1. Introduction

The European Union (EU) is one of the biggest players in world trade and often exploits its commercial power as a diplomatic tool.Footnote 1 It has been argued that preferential access to the EU market, sometimes combined with financial aid and economic cooperation, is ‘the principal instrument of foreign policy for the EU’ (Sapir, Reference Sapir1998, 726).

The EU conducts its external relations, including trade relations, with the stated purpose of promoting its values. This goal has been made official in the Treaty of Lisbon, notably Article 21 (1), which states:

The Union's action on the international scene shall be guided by the principles which have inspired its own creation, development and enlargement, and which it seeks to advance in the wider world: democracy, the rule of law, the universality and indivisibility of human rights and fundamental freedoms, respect for human dignity, the principles of equality and solidarity, and respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter and international law.

Art. 21 (3) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) explicitly encompasses trade as part of the action of the EU ‘on the international scene’, and trade policy must consequently ‘be guided’ by EU values. For this reason, the EU often conditions preferential trade access to its market to the achievement of Non-Trade Policy Objectives (NTPOs), such as sustainable development, human rights, and good governance.Footnote 2 In response to increasing calls from the European Parliament and civil society, the new von der Leyen Commission has promised to strengthen the use of trade tools in support of such NTPOs.Footnote 3

The purpose of the paper is twofold. First, we systematically document the coverage of NTPOs across the main tools of EU preferential trade policy: trade agreements – which we distinguish between association and non-association agreements – and the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP). Second, we examine the extent to which the EU can use these trade policy instruments as a ‘carrot-and-stick’ mechanism to promote NTPOs in partner countries. It should be stressed that our goal is to examine whether the EU can potentially use conditionality in tariff preferences to promote NTPOs. We do not study outcomes, i.e., whether EU trade agreements and GSP programs actually have had any impact on such objectives.

To examine the coverage of NTPOs in trade agreements, we use data from the Design of Trade Agreements (DESTA) project. Because of differences in rationale and legal status, it is useful to group NTPOs according to their political and economic objectives. Political NTPOs include civil and political rights as well as security issues, whereas economic NTPOs encompass economic and social rights and environmental protection.Footnote 4

We show that political NTPOs related to human rights and security are more prevalent in association than in non-association agreements, and their coverage decreases with the size of the trading partner. This suggests that, when negotiating association agreements with neighboring countries, the EU is mostly driven by political motives: it offers preferential access to its market in exchange for close political co-operation (possibly towards future membership). Non-association agreements are instead more focused on economic NTPOs related to labor and environmental standards, and the coverage of these provisions increases with the size of the trading partner. This suggests that the inclusion of economic NTPOs in trade agreements is mostly driven by commercial motives and a desire by the EU to ensure a ‘level playing field’ between domestic producers and foreign competitors.

We also document the coverage of NTPOs in the GSP programs of the EU. Over the years, the EU has introduced in its GSP regulations provisions aimed at pursuing both political and economic NTPOs. These provisions make GSP eligibility conditional on respect of core principles set out in international conventions (e.g., on human rights, labor and environmental protection, fight against terrorism, and drug trafficking).

We then examine the extent to which the EU can use tariff preferences – in its trade agreements and GSP programs – as a ‘carrot-and-stick’ mechanism to incentivize trading partners and achieve NTPOs. We argue that tariff preferences offered through trade agreements are not an effective tool to promote compliance with NTPOs. The key reason for this ineffectiveness is that EU trade agreements are subject to the requirements imposed by Article XXIV of the GATT/WTO, which stipulates that member countries should eliminate tariffs and other restrictive measures on ‘substantially all the trade’. Given that tariffs must be eliminated reciprocally across the board, the EU cannot easily extend or restrict preferential access to its market to ‘reward good behavior’ or to ‘punish bad behavior’ on NTPOs.Footnote 5

In principle, the EU can trigger the ‘essential elements’ clause in case of severe NTPOs violations by a trading partner, leading to the suspension or termination of the trade agreement. However, this clause only applies to severe violations of political NTPOs (related to human rights, democracy, the rule of law, and security). Moreover, in the few cases in which the EU has activated the ‘essential elements’ clause, it has never suspended or terminated the agreement. This may partly be due to the fact that this ‘stick’ is too drastic: given the reciprocal nature of a trade agreement, its suspension or termination can be extremely costly, not only for the trading partner, but also for the EU.

When it comes to its GSP programs, we argue that the EU can more easily condition preferential access to its market to compliance with NTPOs by the trading partners. The key difference is that GSP preferences are offered on a unilateral basis, which affords more leeway in using conditionality by preference-granting countries.

The EU can reward GSP members that make progress towards NTPOs by offering lower tariffs and/or a broader product coverage (positive conditionality). For example, since 2014 the Philippines has been a beneficiary of the GSP+ program. This special incentive arrangement for Sustainable Development and Good Governance grants developing countries full removal of tariffs on two thirds of all product categories, conditional on their ratification of and compliance with core international conventions on human rights, labor, and environmental protection.Footnote 6

Conversely, in case of violations of NTPOs, the EU can punish the trading partner by suspending part or all of its GSP preferences (negative conditionality). For example, in 2010 the EU withdrew Sri Lanka from its GSP+ program. This decision was based on the findings of an investigation by the Commission that identified shortcomings in the implementation by Sri Lanka of three UN human rights conventions (the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Convention against Torture, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, respectively).

Although GSP programs can in principle be an effective tool to promote NTPOs in trading partners, the EU has only punished NTPO violations on a few occasions, mostly in the case of severe violations of human rights in small developing countries. Commercial motives may explain why similar violations in larger developing countries have not been punished. We argue that monitoring and implementation of GSP conditionalities would need to be more consistent and rules-based if the new EU Commission truly wanted to use trade policy to promote NTPOs.

In line with previous studies (see, e.g., Poletti and Sicurelli, Reference Poletti and Sicurelli2018; Meissner and Mckenzie, Reference Meissner and Mckenzie2018), our analysis suggests that EU trade policies are driven by two often conflicting goals: promoting European values and pursuing the commercial interests of EU members.

The paper is structured as follows. In Sections 2 and 3, we briefly trace the evolution of NTPO provisions in EU trade agreements and GSP programs, respectively. In Section 4, we focus on conditionality clauses in EU trade agreements and GSP programs, comparing the extent to which these trade tools can be used to promote NTPOs. Section 5 concludes.

