Introduction

Latin America is widely known as a region where interstate conflicts have rarely escalated into war.Footnote 1 Since the end of the dictatorships in the late 1980s and 1990s, a concerted effort to foster relations between states rendered the spectre of an armed confrontation even more unlikely. At the same time, however, Latin America suffers from some of the highest rates of violence and crime.Footnote 2 In many countries the police, far from being a solution, have become part of the problem due to corruption and a lack of preparedness. Latin American populations place consistently higher trust in the military than in the police,Footnote 3 despite the former being often under-funded and lacking an enemy against whom to defend the homeland. In this scenario, governments have turned to the military to guarantee internal security and to meet an additional range of basic necessities, which other, civilian state agencies have been unable to address. The tasks range from innocuous ones like providing haircuts in remote communities to fight parasites, to tasks that have been met with suspicion, such as collecting waste when the disposal service is on strike or the custody of ballot boxes in elections, to such invasive ones like prison security and public order. The military has mostly accepted these tasks without presenting any meaningful opposition given its historically strong sense of responsibility for the state and la patria, values that are expressed in the ideas of internal order and stability and that are deeply engrained in its role conceptions, the ‘shared view regarding the proper purpose of the military organization and of military power in international relations’.Footnote 4

Even in those countries where the post-dictatorship legal frameworks kept the military from internal missions, namely Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, in recent years the distinction between external defence as the domain of the armed forces and internal security as the domain of law enforcement agencies has become increasingly blurry. An extreme example in this regard is El Salvador, where a presidential decree enables the army to cooperate with the police in border surveillance based on the consideration that exceptional circumstances demand military support. The decree has been renewed time and again over the past 27 years, turning the exceptional into normal and thereby challenging the country's legal framework. Also in other parts of Central America, Mexico, and Brazil, the military's involvement in the fight against organised crime, once declared a ‘temporary measure’,Footnote 5 has lasted for more than a decade without any visible improvement of security.

Many regional observers and especially policymakers hold that the military's internal use is justifiable on practical grounds, highlighting the lack of civilian state capacity, societal demands for security and basic services, as well as the armed forces’ organisational strength and logistics capacity.Footnote 6 Accordingly, the use of the military internally is warranted, as a provisional instrument, as long as there is no suitable (civilian) alternative to solve a problem and until such an alternative is available. It is surely uncontroversial that the collaboration of the military is necessary and legitimate in emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, determining the end of their ‘provisional’ deployment tends to be almost impossible: societies begin to normalise the extraordinary, the state ‘forgets’ to build alternative capacities, and the military integrates new operational experiences into its organisational structure and role conception.Footnote 7 The idea of the military as the ultimate guardian of the state, which goes back to the wars of independence, has survived as part of the military's self-image despite the democratisation processes of the 1980s and 1990s. Today, the armed forces no longer claim a direct hold on power but to a greater or lesser extent still ‘expect and seek to act’ in different areas of the state,Footnote 8 a posture that is unlikely to change as long as governments call upon the military to fill in where civilian state capacity falls short.

Against the pragmatic view stands compelling evidence on how domestic threats and non-traditional military missions account for weak civilian control and even Latin America's military dictatorships.Footnote 9 Reviving the ghost of coup d’états, from this perspective the excessive use of the military is understood to undermine the rule of law and threaten its subordination under civilian control. What is at stake is the preservation of democracy.Footnote 10 In the same line, the argument advanced here rejects the extensive use of the military. However, we broaden the focus beyond the goal of democratic survival to shed light on the consequences the internal use of the military yields on civil-military relations and the functioning of democracy in terms of its performance and quality; aspects that are also highlighted by the concept of good governance. Adding to a literature that is largely based on single cases, by placing civil-military relations within the broader context of democratic governance we demonstrate how the military's wide-ranging internal missions have perpetuated democratic deficits across Latin America.

The point that civil-military relations are more complex than the institutionalised control of the military and the absence of coups d’états is today well established.Footnote 11 The newer frameworks of civil-military relations refer variedly to concepts such as effectiveness, efficiency, modernisation of bureaucracy, civic political culture, and democratic governance of the security and defence sector, among others.Footnote 12 Building on these insights, we argue that in order to capture the implications the military's internal use has on civil-military relations it is necessary to take into consideration standards of democratic governance not only in the security and defence sector, but more generally. More specifically, we draw on recent evidence from Latin America to show that the internal use of the military has negatively affected the quality of democracy in at least four regards. First, it challenges the rule of law in that the permanent or near permanent involvement of the military in internal affairs is inconsistent with the majority of Latin America's constitutional provisions and legal frameworks. Second, it shielded the armed forces from modernising reforms, including reducing their size. Third, it has prevented the development of civilian capacities to find solutions to internal problems. Fourth, it worked to foster undemocratic tendencies in that it undermined the legitimacy of civilian authorities. Furthermore, the military's use to fight organised crime is widely known to lead to human rights violations. We do not deal with this last, already well-documented, negative consequence for democracy as it mostly applies to internal security missions only but not to other missions such as developmental ones that are also part of the study objective here.Footnote 13

Our case against the internal use of the military is different from standard arguments as it looks broadly at the different aspects of democratic governance to examine the effects on civil-military relations. Doing so allows us to point to long-term, more far-reaching risks for democracy stemming from an expanded set of military roles that result from operational experiences, and are facilitated by already existing role conceptions about the military as a guarantor of public order and stability. Due to the latter, even those that are hesitant to see the military's traditional mission of territorial defence watered down maintain a sense of duty to do anything in the name of la patria. The article adds to the existing literature by explaining in detail the risks for the quality of democracy, which are generally mentioned only in passing if they are mentioned at all.

Latin America is a heterogeneous region of 33 states. For practical reasons, we concentrate the analysis on 11 states that are either critical cases and/or represent Latin America's different subregions: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay in the Southern Cone; Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru in the Andean region; El Salvador and Nicaragua in Central America, and Mexico. Together, the chosen cases allow for breadth in the observations. The data we use to illustrate particular arguments are drawn from a wide range of different sources, including press reports, the International Institute for Strategic Studies’ annual assessments of military capabilities and defence economics (Military Balance), national statistical records, the Latin American Security and Defence Network's Comparative Atlas of Defence, the annual Latinobarómetro surveys, and others. The more in-depth case-based evidence, although necessarily selective, was chosen to illustrate phenomena that we will either flag as common in the region or mark as an exception to demonstrate the democratic risks of involving the military broadly in internal missions.

The article begins with a review of the literature on civil-military relations, the quality of democracy, and domestic missions of the armed forces. Next, we discuss Latin America's spectrum of military missions and the practical view in favour of the armed forces’ internal involvement. The subsequent sections present the empirical evidence to show how the military's engagement in domestic missions has stretched the constitutional and regulatory principles of the armed forces’ doing. Furthermore, we will demonstrate how it disincentivised both the development of civilian state capacity and military reform, as well as the development of a strong democratic political culture. The last section summarises and concludes.

