Introduction

This article adopts a mixed methods ‘pathways’ approach to explore the interactions between multiple exclusion homelessness (MEH) and mental health. It seeks to understand the prevalence of mental health issues amongst people experiencing MEH; and consider how people experiencing homelessness understand the role of mental ill-health in their homelessness pathways. Despite evidence showing positive associations between mental health and MEH, there is a clear need to strengthen the current evidence base in terms of the interactions and complexities between the two experiences using a more dynamic ‘pathways’ approach. The value in such an approach is in its ‘dynamic and holistic nature and its foregrounding of the voices of homeless people themselves’ (Clapham, Reference Clapham2003: 127).

MEH has long been central to conceptualising interactions between ‘homelessness’ and other forms of ‘deep social exclusion’ (institutional care, substance misuse, and participation in ‘street culture’ activities (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Bramley and Johnsen2013)), and can be defined as the combination of an experience of homelessness (rough sleeping, squatting or living in insecure accommodation) with one or more indicator of deep social exclusion (problematic substance use, chronic mental or physical ill-health or an institutional background) (Bowpitt et al., Reference Bowpitt, Dwyer, Sundin and Weinstein2011). Earlier references to the term within the UK literature come from a call for a research programme (funded by the Economic and Social Research Council) on the lived experiences of multiply disadvantaged homeless people (Carter, Reference Carter2007). The shorthand emerged from endeavours to characterise the specificity of homelessness that occurs in conjunction with other needs and exclusions. Studies have noted not only the overlapping nature of such exclusions but their ‘mutually reinforcing causal inter-relationships’ (Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick2005; Bowpitt et al., Reference Bowpitt, Dwyer, Sundin and Weinstein2011; Cornes et al., Reference Cornes, Joly, Manthorpe, O’Halloran and Smyth2011; Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Johnsen and White2011; McDonagh, Reference McDonagh2011; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Morris, Scullion and Somerville2012). The term ‘MEH’ is neither the first nor sole attempt to encapsulate this experience; in the US, the term ‘chronically homeless people’ has long been in use (Kuhn and Culhane, Reference Kuhn and Culhane1998), and, since its origin, has appeared in various guises (more recently, as ‘severe and multiple disadvantage’, Bramley et al., Reference Bramley, Fitzpatrick, Edwards, Ford, Johnsen, Sosenko and Watkins2015).

While MEH is an important concept for understanding the multiple and overlapping needs of people experiencing homelessness, there are a number of areas where it requires development. MEH within England needs to be updated to reflect the rapid changes in context since 2010, as the main body of academic investigation into the concept was conducted prior to the recent growth in rough sleeping (the exception is Bramley et al.’s Reference Bramley, Fitzpatrick, Edwards, Ford, Johnsen, Sosenko and Watkins2015 work on ‘severe and multiple disadvantage’). According to official estimates, the number of rough sleepers in England increased by 169 per cent between 2010 and 2017 (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Pawson, Bramley, Wilcox, Watts and Wood2018). This spike in rough sleeping led to a political consensus on the need to act. Exactly how to address homelessness is currently a high domestic priority, but divergent views exist on which policy response would be most effective. In England, policies designed to address homelessness include the introduction of the Homelessness Reduction Act in 2017, funding for private rented access schemes and the announcement of pilots of Housing First Footnote 1 . This reflects the gathering momentum and growing cross-party interest in Housing First within England as a potential policy solution for so-called ‘entrenched’ rough sleeping (Conservative Party, 2017; Labour Party, 2017). The initial commitment to Housing First from central government was limited to three pilots despite international evidence for its effectiveness (Tsemberis, Reference Tsemberis2010; Aubry et al., Reference Aubry, Nelson and Tsemberis2015; Woodhall-Melnik and Dunn, Reference Woodhall-Melnik and Dunn2016; Kerman et al., Reference Kerman, Sylvestre, Aubry and Distasio2018). Delivering an effective policy response such as Housing First requires a clearer grasp of the number of people experiencing homelessness and a deeper understanding of their needs and experiences. In particular, policymakers need to understand whether the growth in rough sleeping is associated with changes in other domains of exclusion.

