In February 2014, armed and uniformed Russian soldiers entered Crimea, the Ukrainian territory. They seized control of the Crimean parliament, and shortly after a controversial referendum on the status of Crimea, President Putin signed the executive order on the accession of Crimea to the Russian Federation. This event marked the beginning of the diplomatic conflict between Ukraine and Russia, which has evolved into a military conflict in the east of Ukraine between the Ukrainian military and the Russian-backed separatists. The annexation of Crimea has also renewed tensions between Russia and the West, forcing Western governments to impose sanctions on Russia (BBC 2014a).

Nationalism is generally defined as a political ideology that advances the idea that the borders of the nation and the state should be congruent (Gellner Reference Gellner1983). Nationalism is a fluid ideology, and it may take many forms in one country. The dominant typology highlights civic and ethnic nationalism (Brown Reference Brown1999; Gledhill Reference Gledhill2005; Kohn Reference Kohn1944). Civic nationalism is based on more inclusive criteria for membership in a nation, such as citizenship, common territory, multiculturalism, and internationalism (Brown Reference Brown1999; Castles and Miller Reference Castles and Miller1998). Some scholars even conflate civic nationalism with patriotism (Billig Reference Billig1995; Brubaker Reference Brubaker2004). Ethnic nationalism advances a more narrow view of membership in a nation based on ethnicity, shared culture, religion, and history (Brown Reference Brown1999; Gledhill Reference Gledhill2005).

In this article, I primarily focus on nationalism in its ethnic manifestation since it has the potential to create social divisions, xenophobia, and violence (Gellner Reference Gellner1983; Hechter Reference Hechter2000). Applied to the cases of Russia and Ukraine, this idea can be manifested by the slogan “Russia is for ethnic Russians” and the notion that the Ukrainian national identity is defined primarily by ethnic roots or ancestry. Since this form of nationalism usually carries a negative connotation, most political leaders avoid making direct appeals to nationalism in their rhetoric. Thus, when identifying nationalist rhetoric, I adopt a broader approach to nationalism. In this article, nationalist rhetoric is conceived as references to a nation that help advance individual sense of attachment to the nation. These references may involve calls for national unity, appeals for national revival, identification of threats to a nation, and emphasis on shared ethnic and cultural background, as well as appeals to patriotism and national pride.

Several specifications to this study should be acknowledged from the beginning. First, the article uses the term “state-controlled media” with an understanding that not all media channels in Russia and Ukraine are state-controlled. In the case of Ukraine, the media are captured by the business elites with close ties to different groups in government (Ryabinska Reference Ryabinska2014b).Footnote 1 Second, while the article examines the nationalist rhetoric of presidents, I do not claim that the presidents of Russia and Ukraine are nationalists who are pursuing the goal of spreading a specific form of nationalist ideology. Instead, I argue that in times of crisis, it is useful for political elites to obtain legitimacy, and to mobilize and unite their domestic audiences by broadly appealing to different forms of nationalism. Thus, the article focuses on the ways that presidents use nationalist rhetoric to achieve those goals. Third, I view nationalism as a multilevel phenomenon, yet in this article I examine how nationalism is advanced on the state level through political rhetoric. While data limitations in the region make it difficult to trace whether this nationalist rhetoric is immediately embraced by the public, I use the existing survey data to highlight the trends in public opinion with regard to nationalism in its ethnic manifestation.

Since the start of the conflict between Ukraine and Russia in early 2014, nationalist rhetoric in the mass media space of both countries has been on the rise (Luhn Reference Luhn2014; Yudina Reference Yudina2014). However, the public response to this rhetoric seems to be different in the two countries. In Russia, nationalism in its ethnic manifestation is continuously growing among the public, along with the increasing levels of aggressive xenophobia and radicalism (Yudina and Alperovich Reference Yudina and Alperovich2015). Survey results (Table 1) suggest that nationalism was already a growing trend in Russia (shown by the Levada Reference Center2014b data) and that it may have been accelerated by the nationalist rhetoric in the media since the start of the conflict (Alexseev and Hale Reference Alexseev and Hale2015). Specifically, a growing number of people support the idea of Russia as a nation of ethnic Russians.

Table 1. Survey results for support of Russian nationalism.

1 Russian Public Opinion Research Center (Levada) surveys:

• Ocober 2011: A nationally representative sample of 1600 respondents interviewed face-to-face in Russia.

• October 2014: A nationally representative sample of 1600 respondents interviewed face-to-face in Russia.

2 The NEORUSS surveys:

• May 8–27, 2013: A nationally representative sample of 1,000 respondents interviewed face-to-face.

• November 5–18, 2014: A nationally representative sample of 1,200 respondents.

In Ukraine, however, survey results suggest that nationalism in its ethnic manifestation did not increase as a result of the conflict with Russia (Table 2). While the timeframe of survey data for 2006 and 2015 is broad, the additional survey data from 2012–2016 provide support for the argument that nationalist sentiments were not growing in Ukraine after the start of the conflict. Beyond ethnicity, other key elements of identity in Ukraine (native language and language spoken at home) have been declining in importance. Instead, post-2014 studies on national identity in Ukraine highlight the movement away from the focus on ethnicity, culture, and language and toward the identification with the Ukrainian state and the support of state institutions (civic nationalism and/or patriotism) (Onuch and Hale Reference Onuch and Hale2018; Razumkov Centre Reference Centre2016).

Table 2. Survey results for support of Ukrainian nationalism.

1 Razumkov Centre surveys:

• May 31–June 18, 2006: A nationally representative sample of 1600 respondents interviewed face-to-face in 212 cities and in 191 villages of Ukraine.

• December 11–23, 2015: A nationally representative sample (except Crimea, occupied Donetsk and Luhansk territories) of 10071 respondents interviewed face-to-face.

2 The NEORUSS surveys:

• May 8–27, 2013: A nationally representative sample of 1,000 respondents interviewed face-to-face.

• November 5–18, 2014: A nationally representative sample of 1,200 respondents.

