Songs were the foundation of Amy Beach’s musical world. Her mother reported that by the age of one, she could hum forty songs. By age two, she could sing harmony to any tune her mother sang. She insisted that her mother and maternal grandmother sing daily – but only songs she liked. Harmonizing with her mother’s singing was a bedtime ritual. This love of singing led to mental composition of melodies, later harmonized during her first experiences playing the piano. It was natural that she felt all music-making was “singing,” be it vocal or instrumental. Appropriately, her first publication was a song, and songwriting led to her initial fame as a composer. For decades after her death, she was best remembered for her songs. They are well crafted, most with singable melodies and integrated piano accompaniments, satisfying to both musicians and audiences.

Songs predominate her total compositional output. She composed them prolifically, even during the years she was occupied primarily with writing larger compositions. Between 1887 and 1915, several songs were published each year, almost all shortly after their composition. Performances by some of the United States’ most prominent musicians furthered the songs’ remarkable popularity and contributed to their quickly becoming standard concert, recital, and teaching repertoire. She and her primary publisher, Arthur P. Schmidt, worked diligently to promote the songs and ensure they stayed in print. Despite their popularity during her lifetime, they fell into neglect when ill health precluded her extensive travels and performances around the United States to promote them.

In the 1970s, despite a resurgence of interest in women composers, only two of her songs were available in print.1 Renewed interest in her oeuvre focused primarily on her importance as the first successful American woman composer to create large-scale orchestral, choral, and piano works, leading to a revival of performances of her major works. Largely because it was not unusual for women of her day to compose in smaller forms, her songs remained in obscurity a bit longer. Only after several were reprinted in the mid-1980s did they begin to reclaim their well-deserved attention. As of this writing, almost all of her published songs in the public domain are available through www.imslp.org, and many songs have been republished in scholarly editions. Numerous autographs used by publishers to prepare printed editions are housed in the Library of Congress’s A. P. Schmidt Collection (www.loc.gov/collections/a-p-schmidt-collection/).

Stylistic Characteristics

From 1880 to 1941, Beach composed 121 art songs with keyboard accompaniment, of which 111 were published during her lifetime. They demonstrate her exceptionally insightful understanding of texts, mastery of the form, and awareness of trends in current European musical styles. The assumption that Beach’s songs are overly Romantic in nature, unnecessarily elaborate, and excessively sentimental has sometimes led to their cursory dismissal as being mere parlor songs. While those descriptions might be appropriate for many songs by her female contemporaries, Beach’s songs were composed as art songs. Even though the vocal lines and accompaniments of some of her songs are complex and technically demanding, they were intended to be sung and played by both amateur and professional musicians.

She believed that the mission of all art is to uplift: “to try to bring even a little of the eternal into the temporal life.”2 She strove for musical expression people would understand, believing that songs should be inspired, creative, musical responses to texts – incorporation of both intellect and emotion.

Even though some critics have accused her of imitating other composers, or of composing in the style to which she had been most recently exposed, very few songs bear resemblances to those of her peers, a fact recognized early in her career. In a 1904 article on Beach’s songs, critic Berenice Thompson wrote,

She is not a poet dreamer, nor are her instincts those of the morbid or fastidious impressionist. Her artistic personality is entirely distinct from the schools of the day. She is neither a disciple of Richard Strauss, nor an exponent of the peculiar theories of d’Indy, Debussy, and the other Frenchmen. Nor are her ideas affiliated with the decadence which programmatic music and the mixture of arts is bringing upon the music of the century.3

Any similarities between her songs and those of other composers are more a reflection of her manifold interests and experiences than of plagiarism. Several poem settings actually predate those of her contemporaries.

Other critics have implied that her songs are all more or less alike. Closer examination reveals that, while many songs share similarities in structure, sentiment, and methods of text setting, all are quite distinctive. A hallmark of her music is extensive use of chromaticism, rooted in the ideals of German Romanticism. The application of this chromaticism was increasingly implemented within the context of more modern musical idioms, including impressionism and quasi-atonalism.

Song composition played a major role in the development of her unique musical language, providing her with opportunities for small-scale experimentation incorporating a wide variety of musical influences. Their use within this small form was subtle and controlled in comparison with more obvious inclusion of increasingly modern musical influences in her larger works. Several quotations from her writings will provide a basis for understanding her goals in song composition.

“Music should be the poem translated into tone, with due care for every emotional detail.”4

From earliest childhood, poetry was the foundation of Beach’s songs. Well before she could read or write music, children’s poems inspired spontaneous creation of accompanied songs. Memorizing texts came easily, as by age four, she was able to recite many long, difficult poems. This remarkable memory served her in good stead later in her method of songwriting: “In vocal music, the initial impulse grows out of the poem to be set; it is the poem which gives the song its shape, its mood, its rhythm, its very being. Sacred music requires an even deeper emotional impulse.”5

“I believe that a composer, like anyone else, is influenced by what he studies and reads, because literature cannot fail to react upon artistic expression in any other form.”6

Avid reading and continuing social contact with some of the United States’ most esteemed writers refined her literary discernment. An eclectic taste in poetry is apparent in the wide range of authors whose texts she set. Her husband may have suggested settings of poems by historically significant authors, including Shakespeare and Burns, but the majority of the songs were settings of works by living authors, many of whom were friends. More than one-third of the texts were by female writers.

