The predominance of Whiteness, and the corresponding lack of representation of people who are both racialized and minoritized, in the governance of universities is a political issue.Footnote 1 Representation in political, economic, social and cultural institutions is an expression of power. With respect to institutions of higher learning, it is an expression of power over who is included in or excluded from university leadership opportunities; over the ideas, interests and perspectives that are brought to bear on decisions related to the advancement of knowledge; and over the social meanings of competency, ability and suitability to govern knowledge-generating and knowledge-legitimating institutions. In other words, who is represented—and who participates—in these forums of power is a matter of justice, knowledge and social meaning.

Indeed, drawing from writings on women and political representation, Anne Phillips notes that one of the “most powerful arguments for gender parity is simply in terms of justice: that it is patently and grotesquely unfair for men to monopolize representation” and that any “distorted distribution of political office is evidence of intentional or structural discrimination” (Reference Phillips and Phillips1998: 229; see also Phillips, Reference Phillips1991). Iris Marion Young (Reference Young2002) and Jane Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge1999) also contribute to arguments for more proportional representation by highlighting benefits such as the enlargement of the range of social perspectives and enhancement of deliberative quality in collective decision making. Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge1999) also notes the significance of symbolic representation for the social construction of who is best able and most desirable to govern. These arguments were made primarily with reference to gender, but they apply also to racialized identities.Footnote 2 And although they were made primarily in relation to elected offices, they can be applied to many entities with the power to make far-reaching decisions that are binding of, or that have consequences for, a social collectivity.

In this article, we present the results from an intersectional diversity audit, which is a methodology similar to that developed by Malinda S. Smith (Reference Smith2016, Reference Smith, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017a, Reference Smith2017c, Reference Smith2019) of academic administrators at five Canadian universities. Our analysis builds on Smith's approach in both methodological and substantive terms. Methodologically, we engage in a multiphased process of coding involving several coders, which enables us to determine the interrater reliability for our findings. Substantively, our analysis extends from the entry level (that is, departmental program chairs) to the highest echelons of university administration (that is, the senior executive). Arguably, the academic administrative career ladder begins within the departments. Our analysis enables us to examine progress up this ladder, from its lowest to highest rung. This enlarged focus enables us to identify if certain administrators are hitting ceilings and if these ceilings are at different heights.

Our data set is relatively large, containing 1,299 profiles of central and senior administrators from Simon Fraser University, University of British Columbia, University of Toronto, University of Victoria and York University. Relative to Statistics Canada census data on professor and lecturer income recipients, we find that White men are significantly overrepresented across all administrative ranks. Perhaps a surprising finding is that White women appear overrepresented among senior executives and associate deans and they appear represented among deans about on par with what we would expect from the census data. On the whole, our findings suggest that, while White men have easy access to all administrative ranks, and while White women appear to be making it through to senior administrative ranks, racialized women and men are getting stuck in the middle ranks. Our main contribution to understanding diversity gaps within university administration is that we identify different ceiling heights corresponding perhaps more to racialization than to gender.Footnote 3

We begin with a discussion of the politics of demographic data collection, including resistance to collecting intersectional demographics that can be cross-tabulated with administrative rank. We then discuss our methodology and present our findings. While our study has its limitations, we believe that it is an important contribution to a growing body of data and analysis speaking to diversity gaps and the predominance of Whiteness within the governance structures of universities.

