How is history related to wealth? In the late 1260s after an extended period of exile in France, the famous notary and teacher of Dante, Brunetto Latini, brought his encyclopedic Tresor back to his hometown of Florence. In the work's opening lines, he informs his readers that the book is called the Tresor (The Treasure) because

just as the lord who wishes to amass things of great value — not only for his own delight, but to increase his power and assure his estate in [times of] both war and peace — places, into one small space, the most precious jewels that he can according to his good intentions, so too, in the same way, the body of this book is composed of wisdom, that which is extracted from all the subjects of philosophy, in one brief summary.Footnote 1

After his short explanation of the book's title, Latini describes how each of the three books contained within the work corresponds to a species of the treasure to which he has just alluded. The second kind of treasure, he tells us, is like precious jewels, the third like fine gold, but the first, he says, is to be used “like cash money, to spend readily on necessary things.”Footnote 2 What kind of wisdom is he describing, then, that has such easy currency? It is, Latini reveals, “the beginnings of the world, and the earliest of the old histories, and the foundation of the world and of nature and all things.”Footnote 3 History and cash money are the same, he claims, for

just as, without money, there would be no means to exchange men's work and means to evaluate [the work of] one against the other, similarly one cannot grasp the other things fully without knowing the first part of the book [that is, history].Footnote 4

One of the most popular writers of Italy's late thirteenth century, therefore, considered history as precious as ready money, useful to have, easy to spend, and a good point of comparison with other kinds of knowledge.

Latini's materially-oriented approach to the value of history is, to say the least, unexpected for anyone familiar with the genre of historical writing produced in Italian cities during the age of the commune, from as early as the late eleventh until well into the fifteenth century.Footnote 5 Rolandino of Padua, for example, who wrote the twelve books of his history of the Trevisan March in around the year 1260, informed his readers that

the purpose of this book is to collect, briefly and summarily, all that is to the honor, and to the welfare and documentation of the people and the commune of Padua, and of all people everywhere.Footnote 6

And Jacob of Voragine, who recounted the history of Genoa roughly ten years after Latini composed the Tresor, humbly justified his Chronicle of the City of Genoa in the following words:

Thinking . . . how there are many cities in Italy of which the ancient historians make much mention, we are amazed that so very little can be found written by them about the city of Genoa . . . we have found certain details about the city of Genoa that we have decided to transcribe in the present fashion . . . Footnote 7

Like many historical writers of their time, Rolandino and Voragine presented their histories as a gathering together of information in support of the common good, not as a means of acquisition or a tool of comparative bargaining. And while the differences in approach among these writers may be attributed to their professional and social identities — Latini was a notary of the merchant class, Rolandino a jurist, and Voragine a Dominican archbishop — the tension between these presentations also reveals a fair amount of overlap in attitudes towards how historians assigned value, which in turn found expression in each of their works.Footnote 8 For Italians of the communal period, histories could both have value as narratives and simultaneously ascribe relative values to the things or situations that formed a part of their story. Latini's, Rolandino's, and Voragine's framings all uncover the symbiosis between the ways written histories allocate worth to the subject of a narrative and increase its significance because of the text's attentions, and the ultimate value that the text itself might then have as a means to document experience and thereby shape communal priorities.

Within the Italian corpus of historical texts, and particularly those written during the height of Italian civic historiographic production from the mid-thirteenth to mid-fourteenth centuries, authors regularly indicated worth (or made something worthy of attention) by creating associations between material goods and the subjects of their narratives. Late thirteenth-century Venetian chronicler Martin da Canal, for example, provided a vivid and exhaustive description of the rich clothing and costly accoutrements worn by late fourteenth-century guild members as they processed through the city to pay homage to the new doge's wife, the dogaressa.Footnote 9 As da Canal told it, the stunning, accumulated treasure of the guild members magnified the honor paid to her, which in turn elevated the status of the city about which he was writing. On the other hand, authors who reported on the cumulative effect of factional warfare that so plagued northern Italian cities at the same moment often recounted the number of homes, towers, buildings, or even trees that were destroyed by one faction or the other during such conflicts. Enumerating the destruction of material property was a technique used by nearly all Italian historical writers of the period and could denote the great malice of an enemy or the failure on the part of the hometown government to adequately protect its inhabitants. Mentioning material wealth in town histories allowed historians to glorify or vilify the subjects about which they wrote.

Yet, writing about material goods was not merely a fashionable literary technique among Italian historians of the mid-thirteenth to mid-fourteenth centuries, nor was it simply part of the outpouring of town patriotism scholars of the peninsula have termed “civic humanism.”Footnote 10 Rather, the seemingly ambiguous or at times even contradictory approaches towards history and wealth found in the town history corpus may also be attributable to real changes taking place in the economies of the Italian peninsula at the same time. In the 1970s, economic historian Carlo Cipolla, along with several other economic historians of the same school, tracked the turn in pre-modern economies away from a dominant model of wealth based on accumulation to the one built upon systems of exchange first nurtured in the economic environments of medieval Italian towns. The shift took root as early as the eleventh century, but it was particularly evident during the mid-thirteenth to mid-fourteenth centuries, at the very moment Italians were so abundantly writing the histories of their towns.Footnote 11

For Cipolla and others, the most significant motor for the move away from wealth-building based on savings (what Latini placed in his second and third categories) were the large-scale corporate trade ventures that required an investment of both trust and capital on the part of multiple sponsors. The opening gambit for such an undertaking, that is, the price of entry for anyone wishing to participate in corporate money-making efforts, was the influx of cash that enabled the venture to take place in the first instance. Whether it was overseas trade or the overland cloth market, those who had money to invest could subsequently reap their share of the financial benefits if the venture were profitable. The techniques of financial exchange first developed in Italy supported an economic activity predicated upon the availability of liquid assets, which in turn allowed a larger segment of society to access mechanisms of wealth-building and the material goods those riches could buy. If, as Cipolla asserts, cash was the key to social mobility for medieval inhabitants of the peninsula, this sheds a new light on how Latini's analogies might have resonated with his readership and why other writers of history may also have looked to material wealth as a worthwhile and even necessary theme.

Because the town was the primary space in which fortunes were born and nurtured in medieval Italy, views on wealth certainly shaped how civic history was written. Although modern literature on history writing in Italy has considered the social and professional backgrounds of those who wrote town chronicles or the relative wealth of audience members who consumed them, the semantic value of wealth within the urban community in these same writings has yet to be addressed.Footnote 12 Vittore Branca's groundbreaking study of the mercanti scrittori, for example, worked to legitimize the writings of domestic chroniclers during the Italian communal period and argued for their inclusion into the scope of a national literary history, but his anthology of city-based merchant chroniclers brought together texts that placed the stories of merchant writers’ families — not their hometowns — at the center of their narratives.Footnote 13 Janine Larmon Peterson's recent exploration of the relationship between Italian merchants, their wealth, and the language of negotiated piety undertakes an approach to hagiographic writings similar to what this article wishes to do for works of historical writing, that is, to ask how material wealth and attitudes towards it shaped and informed Italian municipal history writing at the highpoint of its production in the mid-thirteenth to mid-fourteenth centuries.Footnote 14

