INTRODUCTION

Physicians are responsible for attending to the well-being of their patients, and increasing data suggest that this care should include spiritual care. It has been argued that physicians can, and should, help their dying or suffering patients find meaning, dignity, and hope through recognition of the spiritual dimension of their experience (Puchalski et al., 2004). Spirituality can be integrated with the clinical assessment of the patient and does not need to be compartmentalized from other medical treatment. When available, spiritual care can be a multidisciplinary approach utilizing chaplain services, local clergy, physicians, psychologists, nurses, social workers, and other ancillary staff (Meador, 2004; National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2004). In some situations the physician establishes a longstanding relationship with the patient and their family. In these instances, patients may prefer to discuss personal beliefs with their physician whom they already know rather than the hospital chaplain (Lo et al., 2002). Although physicians should focus their time on the treatment of disease and are not professional spiritual counselors, they can still maintain the primary responsibility for coordinating patient care and be attentive to spiritual needs

A common goal for the dying patient, family members, and the health care provider is for a “good death” that frames loss in the context of life legacy (Block, 2001). A good death includes minimal suffering, absence of undesired artificial prolongation of life, involvement of family, resolution of conflict, and attention to spiritual issues. Dying patients desire a supportive and respectful environment that supports their hope for positive spiritual elements such as prayer, a review of life meaning, and a remembrance of their contributions to society (Braun & Zir, 2001).

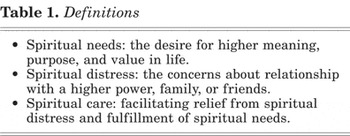

This article (1) describes the terms and definitions that have clinical utility in assessing the spiritual needs of dying patients, (2) reviews the justifications that support physicians assuming an active role in addressing the spiritual needs of their patients, and (3) reviews clinical tools that provide physicians with a structured approach to the assessment and treatment of spiritual distress. Spiritual care is important because unmet spiritual need may lead to distress (Table 1). This article also presents a framework for understanding and managing spiritual crises at the end of life, whether or not the patient or physician is a member of an organized religion.

Definitions

When attempting to define spiritual distress, it is important to first clarify the lexicon that describes issues relating to spirituality, faith, and religion.

RELIGIOSITY

Religion may be defined as a way of perceiving life meaning and higher purpose through a codified philosophy, shared doctrine, and community worship (McKee & Chappel, 1992; Bessinger & Kuhne, 2002). In this respect, religiosity can be viewed as the extent to which an individual engages in their belief, both from internal faith and external practice (Levin & Schiller, 1987).

FAITH

Many definitions of faith and hope have been posited. Two clinically useful definitions describe hope as the “expectation of something good,” and faith as an “assured confidence” that what is hoped for will actually happen. For many patients, faith gives comfort to suffering endured through hope for relief (Puchalski, 2002).

SPIRITUALITY

Spiritual individuals believe their life has a purpose, but do not necessarily participate in established organized belief practices. Viewing spirituality as the patient's defined overall meaning of life creates a broader construct for the physician to support those with diverse religious belief systems (Hardwig, 2000). This universal approach reduces potential conflict and decentralizes the discussion from specific religious practices (Walter, 2002). Although formal religious ceremonies can be a part of spiritual care, so is listening with an open heart to a patient's concerns.

SPIRITUAL NEEDS

The physician should anticipate spiritual needs and be sensitive for patient comments that indicate their condition. The imminence of death may trigger a need for hope, connection, and purpose. Patients express spiritual need with discernible cues such as fear, despair, feeling useless, feeling isolated, and lack of confidence. In contrast, those maintaining spiritual well-being project inner peace, hope, ambition, individuality, and connection within community (Murray et al., 2004). Through attentive listening and discussion, the clinician is able to ascertain these inner qualities.

It is not surprising that spiritual resources are a primary means of coping with suffering and death (Born et al., 2004). The vehicle for spirituality among the religious is typically defined by the belief and practices of their affiliated organization. Cancer patients with a defined religious faith describe fewer unmet psychosocial needs (32%) than those without a self-described belief system (52%; McIllmurray et al., 2003). It can be inferred that more spiritual assistance is needed to help those who do not have access to the resources of established spiritual organizations and the psychological and social support they offer. This is one reason to investigate patient involvement in a spiritual community or support network.

