INTRODUCTION

The willingness of athletes to speak publicly about their political beliefs, high levels of sports fan interest, the omnipresence of sport in mainstream, online, and social media, and the polarizing dynamics of the racialization and politicization of sports and society topics have brought sports-related social issues to the forefront of national conversations in recent years (Dyck et al., Reference Dyck, Cluverius and Gerson2019; Thorson and Serazio, Reference Thorson and Serazio2018). For instance, beginning in 2016, attention focused on National Football League (NFL) players kneeling during the playing of the national anthem to protest police violence in Black communities; these protests were led by San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick. Also, college athletes have been increasingly vocal about their economic exploitation, lack of power to negotiate their terms of play, receipt of false promises about quality education, and the neglect of their health and safety; disproportionately, athletes in the most high-profile and commercialized sports are Black and many of them have remarked on these issues (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Meyer and Zimbalist, Reference Meyer and Zimbalist2020).

What often seem to be apolitical sports-related issues have become cultural touchstones that symbolize and bring to light racialized and politicized experiences and worldviews (Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Knoester et al., Reference Knoester, Ridpath and Allison2021; Thorson and Serazio, Reference Thorson and Serazio2018). That is, mirroring racial/ethnic and political divides in public sentiment on a range of social issues, substantial racial/ethnic and political partisanship gaps have become apparent in public opinions about current events in sports (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Howat and Rodheim2016; Intravia et al., Reference Intravia, Piquero, Piquero and Byers2020; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020). In large part, these racial/ethnic differences seem to be a function of distinct levels of perceived racial/ethnic groupness, or “linked fate,” as well as disparate recognition of racial/ethnic inequalities and commitments to social change among especially Black and White adults (Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Kam and Burge, Reference Kam and Burge2019; Montez de Oca and Suh, Reference Montez de Oca and Suh2020). Political elites have contributed to the racialization and politicization of sports issues in efforts to activate, build, or preserve political coalitions, as well as to create or ward off changes to the status quo (Agiesta Reference Agiesta2017; Bivens Reference Bivens2017; Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Howat and Rodheim2016; Intravia et al., Reference Intravia, Piquero and Piquero2018; Weems and Singer, Reference Weems Anthony, Singer, Thompson-Miller and Ducey2017). Yet beyond merely reflecting existing patterns of political polarization, sport is also a uniquely powerful racialized and politicized social setting that is particularly meaningful to the many who play or follow. Still, it is characterized by the simultaneous salience of and disavowal of race and politics (Hartmann Reference Hartmann2016; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Knoester et al., Reference Knoester, Ridpath and Allison2021).

Despite the popular mythology that situates sport in the less “serious” realm of entertainment, sport is a fundamentally social and political institution, a site where systems of racial/ethnic and political meaning, interaction, and social organization are understood, constructed, and challenged, and where events are frequently understood through the lenses of race/ethnicity and politics—even if they appear to be race-neutral or apolitical (Carrington Reference Carrington2013; Edwards Reference Edwards2017; Hartmann Reference Hartmann2000; Thorson and Serazio, Reference Thorson and Serazio2018). The co-opting of the racialization and politicization of sports has become particularly common and apparently strategic since the election of Donald Trump in November of 2016, and a great deal of research has focused on these recent dynamics (Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Montez de Oca and Suh, Reference Montez de Oca and Suh2020; Park et al., Reference Park, Park and Billings2020). Yet less attention has been paid to the racialization and politicization of sports and their links to public opinions just prior to Trump’s election. Therefore, we seek to complement extant research by focusing on public opinions about paying college athletes and athletes protesting during the national anthem just prior to Trump’s election with unique nationally representative data from October 2016.

The study of public opinion about these and other sports-related issues is important, as public opinion can affect policies and practices within sport organizations. Public opinion also symbolizes individual and cultural values and can offer knowledge about the framing and negotiation of important issues. In fact, sports-related public opinions may be especially revealing because individuals seem to be at least partly unaware of the broader implications of their attitudes about sports (Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Knoester et al., Reference Knoester, Ridpath and Allison2021; Mondello et al., Reference Mondello, Piquero, Piquero, Gertz and Bratton2013; Wallsten et al., Reference Wallsten, Nteta, McCarthy and Tarsi2017). Nonetheless, research on race and public opinions about sports-related issues is underdeveloped. Most research has isolated issues to study them, focused only on White and Black respondents, rarely used representative data, and offered little account for how and why race/ethnicity and political identities matter for sports-related public opinions. In fact, public opinion research frequently addresses overall patterns of public attitudes over “the dynamics behind attitude expression” (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Gilli, Klar and Robison2014, p. 2), and public opinion poll results typically report only descriptive statistics (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Howat and Rodheim2016; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Knoester et al., Reference Knoester, Ridpath and Allison2021; Wallsten et al., Reference Wallsten, Nteta, McCarthy and Tarsi2017).

Specifically, the goals of the present study are to describe and use multiple regression analyses to predict public opinions about college athlete financial compensation and the acceptability of athletes protesting during the playing of the national anthem among a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults surveyed in October of 2016. We draw from Critical Race Theory and framing theory to contend that racialized experiences in America and similar dual public framings of these issues make racial/ethnic identities, racial attitudes, and political identities particularly salient in predicting these public opinions (Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Knoester et al., Reference Knoester, Ridpath and Allison2021; Montez de Oca and Suh, Reference Montez de Oca and Suh2020). Consequently, we focus on the extent to which novel indicators of racial/ethnic identities (i.e, White, Black, Latinx, Asian American, American Indian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and multiracial identities), racial attitudes (i.e., beliefs about contemporary issues involving racial/ethnic inequalities in education and the priorities of the Black Lives Matter movement), and political identities (i.e., self-reported conservatism and 2016 voting intentions) predict opinions towards these sports-related issues that have been positioned as both racialized and race-neutral, politicized and apolitical, within public discourse.

The issues that we study share several features that make their simultaneous inclusion in this analysis appropriate: (1) both are recent issues that have received substantial media and public attention and on which public opinion is and has been divided, including by race/ethnicity and political identities; (2) both reference high-profile, revenue generating men’s college and professional sports, particularly football; and (3) both are related to the joint production of racial/ethnic and economic inequalities, contestations over control of Black men’s (laboring) bodies and the value(s) that they represent (Benson Reference Benson2017; Serazio and Thorson, Reference Serazio and Thorson2019; Weems and Singer, Reference Weems Anthony, Singer, Thompson-Miller and Ducey2017). Both issues have been discussed in race-neutral and presumptively apolitical terms within what Joe Feagin (Reference Feagin2020) describes as a White racial frame that denies the existence of racism, but elevates the virtuousness of White people, considers people of color to be outsiders, and remains preoccupied by Black Americans and antiblack sentiments. Also, both issues have been critically analyzed from an antiracist perspective within a counter frame advanced by people of color and their allies (Feagin Reference Feagin2020; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Montez de Oca and Suh, Reference Montez de Oca and Suh2020). These highly divergent framings—how they invoke race/ethnicity and political identities, and how these framings align with existing racialized and politicized polarizations—illustrate how race/ethnicity and politics are endemic to understandings of society, even when the issues are seemingly isolated within the world of sports.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

We consider public opinions about college athlete financial compensation and athlete protests during the national anthem through the lenses of Critical Race Theory (CRT) and framing theory. The underlying premise of CRT is that society is characterized by individual and structural racism and that these shape life chances, social interactions, and worldviews in ways that generate and reify racial/ethnic inequalities (Carrington Reference Carrington2013; Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Hylton Reference Hylton2008). The specific tenets of CRT that inform this study include: (1) recognizing the permanence and pervasiveness of racism, (2) challenging dominant ideologies, (3) offering and highlighting counter narratives and experiential knowledge, (4) recognizing Whiteness as property norm, and (5) committing to social justice efforts (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Delgado Bernal Reference Delgado Bernal2002; Hylton Reference Hylton2008).

