Introduction

There has rarely been a period during the 20th or 21st c. in which the Arch of Constantine has not been subjected to proposed revisions of its chronology (Fig. 1). The last 25 years have witnessed the appearance of as many as seven new monographs or dissertations dealing with Constantine and the arch, each of which has provided a new layer of interpretation previously missing from the discussion.Footnote 1 In this article I add yet another argument to the arch's dossier by proposing that nearly all of the sculpted frieze of the arch, generally regarded as Constantinian, derives from a triumphal monument of Diocletian commissioned shortly after his Vicennalia in 303 CE. The basis of the argument is the sculptural technique evinced by the frieze, especially the separately carved heads of the emperor in four of the frieze slabs, coupled with the missing legs and feet of several of the other figures. These anomalies suggest that much of the frieze was spoliated from another monument that had honored a different man whose portraits were replaced by those of Constantine when his arch was being constructed. Diocletian is the only emperor whose career fits the iconography of the spoliated reliefs. Moreover, a Diocletianic date for most of the frieze blocks necessitates a reconsideration of long-standing interpretations of the spolia on the arch and, in turn, the arch's historiography.

Fig. 1. Arch of Constantine, general view of north side. (Jeff Bondono, IMG_3273 (www.jeffbondono.com).)

Since the magisterial 1939 publication by Hans Peter L'Orange and Armin von Gerkan, the arch has been regarded as a visual panegyric to Constantine, wherein the reliefs of Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius formed part of a political framework designed to present Constantine as the culmination of earlier imperial achievements, not unlike the Fasti Consulares and Triumphales on Augustus’ Parthian Arch.Footnote 2 The incorporation of so much 2nd c. sculpture has, not surprisingly, prompted a wide variety of dates for the arch during the last 120 years of scholarship. In a series of articles written between 1912 and 1915, Arthur Frothingham argued that the arch was initially built by Domitian, while an investigation in the late 1980s/early 1990s by a team from Rome's Istituto Centrale per il Restauro yielded a construction date in the Hadrianic period.Footnote 3 Other scholars, such as Ross Holloway and Sandra Knudsen, have suggested that the arch was initiated by Maxentius during his reign in Rome between 306 and 312 CE, as part of a building campaign that also included the Basilica Nova and the restoration of the Temple of Venus and Roma.Footnote 4 The dominant viewpoint regarding chronology is still that of Von Gerkan and L'Orange, who argued that construction began shortly after Constantine's victory over Maxentius in 312, and this dating has been endorsed by Patrizio Pensabene, Clementina Panella, Jaś Elsner, and Mark Wilson Jones, among many others.Footnote 5

Since the 1939 publication of Von Gerkan and L'Orange, there has been general agreement on the dates, if not the origins, of the 2nd c. CE components: the eight free-standing Dacians in the north and south attic zones, the four slabs of a monumental Dacian War frieze in the central passageway and on the attic at east and west (Trajanic); the eight tondi above the side archways at north and south (Hadrianic); and the eight rectangular panels framed by the Dacian statues (Aurelian). Generally regarded as Constantinian components are the reliefs in the niches of the lateral passageways; the Sol and Luna tondi on the east and west sides, replicating the Hadrianic tondi in size and shape; the spandrel sculptures of Victories and personifications; the keystone reliefs of the central passage; the socle reliefs of Victories, Roman soldiers, and defeated barbarians; and the figural friezes positioned below the tondi that appear on all four sides of the arch.Footnote 6

The frieze and its narrative(s)

The date and significance of the frieze have occasionally been debated in 20th c. scholarship, even though a Constantinian date has typically been embraced. Six individual frieze slabs wrap around the arch: two each on the north and south sides, and one each on the shorter east and west sides (see Fig. 1). The frieze slabs on the Constantinian arch occupy the same position as on the Arch of Septimius Severus, just above the side arches, although the designers of the later arch clearly wanted to present the frieze as a continuous band, thereby necessitating the insertion of smaller reliefs on the corners of the north and south sides, all of which featured one or two soldiers on foot or horseback.Footnote 7 This made it look as if a continuous story was being told, with the small soldier reliefs serving as punctuation marks (Fig. 1).

No two frieze slabs are the same height: they range from 0.99 m (City Siege, see Fig. 2) to 1.34 m (Oratio, see Fig. 8), and they are positioned c. 8 m above ground level.Footnote 8 Normally such figural friezes on triumphal arches evince unity of time and place, which is generally the triumphal procession in Rome, but here each of the slabs features a different subject at different times in different spaces.Footnote 9 The scenes include a battle by a river with rival Roman troops, the siege of a walled Roman city, a marching army, the emperor's festive entry into Rome, an oratio on the Forum Rostra, and a liberalitas in a temporary structure in Rome. The emperor appears in five of the six panels, but his head is missing from four of them (see Figs. 4, 6, 8, 12). In the following discussion, I first review the iconography of each of the frieze slabs, starting with the City Siege, where the emperor's head is preserved, and then consider the broader significance of the missing heads.

Fig. 2. Arch of Constantine, City Siege. (Courtesy L. Lancaster.)

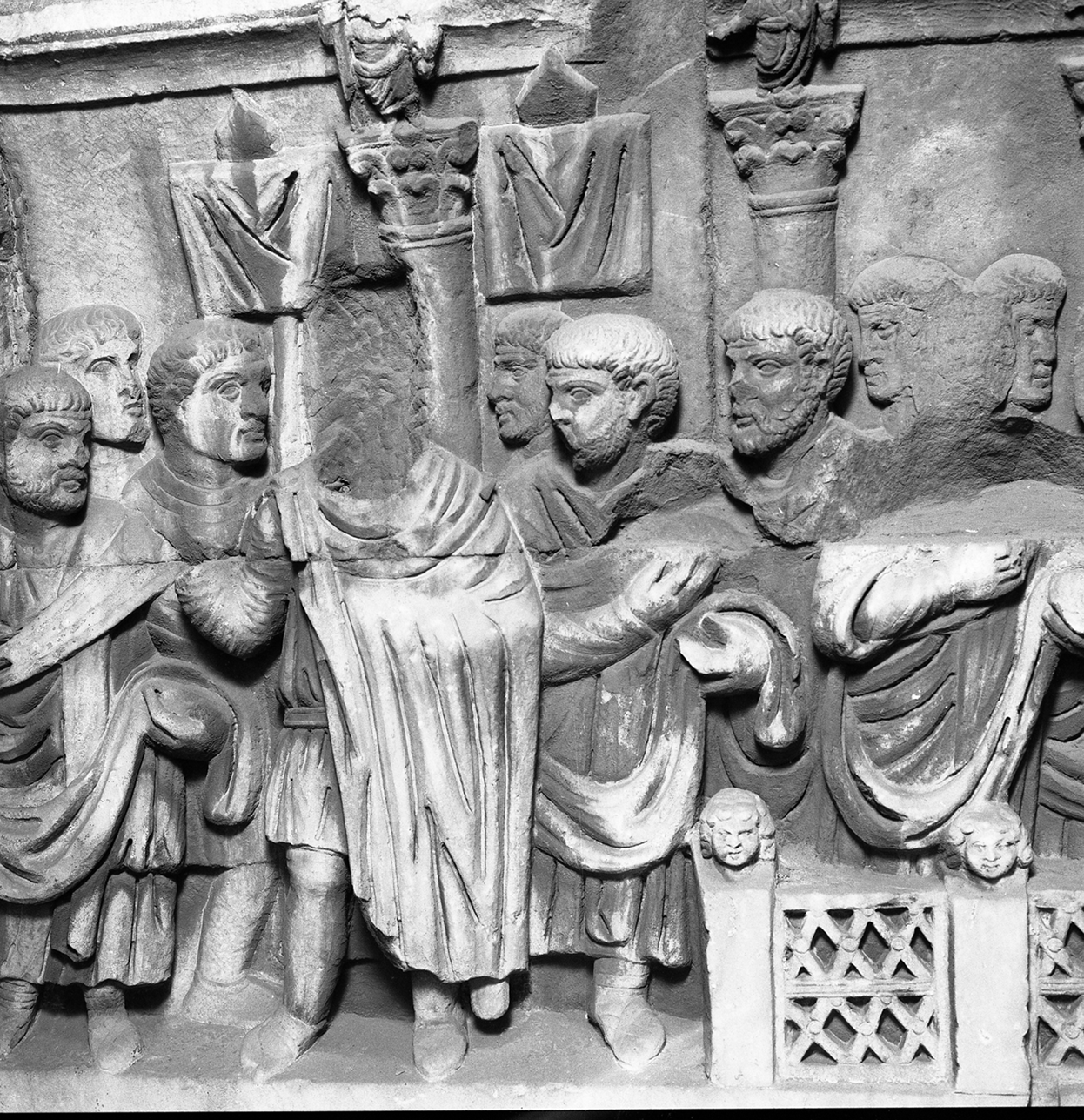

City Siege (south side, left)

A walled city with five towers is attacked by the Roman army at the left, whose presence in two thirds of the frieze presages their ultimate victory (Figs. 2 and 3).Footnote 10 The emperor stands slightly to the left of the squadron's center; he is the only figure who occupies the full height of the frieze, and the visual cadence of large, slightly overlapping shields highlights the force that he commands.Footnote 11 The emperor raises his right arm in a gesture of adlocutio while holding a shield in his left, and wears a cuirass, paludamentum, and bracae. He is about to receive a laurel crown from the Victory at the left who flies toward him. Behind him stand two bodyguards, a saddled horse, and a laurel tree, the branches of which nearly touch the foot of the Victory.