Another common spiritual need is for both patients and their families to find an explanation for suffering and illness. Sometimes, this leads to a reevaluation process of their meaning for life. The spiritual beliefs of family members enable them to make sense of the loss of a loved one. When medical care cannot prevent death, new insight into beneficial relationships and life meaning brings relief (Davis et al., 1998). The physician can contribute to this process by facilitating discussion with patients and families about what gives them meaning in life.

One way that spiritual beliefs bring solace is through creating a framework for understanding death and directing avenues for hope. The dying are challenged with finding meaning in life and acceptance of terminal illness and many find reassurance through a belief in continued existence after physical death (Marrone, 1999). Patients who believe in an afterlife have been reported to exhibit less hopelessness, decreased desire for hastened death, and fewer suicidal ideations (McClain-Jacobson et al., 2004). This finding suggests that belief in an afterlife represents an established sense of life purpose and ultimate destination that is beneficial for coping through suffering. Physicians can easily inquire about patient beliefs of an afterlife to understand their perspective.

The physician's proper attention toward spiritual well-being at the end of life promotes a positive patient outlook. Reframing terminal illness in the context of an underlying spiritual meaning promotes inner peace (Breitbart et al., 2004). In the experience of some palliative care practitioners, patients may also need to seek forgiveness for strained relationships with people in their lives or their higher power (Kellehear, 2000). Because dying patients may become increasingly vulnerable and dependent on caregivers, it is important for the physician to help them actively participate in identifying and working through their spiritual needs. Asking patients about how they would like this issue to be addressed advances their autonomy.

SPIRITUAL DISTRESS

Although the description of spiritual needs can be found in the literature, consensus nomenclature for the unrest evoked when these are unmet remains elusive. Breitbart (2003) describes a broad construct of despair at the end of life that includes desire for hastened death, hopelessness, suicidal ideation, loss of meaning, loss of dignity, and demoralization. Death distress is a similar construct incorporating death anxiety and death depression (Chibnall et al., 2002). These terms overlap as they pertain to the spiritual dimension of the patient's end-of-life experience. Therefore, it may be postulated that unmet spiritual needs can lead to a spiritual distress having as its components elements of both end-of-life despair and death distress. Attempts to clarify the construct of spiritual distress describe a disruption of connection, hope, faith, meaning, and peace (Sumner, 1998; Villagomeza, 2005). Ambiguities of its defining characteristics impede clinically addressing patient distress (Kristeller et al., 1999).

Spiritual distress leads to a negative end-of-life experience. In contrast, spiritual well-being contributes to the overall quality of life for terminally ill patients (Thomson, 2000). Lower scores for spiritual well-being in those with incurable illness associate with higher scores for measures of end-of-life despair such as desire for hastened death, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation (McClain et al., 2003). Composite scores of bio-psycho-social-spiritual distress are associated with disturbing spiritual feelings such as abandonment (Hills et al., 2005). The physician should be attentive to distress on the patient's spiritual journey that can lead to measurably diminished indicators for quality of life.

Spiritual distress both includes and has elements distinct from depression. In a prospective survey at a palliative care hospital, the desire for hastened death was associated with depression—however, hopelessness was also an independent and unique contributor (Breitbart et al., 2000). Death distress correlates with lower spiritual well-being, more depressive symptoms, and less perceived physician communication (Chibnall et al., 2002). This suggests that physicians' efforts to discuss spiritual issues with their patients might be efficacious for depressive symptoms as well as providing other independent benefits.

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF SPIRITUAL DISTRESS

If spiritual distress is identified, the physician can provide assistance through both empiric patient-driven and evidence-based spiritual care. By approaching spiritual care in open generalities, patients formulate their own personal application. Spiritual care is individual and patient centered and does not require reference to any particular faith (Gordon & Mitchell, 2004). Physicians respond to the spiritual concerns of their patients to avoid imposing their own viewpoints (Derrickson, 1996; Rumbold, 2003). This includes respecting patients' desire for specific religious traditions and rituals. By supporting patient autonomy, the physician maintains therapeutic neutrality and avoids injecting spiritual concerns that the patient does not acknowledge.

