Despite the claim by Suetonius that ‘numerous statues and busts’ of the emperor Titus could be seen across Britain in the early second century,Footnote 1 few imperial statues in stone, whether of Titus or indeed of any other princeps, have been located archaeologically from within the province. Since a battered portrait in marble from York was first mooted as a likeness of Constantine I in the 1940s,Footnote 2 only a small amount of portraiture retrieved from Romano-British contexts has been re-examined with regard to identity; two busts from Lullingstone in Kent have been identified as the emperor Pertinax and his father Publius Helvius Successus,Footnote 3 while a number of damaged portraits, including one from Greater London, have recently been reassessed as likenesses of the fifth emperor Nero.Footnote 4

Two further portraits, both in a poor state of preservation, are re-examined here: a monumental marble head recovered prior to 1782 from the coastal village of Bosham in West Sussex, and a slightly larger than life-size head, also in marble, ploughed up from a field in Hawkshaw, Peeblesshire in, or just before, 1783. Although both have previously been described,Footnote 5 neither has been positively identified and so their meaning, significance and context within the province of Britannia remain poorly appreciated or understood.

THE BOSHAM HEAD

The ‘Bosham head’,Footnote 6 a more than twice life-size, heavily battered portrait in marble (fig. 1), has, since it was first recorded in the late eighteenth century at the eastern margins of Chichester Harbour in West Sussex, been accepted as a monumental image of a Roman emperor. Which particular emperor the head originally depicted has, however, been a matter of debate — Nero, Vespasian, Titus, Domitian and Trajan all having been put forward at some time.Footnote 7 Multiple differences of opinion with regard to the identity of the head are ultimately due to its extremely mutilated condition, the highly weathered nature of the piece being thought to be so extensive as to preclude any form of positive identification.Footnote 8

FIG. 1. (a) Right profile of the Bosham head, The Novium, Chichester, cat. A10150; (b) Portrait of the Bosham head, The Novium, Chichester, cat. A10150. (Photos: M. Russell; © The Novium)

In an attempt to resolve the identity of the portrait, as well as providing a better resolution of its date, context and significance, the Bosham head was subjected to a three-dimensional (3-D) laser scan. The first survey was undertaken in December 2007, while the artefact was on permanent display on the ground floor of the District Museum, Little London, Chichester. Unfortunately the position of the sculpture, at that time fixed to the floor against the western wall of the archaeology gallery, meant that neither the rear of the portrait, nor the areas of the chin and lower neck, were available for detailed examination.

In 2012, following the closure of the Chichester District Museum and the movement of archaeological material to new gallery space in the Novium, Tower Street, the head was temporarily placed in the stone store of the Discovery Centre, Fishbourne Roman Palace. Here, for the first time in over half a century, the object was fully accessible and therefore in an ideal state for additional 3-D recording. In early May 2013, the remaining areas of the portrait were examined and the results meshed together with the earlier survey in order to create a complete scan.

ORIGINS AND HISTORY

Information on the origins and context of the Bosham head is almost non-existent.Footnote 9 The earliest record of the artefact appears to have been in a watercolour sketch, now in the British Library,Footnote 10 by Samuel Hieronymus Grimm, a Swiss-born landscape artist, who drew the head, then in the vicarage garden of the Church of the Holy Trinity in the coastal village of Bosham, in 1782. Sadly, no further information is supplied with the sketch, which, if accurate,Footnote 11 appears to show the portrait in a considerably less weathered state, especially on the right side of the face, than it is today. The first, albeit rather limited, description was by Alexander Hay in Reference Hay1804,Footnote 12 who noted that a ‘marble relick of great antiquity’, referred to locally as ‘Bevois's head’ was visible at the vicarage. How the artefact came to be in the garden, who originally found it and precisely where are, unfortunately, issues that Hay did not (or could not) resolve.

The artefact was next briefly described and illustrated in situ within the grounds of ‘Boseham [sic] Parsonage House’ by the artist James Rouse in the early 1820s.Footnote 13 Rouse's published lithograph, depicting the south side of the parsonage with the church spire behind, shows the head sitting upright, facing south-east towards a pair of admiring spectators, apparently embedded within, or sitting atop, a small pile or cairn of stone, the full nature of which is unknown. In the accompanying text, Rouse asserts (without naming his source) that the head had been ‘dug up near Boseham church, where it formerly stood’,Footnote 14 although the date and circumstances of discovery are sadly not recorded. In 1831, Richard Dally repeats the claim for provenance, probably taken from Rouse, that the artefact ‘was many years ago dug up in the church yard’.Footnote 15

Bosham is the site of the earliest documented church in Sussex, as Bede records the presence of a ‘small monastery’ here in the early a.d. 680s;Footnote 16 nothing now survives above ground from this particular phase of Christian building, the present Church of the Holy Trinity being a palimpsest of mid-eleventh- to late nineteenth-century work. There is a strong local tradition that the present church was constructed over or from the remains of ‘a Roman basilica’,Footnote 17 but survey and analysis of the buildingFootnote 18 have demonstrated that there is little or no evidence for reused Roman material in either the internal or external fabric. Limited archaeological fieldwork in the vicinity of the church has, however, indicated some areas of potentially significant Roman activity, especially around Broadbridge to the north,Footnote 19 but the full extent and nature of this remain unclear.

