INTRODUCTION

The history of archaeological exploration in Crete has received extensive attention in the last few decades (Rizzo Reference Rizzo, Di Vita, La Rosa and Rizzo1984; Belli and Vagnetti Reference Belli and Vagnetti1990; La Rosa Reference La Rosa, Belli and Vagnetti1990; Reference La Rosa2000a; Reference La Rosa2000b; Reference La Rosa2000–1; Brown Reference Brown1993; Sakellarakis Reference Sakellarakis1998; Brown and Bennett Reference Brown and Bennett2001; Momigliano Reference Momigliano2002; Hamilakis and Momigliano Reference Hamilakis and Momigliano2006; Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2008; Reference Kotsonas, Loukos, Xifaras and Pateraki2009; Reference Kotsonas2016; Reference Kotsonas and Gavrilaki2018b; D'Agata Reference D'Agata and Kopaka2009; Varouhakis Reference Varouhakis, Petmezas and Tzedaki-Apostolaki2014; Reference Varouhakis2015; Whitley Reference Whitley, Haggis and Antonaccio2015; Genova Reference Genova2019; Reference Genovaforthcoming). The present study builds on this tradition in investigating the politics and the research agendas embedded in past research on Lyktos (Fig. 1), in reviewing and evaluating the small-scale fieldwork conducted at the site, and in charting the abortive plans for more systematic excavations. Extending from the Renaissance to the early twenty-first century, my analysis covers the complex history of archaeological research at Lyktos, and the ways in which this relates to political and disciplinary history.

Fig. 1. Map of Crete with sites mentioned in the text; created by Vyron Antoniadis.

Lyktos (also spelled Lyttos since the Classical period: Perlman Reference Perlman, Hansen and Nielsen2004, 1175) is located on the north-west foothills of the Lasithi mountains, at an elevation of over 600 m, near the village of Xydas (also spelled Xidas). The name Lyktos may refer to the highland location of the site (Kaszyńska Reference Kaszyńska2001). The ancient city is amply referenced in ancient literature. Homer (Iliad 2.647, 17.610–11) and Hesiod (Theogony 477–82) mention Lyktos, which makes it the only Cretan city (and one of the few Greek cities) mentioned by both early Greek poets.Footnote 1 Homer further sung of the death of the Lyktian warrior Koiranos at the hands of Hector at Troy (Iliad 17.610–11) (on Homer's Crete see Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2018a), while Hellenistic and Roman literature praised the Lyktian archers and their bows (Vertoudakis Reference Vertoudakis2000, 29–33, 69–72).

Lyktos was widely considered a Spartan colony in Classical and later literature (Aristotle, Politics 2.7.1/1271b 28–31; Ephorus apud Strabo 10.4.17; Polybius 4.54.6; Plutarch, Moralia 247). Historians acknowledge some reliability in this tradition, but they also consider the possibility it was invented in the Classical period, in the mid-fifth or the mid-fourth century bc (Perlman Reference Perlman and Hansen2005, 318–19 and Malkin Reference Malkin1994, 77–80, respectively). In any case, the Spartan connection dominates the textual references to the political history of Lyktos.Footnote 2 The legendary lawgiver Lycurgus allegedly visited Lyktos and was influenced by her laws in introducing the Spartan regime (Aristotle, Politics 2.7.1/1271b 20–8; and partly Ephorus apud Strabo 10.4.17; see Perlman Reference Perlman1992, 200; Reference Perlman and Hansen2005, 302–5, 310–11, 318–19), while the two cities reportedly helped each other in war: Lyktian troops allegedly fought with the Spartans during the Second Messenian War in 668 bc (Pausanias 4.19.4), and Spartan forces helped the Lyktians recapture their city from the Knossians in 343/342 bc (Diodorus 16.62.4). However, following her defeat in Sellasia in 222 bc, Sparta could not save Lyktos from the destruction the Knossians inflicted on her with a surprise attack in 221/220 bc (Polybius 4.53–4). The Cretan city was resettled soon afterwards, as confirmed by an inscription from Chersonessos (SEG LI 722; cf. Kritzas Reference Kritzas and Andreadaki-Vlasaki2011). Lyktos fell to the Romans in 69 bc (Livy, Periochae 99) and seems to have flourished in the Antonine period (see below).

Further snippets on the socio-political and religious history of Lyktos can be gleaned from both Classical literature and epigraphy.Footnote 3 Indeed, the site has produced the second largest epigraphic record from anywhere on Crete (after Gortyn),Footnote 4 even though it has attracted minimal fieldwork and limited attention in archaeological research. As lamented by George Harrison, ‘Lyttos remains, however, the last great city in Crete whose location is known and has not been systematically excavated’ (Harrison Reference Harrison1993, 201; cf. Erickson Reference Erickson2010, 3; Cross Reference Cross2011, 223). This state of research has been dramatised in the characterisation of Lyktos as a ‘phantom city’ (van Effenterre and Gondicas Reference Effenterre, Gondicas, Bellancourt-Valdher and Corvisier1999; Reference Effenterre, Gondicas and Karetsou2000).

The dearth of archaeological exploration at Lyktos seems particularly surprising when one considers that the site attracted the notable attention of pioneers of Cretan archaeology. This issue is discussed in the second and third sections below, which draw from published and unpublished archival material held by several institutions. This material shows that early archaeological interest in Lyktos involved a courteous way of settling competing claims and aspirations, especially between Italian and British archaeologists. This trajectory is unusual and contrasts with the international rivalries over other important Cretan sites, including the so-called ‘battle of Knossos’ (La Rosa Reference La Rosa2000a, 23–37; Reference La Rosa2000–1, 64–80; Momigliano Reference Momigliano2002, 268, with references), the ‘siege of Gortyn’ (La Rosa Reference La Rosa2000a, 31–2; Reference La Rosa2000–1, 75–6; cf. Sakellarakis Reference Sakellarakis1998, 136–47), and the competition for Goulas (Lato) (La Rosa Reference La Rosa2000a, 28–9; Reference La Rosa2000–1, 72; Momigliano Reference Momigliano2002, 268, 279, 285 n. 90, with references). A competing ‘triple claim’ is attested for Lyktos only for a few months in 1912–13, on the eve of the island's union with Greece.

The fourth section of this study shows that the poor state of the research on Lyktos partly depends on the limited documentation and appreciation of the different campaigns of small-scale fieldwork conducted at the site in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Drawing from research in the archives of the Italian Archaeological School at Athens, I document three different campaigns of small-scale Italian excavations at Lyktos, which have hitherto remained largely unknown. This allows the tracing of several inscriptions and sculptures, which have previously been considered as chance finds from Lyktos, back to their original context of discovery.

The fifth section reviews the range of largely small-scale fieldwork campaigns which were conducted by the Greek Archaeological Service (occasionally with support from the Archaeological Society at Athens) in the post-War period. The limited topographical information provided in relevant reports has long hindered the full appreciation of their results. To compensate for this, I provide a new map which enables the contextualisation of past discoveries. The map is essential also for the sixth section, which integrates past discoveries with secondary literature on the ancient city to generate a comprehensive and diachronic panorama of the archaeology of Lyktos from the prehistoric to the Medieval period.

FROM THE RENAISSANCE TO THE LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY

The toponym Lyktos survived the abandonment of the ancient city, which has attracted the attention of antiquarians and foreign travelers since the fifteenth century. Relevant references have received considerable attention (van Effenterre and Gondicas Reference Effenterre, Gondicas, Bellancourt-Valdher and Corvisier1999, 128–31; Reference Effenterre, Gondicas and Karetsou2000, 440–2; Papadaki (Reference Papadakino date)), but the following discussion offers new information and interpretations.

Several antiquarians of the Renaissance note that antiquities from Lyktos were taken to the estates of local nobility. In 1417, the Florentine humanist Cristoforo Buondelmonti visited the villa of the Venetian nobleman Nicolò Corner and found his garden decorated with statues, some of which may have derived from neighbouring Lyktos.Footnote 5 In 1567, Fransesco Barozzi reported that marbles from Lyktos, including an inscription for Trajan, were located in the garden of the nobleman Marco Corner Borgognon at the village of Diavaide, now nearly adjacent to Kastelli Pediadas (Kaklamanis Reference Kaklamanis2004, 226–7, 309–11; cf. ICr I, p. 182). Lastly, towards the end of the sixteenth century, the doctor and naturalist Onorio Belli saw an inscribed sarcophagus from Lyktos in the same village, at the garden of Marco Fratello (Falkener Reference Falkener1854, 18).

Belli was the first to provide detailed reports on the archaeological landscape of Lyktos.Footnote 6 He recorded circular towers (later identified as Early Byzantine), three temples and other structures on the acropolis, as well as the impressive Roman aqueduct, parts of which remain well preserved (on the aqueduct see Oikonomakis Reference Oikonomakis1984; Kelly Reference Kelly, Aristodemou and Tassios2018). Also, he identified a basilica and documented the theatre, which is considered as the largest on Crete (with a cavea diameter of 55 m internally and 167 m externally according to Belli's plan).Footnote 7 It was rock-cut and was arranged in four tiers with a colonnade at the top, within the final wall, and possibly a double colonnade beyond this wall, while the scenae frons was 76 m long and had three doors, the central one set in a curved exedra. The location of the theatre of Lyktos remains unknown, but scholars have developed different hypotheses on this, as discussed below.

Belli discovered six statues in the ‘basilica’, and he recorded numerous inscriptions from the site, including inscribed grave stelae, and statue bases referring primarily to Trajan and his family.Footnote 8 From the six (now lost?) statues he mentions, Belli described only a male torso in enough detail to allow for its identification with Hadrian.Footnote 9 The statue of Hadrian and two other female statues from Lyktos were exported to Venice and were at the mansion of the Governor-General of Crete Alvise Grimani in the late sixteenth century, but their current whereabouts are unknown (Beschi Reference Beschi1972–3, 493; Reference Beschi1974, 222; Reference Beschi and Santi1996, 177). Being regarded as less beautiful, the other three statues were not removed from the site.