Sport is a prominent part of culture that is often perceived to be meritocratic, a view supported within framing efforts that advance White interests while divorcing sport from its sociohistorical contexts, including its associations with White heteromasculinity, power, and privilege (Feagin Reference Feagin2020; Hartmann Reference Hartmann2016; Weems and Singer, Reference Weems Anthony, Singer, Thompson-Miller and Ducey2017). Some point to the numeric overrepresentation of Black athletes in college and professional basketball and football as evidence of a meritocracy, perceiving that patterns of racial/ethnic representation demonstrate that sport is an avenue of upward mobility for talented Black athletes who work hard (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Hartmann Reference Hartmann2000; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020).

CRT tenets urge contestations of the myth of meritocracy in sport (and society) and help identify how this myth both draws from and strengthens stereotypes of Black athletes as ubiquitously poor and intellectually deficient, yet athletically superior to Whites (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Edwards Reference Edwards2017; Hartmann Reference Hartmann2000; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020). Also, the myth of meritocracy in sport and the overwhelming associations between sport and particularly capitalist but also other American values (e.g., patriotism, respect for the military, an understanding of a national identity) that are nurtured and presented in commercialized sport productions have encouraged backlash and resistance to expressions of dissent by Black athletes during sporting events. Myths of meritocracy have led many people to feel that athletes should be grateful for their status, privileges, and rewards, and should not agitate for more. Yet CRT insights identify the original and continual dynamics of White Racism Capitalism, other forms of exploitation, and racial/ethnic inequalities, prejudices, and discrimination in sports and society. Thus, CRT principles encourage contestations of color-blind ideologies that disavow racism and advance raceless explanations for continuing patterns of racial/ethnic injustice in sport and in society (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2006; Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Hylton Reference Hylton2008; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Knoester et al., Reference Knoester, Ridpath and Allison2021; Singer Reference Singer2005).

Applied to questions of public opinion, a CRT lens sees the formation and expression of public sentiment as “processes of power” (Hylton Reference Hylton2008, p. 13) that are part of the complex construction and negotiation of race/ethnicity and racial/ethnic inequalities. Public opinions about paying college athletes and the acceptability of athlete protests during the national anthem are expected to be prominent, recent indicators of how racial/ethnic identities, attitudes, and inequalities are present, contested, and influential in sports and society. The cultural terrain of sports allows for public opinions about these and other issues to be produced and negotiated; racial/ethnic identities, attitudes, and inequalities are instrumental in these productions and negotiations (Chaplin and Montez de Oca, Reference Chaplin and de Oca2019; Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Gilli, Klar and Robison2014; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Montez de Oca and Suh, Reference Montez de Oca and Suh2020; Wallsten et al., Reference Wallsten, Nteta, McCarthy and Tarsi2017).

In addition, we draw on framing theory to understand how the formation of public opinion is a function of the relative importance that individuals give to an issue and their beliefs about the salient aspects of the issue. Dennis Chong and James N. Druckman (Reference Chong and Druckman2007) argue that framing “refers to the process by which people develop a particular conceptualization of an issue or reorient their thinking about an issue” (p. 104). Individual “frames of thought” reflect both existing belief systems but also the “frames of communication” (p. 106) that are part of concerted efforts at influence on the part of politicians, organizations, and mass media, among others (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Howat and Rodheim2016; Dyck et al., Reference Dyck, Cluverius and Gerson2019). Through framing, “aspects of reality are selected or excluded, emphasized or overlooked, and discussed” (Park et al., Reference Park, Park and Billings2020, p. 631).

Individuals are often exposed to multiple, competing frames on a single issue. How they choose which frames to pay attention to shapes important social and political behaviors such as conversations with others, engagement in and support for activism, voting decisions, and financial commitments (Chong and Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007). In selecting frames, individuals rely in part on elite cues. Given acute political polarization, political elites are particularly potent messengers, framing issues that were not previously politicized in partisan terms. Joshua J. Dyck and colleagues (Reference Dyck, Cluverius and Gerson2019) argue that individuals craft opinions through “motivated reasoning,” where they receive the cues of elites who share their political identity and then interpret new information through this lens. Thus, political identities are frequently associated with patterns of public opinion (Cramer Reference Cramer2020). Frame adoption also depends on individuals’ existing value commitments and the strength of available frames. Issue-specific frames are stronger and more resonant when they link to other, broader cultural frames or appeal to widely held values, beliefs, or ideologies (Winter Reference Winter2008). Thus, beyond party affiliation, ideological principles like equality or limited government that align with but are also partially distinct from political party platforms can also shape opinion (Kinder and Winter, Reference Kinder and Winter2001).

Frames are not race-neutral. Certainly, some issues are explicitly about race/ethnicity and their frames, too, call direct attention to race/ethnicity (Intravia et al., Reference Intravia, Piquero and Piquero2018, Reference Intravia, Piquero, Piquero and Byers2020; Kinder and Winter, Reference Kinder and Winter2001). However, race/ethnicity is often an implicit component of the framing of issues that are not explicitly about race/ethnicity. Frames often subtly associate an issue with a particular racial/ethnic group or principle relevant to race/ethnicity such as equality, for instance through the use of racialized “code words” or imagery (Bobo and Johnson, Reference Bobo and Johnson2004; White Reference White2007; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Owens and Davis2015). Nicholas Winter’s (Reference Winter2008) theory of group implication, or “the process through which ideas about social groups—specifically, race/ethnicity and gender—can be applied to political issues that do not involve either directly” (p. 19), holds that as powerful cognitive schemas that we learn and use both consciously and unconsciously, race/ethnicity may be brought into frames of issues through analogy or metaphor, where the structure and content of a schema match those within a frame. As Winter (Reference Winter2008) explains, U.S. racial/ethnic schema divide the world into in- and out-groups which are different and unequal and whose relationships are characterized by hostility. Racial/ethnic schema also frequently contain an evaluation of supposed “truths,” for instance by attributing racial/ethnic inequality to individual merit, versus social structural barriers. As a consequence of group implication, framing commonly activates existing racial attitudes. Substantial research has shown that racial/ethnic prejudice is a determinant of public opinion across both race-neutral and overtly racialized policy issues (Cramer Reference Cramer2020; Kam and Burge, Reference Kam and Burge2019). In fact, empirical relationships between racial/ethnic prejudice and public opinion have grown stronger over the past three decades (Enders and Scott, Reference Enders and Scott2019).

Feagin (Reference Feagin2020) argues that dominant issue frames are White racial frames, the term referring to “…an overarching White worldview that encompasses a broad and persisting set of racial stereotypes, prejudices, ideologies, image interpretations and narratives, emotions, and reactions to language accents, as well as racialized inclinations to discriminate” (p. 11). By minimizing or denying racism and White privilege while also embodying stereotypes and racist ideologies, the White racial frame both legitimates and perpetuates racial inequality. The contrast to the White racial frame is a counter frame, typically asserted by people of color, that exposes the Whiteness of dominant frames and the operations of racism and calls for antiracist action.

