The discipline of political science in CEE countriesFootnote 1 has traveled a long way during the post-communist transition, having shifted—not unlike the famous Polanyi pendulum (Reference Polanyi2001)—from the political subordination to the state authorities to the increasing reliance on the market forces. The recent establishment of the grant system, with its inherent market-oriented logic in the CEE region, is arguably the primary gamechanger in the academic world since the early 1990s. It disrupted traditional norms and values as well as work patterns of the university community. The deeply entrenched set of customs regarding political science academic work—including the preference for single authorship instead of collaborative work, long monographs rather than journal articles, and locally oriented publications instead of internationally recognizable contributions—has been decimated by the grant system and third-party funding.

The recent establishment of the grant system, with its inherent market-oriented logic in the CEE region, is arguably the primary gamechanger in the academic world since the early 1990s.

The growing pressure to obtain external funding for research has resulted in many benefits for political science. Grant funding—now perceived as an essential element of a competitive track record—helped scholars to learn how to raise interest among nonacademic stakeholders, explore a studied topic from different angles, and better identify policy-relevant aspects of their research. Disconcerting to many people, the rampant competition for external funding put an end to the sheltered local circle of knowledge production, forcing scholars to care about international visibility of their work and to compare their academic record with their colleagues in other countries. Among the EU member states and associated countries, this competition is fostered by the European Research Council (ERC), a leading research agency established by the European Commission in 2007.

The ERC’s self-declared mission is to provide “attractive long-term funding, awarded on the sole criterion of excellence, to support excellent investigators and their research teams to pursue groundbreaking, high-risk/high-gain research” (European Research Council 2020a). As in many other granting institutions, the percentage of the ERC budget allocated to social sciences and humanities is the lowest of all funds distributed (i.e., about 17%). Nonetheless, the availability of such attractive and long-term funding for political science projects (i.e., as much as €1.5 million to €2.5 million for a period of five years) is the envy of many scholars outside of the EU, who often complain about continuous cutbacks in academia.

How are political scientists in the CEE faring in the continent-wide competition for the most prestigious grants? To determine what ERC-funded projects indicate about the state of political science in the region, we must break down the ERC data by research domains (European Research Council 2020a). Political science projects are in the second research domain within social science and humanities—that is, institutions, governance, and legal systems (SH2).Footnote 2 What captures our attention first is that political scientists from CEE countries rarely apply. Reviewing only the most popular scheme (i.e., Consolidator) between 2013 and 2020, the Czech Republic submitted a total of nine applications, whereas the United Kingdom submitted 229, the Netherlands 117, and Germany 66. Among the CEE countries, the highest number of applications evaluated by the ERC were from Hungary (11) and Poland (10). Consequently, new EU members from CEE also receive a much lower number of awards. Reviewing 485 ERC-funded grants in the three most popular categories (i.e., Starting, Consolidator, and Advanced)Footnote 3 in SH2 from 2007 until 2020,Footnote 4 CEE countries received only six grants (i.e., 1.2%). The Czech Republic and Estonia were awarded two grants; Poland and Hungary each received one. Compared to all of the disciplines classified as social sciences and humanities (SH), political scientists seem to be less successful than representatives of related fields. In the SH panel, CEE countries received a total of 49 grants of 2,354 (i.e., 2.1%). Combining all of the academic disciplines, CEE countries received 190 grants of 10,785 (i.e., 1.8%).