The Politics of Demographic Data

The determination of racialized categories is political, as Debra Thompson (Reference Thompson2008, Reference Thompson, Papillon, Turgeon, Wallner and White2014, Reference Thompson2015, Reference Thompson2016) and others (for example, Brown, Reference Brown2016; Omi and Winant, Reference Omi and Winant1994; Pascale, Reference Pascale2006; Potvin, Reference Potvin2005; Prewitt, Reference Prewitt2013) have noted. The same is true of sex and gender categories, which is also well documented (see, for example, Butler, Reference Butler1990; Foucault, Reference Foucault1985; Lorber, Reference Lorber and Grusky2018; Rubin, Reference Rubin, Nardi and Schneider1984). Although the ascription of race and gender, and their documentation in demographic censuses, is problematic, such data are crucial to evidence-based policy. While the use of these data can be motivated to serve particular—as opposed to collective—interests, so too can explicit and implicit refusals to collect these data. Delia D. Douglas, for example, argues that the reluctance of universities to collect and/or report comprehensive data on racialized minority groups “undermines conversations about equity while simultaneously validating public discourses which posit that race is no longer relevant and that racism is not an issue in Canada” (Reference Douglas, Gutierrez, Muhs, Niemann, González and Harris2012: 55). Not collecting and/or not sharing data can, effectively, be a form of resistance to prospective practices and policies that are based on evidence and that can better address racialized and gendered forms of exclusion, marginalization and other inequities.

There is broad agreement in the literature focussing on equity, diversity and inclusion in places of work that accurate demographic data are critical in identifying barriers to participation and advancement in public and private institutions (see, for example, al Shaibah, Reference al Shaibah2014; Bates et al., Reference Bates, Roche, Cheff, Hill and Aery2017; Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, Smotherman, Dziurzynski, Love, Kilmer, Niemann and Ruggero2018; Malik et al., Reference Malik, Johri, Handa, Karbasian and Purohit2018; Momani et al., Reference Momani, Dreher and Williams2019; Mowatt et al., Reference Mowatt, Johnson, Roberts and Kivel2016; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Marschke, Sheff and Rankin2005; Nieuwenhuis et al., Reference Nieuwenhuis, Need and van der Kolk2012; Ornstein et al., Reference Ornstein, Stewart and Drakich2007; Weinberg, Reference Weinberg2008). Fifteen years ago, the Ontario Human Rights Commission determined that “appropriate data collection is necessary for effectively monitoring discrimination, identifying and removing systemic barriers, ameliorating historical disadvantage and promoting substantive equality” within workplaces (2005: 42). Yet there is little consistency among organizations in terms of data collection and dissemination. While third parties in both public and private sectors collect and report data on gender and racialized identities (see, for example, Bloomberg, n.d.; CAUT, 2018; Curtis, Reference Curtis2011; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Cooper, Konar, Bohrer, Mohsenin, Yee, Krivkovich, Starikova, Huang and Zanoschi2019; Universities Canada, 2019), there is little consistency in terms of their release (Dhir, Reference Dhir2015; Henry and Kobayashi, Reference Henry, Kobayashi, Choi, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017a; Melloni et al., Reference Melloni, Caglio and Perego2017; Stolowy and Paugam, Reference Stolowy and Paugam2018).

Although Canadian universities should collect and report these data, they do not do so systematically.Footnote 4 The Employment Equity Act (1995) requires federally regulated companies with more than 100 employees to report on the employment representation of, and their attempts to ensure equity for, four groups: women, Aboriginal peoples, persons with disabilities, and visible minorities. The Federal Contractors Program (2018) requires employers that receive funding from the federal government, as universities do, to collect data, set numerical goals and make reasonable progress toward the full representation of these designated groups. But, as Frances Henry and Audrey Kobayashi write, “in recent years the compliance regulations have been revised and the federal government no longer makes any attempt to compile or communicate the results” of employment equity reporting (Reference Henry, Kobayashi, Choi, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017a: 27). Compliance requirements for the Federal Contractors Program are effectively “nonexistent” and “very few universities generate helpful data reports” (Reference Henry, Kobayashi, Choi, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017a: 27).Footnote 5

Another possible, but insufficient, source of data is the University and College Academic Staff System (UCASS) run by Statistics Canada. This system reports data on the gender of full, associate, assistant, and below-assistant-level full-time professors; on deans, vice-deans, associate deans and assistant deans; and departmental chairs. UCASS data are available by specific institution, if the institution gives permission. However, UCASS does not collect data by racialized categories.