Civil-military relations, the quality of democracy, and the internal use of the armed forces in Latin America

Civil-military relations describe a diverse set of relationships between different civilian actors and the military. While studies in political science have traditionally focused on relations between political elites and the military leadership,Footnote 14 we conceive of the military as an institution and of civilians as society in general terms to examine the effects of internal military missions on democratic governance. Specifically, we highlight how the prolonged internal use of the military has negatively affected four democratic standards: the rule of law, state capacity to deliver basic services, as well as external and internal security, and a democratic political culture. These are also highlighted by the concept of good governance, which embodies the principles of effectiveness, efficiency, accountability, participation, and equitability.

To be sure, the military's domestic use is certainly not the only factor to blame for Latin America's deficits, which have complex roots going back to colonial times. What is more, the historic lack of civilian state capacity is often cited as one of the chief factors driving politicians to rely on the armed forces as ‘substitute institutions’ to step in where other capacities are of short supply, based on the (wrong) myth that the armed forces are capable administrators.Footnote 15 However, as we will argue, the strong correlation between the use of the military for domestic tasks and what has been described as ‘endemic state weakness’Footnote 16 manifested in low performance indicators across policy areas should also be seen as one of cause and effect.Footnote 17 After all, the availability of the military wildcard whose deployment tends to be considered legitimate wherever civilian capacity is lacking sets off pressures to develop an effective state apparatus.

The theoretical link between internal missions and the military's involvement in politics is well established. In his classic work The Soldier and the State, Samuel P. Huntington maintained that a professional military, one that has expertise in (external) defence, service responsibility, and high levels of corporateness, respects civilian authority.Footnote 18 However, professionalism gets weakened if the military is deployed for ‘non-military’ missions such as community support, thus weakening civilian control. Qualifying the argument, Alfred Stepan developed the concept of the ‘new professionalism of internal security and national development’, whereby military role expansion politicised Latin America's armed forces often to the point of taking power.Footnote 19 John Samuel Fitch later argued that a democratic conception of military professionalism may be compatible with developmental and internal security functions. Still, he warned that the ‘“developmentalist” variant requires stronger policy controls by civilian authorities’ to prevent the military from assuming a tutelary role.Footnote 20 According to Rut Diamint, even after Latin America's democracies consolidated it has been necessary to restrict military missions to external defence. Reflecting the military's historic role conception, ‘soldiers still think that they represent the true national interest’, and therefore governments should avoid providing them with a ‘direct and privileged relationship with society’ through internal missions.Footnote 21

One strand of the civil-military relations literature argues that the nature of the dominant threat determines whether or not the armed forces are subordinate to civilian control. Again, the consensus is that all else equal, higher internal threats and the military's deployment to face these have a detrimental effect on civilian control.Footnote 22 External preoccupation distracts the military from domestic politics and, at the same time, propels civilians to actively involve themselves with defence matters to exercise control functions.Footnote 23 In turn, internal missions such as counterterrorism ‘pull’ the military into politics since governments depend on their expertise at the same time as they ‘push’ the military into politics by providing them with opportunities to assert their preferences.Footnote 24 Beyond the question of civilian control, however, most of the theoretically-oriented, general and Latin America-specific literature has paid little attention to the implications of internal missions on the quality of democracy broadly conceived. Yet, as Lindsay P. Cohn also puts it: ‘While “civilian control of the military” may seem like a narrow issue, it is closely connected to the larger web of civil-military relations and, fundamentally, to democratic governance.’Footnote 25

David Pion-Berlin's work is one of what is probably only a handful of exceptions that have openly challenged the internal mission – weakened control orthodoxy of the classic civil-military relations paradigm. According to Pion-Berlin, internal missions are detrimental to democratic standards only if they are inconsistent with the military's capabilities and proclivities.Footnote 26 If the military is well equipped to carry out internal tasks, their deployment is justified by a lack of state capacity as long as the duration and scope of the operations are defined by civilian authorities.Footnote 27 A similar, practical reasoning was expressed as early as in the 1960s, echoing those militaries that sought to legitimise the military-led authoritarian regimes at the time: the armed forces’ ‘technical proficiencies and organizational formats should be exploited [...]for socially useful purposes’.Footnote 28 Civic action in particular was described as an ‘exciting prospect’ that ‘would not only make a substantial contribution to national development but also, hopefully, provide soldiers with a sense of service and participation in national efforts’.Footnote 29 Not that different, still during the period of Latin America's democratic consolidation in the 1990s, another US observer argued: ‘If national well-being depends on a particular task being carried out, and no institution other than the military can undertake it successfully, then the military's assumption of that responsibility is appropriate.’Footnote 30 Yet, it was deemed appropriate only if the military's involvement would be ‘transitional’, temporally restricted, and defined by a clear timetable.Footnote 31 These authors fail to pay attention to the fact that once involved, it is difficult for the military to give up its missions particularly if those increase its popularity. Once engaged in a new mission, the armed forces will likely develop vested organisational interests even if the mission was initially rejected.Footnote 32 Furthermore, as we will argue below, policymakers have used the justification of temporary deployment to use the military on a near constant basis for domestic purposes. It is thus that the internal use of the armed forces has perpetuated democratic deficits in Latin America.

Apart from the studies discussed so far, there is a considerable number of contributions written in Spanish and published mostly in regional outlets.Footnote 33 While often overlooked,Footnote 34 this overwhelmingly case-based and descriptive literature still offers valuable insights and empirical data. Interestingly, few authors from the region hold a principled view against domestic military missions.Footnote 35 Most acknowledge that the reasons to deploy the military internally are pervasive, especially with regards to crime, while at the same time highlighting risks such as human rights violations, corruption, and the politicisation of the armed forces if the militarised approach is used as a long-term measure.Footnote 36 Yet, with a number of exceptions that have mostly been published for a Latin American readership, the effects on democratic governance of internal missions, especially those other than fighting crime, have received scant systematic attention and will therefore be the focus of this article.

Before we demonstrate how the military's domestic involvement prolonged democratic deficits in Latin America, in the next section we describe the region's spectrum of military missions. We further offer an explanation of why, in a region that has repeatedly experienced grave human rights violations under military rule, the armed forces are once again called upon to take on internal tasks.

Latin America's spectrum of military missions

Latin American militaries have traditionally assumed a central role in nation and state-building. In a region where territorial pacification and political centralisation lasted well into the twentieth century, governments typically depended on the support of the military to remain in power.Footnote 37 This ensured that the military, as an institution, was generally relatively well resourced and maintained its continued relevance and visibility in the countries’ public and often also political life. Thus, infrastructure building and other types of community support have long been part of its operational experiences and role conception.