The Town Chronicle Repertoire, 1250–1350

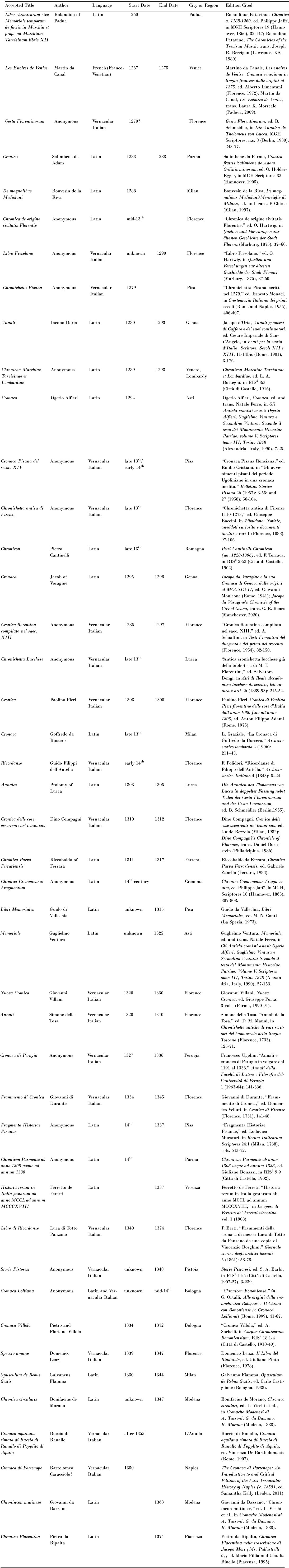

The question of how medieval historians bore witness to the relationship between members of their society and their material wealth has implications for our understanding of Europe's economic and cultural past, and even how both material wealth and the region's history have been distilled for us today. This article will therefore examine a corpus of over forty town-centered historical texts written contemporaneously with the economic shifts occurring from the mid-thirteenth to mid-fourteenth centuries to determine how civic historians portrayed wealth, money, and material goods, and medieval Italians’ relationships to them.Footnote 15 Although the town serves as the main point of reference for all of the histories in the corpus, the texts vary widely in length, form, and content, so that making close comparisons among them can at times present incongruities. The works were composed in both Latin and vernacular languages and authored by historians whose professional lives (as notaries, churchmen, or poets, for example) depended on their skills in writing, or by other highly literate citizens (including bankers and merchants), whose work lacked the generic sophistication of their more learned peers. Earlier histories appear more annalistic than narrative and were more likely written by ecclesiastics than laymen. By the early fourteenth century these tendencies fade, and an increasingly narrative style and professionally diverse authorship are more common. By roughly the year 1350, starting in and around Florence, however, previous practices of writing civic history in Italy fell out of favor and were largely replaced by texts shaped more by humanist themes and interests than by the authors’ immediate circumstances; the late fourteenth century saw a marked decline in production from what might be called “the citizen chronicler.”Footnote 16 Pre-humanist city chronicles offer a far less stylized version of town life than their post-1350 counterparts, and therefore will serve as the source base for this study.

Authors of pre-humanist civic histories produced their town-centered works at a regular pace over the course of the century between 1250 and the decade or so after 1350; of the forty-three works in the corpus under consideration, nineteen were written before 1300, twenty-three after 1300, and one straddles the divide between the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. However, the communities chronicled were situated unevenly along the length of the peninsula, from Naples in the southwest to Venice in the northeast. Far fewer works were produced in the south than the north, and even if multiple works were written in certain northern towns (especially Genoa, Florence, Venice, and Pisa), only one or two were composed in others. This means the sample of extant histories is skewed towards large communities in the north, with Florence represented disproportionately, as opposed to an even distribution of writings produced throughout the Italian territories.

The Nuova Cronica of Giovanni Villani, also from Florence, poses one additional methodological pitfall.Footnote 17 The Cronica stands out among contemporary historical works for both its comprehensive scope and subsequent impact upon the next generation of peninsular history writers. Because Villani was a member of one of Florence's banking families and therefore disproportionately attuned to questions of money, wealth accumulation, and the place of material goods within that society, he refers to all of these elements frequently in his work. Given the length of Villani's history and his recurrent attention to wealth and material goods, the Nuova Cronica will be treated in a section apart, so as not to tip the analysis too heavily in its favor.

Despite the differences in form, content, and geographic orientation, the corpus provides a view to the rich range of attitudes towards material wealth that authors depicted as neither wholly good nor evil. The examples put forth in the following pages are not exhaustive, but rather deliberately aggregative so as to illustrate the regularity with which medieval Italian writers addressed material concerns and how mixed their attitudes were.Footnote 18 With such a large corpus, a computer-enabled approach might seem the most efficient, where words and concepts form the basis of a targeted search through the texts to find passages related to wealth.Footnote 19 While the histories are organized in a spreadsheet to provide an overall view of where and when they were produced, a machine-based search ultimately proved inefficient, due largely to the linguistic variation found in the corpus; instead, a process of “mid-range reading” was employed. Edited versions of the texts were visually scanned for key words and concepts related to wealth and material goods, and once identified, were entered into a table, and categorized according to type of mention, as reflected in the subheadings below.Footnote 20 The categories were not imposed at the outset of the study, but rather emerged as a set of standard tropes found in the texts.

What this approach has revealed is that even if some historians described the celebratory largesse of their towns in loving detail, others countered with reference to the sumptuary laws put in place to curtail such activities. Similarly, reports on a town's civic improvements were offset by lengthy descriptions of how armed conflict damaged those same building efforts, accounts of a town's abundant communal resources and healthy municipal finances stood in contrast to complaints about famine and scarcity, and discussions of abundance and excess were balanced out by considerations of the parameters of charity and greed. Although these contrasting approaches map out the varied topography of attitudes on earthy riches in mid-thirteenth to mid-fourteenth century Italy, they leave the reader no doubt that material wealth was a subject to be reckoned with. The treatment of material goods by medieval Italian historians, in both general and specific instances, reveals the many ways inhabitants of the peninsula were grappling with their new-found wealth and coming to terms with its place in their society.Footnote 21

Static or Dynamic Wealth?

Some remarks are in order on attitudes towards wealth within the corpus overall before more specific uses are examined. Looking to the repertoire diachronically, later chronicles (generally post 1310–1315) feature more frequent, diverse, and detailed considerations of material goods than do previous, late thirteenth- to early fourteenth-century chronicles. Earlier works mention material goods especially in terms of describing the damage resulting from armed conflict, including pillage, unjust seizure, and the costs of ransom. Many of these same concerns remain in later histories, but the treatment of material goods expands greatly in later sources, particularly in areas relating to the costs of continued factional warfare and the monetary consequences of these actions on town dwellers, including the costs to rebuild or the effects on commodities pricing.

What the repertoire at large suggests is that there is a move away from the view found in earlier annal-type Latin histories, that material goods are part of the static characteristics of those who own them, to the approach found in later histories that present material goods in a transactional or interactive capacity. One example of the static nature of material possessions in the earlier works is the frequent association of goods with the persons who owned them. This is often done with the use of some variation of the formulaic terms “in persons and possession,” or “in goods and persons,” implying that the goods owned by an individual were intrinsic to that person's identity. This terminology, found in many variations in the works of Rolandino of Padua, Iacopo Doria, Pietro Cantinelli, Paolino Pieri, and in the Storie Pistoresi, and elsewhere, conflates the person and his or her belongings so that events brought to bear upon individuals implicate their possessions as well.Footnote 22 Rolandino of Padua reports that “the army of Padua wished to destroy the da Romano in their persons and possessions,” and similarly, informs readers that the Lord Tiso da Camposanpiero came to rule the town of Cittadella, and praises him because the inhabitants “were respected in their persons and their possessions.”Footnote 23 Multiple examples from the repertoire reinforce the idea that a person's possessions formed a part of his or her whole identity.

