Following three decades of meandering journeys through the major cities of Ming China, Fang Yongbin 方用彬 (1542–1608) had acquired several hefty trunks stuffed with name cards, invitation letters, short shopping lists, the odd invoice, and a couple of colorful hand-bills. His assorted slips came in a wide range of shapes, textures, and sizes, some dyed pink or green with golden flecks, others cut to resemble veined plant leaves, or stamped with fret-pattern borders and woodcut images of mythical birds. Rather than discard such delicate ephemera, Fang fastidiously kept hold of these materials, noting a nagging concern, in an encomium (shiyu 識語) dated to 1601, that they might become “fodder for silverfish.”Footnote 1 Adopting the guise of a romantic sojourner, Fang claims to have acquired many of his papers from gatherings at estates and gardens dotted throughout the Yangzi river delta: his words suggest a lingering attachment to these documents as tokens of the “absent physical body” of their writers.Footnote 2 And yet, behind his boasts of a commitment to “past friendships,” an underlying preoccupation with the allure of celebrity and the radically altered possibilities of commercial activity in the sixteenth century starts to come into view.Footnote 3 Indeed, a significant quantity of the surviving notes addressed to Fang altogether eschew the restrained conventions of epistolary literature to openly recount the details of payments in escrow, pledges for loans, and outstanding debts of silver. Many of these transactions, in turn, center upon the constituent materials of the cache itself: ink, samples of luxury stationery, and handcrafted papers.

In the course of his travels—from Guangdong in the deep south to Beijing in the north; from Suzhou in the east to Huguang in the west—Fang Yongbin (also named Sixuan 思玄; courtesy name Yuansu 元素; literary name Yijiang 黟江) had managed to obtain business cards and swathes of handwriting from some of the most renowned cultural figures in sixteenth-century China.Footnote 4 In his list of 618 contacts, leading poets and high-ranking government officials mingle with hereditary princes, fashionable courtesans, and military commanders, not to mention a host of aspiring students and peddlers from his hometown in Huizhou 徽州 prefecture.Footnote 5 Fang himself held no such claim to fame: born into an unassuming branch of a merchant lineage, he was virtually unknown in the centuries following his death. It was only when his cache of paperwork—733 handwritten notes and 190 name cards—happened to be purchased in Japan at the end of the Second World War and was brought to Harvard University, where it was rediscovered by the historian Chen Zhichao 陳智超 in 1997, that Fang's far-reaching engagements with Ming material culture once again became legible.Footnote 6

The Fang Yongbin cache (catalogued as Notes from Select Luminaries of the Ming (Ming zhu mingjia chidu 明諸名家尺牘)) remains an utterly singular resource for the study of late Ming information networks. It is extraordinarily rare, to begin with, to find any original correspondence from the sixteenth century, let alone such a sizeable corpus of manuscripts all received and preserved by a single person—Fang's cache remains the largest-known collection from the Ming.Footnote 7 The earliest note can be dated to 1564 (Jiajing 43) and the latest to 1598 (Wanli 26), allowing readers to trace firsthand Fang's travels, fluctuating fortunes, and the vicissitudes of his personal relationships over a thirty-four year period.Footnote 8 Many of the papers can be classified as “notes” (chidu 尺牘, shujian 書簡, daobi 刀筆), brief “practical” missives with a mundane and straightforward demeanor, in contrast to the studied elegance of a literary “letter” (shu 書).Footnote 9 Fang categorizes his documents—divided into seven folios titled sun (ri 日), moon (yue 月), metal (jin 金), wood (mu 木), water (shui 水), fire (huo 火), and earth (tu 土)Footnote 10—as “letters and poems” (jiandu shici 柬牘詩詞), “short name-cards and notes” (duanci shouzha 短刺手札), and “cards of formal invitation and regrets” (fuli qing cixie zhi tie 夫禮請辭謝之帖).Footnote 11 The contents of the cache, however, distend and exceed the framework of epistolary practice: notes are juxtaposed, for instance, with a range of other paper-based ephemera, from account bills (zhangdan 賬單) to name-brand advertisements for a line of local tea (fangdan 仿單).Footnote 12 Taken as a whole, the archive serves as a stark reminder both of how little is still known about the myriad uses of handwriting in Ming society—a corrective to oversimplifying views of early modern China as a “print culture”—and how many other similar sets of documents may have been lost to the ravages of time. This stash of “paperware” affords precious insight into dynamic, yet largely ephemeral modes of written communication that flourished beyond the pages of the Ming woodblock book.Footnote 13

How, then, did Fang Yongbin gain access, at least momentarily, to such a distinguished clientele? How did he use ostensibly private manuscripts to generate and sustain such levels of publicity? The answer is hidden in plain view for anyone who has an opportunity to handle the contents of the Harvard-Yenching cache: these informal shopping lists are drafted on sensuous sheets of decorative paper with refined brushwork, colored ink, and elegant seal impressions. When Fang's acquaintances sought him out, they did so with choice items of studio paraphernalia, materials that Fang then collected and preserved for posterity, as if he were compiling his own catalogues of stationery, calligraphic models, or seal designs. Fang saw himself and was seen by others as an aficionado of desktop supplies, and the terse messages scrawled across the many papers in his cache return time and again to the buying and selling of the “Four Treasures of the Scholar's Studio” (wenfang sibao 文房四寶)—inkstones (yan 硯), inkcakes (mo 墨), brushes (bi 筆), paper (zhi 紙)—and related accessories: water dippers, hand-wrests, brush-holders, and seal stamps.Footnote 14 Luxury writing materials constituted a medium for Fang's communications with his patrons, and were also commodified as tokens of exchange between these parties. It was Fang Yongbin's role in the making and marketing of the material paraphernalia of calligraphy, or the appurtenances of a scholar's desk, that became a primary source of his income and ultimately propelled his short-lived stint in the cultural limelight: Fang's was a life lived with and through the technologies of ink and paper. The primary aim of this article is to use the Harvard-Yenching cache to demonstrate how the social lives of writing materials in late Ming China engendered new alignments between aesthetic pursuits, mercantile experience, and craft knowledge.

From a broader historical perspective, the documents Fang Yongbin packed away in his rattan boxes uniquely attest to the profound impact of the business in calligraphic tools on the changing social landscape of early modern China. To begin with, the cache sheds new light on the workings of the “scriptural economy” of the Ming, or the “dynamic totality” of devices, formats, and techniques that shaped experiences of writing.Footnote 15 In an expanded sense, the notion of a scriptural economy might also be taken to cover the trade in substances, substrates, and implements that sustained the powerful function of calligraphy as a technology of socialization. If the physical condition of the Harvard-Yenching cache—the arrangement and layout of Fang's papers—illuminates unsuspected channels of writerly exchange in Ming China, the swathes of messages addressed to Fang reveal the ways in which dealership in writing tools constituted a testing-ground for historically unprecedented improvisation with social roles. Late Ming history has largely been narrated from the perspective of men who were distinguished for wielding the brush, yet the Harvard-Yenching cache registers the increasingly powerful influence exerted over the business of culture by those skilled in both the making and marketing of such implements: largely forgotten entrepreneurs whose services made the art of writing possible in the first place. Ultimately, the cache invites further reflection on whether those who produced and sold writing tools could disrupt or manipulate the reigning conditions of the “culture of wen 文” (writing, literature, civility).Footnote 16 Could these entrepreneurs lay claim to, or usurp custodianship of the material culture of calligraphy?Footnote 17 Were these figures—working in the “infrastructural subbasement of Chinese script”—able to influence the ways in which writing was valued and understood?Footnote 18 To what extent, this article asks, was a character like Fang Yongbin able to envision alternative models of knowledge and action, or to develop forms of inquiry and inventiveness that were less constrained by entrenched hierarchies of head over hand.

The Huizhou Entrepreneur: From Status to Skill

The Harvard-Yenching cache attests to a powerful interchange between the trade in writing materials and new constellations of cultural expertise in the late Ming, yet this relation is largely predicated upon economic developments and forms of social organization that were relatively unique to Huizhou prefecture in the late sixteenth century. Fang's papers afford unparalleled insight into the dynamics behind the emergence of the “Huizhou entrepreneur” in the Ming, encouraging a shift in attention from the problem of the merchant's social standing to the novel combinations of skill that transformations in Huizhou commercial activity spurred and sustained.

Much ink has been spilled on the question of status in relation to upheavals in late Ming material culture. Historians, largely inspired by the work of Pierre Bourdieu, have noted how members of the gentry turned to the “invention of taste,” particularly in the Wanli era, to protect besieged conceptions of decorum, trying to preserve their privilege as cultural gatekeepers in the face of threats to traditional bases of economic power.Footnote 19 The extensive commercialization of the sixteenth-century Chinese economy had led members of families engaged in trade—historically denigrated as the lowest of the “four occupations” (simin 四民) in Confucian social theory—to lay claim to the trappings of literati identity, particularly through purchasing degrees and the acquisition of antiquities.Footnote 20 At the same time, due to the difficulties involved in sustaining a career in an increasingly dysfunctional civil service, educated students were forced to pursue commercial opportunities in order to make a living.Footnote 21 The question of how to possess luxury objects—or how to properly behave as a consumer of things—was, by the late sixteenth century, central to far-reaching negotiations over the labels available to an individual for self-identification.

In trying to account for the convulsive social transformations of the late Ming, historians have started to reject deterministic categories like “class” or “status,” noting how they fail to convincingly capture changing models of human agency.Footnote 22 The practice of the late Ming Huizhou entrepreneur further unsettles conceptions of “scholar” (shi 士), “merchant” (shang 商), and “artisan” (gong 工) as discrete or predetermined entities. As Joseph McDermott has demonstrated, pressure on forested mountain land had prompted families in Huizhou prefecture to develop trusts for the sale of timber, aiding the emergence of a local futures market in the late fifteenth century.Footnote 23 These lineages, in turn, repurposed the institution of the ancestral hall as a credit association and “proto-bank,” financing members to move into markets throughout the Yangzi delta.Footnote 24 With the transition from a grain–salt exchange system to a new policy of “paying silver for salt,” institutionalized in 1491, prosperous Huizhou merchants replaced their counterparts in Shanxi and Shaanxi as the dominant power bloc in the highly lucrative salt business.Footnote 25 During the sixteenth century, Huizhou lineages started to strategically alternate between encouraging their sons to pursue careers in the civil service and trade, so that a single family could earn scholarly respectability, while developing extensive commercial networks.Footnote 26 Under such circumstances, it seems more productive to think of “scholar” and “merchant” as roles—modes of performance that tried to meet certain felicity conditions in different contexts and for different ends—rather than exclusive or intrinsic occupational categories inherited at birth. A single figure could alternate between both roles at different points in life, rejecting an ontology of distinction (“either/or”) for an ethics of synthesis (“this and that”).

