With the assassination of President Habyarimana, Rwanda entered one of the darkest episodes in human history. Within the time span of just a few months, Hutu militias meticulously rounded up and massacred over half a million Tutsi civilians. While Tutsi life was violently discarded, Hutu life was cheap; “reformist” Hutu elites were assassinated or forced into hiding, while local Hutu officials who did not support the violence were killed. Within only two weeks, the genocide had spread to all regions under the control of the genocidal Hutu government, which had assumed complete political control over the Hutu populationFootnote 1—despite ultimately losing to Tutsi rebels after three and a half months of fighting.

Rwanda is not the only instance where mass violence against outgroup civilians coincided with purges of ingroup elites. In the communist regimes of the Soviet Union, China, and Cambodia, the motive for the violence seems completely different from Rwanda's. Yet the violent collectivization and mass killings of outgroup enemies nonetheless co-occurred with purges of the highest-ranking communist elites.Footnote 2 This is peculiar—not only are ingroup elite targets of purges unrelated to outgroup civilian targets of mass indiscriminate violence but purges and indiscriminate violence are also independently risky and generate resistance from different parts of the population. Purges invite coups from elites, while indiscriminate violence generates armed resistance from targeted outgroups and may also invite foreign intervention or sanctions.Footnote 3 It's not clear why leaders would take on independent risks at the same time: why not consolidate power first, before embarking on mass violence? Problematizing the empirical co-occurrence of purges and mass indiscriminate violence should help us to uncover their dynamics.

Building on recent insights on authoritarianism, I argue that a key type of mass indiscriminate violence is actually a rational reaction to elite rivalry; authoritarian leaders experiencing intra-regime rivalry may adopt mass indiscriminate violence to sideline rivals and consolidate power. Unable to target rival elites directly, leaders can couple mass indiscriminate violence against an outgroup with selective violence toward an ingroup to capture local government and security structures. This in turn bolsters a leader's support coalition and captures or neutralizes the support base of elite challengers who can subsequently be purged from the government. I refer to this process of mass indiscriminate violence as genocidal consolidation.Footnote 4

The contribution of this study is threefold. First, it provides a single parsimonious explanation for mass killings and genocides that to date have been explained by attributing leaders with strong ideological preferences for violenceFootnote 5 or as unique cases only.Footnote 6 Even after 1945, genocidal consolidation alone accounts for between eight and eleven million (mostly civilian) deaths, in contrast to less than four million battle deaths in interstate war.Footnote 7 Yet, political science research into mass indiscriminate violence trails behind research into (civil) war. While we have a good understanding of mass indiscriminate violence within the context of irregular counter-guerrilla operations,Footnote 8 extant scholarship treats all other mass indiscriminate violence as motivated by leader ideology.Footnote 9 As an explanation, however, leader ideology is likely incomplete and cannot explain why mass indiscriminate violence occurs during elite rivalry: why not consolidate power first, before embarking on risky ideological ventures? I introduce a novel explanation based on leader incentives for self-preservation that accounts for this anomaly.

Second, this study leverages newly collected data, both on mass indiscriminate violence and on elite purges, to demonstrate one of the processes through which violence produces private benefits for leaders. This positions the study of mass indiscriminate violence within a wider conflict literature that rests on the assumption that violent conflict is destructive and inefficient. Within this literature, the occurrence of violence is therefore explained in terms of bargaining failure.Footnote 10 This study, however, proposes a radically different cause of bargaining failure: the violence itself is a consumption good. When between-group conflict (e.g., Hutu vs. Tutsi) generates within-group—for example, Hutu vs. Hutu—security benefits that outweigh the costs of conflict, violence is no longer ex post inefficient.Footnote 11 This explains instances in which authoritarian leaders may seem to use violence irrationally: they are actually seeking internal self-preservation. In these cases, conflict resolution attempts to resolve bargaining failures are likely to fail.

Third, this study provides new insights into little-known processes of authoritarian consolidation. Researchers have identified a variety of coup-proofing strategies that leaders may use to reduce coup risks.Footnote 12 However, these strategies to manage elites are typically not viable when the leader is at power parity with strong rivals because these rivals may counteract with a coup. By focusing on elite support coalitions, this paper contributes to the growing research into the violent coalition-building and disempowerment tactics that authoritarian leaders adopt to manage rivalry.

Existing Explanations of Mass Indiscriminate Violence

Mass indiscriminate violence—also referred to as mass killing, democide, or (high intensity) geno-politicideFootnote 13—is rare but nonetheless responsible for two to five times as many deaths as the battle deaths of inter- and intra-state conflict combined.Footnote 14 It is a type of mass political violence with four defining characteristics: (1) it intentionally targets a massive number of noncombatants;Footnote 15 (2) it targets an outgroup—an ethnicity, religion, or class that is not part of the governing coalition; (3) it is indiscriminate—it targets outgroup victims irrespective of their behavior; and (4) it is not aimed at political control of this outgroup.Footnote 16 The staggering scale and indiscriminate nature of the violence have sparked broad scholarly interest that has provided various explanations for its occurrence. Under specific conditions of guerrilla conflict, mass indiscriminate violence has been shown to be effective in starving a guerrilla of its support. These “drain the seas” massacres commonly occur in protracted irregular guerrilla wars.Footnote 17 Consequently, counter-guerrilla mass indiscriminate violence is concentrated within territories where a guerrilla is dominant. However, in roughly 40 percent of mass violence episodes (e.g., Rwanda and Cambodia), the violence was aimed at populations within areas of secure territorial control. In this paper I focus on those instances of mass indiscriminate violence in areas that lack any real guerrilla presence.

Outside of irregular guerrilla conflict, surprisingly few theoretical explanations of mass indiscriminate violence account for strategic actors’ material interests. While there exist excellent case studies of mass indiscriminate violence,Footnote 18 these cannot provide a single parsimonious explanation for its occurrence. Large-N comparative studies, on the other hand, have focused on prediction over theoretical explanations.Footnote 19 Although it has been well established that governments initiate mass indiscriminate violence,Footnote 20 violence is commonly examined with the implicit assumption that governmental actors lack agency and are carried away by larger societal forces of ethnic hatred and primordial cleavages.Footnote 21 Explanations that do address why governments initiate mass indiscriminate violence fall into the broad categories of (a) leader ideology; and (b) between-group conflict.

By introducing leader behavior, Valentino offers a seminal political science explanation for the occurrence of mass indiscriminate violence.Footnote 22 He provides a typology that contains a wealth of information with respect to mass indiscriminate violence, as well as a convincing strategic explanation for the occurrence of mass indiscriminate counter-guerrilla violence. However, with respect to all other instances of mass indiscriminate violence, Valentino argues that leaders have an ideological preference for the extermination of groups that they perceive as a threat to their—communist or ethnic supremacist—vision of society. Recent studies show that ideology is undeniably part of the process of mass violence.Footnote 23 Ideology may shape elites’ threat perception and understanding of a conflict, as well as determine the range of options available;Footnote 24 or help mobilize supporters while providing a rationalization for and targets of the violence.Footnote 25 However, while mass violence and extremist ideology correspond, the ideology explanation leaves room for rival or complementary theories that take leaders’ material interests into account, since ideology (a) can motivate a wide range of behaviors; and (b) doesn't explain temporal variation of the violence.

First, ideology can motivate a wide range of behaviors. Explanations that rely on the radicalism of the ideology, for example, carry an implicit reference to the violence that we seek to explain: are communist and supremacist leaders who do not engage in mass violence actually less radical or do scholars attribute less radical ideologies because they kill fewer people? Straus addresses this issue by demonstrating that different pre-existing “founding” narratives result in different responses to similarly violent challenges.Footnote 26 Still, even if we accept that ideology shapes elites’ evaluation and behavior,Footnote 27 elites can take a wide range of ideological positions and corresponding policies within the bandwidth of a single ideological background. Therefore, the deadly ideological extremism and the corresponding policy may follow pre-existing material interests. For example, Pol Pot's choice to single out the rival Northwest region for rice extraction and corresponding starvationFootnote 28 is but one of many positions he could have taken within the framework of his radical communist ideology. It is likely not a coincidence that his deadly policies closely aligned with his material goals. Leader ideology, therefore, leaves room for a complementary or rival explanation based on leaders’ material interests.

Second, ideology doesn't explain temporal variation.Footnote 29 Both in Cambodia and Rwanda, for example, mass indiscriminate violence occurred in an environment of high insecurity and rivalry at the top of the regime.Footnote 30 By itself, mass indiscriminate violence against civilians comes at high risk to a leader because indiscriminate targeting on the basis of—ethnic, religious, or class—identity generates increased resistance. While all authoritarian regimes adopt repression, most repressive violence is selective; it targets people based on their behavior. Selective violence demonstrates to potential opponents that resistance is costly. It is therefore instrumental to political control of an area, a population, or government.

