Human rights monitoring reports are often treated as authoritative sources of information by members of the foreign policy and advocacy communities, and as objective sources of data by scholars of international relations and comparative politics. These reports, however, are produced by human agents in real organizations, and are thus subject to multiple organizational and political pressures. Instead of coding human rights reports according to pre-defined rubrics, we use recently developed automated topic modeling tools to let these reports “speak for themselves.” Focusing on the US State Department’s annual Country Reports on Human Rights Practices (1977–2012), we apply structural topic models (STMs) to identify the underlying topics of attention and scrutiny—across the entire corpus and in each individual report.

We analyze variation in these topics across time, space, and in relation to substantive covariates pertaining to both the United States and target countries, reaching three primary conclusions. First, we find substantial variation in the salient topics of attention, both across time and worldwide. Some topics receive greater attention in some countries than in others. Some topics have declined markedly over time in prevalence, others have increased, and still others have increased then declined at different times. We highlight the need to consider such topical attention shifts when studying documents that evaluate the practices of countries on human rights or other issues (Kelley and Simmons Reference Kelley and Simmons2015). We define topical attention shifts as relative differences, over space and time, in the share of attention dedicated to a given topic. Although some of these shifts reflect real-world events and processes, we suggest that they also often result from changes in formal guidelines, informal norms, audience demands, and foreign policy biases. These shifts can inform future research, not only as potential sources of bias or measurement error to carefully consider, but also as objects of study themselves.

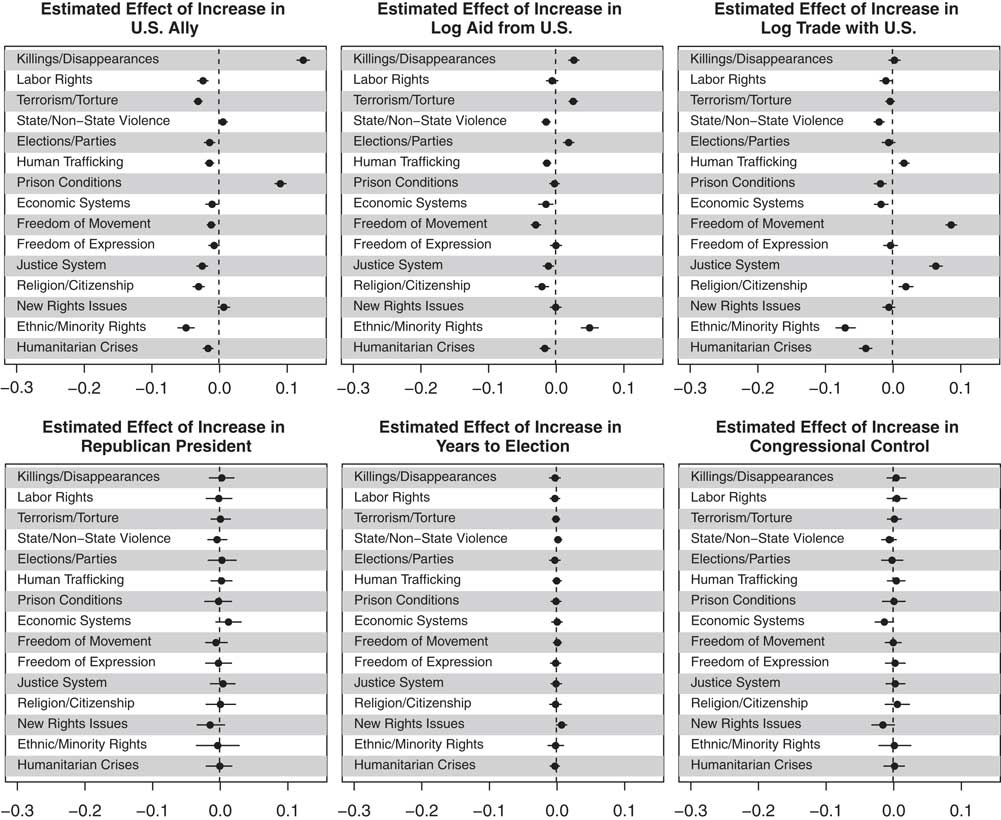

Second, while many discussions of these reports have focused on potential manipulation in response to domestic politics, we find no systematic relationships between topic prevalence and the party of the US president, the election cycle, or Congressional control. Third, while conventional wisdom holds that US allies receive a preferential bias from these reports, we find that US allies actually receive greater attention to topics associated with the most egregious types of violations.

While this approach cannot entirely disentangle whether increased topic attention is the result of “true” changes in human rights practices, or of attention bias by the State Department, current quantitative measures derived from these reports face similar challenges. In contrast with existing approaches that see “reporting politics” as a bias to either ignore or attempt to correct, our approach offers new analytical leverage by seeing these politics as a “feature,” not a “bug.” That is, we seek to answer substantive questions about reporting politics, rather than simply correct for them. Our empirical evaluation of topic variation, while controlling for measures and determinants of underlying human rights protection, also provides additional evidence for the existence and importance of topical attention shifts.