Yet, over the past two decades, in most countries the spectrum of military missions has expanded. Contrary to the general assumption that it is the military that pushes for a greater organisational role, across Latin America it has instead been pulled by civilian authorities to assume new tasks and even get involved in politics.Footnote 38 Evidence from some countries shows that the military was at times reluctant to assume internal missions.Footnote 39 In Chile, a former presidential envoy to the country's Araucanía region that has long been riddled by a violent conflict between the indigenous Mapuche community and the state over territory and autonomy, complained publicly that the armed forces were ‘reticent’ to support the police in handling arson attacks: ‘In my opinion, it is unheard of that they arrive at the meetings with lawyers in order to say that they cannot do what one would like them to.’Footnote 40 Most often, however, the military has followed governments’ calls to get into ‘the first line of support from the State to citizens’,Footnote 41 especially when it comes to natural disasters, national responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and other, more permanent tasks of community support that involve few risks while, at the same time, tend to fetch public support. Against the backdrop of the military's traditional role conception as a state and nation-builder and seeking to maintain its institutional benefits, civilians have successfully pulled the institution into new missions.

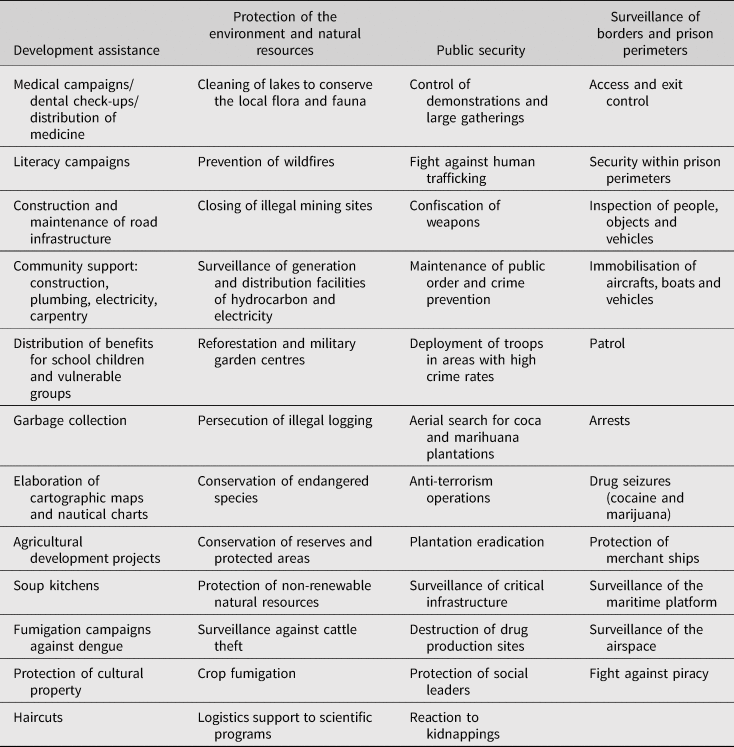

Other than defence, which continues to occupy a dominant place in the role conception of Latin American militaries even if in practice they do not fight wars, the tasks they have been carrying out on a frequent basis can be grouped together into four missions: national development, protection of the environment and natural resources, public security, and surveillance of borders and prison perimeters. Table 1 provides an overview of the tasks pertaining to each of these missions for the cases considered in this study.

Table 1. Military missions in Latin America other than defence.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on RESDAL, Atlas comparativo de la defensa en América Latina y Caribe (2016) and Samanta Kussrow (ed.), Misiones principales y secundarias de los ejércitos: casos comparados latinoamericanos, RESDAL (2018).

Cooperation in national development, which has a long-standing tradition in Latin America, refers to all activities that aim at enhancing social well-being. Mexico's army, for instance, has organised soup kitchens, Brazil's military runs vaccination campaigns, and the Bolivian army distributes food aid to the elderly and school children. Environmental protection and the protection of natural resources include programmes like the fight against illegal mining in Colombia or reforestation in Mexico, an activity that is also carried out by El Salvador's military, together with the cleaning of the country's lagoons. Internal security is closest to the military's traditional mission of defence although with important differences with regards to its objectives, instruments and the legal principles that regulate the exercise of legitimate violence. As we will further detail below, except for Mexico and Ecuador, Latin America's constitutions clearly distinguish between external and internal security and exclude the armed forces from the domestic sphere safe for legally declared exceptions. Nevertheless, to different degrees all Latin American militaries are today engaged in either protecting critical infrastructure or fighting terrorism, crime, drugs or human trafficking, among other internal security tasks. Similarly, border control has turned from being an exceptional task to an established mission. Uruguay and Chile were the last countries to change their legislation in 2018 and 2019, respectively, for the military to support the police in curbing crime and other, unwanted cross-border flows and movements.

Why, in a region with a history of authoritarian rule and domestic political violence have governments relied on the armed forces to carry out the missions described above considering that the risks of the military's domestic involvement are well known? The status quo favours both the military and governments, to the detriment of democratic governance.Footnote 42 A broad spectrum of military missions serves Latin America's armed forces’ corporate interests in that it justifies defence spending in a context that has rendered traditional territorial defence increasingly obsolete. While one may object that the armed forces only welcome tasks that conform to their self-identity as professional soldiers, it is worth recalling that considerations of internal security have justified not only the military's involvement in politics, but also its long-standing role conception as a force for development.Footnote 43

Governments, on the other hand, have mainly relied on the military as a sort of wildcard to make up for a persistent lack of state capacity to provide basic services and security. Latin American states have historically struggled to centralise power and pacify their territories. Still today, as Miguel A. Centeno puts it, ‘the Latin American state cannot be called a Leviathan’ capable of maintaining order and institutional autonomy.Footnote 44 The military has thus become an affordable, legitimate, and indeed often indispensable substitute. Governing without military support has been an impossibility for the region's many ‘improvisational’ states which, in the absence of a strong sense of national allegiance, are constantly obliged to attract and keep the strongest forces within a fragile ruling coalition.Footnote 45 Moreover, by avoiding debating military reform, governments have been able to maintain cordial if not friendly relations with the armed forces, thereby relying on what Huntington called ‘subjective control’.Footnote 46 In this situation of apparent pareto optimality, the United States’ policies towards Latin America have further legitimised the military's internal use. Whether it concerns illegal drugs, health, migration, or natural disasters, since the 1990s but especially since the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the United States has pushed the idea that the varied challenges in these areas constitute national security threats that can and ought to be met with a military response by Latin American governments.Footnote 47 However, it should not be forgotten that also the US-critical members of the Venezuelan-led Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA) have used the military increasingly for domestic purposes.Footnote 48

The following sections delve into how the proliferation of military roles has prolonged democratic deficits in Latin America in four regards: the rule of law, military reform, the development of civilian state capacity, and lastly, the fostering of a democratic political culture.