For nearly two centuries after the Ottoman conquest of Crete (ad 1645–69), the antiquities of Lyktos apparently attracted minimal attention. However, interest revived in the early to mid-nineteenth century when three different visitors recorded numerous inscriptions at the site, including some mentioned by Belli. In June 1834, Robert Pashley (Reference Pashley1837, 270 n. 48) spent two days at Lyktos, where he ‘copied a great number of inscriptions’, but he did not publish any information on the site and its monuments. A longer account was published by Miltiadis Chourmouzis Vyzantios (Reference Chourmouzis Vyzantios1842), a Greek of possibly Cretan background who was born in Constantinople and fought in Crete during the Greek War of Independence in 1828–30. Chourmouzis Vyzantios recorded several inscriptions from Lyktos and described an archaeological discovery at the site.Footnote 10 Two marble statues and a marble relief sarcophagus were discovered in 1817 and were taken to the house of an Ottoman notable at Xydas. The man painted the monuments and placed them by a fountain. However, he later fell sick and he blamed this on the monuments, which he considered haunted; accordingly, he ordered the villagers to take them back to their findspot. Soon after, a European doctor who visited the Ottoman notable broke off and removed the head and the hands of the statues. Chourmouzis Vyzantios commented sarcastically: ‘what a contrast between the superstitious Ottoman and the illustrious European doctor’ (Chourmouzis Vyzantios Reference Chourmouzis Vyzantios1842, 57 n. 1). This story suggests the continuation of the Venetian practice of using Lyktian monuments as garden decorations, albeit with the addition of colour. Other parts of the story, however, are more familiar from elsewhere in Ottoman Greece: westerners look for opportunities to seize antiquities while locals fear that such practice may bring evil (cf. Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis, Bahrani, Çelik and Eldem2011). However, the final comment by Chourmouzis Vyzantios is remarkable in blending a spirit of resistance to foreign appropriation with western-type criticism of local superstition.

The two statues mentioned by Chourmouzis Vyzantios are probably to be identified with the two statues seen by the British Captain Thomas Spratt at Lyktos in 1850. Spratt described that ‘on the summit of the ruins lie also two marble statues near the small chapel … [They] are headless – one being a recently discovered statue of a draped female, the other the lower half of a colossal statue of Jupiter’ (Spratt Reference Spratt1865, 97). Spratt also made note of ‘several sculptured marbles’ (Spratt Reference Spratt1865, 97), including an altar showing a youth holding a torch and a hare on the two main sides and ram's heads and festoons on the other two sides (Spratt Reference Spratt1865, 98), and he recorded numerous inscriptions, including inscribed statue bases for Roman emperors (Spratt Reference Spratt1865, 97–8; Babington Reference Babington and Spratt1865, 415–19). With reference to architecture, Spratt observed ‘several marble and even granite columns’ but ‘no vestiges of buildings in situ’ and he questioned Belli's reliability on the theatre (Spratt Reference Spratt1865, 97).

In the late nineteenth century Crete entered a turbulent period. At the time, Ottoman, Greek and western perspectives on the politics and the antiquities of the island came into conflict, and the rise of Greek nationalism and European colonialism eroded and eventually overthrew Ottoman suzerainty (Hamilakis and Momigliano Reference Hamilakis and Momigliano2006; Varouhakis Reference Varouhakis2015; Genova Reference Genova2019). The pact of Chalepa of 1878 granted privileges to the Christian Cretans and favoured the development of their interest in antiquities (Sakellarakis Reference Sakellarakis1998, 131–65; Varouhakis Reference Varouhakis2015, 32–3, 132; Genova Reference Genova2019, 12–23). Symptomatic of these developments was the foundation of the Cretan Association of Friends of Education (Κρητικός Φιλεκπαιδευτικός Σύλλογος) at Herakleio and its archaeological focus. Interestingly, the Association acquired an Archaic relief pithos from Lyktos in 1886.Footnote 11 Such pithoi were later found at Lyktos in abundance and are arguably the most iconic class of material from the site. Two decades earlier, in 1866, a Late Hellenistic female statue of a divinity(?) from Lyktos was donated to the British Museum by the Cretan antiquarian Minos Kalokairinos and his brother Andreas.Footnote 12

Foreign interest in Cretan archaeology also rose after the Pact of Chalepa. European scholars visited the island in increasing numbers to study the topography and document accessible monuments. By highlighting the island's Greek past and its significance for European culture, this research promoted the nationalistic agenda of the Christian Cretans against Ottoman rule and for union with Greece (Momigliano Reference Momigliano2002, 269; La Rosa Reference La Rosa2000a, 10; Reference La Rosa2000–1, 52). Nevertheless, Christian Cretans resisted any plans for excavation for fear that the finds would be taken to the Imperial Museum in Constantinople (Sakellarakis Reference Sakellarakis1998, 43–4; Carabott Reference Carabott, Hamilakis and Momigliano2006, 39–40; Varouhakis Reference Varouhakis2015, 92–3; Genova Reference Genova2019, 65–7). Under these circumstances, archaeological research in late nineteenth-century Crete focused on the documentation of inscriptions. Although the epigraphic focus is more broadly characteristic of archaeological practice in nineteenth-century Greece, its manifestation in Crete assumed special significance. By documenting hundreds of ancient inscriptions typically written in Greek, foreign scholars demonstrated the deep-roots of the Greek-speaking inhabitants of the island and thus undermined Ottoman suzerainty over it (La Rosa Reference La Rosa2000a, 42–3; Reference La Rosa2000–1, 86–7; Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2008, 278).

It was epigraphy which attracted the first professional scholars to Lyktos. Apparently, the first such visitor was Bernard Haussoullier, a member of the French School at Athens who visited the site in 1879, precisely 140 years ago (Haussoullier Reference Haussoullier1885, 14–16, 21–7). Haussoullier was followed by Georges Doublet in 1888,Footnote 13 but French interest in Lyktos was discontinued, and reemerged only a century later with epigraphic and historical studies by Henri van Effenterre and associates (van Effenterre and van Effenterre 1985; van Effenterre and Gondicas Reference Effenterre, Gondicas, Bellancourt-Valdher and Corvisier1999; Reference Effenterre, Gondicas and Karetsou2000).

From the mid-1880s to the Interwar period the antiquities of Lyktos attracted more systematic attention by Italian and British scholars. While the former followed the French in their epigraphic focus and were primarily interested in Roman imperial monuments, like the antiquarians of previous centuries, British interest seems to have focused on the pre-Classical phases of Lyktos. A similar distinction has been identified by James Whitley (Reference Whitley, Haggis and Antonaccio2015, 28–35) in the concurrent Italian and British interest in the East Cretan site of Praisos. Whitley has explained that the Italians were operating in the German tradition of Altertumswissenschaft and were specifically interested in epigraphy and Classical archaeology, while the British developed interests of broader chronological and thematic scope.

Federico Halbherr, Italian epigraphist and pioneer of Cretan archaeology, visited Lyktos repeatedly in 1884–7 and 1893–4.Footnote 14 Halbherr identified many previously known and also unknown inscriptions, which were usually found out of context and were often built into houses at the village of Xydas or in nearby chapels.Footnote 15 Interestingly, in 1893 Halbherr was accompanied by the American John Alden, a graduate from Yale University, who helped document Lyktian inscriptions (ICr I xviii 85, 86, 88, 90, 107, 124, 156, 164, 174, 177, 180).

In the summer of 1894, Halbherr, together with his student Antonio Taramelli, conducted a small excavation ‘near’ the chapel of Timios Stavros, also known as Estavromenos.Footnote 16 They located a row of Roman inscribed statue bases for Trajan and his family and they proposed to identify there the agora.Footnote 17 This excavation has been overlooked by scholarship,Footnote 18 but it is adequately documented in archival material discussed in the next section.

Descriptions of the remains of Lyktos were published by two of Halbherr's Italian colleagues: his co-excavator Taramelli, who visited the site in 1894 and a few years later, and Luigi Mariani, who visited Lyktos in 1893.Footnote 19 Mariani only briefly mentioned structures of Roman and later date and imperial statue bases. Taramelli offered a longer account, which distinguished between the acropolis and a lower city extending on the south and west slopes of the hill, emphasised the vast size of Roman Lyktos, and commented on the negative effects of cultivation on the ancient remains. Taramelli assumed that the acropolis was the site of different temples, of the theatre documented by Belli, and also of the Roman agora, to which he attributed the imperial statues and statue bases for Trajan and his family. On the acropolis he identified the remains of a Roman villa or barracks near the hilltop, as well as a Byzantine fort involving two towers and a long wall.Footnote 20 He also illustrated an inscribed Roman statue and hypothesised that local artworks may have reached western museums (Taramelli Reference Taramelli1899, 390–5). Both scholars (but especially Taramelli) further referred to the Roman aqueduct and showed an interest in the territorial extent of Lyktos and in surrounding prehistoric to Byzantine sites (Mariani Reference Mariani1895, 238–9, 242, 246; Taramelli Reference Taramelli1899, 390, 398–407).

