On 20 December 1663, the grand postelnic of Wallachia,Footnote 2 Constantine Cantacuzenus (1593–1663), was assassinated in the refectory of Snagov Monastery on the orders of the Wallachian Prince Gregory I Ghika (r. 1660–64 and 1672–3). The entire plot that led to this tragic event was orchestrated by a distant nephew of the postelnic, the vistier Dumitrașco (1620–86), and the boyar Stroe Leurdeanul (†1679), a member of the rival clan of the Băleni family, who allegedly forged documents that incriminated Constantine Cantacuzenus in the eyes of the Prince, presenting him as an agitator against the established rule.Footnote 3 While the history of the incident goes beyond the ‘hagiographical veil’ created by some narrative sources that took the grand postelnic's side on this matter, the death of Constantine had a profound impact on Wallachian society,Footnote 4 whilst its echoes reverberated within many of the literary productions of the age, such as the ‘History of the reign of Constantine Brâncoveanu’ by the logofăt Radu Greceanu († ante 1725), the official chronicler of the Wallachian ruler, or the anonymous ‘Chronicle of the Cantacuzins’.Footnote 5

Constantine Cantacuzenus was a member of one of the most – if not the most – illustrious families of Wallachia, which, at least according to the seventeenth-century eulogists, had its ancestry deeply rooted within the history of Byzantium.Footnote 6 Some claim that he was born in Wallachia in 1593, the son of Andronikos Cantacuzenus (1553–1601), grand treasurer under many Wallachian rulers, who in his turn was the son of Michael Șeitanoğlu Cantacuzenus (1515–78), one of the most influential and wealthy Greek archons of the Ottoman court.Footnote 7 However, Constantine himself became a very influential boyar and held important offices at the courts of the Wallachian and Moldavian rulers. He was held in high esteem by the voivode Matthew Basarab (r. 1632–54), during whose reign he became grand postelnic and personal counsellor to the Prince. Even so, his life and diplomatic career were not without political struggle. Because of his divergent views regarding the anti-Ottoman foreign strategies of Mihnea III (r. 1658–9), Constantine was forced to take refuge in Transylvania in August 1658, and afterwards in Moldavia. Denounced by Mihnea III at the Porte, Constantine was summoned by the Ottomans to answer the charges and was tried for cunning (hiclenie) – this was the official accusation forwarded by the Wallachian Prince.Footnote 8 He managed to secure his freedom with help from Panagiotis Nikousios (1613/21–73), the grand dragoman of the Ottoman Porte, and later became grand postelnic under Prince Gregory I Ghika, whose appointment to the Wallachian throne he was able to secure with the assistance of the same Nikousios and the grand vizier Köprülü Mehmed Pasha (c. 1656–61). With Prince Ghika, Constantine had a fruitful relationship until the plot against his life started to take shape.Footnote 9 The aftermath of his death led to open confrontations between the Cantacuzenus and Leurdeni clans. Nevertheless, the legacy of the grand postelnic survived through his children, especially Șerban Cantacuzenus (r. 1678–88), the future voivode of Wallachia, and Constantine Cantacuzenus (1639–1716), a humanist and official of the court, who left their mark on the intellectual life of Wallachia. Last but not least, Constantine's fame as a passionate bibliophile was renowned. He possessed the largest library in seventeenth-century Wallachia and early modern South-East Europe, which captivated the attention of many erudite individuals from both the Danubian Principalities and Constantinople.Footnote 10