The failure of legal security

The distinction between external and internal threats to the state has been an integral part of Constitutionalism from its very beginnings. As the French revolutionary Constitution of 1791 read:

All branches of the public force employed for the security of the State against enemies from abroad shall act under the orders of the King. … No body or detachment of troops of the line may act in the interior of the kingdom without a legal requisition. … Requisition of the public force within the interior of the kingdom appertains to the civil officials, according to the rules determined by the legislative power.Footnote 49

Based on this distinction, a division of labour between the armed forces and the police gradually emerged in liberal democratic states. Constitutions have further regulated exceptional circumstances that threaten public order or state survival through legal figures like the state of emergency, martial law, or the state of war. In such atypical situations, fundamental citizen rights may be restricted, and the control of public order handed over to the military given that three conditions are met. First, the sole objective of such extraordinary measures must be to re-establish order and security; secondly, they must apply for a specific period of time only; and thirdly, they must be approved and supervised by the legislature. Consequently, turning the exceptional into a structural condition by normalising the militarisation of public order runs against constitutionalism's separation between internal and external security. As this section will show, several Latin American countries failed to uphold the legal provisions that regulate military deployment, including constitutional principles. In a region where the rule of law has historically been and continues to be uneven and weak,Footnote 50 this failure of legal security contributes to eroding political rights, civil liberties as well as accountability mechanisms.Footnote 51 In Brazil, for instance, legal debates around the deployment of the armed forces in heavily crime-stricken areas have contributed to create an image of state violence as morally superior to criminal violence, rendering already marginalised populations even more vulnerable.Footnote 52

José Julio Rodríguez Fernández and Daniel Sansó-Rubert Pascual classified Latin American countries according to their position with regards to the military's role in internal security.Footnote 53 Among the countries considered here, those that have largely maintained the traditional paradigm are Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay. Bolivia, Brazil, Nicaragua, and Peru are classified as having a ‘flexible’ position, while those favourable to involve the armed forces in internal security are Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, and Mexico. However, of this latter group only the constitutions of Ecuador and Mexico designate internal security as a mission of the armed forces, thus putting the blurring of internal and external security on firm legal ground.Footnote 54 As shown in Table 2, all other countries give the military a supportive role only in the case of necessity or exceptional circumstances.

Table 2. Military missions according to constitutional, legal, and political provisions.

* Only in the case of necessity

** Only under exceptional circumstances

Constitutional provisions

Provisions established by law

Provisions in policy documents

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on different national sources and RESDAL, Atlas Comparativo de la Defensa en América Latina y Caribe (2016), chaps 1, 7.

Despite the exceptionality clause in El Salvador's constitution, governments have used the military systematically to fight crime. In practice, this meant that the armed forces have been deployed for more than a decade in the country's most dangerous prisons, at illegal border crossings, and in some of the most crime-affected urban areas. Without the constitutionally required state of exception formally declared, however, the military's law enforcement activities have contravened the legal order.Footnote 55 Colombia, for its part, has invoked a state of internal commotion as provided for in the constitution repeatedly during the presidency of Álvaro Uribe (2002–10). The fight against drug cartels and the guerrilla have gradually trivialised this constitutional principle, turning the state of internal commotion into something akin to normalcy and a bureaucratic hurdle at the most. More alarmingly, even after the state of internal commotion ended, the armed forces have still been deployed to fight the narcos, organised crime, and the guerrilla in the country's dense jungle areas.

The constitutions of Brazil, Nicaragua, and Peru recognise that the armed forces should in principle stay out of internal security. In the case of Bolivia, this is codified in the framework law of the armed forces (Ley Orgánica de las Fuerzas Armadas). However, all these countries have interpreted the exceptionality clause extremely flexibly to the effect that it no longer presents an effective legal restriction. In Brazil, the constitutional requirement that the military can only be deployed if the police is overburdened, is often presented as a result of political negotiations rather than an assessment of necessity. Nicaragua has used its armed forces on a nearly permanent basis to fight drug trafficking and organised crime and to protect strategic installations. While the division of labour between the military and the police is clearly defined in Bolivia, President Evo Morales (2006–19) used the former frequently to safeguard public security. Similarly, as indicated in Table 2, in Peru the armed forces have continually been involved in border control and anti-crime operations.

Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay have largely maintained the traditional paradigm of excluding the military from domestic security. However, in recent years legislation was modified in all three countries towards legalising some intervention of the armed forces. Uruguay adopted a new Border Law (Ley de Fronteras) that changed the military's role designation in 2018. Implemented in 2020, the Ley de Fronteras allows for military operations in designated, unpopulated border areas to carry out law enforcement. Similarly, Chile in 2019 allowed the armed forces to be deployed at the border to support the fight against drug-trafficking and organised crime. The presidential decree was amended in 2021 to include countering illegal migration and human trafficking. In Argentina, the strict separation between internal and external security was temporarily blurred through several regulations adopted during President Mauricio Macri's term in office (2015–19). Macri turned internal security into a key topic during his administration and decreed the military's deployment in anti-narcotics operations and to guard strategic objects. Yet, what had been a radical and controversial change to Argentina's post-dictatorial defence policy was revoked under Macri's successor, Alberto Fernández.

Apart from legal documents, Latin America's defence white papers, security strategies, and other relevant policy documents list among the main strategic priorities the protection of natural resources, the fight against crime and illegal drugs, investment in science and technology, as well as natural and man-made disasters.Footnote 56 Tsunamis, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and hurricanes are almost permanent threats in some Central American countries, and the enormous wealth in natural resources in the region has attracted both speculation and looting. Doubtlessly, these involve problems that require states to activate specialised bodies to protect the environment. Yet, the armed forces, who have been pushed to support the task in most countries, have neither the legal competence nor are they trained to articulate the necessary preventive policies. As Table 2 shows, the designation of such tasks to the military is nevertheless generalised within the region.

The above further emphasises the point that the spectrum of military missions in Latin America is rather broad, which is reflective of historical military role conceptions as a guardian of the state. Problematically for the quality of democracy, we demonstrated that in several cases the internal use of the military has stretched constitutional principles sought to limit the area of competency of the armed forces or, even worse, violated them. The fact that constitutional and other legal provisions are bent in Latin America is neither new nor exclusive to military deployments.Footnote 57 Yet, it represents a risk for democratic governance as it puts additional strains on the rule of law, which is ultimately what makes both civilian authorities and the armed forces answer for their actions. Thus, it is ultimately the rule of law that protects the population from wrongdoing when the armed forces are deployed for internal tasks they are not necessarily prepared for, such as when excessive force is used in law enforcement operations.

The failure of military reform

It is through the military, together with the police, that the state exercises its monopoly on the use of force. Yet, defence is a public policy such as health or education, ‘thus making it susceptible to political and financial constraints’.Footnote 58 Just like any other state institution, the military is held to carry out its duties to satisfy the needs and demands of the people it serves. To meet these exigencies, it needs to go through a process of constant evaluation and improvement. However, by frequently entrusting the military with duties other than its core functions, governments have diverted attention away from its basic tasks and prevented it from engaging in the process of continuous evaluation and readjustment. In this section we argue that the military's prolonged and abusive internal use has prevented the for any state institution necessary process of permanent adjustment. Consequently, many countries have maintained militaries that are in many regards ineffective as an instrument of defence, though useful to fulfil a range of internal missions that tend to be popular among the people.

