Introduction

One of the most intriguing anthropological and archaeological questions concerns the peopling of the Americas. During humans’ dispersal around the globe (Bellwood Reference Bellwood2014), this was the final landmass to be colonised, during the Late Pleistocene. Leaving aside the debates about the exact start date of this process (Meltzer Reference Meltzer and Bellwood2014), we can accept that the New World was inhabited from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego during the transition from the Pleistocene to the Holocene, c. 10 000 uncalibrated years ago (10.0 kya hereafter) or c. 11 700 calibrated years ago (11.7 kya) (Walker et al. Reference Walker2018). At that time, the Clovis phenomenon was one of the most notable technological facets (Haynes Reference Haynes2002), sharing many features with Upper Palaeolithic lithic technologies, which date from c. 50.0/40.0 kya to c. 10.0 kya. Clovis is ascribed to early North American hunter-gatherers and is characterised by distinctive fluted points, broadly distributed from the ice sheets of southern Canada to northern Mexico, and from the Pacific to the Atlantic coasts (Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Collins and Hemmings2010). Allied to this are similar ‘fishtail’ or Fell points (named after Fell's Cave in southern Patagonia, Chile), whose origin has traditionally been related to classic Clovis (e.g. Morrow & Morrow Reference Morrow and Morrow1999). Initially, it was thought that Fell points spread from southern Central America to the southern tip of South America (e.g. Bird & Cooke Reference Bird and Cooke1979; Nami Reference Nami, Farias and Lourdeau2014a), but recent research has shown that they share strong techno-morphological similarities with eastern North American fishtail points, which are found throughout the Gulf of Mexico, the south-eastern United States and probably further north. Further south, they are encountered throughout Central America to at least northern South America and possibly even south of the Equator (Nami Reference Nami2021a). Uncalibrated radiocarbon dates indicate that Clovis spans c. 11.2–10.8 kya (Waters & Stafford Reference Waters and Stafford2007), although Prasciunas & Surovell (Reference Prasciunas, Surovell, Smallwood and Hennings2015) have proposed a longer chronology, coeval with other Palaeoindian points. The Fell point chronological window ranges between c. 11.0 and 10.0 kya (Nami Reference Nami2017a, Reference Nami2019, Reference Nami2021a).

The ‘Southern Cone’ of South America comprises Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay and southern Brazil. Records of Fell points are notably concentrated in the eastern-central part of this region (Nami Reference Nami, Farias and Lourdeau2014a; Loponte et al. Reference Loponte, Okumura and Carbonera2016; Weitzel et al. Reference Weitzel, Mazzia and Flegenheimer2018). To investigate human migration routes and colonisation events, and later socio-cultural developments in the New World, my research has focused on understanding the diverse Terminal Pleistocene/Early Holocene (≤11.0–9.0/8.0 kya) lithic technologies found across the Americas (e.g. Nami Reference Nami2017b, Reference Nami2020; Nami & Yataco Capcha Reference Nami and Capcha2020). Here, I present new data from the south-western part of the Merín Lagoon in north-eastern Uruguay that sheds light on the early peopling of this region.

Background

The increasing body of information regarding the first settlement of the Americas shows that the process was complex, with different colonisation events reflected in technological and adaptive diversity (e.g. Goebel et al. Reference Goebel, Waters and O'Rourke2008; Potter et al. Reference Potter2018). As outlined above, hunter-gatherers using North American ‘fishtail’ points may have peopled South America. The locations of Palaeoindian finds in Central and South America suggest that such peopling may have followed a western route along the ‘Pacific Slope’, and another route in the east, following the exposed Caribbean continental shelf and the nearby inland territories (Nami Reference Nami2021a). The areas surrounding the Atlantic coast and its continental shelf may have played a significant role in this process (Nami Reference Nami2016, Reference Nami2021a). The discovery of submerged Palaeoindian sites in Florida (USA) and Mexico (e.g. Faught Reference Faught2004; MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald2020) supports this interpretation, as do finds of fishtail points from Margarita Island (Venezuela), which was probably joined to the continent via the exposed Atlantic shelf during the Late Pleistocene (Nami Reference Nami2016). Given these indications, and the fact that many Fell point sites and finds are located in the ‘Southern Cone’ of South America, the study of Palaeoindian evidence from locales near the Atlantic seaboard is particularly significant.