Povéste de jale și pre scurt asupra nedreptei morți a prea cinstitului Costandin Cantacozino, marelui postélnic al Țării Rumânești (‘Short mournful story concerning the unjust death of the most honorable Constantine Cantacuzenus, Grand Postelnic of Wallachia’) tells the story of the demise of this official, and provides a first-hand account of his execution.Footnote 11 The original text was composed in Greek in decapentasyllables by a ‘very good and dear friend’ of Cantacuzenus (prea-bun și scumpu priiatnic al său), who claimed to be an eyewitness to the bloody event: ‘In this book I wrote as it all happened, | For, when they murdered him, I was there’ [v. 29–30].Footnote 12 Constantine Kaisarios Dapontes (1713–84), the Greek scholar and prolific chronicler, informs us that the text of the poem was published in Venice.Footnote 13 The logofăt Radu Greceanu, the official chronicler of the Wallachian Prince Constantine Brânconveanu (1654–1714), produced a translation into Romanian of the entire work and printed it at Snagov some time between 1696 and 1699.Footnote 14 He informs us that the original Greek text was printed at the expense of its author, while his translation into Romanian was dedicated to Stanca Cantacuzenus Brâncoveanu (1637–99), the daughter of the grand postelnic and the mother of the Wallachian ruler, Constantine Brâncoveanu:

With small and unworthy effort, as a sign of reverent and humble service, I dedicate [this work] to her, the most worthy lady Stanca Cantacuzenus, beloved daughter of the same late C[onstantine] C[antacuzenus], being also mother of our most wise and most Christian lord, John Constantine B[asarab] B[râncoveanu] voivode, lord and ruler of all Wallachia.Footnote 15

At present, no printed edition of the text has been located. The only version of the text that survives is preserved in an incomplete manuscript copy of the Romanian translation (BAR – Cluj, Ms. Fond Blaj 216, ff. 104r–113v), produced on 4 February 1735 [7243] by the logofăt Dumitru according to the printed edition by Greceanu;Footnote 16 this copy contains almost 485 verses.

Regarding the author of this text, Simonescu, the editor of the Romanian translation, considers that he is a certain contemporary individual, close to the party supporting the Cantacuzins, very well informed about the intricacies of the Wallachian politics of the age, especially on the development of the conflict that emerged against the Cantacuzins during the second half of the seventeenth century. Moreover, he states that because of the hatred that the author displays towards the Greek boyars of Wallachia, it is clear that ‘he was Romanian’ [read Wallachian].Footnote 17 Still, Simonescu was unable to identify the author by name.Footnote 18

The poem itself can be regarded as a description of a secular martyrdom, since the author is very explicit in portraying Cantacuzenus as the wise, God-loving, and just official, who has been caught in the webs of a conspiracy orchestrated by his opponents. According to the poem, Cantacuzenus’ adversaries are evil plotters, driven by their own avaricious agendas. Besides the information already mentioned regarding the authorship of the poem, nothing else is known to historiography. Still, new data extracted from a manuscript recently acquired by the Princeton University Library, Special Collections Department (Princeton gr. 112), may shed more light on the author of the original Greek version of the poem.

At some time between 1750 and 1780, Nicholas Karatzas (c. 1705–87),Footnote 19 a famous Phanariot scholar and official of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, passionate bibliophile and collector of manuscripts, with strong ties to the Wallachian milieu, compiled a Greek codex, which later on was suggestively given the title Saracenica by a nineteenth century scribal hand.Footnote 20 As this title reveals, the codex is a compilation of anti-Islamic polemical texts. The works are thirty in number, both Byzantine and early modern, which are authored, among others, by Euthymios Zigabenos (fl. 12th century), John Kantakouzenos (c. 1292–1383), Joseph Bryennios (1340/50–1431), Matthew Kigalas (1580–1640), Nektarios of Jerusalem (1602–76) and Meletios of Athens (1661–1714).Footnote 21Saracenica is quite an unusual work for the Greek milieu: no such compendium of anti-Islamic polemical literature had ever been produced before. In the West, scholars such as Theodore Bibliander (c. 1505–64), the Swiss reformer and Orientalist, and Friedrich Sylburg (1536–1596), the German Classicist, had already produced their anti-Islamic compilations in the sixteenth century, incorporating similar Greek polemical works to those later included in Karatzas’ Saracenica.Footnote 22 Although these large compilations are separated by decades, the Saracenica of Karatzas, with its large array of compiled polemical works, can be considered Bibliander's counterpart for the Greek milieu, as well as a richer continuation of Sylburg's endeavour.Footnote 23