Except for Panama and Costa Rica, which have no armed forces, there has never been a serious debate in Latin America whether it is necessary to have a military.Footnote 59 The changing dynamics of the global as well as the regional security environments have nevertheless raised questions about the usefulness of Latin America's armed forces. At the global level, the end of the Cold War spurred a general debate on the nature of future threats, changed dominant risk perceptions across the world and consolidated a shift in the meaning of security from a state-centric, military conception towards a multidimensional understanding of security affecting different groups and individuals.Footnote 60 All of this pointed to a central question: was the military still the most suitable instrument to protect citizens from substantially different threats? In addition to this global trend, Latin America's local circumstances further reinforced the military's ‘situation of “structural unemployment”’.Footnote 61 Historically characterised by low levels of international competition that only rarely escalated into war, with the return to democratic rule the risk of an armed conflict was further diminished.Footnote 62 The military, now with an even lower probability to be called upon to perform traditional functions of territorial defence, had difficulties to find a new role after its political involvement had ended or was at least significantly reduced. Like in other parts of the world, it welcomed a range of new missions as a means of justifying defence budgets including peacekeeping, humanitarian aid and disaster relief, state building and, in some cases, internal security. However, while many Western democracies simultaneously embarked on reforms to creating smaller, highly skilled militaries and flexible force structures, similar modernisation efforts failed to occur in Latin America. Around the world, territorial defence has remained ‘the ultimate justification of national armed forces’ but, at the same time, the most powerful militaries ‘have become organizations specialized in crisis management in a broader sense’ to adjust to the new circumstances.Footnote 63 In Latin America, this conversion failed to take place.

The region's military capacities today are limited to the extent that some countries fall short of keeping their armed forces operable. Table 3 illustrates this based on the loss of air combat readiness in seven of the eleven countries under study. Over the past decade, only El Salvador and Peru have invested in comparatively costly air power and Chile has maintained its capabilities. All others stood less prepared for air combat in 2019 than they did in 2009.

Table 3. Loss of air fighting power (2009–19).

Source: IISS, The Military Balance (2010) (2020).

Taking into account that air power is vital for defensive purposes but that its use for other tasks is limited, the lack of investment as demonstrated in Table 3 indicates that governments have looked at defence not as a priority. This claim is supported considering the comparably large size of many Latin American militaries, which withstood the structural imperative of downsizing during the post-Cold War period.Footnote 64 Drawing on Pion-Berlin and Martínez, we use a population/military indicator that divides the number of civilians per soldier by one hundred.Footnote 65 This produces a scale with easily comparable values between one (large militaries) to ten (small militaries). Following Pion-Berlin and Martínez, a population/military balance above four qualifies as a deployment model based on a functional logic as it pertains to the category of consolidated democracies.

As Figure 1 demonstrates, the smallest armed forces proportional to the national population are those of Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and Nicaragua. While Argentina reduced the size of its military drastically during the democratic transition, Nicaragua's was downsized gradually over the past 25 years. Mexico, in turn, increased the number of active-duty personnel between 2007 and 2019, mainly due to the military's deployment in the fight against illegal drugs. A similar case is El Salvador. After initially scaling down its military, the past decade has seen a renewed increase that brought it back to the levels of the late 1990s. Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia have in recent years shown a trend to reduce their militaries but still range below the threshold of an optimal size. This is even more the case for Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay, which have maintained large militaries deployed throughout their territories but that do not necessarily correspond to a functional logic maximising operational capacity.

Figure 1. Active soldiers according to population/military balance (1997–2020).

On the one hand, the lack of modernising reform, including downsizing, has been a consequence of the military's bargaining power as governments have relied on it to solve internal problems. For its organisational interests, the military will typically resist downsizing in order to maintain its budget, privileges, and political clout. On the other hand, however, labour-intensive organisations have suited civilian governments more than would highly technological ones, whether for handing out food packages during the pandemic, carrying out literacy campaigns or patrolling urban areas. It is illustrative that five of the eleven countries under study have formally maintained obligatory conscription (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, El Salvador, Mexico) and another three voluntary conscription (Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru), with conscript armies having been considered ill-suited to meet contemporary demands for highly professional, flexible rapid reaction forces. In fact, there have been relatively few civilian attempts to reduce the size of the military. With defence policy not being seen as a priority area, Latin American governments have shown little interest in developing capital-intensive, modernised forces. Instead, the military has been looked at as an instrument that should count with a large workforce for extensive territorial deployment with little technological capacity to support socioeconomic development, provide basic supplies and assistance in disasters. Thus, some procurement programmes have been implemented to improve the military's ability to undertake internal tasks.Footnote 66

The lack of reform is also visible in the use of the military abroad. Among seven dimensions of the restructuring process that has taken place in advanced industrial states, Manigart identified the ‘multinationalization of formerly national military structures’.Footnote 67 As Nina Wilén and Lisa Strömbom demonstrate, collective defence and collective security have become the core roles of contemporary militaries in industrialised, democratic countries alongside national security,Footnote 68 with the majority of military operations being carried out by multinational forces. A comparison of Latin American troop deployments abroad with four referent countries in Europe – Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain – shows that there are remarkable differences in this reform dimension. Table 4 distinguishes deployments in UN missions from non-UN missions. UN missions refer essentially to peace operations, and it is here where the Latin American countries under study have almost exclusively participated. Only El Salvador, Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay have contributed to non-UN missions, which were likewise peace operations safe for El Salvador's relatively small deployment in NATO's International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. The Europeans, in contrast, have consistently deployed more troops in non-UN missions, which indicates a greater use of the military as an instrument not only for defensive reasons but of foreign policy more broadly.

Table 4. Troops deployed in missions abroad (2010–19).

Source: Based on data from IISS, The Military Balance (2011–20).

Generally speaking, expeditionary missions require a substantive level of professionalism, technological sophistication, and interoperability. In many of Latin America's militaries, these elements are deficient.

Considering the above, it is clear that most of the time Latin American governments have looked at the military not as an instrument primarily for defence against conventional and unconventional threats and neither of collective security. Instead, and in line with the military's traditional role conceptions, it is plausible to argue that at least some have used the military as a welfare-enhancer to provide relatively secure jobs. As shown in Figure 2, from the countries under study those with the highest unemployment rate in 2019 tended to have a smaller population/military balance (PMB; meaning that they have a large military relative to their population). For the cases of Argentina, Brazil, and Nicaragua, this is true only when the military police is included as part of the military (as we did in Figure 2). As mentioned above, Argentina and Brazil have small militaries relative to their population, although together with Colombia they have the largest armed forces in absolute numbers. The strong correlation between unemployment and size of the military suggests that one among several factors that explain why in some countries governments have abstained from downsizing the military was the desire to prevent further increases in unemployment rates and thus a higher risk of political instability.

Figure 2. Unemployment relative to population-military balance (2019).

Source: The World Bank, Unemployment, total (percentage of total labour force, modelled ILO estimate), available at: {https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS} IISS, The Military Balance (2020).

