If aesthetics is ever to be more than a speculative play, of the genus philosophical, it will have to get down to the very arduous business of studying the concrete process of artistic production and appreciation.

—Edward Sapir

INTRODUCTION

This article is concerned with how Laura Tohe, a Navajo poet, connects both to audiences and to her own past through the feelingful attachments evoked through and by her performances. In that respect, I am concerned with understanding and analyzing the role of the individual and the individual articulation of a life story in Navajo poetry performances. In particular, I am interested in three performances of putatively the same poem by Tohe. One performance is the written orthographic poem. The other two are oral performances that I recorded. In this article, I will argue that a focus on the individual performer and on multiple performances can provide insight into the relationship between linguistic and narrative constructions of self and identity within the constraints and opportunities particular mediums and contexts provide. I will also be concerned with the attachments that people (here, poets) bring to bear on aesthetic practices – what David Samuels (2004: 11) has termed “feelingful iconicity.”

Instead of focusing on a unified Navajo style, I want to engage with the individual performers and performances. It is in looking to individual performances that I believe we can better understand Navajo linguaculture (see Friedrich 2006:219), the locus of which is the individual (see Sapir 1927, 1938; Friedrich 1986, 2006; Johnstone 1996, 2000; Sherzer 1987). Recently, Deborah House (2002) has attempted to examine “narratives of Navajoness,” yet her analysis is often superficial with respect to the linguacultural details of those narratives. In turn, this essay takes a discourse-centered approach to these performances (Sherzer 1987, Urban 1991). In so doing, I look at several key discursive features employed by Tohe in her performances of this poem. I pay particular attention to Tohe's shift from using the ethnonym “Diné” in the written version to “Navajo” in the oral versions. By focusing on such a narrow alternation and the contexts in which it occurs, I hope to raise into relief the relationship between the individual performer and the context of performance (Brenneis & Duranti 1986, Bauman 2004, Bauman & Briggs 1990). In so doing, I want to show what careful attention to the linguaculture of these performances and what they can and do suggest about the actual, real-time production of “narratives of Navajoness.” I want to establish “narratives of Navajoness” not as abstractions, but rather as living discursive productions.

Following on the work of Sapir 1921, Hymes 1981, Friedrich 1986, Sherzer 1987, and Johnstone 1996, I also want to argue for understanding language and the performance of poetry as an aesthetic practice locatable within individuals. I want to look then at language as artistic and creative (see Johnstone 1996:180–81). Language is produced and circulated, creatively and artistically, by individuals – individuals who are often – (but not always; see Silverstein 1981) – attuned to their language production. Navajo poets, as poets, are self-consciously aware of their poetic productions and of language as artistic and creative. In focusing, then, on the felt connections to language, on the performances and contexts of the use of language through poetry to tell “a story,” and on the individual artistry of the performer in the creation of that “story,” I hope to show how “narratives of Navajoness” are actually produced and circulated.

In what follows, I will outline some of the recent perspectives on language and identity. I will pay attention to the use of language as an emblem of identity, but I will also view identity as a kind of storytelling, a kind of history that is told by individuals. I will suggest a view that takes the individual and the contexts and medium of performance seriously. I will then turn to an analysis of the three versions of the performance of a poem by Laura Tohe. I first analyze the various correspondences of line structure in the three versions. I also look at lexical differences between the versions. I then conclude by relating these features to the larger performance context of the versions and suggest how the study of the individual voice can aid in illuminating larger issues in the study and analysis of group traditions. First, I want to address briefly issues related to the feelingful connections to language and the influence that may have on individual performers.

FEELINGFUL ICONICITY AND APACHEAN POETICS

Navajo is a Southern Athabaskan language, linguistically and to various degrees culturally related to those of other Apachean-speaking peoples (Rushforth & Chisholm 1991). It has been a hallmark of some of the more sensitive research on Apachean poetics to focus on the individual (Basso 1996, Samuels 2004). Here I want to draw attention to the work of Basso 1996 on Western Apache place-naming practices and of Samuels 2004 on Western Apache musical practices. Basso 1996 shows how Western Apaches can use place names to evoke and circulate a “moral landscape.” The place names connect to specific narratives that allow Apaches to focus both on the words of the ancestors who named the location and also the events that happened at places and the moral ramifications of those events in their own lives. Central to Basso is how an individual's life history is implicated in the use of such place names. Another feature is the feelingful evocation of language through place names.

More recently, Samuels 2004 has shown how the contemporary production and circulation of music is keyed to individuals. Samuels examines the feelingful qualities of music that, while superficially “country” or some other genre, is actually deeply evocative of individual Western Apache life histories and experiences. Such a focus on individual experience and poetics blurs distinctions such as “Western music” versus “Apache music.” Indeed, it is the importance of “feelingful iconicity” that I want to address throughout the rest of this article. Feelingful iconicity is, as I understand it, based on the “emotional attachment to aesthetic forms” (Samuels 2004:11).

What I want to do here by focusing on the performances of a single Navajo poet is to blur some putative distinction between “Western poetry” and “Navajo poetry,” for in the final analysis it is both and neither simultaneously. Moreover, it is feelingfully Tohe's poetry, and as an evocation of boarding-school dynamics, it can be feelingful for specific audience members. I also want to argue that, like Apaches' singing in English, the feelingful attachment to poetics crosses languages. We need to respect, as Samuels does, the felt connections that Navajo poets have to English and the ways that English and Navajo can be commingled to produce differing feelingful connections.

Although the poems are in English, they are clearly salient to other Navajos who attended boarding schools and who understand the categories of “cat” or “stomp” that were associated with the boarding schools. As such, Tohe's poem is an “ethnographic” account of the use of categorization by young Native Americans (particularly Navajos). More than that, however, it is a feelingful way for Tohe to connect with various audiences about a shared or potentially shared life experience. That the poem is in English may well connect with the English-only policy in place at the Albuquerque Indian School during the 1950s. And as such, the language of the poem may connect for both poet and audience to larger issues of domination. However, the poem is also a feelingful evocation of a part of Tohe's own biography. There is a tension in this poem, a tension that is stated explicitly when one audience member shouts out “AIM,” between the nostalgia for childhood and the oppressive and controlling power of Indian boarding schools (Iverson 1998). I will return to this point below.