A person's material goods were tied to his identity more often in the earlier histories in the repertoire and portray wealth as an immutable personal characteristic rather than a temporary state. The Cronica Fiorentina compilata nel secolo xiii characterizes Countess Matilda as “very rich woman” (richissima donna) to prove she was powerful, and Ogerio Alfieri complains that many of the rich citizens of Asti are “false.”Footnote 24 Rolandino of Padua speaks of a prominent family in Padua who posed a threat to Ezzelino da Romano because “they were very powerful in Padua in wealth, vassals, and friends,” and Riccobaldo of Ferrara notes that the wealthy could avoid exile, unlike other inhabitants.Footnote 25 At times, the lack of material goods is also documented, such as when Paolino Pieri observes that at Charles of Anjou's arrival in Italy in the late 1260s, he is called “sanza terra,” because he does not share in the inheritance of his brother the king of France.Footnote 26

Even if the use of “persons and possession” persists in the later chronicles, an interactive element appears especially when transactional elements such as the documentation of wills, testaments, or personal businesses dealings are introduced into the narratives. The description of these personal transactions then leads toward an integration of the city's political history with the effects those actions had on the business or personal dealings of the author. Although the later chroniclers do not discard the terminology uniting wealth with personal identity, a new type of dialogue about material goods emerges in the histories in the late thirteenth century, finding its fullest expression by the mid-fourteenth century. These later works describe many other ways that the value inherent in material goods can be deployed, so that real estate transfers, costs of conducting business, laws about money, financial transactions, and details about dowries, inheritances, and wills all become part of the historical discussion.

These concerns are present as early as the first quarter the fourteenth century with the inclusion of Guglielmo Ventura's will in his memoirs, and the later fourteenth-century works of Florentines Guido Filippi dell'Antella, Simone della Tosa, and Luca di Totto da Panzano adeptly illustrate this new historiographic trend.Footnote 27 Antella's work focuses primarily on his personal financial history, including records of quittance sums, real estate transactions, dowry amounts, and taxes, with the events of the city firmly in the background. Simone della Tosa's work, however, juxtaposes personal financial details, such as the records of his home and land purchases with the events occurring in the city at the same moment, often with explicit details about the town's financial expenditures, such as the costs of various peace treaties or fines imposed for a podestà's poor tenure as the city's main official.Footnote 28 Luca di Totto da Panzano reports that several noblemen were fined a sum of six thousand lire as a result of the city's Ordinances of Justice, but also that he personally lost “horses, arms, equipment, a silver girdle and a golden ring,” in the course of a conflict between Pisa and Florence.Footnote 29

Several of the topics discussed above, especially the pairing of famine with higher commodities pricing, the attention to how communal moneys are collected and used, and the recognition of the costs of war and reparations, all become more frequent in the later chronicles. This attention supports a more transactional view of material goods in later chronicles as opposed to their earlier histories, but also shifts the weight of fiscal responsibility and expectation from the individual benefactor to a town's collective governing bodies.

Du Luxe: Celebratory Largesse, Special Status, and Sumptuary Laws

Moving beyond the treatment of wealth in general, a deeper dive into how historians wrote about the specific uses of material goods reveals their equivocal role in Italian society during the mid-thirteenth to mid-fourteenth centuries. The many luxury items imported into the peninsular community were surely the most visible signs of material consumption for Italian communities and their historians at this time.Footnote 30 Luxury items, which have the power to dazzle and fascinate even if one is merely reading about and not beholding them, were described frequently in both negative and positive terms. Mention of luxury goods might fall into three categories: celebratory largesse, items that signal or confer special status, and the regulation of material consumption in the form of sumptuary legislation.

Descriptions of celebrations and the lavish items used in feasts, festivals, parades, and receptions are common throughout the corpus. The most striking example in the repertoire, mentioned above, comes from Martin da Canal's Les Estoires de Venise, written between 1267 and 1275. His description of the installation of a new doge in 1268 fills a full nineteen chapters, bursting with details of the silver vessels carried to the doge, the costumes covered in gold, pearls, and precious jewels, and the trumpets and cymbals that accompanied the procession towards the doge's palace and the dogaressa's home. Da Canal also related the items used during many other festivals which take place yearly in Venice, including those for Christmas, Easter, and the feast of St. Mark.Footnote 31 Rolandino of Padua provides great detail concerning the feasts held by Albizo da Fiore when he was podestà of Padua, including a description of the precious stones and costly silks worn by ladies of the court, as well as the delicacies and aromatics found at the castle where the festival took place, and a similar portrayal of a reception held for an incoming podestà.Footnote 32 Brief mention is made of the reception of the wife of King Charles of Burgundy in Pietro Cantinelli's history of Romagna (late thirteenth century), with animals covered in scarlet and all sorts of instruments brought to greet her.Footnote 33 Jacob of Voragine recounts the celebration of the Genoese, who burned silk flowers and golden insignia in response to a military victory.Footnote 34 Guglielmo Ventura (early fourteenth century) reports on the opulence at Matteo Visconti's wedding celebration, and Dino Compagni, in his Cronica delle cose occorrenti ne'tempi suoi (ca. 1310–1312), disapprovingly recounts the pope's arrival in his home town of Prato, where he was greeted by “ladies well dressed and the streets draped with cloth, dances, and instruments.”Footnote 35 He also notes how Pisa sent of Emperor Henry of Luxembourg sixty thousand florins to entice him to come to their city, then feted his arrival with banquets and celebrations.Footnote 36

The anonymous author of the Cronaca di Perugia notes twice how influential visitors (in the first instance a king, then a duke) were offered cups of golden coins upon their arrival (800 florins for the king, 600 for the duke) and how their female counterparts, the queen and the duke's wife, were also offered cups of coins, but with smaller quantities contained within (200 for the queen and 250 for the duchess).Footnote 37 Giovanni di Durante notes a similar ceremony involving coins in a cup, for a pact concluded between the Pisans and the Florentines.Footnote 38 The Chronicon Parmense, written between 1270 and 1340, records the feasting and celebration for a marriage which joined the houses of the Marquis of Ancona and the Captain of Milan, albeit with more emphasis on who attended than on the material realities of the feast, despite the mention that the city of Parma paid for some of the clothing used at the wedding.Footnote 39 A second wedding, between Pedro Rosso and his new wife Guncta, daughter of a Genoese nobleman, is described in great detail, including the instruments used during the feast and the gifts offered on the occasion of the marriage.Footnote 40 The Villola chronicle reports on a joyous celebration for a Bolognese victory with townspeople offering garlands to the soldiers and placing a golden crown and regal vestments on one of them to represent the victorious king Charles.Footnote 41 In a unique reference to celebratory largesse, the Villola chronicle also describes a celebration for the granting of a degree upon one of its native sons, Taddeo di Rumio de Pepolli, which may not be so surprising given the strong university culture of Bologna. Finally, the Villola chronicle also describes the lavish receptions offered for the papal legate, the cardinal of Spain, the lord of Bologna, and recounts the particulars of a three-day festival in celebration of the arrival of a cardinal, in which most of citizens of Bologna were dressed in new clothing and many rode on horses, who were also covered with rich fabrics and adornments.Footnote 42 The author of the Storie Pistorese notes that luxury items were offered at the arrival of prominent visitors, such as the gold and jewels given to the Emperor upon his arrival in Genoa, and in Todi. In an original entry, the anonymous Storie Pistorese author also makes note of a celebration lasting eight days that marked a peace treaty between the city of Bologna and the papacy.Footnote 43 Finally, Buccio di Ranallo refers to numerous celebrations throughout his Cronica Aquilana (written around 1355), including a description of the feasts and dances that accompanied the arrival of King Robert of Naples in 1310, and the colorful clothing worn in celebration of a peace treaty for the city.Footnote 44

A common theme running throughout the chronicles is that celebratory largesse exists as a mechanism of display for the town. In most instances, there is little or no judgment about whether the expenses accrued were justified. Rather, celebrations, feasts, and special ceremonies were occasions that allowed town-dwellers to collectively assert a set of communal values, be they religious or political, through the use of luxury goods or extraordinary expenditure. The most common material goods mentioned for celebration are extravagant fabrics such as sendal, silk, or cloth embroidered with gold, as well as precious jewels, pearls, and gold and silver ornaments. Also mentioned frequently are gold and silver instruments used to enhance the celebrations. Items made from luxurious materials, such as gold, marble, silver, gems, or rich fabrics are also used to draw particular attention to the persons receiving or using the special objects, and the items work to signal their special status, or to confer it. On other occasions, luxurious items are described for their own merits, though in the process of chroniclers marveling at their beauty and value, they often serve to indirectly enhance the status of the individuals who owned them.

