Introduction

Anthropologists no more believe in the idea of bounded and steady cultural ‘wholes’ rather they take traditions and ‘cultural diversity’ as political and juristic reality. Globalization is resulting in an interdependent world (Boutros-Ghali, Reference Boutros-Ghali1992). The economic, political and social relationships are beyond territorial boundaries (Triandis, Reference Triandis2006), and it has much to do with its influence on cultures (McCorquodale & Fairbrother, Reference McCorquodale and Fairbrother1999; Watson & Weaver, Reference Watson and Weaver2003). The miniature view of the world’s seven billion population shrunk to a workplace of 100 people will have 61 employees from Asia, 15 from Africa, 14 from America and 10 from Europe. On the religious side, 33 of them will believe in the Church, 22 will be Muslims, 14 Hindus, 7 Buddhists and only 12 will be atheists (Erickson & Vonk, Reference Erickson and Vonk2012). When the world is viewed from such a squashed point of view, the value of mutual acceptance and collaboration at work becomes absolutely clear. It is claimed that globalization cannot accomplish its goals if it is not guided by morality (Steger & Roy, Reference Steger and Roy2010).

There is a general conception that Islam, predominantly preaches social interdependence and collectivism at workplace, and individual rights are not given due importance (Ahmad, Reference Ahmad2011). Work ethic is an essential part of Muslim faith (Azmi, Reference Azmi2005), and Islamic sociology establishes a balance between collectivism and individualism by creating harmony between society and the individual. Everyone enjoys his freedom of earning livelihood and doing a lawful business. While on the other hand, it promotes collective well-being of the society and establishes ‘Zakat’ (donating a specific part of one’s possessions every year to the specified poor people) as one of the five pillars of Islamic faith (Sulaiman, Reference Sulaiman2003). Moral conduct at multinational corporations (MNCs) has gained huge significance (Novicevic, Buckley, Harvey, Halbesleben, & Rosiers, Reference Novicevic, Buckley, Harvey, Halbesleben and Rosiers2003; Küng, Reference Küng2009; Tian, Liu, & Fan, Reference Tian, Liu and Fan2015), and it is argued that the workplace needs shared ethics to ignite the true productive potential of human resource (Furnham & Muhiudeen, Reference Furnham and Muhiudeen1984; Niles, Reference Niles1999; Arsalan, Reference Arslan2000; Azmi, Reference Azmi2005). The virtues of global work ethics have been considered widely (e.g., Furnham & Muhiudeen, Reference Furnham and Muhiudeen1984; Ali & Gibbs, Reference Ali and Gibbs1998; Niles, Reference Niles1999; Yousef, Reference Yousef2000; Küng, Reference Küng2009; Tabish, Reference Tabish2009), and how individualism at workplace is one of the main cultural issues (e.g., Ahmad, Reference Ahmad1976; Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1984; Ali, Reference Ali1992; Ali, Falcone, & Azim Reference Ali, Falcone and Azim1995; Triandis & Bhawuk, Reference Triandis and Bhawuk1997; Stefanidis & Banai, Reference Stefanidis and Banai2014). Nevertheless, limited research has been conducted to explore the efficacy of Islamic work ethics (IWE) and individualism (IND) at the globalized workplace.

This paper linked IWE and IND at globalized workplace in four countries. Particularly, it probed two inquiries into this relationship: whether (a) employee religious orientation of being Christian, Hindu, or Muslim, and (b) employee nationality of being an American, Englishman, Arab, or Pakistani matters if IWE and IND are employed at globalized workplace in MNCs operating in United States, United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan? The study discoursed prior research in the field, leading to theoretical framework, and the linkages between IWE and IND are reviewed and hypothesized. Employee nationality (NAT) and religiosity (REL) are theorized as potential moderating variables that can influence the relationship between IWE and IND at workplace. The study discussed practical implications of IWE and IND for MNCs, and proffered recommendations for future prospects.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES

Work ethics

The term ‘work ethic’ is generally assumed to have its origin from the work of Karl ‘Max’ Weber in 1904–1930, when his essay (The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism) was published (Weber & Swedberg, Reference Weber and Swedberg1999). It did not only consider earning and accumulation of wealth as an individual affair, but also linked it to religious teachings (Weber, Reference Weber1958). In the corporate sector, work ethics takes some form of professional or business conduct when it judges values and morality of issues that arise in the business context. Ethical behavior at MNCs has grown huge importance (Novicevic et al., Reference Novicevic, Buckley, Harvey, Halbesleben and Rosiers2003; Tian, Liu, & Fan, Reference Tian, Liu and Fan2015), and global village has become an international market where no enterprise can survive in isolation. More than 70,000 MNCs generate 25% of world production (Küng, Reference Küng2009). As the business grows globally, the strategies demand deeper ethical ideology (Al-Khatib, Al-Habib, Bogari, & Salamah, Reference Al-Khatib, Al-Habib, Bogari and Salamah2014). Drawing on the resource-based view, Manroop, Singh, and Ezzedeen (Reference Manroop, Singh and Ezzedeen2014) emphasized the resource worthiness of ethical climate at workplace in attaining the competitive advantage.