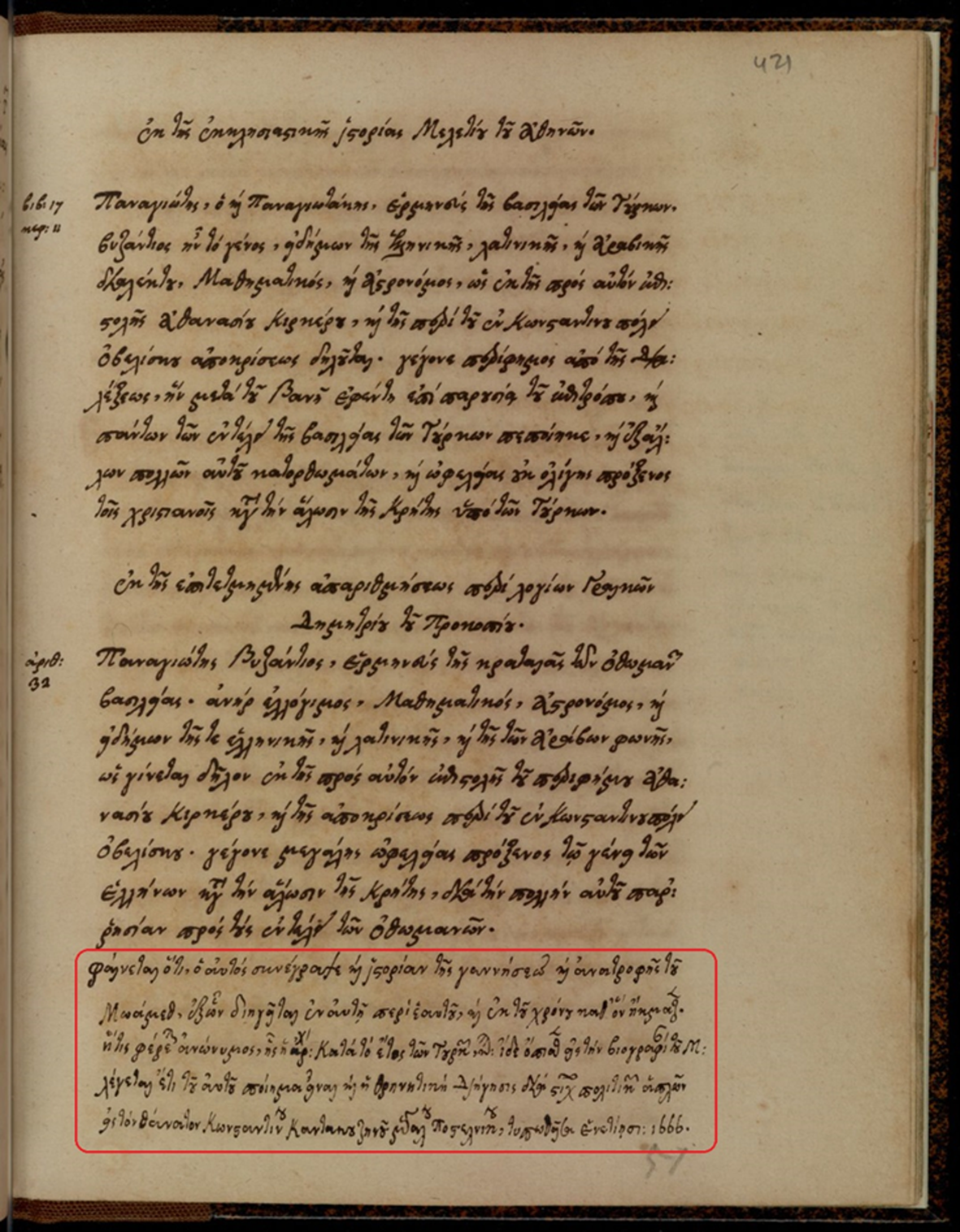

Text No. 25 of the Saracenica (ff. 422r–433r) is the famous Dialogue (Διάλɛξις) between the grand dragoman of the Ottoman Porte, Panagiotis Nikousios, and the leader of the Ottoman kadızādeli party, the learned Vani Efendi (d. 1685).Footnote 24 The importance of this text is paramount for the history of Christian-Muslim interaction and religious dialogue during the early modern period, as well as for the emergence of the confessional and ‘proto-national’ identities of the Greek communities from the seventeenth century onwards. Hence, the Dialogue benefits from the scholarly attention of Karatzas. The Phanariot scholar is known to historiography not only as a collector and compiler of manuscripts, but also as an editor displaying a form of ‘proto-encyclopedism’ for Greek intellectual life at the dawn of modernity. Beside scribal notes in the margins of the texts he was compiling, Karatzas’ editing style usually involved insertions of lists of works and details regarding the sources he was using, as well as providing explanatory excerpts from other early modern works regarding the author or the contexts of production for the main texts compiled in his codices.Footnote 25 In this regard, for the Dialogue between Panagiotis Nikousios and Vani Efendi, Karatzas provides his reader with two introductory excerpts concerning the author of the Dialogue: the first is from the Ἐκκλησιαστικὴ Ἱστορία of Meletios of Athens (Book 17, Chapter 11), and the second from the Brevis recensio eruditorum græcorum of Demetrios Prokopios of Moschopolis (end of 17th–beginning of the 18th centuries). Beneath these brief excerpts there is a scribal note by Karatzas himself (most probably written at a later date) that reads:

