Studies in medieval performance, as a topic of historical research, have only been developed in recent decades.Footnote 1 Performance, understood as ‘enactment’, has multiple meanings in the study of the Middle Ages. The term today, however, mostly refers to either medieval forms of theatre, or to the ceremonies of the ordinary Christian liturgy and their symbolism.Footnote 2 In this latter area, it is notably the field of medieval architecture that has attracted substantially more academic attention from art historians. The works of specialists such as Carolyn Malone or Sheila Bonde, for instance, have consistently focused on an anthropological reading of medieval spaces as places of regular encounter and ritual significance.Footnote 3 In addition, processional sculpture with an evident performative nature, such as crucifixes, has so far also enjoyed a privileged position, particularly in well-documented contexts such as medieval Rome.Footnote 4

In stark contrast, the role of the pictorial arts has been largely neglected. Elizabeth Saxon's extensive contribution on art and the eucharist in the early Middle Ages, for instance, dealt with architectural settings, sculpture and ivory panels, processional objects such as crucifixes, and even some mosaics.Footnote 5 In the same volume, Kristen van Ausdall analysed the rituals of the eucharist in relation to the arts, and discussed in depth the roles of panel paintings, well-known fresco cycles, altarpieces, sculptured baptismal fonts and reliquaries.Footnote 6 Apart from a very short reference to the Rabbula Gospels in Saxon's contribution, illuminated manuscripts were completely absent from this seminal study. Moreover, traditional methodological approaches to medieval art history, particularly as practised in continental Europe, have tended to deny the importance of the logical synergy between art and liturgy. In overall terms, the emphasis in Continental scholarship has traditionally been on prestigious examples of high-ranking patronage and luxury artworks, certain iconographies and their evolution, and the relationships between different schools and ‘styles’. Within this academic framework, the performative use of an illuminated manuscript has perhaps been considered a de facto characteristic of an object's function that somehow belongs purely to the realm of liturgical research. This article aims to challenge that view.

The study of the symbiosis between liturgical performance and the pictorial arts of the early medieval Latin West faces a dearth of documentary evidence, which hinders research. Byzantinists enjoy the preservation of detailed ekphrastic accounts of rituals and sites, as well as abundant theological treatises that help to interpret the interaction between religious art and pious individuals in the middle and late Byzantine Empire. This rich corpus of primary sources, including authors such as St Theodore of Studios or Leo of Chalcedon, often contains detailed analyses of the symbolism of a specific icon or sculpture.Footnote 7 This is also the case for Western Europe in the late Middle Ages, particularly in the Low Countries. Authors researching this period often quote passages, not only from liturgical treatises, but also from works of devotional literature that enjoyed wide circulation and popularity at the time, such as Thomas à Kempis's De imitatio Christi. This abundance of religious literature, and also of first-hand documentation in the form of catalogues or contracts, permits the interpretation of the symbolism and reception of a wide range of iconographies. This circumstance, therefore, adds further dimensions to the study of panel paintings, altarpieces or manuscripts (such as Books of Hours for private use).Footnote 8

The contrast with the early medieval Latin West is sharp. Amidst the absence of testimonies, specialists are bound to rely exclusively upon complex liturgical treatises in which artistic media are not the focus of any detailed description, but mere agents of ritualistic practices. An example is the principal work of the ninth-century Carolingian churchman Amalarius of Metz (c. 775–850) – the Liber officialis.Footnote 9 In it, Amalarius describes with great detail the different ceremonies of the ninth-century Frankish Church and offers suggestions on how to proceed during various stages. Only the readings themselves, and not the books, are given any importance. References to crucifixes or chalices appear now and then.Footnote 10 For the early Middle Ages, therefore, it is speculation that prevails in the discussion of the dynamic and varied synergies that effectively occurred between people and books during rituals.Footnote 11 As common and necessary performative tools, medieval illuminated manuscripts enjoyed a central position in the regular interplay of Christian rites, visual culture of powerful symbolism, and its reception amongst faithful participants.Footnote 12 In order to conceive liturgical scenarios of manuscript performativity, this research will use a case study.

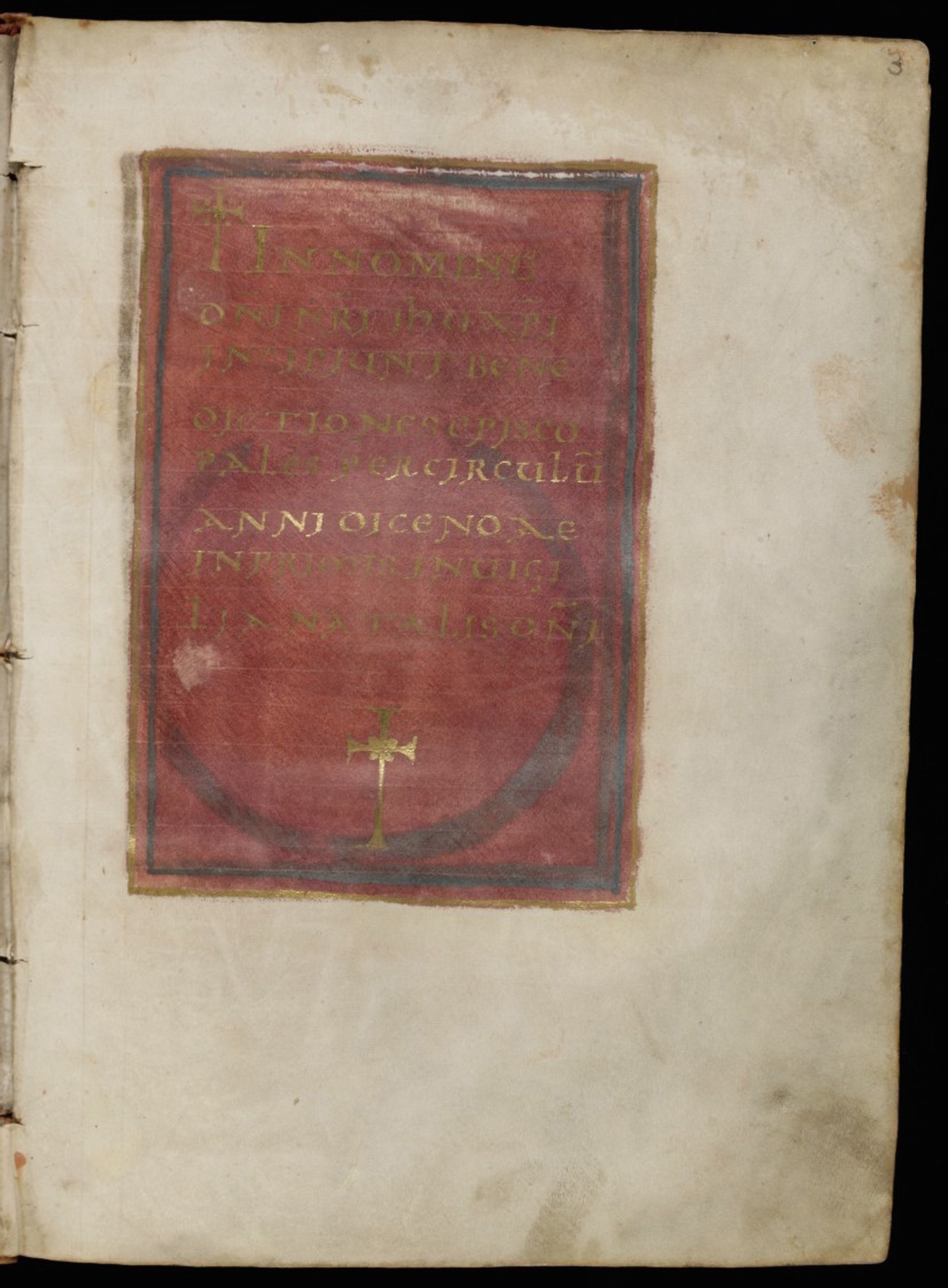

The Codex Sangallensis 398 (CS398), today preserved at the Stiftsbibliothek of St Gall, is an illuminated benedictional produced at the cathedral school of Mainz around the year 1000 and has now been entirely digitised.Footnote 13 (A benedictional is a category of liturgical book required by a bishop or an archbishop during the mass so that he can read out a wide range of public blessings oriented towards his congregation.Footnote 14 The textual content of this type of manuscript varied between sees.Footnote 15) This benedictional was created during the long tenure of the well-connected Ottonian archbishop of Mainz Willigis (975–1011).Footnote 16 This manuscript has a total length of 110 folios, each of which measures approximately 16 x 21.5 cm. After a frontispiece on folio 1r (p. 3), the verso of the same folio (p. 4) displays a framed image of Christ in Majesty – a Maiestas Domini – accompanied by the inscription Salus Mundi (Salvation of the World) (see fig. 1).Footnote 17

Figure 1. ‘Christ in majesty’, Codex Sangallensis 398, Stiftsbibliothek, St Gallen, fo. 1v, Mainz, c. 1000. Reproduced by permission of the Stiftsbibliothek, St Gallen. Photo: St Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 398, p. 4: Benedictiones Episcopales, <https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0398>.

