In March 2018, Indranee Rajah, Singapore's Senior Minister of State for Law, announced a controversial decision: searches of female terror suspects would no longer be conducted by other women only. When believed to pose an imminent security threat, women suspected of terrorism could now be checked by any police officer on hand, male or female. According to Rajah, this policy reversal was justified given the “well-recorded history of the use of women in terror attacks,” which has been motivated by “a perceived unwillingness on the part of security officers to search women.”Footnote 1 To justify her ruling, she cited the spate of recent attacks conducted by Boko Haram as well as the idea that “Al-Qaeda repeatedly exploited a cultural taboo against the searching of women, allowing their female suicide bombers to pass through checkpoints without being searched.”Footnote 2 She acknowledged that such a lackadaisical approach toward potential female terror suspects could prove deadly.

Female suicide terrorism is both a domestic and a transnational issue. Such attacks have vexed US forces stationed in Iraq since the start of the Iraq War. According to Davis, more than 800 people were killed by female suicide bombers in Iraq within a decade of the invasion.Footnote 3 Female suicide attackers have been implicated in more than fifty successful attacks with a number directly targeting US forces.Footnote 4 In one high-profile case, a Belgian woman, Muriel Degauque, traveled to Baghdad to attack a US convoy in 2005. Scores of women have committed similar attacks across Iraq. In 2003, three US Marines were killed by female suicide attackers while manning a checkpoint. Five people died in a female-led attack on an American military office in 2005, followed by an attack on a US patrol the next month.Footnote 5

The increasing number of women used against US targets in Iraq could be explained by their relative ease in operating. Um al Harith, a would-be female suicide bomber, underscored this point when she revealed her planned suicide mission against US troops with her husband, remarking that “the guards just stare when a woman walks past, and they never search women. So I would go inside [the base] first wearing a suicide vest. And when they all gathered around me I would blow myself up.”Footnote 6 According to RAND analyst Farhana Ali, “women are able to shroud their weapons underneath their abayas, their Islamic dress … In doing so, they're becoming invisible and it's actually creating an enormous security problem for US and Iraqi forces.”Footnote 7 An official with the Iraqi Ministry of Interior acknowledged this, noting “there's a security gap, and [female attackers are] exploiting it well.”Footnote 8 The realization of this lapse in security protocols led to the creation of the Daughters of Iraq, a US-led security program training local women to circumvent suicide bombings by female operatives.Footnote 9 Allegations of large numbers of female suicide bombers being deployed during the battle of Mosul in 2017, however, have thrust Iraq's female suicide bomber problem back into the spotlight, suggesting it may not have ended with the introduction of that program.Footnote 10

Female suicide bombing appears to be a growing concern around the world. For example, Warner and Matfess note that between 2011 and 2017, Boko Haram utilized more women as suicide bombers than men.Footnote 11 Some estimates claim that more than two hundred women have attempted suicide bombings in Nigeria alone.Footnote 12 Globally, women have killed themselves in 214 suicide attacks across seventeen different countries between 1985 and 2015. Although this number represents a mere fraction (10%) of the total number of suicide attacks undertaken during this time, it remains surprising given the ubiquitous idea that women are victims and not perpetrators of violence. Female suicide bombers, however, have been directly responsible for more than 2,000 deaths over the last three decades and continue to threaten national security around the globe.Footnote 13 Why have so many terrorist organizations integrated female suicide terrorism into their tactical arsenals and what benefits has this choice provided? In this article, I suggest that a terrorist organization's use of female operatives in suicide missions is motivated by an expected boon in lethality of such attacks; organizations employ female attackers when they anticipate benefits from doing so. I argue that lax security protocols toward women, which are informed by societal gender stereotypes and norms, facilitate more lethal suicide attacks by female terrorists.

Although some research examines strategic motivations for women's participation in terrorism, much scholarship has focused on less deliberate reasons for gendered recruitment. For example, scholars suggest that terrorist organizations have recruited women to fill manpower shortages.Footnote 14 As a rationale for their inclusion of women in violent roles, a spiritual leader of Hamas offered that “women are like the reserve army—when there is a necessity, we use them.”Footnote 15 Women are also deployed as suicide bombers because they are viewed as expendable.Footnote 16 According to Warner and Matfess, one former member of Boko Haram reasoned that the group prefers female suicide bombers because “using women allows you to save your men.”Footnote 17

Several scholars also argue that female suicide terrorists are desirable because women martyrs have symbolic value. Attacks by women generate greater shock and awe than those by men and can be used to garner attention for a group's cause.Footnote 18 Women's participation has also been used to spur male recruitment.Footnote 19 Female sacrifice has been used to both shame and inspire men into participating in violence. A final argument, which is my focus here, suggests that women are recruited for terrorism because they provide organizations with practical benefits, which help terrorist organizations improve their operations and achieve important tactical goals.Footnote 20

Despite a significant body of work arguing for this female advantage in terrorism, scholars have largely failed to demonstrate that the use of male and female terrorists yields different outcomes, and even those that have, have not done so systematically.Footnote 21 Some case-specific research even appears to negate the idea that female terrorists are advantageous. For example, scholars have argued that in the Palestinian context, female bombers often fail to detonate their bombs,Footnote 22 while Warner and Matfess reveal that Boko Haram's female bombers may not contribute much to the group's lethality since so many of these attacks fail entirely or generate few fatalities.Footnote 23 Most importantly, studies have yet to test the theoretical mechanisms that link women to an advantage in terror or the argument's scope conditions. Specifically, while scholars have put forth the argument that gender stereotypes aid female terrorists, research has not examined whether the gender norms that undergird those tropes affect the lethality of female suicide terror attacks. This article attempts to overcome these shortcomings in the literature.

First, I offer a straightforward test examining whether female recruits provide tangible benefits to terrorist organizations by focusing on whether female suicide terrorists enhance mission success, defined here as attack lethality. A female advantage should be most apparent in acts of suicide terrorism since this tactic expressly relies on stealth and the ability of terrorists to gain intimate access to targets. I focus on whether female terrorists are able to generate more casualties than their male counterparts, given that most terrorists aim to carry out attacks with maximal destruction.Footnote 24

Second, while existing literature stops short at examining the differential impact of male and female terrorists, I examine whether female terrorists are expected to be deadlier in all societies or whether this effect is conditional upon a state's gender norms. I argue that security blind spots that facilitate female suicide terrorism are more likely in societies where stereotypes and expectations about female pacifism and apoliticism abound. As intimated by the Singaporean official, strong societal norms influence counterterrorism policies toward women. Using data on individual suicide attacks from 1989 to 2015, I find that the effect of an attacker's gender is conditional upon the gender norms of the state in which the attack occurs. The results show clearly that a female advantage is more apparent in only societies where a woman's role in public life is limited; attacks by female suicide attackers are more deadly in countries where women are largely absent from the workforce, civil society, and protest organizations. In more equal societies, however, there is no significant difference between the lethality of attacks executed by male and female terrorists. Finally, I assess whether counterterrorists eventually adapt to the use of female suicide terrorists. The results demonstrate that female attack lethality is declining with time, which suggests that security forces do eventually adapt to this strategy.