[f. 421r] Φαίνɛται ὅτι, ὁ αὐτὸς συνέγραψɛ καὶ ἱστορίαν τῆς γɛννήσɛως καὶ ἀνατροφῆς τοῦ Μωάμɛθ, ἐξ ὧν διηγɛῖται ἐν αὐτῇ πɛρὶ ἑαυτοῦ, καὶ ἐκ τοῦ χρόνου καθ’ ὃν ἤκμαζɛν ἥτις φέρɛται ἀνώνυμος, ἧς ἡ ἀρχή, κατὰ τὸ ἔτος τῶν Τουρκῶν ϡ́: ἴδɛ ὄπισθɛν ɛἰς τὴν βιογραφίαν τοῦ Μ[ωάμɛθ]. Λέγɛται ἔτι τοῦ αὐτοῦ ποίημα ɛἶναι καὶ ἡ θρηνητικὴ διήγησις διὰ στιχῶν πολιτικῶν ἁπλῶν ɛἰς τὸν θάνατον Κωνσταντίνου Καντακουζηνοῦ, μɛγάλου ποστɛλνίκου, τυπωθɛῖσα Ἐνɛτίῃσι, 1666.

It seems that he [Nikousios] also composed a work about the birth and upbringing of Muḥammad in which he narrates about himself and the time he flourished; the work is considered anonymous, and it begins [with the words]: in the Muslim year 900 [sic!], see above for the biography of M[uḥammad].Footnote 26 It is claimed that he is also the author of the Mournful Narration in simple political verse for the death of the grand postelnic Constantine Cantacuzenus, printed in Venice in 1666.

Given the information that we possessed so far on the author of the poem, these lines by Karatzas are quite illuminating. The Greek scholar informs his readers that the authorship of the poem on the death of the grand postelnic Constantine Cantacuzenus might be assigned to Panagiotis Nikousios, the Greek Ottoman grand dragoman, renowned for his scholarly interests and his influence upon the political affairs of the Ottoman Porte, as well as for the role he played within the political affairs of Wallachia and of the Patriarchate of Constantinople.Footnote 27 Although it is quite clear from Karatzas’ note that his information is most probably based on a rumour that may have circulated within contemporary erudite Phanariot circles, his reference to the author of the poem is unique. This being so, can Karatzas’ suggestion be accurate?