Recently, Universities Canada (2019) released its results from a national survey focussing on equity, diversity and inclusion. The results are limited in at least two ways. First, they refer only to the senior leadership, including deans, vice-presidents, provosts and presidents; they do not enable us to identify patterns in progress through the pipeline from central to senior administrative position. Second, they focus primarily on single-dimension categories of identity (for example, women, Indigenous, racialized people, LGBTQ2S+ people or persons with disabilities). The Universities Canada report provides an intersectional category for respondents who identify with “two or more designated groups,” but the report does not provide details on the distribution of combinations. The intersectional data on both gender and racialized identity that are presented are not cross-tabulated with administrative rank. All of this is consistent with Henry and Kobayashi's observation that when it comes to racialized faculty members at individual universities, these data are “extremely difficult” to obtain (Henry and Kobayashi Reference Henry, Kobayashi, Choi, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017a: 26).

The Canadian Census offers better but still limited data. The census includes data on the labour status and income of university professors and lecturers, which can be analyzed through an intersectional lens for both gender and racialized identity. These data, however, are aggregated in terms of both full-time and more contingent academic staff. Moreover, they are not linked to professorial or administrative rank. As such, the employment category is too broad to get a sense of where representational gaps may exist. As we discuss later, while Statistics Canada data are insufficiently disaggregated, we use them for broad comparator purposes.Footnote 6

Important attempts have been made by scholars to address this insufficiency of publicly available demographic and employment data from Canadian universities. A number of such studies involve data collected by Statistics Canada, as well as data collected from targeted surveys (see Abu-Laban et al., Reference Abu-Laban, Everitt, Johnston and Rayside2010; Abu-Laban et al., Reference Abu-Laban, Everitt, Johnston, Papillon and Rayside2012; Momani et al., Reference Momani, Dreher and Williams2019; Ramos and Li, Reference Ramos, Li, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017; Ramos and Wijesingha, Reference Ramos, Wijesingha, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017). However important these studies are, they have limitations. For example, Yasmeen Abu-Laban and her colleagues (Reference Abu-Laban, Everitt, Johnston, Papillon and Rayside2012) conducted demographic surveys of all political science chairs and professors belonging to the Canadian Political Science Association, but their efforts were hampered by a low response rate and the non-existence of department data. Working with Statistics Canada data, Howard Ramos and Peter S. Li (Reference Ramos, Li, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017) produced results examining discrepancies between the general population of visible minorities, those earning doctorates, and those working as professors. Overall, they found that visible minorities—again, a Statistics Canada category—are underrepresented in academia when the relevant data are compared to the data on the general population and on doctorate degree holders (48–55). These findings are consistent with an earlier study by Ramos showing that “no matter how representation is measured, visible minorities are underrepresented” among the professoriate in Canada (Reference Ramos, Li, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017: 55; see also Ramos, Reference Ramos2012). But this study is limited by the unavailability of data on racialized people as disaggregated by professorial and administrative rank.

Other scholars have employed more qualitative methods to obtain a better understanding of the demographics of professors as well as the experiences of racialized university staff (see, for example, Deem and Morley, Reference Deem and Louise2006) and faculty members (see, for example, Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2012; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Dhamoon and Moy2014; Hames-García, Reference Hames-García, Little and Mohanty2010; Harris and Gonzáles, Reference Harris, González, Gutierrez, Muhs, Niemann, González and Harris2012; Henry et al., Reference Henry, Dua, Kobayashi, James, Li, Ramos and Smith2017; Henry and Kobayashi, Reference Henry, Kobayashi, Choi, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017b; Hirshfield and Joseph, Reference Hirshfield and Joseph2012; James, Reference James, Chapman-Neyaho, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017; Mahtani, Reference Mahtani2004; Monforti, Reference Monforti, Gutierrez, Muhs, Niemann, González and Harris2012; Settles et al., Reference Settles, Buchanan and Dotson2019; Smith, Reference Smith, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017a). As Michael Hames-García argues, these studies are important because they can help those in decision-making positions avoid prioritizing “diversity for diversity's sake” (Reference Hames-García, Little and Mohanty2010: 58). With an understanding of experiences, meaningful changes can be taken to tackle the barriers and better enable minoritized individuals not merely to be included but also to thrive in the university workforce and in the governance of academia. While fundamentally valuable in understanding and addressing discrimination in the workplace, without more quantitative studies providing baseline intersectional demographic data, these qualitative investigations have significant limitations.