The work by Basso and Samuels described above, as well as other work on Southern Athabaskan ethnopoetics (Toelken & Scott 1981, Basso & Tessay 1994, Webster 1999, Greenfeld 2001, Nevins & Nevins 2004),1

For useful recent discussions of Navajo poetics see Field & Blackhorse 2002 and Webster (2006c) and references therein.

Friedrich 1979, 1986, 2006, Hymes 1981, 2003, Sherzer 1987, 1990, and Becker 1995 have focused ever more closely on the place of the individual in culture and language studies. These writers have located “language” within the individual, looking at individual creativity and suggesting that language may be overlapping individual systems (leaky systems, at that). More recently, Johnstone 1996, 2000 has argued for placing the individual in the forefront in discussing language. The focus, then, is on individual speakers and how they create, momentarily, language or discourse – byproducts of Bakhtin's (1986) notion of language as speaking subjects. Talk, individual talk, is where human beings display, – consciously or unconsciously, – their individuality (see Johnstone 2000). Individuals possess felt connections to language and language forms.

Ethnopoetics, as a theory and a method, is meant to appreciate linguistic artistry as an individual accomplishment, predicated – no doubt – on the potentials and possibilities inherent in each language, but also on the individual artistic actualizations of those potentials and possibilities (Hymes 1981, Tedlock 1983, Sherzer 1990): the “poeticization of grammar,” in Sherzer's term (1990:18). Friedrich's (2006) recent review of ethnopoetics argues for bringing ethnopoetics to the forefront within linguistics and anthropology. Sherzer's (1987, 1990) call for a discourse-centered approach to language and culture is an obvious outgrowth of ethnopoetics, and once again looks to individual linguistic creativity as a central locus for understanding culture. As Friedrich (2006:219) writes, “Culture is a part of language just as language is a part of culture and the two partly overlapping realities can intersect in many ways – for which process the term ‘linguaculture’ may serve.” And the individual, the individual speaking subject – the poet – is inextricably bound up in and producing of linguaculture.

Likewise, I follow Bauman 1984, 1986 and Hymes 1981 and see performances as individual achievements within specific sociohistorical moments. It is important to understand, for example, the various demographics of the audiences before whom Tohe performs. As Bauman (2004:2) writes:

Social life [is] discursively constituted, produced and reproduced in situated acts of speaking and other signifying practices that are simultaneously anchored in their situational contexts of use and transcendent of them, linked by interdiscursive ties to other situations, other acts, other utterances.

Tohe's performances call forth images of the boarding school, where Native American children were taken – often against their will – and forced to conform to some hyper-ideal view of “Western/Modern” American society. In the performances to be discussed below, we will see how the audiences and the contexts of the performances, situate and calibrate the use of “Navajo” or “Diné,” for example; but I also want to stress is the ways that the creativity of an individual speaking subject can transcend those moments. This is, I believe, the key to understanding feelingful iconicity. Feelingful iconicity is not just attachments to aesthetic forms, but also the ways that they can transcend the situated real-time moment of performance.

ON IDENTITY AND LANGUAGE

Sociolinguists have often looked at the group to describe variation; they have in some measure neglected individuals as the locus of variation (this is made evident in the actuation question; see Johnstone 2000:409). Another approach, the one I take here, looks at individual speakers and the utterances that they create. This is the approach that Hymes 1981 and Sherzer 1990 take: Look at individual narrators and their creativity, their style, and how it is socially located. How do we understand Navajo poetry styles? This may be the wrong way to look at this question. A better question might be: What are the styles of individual Navajo poets? One option is the embedding of poetry in storytelling. Another option, treating poems as isolated objects, occurs among younger Navajo poets (see Webster n.d.). These options – or perhaps constraints – are actualized for reasons; that is, individuals have agency; they invoke rhetoric and strategy. Tohe, for example, performs the three versions (one written and two oral) for reasons. Each version is a specific utterance of a creative individual coproduced – certainly – by the audience (see Brenneis & Duranti 1986). I am not interested in constructing some composite narrative of Navajoness; instead, I want to look at specific individual articulations of narratives of Navajoness.

The question of identity is important here. I follow Spicer 1975 and see identity as the ways people tell and retell, imagine and reimagine their histories. Like Basso's (1996) discussion of Western Apache place names as highly descriptive, but from a particular vantage point (the structure of the place names reflects the orientation of the ancestors when they first saw the places), identity also is to be seen from a particular vantage point.

Le Page & Tabouret-Keller 1985 have argued for the shifting nature of identity, urging us to see identity as “acts” that can be managed through linguistic resources. In some ways, Silverstein's (2003) discussion of “emblematic identity displays,” where certain linguistic features can be put on display as emblems of identity, also speaks to the contingent and socially constructed view of identity. Language, because it is often salient, functions in various ways as an identity marker, both as an index of identity and, at times, as an icon of that identity. Both Errington 1998 and Kuipers 1998 focus on language and identity in Indonesia and on the shifting nature of identity in connection with changes in local languages. Both look at situated moments of “talk” – moments of code-switching, for example – as locations for identity work. Likewise, Kroskrity 1992, 1993 shows how Arizona Tewas have attached great ideological value to their language and certain domains of its use (e.g., kiva speech). These approaches see language again as an emblematic display of identity. I certainly agree with this position in large measure, and below I will discuss the use of Navajo clan names as just such an emblematic identity display.

Recently, House (2002:43–55) has posited “narratives of Navajoness” based on her work at Diné College on Navajo language shift. My understanding of House's use of “narratives of Navajoness” is that they are discursive uses of stories to assert a “Navajo” identity. She summarizes and presents modest examples in English of how various Navajo educators talk about “Navajoness” and being Navajo. However, House's publication lacks both significant detailed discussion and examples of language in use. We get composite narratives, narratives as abstractions, and not detailed analysis of specific narratives of Navajoness. That said, House's work, as well as the above mentioned work on language and identity, suggests that identity should not be understood as an immutable, essentialized quality (see Kroskrity 2000; see also Blot 2003), even when some Navajos do describe language as an essential feature of being Navajo, as House's (2002) research and my own fieldwork show. This is, I would argue, a form of feelingful iconicity.

Although it may seem obvious, I want to point out that using English does not always or irretrievably index “colonizing” ways of speaking. Navajos – and this point is more general, I believe – have not simply been forced to speak English and passively accepted it. Rather, they have engaged with English and actively adapted it.