An important component of MEH is mental health. An association between mental ill-health and homelessness is clearly identified within the MEH literature, the most seminal examples being Fitzpatrick et al.’s (2011; Reference Fitzpatrick, Bramley and Johnsen2013) articles which explore the extent and patterns between forms of social exclusion thought to interact with homelessness (including substance misuse, institutional care, and ‘street culture’ activities), and the nature and causes of MEH, respectively. However, these studies are predominantly quantitative and while essential to provide a statistically robust account, the present study aims to give a more in-depth qualitative insight into the nature of individual experiences of mental health within MEH. Further, Fitzpatrick et al. (Reference Fitzpatrick, Bramley and Johnsen2013) identify five clusters of experience within the MEH population – one of these being ‘mental health and homelessness’ (accounting for around one-quarter of the cohort). The research also identified high levels of mental health issues across different clusters of MEH (see Table 1). More than 85 per cent of people were ‘very anxious and/or depressed’ across four of the five clusters. While this highlights the importance of mental health within MEH, it uses only two limited measures of mental ill-health: self-reported feelings of anxiety/depression and self-reported mental health issues. This research provides a more detailed measure of mental health (as outlined in the Methodology section) alongside qualitative interviews with homeless people experiencing mental ill-health, and therefore attempts to provide a more in-depth, dynamic and nuanced understanding of the sequencing and interaction between mental ill-health and homelessness.

Table 1 The prevalence of mental ill-health across MEH clusters (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Bramley and Johnsen2013)

Clapham’s (Reference Clapham2003) concept of ‘housing pathways’ informs the approach to the qualitative work, which traces biographic housing, mental health and service use histories of individuals experiencing homelessness. The pathways approach offers a dynamic framework through which to understand the fluid movement through MEH and mental health, which is difficult to explore through quantitative methods alone (and may not have been revealed in previous studies on MEH as a result). The research sought to assess the role of mental ill-health within pathways into MEH, through a focus on the following research questions:

1. What is the prevalence of mental health issues in MEH?

2. How do homeless people understand the role of mental health in their homelessness pathways?

Mental ill-health and homelessness

High levels of mental ill-health amongst homeless people have been recorded by a range of different studies (Rees, Reference Rees2009; Reeve and Batty, Reference Reeve and Batty2011; Homeless Link, 2015; Dumoulin et al., Reference Dumoulin, Orchard, Turner and Glew2016). A systematic review of academic research from Western Europe and North America found a higher prevalence of mental health issues amongst homeless people than within the general population (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Khosla, Doll and Geddes2008). In particular, the review noted high levels of ‘major mental disorders’ such as ‘psychotic illness’ and ‘personality disorder’. This review identified considerable variation across different contexts, concluding that ‘service planning should not rely on our summary estimates but commission local surveys of morbidity to quantify mental health needs’ (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Khosla, Doll and Geddes2008: 1676). One of the difficulties for the review was that most research on homelessness included only a limited number of questions about mental health. At the same time, research on mental health rarely gathered sufficient information about housing status to extrapolate data specifically for those who are homeless. There was a need for research that investigated both mental health and homelessness in greater detail. In particular, Fazel et al. (Reference Fazel, Khosla, Doll and Geddes2008) highlighted the need for local surveys that could investigate a specific context.

The most comprehensive evidence of mental ill-health amongst people experiencing homelessness in the UK came from a survey of over two thousand homeless people. In 2014, Homeless Link found that many severe mental health conditions were at least twice as common amongst homeless people when compared to the general population (Homeless Link, 2014). A major difficulty for research into mental health and homelessness relates to causation. One-off surveys are unable to assess the temporal ordering of the emergence of mental health issues and homelessness. Are high levels of mental ill-health the cause or consequence of homelessness?

Research into homelessness pathways can provide some evidence on this question of causation. Fitzpatrick et al. (Reference Fitzpatrick, Bramley and Johnsen2013: 148) argue that:

[…] the temporal sequencing of MEH-relevant experiences is remarkably consistent, with substance misuse and mental health problems tending to occur early in individual pathways, and homelessness and a range of adverse life events typically occurring later.

Their research emphasises the role of childhood poverty, trauma and mental health issues in MEH pathways, suggesting that:

[…] the strong inference is that these later-occurring events [homelessness] are largely consequences rather than originating causes of MEH, which has important implications for the conceptualisation of, and policy responses to, deep exclusion (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Bramley and Johnsen2013: 148).

Emerging research has highlighted the interaction between mental ill-health and MEH and begun to unpick the likely direction of causation between these factors. This article seeks to develop understandings of these links with particular reference to temporal ordering and patterns of risk. Detailed understanding of these factors is crucial in designing policies and interventions effective in responding to homelessness.

Methodology

This article presents findings from mixed methods research that had the overall aim of exploring the mental health of homeless people in Nottingham City, England. The research was commissioned by Nottingham City Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) following a tendering process, and ran from November 2016 to January 2018. This research adopted the type of detailed, local approach recommended by Fazel et al. (Reference Fazel, Khosla, Doll and Geddes2008). It combined a broad assessment of different measures of mental ill-health with qualitative investigation into pathways through homelessness and mental health.