One explanation for these contrasting trends in nationalist sentiments in Russia and Ukraine may lie in the difference of how political leaders used nationalist rhetoric in the mainstream media in the two states. Political elites often manipulate public opinion and promote nationalism through the use of media to reach their political goals (Moen-Larsen Reference Moen-Larsen2014; Ryabinska Reference Ryabinska2014; Szostek Reference Szostek2014a). Nationalism also becomes an effective tool of mobilization in times of conflict or a looming external threat (Van Evera Reference Van Evera1994). Considering that both Ukraine and Russia have largely state-controlled media (Reporters Without Borders 2015) and the two countries have been engaged in conflict, it is worth exploring how the Russian government is different from the Ukrainian government in advancing its nationalist rhetoric. This study addresses the following research questions: (1) How do leaders in Russia and Ukraine use nationalist rhetoric differently? and (2) How do leaders in Russia and Ukraine frame nationalism in the media to control public opinion?

Top-Down Nationalism in the Media

Scholars have long advanced the idea of nationalism as an instrument of political elites (Anderson Reference Anderson1991; Deutsch Reference Deutsch1966; Gellner Reference Gellner1983). By appealing to nationalism, political elites can address the interests of all citizens in a state, regardless of their background and their specific concerns (Barkey and von Hagen Reference Barkey and von Hagen1997; Suny Reference Suny1993). Nationalism is a particularly powerful tool for gaining legitimacy or mass mobilization in times of war (Cederman, Warren, and Sornette Reference Cederman, Warren and Sornette2011; Eatwell Reference Eatwell, Merkl and Weinberg2003; Snyder 2000). In the presence of an external threat from abroad (real or imagined), security concerns permeate the masses (Posen Reference Posen1993). Nationalist rhetoric can help unite distinct groups and mobilize them in the name of the nation against a real or potential enemy.

The literature on nationalism emphasizes the role of media in constructing, transforming, and intensifying national identification (Anderson Reference Anderson1991; Deutsch Reference Deutsch1966; Gellner Reference Gellner1983; Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm2012; Smith Reference Smith1991). The advancement of nationalism involves “the attachment of secondary symbols of nationality to primary items of information moving through channels of social communication …” (Deutsch Reference Deutsch1966, 146). Media sources might intentionally or unconsciously encourage identification with a nation even when reporting day-to-day news that is completely unrelated to ideology (Billig Reference Billig1995; Brookes Reference Brookes1999). Media consumers absorb either direct propaganda or subtle nationalist ideas on a regular basis, which helps promote attachments to the nation and, at times, even the sentiments of animosity toward other groups/nationalities. The presence of a military conflict tends to serve as an additional impetus for the media to advance nationalism and for the public to be more susceptible to nationalist messages (Bennett and Paletz Reference Bennett and Paletz1994; Mueller Reference Mueller1973). This idea is associated with the rally ’round the flag thesis, suggesting that during periods of military threat or conflict, the levels of mass patriotism and public approval of state leaders increase dramatically (Mueller Reference Mueller1973).

Contemporary media in Russia and Ukraine are not fully state-controlled, yet the governments either directly control or significantly influence national television news channels that have the widest coverage. In both countries, the political leadership is able to manipulate media coverage on a regular basis (Hutchings and Tolz Reference Hutchings and Tolz2012; Ryabinska Reference Ryabinska2014). Moreover, public opinion polls indicate that television remains the main source of news for the majority of the population in both countries: 83.5% of Ukraine’s population obtains news from TV channels, while 90% of Russia’s population relies on TV as a news source (FOM 2009; KIIS 2014; Levada Reference Center2014a). In both Russia and Ukraine, the public tends to have more trust in TV news, rather than the news from print media, radio, or the Internet (FOM 2009). Thus, television becomes the main tool of government control and presents the top-down strategy of manipulating public opinion (Lipman Reference Lipman2005). The high level of public trust in TV news is important because it signifies the regime’s ability to control public opinion for a long time into the future. Still, it is unclear what determines the success of political elites in promoting nationalism through state-controlled media.

Since the Kremlin has a firm control over the main television channels in Russia, the government is able to manipulate media coverage on a regular basis (Gehlbach Reference Gehlbach2010). Mainstream television channels serve as a link between the ruling elites and the public, delivering the value-laden messages to the viewers (Hutchings and Tolz Reference Hutchings and Tolz2012). In Russia, the trust in television media may be the result of the regime’s control over mass media for decades. The government has been promoting the idea that Western media and Internet media are not trustworthy and serve to undermine Russia’s stability. The media space in Ukraine is similarly captured by the state and the business elites loyal to political leadership (Ryabinska Reference Ryabinska2014). At the same time, local television channels with low ratings may remain independent (Etling et al. 2010).

A complete state control over mass media is typically associated with state propaganda. Throughout history, governments have used propaganda to promote aggressive nationalist ideology among the masses (Herb Reference Herb1997; Van Evera Reference Van Evera1994; Welch Reference Welch2013). Yet propaganda alone is not sufficient to build a regime’s legitimacy. Political elites, even in nondemocratic regimes, care about public opinion to some extent. Authoritarian leaders are able to stay in power because they pay attention to the needs and concerns of the masses (Bueno de Mesquita, Morrow, Siverson, and Smith Reference de Mesquita, Bruce, Siverson and Smith1999; Fearon Reference Fearon1994; Weeks Reference Weeks2008). In this regard, saliency theory may be instrumental in understanding how the regime can successfully promote nationalism and gain legitimacy through media by emphasizing relevant issues that concern the public.

Application of Saliency Theory

Scholars have traditionally relied on saliency theory to explain party support among voters in competitive democratic systems (Budge Reference Budge1994; Klingemann, Hofferbert, and Budge Reference Budge1994; Pelizzo Reference Pelizzo2003). When campaigning, parties emphasize a similar set of issues that are relevant to voters (e.g., welfare, education, health). According to Budge (Reference Budge2001, 82), “All party programmes endorse the same position, with only minor exceptions.” What makes a particular party stand out to voters is how the party resolves to solve the issues through a set of available measures. Since the limited resources would only allow focusing on a narrow set of relevant issues, parties differentiate themselves by assigning varying degrees of importance to different voter concerns. Parties, therefore, manipulate the salience of some issues over all others. Political elites are able to switch from focusing on one relevant issue to another, depending on what they think would get them more support from voters (Budge Reference Budge1994; Klingemann et al. Reference Klingemann, Hofferbert and Budge1994). The “cue-taking” theory of representation goes further in arguing that political elites (parties) take positions on particular issues that shape voter preferences and beliefs (Popkin Reference Popkin1991; Zaller Reference Zaller1992). At the same time, voters also send cues to political parties about their most pressing concerns (Franklin, Marsh, and Wlezien Reference Franklin, Marsh and Wlezien1994; Inglehart, Rabier, and Reif Reference Inglehart, Rabier, Reif, Reif and Inglehart1991).

