Introduction

The author's first winter at Barrow, 560 km (340 miles) north of the Arctic Circle was that of 2004. Barrow is the northernmost permanent settlement of the United States. With a local history that reaches well into the era before Euro-American contact, the area was developed as a trading post between the Iñupiat and the American whalers in the late 19th century. The village embraces nearly 4,500 people today. One week before Thanksgiving, on 18 November 2008, the village had entered the long night that would last until late January. The author attended a Thanksgiving service at a local church and enquired if Nasuk, a prominent member of the community would drum dance on the occasion. In Iñupiaq communities, a musical performance almost always follows a feast. Nasuk, a respected whaling captain was also known as a skilled traditional dancer. But he indicated that he would not: ‘[n]o whale, no music.’Footnote 1 That spring, Barrow had experienced a challenging whaling season with only 6 whales landed, and Nasuk's family was not among the successful crews. Although the autumn hunt compensated for the insufficient spring outcome, Nasuk's crew had been again unable to land a whale. Moreover, many whalers appreciate spring whales more than autumn whales because of the spiritually heightened and physically intimate interactions with the whales under extreme conditions. ‘Hunt on the ice, that's what makes our whaling real and special’ as the author was informed by a retired whaling captain once.

For village performances, according to Iñupiaq custom, it is only the successful umialik (whaling captain and his wife) and their crew who formally open up the floor and dance for the whale. While everyone else was invited to join the dancing circle after the successful umialiks performed their dance, Nasuk was determined to remain a spectator that evening. He stated his view: ‘[k]eep this in mind. It is the whale who brings us music. You need to be chosen by the whale to be a good dancer and a captain’ (Brower Reference Brower2004).

This article explores the result of the author's fieldwork in the North Slope Borough whaling communities in 2005–2006. As a member of 2 Barrow whaling crews, the author participated in 4 seasonal hunts, each with varying degrees of success. While based in Barrow, the author also spent a good deal of time in Point Hope where, in addition to participant observation, ethnographic interviews were conducted. Despite being the 2 largest of the North Slope Borough villages, the villagers of Barrow (Ukpeagvikmiut) and Point Hope (Tikigaqmiut) maintain an active subsistence lifestyle. Year round subsistence activities such as fishing, sealing, and caribou hunting culminate into the spring whaling that takes place in April and May. Both Ukpeagvikmiut and Tikigaqmiut depend upon the bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) for sustenance and cultural meaning, and the people call themselves the ‘people of the whales.’ The whale that weighs approximately 3 tons per metre and grows up to 21 metres remains central to their life and the foundation of traditional ceremonies. The Iñupiaq calendar, the whaling cycle, is filled with meticulous preparation for whaling at various times of the year. The oneness between humans and whales lies in the centre of the circle of life. In the whaling cycle, before and after the annual hunting season, men and women conduct an elaborate series of rituals accompanied by the whale drum and the human voice. This symbolic and collaborative reciprocity culminates in the actual whale hunt in which the whale gives itself to the respectful hunters. As one of their origin stories reveals, the death of the whale coincides with the birth of the Iñupiat and their homelandFootnote 2 (Edwardsen Reference Edwardsen1993; Lowenstein Reference Lowenstein1992, Reference Lowenstein1993; Kean Reference Kean1981; Frankson Reference Frankson and Simmonds2002). By influencing the whale's migration timings, routes and population, many Iñupiat feel that climate change directly threatens traditional lifeways and well being (Akpik Reference Akpik2005; Brower Reference Brower2005; Frankson Reference Frankson2005a; Kazlowski Reference Kazlowski2008; Kaleak Reference Kaleak2005; Wohlforth Reference Wohlforth2004).

As climate change necessitates cultural transformation in Iñupiaq communities, tension is transmitted to the levels of human emotion and continuity of expressive culture in various ways (Sakakibara Reference Sakakibara2008; Wohlforth Reference Wohlforth2004). This article discusses how Iñupiaq musical practices during the annual whaling cycle have been impacted by variable whale harvests, and conversely, how such cultural manifestations are themselves being revealed by associated changes. In so doing, this study illustrates some of the ways in which musical performances such as singing, dancing, and drumming, provide the means for the Iñupiat to construct and mobilise their close tie with the whales. Through personal interactions with Iñupiaq performers, the author found their music is not a static relic of past cultural heritage, but is rather a dynamic emblem of innovation and adaptation to adversity. Pertinent oral historical and archaeological information exists regarding earlier major climate change in the region and Iñupiaq responses to it (Maguire Reference Maguire and Bockstoce1988; Sheehan Reference Sheehan1995; Worl Reference Worl, Kotani and Workman1980). As climate change leads cultural change in indigenous communities, human emotions produce new forms of expressive culture. For many Iñupiat, in other words, musical performance is a means of adapting to environmental transformation. In the author's view, the culture of performance serves as a means to express concerns about, and adapt to, environmental changes. The people of the whales are now attempting to cope with current and future uncertainties through modifications of performance. Iñupiaq performance strengthens their relationship with the whales, and further, provides a way of coping with a world in which they seek to survive.

The heart of this article describes at least some Iñupiat emotional responses to recent environmental problems that directly impact the continuity of traditional performance, especially that of the whale related events that involve drum music. Traditionally, it is through various cultural expressions that fundamental aspects of the whale centric social organisation are recognised, that social time is ritually articulated, and that an entire whaling cycle is completed. Thus, the core of the author's argument is that the current crisis in whaling strengthens Iñupiaq identity through a shift of mindset and emotion to deal with the devastating situation, and through modifications in performance and ceremonies. Performance, with its deep emotional resonance, allows Iñupiat to transcend their boundaries with the whales, especially at this time of continuous change in their environment. The final section of this article describes the imprints of climate change in the whaling cycle and how Iñupiaq performers are surviving the challenge.

Performance, environment, and cultural identity

For the past two decades, social scientists have begun to redefine music as a vital medium of human experience as well as a humanistic way of understanding the world and not just as a cultural product (Attali Reference Attali1995; Frith Reference Frith, Leppert and McClarey1996; Porteous Reference Porteous1990; Wood Reference Wood, Bondi, Avis, Bankey, Bingley, Davidson, Duffy, Einagel, Green, Johnston, Lilly, Listerborn, McEwan, Marshy, O'Conner, Rose, Vivat and Wood2002). As our emotions are deeply entwined with musical experiences and imagination, music invests our world with specific feelings, and also cultivates a communal tie and human identity (Seeger Reference Seeger1987; Stokes Reference Stokes1997). Wood (Reference Wood, Bondi, Avis, Bankey, Bingley, Davidson, Duffy, Einagel, Green, Johnston, Lilly, Listerborn, McEwan, Marshy, O'Conner, Rose, Vivat and Wood2002) elaborates how music is an especially emotive phenomenon among all our human sensory experiences and expresses our sense of place filled with sentiments. Music contributes to the making of collective identity, and its rootedness in place informs our sense of place by evoking collective memories and sentiments. As the work of Stokes (Reference Stokes1997) and Waterman (Reference Waterman1990) reveal, ceremonial performances that include music are not static subjects, but are themselves social and cultural contexts that bring people together and within which other things happen.

