Orientation

This article has been created by a collective of Environment and Arts educators, who assembled at a theory colloquium in Australia. It was entitled the ‘International Moving Colloquium on Collaborative Theory Mapping in the Anthropocene: Lines, Knots and Knotting’ and was a two-day moving colloquium focused on mapping environment, the Anthropocene, and education theories applying arts-based educational research methods. The colloquium was ‘moving’ because it was held over two sites (Sydney in late 2018 and the Gold Coast in early 2019); it also invited the movement of thought. Researchers were invited through a call, and the workshops were funded by the Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE) Environment and Sustainability Education Special Interest Group (ESE SIG). Four knotted concepts — working from Ingold’s (Reference Ingold2007, Reference Ingold and Dudley2012, Reference Ingold2015) concepts of knotting — emerged from the first day, namely traces, shimmer, resonances, and watery. These concepts were then put to work on the second day by the participants, who assembled underneath each concept by choice.

In the case of the watery knot explored herein, we are a collective of experienced researchers, PhD students, early career researchers, and arts and environmental academics. What follows is an assemblage of our workings of the watery knot as concepts that are potentially useful to environmental and arts-based educational research. The article therefore seeks to activate concepts around experimental, artful, theoretical thinking-with/through the entangled assemblage (or knots) of water/watery/watering, engaging subjective and arts-based experiences. We have leaned into arts-based methodologies as a fresh and innovative way to ‘work’ the watery knot to ‘work’ the environmental theory — engaging arts-based modalities as a ‘meta-knotting’ of the concepts. It is noted that arts-based forms are peculiar — they generate unique experiences and learnings, affectively. The art experience forces thought to think (Atkinson, Reference Atkinson, Knight and Lasczik Cutcher2018; Lasczik Cutcher & Knight, Reference Lasczik Cutcher, Knight, Knight and Lasczik Cutcher2018); it is ontological and epistemological. The reader will thus find arts-based positionings, theorisings and portrayals throughout this text. The powerful imagery and artful writing are meant to engage the reader or viewer in layered encounters — of thought, theory, and theme. They both disrupt and enhance the more traditional text, creating further layered readings, and are meant to challenge and interrupt as well as support and exemplify. This is the complexity that is arts-based research.

This article therefore contributes to transdisciplinary, posthumanist research on the agency of water within the many contexts and positionings of environmental education, underpinned by artful encounters. It is also an experience-in-the-making, and can be read as such — as an opening for aesthetic, ontological, epistemological, environmental experiences, as well as a scholarly, theoretical mapping of water/watery/watering. It is a multilayered, experiential thought experiment.

As an orienting device, we therefore raise the following questions as a way to position the unfolding of concepts in this article. What might a posthumanist pedagogy of water look like? How does water teach and learn? What potentials for teaching/learning does an artful geo-onto-episto-eco-ethico-politico engagement with water produce? We seek not to answer these questions, but rather have them linger in the reading and in the experience.

This article is a theoretical mapping (or suite of cartographies) that assemble/s the voices and contributions of the individual authors through a collective engagement in artful or arts-based practices, including walkography, photography, artmaking and poetics, as well as geo-political-commodified perspectives, as modes for generative dialogue around embracing, tying, knotting and dissembling the knots and knottings of the concepts. The walkography is unpacked further below.

As previously noted, we take as our conceptual source Ingold’s (Reference Ingold2007, Reference Ingold and Dudley2012, Reference Ingold2015) notions of lines, knots and knottings, which are engaged in order to frame in/with the posthuman as waterlines, wateryknots and wateringknottings that may be explored through the ‘relational intensities’ of subjects’ common and uncommon worlds in environmental education practice and theory (Rousell & Cutter-Mackenzie, Reference Rousell, Cutter-Mackenzie, Cutter-Mackenzie, Malone and Barratt Hacking2018). Ingold (Reference Ingold2015, p. 14) argues that ‘knots and knotting have largely been sidelined’ when thinking critically, and that researchers persist in trying to understand culture, including networks, through conventional and psychological lines of thought. Rather, Ingold encourages an entanglement with knotty theory and to engage such knottings to create new and useful conceptual frameworks; in this case, for education. What is being knotted and what implications may be drawn (Green, Reference Green2014) are important when traces, threads and unravellings are also evident.

The concept/s of water/watery/watering is/are thus knotted concept/s as portrayed herein. They knot together as an assemblage of haecceities, of lived events that are looped, tethered and entangled as material and conceptual agencies that inhere inside situated encounters with posthuman ecologies (Braidotti & Bignall, Reference Braidotti and Bignall2018). A similar premise for the discussion has been developed by de Freitas (Reference de Freitas2014), in that our ‘theoretical framework is like a mesh-work of lines … a knot of entangled lines’ (p. 285). Such knottings are posthuman concepts that work topologically, continuously deforming and reforming, blurring the boundaries between insides and outsides. This is because posthumanism is not so much concerned with the question ‘What does a concept mean?’ but rather ‘How does it work on us and with us?’

This article is structured through a discussion of the knotted assemblages and experiences and tetherings of water/watery/watering as we have activated them in the various artful and arts-based experiments described below, as well as through the more prosaic passages. The sections are positioned as knots and knottings, and pivot from an introductory visual essay, which is not illustrative but rather is praxic, as it responds to our initial provocation of thinking with the concept of ‘watery’.

It should be noted that the knotted concept/s of water/watery/watering are entwined as an assemblage that may unevenly and irregularly foreground (and background) elements within its assemblage, and will shift and move and vibrate (Ingold, Reference Ingold2015). Indeed shiftings, vibrations, resonances and entwinings are all present in these knots and the knots they generate and those with which they interact. Indeed, as Rabyniuk (Reference Rabyniuk2016) asserts, knots are complex forms. They complicate and contradict and result from opposing forces drawn into tension as both sensitive and hostile; both as obstructions and bondage as well as being integral to ensuring the safety and security of systems and riggings. A knot is entangled, difficult and potentially painful, but also elegant, resolved and neat, implying repair and resolution. Indeed, knots ‘are made to be undone [and] consist in these contradictions. The apparent oppositions in their construction are interlaced with their symbolic, technical, and functional properties and are bound to the materials, techniques, and traditions of their production’ (Rabyniuk, Reference Rabyniuk2016, p. 1). Such functions, symbolism and materialities operate as useful theoretical positionings for environmental, and other, education.