Developing countries have often used the state as an employer ‘of last resort’.Footnote 69 While many have argued that oversized public employment is motivated by the desire to generate and distribute rents, in the case of Latin America the main driver has likely been to provide a form of social insurance.Footnote 70 This can be evidenced, for example, in sporadic debates in Uruguay about the possibility to reintroduce military service. Thus, the draft has been presented a solution to drug addiction and a beneficial option for ‘ninis’, youths that neither study nor work.Footnote 71

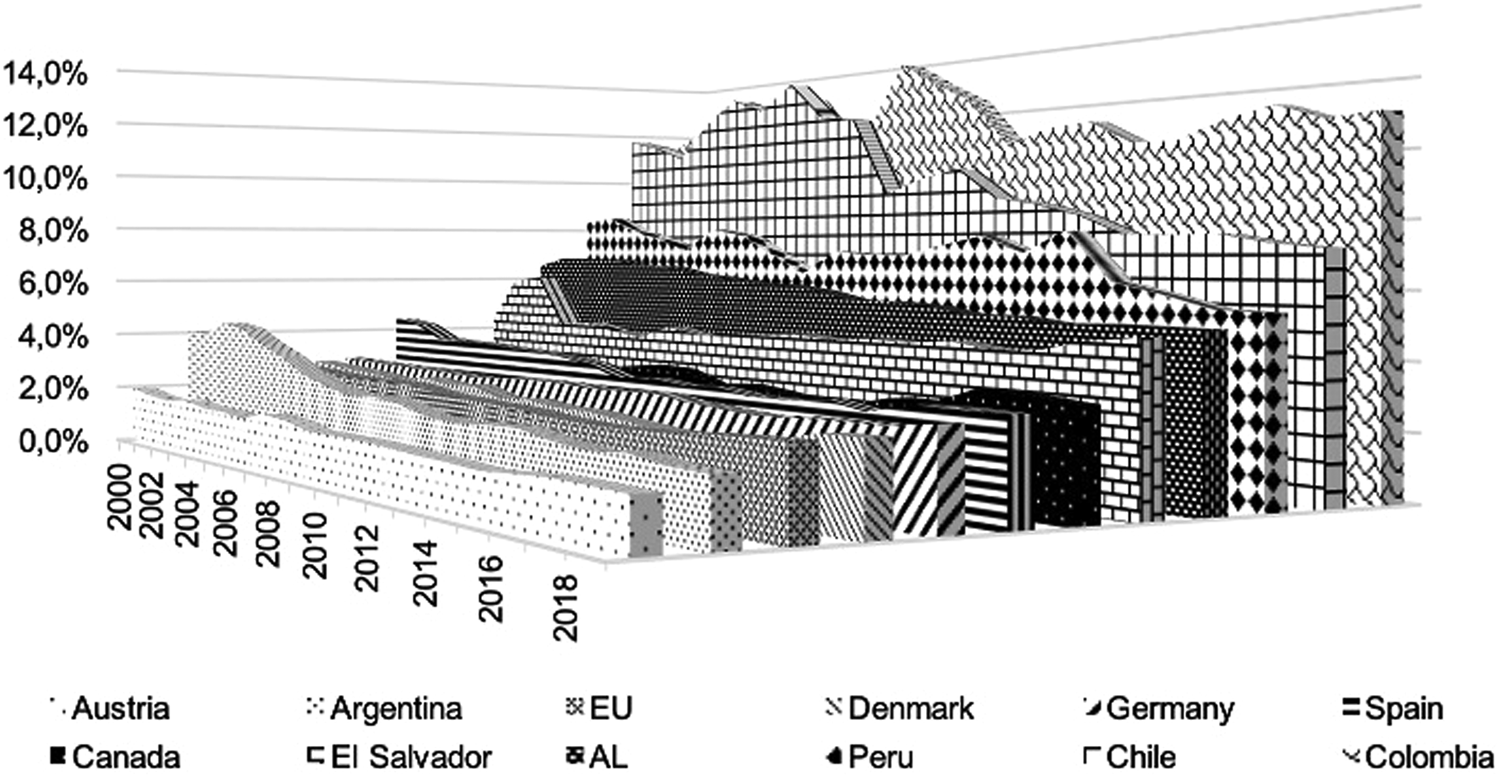

The lack of structural reform is troublesome from a democratic governance perspective. Quite apparently, Latin American militaries are to a greater or lesser extent ill-suited to face what are arguably the most likely future scenarios of national defence: situations that require technological superiority and rapid deployment instead of mass armies on the battlefield. This lack of preparedness is even more problematic since defence expenditures as a percentage of government spending have remained comparatively high over the past two decades. Figure 3 contrasts the average defence spending in Latin America, Europe and Canada, together with those of selected Latin American and European countries individually. While Europe's average defence spending as a percentage of total spending oscillated between 3.1 per cent and 2.3 per cent, the Latin American average ranged between 6.5 per cent and 5 per cent. In both cases, the numbers steadily declined until 2016; though unlike in Europe, where the percentage of defence expenditures began to increase in the years after, it remained stable in Latin America at 5 per cent. It is evident from Figure 3 that there are differences between the countries of one region. Argentina, for instance, is a clear outlier in Latin America. Nevertheless, the overall picture demonstrates that Latin American militaries receive a comparably greater share of government expenditures even though they fail to meet standards of effectiveness in what is their formally designated core function of national defence. Spending in the region does not reflect investment in air power nor in other aspects of modern defence, but the payment of salaries and pensions of often over-sized militaries.

Figure 3. Percentage of government spending on defence, Europe and Latin America (2000–19).

Source: Data from SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, available at: {https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex}.

While the internal use of the armed forces by itself surely cannot account for the failure of military modernisation, especially in Latin America's mainly middle-income countries, in this section we argued that it had important effects in lowering structural incentives to embark on military reform. Although the causal relation is difficult to show, taken together, the different factors discussed point strongly to the military's developmental and internal security functions as reasons why the armed forces are not held to standards of military effectiveness and thus, democratic governance. One may argue that internal deployments are democratic in so far as they reflect popular trust in the armed forces. Yet, apart from other negative consequences stemming from the extended use of the military internally, we argued in this section that it is cost-ineffective in so far as it incentivised the maintenance of inflated armies and therefore fails to live up to democratic standards.

The failure of civilian capacity development

By not challenging the military's traditional role conceptions as guardians of the state and la patria and instead relying on the military for domestic purposes governments have – intentionally or unintentionally – exacerbated the difficulties to develop civilian capacities to meet democratic standards. In this section, we advance two arguments to support this point. First, a broad spectrum of internal military missions has hampered the development of civilian capacities of control in the security and defence sector. Secondly, the military's deployment in policy areas other than defence has ‘pushed aside and undermined’Footnote 72 those institutions pertaining to the respective policy area. Whether it is in health, education, transportation, housing or else, the lack of state capacity to provide basic services has been pervasive across the region. The phenomenon was famously captured by Guillermo A. O'Donnell's categorisation of ‘brown areas’ where local power systems substitute any meaningful presence of the state. A notorious example of such brown areas are Latin America's shanty towns; Brazil's favelas, Peru's villas miserias, and Mexico's invasiones, where access to water and electricity is limited, crime rates often range well above the national average and ‘police interventions … tend to be unlawful themselves’.Footnote 73 To be sure, we do not claim that the military's internal use is responsible for the lack of civilian capacity across Latin America. Instead, we argue that it has constituted one obstacle besides others to develop viable states able to provide basic services while also acknowledging the circular process through which state weakness has created favourable conditions for the military's internal deployment.