The two issues in sport that we address—the financial compensation of college athletes and athlete protests during the national anthem—have been publicly framed in similarly divergent ways. One set of framings reflects a White racial frame wherein racial/ethnic inequalities are ignored and perpetuated. Instead of recognizing the prominence and pervasiveness of racism, these framings neglect racial/ethnic inequalities. These framings emphasize supposedly race-neutral ideas such as the value of amateurism or traditional sporting rituals that sacralize nationalism like the playing of the national anthem or presentation of the flag. Additionally, these framings ignore the experiential knowledge that stems from Black perspectives. Instead, Whiteness is assumed to be normative and symbolic of wisdom and control (Weems and Singer, Reference Weems Anthony, Singer, Thompson-Miller and Ducey2017). These framings do not seek social justice. Instead, they are concerned with maintaining tradition, order, and the status quo and consider disruptions to these to be “political” (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Chaplin and Montez de Oca, Reference Montez de Oca and Suh2020; Kusz Reference Kusz2007; Serazio and Thorson, Reference Serazio and Thorson2019; Wallsten et al., Reference Wallsten, Nteta, McCarthy and Tarsi2017).

In contrast, counter frames of these two issues align with a CRT and antiracist perspective that centers individual and systemic racism. These counter frames support challenging dominant ideologies that are used to produce and justify racial inequalities such as myths of amateurism and sacred sports nationalism. They highlight the experiential knowledge of Black athletes and their allies who speak out against economic exploitation in college sports and criminal justice inequalities. These framings show that a Whiteness as property norm allows and normalizes the exploitation of Black labor to the advantage of White men in the most commercialized college and professional sports (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Weems and Singer, Reference Weems Anthony, Singer, Thompson-Miller and Ducey2017). Finally, a CRT and antiracist perspective recognizes college athlete compensation and athlete protests during the national anthem as social justice issues, supporting efforts to reduce racial/ethnic inequalities (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Delgado Bernal Reference Delgado Bernal2002; Kendi Reference Kendi2016).

BACKGROUND, DOMINANT FRAMES, AND PUBLIC OPINION

College Athlete Financial Compensation

The remuneration of college athletes playing at National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) schools has received intense scrutiny for years. Several states and the U.S. Congress continue to consider legislative proposals that would see athletes receive expanded legal rights to financial compensation beyond the value of athletic scholarships for their participation in varsity sports. The NCAA itself is also considering change and some states have already passed laws that will grant athletes more economic rights, with Florida’s law set to be the first to take effect in 2021 (Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Meyer and Zimbalist, Reference Meyer and Zimbalist2020).

Historically, the NCAA called athletes “student-athletes” and “amateurs,” terms invented to avoid the suggestion that these were employees who could earn direct payments or file for worker’s compensation benefits (Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Meyer and Zimbalist, Reference Meyer and Zimbalist2020; Schneider Reference Schneider2001). Financial compensation outside of the athletic scholarships available at Divisions I and II programs was associated with professionalization and argued to be unethical, the value of scholarships deemed equitable reward for athletic labor. The NCAA holds that denying athletes direct payments protects them from exploitation and preserves college sports from the forces of commercialism. However, this argument has become increasingly difficult to square with evidence of rampant commercialism, skyrocketing coaches’ salaries, enormous facilities upgrade costs, and growing revenue from television contracts and bowl payouts—particularly in Division I men’s football and basketball (Bivens Reference Bivens2017; Meyer and Zimbalist, Reference Meyer and Zimbalist2020).

In the face of intensified recent criticism, including on the part of college athletes, the NCAA and athletics administrators have supported reforms, such as the expansion of scholarships to cover the full cost of attendance in 2015. However, there have been few expressions of support for more widespread changes that would shift the balance of power and resources (Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Mondello et al., Reference Mondello, Piquero, Piquero, Gertz and Bratton2013). Most recently, debates have centered on name, image, and likeness (NIL) rights, with California passing the Fair Play to Pay Act in 2019 allowing athletes payment from endorsements and the right to hire agents. Following this act, the NCAA has considered its adoption nationwide and NCAA President Mark Emmert has shifted towards limited support for opening opportunities for college athletes to receive financial compensation (Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Meyer and Zimbalist, Reference Meyer and Zimbalist2020).

Criticisms of the NCAA and its “collegiate model” have acted as an antiracist counter framing of college athletes’ economic position. These critiques recognize that Black men are vastly overrepresented as players in college basketball and football relative to their numbers in the population and within student bodies. These two sports generate substantial revenue that disproportionately flows to the White men who predominate in coaching, administration, and NCAA leadership positions but not directly to the players who generate it (Benson Reference Benson2017; Hawkins Reference Hawkins2013). This is a racialized form of exploitation where the value of young Black men’s athletic labor is appropriated by White men in positions of power, consistent with racist capitalist practices that have been in place for 400 years (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Wallsten et al., Reference Wallsten, Nteta, McCarthy and Tarsi2017). From this perspective, the current transactional relationship between athletes and the NCAA is inequitable given restrictions on earnings for athletes that are not in place for coaches or other students, as well as the lower quality education that athletes in revenue-generating sports often receive compared to non-athlete students (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Howat and Rodheim2016).

In contrast, defenses of college athletes’ economic position reflect a White racial frame that neglects and perpetuates racial/ethnic inequalities. The NCAA and athletics administrators have been the most public and vocal supporters of a framing that justifies the “collegiate model” with reference to the educational value of athletic scholarships. In this framing, athletics programs further the educational missions of colleges and universities. Students must be amateurs (i.e., without direct financial compensation) so they are not exploited by commercial forces and their “product” remains untainted by commercialism (Meyer and Zimbalist, Reference Meyer and Zimbalist2020; Schneider Reference Schneider2001). Athletes do reap financial benefits of sports participation indirectly through their athletics scholarships; a cost-free education is “payment” for their labor (Mondello et al., Reference Mondello, Piquero, Piquero, Gertz and Bratton2013). While this framing is purportedly race-neutral, it is implicitly racialized in the suggestions that amateurism is a shared ideal—when, in fact, it was created by White individuals with privileged, White athletes in mind (Hruby Reference Hruby2016; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020)—and that many athletes in revenue-generating sports receive educational opportunities through athletic scholarships that they would be unlikely to have otherwise. Here, the unspoken assumption is that all Black men are from socioeconomically disadvantaged families and underperforming school systems that result in academic deficiencies. Black men are assumed to be under-prepared for college-level coursework, leaving college admission via athletic prowess their only option (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Hawkins Reference Hawkins2013).

Although most public opinion polling indicates resistance to paying college athletes, there appears to be growing public support for financial compensation beyond athletic scholarships in recent years (Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Schneider Reference Schneider2001). Michael Mondello and colleagues’ (Reference Mondello, Piquero, Piquero, Gertz and Bratton2013) national survey found that two-thirds did not support financial compensation for college athletes. Then, a Washington Post-ABC News poll in 2014 found that 64% of respondents opposed paying salaries to college athletes beyond athletic scholarships (Prewitt Reference Prewitt2014). Chris Knoester and B. David Ridpath’s (Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020) analysis of 2018–2019 national data found that 48% of respondents agreed that college athletes should be allowed to be paid, while only 44% disagreed. Finally, by October 2019, a Seton Hall poll found that 60% of U.S. adults endorsed allowing student athletes to profit from the use of their name, likeness, or image (Seton Hall Sports Poll 2019).

