Introduction

Every year, more than 1.6 million women worldwide lose their lives to domestic violence, which places a massive burden on national economies costing countries billions of US dollars each year in health care, law enforcement and lost productivity (World Health Organization, 2005). A recent report (World Health Organization, 2013) found that about 30–38% of women across the globe who have been in a relationship have experienced some form of physical and/or sexual violence at the hands of their intimate partner, which in turn exacts a tremendous toll on their physical, mental, sexual and reproductive health. Equally alarming is the fact that being pregnant does not act as a protective buffer against violence, which was found to be particularly high among women from poorer socioeconomic groups living in slums and in rural areas (Peedicayil et al., Reference Peedicayil, Sadowski, Jeyaseelan, Shankar, Jain, Suresh and Bangdiwala2004; Jeyaseelan et al., Reference Jeyaseelan, Kumar, Neelakantan, Peedicayil, Pillai and Duvvury2007; Ghouri & Abrar, Reference Ghouri and Abrar2010; Naved & Persson, Reference Naved and Persson2010). The need to seriously address this problem and provide the necessary support services for such women thus assumes great significance.

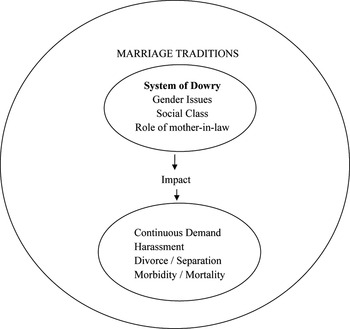

In India, the lifetime prevalence of domestic violence among married women has been found to be 26% (Jeyaseelan et al., Reference Jeyaseelan, Kumar, Neelakantan, Peedicayil, Pillai and Duvvury2007). The same study reported that among the common causes of violence the practice of dowry emerged to be a particularly significant risk factor (OR 3.2; 95% CI 2.7–3.8). Dowry-related violence is severe in India with about 8000 dowry harassment deaths reported in 2011 (United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, 2012). The phenomenon of dowry, and the violence associated with it, is embedded in the institution of marriage in India. An understanding of the socio-cultural context will provide the necessary backdrop to this current study (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Socio-cultural context of dowry in India.

Socio-cultural context of dowry in India

Marriage traditions

Traditionally marriages in Indian society are ‘arranged’ (Bhat & Ullaman, Reference Bhat and Ullman2014). Family members, priests and, more recently, online match-making sites provide a choice of alliances for families to select from for their daughters and sons. In more conservative families, the bride and groom may not have many decision-making powers, with the parents having the final say, while in others they may be consulted. The bride and groom may not even get to spend much time with each other before their wedding (Banerji et al., Reference Banerji, Martin and Desai2008).

For women particularly, marriage is considered essential and necessary in order to maintain their social status in society. An unmarried woman is criticized and subject to ridicule. Parents, too, are under great pressure to ensure the marriage of their daughters, who are essentially perceived as paraya dhan (others' wealth). Once married a woman is expected to take on the responsibility of looking after her household members, and more importantly to bear children (Blanc, Reference Blanc2001; Go et al., Reference Go, Johnson, Bentley, Sivaram, Srikrishnan and Celentano2003). She is expected to devote her life to her marital family and her ties with her natal family are considerably weakened, with both her husband and mother-in-law determining how often she can visit or communicate with them (Krishnan et al., Reference Krishnan, Subbiah, Khanum, Chandra and Padian2012). Thus, women are restricted to their household duties and totally submissive to the will of their husbands and in-laws (Tichy et al., Reference Tichy, Becker and Sisco2009). Over the years, and with globalization, many young people in India are deciding to choose their own marriage partners and live life on their own terms (Bhat & Ullaman, Reference Bhat and Ullman2014). Despite the gradual liberalization that is taking place, the male dominance of women and the restriction of their roles in families continues to be widely prevalent.