By the early years of the twentieth century the stone head had been moved to an externally placed ‘niche in the wall’ of the Bishop's Palace gardens in ChichesterFootnote 20 where it formed ‘an ornament to a flower bed’.Footnote 21 Unfortunately, continual exposure to the elements in both Bosham vicarage garden and the episcopal gardens of Chichester appears to have resulted in considerable damage. When Richard Dally observed the artefact in the early 1830s, he observed that ‘the features are nearly destroyed’,Footnote 22 which in turn suggests that Grimm's original sketch of 1782 did not contain much in the way of artistic licence, especially when recording the nature and condition of the now heavily eroded eyes.

Removed from the garden on the instructions of Bishop George Bell in 1949, the head was given to the British Museum on indefinite loan.Footnote 23 At this time there were no formal display or storage facilities in Chichester, the earlier city museum having closed in the 1920s and the collection dispersed. In 1966, the Bosham head was finally returned to Chichester, going on public display within the Guildhall, a thirteenth-century monastic building in Priory Park.Footnote 24 From there, in 1979, it was transferred to the archaeological gallery of Chichester District Museum, a former corn-mill, where it remained until the closure of the building in 2011. At the time of writing it has been moved from the Discovery Centre of Fishbourne Roman Palace to a more permanent display location on the ground floor of the newly constructed Novium Museum in Tower Street, Chichester.

DESCRIPTION

The Bosham head is made of a coarse, crystalline marble, of possible Italian origin and stands just over two and a half times larger than life-size, measuring 0.42 m wide and 0.5 m high. It is presumed that it was originally part of a full-figure portrait, having been detached from the body at a break across the upper neck, just below the chin — an area that has now been largely worn smooth.

The head, as recorded in the 3-D scan (fig. 2), is very badly damaged and surface weathering is extensive. There is no real focus to the damage, battering being fairly consistent around the surface of the head, although the left-hand side is overall slightly better preserved than the right. This suggests that negative activity is more likely to have been the product of natural weathering rather than deliberate defacement, such as one might expect in the post-mortem memory sanctions conducted against certain unpopular emperors.Footnote 25 The upper right side of the head has been almost worn smooth, indicating a significant period of weathering, water erosion or frost shattering. Given the evidence already noted from the 1782 watercolour sketch by Grimm, Rouse's lithograph of 1824 and the description of the head provided by Dally in 1831, this pattern of erosion most probably occurred while the portrait was exposed to the elements in the vicarage and episcopal gardens of Bosham and Chichester.

FIG. 2. 3-D scans of Bosham head: (a) right profile; (b) front view; (c) left profile; (d) detail of fringe. (Images: H. Manley; © Bournemouth University)

Overall, the face of the Bosham head is heavy and broad, with full, clean-shaven cheeks, deeply set eyes, low forehead and protuberant brows. Damage to the face has unfortunately removed much of the nose, eyebrows and the right eye, while the chin has been completely lost, together with much of the lower right side. Dimples indicate the former position of the mouth and nostrils while the nasolabial fold is prominent, especially on the left side of the face. Both ears have been badly mutilated, the right having almost completely disappeared.

The coiffure is the most distinctive aspect of the portrait to survive, with deeply incised, curling locks of hair combed forwards from the crown, flicking out over, and partially touching, the ears and descending to the nape of the neck. The cap of hair is broadly Julio-Claudian in style, consistent with a first-, or perhaps even a very early second-century date.Footnote 26 The nature and form of the fringe, such a prominent marker of identity in official Roman portraiture, is unfortunately difficult to determine by eye, damage to the right side of the forehead having largely obliterated all trace of it. The 3-D scan, however, suggests the presence of three or more broad locks at the centre of the forehead, flanked (or framed) at either side by additional, inward-facing curls.

IDENTIFICATION

The origin of the name ‘Bevois's head’, first noted in relation to the Bosham marble by Hay in the early nineteenth century,Footnote 27 is unclear, although two potential candidates taken from local folklore present themselves: ‘Bevis of Hampton’, hero in a number of medieval romances, and St Justus of Beauvais, a Christian martyr executed near Auxerre in France during the late a.d. 270s.