Present global business demands a great deal of unified work ethics (Azmi, Reference Azmi2005; Küng, Reference Küng2009). Many studies (e.g., Chan, Fung, & Yau, Reference Chan, Fung and Yau2013; Lennerfors, Reference Lennerfors2013) highlighted the dearth of research in this field. They argued that existing business ethics are biased, nihilist, reactive, and vague. Research in business ethics stems from limited disciplines and focuses a micro context. It ought to form an inclusive subject based on empirical cases. Ali and Gibbs (Reference Ali and Gibbs1998) indicated that there exists a parallel understanding of work in ‘monotheistic religions’ that is Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. Consequently, several cross-cultural studies were carried out in this domain, and it was found that the basic concept of work ethic exists in all cultures, but it has been associated with different values and attributes (Furnham & Muhiudeen, Reference Furnham and Muhiudeen1984; Niles, Reference Niles1999; Arsalan, Reference Arslan2000).

IWE

Work ethic in Islam is based on the teachings of the Holy ‘Quran’ and ‘Sunnah’ (Following the everyday routine of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH)). Sunnah defines the teachings of the Holy Quran through practical examples and sayings (Hadith) by the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH). For better understanding of the Holy Quran and Sunnah by common people, the ‘Fuqaha’ (Islamic scholars) provide further assistance. Their guidance is taken as ethics until it does not contradict ‘Sharia’ (Islamic law established on the teachings of the Holy Quran and the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad, Hadith, and Sunnah). Wealth in Islam is detained in trust as God’s gift so long as the trust’s terms of reference are abided (Jamaluddin, Reference Jamaluddin2003). Regarding the employer and employee corporate relationship, the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) said that employer must inform employee/worker of his salaries while hiring him (An-Nasa’I 3888), and fairly compensate him on the completion of job before his sweat dries (Ibn Majah 2443). IWE not only focus on the obligatory importance of work, but also set job commitment and hard work as the basis for success (Ali, Reference Ali1988). Idleness, laziness and unproductive activities at work are forbidden, and wasting time is against the teachings of the Holy Quran (Yousef, Reference Yousef2000). Inspired by Islamic ethical thought, Ali (Reference Ali1988) developed a measure for scaling IWE through 46 items. They displayed work as an obligation and virtue to meet human needs in order to establish equilibrium in one’s social and personal life. Ali (Reference Ali1988) argued that work offers independence and provides basis for self-respect and satisfaction. Cooperation and doing creative work are true sources of happiness. Commitment, hard work, and communal welfare breed progress and success. There will be lesser problems if people are dedicated and committed to work without indulging in illegal accumulation of wealth (Ali, Reference Ali1988, Reference Ali1992).

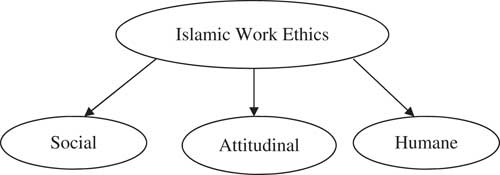

This study approached the IWE scale presented by Ali (Reference Ali1988) through ontological presumption of ‘realism’ that in the real world, entities, and relationships at work exist independently of our concept about them (Phillips, Reference Philips1987). In order to summarize the multidimensional relationships of variables into identical components of construct that could define Islamic ethical thought more parsimoniously (Harman, Reference Harman1976; Child, Reference Child1990; Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham2006), the study segregated 46 items of IWE into clear dimensions (Ali & Al-Owaihan, Reference Ali and Al-Owaihan2008; Ahmed & Owoyemi, Reference Ahmed and Owoyemi2012; Chudzicka-Czupała, Cozma, Grabowski, & Woehr, Reference Chudzicka-Czupała, Cozma, Grabowski and Woehr2012). Factorial analysis generated three dominant facets that described social, attitudinal and humane aspects of IWE as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Workplace facets of Islamic work ethics (IWE)

Social facet

IWE asserts that work should be meaningful and useful to community (Ali, Reference Ali1988). Involvement in financial activity is not only divine in itself, but also beneficial for a thriving community. Islamic business organizations are traditionally known for their socially responsible outlays (Ullah, Jamali, & Harwood, Reference Ullah, Jamali and Harwood2014). Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) advocated such business that is ethical and enhance social order (Ahmad, Reference Ahmad2011). Besides firm’s obligations toward employees, IWE also accentuates contribution to the community (Abu-Saad, Reference Abu-Saad2003). The Holy Quran considers work as source of social fulfillment, and teaches people to work determinedly when and where it is available. IWE establishes equilibrium in social and personal life. It promotes spiritual and economic growth so as to sustain one’s social status and assist societal welfare (Nasr, Reference Nasr1984). Ali and Al-Owaihan (Reference Ali and Al-Owaihan2008) highlighted the multidimensional view of IWE in their studies, and confirmed that IWE promote social strength and financial progress.

