Introduction

One of the promising new avenues of research within social history has been the exploration of the ‘scientisation of the social’ (‘Verwissenschaftlichung des Sozialen’), a term coined in 1996 by the German historian Lutz Raphael.Footnote 1 It refers to the ‘intended and unintended consequences [of] the continuing presence of experts from the human sciences, their arguments, and the results of their research. . .in administrative bodies and in industrial firms, in parties and parliaments’.Footnote 2 According to Raphael, the scientisation of the social has unfolded in the Western world since the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 3 He calls on historians to scrutinise, rather than take for granted or appropriate, the concepts, theories and practices used by social scientists over the past century and a half in their efforts to explain contemporary society.Footnote 4 After all, scientific concepts have been at the heart of self-descriptions of various groups in society and have played a key role in framing social problems and the policies that were promoted to solve them.Footnote 5

Up to now, the notion of ‘scientisation’ has been picked up mainly by social historians and political historians interested in governance and policy-making. It has largely been ignored by those working on party politics, save a few important exceptions such as the work by Anja Kruke and Laura Beers on the use of opinion research by German and British political parties.Footnote 6 Kruke has shown that from the 1960s onwards opinion research led German political parties to gradually move away from social-determinist interpretations of voting behaviour and adopt new categorisations of the electorate based on voters’ sentiments and opinions on particular issues. Beers, in turn, has argued that up until at least the 1960s British parties were reluctant to use opinion research because they believed it threatened the very foundation of representative democracy: the independence of MPs.Footnote 7

This article aims to further explore the ‘scientisation of the political’, as one might call it, through an analysis of the use and reception of social-scientific expertise by Dutch political parties. We will chiefly focus on research on voting behaviour, which established itself as a social-scientific endeavour in the early twentieth century against the background of the gradual extension of suffrage all across Western Europe. Slowly, Dutch political parties developed an interest in such research. Drawing comparisons with Britain and Germany, the article explores this process through the 1970s, when the scientisation of the political entered a new phase. We aim to show that the scientisation of the political was a diffuse process in which the labels ‘scientific’ and ‘political’ became jumbled up. In fact, scientisation went hand in hand with a politicisation of the social sciences. Parties began to use social-scientific knowledge to design effective electoral strategies while people trained in the social sciences established names for themselves as ‘experts’ within party committees or partisan political think tanks.Footnote 8

Moreover, we argue that an analysis of the interaction between social scientists and political parties improves our understanding of politicians’ conceptions of political representation and the shifts in those conceptions over time. Social science based knowledge exerted a profound effect on how parties approached political identity formation and on their perceptions of the electorate. It provided them with new theories about the relationships between class, religion and political identity and with new insights into both popular perceptions of specific political platforms and political leaders and the effects of these perceptions on electoral behaviour. We particularly engage with research on political representation that has been inspired by a normative approach grounded in political philosophy or by social-scientific theories. In his still unsurpassed study The Principles of Representative Government,Footnote 9 the French political scientist Bernard Manin, while showing a remarkable eye for historical change, sticks to a social-scientific narrative in his description of the nature of political representation in the first half of the twentieth century, characterising it as merely a ‘reflection of the social structure’.Footnote 10 Such social determinism is still present in Dutch readings of the nature of political representation. Between roughly the late nineteenth century and the 1960s, political parties are said to have mirrored existing cleavages in society: political identities supposedly reflected the socio-religious structures in which voters were embedded.Footnote 11 The cultural and linguistic turns have done much to contest such readings of representation.Footnote 12 Rather than treating parties as the ‘passive beneficiaries of structural divisions within society’, they should be approached as ‘dynamic organisations actively involved in the definition of political interests and the construction of political alliances’.Footnote 13

Our approach is also inspired by Raphael's framework for exploring the scientisation of the social. He has distinguished five different ‘roads leading from academic scholarship into society’.Footnote 14 The first road concerns the analysis of key concepts and discourses:Footnote 15 social-scientific concepts introduce new categorisations and (self-)descriptions of voters, as well as new conceptualisations of political identities, into the political sphere. The second road leads to an analysis of the role of experts – members of partisan think tanks or social scientists who join party committees and discuss electoral strategies – in the transfer of social-scientific knowledge, both inside and outside academia. The third road addresses political clients and their reception and appropriation of social-scientific knowledge. Here one sees scientisation negotiated by politicians who have not always been eager to adopt social-scientific insights and have been sceptical towards new theories that clashed with their reigning assumptions and opinions. The fourth road covers the techniques used to acquire knowledge on – in this case – voting behaviour: most importantly, surveys and opinion polls. Finally, the fifth road accounts for the role of institutions such as the political parties’ think tanks, which played an important role in producing and processing social-scientific expertise on electoral behaviour.

The main sources used in the analysis that follows are the reports of political scientists commissioned by party boards or partisan political think tanks; party magazines, which acted as a medium for the transfer of knowledge from the social sciences to political parties; scholarly publications and, finally, the minutes of campaign and other party committees, which reveal much about the reception and appropriation of social-scientific understandings of voting behaviour. The focus will be on the Social Democratic Party and the Catholic Party, the two most powerful forces in the Dutch parliament throughout the period under investigation.

The article opens with an analysis of the birth of electoral research in the early twentieth century and the impact of crowd psychology on perceptions of the electorate among Dutch political parties. We then discuss the introduction and reception of opinion research in the post-war years and analyse the social-determinist paradigm in academic research on voting behaviour and its reception by Dutch political parties. In the section that follows we consider the emergence of new, non-social-determinist understandings of electoral behaviour in electoral research, which took individual voter preferences seriously and made categorisations on the basis of such preferences. Our discussion tracks their – not so straightforward – reception by the Social Democrats and the Catholic Party and explores the rise of a new, younger generation of political experts, whose careers in party politics were intimately linked to their social-scientific expertise.