Diversity Audits (and Their Limitations)

In order to get baseline demographic data that account for gender and racialized identities, we develop the methodology employed by political scientist Malinda S. Smith (Reference Smith2016, Reference Smith, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017a, Reference Smith2017c, Reference Smith2018, Reference Smith2019; see also Griffith, Reference Griffith2016; Henry and Kobayashi, Reference Henry, Dua, Kobayashi, James, Li, Ramos and Smith2017; Nakhaie, Reference Nakhaie2004). Smith uses an “equity audit” method to determine gender and racialized diversity at various levels of administration in Canadian universities. She uses a data triangulation method that involves analyzing publicly available materials, such as photographs, first and last names, and personal and professional biographies (including Indigenous self-identification). Smith determines whether individuals present—and, where possible, determines whether individuals self-identify—as White, visible minority, or Indigenous. She also determines gender expression as man or woman. Drawing on Kimberlé Crenshaw's (Reference Crenshaw1991) work, Smith employs an intersectional analytic sensibility to highlight racialized peoples within the categories of gender. Smith's work renders it clear that it is only by collecting and analyzing data for both the gender and racialized identity of individuals that we can see if men and women of colour are fairly represented through professional ranks. For her recent study on leadership diversity, Smith collected data on the senior administrators of the 15 research universities, including board of governor chairs, presidents, provosts, and vice-presidents (academic), vice-presidents (research), and members of the presidents’ leadership team. Her analysis indicates that the gender gap of these individuals is largely closing, while the racialized gap remains as large as ever.

Some may view this equity audit methodology as less optimal than one that involves collecting and analyzing purely self-identification data. This view can be challenged. Many individuals in leadership roles choose to make available their headshots, and this methodology captures how these images are visually interpreted. The very concept of “visible minority” refers to a visual construct. Gendering and racializing are, in large measure, visual processes. As such, the methodology is valid in terms of capturing how identities are visually perceived. Many, moreover, write their own publicly available biographical statement, which contains self-identified characteristics, such as pronouns. Again, this methodology captures what is publicly presented by people in leadership roles. Nonetheless, since it is not based directly on self-identification, it is prone to certain errors. There is the possibility, for example, that people will be misgendered, which would not be an issue in methodologies using self-identification data collection. It is possible that people will be racialized as being “of colour” when they are White and vice versa. While the triangulation employed by Smith and others minimizes these errors, self-identification methods avoid this entirely. That said, self-identification methodologies are prone to other types of weaknesses, such as low response rates.

We have chosen to employ and build on this equity audit methodology because of the importance of systematically collecting demographic data that are intersectional and that can be disaggregated by professional rank, which in turn can help to identify equity barriers in the participation of members of racialized and minoritized groups in the governance of Canadian universities. We collected these data only from members of the central and senior administrative ranks, who are, by definition, taking a public role and who wield considerable power over the production of knowledge and legitimation of social meaning. If universities are not making intersectional data from self-identification surveys that include professional rank publicly available, this should not impede this type of investigation.

Data Collection, Analysis and Accountability

The intention behind our analysis was to conduct a percentage comparison between our data and the data available from Statistics Canada. Limited by resources, our study focussed on five universities: Simon Fraser University (SFU), the University of British Columbia (UBC) and the University of Victoria (UVic), all in British Columbia; and York University (York) and the University of Toronto (UofT), both in Ontario. This focus enabled us to compare the three major institutions in British Columbia, two major institutions in Toronto, two of the top-tier Canadian U15 research universities (UBC and UofT) and two highly ranked comprehensive universities (SFU and York). To explore the representativeness of our sample, one research assistant (Atchison) statistically compared the distribution of demographics and administrative ranks across the five universities. With respect to the distributions of demographics/administrative rank groupings, there were no statistically significant differences across the five.Footnote 7 Thus, our expectation is that since hiring practices are likely standard across Canadian universities, adding universities to our sample would not substantively alter our findings. We have good reason to believe that our findings are reflective of patterns we are likely to see among Canadian universities more broadly. Moreover, in light of the methodological steps that we outline below to bolster the reliability of our findings, we believe that they are notable and generalizable.