Geology and archaeology of Merín Lagoon

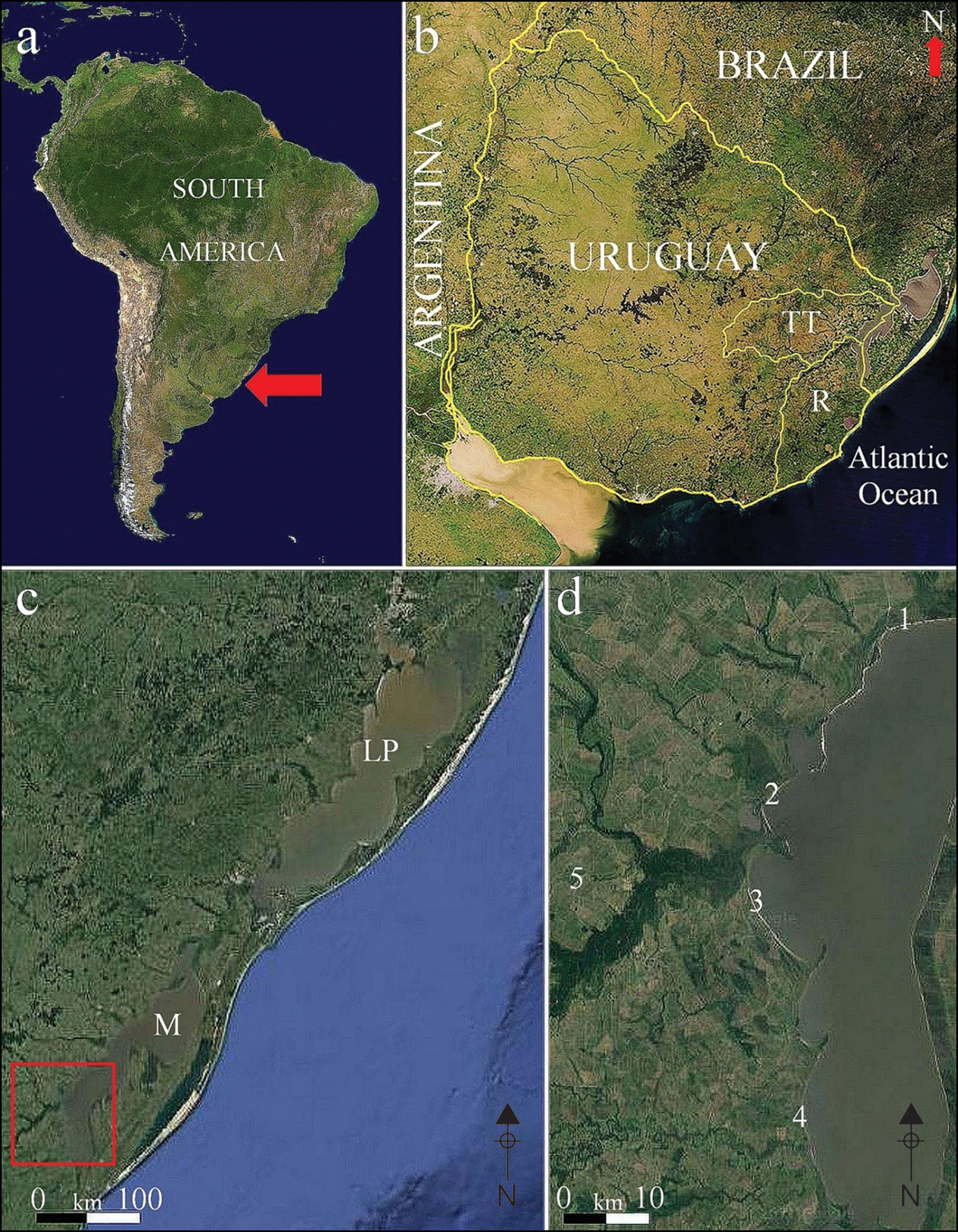

The Merín Lagoon (32°45′00″S, 52°50′00″W) is an estuarine freshwater lake located on Brazil's southern border with Uruguay (Figure 1). It is the oldest in a chain of lagoons along the Atlantic shoreline. The remnant of an ancient coastal depression, enclosed by sand beaches formed by the combined action of wind and oceanic currents, the Merín Lagoon is separated from the ocean by a sandy and partially barren isthmus (Achkar et al. Reference Achkar, Dominguez and Pesce2012). After Lake Titicaca in the Andes, it is the second largest lake in South America. Its surface of 3750km2 extends from the southern Rio Grande do Sul state in southern Brazil to north-eastern Uruguay, where its south-western shore is shared by the Departments of Cerro Largo, Treinta y Tres and Rocha (marked TT and R on Figure 1b). The rivers Tacuarí, Cebollatí and Yaguarón drain into the Merín Lagoon.

