Footnote 6 In 1943, Eleanor Roosevelt also publically argued that eighteen- and nineteen-year-olds be given the right to vote.Footnote 7 Yet, despite rigorous discussion and a series of informational congressional hearings throughout the war, all of the federal proposals were unsuccessful.

There was also considerable discussion about lowering the voting age in the states during World War II. Thirty-one states introduced more than forty resolutions to lower the voting-age requirement between 1942 and 1944. For example, in 1943, the Alabama State Senate proposed a constitutional amendment to lower the voting age to eighteen, and a similar resolution was introduced in North Carolina. With the support of the president of the state university, a former governor, and vice chairman of the Democratic State Committee, New York legislators also introduced proposals to lower the voting age to eighteen in 1943, and again in 1944. In New Jersey, Governor Charles Edison also repeatedly voiced his support to lower the state’s voting age to eighteen.Footnote 8 Although voting-age reforms were considered in several states during this period, only one state was successful—Georgia.

In the decades following World War II, the issue continued to be widely debated. Proposals were continually discussed—and most rejected—in several states. As shown in Table 1, during the years between Georgia’s successful adoption in 1943 and the ratification of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment in 1971, forty-five states considered, but ultimately rejected, proposals to lower the voting age. The issue was particularly salient during the Korean War, as “the realization that many thousands of young men between the ages of 18 and 21 were serving in combat situations spurred the introduction of proposals to lower the voting age.”Footnote 9 Despite efforts made by various youth organizations, the National Education Association, and veterans groups during the Korean War, voting age requirements were only successfully lowered in three other states. In 1955, twelve years after the amendment passed in Georgia, the voting age in Kentucky was lowered from twenty-one to eighteen.Footnote 10 Also, upon gaining statehood in 1959, both Alaska and Hawaii established voting age requirements below twenty-one. Individuals were allowed to vote in Alaska at nineteen and in Hawaii at twenty.Footnote 11

Table 1. Failed attempts to lower the voting age in the states, 1943–1970.

Source: Various newspaper articles and secondary sources, including Wendell W. Cultice, Youth’s Battle for the Ballot: A History of Voting Age in America. New York, 1992; and David E. Kyvig,

Explicit and Authentic Acts: Amendment of the Constitution, 1776–1995. Lawrence, KS, 1996.

Note: In this table, “failed attempts” reflects any serious legislative consideration to lower the voting age in the state. This includes measures that were introduced, as well as measures that were voted on but did not pass.

Expanding the franchise also continued to be discussed by the federal government in the years following World War II. Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon each proposed lowering the voting age to eighteen in response to ongoing military action during their respective terms—Eisenhower in 1954, Kennedy in 1968, Johnson in 1968, and Nixon in 1970. Voting-age amendments were also introduced in the 83rd through 91st Congresses, but no significant action was taken on any of the proposals. It was only in 1970, after holding extensive congressional hearings, that Congress moved to successfully lower the voting age in both federal and state elections. Ultimately, in the summer of 1971 Congress passed, and the states ratified, the Twenty-Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution. In the quickest ratification process in American history—just one hundred days—the voting age requirement was lowered nationally to eighteen. This was thirty years after the issue had first been seriously considered.

What Did the Public Think?

The history of youth enfranchisement in the United States reveals that many national and state actors attempted to expand the vote during the decades between World War II and 1971, but almost all of their attempts proved unsuccessful. Given the salience and persistence of the issue over the years—and during multiple wars—this is quite striking. Yet, one must consider the public’s opinion on the matter throughout the duration of the debate. Without widespread public support favoring the expansion of the vote, public officials would have been hard-pressed to achieve success, especially since successful state action would typically have required a special election and the support of the public for ratification. Indeed, over the first few decades that the issue was debated, there was not widespread public support for the movement.

As shown in Table 2, national surveys regarding public opinion on lowering the voting age reveal no sustainable majority support for youth enfranchisement until the mid-1950s.Footnote 12 In fact, the only time that there was a majority (52 percent) in favor of the reform during the early years of the debate was in August of 1943 at the height of World War II. Interestingly, even the youth themselves did not overwhelmingly support the reform during the early years. According to Jones, among those 21–29 only 17 percent supported lowering the voting age in May 1939, and only 41 percent of the youth surveyed supported it in January 1943.Footnote 13 Over the decades that the issue was debated, opponents of the reform maintained that the voting age was a state rather than federal matter, and given more pressing public concerns it was not regarded by most individuals as a high-priority item. During the later years of the debate, accounts suggest that support for the reform grew as various youth and veteran organizations mounted mobilization campaigns that pressed hard for state and federal action on the issue, and as controversies over military involvement abroad persisted.Footnote 14

Table 2. Public opinion on voting-age reform in the United States.

Source: The data presented in this table were taken from several surveys conducted by George Gallop, The Gallop Poll, 1935–1971 (New York, 1972), and reported in Doris W. Jones, “Lowering the Minimum Voting Age to 18 Years: Pro and Con Arguments.” Report prepared for Library of Congress, Congressional Reference Service, June 8, 1956; and Thomas H. Neale, “The Eighteen-Year-Old Vote: The Twenty-Sixth Amendment and Subsequent Voting Rates of Newly Enfranchised Age Groups.” Report prepared for Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service. May 20, 1983.

Note: The wording of the questions varied slightly, but each question measured whether the respondent favored or opposed lowering the voting age from 21 to 18.

Why Georgia?

After reviewing the history of youth enfranchisement in the United States, Georgia emerges as distinct in its ability to adopt a voting age reform during the first serious wartime discussion of the issue—nearly three decades before federal action required it—and despite underwhelming public support of the issue. Georgia’s success is also especially striking given its long history of implementing exclusionary voting laws. Indeed, McDonald argued that “no state was more systematic and thorough in its efforts to deny or limit voting and office holding by African-Americans after the Civil War. It adopted virtually every one of the traditional ‘expedients’ to obstruct the exercise of the franchise by blacks.”Footnote 15 Of course, Georgia’s restrictive voting qualifications—such as the poll tax and literacy requirements—were also coupled with the Democratic Party’s white primary system that barred black individuals from participation in primary elections. The implementation of the white primary was especially consequential within the single-party Democratic South and rendered votes in the general election essentially meaningless. In short, at the time, victory in the Democratic primary was tantamount to election in Georgia. As discussed by V. O. Key, this had important effects for electoral competition and participation rates in the southern states—especially Georgia.Footnote 16