With respect to the negative effects of domestic military tasks on civilian capacities of control, the literature on civil-military relations in Latin America is fairly unanimous in that civilian involvement in the defence sector has been extremely low.Footnote 74 Among the factors that explain this ‘attention deficit’,Footnote 75 at least at the level of decision-making, is the absence of any meaningful civilian career in defence. Local security and defence experts are heard, but their advice seldom translates into policies. In addition, turning the armed forces into a wildcard that could potentially be used in any governance sector whenever needed added further to the lack of incentives to get civilians engaged in defence. A considerable part of what the armed forces do in many countries falls within the areas of competence of the ministries of interior, public affairs, education, and others and has thus little or nothing to do with conventional military core functions. As the military's fundamental purpose of territorial defence gets diluted, opportunities to foster civilian involvement in the area are missed. In Brazil, one observer explains: ‘The Armed Forces have an office in Congress in charge of providing information on the military and national defense to legislators. This office has certainly hampered the emergence of a civilian legislative advisory system specializing in defense issues.’Footnote 76

The absence of civilian expertise and engagement in the defence sector has obvious consequences lowering the quality of democracy in that it weakens control and oversight to hold the military accountable. In addition, the apparent lack of (civilian) government interest leads to less effective policymaking. Considering the 22 Latin American states other than the Eastern Caribbean island states, it is illustrative that except for Chile and Argentina no country counts with a coherent set of regularly published defence policy documents.Footnote 77 Since 1995, a total of 56 such documents have been published, including defence white papers, national directives and policies, strategies and plans. However, these are either rarely updated or appear as collections of different strategy and planning documents that lack a clear integration. Brazil, for instance, the country that has the highest number of defence and security policy guidelines published over the past 25 years, has two National Defence Policies (1996, 2005), two Policies of National Defence (1998, 2008), three Defence White Papers (2012, 2016, 2020), one Paper of Defence and Environment (2017), one National Policy of Defence and National Strategy of Defence (2020) and one document Scenarios of Defence (2020). Chile has published four Defence White Papers, though these have not been updated since 2017 but instead have been complemented by a National Defence Policy in 2020. While the frequency and consistency of publishing policy documents is not the same as the quality of the policy itself, it is nevertheless a strong indicator for the viability of national defence plans and policies.Footnote 78 With little civilian interest in the military as an instrument of defence, it is no surprise that Latin American governments have attended policy programming and planning in that area only sporadically.

Considering civilian capacities in substantial policy areas, it is worth remembering that their weakness has been one of the main reasons cited in favour of the pragmatic position to have the military involved in a broad range of tasks. Accordingly, the use of the military exclusively for defence is a luxury only rich countries can afford.Footnote 79 Against this view, we argue that the military's domestic involvement has worked against the development of crucial capacities that would bolster the legitimacy of the state in the long run and thus generate the means to afford the necessary ‘luxuries’, in addition to allow cutting down on defence budgets.

The military's crowding out of other institutions has arguably been most visible in internal security and with respect to the police.Footnote 80 As countless examples illustrate, the so-called approach of mano dura (iron fist) has never actually worked to improve public security.Footnote 81 Quite to the contrary, there is ample evidence that it has often aggravated or even caused the phenomenon it seeks to address.Footnote 82 Paradoxically though, mano dura policies have time and again been implemented. The use of the military to fight crime and illegal drugs has usually begun as a short-term measure but ended up serving as a long-term instrument. Meanwhile, the necessary police and justice reforms have been postponed, as it is most evident in the cases of Brazil, El Salvador, Mexico, and Nicaragua.Footnote 83 What is more, using the military in internal security operations has drawn the police more strongly into the military's orbit, thereby altering the civil-military relations equilibrium further. This happened in Mexico, for instance, where the civilian Federal Guard was replaced, in 2019, by a National Guard strongly influenced by the armed forces and made up of personnel from the former Federal Guard, the military police, and naval police.Footnote 84

Other than internal security, in most Latin American states the armed forces have held important responsibilities in civilian aviation as well as coastal and marine security. Strikingly, the only country in the region that created a coastguard independent of the Navy is Argentina.Footnote 85 While these areas are managed by civilian agencies in other parts of the globe, the fact that the military has long assumed these tasks in Latin America meant that the prevailing arrangements have rarely been questioned. Similarly, in line with the military's traditional role conceptions, it has served as a provider of social welfare benefits, such as in the case of Peru's Valley of the Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro Rivers (known as VRAEM). One of the main coca-producing regions, in recent years governments have organised civil-military welfare campaigns in the VRAEM to provide medical and legal assistance and to deliver food, clothing, and civic education.Footnote 86 Although the campaigns are financed by the civilian National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs (DEVIDA), they have been coordinated, organised, and carried out by the military, whose protagonist role has prevented the empowerment of civilian structures to provide basic services in the poverty-stricken area. In 2015, a high-ranking DEVIDA official recalled that DEVIDA had to accept budget cuts as more funds were given to the Army: ‘Although I was upset at the time, later I could see that the Army really had done great things, things which my institution could never have done. With these resources, [then President] Humala [a retired army officer] turned the Army into a formidable construction agent.’Footnote 87 The fact that the military, but no civilian agency was in the position to take charge of infrastructure development indicates that it is the repeated fall-back on the former that has left the latter underdeveloped.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, too, the military has assumed a range of tasks that could eventually have been managed more cost-efficiently by civilian actors, including volunteer organisations and medicine students.Footnote 88 Tellingly, Uruguay's Defence Minister remarked that ‘the best defence policy are the social policies’ the armed forces have been implementing during the pandemic,Footnote 89 underlining the argument that the military is not primarily seen as an instrument of defence but as a wildcard to be used where civilian capacity falls short.

Tendencies of undemocratic political cultures

Another dimension of Latin America's lack of state capacity is the absence of a social and political community unified by a national consciousness. In Weberian terms, states have lacked political legitimacy. Drawing on the argument that the internal use of the military foments a public narrative that depicts the armed forces as a capable actor vis-à-vis corrupt and incompetent civilians,Footnote 90 in this section we suggest that the military's internal use in Latin America has contributed to undermine the legitimacy of civilian actors. This has yielded negative effects for the region's democratic culture.