French and German poetry from anthologies, newspapers, and popular magazines inspired eleven German and seven French songs. These texts provided a means for experimentation with inclusion of elements of current trends in the styles of German Lied and French chanson, as well as an opportunity to hone her skills in text settings in those languages.

Much poetry of her early songs appealed to Victorian ideals and may seem dated today. She was drawn to poems about love and nature. Love song texts in the first person were most commonly from a female perspective. Other favorite topics were times of day (most frequently twilight or night), flowers, and birds. Several songs quote or are based on birdcalls, including “The Blackbird,” op. 11, no. 3 (1889); “The Thrush,” op. 14, no. 4 (1890); and “Meadowlarks,” op. 78, no. 1 (1917).

“In vocal writing, the initial impulse grows out of the poem to be set; it is the poem which gives the song its shape, its mood, its rhythm, its very being.”7

Beach fervently believed that in order to interpret a song effectively, a singer must fully understand a poem’s meaning and character. To this end, she preferred that a song’s text be printed on the page before the musical score, as she shared with her publisher in a 1908 letter: “A singer can get at a glance a better idea of the character of a song by this means than by a prolonged study of words scattered thro’ [sic] several pages of music.”8 She expanded on her views of the importance of the text to interpretation in a 1916 article:

Each song is a complete drama, be it ever so small or light in character, and no two are interpreted in the same way. Even the quality of the voice may change absolutely in order to bring out some salient characteristic of the composition. Technical perfection may indeed be there, but so completely subordinated to the emotional character of the song that we lose all consciousness of its existence.9

“A composer must give himself time to live with what he is creating.”10 “It may happen that, for instance, that one has a ‘perfect’ theme for a song. … It is quite possible that the melodic line may not seem at all suitable for the voice … the original theme may develop into something quite different from the song that was first planned.”11

Songwriting was recreation for Beach. When she felt a roadblock while working on a larger piece, she sometimes wrote a song, viewing it as a special treat: “It has happened to me more than once that a composition comes to me, ready-made as it were, between the demands of other work.”12 Her songs may have seemed to flow quickly and spontaneously from her pen, yet they often evolved unconsciously over a longer period of time, although this was not always the case.

“In writing a song, the composer considers the voice as an instrument, and that the song shall be singable should be the fundamental principle underlying its creation. Many an otherwise magnificent work lies on the shelf, unused, because it is not suitable for the voice.”13

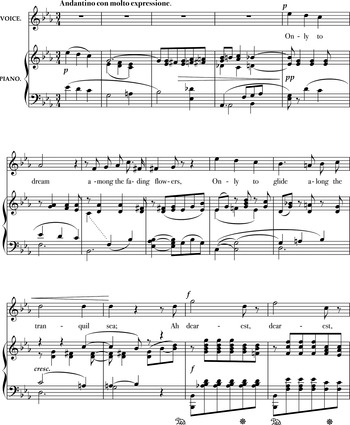

What makes most of Beach’s songs so singable? Why do they practically sing themselves? The answer is most likely her remarkable sensitivity to languages’ natural inflections, even though this may not be consciously perceived by the musician or listener. Her songwriting process began by careful contemplation of the poem to be set. After memorization, mental repetition of the words’ spoken inflection led to the melody, phrase by phrase. The result: melodies that are musical representations of the text’s natural inflections, as if the pitches of the spoken word were given musical notes (Example 6.1). Division of poetic lines into two- or three-measure phrases enhances the songs’ singability as well.

Example 6.1 “Ecstasy,” op. 19, no. 2, mm. 1–14.

It is worthwhile to consider the voice types Beach had in mind for each song. This can frequently be determined by a song’s dedication. Most early songs were composed for light, high, female voices. Later in life, she favored large, dramatic female voices.

About 60 percent of the songs, most of which were for high voice, were published in only one key (much to the chagrin of those with lower voices). Because her musical response to poetry emerged in specific tonalities, with their associated timbres in both piano and vocal parts, it is preferable to sing them in their original keys. Even so, modern performers and audiences are not able to experience the exact, original, intended sonorities of the early songs, as pianos in Boston were tuned slightly lower in the late nineteenth century than they are today.

Most of her songs are in major keys, with F major, A-flat major, and E-flat major predominating. She perceived the latter two of these as blue and pink, respectively. Three lullabies composed for friends’ newborn babies made use of these color associations, with blue for male and pink for female. Curiously, given her childhood aversion to music in minor keys, thirty-three of her songs represent ten different minor modes. With very few exceptions, songs in minor modes end with (sometimes quite abrupt) major cadences.

She was highly opposed to unauthorized transpositions of her songs, as her timbral intent would be obliterated. In order to fulfill and/or increase their demand, Schmidt requested transpositions of several songs (beginning with “Ecstasy” in 1893). Alternate keys were usually lowered by a minor third. Popularity of “Ah, Love, but a Day!” and “Shena Van” warranted three transpositions. Songs with expansive ranges and high tessiture not lending themselves to acceptable transpositions were published in one key, with alternate pitches for highest and/or lowest notes.

