Today’s fluctuating and fiercely competitive global economy has led to increasing unpredictability for businesses. Technological advancements have likewise resulted in the quick turnover of preexisting knowledge. In this rapidly changing world, it is critical for organizations to remain competitive and sustainable. As many organizations have realized that human resources are one of their most valuable means of promoting sustainable development, they have begun to use human resource development (HRD) as an important business strategy to survive in this competitive environment (McCracken & Wallace, Reference McCracken and Wallace2000; Núñez-Cacho Utrilla & Grande Torraleja, Reference Núñez-Cacho Utrilla and Grande Torraleja2013). In the past, HRD practitioners played limited roles, such as providing training programs to develop employees’ knowledge and skills (Torraco & Swanson, Reference Torraco and Swanson1995). However, as business environments have become increasingly unpredictable, the role of HRD has been extended to include supporting top management in making organizational changes and resolving potential and current business problems by linking business goals and HRD strategies (Garavan, Reference Garavan1991, Reference Garavan2007; Alagaraja, Reference Alagaraja2013a). In this regard, HRD has come to signify strategic efforts that are implemented within an organization in order to manage changes and maximize the organization’s human-capital assets and performance (Anderson, Reference Anderson2009; Kolodinsky & Bierly, Reference Kolodinsky and Bierly2013).

Because HRD efforts should be strategically aligned with an organization’s business goals, top management’s interest in and support for HRD efforts have become crucial (Iles, Preece, & Chuai, Reference Iles, Preece and Chuai2010). Top management comprises those executives positioned in the high echelons of an organization. These executives have legitimate power to manage organizational resources and internal workforce investments, as well as to drive strategic intentions, or the guidance provided to all levels of employees within the organization (O’Shannassy, Reference O’Shannassy2016). Many researchers have argued that top management support is vital to the success of HRD functions, management programs, and organizational change (Rodgers, Hunter, & Rogers, Reference Rodgers, Hunter and Rogers1993; Ifinedo, Reference Ifinedo2008; Štemberger, Manfreda, & Kovačič, Reference Štemberger, Manfreda and Kovačič2011; Alagaraja & Egan, Reference Alagaraja and Egan2013; Hwang, Reference Hwang2014). For instance, top management commitment and participation have been shown to positively influence the success of HRD interventions and different management programs such as career development programs, product quality programs, and the implementation of management by objectives (Rodgers, Hunter, & Rogers, Reference Rodgers, Hunter and Rogers1993; Alagaraja & Egan, Reference Alagaraja and Egan2013; Sridhar, Reference Sridhar2015). Opinions and strategies communicated by top managers lead to changes in organizational structures and strategies such that the strategic changes follow the structural changes (Zakrzewska-Bielawska, Reference Zakrzewska-Bielawska2016). Procuring top management support also helps HRD professionals to be successful in shaping HRD strategies, securing budgets, implementing interventions, and gathering support from other stakeholders (Štemberger, Manfreda, & Kovačič, Reference Štemberger, Manfreda and Kovačič2011).

Top management is also a critical influence on employees’ job satisfaction and commitment to their organizations (Niehoff, Enz, & Grover, Reference Niehoff, Enz and Grover1990; Ugboro & Obeng, Reference Ugboro and Obeng2000; Kim & Brymer, Reference Kim and Kang2011). By sharing a clear vision with employees and engaging in supportive behaviors, top management can play a significant role in enhancing employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment, which may ultimately contribute to high levels of organizational performance (Niehoff, Enz, & Grover, Reference Niehoff, Enz and Grover1990; Kim & Brymer, Reference Kim and Kang2011; Arnold, Connelly, Walsh, & Martin Ginis, Reference Arnold, Connelly, Walsh and Martin Ginis2015). In other words, top management’s vision and support can have a positive impact on employees’ attitudes toward their jobs and the organization as a whole.

Through strategic collaboration and alignment, HRD and top management should provide enough support to show that they appreciate and respect employees as valuable talent, thereby leading employees to commit to and be satisfied with their organizations and work responsibilities. HRD functions and roles have positively contributed to enhancing employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2001; Shields & Ward, Reference Shields and Ward2001; Tansky & Cohen, Reference Tansky and Cohen2001; Rowden, Reference Rowden2002; Benson, Reference Benson2006; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2007; Ramkumar, Reference Ramkumar2012). As an advocate for employees as well as a strategic partner of top management, the field of HRD could encourage employees to more fully engage in their jobs and organizations, thus increasing the likelihood of job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Although researchers have emphasized the importance of HRD roles and top management support in propelling employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment, many HRD departments still have only limited support from top management (Garavan, Reference Garavan1991; Klein, Wallis, & Cooke, Reference Klein, Wallis and Cooke2013). When an HRD department fails to gain top management support, HRD interventions are likely to be undervalued and hard to secure resources or gain support from other business functions.

