1. INTRODUCTION

The field of experimental pragmatics investigates pragmatic hypotheses by means of offline and online tasks such as reaction time and error rate measurements as well as eye tracking (for an overview see Sperber and Noveck, Reference Sperber and Noveck2004; Meibauer and Steinbach, Reference Meibauer, Steinbach, Meibauer and Steinbach2011).

Current psycholinguistic models of language processing and lexical access generally do not focus on pragmatic information and lack a clear differentiation between pragmatic, semantic and conceptual representations. Many psycholinguistic studies do not differentiate at all between a semantic and a conceptual level of language processing and use both terms interchangeably (see Pavlenko, Reference Pavlenko and Pavlenko2009). Still, the differentiation of these representation levels may be crucial for certain psycholinguistic questions and experimental investigations. Furthermore, most studies do not address the issue of pragmatic language processing at all. Therefore, it remains unclear where pragmatic information enters into the process of lexical access. One possible approach is that pragmatic information can only enter into speech processing in sentence context, because single words cannot give much information of the different functions of the respective word. This would mean that pragmatic information is only necessary and accessible in sentence context. In psycholinguistic research on sentence processing, it is still controversially discussed when and how semantic and syntactic information is accessed.

The present article aims to give new insights into the processing of pragmatic information, more precisely of semantic and pragmatic representations of pragmatic markers. The focus of the investigation will lie on two main questions of semantic representation of pragmatic markers. On the one hand, it will be questioned, if pragmatic markers have an impact on sentence comprehension at all. On the other hand, it will be investigated, if the different meaning patterns and pragmatic functions of pragmatic markers show an impact on sentence processing. These problems will be discussed by means of experimental data on the pragmatic markers comme and genre in Manitoban French, a variety of Canadian French, and European French. The marker comme underwent contact-induced transfer of meaning patterns in Canadian French that did not take place in European French. On the contrary, the marker genre underwent an expansion of meaning patterns and pragmatic functions in European French but not in Manitoban French. Therefore, these lexical items are very suited for a comparative analysis and experimental investigation on conceptual and semantic representations.

2. PRAGMATIC MARKERS

Pragmatic markers have been in the focus of scientific discussion for more than three decades and there is still no consent on their exact classification, delimitation and definition (for a detailed overview see e.g. Hansen, Reference Hansen1998; Andersen, Reference Andersen2001; Aijmer, Reference Aijmer2002; Aijmer and Simon-Vandenbergen, Reference Aijmer and Simon-Vandenbergen2006). In the present account, pragmatic markers are defined as lexical items that are highly polysemous (Hansen Reference Hansen1998), polyfunctional (Aijmer, Reference Aijmer2002), syntactically flexible and occur mostly in sentence-peripheral positions (Brinton Reference Brinton1996). Furthermore, they generally fulfill discourse-pragmatic functions (Gülich, Reference Gülich1970) and do not contribute to the propositional content of an utterance (Brinton Reference Brinton1996). In the present approach, I will follow Beeching (Reference Beeching2011) by distinguishing between discourse connectives and other discourse particles, here termed pragmatic markers. Discourse connectives as defined by Beeching (Reference Beeching2011:100) will not be subject of this article.

2.1 Semantic meaning patterns and pragmatic functions of pragmatic markers

There is by far no agreement on the semantic meaning patterns of pragmatic markers and especially on their interrelation and their nature. Here, the main questions concern two very different aspects of the meaning of pragmatic markers. The first problem is to define the interrelation of semantic meaning patterns, that is to decide if pragmatic markers are polysemous or monosemous items. It is generally accepted that most pragmatic markers emerged from other word types through processes such as grammaticalization or pragmaticalization. This leads to the fact that pragmatic markers commonly have more than one meaning. When taking a polysemy perspective on pragmatic markers (e.g. in the work of Hansen, Reference Hansen1998; Aijmer and Simon-Vandenbergen, Reference Aijmer and Simon-Vandenbergen2003; Waltereit, Reference Waltereit, Dostie and Pusch2007; Pons Bordería, Reference Pons Bordería2008), lexical items with various interrelated senses are defined as being polysemous. The polysemy approach claims that:

most linguistic word forms have more than one meaning, not only at the level of parole but also at the level of langue, and that these meanings are related to one another in ways that can at least be motivated, if not fully predicted. (Mosegaard Hansen, Reference Hansen2008: 35)

In contrast, the monosemy approach (e.g. in the work of Fischer, Reference Fischer2000; Weydt, Reference Weydt1969; Fraser, Reference Fraser and Fischer2006; Schiffrin, Reference Schiffrin1987) claims that:

Each phonological/orthographic form is associated with a single invariant meaning. This invariant meaning may describe the common core of the occurrences of the item under consideration, its prototype, or an instruction. Individual interpretations arise from general pragmatic processes and are not attributed to the item itself. (Fischer, 2005: 13)