“A composer who has something to say must say it in a fashion that people will listen to, or his works will lie in obscurity on dusty shelves.”14

Beach understood the publishing industry was purely a business matter, regulated by supply and demand. As her compositional career blossomed, she and Schmidt employed a variety of strategies to create broader demand for her music. Marketing efforts focused on songs and short piano pieces, music that would please the amateur musician and be performed frequently because of its accessibility. To appeal to this demographic, songs in foreign languages were published with English titles and singing translations printed above the original language, a common practice at the time.

Schmidt published notices and advertisements in newspapers and magazines. He also distributed his own promotional pamphlets containing effusive (sometimes misrepresentative) descriptions of Beach’s songwriting prowess. He took advantage of publicity garnered by performances of her larger works by coordinating publication of her newest songs with those events. Their inclusion on subsequent high-profile concerts furthered sales. To satisfy and increase demand, arrangements of her biggest sellers were published with violin obbligati and for various combinations of voices.15 “A Song of Liberty,” op. 49, and “The Year’s at the Spring,” op. 44, no. 1, were issued in Braille (in 1922 and 1931, respectively).

Magazines offered another effective means for promoting songs. Several were composed expressly for them, usually published with an accompanying biography and/or interview. These songs are short, with simple melodies within limited ranges and easy accompaniments.

When programming Beach’s songs, one should be aware that most of her early songs were composed as individual entities, with highly varying topics, usually unrelated. As soon as she had produced three to five songs, Schmidt published them in an opus, deciding on the order of the songs within the opus.

In 1891, after publishing eighteen of her songs, Schmidt assembled fourteen, issuing them as part of a series of song anthologies. All were subtitled “a Cyclus of Songs,” even though none of them contained song cycles. Schmidt likely hoped these publications would increase profits, as customers wanting to purchase one or two songs might be likely to pay a little more to buy a collection that included songs that had not sold well singly. After publishing another thirty-nine songs, a second anthology of fourteen songs (also part of the “Cyclus” series) was issued in 1906. Plans for a third anthology in the 1930s never came to fruition due to high costs of printing during the Depression.

It is often misconstrued that since several of Beach’s better-known songs are slow, they all share that trait. Actually, an equal number of fast and slow tempi are represented in her song output. All tempo designations are in Italian, most with added directives for their interpretation, commonly including the adverbs espressivo or espressione; tranquillo or tranquillamente.

Early songs exhibit somewhat of a formula for setting up a melody’s climactic note, usually at or near a piece’s end: an ascending vocal line leading to the highest tone is interrupted by descending movement, either stepwise or a skip, that precedes an ascending leap of at least a minor third to the high note. A song’s highest (and either loudest or softest) tone is usually set on an open vowel ([a] or [ɔ], for example), sustained for one or two measures. She certainly sensed that these open vowels are the most conducive for optimum vocal resonance in singers’ higher ranges. Frequently, though, the tone preceding the highest one is also on an open vowel. As these ascending intervals straddle singers’ upper passaggi, it is more challenging to maintain forward placement than if the high note were preceded by a closed vowel (such as [e] or [i]). These highest tones and their accompanying chords were usually assigned sudden, extreme dynamic changes, sometimes pianissimo, but more often a jolting forte or fortissimo. Musicians should consider that these sustained tones were intended to have as much “life” as the preceding material, not beginning and maintaining the same dynamic from outset to completion. For effective interpretation, to give the music shape and carry expressive movement forward, pianissimo notes should begin as a slightly louder dynamic level than specified, making a decrescendo to the level indicated. As it can be strenuous for the singer to sing and sustain a loud tone “going nowhere” expressively for several measures, as well as unsettling to the listener to be bombarded by such an abrupt, loud dynamic change, the loudest notes should begin more softly than designated, making a crescendo to the indicated fortissimo.

Facility at the piano likely contributed to her technically challenging accompaniments. Continual use of octaves and complex chords with quite differing distributions of notes in quick succession requires long fingers and comfortable hand spans of more than an octave. Accompaniments rarely double vocal melodies. Occasionally during measures of rest between vocal phrases in earlier songs, what promises to be an effective countermelody emerges, only to disappear at the voice’s reentrance. Her preference for triple and compound meters (especially 6/8) facilitated the incorporation of repeated eighth note or triplet chords/figures to increase intensity and forward motion, a device also found in her solo piano works (Example 6.2). While used to great effect in several songs, its implementation for measures (or pages) at a time resulted in their monotonous similarities.16 Endings of three chords or with ascending arpeggiated flourishes (often in sixths) became somewhat cliché (Example 6.3).

Example 6.2 “After,” op. 68, mm. 71–78.

Example 6.3 “Forget-me-not,” op. 35, no. 4, mm. 55–59.

Clearcut variations in Beach’s songs delineate three distinct compositional style periods. These correspond with three important periods of her life. The first style period begins with her first published work in 1883, “The Rainy Day” (composed 1880), and ends with the deaths of her husband and mother in 1910 and 1911, respectively. Songs composed in 1914 in Europe comprise a second style period. A third style period begins in 1916 and continues through 1941.

First Style Period (1883–1911)

As a girl, and later as the wife of a socially connected, wealthy Boston surgeon, Beach had extensive time to devote to piano practice and composing, making this her most productive period of song composition. She composed seventy-two songs during these thirty years, many of which became her best known. Notably, “The Rainy Day,” her first published song, begins with a direct quotation of the first eight notes of the third movement of Beethoven’s “Pathétique” Sonata, op. 13, transposed from C minor to F minor.