From the websites of each of these universities, we collected primary data in the form of headshots, names and biographical statements of central and senior administrators organized into five ranks (Table 1). The data collection process took place between March and August 2019. We collected data for all departments and faculties, with the exception of those located at satellite campuses (for example, UofT's Scarborough and Mississauga campuses, York's Glendon College and UBC's Okanagan campus). We excluded pharmacy, nursing, dentistry, medicine and law schools because they are often structured differently from other academic departments and because smaller institutions do not have these schools. We also excluded continuing studies or lifelong learning programs geared toward full-time employees or retirees. We believe this is the first time such a study has been undertaken in Canada. While Smith includes deans in her studies of U15 institutions, we are not aware of any other study that includes this level of granularity (that is, associate deans, departmental chairs and program chairs) in university administrative rank.

Table 1 Administrative Ranks and Brief Descriptions

We scanned each institution's website, drawing on a combination of organizational charts and institutional webpages to identify the individuals in the particular positions. Generally, senior executives and deans were easily identified on a single page. In some cases, associate deans were also available on a centralized list, but when a single list was not available, we searched for their individual webpage. For departmental chairs and directors and departmental program chairs and directors, we searched departmental and individual webpages. For each subject, we created a Word document, and about 90 per cent of these documents included both headshot and text.

The Word document for each individual included in our study was imported into a QSR NVivo project for analysis. In NVivo, the lead author (Johnson) created codes for gender expression (man, woman, non-binary and gender unknown) and for racialized identity (visible minority, White [not obviously visible minority], Indigenous and racialized identity unknown). The co-author (Howsam) and research assistants (Phillips and Ramesh) individually coded each file. In this first round of coding, the three coders worked independently in order not to influence each other's assessment of gender expression and racialized appearance. Where gender or racialized identity was not clear, the coder assigned an “unknown” code. The code for non-binary gender expression was assigned only in cases in which individual biographical or research statements included reference to their pronouns as they or their in the singular third-person. Similarly, the code for Indigenous was assigned only in cases in which individuals referred specifically to their Indigenous backgrounds. During the second phase, individual coders used forebears.io to assist in determining the racialized identity of an individual. The results of these two waves were used to calculate a measurement of interrater (or intercoder) reliability.Footnote 8 The cumulative Cohen's kappa coefficient for the coding was 0.94 (SD = 0.07), indicating a very high degree of reliability.

In the third wave, the three coders engaged in consensual coding of the files on which they disagreed. This involved careful discussions to try to reach an agreement on gender expression and racialized identity. For this final round of coding, we created non-agreement codes for when the coders could not reach an agreement. Incidentally, the non-agreement code for gender expression was not used, although the unknown code for gender expression was used once; the non-agreement code for racialized identity was used only three times. Excluding these, we report on our data set of 1,299 files.Footnote 9

Our Findings and Comparator Data

The Canadian Census, which includes professors and lecturers—that is, full-time academic staff and more contingent instructors—enables us to engage in comparisons in terms of intersectional categories. The proportion of women university professors and lecturers reported is higher in these data than in the UCASS data, since there are more women who are contingent instructors (Census 2016, reported in CAUT, 2018: 5). There may be reason to believe that the portion of racialized professors and lecturers would be higher as well, especially given the larger portion of visible minorities with earned doctorates relative to non-visible minorities (Table 2).Footnote 10

Table 2 Earned Doctorates and Professor and Lecturer Income Recipients

Source: Statistics Canada, Census 2016, Tables 98-400-X2016287; 98-400-X2016192; 98-400-X2016356; 98-400-X2016357.

a There is a 10-count discrepancy between the reported total of earned doctorates in the census and this total when disaggregated by intersectional category. Statistics Canada adds five counts to demographic and employment categories with very small numbers.