Number Crunching and Crowd Analysis

Since the mid-nineteenth-century introduction of parliamentary democracy and direct elections in the Netherlands, Dutch political parties and individual candidates have been looking for ways to accumulate data on the electorate. The district voting system, the limited franchise and the availability of a list of electors enabled candidate MPs to locate and directly approach voters in their districts.Footnote 16 Scientific electoral research took shape slowly from the late nineteenth century onwards. The district voting system, common across Europe, was conducive to the dominance of electoral geography.Footnote 17 In the Netherlands electoral research was spurred on by gradual suffrage extensions and concerns about the evolving electorate's voting behaviour. Interest in electoral research increased particularly after 1918, when general suffrage was introduced, although it was far from being an established field among Dutch academics in the interwar years.Footnote 18

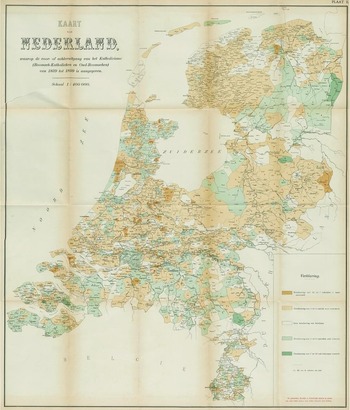

The first major study of Dutch electoral geography was published in 1909 by J. C. Ramaer, chair of the Royal Dutch Geographical Society (see Figure 1). Ramaer's approach and lines of argument, as with most of his European colleagues, tapped into existing representations of voting behaviour and strengthened them. In Ramaer's case, he treated religion as a key and self-evident marker for the formation of political identities. By mapping the distribution of religious groups across the country and linking these data to election results at the district level, he showed that Dutch Catholics were underrepresented in parliament. Ramaer's study had clear political implications: it helped to persuade the Catholic Party to support the growing call to abolish district voting in favour of a new electoral system of nationwide proportional representation, which eventually was instituted in 1917.Footnote 19 The Catholic Party indeed benefited from the new system: it won the support of a majority of Dutch Catholics, which made the party the most powerful force in Dutch Parliament in the interwar years.Footnote 20

Figure 1. Map of the Netherlands indicating for each municipality the rise and decline of Catholicism between 1839 and 1899

The new electoral system produced a new kind of data. Parties could now easily establish how many votes they had won across the country; such data had been very hard to compile under the district system. However, geographic electoral research remained dominant and argumentation remained superficial: when the Social Democrats lost and the communists won, voters had apparently switched sides. The relevance of such research to political parties remained limited. One study rather predictably showed that the Catholic Party had its strongholds in districts where Catholic housing corporations owned large housing blocks.Footnote 21 J. P. Kruijt, a leading Dutch social geographer and sociologist who sympathised with the Social Democrats, claimed that his research, which involved electoral statistics and showed a gradual secularisation of the Dutch population, had ‘practical meaning’ for political parties. Parties, however, did not pay much attention.Footnote 22 The Social Democrats, for their part, were far more concerned with ideological disputes concerning various interpretations of socialism.Footnote 23 This is not to say that the Social Democratic Workers’ Party (Sociaal-Democratische Arbeiderspartij, SDAP) did not open itself up to adopting a scientific approach to political issues. The SDAP had a strong intellectual tradition and prided itself on its ‘scientific’ approach to social issues, maintaining a non-dogmatic interpretation of Marxism. Sociologists such as Kruijt had a particularly strong presence within the party and used the monthly De Socialistische Gids as a platform for their ideas, which interpreted socialism as an ‘applied science’. Quantitative-based science was, however, still largely neglected.Footnote 24

In the 1930s the social democrats became more engaged with another, emerging field of research that delved into the electorate's behaviour by exploring its psychological make-up. Like many others, Dutch politicians had been intrigued by the controversial study made by the French social psychologist Gustave Le Bon, The Crowd: A study of the Popular Mind (Psychologie des foules, 1895), which was read as a manual for politicians on how to deal with the masses.Footnote 25 Le Bon argued that crowd behaviour was guided by emotions rather than reason.Footnote 26 Effectively tapping into these emotions could thus bring political gains, but Dutch political parties were not keen to do so. Voters were perceived not as an amorphous mass electorate but as members of different, well-demarcated communities – Catholics, orthodox Protestants, the working class and so on. Political parties preferred to present voting as a serious, rational act through which voters expressed loyalty to the party that represented ‘their’ community.Footnote 27

The situation changed somewhat in the 1930s, when the Social Democrats in particular became worried about the role of mass psychology in the rise of National Socialism in neighbouring Germany. The Belgian social psychologist and Labour Party leader Hendrik de Man encouraged his fellow Social Democrats across Europe to adopt the techniques of their enemy.Footnote 28 He had a profound belief in the political malleability of voters; as long as a political party found the right ‘tone’ and used proven methods and techniques of crowd psychology, political opinions could be steered in the right direction.Footnote 29 As far as the Dutch Social Democrats were concerned, his views were translated into the application of ideas and techniques from the world of advertising – a business that was heavily influenced by social psychology.Footnote 30 The Social Democrats diversified their propaganda to tap into the specific make-up of various sections of the Dutch electorate and to market their party as a popular brand.Footnote 31 The SDAP thus pursued new directions in the second half of the 1930s, moving away from a focus on class struggle and shifting towards a new, more inclusive understanding of class that was meant to bring in middle-class voters.Footnote 32

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic a new understanding of the electorate had taken shape as a new group of experts began to employ innovative scientific methods. In the 1930s public opinion research in the United States rose to the fore, gauging public opinion via surveys and polls. Its American ascendency was soon duplicated in Britain and, in the immediate post-war years, other European countries. The thrust of public opinion research was quite different from mass psychology's insistence on malleability. Instead, it was grounded in the ideas of theorists such as James Bryce, who held that the opinions of the public should be taken seriously.Footnote 33 Polling evangelists like George Gallup promoted such research as a victory for democracy: in place of the pessimistic view of the public as an irrational mass entity, there emerged the category of the opinionated electorate.Footnote 34 The introduction of opinion research in the Netherlands in the immediate post-war years signalled a new era in the scientisation of the political.