As Ingold (Reference Ingold2014) asserts, knotting has a central notion of coherence, a holding together, a form-giving or form-making objective. It is a purposeful, material engagement. Knotting seeks to work with lines, meshworks, entanglements, metonymics and elegance. In this way, it could be argued that the practices and praxes of artmaking are fundamental processes of knotting, as ways of holding together that which ‘would otherwise be a formless and inchoate flux’ (p. 1). Indeed, art is saturated with political and cultural complexity and relationality, which is why it is a useful approach for generating concepts, among many other things. Through the knotting and unravelling and entangling and smoothing of artmaking, ‘drawn threads invariably leave trailing ends that will … be drawn into other knots with other threads’ (Ingold, Reference Ingold2007, p. 186) in a rhizomatic spectrum of actions and ideas, material and conceptual engagements. In such moments, the limits of academic language can often constrain such elegant conceptual and relational assemblages as we seek to create in this work. As Lim (Reference Lim, Clarke and Doffman2017) notes, this is because a ‘knot is a material technology for binding and unbinding through friction and tension’ that transcends the literal and thus the ‘properties that make a “knot” knotty somehow also appeal to our storytelling instincts when we’re faced with paradoxes and problems intervening in a life of desires’ (p. 208). We acknowledge the frictions and the tensions that may appear in this work and its readings as useful and generative spaces for further thinkings, knowings and doings (Lasczik Cutcher, Reference Lasczik Cutcher2018), and invite our colleagues to push these ideas further or indeed challenge them. Aesthetic, creative and expressive engagements are useful modalities to exert in the further creation of concepts and actions.

The theoretical considerations in this article thus begin with a visual essay as an arts-based, transdisciplinary and critical initial portrayal — which in itself provokes its own and further concepts, rhizomatically in the reading and in the intertextuality between page and bodies. This intertextuality is relational, it is generative, and it is a space for concept communion — as it was for the authors of the paper who commenced our imaginings through such creative, arts-based modes. As we proceed with our conceptualisations, we follow the visual essay with and by a more conventional suite of discussions interspersed with further water/watery/watering photographic artworks as and around the knotted assemblages we present herein. The reader will encounter these images as stepping stones, positioned again not as illustrations but as aesthetic and theoretical moments that also slow the reading (Lasczik Cutcher & Irwin, Reference Lasczik Cutcher and Irwin2017), with the intention to pause, to linger and to ruminate on the concepts being activated. The artworks are further provocations to think-with and think-through water/watery/watering.

After the visual essay is a discussion around the elemental properties of water as a conceptual and material beginning. The second knot explores prevailing watery concepts of commodification, politics, agency and power. Next, there is an artful waterline that functions as a transformative bridge, which stages a turn towards the arts as a means by which watering can be aesthetically interrupted in order to generate further concepts. In the final section, we resolve our knottings and invite a provocation of further concepts. The entangled knottings begin with adopting a posture of sensuous humility through the visual texts and an aesthetic curiosity towards water/watery/watering as (a) useful concept/s for theorising environmental education.

Taking water/watery/watering for a walk

In beginning our working and watering and resolving and generating theory knottings, we were compelled to be with water, and to walk-document-write through a walkographic methodology (Lasczik Cutcher, Reference Lasczik Cutcher2018). A walkography seeks to engage ‘walking’ as the central method of inquiry, whereby the concept of walking transcends ableist notions of mobilities and rather engages the peripatetics of transdisciplinary practices and thought experiments. Thus the ‘walk’ can be metaphorical, physiological, psychological, intellectual — as a practice of movement — actually, metonymically, affectively. The ‘ography’ is the praxis of documentation, recording, accounting, experiencing, drawing. In the context of this inquiry, and specifically through Ingold’s (Reference Ingold2007, Reference Ingold and Dudley2012, Reference Ingold2015) notions of lines, knots and knottings, our walkography sought to take the lines and knots for a walk, seeking to create entangled, meshworked conceptual knottings, as the artist Paul Klee once asserted, describing drawing. He said, ‘A line comes into being … it goes out for a walk, aimlessly for the sake of the walk’ (Klee, Reference Klee1961, p. 105). In this case the line is a conceptual line of thought, entangled. Such lines become a meshwork (de Freitas, Reference de Freitas2014; Green, Reference Green2014; Ingold, Reference Ingold2007), entwining and knotting through and with multiple, abstract lines of affect, senses, experiences and views. For what is walking, but creating lines with our feet, our eyes, our bodies in motion, becoming multiple, becoming irrevocably knotted and entangled? Lines (and their knottings) can also be experienced from their own capacities and agency as form giving, as aesthetically causal and infinitely in movement. Such methodological yields inform our concept provocations as we set out on our walk from our beachside campus to the water’s edge one very humid summer’s day in February 2019. The following arts-based account is in itself a walkography, as much as the experiences and praxes that have created it — in life and on the page.

water/watery/watering knottings

walking our knottings

feeling its wet keenly in

the watery air

Click here to see and hear the walk - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jBS4JxwT2oM

Watery, water, cool, refreshing, swirling, beauty, political, flow, ocean, bodies, river.

We document words that come to mind as we dwell and think-with the concept of water/watery. Then we walk; we walk-with. Slowly at first, waiting for our group to be together, towards the ocean, towards the beach. There is moisture in the air; the tropical mugginess is intense.

