INTRODUCTION

This study describes what we believe to be the core syndrome of agenesis of the corpus callosum (AgCC) as displayed in adults who have few, if any, other neurological abnormalities, and have grossly intact general intelligence. Although AgCC was previously thought to be exceedingly rare, increased clinical use of neuroimaging has resulted in higher detection rates in relatively normally functioning individuals. Studies conducted with this larger pool of patients are providing greater understanding of the role of the corpus callosum in cognition and behavior. The accumulating data also provides families and clinicians with more nuanced insights into the patterns of cognitive capacities that influence learning, daily behaviors, and developmental progression of individuals with AgCC.

AgCC is a congenital brain malformation defined by anatomy (complete or partial absence of the corpus callosum), and not defined by behavior abnormalities (as in autism). AgCC occurs due to disruption of neural development during the 7th to 20th embryonic weeks (Edwards, Sherr, Barkovich, & Richards, Reference Edwards, Sherr, Barkovich and Richards2014). The most recent evidence indicates that AgCC occurs in at least 1 in 4000 births, making it one of the more commonly occurring congenital brain disorders (Glass, Shaw, Ma, & Sherr, Reference Glass, Shaw, Ma and Sherr2008; Guillem, Fabre, Cans, Robert-Gnansia, & Jouk, Reference Guillem, Fabre, Cans, Robert-Gnansia and Jouk2003; Wang, Huang, & Yeh, Reference Wang, Huang and Yeh2004).

AgCC is often associated with a broader syndrome of brain malformation related to known toxic-metabolic conditions or genetic causes, but in 55–70% of AgCC cases the cause is unknown (Bedeschi et al., Reference Bedeschi, Bonaglia, Grasso, Pellegri, Garghentino, Battaglia and Borgatti2006; Schell-Apacik et al., Reference Schell-Apacik, Wagner, Bihler, Ertl-Wagner, Heinrich, Klopocki and von Voss2008; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Bartha, Norton, Barkovich, Sherr and Glenn2009). When part of broader neurodevelopmental syndromes or accompanied by other congenital brain malformations, the cognitive and behavioral impact of these other conditions would likely obscure the moderate to mild deficiencies directly related to callosal absence. To identify the specific contributions of the corpus callosum to higher cognitive abilities, this review describes the AgCC syndrome as it appears in individuals without any (or only very minor) other brain or body dysmorphology. These individuals typically have normal-range IQs and appear neurologically “asymptomatic” (i.e., lack of symptoms apparent in diagnostic procedures typically used in clinical neurology). In most of these individuals AgCC is discovered through routine prenatal sonogram or neuroimaging motivated by unrelated issues. In these cases, AgCC is likely to be the primary contributor to the cognitive outcome; thus, we refer to these individuals as having “Primary AgCC.”

Although they have a common primary neurological finding, individuals with Primary AgCC are somewhat heterogeneous with respect to other minor structural brain abnormalities, some of which appear to be secondary to the callosal dysgenesis (e.g., colpocephaly, Probst bundles) and some of which may or may not be related to the callosum (e.g., minor areas of heterotopia, interhemispheric cysts, interhemispheric lipoma). The group also varies with regard to amount of residual callosal connection (complete versus partial), and most likely varies at the molecular and synaptic level. To minimize the negative influence of concomitant neurological abnormalities, this review focuses on individuals with a full scale IQ above 80. Heterogeneity notwithstanding, we present what we believe to be the core syndrome that results in the mild to moderate cognitive and psychosocial deficits in Primary AgCC.

Finally, since the corpus callosum in neurotypical children is undergoing significant myelinization and functional development into the teenage years (Giedd et al., Reference Giedd, Castellanos, Casey, Kozuch, King, Hamburger and Rapoport1994; Yakovlev, Lecours, & Minkovski, Reference Yakovlev, Lecours and Minkovski1967), the neuropsychological and psychosocial outcomes of AgCC seem to “emerge” as their peers increase reliance on callosal connectivity. Thus, our commentary focuses on studies of older adolescents and adults.