Role of the mother-in-law

Despite the fact that the perpetrators of domestic violence against women are usually their husbands or intimate partners, the role played by mothers-in-law in both instigating and exacerbating it cannot be underestimated (Khosla et al., Reference Khosla, Dua, Devi and Sud2005; NFHS-3, no date). Muthal-Rathore et al. (Reference Muthal-Rathore, Tripathi and Arora2002) described how 40% of 168 women admitted to a post-natal ward in New Delhi spoke of their mothers-in-law as being the main instigators of violence against them in their marital home. Krishnan et al. (Reference Krishnan, Subbiah, Khanum, Chandra and Padian2012), in their study aimed at developing interventions to mitigate domestic violence, described how on very many occasions mothers-in-law were instrumental in creating both conflict and violence. This was particularly evident in cases where the mother-in-law perceived her daughter-in-law to be getting in the way of her relationship with her son; or where she felt her daughter-in-law was not suitably obedient to her or to her son; or if the dowry she brought was not adequate; or if her daughter-in-law failed to produce a son. In fact, upon marriage many women are under intense pressure, not just from their husbands, but also from their mothers-in-law and other family members, to prove their fertility (Barua & Kurz, Reference Barua and Kurz2001; Jejeebhoy & Sebastian, Reference Jejeebhoy and Sebastian2003; Rocca et al., Reference Rocca, Rathod, Falle, Pande and Krishnan2009), and failure to do so invariably results in domestic violence against her. In most cases women bear the abuse in silence as they are uncomfortable talking about family matters with outsiders. While Krishnan et al.'s (Reference Krishnan, Subbiah, Khanum, Chandra and Padian2012) study also reported cases of mothers-in-law being supportive and helpful to their daughters-in-law, the fact remains that culturally, mothers-in-law tend to dominate and control their daughters-in-law, often to the detriment of their physical and mental health.

The system of dowry

Dowry refers to the payment of cash or provision of gifts by the bride's family to the bridegroom's family along with the giving away of the bride (called kanyadaan), a custom typical of Indian marriages. It originated in upper caste families as the wedding gift to the bride from her family and later was given to help with marriage expenses. In India, dowry plays a major role in the institution of marriage. Giving away a large dowry is like a status symbol, which contributes to enhancing social status (Stone & James, Reference Stone and James1995; Bulbeck, Reference Bulbeck1998). Furthermore, these dowry demands do not just end with the marriage, but continue on throughout the woman's marital life as a means of appeasing the husband (Sharma, Reference Sharma and Uberoi1993; Kumar, Reference Kumar2003). It is important to state here that, historically, the practice of dowry aimed at providing some wealth to women, who at that time were not entitled to inherit any family property (Sharma, Reference Sharma and Uberoi1993). It was also seen as a ‘mechanism for investment, inheritance, an equalizing force between genders and social classes’ (Shenk, Reference Shenk2007). But somewhere along the way this supportive mechanism became a means for the exploitation and the continued harassment of women.

Although dowry has since been prohibited by the Dowry Prohibition Act of 1961, its practice continues to be widely prevalent much to the detriment of many families who, owing to social and cultural compulsions, end up raking together dowries way beyond their means in order to get their daughters married (Azad India Foundation, 2013). According to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB, 1998 & 2010), India has by far the highest number of dowry-related deaths in the world, with 8391 dowry death cases reported across India in 2010. This means a bride is burned every 90 minutes, or dowry issues cause 1.4 deaths per 100,000 women each year in India. This figure is likely to be a gross underestimate because many crimes against women go unreported on account of social stigma (Hitchcock, Reference Hitchcock2001). Families who are dissatisfied with the dowries brought by their daughters-in-law vent their anger by physically and psychologically abusing the brides. Often the abuse takes such severe forms that the young bride may be killed or is forced into committing suicide (Kumar, Reference Kumar2003; Ahmed-Ghosh, Reference Ahmed-Ghosh2004). Studies have also found that the likelihood of women experiencing marital violence is greater if they bring small dowries or if their in-laws are dissatisfied with the dowry they bring (Vindhya, Reference Vindhya2000; Rocca et al., Reference Rocca, Rathod, Falle, Pande and Krishnan2009). Further, in cases where the marriage of the girl gets delayed and she crosses into her thirties, her parents have to pay larger dowries to ensure her marriage (Chowdhury, Reference Chowdhury2010). Thus the practice of dowry so entrenched in Indian society is all too often responsible for causing pain and anguish for many women.