Protests During the National Anthem

In August 2016, National Football League quarterback Colin Kaepernick sat and then kneeled during the playing of the national anthem to protest police violence in Black communities (Park et al., Reference Park, Park and Billings2020). Black athletes have continually expressed dissent during the national anthem to highlight disconnects between meritocratic rhetoric and the realities of racism for people of color in the United States. However, the substantial attention that Kaepernick received for his actions often neglected to provide this historical context (Chaplin and Montez de Oca, Reference Montez de Oca and Suh2020; Edwards Reference Edwards2017; Smith and Tryce, Reference Smith and Tryce2019). In 2016 and 2017, players in the NFL, the Women’s National Basketball Association, women’s professional soccer, and other leagues followed Kaepernick’s lead. Many of these protests engendered backlash, with White fans and pundits, NFL executives, and even the U.S. President being foremost among the critics (Benson Reference Benson2017; Intravia et al., Reference Intravia, Piquero, Piquero and Byers2020; Montez de Oca and Suh, Reference Montez de Oca and Suh2020; Park et al., Reference Park, Park and Billings2020; Serazio and Thorson, Reference Serazio and Thorson2019).

The two primary framings of these athlete protests represented a White racial frame and counter frame (Kendi Reference Kendi2016; Montez de Oca and Suh, Reference Montez de Oca and Suh2020; Sevi et al., Reference Sevi, Altman, Ford and Shook2019). The antiracist counter framing of Kaepernick and others’ protests draws direct attention to racial/ethnic inequalities by emphasizing the concerns about police brutality and broader racial/ethnic inequalities that motivated the protests. Understood within the history of athletes who have used sport as a platform to call attention to inequality, a desire to improve the nation by addressing its fundamental social problems is the very embodiment of patriotism.

However, a White racial frame has been the predominant frame of this issue in mainstream mass media. This frame neglects or ignores the existence of racial/ethnic inequalities such as those found in violent police actions and embraces patriotism as an unquestioning adherence to the social norms and traditions that surround the rituals of celebrating nationalism in sports. From this perspective, to disrupt the playing of the national anthem is to disrespect the flag, the nation, and especially members of the military (Kendi Reference Kendi2016; Kusz Reference Kusz2007; Park et al., Reference Park, Park and Billings2020).

National polling data show that public opinion towards anthem kneeling protests has been highly divided, although it grew slightly more approving from 2016 to 2017. For instance, a Quinnipiac University poll from October 2016, two months after Kaepernick’s protest began, found that 54% of adults disapproved of athlete kneeling protests, while 38% approved (Quinnipiac University 2016). Similarly, an HBO/Marist poll from September 2016 found that 52% of respondents reported that yes, professional sports leagues should require athletes to stand during the national anthem, while 43% said they should not. By October 2017, 51% of U.S. adults said that professional sports leagues should not require athletes to stand during the anthem (Marist Poll 2017). A CNN poll conducted in September 2017 found that 43% of respondents felt that athletes who protested during the national anthem were doing the right thing and 49% felt they were doing the wrong thing (Agiesta Reference Agiesta2017). Forty-six percent of respondents said that these protests were “disrespectful to the freedoms the anthem represents,” down slightly from the 50% in the 2016 HBO/Marist poll (Marist Poll 2016).

Salience of Racial/Ethnic Identities, Racial Attitudes, and Political Identities

In navigating similarly divergent White racial frames and counter frames, we expect that racial/ethnic identities, racial attitudes, and political identities will be particularly salient in predicting public opinion towards financially compensating college athletes and athlete protests during the national anthem. First, we expect that racial/ethnic identities will influence opinion, with people of color more supportive of paying college athletes and more accepting of protests than White adults. Black adults have a greater sense of racial/ethnic group connectedness and in-group loyalty than White adults, their experiences of a racist society generating recognition of racial/ethnic inequalities and perceptions of “linked fate” (Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Kam and Burge, Reference Kam and Burge2019). White adults, in contrast, have lower perceived racial/ethnic group connectedness, fewer feelings of in-group loyalty, and higher levels of racial/ethnic prejudice than people of color (Bobo and Johnson, Reference Bobo and Johnson2004; Kam and Burge, Reference Kam and Burge2019; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Owens and Davis2015). Racialized social and political issues, particularly those associated with Blackness, commonly activate in-group sentiment among Black adults and sometimes other groups of color, but also out-group animus among White adults (Kinder and Winter, Reference Kinder and Winter2001; Wallsten et al., Reference Wallsten, Nteta, McCarthy and Tarsi2017; White Reference White2007).

Although most research only includes Black and White respondents, polls and academic studies have found race/ethnicity to be a primary source of division in opinions about these two sports-related issues. For instance, Druckman and colleagues’ (Reference Druckman, Howat and Rodheim2016) survey of a representative sample of U.S. adults found that 37% of respondents overall, but just over 80% of African Americans, supported pay for play for college athletes. An October 2016 poll by Quinnipiac University showed that while 63% of White respondents disapproved of athletes refusing to stand during the national anthem, 74% of Black respondents approved (Quinnipiac University Poll 2016). A 2017 CNN poll found similar results: 59% of White respondents said that protesting players were doing the wrong thing to express their political opinion when they kneeled during the national anthem, while 82% of Black respondents said that it was the right thing to do (Agiesta Reference Agiesta2017). Relatedly, Knoester and Ridpath (Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020) found that the odds for White individuals strongly agreeing with athletes’ basic economic rights were more than 30% lower than the odds for Black individuals strongly agreeing. Also, Knoester and Ridpath’s (Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020) analysis found that Latinx adults were more likely than White adults to support athletes being allowed to be paid more than it cost them to go to school.

Racial attitudes that indicate perceptions of racial/ethnic inequalities and support for addressing these inequalities are also expected to predict public opinion about these sports-related issues. Framing processes have racialized these issues, either explicitly as issues related to racial/ethnic inequalities with direct implications for Black athletes or implicitly in their White racial framings as “aracial.” Critical approaches, including those exemplified by CRT, link awareness of racism to support for antiracist actions to dismantle systems of inequality (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Howat and Rodheim2016; Winter Reference Winter2008). Thus, we expect that recognizing racial/ethnic inequalities and supporting antiracist actions will lead to an awareness of and commitment to addressing racial/ethnic inequalities in college or professional sports. In particular, in the present study, we consider the relevance of beliefs about racial/ethnic inequalities in education and the antiracist actions of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Previous research has found that some racial attitudes are predictive of opinions on paying college athletes and national anthem protests, although existing studies primarily consider the influence of racial attitudes among Whites. Kevin Wallsten and colleagues’ (Reference Wallsten, Nteta, McCarthy and Tarsi2017) survey experiment of White attitudes towards paying college athletes found that White opposition rose with an index of racial resentment but rose more sharply in conditions where Black athletes were presented as the beneficiaries of compensation. The recognition of racial/ethnic inequalities as barriers to status attainment is associated with greater support for athlete financial compensation, while racial prejudice is associated with lower support for athlete compensation (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Howat and Rodheim2016). Consistent with this, Knoester and Ridpath (Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020) discovered that beliefs about status attainment advantages for Whites being a function of racial/ethnic discrimination were positively associated with support for college athletes’ basic economic rights among a large national sample of adults. Racial attitudes also seem to foment Whites’ opposition to player kneeling protests. Jeffrey Montez de Oca and Stephen Cho Suh (Reference Montez de Oca and Suh2020) found that college students who opposed the protests drew on racial stereotypes to position (Black) players as immature and ignorant. They voiced a desire for (White) fans and owners and managers to be able to control and sanction protesting players, revealing a feeling of entitlement to Black athletes’ labor without having to know or care about their concerns. Similarly, Michael Serazio and Emily Thorson (Reference Serazio and Thorson2019) reported on a nationally representative survey of Americans that included an open-ended question about what is good or bad about the mixing of sports and politics. Qualitative comments illustrated a “common sense racism” that players, who are predominately Black, are “…threatening to society; that players are not intellectually equipped to engage them [debates about politics]; and that players are illegitimate as leaders” (p. 162).