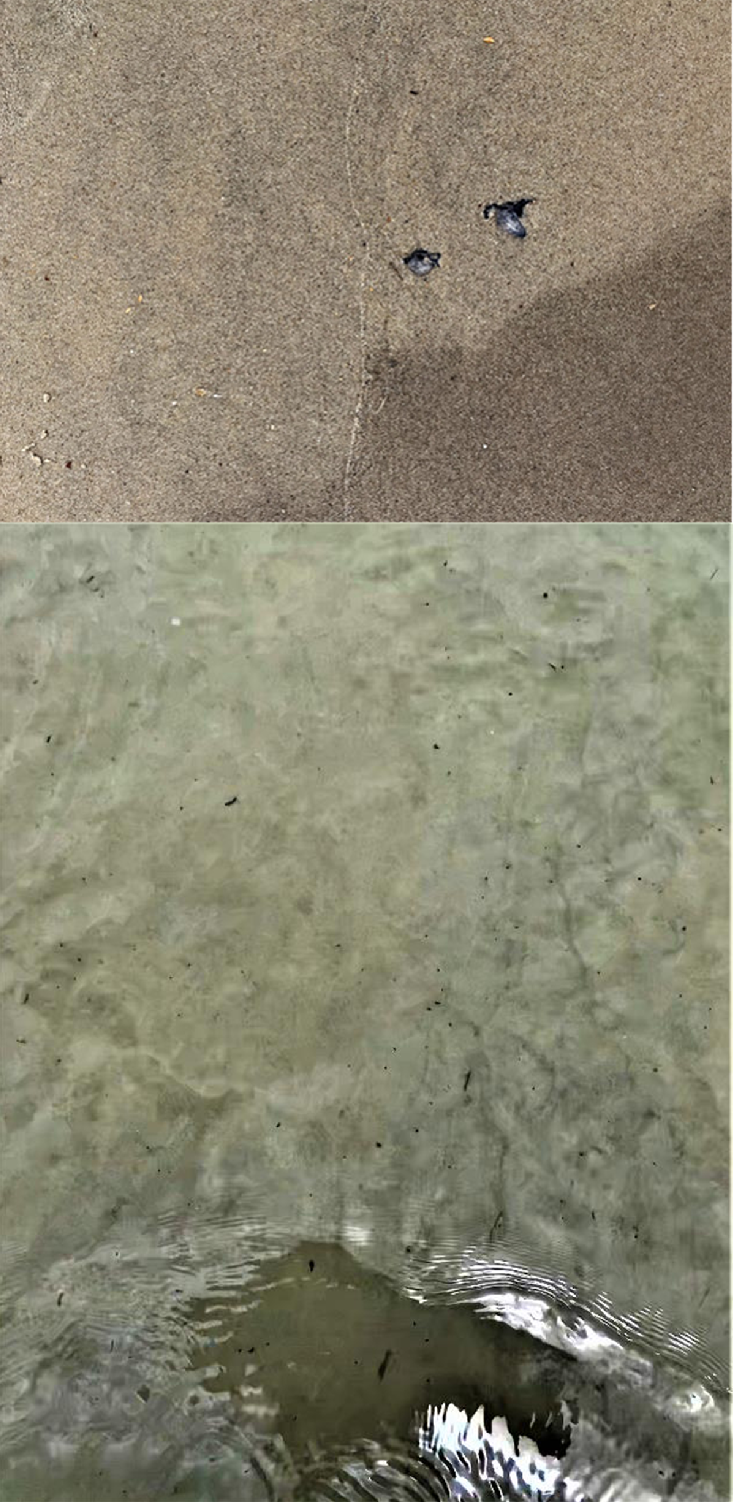

As we walk, slowly, we discuss the power of water to move. First objects, with its power to carve into stone, and then water’s capacity to move our bodies as we swim and experience eddies in the water flow, the vortexes. Our stories are woven into our walking, into our bodies, into the watery air. As we arrive at the beach, we shed our shoes and enjoy the sensation of sand between our toes and crunching underfoot. We travel further down the beach as we are drawn to the water — pulled towards it, into it; so inviting and cool, reflecting the light from the sun, the blue from the sky.

As a group, we observe the seagulls. Our presence disturbs them; they fly away. Wading through the cool, refreshing water brings immediate relief from the humidity enclosing us. Crisp water flows around our legs, threatening to wet our clothes as the waves force the water forwards and upwards and backwards around us. We delight in its slippery coolness, its wet presence, its energetic surf.

From there, we each wander about on our own, sometimes calling to each other, sometimes not, exploring the water in its many forms at the beach: shoreline, surf, foam, eddies, streams, pools. It is hot, steamy and thick as the sun beats down on us, unrelenting. Our stories are woven into our walking, into our bodies, into the watery air.

We come together again to make our leave and, on the way, notice the many bluebottles washed up by the surf and onto the sand; seemingly inert, yet enduringly malicious. They lie there, desiccated and dying but with the power yet to wound. They do. One of our group is stung by these torpid and still bodies, the hot wound unrelenting in its throbbing and burning, a red welt now appearing harsh and cruel.Footnote 1 We walk quickly back to our campus to seek first aid, distracted by the pain. This story is in our bodies, in the watery air. In the walk.

heat rises, sweat drips

water flows as sweet relief

washing heat away

transition to blue

cold to sweat, we are water all

place of fear and strength

birds walk at the beach

people swimming, ocean blue

the sunlight shimmers

early afternoon beach walk

distant hillside, high rise buildings

undisturbed seagulls enjoying summer sun

dangers of our existence, thankful,

water/life

What knots/questions/tensions/feelings/thoughts/concepts/curiosities/sensations does the walking event provoke?

water/watery/watering: materialities, languages and elemental properties

The watery bodies and ecologies encountered through this walk provoke a more detailed engagement with the materiality of water as an elemental force. Following water’s extensive properties allows us to measure and engage its material states as solid, liquid or gas, as well as the volume and force of water’s flow. In following the intensive processes of water, we are able to note its thermodyamic rates of change, evaporation, precipitation, and temperature gradients, as well as its felt watery qualities as an aesthetic medium. This distinction between the extensive and intensive dimensions of water provides insights into water’s material agency as a performative multiplicity (Protevi, Reference Protevi2013), resisting normative scientific readings of water as inert substance and resource while remaining closely attuned to water’s vibrant physicality.