The nature of HRD requires continuous and long-term investment (Swanson & Holton, Reference Swanson and Holton2009). However, many leaders in top management are under pressure for short-term performance improvements as a result of their shorter tenure cycles (Schloetzer, Aguilar, & Tonello, Reference Schloetzer, Aguilar and Tonello2013). Furthermore, they perceive training as a cost rather than an investment (Tseng & McLean, Reference Tseng and McLean2008). It is also extremely hard for HRD professionals to prove the return on investment and the business impact of HRD and employee learning (Tonhäuser & Seeber, Reference Tonhäuser and Seeber2015; van Rooij & Merkebu, Reference Vasilaki and O’Regan2015). Unlike quantifying the benefit of investing in facilities, assessing the financial benefits of investing in HRD requires expertise and resources (Wick, Pollock, & Jefferson, Reference Wick, Pollock and Jefferson2010). For these reasons, HRD may be pushed to the back of top management’s priority list even though many leaders in top management acknowledge the importance of HRD.

Previous studies have explored independently the roles of HRD and top management on employees’ attitudes (Avey, Reichard, Luthans, & Mhatre, Reference Avey, Reichard, Luthans and Mhatre2011; Thurston, D’Abate, & Eddy, Reference Thurston, D’Abate and Eddy2012; Young & Poon, Reference Young and Poon2013; Kim, Reference Kiecolt and Nathan2014; To, Martin, & Billy, Reference To, Martin and Billy2015). Yet among these studies, most have covered only limited aspects of HRD (e.g., training), rather than the expanded roles of HRD (e.g., as a strategic partner and change agent; Mankin, Reference Mankin2001; Garavan, Reference Garavan2007; Hamlin & Stewart, Reference Hamlin and Stewart2011). Additionally, few studies have supplied empirical evidence to support the moderating role of top management on the relationship between HRD efforts and employees’ attitudes. More research is needed to understand how the diverse functions of HRD play a role in employees’ satisfaction, determine whether HRD functions can enhance employees’ attitudes when top management provides support, and assess the impact of organizational context. In this regard, we attempt to pay more attention to the synergistic effect of top management support and HRD efforts, specifically aligning HRD strategies with business goals, the initiation of organizational change, and developmental opportunities. This study encourages leaders and HRD professionals to take a more proactive and supportive role in fostering employees’ satisfaction and commitment. In addition, this study suggests the importance of further research on how to most effectively enhance employees’ positive attitudes through strategic approaches from top management and HRD departments. Therefore, the main purpose of this study is to investigate the relationships among HRD efforts, top management support, and employees’ attitudes such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment in the context of Korea through an analysis of the Korean Human Capital Corporate Panel (HCCP) survey data. The research questions guiding this study are:

1. What is the relationship between HRD efforts and employees’ attitudes (job satisfaction and organizational commitment)?

2. Does top management support enhance the relationship between HRD efforts and employees’ attitudes (job satisfaction and organizational commitment)?

LITERATURE REVIEW

In this section, we review the HRD and management literature on HRD efforts, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and top management support, as well as the relationships among them.

HRD efforts

Over the years, there has been a convergence of the HRD, human resource management (HRM), and organization development (OD) fields (Ruona & Gibson, Reference Ruona and Gibson2004). HRM has evolved from its initial role of managing labor issues and personnel to one of improving efficiencies in human resource practices, as well as developing organizational strategies and systems through technology. Early OD activities focused on interventions related to individuals and interpersonal relations. Over the years, OD has shifted its emphasis to the application of assessments and tools to establish measures of effectiveness and organizational results. The three fields have some overlap in their focus on people and organizational systems; however, each retains certain unique features. This study focuses on the efforts expended by HRD professionals as measured by the Korean HCCP.

The term HRD has been widely used to indicate many different activities in various contexts (McCracken & Wallace, Reference McCracken and Wallace2000). Although there is no single definition of HRD (Rothwell & Sredl, Reference Rothwell and Sredl2000), a number of scholars have described the features of HRD. According to McLagan, HRD refers to the ‘integrated use of training and development, career development, and organization development to improve individual and organizational performance’ (Reference McLagan1983: 7). Swanson and Holton defined HRD as ‘a process of developing and unleashing expertise for the purpose of improving individual, team, work process and organizational system performance’ (Reference Swanson and Holton2009: 4). Kuchinke (Reference Kuchinke2010) remarked that HRD includes strategic decisions and specific interventions using trainings, professional and leadership development interventions, organizational change, and knowledge management. Taken together, HRD is a process that is made up of various complex approaches designed to increase the value of human capital, with the ultimate purposes of increasing performance and developing the individual.