The terms ‘homelessness’ and ‘mental health’ are used variably so it is important to clarify their definitions for the purposes of this study. We adopted the legal definition of homelessness in England which was first set out in the Housing (Homeless Persons) Act 1977 Footnote 2 , and states that an individual is homeless if they have no accommodation available for their occupation that they are entitled to occupy and that it is reasonable to expect them to occupy. This was considered to be useful as a broad working definition of homelessness for the purposes of this study as it includes people sleeping rough, squatting, staying in temporary accommodation (hostels, B&Bs, interim supported housing, night shelters) as well as those in other, more ‘hidden’ temporary housing situations such as staying with friends and family (‘sofa surfing’). Due to the services accessed and the client’s brief, the sample is dominated by single homeless people.

An inclusive definition of mental ill-health was employed, which ranges from mental disorder through to poor mental wellbeing. However, the survey was designed to ensure we could distinguish different types and severities of mental ill-health. The survey consisted of thirty-one questions that investigated the respondent’s housing situation, mental health and wellbeing, use of services, and demographic characteristics. Where possible, questions mirrored existing secondary data sources to allow for comparison to wider populations.

The survey was completed by 167 people with a recent experience of homelessness (currently or in the past six months) and survey participants were recruited through services working primarily with single homeless people Footnote 3 (which reflected Nottingham City CCG’s original emphasis for the study). The survey protocol, design and questions were based on the Homeless Health Needs Audit, a national framework for gathering and using information about the health needs of people experiencing homelessness, developed by Homeless Link and Public Health England Footnote 4 . Following the method used in the Homeless Health Needs Audit, the survey was designed for the interviewer and participants to complete together in a one-to-one setting. It is argued that involving people with direct experience of homelessness helps to ensure the process is as relevant and reflective of their experiences as possible. Participants were fully briefed on the reasons for the survey and what to expect – via a participant information sheet – to improve the level of meaningful data collected.

Fieldwork was conducted within Nottingham City local authority area at a time when homelessness in Nottingham was increasing (Nottingham City Council, 2017). This reflected the growth in homelessness across England prior to the research (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Pawson, Bramley, Wilcox and Watts2017). Survey fieldwork was conducted in a range of generic homelessness services spanning voluntary and community sector and local authority providers (services included homelessness hostels, night shelters, day centres, refuges, temporary supported housing schemes, street outreach, and council housing services). No specialist mental health services were included so as not to skew the results towards people with mental health issues. Two-thirds of respondents (66 per cent) spent the previous night in a hostel, night shelter or Bed and Breakfast accommodation (other responses were: slept rough, 5 per cent; sofa surfing, 10 per cent; temporary accommodation, 10 per cent; other, 9 per cent). This meant that the survey sample focused on more vulnerable homeless people who were likely to have experienced MEH. The majority (68 per cent) of survey respondents were male, while 30 per cent were female. Respondents were of varying ages, with the majority aged between thirty-five to forty-nine years. Footnote 5

A degree of caution is required when interpreting some of the survey results, particularly with regard to general demographic characteristics. Surveying the single homeless population (and hard-to-reach and non-household populations in general) for whom no suitable sampling frame exists raises methodological challenges in terms of obtaining a representative sample. In this case, there were no reliable data on the profile of the local single homeless population. Since a direct list of individuals belonging to the target population was not available, the sampling strategy could not be based on a classic direct sampling approach.

The survey methodology employed here is similar to that used by other surveys of homeless people: namely, through the selection of places (services) frequented by single homeless people. The methodology used for this study therefore presents some limitations. The first relates to potential under-coverage of the population, in that those who do not use the services targeted for the survey may have been missed. The gender profile of the sample, for example, will have been influenced by the services in which surveying took place. Some services were mixed but others were gender specific. While the study team actively targeted some women’s services towards the end of the fieldwork (resulting in an additional eleven surveys being completed by women), there may be some groups who find existing services unwelcoming, or threatening, or not adequately able to meet their needs and so may be under-represented in any survey of homeless people. We know, for example, that women can be deterred from using homelessness day centres and night shelters (Reeve et al., Reference Reeve, Casey and Goudie2006) and this may also apply to other groups – for example, LGBT+ people, some black and minority ethnic groups and disabled people.

The second issue relates to over-coverage due to the fact that the population accessed at the services does not reflect the true target population. Survey participants were recruited through services primarily working with single homeless people; but some services (day centres, for instance) may also on occasion be accessed by families. This was also a ‘snapshot’ survey conducted within a small window of time between February and May 2017 and cannot claim to be representative of all homeless people in Nottingham.

After the survey, in-depth biographical interviews were conducted with homeless people with mental ill-health. Participants met an inclusive definition of mental ill-health (ranging from mental disorder to poor mental wellbeing). Interviews took a ‘biographical’ pathways approach, talking through respondents’ housing, health, and service use pathways since childhood. Following Clapham (Reference Clapham2003: 123), we believed the pathways approach to be an ‘illuminating tool’ to shed light on ‘factors that lead to homelessness, influence the nature of the experience, and enable some people to move out of it’.