The extensive properties of water are, of course, ubiquitous on this planet. Water is a molecular compound that is colourless, tasteless and odourless and assumes three extensive material phases, namely solid, liquid and gas, depending on the surrounding temperature. Water is liquid in rivers, streams, oceans and other bodies, gas in the atmosphere and bodies, and ice at the North and South Poles in winters and snowy lands. It exists underground in plants and animals, is dense, can entertain in all of its forms, can generate power, is a habitat and a commodity, can carve through the earth, cleanse, yield, hold enormous vessels afloat, provide transportation, and is essential to all living things. Indeed, water is the origin and sustenance of life.

Water’s intensive qualities are also inordinately complex and atypical; its solid state is not denser than its liquid state, ensuring that ice (solid) floats in water (liquid) rather than sinking to its depths. Ice acts as a thermodynamic insulator for the liquid underneath it, protecting and enveloping marine life below. Water’s gaseous state allows it to move intensively through the atmosphere as clouds, moisture, transpiration and humidity, where it may later condense and become liquid once more as rain and as nourishment. Water can dissolve and dilute, cool and heat, filter and insulate.

As a concrete multiplicity, water crystallises with temperatures below zero degrees celsius, reaching its solid state as ice or snow. Snowflakes exhibit near-perfect symmetrical designs, each flake aesthetically different from all others, and designed exclusively on its unique journey to the ground. Ephemeral masterpieces, a snowflake acts as a reminder of the entangled simplicity and complexity of water, as the melting process dissolves its emergent structure within seconds of contact with warmer surfaces. At colder contact, the intensive entanglement of rates of change results in diversified rigidity and textures, from powdery to crumbly to icy, from soft to hard. The intensive qualities of snow can be gentle, comforting and peaceful, or thick, heavy, turbulent and deadly.

Water also acts intensively as a solvent, allowing for dissolution of the frozen flakes, raindrops or gaseous molecules to integrate into the landscape, melting, evaporating and freezing to adapt. Water dissolves minerals, creating new mixtures from the carbon dioxide from the air, the salt from the rocks, the oxygen from the plants. Water is a deterritorialising machine that transports the particulate and the invisible, creating on its path the systems that support life on Earth and all its material languages.

Water’s intensive and extensive processes allow for transformation and the coexistence of its three elemental states within a particular place, a particular climate. While ocean waves pound on the frozen glaciers of the poles, clouds full of water vapour remain gaseous, floating over their liquid and solid counterpart forms, redefining materiality multiple times within a same milieu. Salinity and temperature dictate water densities, which act similar to oil and water separating from one another, allowing the lightest composition (warmer and less salty) to sit on top of the heaviest concoction (colder and saltier). In lakes and rivers, the thermocline is the fictional line that can be drawn at the junction of water masses with temperature variation. In the oceans, surfaces exposed to sunlight, melting glaciers and erosion are some of the drivers behind the different densities, allowing water masses to push onto each other, creating a material flow circling the globe, known as the great ocean conveyor belt, in constant movement. Despite its unnoticed materiality, water density determines the breathing cycles of the biosphere, carrying heat from the equator to higher latitudes in both hemispheres and moving nutrients from the bottom of the seabed back to the surface, acting like a feeding cycle for the entire food chain. The intensive materiality of water density is as vital as the heart of a living organism, pumping the blood flow in a body’s veins.

Such properties, materialities and intensities of water reveal informative and valuable metonymic conceptual openings, especially with respect to the transdisciplinary and transformative possibilities of posthumanist theory in environmental education. One such conceptual opening involves the transcorporeality of water, not just with respect to its shape-shifting material properties but also how and what it acts upon, through and with, ‘the literal contact zone between human and more-than-human nature’ (Alaimo, Reference Alaimo2010, p. 2). Neimanis (Reference Neimanis2013, p. 25) argues that transcorporeality ‘offers expanded epistemologies’. Such openings create new virtual potentials for posthumanist theorising in education, and environmental education particularly. Such posthuman transcorporeal forms establish a useful concept upon which to build generative thinking frameworks, and lead our discussion to the next section, which explores what a watery knotting of political concerns might generate.

water/watery/watering: agency, politics, personhood and commodification

Perhaps by imagining ourselves as irreducibly watery, as literally part of a global hydrocommons, we might locate new creative resources for engaging in more just and thoughtful relations with the myriad bodies of water with whom we share this planet. (Neimanis, Reference Neimanis2013, p. 28)

Recent attempts to think politically with water have made significant philosophical and poetic contributions to posthumanist theory and praxis, perhaps most notably in the growing field of the environmental humanities (e.g., Chen, MacLeod, & Neimanis, Reference Neimanis2013; Harris, Reference Harris2015; Neimanis, Reference Neimanis2013, Reference Neimanis2017). Concepts of hydrologics and feminist embodiments (Chen et al., Reference Chen, MacLeod and Neimanis2013; Neimanis, Reference Neimanis2013), water as political and biopolitical (Bakker, Reference Bakker2012; Protevi, Reference Protevi2013), artful and transcultural engagements with water (Foley, Reference Foley, Malone, Truong and Gray2017; Somerville, Reference Somerville2013), childhood encounters with water (Crinall, Reference Crinall2017; Gannon, Reference Gannon, Malone, Truong and Gray2017), as well as the sonics of water (Harris, Reference Harris2015) are potentially useful theoretical positionings for posthumanist environmental education. In this discussion, we seek to further develop a theoretical framing that builds upon water’s political agency as well as its commodification as a technology of biopolitical control. This knotted approach acknowledges the neocolonial and neoliberal power structures that saturate watery political concerns in the 21st century, and the acute environmental and social injustices that are always already implicated in any watery encounter and discussion.

