Introduction

Rates of relapse are high among individuals with psychotic disorders. It is estimated that only 28% of people who suffer from a first episode of psychosis (FEP) will never re-experience another episode in their lifetime (Alvarez-Jimenez et al., Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Priede, Hetrick, Bendall, Killackey, Parker and Gleeson2012). Relapse is associated with an increased financial burden: it has been estimated that direct healthcare costs (encompassing both inpatient and outpatient care) are four times greater for those who relapse compared to those who do not over a 6-month period (Almond, Knapp, Francois, Toumi, & Brugha, Reference Almond, Knapp, Francois, Toumi and Brugha2004), with one study estimating these costs to be even higher (Ascher-Svanum et al., Reference Ascher-Svanum, Zhu, Faries, Salkever, Slade, Peng and Conley2010). Coupled with this financial strain, relapse is associated with poorer quality of life (Bobes, Garcia-Portilla, Bascaran, Saiz, & Bousoño, Reference Bobes, Garcia-Portilla, Bascaran, Saiz and Bousoño2007), poorer social and occupational functioning (Mattsson, Topor, Cullberg, & Forsell, Reference Mattsson, Topor, Cullberg and Forsell2008), more severe clinical symptoms (Wiersma, Nienhuis, Slooff, & Giel, Reference Wiersma, Nienhuis, Slooff and Giel1998) and emotional burden placed on patients and their families (Brady & McCain, Reference Brady and McCain2005). Hence, gaining a better understanding of factors that influence relapse in psychosis is of critical importance to clinical services, patients and their families.

The association between life events and psychosis onset is well-established. A previous systematic review and meta-analysis of 26 studies reported that individuals experiencing life events are three times more likely to develop psychosis (Beards et al., Reference Beards, Gayer-Anderson, Borges, Dewey, Fisher and Morgan2013). In contrast, there has been no attempt to examine the role of recent stressful life events in psychotic relapse by means of a robust systematic review. This area of research is of clinical importance because we cannot assume that factors associated with illness onset are necessarily associated with subsequent relapse. For example, whilst meta-analyses show that childhood trauma confers increased risk for psychosis (Varese et al., Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster, Viechtbauer and Bentall2012), a systematic review found only two of seven studies reported a positive association between childhood trauma and risk of relapse of a pre-existing psychotic disorder during adulthood (Petros et al., Reference Petros, Foglia, Klamerus, Beards, Murray and Bhattacharyya2016).

Whilst early studies examining life events and psychotic relapse provide evidence to suggest that stressful life events occurring after the onset of psychosis confer poorer prognosis (Castine, Meadorwoodruff, & Dalack, Reference Castine, Meadorwoodruff and Dalack1998) and greater risk of relapse (Birley & Brown, Reference Birley and Brown1970), evidence remains equivocal, with some studies showing that life events are not significantly associated with psychotic relapse (Dols et al., Reference Dols, Korten, Comijs, Schouws, van Dijk, Klumpers and Stek2018; McPherson, Herbison, & Romans, Reference McPherson, Herbison and Romans1993). A robust review is needed to determine the consistency of findings across studies as such efforts may ultimately inform treatment approaches. We therefore sought to address this gap in current understanding by summarizing available research investigating the influence of stressful life events experienced after the onset of psychotic disorders (or bipolar disorder if the diagnosis included psychotic symptoms rather than solely affective symptoms) on relapse. We aimed to investigate whether a consistent pattern of evidence exists that suggests that life events occurring after the onset of psychotic disorders have an adverse impact on psychotic relapse, and we aimed to conduct a robust appraisal of the extant literature by assessing study quality and risk of bias.

Methods

Adult stressful life events were defined as events occurring after the onset of psychosis, but before the occurrence of a relapse of psychosis, that were subjectively defined as ‘stressful’. This included, but was not limited to: family problems, relationship difficulties, job worries, money problems and personal injury (Holmes & Rahe, Reference Holmes and Rahe1967). The Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines for a systematic review of observational studies were followed in preparing this report (Stroup, Reference Stroup2000). The study protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42018100396).

Search strategy

A systematic search strategy was employed following the methods recommended by the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins & Green, Reference Higgins and Green2008). Relevant studies were identified by searching PsycINFO, Medline and EMBASE from inception to 08/01/2020. Titles and abstracts were searched for the presence of search terms. Multiple search terms were used to describe relapse, the study population and adult stressful life events. The search terms used were as follows: (outcome or hospital* or relapse or readmission) and (bipolar or psychot* or psychos* or schizophren* or schizoaff*) and (life event* or adult trauma* or social advers* or adult advers*). These search terms for adult stressful life events were used after using ‘stress’ as a search term yielded too many irrelevant results. Reference lists of included articles were also hand searched.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two researchers (NM and RM) independently assessed articles based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, with a senior researcher (AEC) consulted when disagreements arose. Studies were considered eligible for inclusion if they satisfied the following inclusion criteria: (1) study participants had a pre-existing psychotic disorder (i.e. psychosis, schizophrenia, schizoaffective or bipolar disorder if the latter included psychotic symptoms rather than solely affective symptoms); (2) adult stressful life events occurred after psychosis onset and prior to psychotic relapse; and (3) relapse was defined as either readmission to hospital, a return of psychotic symptoms or both. All study designs were eligible for inclusion. There were no restrictions regarding participant stage of illness; studies examining relapses after the first psychotic episode and studies examining remission following previous relapse episodes were included.