Indiscriminate violence, on the other hand, targets people on the basis of identity—regardless of behavior. It therefore demonstrates to potential victims that cooperation is futile and helps coordinate resistance and generates opposition.Footnote 31 Moreover, mass indiscriminate violence can undermine the armed forces’ ability to respond forcefully to external threats,Footnote 32 while the resulting humanitarian and refugee crisis may invite foreign intervention, as was the case in Cambodia and Kosovo.Footnote 33 Consequently, the domestic and international opposition generated by mass indiscriminate violence makes it an especially risky strategy for authoritarian leaders who seek survival.

Purges of regime elites also come at high risk to a leader because authoritarian leaders rely on elite support for survival. It is apparent that rivals can pose high risks to a leader's survival.Footnote 34 Nonetheless, authoritarian leaders must take great care before they move against ingroup rivals, since the targets of the purge may counteract with a coup themselves.Footnote 35 Authoritarian leaders care about political and physical survival.Footnote 36 It is therefore unclear why these leaders would take on the outgroup and elite ingroup rivals at the same time. Why would these leaders risk life and liberty to achieve their ideological vision of society when they are least secure? Why not consolidate power first? By itself, radical ideology does not suggest a specific timing or efficiency of the violence. However, if leaders care about their own physical survival besides ideology, we should expect authoritarian leaders to be more likely to execute their pet project when they are most, not least secure.Footnote 37 Conversely, these leaders might be ideological zealots with a personal and irrational preference for violence without regard for their security.Footnote 38 However, if these leaders are ideological zealots, we should observe violence occurring regardless of elite rivalry and observe a higher rate of violent removal for these irrational leaders.

The second explanation posits mass indiscriminate violence as a strategy of removing an outgroup threat. Several scholars have observed that mass indiscriminate violence is more likely to occur following civil war.Footnote 39 Licklider, for example, argues that mass indiscriminate violence results from a one-sided victory in civil war.Footnote 40 Similarly, Straus argues that the Hutu leadership instigated mass violence as a desperate measure to win an impending civil war.Footnote 41 In both instances, scholars argue that mass indiscriminate violence is aimed at the civilian support base of outgroup rebels that may pose a future threat. However, these arguments do not address the occurrence of indiscriminate violence in areas of secure territorial control where selective violence is both feasible and effective.Footnote 42

Furthermore, these arguments do not address the actual mechanisms through which mass indiscriminate violence against civilians would be an effective strategy to deal with an outgroup threat. These studies implicitly adopt a counter-guerrilla mechanism to explain violence that occurs far from areas with any actual guerrilla activity. They hinge on the assumption that outgroup militants can more effectively rely on co-ethnics for supportFootnote 43 and that mass indiscriminate violence undermines outgroup militants’ ability to pose a future threat. In other words, governments seek to starve these militants from a potential civilian support base. However, while guerrilla forces do rely on civilians for food, supplies, and recruitment,Footnote 44 they do not actually require the support of a co-ethnic population. Guerrilla forces commonly coerce and prey on civilians to survive.Footnote 45 Through the use of selective violence, militants can coerce a civilian population into support in areas they are dominant inFootnote 46 even if they do not share ethnicity. This explains why in Guatemala, for example, much of the government violence was aimed at Indigenous towns that did not share ethnicity with the rebels and were coerced by rebel forces.Footnote 47 Consequently, the mechanisms from counterguerilla mass violence cannot simply be exported to a noncounterguerilla environment.

In many instances of mass indiscriminate violence, such as during Mao's Great Leap Forward or Cultural Revolution, an outgroup guerrilla was completely absent. In other instances, the argument for an outgroup threat does not hold up to scrutiny. In Cambodia, for example, the Lon Nol regime had been thoroughly defeated and cannot explain four years of mass indiscriminate violence against various outgroups.Footnote 48 More importantly, none of the explanations that posit mass indiscriminate violence as a strategy to remove an outgroup threat would lead us to expect the violence to be related to heightened ingroup competition or purges of ingroup elites.Footnote 49

I demonstrate that mass indiscriminate violence corresponds to elite competition in roughly 40 percent of cases in which the violence is not part of a counterguerilla strategy. Therefore, I argue that in these cases, not outgroup threat, but elite ingroup rivalry drives leaders to initiate mass indiscriminate violence. Let us now turn to the mechanisms that connect authoritarian competition to mass indiscriminate violence.

A Theory of Genocidal Consolidation

At the top of authoritarian regimes, the constitutional checks and balances that protect elites from competitors’ violence in liberal democracies are mostly weak or absent. As a result, elites at the top of authoritarian regimes find their power checked by rival elites and have a high risk of losing life or liberty upon losing office.Footnote 50

To survive in this insecure environment, elites rely on their own support coalition, as well as on alliances with other elites. Elite support coalitions are built on formal and informal relationships with clients in various state institutions, such as the military and bureaucracy.Footnote 51 However, the importance of maintaining these support coalitions also creates a security dilemma: elites will rationally seek to strengthen their support coalitions versus their potential competitors. This fuels competition, strains relations, and generates volatility at the top of the regime, which effectively decreases security for all. High volatility and insecurity lock rival elites in a deadly commitment problem—even when they prefer cooperation over deadly competition—because either would be most secure without the other. Therefore, neither can commit that they will not remove their rival in a coup or purge at the first opportunity. Coups and purges are especially deadly: they are secret, sudden, of close proximity, and—unlike rebellions—seldom allow for a fighting retreat. Consequently, to leaders who seek political and physical survival, the threat of elite or intra-group competition is much more acute than that of any rebellion originating from outside the regime.Footnote 52

Recent studies provide some insight into strategies that leaders adopt to deal with elite rivalry: they may tie up the military in the execution of a war;Footnote 53 take information shortcuts by homogenizing—for example, ethnically—their inner circle;Footnote 54 or slowly creep into power to the point where coups become too costly.Footnote 55 However, though ethnic homogenization may alleviate the commitment problem, it is unclear how it would solve it since co-ethnics could displace a leader as well. Coup proofing—reshuffling government, appointing co-ethnics, and purging coalition allies—initially exacerbates the security dilemma, increasing coup threat.Footnote 56 Although coup proofing becomes a viable strategy once the leader has reached a threshold of power, it is unclear how leaders reach that threshold when rivals are strong and the need for security is highest. How do authoritarian leaders deal with this dilemma?

Political Consolidation Through Mass Violence

I argue that authoritarian leadersFootnote 57 faced with elite rivalry might adopt mass indiscriminate violence to strengthen their support coalitions and weaken those of rivals to ensure survival. First, the violence helps build coalitions with various constituencies that gain from violence against outgroups. It thereby builds a formidable repressive apparatus that can also be turned on ingroup rivals. Second, the violence indirectly targets the support coalitions of rival elites by undermining the formal monopoly of violence and forcing local security officials to facilitate or oppose the violence. It thereby provides rivals’ supporters with an exit option, provides information on rivals’ supporters’ private loyalties, and undermines rivals’ abilities to mount an effective resistance.