A closer look at the Romanian translation reveals that Nikousios is directly mentioned by name in connection with the grand postelnic:

They [Constantine and Dumitrașco] arrived at Constantinople, and later in the night they entered, | To the house of the dragoman they shortly went, | To Panagiotaki, I say, as you may have heard, | As to a good friend, to him they ventured, | Who is always quick to help the Christians. [v. 129–133]Footnote 28

Fig. 1. Nicholas Karatzas, Princeton gr. 112 [Saracenica], f. 421r © Princeton University Library

From this passage it seems that Constantine and Nikousios had a close friendship, a fact that might have contributed to Nikousios’ decision to write a poem on the death of his dear friend the grand postelnic of Wallachia. Secondly, as the text informs us, the Ottoman grand dragoman was an advocate before the Porte for the spiritual and administrative needs of the Orthodox. Nikousios was very aware of the entangled politics between the Ottomans and Wallachia during the second half of the seventeenth century, and therefore such an event that happened to somebody from his close circle could not have passed without him producing a record about it.Footnote 29 Thirdly, Karatzas’ mention of this poem between the lines of Saracenica can be easily corroborated with the information provided by Dapontes on the Greek text printed in Venice (see above, note 13). These two references are a clear indicator that the Greek text of the poem, in its Venetian edition of 1666, was known within the intellectual circles of the Greek-speaking world during the eighteenth century. The only difference between the two is that Karatzas also provides a name for the author (even if he is not completely sure of it). Most probably, Dapontes omits this information as it may have been either self-evident for the audience of his chronicle or because he actually did not know the author's name. Considering the information that Karatzas offers in his scribal note regarding this poem (he provides the title as well as the place and year of publication), it may be suggested that he had a copy of the Venetian edition in his own library. Moreover, it may be inferred that, most probably, this edition did not bear the name of the author on its title page, which may also explain why Dapontes did not provide the name of the author in his reference and why Radu Greceanu did not indicate the author in his Romanian translation.

At the same time, historians have also emphasized the close relationship between Gregory I Ghika, who ordered Constantine's assassination, and Panagiotis Nikousios. Păun pointed out that the Wallachian ruler was a close friend of the Ottoman dragoman,Footnote 30 a relationship validated by the testimony of the French ambassador in Vienna, the Catholic priest Jacques Bretel de Grémonville (1625–86).Footnote 31 It appears that Ghika was called by Nikousios ‘our Grigorașcu-Vodă’ (ὁ ἡμέτɛρος Γρηγοράσκος-Βόνδας), which emphasizes even more the close relationship between the two officials.Footnote 32 Moreover, it also seems that Nikousios advocated at the Ottoman court in order to assure Ghika's position in Wallachia, after the prince operated against the Ottomans. While in Constantinople, Ghika took shelter in Nikousios’ house before he received his pardon from the Ottomans.Footnote 33 So how could Nikousios be the author of an encomiastic poem describing the betrayal and death of his friend Constantine Cantacuzenus, and manage to have it published in Venice at his own expense, while he developed a close friendship with Ghika who ordered the assassination? Obviously, the answer to this question cannot be definitive. Nonetheless, I believe that it must begin with the preliminary remarks already mentioned in the beginning of this study and take into close consideration the circumstances of the preserved text and the political agendas of the people involved.

Since the original Greek version published in Venice in 1666 is apparently lost, and all that we possess so far is a Romanian translation by Radu Greceanu, which in its turn is preserved in a unique incomplete manuscript copy from Blaj, we cannot know for sure what the Greek text looked like. Furthermore, in the absence of a comparative study between the Greek version and its Romanian translation, we also cannot be sure about the accuracy of Radu Greceanu's translation or if this is a separate work on Cantacuzenus’ demise, independent of its Greek archetype. All we know for sure regarding the two editions is that the Romanian translation was ‘composed in verse, like the Greek one’ (tot în viersuri tocmită, asémene ca și cea grecească).Footnote 34 Moreover, the absence of printed editions poses even more problems, since we have no clue as to the accuracy of the logofăt Dumitru's transcription from the Romanian printed edition by Greceanu. Nevertheless, considering these gaps, we can mention two, or even three, different (completely or partially) variants of the same text: 1) the Greek edition (Venice 1666); 2) the Romanian edition (Snagov 1696/9); and 3) the manuscript copy of the Romanian edition (Blaj 1735). The existence of the Venetian edition would have enabled comparative philological research on Nikousios’ texts, which would have definitely helped scholars to make a decision regarding Karatzas’ note on the poem.