Finally, we also expect that political identities will be important in predicting public opinion. First, self-identified conservatism indicates a resistance to change, a nostalgia for the past, and support for the status quo (Montez de Oca and Suh, Reference Montez de Oca and Suh2020; Wallsten et al., Reference Wallsten, Nteta, McCarthy and Tarsi2017). For the issues we address, major stakeholders like the NCAA, team owners, and corporate sponsors have a vested interest in maintaining existing ideological and material arrangements, illustrating the mutual reinforcement of systemic racism and neoliberal capitalism (Singer Reference Singer2005; Weems and Singer, Reference Weems Anthony, Singer, Thompson-Miller and Ducey2017). Thus, conservatism is likely to be associated with opposing changes to college athletes’ compensation and disruptions to sacralized rituals of sports nationalism. In addition, political elites, and especially Donald Trump in the case of protests during the national anthem, have sought to frame these sports-related issues in purposive ways. For example, after Kaepernick began his protests in August of 2016, Trump objected to his actions by suggesting that protesting players leave the country. Of course, since then, Trump, members of the Republican party, and other conservatives have repeatedly signaled that their adherents should oppose protests during the national anthem (Intravia et al., Reference Intravia, Piquero and Piquero2018). Republicans in states such as Ohio and Michigan have passed legislation to ensure that college athletes are not treated as compensated employees, whereas Democrats have tended to advocate for greater economic and bargaining rights for college athletes (Bivens Reference Bivens2017). Relatedly, NCAA President Mark Emmert and some NFL team owners are known donors to Republican party candidates (Solomon Reference Solomon2016). Thus, individuals who identify as supporters of Donald Trump or are members of the Republican Party are expected to oppose college athlete financial compensation and athlete protests during the national anthem.

Druckman et al. (Reference Druckman, Gilli, Klar and Robison2014) and Wallsten et al. (Reference Wallsten, Nteta, McCarthy and Tarsi2017) found that neither political party nor political ideology were associated with attitudes towards paying college athletes (see also Mondello et al., Reference Mondello, Piquero, Piquero, Gertz and Bratton2013). Other studies, however, have found political ideology predictive, with conservatism associated with lowered support for paying student athletes (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Howat and Rodheim2016; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020). On the issue of kneeling protests, Jonathan Intravia and colleagues (Reference Intravia, Piquero and Piquero2018, Reference Intravia, Piquero, Piquero and Byers2020) found political conservatism associated with disagreement that Nike should use Kaepernick in advertisements and disagreement that athlete kneeling protests are appropriate. Similarly, Barış Sevi and colleagues (Reference Sevi, Altman, Ford and Shook2019) found that liberal ideology was associated with support for NFL players kneeling during the national anthem among a sample of college students.

HYPOTHESES

Based on the conceptual framework and literature reviewed above, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1: There will be substantial opposition to and moderate support for paying college athletes and professional athletes protesting by not standing during the national anthem.

Hypothesis 2: Racial/ethnic identities will predict public opinions about these issues; that is, White individuals will be more likely than particularly Black but also Latinx and other people of color to oppose paying college athletes and professional athletes protesting by not standing during the national anthem.

Hypothesis 3: Racial attitudes will be linked to public opinion about these issues. In particular:

Hypothesis 3a: Compared to believing that advantages for White students exist in the educational system, believing that there is racial/ethnic equality in education or that Black and Latinx students have educational advantages will be positively associated with opposition to paying college athletes and professional athletes protesting by not standing during the national anthem.

Hypothesis 3b: Believing that the Black Lives Matter movement overvalues the lives of Black individuals, compared to equally valuing all lives, will be positively associated with opposition to paying college athletes and professional athletes protesting by not standing during the national anthem.

Hypothesis 4: Political identities will be related to public opinions about these issues. That is:

Hypothesis 4a: Self-reported conservatism will be positively associated with opposition to paying college athletes and professional athletes protesting by not standing during the national anthem.

Hypothesis 4b: Intentions to vote in 2016 for Donald Trump, the Republican candidate, will be positively associated with opposition to paying college athletes and professional athletes protesting by not standing during the national anthem.

METHOD

Data for this study come from the online Taking America’s Pulse 2016 Class Survey, which was designed and implemented by researchers at Cornell University’s Roper Center for Public Opinion Research and the GfK Group (Enns and Schuldt, Reference Enns and Schuldt2016). Sampled responses (N = 1461) were designed to be representative of non-institutionalized U.S. adults eighteen years of age and older after post-stratified weighting by gender, age, race/ethnicity, region, educational attainment, and household income according to Current Population Survey data. Thus, as recommended, weights are applied in all analyses. Respondents were chosen using an equal probability selection method (EPSM) from the KnowledgePanel, a nationally representative panel of U.S. households generated using address-based probability sampling. Households within the panel are given free Internet access and a web device for survey completion if needed and small raffle prizes incentivize participation. Survey responses were collected between October 5–25, 2016 and the response rate was 67.4% (i.e., 1461/2167). The percentage of missing data from respondents was no more than 2% (i.e., 32/1461 responses) for any variable used in analysis. Multiple imputation with chained equations over ten imputations is used in the analysis to address these small amounts of missing data.

The descriptive characteristics for all variables used in the analysis are presented in Table 1. The first of the two dependent variables indicates opposition to paying college athletes. Respondents were asked, “Do you believe that the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletics Association) should or should not pay college athletes for their participation in varsity sports?” Response options (0 = should; 1 = should not) are coded to represent opposition to payment. The second dependent variable indicates opposition to athletes protesting during the national anthem. Specifically, respondents were asked, “Do you believe that it is acceptable or unacceptable for a professional athlete to protest by not standing during the National Anthem?” Response options (0 = acceptable; 1 = unacceptable) are coded to represent opposition to professional athletes protesting.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for all Variables used in the Analyses

Note: N = 1461; weighted estimates presented; reference categories in parentheses.