Attitudinal facet

Attitude at workplace is one of the prime determinants of organizational commitment, and has been the source of scholar’s concern in minimizing the employee turnover (Allen & Meyer, Reference Allen and Meyer1990). Employee attitude at work place is determined by his/her mental job evaluation and work orientation (Spector, Reference Spector1997). Koh and Boo (Reference Koh and Boo2004) linked employee attitude to work ethics espousing the theory of ‘organizational justice’ that is employee perception of justice affects his attitude at work. It is argued that unethical climate leads to deviant behavior (e.g., theft, fraud, and absenteeism, etc.), and costs colossal financial loss to the organization exchequer (Bhatti, Alkahtani, Hassan, & Sulaiman, Reference Bhatti, Alkahtani, Hassan and Sulaiman2015). IWE emphases that work is a source of self-respect, and employee should strive to meet the deadlines with better results (Ali, Reference Ali1988). At the same time human compassion is not overlooked. In case of unintended outcome, one’s attitude or intent, rather than result is the assessment criterion for work in Islam. Any activity that can be harmful to others is considered unlawful despite high economic outcomes (Ahmad, Reference Ahmad2011).

Humane facet

Ethics advocate humane moral values and honorable performance at work (Ali & Al-Owaihan, Reference Ali and Al-Owaihan2008). A business practice that is humane is also an ethical one. Hashim (Reference Hashim2012) theorized the humane facet of IWE, and argued that the dominance of western business culture has wiped out the humane aspect from corporate sector in a run for more profit. Azmi (Reference Azmi2005) defined work ethics as work morality, and asserted that humane behavior is the governing feature of employee conduct at workplace. He argued that secular business ethics need to have shared benefit for buyer and seller. IWE are humane, and they are based on long-term compassion. Employees have to watch their conduct, activities and expression at work (Yousef, Reference Yousef2000; Azmi, Reference Azmi2005).

Individualism

The scholarship of cross-cultural work ethics is not doable without considering collectivism-individualism perspective. Not only because it is the most extensively used cross-cultural facet in business and management studies (Triandis & Bhawuk, Reference Triandis and Bhawuk1997; Ramamoorthy, Kulkarni, Gupta, & Flood, Reference Ramamoorthy, Kulkarni, Gupta and Flood2007; Härtel, Härtel, & Trumble, Reference Härtel, Härtel and Trumble2013), and a strong Hofstede’s (Reference Hofstede1984) cultural dimension, but also because it is very intimately connected to innovation and international business (Černe, Jaklič, & Škerlavaj, Reference Černe, Jaklič and Škerlavaj2013). Stefanidis and Banai (Reference Stefanidis and Banai2014) found significant relationship between individualism-collectivism and ethical idealism at workplace. It specifically deals with how an individual link to a groups in the diverse cultures. Metaphysic that negates individual identity is ‘collectivism.’ It symbolizes the suppression of minority opinion, supremacy of group ethic over the individual and lack of self-determination (Jerry, 2006). Triandis and Bhawuk (Reference Triandis and Bhawuk1997) indicated that in the collectivist culture variation form group is not happily accepted, and cohesion and harmony is encouraged. Parity in preferred in managing the in-group affairs, but equity and justice is emphasized while managing the out-group. Whereas, in the individualistic culture variations are accepted and encouraged, equity and justice is given preference over parity.

Islam accentuates the importance of individualism as well as collectivism. The advent of mankind in Islam is individualistic with its origin from a single individual ‘Adam’ and believes that all mankind are one family, which is created by One God ‘Allah.’ Everyone has equal individuality regardless of color, race, class, and territory. Distinction based on these variables is a sheer illusion, and any ideological paradigm based on such distinction is the greatest menace (Ahmad, Reference Ahmad1976). Islam values every one’s individuality, holds every one accountable for his actions and promotes basic individual rights (Azmi, Reference Azmi2005). Everyone is free to earn livelihood and engage in lawful business. On the other hand, it promotes collective well-being of society, and makes Zakat obligatory for all Muslims (Sulaiman, Reference Sulaiman2003). Many studies (e.g., Ali, Reference Ali1988, Reference Ali1992; Ali et al., Reference Ali, Falcone and Azim1995) assessed the relationship between IWE and IND, and found a strong correlation between them. Hence, it was hypothesized that:

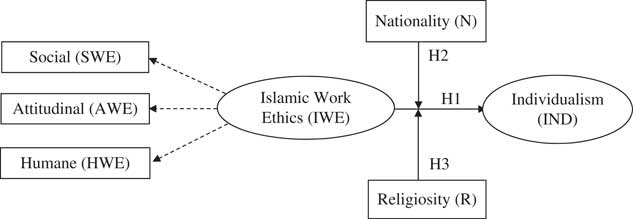

Hypothesis 1: Islamic Work Ethics is directly related to Individualism.