Our approach contributes both to understandings of the role of state monitoring reports in the international human rights regime, and to understandings of the promise and perils of efforts to produce valid and reliable measures of human rights and repression by human coding of monitoring reports. We also introduce the plausibility and the utility of using STMs in international relations research, especially when dealing with large bodies of documents produced by human agents subject to organizational and political pressures.

Motivation

Human rights monitoring reports form a core part of the contemporary international human rights regime. While country reports published by international Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are highlighted as important examples of “naming and shaming” (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998; Ron et al. Reference Roberts, Stewart, Tingley, Lucas, Leder-Luis, Gadarian, Albertson and Rand2005), government reports also play an important role, as sources of authoritative information, tools to pressure governments, and focal points for advocacy (De Neufville Reference De Neufville1986; Apodaca Reference Apodaca2006; Sikkink Reference Schnakenberg and Fariss2007).

The US State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices are the most widely recognized case of government human rights monitoring, and have been published on nearly every country annually since the mid-1970s. Their roots lie in Congressional requirements of human rights criteria for foreign aid, which evolved in 1976 into a requirement that annual reports be submitted to Congress on the human rights practices of any country proposed for security assistance, and soon expanded to all UN member countries (De Neufville Reference De Neufville1986, 684).

The content of the Country Reports have often been controversial, and subject to dispute by human rights NGOs, Congressional members and staff, and foreign governments (De Neufville Reference De Neufville1986, 685; Apodaca Reference Apodaca2006, 13, 16; Sikkink Reference Schnakenberg and Fariss2007, 187–8). Many reports have been accused of political manipulation or bias in favor of US allies or otherwise sensitive countries. While such criticisms have focused primarily on the Reagan administration (De Neufville Reference De Neufville1986, 689–91; Apodaca Reference Apodaca2006, 84–5), discussions of possible bias have also covered the administrations of Carter (De Neufville Reference De Neufville1986, 686–7), George H.W. Bush (Lorenz Reference Lorenz1993), Clinton (Foot Reference Foot2001, 218; Roberts Reference Richards2003, 635), and George W. Bush (Roberts Reference Richards2003, 647; Apodaca Reference Apodaca2006, 184). The topics covered by the reports have also shifted over time, both as a result of formal changes—the introduction of new requirements by Congress (Parmly Reference Parmly2001, 60) and new administration guidelines (De Neufville Reference De Neufville1986, 690)—as well as informal ones (De Neufville Reference De Neufville1986, 686).

The Country Reports have also come to play an outsized role in academic research on human rights and state repression, as commonly used sources of cross-national data on state behavior. Since the mid-1980s (Cingranelli and Pasquarello Reference Cingranelli and Pasquarello1985; Carleton and Stohl Reference Carleton and Stohl1987; Gibney and Stohl Reference Gibney and Stohl1988), scholars have used the reports as sources of information to create measures of country human rights practices and their changes over time, often along with Amnesty International reports. Early studies using such data focused on human rights as independent variables shaping US foreign assistance and other policies (Cingranelli and Pasquarello Reference Cingranelli and Pasquarello1985; Carleton and Stohl Reference Carleton and Stohl1987; Poe Reference Poe1990), and as dependent variables in the study of state repression (Mitchell and McCormick Reference Mitchell and McCormick1988; Poe and Tate Reference Poe, Carey and Vazquez1994).Footnote 1

Two of the most frequently used sets of measures, the Political Terror Scale (PTS) and the Cingranelli-Richards Human Rights Data Project (CIRI), are both coded using State Department reports along with Amnesty International’s country reports as an alternative source (Gibney and Dalton Reference Gibney and Dalton1996; Cingranelli and Richards Reference Cingranelli and Richards2010; Wood and Gibney Reference Wood and Gibney2010). These projects use information in the reports to code either the scope, intensity, and range of state violence (in the case of the PTS) or the intensity of several different categories of rights violations (in the case of CIRI). In addition to these, State Department reports have been used in several other data collection efforts including on labor rights (Mosley and Uno Reference Mosley and Uno2007), human rights trials (Sikkink and Walling Reference Sikkink2007), and wartime sexual violence (Cohen Reference Cohen2013). Given the frequent use of information in the Country Reports to code variables measuring human rights practices and other concepts, it is of great importance to consider how their content might affect the resulting measures.

Fortunately, scholars have for the most part taken these concerns seriously. Some have debated the value of using measures based on State Department versus NGO reports (Carleton and Stohl Reference Carleton and Stohl1987; Goodman and Jinks Reference Goodman and Jinks2003). Others have debated which coding schemes and measures better capture the concepts of interest (McCormick and Mitchell Reference McCormick and Mitchell1997; Cingranelli and Richards Reference Cingranelli and Richards2010; Wood and Gibney Reference Wood and Gibney2010). The PTS is up-front that “coders are instructed to presume that the information in the reports is accurate and complete” (Wood and Gibney Reference Wood and Gibney2010, 372). The CIRI project notes the necessity of cross-checking their physical integrity rights measures against Amnesty reports, “to remove a potential bias in favor of US allies” (Cingranelli and Richards Reference Cingranelli and Richards2010).