Bevis of Hampton, who in some versions of the legend was a giant who could walk from Southampton to the Isle of Wight without wetting his head,Footnote 28 is linked with a number of prominent Early Neolithic long moundsFootnote 29 and other sites around Arundel in West Sussex. Rather tellingly perhaps, one story links him specifically with Bosham church, where his staff was said to reside.Footnote 30 Aside from Bevis, there could be confusion, or at least partial conflation, with stories surrounding the cult of St Justus of Beauvais, a cephalophoric (‘head-carrying’) saint, associated with the miracle of delivering post-decapitation orations. The head of St Justus became the focus of a major relic cult in post-Roman France,Footnote 31 veneration spreading to southern England following the acquisition of a fragment of cranium by Winchester Old Minster in the tenth century.Footnote 32

Hay, the first to try and make sense of the head, felt that the barbarous (weathered) nature of the sculpture, combined with its general ‘want of proportion’, suggested either a Germanic or Scandinavian origin. As such, he believed that the piece was likely to represent Thor ‘the Jupiter of the ancient pagan Saxons’ and was a religious image brought to British shores by the followers of Aelle, the semi-mythical late fifth-century warlord attested in the pages of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.Footnote 33 This interpretation was reiterated by Rouse, although with the proviso that ‘an eminent’, although sadly unnamed, ‘sculptor affirms, it was intended for that of the emperor Trajan’.Footnote 34 Ninety years later, the Reverend MacDermott, vicar of Bosham church, felt the head was probably a likeness of Trajan, although he added that his contemporaries felt it more likely to be ‘the Saxon god Woden, or of St Christopher, the patron saint of sailors’.Footnote 35 Heron-AllenFootnote 36 and WinboltFootnote 37 both concluded that the head was probably a replica of Vespasian, noting the popular, though wholly unsupported, local tradition that Bosham had been the landing-place and the headquarters of Legion II Augusta during the Claudian invasion of a.d. 43.Footnote 38

That the portrait is that of an emperor cannot be in doubt,Footnote 39 the size, quality and material used effectively excluding the possibility that this was the depiction of a governor, client king, petty administrator or local dignitary. Toynbee, in her comprehensive catalogue of Romano-British art, thought that the deep-set eyes of the Bosham head, combined with the ‘way in which the flat, lank locks of hair are dressed’, suggested that the subject was Trajan, rather than Vespasian, then the favoured interpretation.Footnote 40 Cunliffe and Fulford agreed that the head was an imperial portrait with ‘a certain resemblance to Trajan’, although they concluded that the badly weathered nature of the piece precluded any degree of certainty,Footnote 41 while, in the most recent consideration of the head, both Soffe and Henig felt that the portrait could best be compared to a posthumous portrait of Trajan recovered from Ostia.Footnote 42

As an imperial replica, the clean-shaven appearance of the Bosham head provides a plausible cut-off point for the date of manufacture. Before Hadrian came to power, the clean-shaven look was de rigeur among the Roman élite, with sideburns and bearded cheeks being generally rare, although not unknown, in the representation of Julio-Claudian and Flavian princes.Footnote 43 After a.d. 117, and until the beginning of the fourth century, emperors, imperial candidates, politicians and serving soldiers consistently appeared with varying degrees of well-groomed facial hair, shaved cheeks being decidedly unfashionable. That the Bosham head was created in the first or early second century and was not intended to represent a clean-shaven emperor of the fourth or fifth century, is evident in the realistic, non-stylised depiction of physiognomy and coiffure.

The proportions of the head itself further decrease the list of first- and early second-century imperial candidates, for the monumental size suggests that this was not a depiction of a reigning emperor, but a post-mortem image of a deified princeps. Deification immediately excludes Tiberius, Gaius, Galba, Otho and Vitellius from the discussion, none of whom were granted divine honours after death, as well as Nero and Domitian whose images were subjected to the most severe of memory sanctions, while apotheosis was only granted to Augustus, Claudius, Vespasian, Titus, Nerva and Trajan. The full, fleshy nature of the Bosham portrait further excludes the rather thin-faced Augustus, Claudius and Nerva, while the head's coiffure of well-defined comma-shaped locks, combed forward to the face, is quite unlike the bald pate of Vespasian and the tight corkscrew curls of Titus. Of the emperors reigning before a.d. 117, therefore, only the portraits of the thirteenth princeps, Trajan, compare profitably with the surviving features of the Bosham head.