After marrying in 1885, her program of autodidactic musical study was supplemented inestimably by her husband’s careful guidance. An amateur singer and accomplished pianist, Dr. Beach had extensive knowledge and appreciation of art song literature. He shared his expertise with Amy, introducing her to masterworks of song. This deepened her understanding of basic structural elements, including forms, text settings, sensitively crafted accompaniments, modulations, shaping of phrases, and appropriate ranges and tessiture.

Dr. Beach was also an amateur poet. Amy set seven of his poems, all composed within his lifetime and dedicated “To H,” with authorship attributed to H. H. A. B. The first of these settings were the three op. 2 songs. They were certainly composed for him, as relatively low and limited ranges would have suited his baritone voice. She composed settings of his poems on his birthday (December 18), presumably as birthday presents. Manuscripts dated December 25 suggest that, after being given poems for Christmas, she made settings immediately.

It should be taken into account that late nineteenth-century pianos were usually tuned slightly lower than modern ones. The prevailing pitch standard in Boston from at least 1863 to 1900 was A = 435.17 A = 440 was not officially adopted as the universal pitch standard until the International Standardizing Organization (ISO) meeting in London in May 1939.18 As a result, many songs composed for medium voice may be deceptively difficult for today’s amateur singers, as their highest notes fall slightly in voices’ upper passaggi.

From the outset, strophic, modified strophic, and ternary forms predominated Amy Beach’s song output. All but a handful follow this uniform pattern: minimally varied melodic material for repetitions of A sections are supported by accompaniments’ substantially different harmonies. Most early songs are marked by expansive, flowing melodies and accompaniments that reflect the influence of contemporary European compositional styles.

Interspersed are several songs described as enjoyable, “if not fully apprehended at first hearing.”19 This type of song begins with four to eight measures of a memorable melody that subsequently evolves into a seemingly jagged chain of notes. This is caused by vocal parts’ frequent extraction from (or burial within) their accompaniments’ relentlessly changing harmonies. The voice sometimes provides counterpoint for the accompaniment or serves as an inner part to complete a complex chord. Rapidly changing harmonies rarely lead to predictable vocal entrances after measures of rests.20 Several songs’ introductions contain descriptive figures that are repeated between vocal phrases, yet the vocal lines that follow are disjunct and bear no correlation with an accompaniment’s motive. Her usual sensitivity to natural speech inflection is absent in these songs.21 These rambling, pianistic songs that lack perceptible melodies show no apparent compositional models. They bring into question her later statement that she always composed away from the piano.22

Vacillation between (often remote) tonalities necessitated the persistent use of accidentals (including frequent double sharps/flats) and enharmonic spellings (alternating between correct and incorrect spellings), making them difficult for an accompanist to read. Critic Rupert Hughes even described one of her more accessible songs as “bizarre.”23

Prominent nineteenth-century American and European song composers generally employed evident melodies and sparse accompaniments with slow harmonic movement within conventional chord progressions. She hit her stride around 1894, composing increasingly marketable songs containing the streamlined accompaniments and flowing melodies for which she is best known.

The 1890s were her most productive years of songwriting, with publication of thirty-seven songs during the decade. Her first big seller was a modified strophic setting of her own two-verse poem, “Ecstasy” (1893). Its moderate range and simple, memorable melody in two-measure phrases (helpful for amateurs with limited breath control) made it appealing to the average musician. Its popularity prompted the first publication in an alternate key. The poem was included in The Poetry Digest: Annual Anthology of Verse for 1939 (New York: The Poetry Digest, 1939). As most of the subsequent songs of this period are in this accessible style, the success of “Ecstasy” may have given her better insight into the type of song that might please the general public.

In his 1893 Harper’s Magazine article, Antonín Dvořák proposed that in order to create a truly American art form, composers should incorporate “plantation melodies” and minstrel show music. The article prompted Beach’s immediate Boston Herald rebuttal: the opposing idea that American composers should look to their own heritages for inspiration.24 There is no evidence that they met personally during his 1892–95 stay in the United States, but she was clearly aware of his views and had thought deeply about them. Whether coincidental or not, it was around this time that Beach began inclusion of musical ideas reminiscent of traditional folk music of the British Isles, as evidenced by the stark contrast between her op. 12 (1887) and op. 43 (1899) settings of Robert Burns’ poems. The 1887 songs number among the long, rambling, piano-heavy songs of her youth. In stark contrast, with inclusion of dotted rhythms and “Scotch snaps,” the 1899 settings could be mistaken for folk songs. These songs appealed to the market: strophic with short, easily remembered melodies and simple accompaniments. The most popular of these, “Far Awa’!,” was later published in six arrangements for various groupings of singers and instruments between 1918 and 1936.

Following the 1899 Burns songs’ success, Beach employed the same formula for the highly successful “Shena Van,” op. 56, no. 4 (1904), a setting of William Black’s poem from his 1883 romance novel, Yolande. The melody’s pentatonic melisma contributes to the song’s folklike qualities, while a simple chordal accompaniment mimics a bagpipe with an open fifth drone. Similarities with Edvard Grieg’s “Solveig’s Song” suggest it might have been the model for “Shena Van.”