Poe et al. (Reference Poe and Tate2001) analyze differences between State Department and Amnesty reports, using two different versions of the PTS, one based on each source. They found that the two measures were farthest apart during the Carter administration, but tended to converge over time, and that US allies and aid recipients tended to receive more favorable scores based on State Department reports, while leftist regimes tended to receive less favorable scores. They additionally concluded that most biases had disappeared by the time of the Clinton administration, with the exception that US trade partners had begun receiving more favorable scores based on State Department reports. However, this analysis only extended through 1995.

Other scholars have focused on informational changes over time in both State Department and NGO reports. Keck and Sikkink (Reference Keck and Sikkink1998) and Clark and Sikkink (Reference Clark and Sikkink2013) suggest a process of information effects, meaning that, over time, as producers of the reports incorporated more information, additional types of information, and improved their ability to obtain information, individual countries’ reports might appear more negative than reality would suggest. Fariss (Reference Fariss2014, 297) similarly focuses on a “changing standard of accountability” over time, due to the increasing abilities of monitoring agencies and NGOs to gather more, and more accurate, information, as well as incentives to pressure governments for continuous improvements. Both Clark and Sikkink and Fariss find evidence for differences across human rights reports that are not wholly attributable to actual changes in states’ human rights practices.Footnote 2

Some scholars have sought to explicitly take into account potential biases and information effects, using two-stage estimators or measurement models. Hill et al. (Reference Hill, Moore and Mukherjee2013) employ a two-stage model incorporating one potential source of bias, the “exaggeration” of torture in some cases coded “widespread.” Schnakenberg and Fariss (Reference Ron, Ramos and Rodgers2014) and Fariss (Reference Fariss2014) use measurement models to estimate latent variables based on multiple different measures. Fariss (Reference Fariss2014) concludes that, once correcting for the changing standard of accountability, the average global level of repression has improved over time.

Efforts to correct for potential biases in measures of human rights practices are an important area of developing research. However, such efforts are not the only way to move forward. Projects like CIRI and PTS seek to reliably capture the reports’ content, at least regarding physical integrity rights and several other topics. While some debate the extent to which they, in turn, reliably reflect the “true” level of human rights practices, even Fariss (Reference Fariss2014, 315) argues that such measures “consistently represent the content of the human rights reports published annually by the U.S. State Department and Amnesty International, conditional on the scheme itself.”

Yet, decisions as to what constitute relevant topics for such coding schemes are made based on human judgment, and in turn are applied in a constant fashion across time periods and regions. As qualitative research has made clear, the topics considered salient in the creation of the reports has varied substantially over time, both due to formal guidelines and informal practices. Entirely new issues of human rights concern also emerge over time due to the efforts of norm entrepreneurs. And different issues may receive greater emphasis for different countries or regions, even given the same underlying human rights behavior. We suggest that these types of variation constitute another interesting and informative dimension to the content of human rights reports.

We thus highlight the potential for topical attention shifts—variation over space and time in the share of attention devoted to different human rights topics. These are a phenomenon related to, but distinct from, potential information effects and changing standards of accountability. An organization devoted to monitoring and evaluating the practices of other entities must, either formally or informally, apportion scarce resources and attention across a number of issues that it considers relevant. In principle, this step is antecedent to the gathering of information pertaining to those issues (subject to information effects), and the evaluation of that information according to standards of behavior (subject to changing standards). Shifts in allocation of scarce attention will, in some cases, be a direct response to changes in human rights practices “on the ground.” In other cases, however, shifts in attention will be shaped by organizational and political factors such as formal guidelines, informal norms, political demands, or foreign policy biases.

We thus seek to demonstrate a new, but complementary, approach to recent efforts examining information effects in human rights data. Instead of using human coders to create data on a constant set of topics, we let these documents “speak for themselves.” Thus, where the PTS and CIRI projects code reports for the intensity of violations (either overall or in specific categories), we measure relative attention to the entire range of issues that emerge as salient topics of scrutiny and attention. And rather than attempting to recover the underlying “true” value of human rights practices by making corrections that must accurately model political biases, organizational incentives, and information effects, we see these factors as our objects of study themselves. That is, by letting go of the claim that we can recover “true” human rights practices, we are able to focus more squarely on the reports themselves as documents of primary interest, and to more directly measure their content than has been possible to date.

Analysis

We began by constructing a text corpus from the US State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 1977–2012, where each document corresponds to the State Department’s report on a country’s domestic human rights practices during the previous year. Reports for years 1977–1992 were obtained from optical character recognitions of State Department PDF image files,Footnote 3 which we then divided into individual country-year reports. The remaining reports were individually web scraped.Footnote 4 This approach yielded a total of 6298 Country Reports.

We next conducted standard preprocessing tasks to prepare these texts for STM estimation. We first removed tabular information on overseas aid and loans from early reports, to enhance comparability to subsequent reports. Next, and in line with preprocessing standards (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts2014; Bagozzi Reference Bagozzi2015), we processed each report’s text to remove all punctuation, numbers, stopwords, and a number of additional nuisance character strings, including floating letters, web addresses, and named months. Finally, all remaining words were converted to lower case and stemmed to their base root.