Music, song, and dance make us feel in touch with an essential part of ourselves, our emotions and our rootedness in a community, and a place (Schutz Reference Schutz, Kemnitzer and Schneider1977; Stokes Reference Stokes1997). People get together for musical performances by taking the roles of musicians, dancers, and/or audiences. Music and dance are often inseparable, and special food and drink often establish communal musical events as a vital and pleasurable part of cultural identity. In Iñupiaq understanding, it is the whale that brings them this joy and pleasure altogether (Williams Reference Williams1996; Zumwalt Reference Zumwalt and Falassi1998). In other words, the whale is the source of major musical performance, inspiration, instruments, and nourishing ceremonial and communal food.Footnote 3 When Iñupiaq villagers get together to celebrate the whale, pleasure and emotional heightening are always involved in the presence of the sacred animal.

Ethnomusicologists have frequently studied how music transforms itself in contexts of social change, such as how we use music to cope with outside influences and dominant forces at cultural and humanistic levels, especially the response of performers in ‘small’ communities to the encroachments of the outside world (Baumann Reference Baumann1987; Stokes Reference Stokes1997). For example, Baumann's study of the Miri of Northern Sudan focuses on reintegration among the people to illustrate how the Miri attempted to recreate their community in their own terms using songs and dance in the face of the expansion of the Sudanese state, the Arabic language, and Islam into the Miri hills. The Miri ‘domesticated’ the outside world through music as a process of human adaptation at a cultural level. The incorporation and domestication of music difference is an essential process of musical ethnicity. Furthermore, Feld (Reference Feld1990) illustrates how culture and music are inextricably integrated among the Kaluli people of Papua New Guinea and are reflected to human relations to the flora and fauna.

Similarly, Iñupiat seek to accommodate outside influences through their flexible web of music and various degrees of emotions that surrounds it. In this context, performance serves as an adaptive mechanism and a cornerstone of the human integrity with the whales. The author observed how this adaptation process is becoming almost an automatic reaction among the Iñupiaq musicians and participants of the whaling cycle to cope with dominant outside forces and environmental problems that directly impact their whale based ceremonial continuity.

The call of the whale drum

In Iñupiaq performance, the drum encapsulates many aspects of Arctic life and serves a number of functions to heighten Iñupiat-whale relations. It was once a vehicle for the shaman's spiritual journeys, and could also be used for geographical orientation (Frankson Reference Frankson2005b; Kean Reference Kean1981; Lowenstein Reference Lowenstein1992, Reference Lowenstein1993; Oquilluk Reference Oquilluk1981). The whaling cycle rotates around the drumbeat as Iñupiat dance and sing for the whale. Such a simple definition, however, fails to do justice to the importance of performance as a whole. Ernie Frankson, Sr., a whaling captain of Point Hope and the leader of the Tikigaq traditional dancers, pointed out that in the Iñupiaq lifeworld, ‘the drum is the whale and the whale is the drum’ (Frankson Reference Frankson2005b).

The drum is a universally appreciated instrument in the circumpolar region. The logo of the Inuit Circumpolar Conference, a stylised drum designed by Greenlandic artist Ninan Spore Kreutzmann, symbolises the unity among the Arctic peoples. Besides being a common instrument employed across the Arctic, the northern drum is a pan-Arctic symbol of harmonious relations. Drums are symbolic of the inseparability among humans, animals, and environment, which also extends well beyond the Arctic. However, its importance is exclusively heightened in the western Arctic where people treat and respect the drums as the only instrument to accompany their vocal music.

Indeed the drum is the sole musical instrument among Iñupiat. Iñupiaq music is drum music, and the drum is cared for, respected, and ritually fed with fresh water. Feeding the drum with fresh water is important to keep the membrane moist, and there is a metaphorical parallel with the custom of captain's wife's action to feed a hunted whale with fresh water to quench its thirst. In appreciation, the whale begins another journey of life and eventually returns to the village in the following year. Fannie Akpik, a traditional performer and the organiser of the Nuvukmiut dance group of Barrow, explained that feeding water to the whale by the umialik's wife is reenacted through performance by her husband, her children, her crew members, and everyone in the community who sing, drum, dance, and share the fruits of the hunt: ‘[o]ur drum speaks the language of the whale through our performance’ (Akpik Reference Akpik2005). Diana Oktollik, a whaler's wife in Point Hope, gave the metaphor that the ‘drumbeat is the Iñupiat heartbeat,’ which indicates the long perceived kinship between the people and the whales (Oktollik Reference Oktollik2005).

The drum membrane is often made of linings of whale livers, stomachs, or lungs (Fig. 1). According to Frankson, the whale membrane makes a thin yet durable surface by being stretched on a round wooden frame (Frankson Reference Frankson2005b). In this way, the whale, by giving up its life, gains an eternal life as the musical instrument.

Fig. 1. Washing whale skin for drum making. Standing on the sea ice, a crew member washes a piece of the fresh whale stomach skin in preparation for the drum making (Photo by author, 6 May 2005).

On many occasions, Iñupiaq performers act out their kinship with the whales through the drum dance. The inseparability of whaling crews and music is demonstrated by umialiks who are also skilled drummers, singers, and dancers, and are responsible for organising and performing drum dances. In Barrow, two major traditional whale feasts in the whaling cycle are apagauti, a feast that is held on the icy beach to conclude the spring whaling, and nalukataq, the midsummer highlight of the cycle of life. In Point Hope, apagauti is part of their three day nalukataq celebration. The American festival of Thanksgiving and Christmas have also become an integral part of the villagers’ lifeways, replacing the original events that historically had taken place in similar time frames (Bodenhorn Reference Bodenhorn2001; Turner Reference Turner1993).

Drumbeats emotionally facilitate dialogues between human and animal characters in their accompaniment of tales, lullabies, syllables, and lyrical songs. Akpik stated: ‘[d]rum music opens the communication between humans and whales (Akpik Reference Akpik2005). George Kingik, former mayor of Point Hope, explained this interspecies communication brings invaluable lessons to whalers:

Drumming and whaling are one. Music, like our songs and dance, teach us how to wait for the whale, [how] to communicate with the whale, [how to] harpoon the whale, [what to do] after the hunt, [and how] to pay respect to the whale. These respects [toward the whale] all grew out of our drumming tradition (Kingik Reference Kingik2005).

As the drum calls the animals, hunters may use hunting songs to lure and capture them (Brewster Reference Brewster2004; Johnston Reference Johnston1977; Reimer Reference Reimer1999). The connectivity between the drums and the whales is also revealed in an origin story of the Iñupiaq drum songs. Frankson elaborates:

Animals come around with drums. All our songs and drum beats were originally inherited from animals. That's why all rituals exist: to retain animal spirits in the drums. Songs are [the] agent, [the] mother of all animals, and they can be demanding because [drums] need good care and respect like animals. We have to sing animals’ songs. If we do, they will come near. Materials are acquired in our life from animals, and all rituals are for them [to appreciate their existence in our life]. We use their bones for shelter, skins for drums and clothing, meat for food. When animals are caught, killed and taken home, they should be treated as our guests in the house. Animals we kill become the guests of the house and need to be pleased with their songs and drums. (Frankson Reference Frankson2005b).