Fig. 3. Arch of Constantine, City Siege, detail of emperor. (D-DAI-ROM-32.84.)

The emperor's beardless head was carved with the body, and the damage that it has sustained is attributable to the deterioration of the marble, which is apparent throughout the sculptural decoration of the arch (Fig. 3). The front of the face is still intact, however, demonstrating that there has been no attempt at iconoclasm. This is the only surviving Imperial portrait on the frieze.

The unit to the right of the emperor is composed of nine men organized in two rows, with four javelin throwers in the front. Two more javelin throwers appear in the back line, as do three archers who are Moorish auxiliaries. A tenth soldier has already reached the walls of the city and uses his shield as protection from the javelins hurled from above. The citadel features five two-storied towers with arched windows, behind which eight defenders throw spears and stones at the attackers. A ninth defender falls headfirst from the battlements, thereby contrasting sharply with the charging Roman at the right. This is the only frieze slab featuring an emperor in which all of the figures are beardless, a point to which I will return when arguing that the other slabs are spolia.Footnote 12

River Battle (south side, right)

The vast majority of this frieze depicts a battle between rival Roman forces in and around a river (Figs. 4 and 5).Footnote 13 The Romans in the upper part are both foot soldiers and equestrians in a largely isocephalic format. We should presumably view them as riding along the banks of a river. They are dressed in tunics, bracae, and helmets of the same type as those of their enemy. All of their opponents fight from the river, an endeavor complicated by their heavy scale armor that easily distinguishes them from their rivals. Several lift their arms in supplication; others are dying.

Fig. 4. Arch of Constantine, River Battle. (Courtesy L. Lancaster.)

Fig. 5. Arch of Constantine. River Battle, detail of emperor with separately worked head, now missing, at top center. (Barbara Bini Collection, Photographic Archive, American Academy in Rome, AC_33_8.)

The left and right corners feature a less crowded composition. At the left stands the emperor on the prow of a ship, just past a bridgehead, flanked by Victory at the right, a river god below, and Virtus or Roma at the left. Most of the emperor's body has broken off, although one can still see his sandaled feet, part of a sword on his hip, and a corner of his paludamentum, which indicates that he would have worn a cuirass. Much of the molding above him has broken, causing his torso and legs to flake off, but the head cavity was clearly and carefully prepared for the insertion of a separate portrait (see Fig. 5).Footnote 14 At the right Victory raises a laurel crown over the emperor's head while holding a palm branch in her left hand. Whether the figure at the left is Roma or Virtus cannot be determined since both are frequent additions to battle scenes and wear identical costumes; if it is Roma, however, she is on the wrong side of the river, so perhaps Virtus is more likely. Standing at the end of a bridge of which one arcade is visible, she holds a shield and lance in her hands and leans diagonally in the direction of the emperor. At the far right are two horn players standing on the banks next to an arch, which probably indicates a city or fortress gate.

Adventus (east side)

This depiction of the emperor's formal entry into the city of Rome is reminiscent of Ammianus Marcellinus’ description of Constantius II's arrival in Rome in 357 CE, our most evocative literary treatment of an imperial adventus (see Figs. 6 and 7).Footnote 15 The emperor appears at the left in an ornate four-wheeled cart drawn by four horses and driven by Victory. The cart has just passed through an archway within which a soldier stands with a vexillum. This is presumably a city gate, and has been articulated by carefully incised lines indicating masonry. The emperor wears a long-sleeved belted tunic, chlamys, bracae, and shoes adorned with a gem at the front. In his left hand he holds a scroll and he raises his right hand in greeting; his head was separately inserted.

Fig. 6. Arch of Constantine, Adventus. (Courtesy L. Lancaster.)

Fig. 7. Arch of Constantine, Adventus, detail of emperor with separately worked head, now missing. (D-DAI-ROM-0963-F01.)

The cart in which he rides features an elaborately decorated high-backed chair or cathedra with armrest and acanthus friezes at top and bottom, the former of which includes pendant vine leaves. Equally impressive are the horses pulling the cart, in that gem inlays or appliqués decorate their harnesses, bridles, and neck straps, from which bells signaling the arrival of the emperor have been hung. The iconography beautifully complements Ammianus’ description of the cart of Constantius II: “He himself sat alone upon a golden car in the resplendent blaze of shimmering precious stones, whose mingled glitter seems to form a short of shifting light.”Footnote 16 A similar imperial cart appears on the Galerius Arch in Thessaloniki (ca. 298–303 CE), albeit only two-wheeled, and on the newly discovered Diocletianic reliefs from Nicomedia (ca. 293 CE), where the high-backed chair is colored purple.Footnote 17

The military procession in front of the imperial cart occupies the remainder of the frieze and proceeds around the corner onto the north side. The arch that appears at the right end continues into the north extension, where four overlapping elephant heads are still visible on the spandrel, thereby identifying the arch as the Porta Triumphalis of Domitian. Where precisely that arch was located continues to be debated, but its presence on the frieze clearly demonstrates that Rome was the setting for the procession.Footnote 18

Over 30 soldiers wearing parade armor march in the procession, some of whom have been given crow's feet around their eyes to highlight their long years of service (see Fig. 7), even though such details would have been invisible from the ground. The figures are organized in upper and lower zones, as in several of the other frieze scenes, and comprise both foot soldiers armed with shield and spear, and equestrians armed with a lance, of which there are four in each row. The Moorish auxiliaries, identifiable by their corkscrew curls, wear the long-sleeved tunic and are bareheaded. Two of the soldiers carry dragon banners or dracones, which would be featured in Constantius II's adventus as well:

And behind the manifold others that preceded him he was surrounded by dragons, woven out of purple thread and bound to the golden and jeweled tops of spears, with wide mouths open to the breeze and hence hissing as if roused by anger, and leaving their tails winding in the wind.Footnote 19

Ammianus’ passage not only provides a sense of sound to accompany the image, but also indicates the colors that would have been used to highlight the parade equipment.