Two items in particular, crowns and tombs, are consistently fabricated from luxurious materials with the purpose of signaling special status. The Chronicon Parmense is but one of the chronicles that mentions that Imperial crowns were made of gold and often decorated with silver or encrusted with jewels.Footnote 45 The Storie Pistorese claims that in 1327, Ludwig of Bavaria was given a crown of iron when the northern Italian magnates officially recognized him as the “King of Italy,” and that he would only receive a golden crown if he were able to attain enough political support and recognition to be crowned Emperor by the pope in Rome.Footnote 46 Saints’ tombs were often made from marble or decorated with luxurious items, in this case to bring attention to the holiness of the person whose remains were found within. Jacob of Voragine mentions the use of marble for the tomb of St. Syr and Goffredo da Bussero notes the addition of gold to the tomb of Milan's patron saint, St. Ambrose, in the year 840.Footnote 47 Pietro da Ripalta comments on the use of silver and alabaster for the relics of several saints, including Saints Martin and Eusubius.Footnote 48 And finally, Galvaneus Flamma describes the beautiful and costly tomb of a secular leader, the Marchesa Beatrice, whose son spent 40,000 florins in 1335 for her marble vault.Footnote 49

Churches were also locales which merited the use of luxury materials. The Villola chronicle observes that marble was used in the portal of Saint Peter's in Bologna, and Simone della Tosa describes how the pillars in the church of San Giovanni were covered in black and white marble and that monuments were placed inside the church itself.Footnote 50 Galvaneus Flamma brings attention to the chapel of the Blessed Mary, built by the Visconti and adorned with gold, gems, and precious stones.Footnote 51 The Chronicon Parmense describes the addition of two red and white marble lions placed at the door of the church of Santa Maria Maggiore to enhance the beauty of this church.Footnote 52

Luxury items could also perform special functions. Jacob of Voragine makes mention of the gold and silver weapons used by the Carthaginians in a rebellion against the Romans, and the author of the Cronica da Perugia describes how gold and silver were used in a ritual to ratify peace treaties in Perugia.Footnote 53 The beautiful baptismal gifts enumerated in Pietro da Ripalta's work, including “a silver vase and a golden cup full of pearls, rings, and precious stones, with a gilded silver foot,” and “a large cup with a crystal foot with silver branches and pearls on the branches all around the foot of the cup,” were offered by Ugolino Gonzaga to create a social bond between he and Bernabò Visconte, whose son was being baptized.Footnote 54 The author of the Chronicon Cremonense notes that the Emperor affixed a golden seal to the list of privileges for the city of Cremona.Footnote 55 At other times, luxury items added luster to those associated with them, such as when Paolino Pieri lists the beautiful items brought back by the Pisans after their victory in Majorca in 1118, including a large metal door that ultimately adorned the city's cathedral, or when Galvaneus Flamma describes the Visconti palace, with its numerous towers and rooms, and luxurious detailing and decor depicting animals, birds, and heroes from the past.Footnote 56

Given such attention to wealth, it is not surprising that mentions of restrictions on clothing appear in communal histories at roughly the same time that leaders of many medieval Italian towns began promulgating sumptuary legislation to regulate inhabitants’ excessive expenditures, including those spent on clothing. Although sumptuary laws primarily restricted paying exorbitant amounts on funerals, marriages, and baptisms, they also set limits on who was allowed to wear articles of clothing based on vocation or social status.Footnote 57 A 1388 set of Florentine amendments to sumptuary legislation from earlier in the century, for example, stipulates that under penalty of fifty lire “the wives of knights, doctors of law, canon law and of medicine” should only wear skins of ermine and vair on the sleeves of their garments as long as one-half of an eighth of a braccia, and no more.Footnote 58 Municipal regulation and civic historiography often worked hand in hand, so that a nostalgia for the honest fashion of times past became the justification for regulating what was worn in the legislators’ day.

In keeping with these contemporary legal categorizations of dress, persons of noble status in town histories are often described as wearing extravagant clothing, and those of lesser status, more modest apparel. Rolandino of Padua uses this technique when describing the Marquis Azo, who presided over a tournament that involved many of the noble men of the Trevisan March. The Marquis’ noble status was marked by the addition of ermine to his mantle, while others wore vair.Footnote 59 Rolandino speaks metaphorically about clothing, suggesting that when a certain judge disapproved of the actions of his political party he “changed his clothes” to match his new perspective.Footnote 60 Da Canal often pairs the nobility and gentle breeding of Venetian women with the luxurious nature of their clothes, and describes how the women of Genoa removed all of their golden buttons and ornaments as a sign of their sorrow when their city suffered a great loss against the Venetians.Footnote 61 Ogerio Alfieri also praises the beauty and nobility of the citizens of Asti by citing the silver, gold and pearl- and jewel-encrusted ornaments and collars worn by the rich women of the town along with their sumptuous garments.Footnote 62 Dino Compagni also remarks in his opening chapter that the women of Florence are lovely and adorned, and as discussed below, Giovanni Villani also offers an opinion about restrictions that should be made upon Florentine clothing, suggesting that the sartorial abuses are indicative of a want of moral character.Footnote 63 In one last example of how “clothes make the man,” even to the end, the author of the Chronicon Parmense records on three different occasions that prominent citizens of Parma were buried in rich vestments, and that the city paid for the burial robes as a sign of respect for these important inhabitants.Footnote 64

The earliest mention of sumptuary restrictions in the repertoire per se appears in the Gesta Florentinorum with an entry explaining that in 1274, the pope advised women they were not to wear pearls, gold and silver filigree work, nor to pull their clothing up to the mid-arm during lent, presumably in an effort to provide moral direction for them during their preparations for Easter.Footnote 65 The same sumptuary restrictions are noted by Simone della Tosa in his memoirs and were recorded under the same year-heading as found in the Gesta alongside a recitation of the political events of that year.Footnote 66 Buccio di Ranallo makes several references to clothing and clothing restrictions in his work, but most remarkably when he notes that the revenues from sumptuary fines were used to support the town's military expenditures.Footnote 67 The Villola chronicle records the sumptuary legislation for the year 1365, noting that only those who were of sufficient status could wear gold and that even these women had the restrictions placed upon them, including a maximum allowance of twenty five ounces of silver for a belt, as well as limitations on the types of luxury cloth used for their garments.Footnote 68 It is worth noting that the sumptuary restrictions recorded in the earlier works were often provided for moral instruction, but by the mid-fourteenth century they were both carefully quantified and viewed as a revenue source for the cash-strapped municipalities.

By way of contrast, the memoirs of Guido Filippi dell'Antella offer a more humble perspective on clothing, for his text includes an inventory of the garments left by his deceased brother, including two shirts, four breeches, an old doublet, and an old black cap.Footnote 69 The Libro del Biadaiolo remarks upon the pedestrian clothing worn at the grain market, and laments that even these poor garments were at risk of being stolen because those who came to buy grain were in such a desperate state.Footnote 70 Buccio di Ranallo explains that townspeople who were conspiring against a rival faction in Aquila cut off parts of their clothing so they would be recognized by their fellow co-conspirators.Footnote 71 Mention of clothing in the chronicles can therefore serve both symbolic and practical purposes in the narrative to demonstrate how actors appeared to those around them and how clothes could be used by their owners, despite the value of clothing to mark social status.

