INTRODUCTION

Gender-biased infestation has been repeatedly reported for a variety of parasites exploiting vertebrate hosts (e.g., Poulin, Reference Poulin1996; Zuk and McKean, Reference Zuk and McKean1996; Schalk and Forbes, Reference Schalk and Forbes1996; McCurdy, Reference McCurdy1998; Morales-Montor et al. Reference Morales-Montor, Chavarria, De León, Del Castillo, Escobedo, Sánchez, Vargas, Hernández-Flores, Romo-González and Larralde2004; Krasnov et al. Reference Krasnov, Morand, Hawlena, Khokhlova and Shenbrot2005). In the majority of mammalian hosts, parasite abundance (e.g., Rossin and Malizia, Reference Rossin and Malizia2002), prevalence (Soliman et al. Reference Soliman, Marzouk, Main and Montasser2001) and/or species richness (Morand et al. Reference Morand, De Bellocq, Stanko and Miklisová2004) are often higher in males compared with females.

Two main hypotheses explaining male-biased parasitism relate infestation difference between males and females to gender differences in either mobility or hormonal status. Increased mobility in males may lead to a greater chance of encounter with parasites as well as an increased frequency of intra- and interspecific contacts between hosts that, in turn, facilitates transmission of parasites (e.g., Brown et al. Reference Brown, Macdonald, Tew and Todd1994). A difference in hormonal status may lead to a difference in anti-parasitic defence ability due to the immunosuppressive effect of androgens (Zuk, Reference Zuk1996; Zuk and McKean, Reference Zuk and McKean1996; Folstad and Karter, Reference Folstad and Karter1992; but see Devevey et al. Reference Devevey, Chapuisat and Christe2009). It has recently been shown that these two causes of gender biased parasitism are not alternative but rather interconnected (Grear et al. Reference Grear, Perkins and Hudson2009).

However, the occurrence and the extent of gender-biased parasitism vary among hosts and parasites (Poulin, Reference Poulin1996; Schalk and Forbes, Reference Schalk and Forbes1996; Moore and Wilson, Reference Moore and Wilson2002; Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Buchanan and Evans2004). For example, gender differences in parasite infestation have not been found in some host-parasite associations (Gummer et al. Reference Gummer, Forbes, Bender and Barclay1997; Wirsing et al. Reference Wirsing, Azevedo, Lariviere and Murray2007). Furthermore, gender differences in infestation are not always male-biased. Indeed, female-biased parasitism was found to be a rule in some hosts (e.g., bats; Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Dick and Dittmar2008; Krichbaum et al. Reference Krichbaum, Perkins and Gannon2009) and has also been observed in host taxa which are usually characterized by male-biased parasitism (e.g., rodents; Krasnov et al. Reference Krasnov, Morand, Hawlena, Khokhlova and Shenbrot2005). In addition, gender-biased parasitism among mammals of the same species from the same population may sharply differ among different parasite taxa. For example, male Cape ground squirrels (Xerus inauris), were found to be infested by 3 times as many ectoparasites as females, whereas females of this species harboured almost 3 times as many endoparasites as males (Hillegass et al. Reference Hillegass, Waterman and Roth2008).

The extent, occurrence and direction of gender-biased parasitism may vary not only among hosts or parasites or parasite-host associations, but also in the same parasite-host association across locations or time-periods. For example, Krasnov et al. (Reference Krasnov, Morand, Hawlena, Khokhlova and Shenbrot2005) found that gender differences in the pattern of flea parasitism of rodent hosts from the Negev desert were manifested mainly during the reproductive period. Matthee et al. (Reference Matthee, McGeoch and Krasnov2010) studied ticks, mites, fleas and lice exploiting a rodent Rhabdomys pumilio in several localities in South Africa and found that the occurrence and extent of gender-biased infestation varied within a parasite species among localities, from being male-biased to being female-biased via being absent. Although the general trend in the majority of these parasites was male bias, the reasons behind substantial spatial variation in gender differences remained unexplored.

