Introduction

According to the family systems theory, a person's disease can affect the entire family (Broderick, Reference Broderick1993). The diagnosis of a life-threatening disease, such as breast cancer, can significantly impact all family members, particularly the diagnosed individual's partner, thereby affecting the couple's relationship (Dorval et al., Reference Dorval, Guay and Mondor2005; Manne and Badr, Reference Manne and Badr2008). In a nationally representative random-digit telephone survey of noninstitutionalized adults aged 18 years or older in the USA, a total of 14.1% of cancer survivors aged 20–39 years were divorced, compared with 9.6% of controls (Kirchhoff et al., Reference Kirchhoff, Yi and Wright2012). Divorce was suggested as an independent prognostic factor for survival among breast cancer patients (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Song and Ouyang2015; Li et al., Reference Li, Gan and Liang2015; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Yang and Xu2016). In a recent cohort study, involving patients above 20 years who were diagnosed with stages I–III primary breast cancer and who received surgical treatment from 1992 to 2015, the divorced group (N = 3,044) exhibited a higher risk of breast cancer-specific death (HR 1.11, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.18, p < 0.001) and all-cause death (HR 1.27, 95% CI: 1.22, 1.32, p < 0.001) than the group that remained married (N = 17,623) (Ding et al., Reference Dorval, Maunsell and Taylor-Brown2021).

Although divorce affects many aspects of a couple's life (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Song and Ouyang2015; Li et al., Reference Li, Gan and Liang2015; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Yang and Xu2016; Ding et al., Reference Ding, Ruan and Lin2021), only few empirical studies have found an association between divorce and quality of life (QoL). Previous studies have provided information on marital status soon after the diagnosis of breast cancer, and thus may not reflect the dynamic changes in long-term survival populations or account for marital status changes before or after the cancer diagnosis (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Ruan and Lin2021). Moreover, research on the relation between marital status and health outcomes among cancer patients has generally used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer database or other national surveys, which elicited limited information on QoL (Abdollah et al., Reference Abdollah, Sun and Thuret2011; Aizer et al., Reference Aizer, Chen and McCarthy2013; Ding et al., Reference Dorval, Maunsell and Taylor-Brown2021). Thus, this study aimed to identify factors associated with divorce after breast cancer diagnosis and examine its impact on QoL.

Methods

Participants

We used cross-sectional survey data collected to evaluate factors associated with QoL among breast cancer survivors after the completion of their active cancer treatment. The study participants were recruited at breast cancer outpatient clinics of the Samsung Medical Center in Seoul, South Korea, from November 2018 to April 2019. Survivors aged 20 years or above were eligible if they were recently diagnosed with breast cancer, had received curative intent surgery, and had completed active treatment without cancer recurrence at the time of the survey (N = 4,366). Since this study sought to identify factors associated with divorce after cancer diagnosis, we only included women who were married at the time of diagnosis (N = 3,612). We excluded participants who were widowed post-diagnosis or did not mention their marital status.

Trained researchers explained the survey's purpose and procedure to the participants. After collecting informed consent from the participants, they were asked to complete the questionnaire. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Samsung Medical Center (SMC: 2018-03-099).

Measurement

The participants indicated their current marital status at the time of diagnosis as “single,” “married,” “widowed,” or “divorced.” The responses were grouped into two: “maintaining marriage” and “being divorced.”

To identify factors associated with divorce, we collected socio-demographic information, such as education level, working status at diagnosis, and the number of children at the time of diagnosis, as well as marital status, cancer stage, and psychiatric problems at the time of diagnosis, and anticancer treatment (type of surgery, reconstruction, chemotherapy, radiation, hormone therapy, and targeted therapy) using questionnaires and electronic medical records.

To measure QoL, we used the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30) and breast cancer-specific module (BR23), which has been translated into Korean and validated (Yun et al., Reference Yun, Bae and Kang2004). The EORTC QLQ-C30 and BR23 questionnaires were scored according to the EORTC scoring manual (Fayers et al., Reference Fayers, Aaronson and Bjordal2001), and the data were linearly transformed to yield scores from 0 to 100, where a higher EORTC score represented a better level of global health status and functioning.

Statistical analysis

We compared the categorical and continuous variables of maintaining marriage and being divorced survivors using χ 2-tests and t-tests, respectively. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression were used to identify the factors associated with divorce after cancer diagnosis. We also compared the QoL of maintaining marriage and being divorced survivors using multivariable linear regression after adjusting for age, education level, stage, surgery type, and history of cancer treatment (chemotherapy, radiation, hormones, and target therapy).