Studies were excluded if: (1) the stressful life event occurred either during childhood or before the onset of psychosis; (2) it could not be established when the stressful life event occurred or studies reporting stressful events in one's lifetime rather than specifically after psychosis onset; (3) the study did not carry out a quantitative analysis or explicitly measure the relationship between life events and relapse; or (4) the study was published before 1970 [the first studies explicitly looking at life events and psychotic relapse commenced with the notable Birley and Brown paper in 1970 (Birley & Brown, Reference Birley and Brown1970)]. Conference abstracts and non-English language articles were excluded.

Quality assessment

Studies were assessed for quality using assessment criteria set by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP, 2003), modified to include items of relevance to the present review (Petros et al., Reference Petros, Foglia, Klamerus, Beards, Murray and Bhattacharyya2016). We included an additional category pertaining to the quality of the statistical analysis. Each study was assessed on seven main areas: selection bias, quality of measurement of life events, quality of measurement of psychosis, quality of measurement of relapse, adjustment for confounding variables, data collection methods and statistical analysis. The maximum score that could be awarded was 18. Quality scores were independently generated by two researchers (NM and RM).

Data extraction process and data analysis

From each study, we extracted: study type, participant information, diagnosis, life event measurement, relapse measurement, statistical test used and main findings (statistical results and narrative synthesis). We then examined whether the pattern of results varied across study design, patient diagnosis, relapse measurement, life event measurement and analysis approach (adjustment for confounders) to investigate the extent to which these factors influenced the pattern of results. We also noted whether studies made a distinction between independent life events (events occurring out of a person's control) and dependent life events (events attributable to a person's behaviour or illness) and whether the type of life event had any impact on the occurrence of relapse.

An estimation of the pooled effect size was not carried out due to the heterogeneity in study design, measurement of life events and relapse, and analytic procedures employed. For instance, some studies defined relapse in categorical terms (relapse v. no relapse) whilst others used a continuous variable (number of relapse events). Moreover, the method of analysis varied between studies (regressions, t tests, χ2 and correlations were carried out) and there were differences in adjustment for potential confounders.

Results

Study characteristics

The initial search identified 3039 articles published between 1970 and January 2020. After removing duplicates, 1958 articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 47 were read in full. Twenty-three articles satisfied study eligibility criteria (see Fig. 1). A list of articles excluded after full-text review and reasons is provided in Appendix 1.

Fig. 1. Flow diagram.