The decoration of a benedictional with full-page scenes was rare in the early and high Middle Ages. The comprehensive and lavishly decorated Christological cycles of the contemporary Anglo-Saxon Benedictional of St Æthelwold, the Regensburg Benedictional of Engilmar of Parenzo, or a Lorsch pontifical now in Paris are notable exceptions.Footnote 18 The Mainz benedictional displays instead only one scene, together with scattered gilded initials throughout. Unlike its contemporaries, the apparent simplicity of the Mainz manuscript's decoration perhaps implied a more regular use as liturgical book. Its luxurious and delicate Anglo-Saxon counterpart was likely conceived instead as a precious gift and future ex-voto, only to be handled and showcased perhaps during a handful of feasts and special ceremonies.

The initial focus of this research is on the symbolism and message that this decorated manuscript transmitted to an audience when folios 1v–2r were shown. In the field of art history, illuminated manuscripts such as this benedictional have not attracted enough interest from scholars, traditionally more interested in iconographic particularities or cohesive narrative cycles that can be related to other artworks elsewhere. The role of the bishop and the general performative use of a benedictional will also be analysed. In this regard, the manuscript's list of episcopal blessings (an edited version of which can be found in the Appendix below), contemporary liturgical sources and depictions of ceremonies in other illuminated manuscripts, will serve to illustrate the handling and showcasing of benedictionals in ninth-, tenth- and eleventh-century Europe. The history of Willigis's tenure at Mainz, as well as general aspects of the liturgy in the Carolingian and Ottonian periods, are sufficiently well known. This will facilitate to a considerable extent the final task, that of reconstructing eucharistic ceremonies in Mainz around the year 1000 and the role that this illuminated benedictional in particular played in them.

The agency of the Christ in Majesty

The blessing Maiestas Domini appears on folio 1v (p. 4) of the manuscript. The figure is depicted within a frame composed of yellowish and black borders, over a background of a standardised Carolingian and Ottonian maroon. The representation of Christ does not occupy the whole of the page. It appears alone, over the parchment, and was large enough to be easily perceived by the viewer at some distance when the manuscript was fully open. Flanking the portrait of Christ, the observer also distinguishes the gilding of the letters: Sa/lus Mu/ndi.

The creation of this inscription is not arbitrary. The previous page, folio 1r (p. 3), carries the title assigned to the manuscript's content (‘Benedictiones episcopalis per circulu[m] anni’) and the heading of the first blessing (‘In vigilia natalis D[omi]ni’), that is, Christmas Eve (see fig. 2). The image of Christ in Majesty on the following folio must be visually paired with its opposite page, folio 2r (p. 5), where the blessing that the bishop pronounced on that day continues (see fig. 3). The benedictional's set of blessings begins, therefore, with the liturgical celebrations of Christ's birth. Describing the episode, Matthew i.21 (KJV) runs: ‘And she shall bring forth a son, and thou shalt call his name Jesus: for he shall save his people from their sins.’Footnote 19 On this occasion, this Maiestas comes to embody the idea of human salvation which is at the core of Christian theology and will culminate in the Second Coming of Christ and the Last Judgement. Describing it, St Matthew wrote: ‘When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on his glorious throne.’Footnote 20 The Mainz illuminators, heavily influenced by this Apocalyptic concept, created an image of a seated Christ in Majesty that represented the beginning of the annual set of blessings. The first set of celebrations in this corpus commemorated in fact Christ's First Coming and the beginning of the redemptive process – Christmas.

Figure 2. Title and first heading of the ‘Benedictiones episcopalis’, Codex Sangallensis 398, fo. 1r. Photo: St Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 398, p. 3: Benedictiones Episcopales (https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0398).

Figure 3. Codex Sangallensis 398, fo. 2r. Photo: St Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 398, p. 5: Benedictiones Episcopales (https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0398).

The figure of Christ appears over a pedestal. But, although he is seemingly seated, there is no actual throne.Footnote 21 Christ was initially drawn with a black pen outline, the tunic later being coloured with the same maroon seen in the background and frame, whereas the long chlamys is light blue, later retouched with white, resulting in a well-executed light and shade effect. As in other versions of this iconography, Christ holds a closed book, probably alluding to the seven-sealed liber mentioned in the Book of Revelation.Footnote 22 With his right arm Christ makes a sign of blessing to the viewer with three fingers representing the doctrine of the Trinity. The face is somewhat rough, mainly because of the eyes. A gilded, cruciform aureole frames Christ's head.

Iconographic models of the enthroned Christ are found in numerous examples of other types of decorated manuscripts, particularly in illuminated copies of the Gospels in both the Carolingian and Ottonian periods. In the ninth century a similar representation of Christ, in a mandorla and surrounded by the Tetramorph, the Evangelists and four Prophets appears as the frontispiece to the New Testament section of the First Bible of Emperor Charles the Bald (the Vivien Bible), made at Tours.Footnote 23 In the German tenth century, a similar scene of great complexity was conceived as the frontispiece of the Sainte Chapelle Gospels. This manuscript was likely commissioned by the well-known patron of the arts, Egbert, archbishop of Trier (977–93), at either Reichenau or Echternach.Footnote 24 It is worth remarking that this Maiestas image appears on folio 1v of the Sainte Chapelle Gospels – the same position that it occupies in Codex Sangallensis 398. However, as Rudolf Lauer remarks, the most direct parallel to the Christ in Majesty of CS398 was also created at Mainz around the same time.Footnote 25 Now in Munich, the Prayerbook of Otto iii (996–1002) was either commissioned by him, or was a gift from Archbishop Willigis to the young prince.Footnote 26 Folios 20v–21r display a double scene. The young Otto, on the left, appears prostrated and facing a very similar Maiestas to that of the CS398 on the right-hand page (see fig. 4). This time however, Christ's throne is being carried in the air by two angels, thus mirroring with greater accuracy the vision described in Matthew xxv.31.

Figure 4. ‘Christ in Majesty’, Prayerbook of Otto iii, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Clm 30111, fo. 21r, Mainz, c. 1000. Reproduced by permission of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich; photo: BS Munich.

Only three uses of this iconography are known in illuminated benedictionals. The aforementioned Benedictional of St Æthelwold depicts in fact not one, but two images of Christ performing a blessing gesture.Footnote 27 The first appears on folio 70r – a depiction of an enthroned Christ inside a double, gilded mandorla and above the title of a blessing related to the Trinity dogma. The second image of a blessing Christ is a two-thirds length depiction within another golden mandorla on folio 91r. This image appears framed by a sumptuous vegetal frieze, characteristic of the Winchester scriptorium at the time. Yet, these are relatively small portraits of Christ that, unlike the Mainz manuscript, do not represent the main visual element of the page, and remain complementary decorations to a textual marker.