Despite these diverse approaches to HRD, many studies have focused on training interventions in HRD roles (Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2001; Rowden, Reference Rowden2002). For instance, Bartlett (Reference Bartlett2001) found that access to training is strongly associated with organizational commitment, and Rowden (Reference Rowden2002) found that workplace learning increases employees’ levels of job satisfaction in small businesses. Although training is a significant part of HRD, it is necessary to consider a more comprehensive role for HRD as it relates to imperatives of a global environment and HRD professionals’ efforts to facilitate innovation and its subsequent competitive advantages through the development of social capital (Gubbins & Garavan, Reference Gubbins and Garavan2009). In this regard, this paper defines HRD efforts as follows: (a) aligning HRD strategies with business goals, (b) facilitating organizational change and innovation, and (c) providing individual professional-development opportunities.

Aligning HRD strategies with business goals

As greater emphasis is placed on increasing the productivity of employees and on improving financial outcomes, aligning HRD strategies with an organization’s business objectives has become critical to HRD professionals (Zula & Chermack, Reference Zula and Chermack2007). HRD interventions should not be decided separately from business plans; rather, training should be used as a strategic tool to meet the needs of an organization (Garavan, Reference Garavan1995). As part of the change management structure of an organization impacting business goals and outcomes, many HRD professionals implement communications systems and advocate for downstream benefits to employees (Short & Harris, Reference Short and Harris2010). HRD professionals’ purpose of aligning strategies with business goals is to advance the strategic intent of the interventions (O’Shannassy, Reference O’Shannassy2016).

Facilitating organizational change and innovation

Given the rapidly changing business environment and increased global competition, organizations should keep up with the shifts to remain competitive through innovation. Based on their expertise, HRD professionals can support an organization’s ability to adapt and respond to changes both globally and internally (Domínguez-CC & Barroso-Castro, Reference Domínguez-CC and Barroso-Castro2017). HRD professionals help employees learn and manage change to increase an organization’s effectiveness and capability to change itself (Cummings & Worley, Reference Cummings and Worley2014). HRD provides systemic and systematic change interventions (e.g., organization assessment, organization design, culture change programs, team building, process consultation, and performance appraisal) to transform the organization with an eye toward long-term goals (Rothwell, Stavros, & Sullivan, Reference Rothwell, Stavros and Sullivan2010; Short & Harris, Reference Short and Harris2010).

Providing individual professional-development opportunities

Both individual and organizational performance improvements are the results of individuals’ learning. Because HRD professionals believe in human potential and development (Swanson & Holton, Reference Swanson and Holton2009), they foster a learning environment and provide learning opportunities (e.g., formal training programs, mentoring, coaching, and career workshops). Sometimes visible and measureable outcomes from learning experiences are delayed (Sheehan, Reference Sheehan2014), but the acquired knowledge, skills, and abilities enable profound changes. Therefore, organizations should provide learning opportunities to enhance their employees’ competence and expertise.

Job satisfaction

As one of the most widely explored constructs in the HRD arena, job satisfaction is regarded as ‘the pleasurable emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job as achieving or facilitating the achievement of one’s job values’ (Locke, Reference Locke1976: 1300). Job satisfaction is a relatively short-lived feeling about a specific job or task, whereas organizational commitment is a more stable and general feeling about an organization (Mowday, Steers, & Porter, Reference Mowday, Steers and Porter1979). Job satisfaction is used to help determine organizational effectiveness, employee attitudes, employee behaviors, and employee expectations. Employees who enjoy the work they are performing and their roles in an organization report proportionately more positive responses to job satisfaction measures (Lu, While, & Barriball, Reference Lu, While and Barriball2005). Poor job satisfaction, as reported by employees, is related to increased employee absenteeism, increased employee turnover, and early retirement intentions (Loke, Reference Loke2001; Koponen, von Bornsdorff, & Innanen, Reference Koponen, von Bornsdorff and Innanen2016). Scholars have consistently reported that job satisfaction significantly influences multiple outcomes, such as performance, organizational commitment, and turnover intentions (e.g., Egan, Yang, & Bartlett, Reference Egan, Yang and Bartlett2004; Froese & Xiao, Reference Froese and Xiao2012; Bowling, Khazon, Meyer, & Burrus, Reference Bowling, Khazon, Meyer and Burrus2015).

Studies conducted in a variety of global contexts have found positive relationships between human resource efforts (i.e., HRD, HRM, and OD efforts) and job satisfaction (Gould-Williams, Reference Gould-Williams2003; Poon, Reference Poon2004; Petrescu & Simmons, Reference Petrescu and Simmons2008; Avey et al., Reference Avey, Reichard, Luthans and Mhatre2011; Andreassi, Lawter, Brockerhoff, & Rutigliano, Reference Andreassi, Lawter, Brockerhoff and Rutigliano2014; Farahbod & Arzi, Reference Farahbod and Arzi2014; Koç, Çavuş, & Saraçoglu, Reference Koç, Çavuş and Saraçoglu2014). Many researchers have argued that HRD efforts are significantly related to employees’ job satisfaction (Rowden, Reference Rowden2002; Chen, Chang, & Yeh, Reference Chen, Chang and Yeh2004; Egan, Yang, & Bartlett, Reference Egan, Yang and Bartlett2004; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2007; Dirani, Reference Dirani2009). When an organization offers employees opportunities to develop their careers, the employees’ job satisfaction increases (Chen, Chang, & Yeh, Reference Chen, Chang and Yeh2004). Employees are more likely to be satisfied with their jobs when their organizations strongly encourage them to engage in learning activities (Egan, Yang, & Bartlett, Reference Egan, Yang and Bartlett2004). Providing continuous learning opportunities and strategic leadership in learning have a significant effect on job satisfaction (Dirani, Reference Dirani2009).