a Identified as Asian American/American Indian/Native Hawaiian/PI/2+ races

The primary independent variables for this study include self-reports of racial/ethnic identities, racial attitudes, and political identities. Racial/ethnic identities are coded with dummy variables for identifying as: (1) White only (reference category), (2) (any) Black, (3) (non-Black) Latinx, or (4) a person of color self-identifying as Asian American, American Indian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or multiracial (combined into one variable because of small sample sizes). Racial attitudes include assessments of racial/ethnic inequalities in education and opinions about the Black Lives Matter movement. The racial/ethnic educational inequality measure stems from responses to a randomly assigned version of the question: “Do you believe that [White/Black and Latino] students have more, less, or the same chance of success than [Black and Latino/White] students in the education system today?” Response options included “more of a chance,” “less of a chance,” and “equal chance.” Dummy variables signify a belief that: (1) White students have educational advantages compared to Black/Latino students (reference category), (2) White, Black, and Latino students have equal chances of success in the educational system, or (3) Black and Latino students have educational advantages. Respondents were also asked, “From what you have seen or heard, do you think people in the Black Lives Matter movement think that Black lives matter more than other lives or the same amount?” Responses (0 = They think all lives matter the same amount; 1 = They think Black lives matter more) are coded to indicate whether respondents thought that the Black Lives Matter movement overvalued Black lives. Finally, political identities include self-reported conservatism and 2016 voting intentions. Conservatism is measured on a continuum (1 = extremely liberal; 7 = extremely conservative). Dummy variables (i.e., Vote Trump (reference category), Vote Clinton, Vote other, and Does not intend to vote) are used to indicate 2016 voting intentions. The variables indicate responses to the question: “If the presidential election were being held today, would you vote for?”, with options that consisted of “Hillary Clinton, the Democratic candidate;” “Donald Trump, the Republican candidate;” “Other;” and “Do not intend to vote.”

Other predictor variables include age, educational attainment, gender, household income, employment status, marital status, household size, rurality, and region. Age (18–29 (reference category), 30–44, 45–59, or 60+ years old) and education (high school or less (reference category), some college, or college) consist of categorical dummy variables, while gender is dichotomous (0 = female; 1 = male). Household income (in $25,000’s) and employment status (0 = not working in paid labor; 1 = working in paid labor) indicate socioeconomic statuses. Marital status consists of dummy variables for being married, cohabiting, or single (reference category). Household size (number of coresidents), rurality (0 = resides in a metropolitan statistical area; 1 = does not reside in a metropolitan statistical area), and region (dummies for Midwest, Northeast, South, and West (reference category)) are also included in the analysis.

RESULTS

First, we review levels of opposition to paying college athletes and professional athletes protesting during the national anthem based on descriptive results. Then, we analyze the regression results from predicting public opinion on these issues, focusing on hypotheses about the salience of racial/ethnic identities, racial attitudes, and political identities. As shown in Table 1, the descriptive results suggest that in 2016 most U.S. adults opposed paying college athletes and believed that athlete protests during the national anthem were unacceptable. Specifically, just under two-thirds (65%) believed that it was unacceptable for a professional athlete to protest by not standing during the national anthem, while over half (59%) felt that the NCAA should not pay college athletes for their sports participation (the unweighted sampled responses are similar). Thus, there is support for Hypothesis 1, which anticipated substantial opposition to the NCAA paying college athletes and professional athletes kneeling in protest during the national anthem.

The binary logistic regression results from predicting public opinion about the NCAA paying college athletes are presented in Table 2. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, which anticipated that White adults would be especially likely to oppose paying college athletes, the Model 1 results indicate that the odds of Black (OR = 0.20, p < .001), Latinx (OR = 0.50, p < .001) and other people of color (OR = 0.43, p < .001) opposing the NCAA paying college athletes were typically less than half of the odds of White respondents doing so.

Table 2. Results from Binary Logistic Regressions of the Opinion that the NCAA Should Not Pay College Athletes

Note: N = 1461; weighted estimates presented. OR signifies odds ratio.

In Model 2 of Table 2, as suggested by Hypotheses 3a and 3b, racial attitudes further predict opposition to paying college athletes. That is, compared to recognizing systematic White advantages in the educational system, believing that Black and Latinx students are advantaged is positively associated (OR = 1.62, p < .05) with opposition to having the NCAA pay college athletes, as expected; there is also some evidence that believing that White, Black, and Latinx students have equal chances of success in education is positively associated with opposition to paying college athletes (OR = 1.29, p < .10). In addition, those who perceived that the Black Lives Matter movement overvalues Black lives instead of equally valuing all lives also were more opposed to having the NCAA pay college athletes (OR = 1.36, p < .05). Finally, in line with Hypothesis 4a, self-reported conservatism is positively associated with opposing payment to college athletes (OR = 1.19, p < .01), as shown in Model 3. In fact, the addition of political identities into the equation in Model 3 overwhelms the racial attitudes findings, yet racial/ethnic differences in support for paying college athletes persist.

