1. Introduction

1.1 Pharasiot Greek and its speakers

This paper elucidates the structure and origin of two types of restrictive Headed Relative Clause constructions (hereafter HRCs) which co-exist today in Pharasiot Greek (PhG). PhG is a member of the inner Asia Minor Greek dialect group (iAMG), together with the varieties of Silli, Cappadocia, and Pontus (Dawkins Reference Dawkins1916: 205–206, Reference Dawkins1940: 23; Triandaphyllidis [1938] Reference Triandaphyllidis1993: 273–295; Janse Reference Janse and Janse1998a; Karatsareas Reference Karatsareas2011: 40).Footnote 2 At the beginning of the twentieth century, PhG was spoken by about 2,600 people in six villages around modern-day Kayseri in central Turkey (Sarantidis Reference Sarantidis1899: 121; Dawkins Reference Dawkins1916: 32–35). Between 1923 and 1925, its speakers were relocated to Greece in the context of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey, enacted as a supplementary protocol to the Treaty of Lausanne. Today, PhG is a moribund variety spoken by around 25 people in a number of villages in northern Greece. As of 2020, all its speakers are second generation refugees, their ages ranging between 66 and 84. We have identified 10 male and 12 female speakers who evaluate their speaking and listening abilities in the dialect as fully fluent, which is also reflected in the conversational data elicited from them, as well as in comprehension tests. None of the informants has proficient writing (or reading) skills in the dialect: PhG has no standardized orthography and many speakers only received primary school education in (standard) Modern Greek. All PhG speakers are bilingual in PhG and Modern Greek. To the latter they were exposed from an early age onwards, but crucially not since their infancy: for all our speakers, the language to which they were first exposed at home was PhG. Today, PhG is their weaker language, as is generally the case with heritage languages. No speaker uses PhG on a daily basis; however, especially in the Greek village of Vathylakkos, we have noted that when two or more speakers come together, they often converse in PhG. Among the third-generation refugees there are a few who claim to have good passive knowledge of the dialect; however, they perform rather poorly on both comprehension and production tests.

Given the heritage nature of the dialect it is reasonable – as one reviewer surmised – to expect a multitude of structural differences between present-day PhG and its ‘baseline’, i.e. the standard against which we compare today’s PhG speakers’ linguistic knowledge (Montrul Reference Montrul2016: 168; Polinsky Reference Polinsky2018: 10), which we take to be PhG as documented in the surviving written records from before and shortly after the population exchange (on which, see Section 2). There is indeed a limited number of discrepancies between heritage PhG and the baseline, pertaining to e.g. the shape of the genitive plural definite article, and the use of certain discourse particles and future markers (Bağrıaçık Reference Bağrıaçık2018: 63, 95–96, 105n71). Such rapid restructuring in the speech of a final generation of speakers has been claimed to be typical of moribund languages (Bowern Reference Bowern2008: 139). These differences notwithstanding, we take our informants to be acrolectal speakers, ‘who produce and understand the language in the manner that makes them closest to the baseline’ (Polinsky Reference Polinsky2018: 6).

Unless otherwise mentioned, the data from present-day PhG used in this paper are drawn from a spoken corpus recorded between 2013 and 2017 (with data from 11 speakers), supplemented with judgments from 17 PhG speakers interviewed during multiple fieldwork trips between 2013 and 2017. Data were elicited primarily through standard acceptability judgment tasks. To avoid the so-called yes-bias (Polinsky Reference Polinsky2018: 96), i.e. an informant’s reluctance to reject ungrammatical material, we administered multiple stimuli of the same condition at least four times to the available speakers (over a period of four years), and we supplemented our data with translation tasks (into and from Modern Greek).

With this background in mind, we can now turn to the empirical domain of our research.

1.2 Pre- and postnominal tu-relatives in Pharasiot Greek

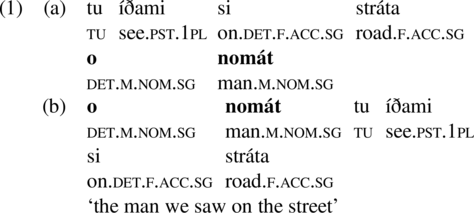

Pharasiot Greek restrictive relative clauses (henceforth RCs) are finite and introduced by the morpheme tu. In the present-day language, prenominal (1a) and postnominal (1b) RCs co-exist, without there being any obvious semantic or pragmatic difference between the two structures:

Adopting standard generative terminology, we will refer to the nominal category modified by the RC as the ‘Head’ of the RC (highlighted in boldface throughout the examples). As will be discussed in Section 2, whereas the pattern in (1a) is attested throughout the documented history of the language, postnominal RCs (1b) only became productive after the 1930s.

Prenominal RCs are at least optionally available in all iAMG varieties (e.g. Dawkins Reference Dawkins1916: 200–201; Anastasiadis Reference Anastasiadis1976: 173). It is commonly assumed that this structure came about through long-term contact with Turkish (Dawkins Reference Dawkins1916: 201–202; Andriotis Reference Andriotis1948: 48; Janse Reference Janse and Caron1998b, Reference Janse and Babiniotis1999; Thomason Reference Thomason2001: 74), a language with prenominal RCs.Footnote 3 Here we do not wish to take issue with the important role language contact played in causing this pattern to thrive; neither will we make any claims about the historical sources of prenominal RCs in iAMG varieties other than PhG. However, for the particular case of PhG, a pure language-external account of the origins of prenominal RCs does not explain the origin of the complementizer tu, which has no corresponding form in any other Modern Greek dialect (and which was not borrowed from Turkish). Furthermore, proponents of the idea that prenominal RCs originated through language contact assume that what changed is only linear constituent order: the innovative prenominal RCs are thought to be derived from their pre-existing postnominal counterparts as a reflex of a more general development in which word order in iAMG was aligned with the typical ‘head-final’ syntax of Turkish. However, although this scenario is not a priori implausible, it would remain to be determined precisely under which conditions this instance of syntactic borrowing took place. In addition, the idea of word order copying does not explain a number of structural properties of prenominal RCs in PhG, to which we turn now.

1.3 Raising and matching

One important observation concerning the two patterns in (1) is that they consistently behave differently with respect to a number of syntactic tests which are commonly used to distinguish ‘matching’ from ‘raising’ RCs. Two simplified structures for matching and raising RCs are given in (2) (cf. Cinque Reference Cinque2015: 2 ex. (1)–(2)).Footnote 4 For the sake of simplicity, we are at this point abstracting away from the linear ordering of the RC and the Head:

In a matching derivation (2a), the Head that is interpreted is an NP base-generated outside the relative CP. Inside the RC there is a ‘matching’ internal Head, which optionally raises (as indicated by the dotted arrow), and which is always deleted under identity with the external Head (for various implementations, Lees Reference Lees1961; Chomsky Reference Chomsky1965; Sauerland Reference Sauerland1998). In contrast, in raising derivations (2b) the internal Head is interpreted, but only so after it raises from within the RC to a position contiguous to the external determiner (for earlier discussions, see Brame Reference Brame1968; Schachter Reference Schachter1973; Vergnaud Reference Vergnaud1974; for recent analyses, see e.g. Kayne Reference Kayne1994; Bianchi Reference Bianchi1999; Bhatt Reference Bhatt2002; De Vries Reference De Vries2002).

In a series of recent publications, Guglielmo Cinque has proposed a unified analysis of all relativization structures available in Universal Grammar (Cinque Reference Cinque2003, Reference Cinque2008a, Reference Cinque2015, Reference Cinque2016, Reference Cinque2020). This analysis is rooted in the author’s earlier work aimed at providing a syntactic account of a fundamental, and crosslinguistically robust, asymmetry concerning the relative order of nouns and their modifiers (demonstratives, numerals, adjectives): simply put, to the left of a noun, the order of modifiers is unique, while to the right more possibilities exist (Greenberg’s Universal 20). Adopting Kayne’s (Reference Kayne1994) antisymmetric framework, which bans all symmetrical mergers of modifiers to the left as well as to the right of an XP, Cinque suggests that adnominal modifiers are always externally merged above NP, resulting in a ‘modifier – N’ base order. Postnominal modifiers are derived by NP-movement to the specifier of agreement projections, whereby NP can optionally pied-pipe some functional superstructure (Cinque Reference Cinque1996, Reference Cinque2005, Reference Cinque, Scalise, Magni and Bisetto2009). Extending this analysis to all RC types observed in natural languages, and considering the respective order of RCs and other adnominal modifiers, Cinque concludes that all types of RCs can be analyzed as phrasal modifiers, universally first-merged in the extended projection of a noun.

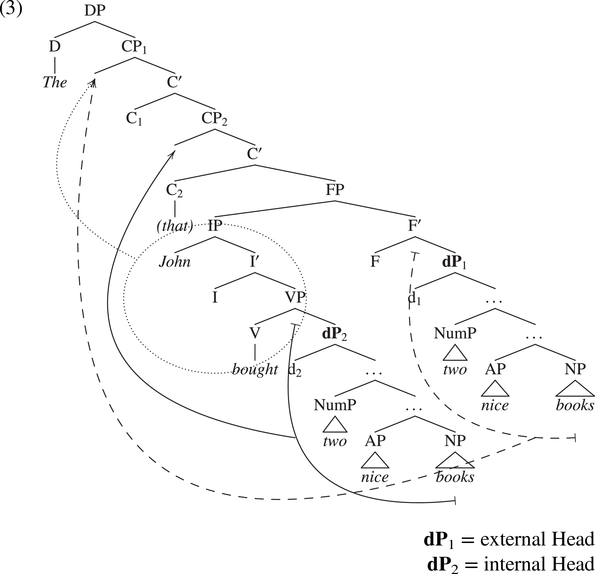

The basic structure for finite, restrictive RCs from which various surface patterns can be derived is given in (3) (from Cinque Reference Cinque2008a: 10 ex. (16)).Footnote 5 For illustrative purposes, English words were added to this structure, forming the HRC the two nice books that John bought. According to Cinque, all RCs (including free relative clauses (hereafter ‘FRCs’), for which see below) are double-Headed: they have both an internal and an external (nominal) Head, the whole structure being projected by the external Head noun, as in (3). The top node of both the internal and the external Head is taken to be a ‘little dP’, i.e. an extended NP which is not endowed with full functional superstructure. As we will see in Section 3.2, in PhG the d-node is spelled out overtly. Parametric variation (raising vs. matching; prenominal vs. postnominal; externally vs. internally Headed) is taken to be a function of (i) whether or not the internal and/or external Head move to the specifier of one of the C-projections in between FP (the functional head hosting the RC proper) and the external determiner (D), and (ii) which of the two Heads undergoes phonological deletion. Consider how exactly this works.

