Introduction

Among the drawings, engravings, paintings, calligraphic samples and documents preserved in the Topkapı Palace Library’s albums H.2153 and H.2160, there is a group of some sixty-five paintings and preparatory sketches, which could be termed caricatures (Figures 1–5).Footnote 1 They are relatively large in format, measuring up to 26 × 35 cm, and their focus lies on the depiction of figures, who are almost invariably grotesque. Background details, such as a stream, a tree or a pestle and mortar, are only added when they are germane to the action. The paintings are executed in a restricted color palette, with highlights in gold, often on poor-quality paper, and depict two broad categories of subject matter: humans, generally in small groups, engaged in activities such as conversation, drinking, dancing, labor and the pasturing of their mounts; and demons, some of whom appear to ape the humans, but who also spirit them and their mounts away, and who in one notable instance dismember a horse. Many of these images bear attributions in a later hand to a single artist, “Mohammad-e Siāh Qalam” (Mohammad of the Black Pen), or depending on the scholar’s linguistic predilections, “Mehmed Siyah Kalem,” who is, bluntly, an unknown quantity, although the name is connected with another set of large, polychrome images in the same albums.Footnote 2

Figure 1. TSM H.2153 f.40b.

Source: Image courtesy Topkapı Palace Museum.

Figure 2. TSM H.2153 f.55a.

Source: Image courtesy Topkapı Palace Museum.

Figure 3. TSM H.2153 f.64b.

Source: Image courtesy Topkapı Palace Museum.

Figure 4. TSM H.2153 f.135a.

Source: Image courtesy Topkapı Palace Museum.

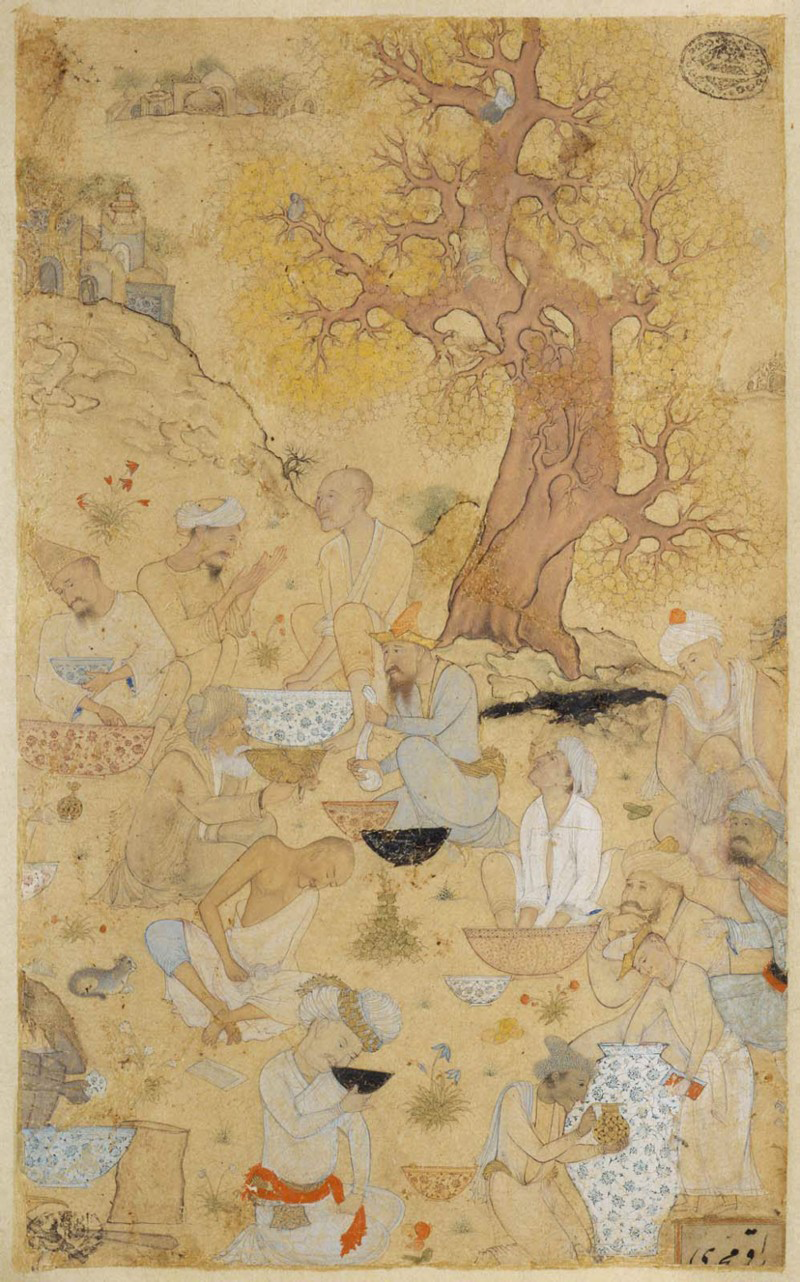

Figure 5. TSM H.2160 f.10a.

Source: Image courtesy Topkapı Palace Museum.

The attribution of a single painter’s name to the images of humans and demons belies the evidence that, while an original group may have been executed within a short spell, paintings that reproduced their style and iconography continued to be created over a significantly longer period of time.Footnote 3 Since the securely dated material in the two albums spans the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries and a primary geographical range of modern-day Iraq to Uzbekistan, with additional material from Europe and China, a majority of scholars have dated the production of the scenes of humans and demons to either the fourteenth or the fifteenth centuries.Footnote 4 Aspects of style, iconography and subject matter have drawn several researchers to the conclusion that the paintings were produced in an area where Islamic and non-Islamic cultures comingled.Footnote 5 Commenting on the marked Chinoiserie style seen in a number of the images, some have argued that the paintings must have been produced in a geographical area where the Islamic world meets China or Mongolia,Footnote 6 a point superficially reinforced by the fact that the paper on which some of them were painted appears to have been sourced from Tibet or China.Footnote 7 Others, perceiving the paintings to represent a recently Islamized, Turkic world, have attributed the paintings to the Qipchaq steppes or Transoxiana.Footnote 8