Figure 1. a) Map of South America and location of Uruguay, as indicated with an arrow; b) Treinta y Tres (TT) and Rocha (R) Departments; c–d) location of the Los Patos (LP) and Merín (M) lagoons. The red square in (c) denotes the portion of Merín Lagoon where the analysed points were recovered. The numbers in (d) refer to the locales mentioned in Table 1 (modified by H.G. Nami from NASA and Google Maps).

Supporting the same or similar faunal resources from the Terminal Pleistocene to the present, most of southern Brazil, Uruguay and the submerged continental shelf form part of the same biome (Adams & Faure Reference Adams and Faure1997; Gallo et al. Reference Gallo, Avilla, Pereira and Absolon2009; Ubilla et al. Reference Ubilla and Perea2011; Pereira Lopez et al. Reference Pereira Lopes2020). The region is also characterised by its shared geology and geography, as well as archaeological record (López-Mazz Reference López Mazz2013; Loponte et al. Reference Loponte, Okumura and Carbonera2016; Moreno da Souza Reference Moreno da Sousa and Ono2020; Nami Reference Nami2020). The geomorphological development of the region has been shaped by phenomena such as Terminal Pleistocene and Holocene tectonics, isostasy and sea-level oscillations (Ayup-Zouain Reference Ayup-Zouain, Menafra, Rodríguez, Scarabino and Conde2006; Bossi & Ortiz Reference Bossi, Ortiz and García Rodríguez2011; Bracco Boksar et al. Reference Bracco Boksar and García-Rodríguez2011; Martínez & Rojas Reference Martínez and Rojas2013). The Santa Lucía-Aiguá-Merín Lagoon Tectonic Corridor—a fault running north-east to south-west—is also significant for the formation of the Merín Lagoon (Bossi & Ortiz Reference Bossi, Ortiz and García Rodríguez2011; Panario & Gutiérrez Reference Panario, Gutiérrez and Rodríguez2011; Loureiro & Sánchez Bettucci Reference Loureiro and Sánchez Bettucci2019). After the Last Glacial Maximum, the volume of ice decreased by approximately 10 per cent within a few hundred years (Yokoyama et al. Reference Yokoyama2000). Starting at approximately 120m below its current level in southern Brazil and Uruguay, the sea level rose, beginning c. 17.5 kya and ending c. 6.0 kya. Since the Middle Holocene, with a subsequent increase until c. 5.0–4.5 kya, the region has been largely submerged by the sea due to glacioeustasy (sea-level fluctuations caused by melting ice) (Bracco Boksar et al. Reference Bracco Boksar and García-Rodríguez2011; Martínez & Rojas Reference Martínez and Rojas2013).

The ubiquitous Holocene anthropogenic mounds—used as settlement occupation, agricultural platforms, landmarks places and cemeteries from c. 4.5–2.5 kya (pre-ceramic) to historical (ceramic) times—and their remarkable record make this an archaeologically prolific region (López Mazz Reference López Mazz2001; Iriarte Reference Iriarte2006; Bracco Boksar et al. Reference Bracco Boksar, del Puerto, Inda, Loponte and Acosta2008). The evidence for the presence of Late Pleistocene human occupation, on the other hand, has been elusive. The following section provides an overview of the Palaeoindian evidence found in this region.

Materials, analysis and results

The 17 Fell points from Merín Lagoon presented here are curated in private and museum collections. Fourteen specimens currently held in the Marcel Machado and Rubén Rodríguez-Mary Lago collections in Treinta y Tres city were available for analysis. Archaeologist A. Florines kindly provided data on a further three Fell points from the photographic archives of the pioneer archaeologist Jorge O. Femenías (1948–2007). These had been collected by O. Prieto and are currently exhibited in the Museo Antropológico del Municipio de Vergara; permission to access them has not been forthcoming.

The 17 points were found in the Treinta y Tres and Rocha Departments (Figure 1c–d). Except for one isolated Fell point discovered inland, they were all recovered from the Uruguayan shore of the lagoon. A brief description of provenance from north to south is given in Table 1.

