INTRODUCTION

Human sacrifice in past societies is inferred through examination of the specific archaeological contexts harboring human remains, such as the initial construction or modification of buildings where sacrifice was part of the consecration of these activities (Cook de Leonard Reference Cook de Leonard, Ekholm and Bernal1971; Jarquín and Martínez Reference Jarquín and Martínez1991; López Lujan et al. Reference López Luján and Olivier2010; Rattray Reference Rattray1992; Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2005, Reference Sugiyama, Luján and Olivier2010). Generally, mortuary contexts with simultaneous multiple primary interments are assumed to indicate the practice of sacrifice, since they were part of the same event of ritual violence (Pereira Reference Pereira, Sánchez and Mata2007:92). These circumstances suggest unnatural deaths, such as the sacrifice of companions to accompany a central figure in death (Harrison Reference Harrison1999:59; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2000:53; Ruz Reference Ruz1968), although these burials are not guaranteed to be victims of sacrifice—an alternative interpretation is the reuse of tombs (Ducan Reference Ducan2011; Tiesler Reference Tiesler, Tiesler and Cucina2007:15–17; Weiss–Krejci Reference Weiss-Krejci, Ruiz, Sosa and Ponce de León2003:373–374).

The human body is itself an indicator of sacrifice, providing palpable skeletal evidence of this practice with the perimortem and post mortem violence that permit its detection. Taphonomic study involves the observation of perimortem traumas, cut marks, and exposure to fire (Pijoan and Mansilla Reference Pijoan, Mansilla, Martin and Frayer1997; Tiesler Reference Tiesler, Tiesler and Cucina2007; Turner and Turner Reference Turner and Turner1999). Even biological data, including age and sex of the individuals involved, provide information about the ritual performed, an example of which is the sacrifice of war captives by the Aztecs, where men were offered in rituals dedicated to certain deities, including Huitzilopochtli, god of war and god of the sun, and Xipe Totec, “our flayed lord” (González Reference González2016:23; Sahagún Reference Sahagún1829:bk. 1, pp. 51–52), or the rituals dedicated to Tlaloc (rain god) to whom children were offered (Durán Reference Durán1880:136–139; Motolinía Reference Motolinía and Levy1967:63; Sahagún Reference Sahagún1829:bk. 1, pp. 50, 84–86).

Various authors have noted that ritual infanticide is present throughout time in different societies across the world (e.g., Benson Reference Benson, Benson and Cook2001; Bourget Reference Bourget, Benson and Cook2001; Hughes Reference Hughes1991; Klaus Reference Klaus, Benson and Cook2001; Palkovich Reference Palkovich, Martin, Harrod and Pérez2012; Tung and Knudson Reference Tung and Knudson2010; Verano Reference Verano, Benson and Cook2001). In Mesoamerica, child sacrifice is a well-known practice, although there is currently no knowledge about the possible role of children in Toltec rituals.

The present study concerns the discovery of a massive deposit of human remains at the Early Postclassic city of Tula approximately one kilometer from Tula Grande, the city's sacred precinct (Figure 1), involving at least 49 individuals, most of whom were children, buried in a seated position. Designated Feature 5, the deposit underlay the open patio and altar near a sculpture of Xipe Totec buried in a neighboring compound. The first objective of this study was to determine biological characteristics of the individuals: age, sex, and health conditions. Due to the characteristics of the archaeological context, the hypothesis proposes the 49 individuals were the result of ritual sacrifice that does not correspond to Toltec funerary customs. I believe there is a link between Feature 5 and the nearby sculpture of Xipe Totec.

Figure 1. Location of Tula Archaeological Zone and Procuraduría General de la República (PGR) locality. Image from Google Earth.

HUMAN SACRIFICE IN CENTRAL MEXICO

When the Spanish arrived in Mesoamerica, one of the aspects that most surprised and shocked them was the practice of human sacrifice. This practice, which has a highly religious significance, represents ritual death to obtain a benefit from the deities (Broda Reference Broda1971; López Austin and López Luján Reference López Austin, Luján, Brumfiel and Feinman2008:145), thus establishing an intimate relationship with the supernatural (González Torres Reference González Torres1994:39) as well as satisfying political, economic, and military ends (Boone Reference Boone1984; González Torres Reference González Torres, Luján and Olivier2010:402; López Austin and López Luján Reference López Austin, Luján, Brumfiel and Feinman2008:146). The practice also is linked to ceremonies associated with the construction of buildings (Rattray Reference Rattray1992:12, 53; Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama, Luján and Olivier2010) and social prestige, as in the case of gladiatorial sacrifice (González Reference González, Luján and Olivier2010; González Torres Reference González Torres, Luján and Olivier2010:402; Graulich Reference Graulich2005). In Mesoamerica, much of our knowledge of this practice is from the Aztecs, since there is detailed documentation in the chronicles of friars such as Bernardino de Sahagún and Diego Durán, as well as others such as Juan Bautista de Pomar. Other sources of information are the pre- and post–Conquest codices, such as Codices Borgia, Tudela, Vaticano A (Ríos), Magliabechiano, Borbón, Aubin, Florentino, and others.

However, human sacrifice was not exclusive to the cultures of the central highlands and the Late Postclassic period. There are numerous examples in the ceramics, murals, and sculpture iconography as well as archaeological and bioarchaeological evidence of its prevalence throughout Mesoamerica from as early as the Archaic period (Boone Reference Boone1984; Graulich Reference Graulich2005; López Luján and Olivier Reference López Luján and Olivier2010; Pijoan and Mansilla Reference Pijoan and Mansilla2007, Reference Pijoan, Mansilla, Luján and Olivier2010b; Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2005; Tiesler and Cucina Reference Tiesler and Cucina2007). In the Mesoamerican world view, children were linked to water, fertility and the divine (Ardren Reference Ardren2011; Broda Reference Broda1971; Chávez Reference Chávez and Morfín2010a, Reference Chávez, Luján and Olivier2010b; Román Reference Román, Luján and Olivier2010), therefore aptly appreciated as sacrificial offerings.

CHILD SACRIFICE IN MESOAMERICA

Bioarchaeological Evidence

Osteological evidence of physical alterations including cut marks, fractures, and exposure to fire evoke practices related to violence and cannibalism (Pijoan and Mansilla Reference Pijoan, Mansilla, Martin and Frayer1997; Tiesler Reference Tiesler, Tiesler and Cucina2007; Turner and Turner Reference Turner and Turner1999), manifested not only in the remains of adult men and women but children as well. There are several examples, including those reported in the site of Tlatecomilla, Tetelpan in Mexico City dated to c. 300 b.c., where the remains of five children under the age of 12 were recovered from a deposit of mixed sherds and animal bones indicative of domestic refuse, suggesting they had been eaten (Pijoan and Masilla Reference Pijoan, Mansilla, Martin and Frayer1997). Among the remains was a skull with a semicircular cut. In Tlatilco, a Preclassic village, a child with cut marks interpreted to be a result of ritual cannibalism was reported (Faulhaber Reference Faulhaber1965), although a subsequent study showed that these marks were caused by rodents (Piojan Reference Pijoan, Pijoan, Lizarraga and Valenzuela2010:17). Ortiz and Rodríguez (Reference Ortiz, del Carmen Rodríguez, Grove and Joyce1999:248) have identified a possible child sacrifice from the time of the Olmecs (1600–1000 b.c.) at Cerro El Manatí, Veracruz, based on a massive deposit of carved wooden busts, rushes, and other plants, a skull and other scattered children's bones, and two primary neonatal burials. However, a formal bioarchaeological and taphonomic study are needed to confirm this interpretation.

Still older is the recovery of a pair of children possibly sacrificed from Coxcatlán cave, Tehuacán, Puebla, which produced a radiocarbon date reported as 5750 b.c. +/–250, corresponding to the El Riego phase. One of the two was seven years old, whose skull was placed in a basket after being exposed to fire. Another child, less than six months old, likewise had the skull removed and placed in a basket. Both exhibited cut marks consistent with defleshing (Pijoan and Mansilla Reference Pijoan and Mansilla2007, Reference Pijoan, Pijoan, Lizarraga and Valenzuela2010).