On the other hand, several other writers on the subject have reasoned that since the style of the paintings can at best be described as Chinoiserie, and not “Chinese,” and because there is little material evidence that would connect the paintings with art in Inner Asia during the fourteenth or fifteenth centuries,Footnote 9 there is nothing to preclude their production in greater Iran, in a center of artistic activity such as Herat or Tabriz.Footnote 10 Concrete comparisons have been made between the corpus of Siāh Qalam paintings and iconographic elements of several illustrated manuscripts produced in western Iran and Iraq, including a demon depicted in the Bodleian Kitāb al-bulhān (Iraq, between 1382 and 1410),Footnote 11 nomads in the marginal drawings of the Freer Divān of Soltān Ahmad Jalāyer (western Iran or Iraq, late fourteenth or early fifteenth century),Footnote 12 two scenes from the Diez albums depicting princes with an elderly woman and a group of minstrels (datable to western Iran, mid-fourteenth century, on stylistic grounds),Footnote 13 and the demons seen in the now dispersed Shāhnāmeh of Shāh Tahmāsp (Tabriz, early-to-mid sixteenth century).Footnote 14 Further pointers to the history of the images’ reception are provided by a small number of related paintings thought to have been produced in northern India or the Deccan, the latter in particular home to a large number of Iranian emigres.Footnote 15

Scholars have paid considerable attention to formal comparison between the Siāh Qalam group and other images, with the aim of highlighting similarities that could narrow down places and a range of dates for their production. A conference dedicated to the corpus was held at the School of Oriental and African Studies in 1980, yet its proceedings, while invaluable, did not permit a unifying conclusion.Footnote 16 It is perhaps unsurprising, given the paintings’ focus on figures and their lack of background detail, that less attention has been paid to context, be it historical, political, religious, literary or social, but the paintings should be studied with due concern for these issues, as implicit assumptions about the environment in which they were produced have underpinned most studies devoted to them, and have tended to inform the range of material surveyed for formal comparison.

This paper compares the paintings’ representation of humans and demons with material in Persian and Arabic on the demonic nature of illicit behavior, arguing that while the Siāh Qalam paintings do not appear to illustrate a single text, they engage with a field of ideas which is partly parodic and partly moralistic, and which found expression in a number of documentary, legal and literary texts, and several other paintings. It does not claim that this approach will solve complex questions concerning the circulation of artistic techniques and iconography, but it does argue that greater attention to the basic problem of what these images depict will help to address the issue of how they function as works of art and the topic of who may have acted as their initial audience. The debate about the location in which the paintings could have been produced has been predicated not only on their form but also on what they are thought to represent, meaning that there is a greater tendency for scholars who would argue that the paintings represent an un-Islamic or newly Islamized society to focus on formal comparisons with art from Inner Asia and China, while those who see the paintings within the ambit of Islamic culture have tended to argue for a West Asian provenance.Footnote 17 In focusing on representations of illicit behavior, this paper also aims to demonstrate that ideas about the nature of Islamic culture and society are not necessarily more keenly debated in the historical heartlands of the Islamic world than at its margins.

When the Siāh Qalam paintings were first discussed in twentieth-century scholarship, they were generally attributed to the Qipchaq steppes or Central Asia on purely formal grounds.Footnote 18 Since the 1950s, however, aspects of religious and social history have also informed the debate. The two primary motivating factors for ascribing the Siāh Qalam paintings to a Central or Inner Asian milieu have been the assumption that their interest in the demonic derives from a non-Islamic environment, and the connected argument that the humans depicted in the paintings must represent a recently converted populace, which melded practices that have been described as shamanist, Buddhist or Manichaean, together with Islam.Footnote 19 While certain aspects of style and iconography in the Siāh Qalam paintings may ultimately derive from non-Islamic contexts, it is harder to substantiate the argument that they were produced in a culture where Buddhism or Manichaeism formed part of the artists’ or the intended viewers’ lived experiences and identity.

The notion of direct links to Manichaean art or doctrine is problematic because Manichaeism had ceased to be a religious force in Inner Asia by the mid-eleventh century, roughly 300 years before the earliest widely accepted dating of the paintings, and its centers had moved to the littoral of the South China Sea.Footnote 20 Çağman’s contention that the Siāh Qalam paintings both recall the story-telling traditions of Buddhism and Manichaeism and record the social environment in which such stories were performed is hard to prove, since the paintings neither appear to engage with aspects of Buddhist or Manichaean doctrine, nor display any great generic similarity with extant comparanda, such as the sketches and performance scrolls from early medieval Dunhuang that have been studied by Fraser.Footnote 21 Although it is undeniable that a number of the Siāh Qalam paintings reflect iconographic elements found in Buddhist art, the hypothesis that the artists responsible for these paintings were exposed to art from East Asia through portable materials such as painting manuals, prints and copybooks represents an alternative to the notion that they were physically stationed mid-way between Iran and China.

Some initial remarks are also required about perceived links between the paintings and shamanism. It has been maintained that images such as H.2153 f.64b (Figure 3), a scene of dancing demons, reflect shamanistic practices of communicating with the supernatural.Footnote 22 At the same time, scholars who have argued that the Siāh Qalam paintings must stem from Inner Asia have tended to assume that shamanism was understood as an analogue to Sufism in Turkic societies.Footnote 23 This thesis was once popular in the field of the history of religion, but it has been revised in recent years.Footnote 24 In the anthropological view, shamanism is often defined “as an applied spiritual technique for the resolution of various material and social problems rather than as a tool for abstract mysticism,” and scholars such as Amitai-Preiss have emphasized the differing needs to which shamanism and Sufism cater.Footnote 25 In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, practices that could be construed as shamanic were carried out by Turkic peoples who considered themselves Muslim throughout the Middle East and Central Asia, and studies such as the one by Devin DeWeese, concerning processes of Islamization in the territories of the Golden Horde, have demonstrated that narratives describing seemingly shamanic figures, or actions with an ostensibly shamanic import, could be used to present Islamization “in terms both familiar and meaningful” to their intended audiences.Footnote 26

While it is therefore possible that some of the Siāh Qalam scenes depict forms of behavior that are supposed to be interpreted as shamanic, this would not necessarily place the paintings at the margin of the Islamic world, either in the geographical location of their production or in the scope of the ideas they present. Furthermore, our interpretation of images such as H.2153 f.64b (Figure 3), the scene of dancing demons, depends on our understanding of their tenor. If the painting is indeed to be interpreted as a depiction of shamanistic practice, is its tone serious or satirical? Does it document devotional practices or satirize them?