A third and final example of this category of book displaying a Maiestas Domini was created at Lorsch in the second half of the eleventh century. Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris, ms 2657 is a manuscript that contains the benedictiones pontificales, that is, a set of blessings for rites exclusively performed by a bishop outside the regular eucharistic services.Footnote 28 Folio 1v of this manuscript displays a framed, full-page enthroned Christ in Majesty accompanied by the symbols of the four Evangelists and, on the opposite page, the depiction of two saints (see fig. 5). Although the inscriptions are missing, these are likely the portraits of St Peter and St Paul, to whom the Lorsch abbey church had been consecrated in the eighth century.Footnote 29 The positioning of these two portraits on the opposite page to the Maiestas may indicate that the Lorsch artists intended to highlight the intercessory roles of both St Peter and St Paul at the Last Judgement, the episode to which the Maiestas iconography on the opposite page alluded.

Figure 5. ‘Christ in Majesty, St Paul and St Peter’, Lorsch benedictional, fos 1v–2r, Bibliothèque Sainte Geneviève, Paris, Lorsch, c. 1075. Reproduced by permission of the Bibliothèque Sainte Geneviève, Service de manuscrits; photo: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Handschriftenabteilung/ Bibliothèque Sainte Geneviève, Paris, Service de manuscrits.

Since the decoration of a benedictional was rare in tenth- and eleventh-century Europe, the Lorsch and Mainz scriptoria freely created different, albeit valid models of text-image symbolism that exerted a powerful effect on their manuscripts’ audiences. Whereas the Lorsch artists opted for a double scene with Christ and St Peter and St Paul, the message of eventual redemption stressed in the visuality of the Mainz benedictional stemmed from the interplay between the inscription Salus Mundi, attached to the representation of an Apocalyptic Maiestas, and the textual beginning of the Christmas celebrations that marked the First Coming of Christ. In the depictions of Christ in Majesty in both benedictionals the figure performed the same gesture, a blessing oriented towards their potential audiences. This is precisely the same gesture that Archbishop Willigis performed during the eucharistic services for which the Mainz benedictional was first and primarily conceived.

The bishop's manuscript: representation and authority

‘Custodiebat, custos erat, vigilabat, quantum poterat, super eos quibus praeerat; – et episcopi hoc faciunt. Nam ideo alterior locus positus est episcopis, ut ipsi superintendant et tamquam custodiant populum’.Footnote 30

Beyond the awe-inspiring agency of the manuscript's Maiestas, the Mainz benedictional and its decoration also established a symbolic and personal association with the figure of its owner and patron, Archbishop Willigis, in a wide variety of contexts. The image of the blessing Christ in Majesty found, in this manner, a direct correlation in terms of gestures that, being part of predefined rites, a bishop or an archbishop regularly performed in public.Footnote 31 This imitatio, or intentional and meaningful replication by the pious churchman, had Christ as the ideal model. It does, moreover, add a further layer of symbolism to the action, since these blessings were performed in public, oriented towards a vast congregation of presumably fearful and pious churchgoers who also expected to behold the same gesture during the Last Judgement. By depicting this iconography on the manuscript, the Mainz archbishop, therefore, expressed a clear will to associate his image with that of the enthroned Christ.Footnote 32

In early medieval times the bishop was widely considered to be a representative of God on earth.Footnote 33 After the fall of the Roman Empire, primates became in many cases the only remaining urban auctoritas in the West – a political reference in the administration of cities across Europe, amidst the collapsing social structures of the former Roman authority and the absence of local or regional political leadership.Footnote 34 In the central centuries of the medieval millennium, after the consolidation of a powerful royal dynasty such as the Ottonians, the bishop fiercely defended his ancient status of civil authority and political reference. There was continuous interference and disregard by regional nobilities and, sometimes, by zealously independent monastic houses as well.Footnote 35 At that time, the strong role of the bishop in the Oecumene's life found a vigorous defender in the Anglo-Saxon Wulfstan, archbishop of York between 1002 and 1023.Footnote 36 In his diverse written oeuvre, particularly his homilies and letters, Wulfstan repeatedly stated that bishops should play a more active role in the life of laymen.Footnote 37 They were part, as local or regional representatives, of what Tertullian once defined as the vicarii Christi.Footnote 38 This concept implied the use on earth, in his absence, of Christ's power, channelled through the Holy Spirit, and granting his vicar unparalleled and uncontested authority.Footnote 39 Throughout the Middle Ages, however, divergent interpretations of this idea and the balance of power between the ecclesiastical and lay worlds led on several occasions to acrimonious conflict. At the core of the investiture controversy for instance, lay the expanding ambitions of Henry iv as Holy Roman Emperor and the strong opposition orchestrated by the influential papacy of Gregory vii and its allies.Footnote 40

Nevertheless, in the daily life of many medieval cities, the bishop was still the leader of the local population. Liturgy, therefore, was not only a regular set of religious services, but also a public and continuing display of the bishop's authority. Besides the eucharistic rites that occurred inside the walls of the cathedral, perception of the bishop's power and leadership at the local level increased during extraordinary events, such as a synod or a king's coronation, as well as during public events, such as the adventus of a particularly venerated relic, or the annual Palm Sunday procession. Willing to assert themselves and to advance their careers, the bishops took these occasions very seriously. In many cases manuscripts and their contents were key devices in these liturgical displays of power and authority.

Soon after 1024 the newly appointed prelate of the north-western German city of Minden, Sigebert (1022–36), commissioned a total of seven liturgical manuscripts from the Abbey of St Gall, including a monumental and richly illuminated sacramentary.Footnote 41 The reason behind this comprehensive and anomalous request to a scriptorium was the celebration of a Reichstag, or Imperial Diet. This gathering was to be held at Minden in 1030 and to be chaired by the new Salian king and close acquaintance of Sigebert, Conrad ii. Through art patronage, Sigebert intended not only to perform the necessary rites before, during and after the proceedings of the Diet, but also to impress the audience of influential churchmen, high-ranking officials and the Salian king himself. This symbiosis of civil and ecclesiastical power was also particularly visible during the coronation of a new monarch. The Anglo-Saxon bishop of London, Wulfstan (d. 1023), also wrote about these episodes.Footnote 42 In these special ceremonies, the English cleric wrote, the bishop acted as a mediator, transmitting Christ's authority (and therefore his legitimacy) to the now officially acknowledged ruler. This was particularly true in the case of Archbishop Willigis at Mainz, as his biography and the contents of CS398 attest.

Both the regular eucharistic services, such as Sunday mass, and extraordinary or annual events, such as the coronation of a new king, the consecration of a church, the dies natalis of a popular local saint or the Easter celebrations, witnessed a high level of participation by the population. In early medieval Europe, public liturgies of different kinds came gradually to define the character of entire towns across the medieval West, as they still do nowadays, conferring a distinctive community identity. At the centre of public rites and meaningful processions, consolidating both the collective and the individual sense of belonging of the masses, the leading role was that of the local bishop.Footnote 43

In this regard, benedictionals like CS398, as portable manuscripts, are known to have been shown and paraded during both regular and extraordinary liturgical moments across Western Christendom. Yet little attention has been paid to the performative function of illuminated manuscripts, especially compared to processional objects like crucifixes that were often solemnly handled, showcased and even kissed.Footnote 44

The benedictional and its use: liturgy as public performance

The bishop recited the blessings contained in a benedictional at a precise moment during the ordinary eucharistic services held daily and during the masses of specific feasts – after the Pater Noster and immediately before communion.Footnote 45 These blessings are evocative short passages of approximately fifty words each, the texts of some of those for the most important feasts being symbolically longer (the eve of Christmas or Pentecost, for instance).Footnote 46 Besides the standardised feasts of the liturgical calendar, other occasions, such as the consecration of a new church, were also included. Decisions as to which masses were said varied substantially from see to see, resulting in the wide range of benedictional texts that has come down to the present day.Footnote 47 Geographical differences abound, even in relatively reduced regional contexts, puzzling modern specialists. In early medieval Europe, two main versions of benedictionals existed – the ‘Gallican’ and the ‘Gregorian’.Footnote 48 The former was highly influential and indigenous to pre-Carolingian north-western Europe and Iberia. The latter derived from the list of pre-communion blessings compiled by St Benedict of Aniane, later being sponsored by Aachen in order to standardise the liturgical practices of the expanding Frankish realm.Footnote 49 After the ninth century, scriptoria freely combined elements from both traditions, adding their own particularities as well.Footnote 50