The Containment of Opinion Research

After the Second World War the scientisation of campaigning took off. New techniques such as surveys and opinion polls profoundly changed the nature of electoral research: no longer exclusively concerned with election results, attention was now given to people's preferences as well as their opinions on a range of political issues. The transfer of knowledge from the social sciences to political parties was facilitated by the emergence of university departments and commercial agencies in the field of opinion polling, electoral behaviour and marketing research, and by new institutions like partisan political think tanks, which were established by all the major Dutch political parties in the early post-war years. The number of clients – that is, those in the world of party politics interested in applying social-science research – expanded. Although the Social Democrats remained the front-runners in professionalising their campaigning through scientisation, other parties, particularly the Catholic Party (Katholieke Volkspartij, KVP), followed suit.

In the late 1930s Dutch newspapers had begun to report on the activities of the American polling pioneer George Gallup.Footnote 35 The rapid expansion of polling in the United States was linked to the purported unpredictability and emotional volatility of American voters. Dutch voters, by contrast, supposedly cast their votes based on political principles; opinion research would therefore be superfluous in the Netherlands, or so the newspapers argued.Footnote 36 After the war, however, opinion polling was successfully introduced in the country as well as elsewhere across the continent. Gallup travelled across Europe to discuss his methods and licensed several institutes of public opinion. Whereas in several countries Gallup practically cornered the market for opinion research, in the Netherlands – much as in Germany – several institutes started to conduct polls, led by the Dutch Foundation for Statistics (Nederlandse Stichting voor Statistiek, NSS) and the Gallup-licensed Dutch Institute for Public Opinion Research (Nederlands Instituut voor Publieke Opinieonderzoek, NIPO), founded in 1945. Following the American example, newspapers and magazines were keen to make headlines with survey results and soon commissioned opinion research, mostly on non-political topics.Footnote 37

Strikingly, social scientists in the Netherlands were quick to claim opinion research as a new scientific method – German academia, by contrast, did not take opinion polls seriously before the 1970s.Footnote 38 Several prominent scientists in the fields of law, sociology and psychology were among the founders of the Dutch Association for Opinion Research (Vereeniging voor Opinie-onderzoek) in 1945.Footnote 39 This association distributed brochures and magazines to introduce opinion research and the recent literature on it to a wider audience, publishing the results of opinion polls held across Europe and North America.Footnote 40 Its main goal was to safeguard the ‘scientifically justifiable’ conducting of polls.Footnote 41 Ph. J. Idenburg, head of the NSS, claimed that the interpretation of the results of opinion research should be the preserve of ‘unbiased scholars’.Footnote 42 This emphasis reveals a rather widespread fear that these new techniques would be used improperly. After all, National Socialism, with its refined propaganda techniques, had recently shown how easily people could fall victim to manipulation. In 1946 a local Dutch newspaper reported that opinion polling was ‘only safe in the hands of experts’.Footnote 43 The publication of survey results was often accompanied by pieces on the methods employed, to make clear that effective polling required scientific expertise and equipment.Footnote 44 The fact that processing the survey forms required intelligent but expensive machines also contributed to the construction of opinion polling as a preserve of scientific experts and respectable organisations.Footnote 45

Thus opinion research in the Netherlands, although it quickly took off, was perceived to be something that needed to be contained. Prominent supporters, like those within the Dutch Association for Opinion Research, stressed that opinion polls could not and should not replace ‘democracy’, that is, a system of political representation in which voters placed their trust in the sound judgement of the representatives they sent to parliament.Footnote 46 Such a belief showed the persistence of the nineteenth-century notion of the ‘independent MP’ and of pre-war scepticism about the empowerment of public opinion, which reflected both fear of and disdain for the masses.Footnote 47 The system of political representation was meant to ensure that not mere ‘opinions’ but a rational debate among people who knew their facts would decide the course of government. Scientific experts stressed that opinion polls did not provide access to the people's pure and undiluted opinion due to their susceptibility to prominent opinion makers and propaganda, the object of another emerging field within the social sciences: mass communication studies.Footnote 48 Some, like the up-and-coming social democrat Joop den Uyl, argued against the abundant use of surveys that questioned people on issues on which they lacked the knowledge to make any ‘sound’ (verstandig) judgement.Footnote 49

In the immediate post-war years such scepticism about opinion polling was particularly strong among Social Democrats; other parties showed no significant interest in opinion research in its early years of existence. Much as in Britain, where Labour was very critical of opinion polls, Dutch social democrats of the Labour Party (Partij van de Arbeid, PvdA) mainly feared the effects of polls on a public that was, in their view, essentially ignorant and easily manipulable. The recent experience of National Socialist propaganda and mass hysteria clearly weighed heavily on this outlook. Social Democrats worried that the government would be tempted to treat opinion polls as a kind of referendum, whose outcome would affect the course of governance.Footnote 50 Scientists affiliated with the party's think tank Wiardi Beckman Foundation (Wiardi Beckman Stichting, WBS) acknowledged that polls offered new insights into the ‘secrets of our society’ (geheimen van onze samenleving).