Here, we asked what are the factors that affect the manifestation and extent of gender bias in host infestation by different parasites across localities. A gender-biased pattern of parasite infestation has been shown to be a complicated phenomenon that cannot be explained by a single mechanism but rather involves several different mechanisms (Morand et al. Reference Morand, De Bellocq, Stanko and Miklisová2004; Krasnov et al. Reference Krasnov, Morand, Hawlena, Khokhlova and Shenbrot2005; Grear et al. Reference Grear, Perkins and Hudson2009). We hypothesized that these mechanisms are associated with processes acting in both host populations and parasite communities and may be mediated by the environment. To test this hypothesis, we studied the effect of parasite-, host- and environment-related factors on the magnitude of gender-biased parasitism in a rodent Rhabdomys pumilio harbouring ixodid ticks, gamasid mites, lice and fleas. Our predictions were as follows. (1) Male bias in parasite infestation will increase with an increase of mean abundance and/or species richness of the entire parasite community. This is because multiple parasite challenges cause immunodepression in a host (Bush and Holmes, Reference Bush and Holmes1986), so a general increase in parasite pressure (in terms of abundance and/or species richness) may lead to further suppression of immune function in weakly immunocompetent individuals (i.e., males). Indeed, interspecific interactions between ectoparasites in infracommunities appeared to be facilitative (Krasnov et al. Reference Krasnov, Stanko and Morand2006 a, Reference Krasnov, Stanko, Khokhlova, Mosansky, Shenbrot, Hawlena and Morandb, Reference Krasnov, Matthee, Lareschi, Koraalo-Vinarskaya and Vinarski2010). (2) Male bias in infestation (a) will increase with an increase in the proportion of reproductive males without concomitant increase of reproductive females; (b) will decrease with an increase in the proportion of reproductive females without concomitant increase of reproductive males and with an increase in host density; and (c) will not change with a simultaneous increase in the proportion of reproductive individuals of both genders. This is because increased mobility of rodents will likely increase the frequency of between-individual contacts and thus will facilitate parasite transmission (Tompkins and Begon, Reference Tompkins and Begon1999). An increase in mobility may be characteristic either for reproductive males (as in the majority of small mammals; Edelman and Koprowski, Reference Edelman and Koprowski2006; Lambin, Reference Lambin1997) or for reproductive females (as in R. pumilio in some parts of its geographical range; Schradin and Pillay, Reference Schradin and Pillay2006) or for both genders independent of reproductive status (at high density; Brandt, Reference Brandt, Stenseth and Lidicker1992 and references therein). (3) Gender-biased parasitism will be affected by environmental factors (air temperature and relative humidity) mainly in ectoparasite taxa that spend more time off-host (e.g., ixodid ticks) than in ectoparasites with tighter links to a host body (e.g., lice and fleas). Precise predictions about the effect of an environmental factor on the magnitude and direction of gender-biased parasitism are difficult, if at all possible because different ectoparasite species (even closely-related) respond differently to environmental factors (Marshall, Reference Marshall1981; Krasnov et al. Reference Krasnov, Khokhlova, Fielden and Burdelova2001 a, Reference Krasnov, Khokhlova, Fielden and Burdelovab, Reference Krasnov, Khokhlova, Fielden and Burdelova2002 a, Reference Krasnov, Khokhlova, Fielden and Burdelovab).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Field data collection

We captured striped mice, Rhabdomys pumilio, in 2003–2004 in 9 localities in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. These localities included 5 pristine lowland Fynbos/Renosterveld regions and 4 remnant fragments that are surrounded by or border agricultural areas (see details in Matthee et al. Reference Matthee, Horak, Beaucournu, Durden, Ueckermann and McGeoch2007; Matthee and Krasnov, Reference Matthee and Krasnov2009). Sampling was conducted during austral spring and summer (September-December) with 5 of 9 localities sampled in November. This period falls within the main breeding season for R. pumilio. Rodents were captured using Sherman-type live traps (90–180 traps per locality) baited with peanut butter and oats during 3–12 days in each locality. Adult individuals with a body mass of more than 40 g were euthanized with Fluothane, placed in individual pre-marked plastic bags and transferred to a laboratory where each animal was systematically examined under a stereoscopic microscope. All ectoparasites were removed using forceps, counted and identified to species level.