Therefore monosemy-oriented studies try to establish a core meaning of different pragmatic markers. But also scholars following the polysemy approach may assume that pragmatic markers have a core meaning (from a polysemic perspective), in that they have one meaning that is more dominant than others (see e.g. Aijmer and Simon-Vandenbergen, Reference Aijmer and Simon-Vandenbergen2003). Still, in a polysemy approach it is not a prerequisite to assume a core meaning, it is also possible to accept different interrelated meanings without one clear dominant sense (e.g. Waltereit, Reference Waltereit, Drescher and Frank-Job2006). Especially in the monosemy approach, determining a core meaning is not without problems. The core meaning is often too broad and cannot really distinguish a certain pragmatic marker from others. This is mainly due to the fact that a core meaning does not only try to account for the different semantic meaning patterns of a pragmatic marker, but also for its pragmatic and intertextual functioning (Aijmer, Reference Aijmer2002: 23). This gets particularly complicated in studies that focus on cross-linguistic comparisons of discourse-pragmatic features and meaning patterns of pragmatic markers. Waltereit (Reference Waltereit, Drescher and Frank-Job2006) points out that there is no satisfactory way of comparing partial equivalent pragmatic markers from different languages from a monosemy perspective, because it cannot explain functional differences in the different languages (Waltereit, Reference Waltereit, Drescher and Frank-Job2006: 8). On the contrary, the polysemy approach can account for cross-language differences and semantic change without problems. Furthermore, the polysemy approach allows that pragmatic markers from different languages may overlap in some of their meanings and functions and not in others.

A second problem in research on pragmatic markers is the question of whether they contribute to the truth-conditional meaning of an utterance or not and whether they encode conceptual meaning or not. The distinction between truth-conditional and non-truth-conditional meaning commonly describes the distinction between semantics (truth-conditional) and pragmatics (non-truth-conditional). Most studies assume that pragmatic markers generally do not affect the truth-conditions of a sentence. That is to say that they rather indicate how to interpret an utterance than to contribute to its content. This approach is not without controversy; Blakemore (Reference Blakemore2002) argues that the view semantics = truth-conditions and pragmatics = meaning minus truth-conditions, is not adequate for an analysis of pragmatic markers. She defends a relevance-theoretic approach to pragmatic markers, based on Sperber and Wilson (Reference Sperber and Wilson1986) (see also Andersen, Reference Andersen2001). In this view, pragmatic markers are not directly mapped onto a conceptual representation, but function as items that modify the interpretation of an utterance and help the hearer to decode the message. The strict distinction between words encoding procedural and conceptual meaning has been criticized in current research (e.g. Hansen, Reference Hansen2008; Pons Bordería, Reference Pons Bordería2008; Fraser, Reference Fraser and Fischer2006). Fraser (Reference Fraser and Fischer2006) claims that lexical items can encode procedural meaning and a conceptual component of meaning at the same time. This view has even been adopted by Wilson (2011), who claims that “conceptual and procedural meaning should not be treated as mutually exclusive” (Wilson, 2011: 14).

As already mentioned, pragmatic markers are characterized by their spectrum of pragmatic functions. This polyfunctionality is commonly accepted and also goes back to the evolution paths of pragmatic markers. Most markers emerged from already existing lexical items such as adverbs (e.g. well, bon, bien, alors, donc) and conjunctions (e.g. so, like), which often already were multifunctional in their grammatical functions. Still, all of these lexical items developed pragmatic functions over time. In most cases, grammatical and pragmatic functions coexist, but they are generally clearly distinguishable (e.g. the adverb well and the pragmatic marker well). Furthermore, most pragmatic markers are also polyfunctional at the pragmatic level. While there is general agreement on the fact that pragmatic markers are polyfunctional items, there is discussion on an explanation. From a monosemy approach, every marker has a core meaning that varies according to the respective contextually determined meanings and functions. From a polysemy approach, the different functions are simply a result of common processes of language change that is of the emergence of new functions over time. It is self-evident that different pragmatic markers differ importantly in their pragmatic functions. But it is still possible to point out some functions, which occur on a more frequent basis. When researchers aim to point out more frequent functions of pragmatic markers, they generally mention functions as face-threat mitigators, as emphasizers or intensifiers, attenuation or mitigation purposes or to express the speakers’ attitude. Another function of pragmatic markers may be to establish coherence in discourse interpretation. Aijmer (Reference Aijmer2002) points out that “when discourse particles are absent or if they are used wrongly, listeners may have difficulty in establishing a coherent interpretation of discourse” (Aijmer, Reference Aijmer2002: 15). She refers to this phenomenon as indexicality, that is pragmatic markers create an indexical relation to the context and therefore serve in utterance interpretation.

According to Aijmer, it is not possible to determine the concrete number of functions of a pragmatic marker. In contrast to this opinion, a wide range of studies have tried to establish the semantic meaning patterns and functions of specific pragmatic markers. In light of this it is considered problematic to establish universally valid pragmatic features for pragmatic markers. Here, it seems more plausible to determine the functions of a given pragmatic marker on the basis of corpus data (see Hennecke, Reference Hennecke2014).