Fang Yongbin was born into a Huizhou merchant lineage and studied for the exams, seeking throughout his career to substantiate self-claims as a scholar. And yet, his practice extends beyond what has conventionally been said of the “Confucian merchant” (rushang 儒商) or “gentry merchant” (shishang 士商). As Xu Min 許敏 has suggested, despite a wealth of studies attending to the late Ming mixing of shi and shang (and concomitant efforts to police these distinctions), there are few biographical accounts of how someone born into a family of traders might participate in, shadow, or eventually impact the culture of wen: Fang Yongbin's case allows historians to shift their focus away from literati-authored polemics and prescriptions to place a young businessman at the center of the story, observing with an unprecedented level of detail how such a figure might have made and remade a name for himself.Footnote 27 In a compelling study of Huizhou salt merchants from the eighteenth century, Yulian Wu has asked whether the paradigm of status negotiation elides “the possibility that merchants might identify, understand, and enjoy themselves outside the realm of literati-merchant competition.”Footnote 28 The Harvard-Yenching cache allows one to pose a similar question for an earlier era, where amid rampant boom and bust, the contours and prospects of the market for things were being drastically reconfigured.

More specifically, Fang Yongbin's career suggests how negotiations over the roles of scholar and merchant might be triangulated through involvement in the sphere of craft, or the tacit art of working with materials. Much of the discussion of how merchants sought to position themselves as scholars has focused on the problem of conspicuous consumption: how people presented themselves through their possessions.Footnote 29 Fang Yongbin's practice, however, invites a shift in focus from the definition of a consumer's identity to questions of expertise and skill: not what someone was, but what they were able to do.Footnote 30 This article departs from a focus on literary representations of merchants in late Ming sources to examine how the practice of the Huizhou entrepreneur opened up a “middle ground” where learned knowledge, technical competence, and trade might be integrated to constitute a mode of hybrid expertise.Footnote 31 The emergence of this repertoire became intimately intertwined with the development of the late Ming business in writing implements. Just as these things-in-motion forged new channels between the domains of the market, the workshop, and the scholar's studio, so too, those who made and sold them developed novel strategies for blending skills in connoisseurship, salesmanship, and handiwork, artfully synthesizing learned and practical knowledge of materials.Footnote 32 The Harvard cache reveals an expanding web of interlocking connections between Fang's poetry on paintings and calligraphic scrolls, his activity as a pawnbroker versed in the pricing and exchange of artwork, a travelling dealer and connoisseur of inkstones, a salesman and manufacturer of ink and paper, a carver of seal stamps, and a collector of ancient scripts. Fang's career was, in this respect, characterized by what might be termed a “leitmotif of mobility,” evinced not only in his extensive travels throughout the empire, but in his ability to journey across and undermine the boundaries between hitherto segregated fields of knowledge and action: he was, in Ursula Klein's words, a “hybrid expert.”Footnote 33 Fang refrained from conceptualizing such hybridity, yet his practice nevertheless elucidates early portents of what by the High Qing—through an alliance between Manchu statecraft and the managerial prowess of Huizhou salt merchants—had come to constitute the field of the “cultured and cosmopolitan man” (tongren 通人).Footnote 34

In what follows I examine how Fang Yongbin variously improvised with the roles of “scholar” (as a purchased licentiate and aspiring poet), “merchant” (as a pawnbroker and shopkeeper), and “artisan” (as papermaker, inkmaker, and seal carver), refining and adapting different sets of skills, while channeling his capital into new endeavors. There has been a recent boom in Chinese-language studies of the Fang Yongbin papers, aided in part by the publication of Chen Zhichao's annotations and notes.Footnote 35 This article is primarily intended to introduce both the cache and critical work on Fang Yongbin to an English-language audience, while identifying the central dynamic behind Fang's multi-faceted career and his sprawling collection of paper-based ephemera: namely, the interplay between his entrepreneurial persona and skill in the design and retail of writing implements; in his contributions to shaping the material culture of calligraphy. More generally, I depart from recent Chinese scholarship on Fang Yongbin by shifting attention from the question of his social status to the configuration and development of his multidimensional expertise. Moving between different sets of artifacts—from inkstones to seal stamps—the structure of the article loosely approximates one of the many shopping lists addressed to Fang Yongbin, foregrounding the diversity of the materials he worked with, and the different sets of skills such work required. A larger question remains as to how unique Fang's story really is, or whether it is simply the uniqueness of his archive that matters. Understanding his involvement in the trade in writing tools constitutes a first line of response to this interpretative dilemma, revealing something of the co-creation of man and his materials, suggesting how Fang transformed himself through his papers, and how—long after his death in poverty—such durable ephemera might remake our own perceptions of the times in which he lived.

Worldly Scholar

Born into one of twenty branches of the Fang 方 clan based in Yansi Market Town 巖寺鎮, Yongbin was brought up in a merchant household whose members conducted trade between Huizhou and Yangzhou, a prosperous port city on the Grand Canal.Footnote 36 With no prior history of exam success among his direct male ancestors, Fang's early aspirations for a scholarly career and his access to eminent contacts beyond Huizhou stemmed instead from his relationship with a powerful local patron named Wang Daokun 汪道昆 (1525–1593), an acclaimed prose stylist and one-time Vice Minister of War. It was through Wang Daokun, for instance, that Fang Yongbin was able to interact with the acclaimed Ming general Qi Jiguang 戚繼光 (1528–1588), fresh from violent anti-pirate campaigns in Fujian, and to participate in publicizing the sensational tale of the scholar Zhang Yaowen 張堯文 (1544–?), returning, after eighteen days, from the dead.Footnote 37 In a more general sense, Wang governed the direction of Fang's literary education and advocated for his pursuit of a degree. The Fang Family Genealogy (Fangshi zupu 方氏族譜), meanwhile, notes that Yongbin married into the larger Wang clan, indicating extended kinship ties that subtend and inflect what became a student–teacher relationship.Footnote 38 Given Wang's empire-wide fame as both a statesman and a literary celebrity, Fang's loyalty to his patron seems eminently pragmatic, the more intriguing question then becomes what Fang Yongbin might have offered to Wang in return. In responding to this question, we can begin to gauge how Fang's aspirations and activity as a poet or a self-proclaimed “worldly scholar” (shiru 世儒) connected to his expertise in handicrafts and shop-keeping. More generally, Wang and Fang's relationship illumines the interplay between two distinct models of Huizhou cultural endeavor in the late Ming: Wang Daokun represents an effort to defend the standing of mercantile lineages through political office and in established literary media; Fang—representative of a younger generation—worked under this umbrella to chart and practice new alignments between the scholarly arts, trade, and craft knowledge.

Huizhou vs Suzhou: Late Ming Tournaments of Value

Himself the scion of a Huizhou salt merchant lineage, Wang Daokun won prestige for his clan when he earned the jinshi degree in 1547 in the same cohort as the Suzhou scholar Wang Shizhen 王世貞 (1526–1590)—eventually the dominant intellectual in the late-sixteenth-century world of letters—and Zhang Juzheng 張居正 (1525–1582), a controversial Grand Secretary under the Longqing 隆慶 (1567–1572) and Wanli (1573–1620) emperors. The vicissitudes of Wang Daokun's subsequent official and literary careers were largely defined by his relationships with these two men: Zhang played a role in Wang Daokun's promotions to assistant Censor-in-Chief in 1570 and right Vice Minister of War in 1572; Wang Shizhen, meanwhile, promoted Wang Daokun's classical prose at an early stage, inviting his erstwhile classmate to enter the highest echelons of the Ming literary scene.Footnote 39

Wang Daokun and Wang Shizhen later became known as the “Two Simas” (Liang Sima 兩司馬), both because their official ranks were deemed comparable to the ancient Sima civilian military officers and their literary talents were seen to be worthy of the Han dynasty rhapsodist Sima Xiangru 司馬相如 (179–117 BCE) and historian Sima Qian 司馬遷 (145–90 BCE).Footnote 40 As the fame of the “Two Simas” spread as far as Chŏson Korea, both men were treated within literati communities of the Yangzi river delta as opposing leaders in a broader regional competition between the localities of Huizhou and Suzhou. This rivalry reached a tipping point in a notorious potlatch-style gathering on the Yellow Mountains (Huangshan 黃山) hosted by the two Wangs.Footnote 41 One hundred amateur aficionados—local leaders in everything from calligraphy and the music of the qin to football and pitch-pot—were allegedly invited from Suzhou and paired with counterparts from Huizhou in a “tournament of value”: a periodic event removed from the routines of economic life, where the “rank, fame, or reputation of actors” was reconstituted through contests to determine central tokens of value in Ming society: poems, paintings, and works of calligraphy.Footnote 42 It is unclear whether or not this event ever actually occurred (and if it did, whether Fang Yongbin might have attended), yet the tournament serves as an apposite framework for understanding the contests between Huizhou and Suzhou in the late Ming, where personal prestige became invested in “arresting or diverting” the passage of these accessories of gentility.Footnote 43

The fraught rivalry between Wang Daokun and Wang Shizhen extended from poetry to the practice of art collecting and connoisseurship. Between the death of Wen Zhengming 文徵明 (1470–1559) and the rise of Dong Qichang 董其昌 (1555–1636) around the turn of the seventeenth century, Ming China lacked a single pre-eminent connoisseur with the power to decisively authenticate artworks, creating a vacuum that gave rise to an unprecedented degree of regional competition between different factions striving to promote the collections and collectors of their hometowns.Footnote 44 Wang Shizhen sought to rigorously defend the cultural hegemony of Suzhou landowning gentry, while Wang Daokun—as a nominal spearhead of the fashion for collecting in Shexian 歙縣—looked to justify the efforts of Huizhou merchant lineages in their acquisition of antiquities.Footnote 45 Fang Yongbin's entrepreneurial activities can be set against this backdrop: his improvisation with strategies of connoisseurship, salesmanship, and craft took advantage of, and was made possible by, a prevailing uncertainty in the late sixteenth century as to whether the representatives of Huizhou or Suzhou might eventually gain the upper hand in matters of taste-making.