Nationality

Numerous surveys aimed at studying the impact of nationality on business in the MNCs have been conducted (Nachum, Reference Nachum2003; Nam, Parboteeah, Cullen, & Johnson, Reference Nam, Parboteeah, Cullen and Johnson2014; Bader & Schuster, Reference Bader and Schuster2015; Engelen, Schmidt, & Buchsteiner, Reference Engelen, Schmidt and Buchsteiner2015). Various other cross-cultural studies (e.g., Yousef, Reference Yousef2000; Abu-Saad, Reference Abu-Saad2003; Ali & Al-Kazemi, Reference Ali and Al-Kazemi2007) examined the influence of NAT and country’s political/economical state on work ethics. Significant effects of country-of-origin on MNCs management psyche and labor relations have been reported (Zhu, Zhu, & De Cieri, Reference Zhu, Zhu and De Cieri2014). Beekun, Stedham, Westerman, and Yamamura (Reference Beekun, Stedham, Westerman and Yamamura2010) investigated the relationship between ethical intention and gender in view of their national setting, and found that female respondents were more ethically driven than male. They contended that national background of female respondents significantly influenced their ethical intention. Similarly, a cross cultural study of Furnham et al. (Reference Furnham, Bond, Heaven, Hilton, Lobel, Masters and Van Daalen1993) based on protestant-work-ethics (PWE) in 13 countries found a significant variation in the respondent’s scores on PWE among different countries. Subjects from the developing countries that is West Indies, India, and Zimbabwe with low gross national product (GNP) scored significantly higher on PWE scale as compared to subjects from the developed countries with high GNP like United States, Germany, United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia. When the employee NAT and its subliminal influence on work ethics, as reviewed above, are considered, it is apparent that employees in the investigated MNCs will grade IWE and IND in accordance with there country’s economic and national ethos. Thus, it was hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2: Employee’s nationality modifies the relationship between Islamic work ethics and individualism at globalized workplace.

Religiosity

Religion is a ‘system of beliefs and practices’ (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2001). Brown (Reference Brown1987) and Gorsuch (Reference Gorsuch1988) described REL as a cultural and social feature that can be one of the causes of individual differences in behavior and personality. Religion creates new possibilities and further challenges. On one side, while it takes advantage of modern technology, at the same time it poses greatest resistance to globalization (Golebiewski, Reference Golebiewski2014). Many researchers (e.g., Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Van Buren2014) asserted that globalization brings diverse social and business cultures together, and suggested to adopt a logical approach for understanding the relationship between business, culture, and religion.

Why REL at workplace should be a business concern? The most usual answer can be that it may be a source of workplace controversy. Religious faith and its public expression can produce strong sentiments, and workplace is never an exception. REL at workplace has been a point of concern in numerous studies that reviewed the linkage between faith and work (Graafland, Mazereeuw, & Yahia, Reference Graafland, Mazereeuw and Yahia2006; Lynn, Naughton, & VanderVeen, Reference Lynn, Naughton and VanderVeen2009; Steele & Bullock, Reference Steele and Bullock2009; Pio & Syed, Reference Pio and Syed2014). Many others (e.g., Furnham & Muhiudeen, Reference Furnham and Muhiudeen1984; Ali & Gibbs, Reference Ali and Gibbs1998; Niles, Reference Niles1999) suggested relying on commonality of values in all religions. US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (2011) indicated that employee REL at American workplace has been one of the most demanding and controversial issues. Workplace conflicts at religiously diverse workplace occur 41% more frequently since 1997 that estimated about 174% increase in the payouts (US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2011). It was therefore, proposed that from the religious perspective, employees who perceive IWE and IND more ethical, would rank them higher. Thus, it was postulated that:

Hypothesis 3: Employee’s religiosity modifies the relationship between Islamic work ethics and individualism at globalized workplace.

The hypothesized relationships in the present study are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Study model

METHODOLOGY

Research design

This cross cultural study is a hypothesis testing, which explores a non-contrived relationship between IWE and IND at globalized workplace of MNCs operating in United States, United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan. In so doing, it analyzed the moderating role of employee NAT and REL. Three models were run to test the study hypotheses at α=0.05 significance level by espousing the moderated multivariate regression analysis. Variables were first mean-centered to minimize multicollinearity. Tolerance values were well above 0.1 (Least value observed was .479) and the variable-inflation-factor lesser than 10.0 (Highest value observed was 2.087) indicated no multicollinearity. Moderation significance was tested through coefficient’s t-test of the interaction terms as well as model’s F-test with the interaction terms added (Aiken & West, Reference Aiken and West1991; Bedeian & Mossholder, Reference Bedeian and Mossholder1994). Model fit of the latent structure was tested through structural modeling by employing renowned indices.