2. NTPOs in EU Trade Agreements

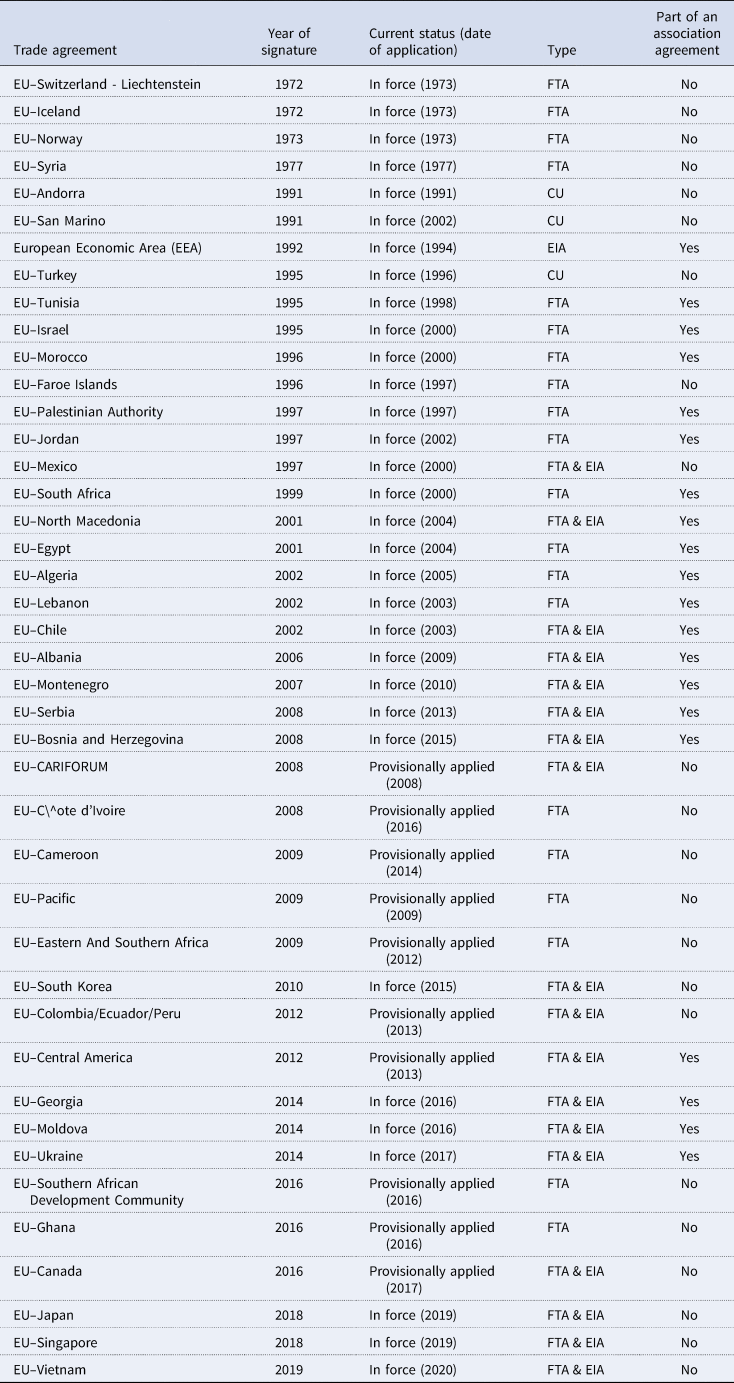

At present, the EU has in place the largest trade network in the world, with 42 trade agreements fully in force or provisionally applied.Footnote 7 These trade agreements are listed in Table A-1 in Appendix A.

All trade agreements covering goods are notified at the WTO under GATT Article XXIV and take the form of free trade agreements (FTAs), with the exception of the ones with Andorra, Turkey, and San Marino, which are customs unions.Footnote 8 Table A-1 also distinguishes whether these trade agreements are part of an association agreement.

Association agreements are a very important instrument used by the EU in its external policy, as they ‘establish a legal and institutional framework for the development of privileged relations involving close political and economic cooperation’ (Van Elsuwege and Chamon, Reference Van Elsuwege and Chamon2019, 9). The legal basis for association agreements is Article 217 TFEU. If a trade agreement is negotiated under this article, then throughout our analysis we classify it as an association agreement.Footnote 9

During recent decades, trade agreements have not only increased in number but have also become ‘deeper’. They often include provisions related to NTPOs. To describe the coverage of NTPOs in EU trade agreements, we use the dataset on their legalization constructed by Lechner (Reference Lechner2016) in the context of the Design of Trade Agreements (DESTA) project. The use of this dataset is motivated by two reasons. First, it provides nuanced measures of the coverage of NTPOs instead of simply coding whether or not they are included in an agreement. Second, the database covers a wide range of agreements, including the most recent ones.Footnote 10 While the degree of legalization is not a measure of enforcement per se, it captures variation in the degree of commitment towards NTPOs by the EU and its trading partners.

The concept of legalization, introduced by Abbott et al. (Reference Abbott, Keohane, Moravcsik, Slaughter and Snidal2000) and applied by Lechner (Reference Lechner2016) to NTPOs in trade agreements, is based on three criteria: obligation, precision, and delegation. Obligation refers to the extent to which trading partners make commitments indicating the intent to be legally bound. Precision refers to the degree to which the rules that define the conduct required, authorized, or proscribed for trading partners are unambiguous. Delegation measures to what extent third parties have been granted authority to implement, interpret, and apply the rules, to resolve disputes, and possibly make further rules. A legalization score is computed aggregating these three dimensions for each category of NTPOs. The score ranges from ‘ideal’ legalization, where the three dimensions are maximized, to the complete absence of legalization.Footnote 11

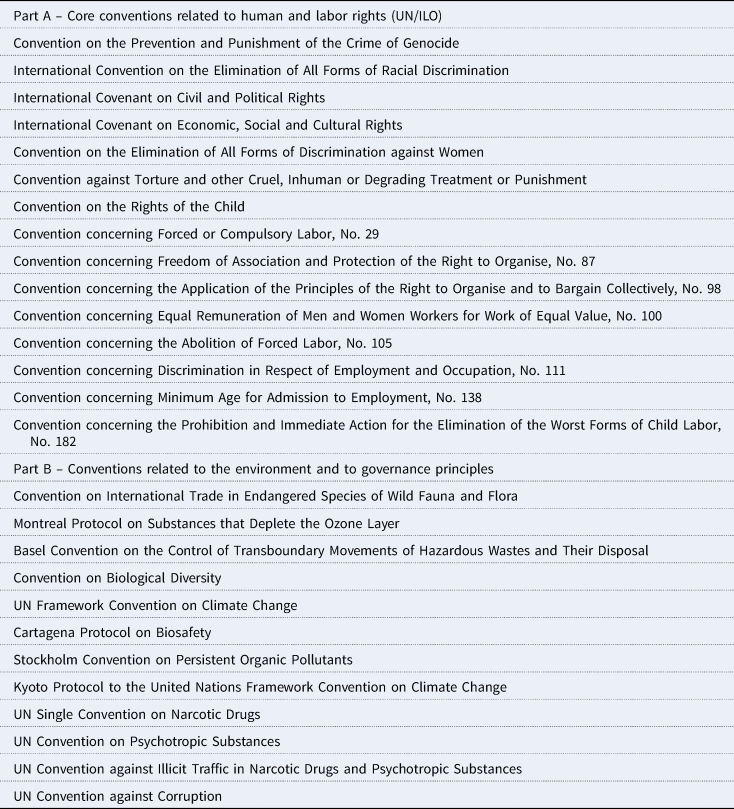

In Figure 1, we analyze the evolution of NTPOs in trade agreements negotiated by the EU over the last five decades, based on the overall legalization scores. The figure shows that NTPOs have gained prominence during the last two decades: all the agreements with the highest overall legalization scores (above 40) have all been signed after the Treaty of Lisbon (e.g. with Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine, Canada, Japan, and Vietnam).

Figure 1. Evolution of the legalization of NTPOs in EU trade agreements

Notes: Authors’ elaboration based on Lechner (Reference Lechner2016).