A challenge associated with modeling international political texts lies in their preponderance of geographic (e.g., “Egypt”) and political actor (e.g., “Mubarak”) proper nouns, which can drown out other text features in topic models output (Bagozzi Reference Bagozzi2015). Other scholars have addressed this problem through ad hoc removal of proper nouns, an inexact fix at best (Bagozzi Reference Bagozzi2015). We address this challenge via a more widely accepted—and flexible—approach: removal of all processed words that do not occur in at least 10 percent of documents in our corpus. While this proportion is moderately larger than that commonly used in social science text analyses, we believe this to be a more robust solution than directed proper noun removal, given the latter’s reliance on imperfect proper noun dictionaries, and the fact that sparse term removal allows the most frequent proper nouns (particularly country names like “China,” “Iraq,” and “Israel” that appear in numerous reports beyond those of their own country, often associated with issues of substantive importance) to remain in the corpus.

We pair the resulting documents with external country-year covariates. To capture the potential effects of US domestic politics, we include variables measuring the number of years until the next US Presidential election, an indicator for whether the sitting US President was a Republican, and a measure of the extent of Congressional control of the sitting President’s party—zero, one, or two houses. To examine the effects of bilateral country relationships with the United States, we include each country’s logged US trade, formal military alliance status, and logged foreign aid from the United States. To capture baseline factors associated with human rights violations, we include Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) membership, logged gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, Polity2, a civil war indicator, and the dynamic latent human rights protection measure developed by Fariss (Reference Fariss2014). Lastly, we include a non-linear year variable (smoothed using splines) so as to both examine the variation in topics as a function of time and hold constant this factor in our broader assessments.

Modeling Approach

To assess whether the topics in the Country Reports vary in relation to the variables above, we use an unsupervised model of text known as the STM (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts2014). The STM is a topic model used for finding, and analyzing, groupings of words that characterize latent dimensions of texts. As a “bag-of-words” approach, STMs fully discard information related to the ordering of words within documents, and instead simply seek to uncover topics based upon observed correlations between words. While this assumption entails a loss of textual information, it has been shown to yield coherent substantive results across a wide variety of political science applications (e.g., Quinn et al. Reference Sikkink and Walling2010; Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Stewart and Tingley2014; Bagozzi Reference Bagozzi2015). For the STM, each document is assumed to be a mixture of multiple, correlated topics, each with characteristic words and its own prior distribution. STMs estimate these latent topics via a model that treats each document as a mixture of correlated topics while incorporating document-level external covariates into the prior distributions for document topics or topic words.

This framework allows one to simultaneously identify a set of shared latent topics across a set of documents and evaluate potential relationships between document-level covariates and the prevalence of a given topic, or on the words used to discuss that topic. We focus our analysis on the prevalence of specific topics, as a way of capturing the attention and scrutiny devoted to different human rights topics in the Country Reports. In this respect, the STM effectively allows us to estimate a series of regression models that treat the prevalence of each identified topic (across our texts) as an “outcome variable” whose variation is then modeled as a function of the country-year explanatory variables mentioned above. Alongside this analysis, the topics themselves will be simultaneously estimated by the STM model, where the analyst must explicitly choose the number of topics to be estimated. Here, Roberts, Stewart and Tingley (Reference Roberts2014) note that “[t]here is no right answer to the appropriate number of topics. More topics will give more fine-grained representations of the data at the potential cost of being less precisely estimated. […] For small corpora (a few hundred to a few thousand) 5–20 topics is a good place to start.” Our corpus contains 6298 country-year reports, though our analysis drops a small subset of these due to missingness in external covariates. Based on this, and our comparison of alternatives, we selected a topic number of 15 for our primary analysis. In the Supplemental Appendix, we show that the topwords from this 15-topic STM are similar, but more relevant and interpretable, than those identified in 10- and 20-topic models, and present additional model fit statistics to demonstrate that the 15-topic model offers the best balance of exclusivity and semantic coherence.Footnote 5

We next set about estimating our final 15-topic STM model. To address multi-modality concerns, we follow Roberts et al. (Reference Roberts, Stewart and Tingley2014) and estimate a series of 50 separate 15-topic STMs using different starting parameters for each and choosing a single model from this set of models that maximizes the semantic coherence and exclusivity of our corresponding topic word vectors.Footnote 6 Based on the results of this model, we next examine the sets of 20 words that best characterize each identified latent topic. We report the words most associated with each topic according to frequency–exclusivity scoring metrics below, which ensures that our reported topwords correspond to the word stems that are both most frequently assigned to a given topic and most exclusive in their assignment to that topic. After establishing the meaning of our 15 identified latent topics according to these topwords, we then derive a variety of post-estimation quantities that allow us to examine how topical prevalence varies across space and time, and in relation to our covariates of interest.

Human Rights Topics

The utility of the STM in studying foreign policy documents like human rights reports depends on its ability to estimate meaningful topics that reflect substantive issues of attention and scrutiny. Our final model identifies the 15 latent topics that best characterize these documents. Each topic represents an underlying word distribution wherein each word in our corpus is assigned a posterior probability of assignment to that topic. The words with the highest probability of assignment to a specific topic can thus be considered as being most representative of that underlying topic. To substantively interpret the meaning of each topic based upon these probabilistic word assignments, we draw upon the 20 most frequent and exclusive words for each topic, as well as an examination of each topic’s variation over time and space. We present our 15 topics of interest—including our labels for each topic, the topic’s topwords, and the topic’s reference number—in Figure 1, and group these topics into several informal categories for our ensuing discussion.