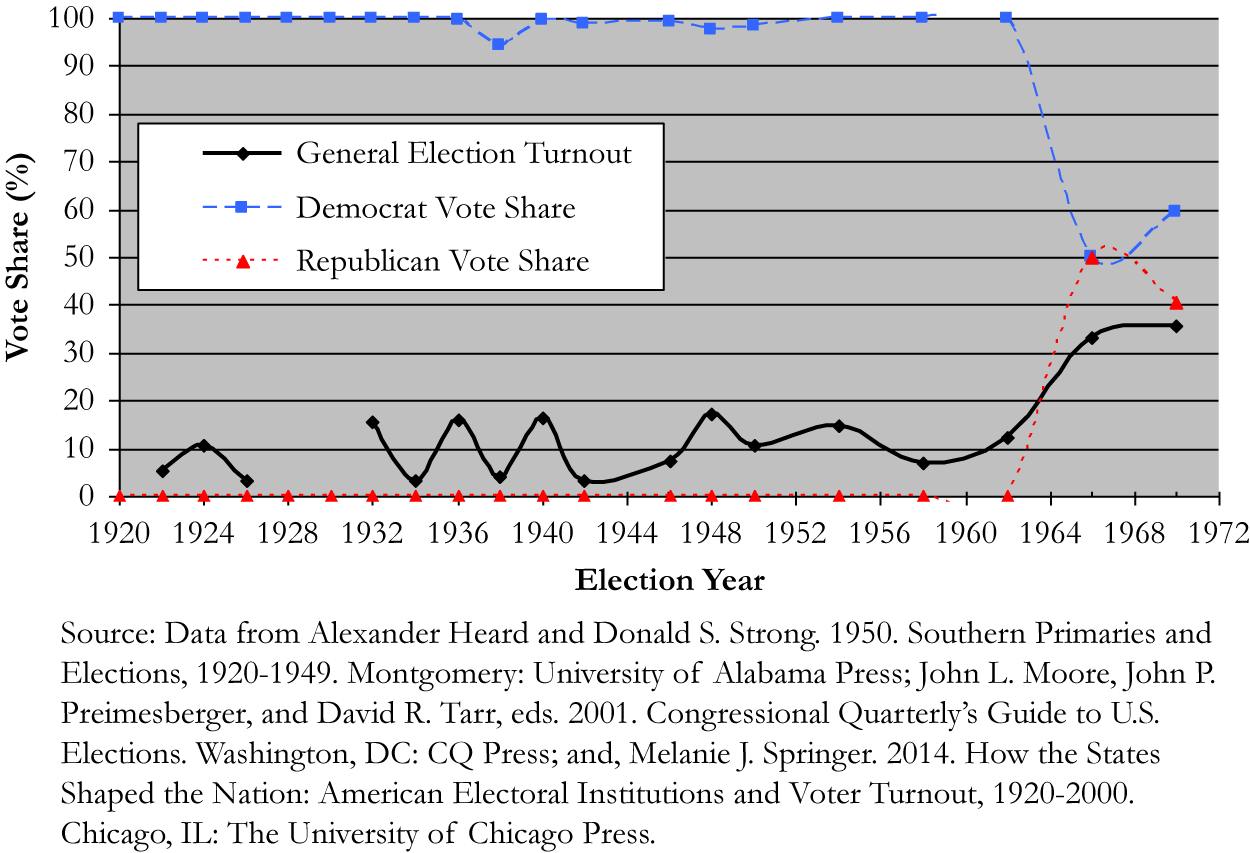

As shown in Figure 1, voter turnout rates were noticeably higher during gubernatorial primary elections than during gubernatorial general elections in Georgia from 1920 to 1964.Footnote 17 This pattern continued even after the white primary was eradicated following the Smith v. Allwright Supreme Court decision in 1944.Footnote 18 As shown in Figure 2, the Democratic Party’s power—and the corresponding lack of electoral competition—at the general election is also apparent in the partisan distribution of votes during the pre–Civil Rights period. The Democratic Party dominated gubernatorial elections in Georgia prior to 1964. These trends also existed during elections for national office. Figures 3 and 4 show comparable figures in Georgia during US Senate elections from 1920 to 1972.

Fig. 1. Voter turnout in Georgia, gubernatorial elections 1920–1972.

Fig. 2. Partisan vote shares in Georgia, gubernatorial elections 1920–1972.

Fig. 3. Voter turnout in Georgia, U.S. Senate elections 1920–1972.

Fig. 4. Partisan vote shares in Georgia, U.S. Senate elections 1920–1972.

Together the prevalence of disenfranchising electoral laws, the lack of interparty electoral competition, and skewed voting patterns reflect the history of limitation and exclusion that was prevalent in Georgia, and throughout the Deep South, in the years following Reconstruction. Yet, despite the implementation of countless barriers to participation, expansiveness and foresight were demonstrated in the decision to lower the state’s voting age requirement in 1943. Why? The following section will present several possible explanations for the uncharacteristic reform pursued in Georgia, discuss Georgian politics in 1943, and highlight the pivotal role its progressive governor played in the amendment process.

Explaining Georgia’s Success

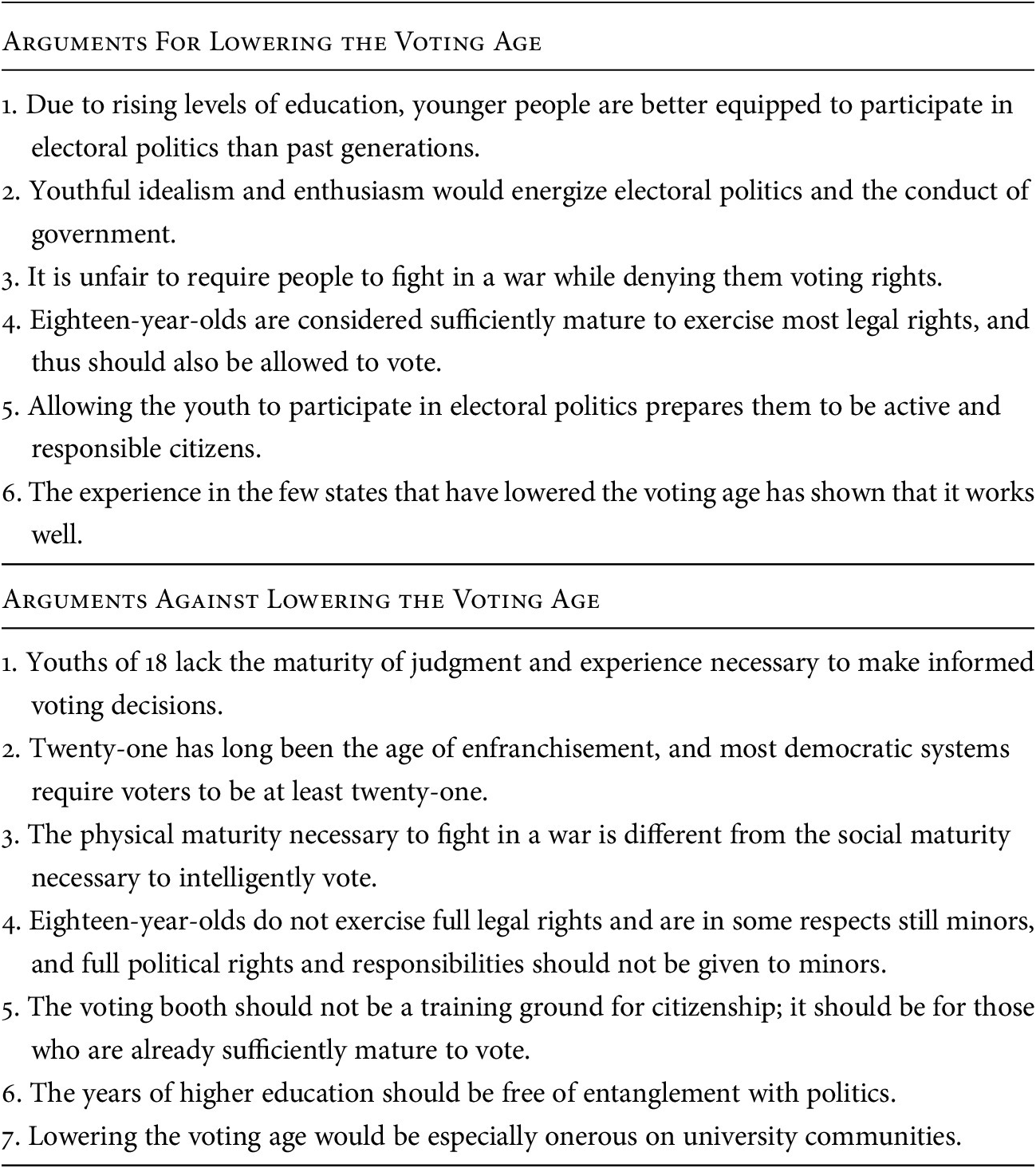

As summarized in Table 3, numerous arguments both in favor and opposed to extending the franchise to those between the ages of eighteen and twenty-one were raised over the thirty years the issue was considered. In this section, two of the more plausible explanations for Georgia’s first-mover status in youth enfranchisement are discussed, and ultimately refuted. First, youth enfranchisement has consistently been associated with military service. This might indicate that Georgia’s action was due to its disproportionate participation in World War II. Second, since the arguments for and against lowering the voting age have been generally consistent throughout the history of the debate, there might have been some unique political argument for youth enfranchisement in Georgia. That is to say that Georgians may have been persuaded by a general argument for youth enfranchisement that was particularly suited to Georgia, and, therefore, might explain the motivation to pursue the reform. Although both of these hypotheses are possible, as demonstrated below, neither provides a satisfying explanation.