Combining Figure 1 and Table A-1, it is apparent that the highest legalization scores correspond to association agreements with small trading partners (e.g. Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine) as well as to FTAs with larger partners (e.g. Canada, Japan, Vietnam). To further explore the driving forces behind the high scores of these agreements, in Table 1 we decompose the overall score of each trade agreement by type of NTPOs and by type of agreement (association or non-association).

Table 1. Degree of legalization of NTPOs in EU trade agreements

Notes: Authors’ elaboration based on Lechner (Reference Lechner2016).

The most recent association and non-association agreements have similar overall legalization scores, yet the composition of these scores is different across the two types of agreements. In the case of association agreements, political NTPOs (civil and political rights and security issues) prevail. In the case of non-association agreements, the high overall legalization scores are mainly driven by economic NTPOs (economic and social rights and environmental protection). As discussed below, this systematic difference reflects different motives to negotiate trade agreements: the desire for close political co-operation (possibly towards future membership) is a key motive in association agreements, while market access is the primary rationale in non-association agreements.

In what follows, we provide more details about the heterogeneity in the coverage of political and economic NTPOs, respectively, in EU trade agreements.

2.1 Political NTPOs

As mentioned before, EU trade agreements cover NTPOs of a political nature, which encompass provisions related to civil and political rights (e.g., human rights, democracy, and the rule of law) and to security and peace (e.g., non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, combating terrorism, organized crime, and corruption).

Human rights, democracy, and the rule of law have been systematically considered as ‘essential elements’ of EU trade agreements since 1995. The non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) also has also constituted an ‘essential element’ of EU trade agreements since 2003, but on a less systematic basis.Footnote 12

The ‘essential elements’ clause is usually divided in two provisions. The first one presents the scope of the clause, describing the principles that the parties engage to abide by (e.g., human rights, democracy, the rule of law, non-proliferation of WMD). The second provision enables one party to take ‘appropriate measures’ in case the other party violates the ‘essential elements’ clause. The measures introduced should be proportional to the violation, and priority should be given to the ones that least disturb the normal operation of the agreement. However, in the case of a material breach – which consists of either the repudiation of the agreement not sanctioned by the general rules of international law or a particularly serious and substantial violation of an ‘essential element’ – the agreement can be terminated or suspended in whole or in part, based on Article 60 of the Vienna Convention. In certain agreements, the parties can also rely on the dispute settlement mechanism of the agreement to solve the issues that arise from the violation of the ‘essential elements’ clause.

The political nature of civil and political rights and peace and security issues is apparent from the way in which they are included in trade agreements. In the case of association agreements, where the political dialogue is joint with the trade agreement, the ‘essential elements’ clauses are usually mentioned in the general principles and/or in the political dialogue section, and apply to the whole agreement. Non-association agreements do not include the ‘essential elements’ clauses, but simply refer to the principles and values from the separate framework agreements.Footnote 13

Table 1 reveals that civil and political rights and security issues are much more important in association agreements compared to non-association agreements. The average legalization scores of civil and political rights in association agreements are more than double than those of non-association agreements (7.3 versus 3.2). The same is true for security issues, which are characterized by an average legalization of 6.9 in association agreements and 3.0 in non-association agreements.

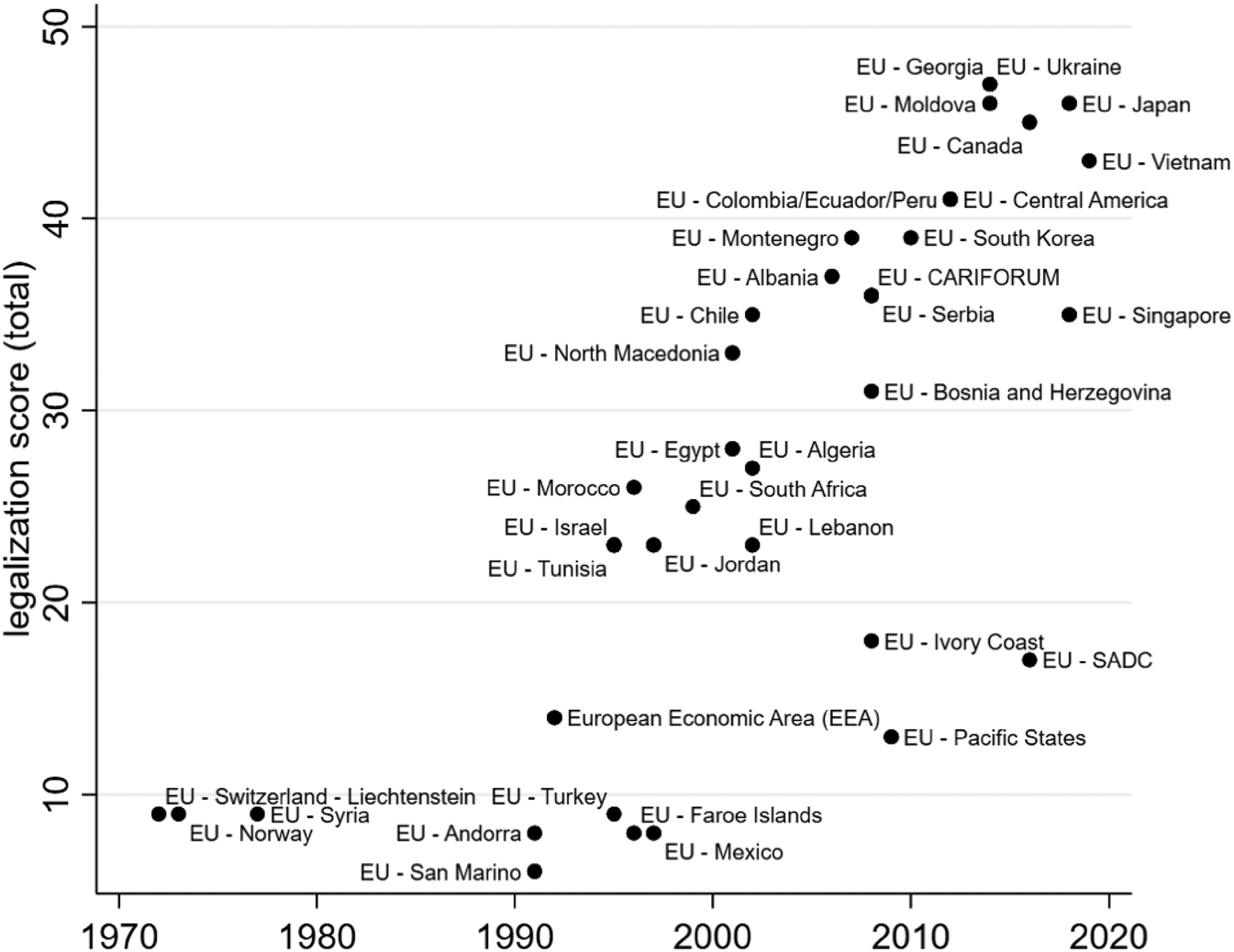

This distinction is further elucidated in Figure 2, in which we correlate the political legalization scores of association agreements (indicated with black dots) and other EU trade agreements (indicated with white squares) with the market size (log of GDP) of the trading partner.Footnote 14 The left-hand-side panel focuses on civil and political rights, while the right-hand-side panel looks at security issues.