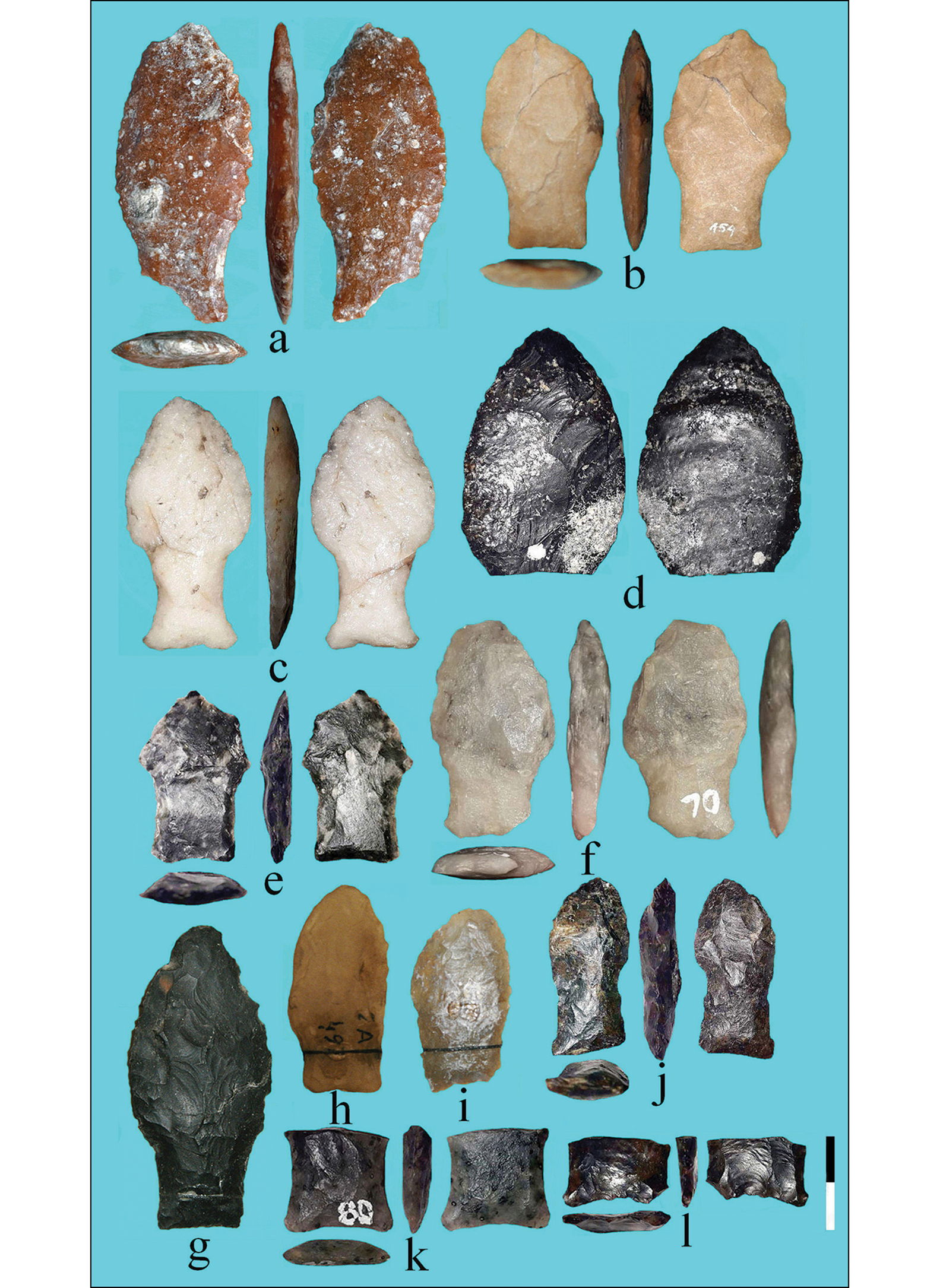

Table 1. Sites that yielded Fell points in the study area.

The Fell points are all surface finds; a visit to the find spots (Figure 2) revealed the presence of other mixed Late Pleistocene and Holocene material. This mixing is caused by water and wind erosion on the lagoon's shoreline. Most finds come from the lagoon's sandy beach; however, a grey clayey deposit containing Late Pleistocene fossil remains is exposed in some locations. The surface finds comprise diverse lithic and ceramic artefacts, including zoomorphic ceramics (c. ≤2.5 kya), as well as the remains of extinct and extant fauna. The thick, bony plates of the heavily armoured mammal Glyptodon and remains of Cervidae—probably Antifer sp.—are among the Late Pleistocene bones, indicating that now extinct mega-mammals lived in the region (Pereira Lopes & Sekiguchi Buchmann Reference Pereira Lopes and Sekiguchi Buchmann2011; Ubilla et al. Reference Ubilla and Perea2011; Pereira Lopes et al. Reference Pereira Lopes2020).

Figure 2. The Merín Lagoon coast at Paraje Ayala (a) and Paraje Saglia (b) (photographs by H.G. Nami).