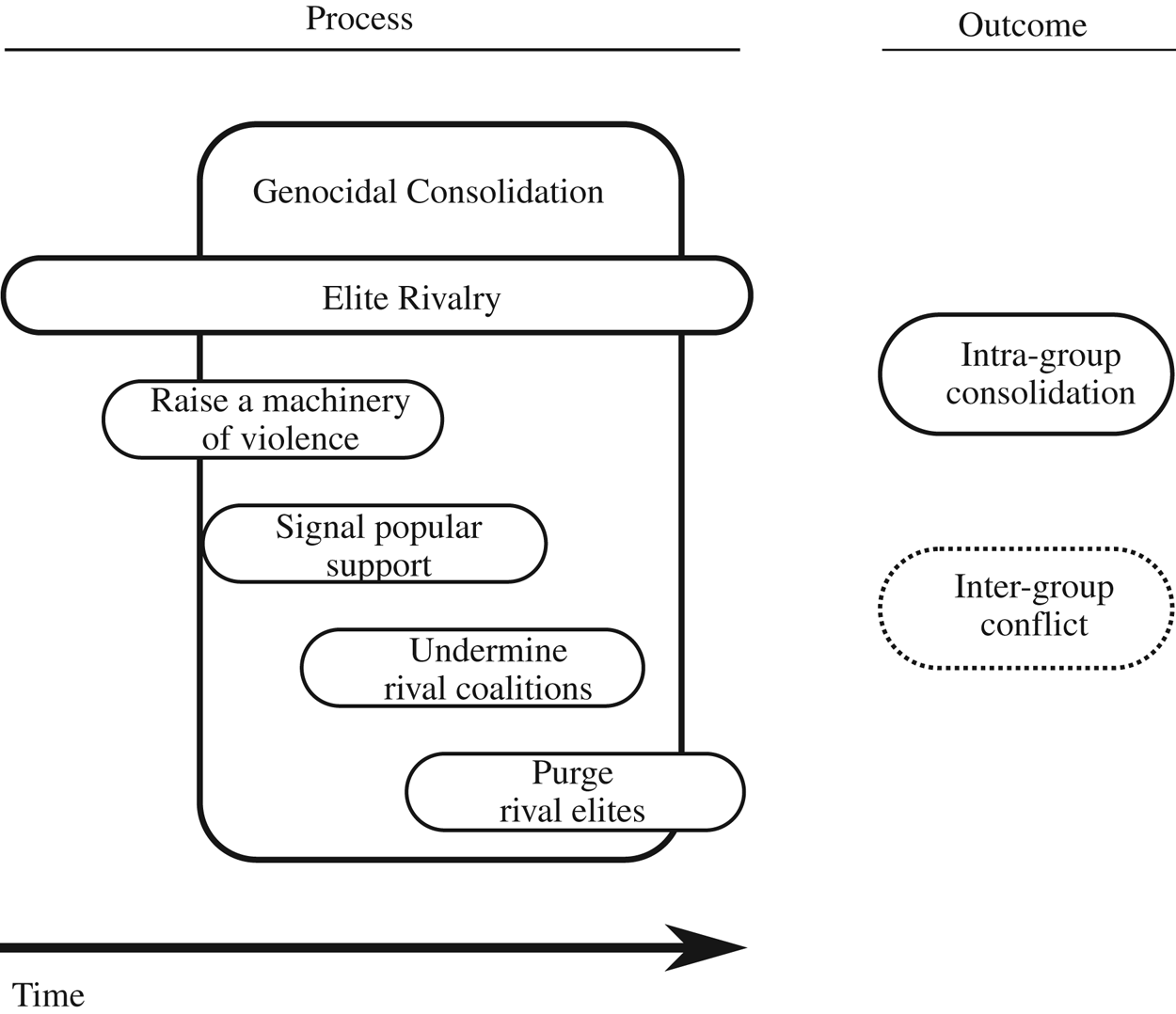

Because this type of mass indiscriminate violence is part of a process of consolidation, I refer to this process as genocidal consolidation, which has five partly overlapping stages. The first stage is elite rivalry, which is established as the main condition under which genocidal consolidation occurs. The second stage is raising (i.e., expanding, creating, or capturing) a machinery of violence that is free from control of rival elites in the form of irregular, militia, or paramilitary clients. The third stage involves signaling popular support for the genocidal faction and for its violence. The fourth stage is that of undermining of rival support coalitions. And the final stage involves purges of rival elites following weakening of rival support coalitions. To provide a road map of the theory, Figure 1 presents a causal diagram of the full process of genocidal consolidation.

Figure 1. Theory of genocidal consolidation

Elite Rivalry

Elite rivalry is among the most salient threats to authoritarian elites. Its pressures are so intimately connected to the physical survival of elites that otherwise unimaginable policies, like the mass killing of innocents, can become feasible. There are many reasons that authoritarian coalitions may disintegrate. In Cambodia, for example, factionalization within the Khmer Rouge turned salient and violent following victory in war.Footnote 58 Other times the leader is confronted with a (postrevolutionary) drive for openness and democracy supported by the military or other elites within his own regime, as was the case for Milošević in Serbia and for reactionary “extremists” in Rwanda.Footnote 59

Raising a Machinery of Violence

Faced with the threats of elite rivalry, leaders may adopt mass violence to strengthen their support coalitions. It is obvious that mass indiscriminate violence requires a machinery to execute the violence. It is less obvious that mass indiscriminate violence can also expand or capture a machinery of violence that is free from rival elites’ control. When state power is deeply divided, elites may seek to build coalitions with groups outside state institutions, such as militias and paramilitary groups. In Rwanda and Yugoslavia, for example, hooligans were secretly armed by the government to create militias;Footnote 60 in China Mao raised the Red Guards as part of the cultural revolution;Footnote 61 and in Cambodia, Pol Pot raised an irregular group of model adolescent peasants from the Southwestern zone to export the revolution to other areas.Footnote 62

Militias, paramilitary, or other irregular forces—hereafter militias—are notably hard to control because their members face both costs and benefits of violence; militias may be overly violent in pursuit of material and nonmaterial gainsFootnote 63 or reluctant to perpetrate violence in fear of revenge or prosecution.Footnote 64 We should therefore expect variation in how militias evaluate costs and benefits of indiscriminate violence, which should also be related to the manner of mobilization.Footnote 65 Mass indiscriminate violence is often executed by quickly raised and poorly controlled predatory militias that consist of young, poor, and low-status individuals who join for quick economic and status gains.Footnote 66 While these militias are hard to control directly, they can be steered to use violence against outgroups.

The leader can therefore rely on predatory militias containing poor, unemployed, or low-status individuals who have most to gain from the redistributive nature of violence. By facilitating violence, the leader provides armed thugs with the wealth, power, and status that violence provides. By advancing ideology, the leader provides armed thugs with a moral incentive as well as clear outgroup targets for their violence. Mass indiscriminate violence can, therefore, be a means of paying these groups, provide legitimacy, create mutual goals, and build a patron-client relationship.Footnote 67 In Rwanda, for example, the Interahamwe militias recruited among the poor. Once the violence started, the poorest at the bottom rung of society—such as the homeless unemployed—joined the militias to gain from the violence.Footnote 68 These armed thugs—even when banded together in paramilitary groups—are no match for professional forces and are unlikely to directly engage armed support coalitions of rival elites.Footnote 69 They are, however, cheap, easily steered toward outgroups, and highly effective at terrorizing civilians.Footnote 70

Signaling Popular Support

Armed thugs can unleash sudden and overwhelming indiscriminate violence on outgroup civilians—based on ethnic, religious, or class background—and plunge the country into chaos. The majority of ingroup civilians has close relations with members of the outgroup,Footnote 71 but will be powerless to intervene for four reasons: first, the violence against the outgroup is demonstrative—ingroup civilians observe their fate if they are branded a traitor; second, any remaining attempts at protecting the outgroup are met with extreme selective violence; third, they may become potential targets for retributions from outgroup militants; and last, as the saying goes, all that is needed for evil to triumph is for good people to do nothing. The leader does not require active support but merely requires inaction. When action is costly and inaction signals support for the violence, the leader can seemingly have broad support from those who seek to keep their heads on by keeping them down.

Rwanda demonstrates how civilians can be singled out and coerced into participating in public acts of violence. Killings were mostly executed by day and widely announced before and after the event.Footnote 72 While the Interahamwe militias carried out most of the violence, the group of perpetrators was broader: Hutu with familial ties to militia members or Hutu encountered en route to Tutsi homes were ordered to join the mob and provide auxiliary support. Any Hutu who dared to save Tutsi were forced to kill those Tutsi themselves or be killed as a traitor.Footnote 73 While Hutu civilians were able to help Tutsis by night, when they were alone, or in small groups, it was impossible to stop the killing as part of larger mobs.Footnote 74 Under the condition of mass mobilization, ordinary people who would otherwise be unwilling to take part in the violence and support the leader appear to be “willing executioners.”Footnote 75 This is a key feature of the violence as it signals broad societal support for the genocidal regime—even when a majority is privately opposed to the violence.

Undermine Rival Support Coalitions

Like the rest of society, local and regional security officials in the government, police, or military are pressured into non-intervention and support of the violence. Rapidly changing facts on the ground, coupled with signals of broad ingroup support for the violence, hamper local officials’ ability to respond forcefully—especially when they have extremists in their ranks. Although some officials resist, most are unwilling to risk their lives amid the insecurity that the violence generates. Local officials are acutely aware that resistance to the violence makes them a prime target. These pressures force local officials to realign in support of the genocidal faction and allow the replacement of local officials with the leader's clients.