Figure 2. Coverage of Political NTPOs in EU Trade Agreements and the Size of EU Trading Partners

Notes: Authors’ elaboration based on the legalization scores from Lechner (Reference Lechner2016) and GDP in constant 2010 US $ from the World Development Indicators dataset of the World Bank.

Both panels of Figure 2 show that legalization scores of political NTPOs are negatively correlated with market size of the agreement partner and this inverse relationship is driven by association agreements (clustered at the top left corner of each panel). This suggests that, when negotiating these agreements, the EU offers to small neighboring countries preferential access to its market in exchange for political cooperation and alignment.

2.2 Economic NTPOs

Economic NTPOs related to economic and social rights and environmental protection are usually bundled together under the umbrella of ‘trade and sustainable development’ (TSD).Footnote 15 Both association and non-association agreements concluded after the Treaty of Lisbon include TSD chapters. However, unlike political NTPOs, economic NTPOs do not currently constitute ‘essential elements’ of EU trade agreements. This may change, though, due to the increasing significance of environmental policy. Executive Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis, EU Commissioner for Trade, has recently suggested that the ‘Commission will propose the respect of the Paris climate commitments as an essential element in our future agreements’.Footnote 16

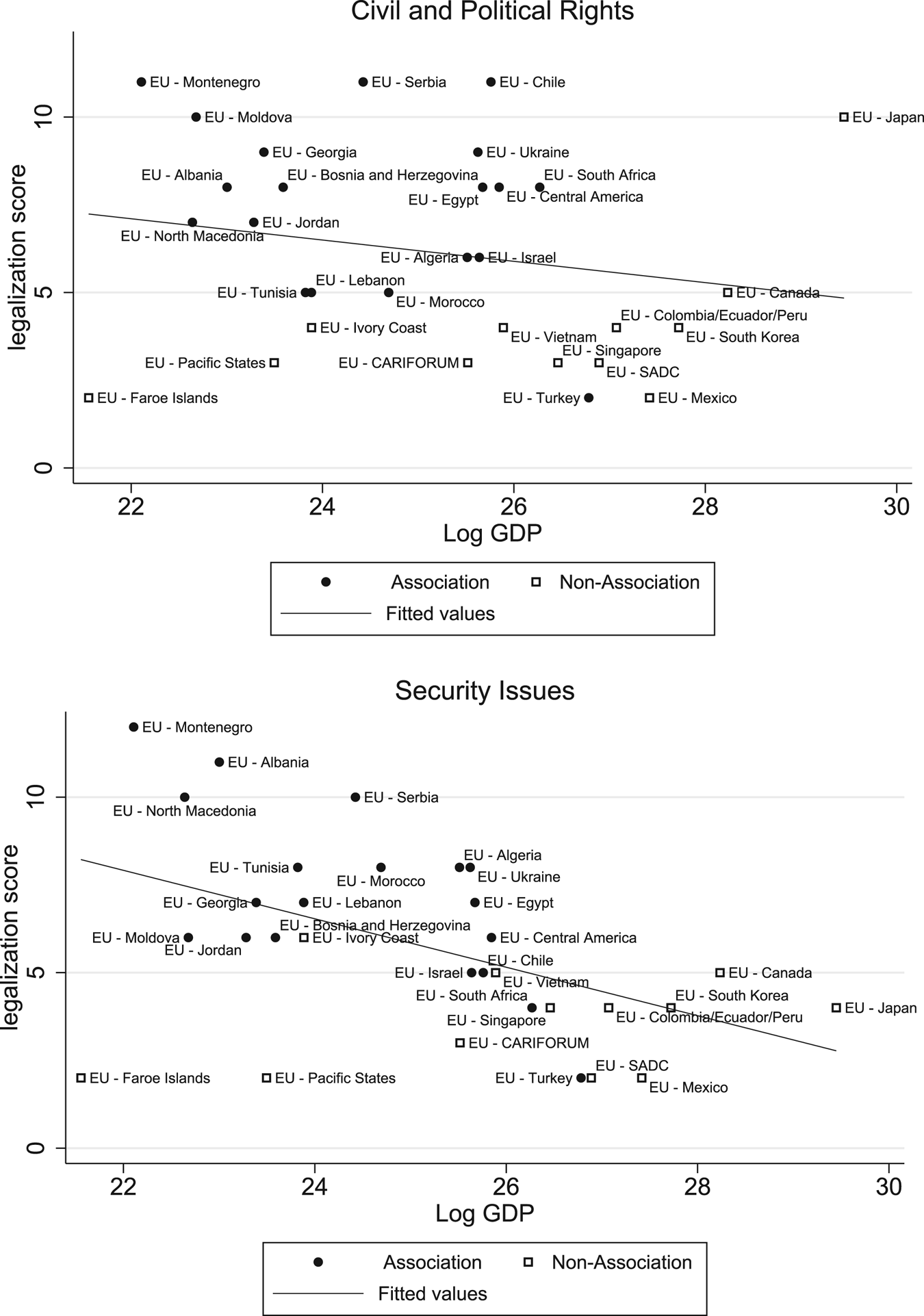

Table 1 shows that the legalization scores of economic and social rights and environmental protection are comparable between association and non-association agreements.Footnote 17

Similar to political NTPOs, the size of the trading partner is key to explaining the heterogeneity in the coverage of economic NTPOs across trade agreements. However, in the case of economic NTPOs, the relationship is positive. This can be seen from Figure 3, in which we correlate the legalization scores of economic and social rights (left panel) and environmental protection (right panel) with the market size of the agreement partner. These results suggest that commercial motives are behind the inclusion of economic NTPOs in trade agreements: when negotiating with larger trading partners, the EU pushes for higher labor and environmental standards to ensure a ‘level playing field’ between domestic producers and their foreign competitors.

Figure 3. Coverage of Economic NTPOs in EU Trade Agreements and the Size of EU Trading Partners

Notes: Authors’ elaboration based on the legalization scores from Lechner (Reference Lechner2016) and GDP in constant 2010 US$ from the World Development Indicators dataset of the World Bank.

3. NTPOs in the EU's Generalized Systems of Preferences

The Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) is an alternative policy tool through which the EU can grant preferential access to its market. In this section, we first describe briefly the evolution of EU GSP schemes before discussing in detail their coverage of NTPOs.

3.1 EU GSP Schemes

The legal basis for GSP schemes in the GATT/WTO system is the Enabling Clause of 1979.Footnote 18 This clause legalizes a positive, pro-development form of trade discrimination, as it allows donor countries to offer better than most-favored-nation (MFN) tariffs to developing countries without extending the same treatment to developed trade partners. The vague formulation of the Enabling Clause, in terms of countries and goods that should be eligible for preferences, allowed for a great deal of discretion on the side of preference-granting countries (Ornelas, Reference Ornelas2016), which often use GSP programs for their own political objectives (Grossman and Sykes, Reference Grossman and Sykes2005).

Most developed countries have set up their own GSP regimes.Footnote 19 Due to the unilateral nature of these programs, the EU and other granting countries can limit the set of beneficiary countries and/or the product coverage of their GSP schemes, respectively. For example, products such as clothing and footwear, which are considered sensitive on the part of donor countries and raise concerns among import-competing firms, are either excluded from the list of beneficiary sectors or receive lower trade preferences.