Table 3. Common arguments “for” and “against” lowering the voting age.

The Military Explanation

As noted before, discussions of youth enfranchisement often centered on the disparity between the age at which someone could vote and the age at which someone could be drafted into military service. Indeed, the “old enough to fight, old enough to vote” argument has been at the center of most debates over youth voting, and most academic accounts of the issues surrounding youth enfranchisement. Georgia was no exception. Much of the rhetoric regarding the state’s voting amendment focused on the eighteen- to twenty-year-old Georgian citizens who were serving in World War II but were ineligible to vote.Footnote 19 As such, popular sentiment regarding the fairness (or unfairness) of drafting eighteen- to twenty-year-olds while not allowing them to participate in politics could explain why the voting age was lowered in Georgia. However, if this was the motivating reason, it is not clear why Georgia alone would have lowered its voting age in 1943. The entire nation was involved in World War II, with eighteen- to twenty-year-old citizens contributing to the war effort but unable to vote nationwide.

In order for the military argument to explain why Georgia alone lowered its voting age, there must have been some reason why it was particularly persuasive in Georgia. This could have been possible if Georgia had contributed disproportionately to the war effort. If, for example, a relatively larger number of Georgian citizens were serving in the armed forces than in other states, then the military argument might have been particularly salient and important to Georgians. Also, if a relatively larger number of Georgian citizens were lost in service compared to other states, then one might expect that Georgians would be more likely to enfranchise the youth as a sort of repayment for their sacrifice.

To test these hypotheses, data were collected on state population rates, state army enlistment totals, and state army losses during World War II. Using these data, measures of Army Enlistment and Army Casualties were constructed for each of the forty-eight states. Table 4 presents these state-by-state rankings.

Table 4. State-by-state war effort during World War II.

Source: Army enlistment and causality data were acquired from the National Archives, World War II Honor List of Dead and Missing Army Personnel. State population data was taken from the US Census Bureau’s Statistical Abstracts of the United States. Linear interpolation was used to generate between-census population estimates.

Note: Army Enlistment was calculated as a percentage of each state’s total army enlistment out of its total population. Army Casualties was calculated as a percentage of each state’s total army losses during World War II out its total Army enlistment.

These measures do not overwhelmingly support the argument that Georgia contributed disproportionately to the war effort, or suffered comparatively high losses during World War II. As shown in Table 4, 6.5 percent of Georgia’s population was enlisted in the Army, which is slightly above the mean (5.8 percent), but not tremendously so. Nineteen other states contributed a greater percentage of their populations to the war effort but did not lower their voting age requirement during the war. As for losses, Georgia’s casualty statistics (2.8 percent) were nearly the lowest in the country, and far below the mean (4.5 percent).Footnote 20 Further, there does not seem to be a contrary correlation—with states that scored low on these measures having a greater propensity to ignore or reject youth enfranchisement. For example, Alabama and North Carolina, where reform proposals were considered and rejected during the war, had nearly equal enlistment rates as Georgia; while New York and New Jersey, which also considered but rejected the reform, had even more servicemen participating in the war effort than Georgia. As for Army casualties, only Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi had a lower percentage of servicemen lost than Georgia, and Florida and Alabama both pursued reform during the war. Further, many of the states that considered expanding the franchise during this time had casualty rates substantially below the mean. Thus, it appears that disproportionate military enlistment or losses during World War II do not explain a state’s ultimate action or success regarding youth enfranchisement.

“Uniquely Georgian Arguments” Explanation

Throughout the debate over lowering the voting age, the arguments for and against the youth vote were impressively consistent. Focusing on the general fairness and propriety of the youth vote, these arguments would apply to any jurisdiction considering lowering the voting age. Yet, one possible explanation for why Georgia was singularly successful in lowering its voting age is the existence a compelling Georgian spin on any of the general arguments; namely, there might have been a uniquely Georgian argument or rationale to support lowering the voting age. To investigate this possibility, newspaper coverage of the debates over Georgia’s voting amendment were extensively surveyed. What follows is a summary of the general arguments that existed for and against the voting amendment in Georgia prior to adoption.

1 “Old Enough to Fight, Old Enough to Vote”

As previously noted, discussions over the voting age and draft age in the United States have long been intertwined. Indeed, the debate surrounding the adoption of Georgia’s voting-age amendment began with such an argument. As proclaimed at his gubernatorial inauguration in 1942, Governor Arnall viewed this argument as being irrefutable. He described it as “analogous to the revolutionary battle cry of ‘no taxation without representation,’”Footnote 21 and many Georgians agreed with him.Footnote 22 For example, in a letter to the editor of the Savannah Morning News, E. C. Sanders, a supporter of the amendment, argued that the draft and voting ages must be the same, noting “to do otherwise is inhuman; it would be to take advantage of the innocent, the helpless. It would be the antithesis of democracy.”Footnote 23

Like challengers of the amendment elsewhere, opponents of youth enfranchisement in Georgia argued the popular counterpoint; namely, that the skills necessary to fight were not the same as those necessary to vote. For example, Georgia State Representative Mankin argued that “youthful impetuousness, adventurousness, and recklessness go to make a good fighting man, all of which are excellent but which do not necessarily mean he has acquired a knowledge of government, thoughtfulness in civic affairs, and so forth.”Footnote 24 Similarly, it was noted in the Augusta Chronicle that “the same impetuosity and spirit of reckless abandon which makes 18 and 19-year-old youths such admirable fighters might be just the qualities which would be least desirable when the franchise is bestowed upon these Georgia lads.”Footnote 25

2 Are Youth Prepared to Vote?

A frequent point of contention in the debate over lowering the voting age was whether those under twenty-one were ready to vote. When opponents of youth enfranchisement in the Georgia State Senate argued that “the youthful mind was not capable of mature judgment at the polls,” one supportive legislator reportedly countered that “children 15 years old today know more about the facts of life than [the opponents] knew when [they] were 25.”Footnote 26 Similarly reasoned in a letter to the editor of the Savannah Morning News, a supporter of the amendment, though regarding it as “without question that many eighteen to twenty year olds are not qualified to vote,” asserted that “the same goes for many twenty-one to eighty year olds,” noting the “large number of voters he had seen on election day who knew nothing of the candidates or issues and cared less!”Footnote 27

Opponents of youth enfranchisement, however, maligned the prospect of, as they often put it, “children voting.”Footnote 28 They also expressed concern over outside influences on young voters. For example, one Georgia senator argued that colleges would “have control over [children] and tell them to disregard their parents.” Another added that “every high school and college will be nothing in God’s world but a political club.”Footnote 29

3 Youthful Idealism and Maturity

Supporters of youth enfranchisement in Georgia often cited the benefits youthful idealism and energy would bring to the electoral system. They viewed youth as incorruptible and free from the control of political bosses. Along these lines, the Atlanta Constitution praised the “salutary increase in idealism and … informed outlook upon public affairs that youthful voters would bring” predicting that “their purity would help them spot corruption in their political leaders.”Footnote 30 One supporter of the reform even argued that “democracy is dying of dry rot and needs the insurgence of youth.”Footnote 31 Others argued “that youth would bring open mindedness and a lack of cynicism to politics and exert a wholesome influence.”Footnote 32 Yet some contended that enfranchisement was a threat to youthful idealism. A letter to the editor of the Augusta Chronicle argued that “it wouldn’t be right nor wise to burden the young people with the duties … that could only molest the carefree, happy-go-lucky life, which has characterized youth since creation.”Footnote 33