Polls, nonetheless, also posed serious risks because they could prompt people to stop thinking for themselves and simply adopt a majority opinion on a given issue instead.Footnote 51 Social Democrats also stressed that the press had an obligation to carefully scrutinise poll results before making them public.Footnote 52 Outright hostility towards opinion research was to be found among Dutch communists. The communist newspaper De Waarheid did publish results of polls that aligned with their political ideas,Footnote 53 but when communists were increasingly marginalised politically, they used every opportunity to unmask opinion research as a manipulative, undemocratic instrument of the bourgeois political order.Footnote 54

Proponents of opinion research, conversely, were keen to stress how it could be applied as a powerful democratic tool – in 1945 the newly founded Dutch Government Information Agency (Rijksvoorlichtingsdienst) even characterised opinion research as a ‘requirement of democracy’. Opinion polls were indeed a very welcome instrument for the government and for political parties eager to get access to the hearts and minds of the people, and to grasp the undercurrents of popular political views and sentiments.Footnote 55 First of all, opinion polls provided people with an opportunity to vent their discontent, therefore helping to forestall demagogues who claimed to represent the will of the people.Footnote 56 Second, opinion polls could help to raise political awareness and a sense of participation among the people.Footnote 57 In this sense, they were understood to be an educational instrument which invited citizens to reflect on issues that were apparently important enough to be subjected to opinion research. Political elites, in turn, could benefit from opinion research to establish whether people might need to be ‘educated’.Footnote 58 This attitude reveals how opinion researchers understood themselves to be a morally and intellectually superior elite who put themselves in charge of identifying ‘incorrect’ (onjuist) opinions and the ‘contamination’ (besmetting) of public opinion by propaganda.Footnote 59 Third, proponents of opinion polls argued that opinion research empowered the people because it gave voice to those who normally remained unheard and had limited or no access to channels through which public opinion – in its old-fashioned sense – was expressed, like letters to the editor in newspapers.Footnote 60 Professor Jelle de Jong, a political scientist at VU University Amsterdam who began to study opinion polls in the 1950s, claimed that they could ‘partially bridge the gap between government and its subjects’ by broadening the expression of public opinion.Footnote 61 Finally, people like De Jong and polling agencies such as NIPO and NSS were eager to make the case for opinion research because polls also provided something for them. It gave them access to the world of politics: to government agencies, party committees and newspaper columns, which was where they articulated and promoted their expertise.

The Dutch reception of opinion research was typical of the disciplined democracy that emerged in other Western countries after the Second World War, in the sense of a representative system with a stress on order and harmony and restrictions on popular participation.Footnote 62 Treated as a ‘valuable instrument for the government and other political leaders’, opinion polls were also perceived as potentially dangerous to the system of parliamentary representation.Footnote 63 If used properly, opinion research could help to maintain an orderly democracy, for instance by showing where government policies were at odds with popular opinion. In that sense, opinion polls were a preferred alternative to potentially destabilising expressions of popular opinion like strikes or demonstrations.Footnote 64 The Dutch government indeed started to use surveys as early as 1945 in order to account for public opinion in the development of its policies.Footnote 65 This initiative was part of its effort to secure legitimacy: the government lacked a popular mandate because the first post-war general elections were not scheduled until May 1946. The political parties themselves were more hesitant about polls. Their reception and use of opinion research will be discussed as part of a more general scientisation of the (party) political in the early post-war years.

Post-War Electoral Research and Party Politics (1945–1959)

In the early post-war years, the Social Democrats and the Catholic Party, the two most powerful forces in Parliament, gradually began to make systematic use of electoral research. Against the background of what they perceived as an uncertain post-war political situation, they were very interested in grasping (shifting) voting preferences and the mechanisms behind them. The Catholic Party was particularly worried about the effects of secularisation, whereas the Social Democrats were concerned about the impact of rising affluence on voting behaviour.

The interest of political parties in electoral research was prompted by the rise of a new body of experts. In 1948 the University of Amsterdam was the first university to create a chair in political science, and other Dutch universities quickly followed suit.Footnote 66 Electoral and opinion research was one of the main subjects of interest among political scientists. It also enabled them to prove their value beyond academia. The links between social and political scientists and political parties were often very close. Partisan political think tanks acted as traits d'union. Many social scientists combined a position in academia or a think tank with an active role in one the political parties. Jan Barents, the first professor of political science at the University of Amsterdam, was also the first director of the social-democratic think tank WBS. After he left the WBS to focus on his academic career, he remained active within the PvdA as an academic expert on electoral strategy.Footnote 67 A similar network developed between the Catholic Party and social scientists working for the Catholic Institute for Social-Ecclesiastical Research (Katholiek Sociaal-Kerkelijk Instituut, KASKI), founded in 1947 and closely affiliated with the Catholic University of Nijmegen. The orthodox Protestant political party Antirevolutionary Party (Antirevolutionaire Partij, ARP), in turn, had close ties with the political science department of the orthodox Protestant VU University in Amsterdam.Footnote 68

The prominence of electoral and opinion research within the political sciences was characteristic of the empirical turn in the social sciences at mid-century, of which American political scientists formed the vanguard. A social-determinist perspective dominated electoral research, or psephology as it was called in Britain. The Columbia School of electoral sociologists in the United States and the ‘Nuffield Studies’ of British elections posited that voting was not based on political considerations but was prompted by the social group that voters belonged to.Footnote 69 Social-determinist readings of electoral behaviour was also dominant among Dutch social scientists. A. van Braam, for instance, a trained sociologist who was active in the PvdA, offered an analysis of the election results of the Social Democrats in urban working- and middle-class districts to check if his party's attempt to unite ‘workers of hand and brain’ – that is, to appeal to both working- and middle-class voters – was taking off. His statistical analysis showed that it wasn't. His attempt to offer an explanation ended in cliché-ridden statements about ‘feelings of discrimination’ among middle-class voters vis-à-vis workers and their supposedly ‘pretty negative’ stance towards politics.Footnote 70 Opinion research could have served to contest or corroborate such interpretations, but the Social Democrats still held on to their reservations about it.