In total, thirty-seven interviews were conducted. Participants were recruited through the survey, through the organisations that had participated in the survey and through other housing services in contact with people with mental ill-health purposely targeted to maximise the diversity of the sample across a range of criteria. This included people with and without a diagnosis of a mental health condition (but who identify as having mental health issues); with experience of being detained under the Mental Health Act; experience of rough sleeping; in a range of age groups; with different minority ethnic backgrounds, or gender; and with a range of different mental health issues. These findings were triangulated alongside twenty-three interviews with local stakeholders working at strategic, managerial, and front-line levels in a range of organisations across health service providers, the local authority and voluntary sector.

Findings

Prevalence of mental health issues

The findings from the survey and interviews are presented in two sections to reflect the research questions. This first section highlights the prevalence of mental health issues amongst survey respondents. Mental ill-health was prevalent amongst respondents, with three quarters indicating that they had experienced mental health issues. This included respondents who ‘self-reported’ (i.e. agreed with the statement ‘I have mental health issues’), and/or indicated that they had been diagnosed with a specific condition, and/or reported having been detained under the Mental Health Act. Taking each of these overlapping indicators of mental ill-health separately:

62 per cent of respondents agreed with the statement ‘I have mental health issues’ which was used as an indicator of current, self-reported mental ill-health.

74 per cent of respondents reported being diagnosed with a mental health condition by a doctor or health professional at some point in time.

19 per cent of respondents had been detained under the Mental Health Act at some point in their life. This indicated a severe mental health issue and is popularly known as being ‘sectioned’. Four per cent of the respondents had been detained within the previous twelve months.Footnote 6

Survey respondents were asked the question ‘Has a doctor or health professional ever told you that you have any of the following conditions?’ and were presented with a list of mental health issues. The most common diagnoses were ‘depression’ (61 per cent) and ‘anxiety disorder or phobia’. A significant minority of respondents had received diagnoses of what are often termed ‘severe’ mental health issues including ‘personality disorder’ (17 per cent), ‘psychotic conditions, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder’ (15 per cent), ‘post-traumatic stress disorder’ (15 per cent) and ‘dual diagnosis’ (24 per cent).

These figures can be compared to assessments of the prevalence of self-reported mental ill-health amongst people who have experienced homelessness and the general population. Survey findings corroborated monitoring data from a local homelessness service showing that, in 2014, 75 per cent of 159 residents had a mental health diagnosis (Framework, 2014). Other research with people facing multiple disadvantages in Nottingham identified high levels of mental ill-health (Bowpitt and Kaur, Reference Bowpitt and Kaur2018). Tracking data from street outreach workers suggested that 51 per cent of people who were sleeping rough reported current mental health issues. Data on local rates of mental health disorders are not particularly robust, which makes it difficult to benchmark survey results against the local population with complete accuracy. In addition, local recording of mental health conditions is reported to vary widely. In 2015/16, the prevalence of depression was recorded as 8.6 per cent of adults within Nottingham City (NHS England, Reference England2017) and the prevalence of psychosis was found to be 1.0 per cent. These figures are much lower than rates of mental disorders found amongst this survey sample (61 per cent and 15 per cent respectively). Possibly the most useful comparator with the wider population is detention under the Mental Health Act. This provides clear indication of very severe mental ill-health. Direct comparison with the survey should be treated with caution but suggests that detention of respondents under the Mental Health Act was around fifty times more common than amongst the general population. Footnote 7