Throughout much of Latin America's history, politics has been considered responsible for persisting poverty, inequality, and political instability. The military, in turn, which was among the first institutions of the Latin American state to consolidate during the late nineteenth century, has enjoyed considerable social standing and respect to the effect that military rule was seen as a viable means to modernise and develop.Footnote 91 This popular narrative has fed into the military's role conceptions, particularly during those periods when it played a politically prominent role. The reputation of being incorruptible and effective has never reflected reality; however, in Eric Nordlinger's words: ‘soldiers have sometimes mitigated some of the “sores” on the body politic: blatant corruption, extreme partisanship, inordinately coercive rule and turmoil.’Footnote 92 For different reasons, politicians have been considered inept to handle internal security, promote economic development and to provide basic services and it is reasonable to assume that the ideology of ‘antipolitics’ has persisted in Latin America's political culture after the latest wave of democratisation in the 1980s and 1990s.Footnote 93

Table 5 presents data on the quality of democracy. The three measurement indicators (V-Dem, the Fragile State Index, and the Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index) are widely used and are presented together here to increase confidence in the respective values considering that both the meaning, as well as the operationalisation of democracy are debated. In addition, to capture how democratic/undemocratic a given political culture is, Table 5 shows data from the Latinobarómetro survey regarding people's attitudes towards democratic and undemocratic regimes from multiple years. The reported numbers in the last two columns are the averaged percentage of people who agreed with the following claims: ‘Democracy is preferable to any other form of government’, and ‘I would not mind an undemocratic government if it solves the economic problems and creates employment.’

Table 5. Democratic culture in Latin America.

Values indicating strong democratic culture.

Values indicating weak democratic culture.

(1) Varieties of Democracy Institute, University of Gothenburg. Scores from 0 to 1. Average 2000–20.

(2) Fragile State Index, The Fund for Peace. Scores from 1 (very sustainable) to 120 (very high alert).

(3) Democracy Index, The Economist Intelligence Unit. Scores from 0 (authoritarian) to 10 (full democracy).

(4) Latinobarómetro. Agreement with the claim ‘Democracy is preferable to any other form of government’, weighted average of data from 1995 to 2018.

(5) Latinobarómetro. Agreement with the claim ‘I would not mind an undemocratic government if it solves the economic problems and creates employment’, weighted average of data from 2001 to 2016.

Two insights are relevant for the purpose of this study. First, although there is some variation across indices, the values coincide broadly in indicating how democratic a given country is. Secondly, combining the data, it is possible to divide the eleven countries considered into three broad categories: consolidated democracies with comparatively strong democratic political cultures, flawed democracies, and democracies under threat with relatively weak democratic political cultures. Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay belong to the first group; the second is comprised of Peru, Ecuador, Mexico, Colombia, and Brazil; and finally, Bolivia, El Salvador, and Nicaragua belong to the third group. Contrasted with the degree to which the military has been involved in internal missions (see Table 2), a correlation becomes apparent between the extensive use for domestic purposes and undemocratic tendencies. Accordingly, Argentina and Chile are the countries most restrictive about the military's internal functions. They are followed by Uruguay, Peru, Ecuador, and Mexico, which have used the military internally on a more regular basis but still in a limited fashion. Colombia and Brazil, together with the least democratic countries of Bolivia, El Salvador, and Nicaragua, have relied extensively on the armed forces to carry out a range of different domestic tasks on a regular basis. Although investigating the strength of the causal effect is beyond the scope of this study, the correlation supports the argument developed in earlier studies that the extensive use of the military fosters undemocratic attitudes, both within the military and society.Footnote 94 It is thus that the countries in question have less democratic institutions, procedures as well as political cultures.

Conclusions

This article set out to shed light on the implications of Latin America's internal use of the armed forces for civil-military relations placed within the broader context of democratic governance. Drawing on selected evidence from across the region, we argued that internal missions have perpetuated democratic deficits in at least four regards. The military's frequent use internally has (1) challenged the rule of law as its deployment domestically often contravened existing legal frameworks; (2) shielded the armed forces from pressures to reform; (3) worked against the development of civilian capacities; and (4) undermined public confidence in the efficacy of democratic systems and civilians’ ability to solve problems. This perspective offers a powerful counterargument to the widely-shared position that justifies the military's internal role together with its own role conception on pragmatic grounds, pointing to its logistical capacity and personnel strength, together with the chronic weakness and financial constraints of Latin American states. Smaller militaries with a similar budget would allow for substantive modernising reforms. Yet, downsizing would spark conflict with the military, leave a considerable number of people out of work and deprive governments of a wildcard with an immense capacity for human and territorial deployment. Given these likely consequences, pragmatism has maintained the upper hand though it has come at a cost for the region's quality of democracy.

The study further adds to the civil-military relations literature in that it shows that internal missions are not only the outcome of immediate threats to sovereignty and order from within the state (for example, social unrest, terrorism, and organised crime), which in turn affect civil-military relations in negative ways. Instead, we show that it has been the use of the military as a wildcard to assume whatever function civilian institutions were unable to carry out that has yielded such harmful effects. In this context, it is relevant to restate that it has often been civilians who pulled the military into an ever-broader set of missions. On its part, the military appears to have played a rather passive role accepting what it allowed it to maintain its budget, size, and privileges. This insight sits uneasily with the position of those who have categorically opposed any deployment of the military beyond external defence on the grounds that it would turn Latin America's predatory militaries into a ticking time bomb that will end democracy. The argument advanced here is situated in between the categorical and the pragmatic view. While our focus has been on the defence of democracy, this focus is not limited to democratic survival but sheds light on its functioning, performance, and quality. The misuse of the military as a wildcard to fill in where civilian state capacity is lacking causes and prolongs severe democratic deficits. Over time, these could well lead to a return to praetorianism.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for constructive feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript that were provided by Lindsay Cohn, Christoph Harig, Yagil Levy, Anit Mukherjee, Chiara Ruffa, and Nina Wilén. We further thank the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to improving the manuscript as well as Camila Bertranou and Fiorella Ulloa for their excellent research assistance. Nicole Jenne gratefully acknowledges funding from the Chilean National Research and Development Agency (ANID), Fondecyt Regular No. 1210067 (2021). Rafa Martínez gratefully acknowledges funding from the Spanish State Research Agency (PID2019-108036GB-100 / AEI / 10.1339 / 501100011033).

Nicole Jenne is an Associate Professor at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Institute of Political Science. She holds a PhD in International Relations from the European University Institute (EUI), Florence, Italy. Author’s email: njenne@uc.cl.

Rafa Martínez is Professor of Political Science at the University of Barcelona. He was a Research Fellow at University of Pau (France), FNSP (Paris, France) and the University of California-Riverside (USA). He received the National Prize of Research given by the Ministry of Defence of Spain (2002). His main publications are: Los mandos de las Fuerzas armadas españolas del siglo XXI (Madrid: CIS, 2007) (Best Book Award 2008 for the Spanish Association of Political Science); 'Objectives for democratic consolidation in armed forces', in David Mares and Rafael Martínez (eds), Debating Civil-Military Relations in Latin America (Brighton, Sussex: Academic Press, 2013) (Best Chapter Award 2015 for the Spanish Association of Political Science); 'Subtypes of coups d’état: recent transformations of a 17th century concept', Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, 108 (Best Article Award 2015 for Defense, Public Security and Democracy Section of Latin America Studies Association) and with David Pion-Berlin, Soldiers, Politicians and Civilians: Reforming Civil-Military Relations in Democratic Latin America (Cambridge University Press, 2017) (Best Book Award 2019 for the Spanish Association of Political Science and 'Giueseppe Caforio ERGOMAS Award' for Best Book 2019). Author's email: rafa.martinez@ub.edu.