According to the most recent census (see Table 2), racialized (including visible minority and Indigenous) university professor and lecturer income recipients constitute about one-fifth of all university professor and lecturer income recipients (20.87%). In the census data, visible minority women make up about 7.16 per cent and visible minority men about 12.3 per cent of this population. Indigenous people constitute about 1.41 per cent of this population, with Indigenous women representing 0.86 per cent and Indigenous men 0.55 per cent. White women represent about 36.07 per cent and White men represent about 43.06 per cent of professor and lecturer income recipients. Women, without disaggregating by racialized status, make up about 44.09 per cent and men about 55.91 per cent of all university professors and lecturers income recipients. Relative to these data, we find notable diversity gaps in the central and senior leadership of universities in our study.

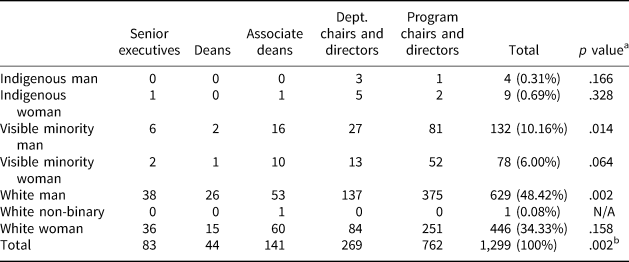

Our standout finding is that both racialized men and women are hitting a ceiling at the level of associate deans, just below the level of dean (Table 3). Visible minority men are represented among departmental program chairs and directors, departmental chairs and directors, and associate deans slightly under their representation in the census data for professor and lecturer income recipients; they are more clearly underrepresented within the ranks of deans and senior executives (4.55% and 7.23%, respectively [Table 3]). Visible minority women appear underrepresented in the ranks of senior executives, deans, and departmental chairs and directors, relative to their representation in census data for professor and lecturer income recipients. They appear most clearly underrepresented among deans and senior executives (2.27% and 2.41%, respectively [Table 3]). These diversity gaps are even more pronounced when compared to census data on earned doctorate degree holders (Table 2). Conversely, in comparison with the census data on income recipients, it appears that White women and men are being siphoned through all administrative ranks, with White women appearing to be overrepresented among associate deans (42.55% [Table 3]) and senior executives (43.37% [Table 3])Footnote 11 and represented among deans about on par with their representation in the census data (34.09% [Table 3]). They appear to be slightly underrepresented among departmental and program chairs and directors (Table 3). White men are significantly overrepresented across the total population of administrative leadership professionals (Table 4). When disaggregated by rank, they appear to be underrepresented only among associate deans. But, on the whole, White men persist in their significant overrepresentation in the central and senior leadership of universities (Table 4) relative to their representation in the data on professor and lecturer income recipients and in the data on earned doctorate degree holders. Moreover, our findings from the five institutions indicate that senior executives and deans are about 90 per cent White (Table 3), which appears to be a significant contrast with data reported by Statistics Canada on professor and lecturer income recipients and on earned doctorates and data reported by the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) on professors.

Table 3 Percentages of Administrative Positions by Racialized and Gender Identities at Five Canadian Universities (SFU, UBC, UofT, UVic and York)

Table 4 Count of Administrative Positions by Racialized and Gender Identities at Five Canadian Universities (SFU, UBC, UofT, UVic and York)

aWe derived these p values from a comparison with the census data on professor and lecturer income recipients. A key assumption we make is that these data are representative of the pool from which central and senior administrators are drawn. For all categories except White men, p values refer to the probability of drawing the observed number or lower from this pool. For White men, the p value refers to the probability of drawing the observed number or higher.

b The p value for the total refers to the single-sided chi-square test that the observed distribution would be drawn at random from census data on professor and lecturer income recipients.