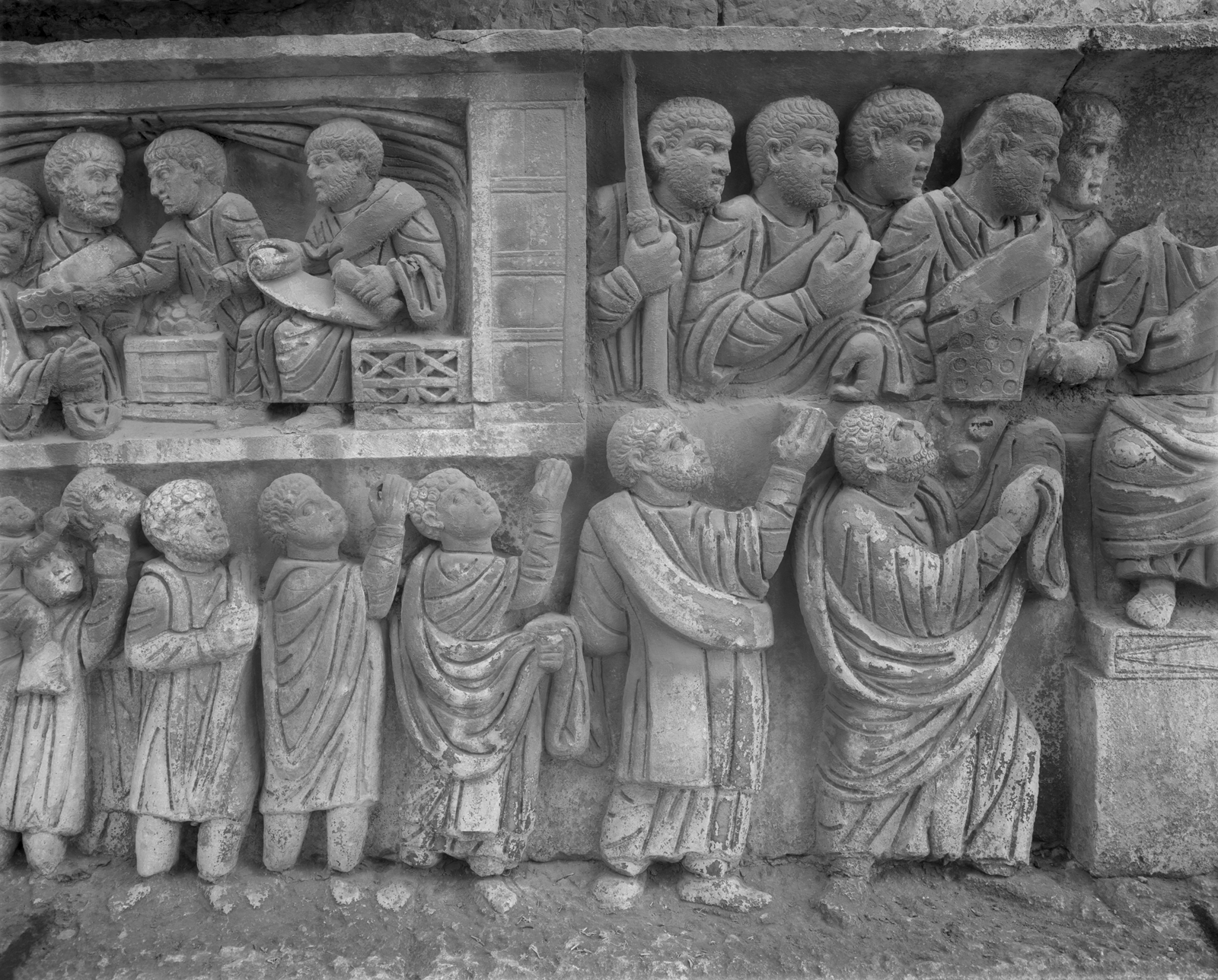

Oratio (north side, left)

With over 60 figures, the Oratio is the most crowded of the six frieze slabs, and one of only two featuring a centralized composition (Figs. 8–11). The setting is the Rostra on the western side of the Roman Forum, behind which is the Five-Column Monument with statues of Jupiter and the four Tetrarchs, thereby indicating that the frieze could not have been carved prior to 303 CE.Footnote 20 The Arch of Septimius Severus appears in the background at the right, with the Arch of Tiberius and the Basilica Julia at left.

Fig. 8. Arch of Constantine, Oratio. (Courtesy L. Lancaster.)

In the center of the Rostra, the emperor in military attire raises his right hand to address the people who assemble at either side in two isocephalic rows. He wears a long-sleeved belted tunic, bracae, chlamys, and shoes with gemstones; his head was separately attached (see Fig. 9). Surrounding him on the Rostra are imperial guards with vexilla and a group of bearded and togate senators, some of whom raise their right hands in acclamation. The stage is flanked by seated togate statues of Marcus Aurelius at the left and Hadrian at the right.Footnote 21 Conspicuously absent are the actual rostra that provided the structure with its name. The onlookers, who include males of all ages, wear long-sleeved knee-length tunics with an occasional cloak, and are approximately the same height as the emperor and senators.

Fig. 9. Arch of Constantine, Oratio, detail of emperor with separately worked head, now missing. (Barbara Bini Collection, Photographic Archive, American Academy in Rome, AC_8_1.)

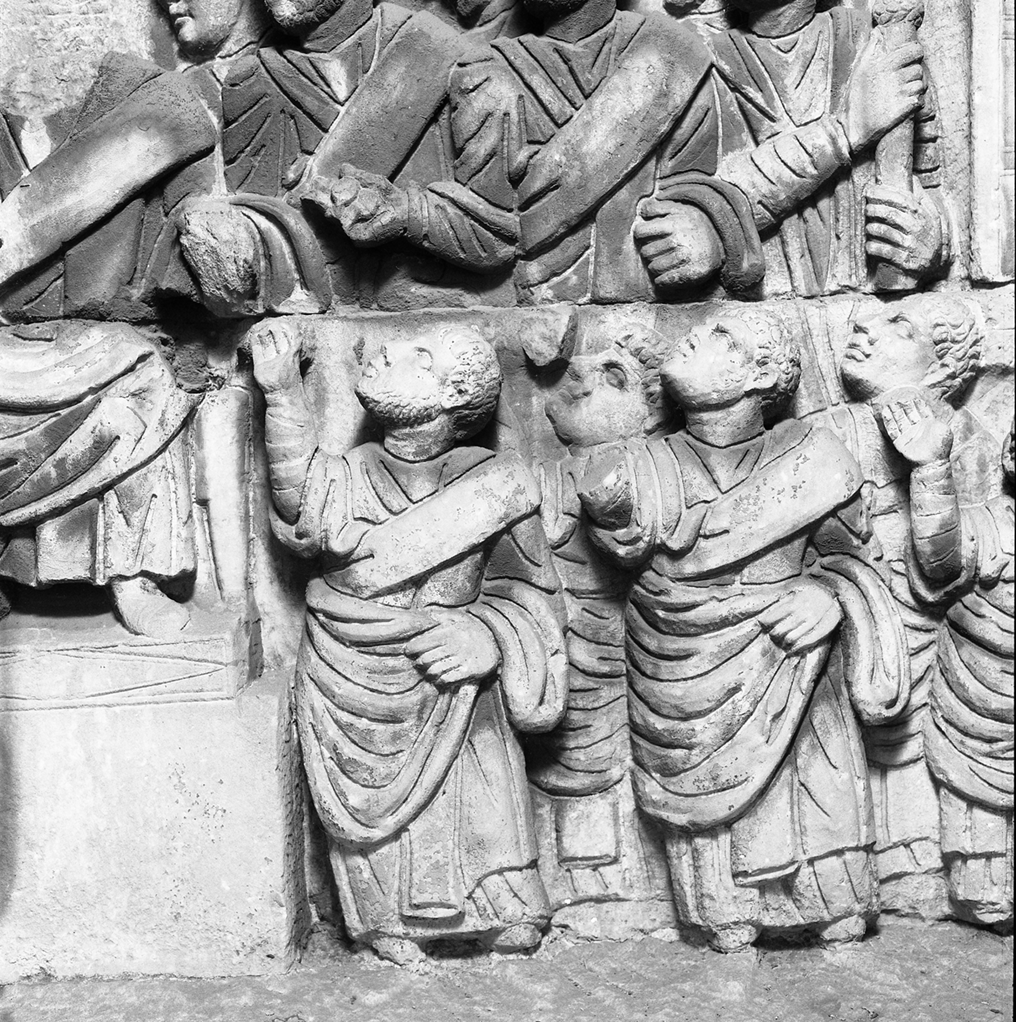

The base of the relief has been trimmed to reduce its height, thereby cutting off the lower legs and feet of the onlookers, as well as the base of the Rostra (see Figs. 10 and 11). Replacement feet have been carved on the blocks below the frieze, although not always in alignment with the associated legs, and the rendering of new feet was often abandoned altogether (Fig. 11). Even when replacement feet do fit the legs above them, one can clearly see a disconnect between old and new blocks (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Arch of Constantine, Oratio, detail of left side of Rostra and figures at left. (D-DAI-ROM-32.10.)

Fig. 11. Arch of Constantine, Oratio, detail of figures at right with missing lower legs and feet. (D-DAI-ROM-32.7.)