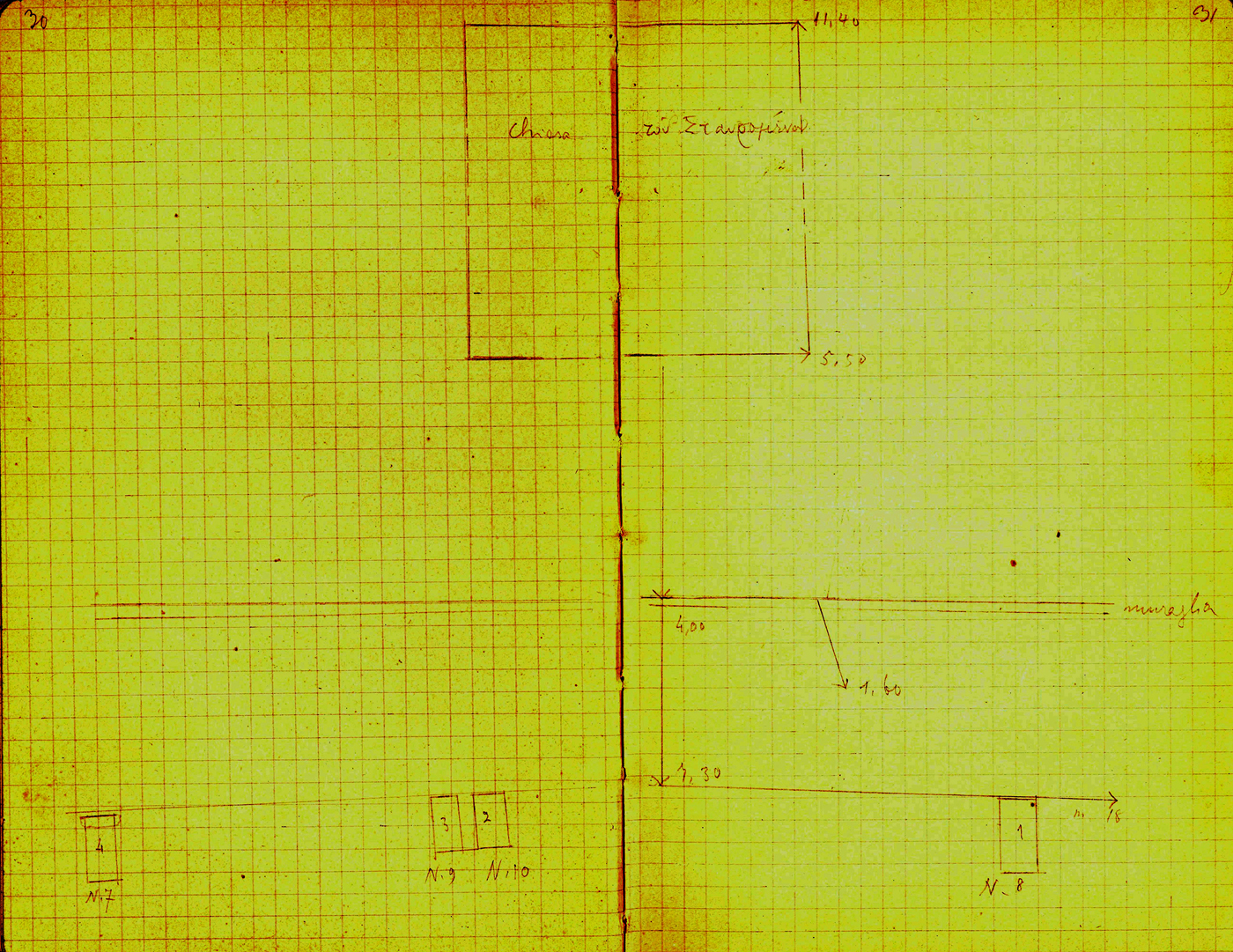

Mariani produced a sketch map of Lyktos (Fig. 2) which marks the location of the chapels of Agios Georgios and Timios Stavros with numbers 1 and 3 respectively, with the term ‘chiesa’ (church) added for the latter monument. Windmills (mulino/mulini) surround the chapel of Agios Georgios on the plan. Number 4 marks an unidentifiable location, while the corners of three structures extend south-east of Agios Georgios and south of Timios Stavros. Lastly, in the natural cavity west of the latter chapel Mariani places the ‘probabile sito del teatro’ seen by Belli. Stergios Spanakis argued against this idea, noting that no architecture is visible at this location and observing that this spot is fully exposed to the northern wind (Spanakis Reference Spanakis1968, 159 n. 52; cf. Sanders Reference Sanders1982, 61). Instead, Spanakis proposed that the theatre is to be sought in the corresponding natural cavity on the southern part of the hill, south-east of the chapel of Timios Stavros. He also observed that Roman masonry is preserved at a certain spot the locals call ‘phylakes’ which, however, belongs to the castellum of the aqueduct (Sanders Reference Sanders1982, 146; Oikonomakis Reference Oikonomakis1984, 77 pls 9 and 14; Kelly Reference Kelly, Aristodemou and Tassios2018, 165; also see below). Spanakis's argument remains to be investigated with excavation or geophysical prospection.Footnote 21

Fig. 2. Sketch map of Lyktos by Mariani, from Taramelli Reference Taramelli1899, 389–90 fig. 39.

Mariani and Taramelli raised the possibility of pre-Classical occupation at Lyktos, but they also noted the paucity of relevant finds (Mariani Reference Mariani1895, 238–9; Taramelli Reference Taramelli1899, 388, 397–8). Taramelli, however, observed that the location Sta Visala, north-east of the acropolis, yielded pottery of Greek and Roman date (including a relief pithos fragment), in addition to urns and cremated bones. A few years later Taramelli expressed strong interest in exploring this site hoping to find burials dating to the transition from the Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age, which would shed light on the coming of the Dorians to Crete and the introduction of the rite of cremation.Footnote 22

Taramelli's plan for excavating Lyktos did not materialise, probably because of the concurrent emergence of British interest in the site. This interest was first manifested in 1895 but persisted (with notable fluctuation) for three and a half decades and was dominated by the figure of Arthur Evans.Footnote 23 Despite what some scholars think (van Effenterre and Gondicas Reference Effenterre, Gondicas, Bellancourt-Valdher and Corvisier1999, 129; Reference Effenterre, Gondicas and Karetsou2000, 440), Evans did not overlook Lyktos. On the contrary, he had a zealous interest in the site, which was admittedly eclipsed by his work at Knossos. Evans first visited Lyktos in mid-April 1895, together with John Linton Myres. The two scholars were intrigued by the connection of the ancient city with the Psychro Cave, which they thought the Lyktians identified with the cave in which Zeus was born according to Hesiod (Theogony 477–82).Footnote 24 The cave had yielded a range of finds since the 1880s, and produced more with the British excavations of 1895 to 1900, which Evans and Myres inaugurated (Watrous Reference Watrous1996; cf. Brown and Bennett Reference Brown and Bennett2001, 356–7). It is unclear if the two British scholars, who later became renowned for their fieldwork in Minoan Crete, were familiar with the ancient traditions which considered Lyktos as the most ancient city on the island (Polybius 4.54.6) or knew of any prehistoric finds from the site. However, they considered Lyktos as the starting point of a ‘Mycenaean road’ heading east (Evans and Myres Reference Evans and Myres1895, 469; cf. Taramelli Reference Taramelli1899, 398–9). Also, Evans acquired (possibly in 1895) a Neopalatial lead female figure allegedly deriving from Lyktos, and (on an unspecified occasion) a carnelian bead-seal showing a horned sheep, which came from Lyktos or its vicinity.Footnote 25 In a later publication, Evans deduced a prehistoric past for Lyktos on the basis of: (a) the ancient tradition which presented the eponymous Lyktios as the father-in-law of Minos Ι and as great-grandfather of the famous Minos II (Diodorus 4.60), and (b) the attestation of an early, pre-Homeric name for the site, Karnessopolis (Evans Reference Evans1921, 10–11, 625; also, Mariani Reference Mariani1895, 238 n. 4; Taramelli Reference Taramelli1899, 397).

While the Italian and British interest in Lyktos was on the rise, the interest of local scholars remained limited. However, in 1897 Stephanos Xanthoudidis, then newly appointed Secretary of the Κρητικός Φιλεκπαιδευτικός Σύλλογος, published four inscriptions found at the village of Xydas but provenanced from the location Sta Vissala, ‘northwest’(?) of the acropolis of Lyktos.Footnote 26 Later Xanthoudidis published a Minoan and a Byzantine seal from Lyktos held by the Archaeological Museum of Herakleio.Footnote 27

Foreign interest in the antiquities of Lyktos intensified with the establishment of the modern Cretan state. Before the end of 1898 the Ottoman army withdrew from Crete; the island was recognised as an autonomous state under Ottoman suzerainty under the protection of the Great Powers with Prince George of Greece as High Commissioner.Footnote 28 This development marked the beginning of a new phase in the archaeological exploration of the island, which is characterised by European colonialism (Carabott Reference Carabott, Hamilakis and Momigliano2006; Varouhakis Reference Varouhakis2015; Genova Reference Genova2019) and in which ‘all the foreign schools rushed into the promised land of the archaeologists’ (Chatzidakis Reference Chatzidakis1931, 41; cf. Hogarth and Bosanquet Reference Hogarth and Bosanquet1899, 321).

As deduced from later correspondence, in mid-March 1899 Evans met David Hogarth, then Director of the British School at Athens, in the Greek capital, to discuss the British interest in different Cretan sites, and the ways to secure their claims (on Hogarth see Brown and Bennett Reference Brown and Bennett2001, 387–8). The two men approached Prince George independently through his unofficial advisor James David Bourchier. On 20 March, Bourchier ‘wrote to Prince re Hogarth's claim to Knossos and Lyttos’.Footnote 29 Two days later, upon his arrival on autonomous Crete, Evans met Bourchier and asked him to pass a letter to Prince George, which explained the British claims on Cretan archaeological sites, placing Lyktos second after Knossos: ‘I may mention as the principal site that we have in view besides Knôsos, the ancient Lyttos with the neighbouring Cave of Psychro, the Dictaean Cave of Zeus, distant about 4 hours mule journey from Lyttos’; the list continued with ‘minor points’, including Zakros and Kalamafka, Kamares and the Cave of Hermes Kranaios at Patsos.Footnote 30

The response of Prince George came quickly, on 23 March. As Evans commented, ‘Prince George himself was very favourable. Promised all we want.’Footnote 31 This development was reported in the Annual of the School, where Lyktos was presented as ‘the model Dorian city’ (Anonymous 1898–9, 102). The report also announced the foundation of a ‘Cretan Exploration Fund’ to promote research on the different sites secured, and warned that ‘both France and Italy are already claiming their share, and others may be expected to follow suit. The [School's Managing] Committee feels the importance of immediate action’ (Anonymous 1898–9, 102).

