Introduction

Internationally, the primary function of the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) is the timely and safe delivery of the sick or injured to definitive care. Historically, performance of these services, and the quality of prehospital emergency care (PEC) delivered, has been assessed largely based on surrogate, non-clinical endpoints such as response time intervals or other crude measures of care (eg, stakeholder satisfaction).Reference Myers, Slovis and Eckstein 1 - Reference O’Connor, Slovis, Hunt, Pirrallo and Sayre 3 Given that such measures are relatively simple, quantifiable, and readily understood by both the lay public and policy makers, they became the predominant indicators of EMS quality and performance.Reference Maio, Garrison and Spaire 2 , Reference Moore 4 , Reference Dunford, Domeier and Blackwell 5

However, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that adhering to such measures has been reported to offer limited benefits, may only be applicable in select patients, and are insufficient alone to gauge the quality of care provided by EMS.Reference Studnek, Garvey, Blackwell, Vandeventer and Ward 6 - Reference Blackwell, Kline, Willis and Hicks 10 In addition, advances in EMS systems and services world-wide have seen their scope and reach continue to expand.Reference Stirling, O’Meara, Pedler, Tourle and Walker 11 - Reference Cooper and Grant 14 This historical approach towards quality assessment, in conjunction with the recent growth and development within the industry, has dictated that these services take greater accountability for their performance and the quality of care they deliver.

Over the last two decades, significant progress has been made in this area, largely in the form of the development of evidence-informed quality indicators (QIs) of PEC.Reference Maio, Garrison and Spaire 2 , Reference Spaite, Maio and Garrison 15 - Reference Siriwardena, Shaw, Donohoe, Black and Stephenson 18 Quality indicators represent one aspect of health care quality measurement that are designed to measure “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”Reference Mainz 19 Quality indicators have the advantage of not only documenting quality of care, but they assist in benchmarking quality and performance, they guide priorities for improvement initiatives, and they support overall accountability and transparency within health care.Reference Mainz 19

The ideal QI is one that is meaningful, scientifically sound, generalizable, and easily interpreted.Reference McGlynn and Asch 20 Despite the existence of relatively robust and comprehensive recommendations in the literature guiding the development of health care QIs, the process can be an inherently complex task, which in order to accomplish, must be designed and implemented with scientific rigor.Reference Mainz 19 - Reference Ballard 22 This is of particular importance when considering the underlying frameworks and data components necessary for their creation.Reference Mainz 19 - Reference Ballard 22 These components not only ensure that the QIs are appropriately implemented and utilized, but they also aid in reducing subjectivity in their application and interpretation as well.

Little is known about the development of QIs specific to the PEC environment, despite the recent progress reported. The purpose of this study was to assess the characteristics of development and data attributes of PEC-specific QIs in the literature.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted for the period up to April 2016 to identify peer-reviewed literature that examined QIs in the PEC environment. The scoping review methodology was selected given its primary aim to “map” the extent, range, and nature of a particular topic, summarizing the scope of evidence in order to convey the breadth and depth of a particular field.Reference Arksey and O’Malley 23 , Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien 24 This methodology is of particular use in new and emerging disciplines, where the quality of evidence and methodologies applied in previous research is unknown or varied.Reference Arksey and O’Malley 23 , Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien 24

Search Strategy

Articles were identified by searching the following databases: PubMed (National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland USA); Embase (Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; EBSCO Information Services; Ipswich, Massachusetts USA); Web of Science (Thomson Reuters; New York, New York USA); and the Cochrane Library (The Cochrane Collaboration; Oxford, United Kingdom). All searches were performed with no restrictions in terms of publication type or journal subset, date of publication, or patient age. Where applicable, searches were limited to English language articles and to research involving human subjects only.

Combinations and truncated variations of the following search terms were used for each database search: Emergency Medical Service, prehospital emergency care, ambulance service, quality indicator, quality measure, performance measure, and performance indicator. Relevant wildcards were used to account for singular and plural forms of each of the search terms. Variations in spelling were additionally used in varying combinations to broaden the search.

To increase the sensitivity of the search strategy, the OpenGrey (Institut de l’Information Scientifique et Technique; Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy Cedex, France) repository of grey literature (ie, unpublished academic literature) was searched using the above-mentioned terms. In addition, the list of references of all included articles were manually searched for any potential articles meeting inclusion criteria. Lastly, the websites of the National Quality Forum (Washington, DC USA), 25 the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Rockville, Maryland USA), 26 and the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse (Rockville, Maryland USA) 27 were manually searched for PEC-specific QIs.