Illicit Behavior and the Demonic: Legal, Literary and Visual Evidence

The notion that the paintings’ depiction of demons reflects the influence of non-Islamic culture on the level of ideas is in need of qualification. Ideas about demons, most frequently termed jinn, shayāṭīn or ʿafārīt in Arabic, were central to mainstream Islamic culture in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, especially when it came to discussions of human ethics. In particular, jurists often emphasized the demonic nature of behavior that they considered to be illicit (ḥarām), either by likening those who transgressed to demons, or by describing the processes that led to illicit behavior as demonic possession. The close mental link between abnormal behavior and demonic possession is underscored by Arabic lexicography: the word majnūn, for example, generally translated as “unsound of mind or intellect,” means “possessed by demons,” and the related word junūn signifies both possession and the pursuance of evil acts.Footnote 27 Similarly, the noun ghūl connotes both a kind of desert demon or devil and “anything by reason of which the intellect departs.”Footnote 28 Shayṭān can mean the Devil himself, a demon, or “any blameable faculty, or power [or propensity] of a man,” with Lane giving the idiom rakibahu shayṭānuhu, lit. “his demon mastered him,” to signify “he was, or became, angry.”Footnote 29

Images of demonic possession were pursued with particular vigor in discussions of the consumption of the intoxicants wine (Ar. khamr, with the root meaning of “intoxicant”) and cannabis sativa (Ar. qannab hindī) known by a plethora of names depending on how it was prepared and consumed, including ḥashīsh in Arabic and hashish, bang and dugh-e vahdat in Persian.Footnote 30 Descriptions of the cannabis plant as “the Devil’s herb” (ḥashīshat al-shayṭān) appear to have been a trope in Arabic writing of the Mamluk period (1250–1517),Footnote 31 while representations of frequent users of hashish liken them to demoniacs (addā bi-him al-ḥāl ilā al-junūn).Footnote 32 Such mental images are of relevance for our discussion of the Siāh Qalam paintings, since several of them appear to treat the consumption of intoxicants.Footnote 33

Most obvious in this regard is H.2160 f.10a (Figure 5), which depicts three male figures eyeing a cannabis plant with a certain cupidity.Footnote 34 Beyhan Karamağaralı remarked that another painting depicts two men carrying pouches used to hold hashish (H.2153 f.38b—IA1 fig.310).Footnote 35 Contrary to Karamağaralı’s analysis, hashish does not appear to have been smoked prior to the Safavid period (1501–1736), but generally to have been roasted, ground, mixed with other ingredients and consumed as a kind of pill, or to have been roasted, filtered, adulterated with other ingredients and drunk.Footnote 36 For example, the often comic Cairene poet, ḥadīth man and performer Ibn Sūdūn (d. 868/1464) describes sampling hashish, presumably in the form of a pill, out of a porcelain jar, before doing a sketch for his host.Footnote 37

A third Siāh Qalam image (H.2153 f.90a—IA1 fig.301) depicts a man consuming something from a vial, regarded with horror by the two figures who surround him. The man’s tongue can be clearly distinguished from the vial. While analyses of this painting have tended to focus on technical similarities with figural depiction in the visual culture of China, the men’s emaciated bodies also recall later depictions of drug users. For example, an image that is now in the British Museum (1940,0713,0.49, ascribed to the Punjab Hills, eighteenth century), depicts a gathering of bhang users (Figure 6). Among the figures shown is an emaciated man sitting on his haunches, who bears comparison with the figure to the right of H.2153 f.90a. The emaciation of the figure in the Pahari painting may stem from opium usage.Footnote 38 Several additional images depicting the emaciation caused by the excessive consumption of opium are well known to modern scholarship, including “The Dying ‘Enāyat Khān” (dated 1618, Bodleian, MS. Ouseley Add. 171 f.4b), depicting a Mughal courtier wasted by opium and alcohol addiction.

Figure 6. “A Gathering of Bhang Users”.

Source: British Museum 1940,0713,0.49. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

For jurists such as Ibn Taymiyya (d. 728/1328), the primary problem with the consumption of intoxicants was the user’s subsequent loss of reason (al-ʿaql), and hence their vulnerability to malign forces. A passage from one of his fatwas is worth giving in extenso, as it highlights the connection made between the loss of reason and the demonic:

Should someone’s reason cease to function by an illicit cause, such as drinking wine or eating hashish, or if they should listen to melodious music until their reason disappears, or should someone make heretical devotions until demons (baʿḍ al-shayāṭīn) join them and alter their reason, or if they consume banj and it stops their reason, such people deserve reproach and punishment for the manner in which they have caused their reason to stop. Many of them attract the demonic state of being by doing whatever they like and dancing in an extroverted manner until their reason ceases, or by snorting and bellowing until the demonic state of being comes upon them. Many of them aspire to distraction until they become witless. All such people are of the devil’s party, and this a fact known about more than one of them.Footnote 39

Ibn Taymiyya’s representation of illicit behavior emphasizes several simple themes. Firstly, in the eyes of some legal authorities, a number of behaviors, including the consumption of intoxicants, dancing and either playing or listening to music, were directly linked to demonic possession because they were perceived to hinder rational thought.Footnote 40 It is possible that the Sufi practices of audition (samāʿ) and dance are Ibn Taymiyya’s express target. Secondly, in Ibn Taymiyya’s representation, the idea of demonic possession does not appear to be an extended metaphor, but rather the description of a process that was supposed to occur in the physical world.

Just as Ibn Taymiyya associates aspects of human behavior that he deemed illicit with the presence of demons, a number of the Siāh Qalam paintings develop parallels between human and demonic actions. Thus several images depict people or demons either grinding substances or holding drinking vessels. One painting (H.2153 f.135a) (Figure 4) and another unfinished image (H.2153 f.70a—IA1 fig.290) depict men with a pestle and mortar, while hand-operated querns are used by two demons in another painting in Siāh Qalam style, the Metropolitan Museum’s 68.175 (Figure 7). A further four “Siāh Qalam” images (H.2153 f.34b—IA1 fig.248; H.2153 f.112a—IA1 fig.278; H.2153 f.39b—IA1 fig.209; Freer 37.25—IA1 fig.210) depict demons with either metal or porcelain cups or vessels, and H.2153 f.29b (IA1 fig.477) depicts a man with a cup. While it is true that any number of scenarios can be envisaged concerning what is being ground and what is being drunk in these images, the tropical association between demons and the consumption of intoxicants may lend support to the notion that the substances being prepared and consumed in the paintings are illicit. Contemporary textual discussions of the methods for preparing hashish relate that is was first ground, and that it could be drunk in liquid form.Footnote 41

Figure 7. Metropolitan Museum 68.175.