To maintain their supporters in an insecure environment, both leader and rival need to signal strength and control. Three related mechanisms enable genocidal consolidation to more effectively neutralize or weaken rival factions than conventional coups and purges can. First, genocidal consolidation targets the outgroup and does not target the rival faction directly. Where a direct assault on the rival faction would solve collective action problems and unify resistance, genocidal consolidation allows rival supporters to switch sides or remain neutral as a low-risk option. Second, the violence provides information about the (private) loyalties of local officials. Those who resist the violence signal opposition to the genocidal faction, whereas those facilitating the violence signal support. This information allows for targeted selective violence against local officials who oppose the genocidal faction. Last, while rival elites need their local support base to unite and actively oppose the genocidal faction and the violence, parts of their local support base will opt for passive acquiescence instead. This ensures that rivals can no longer mount an effective resistance and allows for the genocidal faction to take control. In both Cambodia and Rwanda, for example, key local officials who had previously been aligned with the rival faction opted to support or, at least, not to oppose the violence.

In Rwanda, for example, the strongest resistance to the genocide was observed in regions where the rival reformist faction was dominant. Here, local security officials successfully mobilized their populations in opposition to the genocide.Footnote 76 However, as the genocide spread across communes throughout the country, reactionary “extremists” consolidated in neighboring communes. This freed up the militias that had been mobilized in other regions, which then began to make incursions into the reformist-controlled holdout communes. Under conditions of increasing external pressure, local and regional security officials were increasingly likely to step down or fall in line as the genocide spread. Those few who didn't were mostly killed or forced to flee.Footnote 77 In only two weeks, the genocide spread from sectors and communes under reactionary control to incorporate the entire Hutu state, breaking any Hutu opposition in its wake.

Purges of Rival Elites

During the final stages of genocidal consolidation, selective violence can be fully turned toward those rival elites at the top of the regime. Rival elites who have lost their support coalitions are vulnerable and can be violently purged as traitors or collaborators. In Rwanda, for example, the top of the military leadership was forced into hiding.Footnote 78 Similarly in Cambodia, over half of the highest-ranking members of the communist Khmer regime had been purged by 1979.Footnote 79 Still, genocidal consolidation is not without its costs. It helps coordinate resistance from the outgroup, it may invite foreign intervention, and the reliance on militias may undermine state structures such as the military.Footnote 80 The leader will be more secure, however, having resolved the greater internal threat at the cost of a lesser external threat.

Scope and Testable Implications

The theory of genocidal consolidation relies on three core mechanisms that determine the scope of the argument: (1) elites who lose power as a result of elite rivalry are at high risk of physical harm (e.g., death, imprisonment); (2) mass violence can potentially resolve elite rivalry because it facilitates authoritarian coalition building; and (3) mass violence can potentially resolve elite rivalry because it divides and undermines support coalitions of rival elites. First, since none of these mechanisms would operate in a democratic environment with working checks and balances, the primary theoretical scope of the argument relates to authoritarian regimes—or at least nondemocratic regimes.Footnote 81

Second, for mass violence to divide support coalitions of rival elites, the violence should include those areas where rival elites have their support coalitions, which mostly excludes counterguerilla mass violence in peripheral areas of rebel activity. However, because the geographical co-occurrence of elite support coalitions and violence cannot be observed outside the occurrence of violence, it cannot inform the empirical scope of the study. It therefore provides us with key observable implications instead.Footnote 82

The theory also leads to several observable expectations.Footnote 83 First, we should expect nondemocratic leaders to be more likely to adopt mass indiscriminate violence under conditions of high elite rivalry when their tenure is threatened. The arrow H1 in Figure 2 visually illustrates how this expectation is related to the theory of genocidal consolidation. However, if there are no security benefits to mass indiscriminate violence and it is driven by leader ideology alone, we should expect rational leaders to be more likely to instigate violence when they are most, not least secure.

H1: High elite rivalry corresponds to the onset of genocidal consolidation.

Figure 2. Hypotheses related to genocidal consolidation

Here we should also distinguish between counterguerilla mass violence and genocidal consolidation because there is no reason to assume that an increased risk to tenure would correspond to the onset of counterguerilla mass violence.

Second, we should expect leaders to adopt mass violence to eliminate elite rivals. Consequently, the theory leads us to expect that genocidal consolidation should correspond to elite purges, which also represent the leader's increased consolidation. This is illustrated by arrow H2 in Figure 2. Alternative explanations that posit mass indiscriminate violence to be aimed at an outgroup support base would not expect elite purges during spells of mass indiscriminate violence.

H2: Genocidal consolidation increases the likelihood of elite purges.

Again, we do not expect an increased propensity for elite purges during counterguerilla mass violence because it is expected to be unrelated to elite rivalry.

Third, we should expect genocidal consolidation to be a rational strategy that increases the likelihood of a leader's survival. Still, genocidal consolidation is a form of indiscriminate violence and is therefore expected to generate coordinated resistance from its targets. As such, genocidal consolidation should result in a greater propensity to win intra-regime or within-group conflicts, but only at the cost of a reduced propensity to win between-group conflicts. It is also likely that those leaders who are already at great risk (as a result of competition from rival elites) are also the most likely to initiate genocidal consolidation. Genocidal consolidation is a risky strategy that we expect leaders to pursue only because of a greater risk from rival elites. Because leaders at high risk of losing tenure are also most likely to turn to genocidal consolidation, the proposition that genocidal consolidation is instrumental to survival is not readily observable.

Therefore, we should account for these selection effects and expect leaders who adopt genocidal consolidation to have a lower probability to suffer irregular removals originating from within the regime and suffer less adverse fates (i.e., death, imprisonment, or exile) than similar leaders who do not. Specifically, the reduction in the more acute risk of internal removal should translate into a lower probability of death and imprisonment fates in particular. Because of the inherent risks of mass indiscriminate violence, leaders may also have a higher risk of removal from external sources, such as rebellion and foreign intervention. These risks of external removal might translate into a higher probability of exile, but not necessarily death or imprisonment since external removals are more likely to allow for a fighting retreat. Arrow H3 in Figure 2 illustrates that the reduced probability of adverse leader fates is a signal of intra-group consolidation. Alternative explanations that rely on irrationally violent or ideology-driven leaders who initiate mass indiscriminate violence without regard for their security would predict a higher likelihood of adverse fates.

H3: Leaders who initiate genocidal consolidation are less likely to experience adverse fates originating from within the regime than similar leaders who do not.

Empirics

I aim to establish whether genocidal consolidation (noncounterguerilla mass violence) differs from counterguerilla mass violence; whether genocidal consolidation is connected to elite rivalry and purges; and whether it is instrumental to authoritarian survival. To examine the relationship between genocidal consolidation and elite rivalry, this study leverages newly collected original data, both on mass indiscriminate violence and on elite purges in nondemocratic countries from 1950 until 2004. The empirical strategy consists of three distinct analyses—“genocidal consolidation onset,” “elite purges,” and “leader fates”—that each connect to the expected relationships outlined earlier.

Analyses, Data, and Selection

The genocidal consolidation onset analysis seeks to establish whether elite rivalry corresponds to the subsequent onset of mass indiscriminate violence. Here, the unit of analysis is country-year, the main independent variable is elite rivalry, and the dependent variable is counterguerrilla mass violence or genocidal consolidation (i.e., noncounterguerilla mass violence). The data relevant to this analysis, while broad, account for the “possibility principle”Footnote 84 by pruning irrelevant observations—that is, developed, small, and/or democratic states—from the analysis.Footnote 85

The elite purges analysis seeks to establish whether mass indiscriminate violence years correspond to purges of regime elites. Here, the unit of analysis is country-year, the independent variable is genocidal consolidation (i.e., noncounterguerilla mass violence) or counterguerrilla mass violence, and the dependent variable is elite purges. To observe elite purges, I rely on the collection of original data on purges of potential challengers within the regime. To aid data collection, this study adopted two mutually reinforcing data-selection strategies. First, I collected country-year data on elite purges by country study of the period between 1950 and 2004. The country studies included all twenty countries that experienced mass violence as well as nine countries that did not but that contained the nineteen highest-risk leaders who were most likely to initiate noncounterguerilla mass violence but did not.Footnote 86 This resulted in 1,042 country-year observations, which have considerable variation on key dependent and independent variables and are comparable on control variables. By selecting by country, I am selecting cases that are comparable to mass violence cases and similar on unobservables. The advantage of the first selection strategy is clear internal validity in a general sample of relevant authoritarian regimes. Effectively I am comparing elite purges at times of mass violence to elite purges at other—less violent—times in countries that could potentially experience mass violence. Second, I collected additional observations that were estimated to be at risk of genocidal consolidation. This sample allows for a comparison between at-risk observations with and without mass violence, alleviates selection concerns, and demonstrates external validity.Footnote 87

Finally, the leader fates analysis seeks to establish whether the initiation of mass indiscriminate violence corresponds to irregular removals and adverse fates of leaders. Here, the unit of analysis is the leader, the independent variable or treatment is the initiation of genocidal consolidation, and the dependent variables are adverse fates (i.e., death, imprisonment, or exile) and irregular removal within five years. Both the treatment and control units were drawn from the pool of nondemocratic regimes and only a single observation with the highest predicted probability of genocidal consolidation was selected for each leader.Footnote 88

If the theory is correct, we would expect these analyses to show: (1) that elite rivalry corresponds to a greater likelihood of genocidal consolidation; (2) that genocidal consolidation corresponds to a greater probability of elite purges; and (3) that leaders who initiate genocidal consolidation have a significantly reduced probability of adverse leader fates such as death and imprisonment as well as of irregular removal through internal sources. Descriptives of these key variables appear in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptives

Note: †Observations in matched leader sample.