Inclusion Criteria

For the purpose of this study, a QI was defined as: any measure that compared actual care against ideal criteria; or a tool used to help assess quality and/or performance. The threshold for inclusion was purposely kept low, and the following minimum criteria were utilized when identifying studies for further analysis:

-

- The aim of the research was to discuss, analyze, or promote quality measurement in the PEC environment;

-

- Research that proposed at least one prehospital QI of care or performance; and

-

- All peer-reviewed literature meeting inclusion criteria published prior to April 2016.

Exclusion Criteria

Non-English research, studies that examined disaster management/major incident response QIs, or research aimed at inter-facility transport measures of care were excluded. Furthermore, secondary research that examined QIs developed as part of a primary study already included in the analysis was excluded.

Article Review

Eligible articles were identified and analyzed in two parts. Firstly, the results of the database search were reviewed by title and abstract for potential inclusion, using the above-mentioned definitions and criteria (IH and VL). Disagreements between the two assessors were discussed, and if agreement could not be reached, the article was retained for further review. For the second part, the full-text articles remaining after the title and abstract review were independently reviewed for satisfaction of the definitions and minimum inclusion criteria, and data were extracted utilizing a standardized data extraction form (Microsoft Excel 2010; Redwood, Washington USA; IH and VL). There was a high-level of agreement between raters for the inclusion of full-text articles for data extraction (Kappa statistic=0.941). All disagreements in full-text article review and data extraction were resolved by consensus with no need for resolution by a third reviewer.

Article characteristics extracted included: type of research/methodology, country of origin, year of publication, institutional academic status, source of funding, population/age demographic studied, and description of the QIs within a broader organizational quality framework or structure. While seemingly abstract, for the purposes of this study, the latter component was defined as demonstration of how and/or where the QIs developed in the article reviewed aligned within a larger measurement or assessment structure in the PEC environment.

Quality indicator characteristics extracted included: origin of the QI, data source for developing the QI, definition of the QI data components, and whether or not a pilot of the QI was reported. In addition, the QIs found were categorized by the authors into one of two domains: Clinical or Non-Clinical. The criteria for QIs categorized into the Clinical domain were: those that assessed a specific intervention, or were dependent on the presence/absence of a disease or injury characteristic (eg, vital signs, symptoms, or treatment administered). Quality indicators categorized into the Non-Clinical domain were defined as those that primarily focused on an aspect of service delivery (eg, communication or documentation). Within each domain, the QIs were further divided by sub-domain (ie, clinical pathway for Clinical QIs; or by area of service for those QIs categorized as Non-Clinical).

Lastly, if not identified as such within the article, each QI was additionally classified according to Donabedian’s quality assessment classification framework.Reference Donabedian 28 Donabedian’s model conceptualizes quality of care and performance into one of three primary dimensions: Structure-, Process-, or Outcome-based indicators of quality.Reference Donabedian 28 Structure-based QIs were defined as those that examined the attributes of the setting in which health care occurs, and primarily included material resources (eg, facilities, equipment, and financing), human resources, and organizational structure. Process-based QIs were defined as those that outline the steps in the process of health care (ie, what the health care provider does to maintain or improve health; eg, making a diagnosis or recommending/implementing treatment). Lastly, Outcome-based QIs were identified as those that described the effects or impact of care on the health status of patients and/or populations (ie, changes in a patient’s health status that could be attributed to antecedent care).Reference Mainz 19 - Reference Ballard 22 , Reference Donabedian 28 Article and QI characteristics were summarized as counts and proportions using Microsoft Excel 2010.

Results

The literature search identified a total of 1,843 potential articles for review (Figure 1). Following the title and abstract review, 1,754 articles did not meet inclusion criteria and were excluded, leaving 89 articles for full-text review. An additional 14 articles were included following a review of the list of references of the 89 articles identified. Following the removal of duplicate texts, 25 articles remained for the full-text review. The manual review of the OpenGrey repository revealed no applicable QIs for inclusion. Fifteen QIs were identified via a search of the National Quality Forum, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse websites.

Figure 1 Selection of Articles for Review.