The portraits of Trajan have been studied and catalogued on a number of occasionsFootnote 44 and, although there is comparatively little variation in the way this particular emperor was represented, appearing as an ‘ageless adult’ from the time of his formal adoption by Nerva in a.d. 97 to his death in a.d. 117,Footnote 45 at least six officially approved portrait types, falling into two broad groups, may be defined.Footnote 46 The differences between types are extremely subtle and relate primarily to the delicate arrangement of hair across the forehead.Footnote 47

The primary group of Trajanic portraits comprises two main model types showing the middle-aged, clean-shaven Trajan with a deeply scored nasolabial fold, the defining facial feature of his portraiture. The face is slightly on the fleshy side, with prominent, furrowed brows and a thin mouth. The coiffure in both types is combed forward from the crown, with thick, comma-shaped locks arranged in an orderly fashion across the forehead. This style appears to deliberately mimic the portraiture of the Julio-Claudians, especially that of Augustus, Tiberius, Claudius and the earlier portraits of Nero, as opposed to the later Flavian styles favoured by Vespasian (shaved), Titus (curls) and Domitian (elaborate, tiered creations inspired by the later hairstyles of Nero). The adoption of such a coiffure may have been a deliberate move on Trajan's part to disassociate himself from the Flavian regime, brought down through the infamy of Domitian, while harking back to the ‘golden age’ of earlier, more revered emperors.Footnote 48

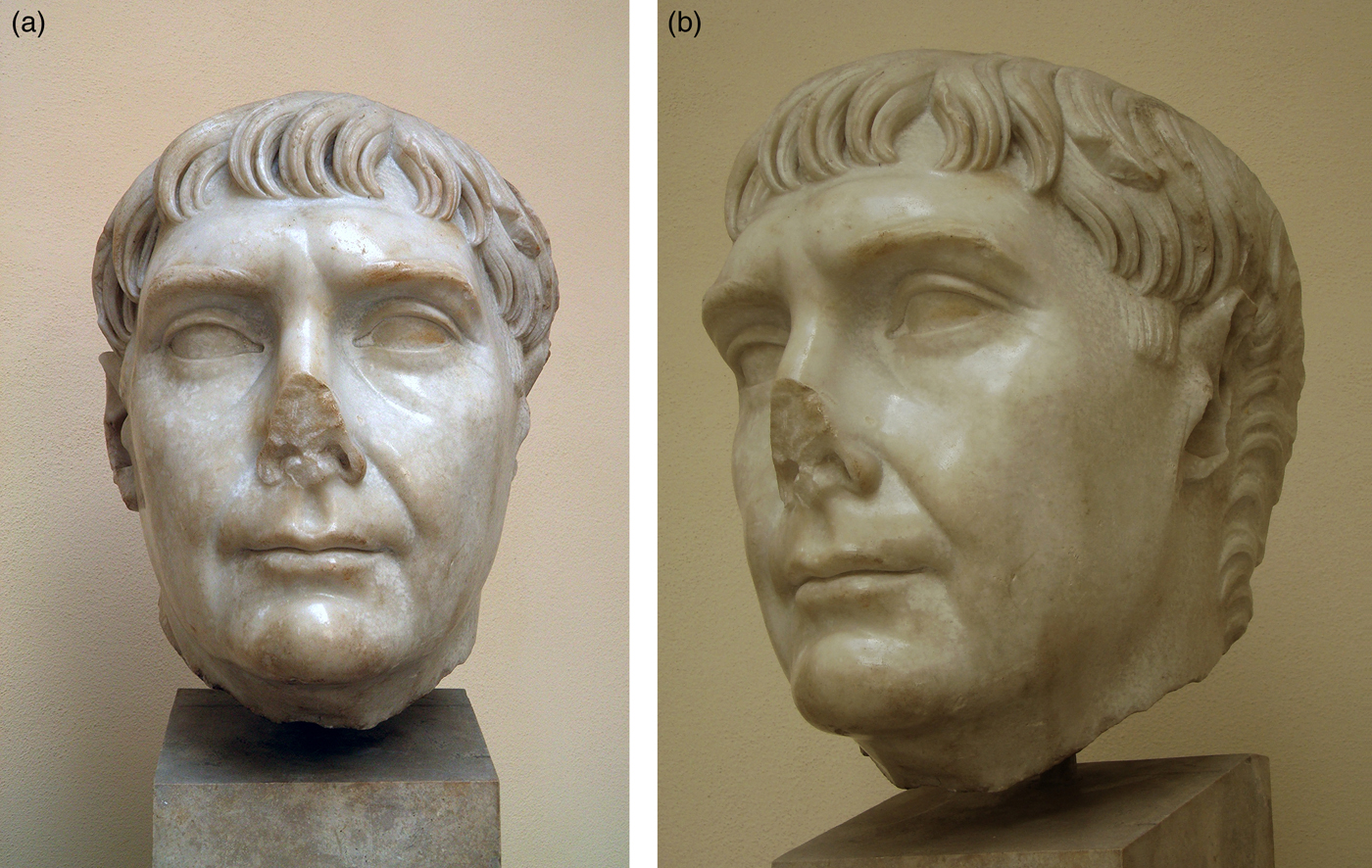

The key difference between the First Type, created shortly after Trajan's adoption, and the so-called Bürgerkronentypus, probably initiated for his accession in a.d. 98,Footnote 49 is that in the former (fig. 3) locks of hair curl away from a subtle, just off-centre parting in the fringe, while the Bürgerkronentypus has a minimal parting in the fringe just over the far left edge of the left eye, individual curls flowing left to right across the low forehead. It has been suggested that the majority of these early models were reworked from images of Domitian,Footnote 50 the treatment of Trajan's face varying considerably across the replica series while, in certain instances, traces of an underlying, more ‘Domitianic’ coiffure can be detected at the back of the head, just behind the ears.Footnote 51