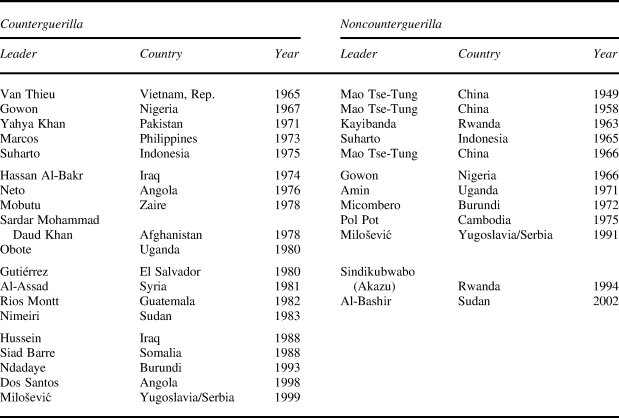

Two Types of Mass Indiscriminate Violence

The theory of genocidal consolidation expects the mechanisms that underlie counterguerilla and noncounterguerilla mass indiscriminate violence to predictably differ. The mechanisms of counterguerilla mass violence are well explained. Moreover, counterguerilla mass violence predominantly occurs in the periphery where outgroup guerrillas are dominant. These are unlikely to be areas in which rival ingroup elites have their support coalitions. Counterguerilla mass violence is therefore expected to be outside the scope of the genocidal consolidation argument. Therefore, I constructed a new data set that distinguishes between all instances of counterguerilla and noncounterguerilla mass indiscriminate violence after the Second World War. The exhaustive list of leaders who initiated the different types of mass indiscriminate violence appears in Table 2. These mass indiscriminate violence spells build on existing mass violence data.Footnote 89 Because the theory provides an explanation of mass violence, I follow Valentino and adopt a casualty threshold of 10,000 annual deaths to be considered mass indiscriminate violence.Footnote 90 The first advantage of a focus on mass violence is that it ensures that the phenomena under examination are similar. For example, the academically problematic legal definition of genocide can include massacres of small groups or tribes that are incomparable to the mass violence in Guatemala, Cambodia, or Rwanda. The second advantage of a focus on mass violence is that it aids in distinguishing between indiscriminate and selective violence at the aggregate level. While it might be possible to selectively kill thousands of civilians, mass violence that runs in the ten thousands of civilian casualties is predominantly indiscriminate.

Table 2. Mass indiscriminate violence leaders

Note: This list is exhaustive and therefore includes all leaders who initiated mass indiscriminate violence, killing 10,000 or more civilians per year, since 1945.

To establish the type of mass indiscriminate violence (i.e., counterguerilla or genocidal consolidation),Footnote 91 the data build on Lyall and Wilson's listing of guerrilla conflicts.Footnote 92 To code counterguerrilla mass violence, I first determined whether the country had a guerrilla presence according to Lyall and Wilson. If a guerrilla was present and mass indiscriminate violence was restricted to areas of rebel activity, the violence was coded as counterguerrilla mass violence. If a guerrilla was present and mass indiscriminate violence occurred in areas far from rebel activity, the violence was coded as noncounterguerilla.Footnote 93 If Lyall and Wilson did not have a guerrilla presence, the violence was also coded as noncounterguerilla.Footnote 94 In the analyses that follow, genocidal consolidation is operationalized as noncounterguerilla mass violence. It is important to note, however, that these noncounterguerilla mass violence spells are merely unexplained instances of mass indiscriminate violence. Their only distinguishing feature is that they occur outside guerrilla conflict. While these are expected to be cases of genocidal consolidation, there is nothing in their coding that would favor one explanation over another.

Elite rivalry

The first analysis adopts two measures of elite rivalry as the independent variable. One measure relies on coup data provided by Marshall and Marshall, which include not only successful and failed coup attempts but also alleged and rumored coups.Footnote 95 Together these provide a good proxy for elite rivalry within the regime. The other measure of elite rivalry is a latent measure that relies on an estimation of the probability of a coup attempt, which consists of observed coups or coup attempts. Here, I rely on data from Powell and Thyne, which integrate various sources of coup data.Footnote 96 To estimate the latent elite rivalry measure, the model estimates the probability of a coup attempt based on the time that a leader has been in office (leader tenure); whether the leader has entered office in the previous two years (new leader); and minor purges in addition to control variables. Leader tenure captures increased stability over time, while new leader captures initial instability associated with new leaders; both are estimated from Archigos.Footnote 97 Minor purges indicates whether regime members are purged in a given year, regardless of their support coalitions or ability to actually threaten the leader's position. As such, it includes purges of rank-and-file members of the regime and is a measure of instability within the regime. Purge data by Banks are adopted as the main proxy for minor purges because they are available for all country years.Footnote 98 Any concerns with respect to the Banks data are addressed in online Appendix B.

Elite purges

The second analysis adopts elite purges as the dependent variable. In contrast to minor purges, elite purges are conceptualized as the purge in any given year of elite rivals that are part of the regime and may actually threaten the leader's tenure and physical security.Footnote 99 Simply being a civilian cabinet minister was not sufficient to be considered an elite rival because coup attempts require control of armed support coalitions. Therefore, purged elite rivals should have formal or informal control of support coalitions that have an armed component, such as the military, secret police, armed paramilitary groups, or praetorian guard. These rivals were operationalized as vice chairmen, senior military officers, chiefs of staff, defense ministers, heads of the secret police, or regional governors in control of armed forces. These elites have a key function within the regime and are not purged alone: elite purges consistently coincide with the removal of rank-and-file members who form their support coalitions. To determine the elite's official position and support coalition within the regime, elite purges were coded only when the name of the purged elite could be established.Footnote 100 It is dangerous to purge elite rivals and elite purges are correspondingly rare. For example, only at four times did Mao purge elite rivals: Manchuria's Governor Gao Gang in 1954, General Peng Dehuai in 1959, Vice Chairman Liu Shaoqi in 1966, and General Lin Biao in 1971. Each of these elite purges corresponds to minor purges of junior regime members that formed these rivals’ support coalitions.

Adverse leader fates and irregular removals

The adverse fates, death, imprisonment, and exile, code whether the leader suffers these fates within five years, excluding natural death. Irregular exit captures whether the leader is forcefully removed from office within five years.Footnote 101 Data on adverse fates and irregular exit were adopted from Archigos,Footnote 102 which have the advantage over coup data—they are collected at the leader level and allow the distinction between two types of irregular exit: internal irregular exits that originate from within the regime and external irregular exits that originate from outside the regime (i.e., rebellions and foreign interventions).

Control variables

Several control variables are expected to be related to mass indiscriminate violence onset or elite purges. The level of authoritarianism, as indicated by the polity score, is expected to affect both mass indiscriminate violence as well as elite purges and was adopted from Cederman, Hug, and Krebs without the PARREG component.Footnote 103 Similarly, gdp per capita and population size have been found to correspond to various types of political violence. These were coded as the log of a country's GDP per capita and population.Footnote 104 Moreover, conflict has been found to correspond to the onset of mass indiscriminate violence.Footnote 105 Irregular conflict in particular is expected to ease armed mobilization for both types of mass indiscriminate violence.Footnote 106 Data on irregular conflict are provided by Lyall and Wilson.Footnote 107 Last, the theory expects militias to be part of the genocidal consolidation process. However, militias might also be related to elite purges regardless of the occurrence of mass indiscriminate violence. Carey, Mitchell, and Lowe provide data on the existence of pro-government militias from 1981 until 2004.Footnote 108 For all mass violence observations before 1981, the presence of formal or informal pro-government militias was researched. With respect to potential genocidal consolidations (noncounterguerilla mass violence), militias are active in all cases before and after 1981. While this supports the expectations in the theory, militias cannot be estimated as part of a regular logit or probit regression on the onset of genocidal consolidation because its absence predicts non-occurrence perfectly.Footnote 109

Elite Rivalry and Genocidal Consolidation Onset

Based on the theory, we expect to observe genocidal consolidation onset at times of high elite rivalry. To test H1, I examine the relationship between elite rivalry (IV) and mass indiscriminate violence onset in the following year (DV). Here, I first estimate a simple model that relies on rumored coups (i.e., coups, coup attempts, as well as rumored or alleged coups) as a proxy for elite rivalry. Coup rumors capture the coup and countercoup posturing within authoritarian regimes and therefore provide an observable measure of elite rivalry and the corresponding risk to a leader's tenure.