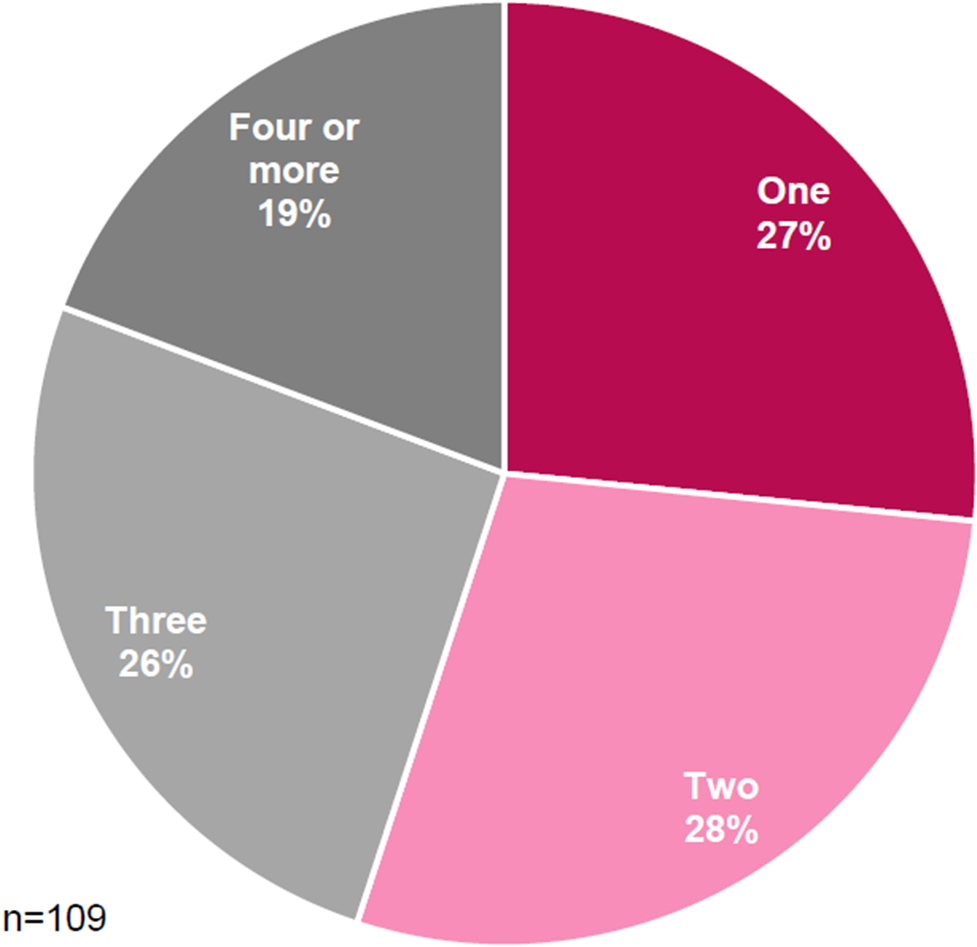

Exploring respondents’ mental health diagnoses in more detail reveals a picture of multiple mental health needs. Almost three-quarters (73 per cent) of respondents with a diagnosed mental health issue reported having received more than one diagnosis (see Figure 1). Almost two thirds (63 per cent) of respondents with mental health issues had a diagnosis of a ‘severe’ mental health condition (i.e. a condition other than depression and/or anxiety). This means that almost half (46 per cent) of all survey respondents had a diagnosis of a ‘severe’ mental health condition.

Figure 1. Number of mental health diagnoses (respondents with a mental health diagnosis only)

The qualitative interviews provide additional evidence of the multiplicity of mental health issues amongst this population. Many interviewees talked about having depression and anxiety alongside other conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder, psychosis and personality disorder, with self-harming, eating disorders and dual diagnosis also relatively common.

Mental health and homelessness pathways

The subsequent sections explore participants’ mental health needs in greater depth, drawing on insights from the qualitative data from homelessness service users with mental ill-health in Nottingham. In these interviews, researchers were able to explore in detail the interaction between respondents’ mental health and their housing situations, and obtain a chronological ‘life story’. While each individual’s mental health trajectory is unique to their personal history and circumstances, a number of broad patterns emerged from the interviews with people who had experienced both homelessness and mental ill-health. Four key similarities emerged which related to the onset and triggering of mental health issues which are explored here. The first was that there was a long history of mental ill-health. Respondents had commonly experienced mental health issues for many years, often since childhood. A second was that mental ill-health had been triggered by a specific event, or ongoing trauma, rather than developing independently of life experiences. Thirdly, pre-existing mental health issues were exacerbated by life events including stress, trauma and homelessness. The final common theme was that drugs and alcohol were sometimes used to mediate the effects of other difficulties, including mental ill-health. These themes are explored further in the following sections.

Histories of mental ill-health and trauma

Virtually all respondents traced their mental health issues to a time that predated their first period of homelessness. Many had long histories of mental ill-health, albeit fluctuating in severity and manageability. Common across all interviews – regardless of when the onset of mental health issues occurred – was a history of traumatic and difficult life events and personal circumstances that laid people open to mental health issues and homelessness. For the majority of respondents, the onset of mental health issues was attributed to ongoing trauma, often beginning in a childhood characterised by abuse, neglect, and violence – as the following quotes illustrate:

When I was young I had got depression, anxiety […] what me mum and dad did to me, they wouldn’t let me in the house and that (Jimmy)

I’ve had it for years, from what mum’s done, what my ex-partner’s done, I’ve been sexually abused as a child, been forced into prostitution (Michelle)

I think it started from a very young age but I didn’t know, feeling neglected, I practically raised myself from a young kid (Nicole)

Leona described how she endured racially-motivated bullying and victimisation while at school, and this, combined with an unstable home life, contributed to the onset of her mental health issues, anger and low self-esteem:

I think that’s why everyone says I need a counsellor so I can talk about my issues, I think nobody ever likes, even if they talk to me I still think they don’t like me (Leona)