The difference between House's (2002) work and mine is that I want to look at specific instances of language – in this case, English with some Navajo – in use. My work is discourse-centered in the micro-level sense (Sherzer 1987, Urban 1991). I believe that to understand narratives of Navajoness, we must attend to the particulars of individual performances. By “Navajoness” I mean merely that a certain self, a certain identity is constructed and understood as Navajo.

In Tohe's poetic tellings and retellings of her poem “Cat or stomp,” she is certainly using language as an emblematic identity display at times (her introduction in Navajo, to be discussed below, for example), and she is also using narrative, the tellings and retellings of her history from a particular perspective, as a way to assert and circulate her unique identity as a Navajo (cf. Spicer 1975). Indeed, this article itself exemplifies the ability – as described by Bauman 2004 – of stretches of discourse to be decontextualized from one context (a performance at Window Rock) and recontextualized elsewhere (an article in Language in Society). In so doing, it circulates Tohe's “history.” They are Tohe's individual narratives of Navajoness.

While the tellings and retellings of her history and the use of emblematic displays all work toward shifting constructions of identity, I would like to pause and reflect again on Sapir 1927 and its more recent articulation by Johnstone 1996. In Sapir's article “Speech as a personality trait,” he seems to be arguing for a perduring sense of personality. As Sapir notes, we can affect certain pronunciations for social reasons (language as an “act” of identity), but is there not also something that is perduring? Can we not discern certain relatively perduring features of speech that may not be unique to the individual? This is what, I believe, Johnstone 1996 is implying when she urges the investigation of the “linguistic individual.” If we look at the individual performances of Laura Tohe, will we not, at some point, begin to understand what is uniquely hers? Will we see language not just as the relative sharing of a lexical grammatical code, but also as the felt attachments that individual speakers have to the production and circulation of that language – what we might, following Sapir, term the creative speaker? By focusing on these three performances by Laura Tohe, I want to understand the variations not just as responses to context (they are) but also as her unique responses to those changing contexts.

PERFORMANCES OF POETRY ON THE NAVAJO NATION

The research for this article was conducted on the Navajo Nation reservation from June 2000 through August 2001. The Navajo are the largest Native American group in North America.2

For general discussions concerning the Navajos and the language/culture nexus among Navajos, see Kluckhohn & Leighton 1962, Witherspoon 1977, and Farella 1984.

My primary research concerned the emergence and circulation of Navajo orthographic poetry and its relation to oral tradition (Webster 2004, 2006c). However, as I soon realized, many Navajo poets also perform their poetry, and I began to videotape and audio record those performances.3

The reading of poetry as a performance act is an interesting topic. Haviland 1996 discusses “texts from talk” among Tzotzil-speaking and writing peoples. He shows how verbal art becomes an orthographic document through the textualizing practices of Tzotzil peoples. There is much to recommend about this example. I should note, however, that what I am describing is not just “texts from talk,” but “talk from texts from talk.” Another way to think about this concerns Fabian's (2001) notion of “reoralization.” I have discussed some of the issues concerning literacy and orality elsewhere (see Webster 2004, Webster 2006b; see also Collins & Blot 2003).

The primary language in which Navajo poetry is written is English. This has to do with the fact that, although Navajo is still spoken by many residents on the Navajo Nation, literacy in Navajo is still not widespread (see McLaughlin 1992, Lee & McLaughlin 2001). Indeed, poets like Laura Tohe have actively begun to learn how to write in Navajo so that they can write poetry in it. Recently, Tohe published a collection of essays and poetry (2005) that includes poems in Navajo. During my fieldwork, she had begun to perform poems written entirely in Navajo, and she had also published and performed poems that code-switched into Navajo. Still, many of Tohe's poems are in English, and it is often through English that she asserts a Navajo identity. English makes Tohe's poems more accessible to the larger, non-Navajo English-speaking society, but – and this is in no way trivial – they are also more accessible to many young Navajo readers who are not literate in Navajo (and with the growing language shift, non-fluent Navajo speakers as well; see House 2002, Spolsky 2002). Indeed, for many Navajos who are not literate in Navajo, poetry composed in Navajo is still largely accessed as an oral phenomenon. Navajo poets who write in Navajo often perform their poems on KTNN (the Navajo radio station) or at public venues such as described below.

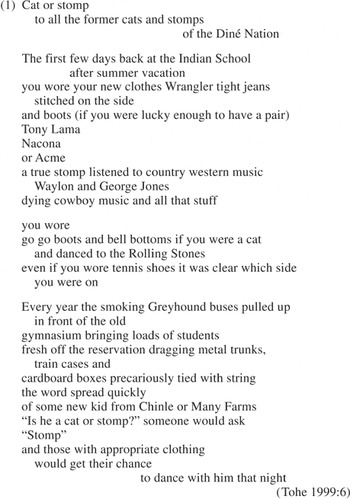

In what follows, I will present the three versions of Laura Tohe's poem “Cat or stomp.” The orthographic version is from her 1999 book No parole today, which focuses on Tohe's experiences in boarding school; its title works on two levels, one intentional and one discovered. The first sense of “parole” is that of a prisoner in jail, reflecting an attitude toward the boarding school as a prison. The second sense deals with the distinction Saussure made between langue and parole, where parole represents speech. So in this sense the title reads “no speaking/speech today.”4

This sense was discovered by Tohe in the following manner: In an interview I conducted with Alyse Neundorf, I pointed out that “parole” could be understood in two senses, with the French sense resonating with the theme of Tohe's book. Neundorf then told this to Tohe, and Tohe then stated that she had just found out about this second sense of the word – which she thought fit nicely – at a poetry reading in Window Rock, Arizona, on 18 July 2001.

The poem under consideration here, however, deals with which “group” a person belonged to during his or her time at boarding school. The names for the groups were “cats” – who listened to rock and roll, wore bell-bottoms, and the like – and “stomps,” who listened to country music and wore Wrangler jeans and cowboy boots. The distinction between “cat” and “stomp” was widely known to a certain generation of boarding school students, and in many ways this poem is a bit of boarding school nostalgia.

The first oral version is from Laura Tohe's performance of this poem at the Native American Music Festival held in Diné College in Tsaile, Arizona, on 8 June 2001. She had been invited to the festival by the president of the student-run Diné College Music Club, who had met Tohe in January 2001, when she and three other poets had put on an impromptu poetry reading at Diné College. The president, Daniel,5

“Daniel” is a pseudonym.