Dowry and social class

Gender inequalities and social class do exert an influence on the demand for dowry. Dowry plays an important role in enhancing the financial status of a family. With an increase in the desire for material wealth many families see the dowry brought by their daughters-in-law as a means of fulfilling that need. While wealthy families are able to scale-up and provide big dowries in keeping with latest trends, those belonging to the poorer sections of society face an enormous burden. Quite often they are forced into taking huge loans, the repayment of which takes an immense toll on the family finances and can even severely impoverish them. In other cases, an inability to pay these dowries causes families to face the social ignominy of keeping their daughter unmarried in their homes, thereby strengthening the belief that girls are economic liabilities (Anderson, Reference Anderson2007; Ali et al., Reference Ali, Árnadóttir and Kulane2013). Dowry-related violence and deaths thus seriously impact on a woman's physical and mental health contributing to increased morbidity and mortality and also serve to severely undermine the position of women in Indian society. Given the negative impact of dowry and its role in contributing to violence, this paper presents findings from the India Studies of Abuse in the Family Environment (IndiaSAFE) (Bangdiwala et al., Reference Bangdiwala, Ramiro, Sadowski, Bordin, Hunter and Shankar2004; Sadowski et al., Reference Sadowski, Hunter, Bangdiwala and Muñoz2004; Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Jeyaseelan, Suresh and Ahuja2005; Jeyaseelan et al., Reference Jeyaseelan, Kumar, Neelakantan, Peedicayil, Pillai and Duvvury2007), which examines domestic violence in the family environment. This study specifically looks at the prevalence and risk factors for dowry demand, dowry harassment and its psychosocial correlates across different social strata in India. More specifically, the study also examines certain husband (education, socioeconomic status, alcohol use) and mother-in-law characteristics (socioeconomic status and prior experience of dowry demand) to determine their influence on dowry demand and harassment.

Methods

Setting

The IndiaSAFE study was conducted during the period April 1998 to September 1999 by the Indian Clinical Epidemiology Network (IndiaCLEN) in collaboration with the International Clinical Epidemiology Network (INCLEN) as part of the World Studies of Abuse in the Family Environment (WorldSAFE) study (Sadowski et al., Reference Sadowski, Hunter, Bangdiwala and Muñoz2004). The study was based in seven medical schools located in New Delhi, Lucknow, Bhopal, Nagpur, Chennai, Trivandrum and Vellore (see Fig. 2 for site locations). Using population proportionate to size (PPS) sampling, data were collected from rural, urban slum and urban non-slum strata in the seven sites. Slums were defined as residential areas where the dwellings were unfit for human habitation by reason of dilapidation, overcrowding, lack of ventilation, light or sanitation facilities or a combination of these factors (Census of India, 2011). Rural areas (countryside and villages) were predominantly defined by the agrarian nature of their economy and their low population density, while urban non-slum areas were defined as areas inhabited by people of middle and higher socioeconomic status.

Fig. 2. Geographical locations of the study sites, India.

Sample selection

Previous studies have estimated the prevalence of intimate partner violence against women in India at 20–50% (Schuler et al., Reference Schuler, Hashemi, Riley and Akhter1996; Jeyeebhoy, Reference Jejeebhoy1998). Assuming a prevalence of 40%, at a precision of 2% with a 95% confidence interval and a 15% drop-out rate, the sample size in each stratum was estimated at a minimum of 3200 respondents. At each of the seven sites in the study, only two of three different strata (rural, urban slum, urban non-slum) were selected based on the availability of these strata and also to have a balance in numbers. The detailed selection of households from each stratum is presented elsewhere (Jeyaseelan et al., Reference Jeyaseelan, Kumar, Neelakantan, Peedicayil, Pillai and Duvvury2007). Women aged 15–49 years and whose marriages had been arranged by their families were eligible for inclusion in the analysis. Women aged 50 years and above and those not residing with their husbands for the past 12 months were excluded. The interviews were conducted in privacy after obtaining informed consent. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Christian Medical College, Vellore, India.