The very first note preserved in the Harvard cache is addressed to Fang from Wang Shizhen, and can be dated to late 1589 in Nanjing.Footnote 46 It concerns a postscript Wang Shizhen had recently composed for Fang Yongbin's scroll of four Tao Yuanming 陶淵明 (365–429) poems drafted by the widely commended Cantonese calligrapher Li Minbiao 黎民表 (1515–1581), a figure with whom Fang had studied brushwork in Guangdong and Beijing.Footnote 47 The exchange clearly mattered less to Wang Shizhen than to Fang Yongbin—he even mistakenly transcribed Fang's cognomen Yuansu 元素 as Taisu 太素—and yet the case still demonstrates that by the late sixteenth century, perhaps the most renowned scholar in the empire might deign to discuss matters of calligraphy, in writing, with a travelling Huizhou salesman. Behind Wang Shizhen's fumbled address to Fang Yongbin—who momentarily shifts positions from student and dealer to patron—lurks a grudging realization of the entrepreneurial businessman's growing participation in shaping the culture of wen.

Poetry of Association: Wang Daokun's Fenggan Society

While Wang Daokun's reputation as the foremost literary authority in Wanli-era Huizhou stemmed from his exam success and subsequent official appointments, he sustained his dominance over local scholarly activity through running a series of poetry societies. These organizations were notionally intended to foster homegrown literary talent, yet also came to function as a mechanism through which Wang Daokun extended his influence over developments in late Ming material culture. Due to turbulent factional politics at court, civil service tenure had become increasingly precarious, leading scholars to turn to poetry societies as a way of reaffirming ideals of communal leadership, fashioning a “world of their own” around principles of worthiness and talent.Footnote 48 Wang Daokun spent nineteen years of his life in forced retirement and similarly took advantage of his coterie to buttress his standing as a community role model or fan 範.Footnote 49 And yet his management of these societies diverged from other contemporary examples through the heightened emphasis he placed on cultivating the careers of figures involved in the making and marketing of things. With the establishment of his Fenggan Society (Fenggan she 豐干社), in 1567, Wang Daokun developed a dynamic model of local patronage, wherein he offered young men like Fang Yongbin the opportunity to gain literary credentials, while he took advantage of their business operations to bolster his own collections, generating social credit and further revenue for his family.Footnote 50 Wang Daokun effectively used the Fenggan institution to offer up access to an aura of scholarly renown in exchange for a connection to resources in trade and craft.Footnote 51

Named after a local river in Shexian, the Fenggan Society initially consisted of seven members in addition to Wang Daokun and his brother and cousin, four of whom came from Fang Yongbin's extended family.Footnote 52 Wang claims to have founded the Society in order to aid in the literary education of Wang Daoguan 汪道貫 (1543–1591; courtesy name: Zhongyan 仲淹) and Wang Daohui 汪道會 (1544–1613; courtesy name: Zhongjia 仲嘉)—named the “Two Zhongs” (Er Zhong 二仲)—and it was his sibling and cousin who, in turn, first brought Fang Yongbin into the group. Wang Daokun appears to have already taken an interest in meeting with Fang Yongbin, as is recorded in a letter in the Harvard cache from an enigmatic figure who simply went by the character Shu 淑. The letter divulges Wang's hope to invite Fang to discuss the classic of Han dynasty historical writing, Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji 史記):

My uncle met with Master Nanming [Wang Daokun] and in their discussion of literary matters, he said you are dedicated to writing. He [Daokun] was delighted and suggested that you might find an opportunity to talk with him. If you proceed to his residence, he will go over the Records of the Grand Historian with you.

家伯見南明先生,因論文,道兄尚文墨。渠甚喜,謂兄何不于渠處一談。若往渠宅,渠當謂兄講《史記》。Footnote 53

Wang Daokun further embraced his role as Fang Yongbin's teacher in a dedicatory essay that begins with an injunction that the young man—“the son of a wealthy family” (富家翁子)—“humble himself to become a scholar” (無寧折節為儒).Footnote 54 In Wang's account, Fang was initially taken aback by the suggestion, referring to himself as a “worldly scholar” (shiru), a self-deprecating epithet—evoking a clerkish mentality—that he would later use elsewhere as a signature:Footnote 55

He heard my words and was solemnly stirred within. He withdrew and thoughtfully stated: “I am deficient, how could I really become a scholar? If I keep on as a worldly scholar, would that be sufficient? … To sincerely follow noble teachers in receiving instruction at college, to proceed and steal a glimpse of an imperial chariot procession, an abundance of officials from all ranks, the rites of delegations at suburban altars, the regalia of summoned officers; to then withdraw and study the words of the many masters and scholars of broad learning, to befriend gentlemen from all over the empire, for me this is enough.”

生聞余言,灑然有慨於中矣。退而深念曰: 「用彬不敏,又惡能儒? 藉使紛如為世儒,世儒安足為也?。。。誠願從先生往受業成均,進而竊睹萬乘之尊,百官之富,郊廟朝會之典,公車召對之儀,退而治博士諸家之言,友天下之士,於余小子足矣。」Footnote 56

Wang Daokun's ventriloquized version of Fang's response perhaps says more about himself than his protégé: by having Fang effuse over the transformative experience of entering the National Academy (Guozjijian 國子監), Wang once again publicizes his own achievements in winning the jinshi degree, inviting younger Huizhou merchants to imitate and uphold his example. Such recommendations eventually led Fang to travel to Beijing in 1573 to sit for the exams; he appears to have been unsuccessful, however, and he later settled on purchasing for money a “licentiate degree” (jiansheng 監生) through the common yet increasingly maligned practice of juanna 捐納.Footnote 57 While Wang Daokun provocatively challenged rigid bifurcations between scholar and merchant in his literary prose, once posing the question: “in short, in what way is a good merchant inferior to a prominent scholar?” (要之,良賈何負閎儒), the authority to make such pronouncements and the genres in which he worked remained those of an archetypal official.Footnote 58 Fang Yongbin, by contrast, may have felt resigned to the self-effacing label of a “worldly scholar,” yet he proceeded to blend learned, mercantile, and artisanal expertise in practice.Footnote 59

Fang Yongbin failed in his pursuit of a civil service career, yet he was still able to use his experience of Wang Daokun's tutelage to garner modest acclaim as a poet.Footnote 60 Fang appears to have performed various literary secretarial tasks for his patron: clients, for instance, approached Fang with requests for family tomb memorials from Wang. Fang was also involved in printing copies of Wang Daokun's 1574 collection of literary prose and poetry, Fumo 副墨.Footnote 61 Unlike other early members of the Fenggan Society, Fang did not publish a print collection of his own verse, yet fellow alumni shared manuscripts and dedicated poems to him, suggesting that his literary talents were taken seriously by his peers.Footnote 62 A forty-leaf album dedicated to Fang Yongbin, acquired by Robert Van Gulik (1910–1967) and now held in the Leiden Institute of Sinology (catalogued as “A Memorial Folio for Fang Yuansu's Glorious Return” (Fang Yuansu ronggui jinian ce 方元素榮歸紀念冊)), has also recently been brought to light, containing 104 poems from eighty-two poets—the majority of whom also drafted letters in the Harvard-Yenching cache.Footnote 63 Shi Ye 施曄 has suggested that these handwritten drafts of poems addressed to Fang Yongbin were probably compiled along with the letters now in the Harvard-Yenching collection, only to have been separated into another folio at a later date.Footnote 64 Just as we have no surviving examples of the many missives Fang likely sent in response to the requests he received from clients, so too, we can only surmise—at least at this stage—the not inconsiderable quantity of verse that Fang must have composed to sustain relations with the eighty-two poets listed in the Leiden album.Footnote 65

What little has survived of Fang Yongbin's verse relates almost exclusively to paintings that he inscribed or collected: his poems on ekphrastic themes, displayed on the surfaces of fans and scrolls, point to the intimate relationship between Fang's literary aspirations and his engagement—as both dealer and maker—with the material culture of calligraphy.Footnote 66 A fellow Ming dynasty Huizhou scholar's collected works preserves a poem with Fang's seals dedicated to a depiction of his garden, first included in an illustrated anthology of go-charts.Footnote 67 The Qing dynasty compendium, Catalogue of Calligraphy and Painting from Ten Hundred Studio (Shibai zhai shuhua lu 十百齋書畫錄), contains another of Fang's few extant poems, a transcription of a piece originally written on an ink painting of bamboo.Footnote 68 Shi Ye has suggested that two of the four categories of poems addressed to Fang in the Leiden folio concern paintings: the first, a horse painting to commemorate Fang's trip to Beijing to enter the National Academy; and the second, a scroll or set of paintings on a bamboo grove dwelling.Footnote 69 The moon folio in the Harvard cache, meanwhile, contains a poem in praise of a “beauty painting orchids,” the first two lines of which—“Consort Jiang has worked well, with first buds of orchid and calamus; moonlight illumines the banks of the Xiang, washed in evening mist” (江妃修好初蘭荃,月映湘皋澹晚煙)—conceal the characters for “Orchid” 蘭 and “Xiang” 湘, naming the celebrated Nanjing courtesan and ink painter Ma Xianglan 馬湘蘭 (1548–1604) (Ma Shouzhen 馬守真; Ma Ruqian 馬汝謙).Footnote 70 The aforementioned Qing painting catalogue, Ten Hundred Studio, also cites another reference to a landscape scroll, offered to Fang Yongbin by a Nanjing-based Buddhist monk named “White Foot” (Baizu 白足) that bears a poem dedicated to Fang signed by Ma.Footnote 71 Aside from these two poems—likely intended as a pair of tokens in a parting exchange—there are unfortunately no further details concerning the nature of Fang's relationship with one of Ming China's leading female celebrities. While there are no surviving paintings attributed to Fang Yongbin, the Harvard cache indicates that he repeatedly sought out work from his contemporaries, often on fashionable themes—in one instance, soliciting a Guanyin 觀音 scroll from a female gentry painter.Footnote 72 While direct commissions for Fang's own paintings were rare, clients repeatedly request for him to draft his “large characters” (dashu 大書)—a reference to clerical script (lishu 隸書)—on folding fans, suggesting that he had earned local acclaim for his brushwork following his aforementioned lessons with Li Minbiao.Footnote 73

In tracing Fang Yongbin's transactions with paintings and works of calligraphy, however, we can begin to see conventional practices of gift-giving among aspiring late Ming scholars give way to other matters of business: clients come to Fang with paintings they hope to value for a sale or pawn for a sum of silver.Footnote 74 Fang's own requests for commissions—as with the Guanyin painting—were accompanied by gifts of ink and paper, supplies he manufactured and marketed through his own shop.Footnote 75 If Fang's poetic activities were entwined with his role in the exchange of paintings and calligraphy, his role in managing the passage of such artwork was, in turn, indelibly marked by his expertise in selling writing materials. There is, in Fang Yongbin's case, no conversion from merchant to scholar (or its inverse, from aspiring scholar back to merchant)—rather we are left with a knotty tale of self-extension that proceeds in fits and starts, where Fang's learned skills in poetry or calligraphy on occasion surpass, sometimes harness, and yet more often seem to merge with his involvement in handicrafts and shop-keeping.