The communication between political elites and the masses in terms of salient issues takes place in competitive democratic systems where political elites are accountable to voters and have to compete in free, fair, and frequent elections. However, this form of communication still takes place to some degree in nondemocratic regimes, where political elites need to create a sense of being tuned in to the concerns of the masses. For instance, in the context of nondemocratic regimes of Russia and Ukraine in 2013–2014, state elites cannot rely on propaganda alone to advance their rhetoric. There are alternative media sources and opposition forces in both states with Internet media remaining partly free from government control. Thus, political elites will be more successful in promoting nationalism if they are able to incorporate issue saliency into their nationalist rhetoric.

The success of top-down nationalist rhetoric is contingent on the saliency of issues that the elites discuss and promise to resolve. For instance, if the public is concerned with unemployment, state leaders may be successful in promoting nationalism if they emphasize the issue of unemployment as the barrier to prosperity and well-being of the nation while blaming foreign nationals for taking away jobs in a country. The majority of the population will not accept nationalist rhetoric advanced by the government unless political elites tie this nationalist rhetoric to the issues perceived as salient. Salient issues and concerns serve as a medium that allows political elites in these regimes to promote nationalist messages effectively, while also serving as cues that the masses send to the elites in terms of what issues the nation is facing. Political entrepreneurs may sense what issues are important to the masses and use these issues as the guidelines for their political party programs and political agendas. The issues, therefore, become even more salient in the eyes of the public, especially if the saliency is reinforced in the mass media.

Based on the information presented above, the following proposition is put forward in the research: A nondemocratic regime is likely to be successful at advancing nationalism if the regime is using nationalist rhetoric to emphasize salient issues that are relevant to the masses.

Methodology

In this research, I am applying the loose most similar systems design (MSSD) by treating Russia and Ukraine as most similar systems that vary on one major account: the trend in nationalism (Anckar Reference Anckar2008; Popova Reference Popova2012; Way Reference Way2005). In this type of MSSD, the two countries are not perfectly similar when it comes to several control variables (e.g., regime type, the level of media capture), yet they are similar along key features, such as the presence of an international conflict, the need for government legitimacy, and the deteriorating level of media freedom. Table 3 provides the details of this most similar systems design.

Table 3. Comparison of Russia and Ukraine: MSSD.

In terms of the political structure in 2013–2014, Freedom House (Reference Freedom2013) labeled both countries as nondemocratic regimes. Russia showed features of a consolidated authoritarian regime, while Ukraine was recognized as a hybrid regime. Despite the differences in regime types in the two countries, the events of the Euromaidan and the annexation of Crimea created a political environment where the leaders of both Russia and Ukraine were interested in gaining political legitimacy and could benefit from nationalism. While the political regime in Ukraine was less authoritarian than the regime in Russia, my focus in this research is on state-controlled and state-captured media in the context of nondemocratic states more broadly.Footnote 2 In addition, Freedom House in Reference Freedom2013 and 2014 reported a downward trend arrow when it comes to freedom ratings in both countries (Freedom House 2014a). Despite the fact that Ukraine is ranked higher on political freedom in 2013–2014, when it comes to freedom of the press scores for the same time period, Ukraine’s press is ranked as “not free,” similarly to the ranking of media freedom in Russia (Freedom House 2014b, 2014c). Under Yanukovych (2010–2014), Ukraine’s media environment remained largely pluralistic, yet media independence was sharply deteriorating (Freedom House 2014c; Ryabinska Reference Ryabinska2017). At this time, according to Szostek (Reference Szostek2014b, 5), “Television carried little content that might undermine Yanukovych.”

While Russia had a higher GDP per capita than the GDP per capita in Ukraine, the socio-economic conditions in the two countries were similar during the 2013–2014 period with both states experiencing an economic downturn. The Russian economy suffered from the Western economic sanctions and the drop in oil prices in 2014, while the Ukrainian economy similarly suffered from the loss of Crimea and the economic costs of waging the war in the east. Table 4 contains the comparison of the political and economic conditions in the two countries for 2013.

Table 4. Political/economic environment in Russia and Ukraine.

Sources: Freedom House, https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/FIW%202013%20Booklet.pdf; the World Bank, http://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/WDI-2013-ebook.pdf

In terms of the cultural background, both countries are multi-ethnic and multi-religious, with no single national identity. The two countries share the Slavic culture, the Orthodox religion, and the historical legacy of the Soviet Union. Most importantly, starting in March 2014, the two countries were essentially locked in a conflict. Yet, the survey results and the results of the 2014 elections in Ukraine indicate that nationalism kept rising in Russia, while in Ukraine it seemed to be in decline immediately after the Euromaidan protests. Part of the explanation for this difference might lie in the way political elites promoted nationalism in both countries.

In this research, I analyze nationalist rhetoric in the mainstream state-controlled news media in Russia and Ukraine. I examine the nationalist rhetoric of presidents in both countries. In Russia, it is the rhetoric of President Vladimir Putin, while in Ukraine there were three presidents during the time period under study: Victor Yanukovych, Alexandr Turchynov, and Petro Poroshenko.

Data Collection

The unit of analysis in this research is a reference to a nation (associated with different issue areas) within the presidential rhetoric in Russia and Ukraine. To operationalize nationalist rhetoric, I measured whether a leader mentions the keywords associated with nationalism. The analysis of nationalist rhetoric involved the search for the following keywords (and all their variations) intuitively associated with nationalism in the political leaders’ media speeches and announcements: “nation,” “nationality,” “national,” “nationalism,” “people,” “people’s,” “compatriots,” “Motherland,” ”Fatherland,” and “patriots.” The context of the rhetoric was examined to make sure the keywords were used as references to nationalism, as calls for national unity and national revival, as identification of threats to the nation, and as appeals to patriotism. The examples below demonstrate how the statements were coded when one of the keywords was identified.