Each rodent was characterized as either reproductively active or reproductively inactive. A male was considered reproductively active if its testes were scrotal, whereas a female was considered reproductively active if it had a perforated vagina or was pregnant. For each locality, data on minimal and maximal daily temperature, the amount of rainfall and relative humidity were obtained from the nearest weather station. The respective weather stations are managed and maintained by the Agricultural Research Council of South Africa.

Data analysis

For each locality and for male and female hosts separately, we calculated mean abundance, variance of abundance and prevalence (fraction of infested individuals) of (a) each parasite species that occur in at least 6 localities and (b) all parasites belonging to a particular higher taxon (ticks, mites and fleas; lice were represented by a single species). In addition, we calculated mean species richness of all parasites and its variance, as well as those of ticks, mites and fleas separately for male and female hosts within a locality.

The extent of gender-biased parasitism within a locality was evaluated via differences between male and female hosts in prevalence, abundance and species richness of parasites. Differences between male and female hosts in prevalence of infestation were calculated as the odds ratio of proportions of infested male and female hosts for each parasite species or higher taxon (ticks, mites and fleas) within each locality. Differences between males and females in mean abundance and species richness of parasites were calculated as standardized mean differences (SMD) between male and female hosts in abundance of each parasite species or higher taxon and species richness of all parasites or parasites belonging to a higher taxon within a locality. SMD is the difference between 2 normalized means, i.e. the mean values divided by an estimate of the within-group standard deviation. Odds ratios greater than 1 and positive values of SMD indicate male-biased infestation in terms of abundance and prevalence of parasites, respectively, whereas odds ratios less than 1 and negative values of SMD indicate female-biased infesation.

To characterize localities, we calculated parasite-related (mean abundance, mean species richness and total species richness of all parasites), host-related (rodent density and proportion of reproductive males and females both separately and together) and environment-related (mean daily maximal and minimal temperatures, rainfall and relative humidity) groups of variables for each locality. Because of within-group correlation between some of these variables (r=−0·83–0·63, P<0·05 for all), we substituted them with the scores calculated from within-group principal component analyses of these 3 variables after ln+1- or arcsine-transformations. These analyses resulted in 1 component variable describing parasite communities (parasite factor), 2 component variables describing host population (host factors) and 2 component variables describing environment (environmental factors). Parasite factor (PF) accounted for 72·9% of the variance and its eigenvalue was 2·2. This factor correlated positively with mean parasite abundance (r=0·82) and correlated negatively with mean and total parasite species richness (r=−0·87 and r=−0·86, respectively). Host factors (HF1 and HF2) explained 64·2% and 32·8% of the variance, respectively, and their eigenvalues were 1·9 and 1·0 respectively. HF1 correlated positively with rodent density (r=0·97) and proportion of reproductively active females (r=0·98), whereas HF2 correlated positively with the proportion of reproductively active males (r=0·97). Environmental factors (EF1 and EF2) accounted for 63·2% and 27·3% of the variance, respectively, and their eigenvalues were 2·6 and 1·1, respectively. EF1 correlated positively with mean precipitation (r=0·91) and correlated negatively with the maximal daily air temperature (r=−0·96), whereas EF2 correlated negatively with relative humidity (r=−0·78).

To test for the effect of parasite-related, host-related and environment-related factors on the extent of gender difference in parasite abundance, prevalence and species richness, we applied generalized linear models (GLM) with normal distribution and identity-link function, and searched for the best model using the Akaike's Information Criterion. This was done for each parasite species separately as well as for fleas, mites and ticks separately. Dependent variables in these models were (a) ln+1-transformed standardized mean differences between male and female hosts either in parasite abundance or species richness and (b) ln-transformed odds ratio of proportions of infested male and female hosts. The exploratory terms were parasite-, host- and environment-related factors extracted from principal component analyses described above. Then we further investigated the best significant models using stepwise multiple regressions (forward procedure).