How can water be politically ‘knotty’ when it is materially so slippery, drippy, rushing and by nature shapeshifts into hard ices and steamy clouds? Any political theory of water/watery/watering is resolutely incomplete or inefficient (Knight, Reference Knight, Snaza, Sonu, Truman and Zaliwska2016, Reference Knight and Hodgins2019; Wood, Reference Wood2013), due to its enormity and complexity. In Australia, water has its own sovereign authority on unceded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s Country, where lived Indigenous concepts and practices of Country involve watery places, watery stories thick with temporal layerings, as well as watery cosmologies. In contrast, in Australia (as elsewhere) water is commodified, captured and controlled as a material resource for the sole purposes of measure, trade, engineering and economic utility. Because water has been imperially stolen, hoarded, marketed, straitjacketed and weaponised by colonial regimes for over 400 years, what we can politically know or ask of water is often violently impeded.

Posthumanist political theory aims to create concepts that work in the cracks of these neocolonial impasses, often through visionary attempts to instantiate alternative constellations of material vibrancy, agency, animacy and value (e.g., see Bennett, Reference Bennett2010; Chen, Reference Chen2012). The extensive properties and intensive qualities of physical things and their impacts establish possibilities to serve human economic interest as they are commodified as resources (Strang, Reference Strang2014). Yet, acknowledging the capacity for physical elements such as water to have inherent agency and value is in itself a political act. Tilley (Reference Tilley2007, p. 19) suggests that the term ‘agency’ refers to affordances and constraints with respect to views and actions. From a posthumanist political perspective, agency is distributed across ensembles of living and nonliving matter (Bennett, Reference Bennett2010). The agency of water is, in this sense, a ubiquitous component of all Earthly assemblages and political ecologies. Indeed, in the context of this article, water’s agency can also be acknowledged as a co-creator of the knowledge shared herein.

As discussed above, water exerts an enormous impact on individual bodies and their environments through molecular associations in organisms, carving out waterways, depositing sediment in the river basins, flooding, orchestrating immense hydrological activities and transformation at an atmospheric and indeed planetary scale. Neimanis (Reference Neimanis2017, pp. 186–187) asserts that humans are indeed ‘bodies of water’, related to and in similar ways to other bodies of water, including lakes, rivers, oceans and other beings, as well as the beings our body-as-host provides, which indicates a notion of disseminated but closely substantial material relations with governmental and moral effects. Although water is often theorised as a life-creating, life-connecting source of abundance, it is also a technology for unjust political determinations of affluence and poverty, toxicity and health, freedom and control, flourishing and death. Clearly, the material properties of water can never be pure or neutral because they are relationally entangled with political ideals, values and agendas at all levels and scales of existence.

The political agency of water also has profound connections with cultural, social and religious practices, with water considered as a propagative and agentive co-constituent of relational meaning within societies (Krause & Strang, Reference Krause and Strang2016). Water inspires novel ways of thinking about key aspects of social relations, including exchange, circulation, power, purification, health, community, and knowledge (p. 633). Although water is an assemblage of hydrating molecules and the metabolic fluid for agricultural production that sustains human life, the notion of water as living, animate and imbued with divine power runs through many cultural contexts in various forms (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Gurung, Chapagain, Regmi, Bhusal, Karpouzoglou, Mao and Dewulf2017). The divinity of water persists in the religious practices and beliefs of both Eastern and Western spiritual traditions, particularly those concerned with existential shifts and relations between material beings and spiritual beings. Contrasted with perceptions of pollution and disorder, water is used in rituals concerned with cleansing in many cultures and religions (Strang, Reference Strang2015). For instance, many Muslims believe that water is the source of life and vital for spiritual cleansing and purification, while Hindus believe water can wash away people’s spiritual transgressions (Ansari, Taghvaee, & Nejad, Reference Ansari, Taghvaee and Nejad2008).

Water and its associated human practices are shaped by cosmologies, knowledge systems, wisdoms, beliefs, stories, values, and traditions (Gibbs, Reference Gibbs2014). Indigenous and postcolonial knowledges recognise the agency of water assemblages, its cooperating living and nonliving components and their interrelations (Gibbs, Reference Gibbs2013). Unfortunately, neoliberal practices continue to assert a dominant regime that separates water politically and economically from its Indigenous, earthly and agentic potentials for value. Herrera’s (Reference Herrera2017) book Water and Politics, for instance, explores water issues in emerging economies and uses the term ‘clientelism’ to describe the exchange of water for votes, also referred to as patronage or vote buying. She cites this practice as starting in the United States in the 19th century and gradually becoming common in majority countries (usually referred to as ‘developing’ nations) in Africa, Asia and Latin America. In essence, the politics of clientelism direct the distribution of water from one ecology to another solely for political and monetary gain, effectively converting access to water from a human (and nonhuman) right into a commodity.

In his book A Future History of Water, Ballestero (Reference Ballestero2019) describes how Latin American water activists infiltrated the World Water Forum in Mexico City in 2006, carrying empty water bottles filled with coins. ‘Inhabiting the space previously occupied by water, the coins inside the bottles insinuated that water had been transubstantiated into money, the ultimate commodity’, Ballestero goes on to describe how ‘the penetrating sound of metal pounding against plastic’ (p. 2) radically disrupting the meeting of international water ‘experts’, and confounding the possibility of any clear, structural contrast between human (and nonhuman) rights and the total commodification of life itself.