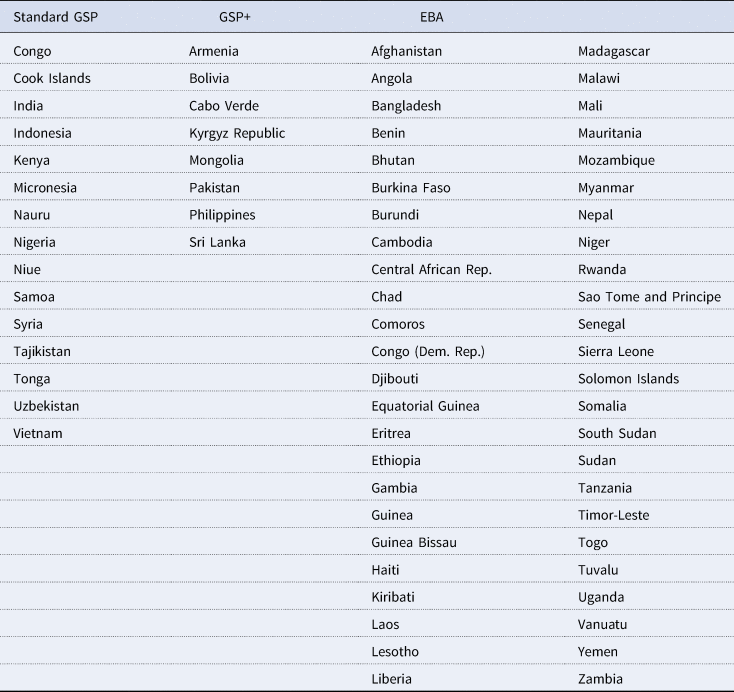

The EU's approach to its GSP scheme has evolved considerably over time, through three main reforms enacted in 1995, 2006, and 2014.Footnote 20 These reforms were aimed at rendering the scheme more predictable, stable, and targeted towards those countries most in need. As of today, the EU is operating three GSP programs, which grant different levels of access to the EU market: GSP, GSP+, and EBA. Table B-1 in the Appendix lists the current members of these programs.

The first is the standard GSP program, which is currently offered to 15 beneficiary countries, falling into the categories of low and lower-middle income countries as defined by the World Bank. Membership to the standard GSP program of the EU has changed considerably over time and is now at its lowest since the launch of the program. Countries in the standard EU GSP program benefit from lower than MFN tariff treatment or zero import duties on about 66% of the tariff lines applied by the EU.

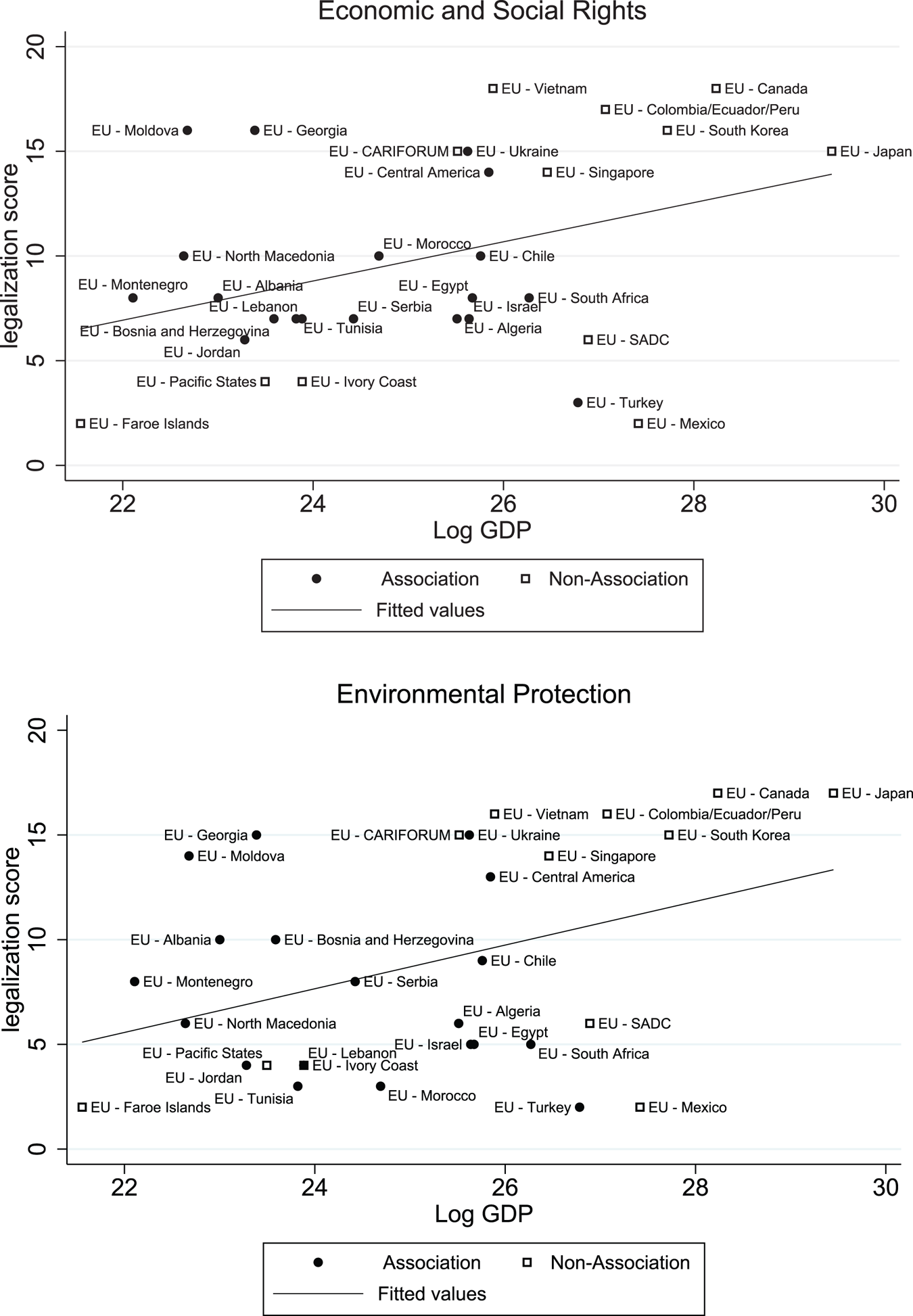

The second program is denoted as GSP+ and allows duty free imports of the vast majority of the products covered by the standard GSP.Footnote 21 The GSP+ program was introduced in 2006 and has currently eight members that have been considered eligible on the basis of their economic vulnerability (European Union, 2012).Footnote 22 As discussed below, beneficiaries under the GSP+ are granted additional preferences relative to standard GSP members in exchange for complying with a number of international conventions protecting human rights, the environment, and good governance. Table B-2 in the Appendix provides a list of these conventions.