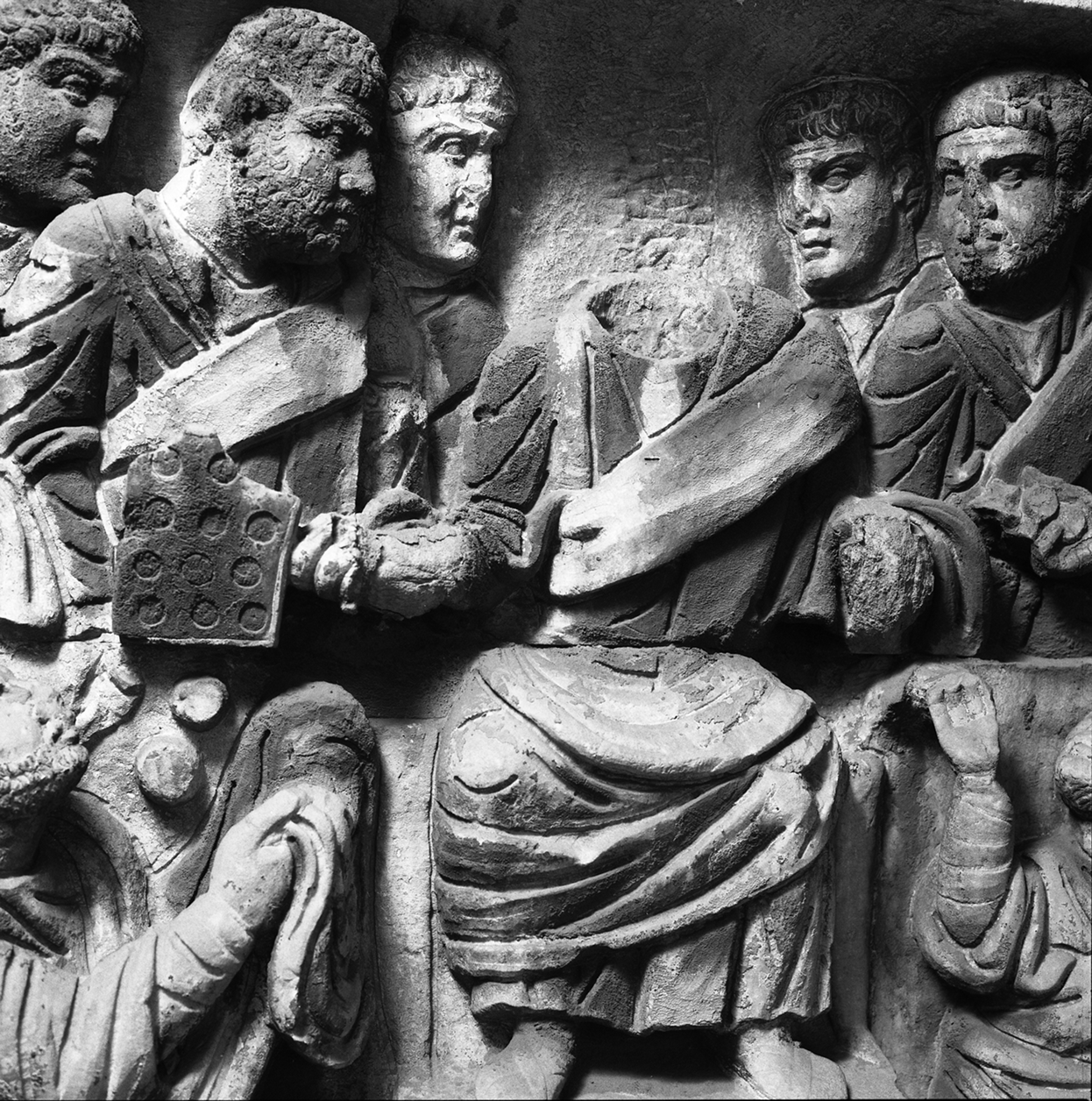

Liberalitas (north side, right)

In the final scene to be discussed here, the emperor distributes money to the populace from a centralized podium, as do four groups of associates (Figs. 12–17).Footnote 22 The emperor is shown frontally, wearing a contabulatio toga, and is taller than anyone else in the frieze even though he is seated (Fig. 13). The head was separately attached. He holds a scroll in his left hand and a special rectangular counting device in his right, probably made of wood, which is a standard feature of liberalitas scenes. The device in question, often referred to as a tabula, contains 12 circular depressions intended to hold the coins in an allotment, which the emperor pours into the toga folds of the man standing below and to the left of his chair. Standing on a raised platform behind the emperor are togate senators and officials, while an attendant on each side of the group holds a wax candle decorated with laurel (see Figs. 14 and 16).Footnote 23

Fig. 12. Arch of Constantine, Liberalitas. (Courtesy L. Lancaster.)

Fig. 13. Arch of Constantine, Liberalitas, detail of emperor with separately worked head, now missing. (Barbara Bini Collection, Photographic Archive, American Academy in Rome, AC_15_11.)

Fig. 14. Arch of Constantine, Liberalitas, detail of figures at center left with missing lower legs and feet. (D-DAI-ROM-32.11.)

On each side of the relief are two-storied structures with two accounting offices on the second floor, where the liberalitas continues in operation. In each office are four men grouped around a money chest in the center, and the inclusion of only the upper body of one figure indicates that he is walking up the stairs to the second-floor office. A togatus reads the name of the recipient or writes his name down, while another bends over the chest and holds a tabula with six coin slots (see Fig. 15), so half the amount of the emperor's tabula.

Fig. 15. Arch of Constantine, Liberalitas, detail of figures at far left with missing lower legs and feet. (D-DAI-ROM-32.14.)

Fig. 16. Arch of Constantine, Liberalitas, detail of figures at center right with missing lower legs and feet. (Barbara Bini Collection, Photographic Archive, American Academy in Rome, AC_21_1.)

The recipients include togate men and ordinary citizens in the same costume as in the Oratio. Several of them, again, have brought their children, and they look up at the officials to whom they raise their hands. Only men and boys are shown; women are absent from all of the scenes on the frieze. As in the case of the Oratio, a cut along the bottom of the relief has removed the figures’ lower legs and feet, and replacements for the latter were often never carved on the block below it (Figs. 14–17).

Fig. 17. Arch of Constantine, Liberalitas, detail of figures at far right with missing lower legs and feet. (D-DAI-ROM-32.13.)

A liberalitas could occur on a variety of occasions, such as imperial accessions, triumphs, anniversaries, or festivals. Enormous numbers of citizens were involved in such enterprises, and an equally enormous amount of money was dispensed. Martin Beckmann has described the logistics surrounding a liberalitas during the reign of Augustus:

The recipients of Augustus's distributions ranged in number from 200,000 to 320,000 (RG 15) and there is no way that such a congiarium could be handed out by only one group of functionaries personally overseen by the emperor. The use of multiple distribution stations is clearly shown on the Arch of Constantine. For example, if these actions could be accomplished for a single recipient in 15 seconds, then about 2,000 distributions could be made by a single administrative team in one eight-hour day, or about 14,000 in a week. At this rate it would require about 14 teams to finish distributing a congiarium to 200,000 recipients in one week.Footnote 24

An enclosed space that allowed for strict crowd control was essential regardless of the size of the liberalitas, but no one complex seems to have been continuously favored during the empire. The liberalitas of Commodus occurred in or next to the Basilica Ulpia; the Porticus Minucia, where grain was distributed, would also have been a possibility, as would the Forum Iulium and the Circus Maximus.Footnote 25 The early 4th-c. liberalitas was probably smaller in scope than that of Augustus, and the structure depicted in the relief is clearly a temporary wooden one. The sides of the offices are incised with lines probably intended to represent posts and horizontal cross-bars that would have been highlighted with paint, and the offices themselves are covered by cloth canopies rather than a wooden roof.

Army March (west side)

An army procession of 20 figures and 6 animals marches from left to right, with the majority of the soldiers clad in cloaks and so-called Pannonian hats while holding spears and shields (Fig. 18).Footnote 26 This is the only frieze slab in which the emperor does not appear. The left half of the procession is dominated by three groups with animals. At the left corner, a four-wheeled cart drawn by four horses moves through an arched structure that is probably a city gate. Within the cart are a coachman and two men conversing with each other.Footnote 27 The cart is escorted by two soldiers – one armed, one unarmed – who march behind the horses.Footnote 28

Fig. 18. Arch of Constantine, Army March. (Courtesy L. Lancaster.)

In front of them are five figures, two of whom are soldiers, marching with a mule loaded with grain sacks and a bundle of spears. A servant crouches on the ground in front of the mule, which is flanked by two grooms or trainers with sticks on their shoulders. The soldier holding the mule's reins looks toward an unusual animal in front of him to which wine skins have been strapped; a soldier at the right pulls on the animal's reins, and his companion carries a stick similar to that used for the pack mule.

Von Gerkan and L'Orange identified the animal as a camel based on its long hooves, flat snout, long narrow hind legs, and the shape of its tail.Footnote 29 The presence of a camel in Late Antique military scenes is not unprecedented – they appear on both the Arch of Galerius in Thessaloniki and the Column of Arcadius in Constantinople.Footnote 30 But the camel's long neck in those scenes is absent here, even though the height of the frieze allowed for a longer neck. It seems likely that the sculptor had never seen a camel before.

Among the remaining eight soldiers in the right section of the frieze are two who hold standards topped by images of Sol Invictus and Victory; the latter holds a laurel wreath in her raised right hand and a palm branch in her lowered left.Footnote 31 A soldier in the right corner carries a horn on his left shoulder.