Still others, including some of the youth themselves, commented about the consequences of immaturity over the promise of youthful idealism. For example, an editorial in the University of Georgia’s Red and Black student-run newspaper argued that twenty-one was a much better estimate for political maturity because at that point the voter has “finished his college education, and facing the reality of the world, is no longer sheltered by free money and the lack of responsibility.”Footnote 34 The editors of the Red and Black stated that they would “gladly waive the great responsibility [of voting] to those who we feel know more about politics, the good and evil of them, and the possible reforms available, rather than to subject ourselves prematurely to them.”Footnote 35 Echoing these sentiments, the editorial concluded: “Fighting is a man’s job; let a man do it. Voting is a veteran’s job; let a veteran do it.”Footnote 36 Another young Georgian opposed the voting amendment noting that most of those affected by the amendment “are frankly not interested, seriously, in voting matters.”Footnote 37

Many Georgians also recognized that the stipulated age to exercise most legal rights, such as contracting, was twenty-one, and saw no reason why those “who are not legally responsible for their actions should vote on laws and public debts which do not apply to them.”Footnote 38 There were further concerns that allowing eighteen-year-olds the vote would also require allowing them to sit on juries and hold public office.Footnote 39 Similarly, the Savannah Morning News cautioned that youth enfranchisement would mean that “all the laws pertaining to the age of majority should be changed to apply to those of 18 instead of 21, such as the laws relating to parental control, property ownership and the right to sue and be sued.”Footnote 40

4 Communism

Beyond the influence of youth’s idealism noted in the previous arguments, concern over the potential effects of communism was also voiced by numerous opponents of the voting-age amendment. Specifically, Georgian State Representative J. Robert Elliott argued that “the Communist party and Mrs. Roosevelt are 100 percent behind this proposal.”Footnote 41 Another opponent asserted that “only Communists or those with Communistic inclinations were for this bill.”Footnote 42 Senator Jack Williams declared that “he thought all youth Communistic.”Footnote 43 Others thought youth enfranchisement “would make the state a hotbed for every subversive influence under the heavens.”Footnote 44 Still another opponent noted that “Mussolini and Hitler established their dictatorships through youth movements,”Footnote 45 and others argued that because “Soviet Russia began the experiment of youth enfranchisement, it is wise to wait and see the results there.”Footnote 46 Finally, in perhaps the starkest example of accusations relating the voting-age amendment to Communism, the Savannah Morning News published the following query:

In Soviet Russia the right to vote is extended to all men and women over 18 years of age. The Socialist Federated Soviet Republic holds property and the means of production and distribution under communistic ownership. Socialism, communism, bolshevism and anti-capitalism have all flourished there.… Only in Russia has the voting age been lowered to 18. Nationalization of industries, with socialization of all property and abolishment of private ownership has also been adopted by the Soviet Republic. How do we know but that the adoption of the teen-age voting amendment in Georgia would be but a stepping stone to other revolutionary and fanatical proposals, imported from Russia, Germany or Italy?Footnote 47

5 Racial and “Old Guard vs. New Guard” Arguments

Opponents of youth enfranchisement in Georgia also voiced concerns that the bill would enfranchise young black individuals as well as whites. As noted by McDonald, “No matter how strong the purely ‘good government’ arguments were for lowering the voting age, any proposed change in the state’s election laws was inevitably scrutinized under, and distorted by, the microscope of race.”Footnote 48 Indeed, Georgian Senator William W. Stark argued against youth enfranchisement in the state because he thought it would “mean that every Negro boy and every Negro girl should have the right to go to the polls and vote.”Footnote 49 Supporters of the bill responded that youth enfranchisement would in no way change the white primary system, which at the time restricted participation in Democratic primary elections to white voters.

Finally, and relatedly, a number of Georgians suspected that opposition to the voting amendment stemmed from the so-called old guard of politicians (and their supporters), who did not appreciate change. One letter to the editor argued that “the real outcry against the young people voting probably comes from the old party leaders who have been caught napping by the new youth vote, and they probably think they won’t be able to handle these young votes along the lines they have controlled the old liners.”Footnote 50 In his column in the Atlanta Constitution, Ralph McGill asserted that opposition to youth enfranchisement came from “old guard” politicians who “fear the natural idealism and the impulsive honesty of young people that they cannot control.”Footnote 51

The arguments presented in these narratives reveal that although most of the widespread arguments in favor and against lowering the voting age (as summarized in Table 3) were raised during the debate over adoption in Georgia, there does not appear to be a uniquely Georgian spin on any of them. Further, no specific Georgian argument was evident in the coverage of the state or national discussion. If the arguments over adoption in Georgia were the same as they were anywhere else, then there is no logically necessary reason that Georgia would be the only state to lower its voting age in 1943. However, in surveying all of these arguments, Governor Arnall’s continued support for youth enfranchisement was evident. The next section explores Arnall’s commitment to the reform as a possible explanation for Georgia’s pursuit, and eventual adoption, of the voting-age amendment.

Governor Ellis Gibbs Arnall

In 1942, Ellis Gibbs Arnall was elected as the seventy-first governor of Georgia. Winning the state’s first four-year gubernatorial term, he held the position from 1943 to 1947. Arnall was just thirty-five years old when he took office, making him the nation’s youngest governor. Although his tenure as governor was short, he left a distinct imprint on Georgian history. Indeed, his election was described as marking “the brief ascendancy of New Deal liberalism in Georgia,” and he has been touted as “Georgia’s most progressive modern governor.”Footnote 52 Cook notes that at the time Arnall was elected “the state was rural, poor, provincial, undeveloped, and often ridiculed by Northern liberals and the national media, but when he left office four years later, Georgia rivaled North Carolina as the South’s most progressive state.”Footnote 53 Similarly, historians have claimed that Arnall’s inauguration “marked the beginning of one of Georgia’s most important eras of change in the twentieth century,”Footnote 54 and his victory was “evidence of a democratic awakening in the South.”Footnote 55 In his single term as governor, Arnall had an undeniable impact on Georgian politics.

Arnall was serving as the state’s attorney general when he decided to run for governor. He had been elected attorney general without opposition in 1940, the same year that Eugene Talmadge was elected governor for the third time. Talmadge, who V. O Key described as “Georgia’s demagogue,”Footnote 56 was a political powerhouse with deep political roots in rural Georgia. As an aspiring politician, Arnall became Talmadge’s political ally. In 1931, Arnall supported Governor Talmadge while serving in the Georgia General Assembly, and in 1935 Talmadge named Arnall special assistant attorney general. Their relationship changed, however, when Talmadge “attempted to purge the University System of Georgia of liberal professors; those he deemed ‘furriners’ too favorable to blacks.”Footnote 57 In his quest to “rid the university system of anyone who supported ‘communism or racial equality,’”Footnote 58 he fired several professors and key administrators. The controversy surrounding these events garnered national attention, and ultimately the state’s university system lost its accreditation due to Talmadge’s interference. Acting as attorney general, Arnall, “questioned the legal basis for [Talmadge’s] higher education purge,”Footnote 59 “refused to condone Talmadge’s actions,”Footnote 60 and “overnight became the champion of academic freedom in Georgia.”Footnote 61

On November 1, 1941, Arnall announced his candidacy for governor. At the time, the public was outraged by Talmadge’s attack on the state’s university system and the damage Talmadge and his administration had done to the state’s government and reputation. Capitalizing on Talmadge’s misstep, Arnall made the state’s university system crisis the centerpiece of his gubernatorial campaign and promised to take politics out of education. Many educators, college students, and their parents were mobilized by Arnall’s focus on the state’s university system crisis, and several of them volunteered to work on his campaign. In response, Talmadge attempted to sidestep the education controversy and tried to convince voters that “southern traditions and customs, rather than education, were the main issue in the race.”Footnote 62 Arnall, who had long been on the right side of public opinion on the education issue, and could point to his attempts as attorney general to stand up to Talmadge, proved to be a formidable challenger.

