I. Background

Since 2010, the United States has tried to address racial health disparities using the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) framework that recognizes social factors, outside an individual's control, cause these disparities.1 The SDOH framework identifies five key areas of social factors connected to racial health disparities: economic stability; education; social and community context; health and health care; and neighborhood and built environment. As of 2018, racial health disparities continue and are estimated to cost the United States $175 billion in lost life years (3.5. million lost years times $50,000 per life year) and $135 billion per year in excess health care costs and untapped productivity.Reference Turner2 These disparities persist because of the failure to account for and address structural racism, the root cause of racial health disparities.Reference Yearby3

Structural racism is the way our systems (health care, education, employment, housing, and public health) are structured to advantage the majority and disadvantage racial and ethnic minorities. More specifically, it produces differential conditions between whites and racial and ethnic minorities in the five key areas of the SDOH, leading to racial health disparities. Law is one of the tools used to create these differential conditions by structuring systems in a racially discriminatory way. For example, during the Jim Crow era (1875-1964), the government used law to structure the employment system in a manner that benefited whites and harmed racial and ethnic minorities.4

Specifically, many laws that expanded collective bargaining rights either explicitly excluded racial and ethnic minorities, or allowed unions to discriminate against racial and ethnic minorities.5 These employment laws create differential conditions between whites and racial and ethnic minorities that benefited whites by providing them with access to rights and unions that resulted in paid sick leave coverage. However, it left racial and ethnic minority workers without union representation and paid sick leave, forcing them to go to work even when they were sick. This issue persists today and is one of the causes of racial disparities in COVID-19 infections and deaths.Reference Yearby and Mohapatra6 Many racial and ethnic minorities do not have paid sick leave, so they must go to work even when they are sick, while most whites have paid sick leave and can stay at home. Consequently, racial and ethnic minorities without paid sick leave are more likely than whites to be exposed to COVID-19 in the workplace, resulting in racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 infections and deaths.7 Structural racism produced racial differences in who has paid sick leave, which is a major cause of these health disparities. Yet, structural racism is often ignored as a root cause of racial health disparities.8

This commentary not only describes the ways that structural racism causes racial health disparities, but also highlights the need for a multi-layered approach to the SDOH framework in order to achieve racial health equity. The commentary proceeds as follows: Part II outlines how the current SDOH framework fails to include many of the integral factors causing racial health disparities, such as structural racism and the law. Next, Part III uses the plight of home health workers to explore the ways that law is used to structure the employment system in a racially discriminatory way, resulting in racial health disparities. Finally, Part IV provides a reimagined SDOH framework with a multi-layered approach to address racial health disparities and achieve racial health equity.

This commentary not only describes the ways that structural racism causes racial health disparities, but also highlights the need for a multi-layered approach to the SDOH framework in order to achieve racial health equity. The commentary proceeds as follows: Part II outlines how the current SDOH framework fails to include many of the integral factors causing racial health disparities, such as structural racism and the law. Next, Part III uses the plight of home health workers to explore the ways that law is used to structure the employment system in a racially discriminatory way, resulting in racial health disparities. Finally, Part IV provides a reimagined SDOH framework with a multi-layered approach to address racial health disparities and achieve racial health equity.

II. The Incomplete SDOH Framework

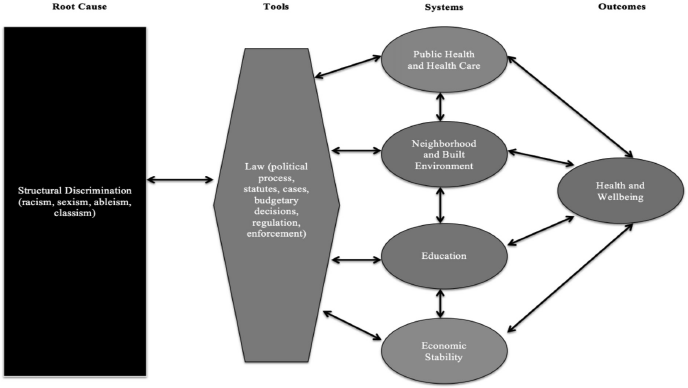

In 2003, the Institute of Medicine issued the landmark report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare, which highlighted the association of health disparities and racial discrimination on mortgage lending, access to housing, employment, and criminal justice.9 This report and the World Health Organizations’ 2008 report on health equity10 were the foundation for the creation of the SDOH Framework in the United States. Figure 1 displays the Healthy People 2020 SDOH framework used by the government and public health officials to address racial health disparities, while Figure 2 shows the five key areas.11

Figure 1 Healthy People 2020

Figure 2

According to the current SDOH framework, the five key areas cover the conditions and “the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affects a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.”12 Although public health professionals created the SDOH frame-work, the framework fails to mention public health as a key area. Yet, the public health system is responsible for racial inequities in the conditions and the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age. Illustrative of this point is the current COVID-19 pandemic.

A. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Why the Public Health System is a SDOH

In 2008, Blumenshine et al. hypothesized that there were racial and ethnic disparities in infections and deaths during pandemics because racial and ethnic minorities experienced: increased exposure to pandemics because they worked in low wage essential jobs that did not provide paid sick leave or the option to work at home; increased risk of susceptibility because of preexisting health conditions sometimes linked to their employment or living arrangements; and lack of access to a regular source of health care as well as appropriate treatment during pandemics.Reference Blumenshine13 When the 2009 H1N1 pandemic occurred, a group of researchers using health and survey data showed that Blumenshine's factors were associated with racial and ethnic minorities’ increased infection, hospitalization, and death from H1N1.14 Specifically, racial and ethnic minorities were unable to stay at home, suffered from health conditions that were risk factors for H1N1, and lacked access to health care for treatment, all of which increased their H1N1 infection and death rates.15 In fact, in Oklahoma, H1N1 rates for African Americans were 55% compared to 37% for Native Americans and 26% of Whites.16 Nationally, Native Americans’ mortality rate from H1N1 was four times that of all other racial and ethnic minority populations combined.Reference Andrulis17

Unsurprisingly, these same racial health disparities are being replicated during the COVID-19 pandemic.18 The Navajo Nation (spread across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah) have more infections (2,304 per 100,000) than New York State (1,806 per 100,000),Reference DeSantis19 and the African American COVID-19 death rates are higher than their percentage of the population in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (66% of deaths, 41% of population),Reference Powell20 Illinois (43% of deaths, 28% of infections, 15% of population),Reference Nowicki21 and Louisiana (46% of deaths, 36% of population).22 These racial health disparities COVID-19 infections and deaths are in large part because many racial and ethnic minorities are employed as essential workers and lack paid sick leave, so they must work even when they are sick.23

Nevertheless, the public health system has ignored these factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, the public health system response includes stay at home orders and social distancing recommendations that do not address the lived experiences of racial and ethnic minorities who are disproportionately essential workers, without paid sick leave. Therefore, these racial and ethnic minorities are unable to stay at home or practice social distancing compared to whites. Additionally, some federal public health officials and state government officials have begun to blame racial and ethnic minorities for racial disparities in COVID-19,Reference Tahir, Cancryn, Sesin, Murphy, Stein, Gabriel, Westwood and Serfaty24 instead of mandating health and safety requirements for essential workers or sharing data with Native American tribes for contact tracing, which would protect racial and ethnic minorities. These failures in the public health system's COVID-19 response have resulted in racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 infections and deaths. Hence, the public health system is a social determinant of health, which needs to be listed in the SDOH framework. Structural racism, the root cause of racial health disparities, is also missing from the SDOH framework.

B. Structural Racism: A Root Cause of the SDOH

In the current SDOH framework, discrimination (individual and structural) is only housed under the key area of social and community context, along with civic participation and incarceration. Individual discrimination is defined as negative interactions between individuals in their institutional or public/private roles, while structural discrimination is defined as “macro-level conditions (e.g. residential segregation) that limit ‘opportunities, resources, and well-being’ of less privileged groups.”25 According to the SDOH framework, residential segregation is a form of structural discrimination in the housing market, which causes major differences in “health status between African American and white people because it can determine the social and economic resources for not only individuals and families, but also communities.”26 Discrimination is only identified as an issue under the area of social and community context, even though the 2003 IOM report noted that discrimination limited racial and ethnic minorities equal access to mortgage lending, housing, and employment. The limited discussion of discrimination in the SDOH framework is also in stark contrast to other public health frameworks, which identify discrimination, particularly racism, as a root cause of racial health disparities.Reference Williams, Ford, Airhihenbuwa, Ford and Airhihenbuwa27

