Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone is a rare and invariably aggressive tumour with an estimated incidence of one per million per year.Reference Morton, Stell and Derrick1, Reference Kuhel, Hume and Selesnick2 The pathogenesis mainly implicates chronic suppurative otitis media, with 50 per cent of patients reporting a positive history.Reference Moffat, Grey, Ballagh and Hardy3 The management of these tumours remains a challenge in the hands of skull base surgeons, and prognosis has remained poor despite the employment and development of different surgical techniques through the years.Reference Manolidis, Pappas, Von, Jackson and Glasscock4

The objective of this study was to present the management and outcome of patients presenting with temporal bone squamous cell carcinoma to the skull base unit at Guy's Hospital, in the light of conflicting reports regarding the effect of extensive surgery on survival in advanced stage disease.Reference Moffat, Grey, Ballagh and Hardy3, Reference Prasad and Janecka5

Patients and methods

Nineteen patients were initially identified with carcinoma of the temporal bone, who presented to and received treatment at the skull base unit of Guy's Hospital over a period of 20 years. Patients with carcinoma of the cartilaginous part of the external auditory canal and those with non-squamous cell carcinoma lesions were excluded from our study. Seventeen patients were finally included in the study, since two patients were lost to follow up and there were no data on their disease outcomes. One patient presented with bilateral disease. The study included three patients who were initially diagnosed and managed elsewhere and were treated at our unit for recurrent disease.

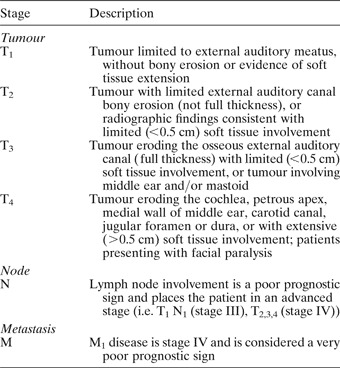

The revised Pittsburgh system was used for disease classification (Table I).Reference Arriaga, Curtin, Takahashi, Hirsch and Kamerer6, Reference Hirsch7

Table I University of Pittsburgh 2002 revised tnm classification system for temporal bone scc

TNM = tumour–node–metastasis; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma

Disease-specific and overall survival analysis, using the Kaplan–Meier test, was performed for the entire cohort as well as for cases with advanced stage tumours. The three recurrent cases were included in the survival analysis, and time-to-event was calculated from the time of original diagnosis of the primary tumour.

Results

Patient's data are summarised in Table II. There were six male and 11 female patients. The mean age at presentation was 63 years, with a range of 39 to 75 years. The median follow-up time of censored cases was 66 months (range 28–132 months).

Table II Patient details

* Facial nerve function was graded according to the House-Brackmann. †Treatment prior to referral; ‡Treatment following recurrence. Yrs = years; chemo = chemotherapy; FU = follow up; mths = months; TNM = tumour–node–metastasis; NR = not recorded; DOD = dead of disease; LTBR = lateral temporal bone resection; AND = alive with no evidence of disease; STP = subtotal petrosectomy; DND = dead with no evidence of disease; RM = radical mastoidectomy; AWD = alive with evidence of disease; CR = chemoradiation; ND = neck dissection

Management of de novo tumours

Twelve cases were managed by surgical resection, followed by adjunctive radiotherapy in 10 cases. Three patients were considered incurable from the outset and given a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. One patient developed local recurrence during his follow up and was offered palliative chemotherapy. A further patient developed neck disease during her follow up, which was successfully managed with neck dissection.

In patients who were treated surgically, the extent of surgical intervention was determined by tumour (T) stage. Tumours staged as T2 were managed by lateral temporal bone resection, which involved the en bloc resection of the external auditory canal, tympanic membrane and ossicles. We were aware pre-operatively of the possibility of an under-staging error, and we would have had a low threshold for performing a superficial parotidectomy in the case of T2 N0 tumours; however, no case required this approach. With the availability of increased imaging power, in the form of computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography, such errors are likely to become less frequent. Tumours staged as T3 and T4 were managed by subtotal petrosectomy. Parotidectomy in the latter cases was performed so as to include the first echelon nodes. The surgical defect was reconstructed with a temporalis muscle flap in all but one patient, who had a latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap. The pinna was not routinely excised, as 1 cm lateral clearance was achieved in all of our cases (cases with carcinoma of the cartilaginous portion of the external auditory meatus or the pinna were not included in our study).