It is in such crucial historical moments that the strength of the nation's spirit is maturing. And the Russians [russkiye] showed such maturity and such power … through their solidarity.

(Channel 1 TV news, March 18, 2014)This message was coded as a reference to the nation. Here, the Russian nation (natsiya) was referenced in the context of advancing national unity and highlighting the exceptionalism of the Russian people with an emphasis on the shared ethnic background.

Neither the Ukrainian people nor the world recognize the (Crimean) annexation, and this process has no legal consequences….

(Inter TV news, March 18, 2014)This statement was not coded as a reference to the nation since the word “people” (narod) was simply mentioned here without any context of advancing unity based on citizenship and/or shared background or enhancing the individual attachment to the nation.

I filtered out the keywords if they were part of the proper names of government institutions, parties, or companies and were irrelevant for further analysis. I have also excluded the keywords if they represented the names of professions, such as narodniy deputat (people’s deputy or a member of parliament) in Ukraine.

I acquired the data by searching for keywords in the direct speeches of leaders on the main television channels and official websites of presidents from September 1, 2013 to August 31, 2014. Selecting news reports clips that contained messages or announcements directly from a country’s president allowed me to obtain two datasets, one on the Russian media and another one on the Ukrainian media. Over the time period analyzed, there were more media announcements made by the Russian president than by the presidents of Ukraine. President Putin made 1,383 announcements on the main television news channel and his website, while the three Ukrainian leaders, Viktor Yanukovych, Oleksandr Turchynov, and Petro Poroshenko, made 1,055 announcements combined on the leading news channels (and the presidential website) in Ukraine. At times, the same message appeared on the news multiple times throughout the day. The repeated messages were duplicated in the datasets, as they indicate the emphasis of the leadership on specific rhetoric in the media.

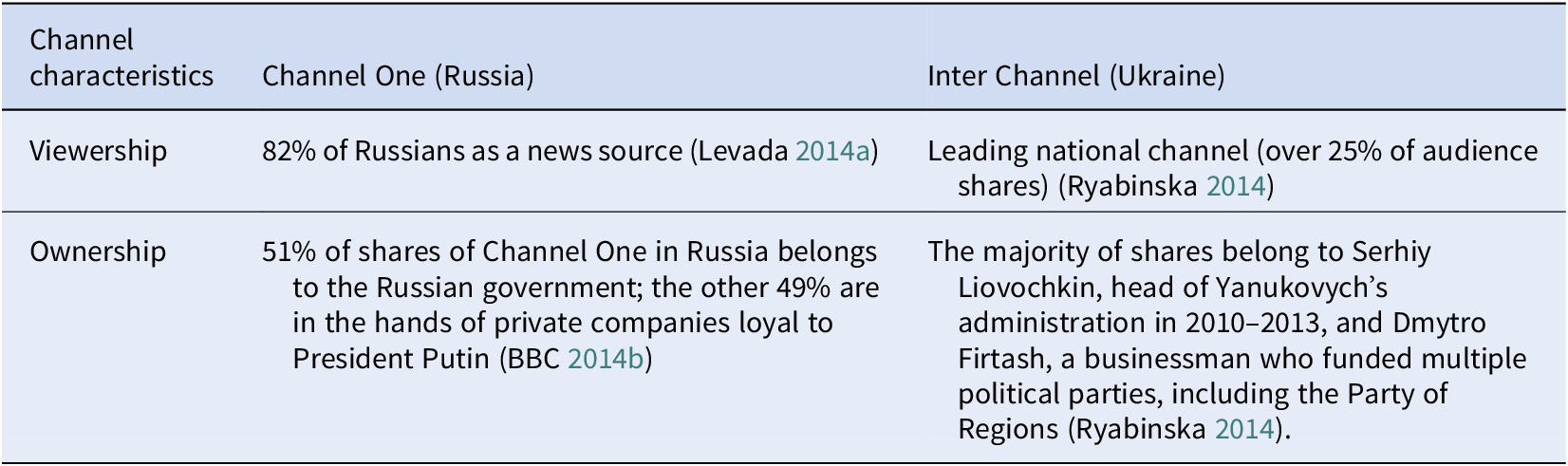

Content analysis was conducted on television media, since over 90 percent of Russians get news from television sources (Levada Reference Center2014a). In Ukraine, 83.5 percent of the population get news from television as well (KIIS 2014). I picked one leading television news channel with the widest national coverage in each country: Podrobnosti news on Inter Channel in Ukraine and News on Channel One in Russia. The details on the viewership and ownership of the two television sources are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Television sources of media content.

In addition to television coverage, I also analyzed content from official announcements and speeches of presidents from their official websites. In the cases of the ousted President Yanukovych and the interim President Turchynov in Ukraine, the official websites were unavailable, so I relied on the official announcements and speeches of leaders posted on the state news agency Ukrinform. Ukrinform is directly controlled by the Ministry of Information Policy. The press service of President Yanukovych moved its press releases to this website after the president’s own website was shut down by hackers in February 2014. Since December 2014, Ukrinform has been managed by Yuri Stets, the Minister of Information Policy and a relative of Ukraine’s President Poroshenko (Korol, Vinnychuk, and Kosenko Reference Korol, Vinnychuk and Kosenko2015).

The sampling timeframe was constructed to capture media coverage before and after the start of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine to account for the trends in nationalist rhetoric and the evolution of this rhetoric over time. News clips were selected from September 1, 2013 (about six months before the start of the conflict) to August 31, 2014 (about six months after the start of the conflict) from the presidential websites and from the leading national state-controlled television channels in Russia and Ukraine. News clips that did not contain a direct speech of presidents were not included in the dataset. The clip counts for each media source are presented in Table 6. A total of 2,438 clips containing a direct speech of presidents were downloaded directly from online archives of each media channel and official website. This design allowed me to identify the nature of salient issues emphasized in the nationalist rhetoric of presidents in both countries and whether the start of the conflict has changed the nature and the dynamic of this rhetoric.