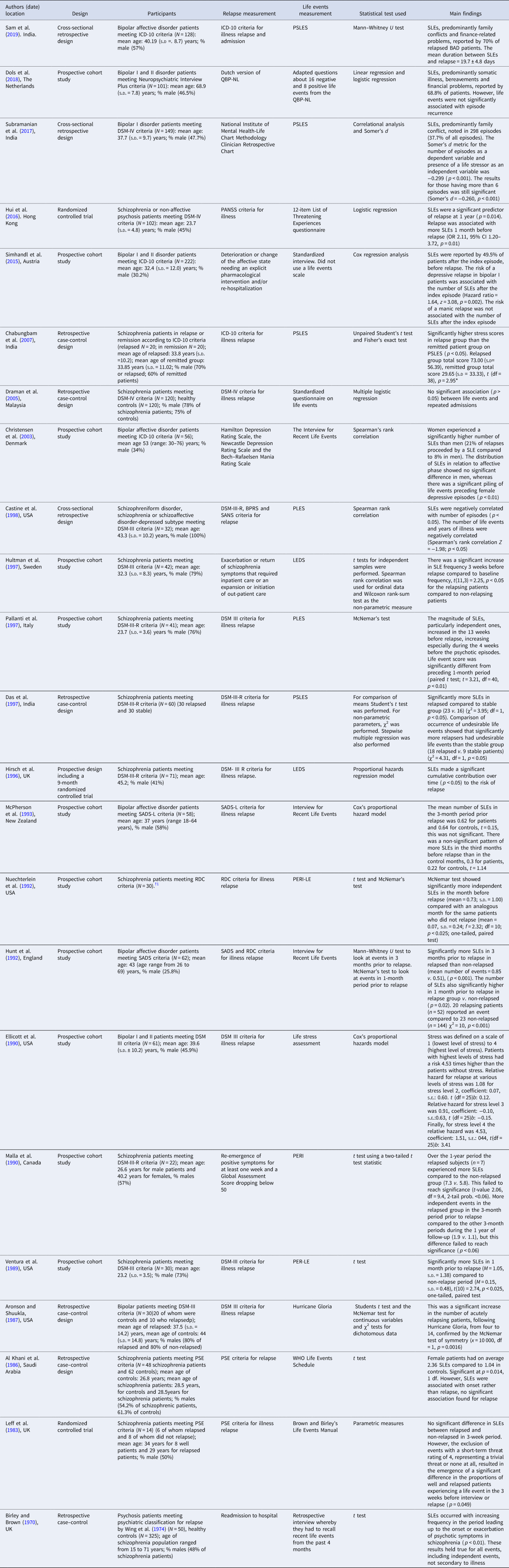

Data from the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Of the 23 eligible studies, all studies except one used interviews to obtain information about exposure to past life events, the remaining study compared the occurrence of relapse between patients who were affected by a hurricane (the adult stressful life event exposure) to those not affected by a hurricane (Aronson & Shukla, Reference Aronson and Shukla1987). Fourteen studies recruited subjects who had a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or schizophreniform disorder, and nine studies included individuals with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder.

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review and main study findings

† The notes appear after the main text.

1 As these data are part of a wider trial we do not have the specific demographics for these 30 patients but rather the 106 schizophrenic patients taking part in overall trial, mean age: 23.3 years; % male (82%).

SLE, stressful life events; PSLES, Presumptive Stressful Life Events Scale; QBP-NL, Questionnaire for Bipolar Disorder; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PLES, Paykel Life Events Schedule; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; LEDS, Life Event and Difficulty Schedule; SADS, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, lifetime version (SADS-L); PERI-LE, Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview for Life Events; PSE, Present State Examination; s.d., standard deviation; s.e., standard error.

The 23 studies included 2046 participants in total, 1539 (75%) of whom had psychosis or were in remission, 507 participants were healthy controls. Of the 1539 participants with a psychotic disorder, 672 (44%) were diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective psychosis and 867 (56%) were diagnosed with either bipolar I disorder or bipolar II disorder. Of studies reporting age and gender, the mean age was 46 years and 51% were male.

Main findings

Results from included studies are summarized in Table 1. Eighteen studies (n = 1513) reported a significant association between stressful life events and subsequent relapse of psychosis (Aronson & Shukla, Reference Aronson and Shukla1987; Birley & Brown, Reference Birley and Brown1970; Castine et al., Reference Castine, Meadorwoodruff and Dalack1998; Chabungbam, Avasthi, & Sharan, Reference Chabungbam, Avasthi and Sharan2007; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Gjerris, Larsen, Bendtsen, Larsen, Rolff and Schaumburg2003; Das, Kulhara, & Verma, Reference Das, Kulhara and Verma1997; Ellicott, Hammen, Gitlin, Brown, & Jamison, Reference Ellicott, Hammen, Gitlin, Brown and Jamison1990; Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Bowen, Emami, Cramer, Jolley, Haw and Dickinson1996; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Li, Li, Lee, Chang, Chan and Chen2016; Hultman, Wieselgren, & Öhman, Reference Hultman, Wieselgren and Öhman1997; Hunt, Bruce-Jones, & Silverstone, Reference Hunt, Bruce-Jones and Silverstone1992; Leff, Kuipers, Berkowitz, Vaughn, & Sturgeon, Reference Leff, Kuipers, Berkowitz, Vaughn and Sturgeon1983; Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Dawson, Gitlin, Ventura, Goldstein, Snyder and Mintz1992; Pallanti, Quercioli, & Pazzagli, Reference Pallanti, Quercioli and Pazzagli1997; Sam, Nisha, & Varghese, Reference Sam, Nisha and Varghese2019; Simhandl, Radua, König, & Amann, Reference Simhandl, Radua, König and Amann2015; Subramanian, Sarkar, Kattimani, Philip Rajkumar, & Penchilaiya, Reference Subramanian, Sarkar, Kattimani, Philip Rajkumar and Penchilaiya2017; Ventura, Nuechterlein, Lukoff, & Hardesty, Reference Ventura, Nuechterlein, Lukoff and Hardesty1989), whereas five studies (n = 531) found a non-significant association between stressful life events and subsequent relapse of psychosis (Al Khani, Bebbington, Watson, & House, Reference Al Khani, Bebbington, Watson and House1986; Dols et al., Reference Dols, Korten, Comijs, Schouws, van Dijk, Klumpers and Stek2018; Draman et al., Reference Draman, Ismail, Merchant, Yusof, Husin and Singh2005; Malla, Cortese, Shaw, & Ginsberg, Reference Malla, Cortese, Shaw and Ginsberg1990; McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Herbison and Romans1993).