For other participants, it was a very specific event such as a violent personal assault, relationship breakdown, bereavement, or traumatic experience that triggered the onset of mental health issues. Dara, a refugee who had been living in England for sixteen years said his mental health issues (depression and schizophrenia) developed following the death of his close friend. Subsequently his mental health deteriorated and Dara was sectioned and prescribed medication. Derek, meanwhile, traced his depression and anxiety to the breakdown of his marriage and the heavy drinking that followed. Other respondents similarly linked the onset of their mental ill-health to the loss of important relationships and the sense of isolation that ensued:

I never drank when I was bringing my kids up but they started leaving home […] I got depression big time (Judy)

Very first time [was] fifteen years ago when I had the mental breakdown; I finished a relationship and things didn’t go as well. I cracked up, I was drinking and taking medication on top and I couldn’t cope no more, just went to pieces (Mick)

Amongst those who attributed their mental health issues to events later in life, domestic violence often featured as a factor. This was true, for example, of Collette:

You start to see that it’s [domestic violence] destroying every aspect of your life and I was getting quite suicidal and overdosed on a couple of occasions whilst I was with him […] I think for many years I had mental health problems and when my daughter fell pregnant and left home, I’d been on my own for quite a number of years and I felt totally lost […] When I met X I felt I could hide in his world […] I fell very quickly into a relationship with a man I didn’t know that well but I was vulnerable and not very strong in my mental health and abusing a lot of Diazepam […] so I wasn’t in a good place when I met him (Collette)

It is evident from Collette’s articulation of her deteriorating mental health, that respondents’ mental health trajectories were not always clear-cut, or linear, and they could not always pinpoint ‘causality’. For many, a complicated combination of factors led to periods of mental ill-health of fluctuating severity. In Collette’s case this included her daughter leaving home, isolation, a violent relationship and abusing prescription drugs.

Respondents’ lives and histories were characterised by a multitude of adverse and traumatic experiences, often occurring in childhood but sometimes in later life, which laid people open to mental health issues and homelessness.

Exacerbation of mental health issues by homelessness

Homelessness and inadequate housing situations had a further detrimental impact on mental health and exacerbated existing conditions. Although mental ill-health tended to precede homelessness, the experience of homelessness itself could bring people to the point of mental health crisis. The stress associated with losing the home and family as well as the stress of having to adjust to temporary accommodation and, often chaotic, insecure and/or unsafe living environments led to this effect. The description Freddie (who had depression, anxiety and ADHD) gives of the impact of homelessness on his mental health was fairly common:

I’d say they [mental health issues] were kind of there before, but it wasn’t that bad and then I became homeless and they just got worse, went downhill. (Freddie)

Some respondents described the experience of becoming homeless (and/or entering homelessness accommodation) as engendering a mental health crisis, although all had pre-existing mental health conditions. For example:

…the day they told me I was coming in here [hostel] I had a nervous breakdown, I was crying, they went ‘it’s not as bad as it’s cracked up to be’. It’s worse (Denise)

Particular (overlapping) issues associated with homelessness that impacted on interview respondents’ mental health were: loss (of home and family); isolation and loneliness; feelings of worthlessness; insecurity and frequent moving; and the homelessness environment (general needs, temporary accommodation, the streets).

It was partly the isolation of living in hostels that prompted Jasmine to resume self-harming. Others talked about feeling isolated from friends and family, being alone, and this impacting very negatively on their health and well-being. Respondents often knew no-one in their new environment, and had no support networks there.

Respondents also reported strong feelings of despair, hopelessness and loss in the context of their homelessness. They expressed emotional distress at their changed situation and described ‘giving up’ as a result. Regardless of the circumstances under which they became homeless a sense of self-blame was implicit. Respondents often explicitly connected these feelings with deteriorating mental health. Talking about her experience of living in a general needs hostel, Leona, whose young son was temporarily staying with her mother, expressed feelings of not belonging and feeling like a ‘wasted person’:

Cos I’m a mum I feel like I need to be able to still do things like a mum, feel like I belong, at the moment I feel like I’m a wasted person…it’s all I’ve done since I was sixteen (Leona)

Although she had also faced multiple difficulties earlier on in life, it was becoming homeless, losing her son, and falling through the cracks of various services that made Leona feel like giving up on life:

Being homeless and being through all these systems made me give up on life, I didn’t give up on life until I came along this and then I feel like what’s the point, I asked for help, I lost my son, I lost my house and I feel like there’s no point now (Leona)

Moving frequently also brought feelings of insecurity. Jasmine noted a clear correlation between her housing situation and her mental health, which was ‘at its worst when I had nowhere’. She went on to explain more precisely what affected her about being homeless and insecurity was at the heart of her distress:

…not knowing where I was going to be from one day to the next, cos I stayed in three different hotels in eight weeks and it was not knowing where I was going to be (Jasmine)