These findings contribute to a vibrant body of literature focusing on the role of women in the execution of violence. Most notably, this is the first study to articulate and test the argument that a female advantage with respect to suicide terrorism is conditional upon a state's gender norms. It also offers support to the existing literature asserting that female suicide terrorists perform differently than male terrorists. Consequently, it draws attention to the importance of examining gendered recruitment strategies to understand terrorist group behavior. More plainly, my research helps explain why women appear to be in high demand for terrorist organizations.

This article also contributes to the work on terrorist organization innovation. Previous studies find that terrorist organizations adopt suicide terrorism intentionally to remedy operational asymmetries between themselves and their enemies.Footnote 25 I suggest that some organizations have made further refinements to this innovation by including women as agents and have reaped substantial benefits from doing so. Similarly, this work contributes to the body of literature seeking to explain why some terrorist organizations are more deadly than othersFootnote 26 by showing that the gender of a suicide terrorist has a significant effect on the lethality of a given attack. These findings also have important policy implications. They support Cunningham's argument that studying female terrorism can enhance our understanding of terrorism more generally, and can help states improve upon their counterterrorism practices.Footnote 27

Strategic Logic of Female Suicide Attackers

Suicide terrorism is often a strategic response to asymmetries between terrorists and their targets.Footnote 28 Organizations adopt the tactic to remedy difficulties accessing specific types of enemy targets and to overcome limitations in their own military capabilities.Footnote 29 Suicide terrorism can offer weak groups leverage and therefore help them level the playing field with much stronger adversaries.Footnote 30 Given the low operational cost of suicide attacks and the potential damage such attacks can inflict, suicide terrorism can be a potent tool for terrorists.Footnote 31 Pape argues that contemporary terrorist campaigns often endeavor to achieve their political goals by imposing high costs on their enemies. In this case, death and destruction are the means to terrorists’ ends. Suicide terrorism is particularly suitable for accomplishing these objectives because it produces greater casualties than other types of violent tactics.Footnote 32 Research finds that suicide terrorism is more lethal and therefore more effective because it uses human bodies as a “precise guidance system” to increase the reliability and accuracy of attacks against vulnerable targets.Footnote 33 Further, Lewis proposes that “suicide bombing works so well [because] it gives the bomber the ability to adjust the exact location and timing of the detonation in real time so as to maximize casualties.”Footnote 34

Although suicide terrorism is intended to ameliorate terrorists’ operational challenges, the ease of executing suicide attacks is often taken for granted. Securing access to important targets, however, is no simple feat. Heymann argues that a terrorist organization is effective only if it can provide the means for an attacker to gain access to its target.Footnote 35 Similarly, Pape proffers that “for suicide attackers, gaining access is the only genuinely demanding part of an operation.”Footnote 36 Unlike more conventional tactics, the success of suicide terrorism relies on a terrorist's ability to get close to its target. If terrorists are denied access, they are denied the power to hurt their enemies and any resultant leverage that would be gained. Thus, terrorist organizations are often searching for ways to connect operatives to their marks.

Terrorists have instituted creative measures to address the inherent difficulties in launching successful attacks.Footnote 37 Some groups recruit selectively, choosing to employ more well-trained operatives believing that rigorous training will increase the probability of success.Footnote 38 Others select more intellectually able recruits for their ability to plan and execute sophisticated attacks.Footnote 39 Terrorists have also attempted to gain access to targets by deploying operatives who do not fit the typical “terrorist profile.” Some religious suicide terrorists have been known to dress in secular western-style clothing with shaved beards in order to evade detection and avoid scrutiny.Footnote 40 Palestinian terrorists have also attempted to pass as Israeli in order to get closer to enemy targets.Footnote 41 Other organizations, such as Boko Haram and ISIS, have recruited grade-school-aged children because of the presumed innocence of young children. A subset of groups utilize women to solve the access issue because like children, women are generally considered to be harmless.Footnote 42

Male terrorists have disguised themselves as women to get closer to targets or evade enemies,Footnote 43 since women are typically considered guiltless and their clothes can be useful for enshrouding munitions. While security experts search for “a young man, sweating profusely, looking around furtively, carrying a rucksack or wearing bulky clothing,”Footnote 44 women are often able to pass easily without drawing suspicion.Footnote 45 In 2017, a man killed fourteen people while cloaked in a woman's robe in Iraq.Footnote 46 Before that, in 2015, a man in Chad dressed in a woman's Burqa and killed fifteen people.Footnote 47 For similar reasons, organizations have used women as decoys and shields to escape scrutiny.Footnote 48 Some groups go so far as to employ female recruits to engage in suicide attacks because women often fail to register as terrorists and therefore are more likely to be granted unfettered access to important targets. Thus, using female operatives can benefit terrorist organizations by solving the “access issue” and can increase the success of attacks.

Utilizing women to perpetrate suicide attacks can be considered an innovation for terrorist organizations.Footnote 49 Organizations make strategic decisions to employ women for violence after weighing both the potential costs and benefits of their inclusion.Footnote 50 While some organizations never employ female terrorists, others diversify their recruitment because doing so affords them substantial advantages. For example, Palestinian terrorist groups began recruiting female suicide bombers in response to difficulties infiltrating Israeli checkpoints and avoiding Israel's crackdowns during the Second Intifada.Footnote 51 Female suicide bombers paid out significant dividends for Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, the first Palestinian group to integrate women into suicide operations.Footnote 52 The Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), which began recruiting women in 2003, reportedly believed it would facilitate the organization's missions.Footnote 53 Hamas, which had previously rejected female recruits, also began employing women in 2004 to skirt Israeli security.Footnote 54 The group described this change in their recruitment strategy as a “significant evolution.”Footnote 55 Because of the unique benefits expected to accrue to female operatives, three-quarters of the Kurdistan Workers Party's (PKK) suicide attackers and two-thirds of the Chechen bombers have been female. A quarter of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam's (LTTE) and almost half (45%) of the Syrian Socialist National Party's (SSNP) suicide attackers have also been women.Footnote 56

Female suicide bombers have been called the “ultimate asymmetric weapon” because of their ability to reach their targets undetected.Footnote 57 Gender stereotypes intimating that women do not engage in violence enable female terrorists to surprise their targets, leaving them defenseless. Female terrorists have been able to break into prisons, cross security checkpoints, and carry out assassinations against high-level politicians because of gender stereotypes that typecast women as innocent, nonthreatening, and harmless.Footnote 58 Women's success as suicide attackers, therefore, is a result of their targets’ shortsightedness.Footnote 59 According to Cunningham, “one of the most significant advantages held by female terrorists is that their potential is denied, ignored, and diminished and as a result they are almost always unanticipated, underestimated, and highly effective.”Footnote 60

Depictions of terrorists as “mad, male, minor and Muslim,” overlook the possibility that terrorists can also be female (or secular or elderly).Footnote 61 These ideas are especially problematic when they influence states’ counterterrorism policies. For example, if security officials believe that women are never terrorists, subjecting them to the same scrutiny as potential suspects is unnecessary. As a result, security protocols tend to be lax when applied to females.Footnote 62 Hamas's first suicide attack with a female operative underscores this point. In 2004, a female suicide bomber, Reem Riyashi, allegedly “tricked soldiers” at an Israeli checkpoint by convincing them she could not pass through a metal detector because of a metal implant.Footnote 63 While waiting for a female security officer to search her, she was able to slip into the secured building and detonate explosives, killing four people. It is hard to imagine that a male bomber would have been able to circumvent a metal detector so easily, and even more unbelievable that he would have been able to get away from security forces after the first encounter.