2.2 Experimental research on pragmatic markers

Only a few studies focus on the role of non-prototypical word types in monolingual and bilingual speech processing. An important problem in psycholinguistic research concerns the role of connectives, relational markers, pragmatic markers and hedges in sentence comprehension. These items are often referred to as encoding procedural meaning and/or not contributing to the truth-conditional content of an utterance. The main issue relates to their role in linking different parts of speech and establishing coherence in sentence comprehension. It is assumed that increasing coherence leads to increasing comprehension and in consequence to faster response latencies (Britton, Reference Britton and Gernsbacher1994; Britton and Gülgoz, Reference Britton and Gulgoz1991; Murray, Reference Murray, Lorch and O'Brien1995). Three main assumptions have been made in current research on the effect of connectives and relational markers on sentence comprehension. First, they may have a facilitatory effect (Haberlandt, Reference Haberlandt, Le Ny and Kintsch1982; Bestgen and Vonk, Reference Bestgen and Vonk1995; Sanders and Noordman, Reference Sanders and Noordman2000); second, they may have an interfering effect (Sanders, Reference Sanders1992; Millis et al., 1993), or third, no effect at all (Meyer, Reference Meyer1975; Sanders, Reference Sanders1992). Most current experimental evidence on this topic focuses on different reading tasks in sentence and text processing (for an overview see Sanders and Noordman, Reference Sanders and Noordman2000). The research on the role of pragmatic markers and hedges in conversation mostly focuses on speech production and the results are mainly based on the analysis of spoken language corpus data. Until today, only a few studies centre on the processing of pragmatic markers and hedges and their effect on speech comprehension (Fox Tree, Reference Fox Tree1995; Fox Tree and Schrock, Reference Fox Tree and Schrock1999; Holtgraves, Reference Holtgraves2000; Blankenship and Holtgraves, Reference Blankenship and Holtgraves2005; Fox Tree, Reference Fox Tree2006; Liu and Fox Tree, Reference Liu and Fox Tree2012). Fox Tree (Reference Fox Tree1995) observed the influence of the pragmatic marker and on the processing of false starts that occur at the beginning of an utterance (beginning false starts) or in the middle of an utterance or respectively after a pragmatic marker (middle false starts). Participants showed slower response latencies in English and Dutch word monitoring tasks when the false starts were preceded by and than without the lexeme and. Her findings suggest that and prefacing a false start changes a beginning false start into a middle false start in the hearers’ perception. In the relevant study on the marker oh, Fox Tree and Schrock (Reference Fox Tree and Schrock1999) performed two word-monitoring tasks and three semantic verification tasks in order to determine the role of oh in sentence comprehension. To compare the impact of oh on sentence comprehension, they aimed to compare parts of speech containing oh with the same parts of speech with oh digitally spliced out (pause). In the word monitoring tasks (adapted from Marslen-Wilson, Tyler Reference Marslen-Wilson and Tyler1980), participants listened to an excerpt of speech and pressed a button when they heard a particular word that was defined beforehand. One word-monitoring task (Experiment 1) included a pause; the second word-monitoring task (Experiment 2) was performed without pause. In the semantic verification tasks, the participants saw a visual target word while listening to the speech and they had to press a respective button depending on whether the word occurred in the auditory speech or not. In the first semantic verification task (Experiment 3), oh was replaced by a pause, in Experiment 4, it was excised entirely. In Experiment 5, participants pressed no key when the respective word did not occur in the discourse. Fox Tree and Schrock found facilitatory effects for speech comprehension in word monitoring and semantic verification tasks after the marker oh compared to conditions where the oh was replaced by a pause or left out completely (Fox Tree and Schrock Reference Fox Tree and Schrock1999: 293).

Still, their design includes several problematic issues, such as the length of the stimuli, varying from 41 to 247 words, and the differing placement of oh in the stimulus messages (Fox Tree and Schrock Reference Fox Tree and Schrock1999: 285). Furthermore, the stimuli selection is not entirely clear. They state that the same stimuli are selected for experiment 1–4. The initial stimuli are used in Experiments 1 and 3, but in Experiments 2 and 4, “several long trials were shortened to reduce the likelihood of participants’ forgetting the target words while listening to the trials and more prominent target words were selected” (Fox Tree and Schrock, Reference Fox Tree and Schrock1999: 288). Experiment 5 contains partly the same stimuli as Experiment 4, partly completely new stimuli. The reason for this procedure and the resulting differences in the effects remain unclear. These inaccuracies in the design and procedure do not allow assigning the effects and the results unequivocally to the experimental variable. In a judgement experiment with question-reply exchange, Holtgraves (Reference Holtgraves2000) examined the speed and judgement of face-threatening interpretation of the pragmatic marker well. His results suggest that participants were significantly faster at verifying a face-threatening interpretation when the utterance contained well. These results were confirmed in a second experiment that measured sentence verification response latencies.

All studies on the processing of pragmatic markers vary in the concrete object of research, the applied methodology and the design and procedure of the respective experimental studies. Furthermore, there is no general agreement on the concrete interpretation of the results and their implications for theorizing and modeling. This may be partly due to the generally controversial role and classification of pragmatic markers and their strong polyfunctionality. Still, all studies presented here agree on the point that pragmatic markers play some role in establishing discourse coherence and may help the hearers’ segmentation of speech.

As already pointed out, hedges differ from other discourse-pragmatic devices in several points. They may attenuate the semantic value or the illocutionary force of an utterance and may contribute to the propositional content. Therefore, it is important to differentiate between hedging functions of pragmatic markers and other purely pragmatic, and often syntactic peripheral functions. Several recent studies on hedging and related phenomena, such as tag questions, build on the differentiation between powerful and powerless speech (Haleta, Reference Haleta1996; Hosman, Reference Hosman1989, Reference Hosman1997; Hosman, Huebner and Siltanen, Reference Hosman, Dillard and Pfau2002; Blankenship and Holtgraves, Reference Blankenship and Holtgraves2005; for a review see Hosman, Reference Hosman, Dillard and Pfau2002). According to Blankenship and Holtgraves (Reference Blankenship and Holtgraves2005), “powerless language refers to the presence of one or more linguistic features such as tag questions, hesitations, disclaimers, hedges, polite forms, and so on. Powerful language refers to the absence of these features” (Blankenship and Holtgraves Reference Blankenship and Holtgraves2005: 4). That is to say, these researchers regard powerless speech as a kind of discourse that includes a high amount of attenuation, mitigation, hesitation and monitoring, etc. They assume, amongst others, that speakers evaluate low-power speech, including hedges, pragmatic markers, tag questions etc., less positively than high-power speech. Therefore, some recent studies on hedging, implying psycholinguistic approaches, deal with the exact nature of powerless and powerful speech and its impact on the hearer. Hosman and Siltanen (Reference Hosman and Siltanen2006) investigated the effect of markers of powerful and powerless speech on speaker evaluation, control of self and control of others’ attributions, cognitive responses and message memorability on monolingual English speakers. Participants read a high-power message or one of three low-power messages, containing either hedges, tag questions or intensifiers (Hosman and Siltanen, Reference Hosman and Siltanen2006: 37). Afterwards, they completed a cognitive-response questionnaire, a questionnaire measuring the speaker's intellectual competence, and a questionnaire on self-control and control of others. Two days later, they performed a recognition memory task (ibid.).