Codex Sangallensis 398 contains a triple set of blessings. These are three separate and consecutive lists of blessings of different lengths, created in order to offer to the officiant alternative versions to read at some of the major feasts.Footnote 51 These options were either drawn from Gallican or Gregorian materials, or devised in situ. As a result, a scriptorium would create its own unique version of the benedictional. In the form of this three-fold composition, the Mainz scribes ascribed special relevance, for instance, to the eve of Pentecost's Eve, Pentecost and the further remembrance services held once a week for the twenty-three weeks following.Footnote 52 During the Easter ceremonies, similar blessings could be heard.Footnote 53 At local level, specific saints that enjoyed a particular veneration in the diocese were also remembered and their protection and blessing requested super populum. In the Benedictional of St Æthelwold, for instance, the feasts of two popular Anglo-Saxon saints, St Swithun and St Ætheldreda, were included.Footnote 54 In CS398, the blessing to be recited during the mass in honour of the patron saint of Mainz, St Martin, appears on folio 78r–v (pp. 155–6). St Stephen, a figure particularly venerated in Mainz, was commemorated with two different blessings, on folios 4v–5r (pp. 9–10) and 35v–66r (pp. 71–2). The dies natalis of St Innocent also included two different blessings, on folios 6r–v (pp. 11–12) and 37r–v (pp. 73–4). St Innocent's importance rests on the presence of some of his relics in the nearby nunnery of Gandersheim, an institution under the influence of Mainz and over which the bishop of Hildesheim tried to establish a claim at the turn of the new millennium.Footnote 55 Paramount episodes in the life of the Virgin Mary, such as her natale or her Assumption, were also celebrated, thus highlighting the growing importance of Marian feasts in Ottonian Germany.Footnote 56

During the celebration of the eucharist in all those services, the benedictional was paraded and showcased, not necessarily by the primate himself, but by an assistant, likely a deacon. A depiction of such a practice is offered by the detached leaf from the Pericopes book of Bishop Sigebert of Minden, produced at St Gall in the period c. 1025–30 (see fig. 6).Footnote 57 This book was one of the seven liturgical books commissioned by the newly appointed bishop from the Alpine Reichsabtei before the Imperial Diet at his see in 1030. In this image, Sigebert appears seated on his cathedra, flanked by a Minden priest and a deacon. To Sigebert's left, the deacon stares at him whilst holding a liturgical book open. Similar interactions between the manuscript and its audience, rather static as this portrait demonstrates, are also conceivable on a regular basis in the case of the Mainz benedictional. In this regard, the so-called ‘Solemn High Mass’ is a service led by a priest, but held in the presence of the local bishop, seated on his cathedra.Footnote 58 This is probably the moment that the St Gall Pericopes portrays. Unfortunately, the types of manuscript showcased in the Minden Pericopes leaf remain a mystery.

Figure 6. Bishop Sigebert of Minden, together with a priest and a deacon: detached folio from the Sigebert Pericopes, Stiftung Preußisches Kulturbesitz, Berlin, ms Theo. lat. qu. 3, St Gall, c. 1025. Reproduced by permission of the Stiftung Preußisches Kulturbesitz, Handschriftenabteilung, Berlin; photo: Stiftung Preußisches Kulturbesitz, Berlin.

None the less, it is the dynamic rituals of the regular processions which took place inside the cathedral and outside the walls of the building that the modern viewer needs primarily to consider in order to approach the performativity of Codex Sangallensis 398 and the visual reception of its Maiestas Domini. First and foremost, the sung prayers of the Introit marked the ‘entrance’ of the bishop in order to start the mass.Footnote 59 Here previously neglected correlations between the iconographies of the sculptured portals in twelfth-century buildings and specific introits are revealed. Margot Fassler, studying this synergy at Chartres, indicated that some of the themes represented in the cathedral's portals found textual counterparts in the tropes of the preserved Chartres introits.Footnote 60 The Nativity introit trope, for instance, celebrated ‘the King's descent to Earth’ and described ‘the throne of His kingdom’, likely alluding to two of the building's carved Maiestates.Footnote 61

This direct correlation between visual culture and liturgical text may be evident at Mainz as well. BL, ms Add. 19768 is a manuscript containing diverse antiphons and tropes composed at Mainz during Willigis's tenure of the see.Footnote 62 The Nativity trope begins: ‘Today the Saviour of the World was deemed worthy to be born of a virgin’ / ‘From Heaven God gave us his only begotten son’.Footnote 63 The Maiestas Domini of CS398, and its Salus Mundi, highlighted the future redeeming nature of Christ's birth, and preceded the beginning of the blessings of Christmas Eve. Willigis and the creators of the benedictional perhaps had in mind these symbolic correlations between liturgical word and image when the benedictional's Maiestas was depicted. In that case, the book was likely paraded open during the Christmas introits, recreating the vision narrated in the trope. It is finally worth adding that a renovation that Mainz Cathedral underwent around the year 1200 witnessed the creation of a carved tympanum at one of its entries depicting an enthroned blessing Maiestas carried in the air by two angels.

The so-called ‘offertory procession’ was probably another stage when the Mainz benedictional might have been used.Footnote 64 This small procession, sometimes led by priests and deacons or members of the congregation, carried the host and the wine from the sacristy to the altar, together with other devotional objects and liturgical instruments. These included, for instance, a portable cross to be placed over the altar, or, in the case of Mainz around the year 1000, perhaps Codex Sangallensis 398. The Pontificale Romano-Germanicum, a compound of liturgical indications compiled in Mainz under Archbishop Willigis, is an invaluable source for the liturgical history of the period. It states that Gospel books were normally paraded by one of the acolytes during the ‘offertory procession’.Footnote 65 As previously argued, the illumination of Gospel books in Germany around the year 1000 included an almost standardised representation of the Maiestas Domini as a frontispiece. In the case of a large diocese, such as Mainz, the option of a similar parading and showcasing of a benedictional by one of the many deacons that the cathedral had at its disposal is certainly plausible.Footnote 66

A similar offertory procession occurred during the eucharist of the Exaltation or Feast of the Cross, celebrated on 14 September, whose blessing is displayed on folios 19r–v (pp. 37–8) as ‘In festivitate s(anctae) crucis’ in the Mainz benedictional.Footnote 67 Led by the bishop himself, a priest or deacon also held a crux, a crucifix that was eventually placed over the altar. The eucharistic tools, the host and the wine, accompanied the deposition of the cross, together with the books that were necessary for saying the mass that began immediately afterwards, likely including this benedictional as well. In the case of the Exaltatio Crucis, or any other eucharistic services in which one of the bishop's assistants carried a portable cross, the image in the Mainz benedictional complemented the probable simplicity of a wooden or metallic cross not necessarily displaying a Christ on it.Footnote 68 On its way to the altar, the image could be seen easily by those attending the mass, located in close proximity on both sides of the central aisle which divided the congregation in many buildings such as Mainz Cathedral. The salvific purpose of the liturgy, the image showcased and the text recited by the bishop, contributed to a multi-sensorial performance, a solemn and inspiring experience for the entire congregation.Footnote 69

Another important festivity during which the benedictional would certainly have been handled was the Palm Sunday procession that re-enacts Christ's entry into Jerusalem a week before Easter Sunday.Footnote 70 A substantial number of records from the Middle Ages about this ceremony describe vibrant moments of civic religion, accompanied by gestures, prayers and chants. In many cases, weather permitting, the procession began outside the walls of a city, always led by the bishop, followed by priests, deacons and other lesser members of the local church hierarchy. The procession stopped at the entrance to the cathedral and a mass was held inside, or sometimes outdoors.Footnote 71 The Palm Sunday blessing of the Mainz benedictional starts on folio 11v (p. 22) and ends on the following page. According to the text, the bishop referred to the crowd, who held the palm fronds (‘concedatque vobis ut sicut ei cum ramis palmarum’). Another paragraph begins with the expression ‘Benedicat vobis omnipotens Deus’. In the absence of mural figurative representations, the effect of the omnipresence of Christ's gaze and judgement could not be better achieved than by showcasing an image of the Maiestas Domini as the procession moved through the city's streets.Footnote 72 The figure of Christ performed in advance the same meaningful gesture that the bishop would later make during the mass. On that occasion, the deacon certainly paraded the book either closed or open at its first page. Most of the weight of the object probably rested over the deacon's left arm while walking. The book's front cover, therefore, was easily held open with the right hand and the iconography on folio 1v displayed.