Recently, four Nigerian female terrorists were able to kill two people in an attack on a local official. Young girls knocking at a politician's door failed to trigger alarm, even in the area hit hardest by Boko Haram's campaign of terror.Footnote 64 Strong gender stereotypes also explain why two female suicide bombers were able to attack Iraqi soldiers by hiding among a group of women and children fleeing Mosul in July 2017.Footnote 65 More precisely, the persistent trope of women as harmless civilians likely enabled the female attackers to evade suspicion in this case and in the high-profile assassination of Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1991. In the latter case, a Tamil woman, Thenmozhi Rajaratnam, was able to get close enough to Gandhi to touch his feet and subsequently detonate a bomb, despite security protocols in place. Fifteen people were killed in that attack.

This argument implies that all female terrorists are likely to gain the same benefit from being women. Since women, writ large, are often considered to be pacific, innocent, and nonviolent, they are unlikely to be associated with violent political acts.Footnote 66 This benefit of doubt operates even when women are complicit in violence, and should translate into increased access to targets for female terrorists. If proximity to one's target is necessary to generate fatalities, the lack of attention given to women should result in more deadly attacks when terrorists are female. In particular, since female suicide terrorists are able to get closer to their targets, attacks by female assailants should generate a greater number of fatalities than those executed by males. This argument is consistent with research linking the effectiveness and severity of a suicide attack to an attacker's ability to access its target.Footnote 67 Because many terrorist organizations began recruiting women to address male terrorists’ difficulties accessing targets, women should also be expected to hit their marks more often. Conversely, because male terrorists are more likely to be intercepted before they reach their targets, they may be less likely to complete their missions, kill their targets, reach populated areas which would generate massive casualties, or detonate their bombs at all. As a result, I hypothesize the following:

H1 Suicide attacks committed by female terrorists are more lethal than those committed by male terrorists.

Gender stereotypes are most likely to facilitate terrorist agendas in areas where traditional norms avert suspicion of women's complicity in terrorism.Footnote 68 Although gender stereotypes are present in most societies, ideas about women's pacifism and innocence are likely to be stronger where gender norms are conservative and more specifically, where women participate in activities outside of the home infrequently. According to Baldez, conventional “gender norms tend to define women as political outsiders, as inherently nonpolitical or apolitical.”Footnote 69 When it is believed that women do not engage in traditional political and social affairs, it is reasonable to assume that they also do not engage in violent political activities, including terrorism. Although there is no direct link between traditional political activity and subversive activity, presumptions about what women are likely to do should be informed by what they actually do. If widely accepted convention relegates women to the domestic sphere, security forces and ordinary citizens are less likely to perceive women as politically active or dangerous. This is where benefits are most likely to accrue to female terrorists.

Stereotypical views of women, which are often transmitted through a society's gender norms, can hamper normal procedures that root out potential assailants. Not only do these norms affect security forces’ threat perception, they may also prevent security operatives from searching, detaining, and interrogating women when they are suspected, impeding their ability to suppress terrorist attacks. For example, Gonzalez-Perez suggests that female Tamil bombers were more effective than male bombers because the contrast between the practice of terrorism and traditional gender norms was so stark.Footnote 70

Especially in states where women's modesty is esteemed, security forces are less likely to search women and unlikely to do so rigorously. This facilitates suicide missions by enabling women to obscure explosive belts without fear that they will be detected. Terrorists have also exploited the association between motherhood and innocence by deploying expectant mothers or women pretending to be pregnant in suicide attacks.Footnote 71 Pregnancy, feigned or real, allows female terrorists to conceal vests, belts, and other equipment needed to carry out attacks. Some scholars suggest that pregnancy may further discourage frisks, providing female terrorists greater cover.Footnote 72 The first female suicide attacker dispatched by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), Zeynep Kinaci, concealed her explosive belt by faking pregnancy to ensure she would pass through security checkpoints with ease.Footnote 73 Relatedly, female suicide attackers have used their status as mothers to gain access to their targets. In January 2017, two Nigerian female suicide bombers were able to bypass a security checkpoint because they were carrying infants, while two other female terrorists without babies were detained.Footnote 74 The former two were able to generate casualties, while the latter two failed. The decision to leverage the stereotype of “maternal pacifism” was likely intentional.Footnote 75

Societal gender norms allow counterterrorists to overlook women's potential for violence, while incredulity that women can and do engage in violence enables terrorist organizations to succeed. This second argument suggests that female terrorists are likely to have an edge in only those places where beliefs about female innocence and victimhood are deeply entrenched and where women are unlikely to be active in public life. In countries with restrictive gender norms, women should have an easier time passing through secured checkpoints or blending into crowds, since they will not elicit concern from security forces or ordinary citizens. This should afford them greater access to their targets and produce more destructive terror attacks. Thus, I propose the following hypothesis:

H2 Suicide attacks committed by female terrorists are more lethal than those committed by male terrorists in societies with more conservative gender norms.

Although female suicide attackers should provide a net benefit to terrorist organizations, some skepticism exists, even among terrorists. Speaking of female suicide bombers, one Palestinian terrorist exclaimed that, “there is no need for them, there are many men to do the work,”Footnote 76 suggesting perhaps that the contributions of female suicide bombers are not valued as highly as that of male terrorists. Schweitzer's interviews with male Palestinian terrorists echo a similar sentiment.Footnote 77 Additionally, Berko argues that even if female suicide terrorists are able to infiltrate checkpoints, their missions are more likely to fail because they often hesitate or change their minds.Footnote 78 Some analysts argued that the 2002 Chechen attack on the Dubrovka Theater failed, in part, because the female bombers faltered when it was time to detonate their bombs.Footnote 79 These narratives push against the idea that female suicide bombers provide tactical benefits and suggest instead that female recruits may be liabilities for groups. If so, the inclusion of women will not have a significant impact on the lethality of suicide missions. In what follows, I address this empirical question.

Research Design

To date, only two other studies have examined the lethality of suicide bombers by gender, yet neither provides a comprehensive test of this question. Campbell examines the relative lethality of female suicide attackers in Sri Lanka and Chechnya, while O'Rourke focuses on those and three additional cases: Palestine, Lebanon, and Turkey.Footnote 80 Both studies focus on only high-profile cases where women are known to participate in suicide terrorism often. Such a design excludes less sensational cases where women engage in suicide terrorism less frequently and with less success, and any countries where female suicide bombers are not utilized. The latter makes a comparison between cases with female operatives and those without them difficult.

I attempt to overcome these difficulties by examining how the gender of the perpetrator(s) affects the lethality of individual suicide attacks in a global sample, including countries where female suicide bombers are prevalent as well as where they are not. I utilize the Chicago Project on Security and Threats, Suicide Attack Database (CPOST-SAD), which records the universe of suicide attacks since 1982, worldwide.Footnote 81 The inclusion criteria for suicide incidents in this database are that attacks must be led by a nonstate actor, and although no other casualties are required, the attacker must kill themselves. If attackers are killed by someone else (including security forces or another terrorist), the attack is not included. Finally, the CPOST-SAD requires two independent sources to corroborate reports of a potential suicide attack. The present sample includes suicide attacks between 1985 and 2015.Footnote 82 The unit of analysis for this study is the suicide attack.