Measurement of life events

Of the 22 studies that employed checklists to assess life event exposure, the most commonly employed was the Paykel's Interview for Recent Life Events (Paykel, Reference Paykel1997) which was included in six studies. Five studies used the Presumptive Stressful Life Events Scale or adapted versions of the scale [PSLES: (Singh, Kaur, & Kaur, Reference Singh, Kaur and Kaur1984)], three studies used the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview [PERI: life-event schedule (Dohrenwend, Krasnoff, Askenasy, & Dohrenwend, Reference Dohrenwend, Krasnoff, Askenasy and Dohrenwend1978)], two studies used the Life Event and Difficulty Schedule [LEDS: (Brown, Reference Brown, Brown and Harris1989)], one study used the World Health Organization Life Events Scale (WHO, 1973), while the remaining six studies used standardized interviews and questionnaires, list of threatening experiences questionnaires, life stress assessments and life event manuals (Birley & Brown, Reference Birley and Brown1970; Draman et al., Reference Draman, Ismail, Merchant, Yusof, Husin and Singh2005; Ellicott et al., Reference Ellicott, Hammen, Gitlin, Brown and Jamison1990; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Li, Li, Lee, Chang, Chan and Chen2016; Leff et al., Reference Leff, Kuipers, Berkowitz, Vaughn and Sturgeon1983; Simhandl et al., Reference Simhandl, Radua, König and Amann2015).

Of the different life events scales used, the number of different life events assessed across these measures ranged from a single event (hurricane) (Aronson & Shukla, Reference Aronson and Shukla1987) to 102 different events (Dohrenwend et al., Reference Dohrenwend, Krasnoff, Askenasy and Dohrenwend1978). Items commonly assessed across multiple measures included, but were not limited to, death of a loved one, financial difficulties, marital problems, somatic illness and illness within the family. Further, the measurement of certain life events varied between studies. For example, the criteria relating to the life event 'bereavement' varied between studies. In some instances the category 'bereavement' included solely bereavement of a first-degree relative (Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Bruce-Jones and Silverstone1992) whereas in other instances the category 'bereavement' included the death of any close family member (Subramanian et al., Reference Subramanian, Sarkar, Kattimani, Philip Rajkumar and Penchilaiya2017). The latter question is broader so perhaps more participants could identify.

Thirteen studies explicitly made a distinction between the dependent and independent life events, with 10 of these studies finding a significant association between independent life events and psychotic relapse (Aronson & Shukla, Reference Aronson and Shukla1987; Birley & Brown, Reference Birley and Brown1970; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Gjerris, Larsen, Bendtsen, Larsen, Rolff and Schaumburg2003; Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Bowen, Emami, Cramer, Jolley, Haw and Dickinson1996; Hultman et al., Reference Hultman, Wieselgren and Öhman1997; Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Bruce-Jones and Silverstone1992; Leff et al., Reference Leff, Kuipers, Berkowitz, Vaughn and Sturgeon1983; Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Dawson, Gitlin, Ventura, Goldstein, Snyder and Mintz1992; Pallanti et al., Reference Pallanti, Quercioli and Pazzagli1997; Ventura et al., Reference Ventura, Nuechterlein, Lukoff and Hardesty1989), indicating that the observed association is not restricted to life events occurring in the context of illness.

Relapse and psychosis measurements

Relapse measurement varied across studies. One study defined relapse as readmission or a return of symptoms (Simhandl et al., Reference Simhandl, Radua, König and Amann2015); three studies defined relapse as a return of symptoms requiring hospitalization (Birley & Brown, Reference Birley and Brown1970; Hultman et al., Reference Hultman, Wieselgren and Öhman1997; Sam et al., Reference Sam, Nisha and Varghese2019); and the remaining 20 studies defined relapse as a return of symptoms. Various scales were used to measure a return of psychotic symptoms including: the DSM III criteria (Kendell, Reference Kendell1980); the DSM IV criteria (Kutchins & Kirk, Reference Kutchins and Kirk1995); the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (Endicott & Spitzer, Reference Endicott and Spitzer1978); the Global Assessment Scores (Kutchins & Kirk, Reference Kutchins and Kirk1995); the Presumptive Stressful Events Scale (Singh, Kaur, & Kaur, Reference Singh, Kaur and Kaur1984); ICD-10 criteria (WHO, 2011); the National Institute of Mental Health-Life Chart Methodology Clinician Retrospective Chart (Roy-Byrne, Post, Uhde, Porcu, & Davis, Reference Roy-Byrne, Post, Uhde, Porcu and Davis1985); the Neuropsychiatric Interview Plus (MINI) (Dols et al., Reference Dols, Korten, Comijs, Schouws, van Dijk, Klumpers and Stek2018); the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (Overall & Gorham, Reference Overall and Gorham1962); the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (Andreasen, Reference Andreasen1989), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1980), the Newcastle Depression Rating Scale (Carney, Roth, & Garside, Reference Carney, Roth and Garside1965), the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller and Dunbar1998); and the Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Rating Scale (Bech, Bolwig, Kramp, & Rafaelsen, Reference Bech, Bolwig, Kramp and Rafaelsen1979).