All significance tests were two-sided, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All data analyses were performed using STATA version 15 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Among the 3,612 eligible survivors, we excluded 37 who were widowed (n = 23) or did not report their marital status (n = 14). Finally, 3,575 survivors were included in the analysis.

The mean age (SD) at the time of diagnosis was 48.3 (8.6) years, and 43.2%, 32.9%, and 14.7% were diagnosed with stages I, II, and III breast cancer, respectively (Table 1). Among the survivors, 1.1% (n = 40) were divorced post-diagnosis. At the time of diagnosis, compared to survivors who maintaining marriage, those who were being divorced were likely to be younger, have less than high school education, be employed, and be diagnosed with an advanced stage of cancer. While being divorced survivors were also more likely to continue to work, their monthly family income was lower than that of survivors who maintaining marriage. Furthermore, being divorced survivors were more likely to be smokers and alcohol consumers than maintaining marriage survivors (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics and treatment modalities of breast cancer survivors

Bolded numbers represent statistically significant associations (P < 0.05).

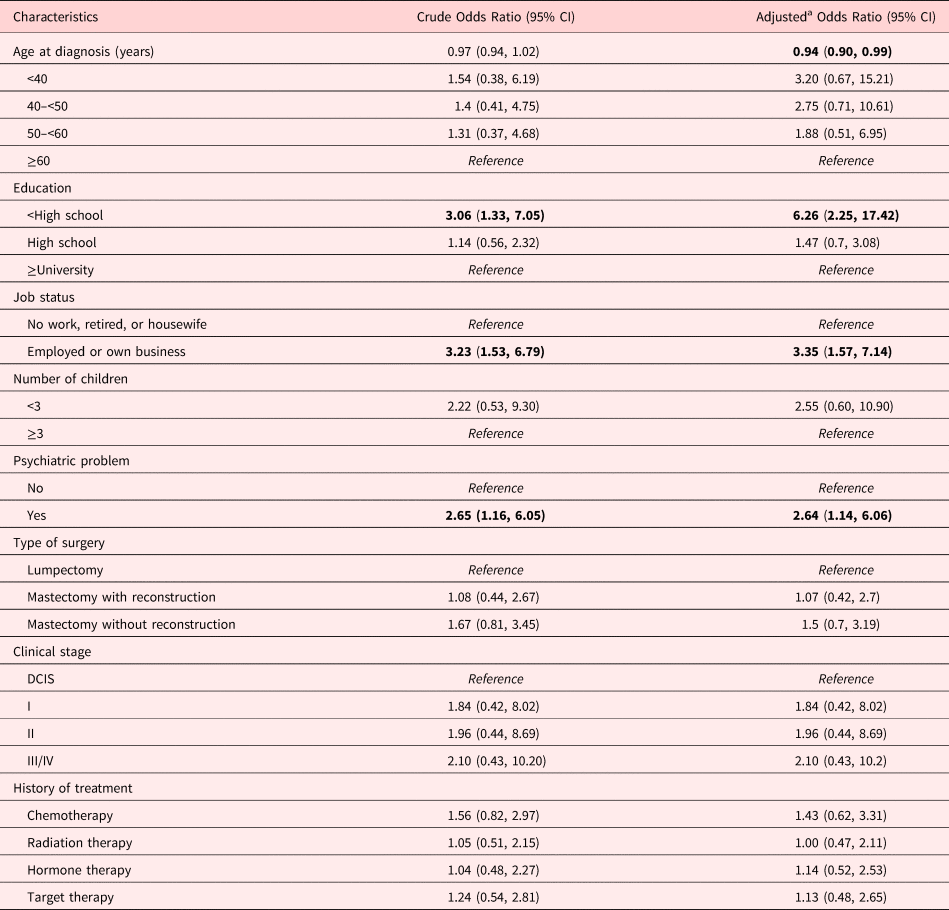

In the multivariable-adjusted model, the factors of younger age, lower education (≤ high school odds ratio [OR] = 6.26; 95% CI = 2.25, 17.42), employed at diagnosis (OR = 3.35; 95% CI = 1.57, 7.14), psychiatric problems (OR = 2.64; 95% CI = 1.14, 6.06), and diagnosed with advanced stage of cancer were associated with risk of being divorced (Table 2).

Table 2. Odds ratio (95% confidence intervals) for being divorced pertaining to factors at diagnosis

a Adjusted for age at diagnosis, education, and clinical stage.

Bolded numbers represent statistically significant associations (P < 0.05).