According to the researchers, these results support the hypothesis that hedges are perceived as lower in intellectual competence and “exhibiting the least control of self and control of others” (Hosman and Siltanen, Reference Hosman and Siltanen2006: 42). Blankenship and Holtgraves (Reference Blankenship and Holtgraves2005) examined the role of hedges and hesitations on the perception of powerless and powerful speech. English-speaking participants listened to messages containing either hedges or hesitations or powerful speech and rated the messages according to different criteria such as attitude towards the message, speaker and message perception (Blankenship and Holtgraves, Reference Blankenship and Holtgraves2005: 9). As a result, they found out that messages containing hedges and hesitations led to a more negative attitude of the participants towards the message. They argue, “these markers are distracting and hence lessen the overall impact of strong arguments” (Blankenship and Holtgraves, Reference Blankenship and Holtgraves2005: 19).

In a very recent study, Lui and Fox Tree (Reference Liu and Fox Tree2012) investigated the effect of hedges and the pragmatic marker like in speech perception of monolingual English speakers. They differentiate like from other hedges, because they also consider non-hedging functions of this marker. In a first task, they recorded speakers retelling their own story (production task) and speakers retelling others’ stories (perception task). Experiment 1 showed that participants did, in most cases, not retell hedge-marked information. Lui and Fox Tree interpret this result as evidence that the listener may overlook hedge-marked information. In a second experiment, participants listened to an audio recording, containing hedge-marked, like-marked and unmarked quantities. Afterwards the participants performed a memory task. In contrary, the results of the second experiment suggest that hedged information was remembered more accurately in the memory task than non-hedged information whereas like did not have any effect on the memory task. Lui and Fox Tree conclude from their results that hedges “provide pragmatic cues about what information is reliable enough to repeat to somebody else in a conversational context, but they do not prevent people from remembering that information” (Lui and Fox Tree, Reference Liu and Fox Tree2012: 6).

All of these studies try to gain new insights into the processing of pragmatic markers and hedges. But they differ strongly in their concrete objects of investigation and in their experimental methods. While some studies aim to study the hearers’ attitude towards markers and hedges, other studies focus on the effect of markers and hedges on memorization or on the interpretation of face-threatening acts. Only Fox Tree and Schrock (Reference Fox Tree and Schrock1999) measured response latencies of participants to examine the role of a respective marker in sentence comprehension. Even though Fox Tree and Schrock have reported facilitatory effects of oh in spontaneous speech comprehension, the question of the exact effect of other pragmatic markers and hedges still remains unsolved. This is not only due to the inaccuracies in their experimental design and procedure, but also due to the role of the lexical item oh that was not defined clearly. Therefore, the present investigation aims to add relevant research results to the discussion on the role of pragmatic markers in discourse comprehension.

2.3 The pragmatic markers comme and genre in European and Manitoban French

In previous research on the use of comme, different authors pointed out that comme in Canadian French can take functions and meaning patterns that are not attested in European French (Chevalier, Reference Chevalier2001; Beaulieu-Masson et al., Reference Beaulieu-Masson, Charpentier, Lanciault and Liu2007; Mihatsch, Reference Mihatsch, Rossari, Cojocariu, Ricci and Spiridon2009). According to current research results, the most salient new functions of comme seem to include the extension in its use as a hedge and its use in quotation. The present understanding of hedges is based on Prince et al. (Reference Prince, Bosk and Di Pietro1982). They distinguish between two types of hedges, namely approximators and shields. Approximators are defined as lexical items that modify the truth-conditions of an expression while shields do not affect the truth-conditions of an utterance. Adaptors and rounders are considered as subtypes of approximators. Adaptors trigger a loose reading of a lexical unit or expression and operate on the semantic level of an utterance; whereas rounders modify a numeral value in that they indicate a vague interpretation. In contrast, shields do not modify the semantics of an utterance, but rather soften a statement and alter the illocutionary force. While other scholars extended this classification recently (e.g. Caffi, Reference Caffi2001, Reference Caffi2007), the present work will however rely on the classification of Prince et al. (Reference Prince, Bosk and Di Pietro1982). The use of comme fulfilling extended pragmatic functions has been outlined for different varieties of Canadian French. Chevalier (Reference Chevalier2001) distinguishes five different kinds of approximation, which are found in the Chiac variety of Canadian French. In her study, she differentiates between approximation qualitative (adaptors), approximation quantitative (rounder), assertion (shields and utterance-final use), discours rapporté direct (quotative use) and autocitation (quotative use) (Chevalier, Reference Chevalier2001: 20f.). All of these functions were also found in the Manitoban variety of Canadian French, which will be the research object of the following experimental investigation (for a detailed corpus-based analysis see Hennecke, Reference Hennecke2014). In European French, comme cannot fulfill this set of functions. In spoken European French, comme can function as an adaptor, but not as a shield, a rounder or a quotative marker.