RESULTS

In total, we captured and examined 366 R. pumilio individuals (217 males and 149 females). From these individuals, we collected more than 25 000 individual parasites belonging to 32 species (see Matthee et al. Reference Matthee, Horak, Beaucournu, Durden, Ueckermann and McGeoch2007 for details). Among these parasites, 2 fleas (Chiastopsylla rossi and Listropsylla agrippinae), 1 louse (Polyplax arvicanthis), 3 mites (Androlaelaps dasymys, Androlaelaps fahrenholzi and Laelaps giganteus), and 3 ticks (Haemaphysalis elliptica, Ixodes bakeri and Rhipicephalus gertrudae) were found in at least 6 localities.

The odds ratio of prevalence of infestation of male and female hosts by the same parasite varied among localities from being female-biased to being male-biased (Table 1). The same was true for SMD in parasite abundance and species richness (Table 1). The only exception was mean abundance of a louse, P. arvicanthis. It ranged from being equal on males and females to being higher on males.

Table 1. Mean and range of male/female odds ratio in prevalence (ORP) and standardized mean male/female differences in abundance and species richness (SMDA and SMDSR, respectively) of parasite species and higher taxa across nine localities

The best models explaining the variance in the extent of gender difference in parasite abundance, prevalence or species richness due to effect of parasite-related, host-related and environment-related factors are presented in Table 2. A composite variable describing the parasite community in a locality (PF) was found to affect gender difference in abundance of both fleas and a louse, as well as in total abundance of fleas. This variable also affected gender differences in prevalence of a flea, C. rossi, a tick, R. gertrudae and in total flea prevalence and species richness. Whenever the effect of a parasite-related composite variable was found to be significant, it was negative (see illustrative examples with abundance of a louse and prevalence of a flea in Fig. 1). In other words, the magnitude of male-female difference in parasite abundance, prevalence or species richness decreased with an increase in mean parasite abundance and a decrease in mean and total parasite species richness.

Fig. 1. Relationships between a composite variable describing parasite community in a locality (PF) and (a) standardized difference between male and female Rhabdomys pumilio in abundance of a louse, Polyplax arvicanthis and (b) odds ratio of proportion of male and female R. pumilio infested with a flea, Chiastopsylla rossi.

Table 2. The best models explaining variance in the extent of gender difference in mean abundance (MA), prevalence (P) and species richness (SR) of parasites as affected by parasite- (PF), host- (HF1 and HF2) and environment- (EF1 and EF2) related factors and summary of multiple regressions according to these best models

(AIC, Akaike's Information Criterion; LR, likelihood ratio. Only significant standardized coefficients are shown. ***P<0·001, **P<0·01, *P<0·05, ns, not significant.)

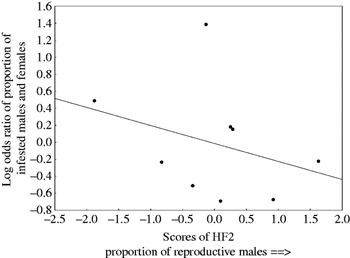

A composite variable describing host density and proportion of reproductively active females (HF1) affected gender difference in abundance of a louse, P. arvicanthis and a tick, I. bakeri and in total tick abundance and species richness. In all cases when this effect was significant, it was positive, i.e. the magnitude of gender difference in infestation increased with an increase in rodent density and/or proportion of reproductive females (see illustrative example with abundance of a tick, I. bakeri in Fig. 2). The effect of the second host-related composite variable (HF2) was significant for gender difference in abundance in 2 ticks (H. elliptica and I. bakeri) and prevalence of a flea, C. rossi. In addition, HF2 significantly influenced gender difference in total tick abundance and total mite prevalence. Except for abundance of I. bakeri, the effect of HF2 on male/female difference in infestation was negative, i.e. the extent of gender difference in infestation decreased with an increase in the proportion of reproductively active males (see illustrative example with prevalence of mites in Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Relationships between standardized difference between male and female Rhabdomys pumilio in abundance of a tick, Ixodes bakeri and a composite variable correlating with host density and proportion of reproductive female hosts in a locality (HF1).