In the case of postnominal RCs, a raising derivation obtains when only the internal Head moves to SpecCP2 (see the solid arrow in (3)),with subsequent PF-deletion of the external Head (perhaps by virtue of the latter being c-commanded by the internal head, see Cinque Reference Cinque2020: §1.5). If, however, raising of the internal Head is followed by movement of the external Head to SpecCP1 (see the dashed arrow in (3)), it is the latter that deletes the former and ends up being pronounced, yielding a postnominal RC of the matching type. In prenominal RCs, a raising derivation is identical to what we have in the postnominal case (movement of the internal Head to CP2 and deletion of the external Head), modulo the additional movement step of the remnant IP (circled) to CP1. In prenominal matching RCs nothing moves at all, and the external Head is spelled out overtly, eliding the internal Head ‘backward’ in a type of ellipsis that is reminiscent of VP deletion, which can apply both forward and backward, without any c-command requirement by the antecedent (John might

![]() $ < $

do this job

$ < $

do this job

![]() $ > $

but I won’t

$ > $

but I won’t

![]() $ < $

do this job

$ < $

do this job

![]() $ > $

).Footnote

6

The derivation of internally Headed RCs is the converse of the matching derivation of prenominal RCs: the internal head controls the ‘forward’ deletion of the external head.Footnote

7

Finally, the syntax of FRCs – both definite and universal ones – is essentially the same as that of HRCs: the former feature two silent Heads (with which wh-pronouns are associated if they exist in a given language), namely a phonologically null classifier-like element such as person, amount, manner, or thing.

$ > $

).Footnote

6

The derivation of internally Headed RCs is the converse of the matching derivation of prenominal RCs: the internal head controls the ‘forward’ deletion of the external head.Footnote

7

Finally, the syntax of FRCs – both definite and universal ones – is essentially the same as that of HRCs: the former feature two silent Heads (with which wh-pronouns are associated if they exist in a given language), namely a phonologically null classifier-like element such as person, amount, manner, or thing.

In this paper, we adopt Cinque’s double-Headed analysis of all types of RCs, which also neatly incorporates the, by now standard, idea that HRCs involve a CP that is dominated by an external determiner (D) (cf. Partee Reference Partee1975 and much subsequent work).

1.4 Summary and roadmap

As we will discuss at length in Section 3, one crucial observation is that postnominal but not prenominal RCs in PhG display reconstruction effects and island sensitivity, suggesting that the former but not the latter involve syntactic movement, namely Head-raising. We suggest that the etymology of the relativizer tu is crucial to understand how prenominal matching RCs came about in the language. Specifically, we analyze tu as originally bimorphemic, consisting of a definite determiner t- (of category D) and an invariant (relative) complementizer u ‘that’ (i.e. a C-element). The morphological fusion of these elements around the third century ce, we claim, eliminated SpecCP (or any other position between D and C) as a possible landing site for a Head NP. Interpreting this in the light of the unified approach to RCs initiated in Cinque (Reference Cinque2003), we propose that overtly spelling out the external Head turned out to be the prevalent option to form HRCs with tu (the only alternative being internally Headed RCs, which as we will see only constitute a minority pattern). Our account thus captures not only the lack of reconstruction effects and island sensitivity in prenominal RCs, but it also explains the emergence of tu, which does not have an analogue in other Modern Greek dialects. In all likelihood, the eventual success of prenominal RCs is to be ascribed to Turkish influence, given that Greek and Turkish co-existed for about ten centuries in Asia Minor, and given that there is ample independent evidence for massive linguistic transfer from Turkish in various areas of the PhG grammar. As to postnominal RCs, which, judging by their absence in the earliest written records, are a recent innovation, we claim that they emerged due to contact with Modern Greek, to which speakers of PhG have been exposed since, at least, their relocation to Greece in 1923–1925. We suggest that the PhG relativizer tu was identified with the Modern Greek invariant complementizer pu ‘that’, and that the structure of postnominal RCs of Modern Greek was copied into PhG following this identification. As we will argue, two facts support this claim: first, both Modern Greek and PhG postnominal RCs bear characteristics of Head-raising structures, and second, neither Modern Greek nor PhG allows for constituent fronting inside postnominal RCs.

In sum, our paper sheds light on the synchrony and diachrony of both types of HRCs in PhG, and more generally on the development of relativization strategies in the Hellenic language family. At a theoretical level, it provides evidence for the claim that both raising and matching structures should be assumed for RCs, even within a single language (Sauerland Reference Sauerland1998, Reference Sauerland and Saito2000; Bhatt Reference Bhatt2002; Hulsey & Sauerland Reference Hulsey and Sauerland2006; Sichel Reference Sichel2014; Deal Reference Deal2016).

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 we introduce the basic facts about PhG HRCs, before and after the population exchange, up to today. In Section 3, we apply four tests to differentiate matching and raising to present-day PhG RCs, and conclude that prenominal RCs involve matching and postnominal ones raising. We proceed to show how prenominal and postnominal RCs in PhG can be analyzed in Cinque’s unified framework. Turning to the diachronic analysis, in Section 4 we first provide an overview of relativization strategies in the history of Greek, focusing in particular on the typology of relativizers and on the linear order of the RC with respect to the Head. In Section 5, we propose that the key to understanding the syntactic behavior of prenominal RCs in PhG resides in the etymology of the relativizer tu. In Section 6, we argue that postnominal RCs in PhG were borrowed from Modern Greek. Section 7 concludes.

2. Relativization in the attested history of Pharasiot Greek

The attested history of PhG stretches back to the late nineteenth century, and today a substantial body of texts is preserved, which allows us to have a good idea about the state of the language before it came into intensive contact with Modern Greek (see Bağrıaçık Reference Bağrıaçık2018: 14–17, for a list of these texts). In this section we provide a descriptive overview of relativization strategies in the attested history of PhG, with special attention on constituent order (prenominal vs. postnominal RCs). For reasons to be elaborated on in Section 2.1, it is important to make a distinction between restrictive and non-restrictive relatives: in a nutshell, on the assumption that the latter are amenable to an analysis in which the RC is in fact an appositive FRC, which may follow or precede a nominal associate (De Vries Reference De Vries2002: ch. 6, §5.3), we will show that initially only the prenominal RC pattern could unambiguously express restrictive modification in PhG. In later stages, however, a restrictive interpretation becomes available with postnominal RCs too.

2.1 1890s–1923: The predominance of prenominal relative clauses

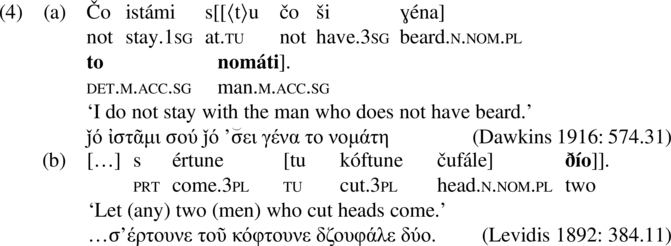

Dawkins (Reference Dawkins1916: 201) was the first author to claim that RCs in PhG are prenominal. A systematic survey of surviving PhG texts from before the population exchange of 1923 by and large confirms this, as the overwhelming majority of the attested RCs are indeed prenominal (73 out of 81 tokens, i.e. 90.12%). In all cases, the morpheme tu occurs at the left edge of the RC. Two examples are given in (4), featuring a definite (4a) and an indefinite Head (4b) respectively. The Head can also be animate or inanimate, and it can have any number, gender, and case specification (which we cannot illustrate here due to reasons of space).Footnote 8 , Footnote 9

The nominal Head in these examples occur in the absolute final position of the complex noun phrase and it always bears the case assigned to it by an element in the matrix clause (as does any determiner accompanying it), even when there is a potential mismatch between the case requirements inside and outside the RC. This suggests that the Head is external to the RC, as indicated by the bracketing.

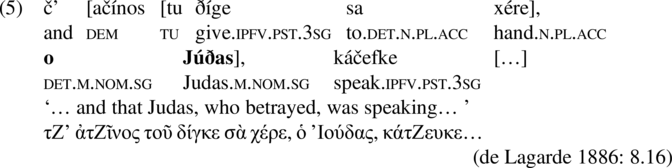

Prenominal RCs are most often restrictive: of 73 prenominal RCs, 66 are unambiguously restrictive as in (4) and four are unambiguously non-restrictive as in (5).

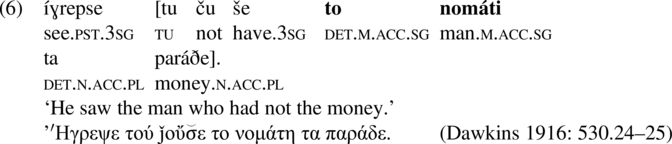

Not discussed in Dawkins (Reference Dawkins1916) is a type of restrictive HRC in which the Head does not sit at the right edge of the complex DP, but rather within the RC as in (6):

Examples like (6) could be analyzed as Head-internal RCs not containing any RC-internal ‘gap’ (Cole Reference Cole1987; Basilico Reference Basilico1996). At least from a quantitative point of view, this pattern is rather marginal: in texts from before 1923, we found only three HRCs (out of 81, i.e. 3.7%) in which the Head is followed by some material that unambiguously belongs to the RC. Remarkably, although the Head occurs within the RC, its case is assigned externally, via some mechanism whose nature is not at this point clear to us.