Dating the frieze, re-reading the narratives

Two especially noteworthy features emerge from this review of the frieze slabs. Each scene occurs at a different time and in a different place: fighting in front of a walled city and then by a river, driving into Rome, speaking in the Forum, and presiding over a liberalitas. In other words, there is an absence of the temporal and spatial unity that one finds in every other frieze on a triumphal arch. The other feature, which is even more striking, involves the separately carved heads of the emperor, now missing, in four of the five panels in which he appears (Figs. 5, 7, 9, 13). This discomforting fact has usually been avoided in scholarship on the arch, although a few have tried to make sense of it, beginning with A. J. B. Wace as early as 1907. He noted the missing heads in the Oratio, Liberalitas, and Adventus scenes, and argued that these three reliefs and the one with the marching army had first been carved for Diocletian, whose heads were replaced by those of Constantine when the frieze was added to the arch.Footnote 32 The City Siege and River Battle scenes he regarded as Constantinian.

But Wace failed to note the missing head of the emperor in the River Battle, which contradicted the model that he had formulated: if each emperor with a missing head was Diocletian, and yet the River Battle represented the Milvian Bridge, then the argument falls apart. This problem was highlighted by Arthur Frothingham in a series of articles on the arch written between 1913 and 1915.Footnote 33 Frothingham's interpretation of the arch was highly idiosyncratic: he subscribed to a Domitianic origin, and believed that it received new sculptural ornamentation continually until the reign of Constantine. He also proposed that the friezes could be divided into two groups based on style and technique: the Oratio and Liberalitas in one group, and the other four in the second one. These two groups he attributed to two different emperors of the 2nd half of the 3rd c. CE, without specifying who they were or how the battle scenes should be read.

The viewpoints of both Wace and Frothingham were criticized in the authoritative publication of the arch by L'Orange and von Gerkan in 1939, who argued that all of the frieze scenes were Constantinian, and that the emperor's portrait had been specially made to fill the four head cavities as part of the original plan.Footnote 34 Sandra Knudsen contested this viewpoint in a talk at the 1989 AIA annual meeting, in which she proposed that all six of the frieze slabs had been spoliated from a Maxentian monument, but otherwise the interpretation of L'Orange and von Gerkan has been generally embraced by scholars.Footnote 35

One other proposition worthy of note was advanced in 1992 by Horst Bredekamp, who suggested that the imperial heads might have been defaced in 1534 by Lorenzino de Medici, an afficionado of Republican Rome who reportedly mutilated sculptures on the Arch of Constantine and in other parts of Rome.Footnote 36 This was an attack that happened covertly in the middle of the night, and yet he could not have battered the frieze without erecting substantial scaffolding on three sides of the arch, which would have taken days, probably weeks, but not hours. Lorenzino would also have had to make the perplexing decision to deface the smallest heads of the emperors, i.e., those on the frieze, while leaving intact the larger recut heads of Constantine on the 2nd c. CE reliefs. Furthermore, he would have needed an expert in Roman sculpture to identify the imperial portraits since it was not always obvious which ones they were. Lorenzino's iconoclasm was likely limited to the reliefs in the side passageway niches, which were easily reachable within a short period of time.Footnote 37

An argument along the same lines was advanced at the beginning of the 20th c.: Josef Wilpert proposed that the imperial heads were defaced as part of a post-Constantinian pagan reaction, but since the larger recut heads of Constantine in the 2nd-c. reliefs were left intact, the argument carried little weight.Footnote 38 Equally unlikely for the same reason is a relatively recent proposal by Ross Holloway that the heads were removed following Constantine's visit to Rome in 326 CE because he refused to sacrifice to Jupiter.Footnote 39

In the final analysis, one needs to consider whether there is merit to the proposal of L'Orange and von Gerkan that the missing heads are simply related to Roman workshop technique. If they are not, then with which emperor should their creation be associated, and what kind of monument might they have adorned?

The sculptural technique issue is the crux of the problem. Roman sculptors carved portraits, both imperial and private, as part of the relief; portraits were not separately carved and then added to the relief. The reason is simple: if they were carved as part of the relief, they were likely to remain attached to the relief in question. If they were carved separately, they were more likely to become detached, as has happened to the imperial heads on this frieze. The carving of heads as part of the relief surface is a feature of every Imperial relief that has ever been found, including the 2nd-c. reliefs on the Arch of Constantine and those on the Arch of Galerius at Thessaloniki, carved only 15 years before the Arch of Constantine.Footnote 40

One finds the same technique employed in the carving of sarcophagi, which featured the only reliefs produced between the Severan and Tetrarchic periods. The portrait was often left as a lump of unformed marble on an otherwise completed relief so that it could be individualized as the decedent when the sarcophagus was purchased. These portraits were never carved separately and subsequently attached. Even assuming that such a technique was employed for the frieze, it would still not explain why the emperor's portrait in the City Siege was carved in one piece with the relief if separable heads were part of the sculptors’ work plan.

This unusual carving treatment suggests the following scenario. The reliefs were originally carved with the imperial heads forming part of the relief; those heads were later carefully chiseled off and replaced by the separately carved heads, now missing, although the cavities cut to receive them are clearly visible. Such a replacement would only have happened as part of a program of reuse that presented a different emperor than the one originally portrayed. Fortifying these conclusions are the missing legs and feet in the Oratio and Liberalitas scenes, which had clearly been cut off during the spoliation process (Figs. 11, 14–17). The portrait heads could have been reworked while the reliefs were still in situ, but the cut-off legs demonstrate that this reuse entailed spoliation and reinstallation of most of the frieze slabs.

Consequently, in the sections that follow, I regard the existence of a separately attached head as an indication of a Tetrarchic origin and a Constantinian reuse. In other words, it seems likely that the City Siege represents a genuine Constantinian addition to a series of frieze slabs that had been spoliated from another monument and that originally honored a different man.

The presence/absence of beards is worthy of special note in this dating scheme. The emperor in the City Siege is beardless, as are all of the figures in that scene (Figs. 2 and 3),Footnote 41 whereas the figures in the other scenes are generally bearded. This was not an insignificant innovation: at the advent of the Constantinian period, emperors had worn beards for the previous 200 years, since the reign of Hadrian, and the beard's removal from Imperial types represented a major change in portrait styles. In this case, the traditional identification of the scene as Constantine's battle at Verona in 312 CE fits the iconography well and complements the Constantinian panegyric that refers to the attack on the fortified city.Footnote 42

But what can one say about the original context of the other frieze panels with separately carved imperial heads? The presence of the Tetrarchic Five-Column Monument in the Oratio scene at the Rostra provides a terminus post quem of 303 CE, although there is nothing in the iconography that indicates a specific emperor (Figs. 8 and 9). The date of the Liberalitas scene is also difficult to pinpoint: liberalitas as a type disappears from coinage after Trebonianus Gallus (251–53 CE), although such donatives continued to occur, as the relief on the arch demonstrates (Fig. 12).Footnote 43

This brings us to the River Battle, which has traditionally been linked to the armed conflict at Rome's Milvian Bridge between Constantine and Maxentius in 312 (Figs. 4 and 5).Footnote 44 In the scenario outlined above, however, the replacement of the original emperor's head with that of Constantine would exclude this interpretation, although the style clearly requires a date in the Tetrarchic period. There is, in fact, nothing in the scene that indicates the location of the battle as Rome. Whether the personification at the left of the scene is Roma or Virtus, she cannot be used to localize the action, since such personifications appear both in Rome and on the battlefield far from the capital, as attested by Trajan's Dacian War relief on the Constantinian arch's central passage, or the Persian conquests on the Galerian Arch.Footnote 45 The style and iconography only allow us to say that a battle between rival Roman forces occurred at a river with a town or fortress presumably nearby, as represented by the arch on the relief's right side.

The only possibility that meets all of these criteria is Diocletian's Battle of the Margus River against the emperor Carinus in the summer of 285 CE. The battle involved rival Roman forces fighting on the Margus (Great Morava) River, close to its juncture with the Danube and west of Viminacium, the capital of Moesia Superior (now Serbia).Footnote 46 In the same zone was a Late Antique fortress (Margum Dubravica), which lay approximately 10 km from Viminacium. Diocletian had been the commander of the Imperial bodyguards but was acclaimed emperor in 284 CE by his fellow soldiers after the alleged murder of Numerian, brother of Carinus. These events led to a civil war that reached its climax at the Battle of the Margus River, where Carinus died in the conflict. Diocletian was now in command of the empire, and the river battle's importance in Diocletian's career is not unlike the seminal role played by the Battle of Actium in the life of Augustus.Footnote 47 It also marked the beginning of a period that would witness the foundation of the Tetrarchy, the tenth anniversary of which was celebrated in Rome in 303 CE. In this interpretation, then, Diocletian was the emperor originally standing at the left of this scene, the fortified town of Margum was probably evoked by the archway at the right, and the soldiers of the emperor Carinus lie in the river.Footnote 48

This identification supplies the key to interpreting the Adventus scene, where the emperor's separately carved head indicates a pre-Constantinian date for the relief (Figs. 6 and 7). Within the Tetrarchic period there are only two occasions that can be considered as possibilities: the North African triumph of Maximian in 299 CE, and the Vicennalia celebration of Diocletian in 303.Footnote 49 The iconography of the scene does not conform to that of a triumph, in that it lacks a chariot, captives, and booty, but it would be appropriate for the kind of celebration that the Vicennalia represented.Footnote 50

There is no way of determining whether the relief originally represented Diocletian or Maximian, both of whom were in attendance, but since the scene is surely part of the same program as the River Battle, which can be tied to Diocletian, then he, as senior emperor, is the more likely choice. The heavily ornamented costume of the emperor beautifully complements the statement of Aurelius Victor that Diocletian's appearance featured a gold and brocaded robe, an abundance of silk, and jewels for sandals.Footnote 51 The Adventus scene therefore likely supplies an illustration of Diocletian's arrival in 303 CE at the inauguration of his Vicennalia celebration.