Of the 19 studies defining relapse as a return of psychotic symptoms, 14 studies (74%) found a significant association between stressful life events and relapse (Aronson & Shukla, Reference Aronson and Shukla1987; Castine et al., Reference Castine, Meadorwoodruff and Dalack1998; Chabungbam et al., Reference Chabungbam, Avasthi and Sharan2007; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Gjerris, Larsen, Bendtsen, Larsen, Rolff and Schaumburg2003; Das et al., Reference Das, Kulhara and Verma1997; Ellicott et al., Reference Ellicott, Hammen, Gitlin, Brown and Jamison1990; Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Bowen, Emami, Cramer, Jolley, Haw and Dickinson1996; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Li, Li, Lee, Chang, Chan and Chen2016; Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Bruce-Jones and Silverstone1992; Leff et al., Reference Leff, Kuipers, Berkowitz, Vaughn and Sturgeon1983; Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Dawson, Gitlin, Ventura, Goldstein, Snyder and Mintz1992; Pallanti et al., Reference Pallanti, Quercioli and Pazzagli1997; Subramanian et al., Reference Subramanian, Sarkar, Kattimani, Philip Rajkumar and Penchilaiya2017; Ventura et al., Reference Ventura, Nuechterlein, Lukoff and Hardesty1989), whereas five studies did not find a signficant association (Al Khani, Bebbington, Watson, & House, Reference Al Khani, Bebbington, Watson and House1986; Dols et al. Reference Dols, Korten, Comijs, Schouws, van Dijk, Klumpers and Stek2018; Draman at al., Reference Draman, Ismail, Merchant, Yusof, Husin and Singh2005; Malla, Cortese, Shaw, & Ginsberg, Reference Malla, Cortese, Shaw and Ginsberg1990; McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Herbison and Romans1993). The one study defining relapse as readmission or a return of symptoms found a positive association between stressful life events and relapse (Simhandl et al., Reference Simhandl, Radua, König and Amann2015). The three studies defining relapse as a return of symptoms requiring hospitalization all found a significant association between stressful life events and relapse (Birley & Brown, Reference Birley and Brown1970; Hultman et al., Reference Hultman, Wieselgren and Öhman1997; Sam et al., Reference Sam, Nisha and Varghese2019). Whilst this tentatively suggests that non-significant associations were only found in studies that defined relapse on the basis of symptoms only (as opposed to hospitalization), the smaller number of studies in the latter group prevents us from drawing this conclusion.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis varied between studies. Fourteen studies included participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, psychosis or schizoaffective psychosis, of these, 11 studies (79%) found a significant association between stressful life events and relapse (Birley & Brown, Reference Birley and Brown1970; Castine et al., Reference Castine, Meadorwoodruff and Dalack1998; Chabungbam et al., Reference Chabungbam, Avasthi and Sharan2007; Das et al., Reference Das, Kulhara and Verma1997; Dols et al., Reference Dols, Korten, Comijs, Schouws, van Dijk, Klumpers and Stek2018; Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Bowen, Emami, Cramer, Jolley, Haw and Dickinson1996; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Li, Li, Lee, Chang, Chan and Chen2016; Hultman et al., Reference Hultman, Wieselgren and Öhman1997; Leff et al., Reference Leff, Kuipers, Berkowitz, Vaughn and Sturgeon1983; Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Dawson, Gitlin, Ventura, Goldstein, Snyder and Mintz1992; Pallanti et al., Reference Pallanti, Quercioli and Pazzagli1997; Ventura et al., Reference Ventura, Nuechterlein, Lukoff and Hardesty1989). Eleven studies included participants with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder, of these, nine found a significant association between stressful life events and relapse (Aronson & Shukla, Reference Aronson and Shukla1987; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Gjerris, Larsen, Bendtsen, Larsen, Rolff and Schaumburg2003; Ellicott et al., Reference Ellicott, Hammen, Gitlin, Brown and Jamison1990; Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Bruce-Jones and Silverstone1992; Sam et al., Reference Sam, Nisha and Varghese2019; Simhandl et al., Reference Simhandl, Radua, König and Amann2015; Subramanian et al., Reference Subramanian, Sarkar, Kattimani, Philip Rajkumar and Penchilaiya2017). It does not therefore appear that diagnosis had any impact on whether the association between life events and relapse was significant.