Aided by Speaker of the House Roy Harris and former governor Eurith (Ed) Rivers—both prominent members of a growing anti-Talmadge faction in Georgia—Arnall launched an effective “good government” gubernatorial platform. Yet, by all accounts, the distinctively progressive agenda that Arnall pursued once he became governor was not apparent during his quest to win office. Indeed, throughout the campaign, he was described as a “typical traditional, folksy, small-town lawyer-politician, undistinguished from dozens of others operating in the extremely conservative political environment of Georgia.”Footnote 63 In line with other southern liberals during this time, Arnall defended segregation and white supremacy almost as vociferously as Talmadge. In fact, apart from Arnall’s pledge to remove politics from the university system, there was little progressivism to be found in his gubernatorial campaign. Notably, Arnall did not mention a desire to lower the state’s voting age—or initiate any other liberal reforms—at any time during the election.

The governor’s race in 1942—held amid a distinct anti-Talmadge political climate—was one of the most publicized elections in Georgia’s history. It reflected the growing bifactionalization of the state’s political allegiances (e.g., pro-Talmadge vs. anti-Talmadge) and offered the possibility to break from a traditional approach to state governance. Of course, institutional context greatly affects electoral outcomes. In this case it was Georgia’s county unit system—described by Key as “unquestionably … the most important institution affecting Georgia politics.”Footnote 64 Before being declared unconstitutional in 1963, state law stipulated that the candidate receiving the highest number of votes in a county would be considered to have carried that county. The system assigned each county a certain number of unit votes—the 38 most populous counties had six or four votes apiece, and each of the remaining 121 counties had two votes. A county’s unit votes went to the candidate who got the most popular votes in the county, and the candidate with the largest number of county unit votes won the election.Footnote 65

Similar to critiques about the Electoral College disproportionally favoring the influence of small states during presidential elections, under the county unit system, the ballot of a voter in a rural county counted more than the ballot of a voter in a large city. This meant that by winning pluralities—not necessarily majorities—in several small rural counties, a gubernatorial candidate with connections in the rural counties could win the election without winning the statewide popular vote. Of this rule, it is noted that “Georgia never had one statewide election for governor but instead had 159 such elections, one for each county in the state.”Footnote 66 Further, “given Georgia’s abundance of small counties, this system always allowed the less populous rural counties to dominate politics in the state,”Footnote 67 and created the possibility that a gubernatorial candidate could win the election with exclusively rural support.

The power of the county unit rule in Georgia’s primaries was further exacerbated by the Democratic Party’s dominance over southern politics during this period. The lack of interparty competition made the primary election the real electoral contest, since the Democratic nominee always went on to win the general election. The primary election in 1942 was no exception. On primary election day, Ellis Arnall received 174,757 popular votes and 261 of the state’s 410 county unit votes to Talmadge’s 128,394 popular votes and 149 county unit votes. In doing so, Arnall successfully defeated longtime incumbent Eugene Talmadge—and was elected governor. Observers of this moment in Georgian history would note that the confluence of growing intraparty bifactionalism, the university system crisis, and the particulars of the state’s county unit rule conspired in Arnall’s favor.

Although Arnall was elected with a simple mandate to “save the university system,” he had much broader goals, and he began pursuing them as soon as he took office. As a new governor, he quickly differed from his predecessors. Patton notes that “the man who assumed the governorship in 1943 had a vision for his state and his region that was diametrically opposed to that of Talmadge.”Footnote 68 He appeared liberal and progressive to the “old-guard,” as he developed a relatively coherent and comprehensive plan for “promoting economic growth and overcoming the South’s colonial status.”Footnote 69 He was also deeply committed to the principles of democracy. His motto as governor—“There is nothing wrong with government that democracy won’t cure”Footnote 70—reflected this. As a newly elected governor, he pursued several policies to incorporate more Georgians into the political process. Although education reform was Arnall’s first priority, under his leadership Georgia became the first state to pass a soldier voting law, the first state to lower the voting age to eighteen, and the fourth southern state to abolish the poll tax. None of these progressive reforms had been part of his gubernatorial campaign platform.

Georgia’svoting-age amendment

Arnall’s efforts to expand youth enfranchisement in Georgia can be traced to his inauguration day. In his inaugural address on January 12, 1943, he drew on a familiar argument to justify lowering the voting age. Arnall declared, “If our boys and girls at eighteen are old enough to fight and die for the freedom, liberty, and blessings that are ours today, then certainly they are old enough to participate in the affairs of the government they serve.”Footnote 71 By the next day Arnall’s ambitious legislative campaign had begun. His administration introduced sixty bills in the state legislature, including an amendment to the state constitution lowering the voting age from twenty-one to eighteen years of age.Footnote 72

Unlike many other southern states during this period, when Arnall was elected to office, Georgia was a so-called strong governor state.Footnote 73 As the state’s powerful executive, he was able to effectively dominate the state’s General Assembly. Traditionally, in Georgia, the governor handpicked the presiding officers of both houses of the legislature, and Arnall continued that practice during the 1943 session. He chose Roy Harris, who had played a crucial role in his election, as his candidate for Speaker of the House.Footnote 74 He selected another close supporter, Frank Gross, as his candidate for President of the Senate. Both were elected unanimously. After assembling his team, reports suggest that Arnall “skillfully pressured the legislature into adopting his entire program, most of which it did within a few weeks by unanimous vote.”Footnote 75 This included adopting a resolution of support for the war effort, freeing the state university system from political control, creating a teacher retirement system, and eliminating the governor’s control over the attorney general.Footnote 76 After these bills were considered and approved, the legislature turned to the bill lowering the voting age. This was the first time that Arnall’s agenda met strong opposition, but he was not deterred. Arnall had predicted that youth enfranchisement would be “the liveliest issue of [the] session.”Footnote 77

Voting Amendment in the State Senate

When the Senate Constitutional Amendment Committee met to vote on the voting age bill, Arnall appeared before them and expressed his support for youth enfranchisement. As his principle reason for initiating the reform, he cited “the fact that if young men of [eighteen] were old enough to fight for their country, then they were old enough to voice their opinion in public matters.”Footnote 78 In response, the committee unanimously approved the bill.Footnote 79 Then, before the bill was introduced in the full Senate, Arnall met with the senators who remained reluctant in order to convince them of its importance. Opponents, especially Senator W. W. Stark, charged that the proposed amendment “would enfranchise young blacks and ‘mix politics up in every high school and college in Georgia.’ Senator Stark asserted that Arnall never would have been elected if he had advocated such a proposal in the primary election.”Footnote 80 Ultimately, despite garnering some criticism, the Senate quickly passed the voting age bill on February 11, 1943 with 39 members voting “for” and 8 “against.”Footnote 81 The resolution, having received over the requisite two-thirds majority, was adopted. Upon hearing news of the bill’s success, Arnall commented that he was “pleased as a pickle.”Footnote 82 More important, he pledged to continue to fight for the bill’s passage in the state House.

Voting Amendment in the State House

In the House, influenced by a pro-Talmadge contingency, the voting amendment encountered much stronger resistance than it had in the Senate. Drawing on familiar concerns, Representative J. Robert Elliott, Talmadge’s former House floor leader, led the attack. He “denounced the amendment, charging that it had the support of the Communist party. He warned that the amendment would enfranchise all of the state’s young people, ‘regardless of their race or whether they had paid their poll taxes.’”Footnote 83 Initially, the antiamendment forces prevailed. On its first vote in the House on March 2, 1943, with 125 “ayes,” 60 “nays,” and 21 abstentions, the amendment failed to attain the support of the required two-thirds majority of all members of the House.Footnote 84