Description of Articles

The most common type of methodology employed in the development of the article-based QIs was split between a Delphi/RAND/Consensus type methodology (n=7; 28.0%) and Observational Cohort study methodology (n=7; 28.0%; Table 1). The majority of research was published within the last decade (n=17; 68.0%) and largely originated within the USA (n=17; 68.0%). All articles identified for the full-text review originated from countries identified as “developed” or “high-income.” For just over one-half of the articles (n=13; 52.0%), the academic status of the corresponding institution was that of a University or Higher-Learning Institute, followed by a mixture of both teaching (ie, University/Higher Learning) and non-teaching institutions (n=9; 36.0%). Eight (32.0%) of the articles identified declared some form of government funding, followed by grants from private foundations (n=5; 20.0%). Nine (36.0%) of the articles did not declare their source of funding. Discussion of the QIs developed, within the context of a broader organizational quality framework or structure, was found to occur in relatively few articles under review (n=7; 28.0%).

Table 1 Article Characteristics Footnote a , Footnote b

a Excludes web-based indicators.

b Categories not mutually exclusive.

Description of QIs

A total of 331 QIs were identified via the article review, with a median of 13 QIs per article (inter-quartile range 4.5-21), and a range of one to 29 QIs per article. In addition, 15 QIs were identified via the website review, for a total of 346 QIs. The article authors were cited as the most common origin or source for the development of QIs found (n=260; 75.1%). One hundred and fifty-two QIs (43.9%) were developed with the involvement of a local health care provider group, and 80 (23.1%) received input from a national or international organization or body (Table 2). Just under one-third of the QIs identified in the article review were of mixed origin (n=105; 30.6%) in their development. The most common reported data source utilized was a survey/questionnaire (n=172; 49.7%) or medical record review (n=80; 23.1%). Over one-third of the QIs reviewed (n=126; 36.4%) did not have a reported data source for their development or otherwise could not be explicitly determined.

Table 2 Quality Indicator Characteristics Footnote a

Abbreviation: QI, quality indicator.

a Categories not mutually exclusive.

Nine specific data components of the reported QIs were assessed in an attempt to provide insight into their development. The Population on Whom the Data Collection was Constructed made up the most commonly reported component (n=276; 79.8%), followed by a Descriptive Statement for the QI in question (n=220; 63.6%). The least reported components were those of Timing of Data Collection, reported for 42 QIs (12.1%), and Timing of Reporting (n=42; 12.1%). Pilot testing of the QIs was reported on 120 (34.7%) of the QIs identified in the review.