The audience for Tohe's reading was still quite large at the 10:00 pm starting time. It included both young and middle-aged Navajos. The stage was in front of the Ned Hatathli Building, and the audience stood or sat in the parking lot. Lights shone on Laura Tohe, making her visible but leaving the audience invisible – as she stated, “Can't see you, but I'm glad to be here.” Tohe was the only poet to read on the first day of performances; the other performers had offered a variety of musical genres.

The final version was performed at the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock, Arizona, on 18 July 2001. The event was put on by Luci Tapahonso and Monty Roessel in conjunction with a writers' camp that Roessel runs annually at Rough Rock Demonstration School. The camp is for high school students and brings in a variety of writers, including poets like Luci Tapahonso and Shonto Begay, but also journalists and academics like Mark Trahant and Peter Iverson.

This event brought together an unusually large number of Navajo writers performing their work in a public forum, including Tohe, Luci Tapahonso, Irvin Morris, Blackhorse Mitchell, Nia Francisco, Rex Lee Jim, Esther Belin, and Sherwin Bitsui. In the lobby of the museum people could purchase books written by the poets, who were also signing their works.

In attendance were a number of educators from the Navajo Language Academy, as well as photographer Monty Roessel and poets such as Alyse Neundorf and Rutherford Ashley. The auditorium was packed with people. Some sat against the walls on the steps. In the audience were older Navajos, teenagers from the writers' camp, and young children. The audience, as at the Native American Music Festival, was overwhelmingly Navajo.

In the following presentations of the oral performances, I begin before the actual poem is read because the poem is embedded within a certain performance style and narrative. It does not appear out of nowhere; rather a narrative is constructed that makes the appearance of the poem seem “natural.” Lines have been separated based on breath pause and intonation contours. Short pauses mark lines, and longer pauses mark stanzas. There is a general tendency for each new line to begin at a slightly higher pitch and then trend downward and coincide with a breath pause. Audience responses are given in brackets. Initial particles such as and, then, and now are not used in the poem with great regularity, nor are similar Navajo forms such as ‘áádoo ‘and (then)’, ‘áko ‘then’, or k'ad ‘now’. This may be a byproduct of writing (see Schiffrin 1987 on the use of these discourse devices). However, in the extemporaneous narrative introduction to the poem, initial particles in English such as and, but, and because do occur.

Another reason to use pause as a line marker comes from an interview I did with Laura Tohe. In that interview, I inquired into the motivations for segmenting units into lines. She responded that lines were segmented by a “feeling,” a “sense of rhythm,” “where to make breaks or pauses,” and an “artistic sense.” The breaks in lines could be based on pauses “or on something more, a pause in time, reflection.” The line breaks in the orthographic version may represent places to pause, but they may also represent something else: a point of reflection or intensification. For purposes here, I follow the suggestions of Toelken & Scott 1981 and Benally 1994 concerning the segmenting of Navajo narratives into lines.

Finally, we can compare poetry as both a “visual” phenomenon and an “auditory” phenomenon. This is why I will maintain a classificatory stance here, with theoretical implications that regard all three examples as “versions.” I give primacy to no single example. I do give primacy to the “orality” of the poems. I do not wish to reify a single version as the Ur-text. Far too often this has been done in the documentation of oral performances as written text artifacts. Thus, we find a single performance standing for “the Navajo origin legend.” This article is not about “Navajo cat or stomp”; it is instead about three particular performances by Laura Tohe of her poem “Cat or stomp.”

CAT OR STOMP: THREE VERSIONS

Written version

Oral version one

Oral version two

COMPARISON OF THE THREE VERSIONS

Line structuring

I begin with a discussion of the structure of the oral performances and compare it to the structure of the written poem. The first thing to note is that the first oral performance is structured into three stanzas based on pause length. The stanzas do not correspond one-to-one with the three stanzas in the written version. The first stanza matches the introduction stanza of the written version. The second stanza begins with a restatement of the title of the poem and then describes the clothes “stomps” and “cats” wore. The third stanza matches the capitalization of “Every” in the written poem, the shift in perspective that returns to the first days of school when students arrive.

By my count there are 35 lines in this performance compared to either 23 or 31 lines in the written version (depending on how one counts lines). As noted above, the title of the poem, “Cat or stomp,” is also repeated at the beginning of the second stanza. Notice also the matching up of the slow production of the brands: Tony Lama / Nacona / Or Acme. This performance matches the written form of the poem. Each brand name is given its own line.

The second oral version has 25 lines, compared to 35 lines in the first oral version and 23 or 31 lines in the written version. In many ways this version, despite the number of lines, matches up less than the other two versions do. Take, for example, the segmentation of stanzas in the three versions. In versions one and two there are three stanzas, but in the third version there is one long stanza (granted that the stanzas do not exactly correspond in the first two versions). The third version also does not break the brand names into three distinct lines. Contrast the three appearances of this sequence: (written version) Tony Lama / Nacona / or Acme; (first oral version) Tony Lama / Nacona / or Acme; (second oral version) Tony Lama / Nacona / or Acme. In the third version, the three brands are rattled off together between breath pauses and one intonation contour. In the second version, each brand is accentuated with a breath pause and new intonation contour. This matches, following the ethnopoetic analysis of the written form, the format in the orthographic version. In this case, each brand is given its own “visual” line. These free-standing forms are reminiscent of “call” forms (Bauman 2004:60).

There are other places where lines in the oral versions do not correspond with the orthographic version. For example, compare these forms, the first from the written text and the second from the first oral performance: you wore new clothes Wrangler tight jeans / stitched on the side (Tohe 1999:6); and you wore new clothes / Wrangler tight jeans / stitched on the side (Tohe, performed 8 June 2001). Further, even if you wore tennis shoes it was clear which side / you were on (Tohe 1999:6), versus Even if you wore tennis shoes / It was clear which side you were on (Tohe, performed 8 June 2001). If we consider the written versions to be two lines, then the oral performance breaks one two-line set into three lines and divides the second two-line set differently. If we take the typographic conventions to represent multiple lines, then the oral performance breaks the utterances into different units. In the second example, an argument could be made that the breaking of lines in the written version creates a tension after side and then resolves the tension with you were on. In the oral performance the tension is created after shoes and is resolved with It was clear which side you were on. The former creates tension in a medial position of the utterance, while in the latter a full thought (clause) is the resolution of the tension.