By relying upon the exceptional and sometimes exotic qualities of celebratory largesse, luxury items, and aristocratic clothing styles, historians indicated relative value, whether approvingly or critically, within the chronicle repertoire. However, just as writers noted the attire of poorer inhabitants, so too did they describe the more quotidian aspects of their physical realities to include the buildings, roads, churches, and town squares in which the action of their lives unfolded. Italian civic historians reported frequently on whether structures were being built up, torn down, or neglected to indicate the community's relative worth at certain periods in its history.

Building Up and Tearing Down: Civic Improvements and Civic Destruction

Construction increased in Italian city centers during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and was often initiated and regulated by the governing bodies of those same spaces.Footnote 72 The pace of urban construction and a town's ability to maintain communal structures, therefore, came to speak to a town's vibrancy under one regime or another. References to civic improvements are found throughout the repertoire from the earliest and most concise histories to later sources which provide rich detail on the specific costs and materials used in constructing civic works such as bridges, roads, town buildings, squares, walls, waterworks, and markets. Attention to civic works remains constant throughout the repertoire because they stand as tangible material expressions of town identity; they geographically shape life in the town and are permanent reminders of what unites one inhabitant with another.Footnote 73

At times, the parties responsible for improvements remain anonymous, but in other instances the city officials who initiated or completed the projects are given credit for the jobs they accomplished. In some instances, the ability for a town to complete civic improvements is coupled with an acknowledgement that the town was enjoying a period of peace during that same time. Particularly in the later chronicles, composed during a period of intense factionalism in northern Italy, authors cited the completion of civic projects to argue that the town in question could expand and prosper if only its population were to reject factionalism and work together in a spirit of communal harmony. The corollary to this use of material goods to support political co-operation is the pointed assertion in the chronicles that destruction and waste of material goods can often be directly attributable to factionalism.

Many of the early annalistic writings note only the date the works were completed or undertaken. These include the Gesta Florentinorum (composed around 1278) which records the building of bridges in 1218 and 1220.Footnote 74 Most of the first twenty-eight lines of the Chronichetta Pisana record the completion dates for various construction projects throughout the city, including churches, towers, gates, bridges, and walls.Footnote 75 The Cronica Ronciana of Pisa notes simply that the Castello di Castro was begun in Sardinia in 1217, alerting the reader that Pisa held significant power on the island during that time.Footnote 76 The Chronichetta antica di Firenze obliquely remarks upon the building of the pylons for the city's Charraia bridge.Footnote 77 Pietro da Ripalta observes that in one year, there was a great deal of money in Piacenza, and the city used it to build two gates to the city, the Fulberto Gate and the Great Gate, and that in the year 1315 city walls and a castle were both built in the city.Footnote 78 Writing about Modena, Bonifacius de Morano mentions almost nothing else relative to material goods, but does note the construction of a tower in Bologna in 1108, and that 1226 saw the construction of many other castles in the area.Footnote 79 Some histories are more expansive in their descriptions, although remain silent about those who completed the works in question. Bonvesin da la Riva describes the plenteous water-works throughout the city of Milan, including the measurements of the walls that enclose them, and adds that no other city in the world could claim such marvelous infrastructure.Footnote 80 Martin da Canal's description of the Cathedral of St. Mark achieves roughly the same purpose for Venice as do Bonvesin's praises for Milan.Footnote 81 The authors of the Chronica de origine civitatis and its vernacular adaptation, the Libro Fiesolano (composed around 1260–1280) also mention the importance of water-works and argue that those first built in Florence rivaled those of Rome.Footnote 82

The Franciscan Salimbene de Adam, who wrote his Cronica of the city of Parma from 1283–1288, grants collective credit to the townspeople of Reggio, who came together from every level of society, carrying sand, stones, and cement on their backs in a communal effort to build the great church of St. James.Footnote 83 In the earliest instance of individual credit given for completion of communal improvements, Abbot Arnaldus is recognized for his efforts to revamp the church of Santa Giustiana in the Chronicon Marchiae Tarvisinae et Lombardiae.Footnote 84 Pietro Cantinelli gives the name of the podestà of Bologna who governed when the new city hall was built, as well as who ruled when a new arena and towers were constructed in Ferrara.Footnote 85 Jacob of Voragine mentions the towers and a fortification constructed by the first inhabitants of Genoa early on in his work and at the end of his history praises the improvements made to the archiepiscopal palace by Lord Walter.Footnote 86 Paolino Pieri notes that work on the walls, gates, and churches of Florence was begun in the year 1218 and explains that the Rubaconte bridge was so named because the podestà who governed at the time it was begun was called Rubaconte and that he himself set the first stone.Footnote 87 The anonymous author of the Chronicon Parmense provided not only details about numerous communal projects undertaken in Parma, but included the costs to the city as well, such as the building of eight archways over the Galeria bridge at the price of six hundred imperial pounds.Footnote 88

While references to town improvements appear in many town histories, the opposite, that is, the destruction of a person's or group's goods by another, is the most consistent and pervasive theme concerning material realities found in the entire chronicle repertoire. It appears in the earliest and most terse of the chronicles as well as in the more expansive ones. In its most pared down form, chronicle authors simply state that one city overthrew another and destroyed it, as is the case in the Gesta Florentinorum which records that in 1258 “the Arentines took Cortona at night and destroyed it.”Footnote 89 At the other end of the spectrum, Paolino Pieri gives a minute description of damages done by factions in Florence, describing which houses were destroyed, and even which of the trees at each house (including the beautiful orange trees and cedars) were cut down.Footnote 90

Destruction of goods and property in the repertoire serves principally as a shorthand for the dominion that one party, be it a city, a faction, a tyrant, or a king, was able to secure over another. Gaining control over another's goods is done in many ways, not only by simple destruction, pillage, plunder, or unjust seizure, but also through the process of ransom, in which a sum of money is demanded from the disadvantaged party, or through exile, which separates the subject party from his real estate and possibly from his worldly goods. What is important to note in the context of this study and particularly when discussing the physical destruction of property is that the identification of who had control over material goods corresponds to who had power over the other, so that material goods become a medium through which power relations are expressed in the chronicle repertoire. The theme of destruction in the chronicles evolves over time so that other topics related to materialism that accompany the destruction theme emerge and develop according to their own trajectories. For example, the initial description of devastation from conflict eventually gives way to an acknowledgment in the chronicles that wars and battles have costs. These include the direct costs of equipping an army for battle or stockpiling goods to withstand a siege, but also indirect consequences like the costs for reparations or the expenses of disrupting commercial activity during times of war. These arguments become more prominent and well developed in later chronicles when factionalism is blamed for the material losses of both the citizens and the communities in many of the northern Italian towns.