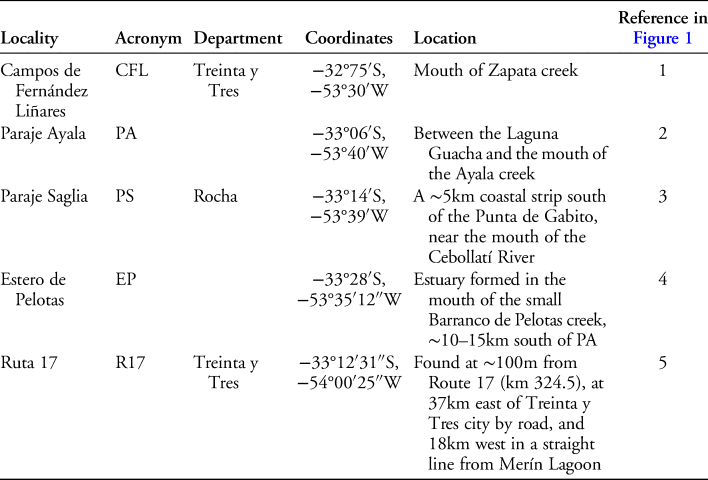

Each Fell point illustrated in Figures 3–5 and detailed in Table 2 was analysed from a morpho-technological perspective. The stone used in their production was of different quality. High-quality flint-like material was most frequently employed, and, like many Holocene stemmed points from the area (Figure 6), several were produced from a homogeneous, vitreous, black material. Flakes experimentally taken from several pieces of waste material revealed a fresh fracture with an aphanitic texture (i.e. with small crystals) on its external surfaces (Howard Reference Howard2002). Comparable in appearance with the black flint found in northern Europe (Nami Reference Nami2015b), this siliceous Uruguayan rock develops a glossy, desert varnish-like patina when exposed to a sandy and watery environment.

Figure 3. Fell points from the studied area, front and back (scale in cm) (photographs a–f by H.G. Nami; g–i by J.O. Femenías).

Figure 4. Fell points from Merín Lagoon, front and back (scale in cm) (photographs by H.G. Nami).

Figure 5. Fell points from Merín Lagoon: a) fluted preform; b–c) close-up of platform preparation for fluting; d) edge-to-edge flaking (photographs by H.G. Nami).

Figure 6. Holocene projectile points from the south of the Merín Lagoon area, made with black chert and red silcrete: a) from Uruguay (photographs by H.G. Nami); b–c) from Brazil, showing the Holocene deposit findspot in (b) (photographs by R. Pereira Lopes) (a–b: scale in cm; c: not to scale).

Table 2. The Fell points reported in this article. Undet. = undetermined. Numbers in parentheses indicate the measurements of the fractured parts.

* J. Femenías's archives of finds from Merín Lagoon, not analysed.

This siliceous material was used to produce stone tools (A. Florines pers. comm.), including Fell points, at Cerro Lago to the north of Treinta y Tres (Nami Reference Nami2015a: fig. 3j). As with one point made with silcrete (see below), projectile points manufactured using this black material were recorded on the Brazilian side of the Merín Lagoon (Figure 6b–c; R. Pereira Lopes pers. comm.). Although the raw material's precise origin is unknown, its limited distribution suggests regional availability associated with the mineral resources of the Merín Lagoon sedimentary basin that exist in the Puerto Gómez Formation (i.e. volcanic fill with interspersed deposits of varied lithology) (Muzio Reference Muzio, Veroslavsky, Ubilla and Martínez2004). The debris and tool blanks recovered show that the base material consisted of thin, tabular nodules. Another flint-like material that was used is silcrete. Outcrops of silcrete are located some 200–400km distant, in mid-western Uruguay (Nami Reference Nami2017a). One specimen was made on milky quartz, and another used a similar rock of fine-grained, saccharoidal texture (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Morrison and Jaireth1995). There are outcrops of xenomorphic (veined) quartz a few kilometres west of Merín Lagoon.

All of the Fell points consist of blades with convex edges; the shoulders can be rounded or straight. Although there are some stems with straight edges and bases, most are concave with ground edges. An image of point 6 has previously been published (Nami et al. Reference Nami, Florines and Toscano2018: fig. 7a–b) but here its techno-morphological details are given. Like points from neighbouring locales (Nami Reference Nami2015a), and many other Brazilian points (Loponte et al. Reference Loponte, Okumura and Carbonera2016), it lacks the typical rounded stem's basal corners, instead exhibiting subtly pointed ‘ears’. As on sites where they were first identified (Bird Reference Bird1969), the points discussed here progress from wide to narrow in the gradation of the blades’ form (Nami Reference Nami, Farias and Lourdeau2014a), conforming to stemmed variants with broad to lanceolate blades (e.g. Figure 3a & g).