Songs are the gifts from the animals, and hunters and their families are responsible for entertaining their animal spirit guests. Drum performances activate powerful interactions between performers and animal spirits. This reciprocity is strongly reflected in the revitalized tradition of Kivgiq, the messenger's feast. Kivgiq invites other community members to exchange songs, dances, and gifts (Riccio Reference Riccio1993, Reference Riccio2003). According to the late Vincent Nageak, Sr., an elder of Barrow, animals brought this event to the Iñupiat (North Slope Borough 1993). Until then, there was no music or drums among the Iñupiat. This reciprocity between animals and music is particularly pronounced between the whales and the Iñupiat. Willie Nashookpuk, a whaling captain of Point Hope, elaborated upon the strong ties among the whales, dances, songs, and hunters:

Whale songs are attributed to [whaling] families, and [each] whaling crew needs to have [its] own dance. These songs and dances came from the whales. When you catch a whale, take out [its] flesh and breathe life into it-then you would be blessed with powerful songs. There are many songs that came out of this custom. (Nashookpuk Reference Nashookpuk2005).

Rex Okakok, Sr. of Barrow explained the kinship between the whale and the drum music by confirming the Iñupiaq rootedness to their land:

If you eat a whale, you need to return to the place [where you consumed the whale]. If you hear the drum music, you need to return to the place; we are connected to our home through a bloodline with the whale. Our ancestors cultivated kinship with the whale and their place through our ceremonial relation with the whales. That's why we sing for the whales and drum for them . . . The whale is our food and music, and the whale is who we are (Okakok Reference Okakok2005).

The whale and the Iñupiaq identity become interchangeable through a continuous drumbeat. Okakok's interpretation particularly draws a parallel with the land-whale story of Point Hope in which the whale is the origin of the Iñupiaq homeland.

Through words or simply syllables, songs also unify the Iñupiat and the whales. Recalling the historical bladder feast, which missionaries later replaced with Thanksgiving, Majuaq, an Iñupiaq elder, told Knud Rasmussen in the 1920s how intimately the ceremony had tied songs to their whales:

Every autumn, we held big feasts for the soul of the whale, feasts which should always be opened with new songs which the men composed. The spirits were to be summoned with fresh words; worn-out songs could never be used when men and women danced and sang in homage to the big quarry (Rasmussen Reference Rasmussen and Ostermann1952: 102).

Majuaq stated that until the appropriate words came into his people's minds, they needed to sit in deep silence and darkness so as not to disturb the whale spirit. Rasmussen continues to cite Majuaq:

It was this stillness we called qarrtsiluni, which means that one waits for something to burst. For our forefathers believed that the songs were born in this stillness, we all endeavoured to think of nothing but beautiful things. Then they take shape in the minds of men and rise up like bubbles from the depths, of the sea, bubbles seeking the air in order to burst. That is how the sacred songs are made! (Rasmussen Reference Rasmussen and Ostermann1952: 102)

Songs and whales are the blessings from the sea. The whale drum performance develops this relation through the melding of human voices and drumbeat in the coastal communities. Similarly, Iñupiaq drumming is a process of putting various lives together by assembling several animal body parts. While the major drum membrane medium is the whale, the drum historically had a decorated handle made from walrus tusk (now frequently wooden handles). This handle connects the human body and the instrument (the whale) as the player grips it, and symbolically links humans, whales, and sea. Just like Sedna, the Arctic sea goddess whose body parts turned into Arctic sea mammals, the drum is a composite being. Sedna is also known as Nuliajuk (in Nunavut and in the Northwest Territories), Arnarquagssaq (in Greenland) and Nerrivik (in northern Greenland), and is a sea goddess who universally appears in Arctic folklore. She was a human once but was reincarnated into a deity after her tragic death. According to several stories, it is from her finger joints that the marine mammals (whales, seals, and walruses) were born, and her anger deprives humans from successful animal harvest thus causes serious starvation. For more information, see Laugrand and Oosten (Reference Laugrand and Oosten2008).

With a few exceptions, the text of the drum dance song is often meagre. Within the song texts, words are interspersed with syllables. Many songs have only the syllables eya, or ha-ya or aayaaa-yaayaa or yaiyaa, all of which refer to the action of singing (Akpik Reference Akpik2005). The audience is usually sufficiently familiar with the songs and their subjects to fill in most of the meaning (Akpik Reference Akpik2005). This frequent use of syllables, a shared musical trait with their circumpolar neighbours, emphasises feelings, emotions, and ‘fill[s] in incomplete thoughts’ to add further humanistic elements that are not necessarily based on a predetermined system.

‘Our songs are all about whaling. We speak to whales through drums and the drums bring us whales’ (Okakok Reference Okakok2005). As Okakok explained, if the performers respond to the animals and dance for them, the animals return to the Iñupiat. Whale related drum performances fill the entire autumn, winter, and early spring, bringing Iñupiaq whalers a full circle into the following whaling season. This cyclical understanding of music-animal integrality anchors drum beats in the centre of the whaling cycle.

Qalgi provides the ceremonial space for Iñupiaq performance. In ceremonial contexts, qalgi may refer to either indoor or outdoor space or clan related land. The term may also refer to a dance house built on ceremonial ground (Larson Reference Larson and McCartney1995). In the past, inflated marine mammal bladders hung in the qalgi contained iñua, the spirits (Fitzhugh and Kaplan Reference Fitzhugh and Kaplan1982). After the feast, the marine mammal bladders were returned to the sea through an ice hole for merciful reincarnation (Fitzhugh and Kaplan Reference Fitzhugh and Kaplan1982). Recently, qalgi have been set up at school gymnasia, but the nature of events remains the same. At the qalgi, the villagers sing songs and perform the drum dance to please the whale spirit. In fact, whaling songs and drum music for the whales are composed at qalgi and belong to the qalgi site or land. Therefore, when old town of Point Hope lost five qalgi to the sea and the town was relocated in 1977, the songs and dances of the qalgi disappeared with the land (Sakakibara Reference Sakakibara2008). Regarding the relationship between performance and cultural identity, Oktollik remarked:

Important songs and dances have sunk into the sea . . . but in gatherings . . . our songs and dance continue to provide a special enlightenment, a special happiness. We must carry on our tradition to survive, even if it means to change our ways a little (Oktollik Reference Oktollik2005).

The Iñupiaq happiness in the post-whaling phase is most clearly demonstrated in nalukataq, the midsummer highlight of the whaling cycle celebrated with sharing of food, music, and performance at qalgi.

Nalukataq

Physical and spiritual Iñupiat-whale relationships are best revealed by nalukataq, the major celebration of the whaling cycle. Nalukataq occurs in late June just as the sun is moving towards the summer solstice. The whale gives itself to the hunter, and the hunter then gives it to the participants in the feast. As the spring whaling winds down in late May, the crews that landed whales begin the preparation for nalukataq, which involves at least an intensive one month preparation period to ‘get everything right.’ Men hunt geese, caribou, and seals to acquire meat to serve on nalukataq in honor of the whales. Night and day, women process and cut up chunks of muktuk (the bowhead whale blubber), whale meat, and any wild game brought home by mainly the male members of their whaling crews. The successful captain's wife has her own responsibility to make mikigaq (fermented whale meat and muktuk), which requires constant care and attention. To process muktuk and to clean intestines, and to separate fat from meat an ulu (a semi-circular woman's knife used in the circumpolar world) is used.