Organizational commitment

Organizational commitment refers to one’s attitude toward an organization and is defined as ‘emotional attachment to the organization’ (Mowday, Steers, & Porter, Reference Mowday, Steers and Porter1979: 2). The construct of organizational commitment has three components: affective, continuance, and normative commitment (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1991). Affective commitment indicates ‘one’s emotional affection toward an organization’ (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1991: 67). Continuance commitment refers to ‘commitment based on the costs that employees associate with leaving the organization’ (Allen & Meyer, Reference Allen and Meyer1990: 1). Normative commitment means ‘employees’ feelings of obligation to remain with the organization’ (Allen & Meyer, Reference Allen and Meyer1990: 1). Scholars have found stable and consistent empirical evidence supporting affective commitment as representative of organizational commitment (Ko, Price, & Mueller, Reference Ko, Price and Mueller1997; Solinger, Olffen, & Roe, Reference Solinger, Olffen and Roe2008). Accordingly, in this study, organizational commitment refers to only affective commitment.

Empirical evidence has been found to support a significant relationship between HRD efforts and affective commitment (Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2001; Joo, Reference Joo2010; Jung & Choi, Reference Jung and Choi2014; Dhar, Reference Dhar2015; Ismail, Reference Ismail2016). Perceived opportunities of access to training and receipt of support for learning have been shown to be positively related to affective commitment (Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2001). Employees show stronger levels of affective commitment when their organizations provide significant learning and development opportunities, such as continuous learning, dialogue and inquiry, team learning, and empowerment (Joo, Reference Joo2010). Additionally, training has been found to have a significant effect on organizational commitment (Ismail, Reference Ismail2016).

Top management support

In this study, top management support refers to top management’s participation in or commitment to HRD efforts. Top management is ‘all inside top-level executives including the chief executive officer, chief operating officer, business unit heads, and vice president’ (Kor, Reference Kor2003: 712). These executives are significant stakeholders in HRD due to their roles and responsibilities in developing the organization’s vision and encouraging employees to participate in its achievement (Niehoff, Enz, & Grover, Reference Niehoff, Enz and Grover1990; Garavan, Reference Garavan2007). Top management’s philosophy regarding HRD strongly influences HRD efforts. The success of strategic changes or management programs rests on the commitment of top management (Rodgers, Hunter, & Rogers, Reference Rodgers, Hunter and Rogers1993; Edwards, Reference Edwards2000; Lakshman, Reference Lakshman2009; Abebe, Reference Abebe2010; Billing, Mukherjee, Kedia, & Lahiri, Reference Billing, Mukherjee, Kedia and Lahiri2010; Young & Poon, Reference Young and Poon2013; To, Martin, & Billy, Reference To, Martin and Billy2015). These outcomes result from top management’s directions for the change and control over the organization’s resources and systems. After analyzing 15 cases in an extension of prior research, Young and Poon (Reference Young and Poon2013) argued that top management support is the most important success factor for teams and their projects, and that the support of top management is sometimes sufficient for success because it reduces the occurrence of misdirected efforts.

The synergistic effect of top management support

Top management support is expected to moderate the relationship between HRD efforts and job satisfaction and organizational commitment for the following two reasons. First, HRD efforts can be strengthened through top management support. Top management’s interest in and support of employees’ professional development has been shown to be crucial for the development of an organization’s overall strategic HRD because members of top management are the final decision-makers who allocate resources and determine the strategic direction of the business, including employees’ development (McCracken & Wallace, Reference McCracken and Wallace2000; Sung & Liu, Reference Sung and Liu2016). Top management support has also been found to be the most important factor for project success (Young & Jordan, Reference Young and Jordan2008). Given that HRD efforts include various projects, top management’s support of the projects is expected to be vital for the success of HRD.