The establishment of a range of partisan political think tanks and the development of close ties between social scientists and political parties inevitably resulted in a politicisation of electoral research. Social scientists took partisan stances and openly contested one another's interpretations of election results and voting patterns. These discussions show that the scientisation of the political did not bring about a fundamental reconceptualisation of political identity formation and political representation. Social scientists mainly operated within party political frameworks, which weighed heavily on their scientific approaches, theories and interpretations. A fine example in this regard are the discussions between Joop den Uyl, a social scientist who succeeded Barents as head of the WBS in 1949, and social scientists working for KASKI. Den Uyl tried to determine whether the PvdA's attempt to appeal to Catholic working-class voters was successful. After the war, the Social Democrats had set themselves the task of achieving a so-called breakthrough (doorbraak) in the political party landscape by calling upon Catholic working-class voters to leave the Catholic Party and join the ranks of the PvdA. Combining census data with election results, Den Uyl showed that a significant number of Catholics indeed no longer supported the Catholic Party, particularly in cities. These results clearly served the PvdA's propaganda strategy, which involved – rather desperately – looking for confirmation that its attempt to rule out religion as the prime marker for the formation of political identity among confessional voters was effective: that the Catholic Party had won the first post-war elections seemed to indicate otherwise.Footnote 71 The Catholic Party, in turn, was desperate to uphold the link between religion and party politics.Footnote 72 In a study of disappointing election results in the Catholic-dominated mining area of Limburg, Catholic social scientists argued that the unexpectedly poor showing was caused not by Catholic voters switching sides but by the migration of non-Catholic miners to the region.Footnote 73 Den Uyl responded with a scathing review of this study in the socialist newspaper Het Vrije Volk.Footnote 74

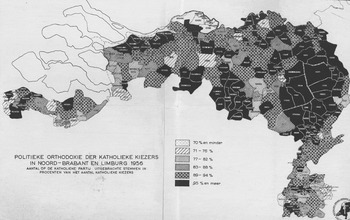

Electoral research also acted as a form of oversight. It informed political parties about the behaviour of those they perceived to be ‘their’ voters and showed where immediate action was necessary. In the 1950s the Catholic sociological institute KASKI produced a plethora of reports on electoral behaviour in various predominantly Catholic regions of the Netherlands, listing the percentage of ‘political orthodoxy’ per municipality: the number of people registered as Catholics was set against the number of votes the KVP had received in recent elections (see Figure 2). The link between religion and political affiliation was clearly perceived as self-evident and natural. Low levels of political orthodoxy were attributed to a decline in the number of people observing Communion.Footnote 75 Explanations for voting behaviour were thus primarily sought in assessments of whether and how people practised their religion, and rarely in Catholic Party politics itself.Footnote 76 In several analyses of election results Catholic voters who failed to support the Catholic Party were either represented as the passive victims of industrialisation and urbanisation – the main driving forces of secularisation – or characterised as being ‘opportunistic’ and naive, easily susceptible to mischievous propaganda.Footnote 77

Figure 2. Map showing the ‘political orthodoxy of Catholic voters in the province of Noord-Brabant and Limburg 1956’. The map shows that political orthodoxy was relatively low in the mining areas of southern Limburg and in the urban areas of Tilburg, Breda, ’s-Hertogenbosch and Eindhoven.

It was apparently completely out of the question that Catholic voters might consciously decide to support a non-confessional party while remaining Catholic in a religious sense. The abundant use of medical metaphors in these reports radiated the belief that low levels of political orthodoxy could be remedied.Footnote 78 Continuous social and political research was framed as a ‘political thermometer’ which ‘diagnose[d] the political health’ of Dutch Catholics.Footnote 79 Urban Catholic voters supposedly showed low ‘resistance’ (weerstandsvermogen) against developments that could lure them away from the church; particular regions were ‘stricken with’ (aangetast) decreasing political orthodoxy and had been ‘infiltrated’ by the Social Democrats.Footnote 80 The cure for this disease was simple: voters should learn to re-appreciate their religious and political identity as Catholics.Footnote 81 Catholic Party propaganda hence was mainly aimed at winning back voters by stressing the intimate ties between their Catholic faith and politics.Footnote 82

The Social Democrats had similar concerns. While the Catholic Party was worried about the effects of secularisation, in the 1950s the Social Democrats became rather obsessed with the embourgeoisement of the working classes:Footnote 83 when ‘working class’ people (classified as such on the basis of their economic situation) came to perceive themselves as ‘middle class’ due to rising general affluence, and increasingly adopted middle-class norms, values and lifestyles. Embourgeoisement played a pivotal role in explaining the PvdA's disappointing election results in the 1950s. A new, younger generation of voters, raised in a time of affluence and better educated than their parents had been, associated the Social Democrats with working-class interests, or so it was argued. Not voting for them was a way to express one's middle-class status and identity; therefore, in the long run, rising affluence threatened to marginalise the Social Democrats.Footnote 84 Dutch Social Democrats were well aware of similar fears among those in their British sister party and discussed the work of Labour sociologist Mark Abrams.Footnote 85

Such social-determinist interpretations remained dominant throughout the 1950s. In this respect, the Dutch scientisation of the political was in line with developments in Britain and Germany, where the Social Democrats also remained suspicious of opinion research and clung to a Marxist, social-structuralist reading of political identity formation throughout the 1950s.Footnote 86 This attitude would begin to shift in the following decade, when opinion research finally made its way through to the major political parties – a development that took place more or less simultaneously in Germany, Britain and the Netherlands. It led to new interpretations of voting behaviour and a reconceptualisation of the electorate, with the ‘floating voter’ starting to loom large over electoral research and the political parties’ electoral strategies.Footnote 87

Moving Beyond Social Determinism?