While several examples exhibit resharpening that removed traces of their manufacture, point 7 (Figure 3d) was shaped with steep pressure flaking on a thin, angular flake with visible dorsal and ventral faces; non-patterned pressure flaking, however, is observed in most cases. Six specimens are fluted on one or both faces (Figure 3a, e, f & l; Figure 4a & e); the fluting of broken point 3 (Figure 3f) is 25.2mm long and runs over the stem. The remaining bases were shaped by short (≤5mm) (e.g. Figure 3k) and deep (≥5mm) (e.g. Figures 3b & 4c) pressure flaking. Whatever the treatment of the bases, most stems were finalised carefully, with their edges and bases finished mainly after the fluting was completed. Point 1, however, is an extensively resharpened, finished exemplar but without the careful final shaping of the stem's base. This shows that no further work was undertaken on the bevelled platform—a feature also seen in other Uruguayan Fell points (Nami Reference Nami2017a; at this point, I was uncertain whether the points were broken when unfinished or when finished). The new evidence suggests that the base was sometimes not carefully shaped after fluting. Point 3 provides new data regarding the platform preparation required to detach edge-to-edge and overshot flakes. To achieve this, a 60° bevel was made (Figure 5d). Similar examples of both fluting and edge-to-edge detachment on the same object are rare in South America (Nami Reference Nami, Farias and Lourdeau2014b, Reference Nami2021a, Reference Nami2021b).

The presence of a basal portion of a black chert preform (Figure 5a), broken by a reverse hinge fracture during fluting (Nichols Reference Nichols1970; Callahan Reference Callahan1979), is noteworthy. It has flake scars with flat initiations, resulting from flakes with diffuse bulbs. Based on experiments using similar materials, it is possible that such flakes were produced using soft or semi-soft mineral or organic implements (Callahan Reference Callahan1979). These types of finds are rare; several preforms similar to the Merín Lagoon example have parallel edges and bevelled bases, some with isolated nipples for fluting (e.g. Nami Reference Nami2020, Reference Nami2021b). Similar platform preparation used in Fell-point production has been recorded across South America (e.g. Nami Reference Nami, Farias and Lourdeau2014b, Reference Nami2016; Hermo et al. Reference Hermo, Terranova and Miotti2015). Point 8 (Figure 4d) may also have been a preform, given its plano-convex section and rough shaping by random percussion flaking, mostly on one face.

Several examples exhibit diverse fracture types. Experimental research suggests that the transverse breaks on points 13 (Figure 4b) and 11 (Figure 4c)—approximately across the middle, the stem and the blade stem/blade junction—were probably caused by impact when used as an armature tip (Dumbar Reference Dumbar2012; Weitzel et al. Reference Weitzel, Flegenheimer, Colombo and Martínez2014; Nami Reference Nami2019, Reference Nami2020). As observed on numerous Fell points (Bird Reference Bird1969; Böeda et al. Reference Boëda2021), oblique fractures at the base of the stem (Figure 3a) were also produced by impact (Weitzel et al. Reference Weitzel, Flegenheimer, Colombo and Martínez2014).

Among the complete or almost complete artefacts (Figure 3b, c, f & g–j; Figure 4a), most show evidence of resharpening and repair, as is typical for bifacial implements (Goodyear Reference Goodyear1974; Wheat Reference Wheat, Raymond, Loveseth, Arnold and Reardon1976, Reference Wheat1979; Callahan Reference Callahan1981; Nami Reference Nami1989/1990; Towner & Warburton Reference Towner and Warburton1990; Andrefsky, Jr. Reference Andrefsky2009; Kuhn & Miller Reference Kuhn, Miller, Goodale and Andrefsky2015). In Fell points, resharpening is documented by substantial modification to the blade's form and symmetry, by a change in the retouch from its original pattern, or by strongly rounded or concave edges; a type of repair generally made—but not always—when the point was still hafted (Nami Reference Nami2013). In contrast to unmodified Fell points (Bird Reference Bird1969; Nami Reference Nami, Farias and Lourdeau2014a; Loponte et al. Reference Loponte, Okumura and Carbonera2016), several of our points were highly reworked (Figure 3e & j; Figure 4a), as also attested by other examples from Central and South America showing extensive resharpening (Bird & Cooke Reference Bird and Cooke1979; Nami Reference Nami2013, Reference Nami, Farias and Lourdeau2014b; Weizel et al. Reference Weitzel, Mazzia and Flegenheimer2018). If they were still hafted when resharpened, this implies a curated behaviour regarding the technical system that was used (Nami Reference Nami2013). The asymmetrically reworked blades in points 2 (Figure 3j) and 17 (Figure 3i) suggest that they were reworked for a different purpose, such as for cutting activities—as observed elsewhere in South America (Nami Reference Nami2015a). Point 16 (Figure 3h) resembles a rounded Fell point whose flake scars were probably obliterated by intense erosion. As discussed below, this feature may have been produced by marine influx into the Merín Lagoon over several millennia.