Among the handful of Beach’s most popular and enduring songs are the Three Browning Songs, op. 44 (1900), composed and dedicated to the Browning Society of Boston. Their high tessiture and manner in which vocal lines approach climactic high notes contribute to these being the most vocally demanding of her songs. “The Year’s at the Spring” and “Ah, Love, but a Day!” are the best known and most frequently performed of the three. In 1932, “Ah, Love, but a Day!” was reportedly the popular choice in a nationwide survey of the most standard American songs.25

By far the most popular of her songs, “The Year’s at the Spring,” was a staple of recital repertoire throughout the first half of the twentieth century. She later recalled: “It was composed while travelling by train between New York and Boston. I did nothing whatever in a conscious way. I simply sat still in the train, thinking of Browning’s poem and allowing it and the rhythm of the wheels to take possession of me.”26 She also recalled, “I had no writing materials with me, and so I went over and over it in my mind – learned my own composition by heart, so to speak, and as soon as I got to New York, wrote it down in twenty minutes. That, practically unchanged, was the song I gave them.”27

Robert Browning’s son was intensely moved upon hearing it, saying it could hardly be called a “setting:” the music and words seemed to form one entity; that one could not imagine anything more perfectly “married” than her music to his father’s words.28 Audiences’ enthusiastic responses to it (and a length of less than a minute) often prompted singers to repeat it several times. Interestingly, it holds the distinction of being the first song transmitted over the telephone.29

Although published as no. 1 of op. 44, “The Year’s at the Spring” is most effective at the end of the group when all three songs are performed together as a set. Its exuberance and animated tempo create a dramatic contrast with the two other songs’ slower tempi, bringing the set to a jubilant end. This reordering (2, 3, 1) also preserves the intended harmonic progression.

Only in her first style period did Beach set French texts, with varying degrees of success. Of these seven, “Jeune fille et jeune fleur,” op. 1, no. 3, and “Chanson d’amour,” op. 21, no. 2, are more varied versions of the rambling, fast harmonic rhythm songs, as they contain occasional measures with slower harmonic rhythms supporting “melodies.” These melodies appear as opening statements of verses or as short refrains. The four most appealing French songs show influences of the café chantant style of Charles Gounod and Eva dell’Acqua: “Le Secret,” op. 14, no. 2 (1891); “Elle et moi,” op. 21, no. 3 (1893); “Canzonetta,” op. 48, no. 4 (1902); and “Je demande á l’Oiseau,” op. 51, no. 4 (1903). Melodies reflecting the texts’ inflection are absent in these songs, perhaps a result of her unfamiliarity with the language.

In contrast, the melodies of her eleven German songs are excellent examples of melodies mirroring their texts’ spoken inflections. Both lighthearted songs and those with long, flowing melodies are among their number. They show her awareness of the most recent German song compositions, especially those of Hugo Wolf and Richard Strauss. Her admiration for Strauss’ song “Ständchen” inspired her to compose a piano transcription in 1902. Around the same time, she produced the masterpiece, “Juni,” op. 51, no. 3. Given her recent preoccupation with Strauss’ song, one might expect to find similarities between their melodies (Examples 6.4 and 6.5).

Example 6.4 Richard Strauss, “Ständchen,” op. 17, no. 2, mm. 10–12.

Example 6.5 Beach, “Juni,” op. 51, no. 3, mm. 7–8.

The text’s sole topic of blooming spring flowers is perfectly expressed through the melding of melody and accompaniment, which become increasingly effusive throughout the piece, ending with a burst of joy. Overutilized in some songs to the extent of being a trademark, implementation of repeated triplets in “Juni” is the precise element needed to heighten the song’s intensity to its final chord.

Second Style Period (1914)

During most of her time in Europe from 1911 to 1914, a busy travel and performance schedule precluded time for composition. This lull was broken in 1914, her most prolific year of song composition. The ten songs composed in Munich in May–June (opuses 72–73 and 75–76) comprise her second style period.

In September 1911, Beach sailed to Europe intending to establish a reputation abroad as a performer, thus promoting the sale of her works there. Her traveling companion, dramatic soprano Marcella Craft (1874–1959), was beginning the third year of her five-year contract with Munich’s Bavarian Opera. Beach and Craft’s friendship began in 1898 while Craft was a voice student at the New England Conservatory. Craft sang for Beach, who was immediately enamored with her voice. After moving to Europe in 1900, Craft sang in several Italian and German opera houses before being hired in Munich. She introduced Beach’s songs to European audiences as early as 1903. Richard Strauss, the director of the Bayrische Staatsoper, often chose her to sing roles under his direction, including the title role in his Salome. Because Craft was well established in Munich, Beach chose it as her “home base” abroad. In addition to her own ties there, Beach benefited from Craft’s musical and social connections with prominent public and musical figures in Europe.

As in the United States, programs of her larger instrumental works often included songs. Those large works received critical acclaim in Germany, but such was not always the case with her songs. Several critics expressed bewilderment about the songs’ sentimentality in comparison with the high caliber of her works for larger forces. The 1914 songs show that she may have taken this criticism to heart. German audiences were accustomed to hearing vocal works by her European contemporaries, including Johannes Brahms, Hugo Wolf, Richard Strauss, Gabriel Fauré, and Claude Debussy. Rather than striving to rival such masters’ work, she took another path. At last, she had freedom to develop her own musical aesthetic, unhindered by oversight, input, or advice from her husband and mother.30 She left the complex Richard Wagner-influenced harmonies behind, resulting in simpler songs with leaner, less complex accompaniments. The four in German show influences of German folk songs.