Although this was Arnall’s first defeat during the 1943 legislative session, the setback was temporary. Supporters of the amendment moved to have the bill reconsidered the following day, and Arnall was committed to garnering the support necessary for reconsideration. Arnall “expressed a great ‘personal interest’ in the amendment,” and “sent, at his own expense, telegrams to all members not voting [on the amendment] urging their support, and telegrams to the 125 who did vote for it thanking them for their support.”Footnote 85 Arnall vigorously lobbied for passage of the amendment when it came up for reconsideration the next day. As part of these efforts, Arnall “arranged for the Veterans Hospital to send to the capitol many busloads of wounded young veterans. Some were in wheelchairs, some were maimed, some were minus arms or legs. These disabled veterans filled the capitol. Arnall then addressed the legislature and said that it was unconscionable to tell these young men under twenty-one that although they had fought for our country and were maimed for life, Georgia would deny them the right to vote at eighteen.”Footnote 86 Upon reconsideration, on March 3, 1943, the House passed the bill with 149 “ayes” to 43 “nays,”Footnote 87 and Governor Arnall reportedly signed the bill within half an hour.Footnote 88

Voting Amendment Faces the Public

According to state law, after being approved by a two-thirds vote in each chamber, constitutional amendments had to be submitted to Georgian voters for ratification at the next scheduled election following the legislative session that proposed the amendment.Footnote 89 This meant that Georgia’s voting-age amendment was scheduled to be voted on during the general election in November 1944. Instead of following this timeline, however, Arnall sought rapid adoption. Almost immediately after the amendment’s passage in the House, Arnall began urging the legislature to call a special election to allow the voters to quickly decide its fate. Speaker Harris agreed; arguing that “it would permit voters to consider the proposed amendments without them becoming entangled in the politics of the 1944 presidential election.”Footnote 90 The ratification election was scheduled for August 3, 1943.

In the months before the special election, Arnall reiterated his dedication to the cause. He “promised to fly the banner of youth from every pine stump in Georgia if necessary to extend the ballot franchise.”Footnote 91 He offered $100 of his own money for the best six-word slogan in support of the voting amendment, and ran a contest for the best fifty-word essay in favor of the amendment.Footnote 92 Newspaper coverage of the voting amendment routinely commented on its importance to Arnall. He was regularly cited as supportive of the bill throughout news coverage of youth enfranchisement and was touted for “crusading for the youngsters’ right to vote.” Articles referred to the voting amendment as Arnall’s “pride and joy,” “one of the chief pieces of legislation” that he wanted to see enacted, and “his pet amendment.”Footnote 93

Despite Arnall’s enthusiasm, the amendment faced strong public opposition. Many argued that it would destroy parental control over their children and divert students’ minds from school matters.Footnote 94 Arnall continued to fiercely defend the amendment. He tapped into lingering anti-Talmadge sentiment by claiming that Talmadge and his supporters had singled out the voting amendment as their object of attack. Then, on August 1, 1943, two days before the special election, Arnall went on the radio to urge for its passage. In a statewide radio broadcast, Arnall claimed that the voting amendment was “very close to [his] heart.”Footnote 95 Then, he reiterated the military argument, noting the sacrifices the youth were making for the war effort and stating: “Today, every popular song on the radio, every glance inside a factory or office, every troop train that passes, every casualty list that is published, reminds us that these young men and women are taking their place in this war shattered, flaming world with intrepid courage, with fervent patriotism, and with quite good sense.”Footnote 96 Arnall continued by reading an essay written by a wounded veteran who was too young to vote, which stated: “I am a native Georgian. I was present at Pearl Harbor and participated in the Coral Sea battle. I have been wounded twenty-two times fighting for my country. I am under twenty-one. Is there any Georgian who can conscientiously deny me the right to vote and participate in the government for which I was willing to die? Those from eighteen to twenty-one who are fighting for our government are entitled to vote for it.”Footnote 97 Arnall concluded his argument for youth enfranchisement by reminding the listeners of Georgia’s “need for idealism,” and for “the candor, and the unselfishness of those young people’s influences in our public affairs,” in short, for “the starry-eyed enthusiasm of youth.”Footnote 98

On August 3, 1943, the voting-age amendment was put to a vote before the state electorate. It passed with a two-to-one margin (42,284 to 19,682 votes), carrying 128 of Georgia’s 159 counties.Footnote 99 Interestingly, the amendment, listed fifth on the ballot, was one of twenty-eight constitutional amendments being voted on during the special election. This might seem like an uncharacteristically large number of amendments; however, Georgians routinely voted on numerous constitutional amendments during the period. Over the sixteen elections held between 1930 and 1958, 474 amendments were voted on—with an average of twenty-nine amendments on the ballot per election throughout the period.Footnote 100 Indeed, in the previous election, held on June 3, 1941, there were an impressive seventy amendments on the ballot. Yet, even with the large number of issues on the ballot, voter turnout in the August election was fairly low. At the time, Georgia voter registration was estimated at 425,000; yet, turnout during the August election garnered less than half the votes of the previous gubernatorial or presidential elections.Footnote 101

Despite Georgian voters’ familiarity with the amendment process, one might wonder whether any of the other amendments on the ballot drove interest in the 1943 election. Perhaps voters were turning out for something other than the voting-age amendment, and it was passed secondarily to another measure. Of the issues considered alongside the voting-age amendment, sixteen had a statewide effect whereas the remaining twelve were county or district specific. The subject matter of the amendments ranged from establishing a Board of Regents for the state’s university system to creating a state game and fish commission to fixing the start date for General Assembly sessions to lowering the state voting age. There was an average of 56,859 votes received across the twenty-eight amendments. The voting-age amendment received the second-to-highest total number of votes (61,966) of the twenty-eight. An amendment, listed fifteenth on the ballot, providing “that revenue anticipation obligations shall not be deemed debts of or to create debts against the political subdivisions issuing such obligations” garnered the highest vote total (65,412).Footnote 102 Further, the twenty-seventh amendment on the ballot—which called for placing more power into the hands of the state Board of Regents and taking it out of the hands of the governor—did not receive a disproportionate number of votes. In addition to the amendments, there were also elections for the solicitor generals of Chattahoochee, Coweta, and Dublin counties on the ballot. This is a position akin to a county-level district attorney, and it was unlikely to seem of great relevance to the statewide constituency. Thus, it does not seem that any of the other issues under consideration in the special election fueled the passage of the voting-age requirement. The successful passage of Arnall’s voting-age amendment seemed distinctively earned.

Immediately following the amendment’s victory in Georgia, Arnall reaffirmed his commitment to expanding youth enfranchisement. He announced that he would campaign nationally for youth enfranchisement. Indeed, most accounts of Arnall’s approach to politicking reference his attention to national politics. As such, it is unsurprising that he insisted that a similar voting amendment should be part of the Democratic Party’s 1944 national platform.Footnote 103 On October 20, 1943, Arnall appeared before a subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee to advocate for a national voting-age amendment, and his commitment to broadening youth enfranchisement was widely touted. For example, Senator Van Nuys (D-IN) predicted that Georgia’s action would prompt similar change at the federal level, and The Augusta Chronicle attributed many of the actions in various state legislatures to Arnall’s ongoing campaign.Footnote 104 Of course, history reveals that most of the attempts to lower the voting age pursued by Congress and several states during the years following Georgia’s success were unsuccessful; yet, Arnall’s support of the legislation never wavered.Footnote 105

A Favorable Combination of Entrepreneurialism, Bifactionalism, and Timing

There is little doubt that Arnall’s support of the reform was critical to the voting age being lowered in Georgia in 1943. As described in the legislative history above, Arnall was central to the movement from inception to ultimate passage, and after having achieved success in his state he even pushed for youth enfranchisement outside Georgia. Indeed, one member of the Georgia House of Representatives “attributed to the mind of one man—Ellis Arnall—the origin of the proposal for youth enfranchisement,”Footnote 106 and an article in The Augusta Chronicle described Arnall’s actions as “the instrumentality through which our younger citizens were given the right and the responsibility to participate in the selection of public officials and in the settlement of public issues.”Footnote 107

In this section, I explore the political underpinnings of the reform effort and examine why Arnall was so steadfast in his commitment to youth enfranchisement in Georgia. If Arnall’s support of the legislation was the central reason that the voting age was successfully lowered in Georgia, and history suggests this was the case, then one wonders why he was such a strong champion of the movement. That is, why did Arnall pursue youth enfranchisement, and did his attention to the issue represent something broader about Georgian politics at the time?