Finally, the Everything-but-Arms (EBA) initiative introduced in 2001 grants the most far-reaching preferential treatment as it allows for duty-free imports of all products exported by the 48 Least Developed Countries (LDCs)Footnote 23 with the exception of arms and ammunitions.Footnote 24

3.2 NTPOs in EU GSP Schemes

Over the years, the EU has introduced in its GSP regulations several provisions aimed at pursuing NTPOs, making preferential access to its market conditional on compliance with these objectives. Table 2 summarizes the main reforms of the EU's GSP schemes and the gradual expansion of NTPOs in these schemes.

Table 2. Evolution of provisions related to NTPOs in the GSP Programs of the EU

One of the earliest examples in 1991 concerned security issues (European Union, 1990). To discourage the production of narcotic drugs and to stimulate planting of substitute crops, the EU granted additional trade preferences, in form of duty-free market access, to Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. In the following years, the EU expanded what was called the ‘drugs arrangement’ to Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, and Venezuela, justifying the extended preferential treatment granted to these additional countries with the intention of combating not only the production but also the trafficking of drugs (European Union, 1991).

The EU used the 1995 GSP reform to add further NTPOs to its GSP regulation, through two Special Incentive Arrangements addressing labor and environmental issues.Footnote 25 The first Arrangement was comprised of a set of provisions granting an additional preferential margin to beneficiaries that could prove to have adopted and applied domestically the International Labor Organization (ILO) conventions concerning the freedom of association, the protection of the right to organize and bargain collectively, and the convention concerning the minimum age for employment.Footnote 26

The second arrangement made available additional trade preferences to countries adhering to environmental standards laid down by the International Tropic Timber Organization (ITTO) relating to the sustainable management of forests (European Union, 1994). To obtain these additional trade preferences, written applications needed to be made to the European Commission (EC), with details about the domestic legislation incorporating the conventions and the measures taken to monitor their application. The EC could then decide whether to grant the trade preferences included in the Special Incentive Arrangement to the applicant country as a whole, or only to some sectors, if it considered that the conventions were effectively applied. Applications for the labor standards arrangement were filed by Georgia, Mongolia, Russia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Sri Lanka, and Moldova, but only the latter two countries were granted preferences.

In 2001, the addition of Pakistan to the drugs arrangement triggered the first reaction at the WTO about the discriminatory nature (amongst developing countries) of NTPO-related provisions in the EU GSP programs. India filed a complaint, which resulted in certain aspects of the ‘drugs arrangement’ being ruled to be WTO-inconsistent in the Appellate Body EC-Tariff Preferences report (Appellate Body, 2004).Footnote 27 The response of the EU was to rearrange all the NTPO provisions related to drugs, labor, and environmental provisions into the Special Arrangement for Sustainable Development and Good Governance, also known as the GSP+, a single arrangement treating jointly all the NTPOs in the GSP, which was introduced with the 2006 GSP reform.Footnote 28

Under GSP+, the EU offers duty-free market access on virtually all GSP eligible products to eligible countries that have ratified and applied a list of 27 international conventions on sustainable development and good governance. These 27 conventions broaden and deepen the range of NTPOs addressed in earlier GSP programs of the EU. Human rights and corruption were added to the areas covered by the previous scheme, and many additional provisions were included concerning labor rights, environmental protection, and security issues.Footnote 29

In its initial (2006) formulation, the list of 27 conventions was divided in two sub-lists of core and non-core conventions. GSP+ applicants needed to have ratified all of the 15 core conventions, relating to human and labor rights, and at least seven other conventions relating to environmental protection, drug production, and trafficking. In addition, countries needed to commit to having ratified all remaining conventions by 2008. This ratification requirement was amended in the 2009 version of the GSP+, which imposed the ratification of the entire set of 27 international conventions in order for a country to be eligible for GSP+ preferences. Importantly, similarly to the Special Incentive Arrangements in force pre-2006, GSP+ applicants need to maintain implementation of the conventions and accept regular monitoring and review of the status of such implementation (European Union, 2005, 2013a).

In 2006, the GSP+ scheme was offered for three years, and it was renewed in 2009 and 2014, with the latter reform setting the rules that currently apply until 2023. From the outset, fifteen countries joined the GSP+: the eleven original members of the drugs arrangement excluding Pakistan,Footnote 30 plus Moldova, Mongolia, Sri Lanka, and Georgia. In 2009, all GSP+ members re-applied for the scheme, except Panama, which failed to apply in time,Footnote 31 and Moldova, which had left the GSP program entirely because of signing a trade agreement with the EU. In addition, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Paraguay joined the list of beneficiaries (European Union, 2008). In 2014, Colombia, Honduras, and Nicaragua did not re-apply for the GSP+ scheme.

The 2014 GSP reform altered the eligibility criteria in the GSP+ scheme (European Union, 2012, 2014b), and also established that countries that have become part of alternative preferential trade agreements with the EU would lose their GSP benefits. For this latter reason, Costa Rica, Panama, Peru, and El Salvador were excluded from the GSP+ program in 2016 (European Union, 2014a) and Georgia in 2017 (European Union, 2015). Other countries instead joined the GSP+ scheme: Cape Verde and Pakistan in 2014, the Philippines in 2015, and Kyrgyzstan in 2016 (European Union, 2014c, 2016). Finally, Azerbaijan and Ecuador graduated from the GSP scheme altogether because they were classified as upper-middle income countries for three consecutive years by the World Bank.Footnote 32

4. Can Trade Conditionality Promote NTPOs?

As shown in previous sections, the EU has attempted over the past few decades to use its trade policy instruments to pursue various NTPOs, such as the fulfillment of social norms and the respect of environmental standards (Koch, Reference Koch2015).

In this section, we discuss whether the EU can promote NTPOs in its trading partners through positive and negative conditionality in its trade agreements and GSP schemes. According to Koch (Reference Koch2015), conditionality can be classified based on the leverage mechanism, which can be both punitive (negative) or rewarding (positive). Negative conditionality is related to the reduction, suspension, or termination of benefits when the conditions are not met within a relationship. Positive conditionality involves meeting requirements as a precondition for entering into a new relationship or granting additional benefits based upon performance or reform within an established relationship.

4.1 Conditionality in EU Trade Agreements

In this section, we discuss the extent to which the EU can use tariff preferences in trade agreements as a carrot-and-stick mechanism to promote NTPOs in its trading partners. Evidently, there is a range of other policies through which the EU can pursue NTPOs, particularly in its association agreements.Footnote 33 However, the reward offered for ‘good behavior’ and the punishment inflicted for ‘bad behavior’ do not involve trade policy (tariff preferences), but non-trade related policies (e.g., financial assistance, technical co-operation programs, prospects for EU membership), which are beyond the scope of this article.

As mentioned before, preferential trade agreements covering goods are regulated by GATT Article XXIV. All EU trade agreements are negotiated under this multilateral rule, which implies that trading partners have to ‘eliminate duties and other restrictive regulations of commerce with respect to substantially all trade in products originating in the constituents of the agreement’. As a result, positive conditionality through tariff preferences is very limited: once an agreement had entered into force and the tariffs on ‘substantially all’ trade have been eliminated, the EU cannot easily use trade preferences as a ‘carrot’ to incentivize trading partners’ respect of NTPOs. The only option is to extend preferences to cover excluded products. These products are typically those considered ‘sensitive’, so eliminating tariffs on them may be economically and politically costly for the EU.