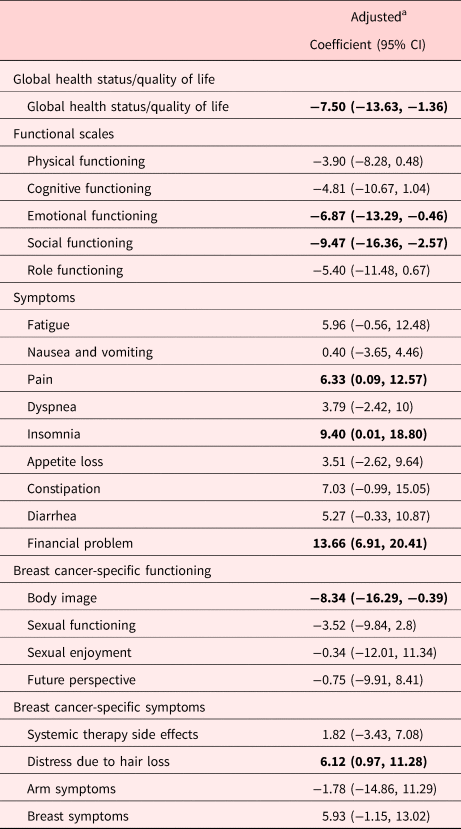

Being divorced survivors had significantly poorer QoL (Coefficient [Coef] = −7.50; 95% CI = −13.63, −1.36) than survivors who maintaining marriage. They also exhibited poorer emotional functioning (Coef = −6.87; 95% CI = −13.29, −0.46), social functioning (Coef = −9.47; 95% CI = −16.36, −2.57), and body image (Coef = −8.34; 95% CI = −6.29, −0.39) than survivors who remained married, and reported experiencing more symptoms, including pain (Coef = 6.33; 95% CI = 0.09, 12.57) and insomnia (Coef = 9.40; 95% CI = 0.01, 18.80), and were more upset by hair loss (Coef = 9.40; 95% CI = 0.01, 18.80) than survivors who maintaining marriage. Additionally, being divorced survivors experienced greater financial difficulties (Coef = 13.66; 95% CI = 6.91, 20.41) than survivors who maintaining marriage (Table 3).

Table 3. Association between being divorced and quality of life

a Adjusted for age at diagnosis, clinical stage, education, survival years, type of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, hormone, and targeted therapy.

Bolded numbers represent statistically significant associations (P < 0.05).