Evidence from central Mexico includes the Late Formative settlement of Xochitecatl, Tlaxcala, where a child's burial was found adorned with shell beads and one green stone bead; the body had been placed in the staircase of a pyramidal structure dedicated to the worship of fertility and rain, presumably an offering. At El Gallo Cave, Morelos, excavators recovered an offering consisting of a child burial accompanied by the remains of a dog and countless organic materials (Manzanilla Reference Manzanilla, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000:92, 95).

At the site of Teotihuacan, there are several reported discoveries of offerings involving children, including fetal and perinatal individuals discovered inside altars at La Ventilla that have been interpreted as sacrifices made to Tlaloc (Jarquín and Martínez Reference Jarquín and Martínez1991). Serrano and Lagunas (Reference Serrano and Lagunas1974:134–135) further interpreted these remains as the product of induced abortion for ritual purposes at the time of the construction of the altars, although Storey (Reference Storey1985:531) points out that perinatal mortality is often a consequence of precarious maternal health conditions. It is also possible that the perinatal burials found in these altars were linked to child sacrifice, since some individuals exhibited cut marks (Cid and Torres Reference Cid and Torres1997:94). Rattray (Reference Rattray1992:12, 53) believes that the children found in the La Ventilla altars were sacrificed as part of ceremonies to mark new phases of construction, particularly in the Late Xolalpan phase.

Elsewhere at Teotihuacan, burials of children were discovered on the Plaza 1 platform at Oztoyahualco, interpreted as evidence of sacrifice (Cook de Leonard Reference Cook de Leonard1957:1). Child sacrifice at Teotihuacan is also represented by the remains of six-year-old children placed in a sitting position at each corner of the Pyramid of the Sun, presumeably linked to ceremonies to mark the beginning of new construction (Batres Reference Batres1906:22), which may be related to the cult of Tlaloc (Matos Moctezuma Reference Matos Moctezuma, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000:190). Finally, according to Manzanilla (Reference Manzanilla, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000:100–101), an altar dedicated to the Tlaloque was built in the tunnel beneath the Pyramid of the Sun, in which seven children were found to have been offered in sacrifice to Tlaloc.

Various reported instances of child burials that have been interpreted as evidence of dedicatory sacrifice related to construction activity are supported by circumstances of their location and context (Cook de Leonard Reference Cook de Leonard1957, Reference Cook de Leonard, Ekholm and Bernal1971; Jarquín and Martínez Reference Jarquín and Martínez1991; Manzanilla Reference Manzanilla, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000; Matos Moctezuma Reference Matos Moctezuma, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000; Millon Reference Millon, Bricker and Sabloff1981; Rattray Reference Rattray1992; Serrano and Lagunas Reference Serrano and Lagunas1974; Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2005, Reference Sugiyama, Luján and Olivier2010). It would, however, be a worthwhile effort to conduct a detailed bioarchaeological study to evaluate the veracity of these interpretations.

The most salient discoveries of skeletal remains pertaining to child sacrifice are from the Mexica culture, most notably the recently discovered offerings at the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan that included remains of children that had been placed inside vessels bearing the faces of pluvial deities (Chávez Reference Chávez and Morfín2010a, Reference Chávez, Luján and Olivier2010b; López Luján et al. Reference Luján, Leonardo, Valentín, Montúfar, Luján and Olivier2010; Román Reference Román, Luján and Olivier2010) and the Metropolitan Cathedral (Román Reference Román, Luján and Olivier2010). Associated objects included turquoise mosaics, shells, and hawk wings. Suggested interpretations are that these children were sacrificed for three reasons: (1) requests for rain made mainly to Tlaloc but also to the fertility deities; (2) activities related to war, including the celebration of triumph in battles—one example of which is Offering 111, which contained a child adorned with an insignia that personifies Huitzilopochtli as the god of war, a breastplate and bracelet composed of rattles and snails, and the skeletal remains of a hawk; and (3) the celebration of special ceremonial events in the calendar as well as others celebrating the construction or expansion of buildings (Chávez Reference Chávez and Morfín2010a:291; López Lujan et al. Reference Luján, Leonardo, Valentín, Montúfar, Luján and Olivier2010:387).

Children were sacrificed to Huitzilopochtli, as indicated by the discoveries of Offering 42 in the Templo Mayor at Tenochtitlan (López Luján et al. Reference Luján, Leonardo, Valentín, Montúfar, Luján and Olivier2010). Given that the Mexica maintained a strong association between war and agriculture, it is unsurprising that children were offered to the warrior gods. Other ceremonies involving child sacrifice include specific events, such as the drought that occurred in 1454 (López Luján Reference López Luján1993; López Lujan et al. Reference Luján, Leonardo, Valentín, Montúfar, Luján and Olivier2010:368; Román Reference Román, Luján and Olivier2010:359).

The children found in the offering at the Templo Mayor were immolated differently, depending upon the deity to whom they were presented. Those dedicated to Tlaloc had their throats cut, while those sacrificed to Huitzilopochtli had their hearts removed (Chávez Reference Chávez and Morfín2010a: 295–296; López Austín and López Luján Reference López Austin, Luján, Brumfiel and Feinman2008:140).

Additional bioarchaeological examples of child sacrifice from central Mexico are the 30 children discovered during salvage excavations at the Templo Ehecatl–Quetzalcoatl (Templo “R”) in the neighboring Mexica city of Tlatelolco, almost all of whom were males whose health was in poor condition (Román Reference Román, Luján and Olivier2010). Elsewhere in Tlatelolco, a burial deposit designated Entierro 14 contained a minimum of 152 individuals, including three children, all of whom had been interred at the same time. The majority exhibited cut marks and impact damage from both percussion and pressure tools. Another burial deposit (Entierro 270) contained 104 mandibles, where fewer than five percent belonged to children (Pijoan and Mansilla Reference Pijoan, Mansilla, Luján and Olivier2010b).

Ethnohistorical Perspectives

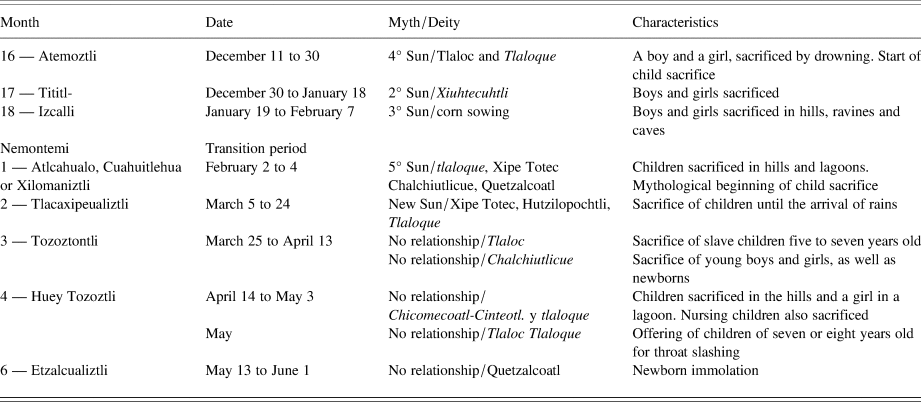

In the central highlands, ethnohistorical references to human sacrifice include references to child sacrifice generally linked to the rituals dedicated to various Nahuatl deities in conjunction with the Mexica calendar. Table 1 shows the months in which children were offered in sacrifice, noting that this activity started in our December during the month Atemoztli, “lowering of water,” involving ceremonies celebrating Tlaloc while requesting water for sowing (Codex Magliabechiano 1970:88). It is during this month that the fourth sun was recreated and celebrations made to the Tlaloque. Child sacrifice continued in subsequent months, ending in Huey Tozoztli and Etzalcualiztli, our May, with the sacrifice of children, whose throats were cut, in offerings to Tlaloc and the Tlaloque in rituals linked to rain and agricultural activity (Broda Reference Broda1971:321). Thus the rituals during the month Atemoztli spanned the period of the dry season until the arrival of the rainy season.