CORE SYNDROME OF PRIMARY AgCC

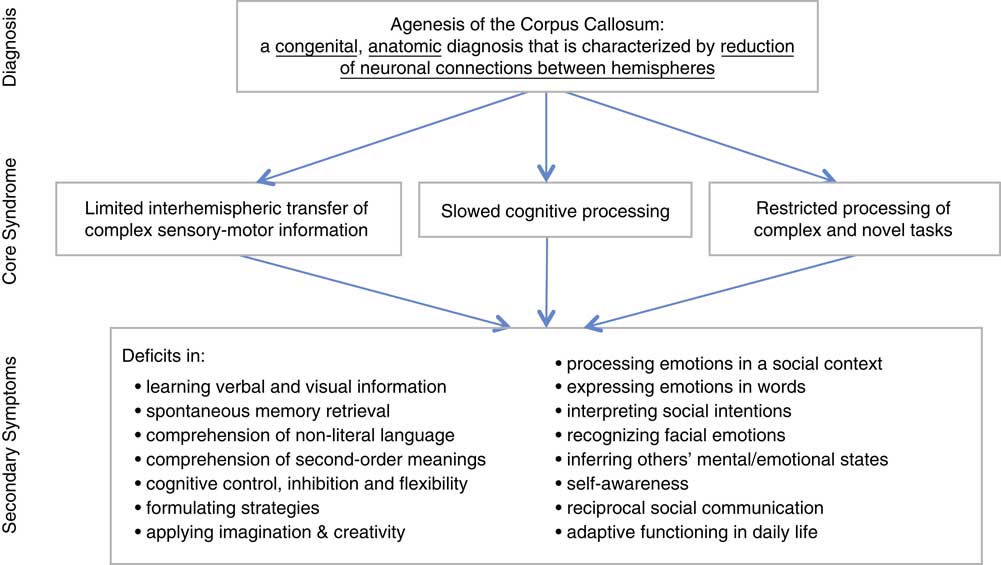

The aim of this study is to briefly sketch the core syndrome of Primary AgCC (i.e., deficits specifically related to callosal absence), which in turn contributes to more specific neuropsychological and psychosocial deficits in AgCC. The following sections will offer evidence from published literature (including much of our own research) demonstrating that Primary AgCC is associated with a core syndrome involving: (1) reduced interhemispheric transfer of sensory-motor information; (2) increased cognitive processing time; (3) deficient processing of complex information and unfamiliar tasks, and amplified vulnerability to increases in cognitive demands.

These three domains of dysfunction are not independent. Reduced interhemispheric interactions likely contribute to slower processing time and difficulty in complex problem-solving, which are themselves inter-related. These core deficits contribute to many other specific deficiencies we describe briefly (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1 Agenesis of the corpus callosum, core syndrome, and specific deficits.

DIMINISHED INTERHEMISPHERIC INTEGRATION OF SENSORY-MOTOR INFORMATION

The current understanding of callosal function came primarily from studying individuals who had a surgical commissurotomy, severing all of the cerebral commissures as a treatment for epilepsy. Commissurotomy and AgCC both involve a lack of callosal connections between hemispheres, but they are distinguished by (1) the presence of the other cerebral commissures in most cases of AgCC (e.g., anterior commissure is present in all cases of AgCC we describe), and (2) by the point in development at which the hemispheres are disconnected. Early investigations of interhemispheric transfer and integration of sensory and motor information in AgCC discovered that congenital absence of callosal connections does not cause a full “disconnection syndrome” as is seen following commissurotomy (Bogen & Frederiks, Reference Bogen and Frederiks1985; Sperry, Reference Sperry1968; Sperry, Gazzaniga, Bogen, Vinken, & Bruyn, Reference Sperry, Gazzaniga, Bogen, Vinken and Bruyn1969).