Sample

Prior cross-cultural study on PWE in 13 countries (Furnham et al., Reference Furnham, Bond, Heaven, Hilton, Lobel, Masters and Van Daalen1993) indicated significant variation in respondent’s scores based on their country’s economy (Geren, Reference Geren2011). The study, therefore, anticipated that scores on IWE might vary across employee NAT. Moreover, employee REL that is Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism at globalized workplace necessitated a stratified sampling technique that would better represent the population (Lucas, Reference Lucas2014). Hence, four stratums were selected that is United States, Saudi Arabia, United Kingdom, and Pakistan. Initially a list of 124 MNCs was prepared, which was later reduced to a total of 44 MNCs based on their employee NAT and REL profile. Two leading MNCs from each stratum were finally chosen, which mainly comprised oil, banking and tobacco industry. The suggested sample size was 480 MNC employees that is 120 each from all four stratums. However, a total of 310 participants sent back completely attempted questionnaires indicating 63.9% response rate comprising 72.3% male and 27.7% female respondents. Data screening through case-wise deletion further reduced the sample to 307. The remaining disproportionate-stratified sample of 307 subjects was found adequate for running factor analysis and parametric tests for hypotheses testing (Tabachnick & Fidell, Reference Tabachnick and Fidell1996; Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham2006; Sekaran, Reference Sekaran2006). Adequacy and representativeness of sample can be assessed through participant’s profile (Table 1).

Table 1 Functional and hierarchal background of participants

Note. C%=cumulative percentage.

Data

Primary data was collected in a non-contrived cross sectional method through online questionnaires. A pilot test with thirty subjects was run to evaluate the feasibility before data collection from the main sample. Data normality was assessed through its skewness and kurtosis values. Although, kurtosis value for two items was slightly higher (>1.0), but due to sample size margin, the normality was assumed through central limit theorem (Lumley, Diehr, Emerson, & Chen, Reference Lumley, Diehr, Emerson and Chen2002). Since a common data collection method was employed for all variables, Harman’s one-factor-test was conducted to examine the common method variance (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). The lone extracted factor accounted for only 14.4% explained variance, and it voided the possibility of common method bias.

Scaling measures

Empirical tools (IWE-46 items, and IND-7 items) developed by Ali (Reference Ali1988) were employed in the form of a questionnaire. Items were scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from ‘I strongly disagree’ to ‘I strongly agree’ (1: Strongly disagree, 2: Disagree, 3: Neutral, 4: Agree, and 5: Strongly agree).

Dependent variable: Individualism (α=0.89)

Measured through seven items for example ‘Individual incentives and rewards should be given priority over group incentives and rewards,’ and ‘One should be proud of his own achievements and accomplishments.’

Independent variable: IWE

Employing Kaiser’s criterion and varimax rotations, the principle-components factor analysis revealed 45 items with primary loadings greater than 0.5, measuring three component factors. Only one item (work is not an end in itself, but a means to foster personal growth and social relations), did not load sufficiently and was dropped. The extracted factors explained 43.87% of the variance cumulatively, with Factor 1 (SWE) contributing 21.80%, Factor 2 (HWE) contributing 12.26% and Factor 3 (AWE) contributing to 8.81%, respectively. SWE (α=0.75) was measured through 12 items for example, ‘One should take community affairs into consideration in his work.’ AWE (α=0.74) was measured through 21 items for example, ‘One should strive to achieve better results,’ and HWE (α=0.80) was measured through 12 items for example, ‘Exploitation in work is not praise worthy.’

Moderating variables

Employee NAT and REL were multilevel categorical and qualitative in nature. They were included in the regression equation as moderators by indicators that is dummy variables (Aguinis, Gottfredson, & Wright, Reference Aguinis, Gottfredson and Wright2011; Kenny, Reference Kenny2015).

Control variable

Females are more compassionate and considerate, and are likely to comprehend national culture better than male participants (Toussaint & Webb, Reference Toussaint and Webb2005). Several researchers (e.g., Beekun et al., Reference Beekun, Stedham, Westerman and Yamamura2010; Holtbrügge, Baron, & Friedmann, Reference Holtbrügge, Baron and Friedmann2014) found a significant linkage between respondent’s gender and ethical behavior. Similarly, many others (e.g., Eweje & Brunton, Reference Eweje and Brunton2010; Morrell & Jayawardhena, Reference Morrell and Jayawardhena2010) found that female respondents, irrespective of their age and experience, were found more ethically driven as compared to male respondents. This study also assumed that among other demographic variables, respondent’s gender might confound various relationships under study. Thus, employee gender was incorporated as the control variable.