It should be stressed that the EU could have some leverage before the entry into force of trade agreements, when it can decide not to pursue trade negotiations with countries that violate NTPOs. This could induce some countries to improve their domestic policies in order to be considered as potential partners in a trade agreement with the EU. However, the negotiation of the FTA with Singapore suggests that, when deciding whether to negotiate a trade agreement, the commercial interests of the EU may prevail over the pursuit of NTPOs. Singapore did not accept to sign an agreement that would have required a change in its position regarding the death penalty, human rights, or governance. The EU thus took a weaker stance on these issues, recognizing Singapore's human rights practices through a side letter to the agreement. Meissner and McKenzie (Reference Meissner and Mckenzie2018) argue that, in the case of the EU–Singapore agreement, the pure commercial interests of the EU prevailed over the promotion of its NTPOs. McKenzie and Meissner (Reference McKenzie and Meissner2020) point out that the case of the negotiations with Singapore ‘demonstrates the significant challenge the EU faces in fulfilling its strategic objectives and maintaining both its coherence and legitimacy as a political and trade actor as it negotiates trade agreements’ (p. 3).

Negative conditionality appears to be a more prominent feature of EU trade agreements. As previously stated, the ‘essential elements’ clause provides a mechanism through which the EU could sanction its trading partners. However, the EU has never actually used trade preferences to punish violations of NTPOs.Footnote 34

Several factors limit the ability of the EU to punish violations of NTPOs by its agreement partners. First, the ‘essential elements’ clause only covers political NTPOs (civil and political rights as well as security issues). Since the TSD provisions are not defined as ‘essential elements’, a violation of labor and/or environmental provisions could not justify the suspension or termination of the agreement in the event of a breach.Footnote 35

Second, triggering the ‘essential elements’ clause could entail significant commercial costs for the EU, particularly in the case of FTAs with large trading partners. Suspending or terminating these reciprocal trade agreements would increase both the cost of importing from and exporting to the FTA partner.

Third, since trading partners are at least formally on an equal footing, it is difficult to imagine that one of them could accept monitoring of its NTPOs from a peer. For instance, monitoring the respect of human rights does not involve habilitated organs to oversee the implementation of the various clauses (Bartels, Reference Bartels2013). Concerning the TSD chapters, monitoring involves several specialized bodies and tools that require input from civil society groups, but there are concerns regarding their engagement and power to address non-compliance with labor and environmental objectives (Marx et al., Reference Marx, Ebert, Hachez and Wouters2016).Footnote 36

Finally, if the EU did increase tariffs vis-à-vis an agreement partner, this policy may be challenged at the WTO. The EU could invoke the Vienna Convention to justify triggering the ‘essential elements’ clause of the trade agreement. However, WTO jurisprudence on GATT Article XXIV, and in particular the Appellate Body ruling in Turkey – Restrictions on Imports of Textile and Clothing Products, suggests that if the EU raised tariffs towards a partner country on the ground that it did not respect democratic principles and human rights, this policy might not be considered ‘necessary’ for the functioning of the agreement (Mavroidis, Reference Mavroidis2016).

4.2 Conditionality in the EU GSP Schemes

In this section, we examine whether EU GSP schemes can provide a ‘carrot-and-stick’ mechanism to reward ‘good behavior’ and punish ‘bad behavior’ in regard to NTPOs in developing countries. Our goal is thus to assess whether the EU's GSP system could be an effective tool to promote NTPOs in developing countries. This is different from assessing the effectiveness of its application so far, which is the focus of several earlier studies (Orbie and Tortell, Reference Orbie and Tortell2009; Beke and Hachez, Reference Beke and Hachez2015; Velluti, Reference Velluti2016).Footnote 37

Positive conditionality provisions abound in the EU's GSP schemes. Since the introduction of the first NTPO elements in its GSP regulations, the EU has always offered incentives to countries that comply with non-trade objectives, by way of a more preferential tariff treatment.

In the ‘drugs arrangement’ of 1991, the EU offered duty-free market access to compliant countries, thereby deepening the preferences that they had already obtained as GSP members. These extra trade preferences, however, were perceived as discriminatory among developing countries and as running counter to the principles established in the Enabling Clause. The WTO Appellate Body held that the ‘drugs arrangement’ was offered to a hand-picked list of beneficiaries, and did not establish any objective criteria that, if met, would have allowed other developing countries to be included as beneficiaries of the arrangement (Appellate Body, 2004).

The two ‘Special Incentive Arrangements’ introduced into the GSP regulation in 1995 also offered deeper-than-GSP trade preferences, in exchange for applying three ILO conventions on labor rights and adhering to certain environmental standards. In order to benefit from this form of conditionality, however, developing countries needed apply for it, which was unlike the ‘drugs arrangement’ whose members were selected by the EU.

The current and most complete instrument through which the EU applies positive conditionality is its GSP+ scheme. The GSP+ covers all the NTPOs jointly under the general concept of ‘sustainable development and good governance’ and offers developing countries lower tariffs in exchange for compliance with NTPOs.Footnote 38 To join the GSP+ scheme, developing countries must apply to the European Commission, which evaluates whether the applicant has ratified and applied the 27 international conventions.Footnote 39

Within the boundaries of WTO case law on non-discrimination amongst GSP beneficiaries, the EU GSP schemes thus provide ample leeway to reward developing countries that make efforts on NTPOs, which can gain better access to the EU market.

Negative conditionality is also pervasive and affects all three GSP programs (standard GSP, EBA, as well as GSP+), as the EU can withdraw GSP preferences from beneficiaries in case of violations of NTPOs.Footnote 40 A country might lose its standard GSP, GSP+, or EBA preferences for all or certain products either (i) following serious and systemic violation of the principles laid down in the ‘core conventions’ (Part A of Table B-2 in Appendix B), which are used as a basis for GSP+; or (ii) if a country exported products made by prison labor; or (iii) in case of serious shortcomings in custom controls on the export and transit of (illicit) drugs, or failures in compliance with international conventions on anti-terrorism and money-laundering.Footnote 41

With reference to point (i), recall from Section 3 that GSP+ members are required to have ratified and applied 27 international conventions when they join the program, including the core conventions related to human and labor rights. The same requirement does not apply to beneficiaries of the standard GSP and EBA programs. However, if a member of any of the three GSP programs violates the core conventions, the EU can revoke its tariff preferences.Footnote 42

If a violation is reported, the EU Commission carries out an investigation, consults the beneficiary concerned, and can eventually decide to suspend GSP preferences. Preference withdrawal is therefore a gradual process and is meant to allow the country to possibly remedy the alleged violation. If a decision about a suspension of preferences is finally made, it is initially for six months, after which the EU decides to either terminate or extend the suspension (European Union, 2012).

In addition to the aforementioned provisions, the GSP+ program has specific negative conditionality provisions. Within this program, the EU regularly monitors the status of implementation of the conventions by examining the conclusions and recommendations of the relevant monitoring bodies established under those conventions (European Union, 2012).Footnote 43 GSP+ preferences can be revoked if a country fails to ratify the necessary conventions, or to effectively implement them.