Shopkeeper

Fang Yongbin solicited and sustained many of his contacts through his management of a shop and pawnbroking business named the “Treasure Store” (variously transcribed as: Baodian 寶店; Baosi 寶肆; Baopu 寶鋪).Footnote 76 It is unclear where precisely in Yansi Market Town the store was located or how many other branches of this franchise were set up in Shexian, yet the business appears to have been a family-run outfit.Footnote 77 Fang's “Treasure Store” specialized in the commercial sale of what Chen Zhichao calls “cultural commodities” (wenhua shangpin 文化商品)—or the appurtenances of a scholar's studio—and moneylending. These two sets of activities, to a degree that remains unrecognized in existing cultural histories of late imperial China, were often mutually constituted as two sides of the same operation.

In the absence of a widespread network of deposit banks,Footnote 78 consumers sought to convert their money into social credit through conspicuous consumption.Footnote 79 As a dealer and pawnbroker, Fang Yongbin catered to such demands: he facilitated the acquisition of decorative objects and could covert such supplies back into hard cash when it was required. Pawnbrokers assume a particularly influential role in settings where the “neutral exchange” of money and commodities develops alongside networks of obligation and personal connection in which material is “richly absorbent” of memory.Footnote 80 We encounter a not-dissimilar situation in sixteenth-century Huizhou where an expanding money economy had begun to destabilize and reconfigure the “paternalistic order of the agnatic community” and gentry-dominated lineage institutions.Footnote 81 Under these circumstances, a given luxury object—a green jade inkstone, say—could oscillate between its guise as a commodity with a calculated cash value and its life as a “material mnemonic” of status, of momentous occasions, of kinship ties. The pawnbroker lived on the “social cusp” between an “intermittent yet persistent” need for cash and this world of “material memories.”Footnote 82 Across the papers of the Harvard cache, we see Fang take in family heirlooms for sums of money, while selling artifacts that were then recycled as gifts, assuming an almost alchemical power to transmute silver into art and art back into silver. From the pawnbroker's perspective, such work drew from and synthesized strategies of discernment and dealership, simultaneously manipulating a customer's tastes and debts.

A Pawnbroker's Invoice

Nestled among the papers collected in the fire folio is an invoice sent from Fang to a customer named Wu Shouhuai 吳守淮 that gives a better sense of how he made a living (see Figure 1).Footnote 83 Drafted on an elegant sheet of decorative paper with an illustrated border of the “four gentlemen” (plum blossom, orchid, bamboo, and chrysanthemum), Fang's bill lists the sums of silver that Wu owed from earlier loans:

Invoice for Brother Wu Shouhuai:

I have set out below the numbers and dates for the amounts of silver and artifacts taken out by brother Wu Shouhuai.

1) Third Year of Wanli, 14th of the First Month: 10 taels of silver taken out.

2) Sixth Year of Wanli, 13th of the First Month: 5 taels of silver taken out.

3) Sixth Year of Wanli, 24th of the Third Month: 3 taels of silver taken out.

Total = 18 taels

1) Fifth Year of Wanli, 19th of the Eighth Month: 5 artifacts taken out, priced at 10 taels and 5 mace.

2) Fifth Year of Wanli, 22nd of the Twelfth Month: 31 paintings and artifacts taken out, priced at 27 taels and 5 mace. Also: Sixth Year of Wanli, 2nd of Eleventh Month—a single white porcelain vase.

Total = 38 taels

Figure 1. Invoice for Wu Shouhuai. Image courtesy of Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Combined Total of Silver and Artifacts = 56 taels

吳守淮兄帳。

今將吳守淮兄那銀日期併去玩器數目開列于後:

一,萬曆三年正月十四日去本文銀拾兩。

一,萬曆六年正月十三日又去文銀伍兩。

一,萬曆六年三月廿四日又去文銀叄兩。

三共本銀一十八兩。

一,萬曆五年八月十九日去玩器五件,該價銀一十兩五錢。

一,萬曆五年十二月廿二日又去畫,玩等物三十一件,該價銀二十七兩伍錢。又萬曆六年十一月初二日又去白瓷觚一個。

古玩共該價銀三十八兩。

銀,玩總共五十六兩。Footnote 84

The invoice reveals how Wu availed himself of Fang's services as a pawnbroker over a four-year period, drawing both silver and decorative objects or “playthings” (wanqi 玩器) from his shop. The terse format of the bill, however, partly obscures the background to Fang and Wu's relationship. Both individuals were select members of Wang Daokun's seven-man coterie, the Fenggan Society, and Wu was the author of the single largest number of letters to Fang in the Harvard cache.Footnote 85 If Wang Daokun used the Fenggan group to harness the skills of its members in trade and craft, the younger participants in the Society appear to have concurrently relied on each other's contacts to pursue the acquisition of things and to take advantage of basic financial services. Twelve of the letters collected in the moon, metal, wood, and water folios reveal a casual friendship between the two men, with Wu addressing Fang in an informal manner through use of his courtesy name.Footnote 86 Wu alludes to the acquisition of pots of sweet flag (changcao pen 菖艸盆), new brush washers (xin bixi 新筆洗), and orchid fragrance incense (lanxiang 蘭香), yet much of the discussion—befitting their acquaintance as fellow members of Wang Daokun's literary society—concerns the convivial exchange of poetry and calligraphy: in one instance, Wu even shared what appears to have been a manuscript of his poems (“clumsy drafts” 拙稿) with a provisional title “Warm Spring Pavilion” (Yangchun ge 陽春閣).Footnote 87 The tone and content of the correspondence changes markedly, however, in the letters from the fire folio. From this point onwards, Fang appears increasingly impatient in trying to get Wu to repay his debts. There are several references to a cauldron-shaped inkstone made from green jade (luyan yu 緑研玉) that Wu borrowed and had neither returned nor paid for.Footnote 88 Fang sent representatives to try and extract payments for this artifact (and other outstanding sums) as Wu became increasingly resentful, venting that “your barbaric lackeys had come for this matter” (候胡奴至了此前件) and challenging him, “why fashion such vulgar airs?” (作此里中俗態何也).Footnote 89 It seems unlikely that Fang Yongbin was ever repaid in full, as biographies of Wu Shouhuai all claim he died in poverty. Nevertheless, Fang still benefitted from artifacts that Wu had turned in as pledges for loans and repayments for earlier debts: to take one telling example, he acquired a “Huangting Classic” calligraphic model (Huangting jing tie 黃庭經帖) from Wu Shouhuai, once owned by Wu's uncle, that he then lent out to another close associate and fellow Fenggan Society member: Wang Daokun's younger brother, Wang Daoguan.Footnote 90

Inkstone Connoisseur

Through his familiarity with the handling and pricing of decorative objects, Fang Yongbin assisted Wang Daokun with the expansion of his acclaimed collections. Fang's services for Wang's family, however, were largely mediated through the “Two Zhongs”—Wang Daoguan and Wang Daohui. The extensive correspondence between the Wangs and Fang Yongbin reveals a complex web of different modes of exchange and of diverse objects—porcelain, mirrors, paintings, calligraphy, books—that bound the two parties together, yet a persistent concern in many of these letters is the acquisition of inkstones. In several cases, we see the Wangs cast themselves as customers, writing simply to purchase artifacts from Fang. In the eighth letter in the metal volume, for instance, Wang Daohui identifies a blue and white porcelain “hanging vase” that he encountered on a visit to Fang and sends his younger brother back to buy:

Yesterday I paid thanks. I am most grateful for you accompanying me for the whole day. As for the blue and white porcelain hanging-vase, would it be possible for me to entrust my younger brother to come and pay you? Unfilial Wang Daohui lays his forehead to the ground.