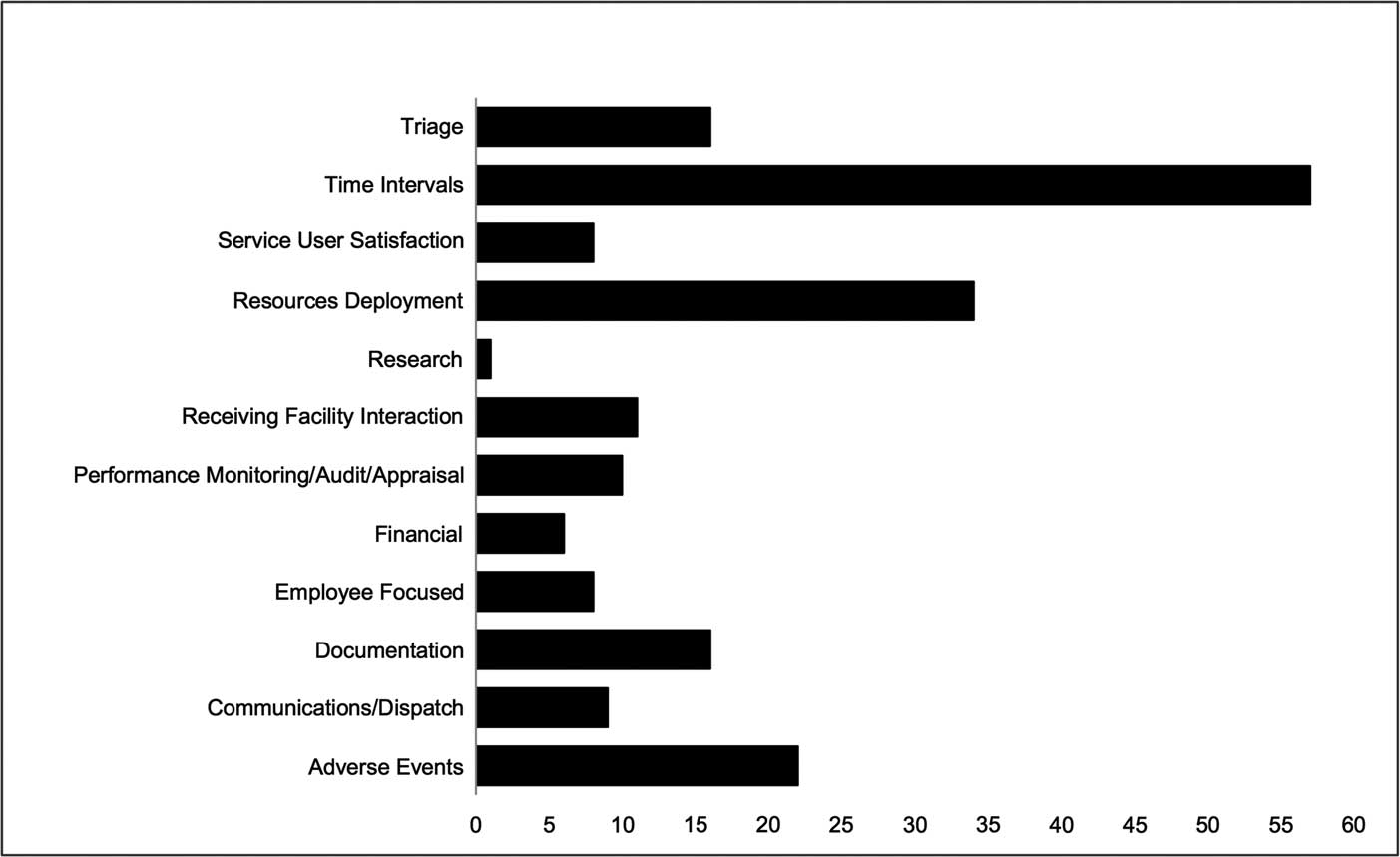

Of the 346 QIs identified, 148 (42.8%) were categorized as primarily Clinical. Figure 2 summarizes the further categorization of the Clinical domain QIs by sub-domain. Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest contributed the highest number within this domain (n=45; 30.4%), followed by the Non-Traumatic Chest Pain/Acute Coronary Syndrome sub-domain (n=30; 20.3%) and the General sub-domain, made up of largely intervention or medication-based QIs (n=26; 17.6%). Figure 3 summarizes the categorization of the Non-Clinical domain (n=198; 57.2%). The Non-Clinical QIs were further categorized into the basic area of service within the PEC environment they affected. Time-Based Intervals contributed the greatest number (n=57; 28.8%), followed by Resource Deployment (n=34; 17.2%) and the Adverse Event Detection/Classification sub-domain (n=17; 9.0%). Table 3 Reference Siriwardena, Shaw, Donohoe, Black and Stephenson 18 , Reference Norris 29 - Reference Nakayama, Saitz, Gardner, Kompare, Guzik and Rowe 46 and Table 4 Reference Sobo, Andriese, Stroup, Morgan and Kurtin 30 , Reference Rosengart, Nathens and Schiff 33 - Reference Oostema, Nasiri, Chassee and Reeves 38 , Reference O’Meara 43 - Reference Spaite, Valenzuela, Meislin, Criss and Hinsberg 53 illustrate a breakdown of the Clinical and Non-Clinical domain QIs by source article. Donabedian’s quality assessment classification framework was the only such system employed for the classification of the reported QIs, and it was utilized in three (12%) of the articles reviewed. Thirty-nine of the article QIs and all 15 QIs found via the website review were classified according to this system (15.6%). The remaining 292 QIs were assigned a classification by the authors as part of the review, using Donabedian’s framework. Process measures made up the largest groups of both the reported and assigned classifications (Reported n=31, 9.0%; Assigned n=194, 66.4%). Table 2 highlights the division of the reported and assigned classifications for each QI.

Figure 2 Distribution of Clinical Domain Quality Indicators (n=148).

Figure 3 Distribution of Non-Clinical Domain Quality Indicators (n=198).

Table 3 Quality Indicators – Clinical Domain

Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndrome; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; QI, quality indicators.

Table 4 Quality Indicators – Non-Clinical Domain

Abbreviation: QI, quality indicator.

It was the intention of the authors to attempt to assess the quality of evidence presented in each article under review a-priori; however, given the use of consensus-based methodologies in the majority of the articles assessed, in conjunction with little to no discussion of the underlying evidence base within each of the articles, this evaluation was abandoned.

Discussion

This scoping review revealed a substantial body of literature regarding QIs specific to PEC. It is apparent that there is rising interest and understanding about the importance of quality measurement within PEC, evident by the increasing number of publications in recent years involving these concepts. This drive appears to be largely led by the academic community, with the involvement of non-teaching/non-higher learning institutions found to be relatively scarce, or at least their contribution under-reported. Given that quality measurement and improvement require a largely pragmatic approach, it is essential that closer collaboration between academic institutions and EMS organizations occurs to improve the development of QIs for the PEC environment.