On a nalukataq day, visitors come from other North Slope villages, Anchorage, Fairbanks, and as far away as the ‘Lower 48’ to enjoy the good food, music, and festivity under the midnight sun. The event develops as the successful whaling crews serve food to the villagers and visitors in outdoor qalgi. The occasion confirms traditional interspecies connectedness as the whale is complemented with frozen white fish, walrus, duck, geese, caribou and other game as well as the humans who appreciate these animals. Iñupiat participants themselves become the whale through consumption of the whale. A nalukataq day would convince any observer that the people of the whales were indeed made of the bowhead whales with the endless consumption and appreciation of them. All day the participants sit down on their qalgi ground to enjoy this cycle of life. While Barrow has been in various states of dryness/dampness since 1980, regardless of the legal status of alcohol, no alcohol is served as part of nalukataq (also see Bodenhorn Reference Bodenhorn and Miller1993).

Occasionally, Iñupiaq hymns or gospel songs are sung in accompaniment of a guitar and a banjo to heighten the excitement during the day at the qalgi; the music shifts to the traditional drumbeat toward the end of the day under the midnight sun (Fig. 2). This musical duality reminds us of tenacious Iñupiaq adaptability that ultimately encapsulated Christianity and technology into their traditional whale-centred worldview. In spite of radical changes that the Iñupiat experienced on different levels after the 19th century, the core of the traditional performance, especially the link between music and the whales, remains culturally intact (Akpik Reference Akpik2005; Frankson Reference Frankson2005b). While most mask dance and animistic ceremonies were banned as shamanistic, the Iñupiat managed to retain drums as the only and most powerful instrument of their expressive tradition although for some time they had to go underground. At Thanksgiving and Christmas, the villagers hold feasts at village churches during the day and the dancers head out to their qalgi for drum dance in the evening. In spite of the separation of space between a church (gospel) and a qalgi (drum music), both elements are now unified and are inseparable in the making of contemporary Iñupiaq lifeways as a whole.Footnote 4

Fig. 2. An Iñupiaq drumming scene. Tagiugmiut dance group led by Vernon and Isabel Elavgak, Barrow, perform to conclude a nalukataq day (Photo by author, 21 June 2008).

On a nalukataq day, once the serving is done, the crew members go home to put on their new parkas and special boots called kammiks made of caribou, wolf, and seal skins. Nalukataq literally means the ‘blanket toss’ or ‘dancing in the air’ (Rainey Reference Rainey1947; Zumwalt Reference Zumwalt and Falassi1988). Everyone takes pleasure in being bounced into the air on a ‘blanket’ (Fig. 3). The blanket is made from the bearded seal skin cover of an old umiak (whaling boat) that has been removed and converted into a large circular or rectangular sheet with sturdy rope handles. The blanket later covers the qalgi ground for the communal drum dance. Successful umialiks and their crews are the first to be tossed up into the air. They throw gifts of candy and chewing gum from the air. Sounds of excitement and admiration for the jumper's height, flexibility, grace, and style, as well as laughter for those who fall awkwardly fill the outdoor qalgi space. When everyone's feet finally grow too numb to keep bouncing on the blanket, the nalukataq day culminates with the drum dance, the festive conclusion of the ceremonial feast. In this occasion, the people leave the ceremonial outdoor qalgi to a larger indoor space such as a high school gym.

Fig. 3. Nalukataq (blanket toss). Gary Hopson of Barrow dances in the air after midnight (Photo by author, 20 June 2005).

Drumming for the whales

A traditional Iñupiaq drum dance consists of a number of drummers, from 5 to 20, mostly males organised around prominent whaling captains (Fig. 2). Hunters are also musicians. Drummers are also singers, and line one side of the performance space, sitting on chairs, the floor or the ground with their feet stretched in front of them. Behind them sit their wives to support them in chorus. Dancers stand in front of them. Akpik described the movements and choreography of the hands, arms, head, and legs that characterise their performance as evocative of and inspired by animal behaviour (Akpik Reference Akpik2005). Dorcas Rock of Point Hope pointed out that many dance movements depict harpooning, stalking, shooting, butchering, hanging meat or skins, and skin sewing (Rock Reference Rock2005). Male participants often cry out ‘ooh ooh’ in excitement, sounding like a walrus grunt. The same cry is also heard on the sea ice after a whale hunt, metaphorically bringing the sea to the land.

Such performance re-enacts the whale hunt. As Rock and Akpik confirmed, the most common theme in Iñupiaq performance is hunting, which is accompanied by active dancing. Other popular themes include folktales about ancient heroes, legendary figures, mysterious animals, and non-human beings (Rock Reference Rock2005). In honour of the whale, Akpik states that all dancers must wear gloves to show respect so that the ‘ancient hunting spirits and [animal spirits] could stay in the dancers’ bodies’ (Akpik Reference Akpik2005).

Drums are held in the left hand and are beaten with thin flexible wooden beaters held in the right. As the beater strikes the frame, it produces a series of rap sounds. Between each pair of drummers, there is a water bottle to keep the drumhead moist while it is played. This arrangement gives greater resonance to the tone and protects the fragile membrane from being torn, and it reminds the players of how the whale should be fed with fresh water after the hunt.

Both drummers and dancers dress in proper dancing attire, usually kammiks and a long over-garment called an attigluk or snow dress. The dancing begins when a man, usually a successful whaling captain, steps out to the centre, faces the drummers, and puts on his gloves. After his dance, another man, often a co-captain, steps forward. The single dancing is usually followed by motion dancing (sayuun) performed by two or more people, often umialiks.

The late David Frankson noted sayuun songs contain ‘meaningful words’ (Frankson appeared in Johnston Reference Johnston1975). Ernie Frankson, Sr., the son of David, elaborated on this by pointing out that this dance ends with a whaler's dance in which all whaling captains perform. Eventually the floor becomes open to everyone for group dancing (attuutipiaq) (Frankson Reference Frankson2005b). Attutipiaq is a song with or without meaningful words in which dancers are free to create their own movements. Taliun is a song women and girls dance to while sitting on the floor or in chairs facing each others’ backs and moving their arms and hands in fixed patterns, re-enacting the role of an umialik's wife. Attugaurat is an improvisational fun dance like attuutipiaq with a faster rhythm (Frankson Reference Frankson2005b). The Iñupiat enjoy a variety of dance, drumming, and singing through the night, bonding them within and beyond the village unit on festive occasions.

It may be noted that there are regional distinctions regarding dance patterns and song distributions from one village to another although there are shared commonalities. Point Hope dancers (Tikigaq traditional dancers) in particular are known as the keepers of tradition while the four Barrow dance groups are known for their innovation and creativity.

Sea ice contrast: years 2005 and 2006

For many Iñupiat, climate change began to interfere with human-whale relations by not letting the whales give themselves to the hunters. According to Earl Kingik, (Reference Kingik2006): ‘[t]hose poor whales out there in the ocean that we depend on. Are they going to come back to us? Are they going to really show up next year, like our ancestors always expected them for 20,000 years? We are heartily concerned.’ Many Iñupiaq interviewees emphasised that the ice condition was out of the ordinary in both 2005 and 2006.