The seminal study that marked a shift in Dutch electoral research was Hans Daudt's dissertation Floating Voters and the Floating Vote: A Critical Analysis of American and English Election Studies, published in English in 1961. At the University of Amsterdam Daudt had been trained as a political scientist by Barents.Footnote 88 Like his mentor, he sympathised with the Social Democrats and joined PvdA committees, where he offered strategic advice for the party. In his dissertation Daudt argued against a social-determinist interpretation of voting behaviour by engaging critically with the Columbia School of Paul Lazarsfeld and others who had dominated the field of electoral research and political sociology in the 1940s and 1950s. Instead of linking political preferences to social characteristics such as religion, class and family traditions, Daudt argued that political factors helped to explain voting behaviour.Footnote 89 His research was part of a larger international trend to reconceptualise the notion of floating voters: those voters who cast their ballots for different parties in consecutive elections. Instead of explaining their behaviour as the result of political ignorance or a lack of genuine interest, Daudt and the American political scientist V. O. Key argued that these voters took the political parties’ agendas seriously and decided at the ballot box which best matched their own situation and needs.Footnote 90

Political parties across Europe picked up these ideas and sooner or later revised their approaches towards floating voters. In West Germany this did not occur until the 1970s, when social scientists working for the Christian Democrats reframed floating voters as ‘critical voters’.Footnote 91 In Britain, the Conservative Party was already taking them more seriously in the early 1960s. The electoral system was key here: to be first past the post Labour and the Conservatives needed the support of those voters who could not be labelled as staunch supporters of either party.Footnote 92 In the 1960s the Dutch Social Democrats also began to reconsider their approach towards this expanding segment of the electorate. Social determinism did not disappear, but it lost its dominance in explanations of voting behaviour. Reflections on a lack of support among middle-class voters, for instance, no longer stopped short at diatribes about politically ignorant and indifferent voters who failed to understand their condition. Instead, the PvdA started to take a critical look at its political agenda: a loss of electoral support could indicate a mismatch with the concerns on the electorate's minds.Footnote 93

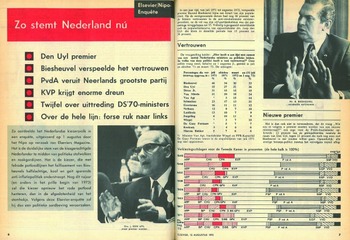

Now that the electorate's views were being taken more seriously, political parties, inspired by a new body of experts in the field of opinion research and marketing, tried to get into the minds of voters. From the late 1950s onwards the Netherlands saw an expansion of the field of opinion research via the establishment of new, commercial agencies such as the Institute of Psychological Marketing and Motives Research (Instituut voor Psychologisch Markt en Motievenonderzoek) and Bureau Veldkamp. Inspired by the Michigan School of electoral research, they introduced into political opinion research new social psychological approaches and techniques, including individual and panel interviews. Their approach enabled them to explore the conscious and unconscious motivations that guided popular (political) opinions and behaviour.Footnote 94 Established agencies like NIPO and NSS responded by also engaging psychologists.Footnote 95 Political opinion research was geared towards the gleaning of insights into voters’ perceptions of party politics, as well as their reception of political propaganda and their appreciation of a given party's electoral agenda (see Figure 3). It enabled parties to tailor their messaging to particular target groups and eventually, towards the end of the 1960s, resulted in a new conceptualisation of the electorate at large: parties now moved towards more open perceptions of the electorate, accounting for the preferences of individual voters instead of viewing them as determined by social structures.

Figure 3. During election campaigns newspapers and magazines repeatedly made news out of opinion polls. In August 1972 Elseviers Magazine predicted that in the next election voters would bring about a ‘political earthquake’

In contrast to Britain and West Germany, where the Tories and the Christian Democratic Union (Christlich Demokratische Union, CDU), respectively, were the first parties to systematically use opinion and marketing research, in the Netherlands the Social Democrats took the lead, regularly using opinion research from the early 1960s onwards.Footnote 96 Much like Labour in Britain, disappointing election results in the 1950s played a part in this change of heart: after all, the Social Democrats had been rather sceptical about polling in the immediate post-war years. Moreover, a new generation, many of whom had been trained in the social sciences, took control of the PvdA and its think tank. Ed van Thijn, the party's most influential political and electoral strategist in the 1960s and 1970s, had studied political science at the University of Amsterdam under Daudt. Still, like the officials of Labour and the Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, SPD), Dutch Social Democrats were keen to stress that their use of opinion research did not mean that ‘the wishes of “the market”’ now dictated party politics.Footnote 97 The Social Democrats were still eager to maintain that party politics rested on a firm ideological basis. In 1965, in a meeting of the party's committee on electoral research, Van Thijn stressed that although the results of continuous opinion research carried out by NIPO should be ‘taken into account’, they ‘should not influence policy’.Footnote 98

In 1964 Van Thijn travelled to Britain and West Germany to explore how Labour and the SPD approached the upcoming general elections in each country. He also developed an interest in US election campaigns.Footnote 99 These trips had a profound impact on him; many of the ideas he picked up abroad were implemented in the Social Democrats’ election campaigns in the second half of the 1960s. First, on his return to the Netherlands Van Thijn stressed that Labour and the SPD had focused their election campaigns on ‘target voters’ or ‘Zielgruppen’, which he translated as ‘sleutelkiezers’ (literally: the key electorate), which was in fact another word for floating voters. Van Thijn argued that electoral research was needed to establish the make-up and background of the sleutelkiezers, so that the party could conduct an effective election campaign. Second, his visits had convinced him of the need to concentrate election campaigns on a couple of key issues that were high on the minds of the party's core electorate and the sleutelkiezers alike. Third, public relations experts and marketing researchers should be given a key role in designing election propaganda and checking its reception by the electorate. This plan was quickly put into effect: on Van Thijn's Party Committee on Electoral Research and Presentation, ‘regular’ party members including Den Uyl, party leader Vondeling and a range of MPs were soon outnumbered by opinion experts, amongst others copywriters, the director of an advertising company, one of the directors of NIPO and several sociologists and social psychologists.Footnote 100

The discussions by this committee and others like it reveal that social determinism had lost much of its explanatory force. Voters were increasingly portrayed as active, opinionated citizens. In internal discussions about party strategy in the 1960s, Social Democrats repeatedly referred to ‘the average voter’ and ‘every Dutchman’ (elke Nederlander) as a point of reference for party propaganda, much like the German SPD, which had started to perceive voters as ‘consumers in an open marketplace’.Footnote 101 Some even suggested abolishing the concept of worker (arbeider) altogether because the party's traditional working-class voters no longer identified themselves as such.Footnote 102 Instead, the Social Democrats introduced new, non-social-structuralist categories like the so-called ‘voters susceptible to culture’ (cultuurgevoeligen) – a category of floating voters who favoured constitutional reform.Footnote 103 This new reading of the electorate clearly reflected the impact of social-psychological approaches to electoral research which focused on voters’ attitudes and opinions towards political issues and aspects of the political system.Footnote 104