Simple references to destruction can be found in most every one of the histories under consideration, but some of these references take on expanded meaning within the context of the particular text. Rolandino of Padua demonstrates how the destruction of Ezzelino da Romano's goods reveals his personality when he notes that “Ezzelino da Romano alone considered the damages done to his castles and lands in the March by the efforts of the armies of both sides as an outrage to himself,” but also quantifies and lists the booty obtained by forces that opposed Ezzelino, which totaled about 3,000 pounds and included livestock, money, clothes, and all moveable goods.Footnote 91 The Libro Fiesolano makes reference to the most famous of city destructions, the loss of Troy, to establish a noble lineage for the Florentines, while Ogerio Alfiero estimates that it cost his city, Asti, over 200,000 lire to wage a war against the nearby town of Alexandria.Footnote 92 The anonymous Pisan author of the Cronaca Pisana Roncinana notes that the Pisans went about defeating Lucca by both positive and negative means; first, by minting coins and crowning Conradin, their Imperial hopeful, and then by sowing the fields of Lucca with salt, and burning and destroying many of the lands around the city.Footnote 93 Among Pietro Cantinelli's many references to destruction, he specifies not only that trees, grain, and houses were demolished but also that wheat was carried off as booty by Manfred of Faenza.Footnote 94 The Chronichetta Lucchese describes a litany of damage undertaken in the years between 1104 and 1117, during which time the fortress of Chastagnori was destroyed by the people of Lucca, the Lucchese destroyed Ripafratta and seized the chatelaines living there, and the Florentines destroyed the Castle of Gualandi and also captured Prato, dismantling its walls in the year 1117.Footnote 95

Aside from outright destruction there were other ways war and conflict could be costly to a town, and many types of material goods were manipulated to meet these expenses. Riccobaldo of Ferrara explains that the Ferrarese paid off the Veronese in land to assure them of protection from aggressors.Footnote 96 The Genoese chronicler Iacopo Doria provides both a description and a monetary value for the merchandise lost in many of the ships that came under enemy control during his city's conflicts with other maritime powers, including Pisa and Venice.Footnote 97 The Chronicon Marchiae Tarvisinae et Lombardiae notes that it was an expensive proposition for Venice to maintain the Latin Empire, the Villola chronicle explains how a tax on the mills of Bologna was imposed so that the city could raise money to wage battle, and the Chronicon Parmense enumerates the various material necessities required when supplying military forces.Footnote 98 Pietro Cantinelli states that the costs for maintaining mercenary forces in Forli amounted to twenty-six thousand florins.Footnote 99

As costly as war was, historians noted that its aftermath had its price as well. Money was often used to solidify peace treaties arranged between warring cities, and tributes offered to victorious cities could be paid in goods, such as the oil and wine offered to Venice on a yearly basis by the city Istria, or in cash.Footnote 100 The anonymous author of the Storie Pistorese explains that fines were imposed and lawsuits brought against the city of Florence to provide funding for reparations to Pistoia after it had been destroyed, while Buccio di Ranallo's chronicle lauds King Charles of Anjou, who agreed to pay for repairs to the region after the battle of Benevento.Footnote 101 The author includes a careful description of how land was parceled out following the battle, who documented the grants, and that money would be provided to rebuild the town.

Although the costs of war between cities was a major theme in the earlier histories and remained so through the mid-fourteenth century, it was the argument concerning the toll exacted by conflicts that took place within cities, in the form of factional disputes, that later historians took up with fervor. An early reference to the costs of factionalism appears in the Cronica Fiorentina compilata nel secolo xiii, with a description of the damages done by the Ghibellines in 1247. The anonymous author writes that “the Ghibellines destroyed the towers and palaces and all of the fortresses the Guelfs had, and all of the other things they made foul and polluted, and they forced women and young girls into great shame.”Footnote 102 By the middle of the next century, Giovanni di Durante provides a full description of how the Stinche prison was destroyed by the Donati faction during the struggle between the Black and White Guelfs, explaining that

the other Donati went to the Stinche of Florence and had a fire started at the door, and smashed it, and released all of the prisoners who were in this Stinche, and all of the prisoners, the many who were inside, came out, and then the others had the prisoners put it to flame, and they stole everything inside.Footnote 103

Dino Compagni's earlier fourteenth-century work provides multiple examples of factional destruction, explaining the city's duty to demolish homes of members from vying factions and the displeasure of the commoners if the homes were not completely razed.Footnote 104 Yet, the idea that factionalism had only negative effects on the material well-being of town inhabitants is somehow inverted in the work of Guglielmo Ventura, who explains that some citizens were not at peace with their fellow citizens because they were in great debt to their creditors, and therefore encouraged factional discord among others so as not to be obliged to pay those debts.Footnote 105

Finally, factional warfare could also separate individuals from their goods or disrupt their financial activities. Pietro Cantinelli describes how the Lambertuci were exiled from Bologna, and their homes destroyed in their absence.Footnote 106 The author of the Storie Pistorese explains how a fire set by the White Guelfs resulted in significant damage and loss for the cloth merchants of Florence, and the Chronicon Parmense reports that commercial activities in the city of Parma were interrupted due to concerns about the arrival of war.Footnote 107 When a town's communally owned goods were destroyed or damaged, the lives of its citizens were disrupted and, at times, even threatened. Moreover, the physical domination over the common spaces often stood as an indicator of who held power within these communities. As participatory government became more common in Italian cities, there was greater oversight and reportage by historians concerning how that same property was protected, managed, or mismanaged on behalf of town inhabitants.

Communal Resources and Responsibilities

In the years after 1300, Italian towns were increasingly ruled by a diverse group of inhabitants to include merchants and commoners working alongside traditional leaders from well-established noble families or the church hierarchy.Footnote 108 Naturally, as a greater proportion of the population gained access to the governing process, the actions they took in matters of monetary policy came under closer scrutiny. With greater access to the communal decision-making process and the expansion in the demographics of those who partook in town government, attention to the disposition of town funds, including their misuse through bribery or corruption, appears more frequently and with greater nuance in the later chronicles.

The most straightforward reference to the costs incurred by the towns are the sums given for city officials’ salaries, including those for the podestà and other town leaders, although the misdirection of funds more generally also appears. Guglielmo Ventura quotes the six-month salary of the podestà of Asti at 3,000 Astese lire, while the podestà of Ferrara received a sum of 3,000 Bolognese lire.Footnote 109 The Villola chronicle notes that the salaries of thirty-three town officials were paid in baskets of grain, an unpopular policy during years of famine.Footnote 110 Giovanni di Durante reports that the Duke of Athens was paid fifty gold florins a day to help the Florentines fight Pisa, but that he did not perform well in return for this sum.Footnote 111 Dino Compagni also cites several occasions when the town's money was used improperly, observing in one instance that the Guelf party knighted three young men with strong political connections who were then paid the money earned by “poor little women who work the spinning wheels,” therefore highlighting how the funds were misdirected.Footnote 112 Some chronicles criticize the misuse of funds by leaders other than their own, such as Philip of France who was condemned by two separate chroniclers, first for his misuse of French funds and then for his seizure of the assets of Italian bankers working in France in the year 1278.Footnote 113

The minting of coins was the most common monetary action taken by towns and was frequently cited in the chronicles. Mention of the minting of new currency appears in the Cronaca Pisana Roncinana, Jacob of Voragine's chronicle, the Chronichetta Lucchese, and in the works of Paolino Pieri, and Bonifacius de Morano, to name but a few.Footnote 114 Monetary equivalencies for these new coins are occasionally provided as well.Footnote 115 Not surprisingly, another common theme regarding municipal funds was the collection of taxes and tariffs within a town. Among those works which mention taxes are the Libro del Biadiaolo, the Chronicon Parmense, Buccio di Ranallo's Cronica Aquilana, and the memories of Simone della Tosa, who notes the collection of a gabelle in the context of his own business accounts.Footnote 116

Bribery and corruption are mentioned in the earlier chronicles, but not with the same sophistication as in later works.Footnote 117 Salimbene de Adam, writing in 1282, refers to bribery to criticize one of his superiors, and to extortion to chastise others.Footnote 118 Rolandino of Padua also notes how Ezzelino da Romano used bribery to increase his political support.Footnote 119 The Cronica Fiorentina (from 1297) alludes to witness tampering and the use of “pecunia corrocti,” and to the corruption of the Roman nobility.Footnote 120 However, the fullest and most nuanced recording of corruption and the use of bribery is by Dino Compagni, who begins his work by characterizing many of Florence's inhabitants as “rich from unlawful profits.” He makes numerous references to bribery and corruption throughout the work with specific types of corruption noted throughout (that is, selling justice, extortion, money for political support, misuse of city funds, receipt of both money and grain for political gain).Footnote 121 Misuse of city funds also appears in Durante (1345) with his criticism of the Donati, and becomes a major theme throughout the work of Giovanni Villani, particularly in the later chapters which address Villani's own era.Footnote 122 Reference to bribery and corruption in these later works signals not only attention to these specific ideas but also a larger notion that authors had the right to both characterize and criticize how money was used.