Dependent Variable

The main dependent variable, number killed, measures the lethality of a given attack by counting the number of resulting casualties. Lethality is one way to gauge whether female recruits provide benefits to terrorists, since contemporary terrorist organizations often seek to execute maximally destructive attacks. The number of individuals killed in a single suicide attack ranges from 0 to 213.Footnote 83

These data include only “successful” cases of suicide terrorism, or cases where terrorists actually carry out their mission of committing suicide. That is, the proceeding analysis examines only whether attacks executed by female terrorists result in a greater number of casualties after an assailant is able to conduct an attack. These data are unable to reveal, however, if women are as likely as men to launch successful operations in the first place. To make a full assessment of female attackers’ ability to provide terrorists with an advantage, one must also consider how gender influences the success or failure of an attack. I address this question in detail.

Independent Variable

The main independent variable, female attacker(s), is a dichotomous indicator that records the perceived gender of the attacker and is coded 1 if the attack includes a terrorist that is believed to be female, 0 if the attack does not include a female terrorist, and coded missing when the gender of the attacker is unknown.Footnote 84 Although the CPOST data set includes over 5,000 suicide attacks, information on the gender of the attacker is available for only slightly fewer than 2,500 attacks.Footnote 85 This is unsurprising given the difficulty of gathering identifying information on perpetrators of successful suicide attacks. Female attackers were present in 9 percent (214 of 2,439) of the attacks between 1985 and 2015, where the gender of the attacker is noted. Since the data are coded at the level of the attack, female attacker(s) includes cases where female terrorists participate in team attacks with other terrorists, both male and female. One hundred and ninety-two attacks were committed by female attackers only, while twenty-two were committed by mixed-gender teams.

Although female terrorists are generally expected to achieve more tactical success merely because they are women, and gender stereotypes suggests that women are usually innocent, there is reason to believe this argument should be qualified. It is probable that female terrorists benefit in only some societies: those where gender stereotypes are particularly strong. To test this argument, I examine the strength of societal gender norms, specifically those regulating women's participation in public life. Gender norms are important in this context because they set expectations about who terrorists are, and in this case, who they are not.

Given the difficulty of measuring gender norms directly, I employ three proxies. First, I include women's civil society participation as a proxy for societal expectations about women's involvement in political violence. This variable comes from V-Dem's women civil society participation index (v2x_gencs), recording the extent to which women are able to form and participate in civil society organizations and express political ideas freely.Footnote 86 V-Dem's measure ranges from 0 to 100, where 0 corresponds to low participation while 100 denotes the converse. In these data, however, women's civil society participation ranges from 0.207 to 0.937, with a mean value of .50. The degree of women's involvement in civil society should relate to the expectation of women's involvement in political violence. Where women do not participate in civil society, expectations of their involvement in formal organizations, violent or otherwise, should be low. If it is unlikely that women are members of violent organizations, security forces and average citizens will be less apt to suspect them of terrorism and therefore, less likely to guard against their attacks. The lack of defensive preparations should lead to more severe terror attacks when female operatives are involved. In the subsequent analysis, I employ the interaction term, female attacker(s) × women's civil society participation, as a second test of Hypothesis 2.

Next, I include female attacker(s) × women's protest participation, which interacts the gender of the attacker with a measure of women's involvement in nonviolent contentious politics. Women's protest participation captures the number of events where women are identified as the primary actors involved in acts of nonviolent resistance using data from Murdie and Peksen.Footnote 87 The measure ranges from 0 to 4, where the values of 1, 2, and 3 correspond to the number of actual women's protest events experienced by a country in a given year, while 4 records four or more such events. The measure is truncated in this way because fewer than 4 percent of the observations in the data set experience more than three women's protests in a given year. The results are robust to using the entire range of this variable, however. As with the other measures, women's participation in protest activities is expected to attenuate the lethality of female suicide attacks. When women's participation in lower-cost forms of contention (i.e., protest) is atypical, skepticism about their involvement in more costly acts of political dissent (i.e., terrorism) would be warranted. However, as female participation in anti-government demonstrations increases, the notion that women might also engage in violent dissent becomes more probable. If women are known to participate in contentious politics, security forces will be less apt to overlook the potential threat of female terrorists. Acute awareness by counterterrorism operatives should frustrate female terrorists’ attempts at executing deadly attacks.

Finally, I examine female participation in the labor market as a proxy for societal norms. Women's labor force participation records the ratio of female to male labor force participation.Footnote 88 Labor force participation refers to the “proportion of the population ages fifteen and older that is economically active” and involved in the production of goods or services that contribute to a country's economy.Footnote 89 In these data, the ratio ranges from 8.92 to 96.80, where larger numbers correspond to greater equality in the workforce and smaller numbers suggest a male-dominated labor force.

Female labor force participation is a suitable proxy measure for gender norms because women's wholesale absence from the economic sphere is often the result of strong societal beliefs about the inappropriateness of women's roles outside of the domestic realm, and by extension the likelihood of female participation in public life. Several scholars posit a strong relationship between societal gender norms and female labor force participation and find that strong cultural and religious norms attenuate female labor force participation.Footnote 90 Others demonstrate that patriarchal values associated with religion, more broadly, correspond to lower rates of female participation in the formal economy.Footnote 91 Relatedly, research suggests that departures from traditional patriarchal norms toward greater gender equality have led to increases in female labor market involvement.Footnote 92

Moreover, existing research finds a strong association between women's labor force participation and female political participation. From the demand side, Iversen and Rosenbluth propose that participation in the workforce boosts the prospects for women's political representation by reducing negative stereotypes of women's political acumen; as women occupy greater roles within the labor force, perceptions of women's nondomestic skills improve, lending credibility to their political pursuits.Footnote 93 Likewise, Thomas and Wood argue that by taking on active roles in the formal labor market, women encourage liberal beliefs about the propriety of women's roles in public life.Footnote 94 Further, they argue that participation in the formal economy equips women with skills that could be put to use by political organizations, making them more attractive recruits. Therefore, recruiters for contentious organizations are likely to have higher assessments about women's value to their causes when they take part in the labor market. This is consistent with research that shows that terrorists screen their recruits for higher abilities and skills.Footnote 95 Network ties built through employment constitute another key pathway by which women are funneled into violent organizations.Footnote 96 Turning this argument on its head suggests that when women are absent from the labor force writ large, they are likely to be viewed as less capable contributors to political organizations, which will result in fewer incentives and opportunities for their mobilization into violent politics.

Thus, a lack of workforce experience should influence women's actual recruitment as well as their perceived recruitment into terrorism. Because women are less likely to be politically active when they are absent from the formal economy, expectations about their involvement in violence should be lower when their participation in the labor force is aberrant. If gender norms dictate that women do not participate in the public sphere, female terrorists should be granted the benefit of doubt with regard to their complicity in terrorism more often than their male counterparts. As a result, female terrorists should be able to bypass security measures without suspicion, which enables them to execute more deadly attacks. To test this expectation, I include the interaction term, female attacker(s) × women's labor force participation.

Control Variables

I include several potential confounders. First, it is possible that fatalities are related to the number of attackers, such that attacks executed by a greater number of terrorists are more deadly than those executed by fewer bombers. On the other hand, in the Boko Haram case, team attacks were generally less effective.Footnote 97 The number of attackers ranges from one to seven, although most attacks are committed by a single bomber. To temper the influence of outliers, I create a categorical variable, multiple attackers, coded 1 when there are one or two bombers, 2 when there are three or four attackers, and 3 for attacks executed by five or more attackers.