Other parties gradually followed suit. Already in 1955 a young, ambitious member of the Catholic Party's board had tried to convince his colleagues of the benefits of marketing and opinion research. Norbert Schmelzer was, however, apparently pushing things too far with his suggestion of hiring a neutral, non-Catholic institute like NIPO to conduct research on voters’ motivations and their reception of the content and form of Catholic Party propaganda.Footnote 105 The KVP preferred to stick with KASKI, which resulted in yet another report that presented voting as a ‘pastoral concern’.Footnote 106 In 1964 the foundation of the Institute for Applied Sociology (Instituut voor Toegepaste Sociologie, ITS) at the Catholic University of Nijmegen marked a move away from the religious-based interpretations of voting behaviour that had dominated KASKI's reports.Footnote 107 Towards the end of the 1960s a new generation of political scientists, trained in Nijmegen in an increasingly progressive climate, started to feed the party with reports showing that confessional-based politics was outdated.Footnote 108 In response to the evaporation of the seemingly self-evident ties between religion and politics the KVP toned down references to religion in its election propaganda and instead focused its campaigns on key, mainly socio-economic concerns of the electorate, such as safeguarding and maintaining affluence and enabling property acquisition among the working classes.Footnote 109

Containing Scientisation

There were, however, limits to the scientisation of the political – to the impact of scientific expertise on the conduct of political parties in the 1960s.Footnote 110 As Beers has shown for Labour in Britain, Dutch parties held on to a conceptualisation of political representation in which parties aimed to shape and lead public opinion rather than merely follow it. Although opinion and electoral research exerted an evident impact on a party's approach towards and perception of the electorate, such research was always embedded in a party political context in which strong convictions, ideological considerations and political contingencies also played their part. In this context the proponents of opinion research often found themselves sidelined. The Dutch Social Democrats are a case in point. Again, the political scientist-cum-party-strategist Van Thijn offers a useful example to explore how parties negotiated, appropriated and contained electoral and opinion research.

In the second half of the 1960s Van Thijn not only had his mind set on professionalising campaigning, he also wanted to change the political landscape as such. His reports on election campaigns in Britain, the United States and West Germany show that he was clearly charmed by the workings of a two-party system. Like many other Social Democrats, Van Thijn was frustrated about the key central position of the KVP and two other confessional parties in the Dutch political landscape. Elections were in essence about whether these parties would either form a left-leaning coalition government with the Social Democrats or turn to the right by seeking to cooperate with the liberal People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie, VVD). Van Thijn turned to the theories on democratic systems of Schumpeter, Sartori and Daudt to find a way out of this dynamic: elections, he argued, needed to enable voters to make a decision about who would govern, and therefore the Dutch political system of coalition governments must make way for a two-party system in its stead.Footnote 111 To this end, the Social Democrats introduced in 1966 their ‘polarisation’ strategy, aimed at forcing the confessional parties to leave the political centre and join either the progressive or the conservative ‘pole’.Footnote 112 This new political and electoral strategy was based on research showing that voters were keen to choose between different, clearly stipulated political agendas. A two-party system would ensure them that this agenda would be put into action if the party of their choosing won a majority and could govern according to such a mandate – rather than being considerably watered down in a coalition government.

In the second half of the 1960s polarisation became the Social Democrats’ new mantra. Once the PvdA had convinced itself that polarisation was the way to achieve a progressive majority in parliament and thus marginalise confessional politics, research that contradicted this assumption was downplayed or ignored.Footnote 113 A series of electoral victories, and the fact that confessional parties were losing ground, seemed to indicate that polarisation was a success.Footnote 114 On various occasions during the 1970s, however, the party's think tank WBS showed that voters were not abandoning the political centre; the party thus still had much to gain by tapping into it. The polarisation strategy, however, did not allow for this, because it was based on the conceptualisation of the political centre as a position marked by indecisiveness, vagueness and a lack of political principles.Footnote 115 In essence, it was aimed at getting rid of the centre altogether.

In the 1970s the Social Democrats were confronted with the failure of polarisation: long negotiations among the three confessional parties eventually resulted in the foundation of a new Christian-democratic party the Christian Democratic Appeal (Christen-Democratisch Appèl, CDA), which first participated in the 1977 general election and firmly established itself in the political centre.Footnote 116 The new party managed to halt the heavy losses suffered by the confessional parties since 1967, winning one third of the seats in parliament in 1977. Meanwhile, although the Social Democrats won the biggest victory in their history and became the largest party in parliament, they ended up in the opposition: their aggressive polarisation strategy had cast a large cloud over their relationship with the Christian Democrats who – after a failed attempt to reach an understanding with the Social Democrats – formed a coalition government with the VVD.Footnote 117

The foundation of the CDA is itself an illustration of the tensions between social science research and the practices of party politics. The merger of three confessional parties was far from an easy process, with long-drawn-out discussions about the party's new profile lasting from 1967 to 1976. Building on research showing that voters based their decisions on political issues, not religious principles, many prominent Catholic politicians favoured the establishment of a broad-based people's party in which religion would no longer play a profound role. The Protestants of the ARP and the Christian-Historical Union (Christelijk-Historische Unie, CHU), by contrast, were very critical of ‘following public opinion’ because to do so would run counter to the very ‘essence’ of their party, which aimed to lead society along the righteous path of the Lord.Footnote 118 They therefore strongly favoured the establishment of a truly Christian-democratic party. When a member of the CHU's social-scientific institute travelled to Germany to get a behind-the-scenes look at the election campaign of the German Christian democrats of the CDU, she was surprised and appalled to find that they ‘spoke a totally different language’ and made hardly any references to religion.Footnote 119