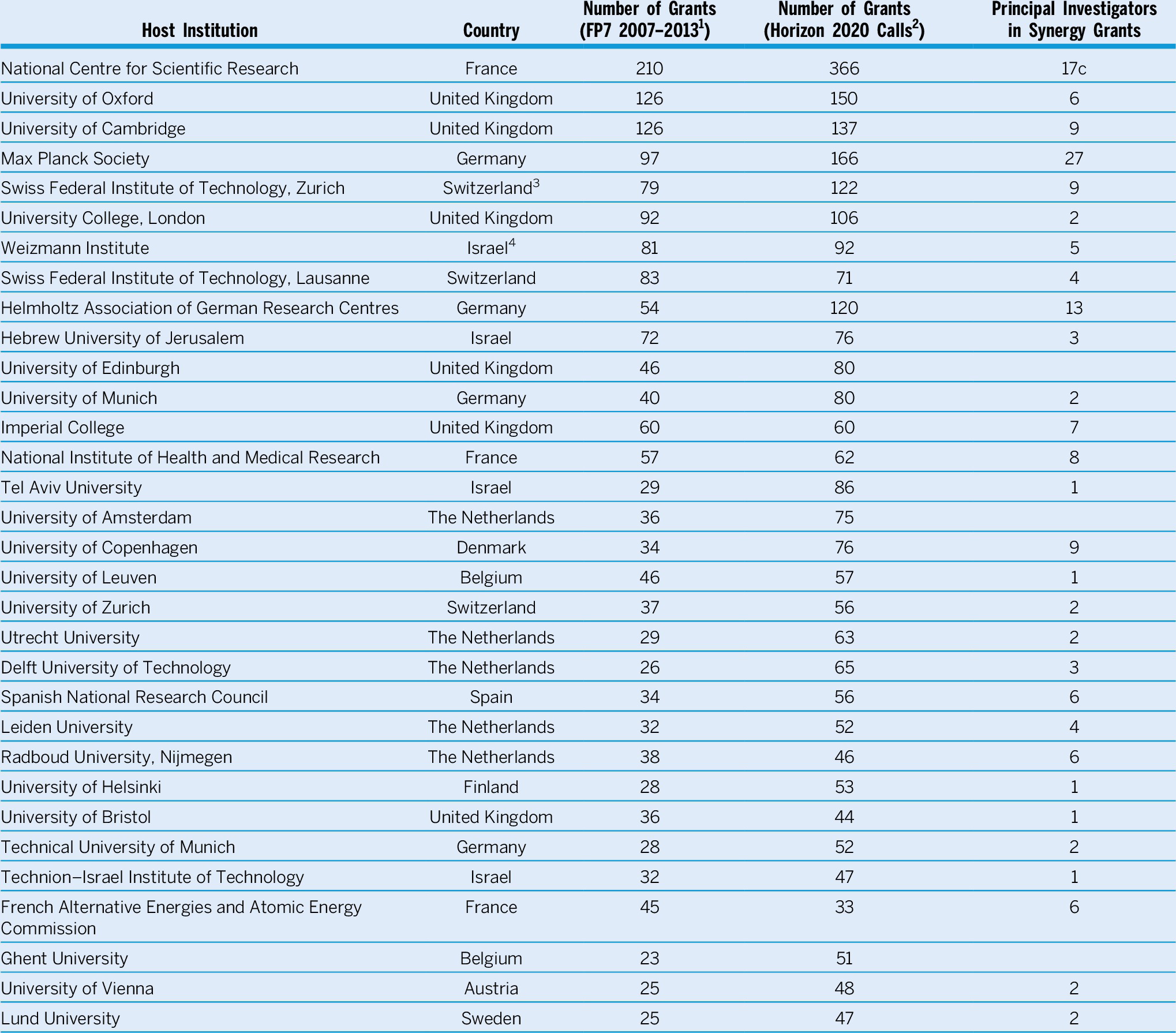

The most recent data for 2020 confirm that CEE countries continue to receive far fewer grants than other European countries. In 2020, the average number of grantsFootnote 5 allocated to CEE countries was only 1.5; the average among non-CEE ERC grant winners was 9.45 (European Research Council 2020a). In 2020, the leading grant receiver among CEE countries was the Czech Republic, with four grants. However, even the highest result in the region pales in comparison with the scores of ERC’s main winners, including the United Kingdom (35 grants), the Netherlands (28), Germany (26), and Italy (15). If we rank all countries from the most to the least successful, then the CEE top performer, the Czech Republic, is only 13th—equal to Portugal—both with four grants. The list in table 1 of 32 top academic institutions hosting ERC principal investigators illustrates an even bleaker picture because not a single one is located in the CEE (European Research Council 2020a). Moreover, although the underrepresentation of CEE countries in ERC grants is a problem for all academic disciplines, political scientists—as evidenced by these data—are doing particularly poorly in the Europe-wide competition for research funding.

Table 1 Top Organizations Hosting ERC Grants

Source: European Research Council (2020b).

Notes: 1The Seventh Framework Programme (FP7). Framework programmes are financial tools through which the EU supports research and development activities encompassing almost all scientific disciplines. They are proposed by the European Commission and adopted by the European Council and the European Parliament.

2Horizon 2020 is the framework programme for 2014–2020, which aimed to implement the Innovation Union, a Europe 2020 flagship initiative aimed at securing Europe’s global competitiveness.

3, 4Both Switzerland and Israel, although not EU members, have been eligible for ERC grants as associated countries that negotiated access to EU research programmes. However, this has changed recently. As a result of growing tensions in the EU–Swiss relations, Switzerland currently is treated as a nonassociated third country, which means that researchers based in Switzerland cannot submit proposals for ERC Starting, Consolidator, and Advanced Grants. Israel continues to participate in the Horizon programme, including the ERC, albeit with limited access to sensitive research areas (e.g., space projects).

What are the structural reasons of such an asymmetrical distribution of research funds? Undoubtedly, government policies have a role in this situation. In the Czech Republic, which outperforms all other CEE countries in ERC grant schemes, subsequent governments have relentlessly incentivized researchers to obtain external support.Footnote 6 A decade ago, the aim was already for the 60:40 ratio between competitive (“targeted”) and institutional funding (Arnold Reference Arnold2011). Crucially, before implementing these measures, the Czech Republic had experienced between 2001 and 2011 the most substantial increase in R&D spending (as a share of GDP) in the region (i.e., from 1.1 to 1.54; it currently approaches 2%). In other countries, the spending barely budged; for example, in Poland, it increased from 0.62 to 0.75.

There also are discipline-specific factors that influence the development of political science; I suggest three possibilities. First, from the early 1990s until the late 2000s—a period of accession to NATO and the EU—many students in the region opted for a political science–related major, with their number increasing as much as sixfold. This affected researchers’ time management, shifting their focus from research to teaching.

Second, political science—having been almost synonymous with the state propaganda during communist ruleFootnote 7—eagerly embraced its newly granted intellectual autonomy, severing even the most delicate connections to the policy-making community. A regional “Cult of the Irrelevant” (Desch Reference Desch2019) spread in CEE political science, with an ever-larger proportion of researchers increasingly fascinated by arcane techniques and formal modeling while neglecting broader criteria of policy relevance.

Third, political scientists too easily accepted the self-congratulations of “democratic consolidation” and “the new golden era” in countries such as Poland and Hungary (The Economist 2014). This made them unable to investigate the harbingers of democratic backsliding in the region, including rising economic inequalities and growing sympathy for authoritarian rule. Looking to the future, we can only hope that the need to understand political reality and tackle actual challenges continues. It is the responsibility of the next generation of political scientists to respond to this task.