Fig. 1 Primary results, including the fifteen estimated topics, the twenty most frequent and exclusive (FREX) words for each, and our assigned labels.

Topics 2, 6, 7, 10, 11, and 12 are the most straightforward to interpret and label. We label these, in turn, Labor Rights, Human Trafficking, Prison Conditions, Freedom of Expression, Justice System, and Religion and Citizenship. Each reflects a coherent issue or set of issues. The Labor Rights topic, for example, includes words pertaining to unionization rights, safety and wage issues, and employment discrimination. The Human Trafficking and Prison Conditions topics are similarly straightforward. The Freedom of Expression topic includes words pertaining to media, press freedoms, and freedoms of speech and protest. Each of these topics reflects the attention devoted to these substantive issues in the Country Reports. The Justice System topic encompasses a combination of attention to deficiencies of the justice system as a human rights issue, along with procedural words that are frequently used in the reports while discussing other issues. Similarly, the Religion and Citizenship topic likely corresponds to a combination of religious freedom issues and laws governing citizenship, along with procedural words that are frequently used in reports for predominantly Muslim countries.

Topics 8 and 13, on the other hand, both capture coherent sets of issues but are also shaped by similar patterns of variation over time. Topic 8, which we label Economic Systems, reflects words related to communist regimes, economic and demographic issues, of particular importance during the Cold War. These issues also received explicit focus under a section of reports titled “Economic, Social, and Cultural Situation,” which was phased out in the mid-1980s. Indeed, Figure 2 clearly show the steep decline of Topic 8 from the beginning of the period under study until roughly 1990. However, by virtue of capturing issues that predominantly appeared in the first several years of human rights reports, the topic model also associates Topic 8 with other words that similarly appeared disproportionately in early reports, such as “guarantee” and “amnesty.” Early reports tend to be much shorter in length, and to cover issues in a more undifferentiated way, leading the STM to identify sets of words used more commonly in early reports as a single topic that declines over time. This feature renders this topic less directly interpretable than the others.

Fig. 2 Changing topic prevalence over time in the Country Reports. Lines show the (smoothed) average annual prevalence for each topic, across all reports.

Topic 13, “New Rights Issues,” rises dramatically from roughly 2000 until the present, as shown in Figure 2. The topwords for Topic 13 reflect not a single human rights issue, but rather a collection of new issues that became important topics of focus over the past two decades due to combinations of technological change and global norm emergence. These include gender violence, asylum-seekers, internet freedoms, and corruption. While these are not substantively related to each other in any straightforward way, they are identified as a single topic due to their common increases in frequency over similar time periods.

Topics 3, 5, 9, and 14 reflect relatively clear and coherent sets of human rights issues, but also include frequent region-specific terms among their most frequent and exclusive words. While this suggests a degree of regional clustering for these topics, an examination of the spatial variation in these topics (see Figures A.1–A.15) makes clear that their prevalence remains widespread beyond any one single region of the world. We thus choose to label these topics in a way that emphasizes their substantive, rather than region-specific, interpretations.

Topic 3, for example, is represented by “israel,” “arab,” “west,” and “bank,” as its four most frequent and exclusive words, clearly focusing on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. However, an examination of the remaining words makes clearer that this topic also reflects substantive issues of terrorism, torture, and mistreatment of detainees. Similarly, Topic 5 combines words that reflect substantive issues of elections, campaigns, and political parties, along with several words more specific to countries in Africa. Topic 9 combines words pertaining to both internal freedom of movement and international migration, along with words specific to China. Finally, Topic 14 combines words reflecting ethnic and minority rights, along with several Europe-specific words. We label these topics according to their substantive content: Terrorism and Torture, Elections and Parties, Freedom of Movement, and Ethnic and Minority Rights.

Finally, Topics 1, 4, and 15 all reflect violence, conflict, and violations of physical integrity rights, but require particular attention due to a higher level of conceptual overlap. We label these “Killings and Disappearances,” “State and Non-State Violence,” and “Humanitarian Crises.” Importantly, the topwords for all three reflect combinations of civil conflict, armed actors, and violence against civilians. Topic 15, however, is differentiated by a greater focus on the humanitarian consequences of conflict, including words like “displac,” “civilian,” “idp” (internally displaced persons), “humanitarian,” and “rape.”

Topics 1 and 4 overlap much more considerably, even sharing the topword “disappear.” Topic 1 includes many words pertaining to killings, disappearances, kidnappings, and murders, but also some words pertaining to investigations or trials for human rights violations, such as “prosecutor,” “investig,” “san,” and “jose”—the latter two reflecting the location of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Costa Rica’s capital. It also includes some words that most likely reflect a Latin American regional focus. A map of the prevalence of this topic (Figure A.1) shows clear clustering in Latin America, along with more widespread prevalence in other countries that have experienced human rights abuses in the context of armed conflict.