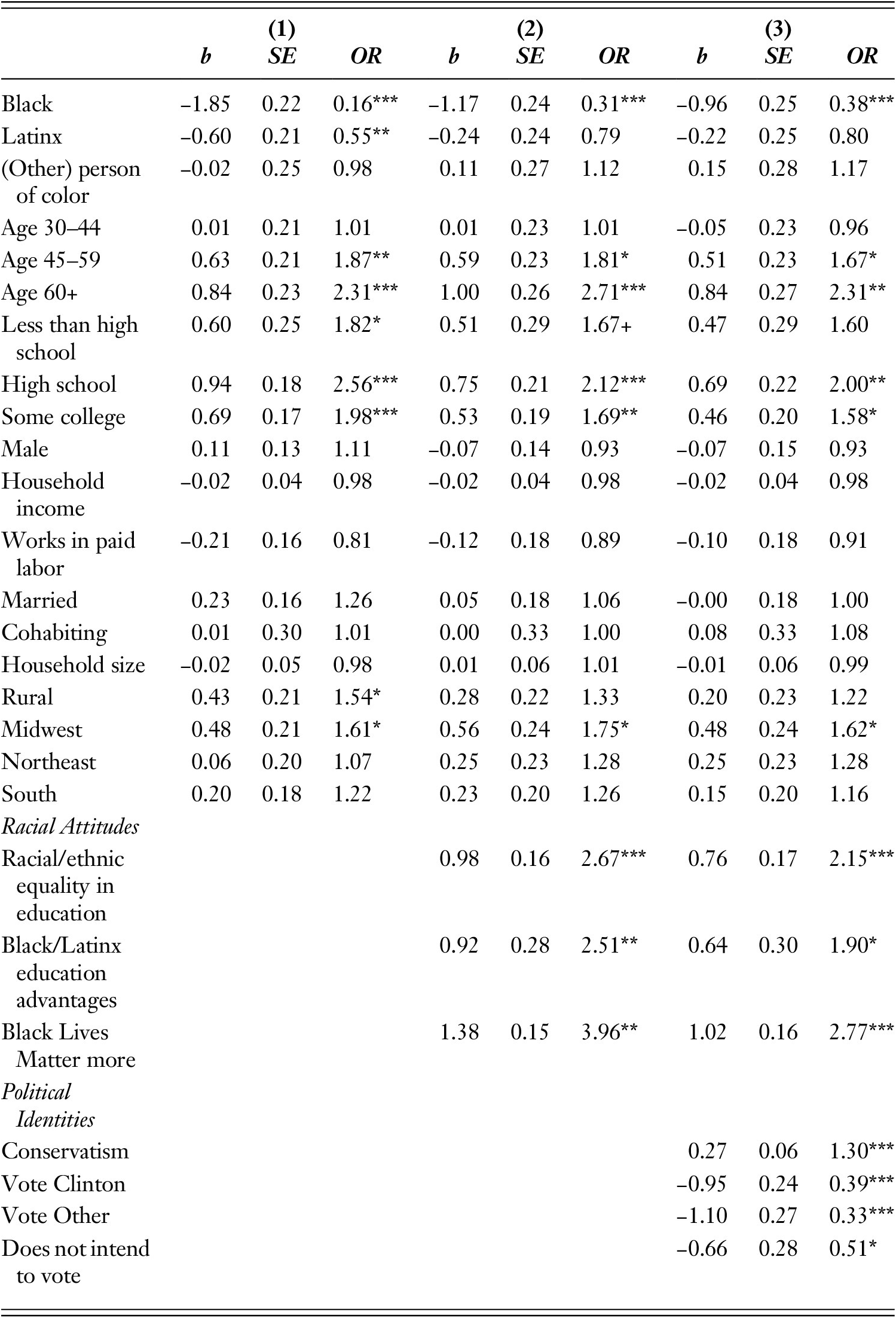

We now turn to the regression results of public opinions about the acceptability of professional athletes protesting by not standing during the national anthem, which are displayed in Table 3. As shown in Model 1, and anticipated by Hypothesis 2, Black (OR = 0.16, p < .001) and Latinx (OR = 0.55, p < .01) respondents were significantly less likely than White respondents to believe that protesting by not standing for the national anthem is unacceptable. In Model 2, support emerges for Hypotheses 3a and 3b. That is, compared to recognizing White advantages in education, believing that Black and Latinx students are advantaged (OR = 2.51, p < .01) or that White, Black, and Latinx students have equal opportunities for success in education (OR = 2.67, p < .001) is associated with a more than doubling of the odds of believing that protesting during the national anthem is unacceptable. In addition, thinking that the Black Lives Matter movement overvalues the lives of Black individuals (OR = 3.96, p < .01), instead of equally valuing all lives, is associated with a quadrupling of the odds of thinking that protesting during the national anthem is unacceptable, in line with what was hypothesized. It is also notable that the inclusion of racial attitudes into the equation in Model 2 appears to partially explain Black-White differences and completely overwhelm Latinx-White differences in beliefs about the acceptability of protesting during the national anthem.

Table 3. Results from Binary Logistic Regressions of the Opinion that it is Unacceptable for a Professional Athlete to Protest by Not Standing During the National Anthem

Note: N = 1461; weighted estimates presented. OR signifies odds ratio.

Finally, as shown in Model 3 of Table 3, political identities are associated with beliefs about protests during the national anthem, as predicted by Hypotheses 4a and 4b. In particular, self-reported conservatism is positively associated with believing that it is unacceptable for professional athletes to protest by not standing during the national anthem (OR = 1.30, p < .001). Reported intentions to vote for Donald Trump are also positively associated with believing that national anthem protests are unacceptable; that is, reported intentions to vote for Hillary Clinton (OR = 0.39, p < .001), another candidate (OR = 0.33, p < .001), or to not vote (OR = 0.51, p < .05) are each associated with around a 50% decline in the odds of believing that professional athletes protesting by not standing during the national anthem is unacceptable. After accounting for political identities in Model 3, Black-White differences and the significance of racial attitudes persist, although their associations with beliefs about the unacceptability of protesting during the national anthem are lessened.

DISCUSSION

Using nationally representative data from the Taking America’s Pulse 2016 Class Survey, this study examined public opinions about financial compensation for college athletes and athlete protests during the national anthem, with a focus on the relevance of racial/ethnic identities, racial attitudes, and political identities. Fundamentally, these issues concern the rights of Black men in college and professional football and basketball within a society that has historically exploited Black labor and refused to offer Black individuals basic human rights (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Knoester et al., Reference Knoester, Ridpath and Allison2021). In our applications of Critical Race Theory and framing theory to understand these issues, we note that the two primary framings of both issues have coalesced around different understandings of race/ethnicity, social inequality, and politics. One, a counter frame of antiracism advanced by people of color and their allies, including many athletes themselves, draws explicit attention to racial/ethnic inequalities, conceptualizing payments to college athletes and protests during the national anthem as racial justice issues that are sports-related extensions of hundreds of years of Black exploitation and racism (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Feagin Reference Feagin2020). In contrast, what Feagin (Reference Feagin2020) describes as White racial framings present a colorblind view, invoking supposedly aracial and apolitical principles such as amateurism and respect for sacred sports nationalism (Kendi Reference Kendi2016; Knoester et al., Reference Knoester, Ridpath and Allison2021; Kusz Reference Kusz2007). Together, these framings activate and accentuate racial attitudes, political identities, and the salience of racial/ethnic identities—in sports-related interactions and interpretations (Feagin Reference Feagin2020; Hartmann Reference Hartmann2016; Winter Reference Winter2008). Below, we review our hypotheses, recap the support that emerged for them, and further contextualize our findings.

First, the descriptive results offered support for Hypothesis 1, which anticipated substantial opposition and overall mixed support for paying college athletes and for athletes protesting during the national anthem. Specifically, 59% of U.S. adults in 2016 felt that the NCAA should not pay college athletes and 65% believed that it was unacceptable for athletes to protest during the national anthem. These statistics are consistent with the results of polls conducted between 2012 and 2016, which also found more opposition than support for athletes’ rights on these issues (Marist Poll 2016; Mondello et al., Reference Mondello, Piquero, Piquero, Gertz and Bratton2013; Quinnipiac University 2016; Prewitt Reference Prewitt2014).

Our second hypothesis anticipated that racial/ethnic identities would be associated with public opinions about paying college athletes and athletes protesting during the national anthem such that White adults, compared to adults who identify as Black, Latinx, or (other) people of color, would be more likely to oppose paying college athletes and athletes protesting. We found support for these expectations in predicting public opinions about paying college athletes, suggesting that the supposedly aracial ideal of amateurism that maintains White racial and economic privileges is particularly sacred to White individuals. We also found consistent evidence that Black individuals are more likely than White individuals to support athletes protesting. This finding is in line with previous research and supports the argument that in-group loyalties, self-interests, and racialized life experiences encourage Black individuals to be more sympathetic to the rights of free speech and the pursuit of other basic rights, with an understanding that basic rights have been historically denied to Black individuals and are a focus of dissent by Black athletes. White individuals have been far less concerned about equality for people of color, and especially Black Americans, and have frequently backlashed against their pursuits of basic rights (Delgado Bernal Reference Delgado Bernal2002; Kendi Reference Kendi2016; Kusz Reference Kusz2007). We also find evidence that Latinx respondents are more supportive of athletes protesting during the national anthem compared to Whites, although these differences do not remain significant after considering racial attitude and political identity variables. Overall, while scarce empirical research has considered the relevance of racial/ethnic identities for public opinions about sports and society-related issues such as the ones that we consider here, beyond Black-White differences, we find compelling evidence that identifying as Latinx or as a person of color leads to different public opinions compared to identifying as White, as well (Feagin Reference Feagin2020; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020). Future research that further considers how and why unique public opinions may develop among especially Latinx, Asian American, American Indian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and/or multi-racial adults would be a valuable addition to understandings of sports and society issues.