Discussion

The data from north-eastern Uruguay presented here contribute to our understanding of Palaeoindian occupation and to the debate surrounding the dispersal of early humans in South America. The lands currently covered by the Merín Lagoon were inhabited by humans during the Pleistocene–Holocene transition. Except in a few cases, the materials featured in the sample analysed here differ from those employed to make Fell points in the wider region. As in neighbouring areas (e.g. Nami Reference Nami2017a, Reference Nami2020; Carbonera & Loponte Reference Carbonera. and Loponte2021) and many other localities in South America (e.g. Bird Reference Bird1969; Nami Reference Nami, Farias and Lourdeau2014a, Reference Nami2019; Méndez et al. Reference Méndez2018), these new findings confirm previous assessments that Fell points were produced locally using locally available materials. This supports the hypothesis that, for basic resources such as stone, wood and some animals, the hunter-gatherers who made the Fell points familiarised themselves rapidly with their local habitats (Meltzer Reference Meltzer, Barton, Clark, Yesner and Pearson2004). Nevertheless, the use of exotic silcrete suggests some type of early networking that enabled social relationships and/or group mobility. The use of red silcrete for point 10 (Figure 3a) also suggests intentional selection, perhaps for colour (Colombo & Flegenheimer Reference Colombo and Flegenheimer2013; Nami Reference Nami2017a). It is notable that the material used to produce the point found at the Apiaí site (São Paulo State, southern Brazil) comes from the Itaoca area, located approximately 200km further west (Collet Reference Collet1980; D. Loponte pers. comm.). It therefore appears that such distances fell within possible mobility ranges, or that early foragers maintained contact with other groups within those ranges. Leaving aside the intensively resharpened and broken Fell points, and some early stages of bifacial reduction, it seems that the implements analysed predominantly reflect the repair of projectile points. The points were mostly used until they could no longer be resharpened; the intact examples demonstrate different degrees of resharpening, possibly some as a result of reuse for other purposes. This implies that these ‘techno-units’ (Oswalt Reference Oswalt1976) formed part of highly curated technical systems (Nami Reference Nami2013).

In terms of distribution and frequency, Bosch et al. (Reference Bosch, Femenías and Olivera1980: point no. 27) mention only one Fell point made on black chert from the Uruguayan side of the lagoon; from the Brazilian side, Prous (Reference Prous1992) and Loponte et al. (Reference Loponte, Carbonera and Silvestre2015) have reported an additional example. Information on precise origin and techno-morphological features of these two points, however, is missing, as are drawings or photographs. Although its provenance is doubtful, I have been informed that another Fell point held at the Museo del Indio y la Megafauna (Maldonado Department) was also recovered from the Merín Lagoon (Nami Reference Nami2015a: fig. 4e). Given these scarce indications, the discoveries reported here deserve particular attention, as they contribute to our knowledge of the earliest regional hunter-gatherer occupation of the Merín Lagoon, complement the evidence from neighbouring areas, and show a widespread distribution within this part of South America (Nami Reference Nami2015a; Nami et al. Reference Nami, Florines and Toscano2018). Significantly, the Merín Lagoon finds are located at a similar latitude to the Negro River Basin, which has yielded the most Fell points to date in western-central Uruguay (Bosch et al. Reference Bosch, Femenías and Olivera1980; Nami Reference Nami2007, Reference Nami2013, Reference Nami2017a).