The final scene representing a procession of the army cannot be conclusively assigned to either Diocletian or Constantine since no emperor is featured (Fig. 18). Its overall composition echoes that of the Adventus relief, especially the archway on the left side, although it could have been carved with such a complementary format in the Constantinian period, just as the Sol and Luna tondi were fashioned to echo those of Hadrianic date that had been spoliated (Figs. 6 and 18).Footnote 52 The images of Victory and Sol Invictus, who appear on the socle reliefs as well, would also be appropriate for either emperor. Victory is at home in any period, and, although Sol Invictus played a prominent role in Constantinian propaganda, he appeared on Diocletianic coinage as well as on the Five-Column Monument in the Forum.Footnote 53 The most important dating criterion in this scene involves the heads of the soldiers, nearly all of whom are shown bearded, unlike those in the Constantinian City Siege relief.Footnote 54 On that basis, then, this relief is more likely to have formed part of a monument to Diocletian than to Constantine.

This overview of the six reliefs from the arch leads to the conclusion that the River Battle and Adventus scenes were spoliated from a monument dedicated to Diocletian. The Oratio and Liberalitas scenes, which also feature missing heads and trimmed lower sections, undoubtedly belong to the same program. At the time when these reliefs were spoliated for inclusion on the new arch, one or possibly two new reliefs were carved, one representing the Siege of Verona and the second showing the marching army.

The sculptors clearly had more difficulty with the frieze than they did with the Trajanic, Hadrianic, and Antonine reliefs. When the latter sculptures were being refashioned for the arch, it was not especially complicated to recut the earlier heads to represent Constantine while maintaining their attachment to the relief surface, since their size was sufficiently large. In the case of the frieze, however, the heads of Diocletian were only 0.15–0.18 m high, and in each case the beard had to be removed, thereby significantly decreasing the lower part of the face and risking the creation of a potentially humiliating imperial portrait. The only practical solution was to remove the earlier heads of Diocletian altogether and carve separate heads of Constantine for insertion, even though there was a danger that they would become disengaged, as they later did. The sculptors faced no such problems with the City Siege, since it was newly carved for the arch, nor with the marching army, since the emperor was omitted altogether.

All of these conclusions are in harmony with the recent examination of the arch by Pensabene and Panella. With reference to the frieze blocks, they note

traces of previous use of the blocks, such as the presence of some rectangular cuttings on the side, on the front, and on the upper surface; an oval cutting is instead present on the front side of the block showing the “Battle of the Milvian Bridge.” At other times, there is a careful finish in areas that could not be seen, such as the upper surface of the block with “Speech from the Rostra,” which has been worked with a fine-tooth chisel. These may constitute traces of a previous use.Footnote 55

Indeed, Pensabene and Panella have demonstrated that all of the blocks used on the arch are spoliated, including those that comprise the dedicatory inscription.Footnote 56 They note that two of the frieze blocks extend beyond the molding and into the zone that contains the tondi, which prompted them to conclude that the frieze was indigenous to the arch despite the evidence of previous use.Footnote 57 But the frieze blocks could just as easily have been configured in the same way on the Diocletianic monument that originally contained the frieze, and then transferred without modification to the Constantinian arch. As I will discuss below, it is not unlikely that the sculptural workshop that carved the frieze was involved in its refashioning for the arch.

Reconstructing a lost monument of Diocletian

For what type of monument were the Diocletianic reliefs produced? Given the size of the reliefs and the patterns of building in Rome during the 3rd and early 4th c., it is difficult to envision anything other than a triumphal arch, which would fit well with the themes of a river battle, an adventus, an oratio, and a liberalitas. Anthropomorphic figural friezes do not appear to have been used on temples in Rome after the Trajanic period (the Temple of Venus Genetrix), although they continue into the fourth century in the provinces (the Temple of Hadrian at Ephesus).Footnote 58 We should also exclude the possibility that the Arch of Constantine began its life as an Arch of Diocletian with these frieze slabs in place. The slabs were clearly carved in situ on another structure and then removed, trimmed, and reworked for the Constantinian arch, as evinced by the Oratio and Liberalitas scenes (Figs. 8–17).Footnote 59

A few more conclusions about the nature of this monument can be proposed. These four reliefs likely belong to a single program that was commissioned shortly after the Vicennalia celebration in 303 CE. Three of the scenes, the Adventus, Oratio, and Liberalitas, would have related to that celebration; the fourth would have showcased the battle that made Diocletian the sole commander of the Roman world and enabled him to devise the Tetrarchy, a system still intact after 20 years, albeit soon to crumble. There is in fact secure evidence for a liberalitas during this Vicennalia. The Calendar of 354 notes that gold and silver were distributed in the Circus Maximus during the course of Diocletian's celebration, which therefore supplies the location of the temporary structure depicted in the Liberalitas relief.Footnote 60 The liberalitas probably occurred shortly after the oratio in front of the newly completed Five-Column Monument, where Diocletian would have stood below his own porphyry statue.

This was not a monument that provided a linear chronological narration of Diocletian's life, but rather one highlighting the qualities and virtues that enabled him to excel as a ruler: prowess in war (the River Battle), supreme command of the army (Adventus), effective communication with the people (Oratio), and generosity (Liberalitas). Such compositions that eschewed linear narratives in favor of concepts of virtue and key biographical episodes had been in operation since the 2nd c., as evinced by the Arch of Trajan at Beneventum, the Ephesian Parthian Monument of Lucius Verus, the “general's sarcophagus” type, and the panels from the Aurelian arch that were reused on the Constantinian arch.Footnote 61

This Diocletianic monument would have continued the same commemorative trend, although, in so doing, it signaled a major shift in frieze design. These small encircling friezes on arches had typically focused on a single time and place, which was the triumphal procession in Rome. As far as we know, the emperor had never before appeared in one of these friezes, being assigned a more commanding position in the attic statuary group or on one of the surrounding monumental reliefs. The designers of the Diocletianic monument made the decision to present in the frieze a kind of res gestae or visual panegyric of the emperor, which would be repeated slightly more than a decade later on the Arch of Constantine.Footnote 62

It is worth noting that this represented the first civil war scene ever included in Roman triumphal commemoration. Augustus had been very shrewd in casting his conflict with Mark Antony as a war with Egypt, while Vespasian and Septimius Severus trumpeted only their foreign victories in Judaea and Parthia, respectively, rather than the Romans whom they battled on the way to the throne. But the strictures against the representation of civil strife had clearly broken down by ca. 300, following nearly a century of such conflicts; and little more than a decade later, on the Arch of Constantine, the conclusion of a civil war would be chronicled in both word and image when Maxentius was labeled a tyrannus in the dedicatory inscription.Footnote 63

The Diocletianic monument would certainly have involved more sculptural components than these four slabs, such as the emperor sacrificing, an adventus of Maximian, and the family of the Persian king Narses, which was reportedly paraded at the Vicennalia.Footnote 64 Images of all four Tetrarchs were probably featured in another part of the monument, as was the case with nearly every Tetrarchic structure that has been unearthed. One can only speculate about the number of scenes of a single emperor vs. Tetrarchic groups, but two monuments of the period give us a sense of the possibilities. The two surviving piers of the Arch of Galerius at Thessaloniki contain 28 panels, 16 of which feature at least one emperor: Galerius appears alone in 13 of them, Diocletian in one, Diocletian and Galerius in one, and all four Tetrarchs in one.Footnote 65 On the Five-Column Monument in the Roman Forum, the Tetrarchs appeared individually on each column base and collectively as adjacent statues above the columns.Footnote 66

The fragmentary state of the other known Tetrarchic monuments prevents us from determining how often and in what combination the emperors were represented there. On the newly discovered marble frieze from Nicomedia, Diocletian and Maximian were shown together at least once, while in other parts of the monument Diocletian appeared with Nike, and Hercules crowned Maximian.Footnote 67 In the cult chamber at Luxor, the four Tetrarchs stand together in the central niche, and one or two of them are shown enthroned in another.Footnote 68 None of the reliefs that has been assigned to Diocletian's Arcus Novus featured an emperor, but whether those panels in fact belonged to the Arcus Novus is still unclear, as is the original format of the arch.Footnote 69