昨拜謝,辱追陪竟日,感感。青花壁瓶,乞便付家弟,嗣當償償,如何?不孝汪道會稽顙。Footnote 91

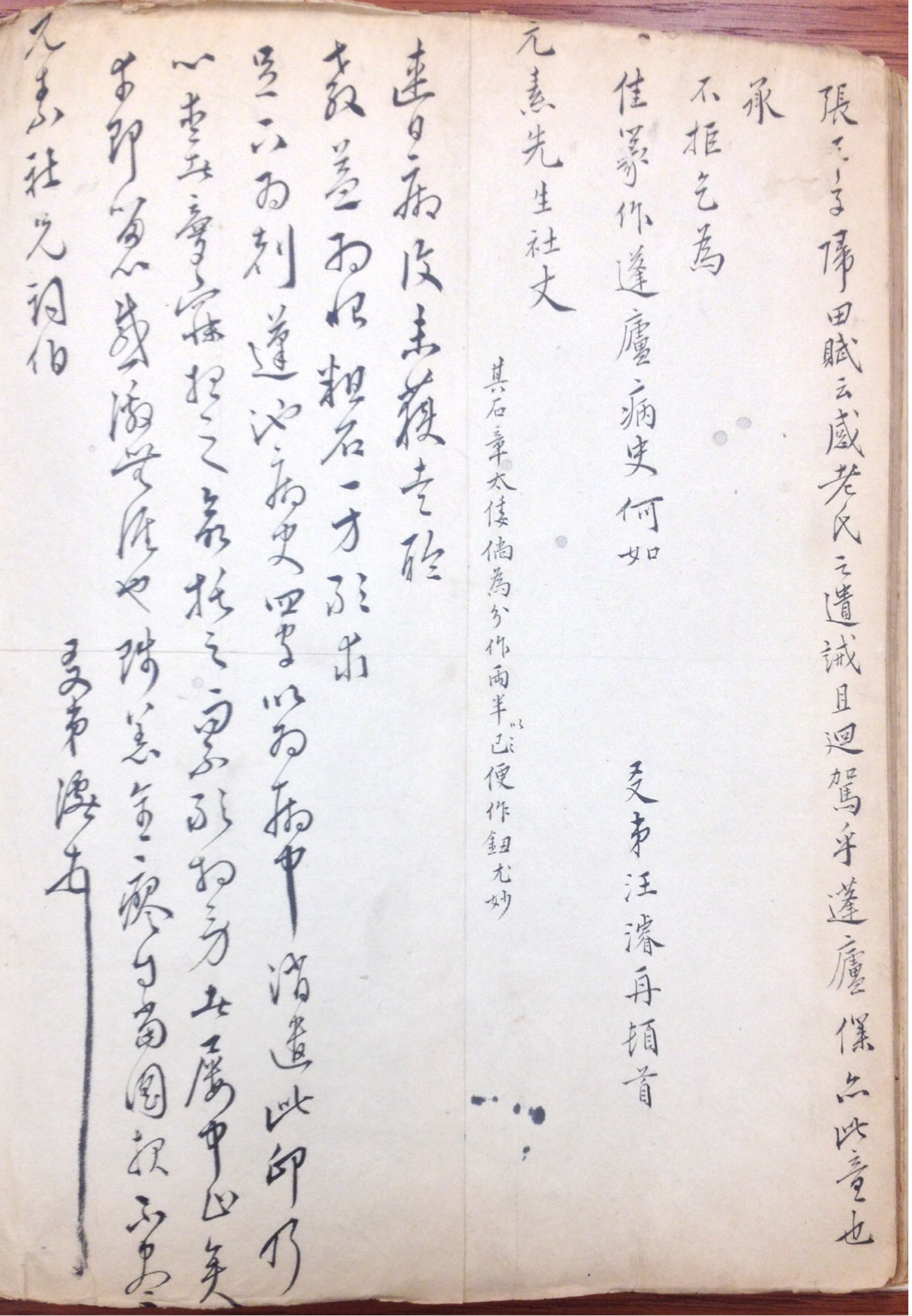

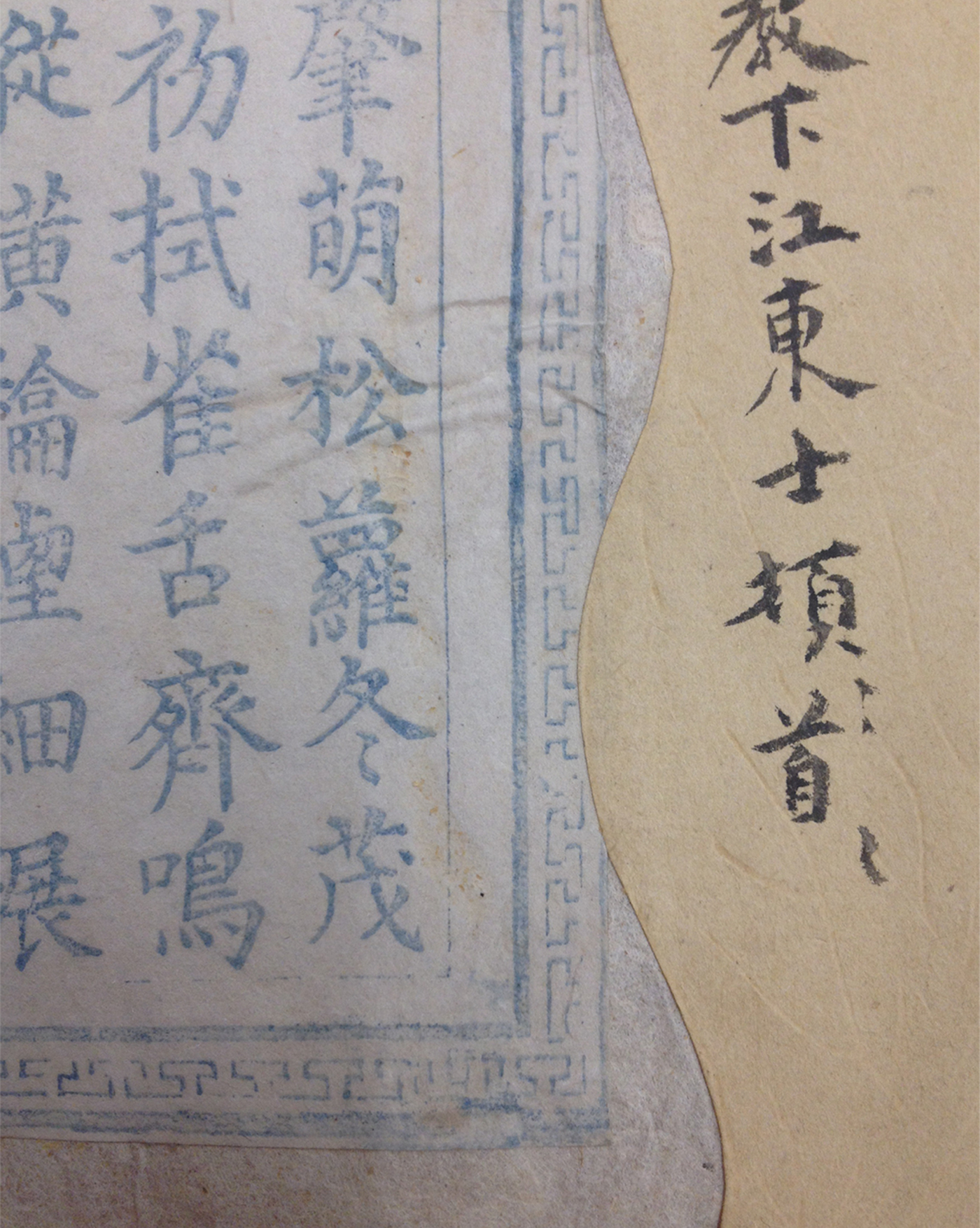

Much of the correspondence, however, suggests a messy entanglement of purchases, pledges for loans, repayments for debts, gifts, and non-binding temporary exchanges of possessions for trials or tests. An illustrative example is a longer letter from Wang Daoguan, scrawled while he was suffering from an illness (Figure 2). The note begins with Wang returning to Fang Yongbin a set of five paintings that he had borrowed temporarily, before notifying him that he will be holding on to some of the other paintings and artifacts taken out on loan for longer than anticipated. Wang then names paintings that he says his “brother” (we can take to be Wang Daohui) will come and collect, although it is unclear whether he plans to purchase or simply borrow them. Wang proceeds to remind Fang how his associate Cheng Zhuchuang 程竹窗 had entrusted Wang Daohui to purchase an inkstone, while enquiring about the price. Along with the letter, Wang Daoguan sends to Fang Yongbin a Duan inkstone (that he hopes to pawn for a five or six mace discount in the price for the inkstone Cheng wants Daohui to buy) and asks Fang to settle the remaining balance together with the money he owed for an earlier purchase of books. The letter concludes with Wang Daoguan writing of his cousin's intention to purchase a copy of the “Poems of Forty Tang Masters” (Tang sishi jia shi 唐四十家詩) and a painting by a Suzhou artist from Fang; Daoguan insists that before he sends the money he wants to view the items once more.Footnote 92 Other notes in the cache show that Fang's shop sold inkstones and Wang Daoguan's letter suggests that some of this stock may have come from inkstones that clients had pawned to him.Footnote 93 Moving from lists of objects to sums of money, from debts repaid to purchases made, the letter approximates the format of a ledger, tracing the development of an open account with Fang's shop.

Figure 2. Letter from Wang Daoguan to Fang Yongbin. Image courtesy of Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

The Wangs not only looked to Fang Yongbin for assistance with the purchase of inkstones, they also started to approach him as an expert in the refined judgment of such artifacts. In a letter from the metal folio, Wang Daohui begins by listing a set of items he hopes to exchange before inviting Fang Yongbin to judge a “large and rare inkstone” that he had recently acquired:

I've offered two bowls to swap for a caltrop mirror. If you want to use the porcelain cup, come and collect it at a later date. As for the matter from a few days ago, there have been a few setbacks but I'll wait until I see you to tell you in full. As for the peacock feathers you wish to send me, I'll get one of my lads to fetch them, how's that? I recently obtained an inkstone, an exceptional specimen; what day could you come to appraise it? Brother Hui bows his head.

二碗持易菱鏡。磁杯如足下欲用,他日當取至。前日之事,就中多少周折,俟相見面盡之。足下瓶內所置孔雀尾數莖願與不佞,即令豎子持下如何?近得一研,大是世間希有之物,何日來一鑒賞也?弟會頓首。Footnote 94

It is striking that Wang uses the term jian shang 鑒賞 to call upon Fang to appraise the object. This reversed form of the more conventional compound shang jian 賞鑒—glossed as shang “to discriminate on the grounds of quality” and jian “to tell genuine from false”—was taken to denote “true” connoisseurship: “dependent on a combination of deep scholarship with lofty moral qualities” and was frequently contrasted with hao shi 好事 (fondness for things), a term for shallow dilettantism.Footnote 95 It is unclear from the letter what precisely Wang Daohui wanted from Fang Yongbin, whether a judgment on pricing, authentication of the object, or just plain flattery for his skills as a collector. In any event, it is striking that a man with privileged access (through his cousin Wang Daokun) to both the largest art collection in Huizhou and to the famed collections of Wang Shizhen in Suzhou, should start to address a travelling businessman as if he possessed the “power of eyes” (muli 目力) or “power of mind” (xinli 心力) usually reserved for a cultivated scholar.Footnote 96 Wang's deference to Fang nevertheless makes a point that while never explicitly articulated in the diaries of self-proclaimed collectors might now seem self-evident: to become a successful dealer, one had to master practices of authenticating and discriminating art in order to outsmart one's customers.Footnote 97 The truly accomplished dealer was, in this sense, always already a connoisseur.

This partnership between the Wangs and Fang Yongbin led to their collaboration on a series of joint publishing ventures. The first, was a catalogue of headgear (guanpu 冠譜); and the second, a manuscript catalogue of seal-stamp impressions (yingao 印稿)—neither of which survive.Footnote 98 In both instances, it is difficult to ascertain to what extent these publications were initiated by the Wangs seeking out Fang's assistance as a shopkeeper to market the prestige of their family holdings, or by Fang soliciting help from the Wangs to promote the merchandise of the Treasure Store.

Carver

The Harvard cache shows that customers repeatedly approached Fang Yongbin for his talents in handicrafts. Various letters specifically refer to Fang's personally crafted dyed papers (zase zizhi xiaojian 雜色自製小箋; waiji shi suo zhi caijian 外記室所製彩箋)Footnote 99 and requests for supplies of ink allude to his “Abstruse Treasure” (Xuanbao 玄寶), a possible brand name for a line of products.Footnote 100 It would be reasonable to infer that a considerable number of notes in the cache were written with supplies that Fang Yongbin had sold to his clientele. While Fang had clearly earned a reputation in both of these fields of craft, he was more widely recognized for his extensive engagement with artisanal knife-work, particularly the carving of seal script (zhuan 篆) into private seal stamps (yin 印; zhang 章). During the late Ming, research into forms of zhuan that had existed prior to Li Si's 李斯 (280–208 BCE) modifications of the regional scripts of the late Zhou became a critical field of activity in scholarly circles, as philologists sought to recover models of the sages from early inscriptions.Footnote 101 Against this backdrop, Ming literati became increasingly preoccupied with the more mundane problem of how to transfer seal script calligraphy, drafted with the brush, into the durable medium of a stamp, molded with a knife. Scholars had, traditionally, hired artisans to carve their handwriting onto bronze or ivory bodies, yet in the late sixteenth century the question of who wielded the brush and who wielded the knife became fraught with broader significance: could a scholar release himself from his dependency on an artisan? Could an artisan pass as a scholar?