French, Italians and also Americans launched fieldwork project across Crete around 1900. This explains the British urge for Lyktos, which is illuminated by archival documents. Following the Prince's response, Evans notified Halbherr about the British claim over the site.Footnote 32 Halbherr had also requested a permit to excavate Lyktos, but he had to leave it to the British.Footnote 33 The British seemed eager to start excavations, and on 29 March 1899 Hogarth wrote to Evans ‘I expect there is little doubt we must begin eventually with Lyttos.’Footnote 34 From 20 to 22 April, the two scholars visited the site.Footnote 35 Evans copied four Roman inscriptions, including one for Hadrian previously seen by Spratt, and he acquired an Archaic pithos fragment.Footnote 36 Most importantly, Evans and Hogarth drew sketch maps of Lyktos with rich information (Figs 3, 4).Footnote 37

Fig. 3. Sketch map of Lyktos by Evans (AN.Evans.Letters.Lyttos-29-03-1899 ‘Sketch map of the Lyttos site’. Image © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford).

Fig. 4. Sketch map of Lyktos by Hogarth from his unpublished travel diary for 1899 (by permission of Professor Caroline Barron).

Evans's map (Fig. 3) is titled ‘Lyttos’ at the bottom, and has the four cardinal points indicated by capital letters. Mount ‘Ida’ lies by the ‘W’, while the prominent location on the lower central part of the map is labeled ‘AKROP’ (acropolis) and is surrounded by walls including a semicircular tower. To the west extends a line of rough squares labelled ‘W.M’ twice, which must refer to the early modern windmills on the west end of the acropolis. Just north of these mills the plan reads ‘further off’. The chapel of Agios Georgios occupies a central position on the map and is referenced as ‘H. Georgios’. North-west of there are ‘fragments of Geometrical pithoi’ and further off is a ‘spring’ (Spyridiano spring). The pithos fragments are flanked by two Xs and more Xs occur around Timios Stavros. Although the meaning of these markings is unclear, Hogarth used Xs to indicate inscriptions lying on some of the same locations. ‘Fragments of larnakes’ are indicated immediately north of the chapel of Agios Georgios, and further north-west is a ‘hole’ and a ‘W.M’ (windmill), in addition to a long wall with four semicircular formations which lies north of the path that crosses the acropolis. More walls are located north and north-west of the chapel of Timios Stavros (‘H. Stavros’), and further north to north-west lies a long stretch of ‘early wall’. To the east of the chapel there is a wall marked ‘? Hellenic’ and the label ‘knoll’, while to the south the map reads ‘80p’ and ‘100p’ (p probably stands for paces and 100 paces, or 76 m, must designate the distance between the two chapels), as well as ‘cistern’. A series of features extend in a north–south direction along the southern slopes of the acropolis: ‘base with cryptogram’, ‘near here found’ a rectangular feature, ‘monastiri’ and ‘spring’. The upper right corner of the map, which is east of the chapel of Timios Stavros, includes the labels ‘large block said to be found’(?), ‘cippus with snake’, ‘phyleke’ and ‘fragment of pithos with spirals’. Lastly, the central part of the top end of the map reads ‘late tombs’ and, below it, ‘further off’.

Hogarth's map of Lyktos (Fig. 4) is more detailed than that of Evans and is accompanied by a commentary in his notebook.Footnote 38 The map is titled ‘LYTTOS’ and comes with a key explaining the symbols for inscriptions and early walls. The map shows the acropolis with the row of windmills and the two chapels, the names of which Hogarth has confused, hence the question-marks on the labels ‘H. Stavros?’ and ‘H. Georgios?’. In between the two churches the map identifies a ‘Hadrian altar’ and a ‘tower’ that must be Byzantine. The notebook mentions ‘city walls’ and ‘Medieval and Byz. fortifications’ without topographic information, but places the ‘mills outside enceinte’. The map illustrates a building with ‘apses’ on the upper north slope of the acropolis, west of the chapel of Timios Stavros which is erroneously marked ‘H. Georgios?’. The chapel is framed by a larger rectangular structure, while the notebook remarks: ‘a temple almost certainly under’. The map shows several inscriptions west of the chapel and the notebook places a ‘gate north of it’.Footnote 39 The location of an ‘excavation’ and a ‘high rock’ (Evans's ‘knoll’) are immediately east of the church on the map, while a narrow ridge east of the acropolis, immediately east of the chapel of Timios Stavros, is labelled as ‘Mycenaean necropolis’ (the notebook adds ‘late Myc.’). On the east end of this ridge, the map has a ‘brick structure’. Further east there is an extensive area labelled ‘late necropolis’ with ‘tombs’ (‘ridge full of tombs’ in the notebook), which is dotted by findspots of inscriptions and a ‘snake relief’. The area south-east of the acropolis is labelled ‘terraces’ and further south is the ‘monasteri’ also noted by Evans. The western part of the south slope is marked ‘fields’. On the upper central part of the south slope Hogarth's map places a concentration of ‘much pottery’, and his notebook adds: ‘Pottery very scarce on acropolis. Most on S. centre but all thick red though may be early pithoi. (Bit of one with relief from “pottery heap” v. map). Bits of lustreless black but no painted or distinctively Cretan anywhere.’ Further south the map places the ‘remains of city’ and marks the locations of stretches of walls, including a curved one marked ‘theatre?’ (the notebook places the theatre ‘low down on SW’). On the map, the north slope shows fewer but varied features. The west half of the north slope is covered by ‘terraces’ and ‘early tombs?’. Further east are ‘vineyards’ with stretches of ancient walls, and the north-east slope is marked ‘non terraced fields & vineyards (deep earth) little pottery’. It is probably in this area, at a distance to the north of the chapel of Timios Stavros, that Hogarth placed the agora: ‘Deep depression (half filled detritus from hill on E.), at NE. = Agora?’, adding in his notes ‘at NE. = Agora? But neighbouring tombs’ (to the east), and also mentioning the ‘Agora Hollow’. Hogarth's notes conclude: ‘No caps [capitals?] or mouldings or “Hellenic” remains about at all!’

The descriptions and maps of Evans and Hogarth indicate a well-watered landscape with agricultural (particularly vinicultural) and milling activities. Besides the chapels and the mills on the acropolis, the terraces on its slopes, and a monastery lying south, this landscape is largely unaffected by buildings of recent centuries. Individual features described and illustrated on the two maps can be associated with earlier and later discoveries at Lyktos, and relevant observations by other scholars. The fortifications and the towers around the acropolis belong to the Early Byzantine wall circuit which was first noted by Taramelli and was studied recently (see below). The long wall with semicircular formations, which both maps illustrate north-west of Timios Stavros, can be identified with the monumental building with niches of the Imperial period excavated there in the 1980s (Rethemiotakis Reference Rethemiotakis1983; Reference Rethemiotakis1984, 58–61). The ‘phyleke’ (sic) Evans notes is the location ‘phylake’ or ‘phylakes’ on the south slope of the acropolis, where masonry of the Imperial period is still preserved and probably represents the castellum of the aqueduct (Sanders Reference Sanders1982, 146; Oikonomakis Reference Oikonomakis1984, 77 pls 9 and 14; Kelly Reference Kelly, Aristodemou and Tassios2018, 165). Hogarth proposed to identify the agora at a distance to the north of Timios Stavros, and he tentatively suggested that the theatre was located south to south-west of the acropolis, on a location which is different to those proposed by Taramelli and Spanakis.

The fragments of pithoi noted on Evans's map and mentioned in Hogarth's notebook belong to one of the most prolific classes of finds from Lyktos. On the contrary, the fragments of larnakes that Evans's map locates north of the chapel of Agios Georgios are puzzling. A few sarcophagus burials dating between the Archaic and Hellenistic periods are known from the site (Lebessi Reference Lebessi1973–4, 886–7; cf. Alexiou Reference Alexiou1973, 475; Mandalaki Reference Mandalaki1997), but it would be very surprising to find such burials on top of a Classical acropolis. The alternative possibility that the larnakes are Late Minoan cannot be excluded, but a hilltop would be an unusual findspot for such finds. Late Minoan burials are, however, identified by Hogarth east of the chapel of Timios Stavros. Both maps locate an extensive burial area further east and north-east of the acropolis, and make special reference to a ‘cippus with snake’ (Evans) or ‘snake relief’ (Hogarth), which was visible on the same spot until very recently and recalls Roman inscribed monuments with relief snakes that are known from other locations at Lyktos (see below).

Despite securing the permit for Lyktos from Prince George, and collecting the above wealth of information, the British neither published on the site nor proceeded with any excavation. This may be partly explained by a note in Hogarth's diary of 1900: ‘Did not think any better of Lyttos; covered up + difficult to find place for earth.’Footnote 40 Besides, in the same year Hogarth excavated the Psychro Cave (Hogarth Reference Hogarth1899–1900; cf. Brown and Bennett Reference Brown and Bennett2001, 356), which was one of the prime reasons for his interest in Lyktos. He also excavated Minoan remains at Knossos, but because of his unimpressive discoveries and the difficult collaboration with Evans, he moved to Minoan Zakros in 1901 (Mowat, Leaf and Macmillan Reference Mowat, Leaf and Macmillan1899–1900, 130–1; Momigliano Reference Momigliano1999, 38–9). In the same year, the British School also turned its attention to East Crete, especially to Praisos (1901) and Palaikastro (1902), which are explored by British scholars to the present day (Bosanquet Reference Bosanquet1901–2, 286; Brown and Bennett Reference Brown and Bennett2001, 350, 355; Whitley Reference Whitley, Haggis and Antonaccio2015, 31–5). Nonetheless, prehistoric Palaikastro attracted several more excavation seasons than Classical Praisos, which is indicative of the priorities of the School's work in Crete in the early twentieth century and partly accounts for the abandonment of Lyktos. In any case, British and other interest in Lyktos revived a decade later.