After an extended trip to Italy for rest and relaxation in 1914, Beach returned to Munich, where she completed ten songs during the month of June, all published by G. Schirmer. Until this point, A. P. Schmidt had been her exclusive publisher for almost thirty years. Her exasperation with Schmidt’s inability to keep European music stores stocked with her music led her to sign a contract with G. Schirmer the following month to publish future works.

In contrast with most earlier songs, these songs (and the majority composed afterward) served practical purposes. They were composed for singer friends, crafted to meet their needs for specific occasions and to display their greatest strengths. The 1914 songs were for performances at San Diego’s 1915–16 Panama–California Exposition and for future tours. The eight songs of opuses 72–73 and 75 have simple melodies in limited ranges and uncomplicated accompaniments and are accessible to musicians of all levels. However, due to Schirmer’s lack of large-scale marketing and restrictions in the publishing industry brought about by World War I, the delightful 1914 songs never received the widespread popularity of some of her earlier songs published by Schmidt.

The first of the 1914 songs, “Ein altes Gebet,” op. 72, no. 1, shows similarities with Wolf’s “Auf ein altes Bild,” suggesting that it served as model. Parallels include structure, text, title, and use of a two-measure ostinato that introduces a mixture of major and minor modes, a device Beach used with increasing frequency for the rest of her career. The text’s sentiment was clearly significant to her, as it returned in her choices of poems for two songs composed decades later: the necessity of faith in and total reliance on God’s saving care.

Two folklike songs (op. 73) were composed for contralto Ernestine Schumann-Heink to sing at the San Diego Exposition, where her performances drew crowds in the tens of thousands. Schumann-Heink was a mother of eight; Beach’s choice of German texts about familial topics complemented her public image of maternal devotion and domesticity.

A sense of playfulness and whimsy surfaces in the four op. 75 songs, commissioned by American mezzo-soprano Kitty Cheatham (1865–1946), known for her programs of folk music and children’s songs. She was an early proponent of the African American spiritual, introducing many to both American and European audiences. These songs’ medium, limited ranges, and straightforward accompaniments make them accessible to all musicians. These four short songs are perhaps Beach’s most charming, in particular “The Candy Lion” and “A Thanksgiving Fable.” Their unexpected punch lines always elicit giggles from the audience.

The final 1914 songs, “Separation” and “The Lotos Isles,” op. 76, deviate from the folklike style of the previous eight. “Separation,” composed for Marcella Craft, returned to the highly chromatic style of the less accessible early songs, with unpredictable vocal lines and thick accompaniments. Familiar repeated triplet chords make a final appearance, as after “Separation,” Beach moved forward musically, “separating” herself from this style of composition.

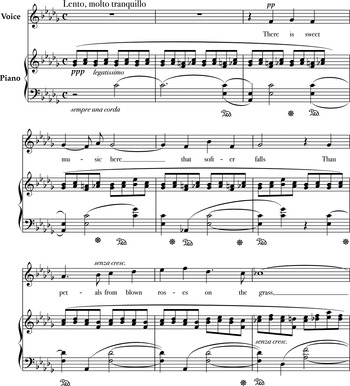

“The Lotos Isles” bears no resemblance to any earlier songs. Alfred Tennyson’s depiction of the drugged, floating, lethargic state induced by ingestion of lotos flowers provided a fitting musical canvas for her experimentation with impressionistic devices. She unified musical and poetic elements through a hypnotic melody, enveloped within a murmuring, dreamy accompaniment figure. A nebulous tonal center settles only at the end of the piece. Her inclusion of elements of the modern French style of Henri Duparc and Debussy marked a clear compositional pivot point (Example 6.6).

Example 6.6 “The Lotos Isles,” op. 76, no. 2, mm. 1–9.

Third Style Period (1916–1941)

Her pattern of (practically) nonstop travel for performances, talks, and other appearances (along with the occasional respite) begun in Europe showed no sign of subsiding after her 1914 return to the United States. If anything, her demanding schedule intensified in 1915, leaving her scant time to compose. Returning to songwriting in 1916, she picked up where she left off stylistically with “The Lotos Isles.” The definite break between the style for which she had become best known, and an increasingly more contemporary sound, defines a third style period (1916–41).31 Musical ideas in this period became more compact and accompaniments less flamboyant. Her songs maintained their characteristic chromaticism yet emerged increasingly from contemporary musical trends rather than from late Romantic roots. Such musical elements included vacillations between major and minor modes; use of modal and quasi-modal scales; nonfunctional, ambiguous harmonies and tonal centers; extensive use of major–minor sevenths, half, and fully diminished seventh chords, and jazz harmonies. Although not serial music, use of all twelve scale degrees as a source of dissonance (chromatic saturation) in the introduction to the song “Birth” (1929), as well as her use of a whole-tone scale in the opening measures of the melody of “A Message,” op. 93 (1922), demonstrates her openness to modernistic techniques. The majority of the thirty-two available songs from this period have memorable, singable melodies, underpinned by unexpected, chromatic harmonies reflecting the aforementioned elements. In more dissonant songs, ambiguous or restless tonal centers are clearly resolved in the final measures; usually ending with a cadence in a major mode. All are in English; all but two are settings of texts by contemporary authors.