Study instrument

A structured interview schedule was developed to measure domestic violence. One component specifically focused on dowry demands and dowry-related harassment. There were a total of eight questions under this section, which sought to elicit whether the woman had experienced any dowry demand, whether or not her marital family was satisfied with the dowry she had brought during marriage and whether she had been harassed because of an inadequate dowry. These items were devised following a review of the literature for a better understanding of the phenomena and following interviews with women to obtain first-hand experiences. To ensure comparability between the different study regions, the instrument was translated into the local language of the sites (i.e. Hindi, Marathi, Tamil and Malayalam) and then back-translated into English. All the back-translations were thoroughly checked to ensure that the meaning of the original English language version was retained. An intensive joint training session was conducted for the research staff from all sites. An inter-rater reliability exercise revealed an ICC of 0.75.

Socioeconomic status

Possession of a greater number of household appliances, such as a refrigerator, gas or electric stove, television and air conditioner, and ownership of a vehicle, were considered indicative of higher socioeconomic status. It was classified into three categories, namely low, moderate and high socioeconomic groups. Based on the normal distribution concept, cut-off scores were identified that corresponded to the 33rd and 66th percentiles. Subjects whose scores were less than the 33rd percentile cut-off value were categorized as belonging to a low socioeconomic group. Those who fell between the 33rd and 66th percentile cut-off values were categorized as belonging to a moderate socioeconomic group and those who obtained scores above the 66th percentile were classified as belonging to a high socioeconomic group (see Bangdiwala et al., Reference Bangdiwala, Ramiro, Sadowski, Bordin, Hunter and Shankar2004, for details).

Outcome variables

The phenomenon of dowry demand was measured as a dichotomous variable (yes and no). The dowry harassment response was measured along a three-point continuum, ranging from: 1 ‘very much’, 2 ‘somewhat’, and 3 ‘not at all’. In order to simplify the interpretation, the response options were converted into a binary variable using only ‘yes’ (which included the ‘very much’ and ‘somewhat’ categories) and ‘no’ (which constituted the ‘not at all’ category) options.

Statistical analysis

A data-entry system was developed using Visual Basic as the front end and Visual Foxpro as the back end. The Biostatistics Research and Training Centre (BRTC) at the Christian Medical College, Vellore, was responsible for data management. As the two primary outcomes of ‘dowry demand’ and ‘dowry harassment’ were binary (yes or no), t-test and chi-squared tests were performed to assess the relationship of the continuous and categorical explanatory variables with each of the outcomes. Variables with a p-value <0.25 were considered for the multivariate logistic regression analysis. The Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic was used to assess the model goodness-of-fit. Interaction of some relevant risk factors with dowry demand was also considered to address dowry harassment.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of sample

A total of 11,845 women (rural 3969, urban slum 3756, urban non-slum 4120) were contacted, of whom 9938 agreed to participate (rural 3611, urban slum 3155, urban non-slum 3172). Of these, 7139 (71.8%) were in arranged marriages. The mean age of the women was 31±7 years. There were 44.7% women who had less than 5 years of education and about 43% had undergone 10–12 years of education. The remaining 12% had undergone more than 13 years of education. Approximately 39%, 27% and 33% of the women belonged to low, middle and high socioeconomic status groups, respectively. About 30% of the women's husbands had undergone less than 5 years of education, while about 17% of the husbands had undergone 12 years of education.