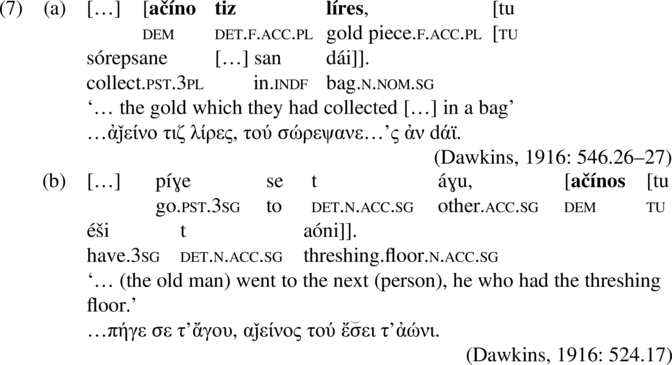

Among the remaining five (non-prenominal and non-internally Headed) RCs (6.17% of all instances), we recognize two patterns: one which features a full nominal Head (three tokens, in two of which the Head is further modified by a demonstrative as in (7a)), and one in which the Head is apparently a bare demonstrative (two occurrences, as in (7b)). Crucially, all these tokens, which at first sight qualify as postnominal HRCs, are in fact interpretively non-restrictive.Footnote 10

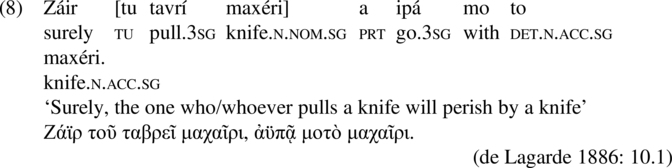

Before analyzing the patterns in (7), we should mention that the morpheme tu is also employed in argumental FRCs (who(ever), what(ever), which(ever)), which on the surface differ from HRCs only in that they do not feature an overt nominal Head.Footnote 11 As indicated in the translation of (8), these FRCs are often ambiguous between a universal/free choice and a definite reading (on which, see Dayal Reference Dayal, Strolovitch and Lawson1997; von Fintel Reference von Fintel, Jackson and Matthews2000; Caponigro Reference Caponigro2003 – see also fn 21).

A FRC with tu can feature a verb with either singular as in (8) or plural agreement as in (9), and when functioning as a subject, the FRC itself triggers either singular (8) or plural (9) agreement on the matrix verb, depending on the number of the understood referent:

We will assume that (8) and (9) are RCs with a silent nominal Head, which triggers agreement on the RC-internal predicate and, in the case of subject FRCs, also on the matrix verb. For expository reasons, however, we will continue to refer to HRCs with a silent Head as FRCs.

Returning to the cases in (7), we propose that both examples involve a FRC, i.e. a HRC with a null Head. Given that in such examples the complex NP containing the tu-relative always refers to an established discourse referent, we take this analysis to be interpretively plausible. The type illustrated in (7a) may involve a definite FRC in apposition to a nominal modified by a demonstrative pronoun: (7a) can thus literally be rendered as those gold pieces, (the ones) which they collected in a bag, in a structure where the RC non-intersectively modifies a DP whose referent is discourse-given (see De Vries Reference De Vries2002: 218–223, Reference De Vries2006, for an analysis according to which postnominal non-restrictive RCs are FRCs in apposition to an ‘antecedent’).Footnote 12 As for the second sub-type in (7b), despite their overall abundance, prenominal RCs are never attested with a bare demonstrative Head (neither before nor after the population exchange). From this, we conclude that demonstrative pronouns obligatorily preceded RCs – a word order restriction that still holds in present-day PhG (Bağrıaçık Reference Bağrıaçık2018: 75). A natural analysis of the pattern in (7b) then involves a definite FRC, whose null Head is further modified by a demonstrative pronoun. The fact that the demonstrative pronoun may carry any number and gender specification suggests that it does indeed agree with a nominal element, albeit a phonologically covert one. Cases as (7b) would thus be ‘Headed relatives in disguise’, rather than ‘light-Headed relatives’ (both in the sense of Citko Reference Citko2004).

To conclude, there is no unambiguous evidence that before 1923, PhG had postnominal HRCs; rather, the vast majority of HRCs are prenominal, with Head-internal RCs constituting a minority pattern. If real, the existence of the latter in earlier stages of PhG should not come as a surprise, as this pattern is not uncommon in languages which also have prenominal RCs (Cole Reference Cole1987). Assuming that non-restrictive relatives are FRCs in apposition, along the lines described above, in what follows we will only be concerned with restrictive HRCs.

2.2 1932–today: The gradual rise of postnominal relative clauses

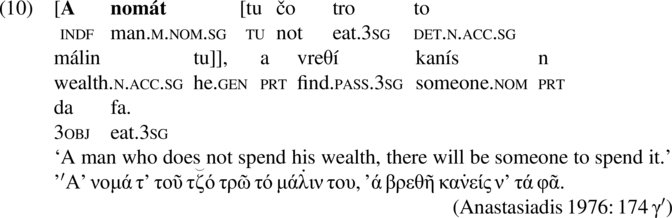

HRCs in the texts produced after the population exchange are also finite and introduced by the complementizer tu. Concerning the first decades after the exchange, Andriotis (Reference Andriotis1948: 48) and Favis (Reference Favis1948: 185) claim that RCs in PhG are always prenominal. This is by and large confirmed by corpus data from texts dating from ca. 1930 to 1970, but crucially, in this period we also find a fair amount of postnominal RCs which are unambiguously restrictive. The existence of postnominal restrictive RCs was first explicitly commented on by Anastasiadis (Reference Anastasiadis1976: 174 γ′): ‘[o]ccasionally, the [RC head] is placed at the beginning of the RC for emphasis’ (our translation). As the author does not elaborate on what exactly he means by ‘emphasis’ it is difficult to interpret this statement, and this is compounded by the fact that he only gives one example of a postnominal RC (which is moreover quoted out of context), reproduced here in (10).

In any event, Anastasiadis (Reference Anastasiadis1976) clearly acknowledges the existence of postnominal restrictive HRCs, which is confirmed by a survey of (oral and written) corpus data from after the population exchange.

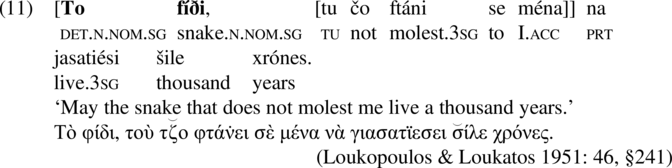

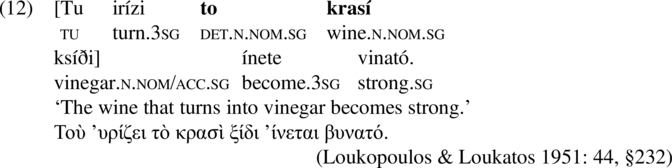

In the earliest text from after the population exchange, namely the collection of proverbs by Loukopoulos & Loukatos (Reference Loukopoulos and Loukatos1951), we see that out of 43 unambiguously restrictive HRCs, 27 are prenominal, 14 are postnominal, in (11), and two are internally Headed, in (12). Importantly, ten of the postnominal tokens can be dated around 1946–1948. The two internally Headed tokens date from before 1940.

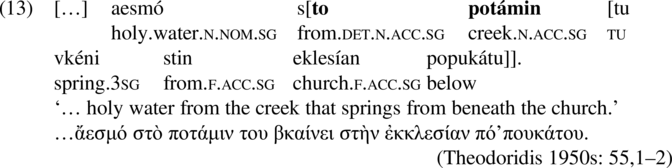

In texts from between ca. 1950 and 1970, we found no cases of internally Headed RCs. The majority of instances of unambiguously restrictive RCs are prenominal (47/52), but restrictive postnominal RCs such as (13) are also attested (viz. five times):

Next, in a number of stories recently recorded by Papadopoulos (Reference Papadopoulos2011), we find both postnominal and prenominal restrictive RCs, but no internally Headed RCs. Our synchronic data also confirms that modern-day PhG has both prenominal and postnominal restrictive HRCs. In the spoken corpus of 11 hours collected between 2013 and 2017 (on which, Bağrıaçık Reference Bağrıaçık2018: 12–13), both types of restrictive HRC with a nominal Head seem to be freely available. We found no internally Headed RCs, and this pattern is also uniformly rejected by our informants.

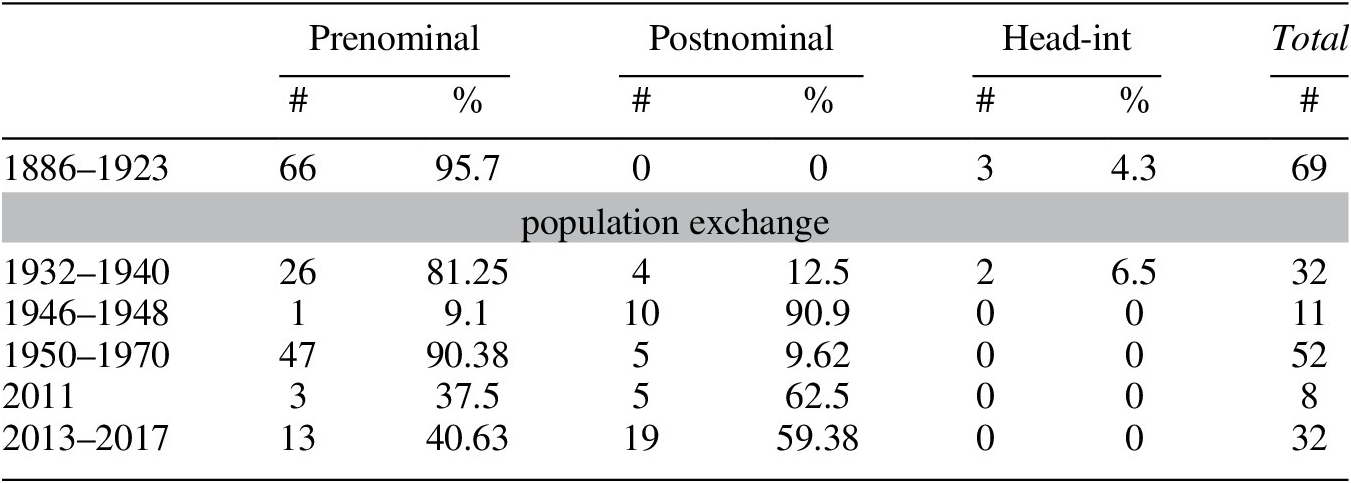

All the corpus findings reported in the last two sections are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Restrictive RCs in the attested history of PhG (up to 2017).

