As midnight approached on the evening of 15 September 1910, an estimated 100,000 people crowded into Mexico City's Plaza de la Constitución (El Zócalo) to commemorate the centennial of Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla's cry for political independence from imperial Spain.Footnote 1 In staging the event, organisers had decorated the facades of downtown buildings and mansions with electric lights, flags and portraits of revolutionary heroes, and had commissioned military bands to roam the streets playing patriotic marches.Footnote 2 Officials had also draped the national Cathedral with electric lights in the national colours of white, green and red, and had placed neon designs at the bases of the twin towers that read: ‘1810 Libertad’ and ‘1910 Progreso.’Footnote 3 Fireworks preceded the widely anticipated Grito, the president's annual cheer celebrating Mexico's independence heroes and the patria. One eyewitness observed that ‘the night was cold, but people perspired and fainted and swooned from heat and lack of air. One could not fall in such a crowd; some, weary, slept on foot.’Footnote 4 Earlier that day, President Porfirio Díaz, whose Liberal government had governed Mexico since 1876, had celebrated his eightieth birthday with 15,000 specially invited guests at Chapultepec Castle, where both he and Señora Díaz had appeared ‘delightfully animated.’Footnote 5

Mexico's 1910 Centenario reflected a popular trend in Western Europe and its former colonies to celebrate centenaries of important political and cultural events, including revolutions that had changed national histories. Centennials expressed both elite and popular attitudes toward historic moments and individuals, and contributed to the creation of secular heroes and holidays, a process encouraged in the widely read works of the French positivist, Auguste Comte, and the Scottish historian, Thomas Carlyle. Centennials of revolutions also served as battlegrounds for competing political communities to construct collective memory and political culture through images and words. As such, they provided unique opportunities for those in power to justify their programmes through historical associations with heroic figures and seminal events, as well as the chance for their political opponents to propose counter-narratives.Footnote 6 As a rule, republican governments tolerated more dissent from political adversaries than monarchical or dictatorial regimes, although repression of free speech and the right to disagree sometimes provoked violent responses.

In nineteenth-century Mexico, Independence Day celebrations served as forums for elites to promote political philosophies and programmes through critiques of the Spanish colonial experience and the actions and programmes of revolutionary leaders. Liberals criticised the colonial era and praised Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla and José Maria Morelos y Pavón, whose largely indigenous movements had attacked Spanish peninsular elites, adopted the Virgin of Guadalupe as their standard, and symbolised radical change adaptable to Liberals' political agenda. Conversely, Conservatives identified with Spanish culture, supported the Catholic Church, and praised Agustín de Iturbide, whose ‘Army of the Three Guarantees’ had promised social, racial and religious stability. Disputes over ideology and programmes deeply divided the nation, and led Conservatives to place personal interests over national interests by supporting France's imposition of the Emperor Maximilian in 1862.Footnote 7

Benito Juárez's victory over Maximilian eventually led to the rise of General Porfirio Díaz to the presidency in 1876, whose blend of liberalism, positivism and authoritarianism achieved political stability and economic growth. In 1910, Díaz and his inner circle used the Centennial of Mexico's independence struggle to promote the regime's achievements within the context of their official version of Mexican history. Centennial planners honoured Hidalgo and Morelos and presented a historical genealogy in words and symbols that linked these founding fathers with the dictator. As such, the Centennial attempted to conflate identity with the nation with identity with the regime, and to associate state formation and civic culture with Liberal leaders and policies.

The Centennial's planners delivered their message through a variety of visual statements, such as parades, monuments, public buildings and commemorative stamps, as well as academic conferences, speeches and official publications. The intended result was an image of peace, order and progress, and Mexico's acceptance by Western Europe and the United States as a modern nation. The carefully orchestrated series of month-long events conveyed multi-layered messages addressed to rich and poor, literate and illiterate, Mexican and foreigner.

The 1910 celebration represented the culmination of the Liberal era in modern Mexican history. The Centennial featured a modernised Mexico City, a ceremonial reconciliation between Mexico and Spain, a historical parade (desfile histórico) that presented a liberal version of Mexican history, and the promotion of Morelos as a mestizo icon and symbol for national identity and integration. The Centennial combined methods of expression commonplace in colonial celebrations, such as banners, fireworks and allegorical carriages,Footnote 8 with innovations found at international fairs, especially exhibitions promoting economic and cultural achievements.Footnote 9 The celebration also unveiled monuments honouring independence and Liberal leaders, museum renovations, and institutional improvements, such as new schools, an asylum for the insane, and public works projects.

The Centennial's audience included hundreds of thousands of Mexico City residents as well as visitors from the provinces, the United States, Europe and Asia. The international press described the celebration in positive terms, and the liberal press characterised the events as festive, patriotic and popular. Nevertheless, eye-witness testimony of public behaviour and criticism by the conservative press revealed variations in interpretation based on ideological, cultural or national perspectives. Foreign dignitaries and journalists, who were treated as guests of honour, viewed events from privileged vantage points and praised the regime, whose policies favoured foreign investors. On the other hand, Conservative elites predictably objected to the Centennial's portrayal of Mexican history, and the popular classes viewed things from different cultural perspectives and offered distinctive interpretations.

The organisers' portrayal and treatment of indigenous people also revealed the ambivalence of Liberal elites towards this group. While the Centennial celebrated the nation's pre-Columbian cultures with museum exhibits, international congresses, and a special tour of Teotihuacán, elites considered contemporary natives a drag on development and an embarrassment. During the Centennial, they attempted to keep natives from public view except as historical props in the Desfile Histórico and as living manikins in museum displays. The Centennial's promotion of acculturation through public education and mestizaje can also be read as criticism of indigenous culture. For their part, some Indians demonstrated mistrust of the federal government by refusing to participate in the Desfile Histórico.Footnote 10

The Centennial provided other glimpses of political dissent. The Mexico City Town Council, a lingering bastion of Spanish influence, pressured organisers to include Agustín de Iturbide in the Desfile Histórico, and maderistas twice disrupted the celebration and bravely confronted the police. As events would shortly reveal, the Centennial was Díaz's grand finale. Francisco I. Madero's call to arms in November would be answered by a mélange of agrarian rebels, anarchists and political opportunists who would carry the fight from the countryside to the national capital. After Díaz's resignation, revolutionary governments continued to use Independence Day celebrations, including another centennial in 1921, to promote their programmes and ideology. While officials and supporters demonised Díaz and the Porfiriato in a new version of Mexican history, revolutionary governments simultaneously reframed many liberal era programmes, including public education, anti-clericalism, and the promotion of the mestizo nation, under the imprimatur of revolutionary nationalism.Footnote 11

The Mexican Centennial of 1910 in global perspective

The Mexican Centennial, viewed as an attempt to fashion historical memory for political objectives, reflected an international trend in Europe and its former colonies. Around the world centennial celebrations of revolutions sparked debates among rival groups who contested the meaning of what had been established, altered or destroyed. There has been some excellent research on this theme for France, and historians have noted its importance for other countries. A brief look here at a handful of centennial celebrations elsewhere will introduce some common threads and points of comparison with Mexico.

The French Revolution had inspired Latin American independence movements, and the impact of this ‘mother revolution’ was still being debated by the French a century later. The centennial of the French Revolution in 1889 was organised by a republican government to celebrate ‘Liberty, Equality and Fraternity’ and the ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man,’ principles that had inspired democracy and citizenship in the West. At the same time, the celebration gave French monarchists and Catholics the opportunity to present counter-narratives that criticised the Revolution for doing more harm than good. They focused on the violent excesses of the Terror; mourned the execution of Louis XVI, whom they viewed as a political reformer; portrayed the French as pious defenders of the Catholic Church (for example, in the Vendée), and lamented the Church's diminished role in education, culture and society.Footnote 12 These convictions found ideological kinship and political expression in Mexico, where conservatives recoiled from the memory of the Hidalgo Rebellion (including the slaughter of Spaniards at the Alhóndiga de Granaditas), supported the empires of Agustín I and Maximilian, and championed the Catholic Church before and after the Porfiriato.Footnote 13

Commemorations of political independence in other former European colonies, such as the United States and Southern Africa, also reveal the conflicting historical constructions of the colonisers, the colonised and the enslaved. In 1876, the United States' Centennial predictably ignored the historical contributions of African Americans, reflecting the whites' control over national politics, institutionalised racism, and the legacy of slavery. However, Black newspapermen in Cincinnati, Ohio, responded to this omission by commissioning an eighteen-volume history of African Americans, and the historian, George Washington Williams, recalled that African slaves had created the Republic of Haiti. Angry Blacks also published the ‘Negro Declaration of Independence’, which accused the United States of failing to protect their constitutional rights while forcing them to pay taxes.Footnote 14 Such protests indicate the appearance of counter-narratives among educated African-Americans, and foreshadow more balanced histories and public perceptions of Blacks following the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s.

The Anglo-Boer War's centenary in 1999 occurred within a political environment that invited reconstructions of the conflict by the colonised. Previous commemorations of the war, organised under Afrikaner governments, stressed the heroism of the Boers and the barbarity of the British concentration camps, with references in the press to Lord Kitchener as a ‘British Hitler’ and to Elizabeth II as the ‘great grand-daughter of a cruel Queen’.Footnote 15 The centenary was organised, however, following the rise to power of the African National Congress. President Thobo Mbeki's government linked Boers and Africans together in a common struggle against British imperialism, and saw it as an opportunity for ‘nation-building’ and ‘national reconciliation’.Footnote 16 On the other hand, grim reminders of British concentration camps for Africans and apartheid created a public discourse characterised as an ‘Olympics of suffering’. Such contested terrain over historical memory emerged from an inverted political environment that permitted Africans to challenge the traditional narrative.Footnote 17

As we approach the bicentennial of Latin American independence, we can anticipate contested visions of historical memory in forthcoming national celebrations. In Bolivia President Evo Morales has already linked his populist indigenous movement with pre-Columbian symbols and revolutionary icons, and has promised his native followers meaningful reforms to reverse centuries of poverty. At his inauguration Morales invoked such diverse revolutionaries as Manko Inca, Tupaj Katari and Ché Guevara, adding: ‘I wish to tell you, my Indian brothers, that the 500 year indigenous and popular campaign of resistance has not been in vain … We're taking over now for the next 500 years. We're going to put an end to injustice, to inequality.’ The previous day, at the ancient city of Tiwanaku, Morales made an offering to Pachamama, the earth goddess, and appeared before the temple of Kalasasaya, ‘barefoot and dressed as a sun priest … [where] … in front of thousands of supporters, he received the baton, encrusted with gold, silver and bronze, that will symbolise his Indian leadership.’ Now that he has raised the expectations of his followers, Morales must somehow devise, fund and deliver reforms within a deeply divided political, economic and social environment.Footnote 18

Planning the Mexican Centennial

On 1 April 1907, President Díaz appointed a ten-member commission to organise the Centennial celebration, instructing them to glorify his presidency within the context of Mexican history.Footnote 19 The Commission chair, Guillermo Landa y Escandón, the governor of the Federal District, pledged to make the event ‘historically significant’ and to arouse ‘popular enthusiasm’ for the president's ‘service to the grand ideals that people desire who seek to live in the bosom of civilisation’.Footnote 20

The idea for a gala Centennial celebration dates from the 1890s when Antonio A. Medina y Ormaechea, a prominent lawyer, wrote a series of articles and editorials in El Foro, which he later published as a book.Footnote 21 Medina advocated linking the Centennial with an international exhibition that would primarily serve to showcase Mexico's economic potential for foreign investors and immigrants from the United States and Western Europe. Medina also suggested massive construction projects in Mexico City, such as an industrial palace and parks, whose usefulness would endure after the event. Although he lamented the cultural and economic backwardness of Mexico's large Native American population, he praised the country's workers, farmers, artisans and intellectuals, whose industriousness would impress foreigners. Clearly, for Medina the Centennial's economic potential superseded its patriotic and civic appeal, and his argument likely resonated with Mexico's leaders who had underwritten impressive exhibits at World Fairs to entice foreign investment and immigration.Footnote 22

The Centennial planners consciously courted foreign publicity and acceptance by inviting official delegations from Europe, Asia, and the United States, and by underwriting visits by journalists from major newspapers in the United States, Europe and Canada. Planners also organised international conferences and congresses and invited distinguished scholars and university administrators from abroad with a professional interest in Mesoamerican culture and history.Footnote 23

At the same time the Centennial Commission also targeted the hearts and minds of Mexicans. The organisers painted an official history that linked Independence era heroes with the Liberal icons, Benito Juárez and Porfirio Díaz, and promoted a civic culture to overshadow the Catholic Church's cultural and educational pre-eminence. National political and cultural integration – the forging together of Mexico's disparate and racially diverse provinces – benefited from railway construction, urbanisation, consumerism and expansion of the print media, all products of the Porfirian economic ‘miracle’. Civic culture invented in Mexico City was designed to spread into the provinces through secular schools and public events such as the Centenario, and local-level Centennial committees organised patriotic events and commissioned commemorative monuments, plaques, parks, schools, hospitals and other structures.Footnote 24 As a final bonus, the Centennial provided the perfect occasion for Liberals to honour Porfirio Díaz, whose birthday coincided with Mexican Independence Day. On the day the General turned 80, the traditional Grito would mark 100 years of independence, 50 years of Liberal rule, and 34 years of dictatorial stability and progress.

Financing the Centennial

Until the late nineteenth century the lack of political and financial stability made it difficult for the federal government to fund anything other than essential administrative tasks. However, the importance of Independence Day to national identity formation, particularly during a period of conflict over philosophical and political direction, created political opportunities that could not be ignored. Political elites thus used Independence Day as a platform to promote their particular party's accomplishments and ideology within the context of the Independence era. Elites with close ties to the party in power formed Juntas Patrióticas and raised the necessary 5,000 to 7,000 pesos to fund traditional Independence Day celebrations, which typically consisted of patriotic speeches, fireworks and the distribution of political literature.Footnote 25

By 1910, following decades of political stability and economic development, the federal government had more resources to spend on the Centennial (see Table 1), and the organisers hoped that this would be supplemented by donations from businesses, prominent citizens and professionals. This was not unreasonable. Corporations had benefited from the pro-business policies of the Díaz dictatorship, and Liberal politicians and many professionals owed their careers to the regime. Moreover, the Centennial was also designed to promote the accomplishments of the administration and those associated with it. Still, only a handful of cabinet secretaries made significant donations to the Centennial Commission, professionals gave sparsely, and many corporations donated nothing at all (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 1. Federal Allocations for Centennial Events, excluding Major Construction Projects and the Cost of Security, Sanitation and Other Municipal Services

Source: Memoria de los trabajos, p. 100.

Table 2. Money Donated to the Centennial Commission

Source: Memoria de los trabajos, p. 100.

Table 3. Largest Donors to Fund Centennial Events

* Contribution earmarked for construction of an allegorical float honouring the mining industry.

** Corral was appointed Vice President in 1906.

Source: Memoria de los trabajos, p. 100.

This pattern of giving suggests that company directors viewed the Centennial more as an advertising opportunity than a political obligation. The industrial and commercial parade, underwritten by participating businesses, would be viewed by tens of thousands of potential customers and would receive extensive newspaper coverage. On the other hand, cash donations given to the Centennial Commission with no strings attached might be spent on activities that brought no attention to the donor or to his company. It is also likely that companies located in the provinces underwrote Centennial celebrations closer to their places of business. We know, for example, that in 1869 a railroad company paid for the Independence Day celebration in Puebla, and that President Juárez and his cabinet were among its honoured guests.Footnote 26 Moreover, in company towns, such as mining communities in the north, corporate sponsorship of Independence Day celebrations would have enhanced patron-client relations and pleased municipal authorities.

The Centennial also provided Mexico City's foreign communities with the opportunity to improve their image among Mexicans by commissioning statues of compatriots with positive historical associations with Mexico. For example, the French commissioned a statue of Louis Pasteur, whose scientific achievements complemented local efforts to improve public health; the Germans unveiled a monument of Alexander von Humboldt, the author of a famous scholarly account of New Spain; and the US colony paid for a statue of George Washington, the leader of its revolution against European colonial rule.Footnote 27

Among Mexicans, professional groups gave sparsely to the Centennial Commission. For example, collectively, attorneys contributed 133 pesos, architects 133 pesos, public notaries 159 pesos, and educators 1,500 pesos.Footnote 28 Why the tepid response? Despite the push to develop a civil culture, a tradition of giving to support secular celebrations had not developed. Moreover, most professionals, apart from a few wealthy attorneys, likely had limited financial resources as well as fluid political ties to the regime. Among the Porfirian inner circle, some high-profile cabinet members made respectable donations, but most contributed to the Centenario in other ways. For example, Justo Sierra and other cabinet members hosted major events, wealthy elites invited visiting dignitaries to stay in their mansions, and the gente decente coveted invitations to balls, banquets and fancy receptions, particularly those events hosted by President and Sra. Díaz.

The Centennial showcased a variety of activities and services that reveal important aspects of the government's agenda. As Table 4 indicates, the cost of transporting, housing and feeding dozens of foreign journalists and editors, overwhelmingly from major newspapers in the United States, represented the largest non-construction related expense. Positive foreign press coverage of the Centennial would impress foreign investors, promote Mexico's image as a modern country, and enhance the reputation of the regime. No correspondent or editor, no matter how objective he might be, would be predisposed to harsh criticism after his trip had been underwritten. Other costly events included the historical procession, which presented a Liberal version of Mexican history, and a statue for Morelos, a tribute not afforded to Creole leaders of independence.

Table 4. Principal Expenditures from Federal Centennial Funds and Donations

Source: Memoria de los trabajos, p. 100.

As part of the Centennial celebration, federal officials also unveiled monuments and buildings built with regularly allocated federal funds. These structures illustrated a viewpoint or policy of particular historical or programmatic significance to the regime, underscored in speeches and newspaper reports, which constructed historical associations and celebrated Liberal leaders and their programmes. These construction costs far surpassed other Centennial-related activities and amounted to substantial investments of federal funds. For example, the cost of the Independence Monument alone exceeded Mexico's total expenditures for the 1889 Paris Exhibition.Footnote 29 Only the largest construction projects completed for the Centennial appear in Table 5, and final costs for some projects are unknown. Also unknown are the costs of renovating and cleaning-up parks, thoroughfares and streets in preparation for the Centennial celebration.

Table 5. Cost of Major Monuments, Public Buildings and Other Construction Projects Inaugurated during the Centennial

* Projected.

** This amount only represents the cost of the land.

*** Paid for primarily through private donations.

Source: García (ed.), Crónica Oficial, Appendix, pp. 58–9; 210–1; Tenenbaum, ‘Streetwise History: The Paseo de la Reforma and the Porfirian State, 1876–1910’ in William H. Beezley et al. (eds.), Rituals of Rule, Rituals of Resistance: Public Celebrations and Popular Culture in Mexico (Wilmington, 1994), p. 147.

Setting and audience

Centennial planners selected as parade routes boulevards that could accommodate large allegorical carriages pulled by teams of oxen as well as hundreds of marchers in the Desfile Histórico. The routes began at accessible assembly points and ended at sizeable plazas or open spaces appropriate for closing ceremonies and the dispersal of marchers. Ideally, ample space would also be available along the boulevards to accommodate tens of thousands of spectators. The spatial challenges of planning Centennial events surpassed previous republican era ceremonies, and they provide glimpses of the progress and contradictions of the Porfirian era.

Organisers planned most Centennial parades to unfold along the Paseo de la Reforma, the grand boulevard that linked the city's historic centre with its recently developed western suburbs. Parades began near the western terminus of the thoroughfare at the Nuevo Bosque de Chapultepec, the site of the presidential palace remodelled by Emperor Maximilian to resemble his castle on the Adriatic, and terminated at the Plaza de la Constitución, or the Zócalo, the ancient capital's major square and political centre. As Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo has observed, this area resembled Haussmann's remodelling of Paris and it cast the image of an ideal city. The suburb featured mansions recently built by elites who had fled the inner city, and it enjoyed a variety of public services largely unavailable to other residents of the capital. For example, the area boasted well-maintained public gardens, an electrified trolley system, street lighting, and modern plumbing and sewer systems. For Centennial events, the Paseo de la Reforma's generous width and length accommodated parades and large crowds, and the trolley made it accessible to those who could afford the modest fare.Footnote 30 On the other hand, as parades and crowds entered into the city centre, streets narrowed and spectators became compressed and sometimes unruly (see Figures 2 and 3, p. 517).

Glorietas (large roundabouts) featuring impressive monuments honouring famous people or events intersected the Paseo de la Reforma at strategic locales and served as snap-shot history lessons for everyday pedestrians and those viewing Centennial parades. According to Barbara Tenenbaum, Porfirian ‘nationalist mythologizers’ used monuments and texts to justify Liberal policies and associate national heroes with Liberal presidents. For example, the Cuauhtemoc Glorieta, completed in 1887, depicts the martyred Aztec ruler as a national hero and political ancestor to Miguel Hidalgo and Porfirio Díaz, who all seem linked as essential contributors to the formation of modern Mexico.Footnote 31

Besides parades, Centennial events included public ceremonies that sometimes attracted over 100,000 persons. Such occasions required an expanse suitable for large-scale creative imagery and the Zócalo provided the perfect setting. As the heart of the ancient capital, it had accommodated elaborate ceremonies since Aztec times, and impressive buildings representing political and religious authority ringed the square's spacious interior. The national Cathedral, seat of ecclesiastical authority since the sixteenth century, faced the national and municipal palaces, seats of secular authority where Liberal politicians sometimes crafted anti-clerical policies.Footnote 32

The Zócalo also represented the confluence of rich and poor in Porfirian Mexico. Government officials worked in the palaces and offices that looked out onto the square, and the devout among them attended Sunday mass in the Cathedral. They shared the plaza, however, with an increasingly complex mix of vendors, artisans, beggars and thieves, who lived within blocks of the Zócalo in tenements and flophouses owned by the elite.Footnote 33 Further east of the square, tens of thousands of recently arrived peasants, many forced from their land by hacienda expansion and population pressures, crowded into crude adobe structures thrown up on the city's edge. These structures lacked ventilation, potable water and proper sanitation, and unhealthy conditions resulted in deadly diseases and high mortality rates.Footnote 34

The proximity of tenements and slums to the Zócalo, and the accessibility of the Paseo de la Reforma via the tramway, made it easier for common people to attend Centennial events. Vendors would have also viewed spectators as potential customers, and petty thieves as potential victims.Footnote 35 This situation presented Centennial organisers with a dilemma. While they encouraged large turnouts in order to maximise the events' political and cultural messages, problems of social control could also result from overcrowding, petty thieves and aggressive vendors.

On a more general level, Porfirian elites lamented the negative image created by Mexico City's underclass, particularly in the eyes of the foreign visitors whom they wanted to impress. Beginning in 1897, police had begun to detain the urban poor and imprison them at a rate of 10,000 per year. However, for every suspicious person hidden from public view a replacement arrived from the countryside. As the Centennial approached, city officials required indigenous men to exchange cotton wraps for trousers, sombreros for felt hats, and sandals for shoes. Similar attempts to alter native fashion occurred in the provinces, and everywhere they proved unenforceable.Footnote 36

Visitors to Mexico City, therefore, saw modern architecture juxtaposed with tenements and slums, and Europeanised elites sharing space with recently arrived peasants who spoke more Nahuatl than Spanish. For some travellers, this mix of modern and traditional might have been part of Mexico's attraction, or at least its distinctiveness. But Mexican elites assumed that visiting dignitaries shared their traditional prejudices about race and culture, views reinforced by their reading of Social Darwinism and positivism.

The organisers had prepared for foreign delegations, but had done little in anticipation of the arrival of large numbers of ordinary visitors arriving from the provinces and the United States. Such turnouts might have been expected because of the uniqueness of the Centennial and the existence of a network of railways, largely built during the Porfiriato, which linked the capital with the US border and the intervening provinces. However, the stream of visitors arriving for the celebration strained the capabilities of local hoteliers and merchants, as described by Frederick Starr:

Throughout the month all trains reached the city loaded with passengers. Thousands of young fellows born from mixed parents in the United States, many of whom had never seen the country of their fathers before, came to visit the land where one or the other parent was born. Crowds of citizens from the outlying states, who had never seen the capital, made their first trip to the great city, many times taking their first journey on a railroad train. The hotels were crowded, and no rooms were empty; crowds were turned away without a place to sleep; the price of lodging was doubled, trebled; rooms in private houses were held at staggering rates; prices of restaurants soared upward; cocheros considered every day a festival and collected double fares accordingly.Footnote 37

Foreign delegates and other visiting dignitaries escaped many of these inconveniences because they had been placed in the best hotels or in the mansions of elites. The arrival of delegates from the United States, Europe, Asia and Latin America, indicated Mexico's growing importance in the global community. Among larger Western European nations, only Britain declined to send a delegation, citing official mourning over the recent death of Edward VII. Nevertheless, Mexico City's British community still participated in the festivities and praised President Díaz for his many accomplishments.Footnote 38

Spain and the United States sent particularly large delegations, indicative of the significance both nations attached to the occasion. Special Ambassador Curtis Guild, Jr., the former governor of Massachusetts, led the US contingent and shared the limelight with Henry Lane Wilson, US Ambassador to Mexico. Both officials praised President Díaz in public ceremonies, Guild calling him ‘the greatest living American’.Footnote 39 The head of the Spanish delegation, the Marques de Polavieja, appeared well chosen for the job. According to Genaro García, the Centenario's official chronicler, Polavieja's Mexican mother and military background gave him special kinship with General Díaz. In two showpieces of the Centennial, Polavieja would present Díaz with the Order of Carlos III and the uniform of José María Morelos, confiscated by Spanish officers after the capture and execution of Morelos.Footnote 40

Delegates and their entourages attended major Centennial events and social occasions, such as balls, banquets and garden parties, which were closed to the public. Elites and members of foreign colonies in Mexico City coveted invitations to these affairs, and local businesses advertised special promotions for the Centenario. Advertisements in the Mexican Herald referred to the ‘Centenario Season’, and the department store ‘La Ciudad de Londres’ offered a special selection of clothing as well as perfumes, soaps and powders chosen by their ‘French artist designer’ to create a ‘true Paris effect’.Footnote 41

Official history in parades and processions

Parades presented an official version of Mexican history designed to promote Mexican Liberalism and to buttress the regime. In form and scale, they resembled colonial festivals organised by the Crown to communicate cultural and political messages that facilitated social control.Footnote 42 Guillermo de Landa y Escandón and José Casaín fashioned a ‘Desfile Histórico’ as a three-act representation of Mexican history. Their choice of subject matter emphasised the conquest, the colonisation of the Native Americans, and the liberation of the colony from Spanish rule. The Desfile depicted the meeting between Hernán Cortés and Moctezuma outside Tenochtitlán; the Paseo del Pendón, the Spanish ceremony that commemorated the conquest; and the entry into Mexico City of the Ejército Trigarante.Footnote 43

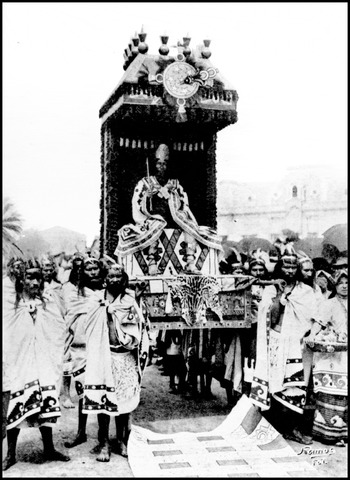

In Act One, 809 elaborately costumed individuals representing conquistadors and Aztecs began their march at the Plaza de la Reforma and continued down the Avenidas Juárez and San Francisco until they reached the Zócalo, where they re-enacted the historic encounter. Moctezuma's entourage included lords from the valley's principal city-states, priests, warriors and servants, all dressed in period costume and weaponry. Moctezuma himself was carried in an ornate litter (see Figure 1, p. 516). The conquistadors, also appropriately attired, followed closely. Cortés and his captains led an invading army consisting of cavalry, infantry, crossbowmen, musketeers, Tlaxcalan warriors, Catholic priests, native servants and Doña Marina, Cortés' Indian mistress and interpreter. A drum and bugle corps also contributed to the ambience.Footnote 44

In Act Two, the Paseo del Pendón procession recreated a colonial ceremony, without its religious trappings, that celebrated the Spanish conquest of the Native Americans. The parade consisted of several hundred participants dressed as colonial officials of varying ranks as well as Indian officers representing Santiago and Tlaltelolco districts. Men dressed in powdered wigs and eighteenth-century formal wear marched from the San Hipólito temple, down San Francisco, and into the Zócalo where they halted at an elaborate platform decorated with colourful banners emblematic of royal sovereignty. A colonial official presented the banner symbolising Spanish domination over the natives to the Viceroy, who deposited it in the municipal palace.Footnote 45

In Act Three, Agustín de Iturbide led the victorious ‘Army of the Three Guarantees’ into the Zócalo. Individuals representing Independence-era generals Vicente Guerrero, Guadalupe Victoria, Manuel Mier y Terán and Anastasio Bustamante, led regiments from the Plaza de la Reforma into the Zócalo. The procession also included allegorical carriages dedicated to Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla and José María Morelos y Pavón, as well as floats commemorating the battle of Cuautla, and Tabasco and Sinaloa states.Footnote 46

El Diario estimated that 200,000 persons witnessed the Desfile Histórico.Footnote 47 Photographs and newspaper accounts indicate that organisers attempted to dress historical figures, Spaniards and natives alike, appropriately and with dignity. Nevertheless, the events and cast of characters selected to represent major historical periods conveyed a Liberal interpretation of Mexican history. For example, apart from the priests who marched in Cortés' entourage, the Church received no special recognition for its pivotal role in Mexican history, which reflected the Liberals' anti-clericalism. Moreover, the Paseo del Pendón, chosen to represent the entire colonial era, recreated a civic ceremony without religious content that emphasised the conquest and subservience of Native Americans to the state. The selection of this ceremony shows Liberals' bias against Indians, as demonstrated in policies such as the Ley Lerdo, the privatisation of public lands, and forced military service (La Leva).Footnote 48

Under these circumstances, some Native Americans refused to participate in the Desfile Histórico. José Casarín sent agents to Oaxaca, San Luis Potosí, Tlaxcala, Morelos, Chiapas, and the National Penitentiary, searching for Indians to march in the parade. He also wrote to the governor of Tlaxcala, Próspero Cahuantzi, requesting 110 natives for Cortés' entourage; and to Governor Manuel Sánchez de Rivera of San Luis Potosí, asking for 250 natives, including 20 local women ‘renowned for their natural beauty’.Footnote 49 In San Luis Potosí, however, Indians rejected the request to participate as a ruse to trick them into military service, and General Sánchez de Rivera had to ‘convince’ them to march in the Desfile Histórico.Footnote 50

The centennial planners' quest for authenticity also compelled them to recruit Spaniards or Spanish-looking Mexicans to portray royal officials in the parade.Footnote 51 This proved easier, however, than integrating Agustín de Iturbide, the Creole pro-Church monarchist, into the liberal interpretation of Mexican independence. Despite Iturbide's pivotal role in achieving victory, the Centennial planners initially refused to include him in the final act of the Desfile Histórico, which provoked pointed criticism from centres of conservatism. The Catholic newspaper, El Tiempo, got right to the point when it editorialised that the organisers' ‘preoccupations with sectarianism’ would cause the public to forget the ‘hero Agustín de Iturbide’. Pressure from Mexico City's City Council, a lingering bastion of Spanish influence, finally convinced the Centennial Commission to include Iturbide in the Desfile Histórico.Footnote 52 The conservatives' ability to alter the parade demonstrates one area where they could still influence public policy, despite a thirty-year absence from the presidency.

Beyond the controversies provoked by historical revisionism, the Desfile Histórico presented municipal authorities with problems in crowd control. People seeking to view the Desfile began assembling at first light along the downtown streets that led into the Zócalo. As the crowd swelled to 200,000 persons, the double row of soldiers wedged in between viewers and the street proved unable to maintain order. At that juncture, a contingent of mounted police arrived and ‘with pitiless cruelty’, in the words of an eyewitness, rode their horses into the crowd, causing widespread panic especially among women and children. Fleeing spectators damaged government offices, destroyed furniture, and ended up in jail. In the meantime, persons representing Hernán Cortés, Moctezuma, the Viceroy and other marchers took shelter wherever they could. Two days later, in an address to Congress, President Díaz blamed the disturbance on ‘popular violence’, while El Diario focused its criticism on inadequate planning by organisers.Footnote 53

Fig. 1. Native Americans were recruited and costumed to represent Montezuma and his entourage for the Desfile Histórico. Photograph courtesy of the Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico City.

Fig. 2. As the Desfile Histórico entered narrow downtown streets, crowds of spectators and allegorical carriages competed for space. Photograph courtesy of the Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico City.

Fig. 3. Spectators observed the Desfile Histórico from various vantage points, including sidewalks, balconies, and windows. Photograph courtesy of the Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico City.

Following the Desfile Histórico, a parade of allegorical carriages presented images representing the regime's achievements. Expensively decorated oxen-driven floats underscored Mexico's material progress, President Díaz's historical association with independence leaders, and references to France meant to suggest cultural and historical associations. The parade featured carriages dedicated to the themes of commerce, industry, agriculture, mining and banking, as well as floats by cigarette manufacturer ‘El Buen Tono’, the department store ‘El Palacio de Hierro’, and the cognac ‘Gautier’. The carriages formed at the Plaza de la Reforma and paraded down familiar downtown streets until they reached the Plaza de la Constitución.Footnote 54 Rowdy behaviour by large crowds caused delays, forcing oxen to take an hour to walk a block in some areas, but no major disturbances occurred.Footnote 55

The ‘Centro Mercantil’ carriage combined major Centennial themes.Footnote 56 Decorations included a display of Mexican and French national flags emblematic of local French mercantile influence, busts of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla representing ‘La Patria’, Benito Juárez symbolising ‘Justice’, and Porfirio Díaz ‘Peace’. Two teams of horses handled by four grooms dressed in Louis XV period costume associated Mexico with Old Regime France.

Continuing with the French theme, the ‘Gautier’ carriage presented a tavern scene of French peasants and musketeers. The float also included a beautiful display of flowers from Xochimilco, later placed before the urn containing the remains of independence heroes in the national Cathedral. The ‘Buen Tono’ float also showed French cultural inspiration by depicting a scene of ‘beautifully dressed’ French courtesans from the era of Louis XV.

The material progress of the Porfiriato dominated the themes of most remaining carriages. The float representing industry included tributes to ‘science, work, precision and force’, encapsulating the científicos' ‘Order and Progress’ motto, itself patterned after Comte's positivist writings. The float saluting the mining industry was accompanied by a contingent of troops, perhaps celebrating their contributions as strike breakers, as well as two elaborately costumed women representing ‘Gold’ and ‘Silver’, as if they were pagan goddesses. A contingent of miners with their tools held erect also accompanied the carriage, like foot soldiers of material progress. The banks' float presented a ‘cornucopia of treasure’ display, apparently unconcerned with appearances of excessive profiteering, while the agricultural carriage contained products from several regions attended by colourfully dressed local farmers.Footnote 57

Overall, the parade celebrated the business community's success and the regime's commitment to material progress, both of which served as encouragement to foreign investors. The Old Regime France motif favoured by several businesses reminded viewers of Mexico's historical kinship with Bourbon France, associated high-end products with French culture and good taste, and acknowledged French mercantile influence.

Ceremonies as historical and cultural lessons

Parades provided dramatic visual presentations that conveyed ideological and promotional messages. But the Centennial also included traditional ceremonies associated with Independence Day, notably the Grito, which could be linked by organisers with the achievements of Porfirio Díaz. Special attention was also given to reconciliation between Mexico and Spain, with Spaniards taking the initiative by returning the uniform of Morelos and presenting Díaz with a highly prestigious honour. Centennial organisers, in turn, used Morelos' uniform to promote the fallen leader as a mestizo icon of Mexican national identity. Elites thus came to terms, at least rhetorically and symbolically, with Mexico's racial and cultural evolution as a ‘mestizo nation’. Although this remained a work in progress, it demonstrated awareness that fashioning a national culture required inclusion of Mexico's hybrid masses, a viewpoint later embraced by revolutionary ideologues inspired by José Vasconcelos' invention of mestizos as a ‘cosmic race’ possessed with unique physical and intellectual properties.Footnote 58

Despite Spain's recognition of Mexican independence decades earlier, popular antipathy toward Spaniards remained. Many Mexicans regarded Spaniards as arrogant and money-grubbing, the popular stereotype of the gachupín, a viewpoint likely reinforced by the success of Spanish merchants, bankers and textile producers during the Porfiriato.Footnote 59 As the Grito approached, a Catholic newspaper feared that Mexico City's popular classes, ‘after drinking copious quantities of pulque’, would celebrate the occasion by ‘attacking mother Spain and our Spanish brothers’.Footnote 60 This fear proved well grounded. In Tampico, on 14 September, an angry mob attacked the houses of Spaniards as well as the Spanish Consulate, and pulled down Spanish flags and bunting displayed to commemorate the Centenario. Mounted police and the army dispersed the crowd, bayoneted rioters, and imprisoned 38 suspects. Although local elites formally apologised to the Spanish community, the episode tainted the celebration and reflected anti-Spanish sentiments among non-elites.Footnote 61

From Spain's perspective, the Centenario presented an opportunity to improve its relations with Mexico by honouring Porfirio Díaz. With considerable pomp and circumstance, the Marquis de Polavieja presented Díaz with the Real y Distinguida Orden de Carlos III, the highest honour that Spain could bestow on a foreign dignitary. The ‘Collar’ could be held by only one person at a time and the recent death of the previous holder, Edward VII of Britain, made possible its passing to Mexico's dictator. In his acceptance speech, Díaz praised the reforms of Carlos III as enlightened administration.Footnote 62

The Spanish community in Mexico, recognising the opportunity to heal old wounds, had also suggested the return of Morelos' uniform to Mexico. The grateful Mexican government granted the uniform the equivalent of a state funeral. Like a body in a funeral procession, the uniform rested in an ornate carriage accompanied by a large contingent of soldiers. At the head of the procession, an honour guard carried an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Mexico's Indian patron saint and symbol of the Hidalgo rebellion. The procession made its way from the Spanish Embassy to the National Palace, where President Díaz hosted a celebration that included ringing the Cathedral bells, performances by military bands, and a solemn hoisting of the flag that reportedly left everyone in tears.Footnote 63 In his speech, the president praised Morelos as Mexico's ‘greatest hero’ and ‘most famous man’. The opportunity to hold the fallen leader's uniform in his hands, the General continued, constituted ‘the most satisfying event of my life’.Footnote 64

Morelos received similar praise from other dignitaries, who also commented on the importance of the hero's mestizo heritage. For example, Génaro García, the official chronicler of the Centenario, wrote that ‘Morelos is the legendary figure par excellence. He is also the mestizo who symbolises the new race with all the greatness of the others, and, for this reason, Morelos is the genuine representative of Mexican nationality’.Footnote 65 In major addresses, Isidro Fabela, the intellectual-politician and future revolutionary, praised Morelos as the greatest independence era leader and ‘the genius of our race’, while Foreign Minister Enrique Creel and Education Minister Justo Sierra compared Morelos to Napoleon, while giving only scant attention to the Creole leader Iturbide.Footnote 66

The Liberal elite's promotion of Morelos can be viewed as part of a strategy to fashion an inclusive national culture centred on secular heroes, as opposed to celebration of Catholic saints and holidays. Despite the fact that he had been a priest, Morelos' excommunication by ecclesiastical authorities and execution by the Crown made him an effective symbol of Liberal anti-Church and anti-monarchist convictions. If the Virgin of Guadalupe could be the national patron saint, a position supported by the Díaz government, then Morelos could be a mestizo national hero.

The inclusion of mestizos in the Liberal's structuring of national identity turned on practical considerations. Justo Sierra and other elites had largely given up on Indians as productive citizens, and they viewed mestizos as useful replacements in the work place. For the científicos, the Indians' ignorance and religiosity had retarded Mexico's development and modernity. Sierra's praise of mestizo ‘virility’ stemmed from racist assumptions and materialist objectives. For example, he wrote that ‘We need to attract immigrants from Europe so as to obtain a cross with the indigenous race … for only European blood can keep the level of civilisation that has produced our nationality from sinking, which would mean regression, not evolution.’Footnote 67 Antonio García Cubas, a prominent geographer and intellectual, viewed Mexico's natural socio-racial order as Euro-Mexicans running government and business, mestizos working in the factories and fields, and urban Indians wallowing in degeneration.Footnote 68 Even Porfirio Díaz, himself a mestizo with dark Indian features, felt uncomfortable with his physical appearance and sprinkled powder on his face to appear whiter.Footnote 69 For Porfirian elites, France stood at the pinnacle of Western civilisation, and in fashion and ceremony they emulated French designs and symbols to achieve high culture and gain the approval of Europeans.Footnote 70 The Centenario provided an ideal occasion for promoting Liberal constructions of nationalism and secular heroes. The traditional Grito celebration, commemorating Miguel Hidalgo's call to rebellion, featured a patriotic presidential speech at midnight in a party-like atmosphere in the Zócalo. Since the Grito coincided with Díaz's birthday, organisers used the event to link Hidalgo the liberator with Díaz the peacemaker, a lesson that resonated with the foreign press. For example, the New York Times' correspondent wrote:

Mexico's celebration of the 100th anniversary of martyred Father Hidalgo's proclamation of independence has been coupled with an equally impressive celebration of the eightieth anniversary of the birth of that wonderful old man, Porfirio Díaz. Who can doubt that the supposedly lesser includes the seemingly greater? Mexico's centennial of independence is unquestionably another manifestation of the power of the president.Footnote 71

In preparation for the Grito, organisers decorated the downtown area with a display of patriotic symbols in national colours, including neon signs on the cathedral reading ‘1810 Libertad’ and ‘1910 Progreso’Footnote 72 which graphically linked the independence and Porfirian eras and symbolised the Church's subservience to the Liberal state. In effect, the national centre of ecclesiastical authority and prestige had been reduced to a billboard for a secular celebration.

Despite rain and cold weather, an estimated 100,000 persons crowded into the Zócalo and watched the fireworks that preceded Díaz's speech.Footnote 73 Likely fortified by pulque and vendor food, celebrants might have glanced upward and noticed elites and diplomats enjoying a fine dinner on the presidential balcony above. Suddenly, gunshots rang out. A throng of demonstrators, pushing their way through the thick wall of people to the base of the National Palace, hoisted a large portrait of Francisco Madero and shouted maderista slogans. Federico Gamboa, the Sub-Secretary of Foreign Relations, calmed the alarmed German Ambassador Karl Bunz by ‘suavely lying’ that it was a pro-Díaz demonstration.Footnote 74

Frederick Starr witnessed another maderista demonstration that disrupted the Centenario. Near the Columbus glorieta along the Paseo de la Reforma a large group representing Anti-Re-Electionist organisations had gathered with banners that announced their names (‘The Daughters of Cuauhtemoc’ and ‘The Benito Juárez Anti-Re-electionist League’, for example). Starr observed that the maderistas appeared to be ‘common people’ led by professional-looking men in suits. Their orderly, even dignified, protest was violently attacked by the chief of the mounted police, Castro, who ordered his cavalry with swords drawn into the crowd again and again, only to see the maderistas re-assemble in orderly fashion, similar to the tactics employed by non-violent civil rights demonstrators in India and the United States. Finally, police on foot encircled the maderistas and forced them to disband. Many of the suspected leaders, presumably those in the suits, were arrested and taken to the notorious Belém prison.Footnote 75 Such bravery in the face of police violence suggested troubles ahead for the regime.

Educating the people

The Porfirian state's model for stability and modernity combined political repression with social and institutional reforms, including public education, secularisation and the scientific treatment of criminals and the mentally ill. The Centennial provided an ideal opportunity for the regime to showcase these programmes before its citizens and an international audience. Ceremonies featured groundbreaking for a new penitentiary, the opening of a modern asylum for the insane, and the celebration of new schools and educational congresses.

For Liberals, public schools served as vehicles for national integration through scientific learning and formation of a civic culture. President Díaz, in his famous interview with the US journalist, James Creelman, in 1908, stated:

I want to see education throughout the Republic carried on by the national Government. I hope to see it before I die. It is important that all citizens of a republic should receive the same training, so that their ideals and methods may be harmonized and the national identity intensified. When men read alike they are more likely to act alike.Footnote 76

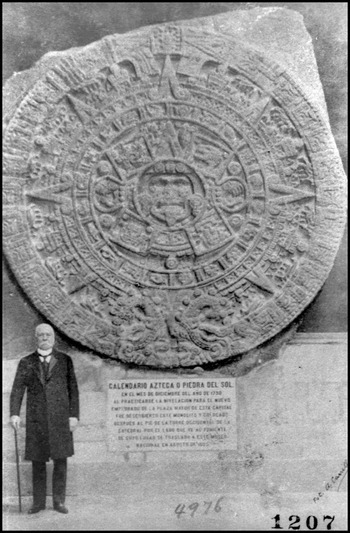

The importance of public education is shown by the stature of the dignitaries who hosted school openings and educational congresses during the Centenario. For example, the president himself officiated at the opening of a new normal school for primary school teachers, and Justo Sierra hosted government-sponsored educational congresses, including the Primer Congreso Nacional de Estudiantes, the Primer Congreso Nacional de Educación Primaria, and the Congreso Internacional de Americanistas. The latter event included a tour of the recently reconstructed Teotihuacán, and speeches by eminent anthropologists Edward Seler and Franz Boaz.Footnote 77 Following the Congress, Boaz remained in Mexico to become the first director of the government-sponsored International School of Anthropology.Footnote 78 President Díaz also hosted the opening of the newly remodelled Museo Nacional de Arqueologia, Historia y Etnologia, which featured a beautifully carved Aztec sacrificial altar, incorrectly identified by archaeologists as the ‘Aztec Calendar’, (see Figure 4), as well as a massive stone sculpture of the Aztec Water God. This exhibit also featured several contemporary Indians dressed in ancient Aztec attire. The inauguration of a new national university, which replaced the sixteenth-century institution founded by the Catholic Church, drew prominent scholars from major universities in Europe and the United States. Among those receiving honorary degrees were Theodore Roosevelt, Andrew Carnegie, and the prominent científico, José Y. Limantour.Footnote 79

Fig. 4. President Díaz posed before the Aztec sacrificial stone incorrectly identified as the Aztec calendar. Such displays drew attention to Mexico's glorious Pre-Columbian heritage. Photograph courtesy of the Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico City.

Academic papers, museum displays and reconstructed archaeological sites reflected elites' ambivalence toward Mexico's native sons. Cultures that could build Teotihuacán or carve elaborate stone sculptures demonstrated impressive engineering and artistic skills worthy of universal admiration and investigation. By drawing attention to these achievements, Porfirian elites wanted observers to connect ancient greatness with contemporary Mexico, without associating Pre-Columbian natives with contemporary Indians. Beyond displaying Indian models in Aztec costumes as living manikins (or as historical props in the Desfile Histórico), the Centenario organisers attempted to hide them.Footnote 80

This disassociation of ancient and contemporary indigenous cultures had parallels in other parts of the world. As Benedict Anderson has observed, colonial regimes in Southeast Asia systematically disconnected ancient cultures responsible for building impressive cities and shrines from their poverty-stricken descendants. For example, in Indonesia the Dutch argued that ancient and contemporary natives belonged to different races, and in Burma the British claimed that natives had suffered a profound secular decadence that rendered them incapable of replicating their ancestors' achievements. Reconstructed archaeological sites also constantly reminded impoverished natives living in the vicinity of their incapacity for greatness or even self-determination. In effect, colonial states (or former colonies like Mexico) appropriated indigenous cultural achievements of timeless value for their own political purposes.Footnote 81

In Mexico eminent scholars and political leaders alike succumbed to racist assumptions and pseudo-scientific explanations to explain contemporary natives' social degradation and poverty. For example, at the Americanistas meeting in Mexico City, anthropologists concluded that Indians were racially inferior based on their skull and bone structure. Jesús Díaz de León, a member of the Sociedad Indianista Mexicana, presented a more optimistic view. He saw Mexico's indigenous as engaging in a contest of survival of the fittest, with the Aztecs having ‘converted others into food for their nutritional needs’. In the end, the most biologically fit would survive and participate in Mexico's development. Justo Sierra, for his part, returned to the solution of mestizaje.Footnote 82

Apart from race mixture, Porfirians concluded that any hope for the Indian rested in secular education. A scientific education would strip natives of their religious superstitions and fashion patriotic citizens appreciative of secular heroes, such as Morelos, Juárez and Díaz. The new normal school and national university that opened during the Centenario symbolised the regime's commitment to public education at all levels of instruction. The process of transforming Indians and mestizos into acculturated citizens through public education, however, remained a work in progress. Despite significant increases in education budgets, especially at the provincial level, national literacy rates improved only modestly from 14.4 per cent to 19.7 per cent between 1895 and 1910. In Mexico City, the nation's cultural and academic centre, literacy rates stood at an estimated 45 per cent in 1900.Footnote 83

During this period, many countries struggled to overcome widespread illiteracy and to forge national identities. As Eugen Weber has shown, French villagers lived in isolation and ignorance. The process of turning peasants into Frenchmen required public education, industrialisation, internal migration, and ultimately participation in the First World War.Footnote 84 The process of turning peasants into Mexicans required similar steps that accelerated during the Porfiriato and continued after the Revolution of 1910.

The Centenario, Génaro García proudly wrote, did not cater exclusively to ‘upper class’ concerns but included many acts of ‘public charity’. His most prominent example was the new asylum, the Manicomio General, opened with great fanfare by President Díaz in Mixcoac, outside Mexico City. The new facility, built by the president's son Porfirio Díaz, Jr., for over 2,000,000 pesos, replaced two colonial institutions founded by the Catholic Church in 1576 and 1700. The asylum complex consisted of twenty-four buildings and two pavilions that included doctors' offices (including separate gynaecological examination rooms), mortuary, dissection chamber, living quarters for staff, kitchen, cafeteria, laundry, workshops and stables. Patients were segregated by illness and sex. According to García, this new facility placed Mexico in the forefront of mental health treatment among the most advanced nations.Footnote 85

However commendable the Manicomio may have been, it is instructive that García considered it an act of charity, rather than a social service expected from a modern, secular state. From the regime's perspective, this new state-sponsored charitable enterprise would ideally foster paternalistic ties between the state and the masses, supposedly at the expense of the Catholic Church. García's characterisation of mental illness as a lower-class problem also mirrors elite prejudices' concerning the inherent shortcomings of Indians and poor mestizos. Mentally troubled elites (and they must have existed) could consult psychiatrists whose services lay beyond the financial reach or knowledge of others, or they could possibly withdraw from public view under the protection of family members.

Patriotic symbols

Institutional improvements unveiled during the Centenario promoted modernisation and a new civic culture, which also resonated in patriotic ceremonies, monuments of heroes and historic events, and eye-catching political symbols. One ceremony featured Father Hidalgo's baptismal font, described by Frederick Starr as notably ugly and artistically ordinary. The font arrived from Cuitzeo, destined for display in the National History and Ethnology Museum, and planners arranged for a special procession from the train station to a final resting place. They added sentimentality and scope to the font's journey, moreover, by arranging for the presence of Hidalgo's granddaughter, Guadalupe Hidalgo y Costilla, as well as 30,000 schoolchildren.Footnote 86 By associating the priest with his progeny, real and symbolic, organisers gave the event an endearing, familial character. Catholics, however, may have been unsettled by the visual results of Father Hidalgo's failed celibacy.

Children also appeared as key participants in a large-scale patriotic ceremony based on pledging allegiance to the flag, with overtones of pledging allegiance to the national dictator. Organised as a special flag day, approximately 40,000 children assembled at 11 parks and plazas throughout the city and saluted the flag in special ceremonies. The largest group, numbering 6,000, gathered in the Zócalo with President Díaz presiding. Frederick Starr left us this description.

The greatest interest of course was at the central plaza of the city, where the celebration was witnessed by President Diaz and the members of his cabinet. When they appeared upon the balcony of the national palace, they were greeted with cheers and the waving of thousands of national flags. After some music, hundreds of the smallest children, with a little flag in one hand and a bouquet of flowers in the other, advanced to the great flag which had been raised and deposited their flowers. After that, the thousands of other children advanced in orderly groups and, passing beneath the national emblem, repeated the vow of allegiance to the flag, and sang the Song to the Banner which had been written for the occasion. After all had saluted the flag, the army of children sang the national hymn, all kneeling at the passage where the national land is invoked, and remaining in a kneeling position to the close of the stanza. When they arose, they waved their flags to the President with enthusiastic vivas, while the bells of the cathedral pealed.Footnote 87

The ceremony created the image of patriotic devotion by kneeling children simultaneously saluting the patria and President Díaz to the endorsement of cathedral bells.

Artifacts representing independence and nationalism could range in size from commemorative stamps to massive marble monuments. A notable stamp juxtaposed a portrait of Hidalgo labelled ‘1810 Libertad’ with a portrait of Díaz labelled ‘1910 Paz’, thus creating an historical association between the man who started independence and the one who stabilised it (see Figure 5). Although small in size, stamps, posters, and other portable devices effectively conveyed political messages sometimes lost in elaborately designed monuments or buildings intended for the same purpose. For example, at the opposite end of the visual scale, Centennial organisers erected an independence monument in a glorieta along the Paseo de la Reforma. Antonio Rivas Mercado, a French-trained architect, designed a rectangular base adorned with bronze statues that featured a boy leading a lion, representing ‘the people, strong in war and docile in peace’, and four seated women, representing Peace, Law, Justice and War. Additional bronze statues honoured independence heroes Morelos, Guerrero, Bravo and Hidalgo, with the latter in the centre position holding a flag.Footnote 88 The monument's defining characteristic, however, consisted of a towering column capped by a statue of a bare-breasted, winged woman partially clothed in Grecian robes. She represented ‘Winged Victory’, a symbol of republican liberty widely recognised in Europe.Footnote 89 For Mexicans, however, the statue looked like an angel, and the monument has been known ever since as ‘The Angel’.Footnote 90

Fig. 5. A commemorative stamp issued for the 1910 Centennial links Hidalgo the liberator with Díaz the peacemaker. Photograph courtesy of the Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico City.

Centennial organisers also marked the occasion by unveiling a monument unmistakably dedicated to Benito Juárez, the principal architect of La Reforma. Located astride the Avenida Juárez bordering the Alameda, the marble structure featured Juárez seated on a throne, fitted with a gardenia crown and attended by two allegoric women representing Glory and Mexico. According to John Hubert Cornyn, writing for the Mexican Herald, the Doric monument represented Juárez as ‘strong,’ ‘unadorned’, ‘severe’ and as ‘pure’ as the white Italian marble itself.Footnote 91 Constructed at a cost of 390,685 pesos, the structure also featured two bronze lions designed by Paris-trained sculptor Guillermo Cárdenas.Footnote 92

The inclusion of the Juárez monument in the Centenario linked the so-called ‘Benemérito de las Américas’, also known as the ‘Mexican Moses’, to his Liberal heir, Porfirio Díaz. Juárez's successful imposition of Liberal reforms, including widespread confiscation of Church property, created the secular framework for Díaz's ‘Order and Progress’ regime. Juárez, a full-blooded Zapotec Indian, also symbolised acculturation through secular education and rejection of Catholicism, positions which he advocated and personified. His presentation in pure, white marble represents the transformation of an Indian into the acculturated Mexican who symbolises modernity, secularism and liberalism.Footnote 93

Porfirians in the provinces also recognised the Centennial through a variety of construction projects. Officials unveiled new monuments, parks, libraries, schools, public lighting, telegraph and telephone lines, pavilions and municipal palaces. In the category of public buildings, Oaxaca, the birthplace of both Juárez and Díaz, led the way with 64 new facilities. Guerrero and Oaxaca, both predominately Indian provinces, opened 141 and 51 new schools, respectively, which far outpaced other states.Footnote 94 The city of Ciudad Juárez, across the border from El Paso, unveiled a statue of its namesake to the applause of 25,000 celebrants.Footnote 95 Throughout Mexico, the Centennial celebrated national unity, Liberal rule and material progress.

The Centennial also provided foreign nations with the opportunity to acknowledge their friendly relations with Mexico by donating statues of historic figures. For example, Kaiser Wilhelm presented Mexico with a statue of Alexander von Humboldt, and sent his nephew to Mexico to attend the unveiling. President Díaz himself hosted the event, and Frederick Starr left us with this eyewitness account:

The ceremony of the unveiling of the statue had been indefinitely announced to take place in the forenoon, and by 10 o'clock a crowd had gathered; by 11 the place was jammed; by 12 it was a surging and pushing mob – though a good-natured one. Probably not one in twenty of the crowd that stood there jostling in the hot sunshine knew or cared what was taking place. There was indeed some query as to why the monument? Who Humboldt was? Whether he was a Mexican? A general? When he was declared to be a German some wanted to know whether there was a difference between the Germans and the Gringos Americanos. It was with difficulty that the police now and then opened a passage for man or vehicle through the crowd. Occasionally a bola of ragamuffins formed, and by sheer weight-strength, for fun, forced its way through the struggling mass. When finally at noon the German Ambassador and a committee from the colony arrived with an escort of 200 marines from the German man-of-war, the crowd went into ecstasy, and a wave of vivas followed them. Other delegations arrived in coaches, then the cabinet, and last of all President Diaz heralded of course by the national hymn. The President was received at the door of the library building and conducted to the platform. The German chorus of male voices sang some selections, and after some preliminary speeches, the Ambassador made the formal address of presentation.Footnote 96

The president's decision to attend suggests the importance of harmonious Mexican-German relations to the regime. The reaction of the crowd, however, indicates that the occasion carried different meanings for dignitaries than it did for the audience. According to Starr, some of those in attendance could not have come to celebrate Humboldt or to applaud close ties with Germany, since they did not know of either the man or the country. Instead, they probably came out of curiosity to see important people, to listen to speeches, to enjoy the music, and to experience the moment. Vendors and petty thieves, who were likely in attendance, would have had more particular reasons for being there. In sum, the event held political significance for the Mexican and German politicians, who may have succeeded in educating the audience a little about Humboldt and Germany. But the majority of those in attendance seemed interested in simply having a good time.

Among foreign nations, the United States had the most at stake in Mexico in terms of geo-politics and investments by its companies and citizens. In his memoirs US Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson praised the Centennial celebration as the ‘crowning event’ of President Díaz's career. He mentioned the careful preparations, including the ‘large sums of money’ spent ‘in publicity and in securing the presence of notable and distinguished people’, and the fabulous balls, banquets and monuments.Footnote 97 Wilson himself had presided over the dedication of the monument to George Washington, with President Díaz, the cabinet, the diplomatic corps, and other foreign dignitaries in attendance. The Ambassador made no mention of the general public, however, which can be read as indifference to their viewpoint. It is with sincere sadness that Wilson lamented Díaz's denouement, expressing regret at the Mexicans' inability to appreciate their messiah.

The celebration closed with the impressive ceremony of the apotheosis, followed by a magnificent ball, over which the President and Mrs. Diaz presided with true monarchical dignity and ceremony. Diaz was crowned the saviour and ruler of Mexico, but even while the acclamations of vast throngs were reverberating through the palaces and streets of Mexico City, the hour of disaster was drawing nigh; the great structure which had been built up by the wisdom, sobriety and patriotism of one man had not been built strong enough to withstand the storms which presently broke forth; from the pinnacle which he had reached, Díaz fell to an abyss and with him fell his country.Footnote 98

Conclusion

Wilson's lament captures his genuine regret over Díaz's demise, as the ambassador demonstrated by conspiring in Francisco Madero's overthrow and the imposition of General Victoriano Huerta.Footnote 99 More broadly, Wilson's comments also reflect the attitude of most foreigners in Mexico towards the Díaz administration, whose policies had created a favourable business climate for overseas investors. For many of them, the Centennial's portrayal of Mexico as a land of economic opportunity reflected reality, an image not entirely sullied by the Revolution.Footnote 100

Besides heralding Mexico as a haven for investors, Centennial organisers used the occasion to promote secular heroes and liberalism through words and images. This reflected an international trend to use centenaries of historical events to shape political and cultural viewpoints, as witnessed by centennials of the French Revolution and US Independence. Such occasions also had the unintended consequence of providing public forums for expressions of opposing viewpoints.

In 1910, Centennial organisers portrayed Hidalgo, Morelos, Juárez and Díaz as linked together as creators of a modern Mexico committed to material progress, secularism, political stability, public education and science. These hallmarks of Liberal public policy were subsequently appropriated and re-packaged by the revolutionary state, which promoted revolutionary nationalism through public schools, state-sponsored festivals (including Independence Day and Revolution Day), separation of Church and state, and authoritarian rule.

In a defining moment of the Centennial celebration, organisers used the return of Morelos' uniform to portray him as a mestizo icon and symbol of national unity. Elites praised Morelos as the proto-typical national hero, gave his uniform the equivalent of a state funeral, and erected a statue of the mestizo general. Elevation of Morelos can be linked to Liberal elites' promotion of mestizos as replacements for Indians in the work force, a pragmatic strategy of cultural inclusion based largely on material need. The symbolic linkage of mestizaje with national identity laid the foundation for a revolutionary discourse, moreover, as represented by José Vasconcelos' promotion of mestizos as ‘la raza cósmica’ and Octavio Paz's musings about Mexicans' conflicted racial and cultural identity in The Labyrinth of Solitude.Footnote 101

The Centennial celebration also reflected many of the contradictions of the Porfiriato and Mexican liberalism. Events staged for mass consumption, such as the Desfile Histórico, had a popular character and attempted to construct historical memory among Mexicans from all social classes and ethnic groups. At the same time, however, organisers spent lavishly on banquets, receptions and balls, reserved exclusively for elites and foreign dignitaries.

The Centennial also revealed France's contradictory ideological and cultural influence on Mexico. The French Revolution had inspired independence-era rebels and republicanism, Auguste Comte's scientific materialism guided the Porfirians, and the Parisian training of Mexican sculptors found expression in monuments created for the Centenario. On the other hand, Liberal elites' aristocratic pretensions surfaced in their representations of Old Regime France in the Desfile Histórico, and Mexican Conservatives, much like their French counterparts, defended the Church against the current of secular revolution.

Spain's prominent role in the Centennial underscored divisions within Mexican society and politics. Both the Spanish government and Spaniards living in Mexico viewed the Centennial as an opportunity to achieve reconciliation with Mexico: as Spain awarded President Díaz the Order of Carlos III and returned Morelos' uniform. Both gestures were well received by Liberal elites, but anti-Spanish sentiment remained strong among non-elites and turned increasingly violent with the outbreak of the Revolution.

The Centennial also revealed Liberal elites' contradictory views of pre-Columbian cultures and contemporary Indians. The Centennial featured tours of Teotihuacán, the unveiling of Aztec artistic treasures, scholarly conferences on pre-Columbian culture, and a recreation of the historic encounter between Moctezuma and Cortés. At the same time, however, ordinances required Indians to exchange traditional dress for European-style clothing, city fathers removed natives from Mexico City's streets, legislation took away Indians' land, and the government encouraged acculturation through mestizaje.