Fig. 3. Relationships between odds ratio of proportion of male and female Rhabdomys pumilio infested with mites and a composite variable correlating with proportion of reproductive male hosts in a locality (HF2).

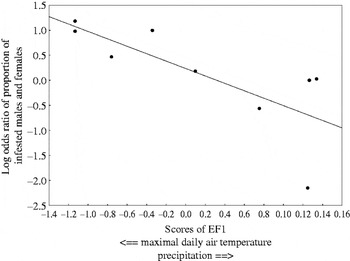

The environmental effect on gender difference in infestation was reflected by a significant decrease in the magnitude of male/female difference in abundance or prevalence of a mite, A. dasymys, a flea, C. rossi and 2 ticks (H. elliptica and R. gertrudae) with an increase in mean precipitation and a decrease of maximal daily air temperature (EF1; see illustrative example with a tick, H. elliptica in Fig. 4). A similar pattern was found for total abundance and species richness of ticks and prevalence of mites. Finally, a significant effect of a composite variable reflecting among-locality variation in relative humidity was found only for gender differences in mean abundance of a tick, I. bakeri (Table 2).

Fig. 4. Relationships between odds ratio of proportion of male and female Rhabdomys pumilio infested with a tick, Haemaphysalis elliptica and a composite variable correlating with maximal daily air temperature and precipitation in a locality (EF1).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrated that spatial variation in gender differences in parasite infestation was affected by parasite-, host- and environmental factors. The set of factors affecting gender differences in infestation differed among higher taxa of ectoparasites. Gender differences in infestation by fleas and lice were affected mainly by parasite-related factors, whereas gender differences in infestation by ticks and, in part, by mites were affected mainly by host-related and environmental factors. Spatial variation in most measures of gender difference in mite infestation remained unexplained. A summary of the effects of parasite-related, host-related and environment-related variables on male-biased infestation of R. pumilio by ectoparasites found in our study is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of the effects of parasite-related, host-related and environment-related variables on male-biased infestation of Rhabdomys pumilio by ectoparasites

Parasite community and gender-biased infestation

The combined effect of parasite-related variables on gender difference in infestation measure was consistently negative. This suggests that male-biased parasitism was characteristic mainly for host populations exploited by species-rich, but individual-scarce, parasite communities. Stronger male-biased infestation in species-rich parasite communities may be caused by at least 2 inter-related processes. First, parasites are able to down-modulate the intensity and efficiency of host immune responses (Baron and Weintraub, Reference Baron and Weintraub1987; Wikel and Bergman, Reference Wikel and Bergman1997; Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Friberg, Bolch, Lowe, Ralli, Harris, Behnke and Bradley2009). Parasites differ in their modulatory effect on the host immune system, so that a key role in the suppression of host defence is played by a subset of immunomodulatory species rather than by all parasites (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Friberg, Bolch, Lowe, Ralli, Harris, Behnke and Bradley2009). The probability of a host being infested by these immunomodulators is obviously higher if a parasite community is species rich. Second, lower defensibility under multiple parasite challenges may be associated not with an immunosuppressive effect of parasites per se but rather with a high energetic cost of the immune system. A host subjected to attacks from multiple parasite species is forced to give up its defence and to surrender (Jokela et al. Reference Jokela, Schmid-Hempel and Rigby2000). The diversity of parasite attacks may be more critical for males than for females because the former invest less in immune defence and suffer from the negative effect of androgens.