Finally, the environment of temporary accommodation – most notably, large general needs hostels – was detrimental to mental health. Most found temporary accommodation frightening and isolating. Respondents described environments where noise, drug use, alcohol use, and violence were commonplace and also found the chaos, insecurity, and surveillance extremely challenging:

This place is challenging on all levels […] you sit in a room and you get depressed cos you can’t face all the other energies in here […] I find I’m more anxious. I have no patience and drinking a lot more as well, every day (Nicole)

It’s more like people that stress me out more than rules and stuff, I just go to my room and ignore it but it’s the residents cos some of them are young and still going on like they’re in jail or on the streets (Leona)

Some respondents talked about the way in which hostel environments triggered distressing memories, or other conditions (eating disorders, self-harming). One respondent who had fled domestic violence spoke of how the hostel surveillance evoked the way her ex-partner would seek to control her. Collette, meanwhile, had an eating disorder and, because of that, ‘to have to share a kitchen [in the refuge], it was just hugely stressful’. Respondents who had experienced violence in their lives reported the extent to which hostels were also sites of violence. Those interviewed spoke of witnessing acts of physical brutality. The nature of the hostel environment therefore could trigger traumatic memories or generate new memories of violence.

A common response to the challenge of living in temporary accommodation was for respondents to remain in their room or spend time elsewhere. Jasmine, for example, explained that ‘I try to stay out as much as possible’. However, this could increase isolation which some found detrimental to their health and wellbeing.

The mediating effect of drugs and alcohol

It is important to emphasise the complexity of the interrelation between homelessness, mental health and drug or alcohol misuse. Amongst respondents, a clear linear trajectory could sometimes be traced, for example, from trauma, to mental ill- health, to drug or alcohol misuse, to homelessness, but it was usually more complex. For example, drugs and alcohol were used by some to ‘self-medicate’ for mental health issues, but also to numb traumatic experiences (themselves a trigger for mental ill-health in many cases), including homelessness.

It [Ketamine use] was recreational back then…it became heavy use and when I came back from Leeds that’s when I started injecting it, cos I was extremely depressed, I was extremely upset for the best part of a year, I felt suicidal every day over the relationship breakdown and I just got worse and worse on the Ketamine [I: so was there a link between your increased use of Ketamine and your feeling of depression?] I think so, definitely, cos the K just numbed it. (Rosie)

Jimmy started drinking in childhood when he ran away from local authority care and found himself sleeping rough. He found that alcohol helped him cope with being on the streets (a long-term alcohol and drug dependency followed). Denise described conditions in the hostel and talked about how difficult she found the environment. When asked what strategies she used to deal with this she responded by saying simply, ‘I drink’. Others used drugs or alcohol to ameliorate the emotional distress caused by other difficulties. Judy, for example, reported ‘using drugs to numb the pain’ associated with a series of traumatic life events. It was common for respondents’ increased alcohol or drug consumption to go in tandem with deteriorating mental health, typically following a traumatic episode, such that the two were intrinsically linked and seeking ‘cause and effect’ is difficult. In some cases, erratic, violent, or anti-social behaviour ensued and respondents became homeless because those with whom they lived, or their landlord, could no longer cope with their behaviour. Derek was asked to leave by his mother, Mick was asked to leave by his sister and Leona was evicted for anti-social behaviour. In other cases, rent arrears accrued as respondents ceased prioritising domestic responsibilities and became focused mainly on buying and using drugs or alcohol.

Respondents in recovery from drug or alcohol dependencies faced additional challenges in temporary accommodation. They talked about the ease with which they could obtain drugs and alcohol and how that was undermining the support they received:

They [addiction service] try to help me but I relapse again cos living in here is very difficult…I can’t help thinking if I wasn’t in this position it [the support] would work quite well (Simon)

This section focused on exploring the complex relationships between mental ill- health, drug and alcohol misuse, and homelessness, as they emerged through the biographical interviews. In this case, drug and alcohol use, homelessness, and mental ill-health were each a cause and a consequence of the other, sometimes cyclically. Mental ill-health alongside drug/alcohol misuse emerged together following difficult life experiences, with drugs/alcohol being used both to manage mental ill-health and to numb emotional pain. There are clear implications here for supporting and treating homeless people with dual diagnosis. Because drug and alcohol misuse and mental ill-health are often so entangled, and sometimes rooted in the same traumatic experience, it is difficult for people with dual diagnosis to disentangle them in order to address them separately or sequentially.