Prevalence of dowry demand and harassment

Table 1 presents the prevalence of dowry demand and harassment over dowry stratified by urban slum, urban non-slum and rural areas among women in arranged marriages. In nearly a quarter of the arranged marriages, dowry had been demanded by the groom's family, with the proportions being significantly (p<0.001) higher in the urban non-slum and rural areas (26% and 23% respectively) as against the urban slum (18%) areas. Overall, 17% of the groom's family were not satisfied with the dowry, this being highest in rural areas (21%) as compared with urban slum and non-slum areas (about 14% in both). The overall prevalence of dowry harassment (combining both ‘very much’ and ‘somewhat’) among this group of women was 13.3%.

Table 1. Dowry demand and harassment by social stratum, India, 1998–99

Table 2 presents data on the types of harassment meted out to women by members of their marital family owing to their dissatisfaction with the dowry brought by her. A total of 870 (13.3%) women reported experiencing this harassment to a greater or lesser extent. Of them, nearly half were not allowed to visit their parents, were not permitted to buy things for themselves and had their personal belongings taken from them. These harassments were highest in the rural areas, followed by urban slum and urban non-slum areas, an association that was statistically significant (p<0.001). Overall, nearly 70% of the women did not have any voice in decision-making, with this being the highest in the urban slum areas (71%), followed closely by the rural and urban non-slum areas (69% and 63% respectively). Similarly, being humiliated was also commonly reported, with over 80% of women across all three study strata experiencing it. Being physically beaten, sent back to her parental home and being treated like a servant were highest in the urban slum areas (56%, 42% and 53%, respectively), followed by the rural areas (46%, 43% and 49%, respectively) and least in the urban non-slum areas (28%, 22% and 31%, respectively). This association was statistically significant (p<0.001).

Table 2. Types of dowry harassment by social stratum, India, 1998–99

Risk factors for dowry demand

The results of unadjusted and adjusted analyses for dowry demand are presented in Table 3. The findings show that, with an increase in the age at marriage of the groom, the risk of dowry demands decreased, but this was not statistically significant. However, as the bride's age at marriage increased, the risk of dowry demand also increased. The appliances score was negatively associated with dowry demand; that is, those who were affluent were less likely to demand dowry (AOR=0.8; 95% CI: 0.6–1.1).

Table 3. Risk factors for dowry demand (N=839), India, 1998–99

MIL, mother-in-law.

Interaction effects on dowry demand: husband's education and socioeconomic status

The appliances score was divided into three categories based on the tertile method, namely low, moderate and high socioeconomic status (SES). Education of the husband was dichotomously categorized as ‘literate’ and ‘non-literate’. Those husbands who had only undergone primary level of education (≤5 years of schooling usually meant that they were unable to read and/or write), were also categorized as non-literate. The analysis showed that the socioeconomic status of the husbands more than their education played a significant role in determining whether dowry was demanded. Thus, non-literate husbands who belonged to a lower socioeconomic background were 1.3 (95% CI: 0.8–2.0) times more likely to demand dowry as compared with husbands who were literate and who came from moderate to high socioeconomic backgrounds. Further, husbands with lower socioeconomic backgrounds but who were literate were 2.6 (95% CI: 1.8–3.8) times more likely to demand dowry as compared with husbands who were literate but who had moderate or high socioeconomic backgrounds (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Interaction of socioeconomic status (SES) of in-laws' family with mother-in-law's experience of dowry demand on daughter-in-law's (DIL's) experience of dowry demand.

Socioeconomic status of mother-in-law and her prior experience of dowry demand

Those mothers-in-law with lower socioeconomic backgrounds who had experienced dowry demand at the time of their marriages were 14 times (95% CI: 8.0–26.0) more likely to demand dowry as compared with those with moderate or high socioeconomic backgrounds and who had not experienced any dowry demand during their marriage. Similarly, those mothers-in-law with moderate or high socioeconomic backgrounds and who had experienced dowry demand during their marriage were 7.2 (95% CI: 4.0–12.0) times more likely to demand dowry as compared with mothers-in-law from moderate or high socioeconomic backgrounds who had not experienced dowry demand during their marriage. Lastly, mothers-in-law with lower socioeconomic backgrounds but who had not experienced any dowry demands during their marriage were 2 (95% CI: 1.4–3.0) times more likely to demand dowry. Thus a mother-in-law's experience of dowry demand during her marriage influenced the likelihood of her harassing her daughter-in-law over dowry.