Such political issues rub up against the recent bestowal of rivers and other bodies of water with the legal rights of ‘personhood’. Whanganui River in New Zealand, the Ganga and Yuman Rivers in India, and all the rivers in Bangladesh have been considered variously as ancestral and sacred and now have been bestowed with legal and constitutional rights. These decisions recognise the dire importance and agential capacities of waterways for myriad cultural and environmental reasons, with the preservation of nonhuman entities being granted the same legal protections as humans in their respective countries. As Young and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles (Reference Young, Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Lasczik, Wilks, Logan, Turner and Boyd2019) ask:

What does it mean to think about a river as a living entity, as an ancestor? Will it disrupt practices of pollution, or will humans who live near these rivers, move from perspectives of ownership and management towards kin relations? Will granting legal rights to nature minimise harm to the rivers through waste or overfishing and hold more legal weight for prosecution? … Many questions remain about the practical impact of the legal personhood approach. However, the very act of thinking about a river as an interconnected, living entity is an enormous cultural shift in thinking and praxis. (p. 44)

To these questions, we ask another: how might giving rivers personhood lead us to engage with decolonial political discussions that cross the nature-society binary? It is recognised that such a status of personhood seeks to render civil rights to a nonhuman entity, and speaks to alternative power discourses, kin structures and a feminist ethics of relational care (Puig della Bella Casa, Reference Puig de la Bellacasa2017). Philosophically, this shifts the onto-political value of the body of water from a material substance or ‘resource’ that can be possessed to a subjectivity that possesses itself (Ruyer, Reference Ruyer and Edlebi2016). In other words, the value of a body of water is acknowledged as inherent within an ecological subjectivity that exists in-itself and for-itself. The legal category of a ‘person’ in this sense can be understood as the attribution of an axiological existence that is irreducible to ownership, commodity and monetary value.Footnote 2 While the recent attribution of Indigenous personhood to bodies of water does little to redress histories of colonial violence, it does provide a glimmer of hope for a political and legal thought that acknowledges the possibility of a poshumanist revaluation of value. What appears most significant in such cases is not the legal status or renaming of water as personhood, but rather the axiological attribution of inherent and inalienable value to a body of water and the Indigenous human and nonhuman ecologies that have sustained and been sustained by that water body for millennia. This watery attribution, as Neimanis (Reference Neimanis2017, p. 39) asserts, asks us to reconsider — and politically act on — the nexus of human and nonhuman bodies of water, given that ‘the waters we comprise are both intensely local and wildly global: I am here, and now, and at least three billion years old, and already becoming something else’.

The relationship between water and humans is mediated by socio-technology both culturally and biophysically, and thus the study of water prompts us to rethink the notion of techno-politics, to reframe water as simultaneously socio-technical and socio-natural (Bakker, Reference Bakker2012). As it flows, water transgresses geopolitical boundaries, defies jurisdictions, pits upstream against downstream users, and creates competition between economic sectors, both for its use and for its disposal, which invokes intertwined issues of water quantity and quality. Water is thus intensely political in a conventional sense and is implicated in contested relationships of power and authority. The historical relationship between water and modernity is intimately, viscerally connected with the histories of Western scientism, colonialism, capitalism, racism and moralism. In minority countries (usually referred to as ‘developed’ nations), the role of water as a resource, and aesthetic and cultural views of its place in society, changed dramatically during the 19th century. Water-use practices became a technology for moralising and racialising discourses in Western nations and their far-flung colonial territories, as new, water-intensive personal hygiene routines became the marker of particular Western figurations of ‘civilization’ (Gandy, Reference Gandy2002, Reference Gandy2004; Goubert, Reference Goubert1989; Illich, Reference Illich1985). As new discourses of ‘safe’ water emerged (associated with new water practices incumbent upon ‘modern’ citizens), local, place-based practices and perceptions of qualities of different waters were deemed ‘backward’, or ‘uncivilised’ and replaced by a more unified understanding of water defined by a ‘scientific’ analysis of its biophysical properties, although this did not completely displace ‘nonscientific’ views of water (Hamlin, Reference Hamlin2000; Strang, Reference Strang2004). It is clear from this analysis that political agencies of water/watery/watering are never neutral or pure, but always mixed up in complex ecologies of flourishing, starvation, labour, migration, climate, toxicity, sickness, profit (and more) that are unevenly situated, distributed, and experienced.

Such concerns around the politics of water have also figured prominently in recent discussions of the Anthropocene epoch (Vörösmarty, Pahl-Wostl, & Bhaduri, Reference Vörösmarty, Pahl-Wostl and Bhaduri2013). Emerging from the geological sciences in the early 2000s, the Anthropocene refers to a new era in which human activity has become a geological force that is irreversibly altering the Earth’s functioning at planetary scale (Crutzen, Reference Crutzen2002). Water is crucially implicated in the most pressing environmental emergencies caused by human activity, including the onset of anthropogenic climate change and the mass extinction of non-human animals. Steffen et al. (Reference Steffen, Persson, Deutsch, Zalasiewicz, Williams, Richardson and Molina2011) argue that what has been called the ‘great acceleration’ of human enterprise has adversely exploited Earth resources and biosphere to the point of risking all life. Such exploitation is strongly linked to the commodification of water and water bodies that have been treated as financial resources to sustain economic growth (Meybeck, Reference Meybeck2003). The financial and governmental control of water quality and distribution is a primary factor in determining who (and what) gets to survive in the Anthropocene. Despite what would appear to be the Earth’s vast water resources, there remain an estimated one billion people living in the world without access to clean, drinkable water, a figure that is certain to rise with the increasing severity of global climate change (Best, Reference Best2017).

In an attempt to address the adverse effect of humans on environmental emergencies associated with the Anthropocene, Steffen et al. (Reference Steffen, Persson, Deutsch, Zalasiewicz, Williams, Richardson and Molina2011) refer to the development of a forward-thinking ‘planetary boundary’ framework with the goal of outlining critical boundaries for limiting human consumption, population growth, and destabilising impact on Earth’s climate and ecosystem processes. Such calls for a model of ‘planetary stewardship’ propose new forms of environmental care, management and governance based on technoscientifically determined ecological boundaries that take into consideration the ‘carrying capacities’ of the Earth system as a whole. However, these visions of planetary stewardship have been widely criticised by Indigenous, posthumanist and decolonial scholars for constructing a homogenising figure of a universal ‘humanity’ equally vulnerable and equally responsible for environmental crises (McCoy, Tuck, & McKenzie, Reference McCoy, Tuck and McKenzie2018; Nxumalo & Cedillo, Reference Nxumalo and Cedillo2017).