Considering the information that we have from the text of the poem itself, the so-called translation made by Greceanu is dedicated to Constantine Cantazuzenus’ daughter, Stanca Brâncoveanu, the mother of the then Wallachian ruler, Constantine Brâncoveanu. Given the features of this type of literary enterprise, its subject, and the laws of patronage, the author had by default to be very critical regarding Cantacuzenus’ enemies, as the grand postelnic was the grandfather of the prince. Bearing in mind the position that Greceanu held at Brâncoveanu's court (official chronicler between 1693 and 1714), even if we cannot be sure, it might be suggested that Greceanu might have adapted his translation of the poem from its Greek original in order to match his political agenda. Still, if these considerations are correct, it would mean that the Greek poem published in Venice, and presumably authored by Nikousios, may contain a slightly different text. At the same time, if Nikousios is the real author of the lost Greek text, his friendship with the Wallachian ruler may have been secured under the umbrella of anonymity, if we assume that the Venetian edition did not bear the dragoman's name on its title page. As for the reference to Nikousios himself within the poem, it is possible that either the grand dragoman created an alter ego when he speaks about the presence of Constantine Cantacuzenus in his house [v. 129–133] or that this is an insertion by its translator, Radu Greceanu. In the same manner, when the poem states that the author was present at the tragic event [v. 29–30], it might also be contended that the statement is a literary device inserted in order to provide authority for the whole literary enterprise.

With all these arguments in mind, alongside the assertions introduced by ‘if's and ‘might's, the possibility that Nikousios is the author of the original Greek version of the poem is considerable. His close friendship with the grand postelnic, as well as his erudition, varied scholarly interests, and knowledge of the ecclesiastical and secular politics of Wallachia, make him an excellent candidate for this literary endeavour. Karatzas’ mention of this work, which was thought to be anonymous so far, changes the status quo of the authorship debate. Besides being a worthy testimony concerning the circulation of the Venetian edition within erudite Greek-speaking circles, Karatzas’ paragraph contributes significantly to this scholarly discussion by mentioning Nikousios as the author of the poem. If the authorship of the poem may be attributed to Nikousios on the basis of Karatzas’ testimony, the historiographical panorama of the topic will become more complete, filling a large gap that existed for decades. Moreover, an awareness of the author's identity will enable scholars to undertake new interpretations of the text from the perspective of intellectual history and the relations between Wallachia and Ottoman Constantinople. Last but not least, one can only hope that the edition(s) of the text might be discovered somewhere within the libraries of Eastern and Western Europe. Indeed, such a discovery will have a decisive impact on the historiography of the problem and enable complete modern editions of the Greek original and the Romanian translation to be produced. Only then will we have a clearer idea regarding the relationship between the Greek text and its Romanian counterpart. As such, the ‘mournful story of the death of Constantine Cantacuzenus’ will occupy its rightful place within the intellectual history of South-East Europe.

Octavian-Adrian Negoiță is a doctoral candidate at the University of Bucharest, researching a thesis on ‘The anti-Islamic discourse as reflected in the Early Modern Greek apologetic and polemical literature (16th-18th centuries)’. He earned two MA degrees from the University of Bucharest (Medieval History in 2015) and the Central European University (Comparative History in 2017). He also holds two BA degrees (Theology in 2013 and Classical Philology in 2015), both awarded by the University of Bucharest. His research interests are anchored in the field of Christian-Muslim relations, with a special emphasis on the cultural and religious interactions in the medieval and early modern Mediterranean.