Results indeed suggest a strong relationship between genocidal consolidation—operationalized as noncounterguerilla mass violence—onset and elite rivalry. As the first crosstab in Table 3 indicates, genocidal consolidation is, fortunately, rare with only twelve onsets in the data, half of which directly correspond to elite rivalry. More sophisticated analysis, presented in the first column of Table 4, reveals that high elite rivalry indeed corresponds to a significantly higher probability of genocidal consolidation. As expected, counterguerrilla mass violence clearly differs from genocidal consolidation: while the second crosstab in Table 3 suggests a weak correlation between elite rivalry and counterguerrilla mass violence,Footnote 110 the second column of Table 4 shows no significant relationship between elite rivalry and counterguerrilla mass violence.

Table 3. Crosstabs elite rivalry and mass violence

Table 4. Elite rivalry and mass indiscriminate violence onset

Notes: Probit analysis with robust country clustered standard errors in parentheses. Onsets only, ongoing mass indiscriminate violence dropped from the analysis. Corrected for temporal order of elite rivalry and mass indiscriminate violence onsets. * p < .05; ** p < .01. Reported Pseudo R 2 is McKelvey and Zavoina's (Reference McKelvey and Zavoina1975).

While genocidal consolidation is extremely rare, the effects of elite rivalry are considerable, especially when we consider that genocidal consolidation has on average resulted in 700,000 to a million (civilian) deaths. Therefore, a single percentage point increase in the risk of genocidal consolidation corresponds to an estimated 7,000 to 10,000 deaths.Footnote 111 For example, in any given year a median nondemocratic regime has essentially a 0 percent chance (CI 95%: 0.0%; 0.1%) of genocidal consolidation onset; during elite rivalry this percentage increases to 0.6 percent (CI 95%: 0.1%; 1.5%). Similarly, a large country with guerrilla activity, like Indonesia before the return to democracy in 1998, would have an estimated 1 percent risk (CI 95%: 0.0%; 5.0%) without elite rivalry and 5.6 percent risk (CI 95%: 0.7%; 18.4%) with elite rivalry. The model explains a quarter to a third of the variation in the onset of genocidal consolidation. As Tables A.4 and G.8 of the online appendix demonstrate, these results are robust to: random effects; correction for temporal dependence; rare events logit; and the inclusion of militias (using Firth's Penalized Likelihood), civil conflict victory, civil conflict, and horizontal inequality.

Note that elite rivalry is actually a latent risk that we observe only occasionally when there is coup attempt. Instead of relying on coup rumors and allegations, we can estimate elite rivalry by modeling the risk of a coup or coup attempt that a leader faces. To capture the latent rivalry that a leader faces, I estimate a two-stage probit model that first predicts the risk of a coup attempt and then adopts the corresponding estimate as a predictor of genocidal consolidation—operationalized as noncounterguerilla mass violence—and counterguerrilla mass violence onset.Footnote 112 The first stage generates an estimation of the latent risk of coups or coup attempts as a proxy for elite rivalry and is presented in column 3 of Table 4. Columns 4 and 5 of Table 4 present the effects of the estimated latent elite rivalry on counterguerrilla mass violence and genocidal consolidation. The results are supportive of hypothesis H1: elite rivalry corresponds strongly to genocidal consolidation (column 4), but not to counterguerrilla mass violence (column 5). Again, elite rivalry corresponds robustly to genocidal consolidation onset despite the small sample of twelve genocidal consolidation observations. Moreover, the latent model captures a considerable part of the variation in genocidal consolidation—as demonstrated in a pseudo R 2 of .28. As Table A.5 of the online appendix shows, these results are even stronger when adopting my newly collected original data on minor purges instead of the Banks data and are robust to the inclusion of civil conflict or a first-stage model that estimates the risk of successful coups. Admittedly, two-stage models have their limitations and effects are estimated on the basis of a small number of mass indiscriminate violence onsets only. Nonetheless, the strong relationship between both measures of elite rivalry and genocidal consolidation provides considerable support for the theory.

Although an in-depth qualitative analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, the relationship between elite rivalry and mass indiscriminate violence onset can be illustrated with cases of genocidal consolidation. As mentioned, mass indiscriminate violence in Cambodia took place under conditions of heightened elite competition following victory in war. In Rwanda, the deeply factionalized Hutu elite competed in a highly volatile political environment; the months before the genocide were characterized by political murders,Footnote 113 organized mob attacks on officials,Footnote 114 and the build-up of armed militias.Footnote 115 The Hutu military was similarly divided with the risk of a coup at an all-time highFootnote 116 and senior officers openly siding with either faction.Footnote 117 The assassination of the president and chief of staff pushed this rivalry to its horrid conclusion. While the “reactionaries” were fighting for control of Kigali and began killing civilians, their “reformist” rivals assumed control of a deeply divided military: for three days, the reformist-controlled Rwandan army exchanged gun- and even artillery fire with the reactionary-controlled Presidential Guard in and around Kigali.Footnote 118

Similarly, Indonesia, Uganda, Burundi, and Nigeria had coups or coup attempts in the months preceding the onset of mass indiscriminate violence. At the advent of the Cultural Revolution in 1965–66, Mao both faced an alleged coup plot and was in open conflict with his influential Vice Chairman Liu Shaoqi,Footnote 119 while Burundi had a rumored coup.Footnote 120 Most of the cases that did not have coup events in the data do suggest severe competition between factions within the regime at the start of the violence, such as Serbia/Yugoslavia,Footnote 121 Rwanda in 1964,Footnote 122 and Sudan.Footnote 123 These illustrative cases suggest that the quantitative models are correctly capturing elite rivalry: genocidal consolidation does indeed occur under heightened elite rivalry.

Genocidal Consolidation and Elite Purges

Leaders are more likely to turn to genocidal consolidation during high elite rivalry, but do they successfully purge elite rivals as part of the genocidal consolidation process? According to the theory, the onset of noncounterguerilla mass violence should be followed by elite purges (H2). As becomes clear from simple description and more sophisticated analysis, results suggest a very strong relationship between genocidal consolidation—operationalized as noncounterguerilla mass violence—and elite purges.

The descriptive Figure 3 contrasts the incidence of elite purges in genocidal consolidation years to years without genocidal consolidation in a variety of reference categories and is strongly suggestive of a relationship. Where elite purges occur in half of genocidal consolidation years, they occur in only 13 percent of other years, 11.4 percent of counterguerrilla mass violence years, and 23.2 percent of at-risk years. Even leaders who actually commit genocidal consolidation have elite purges in only 3.5 percent of the years outside of genocidal consolidation, which suggests that the correspondence of elite purges and genocidal consolidation is unlikely to be driven by inherently violent leaders.

Figure 3. Incidence of elite purges during genocidal consolidation compared to reference categories at other times

Similarly, the columns in Table 5 demonstrate a strong relationship between genocidal consolidation in any given year and elite purges the following year. The first column shows that when we pool mass indiscriminate violence and do not distinguish between counterguerrilla mass violence and noncounterguerrilla mass violence, mass indiscriminate violence corresponds to elite purges. When we consider the type of mass indiscriminate violence in column 2 of Table 5, however, it becomes clear that genocidal consolidation corresponds to elite purges, while counterguerrilla mass violence does not. This provides strong support for H2 and also demonstrates that genocidal consolidation significantly (at 5% level) differs from counterguerrilla mass violence. Column 3 shows that the findings are robust to dropping militias from the analysis, which is available from only 1981.

Table 5. Probit on elite purges for genocidal consolidation and counter-guerrilla mass violence spells

Notes: Probit analysis with robust country clustered standard errors in parentheses. * p < .05; ** p < .01. Reported Pseudo R 2 is McKelvey and Zavoina's (Reference McKelvey and Zavoina1975). ‡Precise temporal coding.

The model presented in column 4 shows the preferred specification. While purges occur in the later stages of the genocidal consolidation process, genocidal consolidation can occur so rapidly that these purges cannot be reliably captured with one-year lags. For example, in Rwanda consolidation occurred within two weeks. Fortunately, because we know the exact timing of purges and the mass violence onsets, we can precisely determine whether elite purges occur before or in the year after the onset of mass violence.Footnote 124 With a precise correction for temporal order, the findings are, again, statistically significant and sizable. A median nondemocratic regime has a predicted probability of elite purges of 0.14 (CI 95%: .07; .24). During, or shortly after, genocidal consolidation, however, a median authoritarian regime has a predicted probability of elite purges of 0.59 (CI 95%: .44; .72), which is a statistically significant increase in probability of .45 (CI 95%: .31; .58).