Table 1. Ceremonies in the Mexica calendar involving child sacrifice.

Rain was synonymous with abundance, sprouting, greenery, flowering, and the growth of maize, the basis of Nahuatl sustenance. The opposing scenario of drought was the loss of sustenance causing food shortage, and those who had the power to provoke this were the Tlaloque, which they did as punishment for situations arousing their anger. An important component of child sacrifice in the central highlands was its association with the aquatic deities, among them Tlaloc and the Tlaloque, “ministers of the small body,” who were servants of Tlaloc. In the same way, Ehecatl, god of wind, was part of the Tlaloque, and Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, in the guardianship of Tlaloc was himself affiliated with the gods of rain. Chalchiuhtlicue, goddess of the waters of the springs, rivers, and lakes, was the older sister of the Tlaloque (Broda Reference Broda1971:250–255, 260). Another deity that belonged to the complex of the divinities of water and fertility was Xipe Totec, “our lord the flayed one” (Broda Reference Broda1971:256, n8), whose wearing of corpse skin symbolized regeneration. Sahagún (Reference Sahagún1829:bk. 1, p. 58; Reference Sahagún1577:f. 18) reports that at the tlacaxipeoaliztli festival, captive men, women, and children were offered to Xipe Totec and Huitzilopochtli.

In the month Atlcahualo, children were sacrificed as part of ceremonial requests for rain dedicated to the Tlaloque, Chalchiutlicue, or Quetzalcoatl (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1829:bk. 1, p. 49; Reference Sahagún1577:f. 3), while in the month Huey Tozoztli a festival was held honoring Chicomecoatl–Cinteotl, goddess of maize, during which children were immolated, and additional ceremonies for the Tlaloque were also made (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1829:bk. 1, p. 64). Durán (Reference Durán1880:136–139) describes in detail a festival honoring Tlaloc of great importance involving child sacrifice: “… en amaneciendo salían todos estos reyes y señores con toda la demás gente y tomaban un niño de seis o siete años….delante la imagen del ydolo tlaloc, matauan aquel niño dentro en la litera….benian los sacerdotes que hauian degollado aquel niño…”

The link between the water deities and the child offerings are the tears shed before sacrifice, symbolizing rain: “Cuando llevaban los niños á matar, si lloraban y echaban muchas lágrimas, alegrábanse los que los llevaban porque tomaban pronóstico de que habían de tener muchas aguas en aquel año” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1829:bk. 1, p. 50; Reference Sahagún1577:f. 3). The evenings, filled with dances and songs, prevented children from falling asleep, causing them to tire and weep (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1829:bk. 1, p. 86). Therefore, the rain meant abundance: bud, greenery, and the flowering and growth of corn. A contrary scenario, the drought was the loss of livelihood, causing food shortages; the Tlaloques were the ones who had the power to provoke it, as punishment for their anger.

Child immolation was also offered before undertaking military action, as mentioned in the confrontation of the Cholulans against the army of Hernán Cortés: “y los sacerdotes sacrificaron a su Quetzalcouatl diez niños de tres años, las cinco hembras; costumbre que tenían comenzando alguna Guerra” (López de Gómara Reference López de Gómara2007:121).

WHO WERE THE CHILDREN OF SACRIFICE?

Child sacrifice was a cultural practice that occurred in prehispanic Mesoamerica, most commonly during the Postclassic period, as indicated by both bioarchaeological evidence and ethnohistorical data noted above. Bioarchaeological studies in the central highlands have identified instances of sacrificed children ranging from two to nine years of age (Chávez Reference Chávez and Morfín2010a:294–296, Reference Chávez, Luján and Olivier2010b:325; López Luján et al. Reference Luján, Leonardo, Valentín, Montúfar, Luján and Olivier2010:375). But who were the children offered for sacrifice—that is, how they were selected? Did they share any peculiarities? The ethnohistorical sources indicate that children chosen for sacrifice ranged in age from newborns to eight year olds and could be either sex. In the Codex Magliabechiano (1970:62), it is noted that in the Festival of Tozoztli, “sacrificaban los niños pequeños y las mujeres niñas y también recién nacidos.” During the festivities to the Tlaloque in the month of Atlcoahualo, breastfed children were sacrificed, as detailed by Sahagún (Reference Sahagún1829:bk. 1, p. 84). In the month Etzalcualiztli honoring Quetzalcoatl representing Tlaloc, newborn children were immolated (Codex Magliabechiano 1970:68), and on the feast of Tocitoztli honoring the goddess of maize, “niños de teta” were offered (Codex Magliabechiano 1970:68). The slaughtered children could be anywhere from three to eight years old (Durán Reference Durán1880:137; López de Gómara Reference López de Gómara2007:121; Motolinía Reference Motolinía and Levy1967:64; Pomar Reference Pomar1821:18).

Sahagún (Reference Sahagún1829:bk. 1, p. 84) states that children offered in sacrifice had to have certain attributes, such as being born under a positive calendrical sign, having two hair swirls on their heads, or purchased from their mothers, an indication that they belonged to families with low social status. However, Motolinía (Reference Motolinía and Levy1967:63) affirms that there were also children of nobility given in sacrifice by their parents, as indicated in the Codex Magliabechiano (1970:68), where he notes that the parents provided “niños de teta” specifically for sacrifice during the feast of the goddess of maize. The bioarchaeological data indicate that children selected for oblation must satisfy one other requirement: a bad state of health (Chávez Reference Chávez, Luján and Olivier2010b:234; Román Reference Román, Luján and Olivier2010:361).

TULA, THE TOLTECS, AND HUMAN SACRIFICE

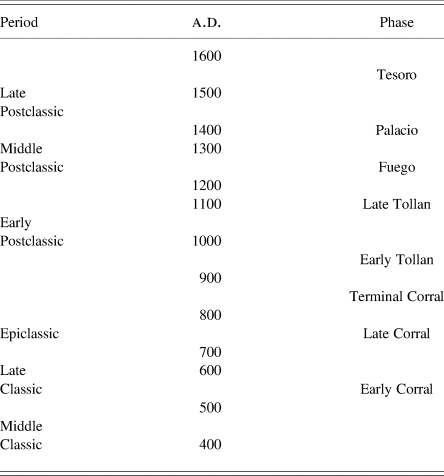

Tula, believed to be the ruins of Tollan, the city of the Toltec civilization of Aztec legend, is located in central Mexico on the northwestern flank of the Basin of Mexico (Figure 1). Archaeological investigations conducted over the last 40 years (Cobean et al. Reference Cobean, Jiménez and Mastache2012; Gamboa Cabezas and Cobean Reference Gamboa Cabezas, Cobean, Nichols and Alegría2017; Healan Reference Healan2012) revealed that Tula originated as a modest settlement around a.d. 650 and grew to a city of ca. 16 square kilometers during the Early and Late Tollan phase (c. 900–1150 a.d.; Table 2).

Table 2. Chronology for the Tula region.

Both ethnohistorical and archaeological data indicate that human sacrifice played a critical role in Toltec society and religion. Ethnohistorical accounts note a famine at Tula lasting seven years that inflicted many deaths and led to the sacrifice of a large number of people, which is said to have given rise to the practice of child sacrifice known as tlacatetéhuitl (Broda Reference Broda1971:272), literally “human strips,” which occurred during the festival dedicated to Xipe Totec (González Reference González2016:66).

Pomar (Reference Pomar1821:15) provides a narrative of the adoration of Tlaloc in Tenochtitlan that includes the following: “estaba el ídolo el rostro al Oriente: hacíanle sacrificio de niños inocentes, cada año una vez…. No saben dar razón quién lo labró, ni por qué lo adoraban por dios de los temporales…. hay sospechas que lo hicieron un género de gentes que llamaron Tulteca.” According to Broda (Reference Broda1971:275), child sacrifice began in Tula, when the Tlaloque and the last Toltec ruler, Huemac, played a ball game, according to mythology. Huemac was the winner; the Tlaloque paid with ears of maize, but Huemac rejected them, and so the Tlaloque left, taking the rain and causing an intense drought that destroyed the city. After four years, the Tlaloque returned to demand the sacrifice of the leader Tozcuecuex's daughter, delivering rain and the rising of the fifth sun.