Clients commissioned Fang Yongbin to manufacture seals in a range of materials, predominantly bronze and ivory. In the following note, a fairly illustrative request from Fang's collection, a customer specifies his general preferences for four personal seals with an enclosed sum of one tael of silver as payment:

My humble self still lacks several seals of different kinds; I've attached another design and trouble you to find an opportunity in your spare time to complete it. Use ivory or use bronze, it's really up to you. If you use bronze, make it tall and slender. It's far better if you don't add a knob to it. I've also enclosed one tael of silver as remuneration. I respectfully request your aid in carving four copies and I'd be grateful for your examination of them. The name has been corrected. Respectfully Huang Xueceng. In haste. Enclosed please find one tael.

不佞尚乏數圖書各色,具別幅,煩公暇中一成之。或用牙,或用銅,俱隨便。然銅宜用高長,勿以鈕為之更妙。外具折儀壹兩,小刻四册侑敬,幸檢入。名正具。侍生黃學曾拜。速。折儀壹兩。Footnote 102

Fang Yongbin's skill in engraving seals seems to have been linked to his ability to carve other artifacts—including ivory and bamboo hairpins (yazan 牙簪; zhuzan 竹簪).Footnote 103 A letter from the wood folio suggests that Fang not only sold bronze and ivory seals, but that his shop also peddled knives for cutting these materials: “I humbly request a knife to carve bronze and a knife to carve ivory, please don't be sparing, my sincere thanks” (鎸銅并鎸牙刀各丐一柄,幸勿恡,容面謝。).Footnote 104 While not all of the requests explicitly indicate that Fang personally cut the seal (in some instances, he may have also procured the services of other artisans through his shop), he was praised for his talents as a carver by his customers:

This sobriquet I received from you is truly wonderful; I can't express my gratitude. The design of the “Fount of White Clouds” cannot surpass this. The poise of the calligraphy and the finesse of the engraving lie in the virtuosity of this refined hand's movements. It was certainly not the work of a lesser craftsman.

承贈賤字妙甚,感不可言。白雲源規模不過如此。其間字畫之均勻,鎸鏤之精絕,又在高手運移之巧,非區區所能盡也。Footnote 105

The author of this note celebrates Fang Yongbin's craft, claiming he bettered a rival with the popular title “Fount of White Clouds” (Baiyun yuan 白雲源) through his deft ability to synthesize calligraphy (字畫) and carving (鎸鏤). Some of Fang's customers went further by requesting that he share his seal designs as a method of instruction: “as for the art of engraving insects, could you please instruct us? It would be better, if possible, for you to show your designs—I would be awfully grateful.”Footnote 106

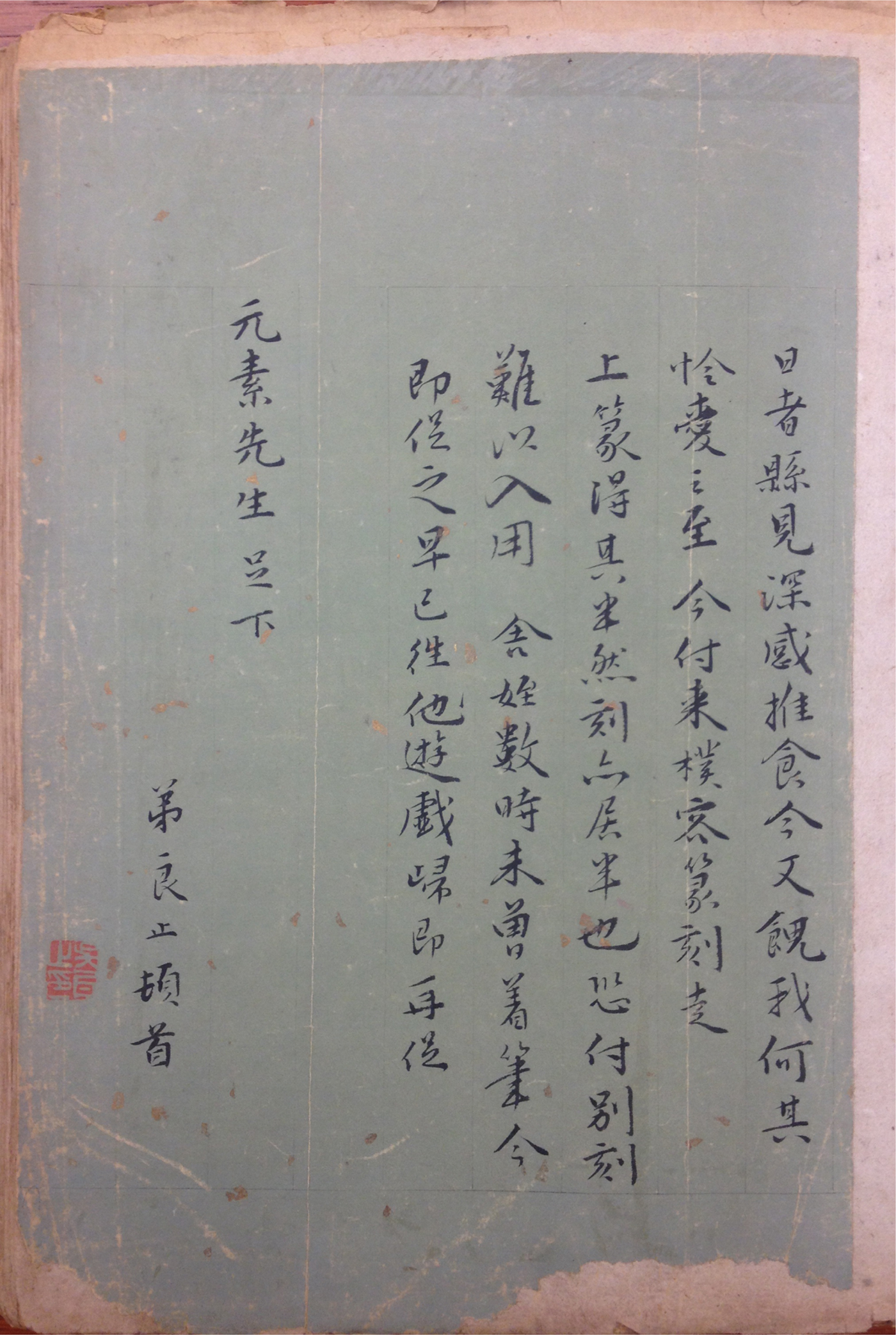

Although Fang, like other hired artisans, seems to have primarily engraved seals for clients in ivory and bronze, there is also evidence in the Harvard cache that he carved script in stone. Wang Jun 汪濬, a kinsman of Wang Daokun, for instance, sent a pair of letters asking Fang to carve a personal seal in “fieldstone” (粗石一方). These two notes are particularly striking for the pathos of Wang Jun's candid description of how he arrived at a phrase for his seal, recounting the process of devising an apt epithet to articulate his diminished physical state (Figure 3). Wang Jun died from his illnesses at the age of twenty-five (Wang Daokun commemorated a man “prone to sickness” 善病) and we see him search in his requests for redemption from convalescence, as if he still believed in the apotropaic powers of seal script:

For the past several days my illness has returned; that I still haven't been able to heed your instruction only adds to my regrets. As for this block of fieldstone, I request that you carve the four characters: “Ailing Historian of Penglai Pond” as a way of diverting me from my sickness. I have my heart set on this seal; I've been dreaming of it. I've wanted to entrust you to do it, but haven't dared to trouble you. I hope you'll pay mind to this and my gratitude would be boundless. When I fully recover from my sickness, I'll make sure to repay you in full.

連日病復,未獲走聆教益為恨。粗石一方,敢求足下為刻「蓬池病史」四字,以為病中消遣。此印乃心愛者,夢寐想之。欲托之而不敢相勞者,屢中止矣。幸即留心,感激無涯也。賤恙全療,自當圖報不盡。Footnote 107

Zhang Pingzi's Rhapsody on Returning to the Fields has a line that reads: “Moved by the warning left by Laozi, I shall turn my carriage back to my thatched hut.” I'll take this meaning for myself. If it is not too much to bear, how about you carve “Ailing Historian of the Thatched Hut” in fine seal script? Your younger brother Wang Jun, respectfully submitted to Master Yuansu, the society elder.

This stone seal is too short. If you could cut it in two and then use it to make a knob for another seal, that would be wonderful.

張平子「歸田賦」云:「感老氏之遺誡,且迴駕乎蓬廬。」僕亦此意也。承不拒,乞為佳篆作「蓬廬病史」如何?友弟汪濬再頓首。元素先生社丈。 其石章太倭,倘為分作兩半,以便作鈕,尤妙。Footnote 108

Wang begins in the first note with the title “Ailing Historian of Peng Pond,” invoking the specter of his mortality,Footnote 109 before later turning to a line from Zhang Heng's 張衡 (78–139) Rhapsody on Returning to the Fields (Guitian fu 歸田賦)—“Moved by the warning left by Laozi, I shall turn my carriage back to my thatched hut”—to bestow upon himself a new moniker, “Ailing Historian of a Thatched Hut” (蓬廬病史). This line serves as a critical pivot in Zhang's rhyme-prose, marking the point when the protagonist leaves behind “the perfect pleasure of rambling and roaming, even as the sun sets, oblivious of fatigue” (極般遊之至樂,雖日夕而忘劬。)—to heed Laozi's injunction that “galloping and hunting cause one's mind to become mad,” heading back to his hut to practice the zither and calligraphy. Fang Yongbin's seal for Wang Jun no longer survives, yet the request conjures up a compelling role for the hired engraver, or the entrepreneurial figure of the shopkeeper more generally: as a medium through whom other customers might fashion poetic projections of themselves. While the main body of the letter dwells on the significance of the phrase intended for the seal, with the customer displaying his skills in literary citation for the carver, it is followed by a short postscript in smaller characters that requests for an old stone to be refabricated as the knob for a new stamp (Figure 3). This slight detail again hints at Fang's artisanal expertise—or his tacit knowledge of how to manipulate materials with the knife—skills that exceeded mere literary craft.