THE ‘TRIPLE CLAIM’ FOR LYKTOS ON THE EVE OF CRETE'S UNION WITH GREECE (1912–13)

On the eve of Crete's Union with Greece, Italian, British and Greek scholars developed rival plans for excavating Lyktos. These plans put the amicable relationships of the previous period to the test.

In 1908, Halbherr revived the Italian interest in Lyktos by encouraging the epigraphist Gaetano de Sanctis to consider conducting small-scale fieldwork aimed at the recovery of inscriptions.Footnote 41 He added that it was advisable to contact Evans, even though he believed that the permit the British had obtained concerned only prehistoric finds. Indeed, Halbherr wrote to Evans about this late in 1909.Footnote 42 Before replying, Evans consulted Hogarth and Richard Dawkins, then Director of the British School at Athens (on Dawkins see Gill Reference Gill2011, 57–60; Mackridge Reference Mackridge, Giannakopoulou and Skordyles2017). As Evans noted to Dawkins, ‘I have no designs on Lyttos myself’ and Hogarth was ‘quite ready to let Halbherr [get] what he wants’.Footnote 43 However, Evans also remarked: ‘I feel that the British School may be inclined to cherish designs on Lyttos. As a great Dorian city of Crete & a kind of pendant to Sparta’, where the School was excavating since 1905, with Dawkins's participation (Gill Reference Gill2011, 170–6). The description of Lyktos as a ‘Dorian city’ was not unknown among the British (Anonymous 1898–9, 102), but Evans's interest in its Dorian identity and Spartan connection may have been also informed by Taramelli's plan for excavating the coming of the Dorians to Lyktos; by an article published in the School's Annual of 1910 which sought to trace the ‘descendants’ of the Dorians in Crete and the Peloponnese (Hawes Reference Hawes1909–10); and by the comparable focus on the Eteocretans which characterises the British exploration of Praisos (Whitley Reference Whitley, Haggis and Antonaccio2015, 26, 31–5). In any case, Evans also noted to Dawkins: ‘In that case the School would not want to have the later strata looked over even if the Minoan layer – which is at present quite problematic – were left untouched.’ Evans concluded by noting that Halbherr ‘must not play the dog in the manger’ and discourage any British claims, but he confessed he was indebted to the Italian scholar for making Linear A inscriptions available to him, which is why he wanted any positive response to him to appear as a ‘concession’.

Dawkins's response to Evans remains unknown, but later correspondence suggests no specific plan for Lyktos was developed at the time. Nonetheless, Evans took several months to write to Halbherr, which he attributed to illness, but he also noted that some of his ‘colleagues had certain concerns on the matter, but I [Evans] have succeeded in entirely overcoming them’; Halbherr had ‘the fullest liberty to carry out any researches & excavations’ at Lyktos.Footnote 44 In the autumn of 1910 Halbherr started preparing a visit to the site,Footnote 45 but this did not result in any action.

Both the Italian and the British interest in Lyktos revived independently of each other between December 1912 and January 1913. This time Halbherr was marginally faster than the British. On 5 December 1912 the Italian scholar submitted a permit request to excavate the site to Iossif Chatzidakis, then Ephor of Antiquities for Central and East Crete.Footnote 46 Chatzidakis, who was friends with Halbherr and had promoted his research since the mid-1880s (La Rosa Reference La Rosa2000a; Reference La Rosa2000–1), thought favourably of the plan and communicated his view to Xanthoudidis, then Ephor at Chania. This triggered a volatile chain of events involving these three scholars, and also Stefanos Dragoumis, then Governor-General of Crete (who had served as Prime Minister of Greece briefly in 1910 and had a strong interest in archaeology), as well as the British School at Athens.Footnote 47 Immediately after his communication with Chatzidakis, on December 6, Xanthoudidis wrote to Dragoumis listing the reasons why Halbherr and the Italians should not be granted the permit for Lyktos:Footnote 48 (a) the Union with Greece was imminent and it was best to leave it to the Archaeological Society and other relevant institutions to assess this matter in the light of the Greek archaeological law, and ‘to the interest of science and the united country’; (b) the Italian delegation on Crete and the Italian Archaeological School at Athens had received permits to excavate six different Cretan cities: they had finished work at Phaistos and Agia Triada, they had only started at Prinias and Gortyn, and they had not even touched Eleutherna and Afrati; and (c) the same mission was insufficiently staffed to carry out these works, as shown by their failure to publish their finds from Axos and Lebena, and their workload had increased by the extension of their activities to Cyrenaica. On this basis, Xanthoudidis considered that Halbherr's request was not intended to serve an imminent plan, but to secure the site for future exploration. As he noted:

Lyttos is one of the few large archaeological sites on Crete, which is hoped to yield important monuments of Greek antiquity; thus, the issue requires much reluctance and consideration. It is not impossible that the Archaeological Society and Greek archaeologists will find the means to conduct fieldwork at the site, while so many other sites are excavated by foreign schools.

Xanthoudidis concluded his letter to Dragoumis by drawing his attention to the provision of the Cretan archaeological law, which specified that decisions on permit requests could be made by the Ephor in charge of the area, or by the Archaeological Commission of the Cretan State, which involved the two Ephors, as well as the curators of the Museums of Herakleio and Rethymno, Andreas Vourdoumpakis and Andreas Petroulakis respectively (on these two see Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2008, 282, 284 n. 43, 293; Genova Reference Genova2019, 349 nn. 53–4); according to Xanthoudidis, such a serious matter was best dealt with by the Commission.

Dragoumis followed the advice of Xanthoudidis and brought Halbherr's request to the attention of the Archaeological Commission on 18 December 1912. The Commission convened on 28 December and evaluated not only Halbherr's request, but also letters by Chatzidakis and Xanthoudidis advising on the matter. Chatzidakis's proposal for the approval of the request on the grounds that it complied with the Cretan law was outvoted by the others who espoused the ideas of Xanthoudidis: ‘Lyttos is one of the most significant archaeological centres of Crete, and we are currently at a transitional period as the political situation on Crete, and thus the management of archaeological matters, is about to change.’Footnote 49 Given the non-urgent character of the issue, they felt they should not rush into a decision that would be binding to the authorities that would soon take over. However, they took note of the fact that ‘the Italian mission was the first of the foreign missions to request a permit for Lyktos.’

The recommendation of Xanthoudidis and the decision of the Commission seem judicious, but certain aspects of it can be best appreciated in the light of archaeological politics under the Cretan State. Xanthoudidis had reasons to be acrimonious to Halbherr. In 1901, the Ephor discovered several Late Minoan III tombs at Kalyvia, near Phaistos, but in the colonial spirit that characterised the Cretan archaeology of the time the Italians demanded to take control of his excavation, because it was within their area of jurisdiction (Momigliano Reference Momigliano2002, 271–3; Varouhakis Reference Varouhakis2015, 102, 123, 141; Genova Reference Genova2019, 325, 338, 372–3). Notably, Xanthoudidis reported this old incident to Dragoumis shortly after the correspondence discussed above.Footnote 50 On the other hand, Xanthoudidis's criticism over the many claims of foreign schools and his idea for the involvement of the Archaeological Society largely echo a statement made in 1900 by Panagiotis (Panagis) Kavvadias, then General Ephor of Antiquities in Greece and Secretary of the Archaeological Society at Athens: ‘We think that our Archaeological Society should take part in Cretan excavations, by undertaking research in one of the numerous ancient Cretan cities, since, thank God, there is enough space for everyone …’.Footnote 51 Members of the Society were engaged with the antiquities of Crete since the 1880s, and Dragoumis was a prominent member of it.Footnote 52 However, the involvement of the Society in the exploration of Lyktos was apparently not pursued.Footnote 53

Less than a week after the Commission's decision to reject the Italian request for Lyktos – and independently of it – the British interest in the site revived with Dawkins. At the time, Dawkins had planned to excavate Datcha (or Datça) on the Knidos peninsula. However, the plan was interrupted by the Italo-Turkish War (September 1911 to October 1912), which involved the Italian seizure of the Dodecanese, and the First Balkan War (October 1912 to May 1913) (Gill Reference Gill2011, 60, 193–4, 199–200, 219–22). Several sites were considered instead, and Lyktos was one of those favoured.

On 3 January 1913, Dawkins wrote to John Baker Penoyre, the London Secretary of the British School at Athens, to propose excavating the site and ask for advice: ‘it would be well to undertake Lyttos in Crete.’Footnote 54 The proposal came with good reasoning: (a) the site ‘fell to the British share’ in 1899 and it was doubtful that ‘this allotment will last for ever’, especially after ‘the annexation [of the island] to Greece’; (b) Lyktos had promising finds of varied date: ῾The site itself is Roman at the top, and Archaic Greek things may be expected below, and below them I suppose Minoan᾽; and (c) the Italians ‘have their eye on the place, and it is one of the best[?] sites left in Crete’.

A dense exchange of correspondence on this plan developed from January to mid-March 1913, starting with Dawkins's request for advice from senior British scholars. Hogarth warned him of potential complications, which included the interest of Halbherr, and the understanding of Chatzidakis that the permit that Prince George had given to the British was no longer valid.Footnote 55 Evans began his own response enthusiastically: ‘the model Dorian state would be an excellent sequel to Sparta’, and he also added that the neighbouring Kastelli, which had yielded pithoi and other terracottas, could also be explored in connection with Lyktos.Footnote 56 Evans, like Hogarth, warned Dawkins that the prince's promise was no longer valid, but he was more optimistic with reference to any rival Italian claim. Evans also reminded Dawkins of the correspondence they had exchanged on Lyktos in 1910, also adding that the German scholar Wilhelm Dörpfeld ‘wanted’ to excavate the site ‘at one time’ but ‘that scheme fell through’.Footnote 57 This was perhaps in the early 1900s, when Dörpfeld visited different Cretan sites and expressed an interest in Palaikastro (Bosanquet Reference Bosanquet1901–2, 286).