In the first example, the written form, the indented material adds additional information regarding jeans, whether or not it is a line break or the continuation of a line. The oral performance is a bit more interesting. Each line in the oral performance is four syllables, and thus there is a nice parallelism of beats (i.e., syllables6

A scansion of the lines in classical metrical analysis reveals the first line to be a trochaic dimeter ′υ ′υ, and the second line scans also as a trochaic dimeter, while the final line differs with an opening trochee ′υ and then an iamb υ′. All three lines are, however, dimeters.

There are also examples in which multiple lines in the written version become a single line in the oral performance. These contrast with the previous examples where a single line is broken into multiple lines, either to resolve tension or to create rhythmic delivery. Notice that the process of merging multiple lines in the written version into a single line in the oral performance is less common than the reverse. This is clear from the line counts I gave above. Here is an example of multiple lines in the written version becoming a single line in the oral performance:

The typographic device ***** is often used in written poetry to indicate a stanza break that is disrupted because of a page change. Here I use it to indicate a stanza break in the oral performance. This contrasts with the other two versions.

If we count the written version as three lines, then the oral versions capture parts of three distinct lines within one line. In the second oral version, lines are in general longer. The first oral version has more lines and these lines tend to be shorter. The lines of the first oral version and second oral version do match up exactly at the beginning of this example. If we take the beginning of the written version to represent two lines, then the oral versions cross two lines, encapsulating gymnasium in the stanza-initial line and dislodging it from the next line. This line is a rather long line in oral performance when compared to the lengths of other lines in her oral performances. It is also a longer line when compared with the line length in Benally's (1994:604–5) narration of a Coyote story. In that story, there are a number of single word lines (

, ‘besides,’ ‘so,’ and ‘therefore’) as well as three-word lines (‘it is said’, representing the single Navajo word jiní).

The pause/line structure here also seems to be a more “natural” break, though, for it resolves a certain syntactic enjambment of the written version. It resolves the tension of the dangling old by giving it something to modify. Bringing loads of students then stands on its own in the oral performance, whereas in the written version it is conjoined with gymnasium. It appears that the oral versions are more “aural-friendly,” allowing the listener to process more complete units.

Such “dangling” or “hanging” syntactic units are found in other oral poetry. Tedlock (1983:50–51), for example, discusses “hanging” clauses in Zuni verbal art that he suspects are meant to increase suspense. Dunn (1989:397) points out “that one of the bases of poetry is the tension that exists in a text between sense units and performance units, between stichometry and strophometry.” Clearly “dangling” is just such an example. Thus it is important to look at the interaction between form and content, for this example comes at a crucial moment in this poem. The poem moves from a description of “cats” and “stomps” to recollections of new students (boys) arriving at the boarding school. In the first oral version, this section takes six lines. In the second oral version it takes five lines. In the written version it takes either four lines or six lines. In all three cases, though, the organization of the lines differs. In the written version, there is the tension of the “dangling” old. This is resolved in the two oral versions exactly the same way: A large line is constructed that encapsulates gymnasium and old in the same line.

The and their

Finally, there is the lexical difference between the and their reservation found within the versions.8

The alternation between the and their takes on a particularly English flavor when we compare it to Navajo. It is normally argued that Navajo does not have articles. Indeed, to specify a noun as ‘the (aforementioned)’ one adds an enclitic to the noun:

‘coyote’ and

‘the aforementioned coyote’ (see Sapir & Hoijer 1967:113). Possession is indicated by the prefix bi- ‘his, her, their’ on the noun:

‘their horse.’ In English both the possessive and the articles occur before the noun. In Navajo the possessive occurs as a prefix to the noun and the marker for ‘aforementioned’ is an enclitic.

THE CONTEXTS OF PERFORMANCE AND THE POEMS

Context visited: Requests and audience

The differences in the number of lines between the two oral versions can be connected, in some measure, to the format of the two performances. As I pointed out above, the first oral performance occurred outdoors at the Native American Music Festival. Tohe, who was an assistant professor at Arizona State University, had been asked by a student organization to perform her poetry at the festival. The setting was relatively informal. Also, she could not see the audience because of the spotlights on her.

At the readings in Window Rock, the setting was different. Unlike the standing crowd at Tsaile, the crowd at Window Rock was largely seated. Tohe had been asked to read at Window Rock by Luci Tapahonso, probably the most famous Navajo poet today, and by Monty Roessel. When I would explain what I was doing on the Navajo Nation to various people I met – that I was interested in Navajo poetry – the majority of people told me I should talk to Luci Tapahonso. Other poets were mentioned far less often. Rex Lee Jim, because he wrote in Navajo and performed on KTNN, was the next most frequently mentioned poet. Tapahonso has published a number of books of poetry. Monty Roessel is an award-winning photographer and the son of Robert and Ruth Roessel, important educators at Rough Rock Demonstration School for years.

The requests were from significantly different people. On the one hand, Tohe was invited by Tapahonso and Roessel, established Navajo intellectuals, and on the other hand, she was invited by an undergraduate student at Diné College. The performance at Window Rock, from the invitation through the performance, was more structured than the performance at Tsaile. Eight people read their work that night, all of whom have had a certain success in terms of publishing. Each poet was given roughly the same amount of time (about 15 minutes). The time had been discussed before the performances, and so each performer knew that he or she had only a limited time to perform. Furthermore, Tohe could see her audience. Included in this audience was Luci Tapahonso, who acted as master of ceremonies and as informal timekeeper.

The shortness of lines and the increased use of pauses in the first version may be a result of a relatively informal performance situation at Tsaile and Tohe's inability to see her audience. It may also be due to the fact that it was a relatively novel form of performance for her. The setting and audience of the two performances may have led to different rhetorical structures. In the case of Window Rock, the structuring seems a response to time constraints. In the other case, the structuring seems related to the novel situation, inability to see the audience, and the power relations between herself as a faculty member at a university and the undergraduate student who invited her to perform (Daniel, the Music Club president, who also acted as MC of the Music Club section).

The insertion of the title into the poem a second time in the first performance may also be connected with the setting of the performance. She seems to be slightly off balance at the beginning of the poem:

After this beginning, with several false starts and the reinsertion of the title, she slows the poem down considerably. She pauses more often than in the other oral version and creates more lines than the written version. She also creates a number of rhythmic sections (the list of brand names or the three lines with four beats).