In fact, some U.S. public health scholars began to argue that discrimination, including racism, was a significant cause of racial health disparities when the SDOH framework was first issued as part of Healthy People 2020. For example, in 2011, Braveman et al. argued that health disparities “do not refer generically to all health differences, or even all health differences warranting focused attention. They are a specific subset of health differences of particular relevance to social justice because they may arise from intentional or unintentional discrimination or marginalization and, in any case, are likely to reinforce social disadvantage and vulnerability.”Reference Braverman28 Professor David R. Williams, a sociologist and pioneer in this area, has not only noted that racism is linked to racial health disparities,Reference Williams, Mohammed, Williams, Collins and Williams29 but he also created a model showing how multiple forms of racism can affect health.Reference Williams30 I have also written about how racism is the root cause of racial health disparities in nursing home care and the allocation for health care resources.Reference Yearby and Yearby31

Although there are many forms of racism, structural racism has the most impact on the five key areas of the SDOH framework because, as social epidemiologists note, it includes “the totality of ways in which societies foster discrimination, via mutually reinforcing systems of discrimination (e.g. in housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, criminal justice, etc.) that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources.”Reference Berkman and Krieger32 Law, including the political process, is the tool used to structure American systems, such as health care and employment, in a racially discriminatory way.

B. Law: The Tool of Structural Racism

As Professor Freeman notes in his groundbreaking article, Legitimizing Racial Discrimination Through Antidiscrimination Law: A Critical Review of Supreme Court Doctrine, “law serves largely to legitimize the existing social structure and especially class relationships within that structure,” which is evident in antidiscrimination law.Reference Freeman33 Antidiscrimination law is based on the premise that discrimination is tied to the actions of an individual or institutional perpetrator, and thus it only tries to neutralize the inappropriate conduct of the perpetrator. This legitimizes the existing social structures, because law never questions the structures built to limit racial and ethnic minorities’ equal access to education, employment, housing, and health care.

Consequently, it leaves in place the laws that benefit the majority and harm racial and ethnic minorities.34 Thus, although some research has shown that the enforcement of antidiscrimination law in healthcare, education, employment, and housing can decrease racial health disparities,Reference Hahn35 racial health disparities still persist because the law, including the political process,Reference Dawes36 has not changed the structures of these systems. Instead, law (political process, statutes, regulations, policies, guidance, advisory opinions, cases, budgetary decisions, as well as the process of or failure to enforce the law) is used as a means of fostering structural racism. The long-term care system is illustrative of this point.

With the passage of the Social Security Act of 1935, the federal government funded private long-term care for the elderly, prohibiting funding for private institutions that provided care to African Americans.37 As a result of the influx of cash, private nursing homes were developed for rich Whites and private boarding houses were developed for poor and disabled Whites, while racial minorities were relegated to public boarding houses.Reference Smith38 In 1946, the federal government enacted the Hill-Burton Act, to provide for the construction of public long-term care facilities.39 Although the Act mandated that adequate healthcare facilities be made available to all state residents without discrimination of color, it allowed for states to construct racially separate and unequal facilities.40 Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited racially separate and unequal long-term care facilities, but President Johnson noted that unlike hospitals, nursing homes were viewed as private residences. Hence, the President and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services were unwilling to wage a massive attack to enforce Title VI to integrate these “homes.” Thus, nursing homes remain racially separate and unequal, which has cause racial health disparities.

From 1964 through the present, studies show that most African Americans reside in racially separate nursing homes that provide substandard quality care compared to the nursing homes in which whites reside, resulting in higher incidences of pressure sores, falls, use of physical restraints, rehospitalization, and use of antipsychotic medications in African Americans.Reference Rivera-Hernandez, Akamigbo, Wolinsky, Wallace, Smith, Amber, Sullivan and Sullivan41 Hence, due to the laws of 1935 and 1946 as well as the political choices to not enforce Title VI in the provision of long-term care services, whites continue to be benefited, while African Americans continue to be harmed. This is structural racism. Structural racism not only impacts the health care system, but it also influences the employment system, as evidenced by the predicament of home health care workers.

III. Employment, Structural Racism, and Racial Health Disparities: The Example of the Health Care Worker

Under the SDOH framework, the area of economic stability incorporates the employment system, including compensation and benefits (health insurance). Racial inequities in the employment system are linked to health disparities, but the root cause of these racial inequities is not identified or discussed in the SDOH framework. For example, the framework states “21% of African Americans work in jobs that put them at high risk for injury or illness compared to only 13% of white people.”42 Yet, the discussion fails to explore the reasons for these racial inequities or provide solutions besides workforce development. These racial inequities in economic stability are due to structural racism that prevents wage and worker safety laws from being applied to jobs disproportionately held by racial and ethnic minorities. Home health care workers, who are primarily women of color (almost two-thirds of all home care workers),43 serve as a poignant example of this problem.