Figure 3. Letter from Wang Jun to Fang Yongbin. Image courtesy of Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Fang Yongbin as a Seal Collector

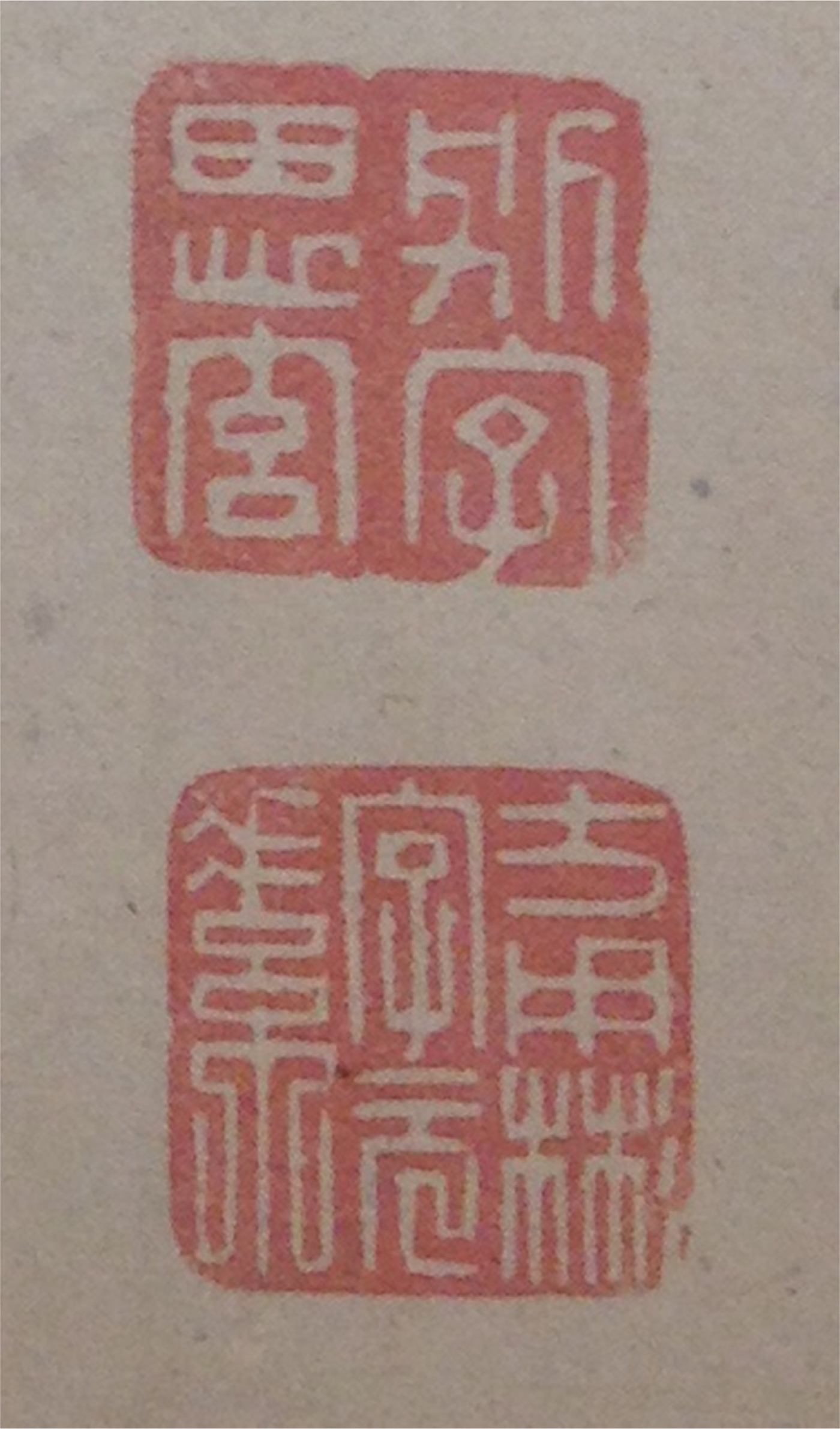

The Harvard cache shows that in addition to his work in retail, Fang corresponded with other prominent seal carvers of the late sixteenth century, notably the renowned cutter Wang Hui 汪徽 from Wuyuan (Figure 4), and the local engraver Wu Liangzhi 吳良止, a native of Xinan 溪南 in Shexian (Figure 5). In these letters, we see Fang assume for himself the guise of a client intent on collecting seal designs. In his first letter from the cache, Wang Hui refers to Fang with the intimate epithet of “the one who knows me” (zhiji 知己) and identifies a piece of jade that he had sent as the material for the seal:

I am grateful to you, my true friend, and have received the jade seal you want me to make to express the virtue of your name, for you to wear at your belt. The other day I thought about it and brought it out to play with. I haven't carved a jade seal for a good decade or so, but now I have gone back to it, itching to test my skills for my true friend.

弟感足下知己,敢留玉印一方作足下表德,為足下佩之,它日相思,持以把玩也。弟不為人篆玉章已十數年所矣,今復技癢于知己之前耳。Footnote 110

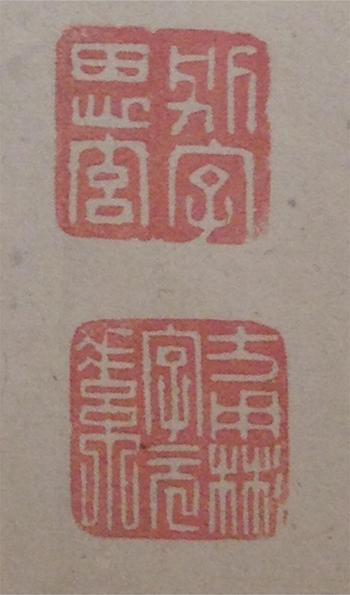

In a subsequent letter from the metal folio, Wang returns the seals he had carved to Fang Yongbin with two stamped impressions appending his note: both personal seals were based on Fang's literary names: “cognomen, Sixuan” (biezi Sixuan 別字思玄) and “Fang Yongbin, courtesy name: Yuansu” (Fang Yongbin zi Yuansu 方用彬字元素) (Figures 4 and 6).Footnote 111 In the course of four letters in the cache to the bronze cutter Wu Liangzhi, we similarly see: 1) Fang send Wu material for carving a seal; 2) Wu journeys to Yansi Market Town to try and obtain Fang's seal script (yinwen 印文) for the carving (possibly from the Treasure Store), but unfortunately Fang was not in; 3) Fang send Wu a gift of ink and a recently cut collection of poems trying to re-arrange a meeting; 4) Wu finally send Fang a bronze seal with his name.Footnote 112 The first of these letters bears Wu Liangzhi's personal seal and was drafted on a sensuous sheet of green decorative paper with flecks of gold (Figure 5). One of the more ornate samples in the Harvard cache, this piece speaks to Fang's investment in soliciting and collecting the calligraphy and seal impressions of his contemporaries. Indeed, one way of approaching the cache is as a carefully curated repository of around one hundred personal and leisure seals from prominent scholars of the sixteenth century, as Fang's own private “seal catalogue” (yinpu 印譜).Footnote 113 We know that Fang collaborated with Wang Daokun's brothers in the production of a manuscript of seal impressions, yet it is unclear whether this contained contemporary or antique designs. The Huizhou connoisseur Zhan Jingfeng, however, wrote to Fang Yongbin to applaud his proprietorship of ancient seal scripts: “I heard that your recent acquisition of ancient seal designs is particularly rich and would relish the chance for you to display them one by one.”Footnote 114 Such flattery, like Wang Daohui's earlier invitation to appraise the inkstone, points to Fang's newfound recognition among his peers as a connoisseur, yet still retains faint traces of the obsequiousness befitting a former customer of Fang's pawnshop. An earlier letter from Zhan Jingfeng reveals that he had approached Fang for a loan of over thirty taels of silver to cover a trip to the National Academy.Footnote 115 In these moments, we catch glimpses of Fang Yongbin—a dealer and carver—impinging upon the practice and purview of epigraphic scholarship.

Figure 4. Letter from Wang Hui to Fang Yongbin. Image courtesy of Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Figure 5. Letter from Wu Liangzhi to Fang Yongbin. Image courtesy of Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Figure 6. “Cognomen, Sixuan” and “Fang Yongbin, Courtesy Name: Yuansu,” Seal Impressions by Wang Hui, on letter from Wang Hui to Fang Yongbin. Image courtesy of Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

The Invention of the Soft-Stone Seal: Scholar vs Artisan

Fang Yongbin's work as a carver took place against a backdrop of profound changes in understandings of the seal. During the late sixteenth century, the “rediscovery” of soft-stone (“gelid rock” (dongshi 凍石) or soapstone (a hydrous aluminum silicate resembling talc)) heralded the emergence of “literati seal carving,” a movement that—as Bai Qianshen has demonstrated at length—exerted a profound influence on the aesthetics and politics of late imperial calligraphy.Footnote 116 Scholars had conventionally relied on hired artisans to carve their brushwork into the durable medium of a stamp, yet following a legendary tale of the retrieval of a batch of “gelid rock” in Nanjing by Wen Peng 文彭 (1498–1573)—the son of the illustrious Suzhou scholar-painter Wen Zhengming—renowned men of letters supposedly took up the knife themselves.Footnote 117 These developments led to a rethinking of the status of the seal stamp: what was once an assemblage wrought from the collaboration between commissioned artisans (skilled in knifework) and scholar-calligraphers (skilled in brushwork) gave way to a new vision of the stamp as an “authentic” alignment of mind, trace, and impression—an ideal synthesis of knife and brush that allowed for a more direct, or spontaneous mode of self-expression through writing. In the wake of Wen Peng's momentous discovery, commentators distinguished the soft-stone “scholar's seal” (wenren zhi yin 文人之印) from the “artisan's seal” (gongren zhi yin 工人之印), a synonym for stamps wrought from bronze, jade, or ivory.Footnote 118 Artisanal carvers were denigrated for “relying on copies and being unable to approach antiquity” (依樣臨摹,靡不逼古), while artisans who carved jade (a material that was too hard for self-proclaimed scholars to manipulate) were told they did not understand seal script and so lost the “intent of the brush as the methods of the ancients were abandoned” (玉人不識篆,往往不得筆意,古法頓亡).Footnote 119