By approaching spirituality as a more universal search for life meaning, the concept of spiritual distress is understandable across cultural and religious lines. Some terminal cancer patients in Japan derive spiritual meaning from family cultural traditions and experience distress from sorrow for burdening loved ones, an inability to be useful, loneliness, and the undesirable prolongation of suffering. These concepts of distress separate into categories of relationships with others, self-expectations, and a graceful death (Kawa et al., 2003). Spiritual caregivers from Jewish, Christian, Hindu, Muslim, and Buddhist backgrounds find a common ground across faith and culture by affirming the unique value of every patient (Wright, 2002). Although the organized vehicles of spirituality vary by culture, searching for life meaning and the realities of distress when faced with loss is a shared human experience approachable in generalities for patients to comfortably express their own specific concerns.

A resource in JAMA from the working group on religious and spiritual issues at the end of life is a practical guide for spiritual care. It details active listening and supportive dialogue to help patients work through their existential difficulties and find peace. If patients develop interest in the beliefs of their physician, a practical diverting statement is, “I'd like to keep the focus on you rather than me.” Important goals for the physician are clarifying spiritual needs, connecting with areas of spiritual distress, aligning with patient hopes, and mobilizing supportive resources (Lo et al., 2002). This expert advice builds a framework to begin understanding spiritual crises.

Additional available tools help physicians confidently and efficiently manage spiritual distress in their patients. Spiritual concerns should be periodically assessed because of their dynamic nature (National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2004). A useful instrument is the “Living Well Interview” to help physicians conduct open-ended discussions allowing patients to express their values and make care decisions. The interview consists of 10-items such as, “Who or what sustains you when you face serious challenges in life?” and, “Do you have any religious or spiritual beliefs that help you deal with difficult times?” (Schwartz et al., 2003). Puchalski describes a spiritual history with the acronym FICA for a patient-centered approach to explore the importance of beliefs, faith community, and their intersection with health care (Table 2) (Puchalski, 2002).

Spiritual history (FICA; Puchalski, 2002)

A spiritual discussion informs and provides a good opportunity to bring up the issue of the patient's advance directives. Spiritual values and beliefs often guide a patient's end of life wishes (Puchalski, 2002). One study reports that about half of patients claim their religious beliefs would influence end-of-life decisions, and 94% indicate that they would like their physician to inquire about their beliefs (Ehman et al., 1999). These findings underscore the clinical relevance of spirituality and the desire for patients to share their beliefs and highlight the importance of physicians addressing spiritual distress with their patients.

Patients react differently to terminal illness depending on their background and prior spiritual experiences. Some will reevaluate their beliefs and others will not desire altering preexisting views or seeking spiritual support in new ways (McGrath, 2003). Breitbart has made significant contributions in defining appropriate interventions at the end of life to help patients searching for vehicles of spiritual expression and life meaning in religiously neutral concepts of love, art, humor, nature, or work (Greenstein & Breitbart, 2000; Breitbart, 2002, 2003; Breitbart et al., 2004). This approach to spiritual care can have universal appeal and allow patients to find their own specific applications. A similar intervention consisting of facilitated psycho-social-spiritual group discussions reduces depressive symptoms, decreases feelings of meaninglessness, and increases spiritual well-being (Miller et al., 2005). For those already engaged in a religious belief system, the most rewarding source of spiritual care will likely arise from their existing support network.

There may yet be an additional patient group in which people are undecided about their current beliefs yet interested in reevaluating their personal concept of spirituality through the paradigms of traditional world religions. Designing an intervention to help this subset of the population could build on existing curriculums to create a neutral framework for spiritual discussion. Patients could then conduct self-directed reviews of the basic beliefs, writings, and prayers from major world religions such as Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Sikhism. This would promote self-efficacy through exploration, group discussions, and personal readings. Patient reexamination and reflection on their beliefs in light of these discussions may bring personal clarity to spirituality and provide new opportunities for expression and community.

CONCLUSION

Physicians' roles as healers requires attention to the spiritual journey of their patients when no curative treatment is available (Sheehan, 2000). Recognition of the spiritual dimension of the human experience broadens the avenues of compassionate medical care and is not limited by culture or religion. The physician can be in tune to their patient's spiritual needs, attentive to the possibility of spiritual distress, and prepared to empathetically respond. Although structured models are being developed to assess and respond to our patients' spiritual distress, not infrequently our patients will only request for their physicians to be present and listen as fellow travelers on their journey through illness toward death.