Source: Image in the Public Domain.

In addition to the Siāh Qalam paintings depicting humans and demons grinding substances and drinking, a number depict the two groups dancing (H.2153 f.64b—fig.3; H.2153 f.34b—IA1 fig.304) playing music (H.2153 f.37b—IA1 fig.311; H.2153 f.112r—IA1 fig.278; Freer 37.25—IA1 fig.210) or brawling (H.2153 f.165b—IA1 fig.212; H.2153 f.109b—IA1 fig.213; H.2153 f.31b—IA1 fig.245; H.2153 f.37a—IA1 fig.307; H.2153 f.37b—IA1 fig.246), all behaviors characterized by some as immoral, and hence conducive to the presence of demons. It is possible that images such as H.2153 f.129b (IA1 fig.249) and H.2153 f.101a (IA1 fig.299), depicting demons carrying off men, engage with the idea of demonic possession that we have seen reflected in the work of Ibn Taymiyya.

The connection between illicit behavior and the demonic can be extended to other paintings in the Siāh Qalam group. The large handscroll depicting frenzied demons dismembering a white horse (H.2153 f.40b) can be compared with an image from India, of a much later date but relatively stable iconography, which makes aspects of the album painting explicit (Figures 1 and 8).Footnote 42 Sold at Sotheby’s New York in May 1982, the painting, given a provenance of nineteenth-century Kotah, depicts a horde of demons feasting. In the foreground, a troop of devils slaughter and dismember animals including a camel, a lion and two rabbits, just as the demons in the Siāh Qalam handscroll rip apart the horse. In the background of the Kotah image, one demon carries grapes, another holds a painted or glazed vessel and a third carries a metal cup, indicating the presence of wine. In the centre ground, two demons filter bhang into a basin through a muslin sheet, a porcelain vessel at their feet. To the left, bhang is being roasted in a cauldron by another couple of demons. In the background, the presence of a human figure with a baby, who is being carried by a demon, invites us to interpret the painting as an evocation of the “demonic” forces at play in the human consumption of intoxicants. Within the overlapping cultural contexts present in India, the image can be understood in different ways—as a satire, or perhaps as a devotional painting, since cannabis consumption is associated with Śiva and Śaivite practicesFootnote 43—but either interpretation is based on the premise that demons and the demonic represent uncontrolled forces that flourish when reason sleeps. I would contend that, like the painting from Kotah, the Siāh Qalam handscroll also engages with ideas concerning the “demonic” nature of the use of intoxicants.Footnote 44

Figure 8. “Demons feasting.” Kotah.

Source: Photograph Courtesy of Sotheby’s Inc. © 1982.

It is possible that another group of the Siāh Qalam paintings represent the experiences of consumers of intoxicants. So-called “red eye” (conjunctival injection), in which the blood vessels on the surface of the sclera dilate, is consistent with the presentation of cannabis consumers, a point that was picked up by a number of writers.Footnote 45 Ibn Sūdūn, again, has a mawāliyā poem on his experiences of taking a hashish pill.Footnote 46

Once I swallowed a green pill

And saw the whites of my eyes covered with red.

I walked through my house and out of it, unawares,

Sensing nothing, inside and outside.

“Red eye” (Pers. chashm-e sorkh) is also mentioned frequently in Divān-e asrāri, a collection of poems on hashish and its users written by Fattāhi Nishāpuri (d. 852/1448, also known as Toffāhi and Sibak).Footnote 47 To give one example from the many:Footnote 48

![]()

We have made the green [hashish] cause redness in eyes and paleness in faces

So that whoever becomes stupefied on taking it is put to shame.

Conjunctival injection is evident in a number of Siāh Qalam paintings. In H.2153 f.64b, two demons with bloodshot eyes dance wildly (Figure 3). H.2153 f.27b depicts demons abusing a donkey, the bloodshot vessels on their eyeballs clearly visible (IA1 fig.276). H.2153 f.39b shows one demon with conjunctival injection offering a kind of metal flask to another demon, the whites of whose eyes are clear, perhaps implying that the contents of the flask are responsible for creating red eye (IA1 fig.209). An image formerly in the Vignier collection depicts a male and a female figure subduing a demon with bloodshot eyes (IA1 fig.295).Footnote 49 Another Siāh Qalam painting depicts six traveling figures (H.2153 f.55a) (Figure 2). That the employment of the color red is not an aspect of style is to be concluded from the fact that the eyes of one of the figures are free from any red coloring. The eyes of the remaining five figures are all red, although in this case the color seems to be concentrated on and around their pupils. While the figure on the donkey stares ahead in a daze, two others look back at what would appear to be one man carrying another, their arms forming a confusing mass, in which it is difficult to distinguish their limbs. I would suggest that the mass of limbs may represent the men’s confused perception, rather than being a technical mistake on the part of the artist.Footnote 50

Finally, there is a scene which has been conceived of by modern scholarship as representing an “encampment” (H.2153 f.8b—IA1 fig.282). The painting depicts a bare patch of land, populated by grazing horses, scrapping dogs, five humans—one of whom is evidently wealthier than the other four—and clustered objects. Some of the objects, such as a saddle, a quiver and flasks, suggest that the group is away from home, and others, like the cauldron and basins, imply that the men have stopped in a rural location. The basins are piled with shapeless white forms. As with representations of objects in the other Siāh Qalam paintings, these shapeless white things can be envisaged in different ways. It has been suggested that they are bundles of fabric and that the men are washing them,Footnote 51 yet while this is possible, the image displays distinct similarities with later Safavid and Mughal representations of “wine and bang” gatherings, held in open, rural spaces and attended by figures from a variety of backgrounds.Footnote 52 Such scenes often include dervish figures alongside men of obvious wealth, and depict the process of filtering bang through muslin into large bowls, or the adulteration of bang with wine. In one such image (MFA Boston 14.649) a male figure in the center of the composition filters bang through a piece of cloth, grasping the folded cloth with two hands, holding it parallel to his chest, and wringing it over a basin (Figure 9). This is done in an identical manner by a figure in the top left of the Siāh Qalam composition who sits on his haunches.