Topic 4, on the other hand, also includes words pertaining to extrajudicial killings and disappearances, as well as many pertaining to both state and non-state armed groups and armed engagements between them—“regim,” “insurg,” “armi,” “war,” “attack,” and “milit.” The presence of the word “iraq” and the spatial variation of this topic (Figure A.4) show some regional clustering in the Middle East, but still a great deal of prevalence elsewhere in the world. We hence emphasize that Topics 1 and 4 are largely capturing similar and overlapping concepts—violations of physical integrity rights in the course of violence and conflict between state and non-state groups. These emerge as distinct topics, however, due to the use of different sets of words across different countries and regions. However, in the interest of clarity, we assign separate labels to these two topics based on the differences in topwords: Killings and Disappearances (Topic 1), and State and Non-State Violence (Topic 4).

Sources of Topic Variation

These 15 topics do not appear evenly across all countries and time periods, but instead show substantial variation. It is important to recognize that some topics are likely more legally or technically complex than others, thereby requiring more words to communicate the same amount of information. Thus, our assessment of topical variation focuses on examining within-topic variation over time and space, as well as changes in prevalence associated with different covariates, rather than on discussions of each topic’s overall share of total text. Figure 2 shows the varying prevalence of each topic over time, averaged across all country reports in each year. Figures A.1–A.15, in turn, map the geographic prevalence of each topic, using the average across all reports for a given country over the entire period.

While some topics are relatively constant in prevalence, or trend gradually upwards over time, several others rise or fall dramatically. In addition to the aforementioned Economic Systems and New Rights Issues, two others stand out. The Labor Rights topic increases in prevalence beginning in the mid-1980s, reaching a peak around 1990 and declining in prevalence subsequently. Second, and consistent with the burst of UN declarations and reports on human trafficking in the mid-to-late 1990s, the Human Trafficking topic increases in prevalence beginning in the mid-1990s, before peaking in the mid-2000s and declining subsequently.Footnote 7

Fully understanding the variation in topical prevalence over time and across countries requires close attention to the multiple possible sources of such variation, and the limitations of an empirical approach based on subjective foreign policy documents. Our results suggest three categories of sources of topic variation.

First, topics can shift due to real-world events and processes, when new problems become salient either in individual countries, regionally, or globally. Examples include real human rights violations by state or non-state actors, civil wars and ethnic conflicts, and elections following democratic transitions, as well as technological changes, which in the case of internet freedoms led to appearance of a new set of human rights issues. State actors may also adopt new strategies of repression in response to outside scrutiny. Individual country reports naturally respond to such events and processes—whether specific to a single country or global in scope—with attention and scrutiny to the appropriate human rights topics.

Second, topics can shift due to changes in formal guidelines for State Department staff to prepare the Country Reports. These include new Congressional requirements that the reports address labor rights (1984), religious freedom (1998), and human trafficking (2000). These also include executive branch shifts, such as the Reagan administration’s decision to de-emphasize economic and social rights (De Neufville Reference De Neufville1986, 690), the George H.W. Bush administration’s decision to include sections on violations in internal conflicts, and the Clinton administration’s decision to expand the section on discrimination (Parmly Reference Parmly2001, 60). Finally, these can also include internal State Department decisions concerning the organization of the reports and the sections to be included.

Third, topics can shift for informal reasons that are neither direct responses to real-world events nor changes in formal guidelines. There are three different types of such informal sources of topic shifts: international norms, audience demands, and foreign policy bias. The emergence of new international norms as part of a norm cascade (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998) may shape the topics considered worthy of attention and scrutiny in human rights reports, even absent formal guidelines. Norm emergence includes an increase in international awareness of new issues, the construction of new topics as human rights issues, and sometimes the application of a human rights frame to issues that were previously not commonly understood as human rights issues. Many of the topwords in the New Rights Issues topic reflect these processes, including issues of gender violence, stateless persons, and corruption. The increase in attention to human trafficking several years before the 2000 Trafficking Victims Protection Act also illustrates the rise in international attention to this issue.

The topics in State Department Human Rights Reports may also shift as a result of informal pressure from key audiences. These can include Congress itself, which has often held hearings critical of the content of the reports, and human rights NGOs, which have a long record of criticizing the Reports’ content and frequently calling for greater scrutiny of some countries and topics. Other interest groups, like labor unions or religious organizations, may also be partially responsible for shifts in attention to Labor Rights, Religion and Citizenship, and Human Trafficking (Foot Reference Foot2001; Weitzer Reference Weitzer2007).

Finally, the topics in human rights reports may shift due to foreign policy biases, such as protecting allies and trade partners, ensuring the continuation of foreign aid given Congressional requirements, and supporting administration objectives or foreign policy frames like the fight against communism or the war on terror. Indeed, this final informal source of topic variation comprises issues that have long been discussed in both qualitative and quantitative treatments of the Reports. Biases can also be the result of media attention, as has been demonstrated in NGO reports (Ron et al. Reference Roberts, Stewart, Tingley, Lucas, Leder-Luis, Gadarian, Albertson and Rand2005).