Construct validity

Convergent and discriminant validity was analyzed through Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Factor loading of items along with their statistical significance to a particular construct was evaluated. The standardized factor loadings were mostly above 0.4, and 43 out of 52 items had p≤.001, as shown in Table 2. It indicated a satisfactory convergent validity (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham2006). Discriminant validity was assessed to assure that a particular construct is unique in capturing a specific phenomenon as compared to other construct. The results (χ2=2570.85; p<.001; df=1268; χ2/df=2.02; RMSEA=0.05) established that desired model sufficiently fit the data, and it also confirmed discriminant validity of the constructs (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham2006).

Table 2 Standardized factor loadings and statistical significance

Note. **p≤.001.

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics and reliability of study variables are provided in Table 3. The overall mean values of SWE were comparatively higher than other variable. While NAT and REL scores had higher independent residuals, they exhibited a relatively kurtotic and skewed distribution, and there mean values were comparatively lower with higher standard deviation. Table 3 elucidated a significantly positive correlation between IWE and IND (r=0.710; p<.01), a weak negative correlation of NAT with IWE (r=−0.287; p<.01), and a significantly weaker, but positive correlation between REL and IWE (r=0.172, p<.01).

Table 3 Descriptive statistics: mean, standard deviations, and correlations of variables (N=307)

Note. Reliability is given in parenthesis.

*p≤.05; **p≤.01.

Control variable (gender)

Before testing study hypotheses, the influence of respondent’s gender was examined discretely so that it can be controlled in the subsequent analysis. But, predictor Gender (control variable) and criterion IND were insignificantly related (F(1, 305)=0.239, p=.625, R 2=0.001). Employee gender negligibly accounted for 0.1% of explained variance in IND, and was not found to be a potential confounder in the study (Pole & Bondy, Reference Pole and Bondy2010). Thus, the idea of controlling the effects of employee gender was dropped.

Hypotheses testing

Model 1 was run to establish the relationship between IWE and IND. Regression analysis revealed a significant model among predictor IWE and criterion IND accounting for 34.9% explained variance in IND (F(4, 302)=40.435, p<.001, R 2=0.349). The individual contribution of three facets of IWE that is SWE (R 2=0.216, p<.001), AWE (ΔR 2=0.036, p=.001), and HWE (ΔR 2=0.096, p<.001) are provided in Table 4. These results presented sufficient evidence to support Hypothesis 1 stating that IWE is directly related to IND at globalized workplace.

Table 4 Multiple regression analysis (N=307), dependent variable: individualism

Note. AWE=attitudinal work ethics; HWE=humane work ethics; NAT=nationality; REL=religiosity; SWE=social work ethics.*p≤.05. **p≤.01. (two-tailed).

Model 2 was run to examine the moderating role of employee NAT in the relationship between IWE and IND. The inclusion of moderator NAT in the regression analysis did not demonstrate significant interaction effect (F(5, 301)=41.120, p<.001 to F(6, 300)=1.723, ΔR 2=0.004, p=.190). Model 2 accounting for 35.4% explained variance was supplemented insignificantly to 35.8% explained variance in IND. These results (Table 4) did not provide sufficient evidence to support Hypothesis 2. Thus, it was concluded that employee NAT does not modify the relationship between IWE and IND at globalized workplace. Likewise, model 3 was run to test the moderating role of employee REL. Its addition in the regression analysis emerged a more insignificant model depicting no interaction effect (F(5, 301)=40.404, p<.001 to F(6, 300)=0.516, ΔR 2=0.001, p=.473). The model accounting for 35% explained variance was insignificantly enhanced to 35.1% explained variance in IND. Based on these results (Table 4) there existed no sufficient evidence to support Hypothesis 3, indicating that employ REL does not modify the direct relationship between IWE and IND at globalized workplace.

Model fit

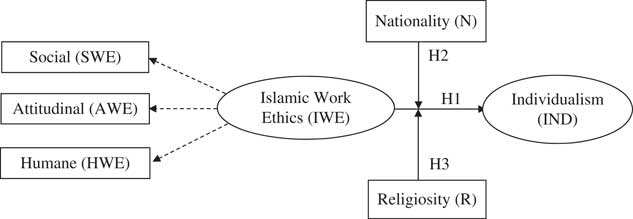

The latent structure of the theorized model was evaluated through structural-path analysis with renowned model fit indices. The criteria were: χ2/df≤3.0, goodness-of-fit index that is GFI≥0.90, adjusted goodness-of-fit index that is AGFI≥0.8, and root-mean-square-error of approximation that is RMSEA≤0.08 (Jackson, Denzee, Douglas, & Shimeall, Reference Jackson, Denzee, Douglas and Shimeall2005; Teo & Khine, Reference Teo and Khine2009). The path model presented in Figure 3 converged without iterations and all indices were found in acceptable range. The absolute-fit-index (χ2/df) at 0.05 thresholds with fitted covariance matrix was 2.71, and RMSEA was 0.075. It indicated that present model with chosen parameter estimation attained an adequate fit with the covariance matrix of its population. Likewise, examining the variance accounted for through anticipated population covariance (Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996), the comparative fit indices that is GFI=0.939 and AGFI=0.899 were attained. Together these results indicated that the desired model sufficiently fit the data.