The British scholars swiftly proceeded with the plan for Lyktos. On 12 February 1913, ‘The Managing Committee of the British School at Athens, being desirous of having excavations carried out on the site of Lyttos’ appointed Dawkins to ‘act as their agent’ and to ‘take any other steps necessary on their behalf for the successful issue of the work’.Footnote 58 The British scholars were very concerned about the Italian reaction to the plan, and Dawkins wrote: ‘It will be very mean of the Italians and very grabbing if they stand in our way.’Footnote 59 Evans was asked to approach Halbherr, who responded he had applied to the Cretan government for the site, but he was willing to ‘hand over the rest of Lyttos to the British School’, only reserving the area of the Roman agora for ‘small work’.Footnote 60 A few days later, Evans wrote to Dawkins: ‘I suggest that besides his circumscribed dig you make Halbherr epigraphist for whole.’Footnote 61

On 15 February 1913, Chatzidakis received letters from both Dawkins and Halbherr concerning Lyktos. In his letter, Dawkins reported the positive outcome of the correspondence of the British with Halbherr and asked for the support of the Ephor in preparing a formal application for fieldwork at the site.Footnote 62 Halbherr's letter concerned a revised request for conducting limited fieldwork:

Our mission seeks to excavate the city's Roman agora (the location of which I know) for the purposes of epigraphic studies. I started excavating there already in 1894 but I had to quit because of the difficulties posed by the Turkish Government at the time.Footnote 63

Chatzidakis replied to Dawkins and Halbherr on the same day (15 February). The letter to Dawkins explained that the Government of Crete was planning to appoint an Ephor and use public funds to excavate Lyktos.Footnote 64 Chatzidakis noted that the plan had not been finalised, but he also invited Dawkins to consider another site noting that ‘Fortunately, only rarely does the Cretan soil refuse to satisfy the antiquarians.’ The letter to Halbherr remains unknown, but apparently it communicated the plans of the Government of Crete.Footnote 65

On the same day (15 February) Chatzidakis forwarded the requests of Dawkins and Halbherr to Dragoumis asking for advice.Footnote 66 He also added, however, comments in support of the foreign scholars, thus addressing indirectly some of the criticisms Xanthoudidis had raised two months earlier. Chatzidakis noted that Halbherr's study of Cretan epigraphy went back to 1883, and he commented that the proposed trial trenches at Lyktos would contribute to the comprehensiveness of the work. He further praised Halbherr and Dawkins for taking each other into consideration and for respecting ‘the rule the archaeologists generally follow’ which mandates not digging a site for which a colleague has obtained rights. In the present case, Chatzidakis noted, Halbherr had felt obliged to consult Evans, who had obtained the permit for Lyktos via Prince George.

Dragoumis's response to Chatzidakis, on 18 February, was stiff. Indeed, it represents a strong reaction to European colonialism and thus marks the end of an era for the archaeology of Crete.Footnote 67 The Governor-General reminded the Ephor of the pending union of Crete and Greece, and acknowledged that while the correspondence between Halbherr and Dawkins was courteous it also begged the question: ‘how [these two scholars] have already started to pre-divide the archaeological terrain of the island without notifying the Cretan Government and without knowing its intentions and regulations’. In response to Chatzidakis's reference to the permit granted by Prince George, Dragoumis noted:

The decisions and the actions of the Cretan Government are confirmed only by the documents kept in the state archives. In state business there is no room for vague private communications. The Governor-General of the island, who is appointed by the king's command, conducted special research in the archaeological archive … and found nothing suggesting that Lyktos was given to Mr. Evans or the British School at Athens for wide-ranging excavation.

Notwithstanding these remarks, Dragoumis was sympathetic to Halbherr's revised proposal for small-scale Italian excavation in the agora focused on epigraphy, and he promised to approve this revised request provided it was addressed to the General Government.

Importantly, in the same letter, Dragoumis noted that the General Government of Crete would keep Lyktos for itself and that ‘it had decided to secure some initial funds for wide-ranging excavation of the site, and had budgeted for this in the budget of the fiscal year 1912.’ This plan, which represents the first Greek initiative for the excavation of Lyktos, was motivated by both academic and political considerations. Dragoumis must have chosen Lyktos because it was the most celebrated Cretan city which was still available for exploration, Knossos and Gortyn being taken by the British and the Italians respectively. Also, the British and Italian requests for Lyktos were indicative of the significance of the site and made its exploration timely. Lyktos may also have been chosen because of its alleged foundation by a mainland Greek city, which could be taken to celebrate the union of the island with Greece. The significance of the union perhaps also inspired Xanthoudidis's idea for the involvement of the Archaeological Society at Athens.

Beside securing a budget, Dragoumis's plan for Lyktos also involved other practical arrangements. The Governor-General was hoping that he ‘would go there himself from time to time’ but an Ephor would conduct the fieldwork; it is unclear who this Ephor would be, but Evans hypothesised Xanthoudidis.Footnote 68 This hypothesis seems reasonable since Xanthoudidis was the first to advocate that Lyktos should be reserved for Greek fieldwork. Also, he had previously published some archaeological material from the ancient city (see above) and came from the nearby village of Avdou. In any case, the plan for Lyktos did not materialize, probably because Dragoumis was posted to Macedonia in June 1913, at the time of the outbreak of the Second Balkan War.

Dawkins was disappointed with the Greek plan, and upon reaching London in mid-March 1913 he reported to the Managing Committee of the British School that Lyktos was unavailable: ‘The Greek Archaeological Society wants it to seal their union with Crete, and it seems that D[ragoumis] wants to dig it himself, so there is no chance at all. It is annoying.’Footnote 69 A slightly later letter reads: ‘It is very tiresome of D[ragoumis] and as I believe he has done no digging, he will make a very sad mess of Lyttos, but being a Greek, I suppose he feels he has nothing to learn.’Footnote 70 By mid-April 1913 Evans met Dragoumis but failed to convince him over the British claim on the site, or to discourage him by stressing that excavating Lyktos would be ‘difficult’.Footnote 71 More openly frustrated was Frederick William Hasluck, Assistant Director of the British School and personally connected to Dawkins (Gill Reference Gill2011, 56–7, 110–11, 217): ‘In plain English the Cretan govt [government] are going to dig Lyttos, in order to do the organgrinders in the eye.’Footnote 72 Not only did Hasluck consider that this plan was developed only to foil the British claim to the site, but he compared Dragoumis to low-class street musicians, and potentially characterised the Cretan Ephors in a more derogatory way by evoking the English proverbial expression which distinguishes between the authority of organgrinders over the monkeys they used to collect money from their audience.

In response to the Greek plan for Lyktos, Evans recommended that the British School turn its attention to Eleutherna, in central-west Crete, where an important Archaic statue had been found and a Hellenistic bridge was still standing.Footnote 73 This suggestion was not taken up at the time, but resurfaced in 1928–9. In the spring of 1913, Dawkins took a tour of central Crete and the Lasithi plateau in a search for sites to explore, and in the summer and the autumn he excavated the Kamares Cave and also at Plati in Lasithi (Gill Reference Gill2011, 200).

The Cretan government was more generous to Halbherr. As Chatzidakis wrote to him, the government granted him permission to conduct limited excavation at the Roman agora, but it did not give anyone a general permit to excavate Lyktos.Footnote 74 At the beginning of 1914, Halbherr wrote to Evans on the possibility of a small-scale dig in the agora of Lyktos aimed at the recovery of inscriptions.Footnote 75 The outcome of this plan has remained unknown but is discussed in the next section together with a better documented Italian campaign of 1924. The decade that separates the two campaigns presents a break in the international interest in Lyktos, and is explained by the tragedy of World War I (1914–18) and the failed Greek campaign in Asia Minor (1919–22).

THE TWILIGHT OF INTERNATIONAL INTEREST IN THE INTERWAR PERIOD AND THE ITALIAN EXCAVATION OF A ROMAN MONUMENTAL COMPLEX

Interest in the archaeology of Lyktos persisted in the Interwar period. However, it was largely monopolised by the Italians and the British, who often returned to agendas of the late nineteenth century.

Italian scholars conducted limited excavations at Lyktos three times in 40 years, in 1894, 1914 and 1924. These campaigns are largely unknown in scholarship, but can be reconstructed on the basis of archival material held by the Italian Archaeological School at Athens. The richer documentation for the campaign of 1924 is essential for the reconstruction of the earlier campaigns, which is why all three are discussed together in this section.