The urgency of responding to these contested political knottings of water pushes thinking about the planetary crises of carbon, of capital, and of climate, along with the micropolitical crisis of ethics and aesthetics, which is a fundamental crisis of how to live under conditions of environmental emergency and socio-ecological precarity. How might thinking with water/watery/watering contribute to an alternative ethics of life-living, and indeed, to a therapeutics for living on a damaged planet? What other forms and expressions of life might be encountered by thinking with the ephemeral, fluid depths of bodies of water as living archives of historical affect and feeling? Responding to the discussion above and pivoting from the walkography, the article now makes an ontological and epistemological (re)turning, as it moves with/through an aesthetic and purposeful working of concepts of watering and asks, through visual arts and exegetic practices, how the assemblage of water/watery/watering can be exercised and assembled through transcultural arts-based modalities in order to build further conceptual knottings. Here, the verb watering is both a departure from and a definition of putting water/watery to work, through arts-based means. The (re)turning commences with an exegetic artists’ statement, known here as a waterline.

waterline: a (re)turning, a watering Footnote 3

In local stories connected to watery spaces, bodies and places, an image can be a map that inheres traces of the transcultural relations of unceded territory and offer some meaning as to what it means to be in a settler-colonised place today. Theories of purity and danger (Douglas, Reference Douglas2003) demonstrate how pollution, separation, sensitivity and classification infuse current education about urban waterways. Here, inefficient mapping (Knight, Reference Knight and Hodgins2019; Wood, Reference Wood2013) is played for its theoretical capacity regarding flowing material, and to draw out some partial, contingent, temporal and spatial inefficiencies of knowing and representing Wurundjeri Country. Ingold’s (Reference Ingold2007) consideration of and thinking with lines as threads and traces, and the surface’s capacity to restore social lives (Ingold, Reference Ingold2017 p. 105) infiltrate local stories, along with Jane Bennett’s (Reference Bennett2010) theory of vibrant matter).

The artful, watery stories as captured in the artwork (see Figure 1) involve local spaces, bodies and places that recognise the transcultural relations involved in mapping Wurundjeri Country (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) inefficiently (Knight, Reference Knight and Hodgins2019). The stories reflect water’s endless theoretical capacities to permeate cultural, ecological, political and educational spaces.

Figure 1. Baradian ethico-onto-epistemology and the waters of Wurundjeri Country.

The etching once named ‘Writing from the wings’ by Angela V. Foley (Figure 1), is a composition through, with and of water, a coming together with a multiplicity of mappings and locatings. Making the work began by Foley wearing a necklace made by a Wurundjeri woman with whom she worked. Later there were sketches, a design plan, time in a printing studio, and a step-by-step action plan before marking and colouring the etching plate (Reference Foley, Malone, Truong and GrayFoley, 2017, p. 223). Later the little scratches for the bead shapes linked with the creek marks from the first plate and created a certain unity of marks and storying of creeks, a Golden Sun Moth necklace and tussocks in the grasslands.

Making the print involved water in many discreet phases of the production process. The cloth paper sheets were soaked the night before to swell the fibres for later reception of the inked marks. Absolute sheet saturation was safeguarded by plastic wrap to resist atmospheric drying. Setting up the printing press meant a test run with wettened newspaper to assess the evenness of pressures and to ‘condition’ (dampen) the woollen blankets which cushion the print materials. Without a water mark to ‘read’ the precision of the set-up there could be an uneven or weak imprint, or worse, torn paper.

In this way, the image deeply maps cultural water as a form of Richardson’s (Reference Richardson2014) schizocartography that ‘challenges dominant representations and power structures’ (p. 140).

The etched object, a bead necklace, floats over Merri and Curly Sedge Creeks, above the grasslands of Galgi ngarrk (Woi wurrung for backbone) in Melbourne. The decision to have it appear to hover (while on the surface of the paper) required a printed ordering of the two etched plates to manage the impression of perspective. Foregrounding the floating image of the necklace was a deliberate act to respect a Wurundjeri necklace-maker and her Golden Sun Moth story from Galgi ngarrk, which she told by making beaded necklaces. The foregrounding was a conscious act intended to embed respect for Wurundjeri Country through cultural storying with water. In this way, the ordering of material by a non-Indigenous print maker (Foley) in the production and design of a visual narrative produced an ethics of intercultural practice with memories, mis-rememberings, encounters with people, animals and place, losses and exaggerations.

While the surfaces and lines within the story move diffractively to portray and provoke stories with water of life and sovereignty, the ethics of the image is not the end point in this theoretical playfulness with watery environs. Foley’s own Golden Sun Moth learning is the story of how an object prompted fresh recognition of the confluence there of Merri and Curly Sedge Creeks close to suburban Craigieburn. The Golden Sun Moth necklace turned her attention towards imagining this place as Wurundjeri Country and then worked as an inroad to wider appreciation of contemporary Wurundjeri Country.

Mapping the lines of connection continues to expand and includes Foley’s friend’s interest in her study of this story from Wurundjeri Country with the passage for one of the ‘Writing from the Wings’ prints to travel from Wurundjeri Country to Walyalup (Fremantle, Western Australia), situated in Whadjuk Nyoongar Country. Tracing the open-ended lines of connection extends the sense of cultural placemaking by following streams of action and movement.

The integration of ethics during the processual considerations was also ontological because of the many watery becomings related to the creeks, necklace-storying and printmaking. When the necklace plate was placed second in the printing process to ‘float’ over the waterways and grasslands (Foley, Reference Foley, Malone, Truong and Gray2017, p. 223), it was intended to privilege the embedded cultural storying of Golden Sun Moths of Wurundjeri Country.

Such has been the case of to-ing and fro-ing that is integral to the enactment of the ethico-onto-epistemological (Barad, Reference Barad2007) processes entangled in the production of this transcultural work. There is much to-ing and fro-ing among the soaking, dampening, mixing, wetting and drying. Water is continually implicated in the preparation and order of actions with two different coloured plates, the setting up of papers and pulling the heavy wheel of the printing press to exert the correct pressure for the imprint. Another, less tangible product occurs alongside, which is a confluence of ideas and theories of culture, lives and place.