FIG. 3. (a) Right profile of Trajan in his ‘First Type’ preserved in the Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. MA 3512; (b) Portrait of Trajan in his ‘First Type’ preserved in the Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. MA 3512. (Photos: M. Russell; © Musée du Louvre)

The second broad group of portraits created for Trajan, comprises four broadly similar models, the so-called Dezennalientypus (fig. 4), the Paris 1250-Mariemont type, the Opferbild type and the Wienerbüste type.Footnote 52 All possess a more fulsome, voluminous hairstyle than seen in the first group, with clearly differentiated locks of hair lying in complex patterns above the forehead.Footnote 53 Signs of facial ageing are reduced in these later portraits, Trajan's eyes appearing less baggy and brows far less furrowed. The forehead remains low and the nasolabial crease from nose to mouth is still distinct, but overall the face is less fleshy and more muscular in form.Footnote 54 Although it was previously thought that each variant type commemorated or celebrated a key moment in Trajan's career, such as his tenth jubilee or the receiving of the title Parthicus in a.d. 116 following conquests in the East,Footnote 55 there is some doubt as to the overall nature and chronological sequence.Footnote 56

FIG. 4. (a) Portrait of Trajan in his Dezennalientypus preserved in the Musei Vaticani, Rome, inv. 2269; (b) Left profile of Trajan in his Dezennalientypus preserved in the Musei Vaticani, Rome, inv. 2269. (Photos: R. Ulrich; © Musei Vaticani)

A last model type for Trajan, representing one of the finest portraits of the emperor to survive from antiquity, is the larger than life marble replica found close to the theatre in Ostia (fig. 5). This posthumous depiction, set up by his adopted successor Hadrian, shows the deified princeps with a distinctive cap of early Julio-Claudian hair, brushed from the crown and over the forehead in waves, three central locks, curling right to left, framed by additional curls at either side, the one over the left eye forming a small triangular parting.Footnote 57 In essence this ‘three-lock coiffure’ seems to have been chosen in order to mimic the ‘Primaporta-type’ arrangement of hair across the forehead of Augustus in replicas created after 27 b.c.Footnote 58 Hadrian, it would appear, was keen to utilise this distinctive hairdressing technique in the post-mortem images of his immediate predecessor in order to draw an explicit comparison between the first and thirteenth princeps.

FIG. 5. (a) Posthumous portrait of the deified Trajan set up by Hadrian at Ostia, preserved in the Museo Archeologico, inv. 17; (b) Three-quarters portrait of the deified Trajan preserved in the Museo Archeologico, Ostia, inv. 17. (Photos: (a) C. Raddato; (b) F. Tronchin; © Museo Archeologico, Ostia)

The physiognomy of the Bosham head as evident in the 3-D scan, especially with regard to the nasolabial fold and the position of the eyes and mouth, compares extremely well with the monumental head of Trajan from Ostia, as originally suggested by Soffe and Henig.Footnote 59 Certainly the layout and styling of individual, well-defined locks of hair, curling towards the face can be seen in the majority of later portraits of Trajan, while the ‘three-lock’ arrangement evident on the forehead of the Ostia portrait, may well also be evident in what survives above the eyes of the Bosham head.

CONTEXT

Toynbee thought that the colossal nature of the Bosham head ensured that the object was unlikely to have arrived in Sussex as a product of the Grand Tour,Footnote 60 its generally poor condition probably further arguing against more recent transportation back to Britain, which would have been both difficult and costly. The apparent location of the find, close to Bosham church, may furthermore argue against the idea of the head being a modern import, for Bosham is not within close proximity to a country seat or great artefact-collecting estate, although the harbour area could conceivably have represented a place where continental goods were first off-loaded in the seventeenth, eighteenth or nineteenth century.

The harbour location could, however, as Toynbee reasoned, potentially indicate the original point of arrival for the artefact on the Sussex coast as ship's ballast. This is a point also raised by Cunliffe and Fulford, who felt that the possibility the marble originated ‘in either an ancient or recent cargo’ could not be completely discounted.Footnote 61 To be fair, although use as a stabilising weight could well have been a contributory factor in the severe battering evident across the face of the Bosham head, it should be noted that no similar-sized ballast material has, to date, been found from either the village or the immediate surrounding area.