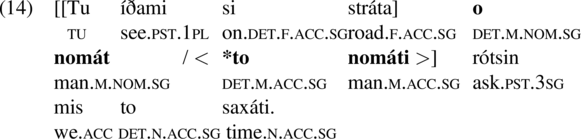

As to the syntax of HRCs in present-day PhG, native speaker judgments and data from the oral corpus reveal that there is no restriction on the nature of the Head, which can be definite or indefinite, and have any gender and number specification. In addition, the Head bears the case assigned to it by a matrix case assigner: for example, in (14) and (15) the Head receives nominative case due to the fact that the whole complex NP functions as the subject of the matrix clause. When marked for accusative case (i.e. the case it would be assigned RC-internally), the structures become ungrammatical:

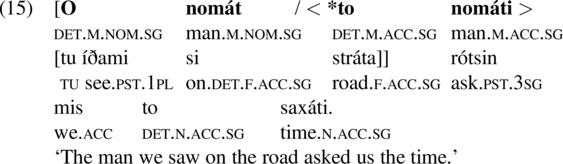

We also could not detect any semantic or pragmatic difference between prenominal and postnominal RCs. Both are accepted and used, apparently indiscriminately, although speakers unanimously agree that prenominal RCs sound archaic. The two variants can be observed in the speech of the same speaker today, such as in (16):

To sum up, genuine postnominal HRCs appeared after the speakers were relocated to Greece, and their frequency has risen considerably over the last 50 years. We now turn to the syntax of both types of HRCs.

3. The synchronic syntax of pre- and postnominal relative clauses in Pharasiot Greek

Recall from Section 1.3 that the major difference between raising and matching RCs concerns the status of the Head: only in raising structures does the phonologically overt Head originate inside the relative CP. For this reason, in raising RCs we expect to find ‘connectivity effects’ indicative of an

![]() $ \overline{\mathrm{A}} $

-dependency. In this section we will apply four tests discriminating between raising and matching RCs to the PhG data. Specifically, these tests involve phrasal idioms, quantifier scope, weak islands, and amount relatives.

$ \overline{\mathrm{A}} $

-dependency. In this section we will apply four tests discriminating between raising and matching RCs to the PhG data. Specifically, these tests involve phrasal idioms, quantifier scope, weak islands, and amount relatives.

3.1 Relative clauses in Pharasiot Greek: Raising or matching?

3.1.1 Idioms

It is commonly assumed that the object of a verb

![]() $ + $

object (V

$ + $

object (V

![]() $ + $

O) idiom chunk is not semantically autonomous, and that the non-literal meaning can only come about in a local configuration. Idioms have thus often been used to provide support for the raising analysis, the logic of the argument being that if the idiomatic reading of a V

$ + $

O) idiom chunk is not semantically autonomous, and that the non-literal meaning can only come about in a local configuration. Idioms have thus often been used to provide support for the raising analysis, the logic of the argument being that if the idiomatic reading of a V

![]() $ + $

O chunk is preserved when the object is relativized, one would have to conclude that the relevant construction involves Head-raising (Schachter Reference Schachter1973: 31–32, attributed to Brame Reference Brame1968). In (17), for instance, the fact that the idiomatic reading make headway can be obtained in the context of a HRC can naturally be accounted for by saying that the Head (headway) is interpreted ‘under reconstruction’ in its RC-internal base position as the complement of make.

$ + $

O chunk is preserved when the object is relativized, one would have to conclude that the relevant construction involves Head-raising (Schachter Reference Schachter1973: 31–32, attributed to Brame Reference Brame1968). In (17), for instance, the fact that the idiomatic reading make headway can be obtained in the context of a HRC can naturally be accounted for by saying that the Head (headway) is interpreted ‘under reconstruction’ in its RC-internal base position as the complement of make.

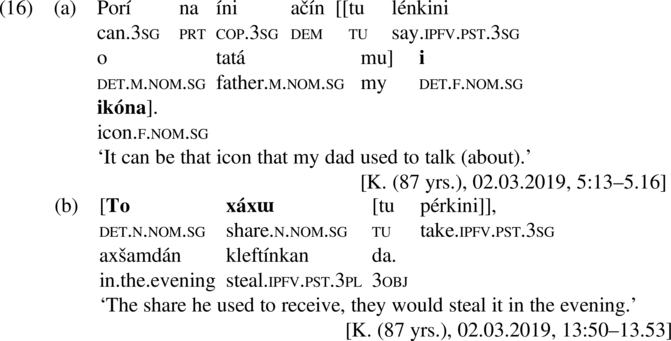

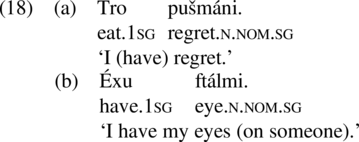

PhG possesses numerous V

![]() $ + $

O idioms:

$ + $

O idioms:

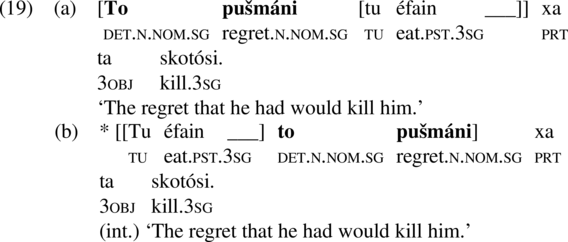

Certain idioms, such as (18b), do not allow O-relativization at all, whereas others do, the important factor being the semantic opacity/degree of lexicalization of a given idiom.Footnote 13 The idiom in (18a) does allow for O-relativization, with retention of the idiomatic reading. There is, however, one important restriction: this state of affairs only holds for postnominal RCs as in (19a); the same configuration in prenominal contexts results in unacceptability in (19b).

The fact that reconstruction of the Head is possible in postnominal but not in prenominal RCs suggests that only the former involve raising.

3.1.2 Scope Q

$ > $

Num

$ > $

Num

Further connectivity effects can be observed in RCs featuring two scope-taking expressions. Aoun & Li (Reference Aoun and Li2003) show for English that a relativized object NP modified by a numeral can be interpreted within the scope of a universally quantified subject NP inside the RC (see also Bianchi Reference Bianchi1999: 45–46):

In (20), the Head can take both narrow and wide scope with respect to the quantified subject inside the RC, namely every doctor. The wide scope reading (

![]() $ 2>\forall $

) goes with linear order. In the narrow scope reading (

$ 2>\forall $

) goes with linear order. In the narrow scope reading (

![]() $ \forall >2 $

), relevant for the connectivity effects discussed here, the Head is interpreted in the c-command domain of the quantified subject every doctor, yielding a distributive reading with twice as many patients as doctors. The availability of this reading suggests that the Head must have raised from the RC-internal object position.

$ \forall >2 $

), relevant for the connectivity effects discussed here, the Head is interpreted in the c-command domain of the quantified subject every doctor, yielding a distributive reading with twice as many patients as doctors. The availability of this reading suggests that the Head must have raised from the RC-internal object position.

In PhG, an indefinite direct object with a numeral modifier which is c-commanded by a universally quantified subject NP is always interpreted distributively (21).

Interestingly, the distributive reading of an indefinite object is preserved under relativization, but only in postnominal RCs (22a) versus (22b). This holds true even if the Head ends up being combined with a definite external determiner; note that an additional non-distributive reading also becomes available in (22a).

The availability of the narrow scope reading in postnominal but not in prenominal RCs lends further support for a raising analysis of the former variant.

3.1.3 Weak island sensitivity

Our third diagnostic tests whether RCs display sensitivity to weak islands, which we assume is indicative of

![]() $ \overline{\mathrm{A}} $

-movement. In the case at hand, Head-raising is predicted to invariably be sensitive to (certain) islands. In contrast, in matching RCs island effects are only predicted to be present if the relevant structure involves some type of

$ \overline{\mathrm{A}} $

-movement. In the case at hand, Head-raising is predicted to invariably be sensitive to (certain) islands. In contrast, in matching RCs island effects are only predicted to be present if the relevant structure involves some type of

![]() $ \overline{\mathrm{A}} $

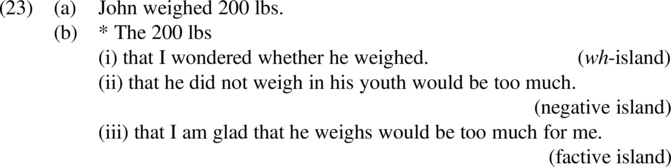

-movement, either of the internal Head or of a null operator (on the variable behavior of matching relatives in the context of syntactic islands, see Cinque Reference Cinque2008a: 12). Cinque (Reference Cinque2015: 15, referring to Rizzi Reference Rizzi1990) illustrates this point with English RCs whose Head is a (necessarily non-referential) measure phrase, which are independently known to behave like Head-raising structures. As illustrated in (22b), relativization across three different types of island boundaries results in ungrammaticality.

$ \overline{\mathrm{A}} $

-movement, either of the internal Head or of a null operator (on the variable behavior of matching relatives in the context of syntactic islands, see Cinque Reference Cinque2008a: 12). Cinque (Reference Cinque2015: 15, referring to Rizzi Reference Rizzi1990) illustrates this point with English RCs whose Head is a (necessarily non-referential) measure phrase, which are independently known to behave like Head-raising structures. As illustrated in (22b), relativization across three different types of island boundaries results in ungrammaticality.

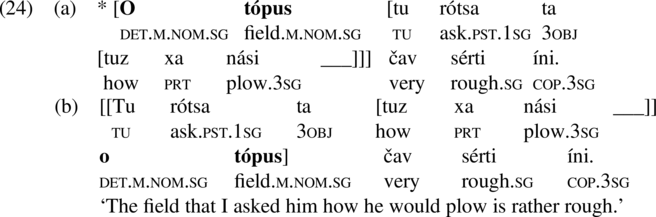

In PhG, prenominal and postnominal RCs differ with respect to weak island sensitivity. While the gap corresponding to the Head of a postnominal RC cannot be contained inside a wh-complement clause – a weak island (Cinque Reference Cinque1990; Rizzi Reference Rizzi1990) in (24a), a configuration of this type is tolerated in prenominal RCs in (24b), showing that this structure is immune to weak island effects.

The contrast between (24a) and (24b) again suggests that only postnominal RCs involve

![]() $ \overline{\mathrm{A}} $

-movement (of the Head).

$ \overline{\mathrm{A}} $

-movement (of the Head).