Figure 9. MFA Boston 14.649. Francis Bartlett Donation of 1912 and Picture Fund.

Source: Photograph © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

This is not to argue that all the Siāh Qalam scenes of human activity are supposed to represent the preparation or consumption of intoxicants, and without further evidence such a standpoint cannot be justified in relation to a number of scenes depicting people conversing (e.g. H.2153 f.38b—IA1 fig.296; H.2153 f.52a—IA1 fig.302; H.2153 f.128a—IA1 fig.306) or those of people engaged in construction (e.g. H.2153 f.141b—IA1 fig.308; H.2153 f.33a—IA1 fig.255; possibly H.2153 f.38b—IA1 fig.279). However, even in these scenes, comparisons between human and demonic behavior are still evident. For example, we may wonder why the human craftsmen of H.2153 f.141b are given a parallel in a painting of two demons sawing a tree, which has been pasted onto the a side of the same folio (H.2153 f.141a—IA1 fig.277). Further suggestive parallels include the image of two men who appear to be fighting over a donkey (H.2160 f.14a—IA1 fig.280) and the previously discussed painting of two demons doing the same (H.2153 f.27b—IA1 fig.276).

I would therefore not go so far as to argue that the Siāh Qalam paintings are primarily concerned with the use of intoxicants, but I would suggest that most of the paintings depict a community, real or imagined, some of whose actions, including the consumption of intoxicants, were deemed by onlookers to be ripe for satire. In this regard it is worth noting, along with Robinson, that the word siāh, in addition to its primary meaning of “black,” has the secondary significance of “drunk”;Footnote 53 not only “drunk,” but “intoxicated to the point of being out of one’s mind” (mast tāfeh az khud bi khabar).Footnote 54 The word also means “sinful.” The name Mohammad-e Siāh Qalam may therefore point to an artist with the first name Mohammad, who specialized in the technique of pen-and-ink drawing known as qalam siāhi, but it can also be understood as a joke on the subject matter of the images that he, or those who painted in his manner, produced.Footnote 55

While a distinction should be made between the environment in which the Siāh Qalam paintings were produced and the new contexts created by the selection and arrangement of the images in albums H.2153 and H.2160, there is limited evidence that some of the paintings were understood by the albums’ compilers as engaging with ideas about illicit behavior. On H.2153 f.40b (Figure 1), for example, the scene of demons dismembering a horse is juxtaposed with quotations reflecting ideas and phrasing found in aḥādīth: “Avoidance of the abode of deception is one of the marks of reason … It is an attribute of honor to shun whatever disgraces you and to choose whatever is an ornament to you” (inna min ʿalāmāt al-ʿaql al-tajāfī ʿan dār al-ghurūr … Min al-murūʾa ijtinābuk mā yashīnuk wa ikhtiyāruk mā yazīnuk). On H.2153 f.64b (Figure 3), the image of demons engaged in dancing and audition is juxtaposed with the garbled text of a whispered prayer (munājāh), one of whose verses appeals to ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib as the speaker’s refuge against “the temptation of the self and its accursed demon” (min sharr ghayy nafsī wa shayṭānihā al-rajīm).

Targets of Satire: Moderate and Antinomian Sufis

If the Siāh Qalam paintings can be considered satirical, whom might they satirize? It is relatively difficult to create an objective history of intoxicant usage in the area of our enquiry during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, since the kinds of documentation that the historian would wish for are often absent, no longer extant, or unpublished. Nevertheless, a number of literary and documentary sources in Persian create a general impression that hashish and bang were associated in people’s imaginations with two contexts: that of courtly culture, and that of Sufism in both its “moderate” and antinomian incarnations.Footnote 56 Proverbs reflecting the stereotypical association between Sufis and hashish usage include: “The green leaf [i.e. hashish] is the dervish’s gift,” and Fattāhi’s Divān-e asrāri imagines hashish as the offspring of a founding father of the antinomian Qalandariyyeh movement, Jamāl al-Din Sāveji.Footnote 57

Continuities with literary representations of Sufism may be of relevance for the Siāh Qalam paintings. For example, in the Ten-Chapter Epistle, a collection of intentionally subverted definitions by the often satirical poet and prose-writer ʿObeyd-e Zākāni (d. ca. 770/1370), banj is glossed as “what brings Sufis to ecstasy.”Footnote 58 Other, suggestive definitions from the same work gloss the word sheykh (presumably in the sense of a Sufi sheykh) to mean “the Devil” (Eblis); the Devil’s “deception” (talbis) to mean “the words that [the sheykh] speaks on the nature of the material world”; “temptation” (al-vasvaseh) to mean “what [the sheykh] says concerning the afterlife”; “the demons” (al-sheyātin) to mean the sheykh’s followers.Footnote 59 ʿObeyd’s representation is not the first of its kind. Over a century and a half earlier, the judge and preacher Abu Tāher Yahyā b. Tāher b. ʿOsmān ʿOwfi (active Transoxiana, late twelfth century) lamented in an edifying poem the pernicious influence of men of “Turkic, Byzantine and Indian manners” in Transoxiana, Sufis associated with the ideas of Bāyezid (Bestāmi) (d. 261/874 or 264/877–78), Shebli (d. 334/945) and Joneyd (d. 298/910) who, he claimed, had defiled the city’s mosques and influenced lordly men to take up wine, bang and gambling with dice.Footnote 60

While an intentional stereotype, ʿObeyd’s association between Sufis and illicit behavior may reflect trends in contemporary society. Evidence for this thesis is provided by an extant Jalāyerid decree (farmān), addressed to the administrative heads of the Safavid order at Ardabil.Footnote 61 Written at the insistence of the head of the shrine, the decree, which was issued in 773/1372, orders the administrators to desist from harassing the local villagers and requisitioning their mounts, to stop extorting tax revenue that legally belonged to the state from the local tanners and butchers, and for them and their disciples (moridān) to refrain from introducing forbidden heresies (bidʿat) into the area; prostitution and the consumption of wine are mentioned explicitly.