Our counts for Indigenous peoples are very small (Tables 3 and 4). Indigenous men and women may be being included in central and senior administrative positions relative to their representation as professor and lecturer income recipients. But they appear to remain underrepresented in the administration of the academy relative to the representation of Aboriginal people in the labour force at 3.8 per cent, in the general population at 5.0 per cent and in the undergraduate university students who identify as Aboriginal at 5.0 per cent (CAUT, 2018: 2). Finally, although there are no census data yet available on gender non-binary people, it appears fairly clear that they are underrepresented within all administrative ranks.

The comparability of our findings with those of similar studies bolsters our claim that our results are reliable and significant.Footnote 12 Our results are consistent with those of Smith (Reference Smith2016, Reference Smith2017c, Reference Smith2018, Reference Smith2019), who examined the gender and racialized makeup of senior leadership of Canada's U15 research-intensive universities and 96 of Canada's universities. As Smith writes, senior university leadership remains “overwhelmingly white and largely male” (Reference Smith2019, sec. 1, para. 1). She, too, finds that racialized men and women appear underrepresented in these senior ranks, with racialized women especially underrepresented. As well, our findings are consistent with those of Universities Canada (2019). They find that “racialized people are significantly underrepresented in senior leadership positions at Canadian universities and are not advancing through the leadership pipeline” (10). Of their sample of senior administrators, they find racialized people constitute 8 per cent, which is very comparable to our findings. Not only are our findings comparable to other studies but they are also, in important ways, more granular. Again, our study reaches down the administrative career ladder to the very first rung and extends to the very top. We bring together two interlocking categories of analysis: gender and racialized identity. Finally, our results derive from important methodological steps, including team coding and probability tests, not seen in other such studies.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our study supports what is already well known, in large part due to the research and analysis of Smith (Reference Smith2019): White men are dominant within the administrative structures of Canadian universities. Our study suggests that, relative to the data from Statistics Canada on professor and lecturer income recipients, White women do not appear to face serious representational barriers in the ascent through the academic administrative ranks to the senior executive. In fact, our data suggest that, like White men, they are overrepresented at the senior administrative level. This finding needs to be cautioned with Smith's data indicating that the ceiling for White women is, essentially, at the presidential floor. There can be no doubt that gendered ceilings persist. But our findings serve to underscore the existence of racialized ceilings that are lower than the ceiling for White women. Our analysis, because it extends from departmental program chairs and directors to the senior executive, enables us to locate a ceiling for both racialized women and men just below the level of deans. Our analysis indicates that representation is basically what we would expect based on Statistics Canada data for White women and both racialized women and men in the central administrative ranks. However, our data also indicate that something is blocking the entrance of racialized men and women into senior administrative roles, while White men and women are entering those roles just fine.

As discussed in the introduction, distortions in representation must be taken as issues of justice. As Phillips (Reference Phillips1991) argues, patterns of over- and underrepresentation suggest intentional or structural discrimination. As stated by the Ontario Human Rights Commission: “Numerical data showing an underrepresentation of qualified racialized persons in management may be evidence of employment systems that have the effect of discriminating and/or of decision makers having an overt bias toward promoting White candidates into supervisory roles” (2005: 32). Would it be surprising if various forms of discrimination were functioning to create the patterns we observe (see Stewart and Valian, Reference Stewart and Valian2018: 42; see also Hames-García, Reference Hames-García, Little and Mohanty2010; Mohanty, Reference Mohanty1989; Zambrana, Reference Zambrana2018)? Overt discrimination may be in play, but more likely in play is systemic discrimination that can result in unfair experiential burdens placed on racialized faculty members—racialized women faculty members, in particular—all of which are well documented (see, for example, Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2012; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Dhamoon and Moy2014; Hirshfield and Joseph, Reference Hirshfield and Joseph2012; James, Reference James, Chapman-Neyaho, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017; Mahtani, Reference Mahtani2004; Monforti, Reference Monforti, Gutierrez, Muhs, Niemann, González and Harris2012; Padilla, Reference Padilla1994; Settles et al., Reference Settles, Buchanan and Dotson2019; Smith, Reference Smith, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017b; Turner, Reference Turner and Caroline Sotello Viernes2002).