Discussion

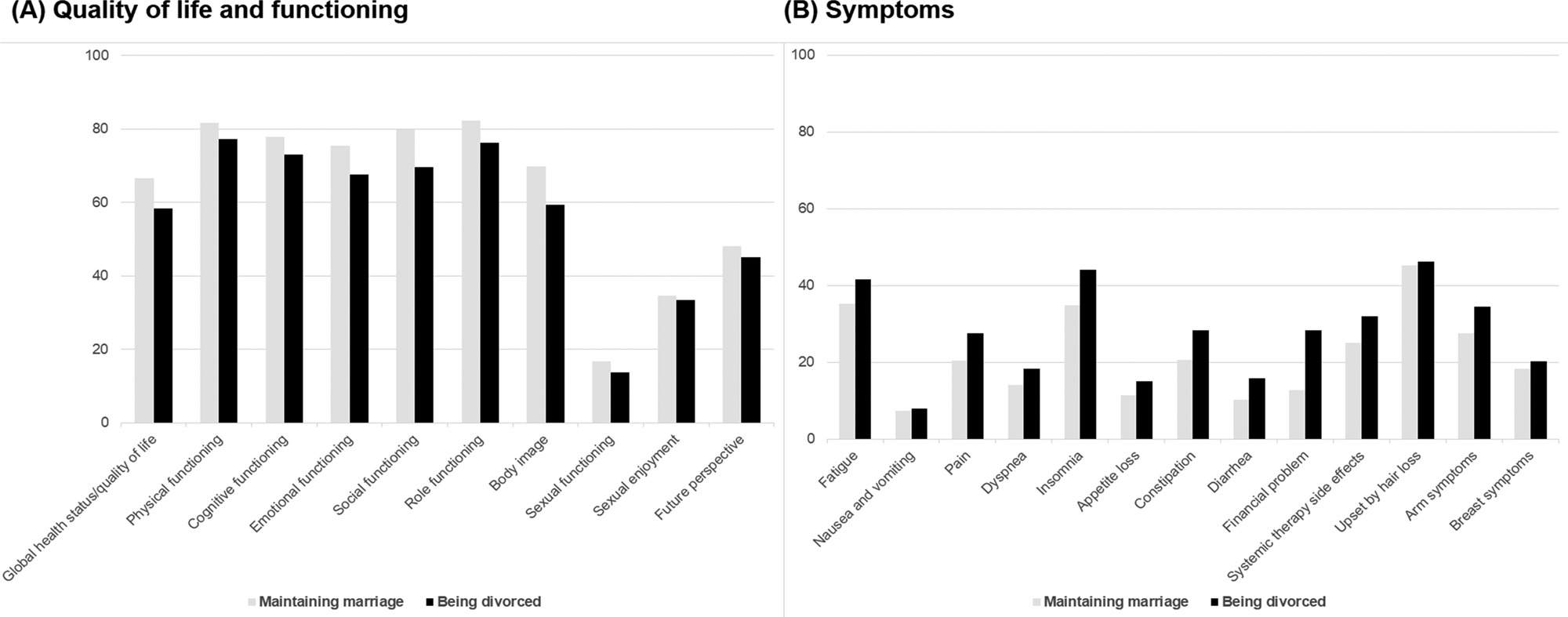

In our study, approximately 1% of married breast cancer survivors experienced divorce after cancer diagnosis. Younger age, lower education, and being employed at diagnosis were associated with risk of divorce. Being divorced survivors had significantly lower QoL, social functioning, and body image than those who maintaining marriage. They also experienced more symptoms, including pain and insomnia, and greater financial difficulties (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Quality of life, functioning, and symptoms score of the being divorced group. Scores range from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicate better general health status/quality of life and better functioning but more symptoms.

The divorce rate among the participants in this study was approximately 11.1/1,000, which is much higher than the figure in the general population of Korea of 2.1/1,000 persons (https://www.statista.com/statistics/642501/south-korea-divorce-rate/). In a Swedish register-based study, women diagnosed with breast cancer showed a significant increase in the risk of divorce at almost 25% (Socialstyrelsen, 2006). In a Turkish study, 3.6% of breast cancer survivors were divorced, higher than the rate in the general population in Turkey (0.159%) (Yildiz and Alagüney, Reference Yildiz and Alagüney2020). It might be hypothesized that a major life event, such as cancer diagnosis, has a considerable effect on the quality of marriage, and that cancer patients thus face an increased risk of divorce (Carlsen et al., Reference Carlsen, Dalton and Frederiksen2007). In addition, the treatment of breast cancer might affect sexual life (Boswell and Dizon, Reference Boswell and Dizon2015) and perceived body image (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Chang and Chang2019), leading to marital disharmony and a higher risk of divorce (Meltzer and McNulty, Reference Meltzer and McNulty2010). However, studies conducted before the early 2000s reported that breast cancer diagnosis and divorce are not associated (Dorval et al., Reference Dorval, Maunsell and Taylor-Brown1999; Carlsen et al., Reference Carlsen, Dalton and Frederiksen2007). A Canadian study conducted between 1984 and 1992 found no difference in the frequency of divorce among patients with nonmetastatic breast cancer from the general population (Dorval et al., Reference Dorval, Maunsell and Taylor-Brown1999). A study that compared the risk of divorce between early stage breast cancer patients who were diagnosed in 1981–2000 and the general population in Finland found that diagnosis at early stages of breast cancer does not pose a risk for divorce (Carlsen et al., Reference Carlsen, Dalton and Frederiksen2007). This finding might be related to feminism and other movements that have substantially boosted women's rights and their ability to leave poor marriages. The improved economic status of women may increase marital stress as women's bargaining power within the household is enhanced (Mammen and Paxson, Reference Mammen and Paxson2000), making divorce a more affordable and acceptable choice for women in an unsatisfactory marriage (Lee, Reference Lee2006). Moreover, rising individualism in globalized and developed Asian economies has helped create a social climate more open to divorce (Jones, Reference Jones2012).