Although terrorist groups may cooperate, they also compete. Such competition has been found to increase the lethality of terror attacks.Footnote 98 The number of terrorist groups in country uses data from the Global Terrorism DatabaseFootnote 99 to record the number of terrorist organizations active in the target country in the year of the suicide attack to account for potential outbidding. Most countries in the data set host about ten terrorist organizations, while some (e.g., Morocco) have as few as one and others (e.g., Pakistan) as many as forty. This measure is important because outbidding constitutes one of the leading explanations for the lethality of terrorism.

Scholars find that terrorism occurs most frequently during civil wars.Footnote 100 Civil wars might be expected to exacerbate terrorism, leading to more severe terrorist attacks. Therefore, I include ln(civil war battle deaths), which records the best estimate of battle-related casualties that incurred in the context of a civil war in a given year. These data come from Melander, Pettersson, and Themner and range from 0 to 56,468 casualties.Footnote 101 The number of casualties is coded 0 if the country is not experiencing a civil war. The final measure displays the natural logarithm of battle related deaths.

Following Enders and Sandler, I include measures of the number of deaths, number killed (t-1), and the number of injuries, number wounded (t-1), a country sustained from suicide attacks in the previous month.Footnote 102 To assess whether certain types of weapon-delivery systems lead to more severe terrorist attacks, I include a categorical indicator, weapon, which records fourteen different types of weapons used in the suicide attacks in the sample.Footnote 103 It is important to account for the weapon used in a given attack because some types of weapon-delivery systems may enable terrorists to get closer to their targets (e.g., belt bomb, turban bomb) or attack targets with greater precision, which may lead to greater casualties.

The severity of the attack may also depend on the type of target. In particular, suicide attacks should be more lethal when they are aimed at targets with little security, and less lethal when targets are heavily secured. As a result, I include two dichotomous indicators categorizing whether attacks aimed at either a security target or a political target. Both types of attacks may be more difficult to execute relative to those targeting civilians, which is the reference category. Relatedly, assassinations may be selective and therefore yield few casualties even when successful. Thus, I include a dichotomous variable indicating whether an attack is an assassination attempt.

I include a measure of religion's importance to ensure that the results actually assess the effect of gender norms on terrorism lethality rather than proxying the effect of religion on terrorism. Although religion bears a strong influence on gender norms, societal norms and stereotypes should have a separate effect on the suicide attack lethality. Therefore, I construct a measure of the centrality of religion to citizens in each country using global polling data from Gallup Analytics.Footnote 104 The measure, which records the percentage of respondents that affirm that religion is “important” to their daily lives, ranges from twelve to ninety-nine in this sample.Footnote 105 Finally, I include cubic polynomials of the time since the first attack by a female assailant in April 1985 to account for potential temporal dependence.

Statistical Model

Since the death toll from a given attack is a count, I use a count model with a negative binomial distribution. Negative binomial models are appropriate when overdispersion or contagion in the data is expected. In other words, the probability of an event (a death) is not independent, but is related to the observation of other deaths. It is likely that casualties in a given attack are related, especially since suicide attackers sometimes intentionally target crowds.

The statistical results that follow are calculated with robust standard errors clustered on the terrorist campaign. Clustering on the campaign is important because suicide attacks are rarely isolated; nearly all attacks in these data occur in the context of a coherent campaign.Footnote 106

Statistical Results

Table 1 displays the average number of deaths in a given attack by the gender of the attacker(s). Although women are involved in only a fraction of all suicide attacks in this sample, attacks involving female suicide bombers are slightly more lethal than those committed by men. On average, attacks including female terrorists kill about eleven individuals while those with only male terrorists kill about nine people. This difference of means is significant at the .10 significance level. This table also compares the relative lethality of suicide attacks by gender and target type. The final column provides a test of the hypothesis that the mean lethality of attacks including female assailants is different than the average lethality of attacks committed by only male attackers. Across each type of suicide attack, those perpetrated by female terrorists are more lethal than those executed by men, though none of these differences are significantly differentiable.

Table 1. Lethality of female versus male attacks, average number killed

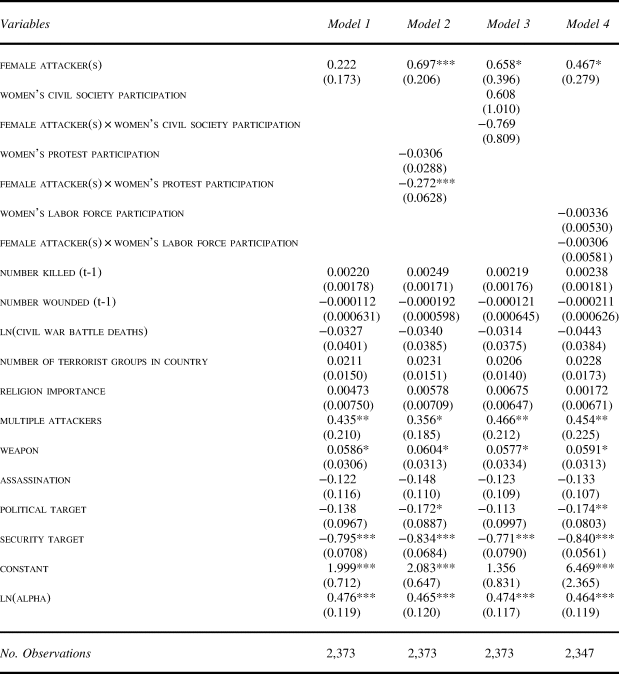

Table 2 displays the results of negative binomial regressions examining the effect of an attacker's gender on the lethality of suicide terror attacks. The results are displayed with year polynomials omitted from the table for brevity. The first hypothesis, which asserts that female suicide bombers are more lethal on average, does not appear to garner statistical support. In particular, model 1 shows that there is no statistical relationship between female suicide attackers and the lethality of an attack.

Table 2. Negative binomial regressions examining the effect of female suicide bombers on suicide attack lethality

Notes: Time polynomials omitted from table for brevity. Standard errors clustered on campaign in parentheses; *p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

The results show, however, that the effect of a terrorist's gender on attack lethality is conditional on the gender norms of the state in which the attack occurs. Models 2, 3, and 4 offer support for the second hypothesis, which suggests that female attackers will be most lethal in societies with more restrictive gender norms because women are unlikely to be suspected of participating in political violence when norms generally proscribe female participation in public life. The lack of suspicion allows female terrorists unhampered access to their targets, which enables them to carry out more deadly attacks. Therefore, a negative relationship between the various indicators of women's participation in social and political life and the lethality of a suicide terror attack is expected when the attacker is female. Model 2 examines the interaction between female attackers and women's participation in civil society, model 3 examines the interaction between female attackers and women's protest participation, while model 4 in Table 2 examines the interaction between the attacker's gender and female labor force participation.

Since these are nonlinear models, the effect of the interaction cannot be interpreted by examining the significance of the coefficient estimates. It is possible that these covariates will be significant only over a range of values, which is consistent with the expectations set forth in Hypotheses 2. To examine this, I plot the first differences over the range of the values of female civil society participation, female participation in anti-state protests, and female labor force participation.Footnote 107 Figures 1, 2, and 3 show the discrete change in the expected number of deaths when moving from using only male attackers to integrating female attackers into a given attack. All three offer support for the second hypothesis.