Similarly, there was an apparent lack of involvement of large national and international emergency care societies, committees, or networks in the development of the QIs identified by this review. Involvement of such bodies could potentially bring significant benefits for research in this area.

All of the research identified in this review originated in “high-income” or “developed” settings, with over one-half produced in North America, most notably the USA, followed by the United Kingdom and Australia. With the exception of one study originating in the Netherlands, there was an absence of research regarding PEC quality measurement from the remainder of Europe. It is interesting to note, however, that EMS models employed across these regions vary significantly. The North American approach utilizes emergency medical technicians as frontline staff and relies largely on medical control with physician oversight for its governance.Reference Pozner, Zane, Nelson and Levine 54 This aligns somewhat with the British and Australian approach where non-physician practitioners (paramedics) are employed under independent licensure.Reference Roudsari, Nathens and Arreola-Risa 55 In contrast, the Franco-German model utilizes physicians as frontline staff, whereas in Northern Europe, specialist PEC nurses are responsible for delivering PEC.Reference Adnet and Lapostolle 56 , Reference Lindström, Bohm and Kurland 57 It is, however, impossible to determine any correlation between these two factors, and in addition, could potentially be explained through the limitation in search criteria to English language studies only.

Overall, the categorization of QIs was weighted towards what could be best described as Non-Clinical measures of quality. While these undeniably have an important part to play, one could argue that the legacy of surrogate measures such as response time targets continue to exert an influence in measuring quality within PEC, especially considering that Time-Based QIs made up the largest sub-domain amongst the Non-Clinical domain in this review. Within the Clinical domain, Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest and Non-Traumatic Chest Pain/Acute Coronary Syndrome-based QIs contributed the largest number of QIs within this category. This is unsurprising given the known impact of PEC on outcomes for these patients.

Process-defined QIs were the most common classification reported in this review, followed by Structure-based indicators, when the QIs assigned a classification by the authors were taken into account. Patient outcomes and adverse events occurring in this time frame are inherently difficult to report in PEC, given the short duration of care in which these patients are exposed to EMS. As such, PEC quality assessment lends itself to evaluation by care processes and could account for this group contributing the largest classification type. The relative simplicity of Structure-based indicators, in both their implementation and interpretation, combined with the above-mentioned potential historical influence of time-based measures, could account for the large number of this group as well.

The description of the component parts for the QIs identified in this review was severely lacking, despite established recommendations guiding development.Reference Mainz 19 - Reference Ballard 22 These elements are as important as the QI itself, as they not only provide guidance and information for other researchers on the feasibility of implementation of the QI, but also on their utilization and analysis as well.Reference O’Brien, Shortell and Hughes 58 - Reference Perla, Provost and Murray 61 Similarly, it was apparent from this analysis that there is insufficient consideration of PEC QIs within the broader organizational quality frameworks. The success of any form of quality measurement, be it through QIs, direct observation, trigger tools, or mortality reviews, is limited by the strength and rigor of the system in which it operates, and the ability of the system to ensure completion of the quality improvement process. Consideration of the importance that a quality framework adds towards the implementation of individual QIs is essential. When combined with other strategies of quality measurement, this not only ensures their appropriate use, but also affirms their relation to the final experience and outcome of a patient encounter with the health sector. One need only examine the development of response times as the sole historical measure of PEC quality as a prime example of poor QI implementation.

Limitations

The scoping review methodology has numerous advantages, many of which lie with the simplicity of its aim. However, this simplicity is not without its limitations. There is no established approach towards assessing the quality of research or evidence under review, such as that found with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines or Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines. Similarly, there is no system of assessing homogeneity of evidence or method of data synthesis.

The search criteria to identify potential articles for review was limited to English-language research only in this study. This could have potentially skewed the search results of articles for further review, and possibly account for the notable absence of PEC-specific research originating in South America, Africa, or Asia.

Conclusion

While there is considerable interest in furthering PEC quality measurement, current publications are restricted to isolated pockets of activity and lack generalizability. Support from professional emergency care societies, or those with a vested interest in PEC, is required to further the prioritization of, and participation in, the development of PEC quality measurement. In addition, closer attention to the details and reporting of QIs is required for research of this type to be more easily extrapolated and generalized.

Author Contributions

IH, VL, PC, LW, and MC conceived the study. IH and VL conducted the data collection and analysis. IH drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. IH takes responsibility for the paper.