Taking the above into account, a negative relationship between the magnitude of male-biased parasitism and general abundance of parasites seems counter-intuitive. On the one hand, the effect of multiple attacks from conspecific parasites on the host immune system should be similar to the effect of multiple attacks from heterospecific parasites, (see Khokhlova et al. Reference Khokhlova, Spinu, Krasnov and Degen2004). On the other hand, a decrease in male/female difference may occur if the attacks of many conspecific parasites result in increased mortality of heavily infested individuals (males). Male-biased mortality due to parasite pressure have been reported for a number of host and parasite taxa (e.g., Irschick et al. Reference Irschick, Gentry, Herrel and Vanhooydonck2006; Nico de Bruyn et al. Reference Nico de Bruyn, Bastos, Eadie, Tosh and Bester2008; see also Moore and Wilson, Reference Moore and Wilson2002). In addition, the number of individual parasites is almost always higher than the number of parasite species, so that an abundant but species-poor parasite community may exert higher pressure on hosts than a scarce but species-rich parasite community.

Host population and gender-biased infestation

Our predictions about the effect of host density and proportions of reproductive males and females were not supported by the results. Whenever gender difference in infestation was significantly influenced by host-related variables, the magnitude of male bias increased with an increase of host density and the proportion of reproductive females, and decreased with an increase in proportion of reproductive males (except for a tick, I. bakeri). The reason behind the positive relationship between male infestation bias and host density may be the increased male dispersal in a growing population of small mammals (Greenwood, Reference Greenwood1980; Brandt, 1992; Cockburn, 1992; Gauffre et al. Reference Gauffre, Petit, Brodier, Bretagnolle and Cosson2009) including R. pumilio (Schradin and Pillay, Reference Schradin and Pillay2006). Obviously, dispersing individuals have higher chances to encounter ectoparasites than resident hosts. For example, they may more often come upon a questing tick and/or visit burrows of other rodents and be attacked by fleas and mites.

Proportions of reproductively active males and females among localities were not correlated (r=0·24; these variables were included in 2 orthogonal principal components; see Materials and Methods section). The reasons for this asynchrony are out of the scope of our study, but can be related to the flexible schedules of sexual maturity and reproductive activity in this species that depend on a variety of environmental and social factors (Schradin et al. Reference Schradin, Schneider and Yuen2009 a). Contrary to our expectation, male-biased parasitism was more expressed in populations with a high proportion of reproductive females. This may be associated with increased foraging activity of females during the breeding period (Schradin, Reference Schradin2005; Schradin and Pillay, Reference Schradin and Pillay2006) that not only compensates for energetic costs of pregnancy and lactation but also may allow the mounting of a stronger immune response (Houston et al. Reference Houston, McNamara, Barta and Klasing2007). An increase in immunocompetence of reproductive females due to increased food consumption may thus result in strong male-biased infestation.

Surprisingly, the extent of male-biased infestation was lower in localities with a higher proportion of reproductively active males contradicting thus not only our prediction, but also one of the most commonly accepted explanations of male-biased parasitism (e.g., Hughes and Randolph, Reference Hughes and Randolph2001). This result may be associated with social flexibility of R. pumilio (Schradin, Reference Schradin2004, Reference Schradin2005, Reference Schradin2008; Schradin et al. Reference Schradin, Scantlebury, Pillay and König2009 b). Male R. pumilio follow 1 of 3 reproductive tactics, namely group-living philopatry, group-living amicable territorial breeding or solitary living roaming. Testosterone levels were found to differ, being the highest in solitary roamers and the lowest in 2 remaining categories (Schradin et al. Reference Schradin, Scantlebury, Pillay and König2009 b). In other words, many reproductive males are neither highly mobile (Schradin, Reference Schradin2004) nor have high testosterone levels. This presumably decreases the probability of philopatrics and territorial breeders to be attacked and/or successfully exploited by, for example, ticks. As a result, a population with a high proportion of reproductively active males may demonstrate weak, if any, male bias in parasite infestation.