The spring whaling in 2005 and 2006 exemplify extremes in the spring weather and hunting conditions. In the following, the two spring seasons are compared as examples of extremes in which hunting success was markedly different between the two seasons with their extremely high and low productivities. The gaps in environmental conditions and whale harvest levels indicate changes are underway.Footnote 5

Spring 2005

Spring 2005 whaling was successful, a real boost after the decline of whale harvest experienced in the spring of 2004 in which only 6 whales were landed. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) whaling quota for Barrow (22 whales) was reached on 23 May by landing 16 whales and losing 6. The whalers declared the season's ‘cease fire’ before the end of the spring bowhead migration period. Point Hope whalers also had a productive hunting season by harvesting 7, close to their quota of 9 whales. In spite of the rough and thin ice, and despite the fact that the polar ice cap size has been reduced to its smallest extent in the summer, the constant east winds kept the lead open (Fig. 4). As a result, the bounty of whales uplifted whalers’ spirits and sustained the year's whaling cycle. Yet, according to Ben Nageak of Barrow, former Director of the North Slope Borough Department of Wildlife Management, the sea ice movement increased its unpredictability:

Fig. 4. Sea ice in the Beaufort Sea, July 2005 (Countesy of the NASA Earth Observatory).

‘[l]ast fall [2004], the sea ice didn't form until very late in the winter. The ice melted or went off too soon . . . soon after we stopped whaling. We don't see any trace of sea ice from the Point. There's just too much open water, the ocean is ice-free, and it had never been like this before to this extent (Nageak Reference Nageak2005).

Repeated incomplete freezing in the winter and early thawing of the sea ice in the spring means that the ice that appears can be piled up by the wind, creating very rough conditions and many obstacles to travel by snowmobile which begins once the ice freezes up permanently. Late season storm surges, unprotected by ice, are currently contributing to severe coastal erosion and affects roads across Arctic Alaska. Many Iñupiaq interviewees emphasised that the ice condition was out of the ordinary in both 2005 and 2006. Beyond each ridge, a jumble of broken ice continued until the next ridge appeared. The whalers referred to this condition as ‘junk ice,’ ‘crazy ice,’ or ‘rebelling ice.’ Under these circumstances, the whalers were worried if the collection of new ice would hold without breaking off during whaling. They also wondered if the thin ice could attract the bowhead, and if the whalers could find a strong, large, flat place to pull up a whale securely after the hunt. In spite of the productive whaling season in the spring 2005, in retrospect, future difficulties could already have been expected for the following spring.

Spring 2006

In stark contrast to the 2005 season, the whalers of both Barrow and Point Hope had a difficult whaling period in the spring of 2006 due to limited access to open waters. The inhospitable 2006 spring environment brought only 3 whales to Barrow and none to Point Hope, far below their typical harvest levels. ‘No open water,’ many whalers grumbled. It was a sharp contrast from record areas of open waters in the previous spring. Across the North Slope, there were only 5 successful whale harvests in the spring 2006, 2 in Wainwright and 3 in Barrow. The number is exceptionally small compared to the total of 27 whales landed by the villages of Barrow, Wainwright, and Point Hope in the spring of 2005. An elderly captain stated that the 2006 spring season harvest in the North Slope Borough was the lowest in the past 35 years.

A majority of whalers blamed ‘stubborn’ sea ice, unseasonable and inconsistent wind directions that kept the lead closed, and the changing fluxes of oceanic currents that disabled the formation of open leads by pushing the ice firmly to the shore. Even when a lead was open, the situation was problematic; there were several instances in which the harpooned whales went beneath the thick ice and died where the hunters could never retrieve them (Ahgeak Reference Ahgeak2006). The whale meat was spoiled as the hunters were agitated on the ice. A whale lost after a strike and later found dead is called a ‘stinker’ as its death cannot nourish Iñupiaq life yet the whalers are responsible for collecting the body and cleaning it. Furthermore, the ‘stinker’ is counted toward the annual quota of whale harvest set by the International Whaling Commission.

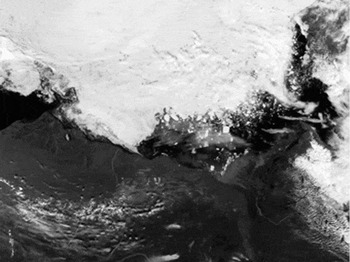

The aerial image (Fig. 5) reveals how the Beaufort Sea experienced the tremendous concentration of ice almost to the shore as late as 25 July 2006. The solid white expanse of ice almost completely hides the blue-black sea surface. The texture of rough chunky ice that the whalers called ‘junk ice’ is also visible on the photograph where new ice has formed around pieces of older ice from previous years.

Fig. 5. Sea ice in the Beaufort Sea, July 2006 (Courtesy of the NASA Earth Observatory).

In retrospect, there was already a sign of unusual weather between the winter of 2005 and the early spring of 2006. The winter experienced an excessive sea ice freeze up that had not happened in the past few decades (Akpik Reference Akpik2006). The whalers were initially happy to see the multi-year ice approach, knowing a solid shorefast ice would provide them with safer travel routes to whaling camps. Recently, little multi-year ice (piqaluyak) had appeared off the shores of Barrow and Point Hope. Multi-year ice can grow as large as 15 meters thick. Sometimes multi-year ice is solid enough to make a strong ground for pulling up whales, and it anchors the shorefast ice in place with its great mass (Glenn Reference Glenn2005). Young ice or first-year ice, in contrast, is thin and fragile. With little flat ice (ignignaq) to work with, it is getting increasingly difficult to cut a trail to open water and to locate a secure spot to build a stable whaling camp. Undoubtedly, it is also becoming more challenging to locate a stable spot to set up a block-and-tackle to tow the whale so as not to lose human lives or the whale to the ocean since the shorefast ice often cracks during the installation.

In theory, the unusual ice concentration of the winter of 2005 and the spring of 2006 would have promised crews a safer whaling and butchering environment. In late January 2006, however, two ice surges (ivus) sent large blocks of ice crashing ashore like frozen tsunamis. Thick multi-year ice had shoved younger, thinner ice onto shore, producing large blocks accumulating (6 m high and 30 m long) (Anchorage Daily News 2006). The tremendous amount of ice confined the Point Hope hunters to the shore literally until the end of the summer (Lisbourne Reference Lisbourne2006). Westerly winds also drove considerable multi-year ice along the coast completely choking the nearshore leads.

The lingering ice seemingly contradicts the idea of global warming and the loss of multi-year ice. Still, conditions suggest climate change is an apt description for what is happening. The NASA Earth Observatory (2007a) explains that this case confirms the increasing unpredictability of the recent Arctic environment. First, temperatures in the sea suddenly dropped below average in the autumn of 2005 and remained cool in the Beaufort Sea region, which allowed sea ice to form quickly. Thick multi-year ice from the north drifted into the Beaufort Sea because of the record melting of sea ice during the summer before. It eventually hit the seasonally ice-free coast of Barrow and concentrated by the shore. Some of the multi-year ice remained frozen in the sea among the first-year ice that formed over the winter, creating the rough surface. Finally, strong west winds pushed more ice toward the shore causing the ivu (ice surge) phenomenon, which resulted in the lingering multi-year ice in the Beaufort Sea at the end of July 2006. According to NASA Earth Observatory (2007b), this unusual sea ice concentration demonstrates that the Arctic as a whole is continuing to melt at an ever quickening pace.