For nineteen summers between 1921 and 1941, Beach composed (or made sketches for) almost all her compositions during summer months spent at the MacDowell Colony. Along with the Colony’s peaceful atmosphere, intellectually stimulating interaction with some of the United States’ most revered writers, artists, and composers precipitated a flood of creativity each year. New friendships with composers of the next generation led to reflection about modern trends in composition. Adrienne Fried Block notes that Beach’s initial experiments with dissonant, nontonal harmonies began the year of her first stay at the Colony.32

Rather than on songwriting, her compositional efforts at the Colony focused on choral, keyboard, and chamber works, as well as her opera, Cabildo, resulting in an output of only thirty-nine songs in twenty-five years, slightly more than half the number composed in the thirty years of the first style period. Most of the thirty-one published songs were issued individually with separate opus numbers, rather than in groups. Manuscripts for three unpublished songs – “Mignonette,” “My Love came through the Fields,” and “A Light that overflows” – were not assigned opus numbers, nor are there copyright records for them.33 The manuscript of “To One I Love,” op. 135 (1932), is in private hands.

Inclusion of songs on her many performances and programs for various organizations and musical clubs introduced them to a wide range of audiences in towns of all sizes throughout the United States. Older songs were paired with her most recent works on these programs, focusing on the latter. An increasing number of speaking and performing appearances in the 1930s, as well as live performances of her music on local and nationwide radio broadcasts, kept her in the public eye, prompting greater demand for her music. Sales of her newest works were thwarted by the outbreak of World War I, though, when paper and other shortages precluded their expeditious publication. These production difficulties persisted through the Depression, further exacerbated by World War II. After A. P. Schmidt’s death in 1921, his successor, Henry Austin, was often discouraging about possibilities of publishing her new songs, sometimes questioning their marketability. His excuses and reluctance to issue or reissue her songs contributed to her contracting with other publishers (including Schirmer, Church, and Presser). It is conceivable that Austin’s hesitancy to publish her most recent songs was due more to their inaccessibility to the average musician than to production problems. Despite his lack of interest in her most recent songs, he was eager to issue reprints of her most popular songs (all composed before 1905), also requesting they be arranged for various combinations of voices.

Until her death, Beach urged Austin persistently to publish her latest songs. As evidence of their merit, her letters frequently referenced successful performances of those in manuscript and their popularity with voice teachers. Always worded considerately, her letters reveal ever-increasing impatience. She was eager to have new songs copyrighted, lest they be plagiarized (a doubtful probability, given that those in question were of the “no perceptible melody” type).

Among the first pieces composed at the MacDowell Colony in 1921 was the dramatic song, “In the Twilight,” op. 85. Typical of many third style period songs, its accompanimental device is more impressionistic in character than in harmonic structure. In some ways, harmonies are reminiscent of the first style period songs: quick movement from an initial tonality to other tonal areas by use of dominant sevenths and fully diminished chords, with a melody evolving from those harmonies. The poem tells of a fisherman’s wife and child, watching a turbulent sea storm through a window at twilight, waiting for him to return from his day’s work. The wife fears for her husband’s fate. To enhance the text’s ominous feeling, Beach set the song in F-sharp minor, one of her “black” keys. As the natural inflection of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s masterfully chosen words create their own “text-painting,” the majority of the musical interpretation was achieved by manipulating the keyboard’s motif within the harmonic movement rather than through the vocal line. Expansion and contraction of this impressionistic pattern creates dramatic ebbs and flows, intensifying the text’s sense of urgency, anxiety, and impending doom.

The song’s ending is the most unusual in Beach’s vocal works, bearing a resemblance to the ending of Schubert’s “Erlkönig.” After building tension with tremolos for fourteen measures, a fermata precedes a German sixth chord, followed by an unaccompanied vocal line ending the song without the chord’s resolution to reflect the text’s final, unanswered question (Example 6.7).

Example 6.7 “In the Twilight,” op. 85, mm. 100–15.

“To me all music is sacred. … It is – and must be – a source of spiritual value. If it is not, it falls short of its function as music.”34

At the 1926 New York City convention of the American Pen Women, Beach became acquainted with dramatic soprano Ruth Shaffner (1896–1981), soprano soloist at St. Bartholomew’s Church (“St. Bart’s”), then the largest Episcopal church in North America. Schaffner invited Beach to attend a service there the next day to hear the composer’s Magnificat. Highly impressed by both the choirs and organist/choirmaster David McKay Williams’s musicianship, she began regular attendance there when in New York. Both Shaffner and Williams became two of Beach’s closest friends. Shaffner became Beach’s most frequent collaborator, performing together hundreds of times throughout the United States.