The analysis in column 4 demonstrates that elite purges occur at a higher rate during genocidal consolidation than during other—less violent—times within countries that have, or were likely to have, experienced mass violence. However, while this provides a straightforward interpretation of results as support for the relationship between elite rivalry and genocidal consolidation, these regular authoritarian observations might potentially not be representative of observations in which genocidal consolidation could occur. Therefore, column 5 repeats the analysis of column 4 with an at-risk sample to alleviate any selection concerns: do elite purges occur at a higher rate during genocidal consolidation than at times when genocidal consolidation is most likely?

Specifically, I first estimate the propensity of genocidal consolidation based on the specification of model 1 of Table 4. I then select all observations for which the propensity of both treated (genocidal consolidation) and control cases (no genocidal consolidation) is greater than 0.01; this corresponds to roughly 10 percent of observations that are most at risk of genocidal consolidation and similar on observables.Footnote 125 Because the propensity of genocidal consolidation is based on high elite rivalry, column 5 effectively tests a stronger assumption: that elite purges occur at a higher rate during genocidal consolidation than at other times of high elite rivalry.

Nonetheless, results show that elite purges occur at a higher rate during genocidal consolidation than at high-risk times. Again, the findings are statistically significant and sizable. A median at-risk nondemocratic regime with a high propensity for genocidal consolidation has a predicted probability of elite purges of 0.13 (CI 95%: .07; .19). A median authoritarian regime with similar propensity for genocidal consolidation has a predicted probability of elite purges of 0.54 (CI 95%: .27; .78) during, or shortly after, genocidal consolidation. This is a statistically significant increase in probability of .41 (CI 95%: .17; .64). Results are robust to the inclusion of civil conflict; the correction for unobserved heterogeneity using random effects; and controlling for horizontal inequality.Footnote 126 This relationship between mass indiscriminate violence and purges of ingroup elites cannot be explained by rival explanations and is strongly supportive of the theory of genocidal consolidation.

The purge of rival elites is part of the mass indiscriminate violence process in most cases of indiscriminate violence that are expected to be instances of genocidal consolidation. As mentioned, genocidal consolidation in Rwanda took only two weeks: by then, General Gatsinzi and the remainder of the reformist military command as well as all reformist prefects—high-ranking officials in control of regional security—had been purged from the regime.Footnote 127 In Cambodia, for example, Khmer elite were purged left and right during the mass killings.Footnote 128 The most dangerous competitor to Pol Pot's Khmer faction was the Vietnamese-trained Khmer branch, which found its support base in the eastern regions of the country. Early attempts at purging this rival branch failed. Therefore, the eastern regions were last to be targeted with mass indiscriminate violence followed by purges of the eastern Khmer elites.Footnote 129 In China, collectivization, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution led to the fall of Mao's most influential rivals, such as regional leaders Gao Gang and Jao Shu-Shih; General Peng Dehuai; and second-in-command Liu Shaoqi.Footnote 130 Similar trends can be observed in Yugoslavia/Serbia, Indonesia, and Nigeria.Footnote 131 Even cases that did not have conclusive evidence of elite purges, such as Rwanda in 1964 and Burundi in 1972, have considerable circumstantial evidence of resolution of pre-existing rivalry and consolidation after the violence.Footnote 132 These short examples are illustrative of the quantitative findings. Noncounterguerilla mass indiscriminate violence does indeed correspond to purges of ingroup elites as predicted by the theory.

Genocidal Consolidation, Adverse Fates, and Irregular Removals

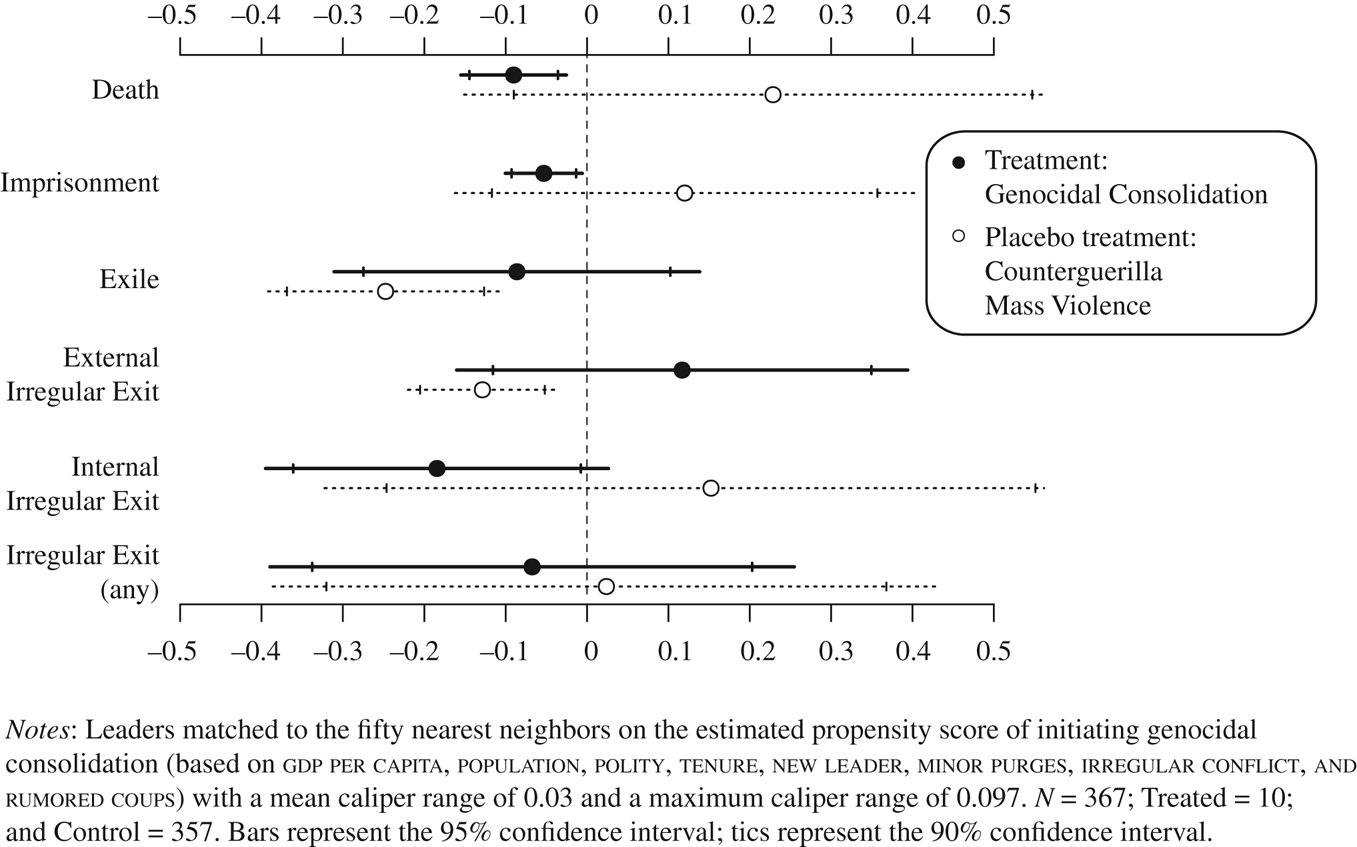

Leaders under conditions of high elite rivalry adopt genocidal consolidation to purge key elite rivals, but does this strategy translate into greater odds of political and physical survival? According to the theory, genocidal consolidation—operationalized as noncounterguerrilla mass violence—should predict a reduced likelihood of adverse leader fates and irregular removal originating from within the regime. To arrive at the effects of genocidal consolidation on leader survival, we need to account for selection effects. Specifically, the theory of genocidal consolidation leads us to expect that those leaders who experience the greatest risk of losing office are also the most likely to adopt genocidal consolidation as a strategy to win elite rivalry. Consequently, it is not sufficient to simply estimate the effects of genocidal consolidation on leader survival. Rather, we should approximate the relevant counterfactual: are leaders who adopt genocidal consolidation more likely to survive than their most similar counterparts who do not? To compare most similar leaders, I match leader observations on the estimated propensity of initiating genocidal consolidation. The propensity score is estimated on observed covariates by regressing genocidal consolidation onset on gdp per capita, population, polity, tenure, new leader, minor purges, irregular conflict, and rumored coups.Footnote 133

Results indicate that leaders who initiate genocidal consolidation indeed have a considerably higher probability of survival than their most similar counterparts who do not. The filled dots in Figure 4 represent the average treatment effect of genocidal consolidation on adverse leader fates and irregular leader exits of leaders who adopt genocidal consolidation. Positive coefficients correspond to an increased probability of adverse leader fates and irregular exits, while a negative coefficient corresponds to a reduced probability. The bars represent the 95 percent confidence interval and tics represent the 90 percent confidence interval. The analyses in Figure 4 are at the leader level in which genocidal consolidation leaders are matched to fifty most similar leaders within a propensity score range of .1 as counterfactuals.Footnote 134 For each leader in the control group only the year with the greatest predicted probability for genocidal consolidation was used, based on the model presented in column 1 of Table 4.