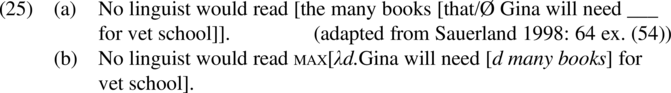

3.1.4 Amount relatives

Our final diagnostic concerns amount relatives. Amount relatives are a type of maximalizing RC (in the sense of Grosu & Landman Reference Grosu and Landman1998), in which the Head is characterized as ‘sortal-internal’: in other words, it is always interpreted RC-internally, and is semantically interpreted as a degree variable (e.g. Carlson Reference Carlson1977; Heim Reference Heim, Reuland and ter Meulen1987; Grosu Reference Grosu1994; Grosu & Landman Reference Grosu and Landman1998). Amount relatives further involve an operation of maximalization at the level of clause, which ensures that the Head is interpreted as a set of amounts, rather than a set of individuals. Consider the example in (25a), whose rough LF representation is given in (25b).

Because the Head in amount relatives is always interpreted RC-internally (irrespective of its surface position), these RCs can be characterized as bona fide raising structures (Cinque Reference Cinque2015).

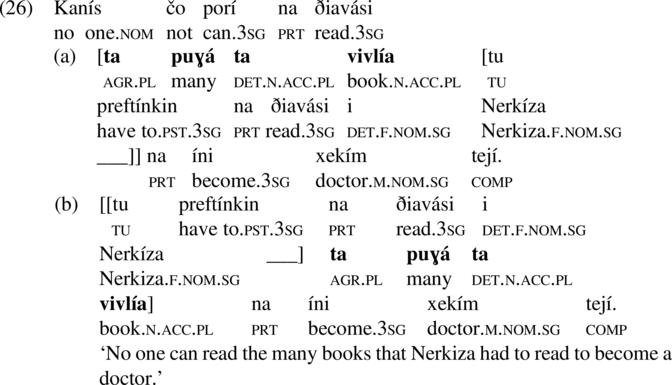

In PhG, an amount reading of the RC Head emerges only in postnominal RCs, as in (26a): ‘There is a number n such that Nerkiza read n-many books (to become a doctor) and no one can read the identical n-many books (and become a doctor)’ – the ‘set of individuals’ reading also being available for this example (‘there is a set of books

![]() $ \sigma $

, such that Nerkiza read

$ \sigma $

, such that Nerkiza read

![]() $ \sigma $

(to become a doctor) and no one can read the identical

$ \sigma $

(to become a doctor) and no one can read the identical

![]() $ \sigma $

(and become a doctor)’). In contrast, in prenominal RCs in (26b) the Head unambiguously denotes a set of individuals, suggesting that reconstruction of the Head is not possible in this structure.

$ \sigma $

(and become a doctor)’). In contrast, in prenominal RCs in (26b) the Head unambiguously denotes a set of individuals, suggesting that reconstruction of the Head is not possible in this structure.

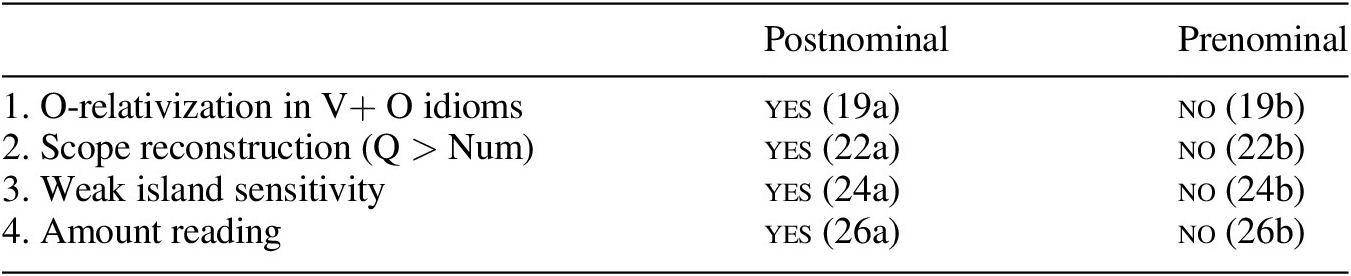

3.1.5 To sum up

The differences between pre- and postnominal RCs are summarized in Table 2. Our main conclusion is that the two patterns do not simply differ in terms of linear word order, but also with respect to their internal syntax: the postnominal variant displays connectivity effects, indicative of a raising derivation, whereas prenominal RCs do not. The latter are therefore better characterized as matching structures.

Table 2 Differences between pre- and postnominal RCs in PhG.

This conclusion implies that there is not one ‘primary relativization strategy’ (in the sense of Keenan & Comrie Reference Keenan and Comrie1977) in present-day PhG, and that one type of HRC is not derived from the other via preposing/left dislocating the Head or extraposing the RC. Apart from the structural differences reviewed so far, the lack of semantic/pragmatic differences between the two patterns also confirms this claim.

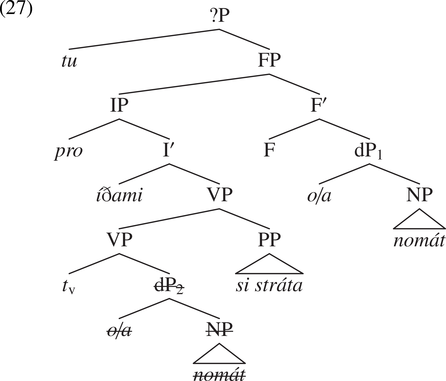

3.2 Towards a structural analysis

Returning to the syntax of HRCs in PhG, we propose that the derivation of a prenominal RC like (14) is as in (27). In this structure, neither of the Heads evacuates its base position, and the external Head dP1 triggers backward deletion of the internal Head dP2. Given that the overtly spelled out Head is the external one, the lack of connectivity and island effects, as well as the word order, are correctly accounted for.

Two remarks are in order. First, in (27) we are being deliberately vague about the functional superstructure above FP (i.e. the base position of the RC), and by this token also about the position of the relativizer tu: these two issues will be addressed in Section 5. Second, we assume that the article accompanying the external Head is the overt spell-out of d1 (which in a language like English is not lexicalized overtly), and not of an external D-category scoping over the entire complex nominal. Without going into full detail, following Lekakou & Karatsareas (Reference Lekakou and Karatsareas2016) we analyze this low determiner as a semantically vacuous expletive article, lexicalizing a nominal class feature rather than a contentful definiteness head. See also Revithiadou & Spyropoulos (Reference Revithiadou and Spyropoulos2012: 107) for related discussion concerning a variety of Pontic Greek.

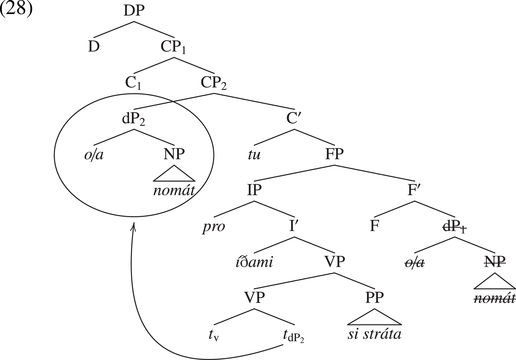

Turning to postnominal RCs (15), we propose that these are derived as in (28). This structure involves movement of the internal Head to SpecCP2, from where it deletes the external Head. Given that the overt Head has undergone

![]() $ \overline{\mathrm{A}} $

-movement, reconstruction effects and weak island sensitivity are both correctly predicted to be available.

$ \overline{\mathrm{A}} $

-movement, reconstruction effects and weak island sensitivity are both correctly predicted to be available.

Having completed our synchronic analysis, we now turn to the origins of prenominal and postnominal RCs in PhG. Our three main explananda will be (i) the difference qua constituent order, (ii) the different derivations underlying the two patterns (matching vs. raising), and (iii) the morphological shape (i.e. the etymology) of the relativizer tu. To lay the groundwork, we first give a brief overview of relativizers and relativization strategies in the history of Greek, with special reference to the period from post-Classical Greek onwards.

4. A brief overview of relativization in the history of Greek

In the history of Greek, many different relativization strategies have been available. Here we will only discuss those structures that are most relevant for diachronic reconstruction coming up in Section 5. For more detailed discussion, we refer to Probert (Reference Probert2015) (on Archaic Greek); Jannaris (Reference Jannaris1987 [1897]), 352–355, 468–471) and Van Emde Boas et al. (Reference Van Emde Boas, Rijksbaron, Huitink and de Bakker2019: 563–579) (on Classical Greek); Mayser (Reference Mayser1934: 98–113), Bakker (Reference Bakker1974), Kriki (Reference Kriki2013), and Bentein & Bağrıaçık (Reference Bentein and Bağrıaçık2018) (on post-Classical Greek); Kirk (Reference Kirk2012: 77–224) (on New Testament Greek); and to Browning (Reference Browning1983: 66–67), Chila-Markopoulou (1990–Reference Chila-Markopoulou1991), Liosis & Kriki (Reference Liosis, Kriki and Kotzoglou2014), and Holton et al. (Reference Holton, Horrocks, Janssen, Lentari, Manolessou and Toufexis2019: 1091–1164, 1983–1992) (on Medieval Greek). For general diachronic overviews, see Nicholas (Reference Nicholas1998b) and Manolessou (Reference Manolessou, Catsimali, Kalokairinos, Anagnostopoulou and Kappa2004)

Leaving aside internally Headed RCs (which are not directly relevant for our discussion of PhG), in the following two sections we introduce the most important types of postnominal and prenominal RCs that have been available in the history of Greek. In both types, the relationship between the Head and the RC-internal gap is either mediated by an agreeing relative pronoun or article, or by an invariant relativizer. We first discuss postnominal relatives.