Famine, Scarcity, and Commodity Prices

Not surprisingly, historians evaluated and criticized the actions of communal leaders most severely when the needs of inhabitants were left unmet, and particularly during the periods of famine that visited Italian peninsula in the first half of the fourteenth century. Mention of famine and scarcity were found in most of the works in the repertoire, but some later histories posited a causal relationship between famine and scarcity, whether natural or human in origin, and the resulting effect on prices for commodities such as grain, salt, fruit, wine, and other foodstuffs.Footnote 123 The close association between famine, scarcity, and commodities pricing may stem from a belief, first alluded to in earlier histories and more fully articulated in later chronicles, that cities were in some ways responsible to promote material well-being among their inhabitants, or at least to provide an environment in which inhabitants could prosper materially. Two of the later chronicles, the Libro del Biadaiolo and the Chronicon Parmense, represent the fullest expression of expectations held by northern Italians that their towns would ensure access to the material goods they needed.

The works of Rolandino of Padua and Dino Compagni provide two examples among many in the repertoire of early attitudes concerning the material responsibilities of communities towards their inhabitants. Rolandino explains that material wealth is a condition of civilization, and states that there are “three things especially that adorn all cities and every place where people live: the beauty of the citizens, an abundance of wealth, and the handsomeness of its homes,” and goes on to accuse Ezzelino da Romano of denying these three things to the citizens of Padua.Footnote 124 Dino Compagni notes that the laws of Florence were created to protect the wealth of the commune, and that if town officials remained faithful to these rules, the populace would benefit greatly.Footnote 125 These two chronicles therefore present a view that towns should oversee the material well-being of their inhabitants, that material prosperity served as an indicator of a town's political health, that the deterioration of a town's material wealth was a sign of its decline.

Nowhere are the material expectations of town inhabitants more clearly expressed than in Domenico Lenzi's Libro del Biadaiolo, where a noble Florentine's disappointment in his town is fully expressed as Lenzi reports that he is heard grumbling: “here is a poorly managed city, that cannot even provide grain.”Footnote 126 Although mention of famine and want of grain is found in most of the chronicles, it is the main theme in the Libro del Biadaiolo, which dates to sometime in the 1340s. Throughout this work, structured as a day-to-day accounting of grain prices at Florence's Orsanmichele marketplace, Lenzi provides not only a record of the fluctuating costs of Florence's staple food, but also an in-depth view on the mechanics of scarcity with frequent reference to actions taken to maintain a constant flow of food, either by rationing, restricting hoarding, or prohibiting the places where grain could be resold.Footnote 127 Alongside the registration of grain prices, the author also chronicles some of the political events that take place Florence on the dates he records, and often makes a connection between these events and the prices he monitors. His heart-wrenching depiction of the evils of famine bring to life the suffering of the citizens in a way that was only alluded to in almost all of the earlier chronicles. The only other depiction of famine that comes close to Lenzi's empathetic portrayal is the almost gleeful reportage in the Fragmenta Historiae Pisanae of the death of Ugolino della Gherardesca, who was imprisoned in a tower with his family and left to die of starvation. The lengths that he and his family took when faced with such acute hunger were gruesome and appeared later in literary as well as historical texts.Footnote 128

The Chronicon Parmense, although it is viewed as much more than a history of prices in Parma, makes constant reference to the supply level and consequent pricing of many different types of foods, including salt, wine, fruit, grain, pigs, eggs, and meat, among other items. The chronicle also monitors the rise in the cost of wood or other material used for production, and at one point, noted that “wretches and poor women went out daily and cut down trees and destroyed homes in inhabited towns, to sell the wood.”Footnote 129 The chronicle not only reports on food costs, but uses the fluctuation in commodities pricing as a constant means to monitor the health of the city, as in the case of many of the later chronicles, including that of Buccio di Ranallo and the Villola chronicle.Footnote 130 For many historians, poor money management was a matter of communal interest with serious ethical implications.

Morality and the Material

Since the threat of scarcity and famine remained a constant in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century town life, historians naturally reflected upon the moral implications of how wealth was accumulated and distributed. The themes of abundance and excess appear periodically in the chronicle repertoire and signal a turn towards an ethical evaluation of the subject matter. Abundance is generally viewed as a positive characteristic of town life, indicating that the community is healthy, and in many cases, the inhabitants are virtuous. Excess is often coupled with the notion of waste or dissipation and is introduced especially when a chronicle author is hoping to criticize the material policies of a leader or group of people he dislikes.Footnote 131 Although these concerns are incipient within the repertoire of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century historical writings, it is a topic that takes on even greater importance starting in the second quarter of the fourteenth century.Footnote 132

Three early writers — Bonvesin da la Riva, Martin da Canal, and Riccobaldo of Ferrara — highlight the abundance of goods found in the cities they are chronicling. The greater part of Bonvesin da la Riva's De magnalibus Mediolani reports on the great wealth of goods found in Milan, including “grain, wine, vegetables, fruits, trees, hay, and all products, as everyone can see,” and he concludes that “you will find many men and women who are very advanced in age, and in the same way will find that families are very fertile and the population numerous, due to the abundance of all alimentary products that increase day by day, thanks to God.”Footnote 133 In a similar style, Martin da Canal introduces the city of Venice to his readers with claims that it is “filled with beauty and all good things; merchandise flows through this noble city like water through fountains,” and goes on to argue that “in this city, one can find an enormous amount of food, bread and wine, fowl and water birds, fresh and salted meats, and great fish from the sea or from the river; there are merchants from everywhere who come to buy and sell.”Footnote 134 Riccobaldo of Ferrara extols the natural wealth and resources found in Ferrara, and explains that the richness of the town's natural resources attracted good families from all of Italy to come and live there.Footnote 135 Despite the richness reported in these three works, it is important to note that there was a strong literary tradition of praise poetry for cities that had previously flourished in Italy and which was called by many names, including the Encomium Urbis, Carmina, Mirabilia Urbis, Laudationes Urbium, Descriptions Urbium, Laudes Civitates, or the Laudes Urbium, and that the work of Bonvesin da la Riva especially relies on this tradition in its description of the wealth found in Milan.Footnote 136 Later works, such as the Chronicon Parmense, are less exaggerated in their reports about abundance in their towns, which suggests that material goods held a different value in the works of these three earlier authors than in later chronicles.Footnote 137

The ethical flipside of abundance is, of course, excess, a theme which appears most often in works with strong moral overtones. Salimbene de Adam notes that abuse of power leads to greater access to material goods, and applies this personally to his former superior, Brother Elias, whom he charges with the desire to live excessively because of his position in the order.Footnote 138 The Chronica Fiorentina compilata nel secolo xiii reports that in 1138, Maestro Rinaldo preached against the vice of excess, albeit without approval from the church.Footnote 139 Giovanni di Durante also remarks upon the excess of the Duke of Athens, whose rule he consistently criticizes, noting that he owned a vase that he had made from gold and silver, and which valued nearly 30,000 gold florins.Footnote 140 Abundance and excess are found most frequently in works with a particular goal, whether promotional or critical, as historians wrestled with the implications of wealth and who controlled it.