In 2018, there were approximately 832,000 home health care workers, which is projected to grow to 1.1 million in 2028 because of the growing elderly population. It is estimated that the population of adults ages 65 and older will increase from 47.8 million in 2015 to 88 million in 2050, while the population of adults over 85 will go from 6.3 million in 2015 to 19 million in 2050.Reference Twomey44 Thus, the need for home health care workers is projected to increase by 37% from 2018 to 2028, which is much faster than the average growth (5%) for all occupations.45 Home health care workers, who provide assistance with activities of daily living and perform clinical tasks such as taking blood-pressure readings, administering medication, and wound care,46 are either employed by home health care agencies or directly by the patient to provide care in the patient's home. Regardless of the employer, these workers remain in poverty, lack access to health care, and suffer significant health disparities as a result of laws that advantage business owners and disadvantage racial and ethnic minority workers.

As illustrated by home health workers’ struggle, structural racism is the root cause for these differential conditions between whites and racial and ethnic minorities, which produces racial health disparities. Since the current SDOH framework fails to acknowledge that structural racism is the root cause of racial health disparities, it is inadequate as a means to achieve racial health equity. Hence, the SDOH framework must be revised.

For example, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (FLSA)47 limited the work week to 40 hours and established federal minimum wage and overtime requirements.48 The FLSA exempted from these protections domestic, agricultural, and service occupations, which were predominately filled by racial and ethnic minorities. In 1974, the law was amended to cover domestic workers, but those providing companionship services were exempted from these protections.Reference Smith49 Home health care workers, who are primarily women of color,50 were determined to provide companionship services. Consequently, they were exempted from federal minimum wage and overtime requirements regardless of whether they worked for an individual employer or home health care company.51

Even though the Department of Labor (DOL) issued regulations in 2015 that for the first time made the FLSA apply to most home health care workers,52 many workers still remain unprotected. The DOL under the Trump Administration has taken a more conservative approach in whether home health care workers employed by home health care companies, also referred to as nurse or caregiver registries, are employees or independent contractors.Reference Department53 This is significant because the FLSA does not apply to independent contractors. Because many home health acre workers are labeled as independent contractors, the FLSA does not apply to them, which means they do not receive the federal minimum wage or overtime pay.

Unsurprisingly, the job of home health care worker was listed as one of the top 25 worst paying jobs in the United States in a 2017 Forbes magazine story.54 In 2019, the median average annual wage of a home health worker providing services to patients within their home was $25,330, with a median hourly wage of $12.18.55 Although the Medicaid program56 primarily funds direct care workers, the wages of home care workers are so low that one in five (20%) home care workers are living below the federal poverty line, compared to 7% of all U.S. workers, and more than half rely on some form of public assistance including food stamps and Medicaid.57 The job is also hard because of the lack of health insurance and risk of injury on the job.

Most home health care workers are “unable to afford their share of the health insurance premiums or they are ineligible for coverage because they work part time or are classified as independent contractors by their home health care agency.”58 In 2005, 30% of female home health care workers did not have any health insurance, compared to 16% of all female workers. Twenty-nine percent of home health care works relied on public health insurance (Medicaid) compared to 12% of all female workers.59 By 2017, almost 20% of home health care workers were without health insurance and another 39% relied on Medicaid, Medicare, or some other form of public coverage.60 More specifically, a study of Los Angeles’ home health care workers found that approximately 45% of them did not have health insurance.

The lack of health insurance is also critically important to home health care workers because they have one of the highest rates of workplace injuries.61 In fact, the rate of non-fatal occupational injury and illness days away from work for direct care workers, including home health care workers, is 526 incidents per 10,000 workers compared to 488 for construction workers and 411 for truck drivers.62 Injuries and illnesses related to patient interaction accounted for 56% of all injuries and illnesses, while 86% were a result of overexertion.63 The Occupational Safety and Health Act and most state worker compensation statutes exclude domestic workers, including home health care workers.64 Therefore, when home health care workers get hurt doing their jobs, they do not receive workers compensation to replace their wages or pay for health care to treat the injury.