Fleischman and Yaguello (Reference Fleischman, Yaguello, Moder and Martinovic-Zik2004) observe that the lexical unit genre has emerged as a pragmatic marker in European French and can be used in several of the functions listed above. Beaulieu-Masson et al. (Reference Beaulieu-Masson, Charpentier, Lanciault and Liu2007) presume that the newly emerged functions of comme in Canadian French, which arose in the course of the twentieth century, are due to long-term language contact with English and underlie the process of pragmaticalization. Fleischman and Yaguello (Reference Fleischman, Yaguello, Moder and Martinovic-Zik2004) argue that the pragmatic functions of comme mentioned above are expressed by the marker genre in spoken and informal European French. They state that genre shows a functional similarity to the pragmatic marker like in English, in that it can function as a rounder, an approximation and as a quotative marker (Fleischman and Yaguello, Reference Fleischman, Yaguello, Moder and Martinovic-Zik2004: 131ff.). According to Mihatsch (Reference Mihatsch2012), genre de is documented as an approximation marker since the fifteenth century (Mihatsch, Reference Mihatsch2012: 161). In her comparative analysis of the emergence of approximation out of taxonomic classification in Romance languages, Mihatsch (Reference Mihatsch2012) detects genre as an adaptor, a quotative and a rounder in spoken European French (Mihatsch, Reference Mihatsch2012: 204). Still, genre occurs infrequently in these functions, Mihatsch counts one occurrence of genre in a rounder function, three quotative functions and three adaptor functions (ibid.). It can be concluded that different studies confirm that genre is indeed a newly emerged and very frequent pragmatic marker in European French (see Secova, Reference Secova2011: 81 ff. as well as Mihatsch, Reference Mihatsch2012 for a detailed analysis). In Manitoban French, where the pragmatic functions demonstrated above are taken by comme, the lexical unit genre occurs rarely, even in its use as a noun.

To conclude, it can be stated that genre in European French indeed shows a certain functional similarity to the pragmatic use of comme in Manitoban French. Nevertheless, the pragmatic uses of genre are not as frequent in European French as the uses of its Franco-Manitoban counterpart. Comme in European French can fulfill pragmatic functions in a restricted sense, that is the adaptor function and the function as a repair and hesitation marker. However, the use of comme as a pragmatic marker is not very frequent in European French and therefore differs from the pragmatic marker comme in Franco-Manitoban.

The following experimental investigation aims to analyse the quotative, rounder and adaptor functions of the pragmatic markers comme and genre in more detail, in order to determine their role in language processing.

3. EXPERIMENTAL INVESTIGATION: SENTENCE-WORD VERIFICATION TASK

I designed an experimental task, more precisely a monolingual sentence verification task with lexical decision, to investigate the role of pragmatic markers and their newly emerged functions and meanings in sentence context. The present task only focuses on the functions and meaning patterns of the two partially equivalent markers comme and genre. In particular, the present study aims to investigate the question of whether the contact-promoted change of comme is anchored in language representations (for a detailed discussion see Hennecke, Reference Hennecke2014). To analyze this question adequately, the respective markers have to be investigated in context.

Since pragmatic markers are very polysemous items with a large range of functions and meanings, the sentence context plays an important role in assigning a specific function to the respective marker. Still, the processing of sentences includes additional problems, such as the integration of semantic and pragmatic information in the sentence context and the syntactic relations between words.

The role of specific grammatical constructions and word types constitutes an important part in psycholinguistic research on sentence processing. Still, as previously mentioned, few studies investigate the role of pragmatic markers in context. Therefore, the present sentence-word verification task is loosely based on the above-mentioned word-monitoring task (Experiment 1 and 2) of Fox Tree and Schrock (Reference Fox Tree and Schrock1999). It also includes multi-modal stimulus presentation but in the present task, first a spoken sentence is presented to the participants, who then perform a lexical decision on a visual stimulus word. The choice of a lexical decision task is motivated by the fact that this task allows to control for confounding variables in the stimuli sentences and to measure concrete response latencies on a target word. In lexical decision tasks, participants have to decide whether a visually presented letter string is a word or not. The decision is generally made by pressing a respective Yes- or No-key on a keyboard or a joystick. It is assumed that several factors, such as frequency, orthography or the semantic nature of the word, influence the recognition of the respective word and consequently the response latencies of the participants.

In the present investigation, I assume that an orally presented sentence has an impact on the response latencies of the participants’ decision on a related or unrelated visual stimulus word or non-word. Response latencies of participants are measured from the beginning of the presentation of the target word until the lexical decision. I further assume that words that are semantically related to the stimuli sentences trigger faster response latencies than semantically unrelated words.