Because of the ice, the 2006 spring whaling was delayed and the whalers missed the majority of the spring bowhead migration. By early July when the lead was finally secured, the sea ice was too fragile to set up camps. The lead was also too wide to hunt from an umiak. Dense summer fog came from the south with high winds and stayed in the village for a number of days, cutting off the community from the rest of the world. Iñupiaq ability to travel was highly influenced as well. Stranded by the ice and fog, the villagers felt helpless just to be in Barrow and Point Hope during such a time of subsistence difficulties.

The insufficient whale harvest made the villagers hungrier than ever; it was a starvation at emotional and spiritual levels. ‘No whale yet. We have no food to eat, and we are getting skinnier day by day’ (Kinneeveauk Reference Kinneeveeauk2006). With the term ‘skinnier,’ Kinneeveauk referred to the Iñupiaq belief that the whale makes an Iñupiaq individual a real and whole person. Western ‘store foods’ fill their stomachs and save them from starvation, but the majority of Iñupiat feel that they do not have the nutritional value to meet the needs of the northern peoples. ‘It is the red meat. Our strength is born from the dark red meat of the whale’ according to one harpooner in his late 20s (Solomon Reference Solomon2006).

The recent popularity of western foods started a questionable trend in Iñupiaq health although dependence has been increasing for decades, and occasionally the store products saved people from starvation some of which was caused by overharvesting by commercial whalers and some of which was caused by seasonal downturns in animal population (Burch Reference Burch2006; Blackman Reference Blackman1989; Boeri Reference Boeri1983; Brower Reference Brower1994). With the lack of whale harvest, both in Barrow and Point Hope, conversations were muted even during family get togethers; men were tired of waiting and women became restless without getting fresh muktuk to process and to give away. With only 3 whales, the annual nalukataq was rather quiet in Barrow.

In 2006, the relationship between insufficient whales and rising social tensions became obvious. The inadequate whale harvest caused social distrust among the villagers. Some suspected others of breaking taboos and offending the whales and driving them away. These tensions also disrupted crew teamwork. Several whalers mentioned communal disharmony and anxiety caused by the high level of stress, and completely rejected any question about whether the tension possibly arose from other causes. This question regarding how adversity is perceived and processed is crucial in understanding the intricacy of the human-whale-environment triad, but is not necessarily straightforward.

Whales, performance, and climate change

An abundant whale harvest brings the season of celebration with songs, dance, and food. The productive 2005 spring whaling season in both Barrow and Point Hope brought a vibrant summer to these whaling villages. With 16 whales landed, Barrow had 4 nalukataq days, each hosted by 3 to 4 successful crews. The villagers shared the whales, acknowledged the bounty, and enjoyed the blanket toss. The drum dance in Barrow, however, had been cancelled due to continuous deaths in the village for the first 3 nights of nalukataq, possibly out of respect for Christianity. However, the joy and gratitude to the whales broke out on the very last night. Eugene Brower, Sr., one of the successful whaling umialiks who co-hosted the last nalukataq day with other captains, expressed his view:

Drum dance is a [crucial part of] the cycle of life that has to come at the end of each celebration. This is a whaling ceremonial that needs to continue, and we have to finish this cycle. Our people's passing is sad, but we can't change what has happened in the village. What's more important is we have to carry on and dance to finish the cycle to keep getting the whales back to us next season (Brower Reference Brower2005).

Brower's emphasis is on the continuity of the whaling cycle. On the last nalukataq night, a drum dance took place in the outdoor qalgi immediately following the blanket toss. It was so spontaneous that it seemed as if the emotional flows of the whalers could never be regulated. Although the execution of the drum dance was not announced to the public in advance, the drumbeat immediately lured many villagers into the circle. It was a spectacular scene. The author saw the drummers and dancers metaphorically transform themselves into the whales through drumbeat and body movement. ‘Aarigaa [Feels good]! This is a whale of a time!’ was heard exclaimed in the crowd. The phrase provided conviction that the dance penetrates into another life and into the whale's domain to reinforce the connectivity between the dancers and the celebrated whales. The drumbeat kept the village awake, excited, and enlivened until dawn raised the sun that had stayed shining low over the northern horizon throughout the night.

In the same year in Point Hope, 5 successful whaling crews that had landed 7 whales participated in their own qalgis according to clan affiliation. Their nalukataq continued for 3 full days, involving all villagers and visitors in appreciating the whales through elaborated rituals and performance. The communal fulfilment was revealed in the blanket toss and eventually in the drum dance. The drum dances in both Barrow and Point Hope indicated a hope of another productive whaling season for the following year. This active whaling cycle, however, was broken rather abruptly in early 2006 with unexpected sea ice conditions.

The cultural continuity of the North Slope villages was disturbed in spring 2006 due to the impoverished whaling season (Table 1). The unsuccessful whale harvest during the 2006 spring season is distinctive within a larger historical perspective of whaling seasons because of the local recognition of explicit causal links between changing environment and accessibility to the whales. ‘It was one of the most impoverished seasons across the North Slope Borough coastal whaling communities for the past 35 years,’ recalled an elderly female whaling captain who was in her 80s (Lane Reference Lane2006). She continued: ‘[w]e have faced difficult seasons before and have had, of course, to adapt. But it had never been bad this much.’ While this single statement cannot encompass all of local history, this situation sheds light on the 3 major problems that Iñupiaq drumming tradition confronts today: anticipated struggles in acquiring drum-membrane materials, disturbances in the timing of whale related ceremonies, and more seriously, in the continuity of ceremonies themselves. However, Iñupiaq performers attempt to cope with these new challenges with their traditional cultural expressions of continuous drumming.

Table 1. Bowhead whale harvest efficiencies and its link to the drum dance in Barrow and Point Hope.

The whale drum definitely remains at the core of Iñupiaq ceremonies, and climate change inevitably impacts on the production of drums by influencing the level of whaling success. One anticipated problem is the shortage of whale stomachs and liver linings. Pete Frankson of Point Hope noted: ‘[w]hales get us dance. Whale skin is the best material for our drums’ (Frankson, P. Reference Frankson2006). Frankson fears that difficulties in obtaining the correct material would directly influence Iñupiaq cultural survival and would eventually result in changes in the drumming tradition. Although the Arctic region has repeatedly gone through climate change and ‘the death of hunting’ has been predicted several times throughout oral history, one of the enduring aspects of Inupiaq survival skills is flexibility (Bodenhorn Reference Bodenhorn2001). That said, the zero whale harvest in 2006 brought the Point Hopers no fresh supplies of whale membranes for the year. As Ernie Frankson, Sr. stated, the whale skin drums need meticulous care to maintain good condition. Dry Arctic air often makes the material fragile, and frequent repair or complete replacement of a membrane needs to be planned ahead of time. Additionally, in spite of its immense size, the portion of the whale stomach that can be used ideally for drum making is limited (Frankson, P. Reference Frankson2006). Considering the relatively large number of drums (5 to 20) required for ceremonial occasions, the decline in the whale harvest may result in a serious loss of this crucial medium.