Hypothesis 3 focused on the expectation that racial attitudes would predict public opinions about paying college athletes and athletes protesting during the national anthem. Specifically, we assessed the implications of beliefs about racial/ethnic discrimination in education and the intentions of the Black Lives Matter movement. We anticipated that a lack of recognition of racial/ethnic discrimination and inaccurate perceptions of Black Lives Matter would encourage opposition to paying college athletes and having athletes protesting during the national anthem. In fact, there was very strong and consistent evidence that these racial attitudes shape public opinions about athletes protesting during the national anthem. There was also initial evidence that these racial attitudes predict public opinions about paying college athletes, but the associations were overwhelmed by political identities and became nonsignificant in our full model, an unsurprising fact given the extent to which racial attitudes are interwoven with political identities (Feagin Reference Feagin2020; Winter Reference Winter2008).

Finally, we hypothesized that political identities would shape public opinions such that self-reported conservatism and intentions to vote for Donald Trump would be positively associated with opposition to paying college athletes and athlete protests during the national anthem. Indeed, self-reported conservatism consistently predicted opposition to these behaviors, as expected. This finding illustrates how conservatism often perpetuates colorblind racism through resisting calls to change processes of systemic racism, both in the case of preserving the myths of amateurism and in prioritizing sports nationalism rituals and authoritarian expectations for normative behaviors during them over concerns about antiblack police brutality (Feagin Reference Feagin2020; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Knoester et al., Reference Knoester, Ridpath and Allison2021). Meanwhile, intentions to vote for Donald Trump were only found to be significantly predictive of opposition to athletes protesting during the national anthem. This association was striking; the odds that respondents who did not intend to vote for Trump would find athlete protests to be unacceptable were typically less than half of the odds among likely Trump voters. In sum, these findings offer rigorous evidence that political identities do shape public opinions about these racialized sports-related issues, even after accounting for a host of background and especially race-related covariates. Even around the advent of the NFL protests in 2016 and Trump’s first politicizing of these protests before being elected President, Trumpism appears to have framed the protest actions in the minds of its constituents as unacceptable.

Overall, the findings of this study provide a snapshot of how sports-related controversies are commonly, if not inescapably, racialized and politicized—and what that means for public opinions. In particular, it offers evidence of the implications of White racial framing and counter framing for public opinions, and the negotiation of cultural values, amid both continued pushes to address racial/ethnic inequalities in sports and society and backlashes against antiracism efforts (Feagin Reference Feagin2020; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Knoester et al., Reference Knoester, Ridpath and Allison2021). By embracing ideals of amateurism and sports nationalism as somehow transcending race and racism, the White racial frame is deemed aracial and apolitical—yet this frame is not devoid of but obscures the interests and privileges of Whiteness. As Ibram X. Kendi (Reference Kendi2019) argues, being “not-racist” represents a failure to acknowledge and address racism; antiracist actions are needed.

Indeed, our analysis is informed by CRT and its tenets about the permanence and pervasiveness of racism, the need to challenge dominant ideologies, the neglect of voices of color, Whiteness as property norm, and calls for social justice. These tenets lead us to the conclusion that the two framings that we focus upon in the present study—and the opinions that are linked to them—are neither empirically nor morally equivalent; “there is no neutrality in the racism struggle” (Kendi Reference Kendi2019, p. 9). Counter frames have more accurately identified and prioritized the racial/ethnic inequalities of both college athlete financial compensation and athlete protests during the national anthem and further advocated for antiracist actions that work to change dominant ideologies, elevate voices of color, challenge the inequalities linked to the Whiteness as property norm, and seek social justice for all.

Clearly, sports are not aracial or apolitical. Our findings reflect larger patterns of political polarization and yet also emerge from the racialized and politicized experiences and negotiations that people are often a part of in their own sports-related interactions. In fact, sports-related interactions are common, as most Americans play, watch, or follow sports and identify as sports fans (Allison and Knoester, Reference Allison and Knoester2021).

Still, there is a cultural distinctiveness to sport and unique contours in its racialization and politicization. That is, even beyond its enormous significance, sport matters in a special, subtle way because it is characterized by cultural logics that stress play, distraction from more “serious” pursuits, and apoliticism. At the same time, sport interactions offer cultural terrain for racialization and politicization processes. For example, sport interactions offer terrain for longstanding, inaccurate ideas about the biological existence and distinctiveness of racial groups to be given legitimacy, supporting racial stereotypes and rationalizing inequalities. Consequently, sport often enables ideas about race that are foundational to social inequality while simultaneously being recognized as a meritocratic, raceless space and celebrated for its cultivation of moral fortitude (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Hartmann Reference Hartmann2016).

Yet sports-related interactions can also spur social change (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Kusz Reference Kusz2007). Thus, it is important to recognize the social forces, struggles, and consequences at play. Arguably, this is especially true for primary stakeholders in the sports and political spheres. The need for antiracist actions is clear, yet there are market and political coalition interests that need to be negotiated. Racial ideologies that maintain White privilege have always been and will continue to be flexible. Pushes for greater athlete rights, changes in the structures of sports and society, and antiracist actions should anticipate pushback. Nevertheless, changes are necessary (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Feagin Reference Feagin2020; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Montez de Oca and Suh, Reference Montez de Oca and Suh2020).

Since 2016, in spite of years of racializations and racist politicizations of sports by President Trump, and maybe in part because of them, along with the antiracist actions by many individuals, attitudes surrounding these two sports-related issues seem to have shifted towards enhanced support for athlete rights and concern about racial/ethnic inequalities (Intravia et al., Reference Intravia, Piquero, Piquero and Byers2020; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Marist Poll 2017; Seton Hall Sports Poll 2019). As an additional CRT tenet suggests, antiracist changes generally require interest convergences between those seeking change and those in power (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Delgado Bernal Reference Delgado Bernal2002; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020; Singer Reference Singer2005). Changes in public opinion offer some motivation for stakeholders to prioritize antiracist actions. The California Fair Pay to Play Act and related legislation in other states have also pressured the NCAA to move towards changing its policy on financial compensation for athletes. In addition, outrage about police brutality, unprecedented demonstrations and calls for racial reckonings, and athlete activism—particularly after the death of George Floyd—have further pushed sports stakeholders to reverse stringent objections to voices-of-color expressing dissent in sports contexts. There have even been some visible actions in support of antiracism by sports stakeholders and entire leagues. Thus, some convergence of interests, precipitated in part by sports-related controversies, has become part of fulfilling antiracist goals within sports and in society—at least for now. Nonetheless, that will not always be the case and further work will be needed (Cooper Reference Cooper2019; Edwards Reference Edwards2017; Feagin Reference Feagin2020; Knoester and Ridpath, Reference Knoester and Ridpath2020).

Before concluding, there are some limitations to this study to note. It relies on cross-sectional data and our interpretations of the processes at work, rather than subjective understandings that are articulated by the respondents. Longitudinal research would enable better understanding of attitudes as they continue to evolve over time. Also, there are limitations in the closed-ended nature of the questions that we use; in-depth interviews with respondents could allow for deeper, more nuanced understandings. In addition, our assessment of public opinions about paying college athletes may be complicated by how people interpret “NCAA payment;” there are a variety of means of offering additional compensation to college athletes and potential complications involved in how respondents may react to the NCAA as a source of payments, as opposed to other sources (e.g. universities themselves, boosters, corporations, etc.). Relatedly, we assume awareness of the frames that we describe on the part of respondents given their widespread dissemination via mainstream, social, and online media. Nevertheless, we were not able to assess respondents’ adoption of these frames directly from the data.

Public opinions about sports-related issues are worthy of attention. Future work should continue to seek to understand how sports-related interactions symbolize, help to negotiate, and even challenge racialized and politicized understandings about issues in sports and in society at large.