The present research concerns the impact of the partially equivalent pragmatic markers comme and genre on the auditory speech perception of speakers of Manitoban French and speakers of European French. Consequently, the present experimental investigation aims to examine the following two aspects of sentence processing:

-

(1) The impact of the partial equivalent markers comme and genre on sentence processing

-

(2) The impact of contact-induced change of comme on sentence processing

Predictions

In the present investigation, I hypothesize that pragmatic markers have indeed an impact on language processing, more precisely on sentence comprehension. I expect that the markers comme and genre show different effects on sentence processing depending on their function and semantic meaning in the respective sentence context and on the two different groups. That is to say, I expect faster response latencies for the marker comme in newly emerged functions for Manitoban French participants than for European French participants. A reverse effect is expected for the marker genre. Furthermore, I hypothesize that the emergence of new functions and meanings in combination with the increase of frequency of comme in Manitoban French leads to a facilitatory effect of this item in sentence processing of Manitoban French speakers in comparison to European French speakers.

To test these predictions, I adopted the design of the word-monitoring task (Experiment 1 and 2) of Fox Tree and Schrock (Reference Fox Tree and Schrock1999) in a strongly modified version. A spoken sentence was presented to the participants, followed by a semantically related or unrelated visual target word. The participants then performed a lexical decision task on the visual target word.

3.1 Overall design of the experimental investigation

All participants from both groups received the same stimuli in pseudorandomized order, which was determined by the experimental software Presentation (Neurobehavioral Systems Inc.). All participants received the same instructions. Error rates and response latencies are the dependent variables in the experiment. Language group (MF and EF) is included as an independent variable as a between-subjects and within-items factor. The statistical analysis consists of analyses of variance by participants (F1) and by items (F2).

Participants

Twenty-four undergraduate students and staff from the Université de Saint-Boniface (Winnipeg, Canada) participated in the experiment in exchange for payment as the Manitoban French experimental group (MF). Twenty-four undergraduate and graduate students from the Université de Strasbourg (Strasbourg, France) participated in the experiment in exchange for payment as the European French control group (EF). All participants were aged between 18 and 30 years.

I carried out a pre-test of the experiment with 24 students from the International Bilingual School (IBS) (Luynes, France) and undergraduate students from the Université de Provence (Aix-en-Provence, France).

MaterialFootnote 1

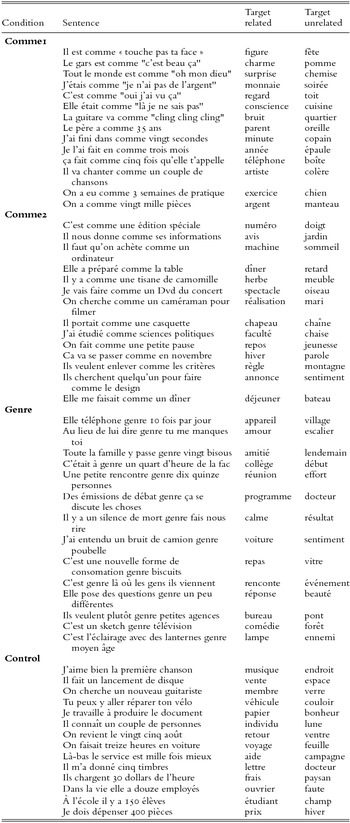

Seventy monolingual French sentences were taken from the transcriptions of natural speech data of the FM Corpus (Hennecke, Reference Hennecke2014), the C-Oral Rom Corpus and the Corpus de la Parole. The FM Corpus provided stimuli of spoken Manitoban French. The C-Oral Rom Corpus, a corpus of spontaneous spoken data of French, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian, as well as the Corpus de la Parole, a corpus of spoken European French, provided stimuli sentences for European French. The original sentences already contained the markers comme and genre in different functions. All sentences were matched in approximate length, varying from five to ten words. The sentences were arranged in four sets, depending on whether they contained the quotative and rounder function of comme restricted to Canadian French (comme1), the adaptor use of comme accepted in European French (comme2), the marker genre in quotative, rounder and adaptor functions (genre) or no marker at all (control). A female European French native speaker recorded all sentences in a quiet room with an Olympus voice recorder. A semantically related and a semantically non-related French target word was created for each sentence using Wordgen stimulus creation software (Duyck et al., Reference Duyck, Desmet, Verbeke and Brysbaert2004). The variable relatedness was included in the design as a control variable. Target words were matched as closely as possible in frequency and length. They were assigned to the respective stimuli sentences by means of the variable semantic relatedness. A set containing 70 Filler sentences and Filler words and non-words was created according to the same criteria as the experimental stimuli. Filler words were all matched in frequency, respectively bigram frequency. Filler words and non-words were randomly assigned to the respective Filler sentences. Filler sentences and Filler words were included in the design to obscure the aim of the study. The experiment was programmed using the experimental software Presentation (Neurobehavioral Systems Inc.). The sentences were presented orally on a Mac Os X, the target words were presented on a 13” screen. Two keys on the keyboard were used for button responses.

Design

The variables marker (comme1, comme2, genre, control) and relatedness (related, unrelated) were varied within participants. Each participant received 35 sentences with unrelated target words and 35 sentences with related target words as well as 70 Filler sentences with target words. The combination of the stimuli sentences and the target words is displayed in detail in Annex A. The combination of the variables marker and relatedness was counterbalanced within and between groups. All stimuli and sets of stimuli were pseudo-randomized using Presentation software and appeared in a different order for each participant. A short practice trial including three sentences and target words was presented to all participants at the beginning of the experiment.