Arnall: A Political Entrepreneur

At least on the surface it seems that Arnall pursued the voting-age amendment as an extension of his dedication to bring so-called good government to Georgia. Arnall’s rhetoric in support of the reform was also congruent with his personal beliefs and values. Arnall was widely known as “an advocate for an intensely democratic view of southern heritage,” which “included expanding participation in the political process and enhancing the sophistication of the electorate through education.”Footnote 108 This philosophy was demonstrated in various ways throughout his governorship. For example, beyond his efforts to lower the voting age, Arnall also championed the abolition of the poll tax in the state and the ability for soldiers stationed abroad to vote in local elections. Although one might argue that Arnall’s political cries for “good government” were merely veiled attacks waged against the traditional political forces, his actions as governor reflected a consistent view that progressive reforms—namely, those leading to more, rather than less, inclusion in electoral politics—were desirable.

Of course, electoral reform is complicated. One does not usually advocate for a reform unless the outcome of the proposed change is at least conditionally known and appears favorable to the candidate and/or his party. For example, contemporary media and scholarly discourse about redistricting, voter registration reform, and early voting propose a partisan calculation beneath the surface. Strategically, candidates for office, and the parties they are associated with, will only seek to expand the electorate if they think it will benefit them, or at a minimum, will not help their opponents. Thus, it seems likely that Governor Arnall—and his supportive anti-Talmadge faction—pursued the voting-age reform strategically and with some electoral gain in mind. This suggests that Arnall’s political ambition and the growing bifactionalization of the Georgian Democratic Party also contributed to the reform’s inception and eventual success.

Further, the successful passage of Georgia’s reform is even more interesting when one recognizes the absence of a boisterous lobby in favor of the change. Indeed, history has taught us that the franchise is typically hard fought and hard won. Research on women’s voting rights, and the extension of the right to vote more broadly, offers numerous examples of expansions to suffrage occurring only after long, tenuous, organized struggles.Footnote 109 The events in Georgia, however, are exceptional insofar as they reflect an instance where a category of disenfranchised people (e.g., Georgian youth) was enfranchised without agitating for the cause. In this sense, Georgia’s successful voting-rights amendment presents a theoretical anomaly in the fight for universal suffrage in the United States.

Ultimately, one must explain why Arnall pursued the reform, especially in the absence of an organized group demanding it, and how he was successful in getting the reform passed. In doing so, Arnall emerges as a strategic political entrepreneur.Footnote 110 The term “entrepreneur,” as defined by Sheingate, describes “individuals whose creative acts have transformative effects on politics, policies, or institutions.”Footnote 111 This concept inherently “points to a more dynamic account of politics, where actors are engaged in a constant search for political advantage and whose innovations transform the boundaries of institutional authority.”Footnote 112 As a political actor seeking to initiate and implement change, one must imagine that Arnall had something more than philosophical congruence to gain from the reform. As noted before, electoral reform, especially, is an inherently strategic, partisan, and political endeavor. I argue that although the voting reform was, in fact, consistent with his values and priorities, as an entrepreneur, Arnall championed the voting-age amendment after being elected governor in hopes of (1) expanding his political base, and (2) as a token of appreciation to those who had helped him secure victory during the 1942 campaign.

Expanding His Political Base

First, Arnall supported the voting-age amendment in order to increase his political base by expanding the voting-eligible population in the state with sympathetic individuals. In this way, his actions can be viewed as being both principled and pragmatic, as Arnall aimed to build his supporting coalition in advance of his planned reelection bid. This motive was suspected during the debate over the amendment in the state legislature, with some wondering whether Arnall supported the amendment because he “anticipate[d] building himself a stronger political machine in Georgia.”Footnote 113 In his testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Georgia’s Assistant Attorney General Paul Rodgers also expressed this theory, noting that Arnall “was quite liberal and … wanted to inject into the electorate a younger age group in the hope that it would help him politically.”Footnote 114

Although the notion that Arnall pushed to extend the franchise in order to expand his political base seems likely, limited voter-turnout data make the effects of this argument difficult to substantiate. Because the U.S. Census Bureau did not report statistics on 18-to-20-year-old voters before 1964, one has to rely on secondary reports to evaluate whether these newly enfranchised individuals actually voted in large numbers during subsequent elections. Anecdotally, Cultice reports that after gaining the franchise in August 1943, many of Georgia’s 18-to-20-year-olds participated in a year of statewide school-oriented voter-training programs, and then, in November 1944, turned out in record numbers to cast ballots during FDR’s historic fourth-term election. He notes that in this election “more than 50% of Georgia’s newly enfranchised voters registered to vote, and 67% of those registered cast ballots; percentages that closely paralleled those of adult registrants and voters.”Footnote 115 Indeed, Figure 3 shows a substantial increase in voter turnout rates in Georgia during the 1944 senatorial general election (up from 3 percent in 1942 to 14 percent in 1944); however, these aggregate data do not indicate what groups or individuals the increase occurred among. Further, as shown in Figure 1, voter turnout rates were also quite high during the 1946 gubernatorial primary election (up from 17 percent in 1942 to 35 percent in 1946), but again the data cannot indicate who the increase occurred among.

It is also important to note that after Arnall’s gubernatorial term ended in 1947, he never held public office again. Yet, evidence suggests that at the time he pursued the voting-age amendment he planned to seek another term as governor, and he imagined that he would have a long political career both within—and perhaps even outside of—the state.Footnote 116 Ultimately, however, his political career in Georgia was cut short due to a much-contested revision of the state constitution that was implemented during his term as governor, which made him ineligible to run for reelection in 1946. Specifically, in 1941, under the new constitution, Georgia shifted from having a two-year gubernatorial term to a four-year gubernatorial term, but consecutive gubernatorial terms were no longer allowed. Arnall vehemently fought this change, and, in early 1945, almost succeeded in convincing the state legislature to amend the constitution so that governors could serve consecutive terms, but he did not prevail. The fact that he did not actually hold political office again, however, does not undermine the fact that he pursued the voting-age amendment anticipating that there would be future campaigns. Indeed, it is clear that at the time he acted in support of the voting-age reform, he imagined a long political future in Georgia.

Beyond his own personal political aspirations, the expansion of Arnall’s political base would also increase the power of the growing anti-Talmadge coalition in the state. In this way, Arnall—and by extension, the voting-age amendment—influenced the infamous 1946 gubernatorial election as well; an election that has been described as “one of the most divisive and racially inflammatory in the history of southern politics,”Footnote 117 and “a critical juncture in Georgia political history, certainly the most important contest in a generation.”Footnote 118 Specifically, in 1946, Arnall played a central role in trying to help Jimmy Carmichael, a fellow anti-Talmadge candidate, win the Democratic primary. With Arnall’s endorsement, Carmichael ran as the “good government” progressive candidate promising to protect the university system against further demise, pursue electoral reform, target corruption, and improve the state economy. Carmichael “believed that those who had only recently joined the electorate would be the force that delivered victory,”Footnote 119 and he made “a strong appeal to young voters” with several university clubs unanimously endorsing him.Footnote 120 Indeed, numerous accounts of this circuslike election point to the new youth vote as a possible factor in Carmichael’s popular vote win over Talmadge; though by winning the county unit vote, Talmadge was ultimately victorious.