In terms of factors associated with being divorced, younger age was associated with divorce. Swedish and Danish studies also found that younger age at the time of diagnosis was associated with higher risk of divorce (Christoffersen, Reference Christoffersen2002; Carlsen et al., Reference Carlsen, Dalton and Frederiksen2007). Younger patients may be less resilient to the stressors of cancer treatment and recovery and face competing burdens from having young children or lower job security, which are more common circumstances among these patients. For younger cancer survivors, increased emotional and financial burdens from cancer may impact their marriages in ways not seen in other survivor populations (Kirchhoff et al., Reference Kirchhoff, Yi and Wright2012). Lower educational qualifications were also associated with being divorced. As less educated individuals have more limited human capital and fewer socioeconomic resources at their disposal, the consequences of heightened divorce risk and low remarriage rates will certainly have a considerable impact on their life outcomes, because they lack the extra safety net of family support (Cheng, Reference Cheng2016). Furthermore, we found that those who were employed at the time of diagnosis were more likely to be divorced. In fact, a positive relationship has been reported between women's working hours and the number of divorces (Poortman and Kalmijn, Reference Poortman and Kalmijn2002), and the risk of being divorced among working women is 16% higher than among those who do not work (Poortman, Reference Poortman2005). According to previous studies, a wife's employment increases her financial independence, making it easier for her to consider divorce (Poortman, Reference Poortman2005). Furthermore, husbands may more easily consider divorce when their wives are financially independent. From a sociological perspective, wives’ employment might be contrary to traditional role expectations emphasizing women's role as homemakers (Poortman, Reference Poortman2005). In this study, we also found psychiatric problems at diagnosis to be associated with divorce. Mental problems are known to be a strong risk factor for divorce (Christoffersen, Reference Christoffersen2002; Socialstyrelsen, 2006). Psychiatric problems may negatively affect people's ability to maintain marital relationships, which may, in turn, lead to divorce (Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Miller and Jin2011). In addition, there is some evidence of a joint effect of multiple co-occurring disorders on divorce (Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Miller and Jin2011). Thus, patients with mental problems need early intervention to reduce the negative impact of psychiatric problems.

In this study, survivors who were being divorced were more likely to report poor emotional and social functioning than those who remained married. According to the previous study, married patients received more social and emotional support from marriage (Chang and Barker, Reference Chang and Barker2005; Reyes Ortiz et al., Reference Reyes Ortiz, Freeman and Kuo2007; Zhai et al., Reference Zhai, Zhang and Zheng2019). Divorce can also disrupt the social network of survivors, reducing their socioeconomic status and overall QoL (Kornblith et al., Reference Kornblith, Herndon and Zuckerman2001; Lehto et al., Reference Lehto, Ojanen and Kellokumpu-Lehtinen2005), as well as increasing the risk of an unhealthy lifestyle, including increased consumption of alcohol and tobacco smoking. In fact, in our study, divorced survivors were more likely to be smokers and drinkers than survivors who remained married. Unhealthy lifestyles might be associated with lower QoL among being divorced survivors. In our study, divorced patients also had lower QoL and overall health status. Thus, there is a need to proactively provide single and divorced individuals with appropriate social and psychological support.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we were not able to include potential risk factors for divorce, such as satisfaction with marriage. Second, as we did not ask why they were divorced, those who had divorces not related to cancer were included in the group of divorced patients. Third, the results of our study might not be generalizable to other cancer survivors in different settings. Studies investigating the relationship between cancer diagnosis and divorce generally include heterogeneous patient groups with all types of cancer. In a population-based study conducted in the Danish population, no difference was found between survivors other than cervical cancer and the general population in terms of divorce risk (Carlsen et al., Reference Carlsen, Dalton and Frederiksen2007). Similarly, a study of approximately 1.5 million people in Norway found that types of cancer other than testicular and cervical did not affect divorce (Syse et al., Reference Syse, Loge and Lyngstad2010).

With early diagnosis and medical advancements, 93.2% breast cancer patients have survived for more than 5 years (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Kim and Kim2020). On account of their high incidence and survival rates, breast cancer survivors represent one of the largest groups among cancer survivors, and their survivorship care is a vital issue. For an increasing proportion of cancer patients, the disease becomes a chronic disorder, as illustrated by the term “survivorship” (Ayanian and Jacobsen, Reference Ayanian and Jacobsen2006). Although their marital relationship is likely to be strained due to cancer diagnosis, some couples with the resources to meet this challenge (Dorval et al., Reference Dorval, Guay and Mondor2005) experience a strengthening of their relationship (Dorval et al., Reference Dorval, Guay and Mondor2005; Hinnen et al., Reference Hinnen, Hagedoorn and Ranchor2008). Thus, identifying risk factors of divorce will ultimately help healthcare professionals ascertain the resources necessary for early intervention.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Samsung Medical Center approved this study (SMC: 2018-03-099). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

All authors give consent to publication.

Author contributions

DK, NK, JC, and SKL conceived and designed the study; DK, GH, HK, JL, HK, SS, JEL, SJM, SWK, and SKL constructed the data; DK, GH, HK, JL, and HK contributed to the analysis; DK, SK, and NK wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning (2017R1E1A1A0107764214).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.