Procedure

Participants were first introduced to the consent form and the experimental procedure in French. Furthermore, all participants were informed to listen carefully to the stimuli sentences in order to complete a short memory task at the end of the experiment. The visual memory task included five of the stimuli sentences and five sentences that were not part of the experiment. The participants had to decide if they heard the respective sentences in the experiment or not. They did so by checking a Yes- or a No-box on a sheet. Each trial started with the auditory presentation of a sentence, followed by the visual target word (see Figure 1). For each trial, participants performed a lexical decision by pressing a key on the keyboard, that is, they decided if the presented target word was a real word or a non-word.

Figure 1. Design of the sentence-word verification task.

Figure 2. Mean error rates in percent (participants’ means). Error bars represent one standard error.

3.2 Results

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (IBM). Statistical analyses were only performed on the stimuli trials. All trials including Filler sentences as well as non-words were excluded from the analyses. Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs) were run on subject and item means, including group (European French = EF, Manitoban French = MF) as a between-subject and within-items variable and the variables marker (comme1, comme2, genre, control) and relatedness (related, unrelated) as within-subjects and between-items variables. Response errors (Overall 1.2%) and response time deviations slower or shorter than 2.5 standard deviations from the participant mean (Overall 2.5%) were excluded from the analysis.

Error Rates

The overall error rate for this experiment was 1.9%. Error rates were higher for the MF group (2.7%) than for the EF group (1.1%). As a result, a main effect was found for the variable group in the by-participants analysis (F1 (1, 46) = 4.38, p < 0.05). In the item analysis, no main effect was found for the variable group (F2 (1, 72) = 1.24, p > 0.1). Error rates are displayed in Figure 3. The analysis of error rates revealed higher error rates for the unrelated condition (2.2%) than for the related-condition (1.4%). This is reflected in a significant effect in relatedness for MF participants (F1 (1, 23) = 4.59, p < 0.05). In contrast, no significant effect in the relatedness condition is found for EF participants. The control-condition yielded lower error rates (1.5%) than the overall of the other conditions (1.9%). Furthermore, error rates varied importantly for the MF group in the related- and unrelated-condition.

Figure 3. Mean reaction times (participants’ means) by group and marker. Error bars represent one standard error.

Response Latencies

Average response latencies are displayed in Figure 3. Results from the overall statistical analysis are displayed in Table 1 for the by-participants analysis and for the by-items analysis. Except in the comme1-condition in the related-condition, EF participants showed overall faster response latencies than MF participants. Overall means of response times were 22.5 ms faster for the control condition than for conditions including a pragmatic marker (mean control-condition = 574ms; mean other conditions = 596,5). That is to say, participants of both groups were faster in the control condition. Given that response latencies varied importantly, a significant effect was found for the marker condition in the by-participants analysis (F1 (3, 138) = 4.00, p < 0.01) that was not significant in the by-items analysis (F2 (3, 104) = 2.31, p = 0.08). Furthermore, a significant effect was found for the interaction between marker and relatedness in the by-participants analysis (F1 (3, 138) = 3.1, p < 0.05), which was not significant in the item analysis (F2 (3, 104) = 2, p = 0.11).

Table 1. Overall results from the statistical by-participants (F1) and by-items (F2) analysis. In the by-items analysis, the df2 = 104. Levels of significance are displayed with the F1 and F2 (*** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05).

EF participants showed overall faster response latencies, which shows a significant effect for group in the by-items analysis (F2 (1, 104) = 3.9, p < 0.05) that was not significant in the by-subjects analysis (F1 (1, 46) = .05, p = 0.83). No significant effect was found for the variable relatedness. The non-significance of the variable relatedness seems to be motivated by the varying nature of the comme1-condition in both groups. In a separate ANOVA, in which the comme1-condition was eliminated from the by-subjects analysis, response latencies were faster for the related condition than for the unrelated condition. Consequently, a significant effect was found for marker (F1 (2, 92) = 4.58, p = 0.01; F2 (2, 78) = 3.36, p < 0.05) as well as for relatedness (F1 (1, 46) = 11.25, p < 0.01; F2 (1, 78) = 5.6, p < 0.05).

To compare the comme1-condition to the other conditions, an exemplary ANOVA of the comme1- and comme2-condition was run. This analysis of variance showed inverse effects for comme1 in the interaction of marker and relatedness in comparison to the other condition. That is to say, comme1 showed slower response latencies in the related-condition than in the unrelated-condition. All other marker conditions showed faster response for the related than for the unrelated condition. As a consequence, the analysis revealed a near-significant effect for the interaction of marker and relatedness in the participant analysis (F1 (1, 46) = 3.75, p = 0.059), which approached significance in the item analysis (F2 (1, 52) = 3.1, p = 0.08). While EF participants were overall faster than MF participants, an inverse effect is found for the related-comme1-condition. This provoked a near-significant effect for the interaction of marker and group in the participant analysis (F1 (1, 46) = 3.94, p = 0.053), which was not significant in the item analysis (F2 (1, 52) =1.8, p = 0.19).