It should also be clear that all three versions of the poem are framed in some measure by “writing” and by Tohe's book. The written version is in a book that clearly indexes Tohe's status as a published poet. Both oral performances reference her book and place this poem within that context as well: (oral version one) I wrote a book called No Parole Today / and some of you might be familiar with it; (oral version two) I have this book called No Parole Today. I will return to the introductory remarks in the next section; here, I want only to call attention to the undercurrent of writing and publishing.

Context revisited: Diné or Navajo

I now turn to another contrast between the three versions that should be clear from looking at the dedication of this poem. In both oral performances Tohe says Navajo Nation, but in the written version she has Diné Nation. I do not think this is a mistake, because it occurs in both oral versions; in addition, to call it a “mistake” would reify the written version as the “animating” version. Part of the point of this article is to cast that kind of reification of written forms into doubt.

I think the dedication frames the performance to follow (on framing see Goffman 1974). While the name “Diné” has grown in currency in public venues among Navajo (especially at Diné College), the tribe continues to be called “the Navajo Nation” in most public venues. For example, KTNN, in many of its promos, asserts it is “the voice of the Navajo Nation.” Furthermore, the tribal newspaper is still called The Navajo Times. Indeed, one of the primary public relations faces of Navajo-ness – iconic of and indexical of “tradition” – is “Miss Navajo.” When contests over “Diné” vs. “Navajo” occur, they may have political overtones. This was the case at Diné College in early 2001, when students argued that the initials for student organizations should be changed from NCC to DC. Also, all during the fall of 2000 Navajo people had been posting signs concerning the impending vote on Proposition 203, “English for the children.” Such phrases as Dooda prop 203 ‘no prop 203’ or Save Diné bizaad ‘Save the Navajo language’ appeared on a number of such signs. “Diné” had, to some degree, become politicized. Likewise, people driving from Flagstaff, Arizona onto the Navajo Nation in 2000 and 2001 saw that the sign “Welcome to the Navajo Nation” had been “corrected” to read “Welcome to the Diné Nation,” “Navajo” having been crossed out by hand and replaced by “Diné.”

“Diné” is often used by poets as a way of indexing an identity that contrasts with Navajo. “Diné” is a term of self-reference (or groupness) for these poets that faces outward, and the poems are meant to circulate in these books beyond the Navajo Nation. In fact, many of these books are sold at tourist sites such as Canyon De Chelly, the Grand Canyon, and Mesa Verde. Diné focuses outward, Navajo is the in-group term. Navajo is a less politicized and more intimate form than Diné.

Here is where framing comes into play. I use the term “play” on purpose, following Sherzer's discussion of it (2002:2–3) and focusing on what exactly is being framed (see Sherzer 2002:96–106). I take this poem to be an example of speech play, and as such it is “simultaneously humorous, serious and aesthetically pleasing” (Sherzer 2002:1). Like Basso's (1979) description of Western Apache imitations of “whitemen,” in which jokes about Anglo ineptitude with Apache norms is both humorous and dangerous, this poem is both funny for many Navajos and also evocative of the cruelty of the boarding school system. In both oral performances, laughter is heard when Tohe introduces the terms “cat” and “stomp.” She engages the audiences by asking either for a show of hands of former “cats and stomps” or by clapping. The audience responds by laughing and raising hands or clapping.

Notice also the shift she makes in pronominal usage, which also acts to engage and include the audience. In the first oral version, she changes “the” to “you” in the dedication: Cat or stomp / This for a / All of you former cats and stomps of the / Navajo Nation. In the second oral performance we have an interruption in the performance at just the point where Tohe has engaged the audience by asking them to self-identify as “cat” or “stomp.” An audience member, during the laughter, calls something out that Tohe cannot make out. She then addresses the audience member for clarification. Here is the relevant section:

The response that Tohe gets from one of the audience members is AIM (American Indian Movement). There is laughter after Tohe repeats AIM. This includes the audience member. Even though AIM was a deadly serious organization at times, here it is juxtaposed against young students in boarding schools who were “cats” or “stomps.” Because the audience has been engaged already, this potentially disruptive reference appears humorous to many (including the woman who made the insertion). But note that the insertion of AIM is meaningful because it draws into momentary relief the undercurrent of seriousness that is also a part of this poem and performance.

As stated above, this poem is not meant to be taken completely seriously. It is a form of speech play. Tohe engages the audience as co-participants in the performance. We see this again at the end of the poem, when the areas known as Chinle and Many Farms are mentioned. In both cases people respond to the place names. In the oral performance at the Native American Music Festival there was widespread cheering when Chinle and Many Farms are mentioned. Geographically speaking, I should add, both Chinle and Many Farms are closer to Tsaile than they are to Window Rock. At the performance in Window Rock there is soft laughter after Chinle and Many Farms have been mentioned, but in both cases there is a response. The responses are obviously conditioned by the type of event. The cheers came at a stylistically eclectic Music Festival that included rock and roll, country music, and heavy metal. The Window Rock performance was in a more formal, indoor setting, in the auditorium of the Navajo Nation museum.

As with much speech play, there is also an undercurrent of seriousness (Sherzer 2002). For many Navajos, boarding school was not a pleasant experience. Many of the poems in Tohe's book focus on such issues as language loss, homesickness, and racism. But there was something else going on too – something captured in this poem. People met people, including future spouses, at dances. And while the poem draws the hearer in through the performance style of Tohe, it also contrasts with the current situation on the reservation, where such boarding schools are now far less common.

Finally, it is aesthetically pleasing. People I spoke with after Tohe's performances commented on how “good” her poetry was and how “funny” it was. Some even stated that they had not expected to “enjoy a poetry reading.”9

Comments on the performances were usually collected directly after the performance by going up to various people and inquiring about the performance. This was usually done without a tape recorder, and so my notes often have short quotes such as these. I did also interview people days later who had been at a poetry reading. I prefer, in some measure, the off-the-cuff feel of the remarks recorded at the performance.