4.1 Postnominal relative clauses

4.1.1 Agreeing relativizers

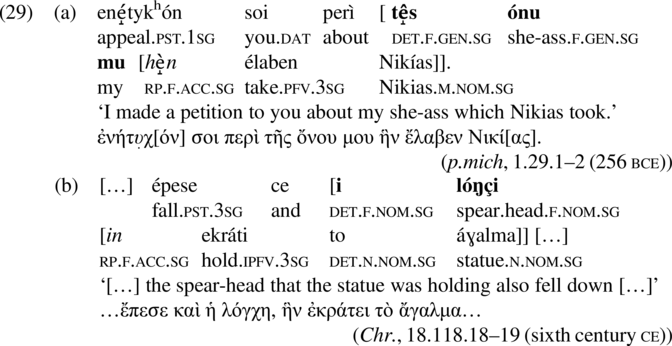

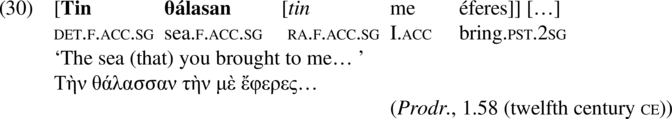

The most common relativization strategy in Archaic, Classical and Early Medieval Greek involves postnominal RCs introduced by a clause-initial relative pronoun (see Table 3). These pronouns agree in number and gender with the Head, and is typically case-marked inside the RC. Two examples with relative pronouns are given in (29).

Table 3 Ancient Greek relative pronouns.

Relative pronouns, which were in use as late as Late Medieval Greek (mostly in higher registers, Holton et al. Reference Holton, Horrocks, Janssen, Lentari, Manolessou and Toufexis2019: 1123) do not survive in any Modern Greek variety.Footnote 14

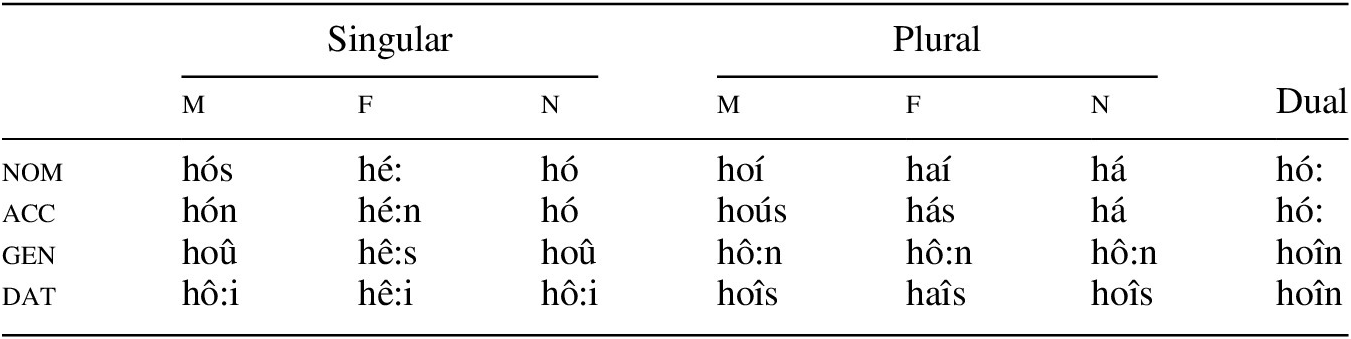

Relative articles also show number and gender agreement with the Head. They are morphologically identical to definite articles, with the proviso that masculine and feminine nominative forms (see the shaded cells in Table 4) of relative articles are not attested (Bakker Reference Bakker1974: 63–68; Manolessou Reference Manolessou, Catsimali, Kalokairinos, Anagnostopoulou and Kappa2004: 6–7; but see Holton et al. Reference Holton, Horrocks, Janssen, Lentari, Manolessou and Toufexis2019: 1097n96 for two dubious exceptions). These relativizers also appear at the left edge of the RC.

Table 4 (Ancient) Greek definite and relative articles.

An example of a postnominal RC with a relative article is provided in (30) (for additional illustrations, see Gignac Reference Gignac1981: 179; Kriki Reference Kriki2013: 291–297; Holton et al. Reference Holton, Horrocks, Janssen, Lentari, Manolessou and Toufexis2019: 1099–1103).

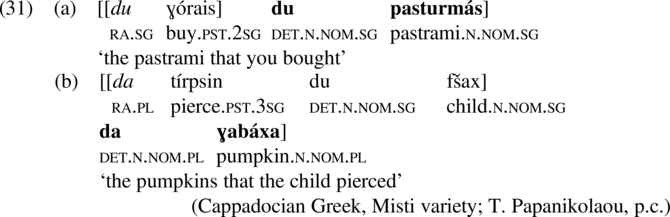

Outside the Attic dialect relative articles are attested only sporadically in Ancient and Classical Greek (Manolessou Reference Manolessou, Catsimali, Kalokairinos, Anagnostopoulou and Kappa2004: 6), but they are more common in papyri from the post-Classical period. They are also frequently found in Early Medieval Greek chronicles and hagiographical texts, and they are the most frequently used device to introduce RCs in Late Medieval Greek (Browning Reference Browning1983: 62; Chila-Markopoulou 1990–Reference Chila-Markopoulou1991: 32). They start to become rarer from the sixteenth century onwards (Holton et al. Reference Holton, Horrocks, Janssen, Lentari, Manolessou and Toufexis2019: 1097). Nominative/accusative neuter singular and plural forms of the relative articles are preserved as fossilized relativizers in certain iAMG varieties. In (31) we illustrate forms deriving from tó an tá from the present-day Cappadocian variety of Misti, where through application of standard phonological processes they appear as du (sg.) and da (pl.):

4.1.2 Invariant relativizers

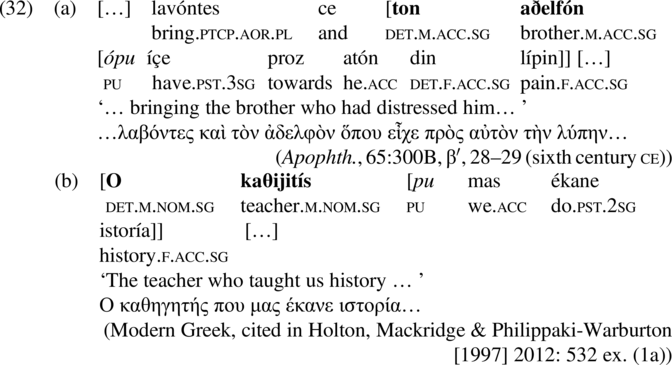

Around the fifth century ce a new relativization strategy emerged, involving the indeclinable relativizer (ó)pu, which derives from the locative relative pronoun (h)ópu ‘where’. It becomes very frequent as a generic relativizer after the twelfth century ce (Nicholas Reference Nicholas1998b: 200–211), as in (32a), and survives as the most common relativizer in Standard Modern Greek, as in (32b), and in various non-standard varieties (Nicholas Reference Nicholas1998b: 50–53, 506–536, App. B)

Another indeclinable relativizer is u, which derives from the masculine/neuter genitive singular of the relative pronoun (hoû, see Table 3). It often functions as a locative relativizer, as in (33a) (though this use becomes rarer after New Testament Greek, Nicholas Reference Nicholas1998b: 201), and after prepositions which canonically take genitive complements such as prin ‘before’, éos ‘until’, apó ‘since’, ek ‘from’, and méxri ‘until’, as in (33b), especially in post-Classical Greek (Kriki Reference Kriki2013: 209–235; Bentein & Bağrıaçık Reference Bentein and Bağrıaçık2018). Importantly, there is some evidence that u can also appear as a generic relativizer in contexts where it has apparently lost the semantics of a genitive or locative, especially in Medieval Greek, as in (33c).Footnote 15

The u does not survive as a generic relativizer in any Modern Greek dialect today; however, in Pontic Greek it is preserved as a suffix in the relativizer úts-u (

![]() $ < $

ótis

$ < $

ótis

![]() $ + $

u ‘whoever’), where it functions as a reinforcer (Liosis & Kriki Reference Liosis, Kriki, Janse, Joseph, Ralli and Bagriacik2013: 254, 261). Elsewhere, it survives in PhG in the (lexicalized) adverbial conjunction samú ‘(the moment) when’, which probably goes back to a combination of ísame ‘until’ and u. Alternatively, as a reviewer suggests, it may be a combination of sáma ‘when’ (claimed to be attested in PhG by Karolidis (Reference Karolidis1885: 128), although we did not encounter the form in our corpora) and u. In Standard Modern Greek, it appears in (archaicizing) lexicalized conjunctions like afú ‘after, since’ (

$ + $

u ‘whoever’), where it functions as a reinforcer (Liosis & Kriki Reference Liosis, Kriki, Janse, Joseph, Ralli and Bagriacik2013: 254, 261). Elsewhere, it survives in PhG in the (lexicalized) adverbial conjunction samú ‘(the moment) when’, which probably goes back to a combination of ísame ‘until’ and u. Alternatively, as a reviewer suggests, it may be a combination of sáma ‘when’ (claimed to be attested in PhG by Karolidis (Reference Karolidis1885: 128), although we did not encounter the form in our corpora) and u. In Standard Modern Greek, it appears in (archaicizing) lexicalized conjunctions like afú ‘after, since’ (

![]() $ < $

apó ‘since

$ < $

apó ‘since

![]() $ + $

u) and eksú (ke) ‘hence’ (

$ + $

u) and eksú (ke) ‘hence’ (

![]() $ < $

ek ‘from’

$ < $

ek ‘from’

![]() $ + $

u).

$ + $

u).

4.2 Prenominal relative clauses

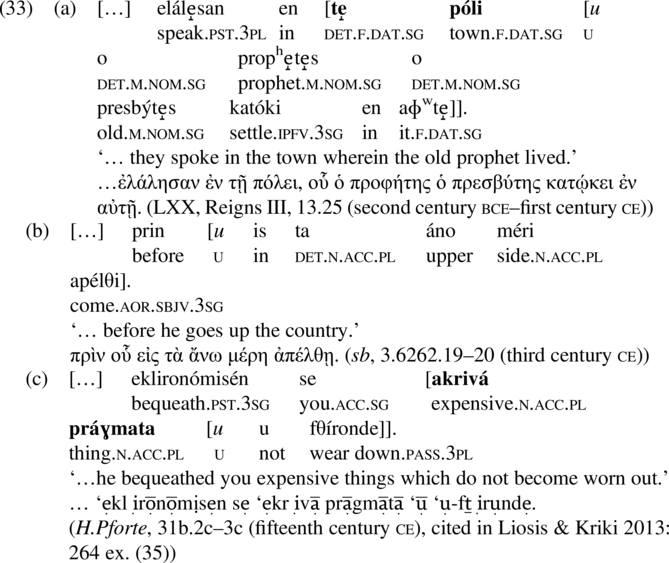

The range of possible relativizers is essentially the same in prenominal as in postnominal RCs. Below we give examples of prenominal RCs with a relative pronoun in (34) and a relative article in (35).Footnote 16

Prenominal RCs have been analyzed as internally Headed RCs (Kriki Reference Kriki2013; Fauconnier Reference Fauconnier2014; Probert Reference Probert2015) However, it is not clear whether this analysis is justified for examples like (34) and (35), for which a Head-external parse is indeed plausible, given that the Head canonically receives case from a case assigner in the matrix clause, not from a source within the RC. For further discussion of Head-external prenominal structures in post-Classical Greek, see (Bentein & Bağrıaçık Reference Bentein and Bağrıaçık2018). We now turn to the genesis of the PhG relative complementizer tu.