The popularization of soft-stone seal carving can be traced to Wen Peng and his student He Zhen 何震 (c. 1530–1604). In standard versions of their biographies dating from the early Qing, Wen discovers a batch of soft-stone at a stall in Nanjing: he realizes the true value of the material only after he witnesses a shopkeeper refuse to pay a haggard old man for retrieving the load, a detail that underscores a symbolic opposition between Wen's acquisition of the material and the workings of the marketplace.Footnote 120 Wen then displays the rock for none other than Wang Daokun,Footnote 121 who in turn gives half of the supply to He Zhen, thereby establishing the “Huizhou School” of seal-carving.Footnote 122 Wen, we are told, no longer needed to rely on a hired engraver of ivory fans to help carve his seals, bypassing the mediating presence of the artisan's knife.Footnote 123 Fang Yongbin's practice, however, exceeds and challenges this narrative of the rise of “literati seal carving.” On the one hand, Fang himself appears to have experimented with the new medium of soft stone: a letter in the water folio, for instance, records a request for Qingtian rock (承委青田石).Footnote 124 Fang likewise appears to have exchanged one letter with He Zhen: a note in the metal folio from a mysterious figure who takes the character Zun 遵.Footnote 125 On the other hand, however, Fang thwarts the distinction between “scholar's seal” (wenren zhi yin) and “artisan's seal” (gongren zhi yin), collapsing the very terms on which the discursive invention of literati seal carving was predicated: Fang carved in soft stones and in the hard “artisanal” materials of jade, ivory, and bronze; he drafted his own calligraphy and commissioned others to cut it with materials he sold through his shop; he was a craftsman and a salesman, yet also a proficient collector of antique scripts.Footnote 126 Where later scholars fetishized the soft-stone seal as a space of “mental refuge,” Fang embraced the production of a stamp as a means of networking, or of extending the franchise behind his name: he approached the seal as a hybrid medium, one that links together and in doing so transforms the relations between diverse collaborators, materials, and otherwise distinct forms of expertise.Footnote 127 It is in Fang's seal art that the roles of worldly scholar, shopkeeper, and artisanal carver converge, affirming his increasingly powerful contributions to the production and reproduction of wen.

Coda: Advertising Ephemera

The image of Fang Yongbin presented so far has been gleaned almost entirely from the requests of his clients in the Harvard cache. Fang himself ultimately remains an elusive and—aside from a single encomium, the invoice for Wu Shouhuai, and the impressions of his commissioned seals—largely absent figure within his own collection. There are no surviving letters from Fang in response to the many requests for purchases or hired services, so we have no way of knowing how he haggled his price or negotiated repayments on his own terms. We can, however, catch a glimpse of Fang's tentative attempts to present himself as an author in one of his few surviving literary compositions: an inscription for a brand of tea, “Fang Yongbin's Inscription for Pine Lichen Splendor” (Fang Yongbin Songluo lingxiu ming 方用彬松蘿靈秀銘).

This text, which appears on two thin slips of paper that were later mounted and preserved within the cache, was printed in blue ink with a bold red title in seal script framed by a key-fret border (Figure 7a and b).Footnote 128 One print of the inscription bears the added detail of Fang Yongbin's personal seal: “Master Sixuan” (Sixuan sheng 思玄生)—a supplement that together with the calligraphy of the title implicitly alludes to the author's reputation as a dealer of seal stamps (Figure 8).Footnote 129 We know from other letters in the cache that Fang Yongbin manufactured his own paper, prepared woodblock prints, and sold tea. In this light, these two pieces of ephemera further attest to his entrepreneurial practice, straddling and creatively combining different modes of cultural production.Footnote 130 Within the cache, Fang's promotional materials are juxtaposed with evidence of his other operations as a shopkeeper: the first copy of the inscription is mounted on a page together with a sheet of decorative golden leaf stationery bearing a request for advice on manuscript proofs—a pairing that seems to play on an implicit correspondence between Fang's list of leaves in his inscription and this finely rendered leaf-shape cut-out replete with vein patterning. The second copy of the “Pine Lichen Splendor” advert, meanwhile, is mounted alongside a letter fragment with a customer's request for a supply of brushes and paper from his shop (佳筆敢乞一枝。舊白箋啓乞數副。) (Figure 7a and b). While supposedly advertising tea, the presentation and production of these two flyers again speak to Fang's successful endeavors in the business of writing materials. Indeed, the “object” of Fang's inscription is not really tea, but the assemblage of the handbill itself, a testament to the expanding operation behind the production of the “Pine Lichen Splendor” label: Fang's deft ability to coordinate the manufacture of ink, paper, woodblocks, and seals, while channeling his capital into new ventures. Fang Yongbin is simultaneously poet, vendor, and maker, just as his “adverts” forge a novel synthesis between poetic composition, commercial labelling, and the artisanal engraving of script. In this sense, Fang's advertisements constitute a rare example of how the message, visual design, and material format of an inscription might all be traced back to the same hand.

Figure 7a. Handbill with “Fang Yongbin's Fineries of Mount Pine Lichen Inscription” pasted alongside letter from Jiang Dongshi to Fang Yongbin. Image courtesy of Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University

Figure 7b. Detail of Handbill with “Fang Yongbin's Fineries of Mount Pine Lichen Inscription.” Image courtesy of Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Figure 8. Handbill with “Fang Yongbin's Fineries of Mount Pine Lichen Inscription” pasted alongside letter from Qiu Tan to Fang Yongbin. Image courtesy of Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Located to the north of Xiuning 休寧 in Huizhou prefecture in Southern Zhili, Mount Pine Lichen 松蘿山 became a prominent site for the cultivation and processing of tea during the Wanli era. Wang Daokun was one of the earliest poets to write of his first-hand experience testing freshly plucked tea leaves on the mountain, adhering to a common trope in Ming tea poetry of inviting the reader to vicariously imagine the ambience of the plantation through the persona of the lyricist.Footnote 131 If Wang invokes the authority of his official title to endorse the tea, Fang Yongbin foregrounds the fate of the product's name:

Pine Lichen Splendor:

An outstanding scenic spot! The tea has started to bud.

Pine lichen flourishes in winter, while the bamboo shoots bud in spring.

“Dragon balls” are taken first, “swallow tongues” chirp together.

A “maidservant junket” offers up a gift, with “flagpoles” strewn across each other. With mist, finely ground; bringing rainwater to the boil.

Poured into a ceramic cup, nestled in a saucer.

Fit for a great worthy to sip, responding to its freshness as if waking from a dream. Passed into the annals of history, it will forever possess a fragrant name.

Inscription by Fang Yuansu of Xindu

松蘿靈秀:

地勝鐘英,茗柯肇萌。松蘿冬茂,笋乳春榮。

龍團初拭,雀舌齊鳴。酪奴投獻,旗槍縱橫。

和煙細碾,帶雨盈烹。陶罇當注,甆盞須傾。

高賢宜啜,醒夢應清。將垂青史,永擅芳名。

新都方元素銘。Footnote 132

“Pine Lichen” initially referred not to a particular tea leaf but to the processing methods that were developed on the mountain, and Fang is not so much concerned with any distinctive attributes of the product as with linking a medley of generic epithets for tea to the nascent celebrity of a local site.Footnote 133 The first four couplets simply list an array of exemplary tea leaves, punning on the component characters for these titles: “swallow tongues” chirping etc. In the second half of the inscription, Fang recounts step-by-step acts of preparing and drinking tea, tacitly inviting his readers to imagine the experience of testing the product for themselves. The poem concludes with Fang's claims for the prospective longevity of this “fragrant name,” by which he means to refer to the brand “Pine Lichen Splendor”—and yet his concern with renown betrays an investment in the broader reception of his own name in an appended “sign-off”: “Fang Yuansu of Xindu.”

During the late Ming, Pine Lichen’s reputation grew in stature, a trend attested to in the Wanli-era gazetteer for Xiuning county, which identifies a concurrent proliferation of counterfeits. A latent concern in this gazetteer entry is the way the name “Pine Lichen Tea,” attaining a level of celebrity that caused demand to outstrip supply, might lose its connection to a unique method (zhifa 製法) or locus of production, an anxiety that led to a comparison with Su Shi's 蘇軾 (1037–1101) proverbial “Heyang pig” (Heyang zhu 河陽豕). In this tale, Su sent someone to purchase pork from Heyang, which he had heard was exceptional, only for his intermediary to get drunk and miss out on the pig (which took flight at night). The man then offered up another type of pork to Su Shi's banquet guests who, erroneously assuming it was the famed product from Heyang, praised it as “incomparable” (以為非他產所能及也). The parable mocks those quick to judge a commodity on the basis of what they have been led to expect from its name:

Tea: The local mountain of the prefecture is named Pine Lichen on account of the many pines there: initially there was no tea. For a long time, the foothills were a source of betel palms, yet recently tea trees have been planted. A monk from a mountain monastery came across a processing method and developed it at Pine Lichen. The name took off and the prices of the tea soared. The monk made a profit and left his order for a secular life. People left but the name remained. The gentry sought out the tea of Pine Lichen and local managers had no way to respond and so followers wantonly sold fake products on the marketplace. Isn't this like what Dongpo said about the Heyang pig?

茶: 邑之鎭山曰松蘿,以多松名,茶未有也。遠麓爲榔源,近種茶株。山僧偶得製法,遂托松蘿,名噪一時,茶因踴貴。僧賈利還俗,人去名存。士客索茗松蘿,司牧無以應,徒使市恣贗售,非東坡所謂河陽豕哉!Footnote 134

We can no longer ascertain how successful Fang's promotion of the “Pine Lichen Splendor” title ended up becoming, particularly amid common late Ming criticisms that “Mount Pine Lichen” had garnered unwarranted acclaim. What remains is a powerful impression of the extent to which a brand had become a valuable product in and of itself by the late sixteenth century.

The design and physical format of Fang's endorsements offer a fleeting glimpse of a lost world of advertising media, ephemeral forms that shaped everyday experiences of the material world. These paper documents—often called “handbills” (fangdan) in later Chinese sources—represent an early example of a mode of commercial publicity that became increasingly widespread throughout the Qing dynasty. It was common, as Wu Renshu has noted, for traders to use handbills as wrapping paper or promotional inserts within a package of tea or medicine, providing informational text to endorse products under a particular trademark—very few examples of this form survive, however, from the Yuan and Ming dynasties.Footnote 135 While other notes in the cache haggle over the interpersonal exchange of things, Fang's handbills invite onlookers to imagine the consumption of a product—there is no longer any negotiation, deferral, or implied sense of reciprocity. When Fang speaks publicly in these printed inscriptions, he talks with and through his merchandise, appealing to his reader with a promise of access and the feigned illusion of exclusivity. In this final instance, he has no specific addressee in mind, only anonymous and by now altogether interchangeable customers.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to the two anonymous reviewers, Dorothy Ko, Judith Zeitlin, and Anne Feng for their advice and suggestions on earlier drafts. I would also like to acknowledge the generous support of the Michigan Society of Fellows.