This brief survey demonstrates that there is nothing anomalous about Diocletian appearing alone in the reliefs of this frieze, although narrative scenes involving the other Tetrarchs were undoubtedly included as well. Nor is it surprising that Diocletian appears without Maximian in the Oratio and Liberalitas scenes: although the ceremonial events of 303 that were featured in this frieze marked the tenth anniversary of the Tetrarchy, they also celebrated the Vicennalia of Diocletian alone, so an emphasis on his activities in some of the components of the monument is to be expected. Here too one should consider the decorative program of the Arch of Galerius at Thessaloniki, which was intended to celebrate the emperor's victory against Narses in Persia. During the war he fought alongside Diocletian and Constantine, yet, in all of the battle scenes, Galerius is shown fighting alone. One section of the Thessaloniki arch appears to have included two separate but complementary scenes of clemency: one featuring Galerius, the other Diocletian.Footnote 70

The identification of the frieze's original context means that we now have evidence for at least three commemorative monuments produced in Rome during the reign of Diocletian: the Arcus Novus, the Five-Column Monument, and this one.Footnote 71 The evidence supplied by the frieze from the Arch of Constantine is particularly welcome since very few biographical scenes of Diocletian survive in his monuments. Many of his portraits have been identified and, as a result of the new discoveries in Nicomedia, there are now reliefs of him embracing Maximian and standing with Nike.Footnote 72 But in Rome itself, these friezes provide the only extant examples in which Diocletian's martial and ceremonial activities were featured.

We can only speculate about the history of this “new” Diocletianic monument, which was likely dedicated by the Senate and the Roman People. Since the monument was in part intended to celebrate the events of the Decennalia/Vicennalia, construction would not have begun until after 303: Diocletian would not have been shown presiding over a liberalitas or addressing the people before such events had actually occurred. In light of the fact that the emperor retired to Dalmatia shortly thereafter, and his successor, Maxentius, focused on an extensive building campaign in the Roman Forum, it is conceivable that the monument was never finished.Footnote 73 It is also possible that it was damaged in the fire that destroyed the Temple of Venus and Roma in 307, although the principal damage seems to have been confined to the temple itself.Footnote 74 Either way, the reliefs of the monument were harvested after 312 for Constantine's arch, along with those from monuments of Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius.

The sculptural workshops that executed these reliefs were probably responsible for carving the other new monuments of Diocletian in Rome, and they may also have been charged with reconfiguring the Diocletianic reliefs for the Constantinian arch, since the two activities were separated in time by only a decade.Footnote 75 There is clear support for this hypothesis if one compares the carving techniques of the Diocletianic Five-Column Monument in the Roman Forum with those of the Diocletianic and Constantinian friezes on the Arch of Constantine.

The figure of Victory is present in all three examples: holding the Decennalia shield on the Five-Column Monument (Fig. 19) and flanking the emperor on the arch's City Siege and Adventus scenes (Figs. 2, 4–7). The Adventus is of Diocletianic date; the City Siege, Constantinian. In both cases, the wing's upper section features an imbricated pattern above a series of long parallel strips, although the imbrication is not identical: on the wings of the Adventus Victory, the pattern is much more regular, with the feathers in each row essentially the same size, whereas those on the City Siege's Victory evince much more variation in feather size. Both patterns appear on the wings of the Victories on the Five-Column Monument in the Forum (Fig. 19).

Fig. 19. The Five-Column Monument in the Roman Forum. (Courtesy M. Cohen.)

The Five-Column Monument also features a processional scene with togate men standing in front of soldiers wearing the paludamentum, at least one of whom has incised crow's feet around his eye like the veterans on the arch's Diocletianic Adventus scene (see Fig. 7).Footnote 76 Although the Diocletianic friezes and the Five-Column Monument were designed to be viewed at different heights, the use of drill channels to render the drapery folds, especially on the arms, evinces the same technique.Footnote 77 It seems reasonable to conclude that the same workshops were involved in all three projects. These workshops had probably specialized in sarcophagi during the 3rd c., since such commissions appears to have been the only figural sculpture produced in Rome between the Severan and Tetrarchic periods, other than free-standing portraits and mythological sculpture.

Whether the reconfigured frieze slabs occupied the same sequence on the Constantinian arch as they had on the Diocletianic monument is unclear. The four panels that comprise the Great Trajanic Frieze were reordered on the arch, as were the Hadrianic tondi, so the same could have been true for all of the spoliated sculpture.Footnote 78 What is clear, however, is the ease with which the subjects of the reliefs could be reconfigured to honor Constantine. The Vicennalia of Diocletian in 303 CE involved an adventus, an oratio, and a liberalitas; the Decennalia of Constantine in 315, which his arch celebrated, would have entailed the same three acts, so the Diocletianic reliefs could be redefined with only a change of portraits.Footnote 79 The River Battle was an equally straightforward transfer since both Diocletian and Constantine had fought a civil war at a river.Footnote 80 The Margus could quickly become the Tiber in the relief's new position next to the City Siege of Verona, which was an actual Constantinian battle. In other words, Diocletian could become Constantine with relatively little effort, and the visual record of Diocletian's Vicennalia was consequently transformed into that of Constantine's Decennalia.Footnote 81

The conversion of the Diocletianic frieze and the Aurelian reliefs was more straightforward than those involving the Trajanic and Hadrianic components. When the heads of Trajan in the Great Frieze were recut to those of Constantine, the new emperor was projected onto the Dacian battleground even though he had never witnessed armed conflict there, while the recutting of Hadrian to Constantine transformed the latter into an avid hunter, an avocation for which there is no evidence in the sources. Nevertheless, few would have focused on the incongruity of Constantine fighting in Dacia, even if they were able to interpret the costumes as Dacian. The goal was to highlight the emperor's invincibility on the field of battle or in the hunt, and it was effectively realized in the new compositional matrix.

Spolia reconsidered: Constantine and the earlier emperors

The interpretation proposed above would mean that the arch's spoliated elements were pulled from monuments of Diocletian as well as Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius, so four emperors rather than three. This, in turn, leads us to consider the long-standing argument that the arch was intended to present Constantine as the embodiment of the virtues of “good” 2nd-c. emperors, as most have assumed since the arch's publication by L'Orange and von Gerkan in 1939. Several cogent criticisms of this argument have been advanced in the past, primarily by Dale Kinney and Paolo Liverani, but it nevertheless remains in force in nearly every textbook on Roman art, so I revisit the issue here in light of the new interpretation of the frieze.Footnote 82

The incorporation of Diocletian into this group does not invalidate such an interpretation, at least on the surface, since Diocletian established the political framework that enabled both Constantine and his father to rise to leadership positions in the empire. The real question is whether 4th-c. spectators would have possessed the visual knowledge to link the spoliated sculptures with specific emperors of the past, and then to mentally reconfigure that knowledge into a political program that was applicable to Constantine.Footnote 83 The answer to this question is crucial to understanding how the sculptural ensemble was perceived in antiquity, and it requires a brief review of the original context of the reused sculptures.

The most easily identifiable components may have been the eight Dacians in the attic zone (Fig. 1), since an identical circuit of such statues was still standing in the Forum of Trajan. Whether the statues on the arch would have been read as Dacians by everyone, however, is questionable. The pedestal reliefs, at eye level, featured captive Gauls, Germans, and Persians flanked by Victories.Footnote 84 The heads of the Dacians, at a height of 18 m, would not have been as easily seen, and, in their new context, they may have been interpreted as images of additional Gauls or Germans, with whom Constantine had actually been engaged in armed conflict. In other words, the new context would have conferred upon them a meaning that was relevant to the career of the new emperor, like the River Battle scene in the frieze.