Figure 4. Average treatment effect of genocidal consolidation on adverse leader fates

With respect to adverse leader fates, Figure 4 demonstrates that leaders who adopt genocidal consolidation have a statistically significant reduced risk of death or imprisonment.Footnote 135 This supports the expectation that genocidal consolidation protects the leader from the more acute dangers of elite rivalry. A sensitivity analysis reveals that these results are robust to unobserved covariates.Footnote 136 At the same time, genocidal consolidation does not significantly affect the risk of exile—potentially because leaders exchange the more acute internal threat for a lesser external threat. With respect to irregular exits, Figure 4 demonstrates that leaders who adopt genocidal consolidation on average have a reduced risk of internal irregular exits—originating from within the regime.Footnote 137 Leaders exchange this for an increased, yet insignificant, risk of an external irregular exit—originating from outside the regime. Although we cannot show that leaders initiate genocidal consolidation because of within-group threats, these results imply that those who do have an increased likelihood of survival. An additional robustness check with counterguerrilla mass violence as a placebo treatment—represented by the open dots in Figure 4—demonstrated no effects on death, imprisonment, or internal irregular exits as expected. Leaders who initiate counterguerrilla mass violence have a reduced risk of both external irregular exits that originate from outside the regime and corresponding exile fates.Footnote 138 As predicted, these results indicate that leaders who adopt genocidal consolidation exchange the greater risks of elite within-group competition for the lesser risks of between-group competition.

Upon close examination, we see that leaders who initiate genocidal consolidation do successfully deal with elite rivals. Even in cases such as Rwanda and Cambodia where leaders ultimately lost power, they were ruthlessly successful against ingroup rivals; only after they had purged their rivals within the regime were they removed through military intervention originating from outside. Moreover, because of the safer distant threat of military intervention as opposed to the close threat of a coup, both Pol Pot's regime as well as the genocidal Akazu regime were able to evade capture.Footnote 139 Other leaders, such as Mao, Suharto, and Milošević successfully consolidated their power. The neutralization of acutely critical ingroup rivalries allowed Micombero, Amin, Gowon, Kayibanda, and Bashir to survive.

Conclusion

In this paper, I explain mass indiscriminate violence that occurs outside of counterguerrilla campaigns as genocidal consolidation. Building on new original data on the type of mass indiscriminate violence and on elite purges, this study has established that: (1) genocidal consolidation is distinct from counterguerrilla mass violence; (2) elite rivalry corresponds to a greater likelihood of genocidal consolidation; (3) genocidal consolidation corresponds to a greater probability of elite purges; and (4) leaders who successfully initiate genocidal consolidation have a significantly reduced probability of adverse leader fates such as death and imprisonment as well as of irregular removal through internal sources. Fortunately, genocidal consolidation is rare, which challenges us to base its understanding on a relatively small body of evidence. Therefore, these quantitative findings by themselves provide only partial evidence for the theory. However, taken together and in combination with the qualitative trends, these findings suggest a robust relationship between elite rivalry and mass violence and provide considerable support for the theory of genocidal consolidation versus alternative explanations. The findings thereby support the proposition that genocidal consolidation is instrumental to leader survival and suggest that it should indeed be viewed as part of a process of authoritarian competition.

Two broader observations follow with respect to the study of conflict and the emerging field of authoritarian politics. First, as this study demonstrates, a key class of conflicts cannot be examined as a bargaining problem between two actors. Especially in conflicts in which authoritarian regimes seem to act irrationally violent and belligerent, the conflict may be better explained by within-group competition and the benefits to leader survival that the conflict may generate. Second, the study provides an initial answer to the question of how authoritarian leaders may consolidate power when they are least secure. This question merits further attention as part of the emerging field of authoritarian politics and points toward a strong connection between mass political violence and authoritarian politics.

By introducing a novel theory and a new piece of the mass violence puzzle, this study also raises new questions. I believe three venues of research are particularly promising. First, careful process tracing should determine whether established quantitative patterns consistently hold within potential cases of genocidal consolidation. Second, elite rivalry is much more common than genocidal consolidation. Therefore, disaggregate research into authoritarian support coalitions should further determine the conditions under which authoritarian leaders facing elite rivalry adopt genocidal consolidation, interstate war, or alternative strategies to strengthen their support coalitions and undermine those of their rivals.

Last, the potential interaction of elite rivalry and ideology merits further exploration. While ideology and mass violence are undeniably connected, ideology remains difficult to pin down empirically. In the spirit of theoretical parsimony, I have introduced the genocidal consolidation theory as agnostic about the role of ideology. Instead, it provides a clear, rational explanation for seemingly irrational behavior that explicitly does not require ideologically motivated leaders, elites, or perpetrators. However, it also explicitly doesn't argue that ideology is unimportant—on the contrary. Ideology could steer perpetrators, link perpetrators’ individual motives, or define the range of options open to elites, for example. Future research into potential synergy of elite rivalry and ideology in producing mass violence is therefore likely to be especially fruitful for our understanding of mass violence.

With respect to policy implications, there is reason for pessimism. Genocidal consolidation occurs once a decade and, under conditions of deadly internal competition, it pays. Therefore, we should likely expect more occurrences in the future. Moreover, genocidal consolidation has previously occurred with relatively little warning, quick resolution, and the highest number of civilian casualties. Genocidal consolidation alone accounts for between eight and twelve million (civilian) deaths since 1945. A better understanding of the mechanisms underlying this particular type of violence would be a key step toward improving early warning systems.

Regimes in the process of genocidal consolidation might be particularly vulnerable to outside intervention. Behind the scenes of genocidal consolidation, rival elites—as well as their supporters in the military, bureaucracy, and security institutions—are fighting for survival. While ingroup elites cannot show open defection, outside pressure may be secretly welcomed and lead the genocidal system to come crashing down. The Rwandan military was remarkably passive against the RPF rebels during the genocide as senior Hutu officers went into hiding. Similarly, there was little resistance to outside intervention in Uganda, Cambodia, or Kosovo. Moreover, there is likely no moral hazard for interventionFootnote 140 in genocidal consolidation in particular; rebels cannot push governments to genocidal consolidation in order to invite foreign intervention because genocidal consolidation is unrelated to rebel behavior. While rapid outside intervention may be politically or militarily unfeasible and may even expedite the killing, it should be seriously considered in light of these findings. Ultimately, policymakers should design interventions that take elite rivalry within the genocidal regime into account. In the case of genocidal consolidation, interventions should not only resolve bargaining failures between groups but also consider the strategic considerations of authoritarian elites as well.

Genocidal consolidation may be rare but it comes at a high cost in life, even when compared to other types of mass political violence. Violent episodes as diverse as that of Stalin's collectivization, the Cambodian killing fields, the disintegration of Yugoslavia, and the Rwandan genocide have enduring consequences for security and economic development. While additional research is necessary, results suggest that genocidal consolidation is instrumental to winning ingroup rivalry and intimately related to authoritarian competition. Genocidal consolidation is therefore not driven by the random madness of leaders, nor by the desire to kill an outgroup, but by the structural constraints and commitment problems that authoritarian leaders face.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VJTPJK>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000259>.

Acknowledgments

I thank Giacomo Chiozza, Michaela Mattes, Joshua Clinton, Kristian Gleditsch, Sheida Novin, Ursula Daxecker, Lee Seymour, Aila Matanock, Kristine Eck, Andrea Ruggeri, Markus Haverland, Jun Koga, Julia Bader, Marlies Glasius, Cindy Kam, Frederico Batista, Mollie Cohen, Matthew DiLorenzo, Bryan Rooney, Steve Utych, and the audiences at MPSA, ISA, NEPS, University of Amsterdam, Erasmus University Rotterdam, U.C. Berkeley, and Leiden University for their insightful comments and constructive criticisms. I am also particularly grateful for the high-quality review process at IO and the insightful suggestions of the editor and the anonymous reviewers.