Study design

Fourteen studies used a prospective design, of which 11 (79%) found a significant association between life events and relapse (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Gjerris, Larsen, Bendtsen, Larsen, Rolff and Schaumburg2003; Dols et al., Reference Dols, Korten, Comijs, Schouws, van Dijk, Klumpers and Stek2018; Ellicott et al., Reference Ellicott, Hammen, Gitlin, Brown and Jamison1990; Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Bowen, Emami, Cramer, Jolley, Haw and Dickinson1996; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Li, Li, Lee, Chang, Chan and Chen2016; Hultman et al., Reference Hultman, Wieselgren and Öhman1997; Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Bruce-Jones and Silverstone1992; Leff et al., Reference Leff, Kuipers, Berkowitz, Vaughn and Sturgeon1983; Malla et al., Reference Malla, Cortese, Shaw and Ginsberg1990; McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Herbison and Romans1993; Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Dawson, Gitlin, Ventura, Goldstein, Snyder and Mintz1992; Pallanti et al., Reference Pallanti, Quercioli and Pazzagli1997; Simhandl et al., Reference Simhandl, Radua, König and Amann2015; Ventura et al., Reference Ventura, Nuechterlein, Lukoff and Hardesty1989). The follow-up period for these studies ranged from 9 months to 6 years (mean 2.5 years). Three studies used a cross-sectional design, all of these studies (100%) found a significant association between life events and relapse (Castine et al., Reference Castine, Meadorwoodruff and Dalack1998; Sam et al., Reference Sam, Nisha and Varghese2019; Subramanian et al., Reference Subramanian, Sarkar, Kattimani, Philip Rajkumar and Penchilaiya2017). The remaining six studies used a retrospective design, four of these studies (67%) found a significant association between life events and relapse (Al Khani et al., Reference Al Khani, Bebbington, Watson and House1986; Aronson & Shukla, Reference Aronson and Shukla1987; Birley & Brown, Reference Birley and Brown1970; Chabungbam et al., Reference Chabungbam, Avasthi and Sharan2007; Das et al., Reference Das, Kulhara and Verma1997; Draman et al., Reference Draman, Ismail, Merchant, Yusof, Husin and Singh2005). Overall, it appears that there is no relationship between study design and whether an association between life events and relapse was found.

Time frame for stressful life events and relapse

Of those studies reporting a positive association between adult stressful life events and psychotic relapse, nine studies (39%) reported that life events occurring in the month before relapse had a significant association with relapse (Aronson & Shukla, Reference Aronson and Shukla1987; Castine et al., Reference Castine, Meadorwoodruff and Dalack1998; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Li, Li, Lee, Chang, Chan and Chen2016; Hultman et al., Reference Hultman, Wieselgren and Öhman1997; Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Bruce-Jones and Silverstone1992; Leff et al., Reference Leff, Kuipers, Berkowitz, Vaughn and Sturgeon1983; Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Dawson, Gitlin, Ventura, Goldstein, Snyder and Mintz1992; Sam et al., Reference Sam, Nisha and Varghese2019; Ventura et al., Reference Ventura, Nuechterlein, Lukoff and Hardesty1989). One study (4%) reported that life events occurring in the 3 months prior to relapse had a significant association with relapse (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Gjerris, Larsen, Bendtsen, Larsen, Rolff and Schaumburg2003). The remaining 13 studies (57%) neitherstated when most life events occurred nor assessed life events in relation to time frames over the course of illness or around outcome events of interest. Hence, it is difficult to draw conclusions regarding windows of vulnerability to relapse following exposure to life events or whether time frame may indeed moderate the association between life events and relapse.

Confounders

It is certainly worth noting that all five of the studies which did not find a significant association between life events and relapse did not adjust for confounders. This may show that perhaps other factors are more important in causing relapse and only when these are adjusted for can we see the true association between life events and psychotic relapse (Al Khani et al., Reference Al Khani, Bebbington, Watson and House1986; Dols et al., Reference Dols, Korten, Comijs, Schouws, van Dijk, Klumpers and Stek2018; Draman et al., Reference Draman, Ismail, Merchant, Yusof, Husin and Singh2005; Malla et al., Reference Malla, Cortese, Shaw and Ginsberg1990; McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Herbison and Romans1993).

Quality score

Quality scores are presented in Table 2. The mean quality score across all studies was 11.74 (range: 5–18), indicating modest quality. Eighty-three per cent of studies used a standardized life events checklist delivered via semi-structured interview and 87% of studies measured relapse using objective tools. In general, high scores were awarded for the measurement of psychosis and the measurement of relapse. In contrast, few studies were awarded points for adjustment for confounding variable(s) or conducting in-depth statistical analyses. Only five studies adjusted for basic demographics and/or potential risk factors, such as drug and alcohol use, social support and medication adherence (Al Khani, Bebbington, Watson, & House, Reference Al Khani, Bebbington, Watson and House1986; Chabungbam et al., Reference Chabungbam, Avasthi and Sharan2007; Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Bowen, Emami, Cramer, Jolley, Haw and Dickinson1996; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Li, Li, Lee, Chang, Chan and Chen2016; Simhandl et al., Reference Simhandl, Radua, König and Amann2015).