Important information on the three campaigns at Lyktos is provided by the unpublished series of notebooks (taccuini) titled Iscrizioni Cretesi, which are in the archives of the Italian School. Although used by several Italian pioneers of Cretan archaeology to document their epigraphic-oriented fieldwork in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the notebooks are known as taccuini Halbherr. The taccuini formed the basis of the monumental four-volume publication Inscriptiones Creticae by Margherita Guarducci (Reference Guarducci1935–50).Footnote 76 Notwithstanding her interest in the materiality and the archaeological context of Cretan inscriptions, which was exceptional for the epigraphic standards of the time, Guarducci documented these aspects only occasionally and did not always make use of essential contextual information provided in the taccuini Halbherr, as demonstrated below with reference to Archaic and Roman inscriptions from Lyktos, and as documented elsewhere for inscriptions from Eleutherna (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas and Gavrilaki2018b). This bias is understandable in light of the priorities of epigraphy at the time, but it does not support the idea that Guarducci ‘paid close attention to the context of particular [epigraphic] finds – indeed her attention to both context and physical form make her (arguably) an exemplary “contextual” archaeologist’.Footnote 77 This section compensates for the bias in Guarducci's approach and draws from the taccuini to reconstruct the find context of several inscriptions from Lyktos which are generally considered as chance finds.Footnote 78

The excavation of Halbherr and Taramelli in 1894 has been overlooked by relevant scholarship (see, for example, Leekley and Noyes Reference Leekley and Noyes1975, 89; Rethemiotakis Reference Rethemiotakis1984, 50; Rizzo Reference Rizzo, Di Vita, La Rosa and Rizzo1984, 68; Momigliano Reference Momigliano2002, 282 n. 82), but is illuminated by taccuino Halbherr 24. This excavation was conducted on 6 August, targeted an area west of the chapel of Timios Stavros, and yielded several Roman inscribed statue bases, which led Halbherr to believe he had located the area of the agora.Footnote 79 The notebook reports that four inscribed statue bases referred to Trajan and that two of them came from the excavation while the other two were chance finds. The excavation also produced an inscribed base for Plotina (Pompeia Plotina Claudia Phoebe Piso), the wife of Trajan, as well as an uninscribed base.

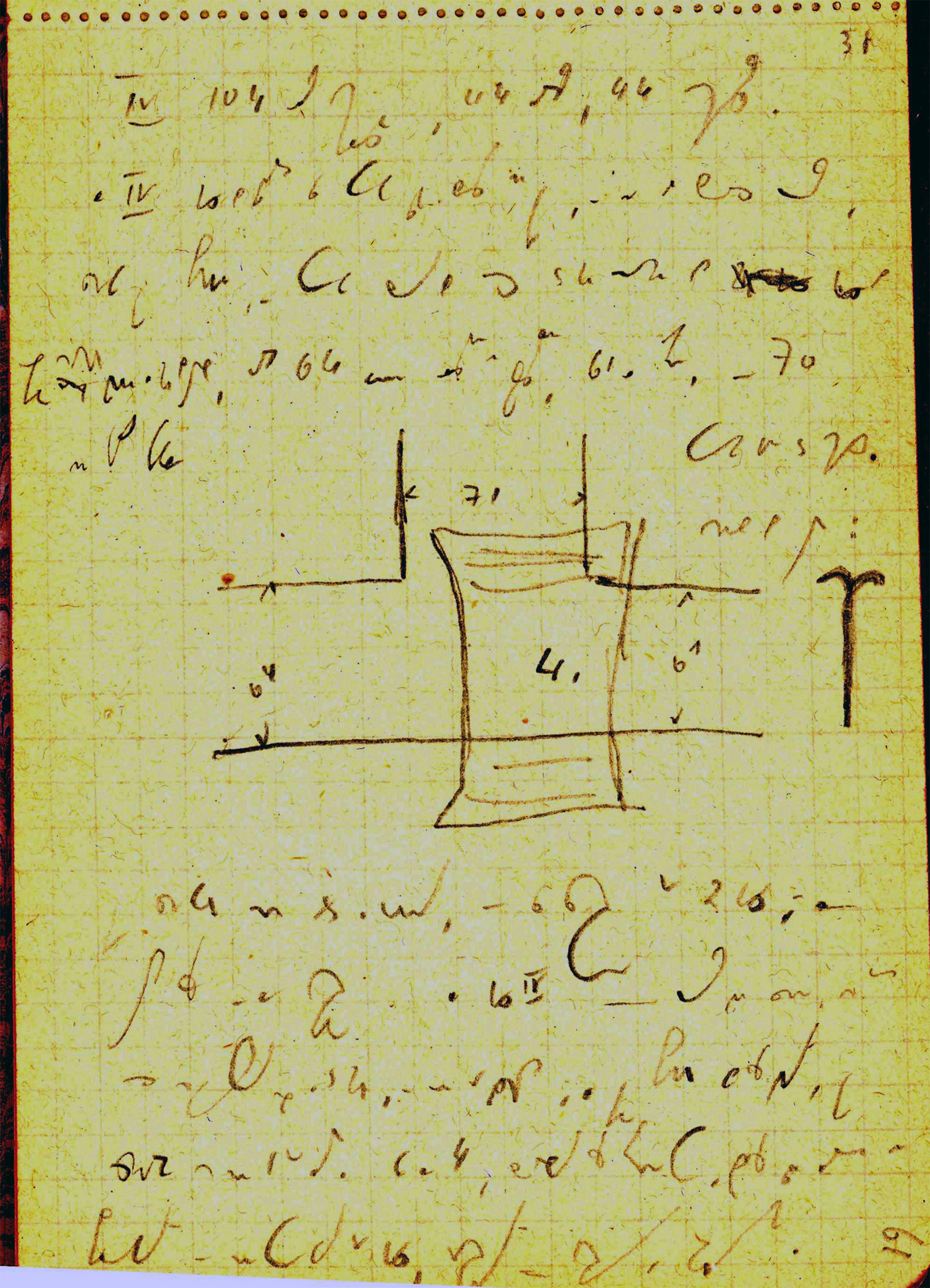

Interestingly, two of the inscriptions in question were rediscovered in the excavation of 1914 (ICr I xviii 22 and 29), which is recorded in taccuinο Halbherr 63 and establishes that the two campaigns targeted the same location. This excavation was probably conducted by Gaspare Oliverio, who was at the Italian Archaeological School at Athens in 1913–14.Footnote 80 Oliverio excavated west of the chapel of Timios Stavros, and revealed a row of four Roman inscribed bases referring to Trajan and his family. Two of these inscriptions had been discovered by Halbherr in 1894, and the other two were new finds (ICr I xviii 23 and 35). Based on Fig. 5, the inscribed bases were lying west of the terrace wall which runs c. 4 m west of the chapel of Timios Stavros (see Fig. 6 and also below).

Fig. 5. Page from the notebook of Oliverio(?) with plan of the location of the excavation of 1914 (taccuino Halbherr 63, pages 30–1; by permission of the Italian Archaeological School at Athens). The plan shows the chapel of Timios Stavros, the terrace wall that supports it, and the lower terrace west of them which supports a Roman monumental complex. The imperial bases marked Ν.7, Ν.8, Ν.9 and Ν.10 are published in ICr I xviii 35, 23, 29, 22 respectively.

Fig. 6. Photograph showing the west side of the chapel of Timios Stavros, the terrace wall that supports it, and the underlying terrace west of them (photograph by author).

It is unclear whether Oliverio targeted the location excavated by Halbherr deliberately. There is, however, reason to suspect that this was not the case in 1924, when Doro Levi returned to the same location for another brief dig (on Levi see Belli and Vagnetti Reference Belli and Vagnetti1990). Levi's fieldwork can be reconstructed on the basis of the brief report he published (Levi Reference Levi1928, 398–403 figs 4, 5; cf. Rizzo Reference Rizzo, Di Vita, La Rosa and Rizzo1984, 68); a letter he sent to Alessandro Della Seta, then Director of the Italian Archaeological School at Athens;Footnote 81 a report he submitted probably to Della Seta;Footnote 82 his unpublished notebookFootnote 83 (Fig. 7); and a series of mostly unpublished photographs in the archive of the Italian School (Figs 8, 9, 10, 11), which are the earliest known photographs of the archaeological landscape of Lyktos.

Fig. 7. Page from the notebook of Levi referring to his excavation at Lyktos in 1924 and illustrating an imperial statue base overlying the remains of a building (from taccuino ‘Levi 1924’ in Folder Α of the Iscrizioni Cretesi page 61; by permission of the Italian Archaeological School at Athens). Note Levi's incomprehensible shorthand.

Fig. 8. Two photographs from Levi's excavation on the acropolis of Lyktos in 1924 (by permission of the Italian Archaeological School at Athens).

Fig. 9. Two photographs from Levi's excavation on the acropolis of Lyktos in 1924 (by permission of the Italian Archaeological School at Athens).

Fig. 10. The Roman imperial statue bases ICr I xviii 22 and 29, which were discovered by Levi on the acropolis of Lyktos in 1924 (by permission of the Italian Archaeological School at Athens).

Fig. 11. The Roman imperial statue bases ICr I xviii 23 and 35, which were discovered by Levi on the acropolis of Lyktos in 1924 (by permission of the Italian Archaeological School at Athens).

Levi visited Lyktos in the context of an archaeological nine-day tour of the eastern part of central Crete he undertook from 7 to 16 April 1924 (La Rosa Reference La Rosa, Belli and Vagnetti1990, 59–62: letter from Levi to Della Seta, 16 April 1924; cf. Levi Reference Levi1927–9, 24; Chatzidakis Reference Chatzidakis1931, 46). He excavated on the acropolis for half a day and discovered a row of six statue bases along the monumental stylobate of a large building (Figs 8, 9; for the building see Fig. 9: lower, and cf. Fig. 7). As Levi confessed to Della Seta, the excavation was conducted without official permit, which is why the trenches were backfilled and the imperial statue bases were left on the spot (La Rosa Reference La Rosa, Belli and Vagnetti1990, 60: letter from Levi to Della Seta, 16 April 1924). Levi intended to publish his excavation in full (La Rosa Reference La Rosa, Belli and Vagnetti1990, 105–6: letter from Levi to Della Seta, 6 May 1925, 121–2: letter from Levi to Della Seta, 4 February 1926) but he failed to do so, probably because of the lack of permit. Besides, the excavation he conducted at the extensive Early Iron Age to Archaic cemetery at Afrati from 12 May to 17 June 1924 absorbed his time and energy in the years that followed (Levi Reference Levi1927–9, 9; cf. La Rosa Reference La Rosa, Belli and Vagnetti1990).