Second, top management support has been significantly and positively related to job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Niehoff, Enz, & Grover, Reference Niehoff, Enz and Grover1990; Putti, Aryee, & Phua, Reference Putti, Aryee and Phua1990; Rodgers, Hunter, & Rogers, Reference Rodgers, Hunter and Rogers1993; Abraham, Reference Abraham1997; Ugboro & Obeng, Reference Ugboro and Obeng2000; Jensen & Luthans, Reference James and Brett2006; Vasilaki & O’Regan, Reference van Rooij and Merkebu2008; Kim & Brymer, Reference Kim and Kang2011; Ng, Reference Ng2015). Top management activities such as sharing the organization’s vision and communicating policies have been considered highly related to organizational commitment (Putti, Aryee, & Phua, Reference Putti, Aryee and Phua1990). Employees experience decreased job satisfaction when top management reduces its commitment to a management program (Rodgers, Hunter, & Rogers, Reference Rodgers, Hunter and Rogers1993). Employees display high levels of organizational commitment as a result of an organization’s positive treatment and positive affective feelings (Ng, Reference Ng2015). When HRD efforts are undertaken within an organization, employees are expected to feel greater levels of organizational commitment and job satisfaction if they perceive top management’s support of the efforts.

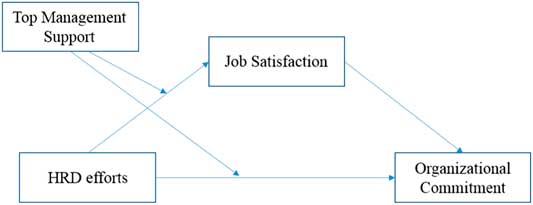

Based on this review of the literature, a research model was developed as illustrated in Figure 1. We also conceptualized three models for analysis in Figure 2; these models portray the directed dependencies among the variables in this study. Model 1 indicates that HRD efforts have both direct and indirect effects on organizational commitment, whereas Model 2 posits job satisfaction as a mediator between HRD efforts and organizational commitment. Finally, we position top management support as a moderator for the overall effect of HRD efforts in Model 3. Given these three models, the following hypotheses were developed:

Hypothesis 1: Top management support moderates the relationship between HRD efforts and job satisfaction such that the relationship is stronger when the support is stronger.

Hypothesis 2: Top management support moderates the relationship between HRD efforts and organizational commitment such that the relationship is stronger when the support is stronger.

Hypothesis 3: Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between HRD efforts and organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 4: Top management support moderates the indirect effect of HRD efforts on organizational commitment through job satisfaction. In other words, the indirect effect of HRD on organizational commitment through job satisfaction is stronger when top management support is present.

Figure 1 A research model. HRD=human resource development

Methods

Research context and sample

This study used data from the 2016 HCCP. The HCCP survey, one of the Korean government’s official surveys, has been conducted by the Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training (KRIVET) every other year since 2005. The purpose of this survey is to accumulate long-term data in order to better understand HRD in Korea. The population of the survey is 4,072 corporations in Korea excluding government-owned and private companies.

KRIVET’s 2016 iteration of the survey includes samples from 467 for-profit companies with 10,069 employees. Within the 10,069 cases, we limited our sample to large companies that have more than 300 employees and independent HRD departments. This limitation was imposed because large companies tend to have more independent HRD functions that allow them to provide systemic HRD supports to their employees. After controlling our sample, 3,977 cases from 159 companies were selected. Of the 3,977 participants, 78 failed to complete all items on the survey. To examine the pattern of the missing data, Little’s Missing at Completely Random test was conducted (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2003). The result of the test indicated that the nature of the missing data was random (χ2=267.566, df=247, p=.176). Therefore, those 78 incomplete cases (2%) were eliminated from further analysis using listwise deletion.

The final data set for analysis represented 3,899 employees from 159 large companies. Of the 3,899 employees, 3,100 were male (79.5%) and 799 were female (20.5%). In terms of the highest educational level completed, 65% of respondents graduated from college, and 27% of them had earned high-school diplomas. The majority of the employees were in their 30s (41.9%) followed by their 40s (34.4%), 50s (16.5%), 20s (6.1%), and 60s (1.1%). The sample was collected from various business sectors, including manufacturing (n=112, 70%), finance (n=20, 13%), and the service industry (n=27, 17%).

Measures

In order to measure the four variables, 16 items were selected from the sixth HCCP questionnaire. All variables were measured using a Likert scale ranging from 1=‘strongly disagree,’ to 5=‘strongly agree’. The Cronbach’s α reliability of each measure ranged from 0.78 to 0.90, thus demonstrating the study’s sufficient internal consistency.

Top management support

In order to measure the level of top management support in an organization, three items were selected. Examples of these items include: ‘Our top management has a clear vision for human resource development,’ and ‘Our top management often emphasizes the importance of talent.’ The reliability of the three items was 0.90.

HRD efforts

Seven items were selected in order to measure an organization’s comprehensive HRD efforts, including aligning HRD strategies with business goals (three items), facilitating organizational change and innovation (one item), and providing individual development opportunities (three items). Sample items for each of these three efforts are, respectively: ‘The HR department plays a key role in planning the organization’s business strategies,’ ‘The HR department initiates change and innovation,’ and ‘The company provides sufficient learning and training programs.’ The reliability of these seven items was 0.87.