Table 2. Study quality rating

There did not appear to be an effect of study quality score on the occurrence of relapse. The mean quality score for studies finding a non-significant association between life events and relapse scores (mean quality score: 10.6, range: 9–13) was broadly similar to the mean quality score for studies reporting a significant association between life events and relapse (mean quality score: 11.8, range: 5–18) and there was substantial overlap in the ranges of these scores.

A median split based on quality ratings found that 67% of studies below the median quality score found a significant association between life events and relapse whereas 86% of studies above the median quality score found a significant association between life events and relapse [non-significant difference, χ2=(1)1.168, p = 0.280].

Discussion

Findings and interpretation

The aim of this systematic review was to qualitatively summarize currently available evidence regarding the relationship between adult stressful life events and relapse of psychosis in those with an established psychotic disorder. We found that 18 of the 23 included studies provided evidence of an association between adult stressful life events (occurring after illness onset) and subsequent relapse. Moreover, there were no discernible differences between studies that found a significant association between life events and relapse and those that did not in terms of relapse measurement, diagnosis, study design, quality score or whether the life event was an independent or dependent life event. However, as the majority of studies did not examine the time frame between adult stressful life events and psychotic relapse, we cannot draw conclusions regarding the proximity of life events to relapse occurrence and recommend that future studies investigate whether life events more frequently occur close to relapse.

The included studies measured multiple types of adult stressful life events including family conflict, bereavement, work conflict, education, financial issues, social problems, marital conflict, marriage, moving house, illness and injury, and natural disasters. Of the studies reporting a significant association between stressful life events and relapse, family conflict (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Gjerris, Larsen, Bendtsen, Larsen, Rolff and Schaumburg2003; Sam et al., Reference Sam, Nisha and Varghese2019; Subramanian et al., Reference Subramanian, Sarkar, Kattimani, Philip Rajkumar and Penchilaiya2017), financial loss (Sam et al., Reference Sam, Nisha and Varghese2019), unemployment (Hultman et al., Reference Hultman, Wieselgren and Öhman1997; Sam et al., Reference Sam, Nisha and Varghese2019), somatic illness (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Gjerris, Larsen, Bendtsen, Larsen, Rolff and Schaumburg2003; Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Bruce-Jones and Silverstone1992) and illness within the family (Hultman et al., Reference Hultman, Wieselgren and Öhman1997; Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Bruce-Jones and Silverstone1992; Sam et al., Reference Sam, Nisha and Varghese2019) were rated as the most common stressful life events occurring prior to relapse. It is important for both patients and their care teams to be mindful of these common stressful life events so that help can be given to mitigate their effects soon after they occur. We cannot, however, say that these most commonly reported events are necessarily the most important, particularly as many studies used structured checklists which only capture specific events (i.e. there may be other events experienced by patients that were not measured but were nonetheless important for relapse). Future work could investigate whether certain life events are more important in causing psychotic relapse than others. It may be that this varies considerably across patients such that one event is particularly salient to some patients but not others.

Of the included studies, 61% used a prospective cohort (longitudinal) design, the mean quality score was 11.74 out of a possible 18, and only 22% of studies adjusted for confounders. An important conclusion drawn from the present review is the need for studies employing better methodological approaches, particularly longitudinal designs, as well as consideration of potential confounders that may provide more robust evidence and therefore meaningfully inform practice and policy.

Despite the modest quality of included studies, our findings suggest that adult stressful life events, occurring after illness onset, may have a triggering role in increasing the risk of psychotic relapse. However, it is important to note that all studies included in this review were observational and are therefore unable to assess whether the association is causal in nature. Nevertheless, the studies reviewed (particularly prospective studies measuring life events prior to relapse onset) indicate a temporal relationship between exposure to stressful life events and subsequent relapse amongst psychosis subjects.