5. The origins of prenominal relative clauses in Pharasiot Greek

5.1

Decomposing tu as ‘D

$ + $

C’

$ + $

C’

Concerning the etymology of PhG tu, the standard view is that it is a fossilized form of the masculine/neuter singular form of the relative article (Favis Reference Favis1948: 191; Anastasiadis Reference Anastasiadis1976: 169; Nicholas Reference Nicholas1998b: 295). However, as noted in Liosis & Kriki (Reference Liosis, Kriki, Janse, Joseph, Ralli and Bagriacik2013: 264), there are certain problems with this analysis. For one thing, there is no [o]

![]() $ > $

[u] raising in monomorphemic words in PhG, making it phonologically unlikely that tu is related to to. In addition, tu is used consistently for both singular and plural Heads in PhG: in this respect, it contrasts with many other iAMG sub-varieties where (remnants of) both singular and plural relative articles are preserved (see Janse, Reference Janse and Tzitzilisto appear: §

7.4.

6; Oeconomides Reference Oeconomides1958: 243; Costakis Reference Costakis1968: 75, for the dialects of Cappadocia, Pontus (Ano Amisos variety) and Silli respectively).

$ > $

[u] raising in monomorphemic words in PhG, making it phonologically unlikely that tu is related to to. In addition, tu is used consistently for both singular and plural Heads in PhG: in this respect, it contrasts with many other iAMG sub-varieties where (remnants of) both singular and plural relative articles are preserved (see Janse, Reference Janse and Tzitzilisto appear: §

7.4.

6; Oeconomides Reference Oeconomides1958: 243; Costakis Reference Costakis1968: 75, for the dialects of Cappadocia, Pontus (Ano Amisos variety) and Silli respectively).

As an alternative, we build our analysis on the idea that ‘tu derives from the generic complementizer u with the analogical addition of t-’, attributed by Liosis & Kriki (Reference Liosis, Kriki, Janse, Joseph, Ralli and Bagriacik2013: 264) to Christos Tzitzilis.Footnote 17 We explore the hypothesis that the oldest instantiations of tu are composed of the t- segment of the definite article (i.e. a form of the article that starts with a /t/ and whose final vowel is elided), and the generic complementizer u. We believe this alternative is potentially more explanatory than an analogy-based account, which so far has not received any independent support.

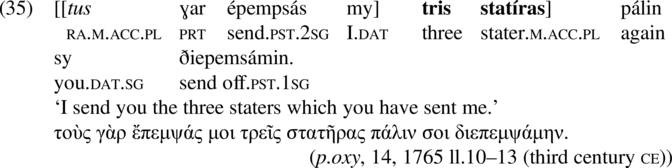

Concretely, we propose that tu came into being through reanalysis of a linear string in which a determiner built on a t-stem (with elision of the final vowel) and the generic relativizer u are adjacent, rather than through analogy. The abstract schema of the input structure for the proposed reanalysis is as in (36a). Example (36b) is the concrete realization of this pattern, which we assume gave rise to the emergence of tu.

There are two environments in which the exponent of an external D-position and a relativizer inside the RC can be string-adjacent, namely prenominal RCs with a leftward definite determiner (definite article), and light-Headed relatives – i.e. RCs headed by a demonstrative (or a bare quantifier, not relevant here), see Citko (Reference Citko2004):

Although prenominal RCs without a determiner and ‘bare’ FRCs are the norm, the two structures in (37) have been available since the Homeric period as a minority pattern.Footnote 18

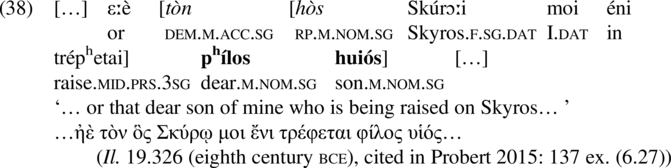

In Archaic Greek the element that later becomes the definite article clearly retains (some of) its original demonstrative force (Probert Reference Probert2015: 137). Example (38) is an example from Homer where the relevant D-category is followed by a relative pronoun:

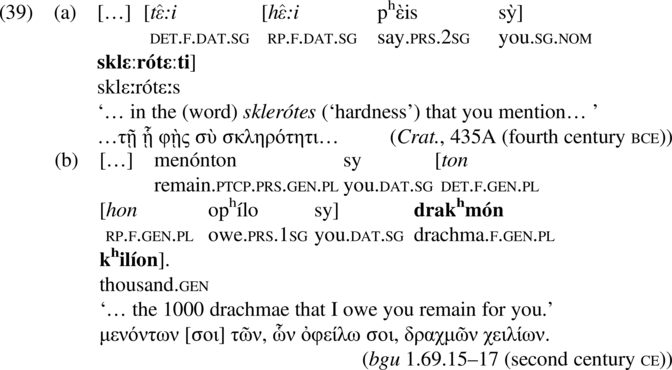

The same ‘D

![]() $ + $

relative C’ pattern is also attested in Classical (39a) and post-Classical (39b) periods, when the definite article had lost all its demonstrative semantics to become a pure marker of definiteness (see Anagnostopoulos Reference Anagnostopoulos1922: 188; Bentein & Bağrıaçık Reference Bentein and Bağrıaçık2018 for further examples).

$ + $

relative C’ pattern is also attested in Classical (39a) and post-Classical (39b) periods, when the definite article had lost all its demonstrative semantics to become a pure marker of definiteness (see Anagnostopoulos Reference Anagnostopoulos1922: 188; Bentein & Bağrıaçık Reference Bentein and Bağrıaçık2018 for further examples).

Finally, there are also numerous examples featuring the relevant ‘D

![]() $ + $

relative C’ sequence from Medieval Greek (see Jannaris [Reference Jannaris1987] 1897: 321; Nicholas Reference Nicholas, Joseph, Horrocks and Philippaki-Warburton1998a; Holton et al. Reference Holton, Horrocks, Janssen, Lentari, Manolessou and Toufexis2019: 1128–1129, 1135–1138). We therefore conclude that the structure in (36a) was indeed available.

$ + $

relative C’ sequence from Medieval Greek (see Jannaris [Reference Jannaris1987] 1897: 321; Nicholas Reference Nicholas, Joseph, Horrocks and Philippaki-Warburton1998a; Holton et al. Reference Holton, Horrocks, Janssen, Lentari, Manolessou and Toufexis2019: 1128–1129, 1135–1138). We therefore conclude that the structure in (36a) was indeed available.

5.2 Syntactic reanalysis, lexical innovation, and their consequences

We would like to propose that tu came into being when language learners analyzed a linear string consisting of a definite article of the form t(V) and the complementizer u as a single lexical item. This means that ‘t(V)

![]() $ + $

u’ sequence, realizing (36b) must have occurred in Greek at a time before this reanalysis, similar to more frequently occurring ‘D

$ + $

u’ sequence, realizing (36b) must have occurred in Greek at a time before this reanalysis, similar to more frequently occurring ‘D

![]() $ + $

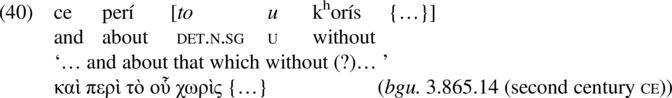

relative C’ sequences discussed in Section 5.1. Though scarce, evidence for the fact that this was indeed the case exists, as in (40):

$ + $

relative C’ sequences discussed in Section 5.1. Though scarce, evidence for the fact that this was indeed the case exists, as in (40):

The fragmentary nature of the papyrus from which (40) was extracted does not allow us immediately to reconstruct a full clause thus we cannot decisively conclude whether it instantiates a prenominal RC, a light-Headed RC or an adverbial clause. Nevertheless, it does show that the ‘t(V)

![]() $ + $

u’ sequence was available in what seems to be a subordinate clause.

$ + $

u’ sequence was available in what seems to be a subordinate clause.

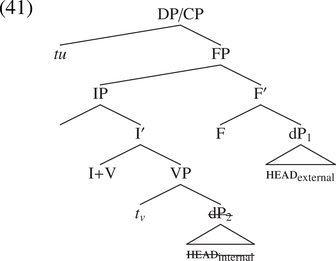

This process of morphological fusion had an immediate effect on the possible positions of the overt Head in HRCs: the specifier positions associated with the C-positions in between the external determiner and the head hosting u, which could otherwise host the displaced internal or external Head, or a remnant IP were suppressed (41). Instead, the only option to form HRCs with the newly formed relativizer tu involves spell-out of the external Head dP1 in its base position, with backward deletion of the internal Head dP2.Footnote 19 This gives rise to an externally Headed prenominal RC of the matching type, in which the bimorphemic lexical item tu heads a projection which syncretically encodes both a C- and a D-feature.Footnote 20

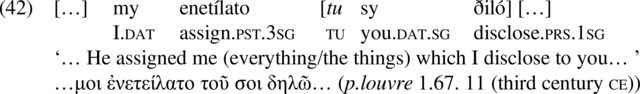

The earliest clear examples in which the relativizer tu appears as a single word that we could find are given in (42)–(43), both from the third century ce. Example (42) is a FRC and (43) is a prenominal RC. As the bracketing indicates, the structure we assume for (43) is exactly the one detailed in (41):Footnote 21

Crucially, we have encountered no early (dating from before the seventh century ce) examples of postnominal RCs with tu, in which tu is not a genitive singular of the masculine/neuter relative article, neither in the existing literature (see e.g. Kriki Reference Kriki2013: 291–310; Holton et al. Reference Holton, Horrocks, Janssen, Lentari, Manolessou and Toufexis2019: 1097–1105) nor in our own additional corpus searches.Footnote 22 This absence can naturally be accounted for given the scenario just outlined, but remains puzzling if we assume that tu was originally a (monomorphemic) relative article, as suggested by Anastasiadis (Reference Anastasiadis1976) and Nicholas (1998): we do not see why no early postnominal RC with tu should survive, not in the least because postnominal RCs with relative articles abound in the history of Greek (see e.g. Liosis & Kriki Reference Liosis, Kriki and Kotzoglou2014).