Table 6. Media sources and clip counts.

The coding was done manually. Two researchers coded the clips using a codebook that evaluated the type of issue context that each reference to nationalism was couched in. Both coders followed a standard set of procedures to establish intercoder reliability (Krippendorf Reference Krippendorff2004). The coding team met the standard (over 80%) for intercoder reliability for all clips and keywords. Krippendorff’s Alpha of 0.836 was achieved, demonstrating a high level of consensus between coders.

Data Analysis

Once the relevant clips were collected, the textual data were grouped into three main categories (nodes) following Allen’s coding for news focus categories (Allen Reference Allen2005). All keywords associated with nationalist rhetoric were placed into political, economic, and cultural (social) nodes depending on the context in which they were mentioned to explore what groups of salient issues might be tied to nationalist ideas. A total of 1,769 references to the nation (keywords) and their context (node category) were analyzed for this study.

The political node included all keywords mentioned in clips focusing on diplomatic relations of states, their foreign policies (e.g., European integration, Customs Union, bilateral agreements), military activities (e.g., domestic and/or foreign threats to security and political stability), and domestic politics (e.g., protests, elections). The economic node included those keywords mentioned in the context of domestic economic matters (e.g., financial and monetary policies, production, banking) and economic ties with other states. Finally, the cultural node in the content analysis included all keywords mentioned in clips focusing on history, language, society, religion, arts/entertainment, and sports. Some keywords were placed in more than one category. For example, the keyword “nation” would be placed in both political and economic nodes if it was mentioned in the context of economic ties between Ukraine and Russia being a key priority for the Ukrainian nation. Here, the key term is used in the context of a foreign policy priority and as a goal of advancing Ukraine’s economic development.

Content Analysis of Nationalist Rhetoric in the Russian Media

The results of the content analysis of the Russian media are presented in Table 7. With the start of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, the Russian president did not significantly change the frequency of his nationalist rhetoric in the media. The number of references to the key terms associated with nationalism increased only by 0.5 percent in the period of March 1–August 31, 2014.

Table 7. Nationalist rhetoric and issue saliency in the Russian media, % to the total number of references to the nation.

Some references to nationalism were associated with more than one type of issue.

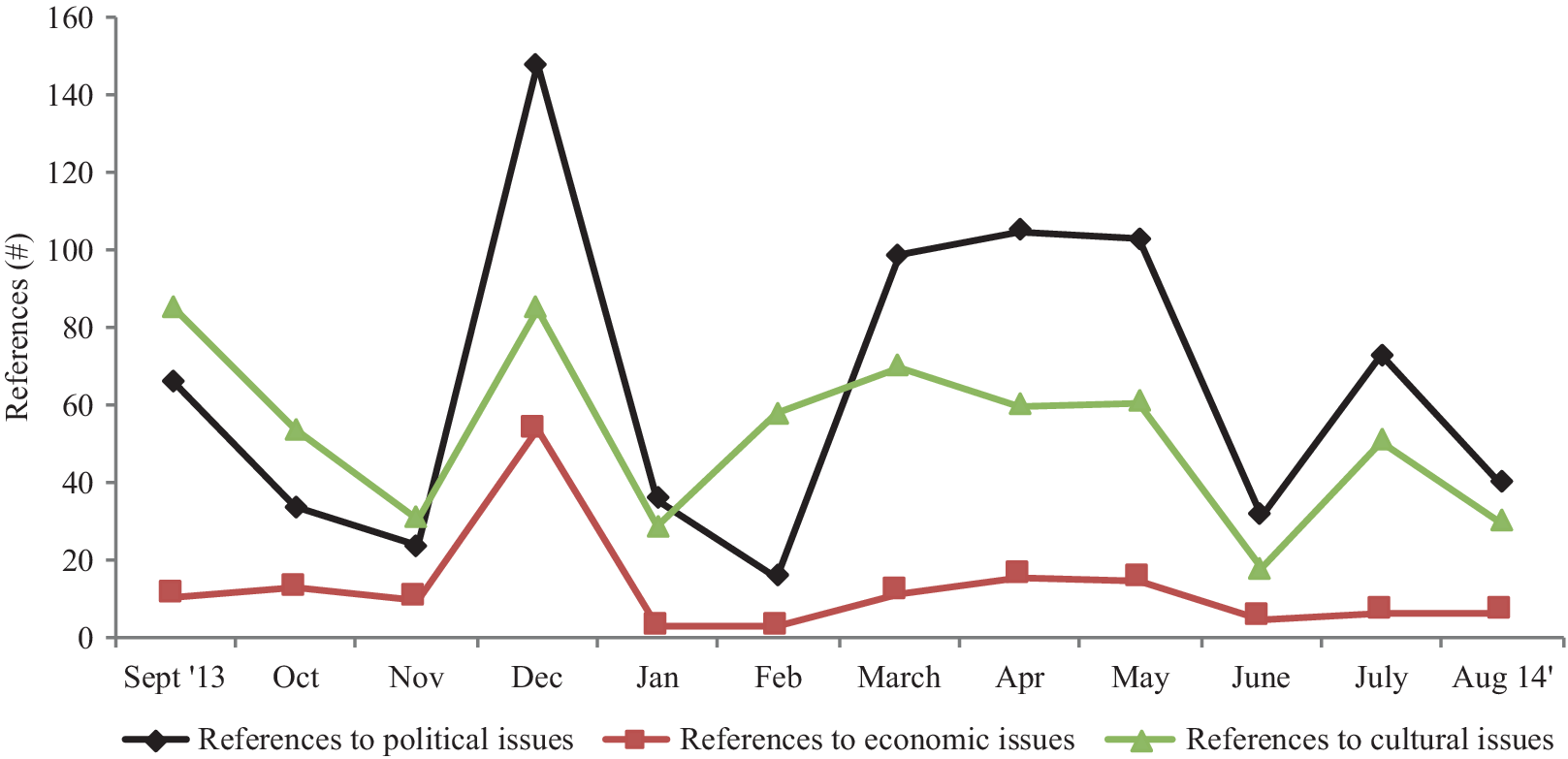

Throughout the study period, nationalist rhetoric was mostly tied to cultural and political issues in Russia. Before the conflict with Ukraine, President Putin equally emphasized cultural and political issues in his nationalist rhetoric. With the start of the conflict, Putin continued to emphasize these two issue contexts, with the cultural context becoming central in his nationalist rhetoric in February 2014. The discussion of economic issues has been virtually absent in the president’s nationalist rhetoric across the study period. The details on the volume and the dynamic of nationalist rhetoric in Russia and the nature of salient issues in which this rhetoric was couched are presented in Table 8 and Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Nationalist rhetoric and issue saliency in the Russian media, by type as a percentage of the total number of all keywords associated with nationalist rhetoric.