Figure 1. Expected change in lethality of terror attack by gender, across female civil society participation

Figure 2. Expected change in lethality of terror attack by gender, across female participation in anti-state protests

Figure 3. Expected change in lethality of terror attack by gender, across female labor force participation

Figure 1 demonstrates that female attackers tend to be most lethal when women rarely participate in civil society. As women's participation in formal organizations and associations increases, the expected benefit of female terrorist operatives declines until there is no discernible difference between the lethality of male- and female-led attacks. Suicide attacks are expected to kill nearly five more individuals when that strike is executed by a woman and when women's participation in civil society is at its lowest value (0.206). At a civil society participation value of 0.3, female suicide bombers are expected to kill about four more individuals than male suicide bombers, while female attackers are expected to log an additional 3.5 deaths when the index reaches a value of 0.4.

At the middle range of the scale, suicide attacks executed by female terrorists are expected to kill three (2.8) more people than those committed by male bombers. At higher rates of civil society participation, however, the gender of the perpetrator has no significant effect on the expected number of fatalities from a suicide attack, though the direction is negative. Overall, the results offer support for the argument that more restrictive norms benefit terrorist organizations by enabling female suicide bombers to surprise unsuspecting security forces and execute more lethal terror attacks. As women become more integrated into civil society, tactical benefits of gender appear to wane until they are negligible.

Figure 2 shows a similar trend with respect to women's protest activities. In particular, the substantive results show that fewer instances of women's participation in overt contentious political events are associated with more lethal attacks by female assailants. For instance, when a state experiences no nonviolent anti-state protests prominently featuring women, acts of suicide terrorism are expected to yield nine additional fatalities when they are perpetrated by women. When there is one women's anti-state protest event, the sample mean, the number of additional deaths expected from the use of a female terrorist declines to four. When a state experiences a relatively high number of women's anti-government protests, that is, four or more events in a given year, female suicide terrorists are expected to be less lethal than male attackers; when women's participation in organized dissent is routine, and therefore expected, female suicide attackers are expected to kill nearly three fewer individuals than men. These results hint most closely at the theoretical mechanism. That is, female suicide attackers are deadlier when women infrequently mobilize for and participate in contentious politics. As women begin to participate more frequently in acts of anti-state dissent, the lethality of female suicide bombers decreases significantly.

According to Figure 3, women's labor force participation is significant only at lower ranges of the scale. For instance, when women's participation in the labor force is about one-tenth that of men, changing the attack composition from an all-male team to one with at least one female attacker increases the expected number of casualties by five. When five times as many men work as do women (20), the increase in expected deaths is only 4.5. When the female workforce is a third of the male workforce, an increase of only 3.8 deaths is expected from the use of female suicide attackers. When half as many women work as men, the first difference decreases to three. Beyond this range of labor force participation, there is no statistically discernible difference between attacks that include only men and those that include women.Footnote 108

Interestingly, only four other covariates are statistically significant in any model. Attacks including a greater number of terrorist operatives tend to register higher fatalities. The weapon used also seems to influence the lethality of the attack. Finally, attacks aimed at security targets are significantly less lethal than those targeting civilians, while in half of the models, political attacks are found to be less deadly than those targeting civilians. Neither civil war casualties, the number of deaths and injuries resulting from suicide terrorism in the prior month, the degree of domestic competition among terrorist groups, nor a country's religiosity have a statistically significant effect on the lethality of suicide attacks.

Robustness Checks

The appendix includes a number of additional tests that examine the robustness of these results to changes in variable coding, sample composition, model specification, and statistical model choice. For example, the appendix displays results using time-fixed effects in lieu of time polynomials, excluding outlier observations, and employing a number of strategies for addressing endogeneity concerns. The main results are unaffected by these changes. In addition, there is a potential concern that, even if female suicide bombers cause a greater number of fatalities when they set off their explosives, they may fail to carry out their missions at a higher rate. If so, the overall conclusion about their increased effectiveness would have to be tempered. I explore this idea and demonstrate that this is not the case.

As noted, the suicide attack lethality data developed by the Chicago Project on Security and Threats (CPOST) includes only incidents where the attacker succumbed to injuries sustained during their attack; they exclude cases where terrorists are apprehended or willingly surrender before their plans are executed fully. This presents a problem when attempting to assess the lethality of suicide terrorism since these data cannot tell us whether women are as likely to follow through with detonating their explosives as male terrorists. This is important, however, because despite the existence of scholarship arguing that women are more resolved, steadfast, and goal-oriented,Footnote 109 some researchers suggest that women are actually more likely to second-guess killing civilians and therefore, abandon their missions more often.Footnote 110 Since the CPOST data record only what ensues after an attacker decides to go through with their mission, they cannot speak to the rate at which female and male bombers decide to abandon their missions or are intercepted. Even if their missions register higher fatality counts when completed, should women be considered assets to terrorist organizations if they exhibit higher rates of interception or desertion than their male counterparts?

To assess whether female operatives produce more lethal terror attacks fully, the impact of gender on an agent's willingness and ability to carry out an attack successfully should be addressed. I consider this question in two ways. First, to determine whether female attackers are more likely to perpetrate unsuccessful terror attacks, I use data from the Global Terrorism Database.Footnote 111 I cull all suicide attacks occurring between 1985 and 2015 that generated no casualties (dead or wounded), including the attacker. Crucially, the GTD database does not impose the restriction that the attacker must die to be included in the data set, addressing a key shortcoming of the CPOST data; it retains all cases where the perpetrator deserts or is captured in the process of executing an attack. These coding rules yield 177 “failed” suicide terror attacks, which constitute about 4 percent of the suicide attacks coded in the GTD during that time frame. Next, I code the gender of the perpetrator(s) of these attacks to determine how a terrorist's gender affects whether an attack fails. The gender of the attacker can be discerned in 134 (76%) of these cases.Footnote 112

Thirteen failed attacks were perpetrated by female terrorists, while 121 are executed by male attackers. Thus, female attackers are responsible for 10 percent of the failed attacks coded in the GTD, whereas 90 percent of failed attacks can be attributed to men. When contextualized by extant research, these trends suggest that women are not overrepresented in the failure category. For instance, Pape reports that 15 percent of suicide bombers between 1980 and 2003 were women, while Schweitzer implicates women in 15 percent of all suicide attempts between 1985 and 2006.Footnote 113 Based on these estimates, women might be expected to execute about 15 percent of the failed attacks as well.Footnote 114 The GTD data suggest, however, that women are slightly underrepresented in the sample of failed attacks when considering their overall rate of participation.Footnote 115 Moreover, O'Rourke finds that across the conflicts in her sample, women perpetrated 11 percent of failed attacks, while the remaining 89 percent of failures could be attributed to men, which provides a view consistent with the GTD data. Warner, Chapin, and Matfess further rebut the idea that women are more likely to launch failing attacks than their male counterparts. Even though Boko Haram's suicide attacks generally have a high rate of failure, they find that the organization's all-female suicide attack teams fail less frequently than all-male teams. Not only are groups of female suicide attackers more likely to detonate their bombs, they are also less likely to execute attacks that kill only themselves than all-male operations.Footnote 116

These descriptive statistics suggest that female-perpetrated suicide attacks fall within the failure category less frequently than attacks by male terrorists. I conduct a more systematic analysis to assess whether the CPOST data also support this contention using a zero-inflated negative binomial model. This two-stage model is useful in cases where two different processes are believed to generate zero and non-zero counts. The zero-inflated model is useful for assessing whether some factor systematically inclines a subset of cases to never yield positive death counts. In this particular case, if women are consistently more likely to detonate away from crowds or to attempt to sabotage their missions, attacks with female bombers would be expected to generate zero counts more often than with male bombers. The zero-inflated model can determine this by first modeling the likelihood of an attack registering zero fatalities using a logistic regression (inflation equation). After accounting for what makes a case likely to experience a zero count, it estimates the number of fatalities with a negative binomial count model.