The male/female differences in infestation by the tick I. bakeri increased with host density and/or proportion of reproductive females and males, the latter being an exception. In contrast with many other ixodid ticks, all stages of I. bakeri feed on rodents (Walker et al. 1991). In addition, there were more I. bakeri nymphs on R. pumilio (20·81%) compared to those of other tick species (4·76–6·79%; Matthee et al. Reference Matthee, Horak, Beaucournu, Durden, Ueckermann and McGeoch2007). Larger life stages such as adults and nymphs are more likely to be removed by self- or allo-grooming which may result in fewer ticks on females and thus explain male bias.

Environment and gender-biased infestation

The main environmental pattern in gender-related parasitism was that stronger male bias was characteristic for drier and warmer localities, i.e. in xeric rather than mesic habitats. Social structure of R. pumilio populations varies from solitary living in moister habitats to communal living in drier habitats (Schradin and Pillay, Reference Schradin and Pillay2004, Reference Schradin and Pillay2005). Communal-living R. pumilio do not demonstrate gender-associated differences in home-range size (Schradin, Reference Schradin2005; Schradin and Pillay, Reference Schradin and Pillay2004, Reference Schradin and Pillay2005), but they demonstrate gender-associated difference in behaviour, with males being the main initiators of the between-group agonistic interactions (Schradin and Pillay, Reference Schradin and Pillay2004). In R. pumilio from more mesic areas, both genders demonstrate aggressive behaviour that increases during the reproductive period (Perrin et al. Reference Perrin, Ercoli and Dempster2001). This environment-dependent gender-related difference in behaviour may be associated with the environment-dependent difference in the magnitude of gender-biased parasitism.

Correlates of gender-biased infestation vary among parasite taxa

We found that the extent of male bias in infestation by fleas and lice was affected mainly by parasite-related variables, whereas environmental variables influenced male bias in infestation by ticks. This difference is not especially surprising because it reflects the profound differences in life history among parasite taxa. Lice are permanent parasites and reproduce directly on the host. Fleas are generally associated with the nest of the host and periodically attach to the host to obtain food. Consequently, fleas and lice may interact with other parasites, but their exposure to off-host environment is limited (Marshall, Reference Marshall1981). In contrast, a tick spends most of its life off-host and attacks a host solely to obtain a bloodmeal. Engorged ticks drop off from the host and re-emerge after development to the next stage on the vegetation in close proximity to the point of drop-off. By virtue of their life-history patterns, ticks are undoubtedly exposed to the environment much more strongly than other ectoparasites (Sonenshine, Reference Sonenshine1993).

Interestingly, we did not find any consistent effect of parasite-, host- and environmental factors on gender differences in mite infestation. Mites are associated with the nest of the host as are fleas (Radovsky, Reference Radovsky and Kim1985), so the effect of the off-host environment on their distribution is obviously weak. However, general lack of the influence of parasite- and host-related variables on between-gender mite distribution is intriguing. Two phenomena may underlie this lack. First, the diets of the majority of mite species consist of not only blood or another body fluid of a vertebrate host but also small arthropods including other mites. Second, blood feeding of gamasid mites is not always associated with direct host exploitation. Some mites obtain blood of a host via predation on other blood-feeding arthropods rather than via direct blood sucking (Tagiltsev, Reference Tagiltsev1957).

Overall, the results of our study suggest that the gender-biased pattern of ectoparasite infestation is a complicated phenomenon that involves several different mechanisms. The manifestation and magnitude of gender-biased parasitism are not only linked to a variety of parasite-, host- and environment-related factors, but patterns of these links may differ among ectoparasite taxa.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The protocol of the study was approved and permits were issued by the Ethical Committee of the University of Stellenbosch and by the Western Cape Nature Conservation Board. We are grateful to J.-C. Beaucournu, L.A. Durden, I.G. Horak and E. Ueckermann for the identification of the ectoparasite species, C. Boonzaaier, P. le Roux, C. Matthee, C. Montgelard and M. van Rooyen for field and technical assistance. This study was funded jointly by the National Research Foundation (bursary to S.M.) and the University of Stellenbosch. This is publication no. 674 of the Mitrani Department of Desert Ecology.