Figure 2. Nationalist rhetoric and issue saliency in the Russian media, by type as a percentage of the total number of all keywords associated with nationalist rhetoric.

Table 8. Nationalist rhetoric and issue saliency in the Russian media, by number of references (September 2013–August 2014).

References to the Nation Associated with Political Issues

Throughout the study period, while making references to the keywords associated with nationalist rhetoric, Russia’s president talked about political issues the most. During the conflict with Ukraine, the president has increased his references to political issues by 9.7 percent. In the first six months under analysis, the president has equally referenced domestic political issues and international political concerns. Domestically, Putin emphasized national security concerns, in particular, the instability in the Middle East that could affect Central Asia and the threat of extremist political groups in Russia. Putin also claimed that protection of civil society organizations, protection of the environment, and rebuilding the infrastructure in the eastern regions of the country are among the nation’s top priorities. Regarding international politics, the president discussed the future Customs Union and emphasized the threat of extremists taking over the government in countries like Ukraine. Putin also extensively talked about Russia’s image on the world stage and the need to strive for leadership in international affairs.

With the start of the hostilities between Ukraine and Russia in March 2014, there was a visible increase in nationalist rhetoric couched in the context of political issues. Most of the political issues discussed were associated with the political situation in Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea. President Putin used the keywords associated with nationalist rhetoric in the context of politics on 461 different accounts in the last six months under analysis. In particular, the emphasis in the media messages was on political instability and threats to the nation’s survival that extreme nationalism, Nazism, and coup d’états entail. Russia’s president continuously spoke about historical roots of nationalism in Ukraine, the propaganda of Nazism in the neighboring country and the direct involvement of the United States in the Ukrainian revolution. Putin’s discussion of the Crimean annexation also involved the use of nationalist rhetoric. Specifically, the president was making references to the legitimacy of the Russian intervention in Crimea, often referring to this event as the reunification. Nationalist rhetoric was also used in the context of discussing Russia’s position on the world stage and its ability to withstand diplomatic pressure from the West. The president noted that it was in Russia’s national interests to resist any outside influence without compromising the sovereignty of the Russian state.

The president used nationalist rhetoric in the context of domestic political issues as well. On multiple accounts, Putin talked about domestic security issues and inter-ethnic regional stability. In particular, the president made multiple references to the threat of extremism and inter-ethnic violence in Russia. Violent nationalist threats inside Russia were emphasized on different accounts. Through his rhetoric, Putin was publicly addressing xenophobic crimes that had occurred earlier in 2013. These references to extremist threats may have served as the foundation for future laws restricting the activities of NGOs and media freedom in the country (Boghani Reference Boghani2015).

References to the Nation Associated with Economic Issues

The Russian leader mentioned key terms associated with nationalism in the context of economic issues on 158 accounts. Most of the references to nationalism and economics were made prior to the start of the conflict in Ukraine. These messages primarily revolved around domestic economic issues. Before March 2014, Putin emphasized the need to restore a favorable business climate in Russia, and to resolve the issues of illegal labor immigration and unemployment. In discussing foreign economic relations, the president warned that countries around the world continuously used the tools of economic protectionism against Russia. Therefore, Russia should respond to these measures in a similar manner.

With the start of the conflict in Ukraine, the Russian leader reduced the focus on economic issues in his nationalist rhetoric. The president discussed the need to support the domestic economy and the plans to proceed with the organization of the Custom’s Union, which would help harmonize monetary policies among the member states and make currency markets more stable and predictable. Overall, economic issues were not tied to the president’s nationalist rhetoric in Russia.

References to the nation associated with cultural issues

The key terms associated with nationalist rhetoric in the context of cultural issues were mentioned on 727 accounts throughout the study period. Prior to the annexation of Crimea, the president made multiple references to the need to create a single national identity in Russia. Putin also emphasized the goal of interethnic peace as one of Russia’s main national interests. The questions of raising national education standards and teaching a unified version of history in schools were also discussed in Putin’s speeches. Finally, in the context of the 2014 Olympic games in Russia, the president emphasized the unifying role of sports for the Russian people and the international community as a whole.

With the start of the Ukraine–Russia conflict, Russia’s leader has maintained the focus on cultural issues in his nationalist rhetoric, although references to culture declined by 5.7 percent. Specifically, Putin made multiple references to the greatness and exceptionalism of Russia, Russian ethnicity, Russian values, and culture. Putin also often contrasted the values of the Russian people with Western values. Multiple references were made to patriotism as a national trait of Russians. At the same time, Putin discussed the importance of Russian culture, history, and traditions as the core components of the Russian nation. The historical and cultural value of the Crimean territory was also emphasized in the president’s rhetoric. The president continuously mentioned the need to protect the Russian speaking populations in Crimea and in eastern Ukraine from the ultranationalist government in Kiev. Finally, the Russian leader emphasized the importance of sports, education, and religion for the nation’s prosperity and peace.