On the basis of the hypothesized structure (41), exemplified in (43), we can make one important prediction concerning the structure of (early) prenominal RCs with tu, namely that the Head should always be interpreted as definite (by virtue of t-’s D-feature), despite it not appearing with a definite article (which would compete with tu for the same structural position). This is indeed what is canonically the case with prenominal RCs in historical Greek (see Note 18).Footnote 23 However, as stated in Sections 2.1 and 2.2, in PhG the Head of a prenominal RC must be accompanied by what is traditionally called a definite determiner, which we earlier suggested are expletives rather than genuine definiteness markers (cf. Section 3.2). Alternatively, it can be accompanied by an indefinite determiner. Two relevant examples are given in (44).

We would like to suggest that the lack of a definiteness restriction on the Head emerged in PhG due to the fact that the original [

![]() $ + $

definite] feature associated with the t- component of tu was lost over time. In other words, tu was further reanalyzed as a monomorphemic exponent of C, leaving the external D-position available to be occupied by any type of non-overt determiner (definite or otherwise).

$ + $

definite] feature associated with the t- component of tu was lost over time. In other words, tu was further reanalyzed as a monomorphemic exponent of C, leaving the external D-position available to be occupied by any type of non-overt determiner (definite or otherwise).

As to the conditions under which reanalysis took place, two factors may have contributed to this development. First, note that the semantic import of the definite determiner in HRCs and light-Headed RCs such as (38)–(40) is not immediately clear, and in a sense superfluous (given that any NP with a prenominal RC was interpreted as definite anyway), especially once the determiner had lost its demonstrative force. A second factor is the relative scarcity of the ‘D

![]() $ + $

relative C’ pattern: as a result of this the relevant string may have been difficult for language learners to parse correctly, and they may have been prone to equate it to the more frequent determinerless prenominal RC pattern, at least in those contexts where the (morpho)phonological properties of the determiner (starting with a /t/ and ending with a vowel that can be elided) and the relativizer (which must start with a vowel) allow for a morphological merger to take place.

$ + $

relative C’ pattern: as a result of this the relevant string may have been difficult for language learners to parse correctly, and they may have been prone to equate it to the more frequent determinerless prenominal RC pattern, at least in those contexts where the (morpho)phonological properties of the determiner (starting with a /t/ and ending with a vowel that can be elided) and the relativizer (which must start with a vowel) allow for a morphological merger to take place.

To conclude this section, note that the above analysis goes against the standard assumption that prenominal RCs in PhG (and other AMG varieties) emerged only due to long-lasting contact with Turkish, a language in which the primary relativization strategy is the prenominal one (Dawkins Reference Dawkins1916: 201–203; Andriotis Reference Andriotis1948: 48; Janse Reference Janse and Caron1998b, Reference Janse and Babiniotis1999; Thomason Reference Thomason2001: 74).Footnote 24 The simplest interpretation of this line of analysis would entail that prenominal RCs developed from the pre-existing postnominal pattern through word order borrowing from Turkish. Importantly, however, given this scenario the origin and nature of tu remain unexplained. Instead, we take it that Turkish influence cannot be considered the sole trigger for the emergence of prenominal RCs – a conclusion reached independently by Liosis & Kriki (Reference Liosis, Kriki, Janse, Joseph, Ralli and Bagriacik2013: 265). This is, of course, not to say that we want to eliminate the role of Turkish influence on PhG HRCs altogether: we do believe that contact with Turkish ‘exacerbate[d]/reinforce[d an] existing tendency’ (à la Sitaridou Reference Sitaridou2014: 52) – namely the use of prenominal RCs.

6. Postnominal relative clauses: Modern Greek influence

To conclude our diachronic analysis, in this section we propose that PhG postnominal RCs were modeled on Modern Greek postnominal RCs, by identifying tu with the Modern Greek complementizer pu, the relativizer par excellence in this language. As the earliest attested examples of unambiguously postnominal tu-relatives in PhG are observed after the relocation of PhG speakers to Greece, this claim seems to have some initial plausibility. The growing number of postnominal RCs among today’s PhG speakers can also be understood if we take into consideration that they are only heritage speakers of PhG, and that the language they mostly use in daily life is Modern Greek. Crucially, we should also note that the overall Modern Greek influence on PhG must have started before the population exchange, through the introduction of elementary education in the region of Pharasa (Dawkins Reference Dawkins1916: 33; Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos2006: 178–179); nevertheless, contact with Modern Greek became certainly much more intensive after 1923.

Recall that Modern Greek restrictive RCs involving the bona fide complementizer pu are postnominal in (32b). HRCs with pu (which do not involve resumption, on which see Kotzoglou & Varlokosta Reference Kotzoglou and Varlokosta2005) have consistently been analyzed as raising structures (Alexiadou & Varlokosta Reference Alexiadou and Varlokosta1996; Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou1998). Hence, our claim that PhG postnominal RCs have been modeled on Modern Greek HRCs also provides a direct explanation for why postnominal RCs in PhG have a raising derivation (see Section 3).

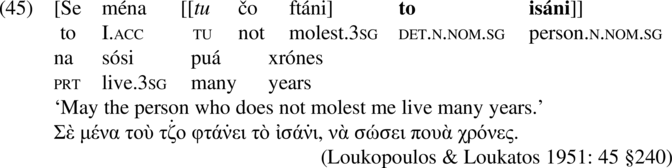

There is one additional piece of evidence in support of our claim that postnominal RCs in PhG and Modern Greek are structurally highly similar. In prenominal RCs in PhG, it is possible for constituents to be fronted from within the RC to a position before tu (Anastasiadis Reference Anastasiadis1976: 252 4.α′]. For example, in (45) the PP se ména ‘to me’ appears to the left of tu:

Such fronted constituents are arguably located in a Topic position above C (along the lines of Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997). Importantly, constituent fronting is ungrammatical in postnominal RCs. Examples such as those in (46), in which a constituent of the RC intervenes between the Head and tu, are never attested in the written or oral corpus, and are judged unacceptable by informants today:

The ungrammaticality of (46) may be ascribed to the fact that SpecCP is filled by the Head, or to there being no Topic position above tu: we will not here decide between these two possibilities. The important point is that PhG postnominal RCs pattern with their Modern Greek counterparts in terms of the ungrammaticality caused by fronted constituents: in Modern Greek too, no constituent can be fronted from within the RC to a position above pu (Roussou Reference Roussou2000: 78; example (47) is her ex. (18c) in slightly adapted form):

We would like to interpret this parallel behavior of PhG and Modern Greek to mean that postnominal RCs in the two languages are structurally similar.

7. Summary and conclusions

We have argued that prenominal and postnominal RCs in PhG have different structures and different origins. We first showed that postnominal RCs involve a raising derivation, whereas prenominal ones are of the matching type. Regarding the origins of the prenominal RCs, contrary to standard assumptions, we proposed that this structure did not emerge solely through contact with Turkish, but rather that it came about as a consequence of the morphological fusion of the exponents of an external determiner and invariant relativizer in a HRC structure, plausibly around the third century ce. This morphological fusion eliminated SpecCP (or any other specifier positions between D and C) as a possible landing site for the internal (or the external) Head, leaving a prenominal matching derivation as the major relativization strategy. According to our proposal, the role of Turkish influence consisted in fostering the pre-existing prenominal RC structure. To account for the relatively recent genesis of postnominal RCs, we proposed that language change was actuated through contact with Modern Greek. This claim was based on two characteristics common to both Modern Greek and PhG postnominal RCs: both are of the raising type and neither allow for constituent fronting. Our paper thus not only gives a diachronic explanation of two types of HRCs in PhG which correctly predicts their synchronic structural peculiarities, it also lends support to the claim that both matching and raising derivations for RCs must be acknowledged, even within a single language.

texts

Apophth.

![]() $ = $

Apophthegmata patrum: Migne, Jacques-Paul. 1864. Patrologiae cursus completus (series Graeca, 65). Paris: Migne.

$ = $

Apophthegmata patrum: Migne, Jacques-Paul. 1864. Patrologiae cursus completus (series Graeca, 65). Paris: Migne.

Chr.

![]() $ = $

Ioannis Malalas, Chronographia: Thurn, Ioannes. 2000. Ioannis Malalae Chronographia. Berlin: De Gruyter.

$ = $

Ioannis Malalas, Chronographia: Thurn, Ioannes. 2000. Ioannis Malalae Chronographia. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Crat.

![]() $ = $

Plato, Cratylus: Burnet, John. 1903. Platonis opera. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

$ = $

Plato, Cratylus: Burnet, John. 1903. Platonis opera. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

H.Pforte

![]() $ = $

A Sublime Porte Textbook: Lehfeldt, Werner. 1989. Eine Sprachlehre von der Hohne Pforte. Cologne & Vienna: Böhlau Verlag.

$ = $

A Sublime Porte Textbook: Lehfeldt, Werner. 1989. Eine Sprachlehre von der Hohne Pforte. Cologne & Vienna: Böhlau Verlag.

LXX

![]() $ = $

Septuagint: Rahlfs [1935] 1971. Septuaginta, 1. Stuttgart: Württemberg Bible Society, 623–693.

$ = $

Septuagint: Rahlfs [1935] 1971. Septuaginta, 1. Stuttgart: Württemberg Bible Society, 623–693.

Prodr.

![]() $ = $

Poems of Poor Prodromos (Ptochoprodromika): Hesseling, Dirk-Christiaan & Hubert Pernot. 1910. Poèmes prodromiques en grec vulgaire. Amsterdam: Johannes Müller.

$ = $

Poems of Poor Prodromos (Ptochoprodromika): Hesseling, Dirk-Christiaan & Hubert Pernot. 1910. Poèmes prodromiques en grec vulgaire. Amsterdam: Johannes Müller.