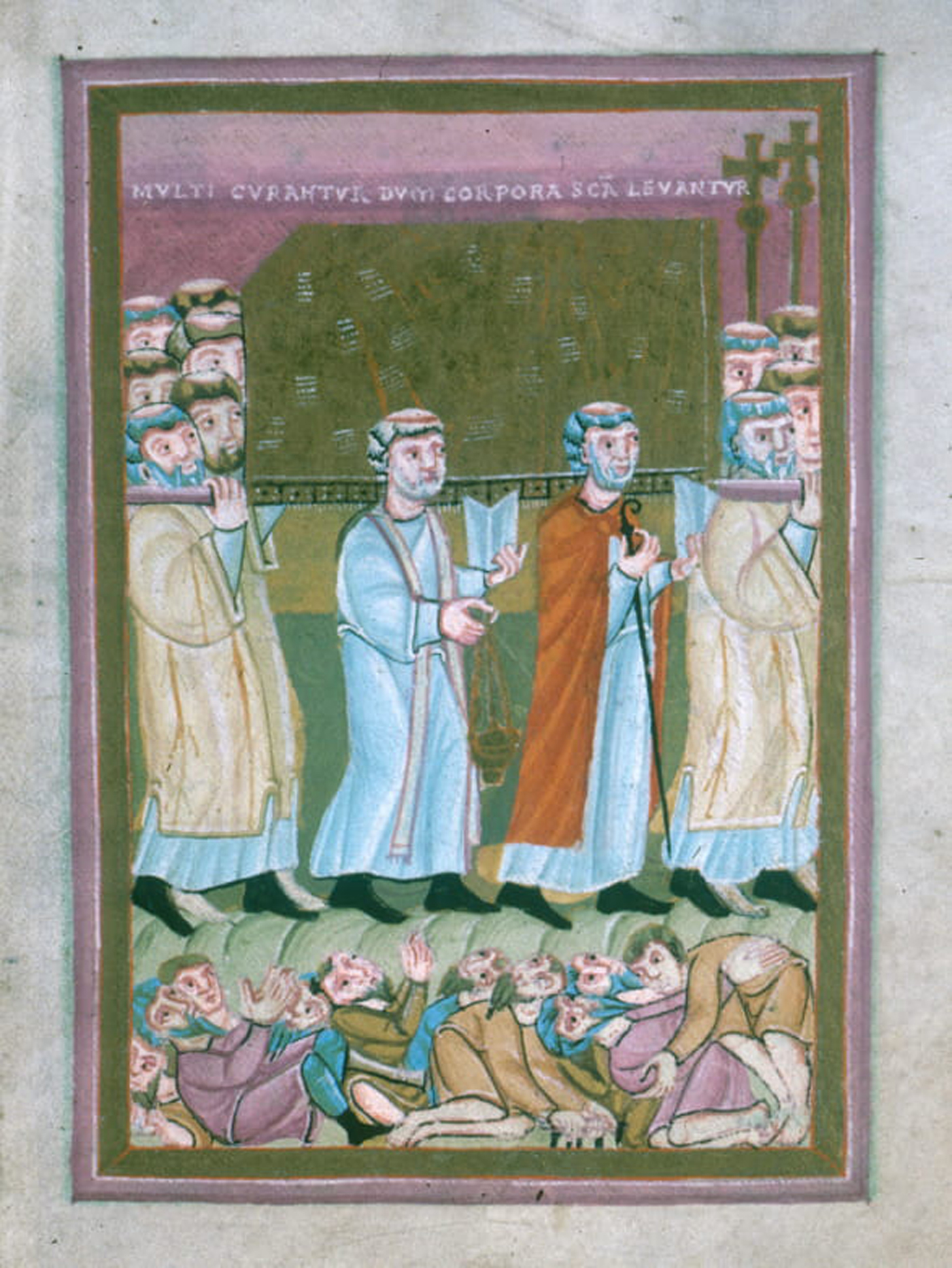

The argument that manuscripts were displayed during liturgical processions is supported by a number of Carolingian, late tenth- and eleventh-century images. A peculiar scene is found in a Gospel-Pericopes book, created at Echternach around the year 1040. Folio 160r of this luxury manuscript, now in Brussels, depicts an early eleventh-century procession, the annual parading of a relic of St Stephen (see fig. 7).Footnote 73 A number of clerics surround and accompany the the relic (which is seemingly inside a large casket).Footnote 74 The inscription above the image refers to the healing of the local sick shown in the lower level of the image. Two of the tonsured clerics each hold open a manuscript with their respective right hands. The one with the thurible is a priest, whereas the other figure, wearing a cap and carrying a crosier, is evidently a bishop. The latter perhaps carries with him a gradual or an Ordo Missae, which contains prayers to be recited out loud. The former may have been carrying a benedictional, whose text was not necessary during the procession. Yet, both books were open and their interiors on view.

Figure 7. Procession of St Stephen's relic, Echternach Periscopes, Bibliothèque royal de la Belgique, Brussels, ms 9428, fo. 160r, Echternach, c. 1040. © Bibliothèque royal de la Belgique, Service des manuscripts.

This scene indicates that liturgical books were paraded by the bishop and his assistants during public processions in early eleventh-century Germany. The priest himself, or a deacon, would have later assisted the bishop during the mass, holding the benedictional open to facilitate his task. This is the precise moment captured by a scene in the Marmoutier Sacramentary, created around the year 850 at the eponymous abbey of Tours (fo. 173v) (see fig. 8).Footnote 75 The bishop was depicted holding a crosier, standing on a pedestal bearing his name, reminiscent of a pulpit. He appears to be blessing the assembly gathered before him, as the inscription above reads: ‘Hic benedic(ere) populu(m)’. As Voyer remarked, the stooping figure carrying a manuscript open on his back was the officiant's assistant, a deacon, and the manuscript in question an independent benedictional or a sacramentary containing an equivalent list of blessings.Footnote 76

Figure 8. Bishop blessing the congregation, Marmoutier Sacramentary, Bibliothèque municipale, Autun, ms19bis, fo. 173v, Tours, c. 850. Reproduced by permission of the Bibliothèque municipale, Autun; photo: cliché IRHT.

A third and final glimpse into tenth- and eleventh-century manuscript handling and the display of manuscripts during a liturgical performance is offered by one of the sketches in the Lanalet Pontifical, a late Anglo-Saxon manuscript from Cornwall that depicts the consecration of a church(see fig. 9).Footnote 77 Folio 2v of this manuscript, now in Normandy, is illustrated with the only known representation of this ceremony from this period. A bishop, perhaps Buhrweald (c. 1002–19), is shown touching his crosier to the doors of the newly inaugurated church.Footnote 78 A group of lesser clergy stands behind him. A priest, who seemingly leads the group, holds a manuscript, this time closed. The scene likely represented the aftermath of the reading of the blessing, when the bishop performed a very precise dynamic ritual of consecration. Yet the manuscript was depicted as a paramount tool in the entire outdoor rite. A crowd of spectators, likely including the masons and other workers, as well as the local population, witness the performative ritual. In the Mainz benedictional, the blessing for this particular ceremony is displayed on folios 106v–107r (pp. 212–13: ‘In dedicatione aeccl(esi)ae’).Footnote 79

Figure 9. Bishop consecrating a church, from the Lanalet Pontifical, Bibliothèque municipale, Rouen, ms 27, fo. 2v, Cornwall, c. 1000. Reproduced by permission of the Bibliothèque municipale, Rouen, ms 27; photo: cliché IRHT.

