Introduction

Periorbital swelling secondary to rhinosinusitis is a common condition, particularly in children.Reference Pereira, Mitchell, Younis and Lazar1 Due to the close anatomical proximity of these structures, infection can easily spread. It is important to promptly determine the cause and extent of disease, as these will affect the patient's subsequent management.

Periorbital cellulitis can be categorised using Chandler and colleagues' classification system.Reference Chandler, Langenbrunner and Stevens2 This can be used as an indicator of disease severity, with due consideration to potential ophthalmological and neurological sequelae.

We present a rare and potentially dangerous case of periorbital cellulitis with secondary lacrimal gland abscess, in a 15-year-old boy. There have been few reports of this condition, with only two previously reported paediatric cases.Reference Patel, Khalil, Amirfeyz and Kaddour3, Reference Guss and Kazahaya4

Case report

A 15-year-old boy with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder presented to the emergency department with a one-day history of a swollen, erythematous, painful left eye. He was diagnosed with periorbital cellulitis and was discharged from the emergency department on oral antibiotics (co-amoxiclav), as he was considered clinically stable and was keen to return home.

However, his initial presentation failed to settle with medical management. Two days later, the patient re-presented to the emergency department with worsening swelling and pain around the left eye, together with pyrexia, but with normal inflammatory markers (i.e. white blood cell count and C-reactive protein). He had no associated photophobia.

On examination, the patient had a grossly swollen left upper and lower eyelid, with no pus or discharge. He had normal eye movements and no diplopia. His vision was 6/6 bilaterally, and fundoscopy was normal. A fibre-optic nasoendoscopic examination of the nose confirmed the presence of pus in the left middle meatus.

Therefore, our clinical impression at this stage was left-sided periorbital cellulitis secondary to ipsilateral sinusitis.

The patient was subsequently managed by a multidisciplinary team consisting of ophthalmologists, paediatricians and otolaryngologists. He was admitted, and treated with a course of intravenous antibiotics (cefuroxime and metronidazole) plus topical nasal decongestant.

An unenhanced computed tomography (CT) head scan revealed left pansinusitis associated with periorbital cellulitis.

However, following his admission the patient failed to improve; he remained pyrexial despite aggressive medical treatment (as described above).

Due to concerns regarding the ophthalmological risks of his condition, the patient underwent endoscopic orbital decompression and sinus surgery (i.e. left uncinectomy, maxillary antrostomy, and anterior and posterior ethmoidectomy), two days after his second presentation (i.e. four days after his initial presentation). At surgery, a large amount of pus was obtained, which was sent for microbiological culture; there was no growth of any pathological organism.

Following surgery, the patient continued to have difficulty opening his left eye, which remained grossly swollen. On day seven of intravenous antibiotics, five days post-operatively, he started to develop blurring of his vision, despite being apyrexial. Ophthalmological assessment confirmed increasing left orbital pain and a decline in left eye function. There was evidence of reduced visual acuity (5 in the right eye and 18–24/blurry in the left eye). The left pupil was unable to be visualised, to assess for size or light reflex, due to the grossly swollen state of the eye.

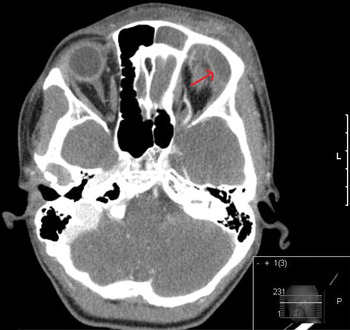

Subsequently, the patient underwent a contrast-enhanced CT scan of his orbits, which clearly demonstrated periorbital cellulitis and an abscess involving the left lacrimal gland, together with anterior ethmoidal sinusitis. There was significant inferior displacement of the globe, with an opacified left frontal sinus (Figures 1 and 2).

Fig. 1 Axial, contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showing a ring-enhancing lesion (arrow) in the region of the left lacrimal gland. L = left; P = posterior

Fig. 2 Coronal, contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showing swelling of the left orbit and soft tissue, with inferior displacement of the globe. The arrow indicates the lacrimal gland abscess. L = left

The patient again underwent surgery, involving stab incision of the lacrimal gland abscess, which resulted in drainage of large amounts of pus, together with a frontal trephine and frontal sinus wash-out.

Postoperatively, he received a further, 10-day course of intravenous, broad-spectrum antibiotics, comprising cefuroxime and metronidazole, to ensure Gram-negative and anaerobe coverage. Again, culture of pus specimens failed to produce any significant microbial growth, presumably due to the prolonged course of antibiotic treatment the patient had already received.

The patient consequently improved, and was discharged home four days post-operatively.

Subsequently, the patient progressed well clinically. At eight weeks' follow up, there was slight residual eyelid swelling. At a further follow-up clinic appointment, six months post-operatively, his eye signs had completely resolved and there were no residual visual problems.