Some Barrow drummers have explored using heavy plastic material for the drumhead, otherwise known as ‘parachute drums’, to replace animal body parts (Frankson, P. Reference Frankson2006; Johnston Reference Johnston1977). Frankson states:

I heard this from my uncle. Robert's (his distant cousin) aapa (grandfather) experimented on nylon or plastic material that Navy folks brought over to NARL (the Naval Arctic Research Laboratory) after the war. One day [at a camp], he made a drum out of it, a drum that never gets old or gets torn. This [synthetic membrane] may not sound as good as the real whale . . .. but it sure was a drum. It helps us carry out our tradition and carries the same symbolism at the time of this whaling problem. I don't think it replaces our spirituality. The drum still means the whale to us and we keep playing this at nalukataq and other festivals in celebration of the whale (Frankson, P. Reference Frankson2006).

In Barrow today, the use of plastic membranes now exceeds that of whale livers or stomach skins. However, Willie Nashookpuk, Sr. along with other Point Hope drummers resists the use of synthetic materials to replace the whale membrane: ‘[t]he sound can never be the same, and I'm worried that our kids will lose track of the real meaning of our drums if they were not made of the whales’ (Nashookpuk Reference Nashookpuk2005). The drummers in that village have completely rejected plastic drum skins and continue to use membranes of bowhead organs. Feeling the whale membrane of his drum, however, Nashookpuk commented reluctantly: ‘[d]oes this give the impression that we have lost our fight? Well, but I guess we have to deal with the change, just to survive this moment. Who knows about the future?” (Nashookpuk Reference Nashookpuk2005). This transformation may have to become inevitable among the Point Hope performers soon if traditional whaling continues to suffer.

In addition to the membrane crisis, the continuity and even existence of whale related ceremonies have also been threatened. When the spring hunt in 2006 turned into misery and brought no celebration to Point Hope, this situation severely affected the emotions of Tikigaqmiut. Sally Killugvik of Point Hope told the author: ‘[o]h I cried and cried, because there was no whale! My husband was stressed, depressed, and so was everyone else in the crew and the village, it wasn't good’ (Killugvik Reference Killugvik2006). A young mother who is a dancer in the village noted: ‘[w]e were practicing Eskimo Dance all winter, so it was a big, big disappointment [that we couldn't host nalukataq]. My five-year-old boy missed his first chance to sing, too’ (Anon 2006a). The 2006 situation was as devastating in Barrow. The people of the whales were dispirited. Anxiety, uncertainty and fatigue swallowed the entire community that was about to lose its balance.

By influencing human-whale relations, drastic environmental changes may cause social disharmony in the whaling cycle. In 2006, the drum dance to celebrate the whales did not occur in either Barrow or Point Hope, and Point Hope was unable to host any nalukataq at all. Barrow hosted only one nalukataq, in honour of the 3 whales they had managed to land. At this feast, naturally, the quantity of whale meat in distribution was small compared to the year before. Additionally, with only 3 crews hosting the feast, despite their efforts and enthusiasm, the event itself appeared less vibrant. All crews related to the successful umialiks helped out to lead the feast to success, but undoubtedly the ratio of the servers to the served was out of balance. The drum dance was originally to follow the feast and blanket toss at night, but it was called off due to a tragic suicide in the village, and was never rescheduled for a later time. In both Barrow and Point Hope, the 2006 devastation in whaling confirmed that the environment is a potent factor in determining the shape of Iñupiat musical performance and even the retention of their cultural identity (Table 1).

While it is the most significant event in the whaling cycle, nalukataq is not the only ceremonial occasion that is vulnerable to environmental change. As the oldest community of Iñupiat country, Point Hope retains a distinctive set of ceremonies and rituals that have been passed down in the village for centuries. In early autumn of a successful whaling year, the villagers traditionally enjoy qiñu, the ‘born of ice’ ceremony in appreciation of the whale's tail (akikkaq), at each qalgi. For qiñu, when a whale is caught in the spring, its tail is cut off and then brought to a place near the captain's sigluaq and covered with muktuk. The ceremony is a renewal, deeply tied to subsistence activities and held in honour of the whale's spirit. Accompanied by an overnight drum performance, the qiñu ceremony expresses gratitude to the whale and lets the whalers make a full circle into the following whaling season.

As its name and seasonality indicate, qiñu is reliant upon the environmental cycle and can only be conducted when the first slush ice touches the shore of Point Hope. As the unpredictability of the climate increases and the formation of autumn sea ice is delayed from late September to early November, many aspects of this sea ice related ceremony now need to be delayed, modified, or eliminated (Frankson, Es. 20 Reference Frankson2005; Killugvik Reference Killugvik2005). Esther Frankson, elder of the community and a female whaling captain, who inherited the title and crew after her husband's demise, shared her concern with the author: ‘[w]e are not allowed to start our preparation for the following whaling season until the completion of qiñu’ (Frankson, Es. Reference Frankson2005). More seriously, Suuyuk Lane, Sr., another elder, told me that the permafrost melting of sigluaq spoils the sacred akikkaq while it is being stored, which endangers the continuity of the ceremony itself (Lane Reference Lane2005).

Another major facet of Iñupiaq lifeways threatened by unexpected change is mutual trust among community members. The following question was posed to a Point Hope villager. ‘Why do you think Point Hope had such a hard whaling season?’ The response was as follows. ‘Um, they say some family broke taboo and gave away the secret that belonged only to the village. They broke our taboo, and the whales heard them and became angry at us altogether. They [the family] were so inconsiderate.’ In the ceremonial qalgi, unique yet strict taboos exist during the performance. For example, if anyone speaks ill of the whale or behaves inappropriately, the whale spirit would become offended and stay away from Point Hope the next whaling season; thus there would be neither feast nor music for that cycle.

In fact, some villagers largely attributed the 2006 whaling collapse to taboo breaking in the community during a ceremonial dance. Tension arose because some villagers were concerned that someone revealed the secrets of the ceremony to outsiders. In Point Hope, the author visited the family being accused of giving away the secret. ‘At this time with all sorts of worries and problems, my brothers and I thought the dance and ceremony should be documented so that our children and grandchildren can refer back to it in the future. It is our heritage as much as our whaling’ a family member said. Uncertainties about the environment and the future undoubtedly brought the community into dispute, and the villagers’ minds were dwelling on what they should or should not do to retain their cultural heritage. An unsuccessful whaling venture deprives the Iñupiat of festivities and trust. At Point Hope in 2006, it planted substantial uncertainties and mutual distrust that disrupted communal unity, breaking the continuity of the whaling cycle.

Cultural survival and drumming for the whales

The Iñupiat of Barrow, in spite of their unproductive whaling in 2006, invited Tikigaqmiut, other villagers from the district, and anyone who wished to attend to share the whales on nalukataq. Lollie Hopson of Barrow expressed her view: ‘[i]n our tradition, any difficulty unites us, makes us stronger, and have us confirm what the most important thing is . . . our whales and our togetherness as the people of the whales’ (Hopson Reference Hopson2006). Many Iñupiat recognise and anticipate the link between global warming and their changing relationship to whales. George Ahmaogak, Sr. reminded the author of this anticipated concern:

Without whaling, our society will experience severe social disorder, nutritional problems . . .. We need whaling and the associated festivals to keep our connection with the whales. If [there is] no whale, [there will be] no festivals, and [the absence of whales and festivals] will cause a severe depression in this community (Ahmaogak Reference Ahmaogak2005).