The relative closeness of the head to the palace of Fishbourne, only partially examined at the time Toynbee was compiling her Reference Toynbee1964magnum opus on Romano-British art, suggested that ‘the erection in the area of so large and impressive an imperial statue is by no means unthinkable’.Footnote 62 Assuming that the head was indeed only part of a full-figure portrait of Trajan, it is possible that it was erected by his successor Hadrian, during his visit to Britannia in the summer of a.d. 122 in which ‘he corrected many faults’,Footnote 63 initiated a major urban rebuilding programme and set about establishing a fixed northern limit to the province. It is possible that at this time Hadrian also oversaw the dismantling of the putative client kingdom of Togidubnus (or his successors), ensuring that the anomalous territory was officially and formally incorporated within the province of Britannia. Certainly the great palace at Fishbourne appears to have undergone significant redesign in the early years of the second century, the abandonment of the great aisled hall and formal gardens suggesting a possible end to the official functions of the building.Footnote 64

Armoured or cuirassed statues, depicting individuals wearing anatomically ‘muscular’ breastplates, were particularly popular in depictions of the imperial family and ‘members of the high elite with military distinctions, real or honorary’,Footnote 65 from the late first century b.c. to the late second century a.d. The most famous cuirassed statue is that of Augustus as imperator from the ‘Villa of Livia’ at Primaporta.Footnote 66 The statues of Trajan that survive from antiquity universally depict him as a confident leader in military guise, for example a Wienerbüste type portrait from the Schola of Trajan in Ostia,Footnote 67 in which the spear- or lance-holding imperator is depicted in a tunic, cuirass with leather straps at the lower edge and arms, and fur-trimmed boots with a military cloak, or paludamentum, draped across his left arm. It is likely, although by no means certain, that, given Trajan's military prowess and achievements on the battlefield, the Bosham statue, if it were indeed a full-length portrait of the deified emperor, would have been composed in a similar way.

It is worth noting that additional, albeit smaller, elements of Roman sculpture have been found in the area around Bosham — a life-size marble replica of a member of the Julio-Claudian house (possibly Germanicus),Footnote 68 a fragment of the upper torso from a life-size cuirassed figure (almost certainly an emperor), and a bronze thumb, also from a life-sized figure, being recorded to date.Footnote 69 Further archaeological evidence comes from a series of Roman structures discovered in the early nineteenth century at Broadbridge to the immediate north of Bosham.Footnote 70 These included a broadly rectangular masonry building, measuring c. 23 by 15 m, a ‘large excavation in the form of a basin’ apparently containing ‘tiers of seats’, at least one mosaic and a timber palisade (possibly representing part of an enclosure).Footnote 71 The vague nature of the excavation accountsFootnote 72 does not, unfortunately, aid interpretation. There can be little doubt that the main structure described was that of a temple or religious building, but more problematic is the so-called ‘large excavation’. Mitchell's brief description sounds like the remains of a theatre or amphitheatre, especially if the description of tiered seating can truly be believed. Unfortunately, Mitchell did not himself observe the structure and so, on the present evidence at least, it would perhaps be unwise to speculate further.

THE HAWKSHAW HEAD

A potential comparison for the Bosham head may be found in a replica dredged up by the plough near to Hawkshaw Castle in Peeblesshire in, or just before, 1783,Footnote 73 and subsequently placed within the collections of the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland.Footnote 74 As with the example from Bosham, the Hawkshaw marble is unlikely to represent a souvenir derived from the Grand Tour, its relatively remote findspot lying some significant distance from the nearest country house, while, as Curle has already noted ‘there is nothing in its execution to connect it with Italy’.Footnote 75 This is a very important portrait, therefore, given the almost total absence of marbles from Scotland.Footnote 76 Although the size of the piece, quality of workmanship and material used, all indicate that this was in all certainty a state-sponsored image, there has previously been no serious consensus as to the portrait's identity.

DESCRIPTION

The surviving part of the Hawkshaw head, measuring 0.27 m high and 0.24 m wide, is proportionally slightly larger than life and is carved from a white, crystalline marble (fig. 6). Much damage has been done to the face, the lower part of the chin and the nose both having been removed. Given the limited detail surrounding the nature and circumstances of the discovery,Footnote 77 it is unknown whether mutilation occurred at the time of statue's decapitation or as a consequence of later plough attrition.

FIG. 6. (a) Right profile of the Hawkshaw head preserved in the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, Edinburgh, inv. KG4; (b) Portrait of the Hawkshaw head preserved in the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, Edinburgh, inv. KG4; (c) Left profile of the Hawkshaw head preserved in the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, Edinburgh, inv. KG4. (Photos: F. Hunter; © National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland)

What survives of the portrait shows a clean-shaven, mature male, the serious nature of the slightly furrowed brow, when combined with the downward turn of the mouth and the prominent nasolabial fold, giving the face a distinct and ‘somewhat forbidding expression’.Footnote 78 The lips are thin and eyelids baggy, while the loose musculature of the cheeks overall creates a rather fleshy appearance. The coiffure, like the expression, tends towards the severe, with straight, well-defined locks of hair clinging to the skull in deeply combed parallel strands running diagonally towards the face from the crown.