The poems in the oral performances are also embedded within a specific narrative, the narrative of Laura Tohe having gone to boarding school; they are localized within the boarding school matrix of many Native American experiences. She attended the Albuquerque Indian School, not the Phoenix or Santa Fe school. This is a way of creating connections, both specific and general. She indicates her own life story in relation to boarding schools in two ways in the performances. First, she does this is by simply stating that she had indeed attended the Albuquerque Indian School and prior to that a boarding school at Crystal, New Mexico. In both oral introductions, Tohe also locates herself in relation to Crystal, another way of locating herself within Navajo ethnogeography. The repeated uses of both the Albuquerque Indian School and Crystal localize her.

The Albuquerque Indian School has yet to have an adequate history written about it, but the story of Clarence Hawkins's escape from the school and his subsequent 300-mile journey back to the White Mountain Reservation is telling (see Greenfeld 2001). Suffice it to say that the school was not always the easiest place to live. Tohe says this about the school in oral performance version two: Uh and for me that's what Indian Schools were all about / Was was assimilation / And it was also the taking away of our language.

The second way that she engages the audience in her own narrative, her own story, is in her Where's Waldo picture offer. At every poetry reading where I have seen her perform, she has made this offer. On the cover of her book is a collage of pictures of students at the Albuquerque Indian School. One of the pictures is hers. If you can guess which picture is hers, she will give you five dollars. This rarely happens. However, the cover photo validates her claim that she was there: essentially, saying “I have the picture to prove it.” The poems about the boarding school experiences are more than that. Her cover picture validates them as poems about Tohe's boarding school experience. In other poems in the collection she makes this quite clear. In one poem concerning the arrogant mispronouncing of Navajo personal names, Tohe is careful to include her name in the list of names so mangled:

In a performance of this poem at Tsaile to a collection of Navajo students at Diné College and Navajo faculty, I could see Navajo faculty members and older “returning” students nodding their heads in agreement as Tohe listed the ways that Navajo names had been mispronounced. Note that the visual form of this poem may reproduce the very mangling of pronunciation that Tohe is writing against; the sounds of the Navajo words become salient in the oral performance of this poem.

The pictures on the cover of Tohe's book show students in thick glasses and now out-of-fashion haircuts and clothes, and are – on the whole – less than flattering. Instead, they may remind Navajos who attended boarding school of an earlier time (Ah I invite people to look at this / cover and see people in there you might recognize from Indian School). For younger Navajo they are “old photos” of a time now largely gone, but a time that still circulates in stories and poems like Tohe's work, or Blackhorse Mitchell's book Miracle Hill (1967). There is a nostalgia to this book, evoked through humor. But there is also a cautionary tale here. That, I believe, is the significance of the twin functions (humor and seriousness) of speech play in her poems.

The written version of the poem also includes biography. Note that biography is important in both the oral and the written versions of this poem. In No Parole Today, Tohe includes an autobiographical introduction in the form of a letter to General Richard Pratt.10

Pratt began the Carlisle Institute, Carlisle, Pennsylvania as a progressive way to “civilize” Native Americans. Many Native Americans were taken from their homes to a far different climate where they suffered and died. Many students attempted to escape. For a brief overview of this project, see Iverson 1998.

In the late 1950s I began school on the largest reservation in the United States, the Diné reservation. Although outsiders give us the name Navajo, we call ourselves Diné, The People. I prefer to call myself the name my ancestor gave us because I am trying to de-colonize myself. When I began school, the Principal placed me in first grade because I was one of the few students who could speak English, though Diné bizaad was my mother tongue. All my classmates were Diné and most of them spoke little or no English.

On the first day of school we found ourselves behind small wooden desks looking at the teacher who acted on behalf of your assimilation policies. Besides teaching us to read, write, and count in English, she was instructed to wipe out Diné bizaad through shame and punishment. We still bear painful memories for speaking our native language in school and that legacy is partly why many indigenous people don't know their ancestral language.

I skipped Beginners class and went straight to first grade. My grandmother called me hwiní'yu, being useful, because I translated for my classmates. I felt helplessness when English sounds couldn't form into language that could save them. If I didn't help them, I felt I would be a participant in their punishment. We learned quickly that if we didn't want to be punished and shamed in front of our classmates we had best speak our language far from the ears of the teachers, or stop speaking; most chose the latter. (Tohe 1999:x–xi)

Thus, in both the oral performances and the written version Tohe situates herself as a participant in the boarding school. The poem is embedded within a story, her autobiography. I think it is important to recall the very narrative quality of the poem “Cat or stomp.” The poem recounts a story. It has a beginning, The first few days back; a turning point, Every year the smoking Greyhound buses; and a conclusion, To dance with him that night.

The performances are situated in public venues; they are shared. Cruikshank 1998, among others, has stressed the ways that such public performances aimed at both native and non-native audiences create differing contexts. Thus, among Northern Athabaskan people verbal performances are both aesthetically pleasing and claims to place and tradition. The claims to place may at times be subtle and missed by non-native audiences, but to the native audiences they are clear assertions. This has to do with Northern Athabaskan conceptions of knowledge and what are and are not considered legitimate forms of knowledge (see Cruikshank 1998; see also Rushforth 1992, 1994). Such multi-voiced or polyphonic performances can also be related to Australian Aboriginal art; where Myers 1991, 1994 reports that although the audiences were at times decidedly non-native, the communicative function – the register – was concerned with assertions of legitimacy and placed-ness via “the Dreaming.” – even if, to a large degree, such assertions were missed because of a need to fit Australian Aboriginal acrylic painting into a frame of reference concerned with Western notions of “art” (Myers 1991, 1994, 2002).

What is occurring with Tohe's three performances (one written and two oral) is similar in practice. Tohe is making certain assertions that may be missed by non-native audiences in one context but appreciated in other contexts. The written version, for example, makes a stronger political statement vis-à-vis Anglo–Navajo relations than do the oral performances. She pointedly articulates or creates a “voice” of anger at Richard Pratt and the politics of assimilation. Here we expect the politicized “Diné” form, not “Navajo.” We are not let down. In other contexts, the oral contexts, contexts that are more Navajo, such a form may be seen as too explicit, too obvious. The subtlety that Anglos may believe they are gleaning from such a performance may be, instead, a lack of awareness of the stock of knowledge or of a misrecognition of a people as expressed and circulated through individual performances (the boarding school experience, for example). The performances, written or oral, play to the audiences, articulating a sense of “Navajoness.” They are, however, also (mis)interpreted by the audience (Fabian 2001:33–52).