Barad reminds us of the intra-actions of water (Reference Barad2007), and in this case, the intra-actions of artmaking ideas and arrangements — how we act on water (and art) and how it (and art) acts on us — their movements and reflections and diffractions, cause us also to reflect and diffract: as we push, it ripples, it moves, resists, drips wetly, and flows across the surface of experience.

watery/watery/watering: an engagement, an assembling

What arts-based theoretical opportunities come from the shapeshifting body that is transcorporeality of water as a bio-political ethics of water care? In Carter’s (Reference Carter2004) Material Thinking, the researcher is challenged to consider the term ‘creative research’ (p. 9) and create new knowledge as research (Crinall, Reference Crinall2017, p. ix). In engaging and assembling haecceities of watery/watery to work (a watering), we recognise the visual arts and arts-based modes for activating concepts as knotty and knotting (Ingold, Reference Ingold2007, Reference Ingold and Dudley2012, Reference Ingold2015) modalities for thinking-with, towards a process of concept provocation.

There is more work to be done in creating further concepts; however, this article has attempted to knot, tangle and entangle water/watery/watering as both a conceptual assemblage and a constellation of highly situated, aesthetic and sensitive practices. We began by raising questions as a way to position the unfolding of concepts of this paper around posthumanist pedagogies of water, and what such practices might teach (and learn). We then took the concept of water/watery/watering for a walk through a walkography, followed by a discussion around the materiality of water’s extensive properties, intensive qualities, and virtual potencies. After this, we turned to the elaboration of politics, personhood and commodification of water/watery/watering, drawing on posthumanist theoretical perspectives to challenge dominant, and often unquestioned, logics of extraction within contemporary environmental domains. Finally, we found ourselves necessarily (re)turning to the intimate and intricate movements of aesthetics, taking shape as both transcultural therapeutics and a beautiful act of resistance in the printmaking process of co-author Angela Foley.

In closing, we linger with arts-based practices such as Foley’s and the walkography as a way of teasing out some of the subtle implications for a posthumanist environmental education that is responsive to the concerns raised in this article. These practices suggest that environmental education can no longer be about saving the planet, learning science better, or connecting with nature, untainted by the violence of history, colonisation, politics, commodification and pollution. Such universal aims for environmental education may have, quite simply, run out of breath in what has been named the era of the Anthropocene. They fail to do justice to the specificity of ecological lives irreparably damaged, exploited, lost and dispossessed, including those of watery bodies taking the shape of person, animal, plant, river, ocean, lake, creek and sea. What if we were to take the arts-based processes of intra-active thinking- and making-with-water as an example of what posthumanist environmental education might look like?

It is clear in Foley’s diffractive account that this is in no way an easy process. Rather, the process is painstaking, inefficient and yet exacting in its attention to the ethical and aesthetic entanglements and problematics encountered in each fold of the process. We can read this less as a dialectic or a didactic between Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledges, and more as a differential relation, a folded relation of difference in and for itself (Deleuze, Reference Deleuze and Patton1994). Yet it is exactly this attention to difference as relational togetherness that compels careful political questions. Who speaks and who listens? Who makes and creates? Whose stories and concepts come to matter? Who gets to document or map them? Which layer is pressed first? Which is pressed last? Which layer gets to float over the other? Which method is privileged?

There is no predetermined protocol for how to do such work in environmental education, nor is there an a priori set of agreed-upon concepts, languages, or values for transcultural intra-action among its participants. There is risk of ethical and aesthetic failure at each juncture of the process, a vulnerability that is shared through mutual relations of care. We suggest that these are risks worth taking, worth getting wrong, and then sometimes maybe right, to-ing and fro-ing. Perhaps it is within these minor junctures of risk and negotiation that new concepts for environmental education might begin to take shape, concepts of mutual relation that give watery breath to the unnameable, the unknowable, the unmappable zones of posthuman ecologies.

Alexandra Lasczik (formerly Cutcher), is Associate Professor Arts and Education, and Deputy Dean Research and HDRT, in the School of Education, Southern Cross University. She is currently Deputy Leader of the Sustainability, Environment and the Arts in Education Research Cluster (SEAE). Alexandra’s recent work explores movement specifically walkography and arts-based research.

David Rousell is a Senior Lecturer at RMIT, Melbourne, Victoria. He is also an Adjunct Research Fellow in the Education and Social Research Institute at Manchester Metropolitan University, Biosocial Research Lab and Adjunct at Southern Cross University. David’s recent research and artistic projects have focused on creating multi-sensory and immersive responses to climate change in collaboration with schools, universities, and community arts organisations.

Yaw Ofosu-Asare is a PhD candidate in Education interested in design education through the lens of postcolonialism and culture as tools for philosophically analysing cultural, political and social-economic development. Before commencing his studies at the Southern Cross University, Yaw studied at KNUST and UEW in Ghana.

Angela V. Foley is a PhD candidate at Western University Sydney.

Katie Hotko received First Class Honours in 2016 and is now in her final year of her PhD study, exploring primary teachers’ self-beliefs about creativity, and how these beliefs effect their teaching of the Visual Arts. Katie is a self-taught artist who is passionate about making the Visual Arts accessible to all people.

Ferdousi Khatun completed her PhD in the School of Education, Southern Cross University. It explores Bangladeshi young people’s ecoliteracy in postcolonial times. She has previously worked as a research assistant and casual academic in the School of Education, SCU and has extensive past experience as a teacher, environmental educator and botanist in Bangladesh, Nepal and Australia.

Marie-Laurence (Mahi) Paquette is a PhD Candidate at Southern Cross University, Australia. Her current projects, professional and academic, are designed to expand the scope of understanding of social change associated with planetary conditions and the Earth system as a whole. Mahi is passionate about addressing humanity’s challenges.