In the case of the Echternach Book of Pericopes, the modern viewer can only speculate about the type of manuscripts that were being handled by bishop and priest. It is clear, however, that benedictionals were paraded in Carolingian and Ottonian times. Priests, and especially deacons, played a major role, normally holding and carrying the necessary liturgical tools. It is now time to analyse in depth when and how CS398 might have been used in a specific historical context. The diocese of Mainz under Archbishop Willigis (975–1011) has been extensively studied by modern scholarship and offers a myriad of documented scenarios when the benedictional was probably handled.

A setting: Mainz under Archbishop Willigis, c. 1000

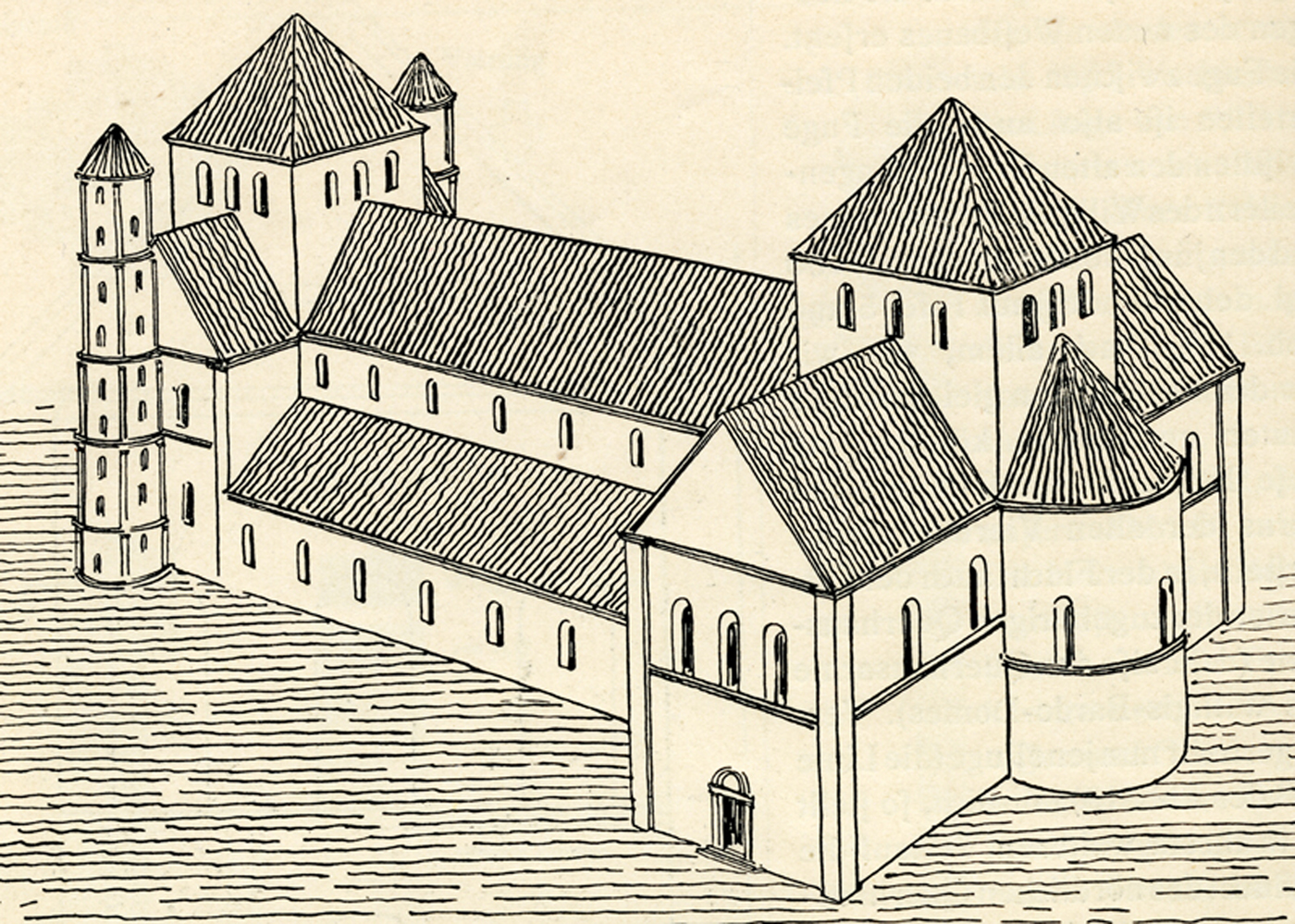

Even though the previous examples of liturgical performances certainly occurred in a variety of geographical contexts, Codex Sangallensis 398 contains blessings for services held during the lifetime of Archbishop Willigis in the city of Mainz and at which Willigis's presence was required. The figure of this bishop defined the history of both the city and its diocese around the turn of the eleventh century.Footnote 80 Thietmar of Merseburg reported that Willigis was a person of very humble origins.Footnote 81 After becoming a cleric, he soon came to the notice of higher officials, being appointed chancellor to Otto ii in 971. A few years later, in 975, Willigis became archbishop of Mainz and arch-chancellor of the Empire, the highest political office under the auspices of the Ottonian monarchs.Footnote 82 During his tenure, Willigis's plans for the city involved ambitious urban planning, mainly focused on church building.Footnote 83 The cathedral of St Martin experienced a major enlargement, resulting, not without trouble, in today's Romanesque building (see fig. 10).Footnote 84 A late Roman or Frankish structure likely existed before, although its dating and original aspect are unclear. Around the year 980 Willigis decided to enlarge the building, but it is impossible to ascertain whether eucharistic services and other liturgical gatherings were held inside the original, early medieval building for the duration of the works that culminated in 1009. Sadly, a fire broke out on the very day of the cathedral's inauguration, devastating large parts of the complex. The large abbey church of St Albans, home to the relics of the earliest Mainz saint, acted after that event as the city's cathedral.Footnote 85

Figure 10. Model of Mainz Cathedral before Willigis's intervention, reproduced from Rudolf Kautsch, Der Dom zu Mainz, i, Darmstadt, 1919, 38.

In order to explore the use of CS398, a pertinent question is, therefore, its dating. Since the different lists of blessings do not contain an individual passage related to St Albans, it is reasonable to believe that the benedictional now at St Gall was commissioned as a liturgical book to be used in St Martin's Cathedral. The commission and subsequent use of CS398 perhaps occurred within the walls of the previous building soon after 975 or during its enlargement over the following decades. A third option is to consider the manuscript as a future liturgical tool for use in the services to be held after the inauguration of the new building in 1009. As it was a basilica – as were most churches in Mainz at this time – it is easy to conceive of regular processional entries, from the sacristy on one of the sides or from the main gate, through the central apse, to the main altar, at least in the case of introit or ‘offertory’ processions.Footnote 86 The benedictional was likely one of the objects displayed by the group of deacons holding books and other liturgical and processional objects, such as banners or a portable cross, who stood in the altar area, facing the crowd that gathered mostly in the central nave and under the arches. In the hypothetical case of being carried open during the entry procession, the manuscript's image, although of secondary importance in relation to the figure of the bishop that led the group, also represented the entry of an imago of Christ into the Sancta sanctorum that the area around the altar symbolised.Footnote 87 The presence and showcasing of other illuminated liturgical books depicting the Maiestas Domini (such as the Gospels that the Pontificale Romano-Germanicum mentioned) remains an open question.

An almost certain setting for the handling and showcasing of Codex Sangallensis 398 was the church of St Stephen, promoted and inaugurated by Willigis in 990 and the beneficiary of an endowment offered by Emperor Otto ii’s wife, the Greek princess Theophanu.Footnote 88 This building, Willigis's second most important architectural initiative, is a three-aisle basilica with a developed Westwerk.Footnote 89 The edifice likely hosted the celebrations of the saint's dies natalis on 26 December. Two different commemorative blessings composed for the mass said on that day, are displayed on folios 5r–v (pp. 9–10) and 36r–v (pp. 71–2) of the benedictional. On the other hand, if produced before 990, Willigis’s benedictional might well have been used for the actual consecration of the church. This service involved a series of liturgical performances outside and inside the building.Footnote 90 Two different blessings to be recited by the primate during the mass on such an occasion appear on folios 31v and 32r (pp. 62–3). In case of a later date, Willigis and his subordinates likely used Codex Sangallensis 398 in the liturgical service that commemorated the anniversary of the consecration of a church, a blessing for which is written on folios 32r and 32v (pp. 63–4) – ‘[Benedictio] in anniv(er)saria dedic(atione) eccle(siae)’.