Unlike commissurotomy, limitations of interhemispheric transfer in AgCC are contingent upon the complexity of information being transferred. Numerous studies have shown that individuals with AgCC are capable of interhemispheric integration of easily encoded visual and tactile information (e.g., Brown, Jeeves, Dietrich, & Burnison, Reference Brown, Jeeves, Dietrich and Burnison1999; Chiarello, Reference Chiarello1980; Jeeves & Ettlinger, Reference Jeeves and Ettlinger1965; Lassonde, Sauerwein, Chicoine, & Geoffroy, Reference Lassonde, Sauerwein, Chicoine and Geoffroy1991; Saul & Sperry, Reference Saul and Sperry1968). However, diminished interhemispheric transfer in AgCC is evident in studies requiring transfer of more complex (and less familiar) information (e.g., Brown et al., Reference Brown, Jeeves, Dietrich and Burnison1999; Bryden & Zurif, Reference Bryden and Zurif1970; Buchanan, Waterhouse, & West, Reference Buchanan, Waterhouse and West1980; Geffen, Nilsson, Quinn, & Teng, Reference Geffen, Nilsson, Quinn and Teng1985; Jeeves, Reference Jeeves1979).

A study by Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Jeeves, Dietrich and Burnison1999) illustrated key differences in interhemispheric transfer of sensory information in individuals with AgCC and individuals with commissurotomy through the use of two tachistoscopic bilateral visual field matching tasks (letters and dot-patterns). As predicted by studies of the “disconnection syndrome,” the two commissurotomy patients in this study could not match bilateral presentations of either letters or dot-patterns above the level of chance. In contrast, participants with AgCC performed as well as neurotypical controls when matching two bilaterally and simultaneously flashed letters, with their limitations in interhemispheric transfer only becoming evident in impaired bilateral visual field matching of the less familiar and less easily encoded random dot patterns.

The mediating effect of encoding complexity on interhemispheric transfer in AgCC has also been demonstrated in studies of tactual-spatial information transfer using the Tactual Performance Test (Dunn, Paul, Schieffer, & Brown, Reference Dunn, Paul, Schieffer and Brown2000; Sauerwein & Lassonde, Reference Sauerwein and Lassonde1994; Sauerwein, Lassonde, Cardu, & Geoffroy, Reference Sauerwein, Lassonde, Cardu and Geoffroy1981), Finger Localization Test (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Paul, Schieffer and Brown2000; Geffen et al., Reference Geffen, Nilsson, Quinn and Teng1985; Sauerwein & Lassonde, Reference Sauerwein and Lassonde1994), and tactual recognition (Jeeves & Silver, Reference Jeeves and Silver1988). As with visual transfer, individuals with AgCC exhibited intact performance at the lowest levels of sensory-motor difficulty, with significant declines in performance occurring as tasks requiring transfer of more complex (less easily encoded) information.

Finally, limitations in interhemispheric transmission also interfere with fine motor coordination of the two hands in individuals with AgCC (Jeeves, Silver, & Jacobson, Reference Jeeves, Silver and Jacobson1988; Jeeves, Silver, & Milner, Reference Jeeves, Silver and Milner1988), as well as in individuals with surgical transection of either the anterior or posterior callosum (Eliassen, Baynes, & Gazzaniga, Reference Eliassen, Baynes and Gazzaniga2000; Preilowski, Reference Preilowski1972). Using the Bimanual Coordination Test (BCT), a test based on an Etch-a-Sketch toy (Brown, Reference Brown1991), we found that bimanual motor coordination was slower and less accurate in adults with AgCC than in neurotypical adults (Mueller, Marion, Paul, & Brown, Reference Mueller, Marion, Paul and Brown2009), but performance of adults with AgCC was similar to that of neurotypical children for whom the corpus callosum was not yet fully developed (Marion, Kilian, Naramor, & Brown, Reference Marion, Kilian, Naramor and Brown2003). Notably, even in neurotypical adults, poor structural integrity of motor connections via the corpus callosum becomes more strongly associated with poor bimanual coordination performance as task complexity increases (Gooijers et al., Reference Gooijers, Caeyenberghs, Sisti, Geurts, Heitger, Leemans and Swinnen2013).