3.3 Discussion

The present experiment aimed to investigate two underlying aspects of sentence processing that are (1) the impact of the partial equivalent markers comme and genre on sentence processing, and (2) the impact of contact-induced change of comme on sentence processing. Considering the first question, the results indicate a main effect in the marker-condition. This impact and the comparison of the overall means show that the sentences containing a pragmatic marker are processed more slowly than the control condition. This is the case for all conditions; regardless of whether they contained pure hedging functions (condition comme2) or a mix of hedging and pragmatic functions (conditions comme1 and genre). This result is extremely important with regard to the concrete impact of pragmatic markers and hedges on sentence processing. Despite the very different nature, objective and respective languages of the tasks, the present results contradict the results of Liu and Fox Tree (Reference Liu and Fox Tree2012) to some extent. Liu and Fox Tree (Reference Liu and Fox Tree2012) conclude that like does not have an effect at all on memory tasks and that listeners may overlook hedge-marked information. The present results indicate that hedges and pragmatic markers may indeed have an effect on sentence processing in that sentences containing a pragmatic marker or a hedge are processed more slowly than sentences without a marker. This effect may have different reasons. First, the approximate nature of hedges triggers a loose reading (adaptor and quotative function) or an approximation on a scale (rounder function). Thus, this modification in the illocutionary force of the utterance may cause the hearer to require more processing time. In other words, the attenuation of the illocutionary force of the utterance may allow the hearer a larger scope of interpretation, which leads to higher costs in sentence processing.

A second possible interpretation of the results concerns the role of pragmatic markers and hedges in spoken language. These lexemes are still very restricted to informal speech and may be connected to a more negative attitude of the hearers towards the message (Blankenship and Holtgraves, Reference Blankenship and Holtgraves2005; Hosman and Siltanen, Reference Hosman and Siltanen2006). Sentences containing very informal speech may be perceived as rather inappropriate in a formal setting. Therefore, the comparatively formal experimental setting may have influenced the motivation of the participants and in consequence the response latencies. While the first explanation appears to be very plausible with regard to the results of the present experiment, this alternative possibility cannot be ruled out unequivocally.

The second underlying question of the present experiment concerns the impact of contact-induced language change on the processing of the marker comme. In this context, it is very striking that no main effect in the relatedness-condition is found in an overall by-participants analysis, but that a main effect is found when excluding condition comme1 from analysis. These results indicate that all participants were faster in the related than in the unrelated-condition for the marker conditions comme2, genre and control, but that a diverging effect is found for comme1.

In the comme1-condition, the related-condition provoked slower response latencies than the unrelated-condition and this tendency is particularly strong for the EF group. For a further explanation of this effect, it has to be highlighted again that it was generally assumed that the related-condition would motivate faster response latencies due to the semantic relatedness of the stimuli sentences and the target words. Opposed to this assumption, the results indicate a reverse effect for the EF group in the comme1-condition. This effect may indeed be explained by means of the impact of contact-induced language change and its related consequences. The functions of comme, included in the comme1-condition, are not attested in spoken European French. Therefore, three possible explanations can be provided for the results of the present experiment. First, the functions of comme in the comme1-condition are by far more frequent in Manitoban French than in European French. This may lead to a certain frequency effect, in that European French participants process these infrequent functions more slowly in the related-condition. Second, the diverging results mentioned above may be due to productivity. The functions of comme in the comme1-condition are not productive in European French, which may have hindered the overall processing of the respective sentences. A third explanation considers sentence processing as such, and more precisely sentence parsing. If sentence processing is an incremental process, then the comme1-condition may have triggered a certain garden path-effect in EF participants. This effect may be particularly strong in EF participants because the sentences of the comme1-condition may be perceived as semantically incorrect or even ungrammatical. Therefore, EF participants were possibly misled by the functions of comme in the comme1-condition and had to reinterpret the overall sentence meaning during processing. This effect may be particularly strong in the related-condition due to the semantic relatedness of the stimulus sentence and the respective target word.

The results of the present analysis do not allow the unequivocal ruling out of one of the above-named explanations. Still, it is very striking that a similar effect is not found for the genre-condition, which included the pragmatic marker genre that is absent in Manitoban French. This may be due to the fact that the pragmatic marker genre is a more recent item in informal spoken European French and is still clearly restricted to youth language. Therefore, even the EF participants may not be sufficiently familiar with these uses of genre, which may appear unusual in an experimental setting.

4. CONCLUSION

The present article aimed to analyse semantic and pragmatic representations of pragmatic markers by means of an experimental investigation. For this aim, the processing of different pragmatic functions and semantic meaning patterns of the partially equivalent French pragmatic markers comme and genre were compared in a monolingual sentence word verification task.

It can be concluded that the present experiment allows two interesting assumptions. First, hedges and pragmatic markers seem indeed to have an impact on sentence processing, in that they yield overall slower response latencies. This result may be explained by the fact that the functions and meanings, employed in the present experiment, all trigger a loose reading or an approximation on a scale. This ‘impreciseness’ may lead to more scope of interpretation in the hearer, which leads to slower processing times.

Furthermore, the present experiment indicates that the emergence of new functions of comme has an impact on the processing of these functions. Here, comme in newly emerged pragmatic functions yielded slower response latencies for EF speakers than for MF speakers. It has been pointed out that this effect may have different reasons. It cannot be stated unequivocally if the slower response latencies depend on frequency, productivity or even a certain garden path effect for EF speakers. This is due to the fact that in language change, frequency and productivity are not always clearly separable. It is not always possible to determine by means of diachronic data if a shift in productivity determined an increase in frequency or vice versa. Still, it was possible to prove that EF speakers and MF speakers process the marker comme in newly emerged functions very differently. It seems very likely to explain this effect with the contact-promoted language change of comme.

In conclusion, the fields of experimental pragmatics and applied psycholinguistics may offer important tools to investigate current theoretic questions on the semantic and conceptual representation of pragmatic markers as well as their impact on sentence and discourse processing.

APPENDIX A STIMULI USED IN THE SENTENCE-WORD VERIFICATION TASK