Content Analysis of Nationalist Rhetoric in the Ukrainian Media

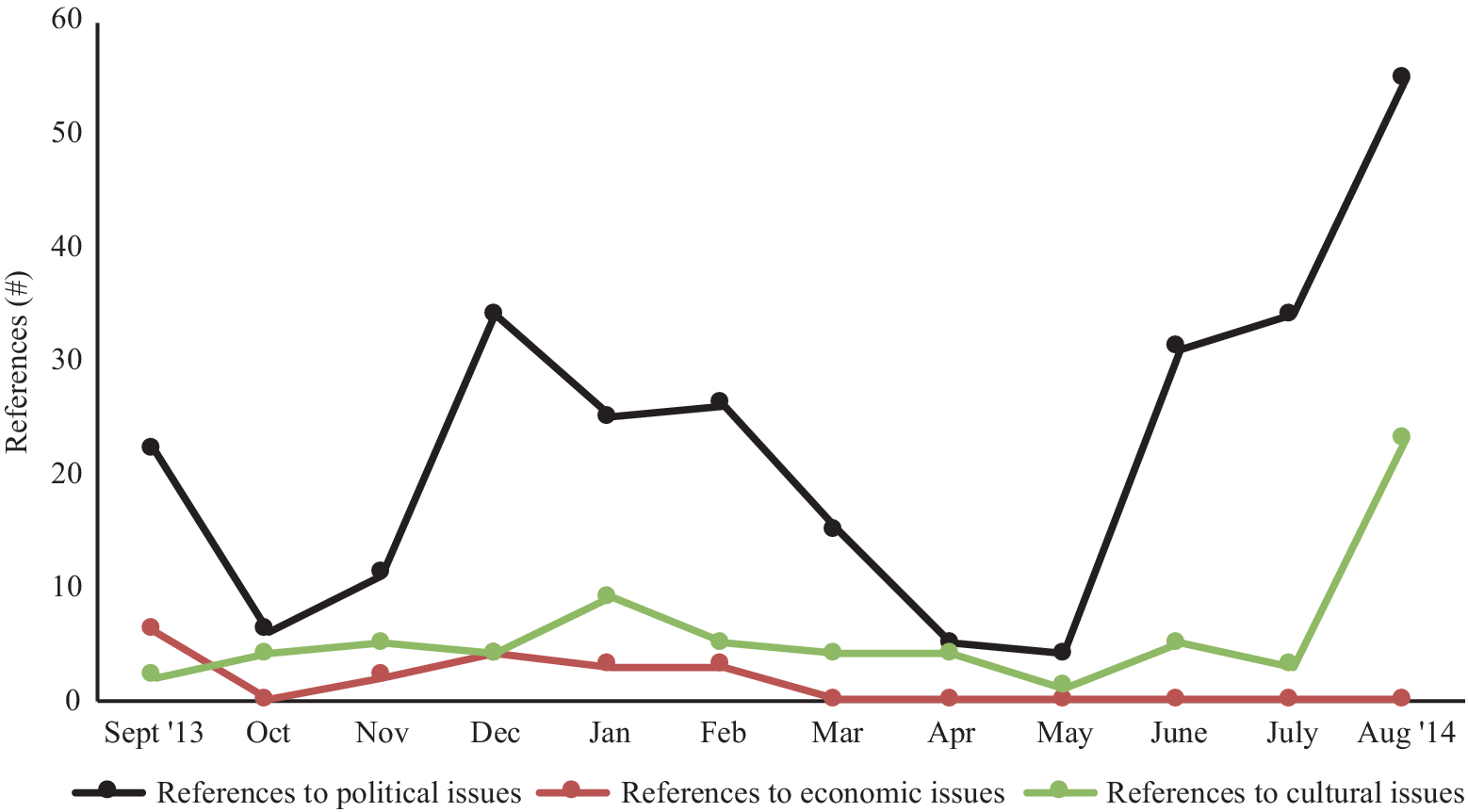

The results of content analysis of media in Ukraine are presented in Table 9. With the start of the conflict, political leaders in Ukraine also slightly increased the use of nationalist rhetoric (by 7.6 percent since March 2014).

Table 9. Nationalist rhetoric and issue saliency in the Ukrainian media, percentage to the total number of references to the nation.

In the course of the year, nationalist rhetoric was overwhelmingly tied to political issues in Ukraine. Economic issues were rarely used as a context for nationalist messages before the conflict with Russia but have been completely abandoned after the start of the conflict. The Ukrainian leaders did not extensively use cultural issues as a context for promoting nationalism either before or during the conflict. The details on the volume and the dynamic of nationalist rhetoric in Ukraine and the nature of salient issues in which this rhetoric was couched are presented in Table 10 and Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3. Nationalist rhetoric and issue saliency in the Ukrainian media, by type as a percentage of the total number of references to the nation.

Figure 4. Nationalist rhetoric and issue saliency in the Ukrainian media, by type as a percentage of the total number of references to the nation.

Table 10. Nationalist rhetoric and issue saliency in the Ukrainian media, by number of references (September 2013–August 2014).

References to the Nation Associated with Political Issues

While referencing the nation throughout the study period, political leaders in Ukraine talked about political issues the most. Specifically, nationalist rhetoric in the context of diplomacy came up as the presidents discussed integration with the European Union, the potential benefits of joining the Customs Union with Russia and other CIS countries, and the issues surrounding the gas deal with Russia. In particular, Ukraine’s President Yanukovych talked about the association agreement between Ukraine and the European Union as being against Ukraine’s national interest at the time. The president also associated mass Euromaidan protests in the winter of 2013–2014 with threats to the nation’s security. He claimed that appeals for revolution and calls for the change of government posed direct threats to domestic security and stability of Ukraine. Therefore, Ukraine’s leader continuously used nationalist rhetoric in order to gain legitimacy and obtain public support for his political decisions. Yanukovych also attempted to rely on nationalist rhetoric to deter the public from joining the Euromaidan by calling it a security threat. These appeals to the nation have not been successful. The public lost confidence in Yanukovych, who fled the country in February 2014.

With the overthrow of Yanukovych and the start of the conflict with Russia in March 2014, there was a 6 percent increase in nationalist rhetoric couched in political issues. National security concerns became primary in the announcements of Ukraine’s interim President Turchynov and the newly elected President Poroshenko. In particular, Poroshenko was elected on the platform of bringing peace to eastern Ukraine and returning Crimea to Ukrainians. Thus, in his speeches, the new president regularly addressed the nation with updates on the status of Ukraine’s military draft and conflict escalation in the occupied regions. Poroshenko delivered an extended speech on Ukraine’s Independence Day in August 2014 arguing that the conflict with Russia represented the birth of Ukraine’s national idea and marked the beginning of the nation’s true independence. Historically, the use of nationalist rhetoric in times of war and conflict has been one of the most useful tools in the hands of political elites. Therefore, it is not surprising that the issues of security at these times became primary elements within the nationalist rhetoric.