It has long been assumed that stressful life events are relevant to the course of psychosis, and stress has been considered as a precipitating factor in aetiological theories of schizophrenia (Howes & Murray, Reference Howes and Murray2014); moreover, plausible mechanisms have been proposed to explain this relationship. For example, stressful life events may increase the risk of psychotic relapse via activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. The neural diathesis stress model proposed by Walker and Diforio (Reference Walker and Diforio1997) and updated by Pruessner, Cullen, Aas, and Walker (Reference Pruessner, Cullen, Aas and Walker2017) proposes that stress exposure may trigger or exacerbate psychotic symptoms by augmenting dopamine activity, particularly in the subcortical region of the limbic circuitry. The updated model also suggests that the HPA axis interacts with the immuno-inflammatory system (Pruessner et al., Reference Pruessner, Cullen, Aas and Walker2017). In support of the model, patients with psychosis and those at increased risk for the disorder (due to a family history of illness or clinical features) have been found to show HPA axis abnormalities, including elevated basal and diurnal cortisol, a blunted cortisol awakening response and pituitary volume abnormalities (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Kraeuter, Romanik, Malouf, Amminger and Sarnyai2016; Borges, Gayer-Anderson, & Mondelli, Reference Borges, Gayer-Anderson and Mondelli2013; Chaumette et al., Reference Chaumette, Kebir, Mam-Lam-Fook, Morvan, Bourgin, Godsil and Krebs2016; Cullen et al., Reference Cullen, Zunszain, Dickson, Roberts, Fisher, Pariante and Laurens2014; Day et al., Reference Day, Valmaggia, Mondelli, Papadopoulos, Papadopoulos, Pariante and McGuire2014; Girshkin, Matheson, Shepherd, & Green, Reference Girshkin, Matheson, Shepherd and Green2014; Nordholm et al., Reference Nordholm, Krogh, Mondelli, Dazzan, Pariante and Nordentoft2013; Saunders, Mondelli, & Cullen, Reference Saunders, Mondelli and Cullen2019). However, a recent meta-analysis of 134 effect sizes from 18 studies (Cullen et al., Reference Cullen, Rai, Vaghani, Mondelli and McGuire2020) found that, in psychosis spectrum groups and healthy controls, psychosocial stressors were only weakly (and not significantly) correlated with cortisol measures. Whilst these findings imply that the HPA abnormalities characterising psychosis spectrum groups are not driven by psychosocial stressors, the authors identified a range of methodological issues that may have obscured the ability to detect significant associations. Thus, further research, accounting for these methodological issues, is needed to determine whether the relationship between life events and relapse might be mediated by the HPA axis.

Implications

The findings from this review suggest that adult stressful life events are associated with psychosis relapse and may increase the risk of psychosis relapse. Future research could investigate novel treatments that mitigate the harm from stressful life events and thus prevent psychosis relapse. For example, newly-developed methods for allowing patients to monitor life events by the use of smartphone apps could be beneficial in targeting relapse. Smartphone apps are emerging as a method to monitor psychosis symptoms as relapse predictors (Eisner et al., Reference Eisner, Bucci, Berry, Emsley, Barrowclough and Drake2019). A future target of these smartphone apps could be the addition of life event monitoring. It may also be wise to educate patients, carers and healthcare professionals about the role of stressful life events and to offer practical and emotional support to patients who have experienced stressful life events.

Limitations

Several limitations of the present systematic review are worth noting. Firstly, in our systematic search, a variety of terms to describe life events were used, however, we excluded the word ‘stress’ as this yielded too many irrelevant results. Relevant articles may subsequently have been excluded. However, reference lists of all relevant studies were hand searched to ensure all pertinent articles were included and to overcome this limitation.

Secondly, there was methodological heterogeneity between the studies which made it difficult to compare and integrate results from studies that were included in this review. Studies used different criteria to measure psychotic relapse and recent life experiences, differed in study design, and recruited participants with different diagnoses (schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, and bipolar disorder). This may have made it difficult to separate the potential confounding effect of illness diagnosis on outcome (Mallett, Hagen-Zanker, Slater, & Duvendack, Reference Mallett, Hagen-Zanker, Slater and Duvendack2012). As stated previously, these differences meant the data could not be combined with a quantitative synthesis.

Thirdly, many studies in the present review did not account for potential confounding variables, future work should ensure confounders are accounted for. Fourthly, many studies used retrospective measures which may make them susceptible to recall bias. This can limit validity, if there is a long gap between the event and recall (Howard, Reference Howard2011). However, this may not have been an issue as only recent adult stressful life events were analysed.

Lastly, we should note that while the included studies may suggest that life events likely have a causal role in subsequent relapse, evidence summarized here is based on observational rather than experimental data and also predominantly from cross-sectional rather than longitudinal studies. Hence, we cannot demonstrate a causal relationship, so an alternative suggestion is that life events and relapse simply co-occur at the same time. However, as the included studies examined life events occurring prior to the psychotic relapse, and longitudinal studies have demonstrated that life events increase the risk of illness onset (Beards et al., Reference Beards, Gayer-Anderson, Borges, Dewey, Fisher and Morgan2013), this lends support to the notion that life events may have a causal role in psychotic relapse.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there may be a link between recent adult stressful life events and relapse of psychosis. These findings may have clinical implications via informing the development of ways to mitigate the harm from stressful life events and thereby reduce the risk of psychotic relapse.

Financial support

AEC was supported by a Sir Henry Wellcome Postdoctoral Fellowship (107395/Z/15/Z) and a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (28336). SB has been supported by an NIHR Clinician Scientist Award (NIHR CS-11-001), and the NIHR Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation grant (16/126/53). The authors acknowledge infrastructure support from the NIHR Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix 1. A list of articles excluded after full-text review, with reasons