Discussion and conclusions

While previous studies have identified high levels of mental ill-health amongst people experiencing homelessness compared to the general population, most homelessness studies include only a very limited number of questions about mental health, and those tend to be non-specific. Studies are less prevalent that have qualitatively explored the nuances of how mental health is experienced by people who are homeless. Furthermore, most literature on risk factors for homelessness tends to focus on independent risk factors with less attention to how they interplay and accumulate over the life course. Recognising the weaknesses of existing evidence and datasets, a key objective of this study was to explore the scale and nature of mental ill-health amongst the homeless population in Nottingham City. This article has presented results on the prevalence of mental ill-health alongside insight on the specificities of particular mental health issues, the temporal ordering of these experiences, and their interrelationship with homelessness experiences.

The findings presented in this article focused on two research questions to assess the role of mental ill-health within pathways into MEH, as stated below:

1. What is the prevalence of mental health issues in MEH?

2. How do homeless people understand the role of mental health in their homelessness pathways?

First of all, the findings investigated the prevalence of mental ill-health amongst people experiencing MEH. The survey identified high levels of mental ill-health using a range of different measures. These findings were consistent with previous research on populations experiencing homelessness. In addition, the survey highlighted very high levels of severe mental ill-health as evidenced by detention under the Mental Health Act. One of the key findings was the prevalence of multiple mental health issues. The second research question provided greater depth to the body of research on MEH by focusing on how people understand the role of mental ill-health in their homelessness pathways. These pathways were characterised by long, complex histories of mental ill-health which had often been triggered by a specific event, or ongoing trauma. Pre-existing mental health issues were exacerbated by life events, including homelessness. Drugs and alcohol were sometimes used to mediate the effects of difficulties, including mental ill-health. When respondents’ experiences are viewed as a whole it is clear that most had been through a multitude of traumatic events and adverse experiences, associated with deep exclusion and which resulted in significant support needs. Both mental ill-health and homelessness were closely associated with adverse life experiences and could not have been viewed in isolation from them.

These research questions can be drawn together to consider the role of mental ill-health within pathways through MEH. The findings highlight high levels of serious mental ill-health amongst people experiencing MEH. This mental ill-health is more complex and serious than has been identified by previous research on MEH. Key evidence from the qualitative interviews highlights the timing of mental health issues within homelessness pathways. Mental ill-health commonly emerged after one or more traumatic experience but prior to homelessness. This causal pathway should not be over simplified. There was evidence that mental ill-health fluctuated over time and interacted with repeated episodes of homelessness.

This article provides further evidence on the deep interconnections between mental ill-health and homelessness which are commonly preceded by traumatic life experiences. The high levels of severe mental ill-health observed amongst survey respondents were striking. The findings hint at root causes which go beyond the negative impact of homelessness on mental health, and have a number of implications for social policies aimed at responding to homelessness. First, they highlight the value of MEH as a concept central to policy development in thinking through the interconnections between homelessness, mental ill-health and forms of deep social exclusion. The findings in this article also highlight the need for a holistic policy response that encompasses homelessness, mental ill-health and other experiences of exclusion. Housing First is gathering momentum as a response for the cohort of people identified in this research. However, given the evidence that traumatic incidents are common precursors to both homelessness and mental ill-health, we suggest that housing provision through this model needs to be accompanied by additional trauma-informed support in order to be effective for people experiencing MEH. The findings suggest that we will be unable to address homelessness without addressing the underlying trauma that so often precedes and accompanies it.

This exploratory research has focused on one city in England, though the findings are likely to be transferable to other cities with similar high levels of homelessness and rough sleeping. The findings also suggest that more detailed investigation into the pathways into and out of homelessness and the relationships between homelessness and different domains of exclusion would be beneficial. This is an urgent task for both academics and policymakers in England given the rapid increase in rough sleeping since 2010.

At a broader level, this research highlights the need for international comparison of the prevalence and characteristics of MEH. Our research provides detailed analysis of one context but there is insufficient evidence to explain the variation in mental health issues amongst homeless people identified by meta-analysis such as Fazel et al. (Reference Fazel, Khosla, Doll and Geddes2008). International comparison of mental ill-health amongst people experiencing homelessness should form one part of a wider investigation into the nature and prevalence of MEH across different countries. A clearer understanding of MEH in different countries would provide evidence of where and when policy responses such as Housing First are likely to be most effective. Understanding the experiences and needs of people who experience both homelessness and other forms of exclusion should be at the heart of a concerted policy response to support people who have often experienced serious trauma earlier in their life.

Acknowledgments

I would like to pay my gratitude and respects to my co-author, friend and colleague, Dr. Ben Pattison, who passed away on the 19th March 2020. Ben was a dedicated researcher at the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, at Sheffield Hallam University, where I had the privilege of working with him on a range of housing projects over the past five years. Ben was a deeply honoured member of the housing studies community, and will be remembered for his contributions to topics as diverse as homelessness, social lettings, Housing Benefit, the housing options of younger people, and mental health and homelessness; his passion to help those most disadvantaged by the inequalities within our society’s housing system; his tremendous support for junior researchers; and more than anything, his kindness and generosity as a person.