These different sources of variation contribute to topical attention shifts, affecting the probabilities that different types of human rights issues will be considered salient topics for attention and scrutiny, rather than the probabilities of detection or classification for particular abuses. While formal and informal sources of topic shifts resemble discussions of information effects in human rights data by Clark and Sikkink (Reference Clark and Sikkink2013) and Fariss (Reference Fariss2014), they constitute a distinct dimension to the content of human rights reports. Attention shifts among different issues differ from standards of classification of abuses for individual issues themselves. We also extend these ideas to address not just shifts in what types of actions constitute inhuman treatment or other violations of physical integrity, but also shifts in other human rights issues as well. These include issues focused on expression, elections, gender, and working conditions, among others.

Importantly, we do not claim that the STM results can entirely disentangle different sources of topical attention shifts. If, for example, scrutiny of some topics increases dramatically in a country following the onset of a civil conflict, this may be a direct result of worsened conditions on the ground, or because the conflict has attracted greater attention to certain issues in that country, or a combination of the two processes. However, research using quantitative measures coded from the Country Reports often faces similar challenges. While future research may aim specifically to disentangle these, our present approach aims to embrace the subjective nature of foreign policy documents, and understand topic variation without assuming that it reflects objective ground truths.

We focus here on testing foreign policy biases and domestic US politics as potential sources of topic shifts, and include the series of control variables mentioned above to capture other relevant sources of topic variation, in particular the baseline level of “on the ground” circumstances that human rights reports ought naturally to respond to. These control variables are tailored to the goal of isolating the domestic and international politics of topical attention shifts, and seek to account for other possible confounders to the extent possible in the STM research design. After accounting for these baseline sources of topic variation, we test whether topic scrutiny in the Country Reports shifts in response to characteristics of a country’s relationship with the United States, or to features of US domestic politics. While other sources of topic variation are empirically testable, we leave these for future research.

The Politics of Human Rights Attention and Scrutiny

Figures A.16–A.26 in the Supplemental Appendix show the estimates obtained from our STM results for the relationships between each external covariate and each of the 15 topics discussed previously. We focus in Figure 3 on the results for six covariates of primary interest, capturing elements of foreign policy relationships and US domestic politics while controlling for our remaining covariates (including time).

Fig. 3 Relationships between six external covariates and each topic, based on the estimated effect of an increase in the covariate on the expected prevalence of each topic. Increases are from 0 to 1 for dichotomous variables, and from one standard deviation below the mean to one standard deviation above for others. Horizontal lines show 95 percent confidence intervals. See the Supplemental Appendix for full results for all external covariates.

We find striking results for the effects of military alliances with the United States on topic attention. The results show that US allies receive more attention to three topics: Killings and Disappearances, State and Non-State Violence, and Prison Conditions. The estimated effects on Killings and Disappearances and Prison Conditions are particularly large, and it is worth reemphasizing that these findings arise while controlling for additional measures of US affinity (foreign aid and trade), in addition to numerous country-level controls. Additionally, it is worth noting that US military alliances tend to be highly durable over time, and predominantly pre-date the period under study here—making it unlikely that these results are an artifact of alliance formation decisions being shaped by human rights practices themselves.

These results stand in contrast to most previous qualitative and quantitative examinations of the Country Reports, which generally conclude that foreign policy bias results in US allies receiving less scrutiny of many human rights issues, particularly physical integrity rights. Instead, our results show the precise opposite relationship, at least for the estimated topics most closely reflecting physical integrity rights, as well as for prison conditions. One possible interpretation is that while earlier examinations focused primarily on cases of foreign policy bias during the Reagan administration, these were not representative of the full relationship across all countries and subsequent administrations. It is also possible that, in response to criticisms of foreign policy bias during the Reagan administration, US military allies now receive additional attention and scrutiny in their reports. That is, extra attention in the Country Reports may aim to pre-empt criticism that US allies receive overly favorable treatment with regards to physical integrity rights violations and prison conditions. US allies also receive substantially less attention to several other topics, including Ethnic and Minority Rights, Religion and Citizenship, Labor Rights, and Terrorism and Torture.

We find a number of similar results in our examination of the relationship between US foreign aid and topic prevalence. Countries that receive more US aid tend to receive greater scrutiny of several topics: Killings and Disappearances, Terrorism and Torture, Elections and Parties, and Ethnic and Minority Rights. Aid recipients also tend to receive less attention to several additional topics, including State and Non-State Violence, Human Trafficking, Freedom of Movement, and Religion and Citizenship. Hence, these relationships exhibit similar potential foreign policy biases to the findings for US allies discussed above, particularly as aid recipients receive greater scrutiny of some physical integrity rights.

US trade partners, on the other hand, receive substantially greater attention to Freedom of Movement and the Justice System, and smaller degrees of greater attention to Human Trafficking and Religion and Citizenship. However, countries that trade more with the United States also receive less attention to Labor Rights, Prison Conditions, Ethnic and Minority rights, and Humanitarian Crises. In this case, the evidence suggests a potential foreign policy bias in the direction that has been suspected by some previous scholars (Foot Reference Foot2001; Mertus Reference Mertus2004): countries receive less scrutiny of Labor Rights (the topic most directly relevant to trade) as they trade more with the United States.