The failure to provide home health care workers with higher wages, health insurance, and workplace protections is due to structural racism. The initial failure to cover these workers under the FLSA benefited white workers by boosting their wages, while limiting the wages of racial and ethnic minorities, particularly women of color. Seventy-seven years later, when most home health care workers were finally covered by the FLSA, companies began classifying them as independent contracts. This benefits the companies by lowering employment costs, while harming workers who are left with low pay and without overtime pay or workers compensation coverage for workplace injuries. Due to low wages and lack of paid sick leave, home health care workers must continue to work with injuries and in close proximity to patients that are often ill with infectious disease, like COVID-19, leading to racial health disparities.

As illustrated by home health workers’ struggle, structural racism is the root cause for these differential conditions between whites and racial and ethnic minorities, which produces racial health disparities. Since the current SDOH framework fails to acknowledge that structural racism is the root cause of racial health disparities, it is inadequate as a means to achieve racial health equity. Hence, the SDOH framework must be revised.

IV. The Reimagined SDOH Framework

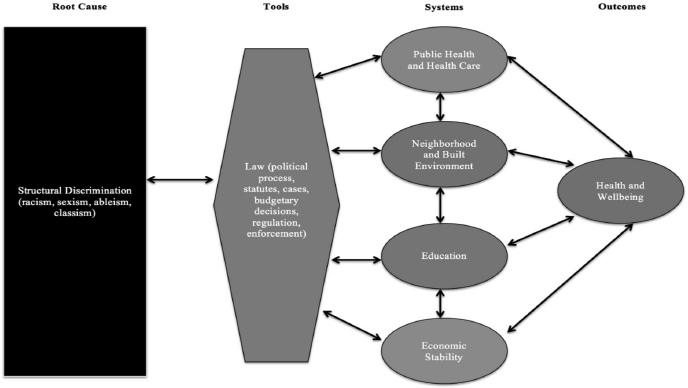

To eliminate racial health disparities, the SDOH framework must include the root cause of racial health disparities and a multi-layered approach. Other scholars have proposed different models to show how discrimination influences health.Reference Gilbert and Ray65 For instance, Professors Chandra Ford and Collins Airhihenbuwa, who created the public health critical race praxis (PHCR), noted structural determinism (which I call structural discrimination) and racial categories are the bases for ordering society, which contributes to racial health disparities.66 Building on these models, my reimagined SDOH Framework, shown in Figure 3, makes changes that are easy to adopt as part of the 2030 Healthy People Objectives, which have not yet been published.

Figure 3 Revised SDOH framework created by Ruqaiijah Yearby (2020)

First, in recognition of the work of social epidemiologists, I have changed key areas to systems because American systems structured in a racially discriminatory way reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources, leading to racial health disparities.67 Second, public health is an integral factor in racial health disparities, and thus must be included in the SDOH Framework as a key system that impacts health. I recommend that “health” should be removed from the health and health care area because it is an outcome of the social determinants of health, not a factor. It should be replaced by public health. Health and wellbeing are then shown as the outcome from each of the key systems.

Third, the social and community area is made up of discrimination, civic participation, and incarceration. I moved civic participation from social and community context to the neighborhood and built environment system, since it is tied to neighborhood and incarceration is linked to the built environment. Additionally, because structural racism is a root cause of racial health disparities, which influences all of the key systems of my revised SDOH framework, it does not fit under social and community context. Therefore, in my framework, I have deleted social and community context, leaving four key systems that impact health and wellbeing.

Fourth, structural discrimination, which includes structural racism, is separate from the key systems and so is law. As black feminist and feminist theorists have noted, the law often reinforces discrimination, protecting those with power and leaving those without power susceptible to mistreatment, especially women.Reference Harris, Threedy, Olsen, Kairys, Hirshman, Paetzold, Crenshaw and King68 Thus, structural discrimination is shown as the root cause of health disparities, while law is show as the tool. Finally, in my framework, although not shown in Figure 3, individual and institutional discrimination are present in each of the four key systems because they reinforce differential conditions in the system that benefit whites and harm racial and ethnic minorities.

The purpose of my reimagined SDOH framework is to provide the root cause and tool used to structure systems in a racially discriminatory manner that prevents racial health equity. When using the framework, government and public health officials are primed to make the connection between structural discrimination, law, systems, and racial health disparities. Yet, this is just the beginning.

To achieve racial health equity, government and public health officials must aggressively work to end structural racism and revamp all of our systems, especially the public health system, to ensure that racial and ethnic minorities are not only treated equally, but also receive the material support they need to overcome the harms they have already suffered. Only then can we truly begin to work towards improving the health and wellbeing of racial and ethnic minorities, so that we can achieve racial health equity.