The accusation of illicit behavior is also leveled by some Sufis against others. In the voluminous hagiography of Safi al-Din Ardabili (d. 935/1334), Safvat al-safāʾ, completed in 759/1358, Ebn Bazzāz (dates uncertain) introduces a number of akhbār about both “moderate” and antinomian Sufis in the Ardabil region, whose impropriety threw the pious conduct of Safi al-Din and his guide (morshed), Sheykh Zāhed, into relief. One figure, Hasan-e Mankali, the deputy and regent of Bābi Yaʿqubiān, is reported to have enjoyed using hashish and to have gathered together a group of qalandars, “unstable” men (muleh) and “similar kinds of people” into a band, whose authority was countered by that of Sheykh Zāhed.Footnote 62

Another narrative from Safvat al-safāʾ takes place in a village called Puruniq, where a man by the name of Mohammad Razinān arrived out of the blue claiming to be a sheykh, enshrining his aura of spiritual authority among the villagers with the prophesy, later confirmed as true, that Soltān Mohammad (i.e. Öljeitü d. 716/1316) had died and Abu Saʿid had been made Ilkhan.Footnote 63 When the matter was brought to the attention of Safi al-Din, he described it as a demonic state of affairs (in hālat-e sheytāni ast), and told his followers to search under Mohammad Razinān’s prayer-mat, where they would surely find a purse of hashish, since Razinān was an addict (nik-khvār). The people believed that Razinān was a miracle-worker (sāheb-e karāmāt) and did not wish to defy him, yet one evening a group gathered the courage to carry out Safi al-Din’s instructions and found that he was correct. With his reputation in tatters, Mohammad Razinān hot-footed it out of the village that night, never to be heard of again.

This literary and documentary evidence can be usefully compared with the Siāh Qalam paintings for several reasons. Firstly, it demonstrates that real-life events could provoke creative responses, which were on the one hand clearly art, but which on the other hand considered the potential of social change. The last narrative, concerning Mohammad Razinān, for example, has obviously literary aspects to it, intentionally or not recalling a maqāma by al-Hamadhānī, yet it forms part of a hagiographical text.Footnote 64 Secondly, the texts bring into sharper relief aspects of social history that have proved a sticking point for the study of the paintings. They demonstrate that “moderate” Sufis, antinomian Sufis such as qalandars, peasant farmers and craftsmen all interacted with one another out of necessity. Indeed, scholarship suggests that, particularly with the rise of the Sufi orders, craftsmen and farmers were often tied to Sufi institutions.Footnote 65 Such scholarship offers one way of bridging the gap between the findings of the researchers who have argued that the human figures represented in the Siāh Qalam paintings are craftsmen and farmers, and of those who have argued that they are “dervishes.”

As studies have highlighted previously, however, it is clear that not just one group is represented in the Siāh Qalam paintings. Several appear only once or twice: H.2153 f.106b depicts two men in the guise of Christian priests;Footnote 66 H.2153 f.37b (IA1 fig.311) and H.2153 f.129b (309) depict qalandars, recognizable as such from their lack of facial or body hair. These men can be distinguished from other kinds of dervishes, who dance, sit on their haunches, argue or converse. Çağman argues that such figures could also be slaves.Footnote 67 Manuals for the purchase of slaves such as al-ʿAynī’s al-Qawl al-sadīd fī ikhtiyār al-imā’ wa l-ʿabīd (A Guide Indispensable to Slaves Male and Female) testify to the variety of peoples sold into slavery in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, including those from western Europe, Byzantium, India, Central Asia, North Africa, Ethiopia and the Red Sea littoral. Since al-ʿAynī discusses the nationalities that he perceived to make for productive members of the ʿolamāʾ, it is evident that non-Muslim slaves could be converted and integrated into religious life.Footnote 68

Aspects of dress also help in the identification of a number of figures represented in the paintings. In H.2153 f.38b (IA1 fig.310), for example, the two dervishes carrying hashish pouches are recognizable from their capes, made from leopard and tiger skins. These capes appear to be the so-called pust-e takht, defined by Dehkhodā as animal skins made from either sheepskin or the fur of lions, leopards and tigers, which dervishes use as a cover or carpet when sitting and sleeping, and which they wear on their backs as they travel.

While leopard and tiger fur clothing are often connected with royal authority, they also have a known association with the claimed spiritual authority of Sufis, as can be seen in a painting from the Bodleian Majāles al-ʿoshshāq, (MS Ouseley Add. 24 f.79b) imagining the dervish followers of the poet Fakhr al-Din ʿErāqi.Footnote 69 The painting depicts men either with the pust-e takht draped over one shoulder, or wearing more stylized leopard and tiger-fur trousers and wraps. One figure wears a hat made of white tiger fur. It is possible that, in certain contexts, hats of tiger or leopard fur are used as a kind of shorthand in painting to designate Sufis as a general class. Such hats are seen in a painting from a manuscript of ʿAttār’s Manteq al-Teyr (Metropolitan Museum 63.210.44) a consciously Sufi text illustrated in this case in the institutionalized Sufi context of late Timurid Herat, and in the frontispiece to Soltān Hoseyn Beyqarā’s copy of the Bostān of Saʿdi that is now in Cairo (Dār al-Kutub, MS Adab Fārisī 908, fols.1b–2a), again an image that represents a courtly environment in which Sufism was cultivated and institutionalized.Footnote 70 Certain textual representations, such as Fattāhi’s Divān-e asrāri, describe pust-pushān (lit. “fur-” or “skin-wearers”) among the classes of Sufis who consume hashish.Footnote 71

If leopard and tiger fur clothing or hats can be understood as a shorthand designating Sufis, this may aid our identification of the figures in the Siāh Qalam paintings, since at least thirteen paintings depict people dressed in this manner.Footnote 72 These include both the “dervish” type, otherwise clothed in very little and depicted sitting on the ground, figures engaged in construction (H.2153 f.141b—IA1 fig.308), and the most common type depicted in the paintings, men wearing full-length outer coats and tall, bell-shaped hats (H.2153 f.141b—IA1 fig.308; H.2153 f.92b—IA1 fig.287; H.2160 f.52a—IA1 fig.292; H.2153 f.105a—IA1 fig.313). Tiger and leopard-fur hats are also seen in two of the larger, polychrome paintings in H.2153: the so-called “Procession” scene (H.2153 fols.3b–4a), and the scene of drunken figures transporting porcelain and metal vessels across a landscape (H.2153 f.130a). H.2153 f.37a (IA1 fig.307) is one of the few Siāh Qalam paintings to depict demons dressed in the garb of the humans. The image depicts two demons, one of whom is clothed in a long, leopard-fur cloak, watching a fight between another two. All four wear the tall hats that are characteristic of the human figures. It is tempting to view this image as further evidence that the demonic figures in the paintings are intended to parody the human ones.