Involvement with St. Bart’s music program precipitated a flurry of sacred choral works and solo songs. Sacred music appealed to her more than anything she had previously done and became her favorite type of work. In a 1943 interview, she stated, “I find myself … turning more steadily toward so-called ‘sacred’ music. … It has not been a deliberate choice, but what has seemed a natural growth and a path which has brought me great happiness.”35 In a personal letter from a decade earlier, she had written, “There can be no greater experience than the act of entering into the great religious texts.”36

A fortuitous incident on July 4, 1927, led to another of Beach’s most significant relationships. Mezzo-soprano Lillian Buxbaum’s (1884–1974) performance on a Boston radio station prompted Beach to telephone her that afternoon, to invite her to visit Centerville the next day. Buxbaum’s acceptance led to a familial relationship between the two. Beach later regarded Buxbaum as a surrogate daughter. The two spent many summers together at Cape Cod and performed numerous concerts in New England. Like Shaffner, Buxbaum was a church soloist, serving at First Parish Church, Watertown, Massachusetts. Friendships with Shaffner and Buxbaum prompted composition of several pieces for their use in church services. Their needs and requests for sacred solos were met by Beach’s increasing inspiration to compose them. To fit the rich timbres in these women’s mid- to low ranges, some of these songs have lower tessiture than most earlier songs.

Unique among her songs is “On a Hill.” Returning to the United States after a six-month trip to Europe in 1929, a chance shipboard encounter presented Beach with new musical material when a fellow passenger from Richmond, Virginia, shared a song “crooned to her by an old Mammy all through childhood.”37 (It was assumed to be an African American spiritual, although this has not been authenticated.) Beach said she had never been so pleased by a folk song. She provided the song with a simple, chordal, bare-bones accompaniment, varied harmonically (as was her practice) for each of its three verses. This unobtrusive accompaniment allows the listeners’ ears to be drawn to the words and haunting, pentatonic melody. It was subtitled “Negro Lullaby” to set it apart from spirituals, which had recently inundated the market. Henry Austin of the Schmidt Company was discouraging about its sales potential, however, unless the prominent African American singer, Roland Hayes, would have interest in promoting it.38

Representative of Beach’s later sacred solos are “I Sought the Lord,” op. 142 (1937), and “Though I Take the Wings of Morning,” op. 152 (1941), both composed at the MacDowell Colony and dedicated to Ruth Shaffner. They express the same sentiment as her earlier song “Ein altes Gebet”: God’s omniscience and omnipresence. These texts might well have brought her comfort as she faced the realities of aging and adjusting to giving up her performing career.

Composed following her 1940 heart attack, “Though I Take the Wings of Morning” is a setting of Robert Nelson Spencer’s Psalm 139 paraphrase, taken from his The Seer’s House.39 The song shows influences of the African American spiritual, with chords vacillating between E minor and E major and use of alternating major and minor thirds in the melody. The accompaniment contains a rare example of vocal doubling. The final words of this, her final art song (and antepenultimate composition), are a poignant coincidence: “bid me then, be still.”

Which were Beach’s favorite songs? Those she frequently asked Austin to send to singers for specific performances provide clues. Almost all of the songs she requested after 1917 were composed early in her career. Several she repeatedly asked for had been long out of print. Songs selected for performances at retrospective concerts in honor of her seventy-fifth birthday in 1942 (all from the first style period) may indicate some favorites, those she felt were her most representative: “Ecstasy,” op. 19, no. 2; “Villanelle: Across the World,” op. 20; “My Star,” op. 26, no. 1; “The Wandering Knight,” op. 29, no. 2; “I send my heart up to Thee,” op. 44, no. 3; and “June [Juni],” op. 51, no. 3. Those most consistently found on concert programs and mentioned in her correspondence were “Ecstasy,” the Browning Songs, op. 44, and “Juni.”

Despite the popularity of her works during her lifetime, after she was no longer physically able to tour and concertize to promote them, regard for most of her compositions, particularly the larger ones, declined quickly. Even though her later songs show her efforts to include more contemporary musical elements, the majority of her most well-known songs (from the first style period) were in the late nineteenth-century idiom, then regarded as old-fashioned and of little musical value. The author of her Musical America obituary described her later songs as not particularly original, having lost some of the melodic interest of her earlier works; certainly not an accurate assessment.40 Restrictions in the publishing industry during World War II made reissuing out-of-print works difficult, leading to their quick neglect. By 1941, thirty-seven songs were unavailable. After Beach’s death, Shaffner made efforts to keep New York music stores stocked with songs that were still in print. This number had dwindled to two by 1984.41

“There is enjoyment in every contact with beautiful song – in writing, singing, playing, or even thinking of it – and it brings to the listener a sense of discovery of a world in which serenity and contentment still reign.”42

New generations of musicians and audiences are becoming familiar with Beach’s songs as copyright expirations have made possible their inclusion in anthologies and their availability on the internet. They make a welcome re-addition to the body of American art song repertoire, as among their number one finds something for everyone: musicians of all levels of ability as well as audiences of varying levels of sophistication.

A quotation from the final published interview of Beach’s life demonstrates her optimism in the face of the physical decline of old age and the tragedy of World War II. Fittingly, she expressed her optimism with the metaphor of singing:

We who sing have walked in glory.43 What more can we say about singing than that? And was there ever a time when singing was more badly needed than now? Singing, not only with our throats but with our spirits. If we have no special voices, we can make our fingers sing on the keyboard or strings. The main thing is to let our hearts sing, even through sorrow and anxiety. The world cries out for harmony.”44