Within the study area, archaeological research has concluded that humans inhabited the plains surrounding the chain of lagoons c. 5.0 kya—habitation that was influenced by Middle Holocene sea-level changes (Bracco Boksar et al. Reference Bracco Boksar and García-Rodríguez2011). A similar scenario may also have occurred in the Late Pleistocene, during Palaeoindian times. The points presented here were deposited around 10–11 kya in areas that were flooded after c. 8 kya and re-exposed after 5 kya (cf. Bracco Boksar et al. Reference Bracco Boksar, del Puerto, Inda, Loponte and Acosta2008, Reference Bracco Boksar and García-Rodríguez2011; Martínez & Rojas Reference Martínez and Rojas2013; Pereira Lopes et al. Reference Pereira Lopes2020; R. Pereira Lopes pers. comm.). The Fell points reported here are therefore significant because they survived the geological impacts on the pre-mounds archaeological record. The evidence demonstrated that, during the last millennium of the Pleistocene, hunter-gatherers lived near the Atlantic coastline and probably on the still-exposed continental shelf, which comprised a large plain with several rivers flowing into the Atlantic. During the Last Glacial Maximum in particular, when the sea was 100m below present-day level, the hypothetical level of the area of water occupied by the Merín Lagoon was approximately 4m lower than the present-day sea level. During the time in which Fell points were used, the sea level was 60/70m below its present position (Barboza et al. Reference Barboza2021: fig. 2) and the area of the Last Glacial Maximum continental shelf decreased by approximately one half. The Fell points finds spots were therefore far from the hypothetical Merín Lagoon's coastline at that time. Figure 7 shows the hypothetical Merín Lagoon at c. 10–11 kya and the location of the sites illustrated in Figure 1 (based on a map related to the Late Pleistocene palaeogeography, as proposed by Pereira Lopes et al. (Reference Pereira Lopes2020: fig. 1)).

Figure 7. Map of the hypothetical Merín Lagoon at c. 10–11 kya and location of the sites listed in Table 1 (figure courtesy of R. Pereira Lopes).

This scenario may be more important than previously thought. Near the Merín Lagoon, on the current Atlantic coast of southern Brazil, fishermen have collected Late Pleistocene palaeontological remains at depths of approximately 20m. These finds suggest fossiliferous deposits developed during low stand periods that were subsequently submerged and reworked by rising sea levels (Pereira Lopes & Sekiguchi Buchmann Reference Pereira Lopes and Sekiguchi Buchmann2011; Pereira Lopes et al. Reference Pereira Lopes2020). The fossil findings indicate that these lands may not only have accommodated fauna: the presence of open plains, important fluvial courses, animals and other resources would have been sufficiently attractive to hunter-gatherers. Isotope values obtained from Late Pleistocene bones suggest a predominantly arid/semi-arid environment, with grasses, shrubs and tree vegetation (Czerwonogora et al. Reference Czerwonogora, Fariña and Tonni2011; Bocherens et al. Reference Bocherens2017; Loponte & Corriale Reference Loponte and Corriale2019; Nami et al. Reference Nami, Chichkoyan, Trindade and Lanata2020). Furthermore, in southern Brazil and north-eastern Uruguay, the sea-level rise and retreat—mainly between 8/7 and 4.5 kya—formed the chain of lagoons. Environmental changes caused by the development of these lagoons would have severely affected the archaeological evidence for an early human presence, primarily in the area of the Los Patos/Merín Lagoons, as well as the Atlantic coast and its continental shelf. The evidence presented here, along with other data from small lagoons in eastern Uruguay (e.g. López Mazz Reference López Mazz2013; Nami Reference Nami2015a), indicates that at least a portion of this environment was inhabited by Fell point makers. This has implications for discussions of human dispersal in this part of South America, with the Atlantic corridor playing an important role. Indeed, in southern Brazil, most Fell points have been discovered in a strip along the coastline (Carbonera & Loponte Reference Carbonera. and Loponte2021). This, and the data presented here from the Merín Lagoon, suggest that colonisation might have followed the Atlantic coastline. It is therefore worth examining Fell points for evidence of submersion and water erosion over several millennia.

Conclusion

This article provides new information regarding Palaeoindian occupation in the region covered by the south-western part of the Merín Lagoon. It increases the number of known Fell points and presents further insights into their morpho-technology and resource variability, advancing our understanding of the distribution of Terminal Pleistocene forager groups in a largely undocumented territory. The finds from the Merín Lagoon highlight the significance of the Atlantic corridor for the mobility of the early groups that colonised south-eastern South America during the Terminal Pleistocene, while also illuminating the presence and dispersal of humans along the Atlantic shoreline, and advancing discussion of a possible entry point for early colonisation.

Acknowledgements

My special thanks to: A. Florines and D. Loponte for their kindness and valuable help; F. Moreira, M. Machado and L. Caraballo for their cooperation and support during my research trip; R. Rodriguez, M. Lago and M. Machado for their cooperation and for allowing me to study their collections; R. Pereira Lopes for kindly providing the photographs in Figure 6b–c and designing Figure 7; and F. and S. Winn for improving an early draft of this article.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial and not-for-profit sectors.