When Navajo poets perform before audiences – audiences as diverse as the program Line break on National Public Radio, or poetry readings at a person's house, or poetry readings at the Native American Music Festival – many invariably introduce themselves via their clan relations in Navajo. This is true of both native Navajo speakers and Navajos who do not speak the language; it is a formula many Navajos learn (Slate 1993, House 2002). To Navajo people this locates people within an existing clan structure, stating what relation they may or may not have with particular audience members. It is a specific kind of assertion or reckoning of Navajoness and resonates in a specific way for many Navajos. Laura Tohe, for example, introduces herself at the two performances by her clan relations. She tells the audience, in Navajo, that her mother's clan is Tsé Nahabiłnii ‘Sleepy Rock People’ and her father's clan is Tó Dich'íi'nii ‘Bitter Water People’. Such introductions matter in making Laura Tohe locatable within Navajo clan reckoning.

For non-Navajo audience members, however, it was a display of Navajo as Other. Thus, such introductions also create an Other for non-Navajo audiences, a different kind of Navajoness. The language of the introduction, even if it is formulaic and to Navajo speakers because it is formulaic, is “different,” and the idea of clans is also “different” from the stock of knowledge of non-Navajo audiences but does fit a pattern of Navajo as Other. The introductions, while invariably in Navajo, are then translated or explained in English. Thus, one finds statements like the following in the transcripts from performances (the first is from Tohe): I just introduced my mother's clan or that's the traditional way Navajos greet each other. These are metalinguistic cues (Silverstein 1985, 1996; Collins 1987) that frame a stretch of talk in Navajo as “traditional,” as “Navajo,” and in so doing index the position of the speaking subject – creating, again, something we might term “Navajoness.”

But the key, thinking back to Cruikshank, is that Navajoness is not identical across audience members. It is not an immutable feature. It is, rather, co-constructed variously among varied subjects. Non-Navajo audience members may appreciate certain cues as indexes of Navajoness in rather different ways than Navajos might. Navajoness is not just context-dependent (in the crude sense), but is rather co-constructed simultaneously in differing ways by speaker/writer and audience. On the one hand, Navajoness is interpreted as “identity” by Navajo people; on the other hand, Navajoness is understood as “difference” by many non-Navajo audience members (this distinction is based on the work of Jameson 1979). These displays, through the formulaic use of clan relations, for example, or the use of the Navajo language, are what Silverstein (2003:538) terms “emblematic identity displays.”

CONCLUSION: ON NARRATIVES OF NAVAJONESS

When Laura Tohe performs her poetry, whether it is an oral or written performance, she is using language creatively and artistically. She is also playing out a tension between the oral traditions of Navajo expressive genres and her own unique creativity. For example, Tohe's use of formulaic clan introductions clearly taps into a larger recognized speech genre among Navajos. Her poetry about boarding schools also taps into an experience common to many Navajos of certain generations. Likewise, her use of place names in the poems discussed above connects them to Navajo traditions that place a premium on the grounding of narratives within Navajo ethnogeography (Webster 2004, Kelley & Francis 2005).

However, we cannot completely predict the form of this poem based on Navajo oral tradition. I have tried, where applicable, to note connections to Navajo oral traditions. However, we also need to approach this narrative poem as a unique creation by an individual. There are influences from Navajo oral tradition to be found in it, but there are expressions of individuality as well. Furthermore, the poem is meant to be performed, and as such it is constantly remodeled and reshaped in relationship to the contexts of the performance, but it is also tied to Tohe's aesthetic sensibilities. This remaking and refashioning is a hallmark of certain genres of Navajo verbal art (Coyote stories, for example). By focusing on the individual creator, we better understand the unique creativity of the linguistic individual (Johnstone 1996). It allows us to understand and appreciate how Laura Tohe uses English to create, assert, and imagine Navajoness.

I am reminded of Samuels's (2004:149–76) discussion of Boe Titla's “idiosyncratic authenticity,” or the way the song “Mathilda” became “an artifact of social memory in the community, resonant and saturated with experiences and knowledge of the people who have heard it and sung it through the years” (Samuels 2004:136). The differences we find in Laura Tohe's poem performances reflect the differences in audiences as well in her own life story. Tohe is not just performing a poem about boarding school romances, she is also – as she makes clear through her “where's Waldo” introduction – sharing something of her own individual life-story – a life story grounded in clan relations, the Albuquerque Indian School, and Crystal, New Mexico . The performances of this poem speak, then, to a myriad of felt connections. If you attended boarding school in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, you too may recall the distinction between “cat” or “stomp.” Or, as the audience member inserts, you may remember the politics of the 1970s, when the Navajo AIM leader Larray Cacuse was killed in Gallup, New Mexico and a memorial march was given in his honor through the streets of Gallup. This moment was memorialized in a poem by fellow Navajo Nia Francisco: horses that paraded during l. cacuse's memorial march (Francisco 1977:349). Included in this poem is Francisco's footnote: “L. Cacuse: A Navajo murdered in Gallup, New Mexico, in 1971” (Francisco 1977: 349). AIM is not in Laura Tohe's poem about cats and stomps. But, as an interactional performance, it can be. The politics of the 1970s and boarding school life can be brought forward by this poem. The feelingful work of language, the creative use of language, can and does bring such images and remembrances into momentary focus. That is the felt power of language, evoked through the creative and individual use of language.

Finally, in these performances (oral and written), much of the identity work, the evocation of history, is done by Tohe through the localizing of the poem. In Tohe's performance we see that when poetry is a kind of storytelling, when it is emotionally expressive uses of language, and when it is shared, felt attachments to aesthetic forms, nostalgia for a prior here and now can be evoked. It is in those moments that we glimpse a sense of “we-ness,” of Navajoness. Contrary to House 2002, who describes “narratives of Navajoness” but does not focus on the poetics of actual discourse, this article has looked to individual and contextualized performances of narratives of Navajoness and the poetics of those performances to understand how that sense of we-ness is achieved. Narratives of Navajoness are not abstractions; rather, they are localized moments of language in use. To appreciate the identity work of narratives of Navajoness, we must first appreciate the performances as the creative achievements of individuals. We must also appreciate them as narratives that emerge within meaningful contexts. Finally, we must appreciate the felt connections, the feelingful iconicity, that such narratives can and do evoke. In looking closely at individual voices, we can learn a great deal about the concerns of peoples within communities, about identity as a kind of storytelling, and about how language use can frame contexts or become context-creating.