One patient presented with bilateral temporal bone carcinoma. She underwent a subtotal petrosectomy on the left side and a lateral temporal bone resection on the right. The latter site was later fitted with a bone-anchored hearing aid.Reference Bibas, Ward and Gleeson8 Rehabilitation of the paralysed face was approached either by performing a VII–XII cranial nerve anastomosis or by employing fascial slings in a second stage. Interposition grafts are notoriously unreliable for this group of mainly elderly patients.

Management of recurrent tumours

Of the three patients referred to our unit with recurrent disease, two were initially treated with radical mastoidectomy and one with chemoradiation. All were subsequently managed by subtotal petrosectomy. One patient developed a further local recurrence during his follow up and was offered palliative chemotherapy.

Survival analysis

When this study concluded, six patients were dead from their disease, six were alive without evidence of disease, two were alive with evidence of disease and three were dead with no evidence of disease. All three patients with T2 tumours remained alive and free of disease after follow-up times of 62, 89 and 66 months. The disease-specific five-year survival for the entire cohort was 64.17 per cent (mean 89 months, 95 per cent confidence interval (CI) 62–117). Survival remained constant after 24 months. The overall survival for the entire cohort was 47.06 per cent (mean 70 months, 95 per cent CI 43–98). Survival remained constant after 26 months (Figure 1). The disease-specific and overall survival for patients with advanced T3 and T4 tumours was 59 per cent (mean 83 months, 95 per cent CI 53–113) and 40 per cent (mean 62 months, 95 per cent CI 33–91 months), respectively (Figure 2).

Fig. 1 (a) Disease-specific survival and (b) overall 5-year survival, for entire cohort.

Fig. 2 (a) Disease-specific survival and (b) overall 5-year survival, for patients with T3 and T4 tumours.

Discussion

Squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone is a rare but aggressive tumour which usually has a poor prognosis. Survival is related to tumour stage at presentation but is independent of histological grade.Reference Stell9, Reference Arriaga, Hirsch, Kamerer and Myers10 Patients who have positive nodal disease or recurrence inevitably succumb to their disease, often quickly.

Methodological limitations in the literature

Published outcome data are difficult to interpret because there is no universally accepted staging system for temporal bone squamous cell carcinoma, making direct comparison of survival data an almost quichotian task. Although Clarke's modification of Stell's staging proposal has been used in the past, the Pittsburgh classification system is the one most commonly used at present.Reference Arriaga, Curtin, Takahashi, Hirsch and Kamerer6, Reference Hirsch7, Reference Clark, Narula, Morgan and Bradley11 This system is based on pre-operative clinical examination and computed tomography findings, and a good correlation has been shown between disease stage and prognosis, although statistical validation is difficult owing to the small sample sizes reported.Reference Austin, Stewart and Fawzi12, Reference Moody, Hirsch and Myers13 The Pittsburgh system has been recently revised by staging facial nerve involvement as T4.Reference Hirsch7 However, Moffat and Wagstaff, in their series, did not find facial nerve involvement to be a significant prognostic indicator (unpublished data).Reference Moffat and Wagstaff14

Because of the rarity of temporal bone squamous cell carcinoma, most studies have involved small sample sizes and follow-up periods too limited to draw any meaningful conclusion. Another difficulty is the fact that the majority of published series of temporal bone carcinoma consist of mixed caseloads of histologically different tumours. Furthermore, the Pittsburgh classification system is used regardless of tumour histology, despite the fact that it was originally evaluated and proposed for squamous cell carcinoma only.Reference Nyrop and Grontved15

Management issues and survival

Most authors have advocated some form of surgical resection of temporal bone squamous cell carcinoma, with adjuvant radiotherapy for advanced stage disease. The extent and type of surgery has been greatly debated in the literature and ranges from simple resection to complete en bloc removal of the temporal bone, depending on the extent of the tumour.Reference Lewis16–Reference Zhang, Tu, Xu, Tang and Hu20

Different procedures for the management of T1 and T2 tumours have been described, from local resection to subtotal petrosectomy.Reference Golding-Wood, Quiney and Cheesman21, Reference Goodwin and Jesse22 There were no T1 tumours in our series. There were three T2 cases, which were all treated with lateral temporal bone resection. Two of these cases received post-operative radiotherapy as the tumour was large in size. All of these patients remained alive and free of disease for over five years. However, the sample size was too small to make any meaningful inferences. In the only meta-analysis of the treatment of temporal bone carcinomas, Prasad and Janecka showed that the five-year survival for tumours confined to the external auditory meatus was 50 per cent, and there were no differences between patients treated with mastoidectomy, lateral temporal bone resection or subtotal temporal bone resection. Post-operative radiotherapy following lateral temporal bone resection does not appear to improve survival.Reference Prasad and Janecka5