Archaeological evidence of sacrifice can be seen at the site today, including the chacmools, anthropomorphic sculptures with the trappings of war, including a butterfly breastplate and a forearm band holding a knife apron, in a semi–flexed position and believed to be ritual furniture used in sacrifice or to hold the hearts of sacrificial victims (Jordan Reference Jordan2020:69; López Austin and López Luján Reference López Austin and Luján2001a:62; López Luján and Urcid Reference López Luján and Urcid2002:32; Miller and Samayoa Reference Miller and Samayoa1998:67). Graulich (Reference Graulich, Luján and Olivier2010) believes the chacmools personify the Tlaloque, while Miller and Samayoa (Reference Miller and Samayoa1998) link them to the sacrifice of prisoners of war and slaves, associated with Tlaloc and maize deities.

Toltec iconography includes the representations of skeletonized human figures, such as those depicted in the Coatepantli, “serpent wall,” associated with the deity Tlahuizcalpantecutli, “star of the morning” (Acosta Reference Acosta1956), one of Quetzalcoatl's incarnations. This wall is topped with almenas, sculptural ornaments that represent the cut shell motif, which also evoke Quetzalcoatl (López Austín and López Luján Reference López Austin and Luján2001b:203). The importance of Tlaloc, a deity associated with human sacrifice among the Toltecs, is also evident in his representation in braziers found in both domestic and ceremonial contexts (Acosta Reference Acosta1956–1957; Mastache et al. Reference Mastache, Cobean and Healan2002).

Archaeological evidence of human sacrifice at Tula includes the tzompantli, or skull rack, common to Mexica culture (Chávez Reference Chávez, Robles, Aguirre and de Anda2015, Reference Chávez, Tiesler and Lozada2018; López Reference López Luján1993; Ragsdale Reference Ragsdale, Edgar, Heather and Melgar2016:365; Solari Reference Solari2008; Wade Reference Wade2018), consisting of a rectangular platform in front of Ballcourt 2 at Tula Grande (Mastache and Cobean Reference Mastache and Cobean2000:126; Matos Moctezuma Reference Matos Moctezuma1972, Reference Matos Moctezuma1974, Reference Matos Moctezuma1976). The structure was dated to the Aztec occupation based on associated ceramics and an offering found inside, although the structure is almost certainly Toltec given its mode of construction and the likelihood that the offering was intrusive (Healan Reference Healan2012:63).

Other evidence comes from salvage excavations at the site of the construction of the Museo Jorge Acosta that encountered over 121 burials, including 53 dated to Tula's Early Postclassic Tollan phase apogee. Evidence of human sacrifice of children and adults in the form of decapitated skulls, some with traces of fire exposure (Gómez et al. Reference Gómez, Sansores and Fernández1994:100), and secondary burials that appear to have been pre-construction dedicatory offerings (Gómez et al. Reference Gómez, Sansores and Fernández1994:95) were recovered.

THE PGR LOCALITY AND THE CHILDREN OF FEATURE 5

In 2007 and 2009, an archaeological salvage project was conducted at the site of the construction of the Procuraduría General de la República (PGR), located immediately east of the southeast corner of the Tula Archaeological Zone (Figures 1 and 2). Under the direction of Luis Gamboa Cabezas, excavation partially exposed the remains of several structures that represent a series of adjacent residential compounds designated OP1, OP2, and OP3 (Figure 2), each oriented roughly north-south. The three compounds contained several highly unusual features unlike anything previously found in Tula (Gamboa Cabezas and Healan Reference Gamboa Cabezas and Healan2021).

Figure 2. The PGR locality (inset), Operations (OP) 1, 2, 3, and various findings discussed in the text: a, Feature 5; b-e, probable seated individuals in OP2 f, hollow ceramic sculpture of Xipe Totec in OP3. From Gamboa Cabezas and Healan Reference Gamboa Cabezas and Healan2021.

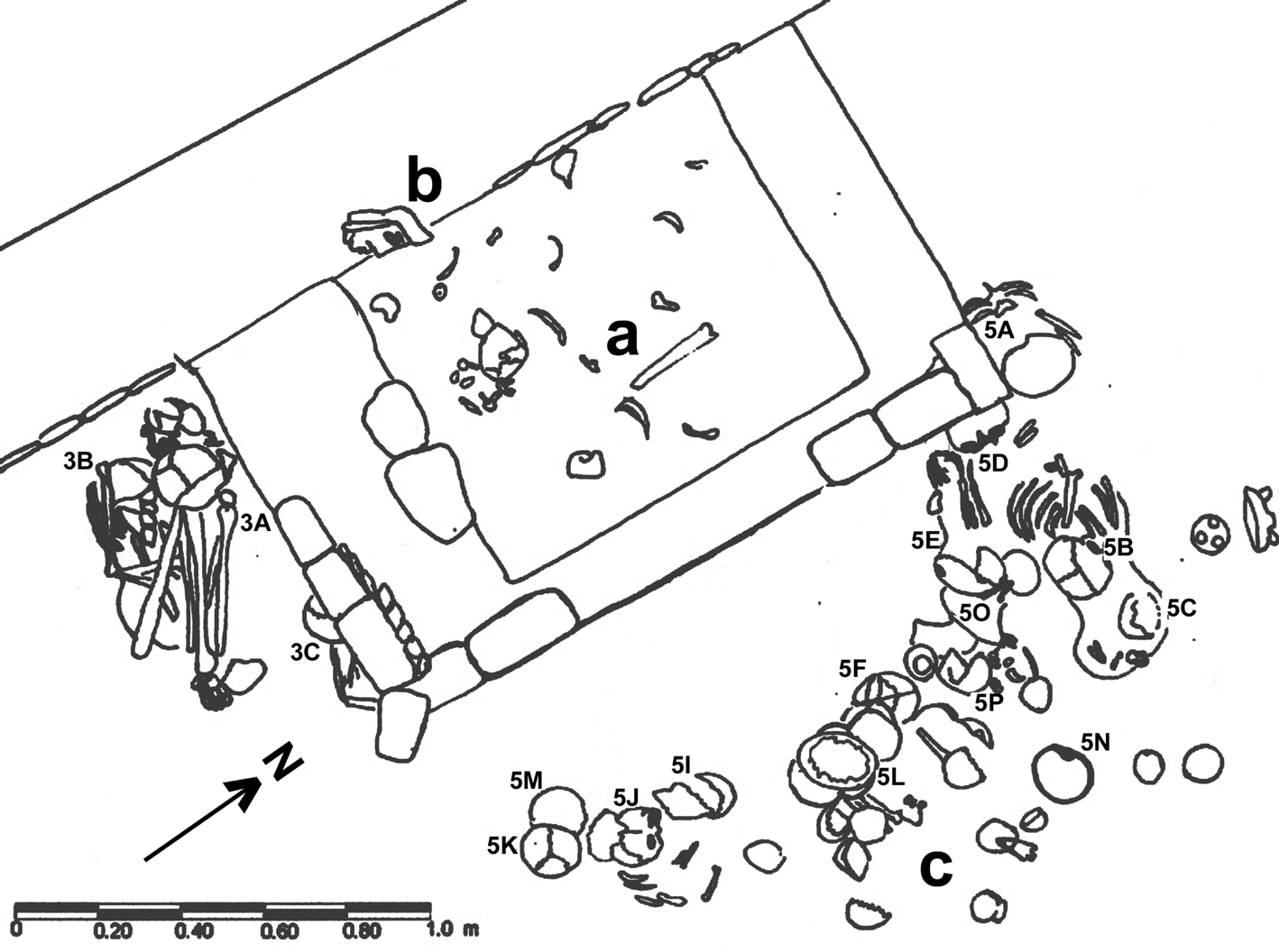

OP1, the westernmost of the three, includes an exterior patio surrounded by platforms supporting one or more buildings (Figure 2). The patio floor was covered with stucco and contained a prominent rectangular altar that adjoined the western wall. The altar had been partially dismantled in prehispanic times and contained fragments of a skull, long bones, and other body parts that indicated a child's burial, as well as loose adult bones (Figure 3a). A stone replica of a human head (Figure 3b) had been placed on top of the altar, and nearby was a fragment of a carved stone slab containing a representation of the h–j–p figure common at Tula Grande and elsewhere (Jiménez García Reference Jiménez García2021).