At the time of writing, the patient was very happy with the outcome of his surgery, and had been discharged from our care.

Discussion

Periorbital cellulitis is common, particularly in the context of sinusitis. It occurs secondary to acute sinusitis in more than 90 per cent of paediatric cases and approximately 50 per cent of adult cases.Reference Ferguson and McNab5 The infection can spread either directly, across the lamina papyracea, or haematogenously. It is usually due to Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae or Moraxella catarrhalis, although anaerobic bacteria are also often involved in patients with chronic sinusitis. Rarely, the cause may be a fungus, such as mucor or aspergillus, and this should be considered in immunocompromised patients.Reference Sridhara, Paragache, Panda and Chakrabarti6

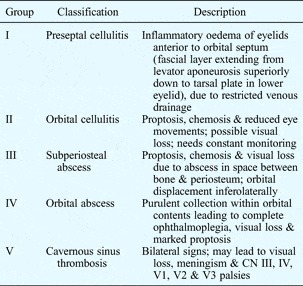

The classification of periorbital swelling due to sinusitis is vital, in order to guide effective management. Two classification systems have been described, the first by Hubert in 1937, based on anatomical position,Reference Hubert7 and the second by Smith and Spencer,Reference Smith and Spencer8 later modified by Chandler et al. Reference Chandler, Langenbrunner and Stevens2 in 1970 (Table I).

Table I Chandler's classification of orbital swelling

CN = cranial nerve

Further modifications of Chandler's classification system have been described.Reference Blake, Siegert and Gbara9 Schramm et al. identified a group of patients with preseptal cellulitis and chemosis who did not tend to improve with antibiotics, and for whom surgery was recommended.Reference Schramm, Myers and Kennerdell10 MoloneyReference Moloney, Badham and McRae11 simplified Chandler's classification somewhat by dividing the orbital complications into preseptal and postseptal complications, which include proptosis, restricted gaze, decreased visual acuity, defective colour vision and afferent pupillary defect.

The management of patients with periorbital cellulitis requires hospital admission and treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics that have intracerebral penetration and anaerobic coverage, together with nasal decongestant treatments. Most patients respond to such medical therapy. However, a small proportion of cases are complicated by the formation of an abscess, and require surgical drainage. Such cases require urgent treatment, due to the sight- and life-threatening nature of the condition. Periorbital cellulitis can be complicated by serious sequelae, including: visual loss from ischaemic retinopathy and optic neuropathyReference Bhargava, Sankhla, Gaensan and Chand12 (due to increased intraorbital pressure); restricted ocular movements; and spread of infection locally and centrally leading to cavernous sinus thrombosis,Reference Capps, Kinsella, Gupta, Bhatki and Opatowsky13 meningitisReference Eustis, Mafee, Walton and Mondonca14 and cerebral abscess.Reference Herrmann and Forsen15

Periorbital cellulitis complicated by lacrimal gland abscess is rare, with only six cases reported in the literature, of which only two were paediatric cases.Reference Patel, Khalil, Amirfeyz and Kaddour3, Reference Guss and Kazahaya4, Reference McNab16–Reference Mirza, Lobo, Counter and Farrington18 In our case, the diagnosis was confirmed on contrast-enhanced CT, after the patient had ongoing, marked periorbital swelling and pain which failed to respond to antibiotics. As we experienced in this case, an abscess can be easily overlooked on an unenhanced CT scan, and this radiological investigation should always be performed with contrast for this reason. Subsequent surgical interventions were successful in improving our patient's symptoms, and led to complete resolution.

• Periorbital cellulitis is a common paediatric condition

• Rarely, it is complicated by lacrimal gland abscess

• If a patient fails to respond to medical management, early surgery is required to avoid complications

• Failure of clinical improvement following orbital decompression may be due to an associated lacrimal gland abscess

• Contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows the abscess as a ring-enhancing peripheral lesion

This case highlights the need to carefully follow clinical changes in the patient's signs and symptoms, and, if initial management fails, to repeat imaging and to consider prompt surgical exploration. Furthermore, the case emphasises the importance of efficient management using a multidisciplinary team approach.

Conclusion

Periorbital cellulitis is a common paediatric condition, which in rare instances can be complicated by a lacrimal gland abscess. The presented case shows that if the initial diagnosis fails to respond to medical management, it is important to consider early surgical management to avoid complications. Furthermore, failure of clinical improvement following orbital decompression should alert the clinician to the rare possibility of an associated lacrimal gland abscess. In the presented patient, initial imaging of the orbits, without contrast, failed to adequately display a collection or abscess; however, the crucial second, contrast-enhanced scan revealed the abscess as a ring-enhancing peripheral lesion, thus highlighting the importance of contrast-enhanced CT scanning in this clinical scenario.