The hair at the back of the head is less well defined than on the forehead, the general lack of finish indicating to some that the piece was not meant to be seen from behind, possibly with it originally standing within an alcove, niche or medallion.Footnote 79 Close examination of the artefact, however, suggests that the strands of hair at the back of the head, rather than being ‘sketchily worked’,Footnote 80 are, in fact, part of a wholly different coiffure, something that may further suggest that the portrait, as we see it today, has been refashioned from an earlier likeness. Such recutting is further apparent in profile where the extreme flatness and change in head shape over the forehead, may well document the recarving of facial features and the partial removal of an earlier coiffure.

IDENTIFICATION

The hairstyle places the replica squarely within the reign of Trajan, although Curle and Toynbee, who have both commented on the piece at length,Footnote 81 felt that it was probably not a likeness of that particular emperor. Toynbee observed that Trajan's demeanour in official portraiture was ‘normally more open and genial’, never displaying such a severe, down-turned mouth,Footnote 82 although, as both Curle and Henig have conceded, it is possible that the artist creating the Hawkshaw head was working from a poor or inexact model.Footnote 83 If the image was not intended to be that of an emperor, it could of course depict ‘some important personage’, such as a governor, general or other official.Footnote 84 The problem here, of course, is that, although the province of Britain was overseen by a number of governors and lesser officials during the first and early second centuries, there are no positively attested likenesses with which to compare the head. It is, furthermore, unknown whether such elaborate commemoration of a provincial official, however great their achievements, would (or could) have been permitted by central government, even if it formed part of a triumphal monument.

A number of more ‘serious’-looking images of Trajan, many displaying degrees of a severe and down-turned mouth, have been recorded since Toynbee was describing the Hawkshaw head in the 1960sFootnote 85 and, in the light of these, it is difficult to see who else the subject of the image could be, especially as the slightly larger-than-life depiction is a feature more characteristic of imperial rather than private portraiture.Footnote 86 In fact the physiognomic peculiarities of the Hawkshaw head, especially evident in the thin mouth, prominent nasolabial fold, baggy eyelids and ‘saggy’ cheeks, compare most favourably with the established portraiture of Trajan's earliest two models, the rather severe ‘First Type’ and ‘Bürgerkronentypus’Footnote 87 both of which appear to have largely been refashioned from portraits of the discredited Domitian.

The simple coiffure of long, flat strands of hair across the forehead can also be matched with Trajan's early sculptural replicas, created from the time of his formal adoption by Nerva in a.d. 97, to sometime shortly after his accession in a.d. 98. The fringe, however, comprising individual locks curving inwards to the centre without any clear parting, is not found within any of Trajan's official stone replicas, although it is possible that the styling betrays a provincial origin for the piece, comparisons having previously been drawn with certain Gallo-Roman portraits.Footnote 88

Another interpretation of the nature of coiffure depicted in the Hawkshaw portrait presents itself, for it has already been noted that the differential treatment of the image at the back of the head betrays the presence of an earlier likeness from which the portrait, in its present state, has been refashioned. Many of the earliest replicas created for both Trajan and his predecessor Nerva were reconfigured from Domitianic portraits as part of the memory sanctions that followed Domitian's assassination in a.d. 96.Footnote 89

Domitian's sculptured and coin portraits can be broadly divided into three main types,Footnote 90 although his profile, with hooked nose and long, thin mouth with receding lower lip, remains a distinctive feature throughout all replicas. In the earliest model, created from a.d. 72 in order to commemorate his official position as Caesar and second heir to the imperial throne after Titus, Domitian is portrayed with a full and curly coiffure, with individual curving locks combed across the forehead from right to left, occasionally reversing orientation above the right eye. Hair in the second type, first attested on coins minted from a.d. 75, is curlier over the forehead, receding slightly at the temples. The third model (fig. 7), created for the accession in a.d. 81 and used consistently thereafter, has long strands of hair, combed forward in discrete, and sometimes elaborate, waves from the crest towards the face, possibly in an attempt to obscure the more extreme signs of premature baldness.

FIG. 7. (a) Right profile of Domitian from his third portrait type preserved in the Musei Capitolini, Rome, inv. 1156; (b) Portrait of Domitian from his third type preserved in the Musei Capitolini, Rome, inv. 1156. (Photos: R. Ulrich; © Musei Capitolini)

A comparison of the coiffure of the Hawkshaw head and those hairstyles depicted within Domitian's third, accession type, suggests that the deeply combed strands of hair that run diagonally from the crown across the temples of the Hawkshaw portrait, which are not typical of Trajanic representation, may actually reflect an underlying hairstyle, having been broadly retained from an earlier likeness of Domitian, even though the forehead and face have been extensively recut. In such a scenario, the hair at the nape of the Hawkshaw neck, which again is very unlike that usually depicted in the later portraiture of Trajan, has probably been left in an unworked state, being largely undetectable to a general audience, much like other examples taken from Trajan's First Type and Bürgerkronentypus variants.Footnote 91