Using the data set I described, we see that the inflation equation of the zero-inflated negative binomial indicates that operations executed by female perpetrators are significantly less likely to end up in the definite zero's category. Therefore, women are more likely to perpetrate attacks that receive positive, non-zero death counts and are thus less likely to contribute to failing operations that harm the attacker only. After accounting for the likelihood of a nonfatal terror attack, the count model delivers results consistent with the primary results reported earlier.

Do Security Forces Ever Learn?

The argument and analysis in the previous sections suggests that gender norms have a strong effect on the lethality of attacks perpetrated by female suicide terrorists. The results show that female suicide terrorists are more lethal in countries where gender norms restrict women from participating in public life, namely the workforce and political organizations. These gender norms generate tropes that women are neither politically active nor violent, which enables counterterrorists to overlook the potential harm female terrorists might cause. It is critical to note that although gender norms appear to be the primary culprit, the fault mainly lies with security forces that allow such norms and stereotypes to affect their own policies and behaviors. Efforts against this type of terrorism are likely to be ineffective as long as gender norms remain unchanged or until law enforcement becomes impervious to them. This begs the question of whether the effect of such norms and stereotypes persist over time. In other words, do security forces ever learn and adapt to female suicide terrorism?

Researchers find that practitioners of counterterrorism modify their practices based on prior experiences with terrorist organizations.Footnote 117 While terrorists adapt to the constraints they face, security forces also learn and attempt to disrupt terrorists’ innovations. Therefore, learning should be expected to occur with respect to female suicide terrorists as well. As female suicide attackers engage in more attacks, beliefs that women do not perpetrate acts of terrorism should begin to erode and security forces should start to scrutinize women as well. Thus, there is the potential for diminishing returns to female suicide terrorism.

Such learning appears to have occurred in at least three cases where suicide attacks by female operatives were prevalent. In both the Palestinian territories and Russia, there is growing awareness that women participate in terrorism.Footnote 118 In Russia, the public has become nearly “obsessed” with the idea of female suicide bombers so that suicide bombing itself has become a phenomenon most associated with women.Footnote 119 Israeli security forces have also adapted their policies in the Palestinian territories and are now intentional about subjecting men and women to similar security measures.Footnote 120 The Nigerian case is also instructive. Warner and Matfess suggest that because of the increase in female suicide bombings over time in Nigeria, several measures have been implemented to prevent female suicide terrorism, even if unsuccessful.Footnote 121 Curfews have been instituted to limit women's movements, while bus drivers have resisted female passengers all together, recognizing that women now fit the suicide terrorist profile. Maiduguri, a frequent target of Boko Haram attacks, has reportedly also held a public awareness campaign designed to educate the community on how to spot potential female terrorists.Footnote 122 Now, Nigerians are hyperaware and generally concerned about women's presence in crowded places including at security checkpoints and schools.Footnote 123 Security forces are also painfully aware that women do participate in suicide attacks frequently, and their efforts are unlikely to be encumbered by societal gender norms that suggest the contrary.

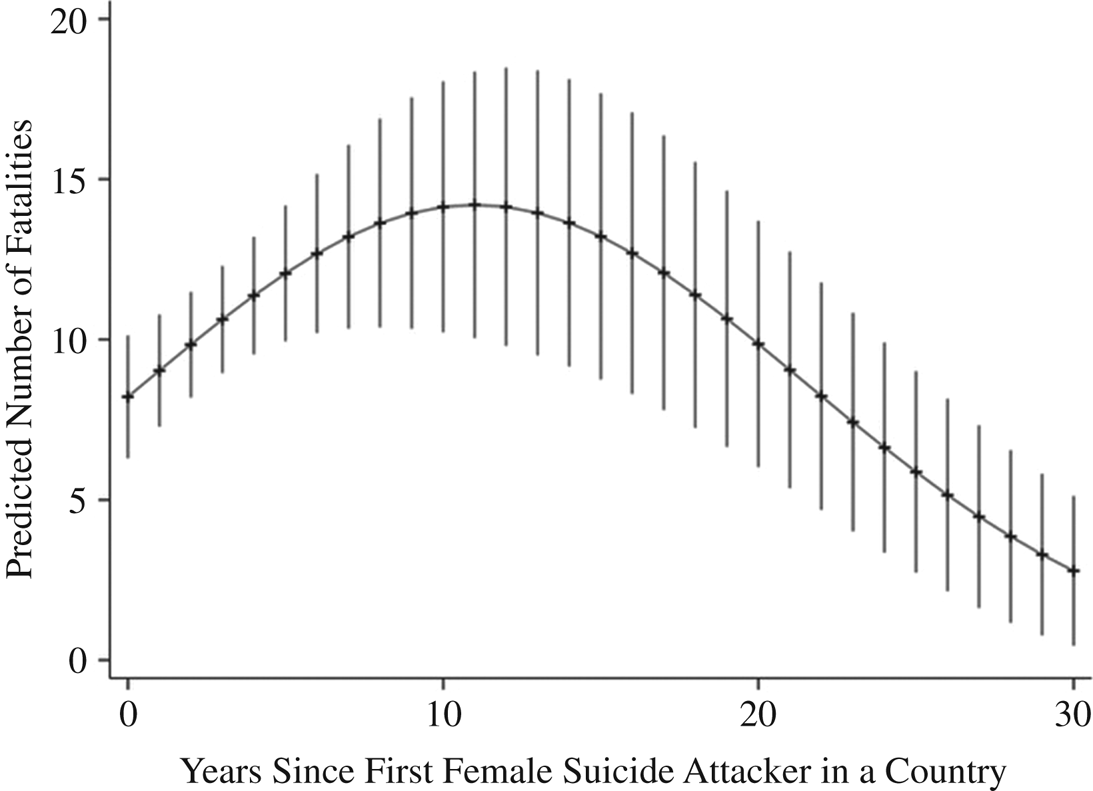

These anecdotes suggest that the benefit of women's participation in suicide bombings should decline with time. A square term for the number of years since a country experienced its first female suicide bombing is added to the first model in Table 2 to test this expectation.Footnote 124 These results are displayed in Figure 4. Although female suicide bombers should be shocking at first, the belief that women do not participate in these types of activities should eventually wane as they become more routine. As expected, the predicted probabilities show that terrorist attacks executed by female suicide bombers yield fewer fatalities over time. Surprisingly, the decline is not swift. Instead, the data seem to show that a drop in lethality is not expected until more than a decade after female suicide attackers are first introduced into a country, which seems to hint at a relatively slow learning process for counterterrorists.Footnote 125

Figure 4. Expected number of fatalities attributed to female terrorist attacks across time

Discussion and Conclusion

This article assesses the question of whether female suicide bombers are as lethal as male bombers. The results show that the female advantage in suicide terrorism appears to be strongest in countries with very restrictive gender norms and practices, while female suicide terrorists do not appear to have an edge in countries with more egalitarian conventions. In particular, the results demonstrate that female suicide terrorists are most lethal in societies where women's participation in the political and economic realms is limited. Stereotypes that women are pacific and apolitical are likely to be strongest in these circumstances and are therefore most likely to affect the threat perception of civilians and authorities alike. Importantly, the findings emphasize that one cannot understand how an attacker's perceived gender influences the severity of terror attacks without also considering the context in which those attacks occur. Finally, the article demonstrates that such norms do not appear to have a consistent impact across time. Instead, the leverage that female suicide bombers have over male attackers appears to abate as the novelty of female suicide terrorism wanes. This suggests that at some point, security forces begin to rely on experience rather than tropes to inform their counterterrorism practices. To date, no study has examined the effect of gender norms on female suicide terrorism lethality or the time horizon for this dynamic.