Risk factors for dowry harassment

The results of unadjusted and adjusted risk factor analyses for dowry harassment are presented in Table 4. With an increase in the appliance score (implying a better socioeconomic status), the risk for dowry harassment decreased (AOR=0.9; 95% CI: 0.8–1.0). In cases where the mother-in-law did not have control over the earnings of family members, there was a two-fold greater risk (AOR=2.3; 95% CI: 1.4–3.8) (p<0.001) of her harassing her daughter-in-law over dowry. If the mother-in-law had experienced dowry demand during her marital life, she was also more likely to harass her daughter-in-law over dowry-related issues (AOR=2.4; 95% CI: 1.4–4.2) (p<0.001).

Table 4. Risk factors for harassment due to inadequate dowry (n=839)

MIL, mother-in-law.

Interaction effects on dowry harassment: socioeconomic status of mother-in-law and her dissatisfaction with dowry

Those mothers-in-law who felt that the dowry was inadequate and who came from poor socioeconomic backgrounds were 5 (95% CI: 1.3–18.9) times more likely to harass their daughter-in-law as compared with mothers-in-law from higher socioeconomic backgrounds who had expressed satisfaction with the dowry. Dowry harassment was also seen (AOR=1.7; 95% CI: 1.2–2.5) among mothers-in-law with low socioeconomic backgrounds but who were satisfied with the dowry brought by their daughter-in-law, although to a lesser extent.

Alcohol and dowry harassment

If the husband was alcoholic and demanded dowry, then the odds of dowry harassment were found to be 21.35 (11.26–40.45) (p<0.001) times greater than for non-alcoholic husbands who did not demand dowry (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Interaction of whether the husband is alcoholic and his dowry demand on dowry harassment.

Discussion

This study, which compared and contrasted the prevalence of dowry demand and harassment for a large sample of women across rural and urban sites in India, highlights the harmful and severe nature of this practice. It also attempted to understand how variables such as education, income, alcohol intake and prior experiences of dowry demand combine to exacerbate the risk of dowry demand and harassment for married Indian women, which was found to be higher in urban slum and rural areas than in urban non-slum areas.

The serious adverse consequences of dowry for women are well acknowledged. In 1998, 6917 dowry deaths were recorded in India, an increase of 15.2% over the 6006 deaths in 1997 and 5182 deaths in the year 2010 (NCRB, 1998 & 2010). This figure is likely to be a gross underestimate because many crimes against women go unreported on account of social stigma (Williams, Reference Williams2013). Reports of violence against women whose dowries were considered insufficient by their husbands or their husbands' families are common (Kumari, Reference Kumari1989; Stone & James, Reference Stone and James1995). More recent studies have documented the effect of dowry on women's physical and mental health and of how in India it is a major cause of mortality in women (Vindhya, Reference Vindhya2000; Babu & Babu, Reference Babu and Babu2011; Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2014). In the present study, the prevalence of dowry demand among women in arranged marriages was found to be nearly 23% and harassment due to dissatisfaction with dowry was reported by about 13% of women. This harassment took various forms, ranging from being humiliated, being beaten, not being allowed to visit parents and being treated like a servant. A generous dowry is thus perceived by many parents as essential to ensuring that their daughter is treated well in her new home. The more satisfied a bride's in-laws are with the dowry brought by the bride, the greater the likelihood that she will be treated well in her marital home (Ahmed-Ghosh, Reference Ahmed-Ghosh2004; Rocca et al., Reference Rocca, Rathod, Falle, Pande and Krishnan2009). Further, the risk of harassment of women in this sample increased 21 times if the husband abused alcohol. Alcohol has long been associated with domestic violence, with several studies attesting to this association (Rao, Reference Rao1997; Jeyaseelan et al., Reference Jeyaseelan, Sadowski, Kumar, Hassan, Ramiro and Vizcarra2004; WHO, 2006). While interventions aimed at regulating alcohol availability and prices and alcohol abuse treatment have been carried out in high-income countries, little is known about their effectiveness in countries like India (Stuart et al., Reference Stuart, Ramsey, Moore, Kahler, Farrell, Recupero and Brown2003). Effective intervention strategies specific to India aimed at changing social norms and creating more effective health and judicial systems will go a long way towards reducing the harmful effects of alcohol abuse.