CONTEXT

If the military picture in Britain during Trajan's reign had been one of consolidation and retreat, the political situation in the early years of the second century may well have been spun in slightly more triumphant propaganda tones, the province perhaps receiving at least one new monument, of which the Hawkshaw head originally formed a small part, designed to celebrate Roman achievements at or close to what was then becoming the northern frontier.Footnote 92

Alternatively, and perhaps more intriguingly, given that the marble head appears to represent a portrait of the thirteenth princeps refashioned from a replica of the eleventh, the piece could originally have been part of a statue of Domitian or formed part of a monument commemorating his achievements, through the efforts of his governor Agricola, in the final conquest of Britain. In such a scenario, the original portrait of Domitian could have stood at the centre of a discrete statue group or as a single, free-standing figure in full military attire. Reworked as a portrait of a rather stern-faced Trajan, following the memory sanctions that followed Domitian's overthrow, the image presumably came to be deposited at Hawkshaw, in the lowlands of Scotland, as a direct result of its removal and subsequent transportation away from Roman territory as a trophy.Footnote 93 Such art-grab could plausibly have occurred during the troubles that pre-empted the emperor Hadrian's visit to the island in a.d. 122 when, we are told, ‘the Britons could not be kept under Roman control’.Footnote 94

If the head had originally formed part of an official statue group or monument, then the removal of key body parts, such as the head, during a revolt or incursion could be seen, not just as an act of simple desecration or vandalism, but as an important religious or ritualised act: the capture of an imperial image to be used as an offering to native gods. A parallel for such an action, albeit from the opposite end of the Empire, may be seen in the severed bronze head of Augustus taken from Egypt by an invading Ethiopian army around 25 b.c. and buried beneath the stairs of a temple dedicated to Victory in Meroë, Sudan;Footnote 95 and also, rather closer to home, in the decapitated head of a young Nero, apparently taken in the Boudiccan revolt of a.d. 60–1, found within the river Alde in Suffolk.Footnote 96

CONCLUSIONS: FINDING TRAJAN

Two ‘new’ portraits of the emperor Trajan may now be added to the small list of imperial stone portraits recovered from the British Isles. Although Trajan appears to have had very little real interest in Britain, the conquest of which had been the pet project of both the earlier Julio-Claudian and Flavian dynasties, as a prominent and much-celebrated emperor of the late first and early second century we should not perhaps be surprised to find images of him set in key locales across the province. Of the two artefacts described, the Hawkshaw head is intriguing not only as it suggests the presence of a triumphal statue or monument, possibly established to commemorate the total conquest of Britain under the Flavians, in what is now the Scottish lowlands or northern English uplands, but also because it appears to confirm that realignment of identity, in the memory sanctions that followed Domitian's assassination in a.d. 96, spread to all parts of the Roman Empire, even to those images on the distant north-western frontier.

The marble portrait of Trajan identified from Bosham may also have originally graced a triumphal monument, although, given its size, it is more likely perhaps to have formed part of a freestanding image of the emperor, succumbing more to the ravages of time than to the force applied by a violent mob. A statue of the deified optimus princeps as imperator placed within Chichester Harbour at, or very close to, where the Church of the Holy Trinity in Bosham now stands, would perhaps have been considered rather appropriate, given not only a similar monumental post-mortem image of Trajan established by Hadrian at the port of Ostia, but also the position of the Colossus of Rhodes which traditionally guarded the approach to another important harbour in the Mediterranean. The Bosham statue, as well as being one of the first things to greet those disembarking on the south coast of Britain, could also have served to dramatically mark and forever commemorate the formal transition, under Trajan's successor Hadrian, of territory surrounding nearby Chichester and Fishbourne from client kingdom, under the rule of the native aristocracy, to a more normal part of the province of Britannia in the early years of the second century.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are immensely grateful to the staff and volunteers of the Novium, Fishbourne Palace Museum and the former Chichester District Museum, especially Tracey Clark, Catherine Coleman, Ian Friel, Anooshka Rawden, Amy Roberts, Rob Symonds and Kerill Winters, for their considerable help in facilitating the two 3-D laser scans. Thank you also to James Kenny, Archaeology Officer at Chichester District Council, Richard Evans and Dick Pratt for valuable discussion and information concerning the context and nature of the Bosham head, Fraser Hunter, Principal Curator of Iron Age and Roman collections at the National Museum of Scotland, for information surrounding the Hawkshaw head, Thorsten Opper, Curator of Greek and Roman sculpture at the British Museum, for help and advice early on in the scanning project and Roger Ulrich, Professor of Classics at Dartmouth College, Francesca Tronchin, Assistant Professor of Art History at Rhodes College and Carole Raddato for permission to reproduce images from their invaluable photographic archives.