Three of the five bases discovered by Levi supported statues of Trajan, one of his wife Plotina, and one of his sister Ulpia Marciana (Figs 10, 11), and all had been excavated previously by Halbherr and Oliverio (ICr I xviii 22, 23, 24, 29, 35). In his published report, Levi referred to the intentional return to the location excavated by Halbherr and Taramelli in Reference Halbherr1894 for the purpose of clarifying the location of the Roman agora at Lyktos, and he presented the two inscribed bases which had been discovered (though not published) by Oliverio as new finds (Levi Reference Levi1928, 398–403, with reference to ICr I xviii 23 and 35). However, the intentionality of the return can be questioned in light of the letter Levi wrote to Della Seta a few days after the dig, which shows no awareness that the inscriptions he found were previously known.Footnote 84

The site of the excavation of 1924, which largely overlaps with that targeted in 1894 and 1914, and is identified by the excavators with the Roman agora, can be localised more closely in the light of the descriptions and the photographs by Levi. The Italian scholar placed the dig ‘on top of one of the two peaks which crown the hill of Lyttos’ (Levi Reference Levi1928, 398; La Rosa Reference La Rosa, Belli and Vagnetti1990, 59: letter from Levi to Della Seta, 16 April 1924), ‘near the church of Estavromenos’ (Timios Stavros).Footnote 85 This location can be identified securely with the broad terrace which extends 4 m west and approximately 2.5 m lower than the chapel of Timios Stavros, and extends roughly 45 m north to south and 16 m east to west.Footnote 86 I believe that this same terrace is illustrated in the photographs taken by Levi, which show the characteristic contour of a mountain top in the background (Fig. 9: upper). The mountain top can be identified with that lying north to north-east of the chapel of Timios Stavros, as seen in Fig. 12. The small modern construction which appears in Figure 8b does not survive and was perhaps destroyed when the vines which currently occupy the terrace were planted.

Fig. 12. Photograph of the terrace immediately west of the church of Timios Stavros, which was excavated by Halbherr in 1894, Oliverio in 1914 and Levi in 1924. The hilltop in the background matches that shown on Figure 8 (photograph by author).

The secure identification of the location which was repeatedly excavated by the Italians is significant for the study of the topography of Lyktos. However, on present evidence, it is wiser to resist their idea that the Roman monumental complex, the façade of which was adorned by a line of statues of Trajan and members of his family, was the Roman agora (for this idea see above, and also Platon Reference Platon1953, 490; Sanders Reference Sanders1982, 147).

In 1924 Levi identified or collected numerous chance-finds from Lyktos, including an inscribed statue base for emperor Titus, and a few Archaic clay figurines.Footnote 87 From the acropolis he collected the head of a Daedalic female figurine, the head of a bovine and a fragment of a relief pithos (Fig. 13). Also, Levi showed an interest in finds from Lyktos kept in the Archaeological Museum of Herakleio, including fragments of Archaic relief pithoi and a Classical(?) bronze lamp.Footnote 88

Fig. 13. Photograph of finds collected by Levi at Lyktos in 1924 (by permission of the Italian Archaeological School at Athens).

Levi believed that an excavation at Lyktos would shed ample light on Classical Crete (Levi Reference Levi1928, 398). Indeed, he aspired to return to the site in July 1925 and submitted a budget for this to Della Seta (La Rosa Reference La Rosa, Belli and Vagnetti1990, 60–2: letter from Levi to Della Seta, 16 April 1924). However, Della Seta was negative because of the limitation of three excavation permits imposed on the School, and he recommended waiting for a future initiative of Halbherr (La Rosa Reference La Rosa, Belli and Vagnetti1990, 63: letter from Della Seta to Levi, 22 April 1924). This initiative never came, however, and nearly half a century later, in 1967, Levi confessed: ‘If I could ask my god for a favour, as Kazantzakis used to say, I would ask him for thirty more years to excavate Lyktos’ (Detorakis Reference Detorakis1991).

The abandonment of Levi's plan in 1924 was followed by the revival of British interest in Lyktos in 1928. This revival was tied to the intention of the British School at Athens to excavate a Cretan site of the Archaic period (Macmillan Reference Macmillan1927–8, 306; cf. Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2008, 283). It is unclear whether this intention relates to the roughly contemporary fieldwork of the French School in Anavlochos (1929) and Dreros (1932–6), both located north-east of Lyktos (Prent Reference Prent2005, 281, 284–5). However, Arthur Maurice Woodward, then Director of the School, explained in letters to Evans and Humfry Payne that the ideal site would be a sanctuary with rich offerings which would contribute to the identification of the Cretan or Spartan origins of some classes of finds recovered in the School's excavations in Laconian sanctuaries.Footnote 89 Evans explained to Woodward the poor state of preservation of this phase in Knossos and considered other possibilities.Footnote 90 He first mentioned Lyktos, but noted that the site had been passed on to the Italians. He could have added that even if a rich Archaic sanctuary was discovered at the site, its finds would probably not resolve the problem of distinguishing between Cretan and Spartan artefact styles, given the ancient tradition which considered Lyktos as a Spartan colony and the modern perception of the city as ‘a kind of pendant to Sparta’. In the same letter, however, Evans returned to his proposal of 1913 that the School should focus on Eleutherna.

Evans may have given Lyktos a last chance in the days that followed this correspondence. At that point John Devitt Stringfellow Pendlebury and his future wife Hilda White arrived at Knossos and took a short trip to the east.Footnote 91 The couple visited Lyktos for a few hours on 12 May 1928, together with William Dudley Woodhead, Professor of Greek at McGill University, Montreal. White and Woodhead took three photographs of Lyktos: one probably shows the circular Byzantine tower north-west of the chapel of Agios Georgios (Fig. 14), the other the row of windmills further west to north-west (Fig. 15), and the third the pass to Lasithi. It is unclear what the three scholars thought of Lyktos, but in June 1929 the British School commenced excavations at Eleutherna under Payne's directorship. However, Payne was quickly disappointed with Eleutherna and a few days after the end of his excavation he visited Lyktos to evaluate the prospect for fieldwork.Footnote 92 His impression must have been negative, as a few months later he was looking for a site on the Greek Mainland and settled for Perachora in Corinthia (Macmillan Reference Macmillan1928–30b, 282, 285–7). Pendlebury returned to Lyktos several years later, on 2 July 1937, after completing the first season at Karphi, and he spent an hour around the ancient city.Footnote 93 Three photographs from that visit show landscapes of the wider area, and a fourth one the windmills of the acropolis (Fig. 16). Judging by the brevity of his published references, Pendlebury was unimpressed by pre-Roman Lyktos (Pendlebury Reference Pendlebury1939, 344, 361, 372).

Fig. 14. Photograph of an early Byzantine tower on the acropolis of Lyktos from the photographic album of Greece compiled by Hilda White and labelled ‘HWP. Greece, 1927–1928’ (PEN 7/2/3/262, 12 May 1928) (by permission of the British School at Athens).

Fig. 15. Photograph of windmills on the acropolis of Lyktos which was taken by William Dudley Woodhead and is in the photographic album labelled ‘Crete I. 1928–1932’ (PEN 7/2/4/186, 12 May 1928) (by permission of the British School at Athens).

Fig. 16. Photograph of windmills on the acropolis of Lyktos in the photographic album ‘Crete III. 1932–1939’ (PEN 7/2/6/664, 2 July 1937) (by permission of the British School at Athens).

The ventures of the 1920s mark the end of the Italian and the British plans for excavating Lyktos. Although Italian and British epigraphists returned briefly to the area and identified Roman inscriptions shortly before and shortly after World War II (Guarducci Reference Guarducci1935; Jeffery Reference Jeffery1949, 38), international interest in Lyktos has hitherto remained very limited.

GREEK FIELDWORK IN THE POST-WORLD WAR II PERIOD AND THE REVIVAL OF INTERNATIONAL INTEREST

The exploration of Lyktos after World War II largely consists of small-scale excavations by the Greek Archaeological Service, occasionally with support from the Archaeological Society at Athens. The monuments and portable finds exposed by these excavations have hardly been contextualised before, especially because of the limited topographic information provided in the brief published reports. This section compensates for this limitation by reconstructing the history of the different campaigns and by plotting their location on the map of Fig. 17.

Fig. 17. Map of Lyktos. Shaded areas show locations mentioned in preliminary fieldwork reports. Numbers indicate excavated buildings, the location of which can be identified with precision: 1. Roman monumental complex targeted by Italian scholars in 1894, 1914 and 1924; 2. Late Roman shops explored by Rethemiotakis; 3. Hellenistic house excavated by Rethemiotakis; 4. Roman monumental building with niches noted by Evans and Hogarth and explored by Rethemiotakis; 5. Roman ‘bouleuterion’ excavated by Rethemiotakis. Map created by Vyron Antoniadis with advice by local informant Konstantinos Chalkiadakis.

The first years after the war were particularly difficult for the Archaeological Service on Crete, which was seriously understaffed and underfunded. The heroic efforts of Nikolaos Platon, then Ephor for the whole of Crete, were rewarded by the appointment of Stylianos Alexiou in 1950, while the newly established journal Kretika Chronika provided a venue for detailed reporting of archaeological fieldwork (Platon Reference Platon1949, 591–3; Reference Platon1950, 529–32). These developments facilitated the resumption of limited but recurring work at Lyktos. Platon visited the site several times and was accompanied by Levi on one of his first visits. He collected numerous monuments, including a marble statue and a poros statue of goddess Hygeia, which had been taken by German troops to the village of Archangelos (then called Varvaro) south-west of Kastelli (Platon Reference Platon1949, 596). From Lyktos itself he collected several statues, including a marble head of Trajan or Nerva; several inscriptions, including a Late Archaic opisthograph inscription on a limestone capital and a Roman inscription for Vibia Sabina, wife of Hadrian; a gold bead shaped into a feline head (from the location Sfako stsi Lakkous, south-east of the site); a Roman sealstone with a chariot scene; and an Early Christian capital with acanthus leaves.Footnote 94