The exclusion of racialized and minoritized individuals from university governance positions (and beyond) has implications for the perpetuation of social constructions of competency (Harris and Gonzáles, Reference Harris, González, Gutierrez, Muhs, Niemann, González and Harris2012; see also Muhs et al., Reference Muhs, Niemann, González and Harris2012). As Angela P. Harris and Carmen G. Gonzáles write, those who differ from the “distinctly white, heterosexual, and middle- and upper-middle-class” norm entrenched in the academy “find themselves, to a greater or lesser degree, ‘presumed incompetent’ by students, colleagues, and administrators” (Reference Harris, González, Gutierrez, Muhs, Niemann, González and Harris2012: 3). Insofar as racialized people continue to be underrepresented in the senior ranks of university governance, these very structures serve in perpetuating this discriminatory stereotype. Racialized barriers are also a problem for the generation and legitimation of knowledge. As many scholars have pointed out, racialized faculty members tend to engage in research that is critical and transformative of practices and institutions that perpetuate exclusion, marginalization and other forms of oppression (see, for example, Bellas and Toutkoushian, Reference Bellas and Toutkoushian1999; Henry and Tator, Reference Henry and Tator2012; James, Reference James, Chapman-Neyaho, Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017; Nakanishi, Reference Nakanishi1993). The exclusion of these perspectives can result in the development and dissemination of only particular kinds of knowledge and only particular types of policy, both of which can serve in upholding discriminatory practices. All of this is likely to result in less than optimal collective deliberation and decision making and ultimately less than optimal policy (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1999; Stewart and Valian, Reference Stewart and Valian2018; Young, Reference Young2002). Central and senior academic administrators are thought leaders, with enormous power over the generation and legitimation of knowledge, and the effects of their decisions have ramifications for virtually every policy area.

Another important lesson from our study is that representation can take us only so far. Our findings with respect to Indigenous people in university administrative positions reveal important limitations. “Counting” Indigenous people drives home one of the most obvious limitations of representational studies: such studies do not get at the long-standing and ongoing violence of colonialism. Representation within these ranks is an important step, but it is likely not sufficient for a transformation of institutions toward reconciliation and, ultimately, decolonialization. What we may be observing in our data is, in the words of Adam Gaudry and Danielle Lorenz, “Indigenous inclusion.” Indigenous inclusion may be a step toward “reconciliation indigenization” and “decolonial indigenization,” but of the three visions, it is the least transformative of efforts to Indigenize universities (Gaudry and Lorenz, Reference Gaudry and Lorenz2018). Much more is needed to address the colonialism perpetuated by universities and “to fundamentally reorient knowledge production based on balancing power relations between Indigenous peoples and Canadians, transforming the academy into something dynamic and new” (219). We can see this limitation with respect to gender queer people as well. Much more than representation needs to transpire in order to stop the violence against non-binary, genderfluid and trans individuals, within university communities and beyond.

Ultimately, we emphasize that our findings are not simply a problem of representation but one of power—power over who is included in, or excluded from, leadership opportunities; over the ideas, interests and perspectives articulated in the creation and legitimation of knowledge; over the social meanings of competency, ability and suitability to govern; and over the extent to which various forms of oppression can meaningfully be addressed. Our study raises important concerns about the politics of who lifts whom into the echelons of academic decision making, which in turn has implications for justice, knowledge and power.

Acknowledgments

This article would not have been possible without the research assistance of Chris Atchison, Kayla Phillips and Sanjana Ramesh. We are indebted to Chris, who worked closely with us to develop and hone our methodology. Kayla and Sanjana exercised enormous care and patience collecting, coding, recoding, checking and rechecking our data. We are also very grateful to Malinda S. Smith, Howard Ramos, Ninan Abraham, Steve Dodge and Marjorie Cohen, as well as the journal's anonymous reviewers, for their thoughtful comments and contributions—all of which have bolstered this article. We take responsibility for any lingering weaknesses.