How radical should one be in the surgical treatment of advanced disease? Advocates of total en bloc resection argue that it is the only way to ensure clear margins.Reference Graham, Sataloff, Kemink, Wolf and McGillicuddy23 However, although some resections are considered en bloc, drilling of the mastoid to identify landmarks, and the use of curettes and rongeurs, removes some of the specimen from pathological examination, which throws into doubt the true significance of clear margins. There is also evidence from pathological studies that, in extensive disease, the infiltrative pattern of the tumour is such that radical surgery is futile. Infiltration of the internal auditory meatus and the carotid nerve plexus are consistent findings in T4 tumours.Reference Michaels and Wells24

• The aim of this study was to present the management and survival data of patients with temporal bone squamous cell carcinoma, and to discuss whether extensive surgery improves survival

• Lateral temporal bone resection is adequate treatment for T1 and T2 tumours

• Post-operative radiotherapy should probably be offered for large T2 tumours

• For T3 and T4 tumours, a subtotal petrosectomy with parotidectomy followed by post-operative radiotherapy is adequate treatment, as it offers a similar outcome to more extensive procedures

Along the same line, clinical studies have failed to show that total en bloc resection is superior to less extensive procedures when combined with radiotherapy.Reference Prasad and Janecka5, Reference Arriaga, Hirsch, Kamerer and Myers10, Reference Kinney and Wood18, Reference Zhang, Tu, Xu, Tang and Hu20 In the literature, survival in cases of extension into the middle ear is quoted as being 17–42 per cent,Reference Prasad and Janecka5 possibly reflecting differences in the relative proportion of T3 and T4 tumours. Nakagawa et al. have recently suggested that en bloc radical surgery with pre-operative chemoradiation is effective in improving the estimated survival of patients with advanced stage temporal bone squamous cell carcinoma.Reference Nakagawa, Kumamoto, Natori, Shiratsuchi, Toh and Kakazu25 However, according to their tabulated data, only six of the 25 patients included in their study received pre-operative chemoradiation, and this hardly justifies their initial suggestion. In our series, all tumours with advanced disease were treated with subtotal petrosectomy with parotidectomy and post-operative radiotherapy. In these cases, this achieved a disease-specific and an overall five-year survival of 59 and 40 per cent, respectively, despite the greater number of T4 tumours and the inclusion of recurrent cases. Total en bloc resection is also technically more demanding and is associated with increased morbidity of up to 12.1 per cent.Reference Prasad and Janecka5 Another issue is that cochlear loss due to unnecessarily extensive procedures will not allow for bone-anchored hearing aid rehabilitation, which may be an issue in bilateral disease or severe sensorineural hearing loss in the healthy ear.Reference Bibas, Ward and Gleeson8

The management of local recurrent disease is even more challenging, and there are not many reports in the literature from which to draw any definitive conclusions. All three patients referred to our unit with recurrent disease were offered a subtotal petrosectomy, as it was felt that their initial treatment had been inadequate (chemoradiation in one case and radical mastoidectomy in two cases). One patient died of his disease at 24 months, one remained alive with disease at 58 months and one remained alive with no evidence of disease at 40 months. Of our de novo patients, one developed local recurrence during his follow up and was offered palliative chemotherapy; he died soon afterwards. We believe that a subtotal petrosectomy should be offered to those recurrent cases which received inadequate initial treatment, such as radical mastoidectomy or radiotherapy as a single modality. It seems doubtful that more extensive procedures, such as total temporal bone resection, produce better survival rates. However, Moffat et al., in the only case series in the literature addressing management of advanced recurrent disease, quote a 47 per cent survival rate for cases treated with total petrosectomy, but with considerable morbidity (i.e. lower cranial nerve palsies, 17 per cent; meningitis, 8 per cent; dysphagia, 13 per cent; and visual disturbance, 4 per cent).Reference Moffat, Grey, Ballagh and Hardy3

Conclusions

It is beyond doubt that carcinoma of the temporal bone presents a management challenge. We feel that there is an urgent need for multi-centre studies and a uniform staging system to allow comparison of results among series.

Our study suffered some of the same limitations as most of the previously published series, in that the study population was small; however, our patients had a reasonable follow-up time. Nevertheless, we feel that less heroic surgery combined with radiotherapy would probably give results equal to those of more extensive en bloc procedures, and this view is supported by the current literature.

More specifically, firstly, we are of the opinion that lateral temporal bone resection is adequate treatment for T1 and T2 tumours; post-operative radiotherapy should probably be offered for large T2 tumours. Secondly, we believe that, for T3 and T4 tumours, a subtotal petrosectomy with parotidectomy followed by post-operative radiotherapy is adequate treatment, as this offers a similar outcome to that of more extensive procedures.