Job satisfaction

The job satisfaction of employees was measured using three items, some of which are: ‘I am satisfied with my job’ and ‘I am satisfied with the relationships among my colleagues.’ The reliability of the three items was 0.83.

Organizational commitment

In order to measure organizational commitment, three items were selected from the KRIVET survey; example items include: ‘I feel like my company’s problem is my own problem,’ and ‘It is worth it to be loyal to this company.’ Most of the items were very similar to questions developed by Mowday, Steers, and Porter (Reference Mowday, Steers and Porter1979) and Allen and Meyer (Reference Allen and Meyer1990). The reliability of these items was 0.78.

Control variables

Previous studies have shown that demographic variables such as gender, age, and tenure correlate significantly with employees’ attitudes (Reed, Kratchman, & Strawser, Reference Reed, Kratchman and Strawser1994; Kim & Kang, Reference Kim2016). Therefore, we controlled for gender, age, and tenure in the organizations when testing our hypotheses to statistically remove these potentially confounding influences on the paths in the conceptual model (Hayes, Reference Hayes2015). Gender was dummy-coded (0=female, 1=male), and age and tenure were treated as continuous variables.

Results

SPSS 18 was used to examine the basic characteristics of the data and the relationships among the variables. These statistics included means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables, as reported in Table 1. All the correlation coefficients among HRD efforts, top management support, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment were statistically significant (p<.01), ranging from 0.48 to 0.63.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations

Note. The values on the diagonal are Cronbach’s α.

TMS=top management support; HRD=human resource development; JS=job satisfaction; OC=organizational commitment.

**p<.01.

To test the hypothesized models, we used hierarchical multiple regression analysis and a regression-based path analysis with the aid of PROCESS macro (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007; Hayes, Reference Hayes2012; Hayes, Reference Hayes2013). This model in Figure 2 consists of three distinct submodels. Models 1 and 2 were used to test whether top management support moderates the relationship between HRD efforts and organizational commitment and job satisfaction, respectively. Model 3 estimates the conditional indirect effect of HRD efforts on organizational commitment through job satisfaction. This model specifically tests moderated mediation, or the occurrence of a moderated effect that is carried through a mediator, quantified as the project of a 3 and b (Pollack, Vanepps, & Hayes, Reference Pollack, Vanepps and Hayes2012; Hayes, Reference Hayes2013).

These analyses were performed using mean-centering, which can alleviate any multicollinearity problems (Aiken & West, Reference Aiken and West1991). Table 2 illustrates the results of the ordinary least squares regression analysis of HRD efforts, top management support, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. In the first step, demographic information was entered. In the second step, HRD efforts were entered as an independent variable to examine the main effect on job satisfaction and organizational commitment. In the third step, top management support was included to examine the main effect on satisfaction and commitment. Finally, a multiplicative interaction item, HRD efforts and top management support, was included to examine the moderating effect on both satisfaction and commitment.

Table 2 Ordinary least squares regression Models 1 and 2 coefficients

Note. HRD=human resource development; TMS=top management support.

*p<.05.

The results indicated that HRD efforts explained 24.7% of the variance in job satisfaction and 25.5% of the variance in organizational commitment. Both of the coefficients were significant (β=0.42 and 0.44, p<.05), respectively. That is, HRD efforts were shown to be positively related to employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. In addition, the interaction between HRD efforts and top management support accounted for 32.4% of the variance in job satisfaction, and the coefficient was significant (β=0.07, p<.05). However, the interaction accounted for 33.0% of the variance in organizational commitment, and the coefficient was not significant. In other words, the relationship between HRD efforts and employees’ job satisfaction strengthens as top management support increases. The first hypothesis was thus confirmed, but the second hypothesis was rejected.

Figure 3 illustrates the moderating effect of top management support on the relationship between high and low levels of HRD efforts and job satisfaction. This graph provides high and low levels of top management support by drawing 1 SD above and 1 SD below the mean (Cohen & Cohen, Reference Cohen and Cohen1983).

Figure 3 Moderating effect of top management support (TMS) on the relationship between human resource development (HRD) efforts and job satisfaction

Hypothesis 3 proposes that the effect of HRD efforts on organizational commitment is achieved indirectly via job satisfaction. In path analysis, an indirect effect is the product of the effect of an independent variable on the mediator and the effect of the mediator on the dependent variable (Baron & Kenny, Reference Baron and Kenny1986; Hayes, Reference Hayes2013). To verify this indirect effect, bootstrapping was used. Bootstrapping for indirect effects produces a bootstrapped percentile and bias-corrected confidence intervals. The results of the bootstrapping, with a sample size of 2,000, are illustrated in Table 3. From the bootstrapping test, we found that the indirect effect of HRD efforts on organizational commitment (Hypothesis 3: β=0.10, confidence interval [0.020, 0.044], p<.05) via job satisfaction was statistically significant. Therefore, the third hypothesis was confirmed.