Figure 3 Latent structure of the study model. AWE=attitudinal work ethics; HWE=humane work ethics; IND=Individualism; IWE=Islamic work ethics; SWE=social work ethics

DISCUSSION

First, the study found negligible influence of employee gender in the relationship between IWE and IND. Though female respondents scored slightly higher on both variables, but the mean difference was insignificant. These results did not support the findings of prior researchers (e.g., Eweje & Brunton, Reference Eweje and Brunton2010; Morrell & Jayawardhena, Reference Morrell and Jayawardhena2010; Holtbrügge, Baron, & Friedmann, Reference Holtbrügge, Baron and Friedmann2014) who found significant linkage between respondent’s gender and ethical behavior, and proposed that female were more ethically driven than male. Moreover, present scores were consistent across investigated MNCs in all four countries. It could not endure the findings of Beekun et al. (Reference Beekun, Stedham, Westerman and Yamamura2010) that national cultural dimensions significantly affect female’s higher ethical orientation.

Second, the study found a direct relationship between IWE and IND at globalized workplace in the selected countries (F(4, 302)=40.435, p<.001, R 2=0.349). It indorsed the findings of Stefanidis and Banai (Reference Stefanidis and Banai2014) that individualism-collectivism and ethical idealism are related in the workplace context. Also, all three extracted facets of IWE were directly related to IND. These findings supported the stance of previous researchers (Ali, Reference Ali1992; Ali, Falcone, Azim, Reference Ali, Falcone and Azim1995; Yousef, Reference Yousef2000). The Social facet (SWE) accounted for 21.6% of explained variance in IND. It was in congruence with the assertion of prior researchers (Abu-Saad, Reference Abu-Saad2003; Ali & Al-Owaihan, Reference Ali and Al-Owaihan2008; Ullah, Jamali, & Harwood, Reference Ullah, Jamali and Harwood2014) that IWE emphasize obligations towards employees along with contribution to society. The attitudinal facet (AWE) significantly supplemented the explained variance in IND by 3.6%, which endorsed the findings of Sager, Yi, and Futrell (Reference Sager, Yi and Futrell1998) and Ahmad (Reference Ahmad2011) regarding work ethics and its linkage with employee attitude. It also furthered the assumption of Koh and Boo (Reference Koh and Boo2004) in explaining employee attitude and perception of justice at workplace. Human facet (HWE) also enhanced 9.6% of explained variance in IND, indicating the importance of humane and moral value of IWE (Azmi, Reference Azmi2005). A considerably higher score on IWE across all investigated MNCs indicated moral awareness and importance of ethical conduct in MNCs (Novicevic et al., Reference Novicevic, Buckley, Harvey, Halbesleben and Rosiers2003). It also supported the resource worthiness of ethical climate at workplace in attaining the competitive advantage (Manroop, Singh, & Ezzedeen Reference Manroop, Singh and Ezzedeen2014).

Third, the study found no evidence to prove the influence of NAT in the relationship between IWE and IND at globalized workplace. Furnham et al. (Reference Furnham, Bond, Heaven, Hilton, Lobel, Masters and Van Daalen1993) found that respondents from developing countries with low GNP scored significantly higher on PWE scale as compared to subjects from developed countries with high GNP. Geren (Reference Geren2011) argued that PWE were better predictors of country’s economy and financial success rather than partiality for ethics. Present study did not support the findings of Furnham et al. (Reference Furnham, Bond, Heaven, Hilton, Lobel, Masters and Van Daalen1993) and Nachum (Reference Nachum2003), and found that MNC employees in United States, United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan with dissimilar GNP scored evenly on IWE.

Last, the study observed that respondents professing different religions scored consistently on IWE and IND. These results did not withstand the opinion of many prior researchers (e.g., Graafland, Mazereeuw, & Yahia, Reference Graafland, Mazereeuw and Yahia2006; Lynn, Naughton, & VanderVeen, Reference Lynn, Naughton and VanderVeen2009; Steele & Bullock, Reference Steele and Bullock2009; US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2011) that religiosity and employee faith at workplace is a point of great concern. Results, however, strongly sustained the notion of shared value of work ethic across different religions (Furnham & Muhiudeen, Reference Furnham and Muhiudeen1984; Ali & Gibbs, Reference Ali and Gibbs1998; Niles, Reference Niles1999; Azmi, Reference Azmi2005). Present results were plotted following Aiken and West (Reference Aiken and West1991) method to show the interaction effects of NAT and REL as presented in Figure 4. Regression line indicated that IWE was positively related to IND. Inclusion of participant’s NAT and REL (moderators) did not produce any significant change in the slope and/or intercept of regression line.