This research has practical importance. Gender stereotypes suggesting that women are peaceful, nonviolent, and innocent are prevalent in most states. In extreme cases, these ideas can prevent states from formulating inclusive counterterrorism policies, which can exacerbate insecurity. Existing research suggests that gender biases appear to influence the counterterrorism policies of more than a few select states. Sjoberg and Gentry, for example, highlight the ways that these biases have already affected American security policy.Footnote 126 Relatedly, Stern proffers that the terrorist profile used by the US Department of Homeland Security has applied to only men, which means that even highly capable counterterrorists can have blind spots relating to women and violence.Footnote 127 In other words, because most societies remain convinced that women are not dangerous, they may not go far enough to counter the threats that some women can pose. This article highlights the need for states to reevaluate their counterterrorism policies.

Some officials have already begun to do so. French officials, for example, are beginning to recognize that the droves of women who left Europe for ISIS-held territories may pose significant threats to security when they return. As a result, women returning from Syria will now face increased scrutiny from law enforcement in France.Footnote 128 Also, by expanding the conditions under which security operatives are able to conduct searches on women, Singapore has also made a significant alteration to their counterterrorism practice. Finally, in March 2019, American legislators introduced a bipartisan bill aimed at recognizing women's diverse contributions to both violent extremism and peace-building efforts. In particular, the Women and Countering Violent Extremism Act acknowledged that, “as perpetrators of violent extremism and terrorism, women adopt all roles, including as informants, facilitators, recruiters, and suicide bombers.” The proposed legislation concedes that current US counterterrorism policy “perpetuates blind spots, such as failing to recognize women's agency as potential mitigators and perpetuators of violence” and suggests several avenues by which to alleviate this shortcoming.Footnote 129 Similar to the policies proposed in both Singapore and France, the American act was inspired by female participation in violent campaigns in the Middle East and Africa. These developments suggest that learning is transnational; counterterrorism experts learn from events not only on their own soil but also from those around the world. Future research may examine how increases in female suicide terrorism influence the spatial diffusion of counterterrorism innovations.

This research also lends some support to the contention that the use of female operatives is an innovation in suicide terrorism and confirms the oft-cited argument that women can provide terrorists with tactical benefits. Moreover, the results demonstrate the value of those tactical benefits; female recruits can enhance the lethality of terror attacks. While terrorists’ recruitment strategies are likely to be motivated by a diverse set of factors, the findings in this article indicate that the tactical benefits that female operatives provide may undergird organizations’ decisions to recruit women for suicide missions. However, given the focus on suicide terrorism in this article, I am unable to rule out the fact that female recruitment for other types of terrorism may be triggered by different considerations. As a result, subsequent research might consider the effect of women on other forms of terrorism.

Female terrorists appear to have a clear advantage with regard to suicide terrorism because of their ability to alleviate the “access problem” that plagues many terrorist organizations, but there are also other ways women can benefit terrorist organizations. First, women could offer terrorists access to targets even in nonsuicide attacks, which could potentially help in ambushes. The 2017 confrontation between al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the US Navy SEAL team in Yemen highlights this possibility. News coverage has suggested that American troops were “surprised” by female combatants they encountered during the assault, especially in light of AQAP's “history of hiding women and children within militant operating areas.”Footnote 130 Additionally, case research has confirmed that women have been able to capitalize on the benefit of doubt they are afforded to successfully complete reconnaissance missions as well as couriering and smuggling assignments. Excelling in these tasks suggests that female recruits can also have a nonlethal advantage, which may affect terrorist groups’ ability to accomplish their broad goals and objectives. Therefore, future work may examine how terrorist organizations with gender diversity fare in the long term, compared to groups with only male operatives.

This project contributes to research on gender and terrorism by drawing attention to the relationship between demand-side dynamics and the recruitment of female suicide terrorists. Most existing scholarship on the subject has focused on the supply side, seeking to explain the specific circumstances that propel women toward suicide terrorism. While this body of work has taught us a great deal about female terrorists’ motivations, the focus on the supply side has not contributed much to our understanding of women's impact on terrorist organizations, or the consequences of women's decisions to join at the organization level. Although individual-level motivations are unlikely to explain a lot about the benefits of female participation and the related decision for terrorist groups to recruit women, some supply-side dynamics can complicate the analysis of women's impact on suicide terrorism. Specifically, whether a particular female operative is recruited forcefully or voluntarily may help explain the success of a given mission.

Although Warner and Matfess argue that “the unexpected bomber phase,” where “Boko Haram recognized the strategic utility of using new demographics of women and children as bombers” resulted in “its most lethal and injurious period,” they also assert that Boko Haram's female suicide attackers have not been more lethal than their male bombers, writ large, which might relate to their different recruitment paths.Footnote 131 Since many of the girls used by Boko Haram have been kidnapped and forced into perpetrating suicide attacks, it is unsurprising that conscripted women would lack the motivation to follow through with assignments or that they would attempt to botch missions more often than those that are willfully recruited.Footnote 132 Both should have a negative effect on mission lethality. Two of Boko Haram's would-be female bombers offered reasons for the failure of their attacks, claiming “I didn't want a situation where I'm the reason anyone dies,” and “I can't kill people, especially innocent people.”Footnote 133 Another girl resolved to blow herself up in seclusion, while others surrendered to Nigerian forces after revealing that they were forced into carrying out suicide attacks. These anecdotes suggest that since press-ganged girls appear less inclined to follow through with their attacks, the operations they are tasked with should be less lethal.Footnote 134 Future research should take a closer look at whether the mode of recruitment affects the success and lethality of suicide terror attacks. However, to do so would require more data than are currently available.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YQ40LH>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818321000035>.

Acknowledgments

Previous drafts of the manuscript were presented at Washington University in St. Louis, Browne Center for International Politics at the University of Pennsylvania, the Empirical Study of Gender Working Group meeting at Vanderbilt University, the University of California Merced, the International Politics Seminar at Columbia University, the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, the University of Chicago's Program on International Security, and the Gendered Dynamics of International Security Conference at the University of Central Florida. I am also grateful for helpful comments and suggestions from Benjamin Appel, Molly Ariotti, Jessica Maves, Martha Victor, Sarah Bush, Dawn Teele, and Tara Chandra. I am also appreciative of the excellent research assistance of Caleb Lucas.