Table 3 Results of mediation effect

Note. CI=confidence interval.

Hypothesis 4 posited a moderated mediation effect wherein the mediation effect varies by the level of top management support. Moderated mediation is demonstrated by the following two conditions (Muller, Judd, & Yzerbyt, Reference Muller, Judd and Yzerbyt2005): (a) the main effect from the independent variable to the outcome variable is significant, and (b) the main effect from the independent variable to the mediator is significant when the moderator is controlled and the change in the effect of the mediator on the dependent variable is significant as the moderator changes.

Table 4 shows that the main effect of HRD efforts on organizational commitment was significant (β=0.112, p<.05), and the interaction effect of HRD efforts and top management support was also significant (β=0.074, p<.05). The effect of job satisfaction on organizational commitment when controlling for HRD efforts in the equation can be written in equivalent from: b(a 1+a 3 top management support). According to Hayes (Reference Hayes2015), a 3 b is a quantification of the effect of top management support on the indirect effect of HRD efforts on organizational commitment via job satisfaction. In this regard, Hayes calls a 3 b the ‘index of moderated mediation’ (Reference Hayes2015: 4). According to Table 4, moderated mediation was supported; job satisfaction was found to have a moderated mediation effect on the interaction of HRD efforts and top management support on organization commitment. Age and tenure were also shown to be positively and significantly related to both job satisfaction and organizational commitment. However, gender was found to be significantly related only to organizational commitment and to have no significance for job satisfaction.

Table 4 Ordinary least squares regression Model 3 coefficients

Note. All coefficients are unstandardized.

HRD=human resource development; TMS=top management support.

*p<.05.

Discussion

We hypothesized moderated mediation (James & Brett, Reference Jensen and Luthans1984) that HRD efforts would be associated with employees’ organizational commitment via job satisfaction and that top management support would amplify this indirect relationship (the indirect effect of HRD efforts on organizational commitment). The resulting analysis supports our theoretical expectations: HRD efforts were positively related to employees’ levels of organizational commitment through job satisfaction. In addition, the indirect relationship was shown to be moderated by top management support. A detailed discussion of the findings is provided below.

First, the results indicated that HRD efforts – aligning HRD strategies with business goals, facilitating organizational change and innovation, and providing individual professional-development opportunities – were positively associated with employees’ levels of job satisfaction. This study found that linking business goals and HRD strategies could increase employees’ levels of job satisfaction and eventually increase organizational commitment. When business goals and HRD strategies were not aligned, employees felt dissatisfied with their jobs. If their knowledge and skills were not developed in such a way that they could contribute to the organization’s goals, the employees struggled with work efficiency, and eventually their productivity levels decreased.

Interestingly, our study found that HRD efforts did not directly contribute to enhancing organizational commitment. Strategic HRD approaches require extended periods of time before outcomes materialize, which may lead employees to think that HRD efforts are not directly related to immediate benefits or that HRD efforts create more work and obligations. In this regard, when organizations pursue changes, top management and HRD professionals need to be prepared for the shifts; otherwise, HRD efforts might result in employees feeling overwhelmed and exhausted. By managing change successfully, HRD professionals can create new opportunities for employees and help to ensure the organization’s sustainability. In this regard, HRD efforts might help an organization’s employees to embrace change, thereby contributing to the employees’ satisfaction with their jobs and eventually increasing their commitment to the organization.

Furthermore, the statistically insignificant effect of HRD efforts on organizational commitments may be related to the size of the organizations with which the employees were affiliated. We selected large organizations with more than 300 employees. Even though HRD functions aim to initiate organizational change, align HRD strategies with organizational goals, and create more professional-development opportunities, these efforts might not directly improve employees’ commitment, given that organizational commitment has been shown to decrease when organization size increases (Sommer, Bae, & Luthans, Reference Sommer, Bae and Luthans1996).

More individual professional-development opportunities are important for employees to maintain their job security in today’s rapidly changing business environment. For this reason, employees have tended to prize the learning opportunities that are provided by their organizations. When they are able to increase their competency via developmental opportunities, employees feel satisfied with their learning achievement outcomes and job performance improvements. These results lead to employees’ more positive attitudes toward their jobs. This study thus provides an expansion of previous findings regarding the positive relationship between training and job satisfaction, as well as the indirect relationship between training and organizational commitment via job satisfaction (Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2001; Shields & Ward, Reference Shields and Ward2001; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2007; Ng, Reference Ng2015).