It is important to highlight that the problems of dowry demand and harassment are evident across all strata of society, and are not unique to any one socioeconomic group. However, being economically deprived certainly enhances the desire for more material wealth, as was seen from this study's finding that simply belonging to a low socioeconomic background doubles the risk of dowry demand. Thus the dowry brought by a bride is seen as a pathway to improving a family's financial situation. Ali et al. (Reference Ali, Árnadóttir and Kulane2013) described how the dowry is seen as a source of income by many families in Pakistan, and as a consequence dowry demands are very large. Ghouri & Abrar (Reference Ghouri and Abrar2010) reported that domestic violence due to dowry demand was equally prevalent in rural and urban areas of Pakistan. Other studies too have highlighted that the likelihood of experiencing domestic violence was greater for women belonging to poorer socioeconomic groups as compared with those from higher income strata (Dave & Solanki, Reference Dave and Solanki2000; Panda & Aggarwal, Reference Panda and Agarwal2005). The present study found that poor socioeconomic status, coupled with a mother-in-law's experiences of dowry demand at the time of her own marriage, contributes to an increased risk of both demand for dowry and harassment of the daughter-in-law. This harassment takes the form of both physical and psychological abuse, seriously undermining her physical and mental health.

Another important finding of this study is that the higher the education of a woman, the greater the risk of dowry demand. This could be explained by the fact that in India, parents of highly educated girls look for boys with commensurate educational qualifications, whose price on the marriage market is usually very high. Consequently, the dowry required to arrange such a marriage inflicts a heavy burden on the bride's family. Similar findings were seen in a study conducted in rural India, which found that an increase in schooling levels significantly contributed to increased dowry demands (Chowdhury, Reference Chowdhury2010). A study from Kerala, a state with high levels of female literacy, showed that women's education, employment achievements and contributions to family income were seldom given importance in dowry assessments (Philips, Reference Philips2003). Another study found that factors such as education and urban residence had a negative relationship with dowry demand. This was attributed to exposure and easy access to modern educational systems that challenge conventional thinking about women's lifestyles (Srinivasan & Lee, Reference Srinivasan and Lee2004). However, the employment status of women had no such effect. The present study also showed that dowry demand was less in urban areas. Nevertheless, there was no negative relationship between education of the women and employment status of the mother-in-law with dowry demand. In fact, there was a doubling of the risk of demand if the mother-in-law was employed.

This was a cross-sectional study and thereby suffers from causal temporality of dowry demand and harassment with the risk factors, typical of studies of such design. Further, only those mothers-in-law whose daughters-in-law gave permission for them to be interviewed were included in the study, implying that the nature of their relationship could have been relatively stable and comfortable. The results on dowry demand and harassment are thus likely to be underestimates of the true relationships.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this study has provided substantive evidence on the nature and extent of dowry demand and harassment and of its potential negative impact on women in India. The practice of dowry over the years has become so deeply rooted in Indian culture that mere enactment of laws will in no way serve to mitigate the problem. While the philosophy that fuelled this practice, i.e. provision of a share of the family wealth to the female child, has merit, the mental and physical abuse that has now become common practice cannot and must not be condoned. Banerjee (Reference Banerjee2014), in her review, speaks of the need for educational interventions involving getting families to educate their daughters to be independent and self-reliant, large public health campaigns that stress the value of women and strengthening of legislation, among others, as possible strategies to tackle the problem of dowry. Indeed, all of the above should be combined with the proactive involvement of civil society, who must not only refrain from following this practice but should not remain silent bystanders to its execution.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the International Clinical Epidemiology Network, the International Council for Research in Women and the United States Agency for International Development.