References to the Nation Associated with Economic Issues

The key terms associated with the nationalist rhetoric in the context of economic issues were mentioned least frequently. All of the references to nationalism and the economy were made by President Yanukovych prior to the start of the conflict with Russia. These messages equally targeted domestic economy and Ukraine’s foreign economic relations. Domestically, Yanukovych emphasized trade relations with Russia as key to Ukraine’s economic prosperity as a nation. At the same time, he cited the need for economic modernization as the goal of building a strong European Ukraine. To regain legitimacy and explain the change of Ukraine’s economic course away from the economic association with the EU, Yanukovych discussed the inability of Ukraine’s industries to be competitive in the European market. Following the start of the Euromaidan protests in November 2013, Yanukovych justified his decision not to sign an Association agreement with the European Union by arguing that Ukraine would turn into Europe’s main source of raw materials and primary goods.

With the start of the conflict with Russia, interim President Turchynov emphasized the “catastrophic” economic situation in Ukraine, citing problems with the monetary and banking systems as the main economic challenges in the country. Turchynov discussed economic problems without using nationalist rhetoric. In Ukraine and Russia, economic issues have been a relatively constant feature since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The masses tend to blame political leaders in Russia and Ukraine for the economic struggles in their countries. Therefore, uniting people on the basis of economic issues would not bring support and legitimacy to the political regimes in place. In times of conflict, economic issues become less important than political and security concerns.

References to the Nation Associated with Cultural Issues

Political leaders in Ukraine mentioned key terms associated with nationalism in the context of cultural issues on 69 accounts in the course of the study period. Ukraine’s presidents used nationalist rhetoric while discussing various issues related to the country’s cultural unity, the rights of minorities, and the need for national consolidation. With the start of the Russia–Ukraine conflict, the Ukrainian presidents mentioned the cultural context of language issues and ethnic minority rights in emphasizing Ukraine’s need for national consolidation. However, cultural issues were largely insignificant in the rhetoric of all three presidents compared to the discussion of political issues. This trend might be one of the reasons why the Ukrainian leaders were not as successful at advancing nationalism in Ukraine, despite the fact that the territorial integrity of Ukraine was violated by its neighbor state. The lack of focus on cultural issues in nationalist rhetoric was exacerbated by the new language law passed in February 2014, supporting the status of the Ukrainian language as the only state language in the country. Amid the outcry of the Russian-speaking Ukrainians, the government repealed this law two weeks later and granted special rights to languages other than Ukrainian. However, part of the Russian-speaking population in the east and the south of the country was alienated by the law, making it a key impediment to national consolidation in early 2014. The language law was also cited by President Putin as one of the official causes for Russia's intervention in the Crimea (Administration of the President of the Russian Federation 2014).

Conclusion

The findings in this article are important, as they advance the understanding of the legitimation strategies used by political elites in nondemocratic regimes. Elites may obtain or preserve power through nationalism because nationalist rhetoric helps them to present their political agendas as important for the whole nation. Thus, the elites do not have to make commitments to solve all the issues that the people are concerned with, including an increase in social welfare and wealth redistribution. By addressing the goals of protecting and advancing the interests of the nation, the elites seek to speak to the interests of all citizens in a state, regardless of their socio-economic status (Barkey and von Hagen Reference Barkey and von Hagen1997; Suny Reference Suny1993). This power of nationalist rhetoric is particularly influential in times of crisis or conflict.

The success of securing public support for the regime through nationalist rhetoric may be largely determined by the relevance of this rhetoric to the general public. The analysis of the nationalist rhetoric of the presidents in Russia and Ukraine is also instrumental in explaining how this rhetoric may be used by presidents in times of crises. Political leaders in Russia and Ukraine use state-controlled (or state-captured) media to advance nationalist rhetoric in different ways. The first major difference lies in the framing of the nationalist rhetoric. In Russia, President Putin couches nationalism in the context of political and cultural issues, while Ukraine’s leaders only use political context to advance nationalism. While cultural issues have been largely ignored by the Ukrainian leaders, these issues have been heavily emphasized in Russia by President Putin. As a result, in 2013–2014 the Ukrainian people might have been even more divided along the national identity question than they were in the early 1990s. There is a lack of government efforts toward national identity construction based on common culture, values, and history. In contrast, President Putin continuously emphasizes the cultural context of national unity in his rhetoric. The analysis shows that the Russian leader has been referencing cultural issues mostly in the months prior to the start of the conflict in Ukraine. Since the Russian intervention in Ukraine was largely justified by the need to protect ethnic Russians and Russian-speaking residents of Ukraine, the emphasis on both cultural and political issues helped address the most salient concerns for the Russian people. The reference to cultural issues in leaders’ nationalist rhetoric might be one of the reasons why nationalism has gained more prominence in Russia than among the Ukrainian people.

The second important distinction lies in the volume of nationalist rhetoric advanced by the leaders in the two countries. President Putin made appeals to nationalism four to five times more often than any of Ukraine’s leaders. Most importantly, the Russian president was much more active in his nationalist rhetoric at the time when nationalism was most salient to the domestic public: in the spring of 2014 when Russia invaded Crimea. During this critical time, Ukraine experienced a vacuum of leadership, with President Yanukovych fleeing the country and the interim President Turchynov dealing with the pressing political and security matters. February–April 2014 represents the time when Ukraine’s leader was the least active in his nationalist rhetoric. Figure A1 in the Appendix presents a comparison of the dynamic of nationalist rhetoric of presidents in Russia and Ukraine. The red box represents the most critical time for nationalist mobilization—the start of the Russian invasion into Crimea and the beginning of the conflict in the east of Ukraine. These differences in the patterns and the nature of nationalist rhetoric in Russia and Ukraine can help advance our understanding of the contrasting trends in nationalism in the two countries.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Robert L. Ostergard and Steven L. Wilson for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure

Author has nothing to disclose.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/nps.2019.130.