Figure 4 Interaction effect depicted through change in the regression line

Implications

Globalization has confronted more than 70,000 MNCs with new challenges, which need an ethical response (Küng, Reference Küng2009). Corporate scams in recent years (e.g., Enron, Adelphia, etc.) revealed that those drowned organizations had inclusive business practices, well-known external auditors, efficient reporting system and a range of independent directors at all tiers. They only lacked business ethics (Johnson, Reference Johnson2003). Küng (Reference Küng2009) argued that political will and laws are not sufficient to combat greed and corruption until there is an ethical will. The value of understanding the shared agreement on IWE and IND at globalized workplace is obvious in that it will facilitate MNCs in generating an ethical consciousness at workplace based on some basic moral standards. There is a wider benefit to the HR managers at MNCs in resolving one of the most demanding issues of employee’s REL indicated by the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (2011), and saving dollars spent on managing workplace diversity. It may also reduce workplace deviance costing up to $200 billion to the US economy every year (Bhatti et al., Reference Bhatti, Alkahtani, Hassan and Sulaiman2015). In the similar vein, workplace quandaries and misunderstandings owing to cultural and religious differences indicated by prior researchers (e.g., Graafland, Mazereeuw, & Yahia, Reference Graafland, Mazereeuw and Yahia2006; Lynn, Naughton, & VanderVeen, Reference Lynn, Naughton and VanderVeen2009; Steele & Bullock, Reference Steele and Bullock2009) can be curtailed if interventions are designed around the present results. Along the lines of Manroop, Singh, and Ezzedeen (Reference Manroop, Singh and Ezzedeen2014), present results illuminated the strategic probity of ethical climate at workplace. It not only encourages entrepreneurial orientation and mirrors employee’s confidence in the firm, but also establishes emotional bonding and adaptation (Engelen, Schmidt, & Buchsteiner, Reference Engelen, Schmidt and Buchsteiner2015). It is ever more important for MNCs to deal with work ethics as their business strategy. This will helps in creating more ethical principal-agent affiliation (Vallejo-Martos & Puentes-Poyatos, Reference Vallejo-Martos and Puentes-Poyatos2014).

Limitations and future directions

With the present results in hand, research in work ethics should take into account certain important viewpoints in future. First, respondent’s belief in work ethics says little about ethical practice. As Graafland, Mazereeuw, & Yahia (Reference Graafland, Mazereeuw and Yahia2006) found that Muslim entrepreneurs attached higher weight to certain elements of socially responsible business conduct than do non-Muslims. But, in practice, they found the opposite results. If informant method for data collection is employed in the future studies (Hassan & Sinha, 2014), the present results can be ascribed to workplace with greater confidence. Second, this study focused on employee gender and the moderating role of employee NAT and REL. whereas, alongside gender, age also has a greater impact on employee ethical attitude (Holtbrügge, Baron, & Friedmann, Reference Holtbrügge, Baron and Friedmann2014). Also, more educated participants because of their widespread intellectual framework are more likely to be thoughtful as compared to less educated participants. Therefore, it is recommended that employee age and education level must be kept in mind in future studies for more realistic predictions. Third, this study did not focus on how organizational social support in the host country persuade employee ethical and individualistic perceptions (Chen, Kirkman, Kim, Farh, & Tangirala, Reference Chen, Kirkman, Kim, Farh and Tangirala2010), thus future research in this field must focus on this factor for additional insight. And lastly, academics have explored a vertical and a horizontal connotation of individualism, and have linked these facets to ethics in many different ways (Chen & Li, Reference Chen and Li2005). For example, vertical-individualism views self as autonomous and radically different from other people whereas horizontal-individualism views oneself as one among independent others. Therefore, another avenue for future research would be examining the relationship of IWE and horizontal and vertical IND.

Conclusion

Formulating a cohesive ethical response to the challenges raised by globalization is particularly difficult for MNCs because, although their workplace is increasingly global, yet it is not much uniform. It generates cultural biases and individual differences, which is exacerbated by the economic crisis and moral deficiencies in the policies of institutions. This places ‘ethics’ at the forefront of 21st century’s business demands, and it must constitute the core of corporate culture. MNCs have to deal with culturally diverse, but increasingly well-informed and demanding employees. Shared moral principles at the workplace are needed in order to take full advantage of the enormous opportunities offered by globalization. This study underlined the ethical dimension of work at globalized workplace. It found IWE positively related to IND at the globalized workplace and empirically established that gender, nationality, and religiosity of employee do not matter if IWE are employed at the MNC’s workplace.

Acknowledgments

This is an original work, and it has not been submitted to nor published elsewhere. Approval of all authors has been obtained. Manuscript deals with the probity of work ethics in management of globalized workplace at MNCs operating in four countries, and is with in the scope and aim of the journal.