In general, the bell-shaped hats worn by many of the male figures in the paintings are close to those of several Sufi orders, without being sufficiently homogenous to pinpoint one order in particular.Footnote 73 Indeed, the hat worn by one male figure (H.2160 f.10a), ends in a flamboyant finial, suggesting, again, that the garb of these men is intended as a caricatured shorthand (Figure 5). This thesis is supported by a painting now in the Sackler Museum (S86.0061 f.101b), which has been dated to Tabriz ca. 1470, and which depicts a prince prostrating himself before a dervish.Footnote 74 The dervish wears the long outer garment and tall bell-shaped hat with finial seen on the Siāh Qalam figures and, like many of them, he carries a staff.

Despite suggestions to the contrary, it appears unlikely that the men in heavy outer coats and tall hats could be antinomian Sufis, such qalandars or heydaris, whose dress, hair and behavior are generally represented in texts and later images in a uniform way: qalandars are described as being shorn of all facial and bodily hair and dressed in a bare minimum of clothing, and, as already discussed, only a couple of Siāh Qalam paintings depict figures that correspond exactly to this type.Footnote 75 Heydaris lacked beards, cultivated long moustaches, and were infamous for wearing heavy iron rings, including on their genitalia, which they exposed.Footnote 76 It therefore appears less likely that any of the figures represented in the paintings could be Heydaris. The suggestion made by Rogers that some of the men are Russian fur-traders is contradicted by Clavijo’s representation of a delegation to the court of Teymur of Christian fur-traders from the area under the authority of the Golden Horde.Footnote 77 The men are described as being clad in tattered tabards of skins, and as wearing small hats attached by a cord to their chests, the overall effect making them look like “so many blacksmiths who had just left serving the forge.”Footnote 78

If the most common figural type depicted in the Siāh Qalam paintings, the men wearing full-length outer coats and bell-shaped hats, can be considered to caricature “mainstream” Sufis, I would contend that the actions carried out by these figures largely correspond with a field of ideas that we have seen reflected in documentary evidence and satirical literature of the mid-to-late fourteenth century in particular. Despite the lack of background detail given in the Siāh Qalam scenes, the representation of different types of figures across the paintings builds up a compound picture of a social world. Again, the preceding evidence suggests that this picture is not inconsistent with social environments in the fourteenth century. Documents such as the farmān of Soltān Ahmad Jalāyer discussed above, for example, show that more organized forms of Sufism were enmeshed with communities of farmers and tradesmen. Scholars including Jürgen Paul have demonstrated how the rise of Sufi orders in Iran depended on economic coordination with peasants, and Safvat al-safāʾ suggests that Sufis were often involved in building projects and trade in the fourteenth century.Footnote 79

Viewing Contexts

For which kind of contexts may the Siāh Qalam paintings have been produced? The use of a scroll format for a number of the paintings does not necessarily indicate that they were created for recitals or performances, since it could represent a technical experiment with form. It is also possible that images which were initially consumed within performance contexts could have been repurposed and enjoyed within the context of the book, as the albums themselves demonstrate. Nevertheless, it is still tempting to think that some of the paintings may have been used originally either in the context of live theatre, where a speaker could have built a performance around them, or to entertain groups of viewers in the absence of a performer, on account of their large size, the single scene-like nature of each image, and factors such as highlighting in gold, which may have picked up candlelight.Footnote 80 As has been noted often, the physical wear and tear incurred by some of the paintings suggests that they were manhandled frequently.Footnote 81

It has been argued on several occasions that the figures depicted in the Siāh Qalam paintings display similarities with the puppets of shadow theatre.Footnote 82 The argument appears difficult to defend when the paintings are compared with the puppets from Damietta which were published by Paul Kahle, and which have shaped modern scholarship’s understanding of the props used in shadow theatre.Footnote 83 Nor do the figures depicted in the paintings display any great similarity with extant puppets employed in Iranian loʿbeh-bāzi.Footnote 84

That said, while there is no particular reason to assume that the Siāh Qalam paintings must be tied to texts, they do lend themselves to comparison with the structures and farcical themes of some shadow plays, performed texts, and connected genres of writing. For example, the sketches in Ibn Sūdūn’s Nuzha that may have been performed take place in a single setting but introduce several sets of characters.Footnote 85 One sketch revolves around an oneiromancer and his customers in the first half, and around a young man high on hashish, who appears along with his family, in the second half.Footnote 86 Another bipartite sketch focuses on a wedding where the bride and groom have been fed intoxicating substances, and the bride’s younger brother demands to be put in a wedding dress, before being attacked by the guests.Footnote 87 A third consists of an exchange of insults between a hunchback and a group of ẓurafāʾ (“refined” men).Footnote 88 These sketches do not share an obvious plot with the paintings, but what they do have in common is a focus on the farcical interactions of small groups, which are often part of a larger set of circumstances. Just as the plots of the sketches can be structured by repetitive actions, like the interactions between the oneiromancer and each of his clients, so too elements recur from painting to painting. For example, several paintings depict groups of men traveling (H.2153 f.55a—fig.2; H.2153 f.124a—IA1 fig.341; H.2153 f.38b—IA1 fig.279), or figures with livestock (H.2153 f.27b—IA1 fig.276; H.2160 f.14a—IA1 fig.280; H.2153 f.23b—IA1 fig.281; H.2153 f.113a—IA1 fig.316; H.2153 f.38a—IA1 fig.317), or paired figures in conversation (H.2153 f.29b—IA1 fig.297; H.2153 f.106b—IA1 fig.298; H.2153 f.52a—IA1 fig.302).

Demons also appear to satirical effect in some texts that have been connected with performance culture by Shmuel Moreh.Footnote 89 For example, in al-Maʿarrī’s (d. 449/1058) Risālat al-ghufrān, Abū Hadrash, the jinni interviewed by the epistle’s protagonist, shows up faults in human behavior by cataloguing his own misadventures on earth.Footnote 90 In the paintings, figures such as the demon depicted in H.2153 f.48a (IA1 fig.244), who appears to be lecturing or haranguing the viewer, reinforce the impression of a satire on moral standards. If the paintings are to be connected to performance culture, then continuities with the themes and subject matter of plays and performed texts may be more significant than any formal similarities with extant puppets.