Figure 3. Detailed view of excavations in patio, OP1: a, human bones inside altar; b, head portion of human sculpture; c, Feature 5. Number/letter designations in Feature 5 refer to clusters of bones assigned and recovered as “burials” by excavators. From Gamboa Cabezas and Healan Reference Gamboa Cabezas and Healan2021.

Excavation beneath the patio floor encountered a massive deposit of human remains (Figures 2a and 3c). Designated Feature 5, the deposit includes the remains of a large number of individuals, mostly children, that is the subject of this article.

OP2 and OP3 also contained human remains, as described by Gamboa Cabezas and Healan (Reference Gamboa Cabezas and Healan2021). OP3 additionally contained a small, partially exposed stepped platform (Figure 2) partially overlying a shallow depression covered with stone slabs that contained a hollow ceramic sculpture (Figure 2f) some 1.4 meters in length of the deity the Aztecs called Xipe Totec (Gamboa Cabezas Reference Gamboa Cabezas2012; Gamboa Cabezas and García Reference Gamboa Cabezas and García2016; Gamboa Cabezas and Healan Reference Gamboa Cabezas and Healan2021:Figure 20). Some 15 meters northeast of OP1, exploratory excavation in Unit 16 encountered a burial of two children, whose remains are included in the summary sections below.

Feature 5 forms an arc-shaped distribution in front of the altar (Figures 2a and 3), although the deposit lies beneath the patio floor and altar, hence predates their construction. Excavation revealed that Feature 5 was deposited on a natural surface a few centimeters above tepetate, a caliche layer that constitutes the local bedrock, which lay approximately 50 centimeters below the OP1 patio floor, with an intervening fill rich in artifacts and scattered human bone presumably derived from Feature 5.

As seen in Figure 3, the remains formed distinct clusters, each of which was designated by Gamboa Cabezas (Reference Gamboa Cabezas2007) as a burial and recovered as a single entity. Some 18 such “burials” were recovered from Feature 5, designated 5A–R (Figure 3). Three additional “burials” (Figure 3:3A–3C) encountered along the south side of the altar were initially designated Feature 3, but are believed to be part of Feature 5.

LABORATORY METHODS

Analysis of the Feature 5 skeletal remains was performed in the bodega at the Museo Jorge Acosta in the Tula Archaeological Zone, where the remains are currently stored. Henceforth, I will use the term “cluster” to refer to what were designated burials during excavation, given that it appears to be a single massive funerary deposit. However, I have retained the nomenclature (5A–5S, 3A–3C) that was originally assigned to the “burials” to maintain consistency, hence each cluster is identified by Feature number (5 or 3), plus a Roman letter.

During analysis, each individual was identified by their cluster affiliation; hence, the individual in cluster 5A is referred to simply as individual 5A. Several clusters contained more than one individual, and the nomenclature was modified to indicate this. For example, the two individuals in cluster 5B are designated individuals 5B-1 and 5B-2.

The determination of the minimum number of individuals (MNI) was based on quantity, laterality, and compatibility in terms of morphology and size of the osteological elements of each individual.

Estimation of age at death was based on dental eruption for subadults (Ubelaker Reference Ubelaker2003:84) and on measurements of skull and mandible bones when teeth were lacking (Schaefer et al. Reference Schaefer, Black and Scheuer2009). Diaphyseal length of long bones was also assessed (Ortega Reference Ortega1998). In the case of adult individuals, standardized variables from studies in physical anthropology were employed, such as morphological changes in the auricular surface and pubic symphysis, suture fusion, and dental wear (Buikstra and Ubelaker Reference Buikstra and Ubelaker1994).

Estimation of sex in adults was based on established morphoscopic criteria, principally, in the skull and ilium (Buikstra and Ubelaker Reference Buikstra and Ubelaker1994). In subadult individuals, estimation of sex utilized the methodology employed by Estévez et al. (Reference Estévez, López–Lázaro, López–Morago, Alemán and Botella2017), Hernández and Peña (Reference Hernández and Peña2010), Loth and Henneberg (Reference Loth and Henneberg2001), Schutkowski (Reference Schutkowski1987, Reference Schutkowski1993), and Sutter (Reference Sutter2003) based on several morphological features: amplitude of the angle of the greater sciatic notch, curvature of the ilium, and depth of the greater sciatic notch, as well as features of the mandible such as the protrusion of the chin region and shape of the anterior dental arcade, along with the size of the mastoid process in the skull. Sex determination for children over four years of age was evaluated using two variables: the eversion of the gonion and the shape of the supra–orbital margin. Sex was often difficult to estimate since not all individuals still possessed identifiable elements that would facilitate it.

Examination for possible anthropogenic features, such as cut marks, was conducted using a magnifying lens of up to 10×, recording each perceived feature by body segment and drawing the feature. Other alterations, such as exposure to fire and perimortem trauma and fractures, were recorded when observed.

Evaluation of health conditions included the osteopathologies that are defined morphoscopically: (1) infectious processes; (2) micronutritional deficiencies such as iron deficiency through cribra orbitalia and porotic hyperostosis, as well as vitamin C and D deficiency (scurvy and rickets); and (3) oral pathologies—dental caries, abscesses, alveolar resorption, and dental calculus. This information was obtained to assess the role that health status may have played in the selection of children offered in sacrifice, according to the information derived from the investigations carried out by Román (Reference Román, Luján and Olivier2010:360–361).

BIOLOGICAL CHARACTERIZATION, ANTHROPOGENIC ALTERATIONS AND HEALTH CONDITIONS

Table 3 summarizes the age at death and sex distributions of Feature 5 in OP1. Bioarchaeological analysis determined a total of 49 individuals, of which only two (4.1 percent) are over 18 years old. The remaining 47 are subadults, which include the individuals in the 15–19 age group who have an average estimated age of 17 years. The complete and almost complete individuals were found in a sitting position (Gamboa Cabezas Reference Gamboa Cabezas2007; Gamboa Cabezas and Healan Reference Gamboa Cabezas and Healan2021), a common position for both children and adults for Early and Late Tollan phase interments at Tula. Of the 39 burials recovered from the salvage excavations at the construction site for the current Museo Jorge Acosta, 13 individuals (33.3 percent) were buried in that position (Gómez et al. Reference Gómez, Sansores and Fernández1994).

Table 3. Distribution of age and sex of the individuals from Feature 5.

Notably, the adult individuals in Feature 5 are represented by loose bone elements. One example is the adult bones from inside the altar that include the left humerus and minor bones of the hands and feet, some teeth, and a fragment of the spinous process of a cervical vertebra. Another example is burial 5D, consisting of a fragment of the diaphysis of the ulna. An exception was individual 5R, discussed below, a male adult of 25–30 years, consisting of an articulated skull, mandible, hyoid bone, and cervical vertebrae.

Feature 5 includes five fetuses from 30 weeks gestation to newborns, representing 12.2 percent of the 49 individuals. The largest number of individuals are in the age range from three months to 2 years, at just over half of the osteological sample (Table 3). Using the methods for determining sex described above, 9 (18.4 percent) of the 49 individuals were identified as females, 8 (16.3 percent) as males, and 32 (65.3 percent) were indeterminate and mostly the remains of incomplete individuals (Table 3).