The discourse through which social scientists narrated political representation was thus contrasted with an approach to politics that surpassed such ‘cold’ categorisations. Although political scientists played their part in committees discussing the merger, in the end the establishment of the CDA first and foremost came down to a negotiation of distinct party traditions. A religious approach to politics prevailed. In preparation for the 1977 general elections the CDA proudly claimed that it was ‘far more than a sociological category with a vague mentality’ because it was grounded on the Gospel.Footnote 120

Finally, the containment of the scientisation of the political was also made visible by a public debate about the nature and impact of political opinion research. In a sense these discussions were a reworking of the debate that followed the introduction of opinion research immediately after the Second World War. In the late 1960s the same mass media organs that commissioned opinion research and extensively discussed its results also broached the issue of the reliability of opinion polls and their effects on political parties and on the electorate. Newspapers and opinion magazines examined the ‘facts and fables’ of political opinion research, among them the tricky issue of election polls, which supposedly not only reflected but also shaped the political opinion of voters.Footnote 121 In 1970 the Social Democrats were accused of leaking and manipulating the results of an opinion poll to show that the Catholic Party was losing ground.Footnote 122 Political scientists themselves also publicly questioned the validity of opinion research and the way its results were interpreted. One political scientist compared such interpretations with the reading of tea leaves and argued that they were far from objective and were often inspired by party political motives.Footnote 123

News coverage of elections were balanced between reports on the campaign as such and an increasingly popular genre that focused on how campaigns were conducted, looking specifically at the role of spin doctors, marketing experts and opinion researchers.Footnote 124 This sort of meta-coverage was in sync with the broad impact of critical social theory, which criticised supposedly value-free statistical research on social developments.Footnote 125 It shows the advent of what in studies on the scientisation of the social has been labelled ‘secondary scientisation’: the scientisation of the political was not taken for granted but scrutinised, first and foremost by the news media, which were keen to unmask the artificial and manipulative nature of politicians’ behaviour.Footnote 126 Hence throughout the 1970s, although polls and electoral research had become firmly established as an instrument of media and party politics, a more critical attitude towards them emerged.Footnote 127 In addition, political parties started to tap into a new body of expertise within the field of media and communications (a discussion of which falls beyond the purview of this article): TV and marketing experts aimed to bolster a politician's ‘image’ in the media, while communication experts used, among other techniques, mock election debates (including a noisy, unwelcoming audience) to prepare politicians for battle.Footnote 128

Conclusion

Exploring the interaction between social scientists and party politics has helped us to uncover shifting notions within political parties about political representation and political identity formation. In the 1940s and 1950s electoral research helped parties to track the behaviour of ‘their’ particular political constituency, which was still perceived to be a stable community of people united around class or religion-based identities. Key social-scientific narratives of secularisation and embourgeoisement became prominent among social scientists and party strategists alike, and served to explain and project shifts in electoral behaviour. Sociological research – and its increasingly advanced quantitative techniques – were used to acquire detailed knowledge of the electorate and to design strategies aimed at maintaining or restoring the self-evident ties between class or religion and party. Opinion polling and the electoral research that was based on it made its way to the Netherlands in the immediate post-war years. After first meeting with scepticism, it was accepted as a useful tool, but parties were also keen to maintain their status as groups who shaped and led public opinion, occupying the vanguard of a broader political community.

In the 1960s Social Democrats, followed by the Catholic Party, began to systematically use opinion and electoral research. In this diffuse process, academics and academically trained experts played a crucial role. A broad range of social scientists, from electoral geographers to mass psychologists and political scientists, were involved in the scientisation of the political. Many were active in the social-scientific think tanks founded by Dutch political parties after the Second World War, which served as important links between party and academia, leading to a simultaneous politicisation of social science.

How does the scientisation of the political in the Netherlands compare to developments abroad? We have shown that the scientisation of the political, and more generally the running of election campaigns, were inspired by foreign examples, mainly from Britain, Germany and to a lesser extent the United States.Footnote 129 The visits abroad by party representatives served two purposes. On the one hand, Dutch Social Democrats and Christian democrats were impressed by the professional approach of their sister parties. Van Thijn in particular was keen to follow the example of Britain's Labour in systematically using electoral and opinion research. On the other hand, these visits also contributed to the perception of Dutch party politics as being different from their foreign counterparts. Although the CDU and most of the other Christian-democratic parties in existence across Europe in the 1970s did not approach politics from a confessional perspective, Dutch Christian democrats were strongly invested in the powerful tradition of confessional politics in the Netherlands and were not ready to leave it behind. Dutch Social Democrats, in turn, argued that as long as they had to deal with a multi-party system, they could not afford not to treat the working class as their core electorate for fear that socialist fringe parties would steal their thunder.Footnote 130

The scientisation of the political was, thus, far from absolute. Although the new conceptualisations of the electorate the social-scientific research offered them did penetrate party politics, social-determinist conceptualisations did not disappear altogether. In the second half of the 1960s new theories on voting behaviour had a major impact on the PvdA's political strategy, but research that indicated its ineffectiveness in the long run was ignored. In the 1970s secondary scientisation set in, as the media developed a critical perspective on the rise of experts and the use of opinion polls. Meanwhile, that same media were also given to polling frenzies and, by letting the polls dictate the rhythm of their reporting, narrated elections as tense and exciting competitions.

The limitations of the scientisation of the political had to do with the specificities of the Dutch polity, which prioritised the politics of ‘principle’ in a proportional system in which different parties had to guard their specific constituencies. Operating within a multi-party system, Dutch parties held on to the self-understanding that they were the representatives of a particular political community longer than the major parties in Britain and West Germany did, since Labour competed against the Conservatives, and the SPD against the CDU, in their respective two-party systems. Moreover, the fact that at least up until the 1960s the scientisation of the political was often embedded in partisan institutions like the parties’ think tanks also played its part in maintaining a social-determinist understanding of electoral behaviour. The reports by KASKI are a fine example of this. By contrast, the sister parties abroad gradually abandoned such interpretations in the 1960s and 1970s.