REDUCED SPEED OF COGNITIVE PROCESSING

Speed is a fundamental feature of all cognitive processes. Consequently, slow processing speed may interfere with abilities in multiple domains. Processing speed is highly vulnerable to disruptions in white matter connectivity, particularly the CC (Kourtidou et al., Reference Kourtidou, McCauley, Bigler, Traipe, Wu, Chu and Wilde2013; Mathias et al., Reference Mathias, Bigler, Jones, Bowden, Barrett-Woodbridge, Brown and Taylor2004; Solmaz et al., Reference Solmaz, Tunc, Parker, Whyte, Hart, Rabinowitz and Verma2017; Ubukata et al., Reference Ubukata, Ueda, Sugihara, Yassin, Aso, Fukuyama and Murai2016). Studies described in the previous section offer clear evidence of slowed sensory and motor reaction times in individuals with AgCC. Slow processing speed is also evident in other cognitive tests. For example, in a sample of 32 adults with complete AgCC, we found that WAIS-III processing speed index scores were significantly lower on average than verbal, perceptual, and working memory indices (Erickson, Young, Paul, & Brown, Reference Erickson, Young, Paul and Brown2013).

Slow processing speed was also implicated in a study of cognitive inhibition in adults with AgCC. On the Color-Word subtest of the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System, we found deficient cognitive inhibition and flexibility in adults with AgCC compared to age- and IQ-matched controls, but regression analyses indicated that these differences in cognitive control were primarily the consequence of slowed processing speed (Marco et al., Reference Marco, Harrell, Brown, Hill, Jeremy, Kramer and Paul2012). Thus, processing speed limitations may have wide-ranging implications for cognition and behavior in AgCC. However, as found in studies of callosal damage in traumatic brain injury, impairments in processing speed are exacerbated on tasks with greater information processing demands (Mathias et al., Reference Mathias, Bigler, Jones, Bowden, Barrett-Woodbridge, Brown and Taylor2004).

DIFFICULTY WITH COMPLEX PROCESSING

Psychometric research in neurotypical adults has demonstrated that interhemispheric resources are recruited to assist with cognitively complex tasks (Koivisto, Reference Koivisto2000; Reuter-Lorenz, Stanczak, & Miller, Reference Reuter-Lorenz, Stanczak and Miller1999; Weissman & Banich, Reference Weissman and Banich2000) and simple tasks that are unfamiliar / unpracticed (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Jeeves, Milne and Ludwig1992). However, the benefit of interhemispheric processing decreases with practice (Cherbuin & Brinkman, Reference Cherbuin and Brinkman2005; Maertens & Pollmann, Reference Maertens and Pollmann2005; Weissman & Compton, Reference Weissman and Compton2003). In keeping with this finding, adults with Primary AgCC display amplified vulnerability to increases in cognitive demands, resulting in impaired reasoning, concept formation, and novel complex problem-solving, (i.e., deficits in fluid intelligence). By contrast, they do not have deficits in over-learned cognitive processes (i.e., crystallized intelligence), as supported by relatively normal (or even elevated) performance on most verbal and spatial portions of standardized intelligence scales (Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Young, Paul and Brown2013) and on tests of basic academic skills such as single-word reading, spelling, and math calculation (Young, Erickson, Paul, & Brown, Reference Young, Erickson, Paul and Brown2013).

Impairments in abstract reasoning (Brown & Paul, Reference Brown and Paul2000; David, Wacharasindhu, & Lishman, Reference David, Wacharasindhu and Lishman1993; Gott & Saul, Reference Gott and Saul1978), concept formation (Fischer, Ryan, & Dobyns, Reference Fischer, Ryan and Dobyns1992; Imamura, Yamadori, Shiga, Sahara, & Abiko, Reference Imamura, Yamadori, Shiga, Sahara and Abiko1994), problem-solving (Brown, Anderson, Symington, & Paul, Reference Brown, Anderson, Symington and Paul2012; Schieffer, Paul, & Brown, Reference Schieffer, Paul and Brown2000), and generalization (Solursh, Margulies, Ashem, & Stasiak, Reference Solursh, Margulies, Ashem and Stasiak1965) have all been observed in patients with AgCC. Such deficiencies are particularly evident as task complexity increases (Schieffer, Paul, & Brown, Reference Schieffer, Paul and Brown2000). For example, on the simplified (color) version of the Raven’s Progressive Matrices Tests (Raven, Reference Raven1960, Reference Raven1965) performance of adults with AgCC was consistent with individual Full-Scale IQ (FSIQ) scores, but performance was impaired relative to FSIQ on the more complex Standard Progressive Matrices (Schieffer, Paul, & Brown, Reference Schieffer, Paul and Brown2000). The benefits of practice in Primary AgCC are supported by patterns of academic achievement in a sample of adults who performed within average range on basic mathematic calculations (a skill practiced throughout school), but exhibited significant deficits on math reasoning (Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-II; Hanna, Reference Hanna2018).

ASSOCIATED COGNITIVE AND PSYCHOSOCIAL DEFICIENCIES

These three core cognitive deficiencies impact a wider range of cognitive and psychosocial functioning. Adults with AgCC have difficulties encoding verbal and visual information in memory and spontaneously retrieving newly learned information (Erickson, Paul, & Brown, Reference Erickson, Paul and Brown2014; Paul, Erickson, Hartman, & Brown, Reference Paul, Erickson, Hartman and Brown2016), adequately understanding non-literal and complex language (Brown, Paul, Symington, & Dietrich, Reference Brown, Paul, Symington and Dietrich2005; Brown, Symington, Van Lancker-Sidtis, Dietrich, & Paul, Reference Brown, Symington, VanLancker, Dietrich and Paul2005; Paul, Van Lancker-Sidtis, Schieffer, Dietrich, & Brown, Reference Paul, Van Lancker-Sidtis, Schieffer, Dietrich and Brown2003; Rehmel, Brown, & Paul, Reference Rehmel, Brown and Paul2016), exerting cognitive inhibition and flexibility (Marco et al., Reference Marco, Harrell, Brown, Hill, Jeremy, Kramer and Paul2012), formulating strategies (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Anderson, Symington and Paul2012), and effectively applying imagination and creativity (Paul, Schieffer, & Brown, Reference Paul, Schieffer and Brown2004; Young et al., in press).

In addition, these core cognitive deficits negatively impact social and emotional cognition, resulting in difficulty reasoning abstractly about emotions in social context (Anderson, Paul, & Brown, Reference Anderson, Paul and Brown2017; Paul et al., Reference Paul, Lautzenhiser, Brown, Hart, Neumann, Spezio and Adolphs2006); expressing emotions in words (Pazienza, Brown, & Paul, Reference Pazienza, Brown and Paul2011); interpreting sarcasm and understanding subtle aspects of social interactions (Symington, Paul, Symington, Ono, & Brown, Reference Symington, Paul, Symington, Ono and Brown2010); recognizing emotion in faces (Bridgman et al., Reference Bridgman, Brown, Spezio, Leonard, Adolphs and Paul2014); imagining and inferring the mental, emotional, and social functioning of others (Kang, Paul, Castelli, & Brown, Reference Kang, Paul, Castelli and Brown2009; Turk, Brown, Symington, & Paul, Reference Turk, Brown, Symingtion and Paul2010); and awareness of functional deficits (Kaplan, Brown, Adolphs, & Paul, Reference Kaplan, Brown, Adolphs and Paul2012; Mangum, Reference Mangum2018; Miller, Su, Paul, & Brown, Reference Miller, Su, Paul and Brown2018). Although they appear to be secondary products of diminished interhemispheric interactions, slowed processing time, and deficient complex problem-solving, these associated cognitive and social deficits may result in functionally significant impairments in adaptive skills needed in daily life (Mangum, Reference Mangum2018; Miller et al, Reference Miller, Su, Paul and Brown2018) and reciprocal social communication (Paul, Corsello, Kennedy, & Adolphs, Reference Paul, Corsello, Kennedy and Adolphs2014).

MODERATING FACTORS

Expression of these core deficits will vary across the lifespan, as a consequence of neuroanatomic variations and concomitant conditions, and in relation to individual traits and context. We offer brief comments on each of these influences.

Since the corpus callosum in neurotypical children is undergoing significant myelinization and functional development into the teenage years (Giedd et al., Reference Giedd, Castellanos, Casey, Kozuch, King, Hamburger and Rapoport1994; Yakovlev et al., Reference Yakovlev, Lecours and Minkovski1967), the core deficits of AgCC described above may not become pronounced relative to peers before late childhood (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Brown, Adolphs, Tyszka, Richards, Mukherjee and Sherr2007). Consistent with this, we found that processing speed and problem-solving scores were consistent with FSIQ in younger children with Primary AgCC, but fell significantly below FSIQ in an older sample (over 13 years; Schieffer, Paul, Schilmoeller, & Brown, Reference Schieffer, Paul, Schilmoeller and Brown2000). Nonetheless, older children with AgCC may fall behind their peers when tasks are sufficiently complex (Garrels et al., Reference Garrels, Paul, Schieffer, Florendo, Fox, Turk and Brown2001) or novel (Young et al., Reference Young, Erickson, Paul and Brown2013) for their developmental level. Thus, tasks that can be mastered through practice, such as reading and arithmetic, are more likely to be impaired in children with AgCC than in adults. In contrast, tasks such as social interaction and complex problem-solving become increasingly complex in adolescence and remain complex and somewhat novel throughout life, posing an ongoing challenge to individuals with AgCC (e.g., Kang et al., Reference Kang, Paul, Castelli and Brown2009; Turk et al., Reference Turk, Brown, Symingtion and Paul2010; Mangum, Reference Mangum2018; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Su, Paul and Brown2018).

It is reasonable to expect that the impact of AgCC would vary in relation to degree of callosal absence, with partial AgCC resulting in less severe manifestations of these deficiencies than complete AgCC. However, although most of the research cited in this study focused on complete AgCC, studies that included persons with partial AgCC found their performances were distributed among the results of individuals with complete. While the explanation for this is not yet clear, it is possible that outcomes in partial AgCC are impacted by individual variations in how the remaining callosal interhemispheric connections are organized (Wahl et al., Reference Wahl, Strominger, Jeremy, Barkovich, Wakahiro, Sherr and Mukherjee2009).

Up to 45% of individuals with AgCC have a known chromosomal abnormality or recognizable genetic syndrome, often resulting in additional neuropathology and/or medical conditions (i.e., not Primary ACC). The nature and severity of these additional conditions will influence expression of the core deficits from AgCC and at the extreme may render the core deficits functionally irrelevant in daily life.

Finally, there is inherent variations between individuals, as well as environmental influences. For example, although general intelligence did not account for the core deficits described herein, general intelligence or specific skill sets may modulate an individual’s complexity threshold and markedly impact an individuals’ daily adaptive functioning.

CONCLUSION

Research has accumulated over the past 2 decades allowing for the description of a pattern of deficits characteristic of AgCC. We have argued for a core syndrome associated with callosal absence in AgCC involving reduced interhemispheric transfer of sensory-motor information, slowed cognitive processing speed, and deficits in complex reasoning and novel problem-solving. However, because these cognitive deficiencies are typically mild to moderate, they are often not easily recognized. It is our hope that a better description of the cognitive and psychosocial impact of AgCC will increase the likelihood of a diagnostic MRI in these high-functioning cases, as well as provide more complete information and helpful guidance to patients and their families regarding the likely consequences of this congenital brain disorder.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors of this study declare that they have no conflicts of interest with respect to the writing of this study or the information contained. The writing of this study was also not supported by grant funding.