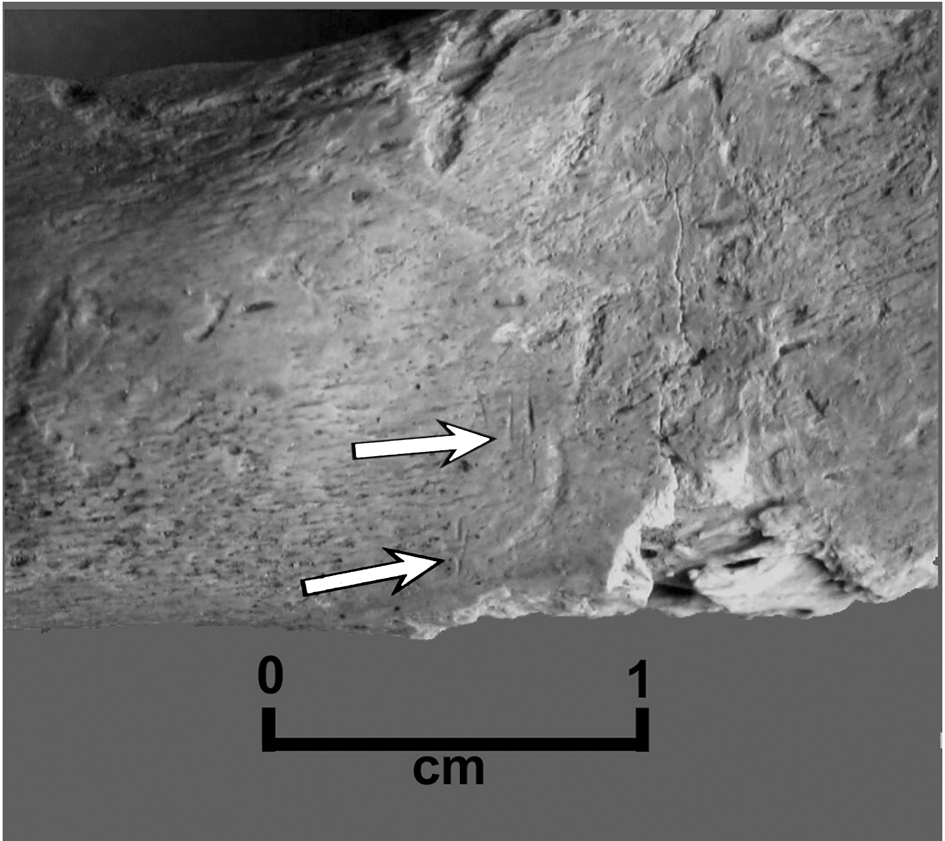

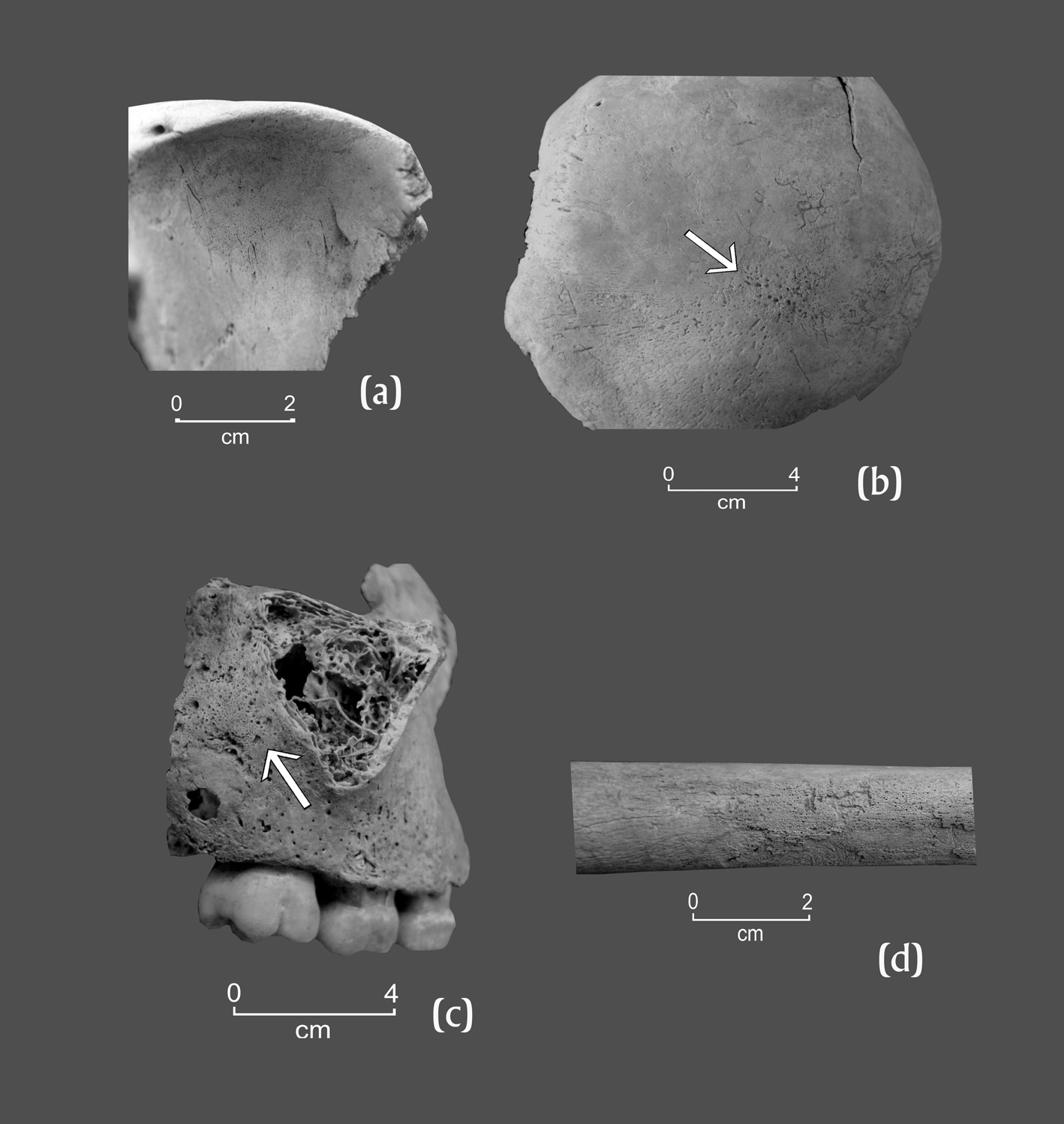

Examination revealed that 34 of the 49 individuals (69.4 percent) did not exhibit visible alterations, while the remaining 15 individuals, plus loose bones of several associated individuals, exhibited various kinds of anthropogenic features (Table 4). Cut marks were observed on the crania of 16 individuals and on a loose malar bone. A peculiarity of the cut marks on the skulls is that they involve scraping characterized by small areas with multiple striations (Figure 4), in some cases visible only under magnification. Some specimens exhibited fine linear cut marks on various bones, including three mandibles (Figure 5). Cut marks also were detected on the long bones of several individuals (Figure 6), and, in two cases, on the inner surface of a rib. One of the latter two, individual 5H, also exhibited scraping on various parts of the skull, and the other, individual 5J–1, showed cuts on the left malar bone and right ulna (Table 4).

Table 4. Individuals from Feature 5 with anthropogenic modifications.

Figure 4. Frontal bone of individual 3B, showing cut marks (arrow). Photograph by author.

Figure 5. Mandible of individual 5F, showing cut marks (arrows). Photograph by author.

Figure 6. Right humerus of individual 5F, showing cut marks (arrows). Photograph by author.

Individuals 5F, 5P, and 5Q exhibited the greatest number of alterations on both the cranium and the postcranial skeleton, indicating that they likely had been completely flayed. While the other complete or nearly complete individuals did not exhibit any evidence of cut marks, it is possible that they received the same treatment but showed no traces. There is strong evidence for decapitation, as in the case of individual 5M, a three-year-old child consisting of the skull and two fragments of cervical vertebral arches, with cut marks on the parietal bones indicative of scalping as well. In their study of a sample of Tollan phase burials from the Museo Jorge Acosta salvage excavations, Gómez et al. (Reference Gómez, Sansores and Fernández1994:87–91) report skulls of children recovered from the foot of an altar, with the first cervical vertebra articulated and traces of exposure to fire, although there is no mention of cut marks.