A Token of Appreciation

Another related explanation for Arnall’s commitment to the voting-age amendment is that it was used as a reward for the groups that had supported him during his 1942 gubernatorial campaign. As noted before, thousands of college students participated in Arnall’s campaign and publicly despised Talmadge; and, based on this support, Novotny argues that “Arnall’s commitment to the lowering of Georgia’s voting age is quite understandable.”Footnote 121 Novotny suggests that there was a direct link between youth interest in his campaign and Arnall’s eventual commitment to expanding youth enfranchisement once in office. This view was also expressed at the time by The Savannah Morning News, which explicitly described Arnall’s support of youth enfranchisement as “an effort to show appreciation to the young people of Georgia for contributing to the success of his gubernatorial campaign.”Footnote 122

Arnall’s discussion of his support of the voting-age amendment later in his life also offers evidence for this theory. In his autobiography, The Shore Dimly Seen, Arnall noted the contribution of those under twenty-one in aiding his gubernatorial victory in 1942. He recognized that he “owed much to the audacious and vigorous campaign of Young Georgia.”Footnote 123 Arnall then recounted the story of how he came to support youth enfranchisement wherein: a nineteen-year-old campaign worker, before leaving for military training, told Arnall that he was old enough to be drafted and fight, even if he was ineligible to vote. Arnall wrote that this discussion motivated his commitment to lower the voting age once in office.

The argument that Arnall’s support of the amendment was an effort to expand his political base and reward those who had helped him, albeit indirectly, gain office, begins to explain the political strategy fueling the reform effort—even in the absence of a group fighting for voting rights in the state. Even though the Georgian youth were not engaged in an organized voting-rights lobby at the time that Arnall proposed the legislation, college students, especially, were: (1) mobilized by his candidacy against Talmadge following the university-system crisis, (2) widely involved in his gubernatorial campaign, and (3) poised to continue to provide an area of political strength for him (and presumably the other members of the anti-Talmadge faction) going forward.Footnote 124 Additionally, the intraparty factionalism present in Georgian politics at the time was also quite important to the story. Together, these elements combined to provide the favorable conditions for the amendment’s eventual success in an otherwise hostile, limiting, racist political environment.

Challenging the “Old Guard”

In addition to helping build a supportive electoral coalition, one must appreciate the amendment’s success in relation to the volatility of Georgian politics and the importance of timing in Arnall’s efforts toward reform. Specifically, Arnall was elected governor during a period of bifactional competition “made up of Talmadge and his followers on one side and his opponents on the other.”Footnote 125 The voting-age amendment represented an affront to the “old guard,” Talmadge-centric politics in Georgia, and the reform’s success was made possible, at least in part, because of the growing anti-Talmadge faction in the state. This suggests that ultimately, Arnall was successful because he pursued the voting-age reform—a reform that he and his fellow anti-“old guard” partisans would benefit from electorally—at a time of rampant public unrest with the status quo. Moreover, as noted by Patton, “the decades between 1930 and 1950 saw the birth, short life, and ultimate demise of a particular form of liberalism in the American South. During those years, many of the region’s liberals adopted, and acted upon, a radical approach to the South’s problems.”Footnote 126 It follows that during this time, Governor Arnall was described as one of the “most outspoken liberal-nationalists”; yet, former governor Eurith (Ed) Rivers had set the stage for a more progressive and inclusive Georgia several years before.

Rivers was Georgia’s governor from 1937 to 1941, before Talmadge served his second term, and before Arnall was elected. Rivers won the governorship on the strength of his pledge to bring a “Little New Deal” to Georgia by complying with federal regulations, accepting New Deal programs, and supporting many expansive state-building plans. Despite Rivers’s progressive vision for his state, he was unable to succeed. Georgia did not have the funds to support his lofty goals, and when Rivers left office “the state had a deficit of $14.5 million and future maturing obligations of $38.5 million.”Footnote 127 Also, his reputation and political capital were marred by charges of corruption and mismanagement during his second term in office; and, during his final year in office, a federal grand jury indicted four members of his administration for conspiracy to defraud the state. The grand jury indictments, combined with allegations that Rivers had sold pardons while he was governor, destroyed his reputation.Footnote 128 Ultimately, Rivers’s plans to bring New Deal liberalism to Georgia would have to wait for Arnall.

As governor, Rivers, and eventually Arnall, stood opposed to the entrenched “old guard” politics of Eugene Talmadge’s Georgia. Talmadge was a formidable Georgian politician. He was a candidate in all but one statewide Democratic primary between 1926 and 1946; and, notably, the 1942 election was the single exception of Talmadge running for governor and not winning. Over his many years in office, Talmadge favored restricted state services, a limited use of governmental powers, and white supremacy, while staunchly opposing organized labor. These positions “found him favor with the highest economic forces in the state.”Footnote 129 Talmadge also “viciously exploited ancient prejudices against Negroes and cities in appealing to the rural constituency which kept him in office.”Footnote 130 Indeed, Key described Georgia’s Talmadge and anti-Talmadge cleavages as dividing between the counties that were completely rural and supported the former and those that had large cities and supported the latter. Unlike Georgia’s brief entrée into New Deal liberalism during Rivers’s time as governor, during Talmadge’s terms as governor there were no notable policy initiatives. Instead, as discussed by Mickey, the Talmadge years “were marked by severe fiscal mismanagement, staunch opposition to the New Deal and governmental reforms, the use of the state’s coercive apparatus to intimidate political opponents, and the personal manipulation of state agencies.”Footnote 131

By the early 1940s, however, Georgia, and most of the Deep South for that matter, began to experience unrest with the political establishment. Despite the prominence of the Democratic Party in the region, intraparty factionalism began to take shape. According to Mickey, “The Deep South’s sharpest factional conflict existed within Georgia’s ruling party. Eugene ‘Gene’ Talmadge, a charismatic white supremacist demagogue, led a coalition of county courthouse rings and poorer white farmers against a much less cohesive ‘anti-Talmadge’ faction of so-called urban moderates and progressives across the state.”Footnote 132 In turn, the two most influential anti-Talmadge leaders were former Governor Ed Rivers and gubernatorial candidate Ellis Arnall. By capitalizing on increasing dissatisfaction with the “old guard” and the Talmadge administration’s mishandling of the state’s university system, Arnall offered something new to Georgians. He had the potential to redirect Georgian priorities—and at the very least offered them a welcome reprieve from several long years under the Talmadge regime.

It was within this context of political unrest and intraparty factionalism that Arnall was elected as governor. While he could have simply settled for being the man “who saved Georgia from Talmadge-ism,” Arnall pursued several progressive policy reforms as governor, one of which was the voting-age amendment. Committed to the promotion of good government, Arnall offered the idealism of democracy as the answer to the southern problems that were perpetuated by the “old guard.” This included expanding participation in the political process. As Key noted, Arnall “brought to office administrative reforms, constitutional revision, and a dignity refreshing to many of his fellow citizens. He acquired a national reputation for liberalism, and, most remarkable of all, he dared to be fair on that nemesis of southern liberals, the rights of Negroes.”Footnote 133

Yet, Arnall’s affront to the “old guard” was not sustainable. Describing the anti-Talmadge forces as “more of a response than an independently created political organization,” Bullock et al. note that Arnall was “outmatched by the cohesive factional identity of the Talmadges.”Footnote 134 Although Arnall managed one of the most competent administrations in Georgian history, his popularity in Georgia declined throughout his term. The national accolades he gained from the liberal media, his enlightened racial views, his support of Henry Wallace, and his refusal to defend the white primary alienated many of his more traditional supporters. Then, his unsuccessful attempt to amend the constitution so that he could serve a second term proved divisive.

Many also suspected that Arnall’s continued commitment to pursue the voting-age reform nationally was related to his future political aspirations, including “hopes that he would be tapped as the 1948 Democratic vice presidential candidate.”Footnote 135 In this regard, being a first-mover on the youth vote helped him signal to national party leaders that he was a “true Democrat,” while also maintaining institutions that would not offend his conservative base and southern sensibilities regarding desegregation and white supremacy. This was even more important given the national coalitions of the time, and with non-southern Democrats becoming increasingly impatient with segregation in the South. Given these partisan shifts, it would have been important for Arnall to send these sort of signals if he had any real interest in participating in national politics. Further, it also seemed that his national ambitions might have shaped his decision to give up the fight regarding the white primary, which would have otherwise required noncompliance with federal court rulings. Ultimately, although he proved too progressive for Georgia at the time, Arnall’s demonstrated progressivism with regard to the youth vote did set him apart on the national scene and in the national press.

Racially Charged Politics in Georgia