To the best of our knowledge, there have only been five instances in which the EU has sanctioned NTPO violations by GSP recipients. These are summarized in Table 3.Footnote 44

Table 3. EU sanctions following NTPO violations by GSP beneficiaries

There have been two cases of suspension of preferences granted under the standard GSP scheme, both occurring because of violations of labor standards. These cases concern Myanmar (currently an EBA member, but a GSP member at the time the sanction occurred) and Belarus (a standard GSP member). The EU sanctioned Myanmar in 1997, because of its use of forced labor, and then re-admitted the country into the GSP program in 2013 (European Union, 2013b). The sanction for Belarus occurred in 2007, as a consequence of the country's non-compliance with the Convention on freedom of assembly and collective bargaining (European Union, 2006).Footnote 45

Among GSP+ members, in 2010 Sri Lanka and Venezuela were ‘downgraded’ from GSP+ to standard GSP preferences. Sri Lanka was suspended from 2010 to 2017, because of its failure to implement effectively some of the conventions (European Union, 2009, 2010, 2017).Footnote 46 Venezuela was excluded from GSP+ due to its failure to ratify the UN convention against corruption.

Cambodia is the only country so far that has been suspended from EBA preferences. In February 2020, the EU decided to withdraw Cambodia's tariff preferences, due to serious and systematic violations of principles laid down in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. At the same time, to mitigate the socio-economic impacts of the preference withdrawal, and in consideration of the development needs of the country, the EU decided to remove tariff preferences only on certain products originating from Cambodia (EU Commission, 2020a,b).

It can be argued that the EU should have applied negative conditionality on more occasions and towards more GSP recipients. Indeed, European Commission (2017) reports many instances of ‘non-compliance on the ground’, including violations of human and labor rights reported in Bangladesh, Bolivia, China, Ethiopia, India, Pakistan, and Russia, which failed to trigger the negative conditionality provisions.

The EU usually justifies its limited use of negative conditionality with its policy of refraining from measures that can be harmful to a target population (Bartels, Reference Bartels2008; EU Council, 2012). A less altruistic explanation is linked to the commercial costs of punishing NTPO violations. Indeed, the EU has only applied negative GSP conditionality on small developing countries (e.g., Sri Lanka or Cambodia). When the violations have occurred in large developing countries (e.g., Pakistan or China), it has refrained from increasing tariffs as a punishment, possibly because this would have raised the cost of sourcing inputs from these countries, or for fear of retaliation in important export markets.

5. Conclusion

The EU is a pivotal player in international trade relations and its Treaties stipulate that the EU's external actions be conducted in a way so as to promote European principles and values, such as the respect for human rights and high labor and environmental standards.

In this paper, we have documented the coverage of NTPOs in the principal tools of EU trade policy: its trade agreements (association and non-association ones) and GSP programs (standard GSP, GSP+, and EBA). We have then examined the extent to which the EU could use these tools as a carrot-and-stick mechanism to promote NTPOs in trading partners.

When examining the coverage of NTPOs across EU trade agreements, we show that political NTPOs are more prevalent in agreements with smaller countries, and this result is mostly driven by association agreements (see Figure 2). In line with previous studies (e.g., Limão, Reference Limão2007), this finding suggests that the EU enters these agreements to offer small neighboring countries preferential access to its market, in exchange for political concessions (e.g., security cooperation, respect of human rights, and the rule of law). By contrast, economic NTPOs are more prevalent in trade agreements with larger countries (see Figure 3). This suggests that, when negotiating these agreements, the EU is mostly driven by commercial motives (improving access to the foreign markets, while guaranteeing a level playing field between domestic and foreign producers).

Both political and economic NTPOs are included in the GSP programs through which the EU offers preferential access to developing countries. In these programs, the EU's approach to NTPOs is more uniform than in the case of trade agreements. This may partly be due to the fact that multilateral trade rules and WTO case law limit the ability of the EU to discriminate across GSP beneficiaries.

We then discuss the extent to which the EU can use trade policy conditionality to effectively pursue NTPOs. Various studies have examined the enforceability of international agreements and whether linking trade and non-trade policy objectives can help to achieve more cooperation overall (Conconi and Perroni, Reference Conconi and Perroni2002; Limão, Reference Limão2005). These studies rely on the idea that trade policy can be used as a carrot-and-stick mechanism to enforce commitments in other policy areas. We come to a more nuanced conclusion. We argue that, within trade agreements, the EU cannot easily use trade policy conditionality to achieve non-trade objectives. This is partly due to the fact that multilateral trade rules limit the ability of the EU to reward trading partners (through lower tariffs) or punish them (through higher tariffs), depending on their behavior in relation to NTPOs. Under GATT Article XXIV, preferential trade agreements must eliminate ‘substantially all’ trade barriers amongst the signatories. Although what constitutes ‘substantially all’ trade is not precisely defined, neither in legal texts nor in case law, this article limits by design both positive and negative conditionality. As a result, once a trade agreement is concluded, it is difficult for the EU to use trade preferences as a carrot-and-stick mechanism to promote NTPOs.

The EU can have some leverage with trading partners before the entry into force of a trade agreement, since it can decide not to pursue negotiations with countries that violate NTPOs. At this stage, there might be incentives for third countries to improve their domestic policies in order to be considered as potential partners in a trade agreement with the EU. Some form of conditionality may also be possible after the entry into force of the agreement. In case of serious violations of human rights and security provisions, the EU could trigger the ‘essential elements’ and take ‘appropriate measures’ though it is legally unclear how much freedom the EU would have to increase tariffs vis-à-vis its agreement partners. Finally, non-trade policies (e.g., financial assistance or technical cooperation), which the EU can more easily offer to and take away from partner countries, may be more effective at promoting NTPOs within trade agreements.

When it comes to trade preferences offered under GSP schemes, we argue that they are a more flexible tool through which the EU could reward or punish trading partners in relation to NTPOs. GSP preferences are granted on a unilateral basis and – except for EBA preferences – do not extend to ‘substantially all trade’. The EU can thus reward countries that fulfill conditions related to NTPOs by granting them better GSP preferences (lower tariffs, on more products). GSP benefits can also be revoked, when trading partners do not fulfill these conditions. However, we point out that, if the EU wished to rely more on trade policy conditionality to promote such objectives, GSP schemes should be administered in a more consistent and rules-based way, with beneficiary countries being regularly monitored and their trade preferences being more systematically suspended or revoked in case of non-compliance with their NTPO commitments.

The new EU Commission under President von der Leyen has promised to strengthen the use of trade tools in support of NTPOs. Our paper suggests that commercial interests may inhibit the full pursuit of NTPOs in EU trade policy. The negotiations of the agreement with Singapore illustrate that the EU is at times willing to water down key values such as democracy, fundamental rights, and the rule of law in order to strike a commercial deal. Commercial interests also seem to affect the implementation of NTPO conditionality in GSP programs: although there have been many instances of severe violations of NTPOs in GSP beneficiaries, the EU has suspended trade preferences on very few occasions in which the violations have occurred in small developing countries, exempting larger countries from similar sanctions. In line with previous studies, our analysis suggests that EU trade policies reflect a tension between two often conflicting goals: promoting the principles and values of the EU and pursuing its commercial interests.

Appendix A

EU Trade Agreements

Table A-1. List of EU trade agreements notified to the WTO

Appendix B

GSP

Table B-1. List of GSP members

Table B-2. List of conventions to be ratified to be eligible for GSP+