Another possible decapitate is a young adult male (individual 5R), whose remains included the skull, mandible, fragments of the second and third cervical vertebrae, and the hyoid bone. The skull has a perimortem hole in the superior part right between the coronal and sagittal suture which perhaps was used to suspend the head for display. There are also cut marks that were truncated by the hole, suggestive of scalping that would have occurred earlier (Figure 7). This individual also shows antemortem trauma to one side of the hole, reflecting exposure to violent actions when he lived. Finally, individual 5B-2, represented by the skull and mandible of a perinatal female, could have been a decapitation.

Figure 7. Skull of individual 5R: (a and b) cut marks truncated by the perimortem hole; (c) healed injury; (d) other cut mark. Photograph by author.

Associated with individual 5D was an adult ulna with cut marks at the shaft, an old fracture, major gnawing marks, and percussion pits at the distal end which were perhaps traces of cannibalism, a common practice in Mesoamerica, according to osteological studies (Lagunas and Serrano Reference Lagunas, Serrano, Litvak and Tejero1972; Medina and Sánchez Reference Medina, Sánchez, Tiesler and Cucina2007; Pijoan Reference Pijoan, Pijoan, Lizarraga and Valenzuela2010; Pijoan and Mansilla Reference Pijoan, Mansilla, Martin and Frayer1997; Tiesler Reference Tiesler, Tiesler and Cucina2007; Tiesler and Cucina Reference Tiesler and Cucina2007) and colonial accounts (Durán Reference Durán1880; Landa Reference Landa1982; Pomar Reference Pomar1821; Sahagún Reference Sahagún1829).

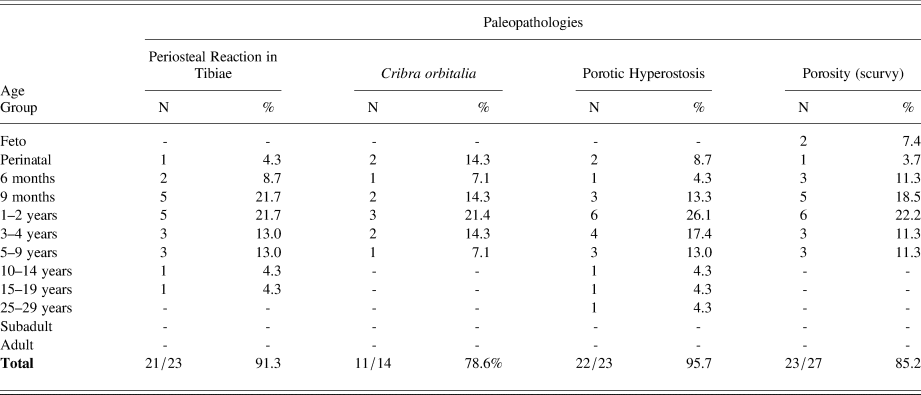

Regarding the overall health conditions of the individuals, the most common pathologies were chronic infectious processes with differing degrees of periostitis (Table 5). Almost all of the individuals in Feature 5 show periosteal lesions in the tibiae (91.3 percent) and in the rest of the skeleton as well (96.4 percent; Figure 8d). Similarly, iron deficiency is revealed by porotic hyperostosis (Figure 8b) present in 21 (95.7 percent), and less prevalent cribra orbitalia (78.6 percent, 11/14; Figure 8a).

Table 5. Paleopathologies of individuals from Feature 5.

Figure 8. Paleopathologies observed in Feature 5: (a) orbital roof of individual 5H with cribra orbitalia; (b) parietal of individual 5H with porotc hyperostosis (arrow); (c) maxilla of individual 5P with porosity (scurvy) (arrow); (d) tibia of individual 5P with periosteal reaction. Photograph by author.

In a previous osteological study of burials recovered in excavation of habitations at the Plaza Charnay and Cerro de la Malinche localities within the ancient city (González and Huicochea Reference González and Huicochea1996), evidence of infectious disease was observed in more than half of the children from Cerro de la Malinche and about three-quarters of the Plaza Charnay, in comparison to children from Feature 5, almost all of whom had periosteal reactions (91.3 percent). Moreover, only about half of the children in both of the aforementioned localities exhibited evidence of iron deficiency, unlike children from Feature 5 with high percentages (95.7 percent porotic hyperostosis and 78.6 percent cribra orbitalia). Thus, the little comparative data available for children from other archaeological contexts at Tula suggest that the children in Feature 5 had a higher incidence of health problems. Scurvy caused by deficiency of vitamin C (ascorbic acid) was also common (Table 5), given that 23 individuals (85.2 percent) showed the characteristic porosity of this disease in skull bones (Figure 8c) and mandible.

The above conditions represent the kind of precarious health conditions characteristic of famines that cause comorbid conditions (Brickley and Ives Reference Brickley and Ives2008). Regarding oral pathologies, dental caries were observed in four individuals: a two year-old (5O), two 6 year-olds (5A and 5P-1), and a young adult male (5R).

THE CHILDREN OF FEATURE 5: VICTIMS OF MASS SACRIFICE

The 21 complete or nearly complete individuals in the sample under study are primary burials that represent simultaneous deposition or deposition over a brief time. It should be remembered that mass depositions are generally considered an indicator of human sacrifice, although others have noted that these could be instead a consequence of other circumstances, such as accidents, epidemics, or the reuse of funeral spaces (Pereira Reference Pereira, Sánchez and Mata2007:92; Weiss-Krejci Reference Weiss-Krejci, Ruiz, Sosa and Ponce de León2003:373–374). However, these individuals were clearly victims of mass sacrifice, a singular event that was soon covered by construction.

The ritual violence evident in the human-induced alterations, including perimortem trauma, cut marks, and modification for display, is generally considered irrefutable evidence of sacrifice. The anthropogenic alterations discovered in the 15 primary burials in Feature 5 represent a distinctive instance of sacrifice noted by Turner and Turner (Reference Turner and Turner1999:41–42), involving inhumations in anatomical position with alterations such as fractures and cut marks, as in the present case.

Thus, the evidence suggests the individuals in Feature 5 were sacrificed, perhaps by cutting the throat, since according to the ethnohistorical sources this was the treatment for children offered to the aquatic deities by the Aztecs: “…a estos niños inocentes no les sacaban el corazón, sino degollábanlos, y envueltos en mantas” (Motolinía Reference Motolinía and Levy1967:63). The sacrifice of children by cutting the throat allowed those in charge to obtain blood that was then sprinkled on the images of the deities, the food given in the ceremonies, and in the space where sacrifices were offered (Durán Reference Durán1880:138–139, 142). Motolinía (Reference Motolinía and Levy1967:64) says that water was “sold for the blood of children.” The most common bioarchaeological indicator of cutting the throat is the presence of cut marks on the cervical vertebrae (Houston and Scherer Reference Houston, Scherer, Luján and Olivier2010:182–183; Hurtado et al. Reference Hurtado, Cetina, Tiesler, Folan, Tiesler and Cucina2007:223; Tiesler Reference Tiesler, Tiesler and Cucina2007:23–24; Tiesler and Cucina Reference Tiesler, Cucina, Luján and Olivier2010:200, 205).

Those marks were imperceptible in the children on Feature 5; it is possible that this type of child immolation has not left traces if the utensil used to cut the neck did not penetrate to the bones, as Pijoan and Mansilla (Reference Pijoan, Mansilla, Pijoan, Lizarraga and Valenzuela2010a:129) have warned. Furthermore, given that most of the children in Feature 5 were less than four years old, it was probably unnecessary to make a deep incision in the throat to cut the main arteries. Another way of executing a ritual killing of children that does not mark the skeleton is drowning, a practice also alluded to in historical sources (Codex Magliabechiano 1970:58, 88).