Limited documentation survives concerning satirical performance in Iran and the surrounding regions during the period of inquiry, but it is possible to infer that it was practiced. Ibn Dāniyāl (d. 710/1310), whose shadow play ʿAjīb wa gharīb could be described as a satirical representation of street life, was a native of Mosul, leaving that city for Cairo at the age of nineteen.Footnote 91 ʿObeyd-e Zākāni writes of buffoons (maskharegān) being invited to weddings and sessions of audition (samāʿ) in Mongol Iran.Footnote 92 Whether the comedy of their performance derived from them parodying their audience, or performing a “set,” is left unstated; by contrast it is clear that the maskhara in fifteenth-century Cairo consisted of the actor declaiming, while the audience surrounded him.Footnote 93 ʿAlishir Navāʾi’s discussion of story-tellers in his Mahbub al-qulub suggests their presence in late fifteenth-century Herat.Footnote 94 There is also a significant amount of comic poetry which may have been performed in environments such as informal gatherings (majāles). For example, Boshāq Shirāzi, a boon-companion of the Timurid governor of Shiraz, Eskandar Soltān (d. 818/1415), produced intentional travesties of the work of well-known poets, to humorous effect.Footnote 95

The notion that the Siāh Qalam paintings must have been produced entirely outside elite contexts, because they do not represent the ruling classes, may not be accurate.Footnote 96 Satire, parody and misbehavior have a long history as essential elements of courtly culture, including through the representation of the street, an issue of relevance given the interest of the Siāh Qalam paintings in representing life in open, or public, spaces. In a Persian-speaking context, ʿObeyd-e Zākāni, a poet with court affiliations, satirized the bourgeoisie and the urban poor. In an Arabic-speaking context, qaṣā’id sāsāniyya, describing and parodying the life of beggars on the street in often lurid terms, were penned by al-Aḥnaf al-ʿUkbarī (active tenth century) and Abū Dulaf al-Khazrajī (active tenth century) for the same courtly patron, al-Ṣāḥib Ibn ʿAbbād (d. 385/995), and the model was taken up again by Ṣafī al-Dīn al-Ḥillī (d. c. 750/1349) in the fourteenth century to describe the lives of beggars and fraudulent Sufis.Footnote 97 In his qaṣīda, al-Ḥillī caricatures wandering tricksters who could be seen leading the people in their devotions at one time, and urging them to consume hashish and wine at another.Footnote 98

There is also evidence that the boundaries between royal elites and the street were more permeable than is sometimes supposed. The entry on hashish in al-Maqrīzī’s (d. 845/1441) Khiṭāṭ, for example, has a short but revealing passage on Soltān Ahmad Jalāyer:

Until the sultan of Baghdad, Aḥmad b. Uways, arrived in Cairo in his flight from Taymūr Lank in the year 795/1392–93, and his companions (aṣḥābuhu) made a public display of eating it [i.e. hashish], and the people (al-nās) pilloried them for it, found their behavior disgraceful and decried them. Then when he traveled from Cairo to Baghdad, left there a second time, and settled in Damascus for a while, the populace (ahl) of Damascus learned to make a display of consuming it (al-taẓāhur bihā) from his companions.Footnote 99

Al-Maqrīzī’s comments are intriguing because they suggest that, in the case of Soltān Ahmad Jalāyer, there was a degree of interaction between the royal retinue and the broader public, in this case in both Cairo and Damascus. The passage calls into question the notion that the Siāh Qalam paintings cannot have been produced for a courtly audience on the grounds that they do not represent royal subjects, both because it suggests that there was a degree of interaction between the people who made up a court and the inhabitants of cities, and because it reminds us that rulers and courtiers themselves were not always (or perhaps even primarily) interested in the rarefied and the serious.Footnote 100 Further evidence for interaction between royal retinues and the urban poor is provided by the historian al-Ghiyāth al-Baghdādī, who reports that Soltān Ahmad Jalāyer constructed a lodge for Qalandars (al-qalandarkhāna) above the bank of the Tigris in Baghdad, and that this building was used for a marriage by the royal gholām Bakhshāʾesh in the year 813/1410.Footnote 101 Since we can infer a degree of social interaction between courts and Sufi groups, and since the boundaries between courtly and popular culture may have been blurred at certain times, the paintings could be viewed less as an absolute condemnation of popular practices and more as a drier mockery of trends with which both courtiers and laymen would have been familiar.

Conclusion

Scholars once ascribed the Siāh Qalam paintings to the periphery of the Islamic world because the images were perceived to document a culture that was both socially and religiously marginal. This paper has suggested the inverse: that they satirize trends which were widespread in society, which some political and legal authorities attempted to control, and which were sufficiently stereotyped in their own time to be caricatured in contemporary prose and poetry. The interest of the paintings in life on the street places them by no means outside the scope of interests of courtly patrons, since evidence suggests both that courtiers interacted with the broader public, and that parodies of street life were a distinctive aspect of performed texts and theatre, particularly in medieval Arabic culture. One may speculate that certain dynasties, such as the Jalāyerids, who patronized cultural production in both Arabic and Persian, may have been more likely to support such works of art, but until more research is conducted on the culture of linguistically “mixed” environments like Jalāyerid Iraq, such a conclusion risks begging the question.

The Siāh Qalam paintings appear to be more a genre than the work of a single artist, and the history of their production, copying, broader dissemination and re-copying may reflect the collection, diffusion and use of an artistic corpus over a significant period of time. That said, satires of both mainstream and antinomian Sufis may have assumed a particular relevance when the social and political instability created by the Mongol invasions had begun to augment the popularity and visibility of dervish groups and their sheykhs. Increasingly close ties between states and Sufi organizations over the course of the fifteenth century would not necessarily have rendered the paintings unfunny to audiences, but they may have altered what about them was considered humorous. Hence the documentary and literary evidence may reinforce the arguments of a number of historians of art, to the effect that a central group of the paintings should be seen within the context of the late fourteenth century, and that Turkmen artists in the fifteenth century built on the corpus. I would suggest that greater sensitivity on the part of scholars to the questions of what was found amusing in late medieval culture, and why, will help to further unravel what these paintings are about, and to pinpoint the environments in which they may been produced.

ORCID

James White http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3385-6134