The panels belonging to the Great Trajanic Frieze are a different matter altogether (Fig. 1). They represent scenes from the Dacian Wars in which Trajan appears twice: once on horseback before prostrate Dacians, and again flanked by Roma/Virtus and Victory, who crowns him. All four panels originally joined and comprised one side of a monument that was over 18 m long.Footnote 85 The most striking feature of the reliefs is their height of 2.98 m. This is far too high for the frieze of a building or the podium of a temple, and even larger than the reliefs that adorned monumental altars and cenotaph podia in Asia Minor and Rome. The closest comparanda are the Pergamon Altar Gigantomachy (2.74 m), the Cenotaph of Gaius Caesar in Limyra (2.08 m), the Cancelleria reliefs (2.06 m), and the Parthian Monument of Lucius Verus in Ephesus (2.05 m).Footnote 86 Such monumental altars are unknown in Rome or anywhere in Italy after the Flavian period, and temples or cenotaphs with sculpted podia are limited, as far as we know, to Asia Minor. It is therefore conceivable, as Ross Holloway has argued, that the Great Trajanic Frieze was taken from a monument originally erected some distance from the capital city, which would mean that very few in Rome would have seen it before. Consequently, most viewers would have been unaware of its connection with Trajan, especially after the heads were recut to portray Constantine.Footnote 87

Equally problematic are the tondi, c. 2.40 m in diameter, of which eight can be dated stylistically to the Hadrianic period (see Figs. 1, 4, 8, 12).Footnote 88 Four focus on hunts involving a bear, boar, and lion, while the other four depict post-hunt sacrifices to a different deity: Silvanus, Diana, Apollo, and Hercules, who holds a statuette of Victory. Some of the heads of Hadrian have been recut to Constantine and Licinius or Constantius Chlorus, and, although there is general agreement that Antinous was represented, his name has been attached to different figures on the reliefs.

The most unusual feature is the hunting iconography, which is otherwise absent in monuments of Roman emperors. Hunting scenes were never incorporated into monuments glorifying Augustus, Trajan, Marcus Aurelius, or Septimius Severus, for example, either in Rome or in the provinces.Footnote 89 The general confinement of such subjects to tomb decoration has led some scholars to propose that the tondi formed part of a tomb complex to Antinous on the Palatine, erected in his memory by Hadrian after 130 CE.Footnote 90 This attribution can probably never be proven, but it is far from certain that 4th-c. viewers would have known to link the tondi to Hadrian, and many would undoubtedly have been struck by the appearance of hunting iconography on a triumphal arch.

The Aurelian reliefs feature the same size, shape, and narrative style as three others in the Capitoline Museums, although whether they derive from one or two arches of Marcus Aurelius is disputed (Fig. 1).Footnote 91 Some of the panels clearly celebrate his triumph over the Germans and Sarmatians, and at least two of them – a liberalitas and a triumphal procession – originally included his son Commodus. It is difficult to believe that an Aurelian arch in stable condition would have been dismantled for the Constantinian arch, so we should probably assume that it was damaged in the course of that century. In any event, there is no way of determining whether the Aurelian reliefs would have been recognized as such in the 4th c., and the same is true for the Diocletianic frieze, since it probably belonged to a monument that was never finished.

This survey suggests that the original contexts of the Dacian statues and perhaps the Aurelian reliefs might have been discernible, but those of the tondi, the Great Trajanic Frieze, and the Diocletianic monument may not have been. We also tend to forget that the new configuration of these elements in an equally new architectural framework would have provided them with different layers of meaning that may have diverged substantially from the original intention. The surfeit of new colors that now surrounded them, such as the giallo antico columns, the porphyry bands, and the attic's gilded bronze quadriga in the shadow of the adjacent solar colossus would have contributed to this shift in perception, which the recutting of the heads to Constantine would have reinforced.Footnote 92

There is also no reason to expect that ancient viewers would have been able to distinguish among Trajanic, Hadrianic, and Antonine styles; even modern scholars failed to recognize the roundels as Hadrianic until 1919.Footnote 93 Nor is there reason to assume that viewers would have engaged in a process of guessing the names of the emperors in whose honor the various reliefs had been produced, with the goal of determining whether they formed part of a carefully formulated program designed to celebrate Constantine.Footnote 94

The Tetrarchic emperors focused on the present, not the past, a viewpoint that one can see reflected in contemporary panegyric in which 2nd-c. emperors are hardly mentioned.Footnote 95 I strongly suspect that the most accurate appraisal of the later life of these sculptures has been offered by Dale Kinney, who noted that “recutting literally effaced their original referents.”Footnote 96 There is every reason to believe that the reused sculptures were selected because they were readily available, perhaps because their associated monuments had fallen into a state of disrepair and their sculptural components were warehoused, as in the case of the Cancelleria reliefs.Footnote 97

There does appear to have been some attempt to coordinate the types of scenes on a vertical axis, however.Footnote 98 The Liberalitas on the frieze was inserted below the Aurelian relief in which the emperor engaged in the same activity (Fig. 1); the sacrifices of Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius on the south side are aligned; and the juxtaposition of the frieze's imperial Adventus with the tondo of the ascending Sol was probably intended to foster a link between the two, which the solar colossus nearby would have echoed (Fig. 6). But the adlocutio/oratio scenes of Marcus Aurelius and Diocletian/Constantine occupied different sides, as did the Trajanic and Diocletianic/Constantinian battle scenes.

Historiography reconsidered

The idea that the arch represented a diagram linking Constantine to the best of the 2nd-c. emperors was first advanced by L'Orange and von Gerkan in their 1939 volume on the arch, and it is worthwhile, in closing, to consider whether their promotion of this thesis might have been influenced by contemporary events. Both authors were living and working in Rome in the 1930s, when von Gerkan served as director of the German Archaeological Institute. This was a period in which Mussolini sought to formulate links between ancient and Fascist Rome in the visual arts at every opportunity, including in the Piazza Augusto Imperatore, the Foro Italico, and the Esposizione Universale Roma.Footnote 99 The culmination of this political program was the 1937 celebration of the bimillenary of Augustus’ birth, during which Mussolini effectively presented himself as a second Augustus while the resurrected Ara Pacis was being unveiled. The reliefs of the Constantinian arch were cast for that celebration and, in their monograph, L'Orange and von Gerkan refer to Hitler's visit to the arch several months later during a summit in Rome with Mussolini.Footnote 100

When the “good 2nd-c. emperors” idea is viewed through such an historiographic lens, one is tempted to conclude that the Fascist focus on an interwoven past and present during the 1930s provided a paradigm that L'Orange and von Gerkan transferred to their interpretation of the arch. The analytical model they offered has proven influential in subsequent inquiries into the conceptual foundations of Late Roman monuments, and it continues to be popular. When Hans Peter Laubscher published the Arcus Novus in 1976, he proposed that Diocletian had spoliated the reliefs from the Britannic Arch of Claudius in order to highlight the recent Tetrarchic victories in Britain. Whether the spoliated reliefs actually came from the earlier arch and represented a programmatic link between Claudius and Constantius Chlorus is unknown, but the influence of the model proposed by L'Orange and von Gerkan is readily apparent.Footnote 101

It is probably the allure of the “good 2nd-c. emperors” model that explains why scholars have been disinclined to engage with the issue of the separately worked heads in the Constantinian frieze: if the spoliation of the frieze were to be acknowledged, it would disrupt the proposed program of the arch that has been anchored in place since 1939. But there is nothing surprising about the proposition that an arch with so many spolia and reworked portraits would contain a largely spoliated frieze with reworked portraits.

Such a realization demonstrates that the biography of the arch is much richer than we have recognized, in that Diocletianic imagery was pulled into the matrix along with spoliated reliefs of Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius, all of which became part of a completely new monument celebrating Constantine's Decennalia. It is also conceivable that even more elements on the arch have been spoliated: 30 years ago Sandra Knudsen proposed that the pedestal reliefs had been spoliated from a Tetrarchic monument, and that may be true as well of some of the rectangular reliefs in the side niches that feature busts with separately carved heads.Footnote 102

In any event, the ease with which the Diocletianic frieze was transformed into a narrative of Constantine's life demonstrates the striking elasticity of Late Antique imagery, wherein one man's Vicennalia could become another's Decennalia with only a change of portraits. Even though the sculptors who adapted the frieze left a series of telltale clues regarding its former use, primarily the separately worked heads and the missing legs and feet, no one viewing the scenes from ground level would have been aware of the discrepancies, and that remains true today. Assessing the arch as the pastiche that it was and moving beyond the proposition that only the “good 2nd-c. emperors” were co-opted and refashioned will, I hope, promote greater scrutiny of all of its parts, thereby demonstrating that the arch certainly does signal new directions in triumphal commemoration, but not quite in the way we thought it did.

Acknowledgments

For assistance during the preparation of this article, I am grateful to Ann Kuttner, Robert Ousterhout, Lynne Lancaster, Dale Kinney, Ivan Drpić, Daira Nocera, Meg Andrews, Michele Salzman, James Packer, Deb Brown Stewart, Rebecca Stuhr, Braden Cordivari, Justin Ross Muchnick, Steven Rosen, and Nadine Frey. The comments of the two anonymous reviewers were also extremely helpful. For photographs, I acknowledge the assistance of Sebastian Hierl, Lynne Lancaster, and Lavinia Ciuffa (American Academy in Rome), Ortwin Dally and Daria Lanzuolo (DAI, Rome), and Jeff Bondono.