Sahagún (Reference Sahagún1829:bk. 1, p. 84) and Pomar (Reference Pomar1821:17) note that in ceremonies to the rain deities, child sacrifice was performed by heart extraction, for which the most common bioarchaeological evidence is cut marks on the ribs (Anda Reference Anda, Tiesler and Cucina2007:195; López Luján Reference López Luján and Olivier2010:377–379; Tiesler Reference Tiesler, Tiesler and Cucina2007:23, 25; Tiesler and Cucina Reference Tiesler, Cucina, Luján and Olivier2010:199). Two of the children from Feature 5 show evidence of this practice: individual 5H, a nine–month–old girl with one of her ribs cut on the inner face, and individual 5J-1, a nine-month-old male (see Table 4). In Unit 16, located 15 m to the northeast, a burial was recovered that was composed of two individuals: a six-month-old infant and a 1.5-year-old child. The child exhibited cut marks on the inner face of the ribs, demonstrating that immolation was by extraction of the heart, while the skull revealed evidence of exposure to fire. Associated with these two individuals was an adult skull fragment where the occiparietal section of the right side showed a cut mark and perimortem fracture, characteristic features of skulls placed on the tzompantli, or skull rack (Solari Reference Solari2008:162).

Decapitation was a common practice in Mesoamerica (e.g., Chávez et al. Reference Chávez, Robles, Aguirre and de Anda2015; González et al. Reference González, Serrano, Lagunas and Terrazas2001; Hurtado et al. Reference Hurtado, Cetina, Tiesler, Folan, Tiesler and Cucina2007; Pijoan and Mansilla Reference Pijoan and Mansilla2007, Reference Pijoan, Mansilla, Pijoan, Lizarraga and Valenzuela2010a; Román Reference Román, Luján and Olivier2010:356; Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2005). Evidence of decapitation includes skulls with the first cervical vertebra present, and the presence of cut marks or fractures (Hurtado et al. Reference Hurtado, Cetina, Tiesler, Folan, Tiesler and Cucina2007:222; Pijoan Reference Pijoan, Pijoan, Lizarraga and Valenzuela2010; Pijoan and Mansanilla Reference Pijoan, Mansilla, Pijoan, Lizarraga and Valenzuela2010a:113; Tiesler Reference Tiesler, Tiesler and Cucina2007:23, 25; Tiesler and Cucina Reference Tiesler, Cucina, Luján and Olivier2010:199). In the Feature 5 sample, individual 5B-2, a perinatal female, individual 5M, a three-year-old child, and individual 5R, an adult male, all exhibited skulls with intact cervical vertebrae, and although the poor state of preservation prevented determining whether cut marks were also present, they almost certainly represent decapitation.

To what deity were the children of Feature 5 offered? Much has been said about the relationship between children and the water divinities. Considering that Tlaloc was apparently a prominent deity in Tula, it is possible the children of Feature 5 were sacrificed to him and the other rain deities. As noted above, one of the characteristics of sacrificed children is poor health (Román Reference Román, Luján and Olivier2010), and almost all the children in Feature 5 exhibit deplorable health conditions related to infectious diseases and nutritional deficiencies, including iron and ascorbic acid. These health problems can be linked to times of scarcity caused by calamities such as prolonged droughts. These paleopathologies would have caused strong discomfort and pain, inducing continuous crying in children, which, as noted above, appears to have been a key factor in selecting children for sacrifices to the rain deities, since tears were an augury of rain (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1829:bk. 1, p. 50; Reference Sahagún1577:f. 3).

Some children of Feature 5 may have been offered to Tlaloc and perhaps the Tlaloque, recalling the myth of the ball game played between Huemac and the latter individuals, and may have been sacrificed by slitting the throat. Matos Moctezuma (Reference Matos Moctezuma, Luján and Olivier2010:55) associates this type of sacrifice with fertility, which seems quite likely given that the deities of water and fertility are intimately linked, including the maize goddesses Chicomecoatl, Xilonen, Cinteotl, and Ilamatecutli, as well as other deities including Quetzalcoatl and Xipe Totec (Broda Reference Broda1971:246, 257, 263).

A large ceramic sculpture of Xipe Totec was found buried in a neighboring residential complex (Figure 2f). Sacrifices made to Xipe Totec involved the offering of the flayed skins of captives, mainly adult males but also women and children (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1829:bk. 1, p. 58; Reference Sahagún1577:f. 18). Hence, some of the individuals in Feature 5 may have been sacrificed to this deity, especially individuals 5F, 5P, and 5Q, all of whom displayed extensive cut marks suggestive of flaying on the skeletons. Xipe Totec was associated with regeneration and was integrated into the group of water and fertility deities (Broda Reference Broda1971:256), recalling the purported origin of child sacrifice in Tula, as tlacatetehuitl, or “human strips,” that occurred during the festival dedicated to Xipe Totec (Broda Reference Broda1971:272, 275; González Reference González2016:66).

FINAL COMMENTS

Given its representation in iconography and sculpture, there can be little doubt that human sacrifice was practiced at Tula. The practice has also been inferred from cranial remains recovered from the tzompantli at Tula Grande and from burials involving children, yet without direct bioarchaeological confirmation. The children of Feature 5 in the PGR locality document the practice of ritual sacrifice in a forceful manner, as indicated by the pattern of simultaneous burial in a patterned manner and cut marks consistent with flaying, plus evidence of decapitation. It is quite possible that some individuals may have been sacrificed by slitting of the throat, despite the lack of direct evidence since, given the ages of the children, it was probably unnecessary to make an incision sufficiently deep to have left marks on the neck vertebrae. The rituals involved are believed to have been dedicated to the deities of water and fertility, although Xipe Totec also may have been involved given the proximity of a large representation of this deity and his association with regeneration.

Although I was able to address many of the questions raised by this highly unusual find, there remain several unknowns. Were these children local, that is, were they denizens of Tula or from other regions, and, if so, from where? Future DNA analysis would help answer this question, as well as confirm the sex of the individuals. This is clearly only a preliminary step in acquiring concrete data to reveal the practice of human sacrifice among the Toltecs.

RESUMEN

Durante las excavaciones de salvamento arqueológico en los límites de la poligonal de la zona arqueológica de Tula, Hidalgo, fue expuesto una complejo residencial –Elemento 5– que contiene un altar en un patio abierto, en donde fue descubierto un depósito masivo de restos óseos humanos, representando un Número Mínimo de Individuos de 49, la mayoría en posición sedente. La mayoría de los individuos son niños.

El análisis bioarqueológico apunta a que fueron sacrificados, dado que presentan modificaciones antropogénicas como marcas de corte en el cráneo y otros elementos óseos sugiriendo el desollamiento, también existen individuos representados solo por el cráneo y las vértebras cervicales aludiendo la decapitación.

Una particularidad de estos individuos es que reflejan condiciones de salud precarias, característica común entre los niños ofrendados a Tláloc entre los aztecas. De acuerdo a las fuentes etnohistóricas, los niños sacrificados a esta deidad, generalmente fueron degollados, los infantes encontrados en el Elemento 5, no presentaron huellas de corte en las vértebras cervicales por su edad temprana, pero no se descarta la posibilidad de esta forma de sacrificio.

El descubierto de una escultura de Xipe-Tótec (nuestro señor desollado) en un complejo residencial adyacente, sugiere un posible vínculo entre la inmolación infantil con esa deidad, dado que esa deidad está íntimamente relacionada con la regeneración y la fertilidad.

La hipótesis sugerida es que esos infantes fueron ofrecidos para la construcción del altar que fue erigido posteriormente a la inhumación del acumulado de restos humanos, quizá dedicado a las deidades acuáticas y de la fertilidad, incluyendo Xipe-Tótec.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This investigation would not have been possible without the support of Luis Manuel Gamboa Cabezas, Archaeologist in Charge of the Tula Archaeological Zone, who gave me access to the PGR bone collection and, in coordination with Martha García Sánchez, provided space and other necessary support for performing the analysis described in this study. I also thank Drs. Dan Healan and Robert Cobean for the opportunity to publish the results of my research in this Special Section, and my gratitude goes to Dan for comments and opinions during the preparation of this text, and the translation from Spanish. Finally, I want to thank Ancient Mesoamerica's anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments.