This book insightfully brings together analytical and historical musicology to probe the meaning of allusory and variational processes in Brahms's music. It proposes that the way in which Brahms handles his allusions to the music of other composers can be understood as part of a multi-movement narrative that enacts his own struggles at establishing himself as the heir to the classical tradition. Thematic analyses of individual pieces detail the ways in which Brahms prefigures, transforms and abandons the allusory material and how these changes, along with shifts between the major and the minor modes, shape the narrative trajectory of the music. Insights into the compositional history of the works and Brahms's relationship to the music he references inform the interpretation of these allusions and the way they are handled. The analyses deal primarily with works from Brahms's formative period, a time when the composer's need to assert his place in the canon was most pressing. After a brief discussion of Brahms's First Symphony (op. 68), Horn Trio (op. 40) and Third String Quartet (op. 67), Chapter 1 turns to the First and Third Piano Sonatas (opp. 1 and 5). The book then continues chronologically through chapter-long analyses of the B major Trio (op. 8), the D major Serenade (op. 11) and the D minor Piano Concerto (op. 15), finally skipping to and culminating with an analysis of the Fourth Symphony (op. 98).

Sholes reads many of these pieces as narratives of self-liberation, where Brahms alludes to the music of Beethoven only to abandon or transform the allusory material later on, freeing himself from the shadow of his predecessor. Essential to this narrative is that the abandonment/transformation of the allusory material comes with a shift from the minor mode to the parallel major. In her analysis of Brahms's Symphony No. 1, op. 68, Sholes sees the composer's struggle to complete a symphony with an instrumental finale worthy of its Beethovenian precedents as the basic premise of the piece. She argues that this work alludes to Beethoven's Fifth and Ninth Symphonies through its major-to-minor tonal trajectory, the Ode-to-Joy-like theme of the Finale, and its short-short-short-long rhythmic figures reminiscent of Beethoven's Fate-Motive. Sholes associates the use of the short-short-short-long rhythmic figure with dissonance, restlessness and the minor mode, arguing that in the Finale the major mode starts to overcome the Fate-Motive until finally, in the closing bars, the Fate-Motive appears over a major tonic chord, cementing the triumph of major over minor and of Brahms over the genre he long struggled to master. Sholes is not alone in hearing this Symphony as enacting Brahms's struggle to break free from Beethoven. Missing is a reference to Reinhold Brinkmann's analysis of the Finale, which argues that Brahms effaces Beethoven's symphonic legacy by replacing in the recapitulation his Ode-to-Joy-like theme with the Alphorn theme.Footnote 1 Indeed, as Example 1 illustrates, the Alphorn theme may be heard as taking over the Ode-to-Joy-like theme (shown in a and b), the Fate-motive, and the minor mode.

Ex 1 Alphorn theme replaces Beethovenian allusions in Brahms's Symphony No. 1, op. 68, IV

In bars 267–278, just as the minor mode takes hold of the music, Brahms transforms the opening of his Ode-to-Joy-like theme into a repeating four-note figure that closely resembles Beethoven's Fate-Motive: the rhythm is nearly identical to that of Beethoven's Fate-Motive and the figure outlines a descending third, just as Beethoven's motive does. In bar 279, however, Brahms breaks free from the Fate-Motive, prefiguring the Alphorn theme that in bar 286 ends up replacing the Ode-to-Joy-like theme we would expect to find there. By forcefully freeing his music from the Ode-to-Joy-like theme and the minor-mode version of the Fate-Move, in bar 279 Brahms is able to break free from Beethoven's shadow. This reading complements Sholes's claim that Brahms's allusions to the Fate-Motive show the composer's effort to reckon with Beethoven's symphonic legacy and master the genre for himself.

Sholes reads Brahms's Piano Sonata No. 3, op. 5, along the same lines as the First Symphony. The analysis identifies several occurrences of the short-short-short-long rhythmic figure and claims that in the last movement, as the music modulates to the parallel major, this rhythmic figure is supplanted by a rhythmically even four-note figure. Much as in her analysis of the First Symphony, in her discussion of the Sonata Sholes argues that ‘Brahms's handling of this rhythm … plays out, even unintentionally, his own attempt at self-liberation from the confines of Beethoven's imposing “shadow”’ (p. 61). The connection between Brahms's F minor Piano Sonata and the Fate-Motive of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony is a bit tenuous, nonetheless, for many of the short-short-short-long rhythms that Sholes hears as transformations of Beethoven's Fate-Motive are actually drumroll figures of the type commonly found in late eighteenth-century music. As shown in Example 2, this figure always appears as an anacrusis typically with a semiquaver triplet leading to the downbeat either over a repeated tone or as part of an ascent that outlines, in most cases, a perfect fourth.Footnote 2

Ex 2 Drumroll figures

Example 2c shows Brahms's use of this drumroll figure at the beginning of the fourth movement of the Piano Sonata (this figure can also be found in the scherzo movement). Whereas Sholes argues that these figures may be heard as ‘nervous transformations’ of the Fate-Motive where the basic short-short-short-long rhythm has been sped up, I would argue that these figures style the music as a funeral march, giving the movement the sober, reflective tone suggested by its subtitle: ‘Rückblick’. Coming after a funeral march, the quiet turn to the major mode in the final movement sounds more like a moment of solace than a triumphant break-through. In sum, the short-short-short-long rhythmic figure in the third and fourth movements of the Sonata is too common of a gesture to be associated with Beethoven's music in particular, and so it is difficult to hear the disappearance of this rhythmic figure in the final movement as enacting Brahms's attempt to set himself free from Beethoven's imposing shadow, as Sholes proposes.

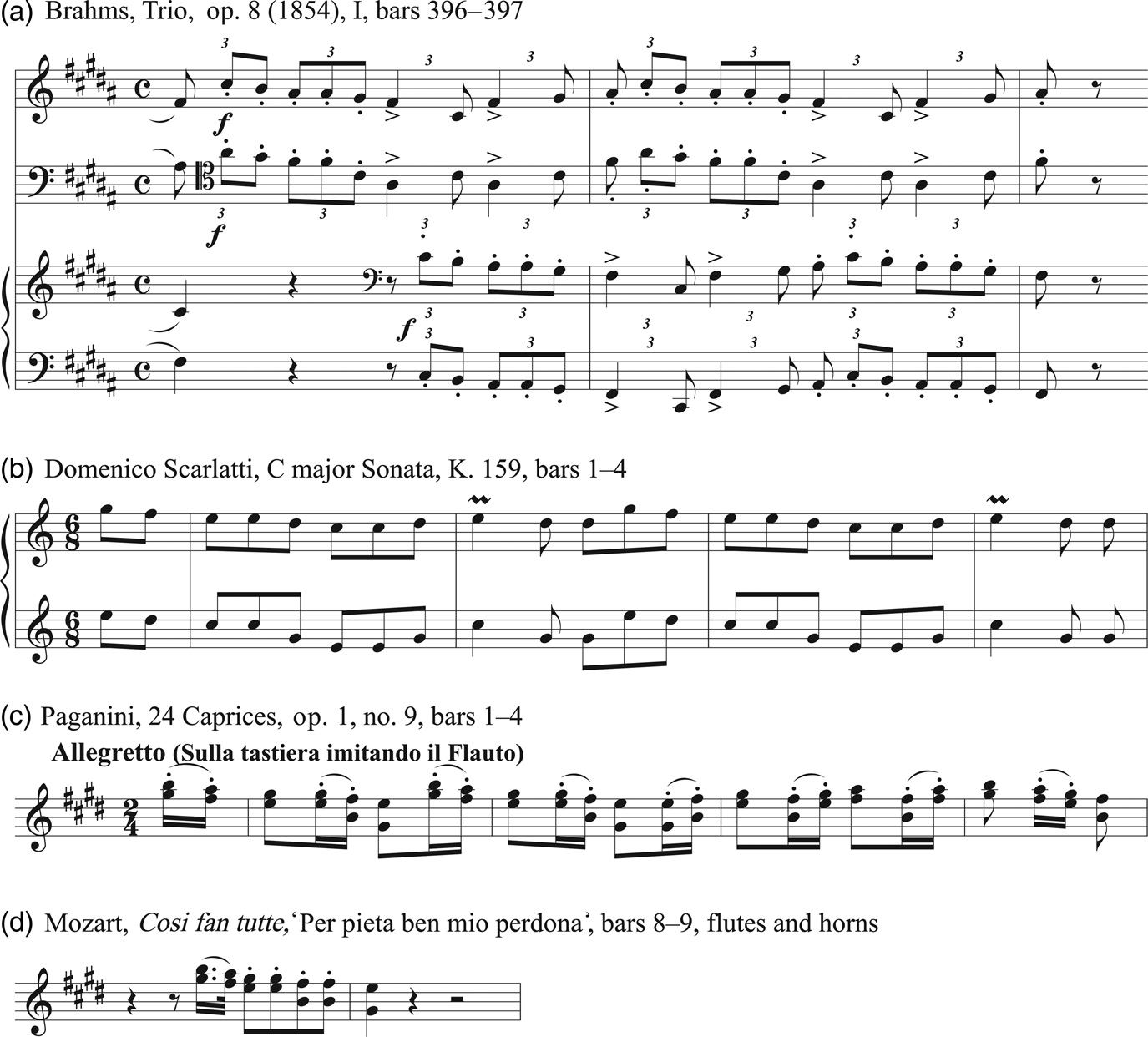

Sholes's analysis of Brahms's B major Piano Trio, op. 8 (1856) gives insight into Brahms's relationship to Domenico Scarlatti's music and of the changes that Brahms made when he revised this work later in his life. Sholes argues that the horn call in the first movement of Brahms's Trio alludes to the horn call found at the beginning of Scarlatti's C major Sonata, K. 159, and she observes that this allusion gradually disappears in the later movements. Since this piece features a major-to-minor tonal trajectory, Sholes hears the disappearance of the allusory material not as enacting Brahms's liberation from the past, but as a means through which Brahms mourns the passing away of the musical tradition that he saw himself a part of. As Example 3 shows, the similarities between the horn calls in Brahms's Trio and Scarlatti's Sonata are undeniable, but similar horn calls can be found in many other pieces, a couple of which are included in the example.

Ex 3 Horn call figures

Much like the drumroll rhythm in the F minor Piano Sonata, the horn call in Brahms's Trio is too schematic to point to any one particular piece, deriving its meaning instead from its topical associations, most significant among these is that of distance (an important topos of the Trio, as Sholes notes).

Although it is difficult to hear the horn call of Brahms's Trio as referring specifically to that of the Scarlatti Sonata, the thematic connections that Sholes draws in her analysis of this piece are quite suggestive. Her analysis shows the resemblance between the work's opening theme and the horn call, proposing that the former prefigures the appearance of the latter. The thematic connection is convincing, but it is difficult to hear the opening theme as prefiguring something that ‘sounds’ far away. Instead, the horn call may be heard as a transformation of the opening thematic idea, one where the theme sounds distant, its characteristic features fading into the schematic. Indeed, many of themes of the following movements derive more clearly from the opening melody (a melody that is ingrained into our memory by its sheer repetition), than from the fleeting horn call as Sholes suggests. As shown in Example 4, the opening melody of the second movement is nearly identical to the opening melody of the first movement. The opening melody of the third movement closely resembles the ending of the first movement's opening theme and shares with it the opening minim-crotchet-crotchet rhythm. Finally, Brahms's quotation of Beethoven's An die ferne Geliebte has the same melodic outline as the first theme of the Trio, except that in the quotation the melody leaps down rather than up to scale-degree 5 (note that the quotation is in the key of F-sharp instead of B major). To be sure, as Sholes points out, these themes bear resemblances to the horn call, but these resemblances are a product of the fact that the horn call is itself a variation of the opening theme. Overall, Sholes's view that the Trio conveys a sense of loss and that this sense of loss is closely related to the work's thematic transformations is convincing, but when the Beethoven quotation invites the listener to recall the melodies once sung, the quotation is more likely to be referring to the cantabile opening melody it resembles than the decidedly less lyrical horn call.

Ex 4 Thematic similarities among movements in Brahms's Trio, op. 8 (1854)

In direct contrast to the analysis of the Trio, which details the gradual dissolution of the horn call, the analysis of the D major Serenade, op. 11 elucidates the process of thematic recollection that leads us in the final movement to a varied return of the work's opening theme (the sort of return missing in the Trio). After showing the similarities between this theme and that of the Finale of Haydn's Symphony in D major, No. 104, Sholes proposes that ‘the effort to recall the first theme of the Serenade later in the work is perhaps more fundamentally an attempt to recapture the music of Haydn's Finale, which threatens to fade into the musical past’ (p. 128). This effort to recapture Haydn's Finale is seen in turn as a metaphor for Brahms's struggle to connect to the past and build upon it. Sholes's view of the Serenade as enacting an effort to recapture Haydn's music resonates with the Serenade's overt association with the pastoral, for the pastoral, as Raymond Monelle explains, is characterized by a ‘yearning for the Golden Age’, a Golden Age that in this case seems to be represented by the rustic simplicity of Haydn's Finale.Footnote 3

Sholes returns to the theme of Brahms's effort to break away from the shadow of Beethoven in her analysis of the D minor Piano Concerto, op. 15, a piece that Brahms struggled to complete. According to Sholes, the work itself embodies this struggle. Her argument is based on the similarities and differences between the final movements of Brahms's concerto and Beethoven's C minor Piano Concerto, op. 37. While a number of authors have pointed to the formal similarities between these two movements, Sholes observes that whereas Beethoven's Finale modulates from the minor mode to the parallel major during the recapitulation of the second theme, Brahms's Finale shifts from the minor mode to the parallel major at the end of the cadenza, marking the culmination of a multi-movement trajectory where the soloist has become ever more assertive, for while in the first movement the pianist enters with a quiet new melody rather than with the energetic opening theme of the orchestral exposition, in the finale the soloist's relationship with the orchestra is completely in accord with that expected of a rondo finale. As Sholes puts it, ‘in the last movement, as the soloist finally asserts himself and as Brahms breaks away from Beethoven's structural model, arriving on his own terms in the tonic major and embarking on an unconventional coda replete with victorious horn calls, Brahms appears to act out a triumphant establishment of self’ (p. 174).

While Sholes's analysis of Brahms's D minor Concerto accurately captures the ways in which Brahms's concerto resembles and differs from Beethoven's, concluding that it is by these differences that Brahms asserts his independence from Beethoven, I find that the points in which Brahms's concerto deviates from Beethoven's are those in which he follows a different model, namely Mozart's D minor Concerto, K. 466, a work that Brahms performed in Hamburg in 1856, while at work on his own concerto, for Mozart's centennial. Brahms's and Mozart's concertos share their D minor tonality and a minor-to-major tonal trajectory. In the first movement of both concertos the soloist enters hesitantly with a quiet new theme that is organized as a dissolving period, and the soloist's exposition features the addition of a new secondary theme that functions as the third part of what Hepokoski and Darcy refer to as a trimodular-block.Footnote 4 The closing rondos of the two concertos also share a number of parallels; most significant among them is the fact that both shift from D minor to D major not in the recapitulation of the second theme, as Beethoven's Finale does, but at the end of the cadenza. Accordingly, the place where Brahms breaks free from Beethoven's model is precisely one of the points where he seems to follow Mozart's. The allusion to Mozart is significant, for as Sholes notes, ‘Brahms does not effectively declare his autonomy if he merely resorts to a second model in deviating from the first’ (p. 172). Perhaps, then, Brahms's concerto is less about his breaking free from Beethoven than it is an homage to both Beethoven and Mozart (as noted above, the allusion to Mozart's concerto relates directly to Brahms's performance of this work in celebration of the composer's centennial). By alluding to Mozart and Beethoven, Brahms places himself in their company, establishing his place in the canon.

Although the focus of the book is on the works of the formative years, Sholes proposes that Brahms's handling of allusory material in later works evinces the composer's same preoccupation with the past and his place in music history, closing her book with an analysis of the Finale of Brahms's Fourth Symphony, op. 98. Like many before her, Sholes hears the theme of the chaconne as an allusion to the theme from J.S. Bach's Cantata 150 and thus as an effort on the part of Brahms to connect to the past. What is new is her claim that the major mode variations of the theme allude to the Pilgrims’ Chorus from Wagner's Tannhäuser, a point that she expounds on by discussing the complex relationship between Brahms and Wagner. Since both the Cantata and the Pilgrims’ Chorus speak of death and transcendence, Sholes proposes that the Wagner allusion may be heard either as an homage to Wagner, who died shortly before Brahms started to work on this Symphony, or as an elegy to the passing of the musical tradition to which Brahms himself belonged.

Even though I interpret some passages differently from Sholes, I found the idea that Brahms's use of allusory material reflects his attitudes towards the past quite compelling. The focus on Brahms's early works is both appropriate and refreshing, for it offers insights into works not often discussed in Brahms studies, and the analyses, though detailed, are easy to follow, due in large part to the numerous musical examples. One way to build upon Sholes's ideas would be to consider the way in which Brahms reckoned with Schubert's legacy, especially in the area of form, for while it is well-known that Brahms inherited his use of three-key sonata expositions from Schubert, little has been written about the ways in which Brahms departs from the Schubertian model. Another possible extension of this study would be to discuss the evolution of Brahms's handling of allusions as his life circumstances changed, as did the composers to which he turned (Schubert's influence, for instance, seems to have come at a later time than that Beethoven's). Finally, it would be interesting to consider Brahms's use of allusion from the point of view of historiography. From this perspective, Brahms is not simply drawing on the past; he is it interpreting it for us through his own music.