Having served as the mayor of the North Slope Borough and as a whaling captain since the late 1980s, Ahmaogak has seen many changes in the environment and his people's worldview. Ahmaogak expressed his awareness of subsistence difficulties and increasing social and cultural problems caused by changing environment:

Human-whale spirituality will be changing. If our contact with the whale is kept influenced by global warming, our spirituality will soon start eroding. Now we must think, feel, and see like a whale to retain our relation. Feeling about the whale and oneness with the animal keep us [both humans and whales] alive, and this can be continued with the re-recognition of our traditional events like drum music (Ahmaogak Reference Ahmaogak2005).

With the support of North Slope Borough elders and residents, Ahmaogak and his staff at the mayor's office resuscitated kigviq in 1988, at a time when Iñupiaq cultural identity, political issues, and environmental awareness were all coming together. ‘This festival was known to show respect to harvest, but it continued to lie dormant for generations, and the return of ancestral heirlooms assisted us in retrieving some of the ways of acknowledging the spirit of the whale.’ Ahmaogak claimed that the musical element of the festival binds the Iñupiat and the whales, and now is the time for his people to put more iñua (spirits) into their musical performance as a form of cetaceousness, as drum music is a way for the Iñupiat to feel the environment through the whale's senses.

Fannie Akpik also believes that it is time for the Iñupiat to make music to reconnect the human mind with the whale's because ‘[n]ow our community needs to be stronger than ever (Akpik Reference Akpik2005). Traditionally, the Iñupiat believe that without any whale harvest, they should refrain from conducting performances or festivities. Yet, according to Akpik, music now has a capacity to help people adapt to the changing environment:

If we need to change things to survive, then we ought to. If we have no whales, then we really do need to have more music. It would help us and our souls tune into the mind of the whales. We also say the whale is always looking for a village with good music. Drum music may become our last hope to keep our relationship with the whale (Akpik Reference Akpik2005).

This strong verve is also shared by the members of her dance group who are whalers. It seems now the Iñupiat themselves who bring music to the whales to repair the broken whaling cycle. George Kingik elaborated:

It was a taboo [to have drum dance at the time of insufficient whale harvest] because our people knew the whales would return in the following season if we remained humble and quiet. But we don't have such guarantee anymore. A taboo always ha[s] a reason or two to make our life safer . . .. This is a time of our cultural survival and, for us to survive, if you ask me, not having any music [when we have no whales] is a new taboo. I think we can play our drums more often to remind the whales that we're still here waiting for them (Kingik Reference Kingik2006).

The whaling cycle needs to turn, with or without the whales. Some Iñupiaq performers are now willing to reverse the metaphorical power relationship. Iñupiat can give music to the whales through their drumming for them. To complete the cycle, the whalers need the whales. To get the whales, they should perform and drum. In fact, the drum dance has become increasingly common outside the traditional occasions and is performed to celebrate non-traditional events such as a new school term or a spring festival. These events were not traditionally part of the whaling cycle, but all festive occasions in the villages have links to whaling. In this way, the newly developed events are likely to become part of the whaling cycle as the Iñupiat adaptation progresses. All such occasions welcome visitors, Iñupiat and non-Iñupiat alike. While the role is reversed between the Iñupiat and the whales, drum music remains an irreplaceable bond between Iñupiat and whales.

Although neither Barrow nor Point Hope was able to host the drum dance at nalukataq in 2006, Barrow was hosted the Inuit Circumpolar Conference (ICC) in July of the same year, welcoming international delegations from the 6 Arctic nations. The Iñupiaq dancers organised four nights of drum dance and sharing of accumulated whales retrieved from their sigluaqs. Performance became a way to communicate with other pan-Arctic culture groups and a way to invite the guests to the Iñupiat land. Iñupiat-whale relationships were reactivated and reconfirmed through the circumpolar gathering around the drumbeat.

With regard to climate change the view of experienced whalers is that the key is to be ready to secure any possible whales.

Oh, we'll be ready early [so as] not to miss any whales that migrate early due to warming sea water, and we'll work faster, harder to survive with the whales. We're a strong people. If the environment needs to change, we'll adapt. If the whales need to change, we'll keep up. That's the way how our ancestors always had been. We will survive . . . see, we can still beat the drums for the whales! Drumming gives us confidence. Power. We have to transport our old custom into new times, and it will go through changes on our tradition and will make our best efforts to keep it going. We may need more time to adapt, but there are more people now [who] participate in dance and drumming for our whales. We are thinking of the whales more than ever. Our necessity and desire to be with the whales will always be here in our blood and land. We dance, sing, and drum for the whales. We are 7,000 [Iñupiat population] strong here, over 7,000. (Anon 2006b)

Conclusion

This article describes how Iñupiaq drumming and its continuity demonstrate an active adaptation process to deal with environmental changes and stresses. Drum performance and its resurgence in community events mark the growth of their cultural identity. In order to survive, some Iñupiat newly endowed their performance with the strength to bring the whales back to them. In this way, the drumming that was originally brought to the Iñupiat by the bowhead whales is returned to the whales through collaborative reciprocity. Inevitably, the future holds further changes and challenges. Yet the Iñupiaq drumming for the whales continues to be an active agent in this process. The voices of the people demonstrate how performance plays a significant role in expressing and reconfirming their ties with the whales and with their land. The broad yet worsening future uncertainties gradually take shape as specific environmental degradations. Iñupiat whalers now work on their own adaptation to survive such challenges via musicality to reconstruct their disrupted whaling cycle. To the Iñupiat, the drumbeat is the heartbeat of the people of the whales, and the instrument now has power to reestablish the communication between the Iñupiat and the whales.

Acknowledgements

The author extends her gratitude to the financial and logistical assistance provided by the following institutions: the United States National Science Foundation (NSF) Office of Polar Programs, the NSF Arctic Social Sciences Program and Geography and Regional Science Program (NSF Grant No. 0526168); Barrow Arctic Science Consortium (BASC); the North Slope Borough Department of Wildlife Management; the Center for Ethnomusicology at Columbia University; the Earth Institute at Columbia University; the Department of Geography and the Native American Studies Program both at the University of Oklahoma. As a doctoral candidate in geography I was fortunate to have been guided by Bob Rundstrom, my former advisor. In preparing this manuscript I have benefited from encouragement from Aaron A. Fox of Columbia University. Thanks are also due to Karl Offen for his personal and intellectual empowerment. Barbara Bodenhorn's work in Barrow has been my inspiration. Last but not least, my deepest gratitude goes to the people of Point Hope and Barrow, Alaska, for their continuous encouragement and friendship throughout my fieldwork Quyanaqpak. They are my teachers and are real people. Their valuable help and willingness to share the depth and breadth of their knowledge and experiences made my research possible, rewarding, and productive. Transcriptions of the interviews undertaken during this work will be deposited at the Iñupiat Heritage and Language Commission archive at the Iñupiat Heritage Center in Barrow.