In contrast with our findings regarding topic attention and countries’ relationships with the United States, we find no clear evidence of biases arising from systematically varying characteristics of US domestic politics. While much qualitative and quantitative research has discussed differences across US presidential administrations in the content of the reports, we find no evidence of systematic differences between Republican and Democratic administrations for any of the 15 topics. In the results for Presidential election cycles, the estimated relationships for all topics are either 0, or very close to 0, with strikingly little uncertainty. Finally, we also find no meaningful results for the extent of Congressional control by the President’s party. This is despite the fact that Congress itself put in place the legal requirement for the State Department to prepare the Reports in the first place, and has often clashed with the executive branch over their content.

These findings may imply, in the aggregate, that US domestic politics have not systematically biased the reporting practices of the State Department’s Human Rights Reports.Footnote 8 It should be noted, however, that these conclusions do not preclude the possibility that more complex relationships remain, such as interactive effects between US politics and foreign policy. Furthermore, the lack of cross-sectional variation in our sample for these US domestic variables suggests that these null findings should be interpreted with some caution.

An important check on the validity of our approach comes from the results for the relationship between external measures of human rights practices and the prevalence of each topic. While there is no perfect variable to capture objective “on-the-ground” human rights conditions, the most advanced option at present is Fariss’s (Reference Fariss2014) dynamic latent human rights protection measure. One potential concern with our approach concerns our assumption that “attention” to a topic is necessarily negative. However, this assumption is largely borne out, at least for the topics most relevant to concern for physical integrity rights. Better scores on the latent human rights measure are associated with lower prevalence of the topics reflecting Killings and Disappearances, Terrorism and Torture, State and Non-State Violence, Freedom of Expression, and Humanitarian Crises.Footnote 9 Conversely, this means that countries with worse latent human rights scores tend to receive greater attention to these topics, suggesting that attention is indeed negative. On the other hand, countries with better scores on the latent measure tend to see greater prevalence of topics reflecting Labor Rights, New Rights Issues, and several other topics to a lesser extent. This finding is more complex to interpret, suggesting either that countries may indeed receive positive or neutral attention on these topics, or that countries without major violations of physical integrity rights tend to receive greater negative attention toward other topics than they otherwise might.Footnote 10

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper evaluates whether the content of US State Department Country Reports on Human Rights Practices has varied over time, space, and as a function of domestic politics and bilateral relationships. To do so, we apply a newly developed machine learning technique, the STM, to a corpus of reports covering 1977–2012. We find that the 15 core topics uncovered by this analysis—including Labor Rights, Human Trafficking, and Killings and Disappearances—do indeed vary significantly across time and space. Further, we find that relationships with the United States have significant effects on topic prevalence, whereas purely domestic US political factors do not. These findings both validate the STM’s application to human rights reports, and refine our understandings of their potentially strategic nature.

Scholars have often assumed, based on evidence of bias in favor of US allies during the Reagan administration, that allies are likely to receive less attention to violations of physical integrity rights. We, however, find the opposite. Our results show that US allies’ Country Reports include greater attention to topics of Killings and Disappearances, State and Non-State Violence, and Prison Conditions. This suggests a particular concern with monitoring and disseminating information concerning human rights violations committed by military allies. On the other hand, we find that US trade partners tend to receive less attention to Labor Rights, lending some support to more critical assessments of the Reports.

One limitation to these conclusions is the difficulty in disentangling variation in on-the-ground human rights practices from State Department reporting biases. Although our efforts to control for numerous baseline factors help to minimize these concerns, they do not eliminate them. This remains an important task for future research. Another limitation is the relationship between report lengths and report topics. Our approach models each document as a mixture of topic proportions that sum to 1, regardless of report length. While we think it most appropriate for our purposes to examine relative attention within each report, future work should investigate different approaches.Footnote 11 These challenges notwithstanding, we believe our approach can complement existing measures derived from human rights reports.

Our findings of systematic shifts in the Country Reports’ content over regions and time complements existing research (Clark and Sikkink Reference Clark and Sikkink2013; Fariss Reference Fariss2014; Richards Reference Quinn, Monroe, Colaresi, Crespin and Radev2016) that discusses the potential for information effects and increasing standards of accountability. We propose topical attention shifts as a distinct—though related—dimension of human rights monitoring, shaping the topics considered worthy of attention and scrutiny in the first place, alongside matters of information availability and access, and the classification of actions as abuses. Topical attention shifts can have both formal sources, due to new Congressional requirements or administration guidelines, or informal sources, including international norm dynamics, audience demands, and foreign policy biases. The yearly topical proportion measures that can be derived from our analysis—which we provide as a supplement to our paper—directly capture these shifts in topical attention over time. Our annual measures of topical attention shifts can be used as a control, or combined with existing measures, to enable researchers to account for attention shifts within analyses of existing measures.

Finally, our approach also demonstrates the utility of topic models in studying human rights reports and other foreign policy documents. Future research should build on the approaches taken here to further study the connections between political information and political processes. Many such documents claim to contain authoritative or objective information on countries or other entities (Kelley and Simmons Reference Kelley and Simmons2015), yet are produced by human agents subject to organizational and political pressures. These methods offer a fruitful way to study such documents in ways that embrace, rather than ignore, those processes.