The results of this study also indicated that top management support had a moderating effect on the relationship between HRD efforts and employees’ job satisfaction. Furthermore, top management support was found to create a synergistic effect of HRD efforts on organizational commitment via job satisfaction. In other words, when there was strong top management support, the relationship between HRD efforts and organizational commitment through job satisfaction became stronger. These findings are in line with those of previous studies (Niehoff, Enz, & Grover, Reference Niehoff, Enz and Grover1990; Ugboro & Obeng, Reference Ugboro and Obeng2000) and provide additional evidence of the moderating effect of top management support and the necessity of the mediation of job satisfaction for improved organization commitment. Niehoff, Enz, and Grover (Reference Niehoff, Enz and Grover1990) found that top management’s actions, which include communicating the organization’s vision and encouraging employees, were positively related to employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Ugboro and Obeng (Reference Ugboro and Obeng2000) likewise observed that top management leadership is positively correlated with employees’ job satisfaction. Given that top management comprises those managers who model and share the organization’s vision, allocate resources, encourage and support employees, and make final decisions, it is perhaps unsurprising that their support is a vital driving force for the success of HRD.

Therefore, when top management emphasizes employees’ learning and development, the employees are more likely to feel satisfied with their jobs and eventually more committed to their organizations. Satisfied and committed workers are usually more reliable and put extra effort into their work, significantly improving their organizations’ productivity and innovation.

Implications for HRD research and practice

This study has both theoretical and practical implications for the HRD field. Theoretically, this study contributes to HRD research by providing empirical evidence of a synergistic effect between HRD efforts and top management support. Although many HRD researchers have argued that HRD strategies and interventions could be more effective if their plans and execution were supported by top management (e.g., Garavan, Reference Garavan1991; Torraco & Swanson, Reference Torraco and Swanson1995; McCracken & Wallace, Reference McCracken and Wallace2000; Wognum & Lam, Reference Wognum and Lam2000; Alagaraja, Reference Alagaraja2013b), there has been little empirical evidence to support this claim. Comparing the outcomes of this study to those of previous research, this study empirically confirms the relationship between HRD efforts and top management support while revealing the mediating effect of job satisfaction.

The methodology of this study emphasized a broader operationalization of HRD that could capture change management and various developmental activities in organizations. Previous studies have focused on the relationship between training and employees’ attitudes. This study provides additional evidence that HRD efforts and employees’ attitudes are significantly related by illustrating the role of HRD in enhancing employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

This study also provides implications for HRD practitioners. Given the synergistic effect between HRD efforts and top management support, HRD practitioners should try to gain top management’s support in order to maximize the effects of their efforts on employees and organizational outcomes. To obtain support from top management, HRD professionals need to recognize the reasons why top management has neglected to support HRD. For instance, some top executives devalue HRD functions and efforts because it is hard to prove their return on investment (Garavan, Reference Garavan2007). By marketing their services within the organization and convincing top managers to invest, HRD professionals may be able to draw top management’s attention to their work and efforts. HRD professionals should also seek to become the strategic partners of top management. Dedicated to increasing human capital and improving organizations’ performances, HRD professionals should seek to build trust and gain recognition from top management for their expertise.

Finally, HRD professionals should work to enhance employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment by considering how to manage change and strategically align HRD interventions with business goals. HRD professionals should consider comprehensive and diverse approaches, rather than limiting their efforts to conventional training programs, so that their work can lead to changes in employees’ attitudes. Of course, employees’ ages and employment tenures should be considered when HRD practitioners are preparing for interventions to improve job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Conclusion

This study found that HRD efforts were positively related to job satisfaction and organizational commitment, thereby corroborating the critical role of HRD professionals in an organization. The analysis of the data collected from KRIVET’s HCCP resulted in positive results similar to those found in other studies examining the individual relationships between HRD efforts, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and top management support. This study expanded the procedures for analysis to include a moderating and mediating structure, revealing that top management support moderates the relationship between HRD efforts and employees’ attitudes and that job satisfaction mediates organizational commitment. When the top management in this study had a clear vision for HRD and supported HRD functions and efforts, employees were found to be more satisfied with and committed to their jobs and organizations. Hence, HRD professionals should strive to build close relationships with top management, gaining trust and recognition for their expertise.

Despite these meaningful findings, there are several limitations to this study. First, this research relied on data and measures from KRIVET’s HCCP survey. The survey items may not measure the precise concepts that other researchers have used due to the limitations of working with secondary data (Kiecolt & Nathan, Reference Kim and Brymer1985). Moreover, we did not clarify the overlapping roles of HRM and HRD. Lastly, this study was based on the Korean context; therefore, the findings may be specific to Korean workplace culture. That being said, an examination of studies completed in other global contexts suggests similar results.

Future studies might adopt a time series design that would allow researchers to analyze factors related to job satisfaction and organizational commitment because the panel data has been collected at multiple time points. Researchers might also explore some more comprehensive roles of human resource, such as HRM, HRD, or OD, as they influence employees and organizational outcomes. Possible research topics include how the link or interaction between HRM and HRD influences employees’ performances in terms of their attitudes and outcomes. Additionally, scholars may examine similar research models in different cultural contexts or organizational settings. For instance, they might compare the effects of top management support on employees’ attitudes in for-profit and nonprofit organizations or between East Asian and Western cultures.