Codex Sangallensis 398 also contains other blessings that probably reflect its potential use in late tenth- and, early eleventh-century Mainz. Folios 11v–12r (pp. 22–3), and 50r–v (pp. 99–100) contain two blessings read out by Willigis during the mass of Palm Sunday. This service was normally preceded by a solemn procession intended to re-enact Christ's entry into Jerusalem.Footnote 91 Led by the archbishop himself, this began at one of the gates of the city. The Roman Mogontiacum, the original settlement of Mainz, had probably boasted solid stone walls since the early first century.Footnote 92 These were reinforced in the fourth century with the widening of the precinct and the creation of several gates, such as the so-called Kästrich entrance, near St Stephen's church. Another gate stood to the south of the city, near the Roman theatre. This entrance later gave way to the Neutorstraße, which enlarged the path from Mainz's southern extra moenia to the cathedral. This second option remains the most likely setting for an outdoor re-enactment of the entry into Jerusalem by Archbishop Willigis. To the otherwise symbolic east of the city was the harbour on the Rhine which still dominates the landscape of the Rhineland's historical capital.

Archbishop Willigis was an extraordinary priest of great ambition. With the commission of the benedictional now at St Gall, he certainly intended to provide his see with a brand-new liturgical instrument for regular use. Willigis has been primarily studied by modern art historical scholarship as the driving force behind the construction of St Stephen's church and, most notably, the enlargement of St Martin's cathedral, one of the pioneering structures of the Romanesque in Germany. The intentions of the primate for his city were not restricted to the creation or enlargement of buildings, but also encompassed the progressive renovation of the modern city's Altstadt, mirroring Rome as its ideal model.Footnote 93

Codex Sangallensis 398 can also offer to the modern viewer a glimpse into the aspirations and future projects of this archbishop. Folios 30v and 31r–v (pp. 60–2) of the manuscript contain the blessing that was to be recited ‘super rege(m) … te(m)p(o)r(e) synodi’ – a hypothetical synod of the German primates chaired by an Ottonian monarch. Such a gathering would probably have been hosted at the new cathedral, after the building work was completed, or alternatively, at St Albans. As a matter of fact, in 952 a synod had been summoned by Otto i at Augsburg and its ceremonies led by the then archbishop of Mainz, Frederick (937–54).Footnote 94 Two years later, Frederick organised a minor gathering at Mainz.Footnote 95 Perhaps Willigis expected similar occasions to occur during his tenure, at Mainz or elsewhere.

An archbishop's personal relationship with the monarch was pivotal in these sorts of decisions. Otto i had been crowned at Aachen in 936 by Hildebert, archbishop of Mainz (927–37).Footnote 96 Otto ii, who later appointed Willigis as chancellor and archbishop, had been crowned at Aachen Cathedral in 967, jointly by the archbishop of Cologne and Willigis's predecessor at Mainz, William (954–68).Footnote 97 Otto ii died in November 983. The new king of Germany, and later Holy Roman emperor and king of Italy, his three-year-old son Otto iii, was also crowned at Aachen Cathedral on Christmas Day that very year, the ceremony being led by Willigis himself.Footnote 98 The archbishop probably expected to develop a similarly close relationship with the young king and his future offspring. Folios 88r–v, 89r–v and 90r–v (pp. 175–80) of the manuscript contain blessings denominated ‘benedictiones regales’, whose texts exalt the role of the emperor and the importance of the priesthood that serves the monarch, including a number of Old Testament references (‘D(eu)s qui congregatis in tuo nomine sa mulis medium te dixisti assistere corona valentem imperatorem da gratiam sacerdotibus quam Abraham in holocausto’). Had CS398 been produced before 983, the benedictional might have been paraded in Aachen on that day. At some point of the solemn ceremony, perhaps the blessing gesture of the manuscript's Maiestas Domini would have been oriented towards the enthroned infant Otto iii. The precise chronology of the manuscript, therefore, remains an unsolved (but significant) problem. Otto iii died unexpectedly in 1002. At Mainz, Willigis crowned the new monarch, Henry ii, king of Germany in July of that year.Footnote 99 It is very likely that Codex Sangallensis 398 was used by Willigis and his subordinates during the coronation at Mainz of the last of the Ottonian monarchs. The image of the Maiestas Domini in the manuscript stood then as an earthly representation, a physical reminder of the power and authority upon which both Henry's realm and the Mainz archbishopric ultimately depended.

Otto iii and Henry ii were avid commissioners and recipients of sumptuously decorated manuscripts, such as Gospel-Pericopes or sacramentaries. The study of Ottonian and early Salian manuscript art has for too long orbited around explicit visual relationships of Christocentric kingship in imperial portraiture and donation scenes. Moreover, researchers (particularly in Europe) have also prioritised iconographic relations among extensive narrative cycles of Christ's life, following more traditional approaches to the manuscript medium.Footnote 100 Yet, the study of single images such as the Maiestas Domini of Codex Sangallensis 398, consistently sidelined due to their apparent aesthetic simplicity, can open the door to further consideration of the role and reception of visual culture in the regular liturgy of the period. In order to define the performativity of a medieval illuminated manuscript, specialists must rely upon its textual content, the study of the ceremonies in which the manuscript was involved, its iconographies and the symbolism that they conveyed in certain contexts. Scenes such as the Christ in Majesty or a Crucifixion, with a powerful symbolism for medieval audiences, reinforced the liturgical message and the emotional experience of viewers during the services. In contrast, the potential study of the performative use of luxurious and ex-voto manuscripts, such as the Benedictional of St Æthelwold or the several examples of Ottonian Gospel-Pericopes intended for royal use, is less plausible. The key importance of their decorative apparatuses reflected the primarily commemorative and symbolic functions of these manuscripts.

In the absence of primary sources, studies on the performativity of early medieval manuscripts require, to a certain extent, the formulation of hypotheses. However, other examples of medieval visual culture have proved valuable, leading to a clarification of hypothetical original practices and the handling of manuscripts in early medieval liturgical contexts. Nowadays, the art historical structuralist study of a decorated liturgical manuscript, such as this Mainz benedictional, requires the investigation of all possible aspects of its original function and reception, not only of its aesthetic components.

APPENDIX

List of Blessings, Codex Sangallensis 398 (Mainz, c. 1000)Footnote *

p. 3: In vigilia natalis dmi (beginning)

p. 4: Image of the Christ in Majesty

p. 5: Ds qui in filii sui (opposite page, continuation of the Christmas Eve blessing)

pp. 6–7: Incarnatione

pp. 8–9: Benedicat vobis Omps Ds vestram

pp. 9–10: B. in natali S. Stephani

pp. 10–11: B. in natali Johann Evangltae

pp. 11–12: B. in natal Innocentum

pp. 12–14: B. in octava Dmi

pp. 14–15: B. in Theophania

pp. 15–16: B. in Purific Sce Mariae

pp. 16–17: B. inicio Quadrag

pp. 18–19: Dom ii in quadragis

pp. 19–20: Dom iii in quadrag

pp. 20–1: Dom iiii in quadrag

pp. 21–2: Dom v in quadrag

pp. 22–3: B. in ramis palmari

pp. 23–4: B. Ite alia in Passione Dni

pp. 24–5: B. in caena Dni

pp. 25–6: in sbb sco

pp. 26–8: In die sco

pp. 28–9: B. in octava Pasc

pp. 29–30: B. de Resurrectione Dni

pp. 30–1: Item alia benedic

pp. 31–2: Iunior diebus

pp. 32–3: B. in die Ascension Dni

pp. 33–4: B. in Vig Pentecostes

pp. 34–5: B. in die Sco Pentecostes

pp. 36–7: B. in nal S. Iohann Baptiste

pp. 37–8: Benedic in Festivates Crucis

pp. 38–9: In natale Aploru Petri et Pauli

pp. 39–40: B. in festiv Sanctae Mariae

pp. 40–1: In festivit S. Ioh de martyrio

pp. 41–2: B. de Adventu Dmi

pp. 42–3: Item alia ben

pp. 43–4: In nat unius Apli

pp. 44–5: In nal unius Mart

pp. 45–6: In n plurimoru mart

pp. 46–7: In nat unius confes

pp. 47–8: In nat plurimor conf

pp. 48–9: In natal unius virginis

pp. 49–50: In nat plurimar virg

pp. 50–1: Ben cotidianis diebus

pp. 51–2: Item alia benedictio

pp. 52–3: Item alia b

pp. 53–4: Item alia b

pp. 54–5: Alia ben

pp. 55–6: Item alia b

pp. 56–7: Item alia b

p. 57: Alia benedictio

pp. 57–8: Item alia b

pp. 58–9: Item alia ben

pp. 59–60: Item alia ben

pp. 60–2: B. super rege dicenda tepr synodi

pp. 62–3: B. in dedication eccle

pp. 63–4: In annivsaria dedec eccle

pp. 64–5: B. super rege dicenda

pp. 68–9: Populu quum qs Dme

pp. 69–71: Respice omps Ds de celo plebe tua propicius

pp. 71–2: B. in nat Sci Stephani

pp. 72–3: B. in n Iohannis

pp. 73–4: B. in nat Innocentu

pp. 74–6: B. in octava Dni

pp. 76–8: B. in die Theophanie

pp. 78–9: In octava Theophan

pp. 79–80: B. in n Sci Hilarii Epi

pp. 80–2: Ben. in natl cathedre Sci Petri

pp. 82–3: B. in n Sci Vincentii

pp. 83–4: B. in Purific S. Mariae

pp. 84–5: Dominicis dieb dicendea Theoph usq in Xlma

pp. 85–6: Dom II post Theo

pp. 86–7: Dom III p Theop

pp. 87–8: Dom IIII p

p. 88: Dom V post Theop

pp. 88–9: Dom VI p

pp. 89–90: Dom VII p

pp. 90–1: Dom VIII p

pp. 91–2: Dom VIIII p

pp. 92–4: Dom II in Xlma

pp. 94–5: Dom III in Xlma

pp. 95–6: Dom IIII in Xlma

pp. 96–8: B. in aurium apertione

pp. 98–9: B. Dom V in Xlma

pp. 99–100: In die Palmarum

pp. 100–1: In cena Dni

pp. 101–2: B. in vigilii S Pasch

pp. 102–4: B. in Die Sco Paschae

pp. 104–5: In II Fra Pascha

pp. 105–6: In III Fer Pasch

pp. 106–8: In IIII Fer Pasch

pp. 108–9: In V Fer

pp. 109–11: In VI Fer

pp. 111–12: In Sabbato

pp. 112–13: Ad clausu Pasch

pp. 113–14: In let maiore

pp. 114–15: Dom I p clausum

pp. 115–16: In dom II p clausu Pasch

pp. 116–18: B. dom III p clas Pen

pp. 118–19: Dom IIII ut Sup

pp. 119–20: In Ascensione Dni

pp. 120–1: De Invencione Sce Cru

pp. 121–2: In Dom p Ascensione D

pp. 122–4: Benedicto in die Sco Pentecostes

pp. 124–5: In Oct Pentecost

pp. 125–6: In Dom p Pentecost

pp. 126–7: Domc II

pp. 127–8: Domc III

pp. 128–9: In nat S Iohannis B

pp. 129–30: Domc V

pp. 130–1: In natl Apslm Petri et Pauli

pp. 131–2: Dom VI p Pentecos

pp. 132–3: Domc VII

pp. 133–4: Domc VIII

pp. 134–5: Domc VIIII

pp. 135–6: Domc X

p. 136: In natl Machabeor

pp. 136–7: Domc XI

pp. 138–9: In Assuptione S Mar

pp. 139–40: Domc XII

pp. 140–1: Domc XIII

pp. 141–3: De Passione S Ioh

pp. 143–4: Dom XIIII

pp. 144–5: De Nativit S Marie

pp. 146–7: Dom XVI

pp. 147–8: In Dom XVII p Pent

pp. 148–50: In Festivit S Michahel Arhangl

pp. 150–1: Domc XVIII

p. 151: Domc XVIIII

pp. 151–2: Domc XX

pp. 152–3: Domc XXI

p. 154: Domc XXII

pp. 154–5: Domc XXIII

pp. 155–6: in nat Sci Martini

p. 157: De Adventu Dni

pp. 157–8: In natl S Andree

pp. 159–60: Domc II de Advent

pp. 160–1: De Adventu III

pp. 161–2: IIII de Advent

pp. 162–3: Dom V de Advent

pp. 163–4: In natl unius martyr

pp. 165–6: B. in natl plurimor mar

pp. 166–7: in natl unius confessoris

pp. 167–8: in natl plurimor confessor

pp. 168–9: B. in natl virginum

pp. 169–70: B. in nat Aeclessiae

pp. 170–1: B. in conventu Eporu

pp. 171–2: B. in natal Epi

pp. 172–4: B. super populu cu Eps suum celebrat natl

pp. 174–5: B. super Ancillas Dni

pp. 175–7: Benedictio regalis

pp. 177–80: Alia benedictio regalis

pp. 180–1: B. in tempr belli

pp. 181–2: B. quando in trib missa celebrat

pp. 182–3: B. in temp qd absit mortalitatis

pp. 183–4: B. cu egreditur in itinere

pp. 184–6: B. dum in navigiu ascenditur

pp. 186–7: B. super homine unu

p.187: Conclusio omnium bened

pp. 188–90: Item Benediction congruentissime ex lectionibus Apostolicis et Evangelicis ordinatae (Preface). In vigilia Pentecostes

pp. 190–1: In die Sco Pentecostes ben.

pp. 191–3: B. in octab Pentec

p. 193: Benedict in Dom III post Pent

p. 193–4: In Dom IIII p Pent

pp. 194–5: B. in Dom V p Pent

p. 195: B. in Dom VI post Pentecost

p. 196: B. in Dom VII post Pent

pp. 196–7: Benedict in Dom VIII post Pent

pp. 197–8: In Dom VIIII post Pent

p. 198: B. in Dom. X p Pentec

pp. 198–9: Benedict in Dom XI p Pentec

pp. 199–200: In Dom XII p Pent

p. 200: B. in Dom XIII p Pent

pp. 200–1: B. in Dom XIIII p Pent

pp. 201–2: B. in Dom XV p Pentec

p. 202: Benedict in Dom XVI p Pent

pp. 202–3: Benedictio in Dom XVII p Pent

p. 203: in Dom XVIII p Pent

pp. 203–4: Sabbato in duodecim lection

pp. 204–5: Benedictio in Dom XVIIII p Pen

pp. 205–6: Benedictio in Dom XX p Pentec

p. 206: Benedictio in Dom XXI p Pen

pp. 206–7: Benedictio in Dom XXII p Pen

pp. 207–8: Benedictio in Dom XXIII p Pen

p. 208: Benedictio in Dom XXIIII p Pentec

pp. 208–9: Benedictio in Dom XXV p Pentec

pp. 209–10: Benedictio in Dom XXVI p Pen

pp. 210–11: B. in Festivitate Omn Scrm

p. 211: Alia

pp. 211–12: Alia

pp. 212–13: In dedicatione aecclae

pp. 213–14: Alia

p. 214: In synodo

pp. 214–15: Alia benedict

pp. 215–16: Alia

pp. 216–17: Benedictiones de Septuagesima

pp. 217–18: B. in Sexagesima

pp. 218–19: B. in Quinquagesima

pp. 219–20: In natale Dmi primo mane