Just as abundance and excess appear in the repertoire, so do the virtues of charity and generosity, although less often than the contrary vice of avarice. Salimbene addresses the value of charity in his chronicle, quoting the bible on the virtue and even equating charity with courtliness.Footnote 141 The anonymous author of the Chronicon Marchiae Tarvisinae et Lombardiae notes that generosity was indeed a value, so much so that Ezzelino da Romano feigned magnanimity to further his political aims.Footnote 142 Paolino Pieri describes Frederick I as “generous, virtuous, and gracious,” a characterization picked up by Villani a generation later.Footnote 143 Riccobaldo of Ferrara uses sarcasm to shame the Marquis Azzo, first calling him “generous,” then criticizing him for collecting extraneous taxes.Footnote 144 Domenico Lenzi praises the rich citizens of Florence for helping the poor during the famine of 1329, and the memoirs of Luca di Totto da Panzano describe a great feast thrown by the town of San Miniato to honor him and his descendans, although he does not mention generosity in particular.Footnote 145

References to avarice appear regularly in the repertoire as a means to chastise groups or individuals within the narrative. Salimbene de Adam and Jacob of Voragine, both of whom were members of the clergy and whose works are moral in nature, offer extended warnings on the dangers of avarice for the public good.Footnote 146 These values reappear in later chronicles where specific instances of greed are cited. Riccobaldo of Ferrara asserts that the Venetians who transport goods out of Ferrara are greedy, and Domenico Lenzi accuses the city of Siena of avarice because it does not care for its poor in times of famine.Footnote 147 On a personal level, the historian of Vicenza, Ferreto de Ferreti, accuses Charles of Anjou of greed in his conquest of northern Italy, and the author of the Chronicon Marchiae Tarvisinae et Lombardiae characterizes Ezzelino da Romano as a “greedy wolf.”Footnote 148 Although the twinned virtues and vices of abundance versus excess and charity versus greed speak most directly to the moral implications of wealth management, the willingness of historians to tie material goods to ethical concerns indicates just how heavily these questions weighed upon inhabitants of the medieval Italian peninsula. And of the historians writing during this period, few were more influential or quick to moralize than the Florentine merchant-historian Giovanni Villani, whose Nuova Cronica could be considered its own study of how Italians of the early fourteenth century understood wealth, money, and material goods.

Materialism in Giovanni Villani's Nuova Cronica

Giovanni Villani was born to a wealthy Florentine merchant family and spent much of his adult life travelling as a banker involved in the business of international commerce. His Nuova Cronica, which tells the story of Florence from the perspective of world history was first conceived on a trip he made to Rome in 1300 and written down in the 1320s and 30s, once he was able to settle more permanently in his home town.Footnote 149 As a man whose life's work revolved around money management, Villani's history is of great importance to understanding how material goods were viewed in Italy during the mid-fourteenth century, not only because they are mentioned so frequently in the Cronica, but also because the text subsequently served as a source and model for many of the historical works written throughout the Italian peninsula thereafter.Footnote 150 Citing every mention of materialism in Villani's chronicle would require a book in itself, so the chronicler's approach towards material goods will be merely summarized, then noteworthy sections indicated that merit the attention of future scholars.

Villani's work includes all the themes related to material goods found in the repertoire discussed above. Three things, however, can be said generally about Villani's approach towards material goods that differ from the repertoire as a whole: first, he tends to quantify the value of material goods rather than provide rich or extensive descriptions of them; second, he often uses material considerations to bolster the moral position he is putting forth in the chronicle; and finally, like his compatriot Dino Compagni, Villani fully explores the range of ways in which material goods, and money in particular, operate within the historical setting he describes. All three of these characteristics coincide with the more transactional rather than static approach towards material goods usually found in later chronicles. Not surprisingly, the earlier sections of Villani's work rely on the static depiction of material goods that would certainly have been found in the sources he used for this period. Many of the individuals Villani describes are characterized simply as “wealthy,” “very strong, affluent people of great wealth,” “rich and wise,” or even “cunning, malicious, and rich.”Footnote 151 Unlike abundance, wealth was not necessarily an indicator of moral superiority. Later references to wealth are at times downplayed, such as when the leader of the Black Guelf party, Corso Donati, is described as “a noble man skilled in battle, not of excessive wealth.”Footnote 152

Villani's overall approach to the function of material goods changes, however, as he relies more heavily on contemporary sources. Examples listed below, including the extensive documentation of Florence's yearly expenses found in Book Twelve, Chapter 93 and the detailed depiction of periods of famine in the city, support the idea that Villani's work presented an expectation that material goods and money should circulate in the town rather than remain in the domain of a powerful few. One scene, in particular, demonstrates that Villani's approach towards historical events, at least in some part, could be viewed in terms of credits and debits, much akin to Latini's transactional approach in the Tresor. Chapter 35 from Book Eight describes how a Florentine rebel, as he was facing judgment for his crimes, asked his co-conspirator as they came before the judge, “Where are we going now?” to which his friend replied, “To pay a debt left to us by our fathers.”Footnote 153 This transactional presentation of the effects of Florence's immediate history is supported elsewhere in Villani's work though his continuous attention to the credits and debits accrued by the city.

Descriptions of feasts and festivals in Villani's chronicle display a remarkable lack of attention to luxury items in comparison with other works in the repertoire. Material goods, including new clothes made of rich fabrics, are occasionally mentioned to establish the extraordinary nature of a feast or festival, but the descriptions pale in comparison with the effusive imagery found in other chronicles.Footnote 154 In the realm of public entertainment, however, Villani also reports that in 1322, a Sienese musician was able to ring the bells of Florence at full peal, a feat which none of the twelve men before him had been able to do in the city for a period of seventeen years. For this service the musician was paid three hundred gold florins.Footnote 155 Villani's portrayal of the event did not include a rich description of the sound of the bells, but rather a quantification of the particulars of the event to underscore its meaning. If anything, Villani's descriptions of special feasts and events are structured to emphasize the quantifiable value of the event rather than the luxurious details.

Villani's treatment of luxury items to signal or confer special status on persons or situations does not vary greatly from the approach found in other chronicles. Villani observes that luxury materials such as marble, gold, and porphyry are used in the building of churches, that jewels are brought as a gift to a wedding, and that the pope was clothed in rich garments at his burial.Footnote 156 In one instance, Villani's didactic purposes are exposed as he provides an opulent picture of the wealth and beauty of the city of Poggibonsi, but explains that it was their pride and arrogance that caused their destruction at the hands of the Florentines.Footnote 157

Villani often uses clothing styles in his work to add a moral dimension to the political program he puts forth in the narrative. Although at times Villani remains neutral in his recounting of clothing styles, such as when he describes the distinctive apparel of the Lombards, his bias becomes clear elsewhere, as when he speaks of the modest dress of the Florentines in the age of the primo popolo (around 1265), or when he explains that the French were “nobly adorned” or that the forces of King Charles of Anjou, one of Villani's heroes, were outfitted in sumptuous armor of gold and silver.Footnote 158 Villani also critiques the clothing styles of his own day, preferring instead the “beautiful, noble, and honest” styles similar to the togas worn during the time of the Romans.Footnote 159

Villani pays special attention to civic works in the Cronica, especially since he begins his work with the founding of the city and so therefore documents how and when many of the city's landmarks were first built, including the fountains and waterworks, the gates and city districts, local fortresses, and city walls.Footnote 160 Villani notes specifically that the city was at peace during the year 1294, and so undertook improvements to the Church of Santa Maria del Fiore, adorning it with marble and carved sculptures.Footnote 161 In the year 1321, Villani makes a connection between the end of King Robert's rule in Florence, which had lasted eight and one half years, and the initiation of a series of new city works, which Villani himself helped to execute. “And I the writer,” he explains

since I was an official of the city along with other honorable citizens undertaking the construction of these walls, first decided that the towers should measure two hundred by two hundred arm-lengths; and in the same way it was ordered that the barbacani [protrusions in the upper stories of buildings] or confessi, next to the wall and on the outside of the trench, should be begun, for the strength and beauty of the city, and this is how everything else went along.Footnote 162

This connection between the Florentine's self-rule and the undertaking of public projects adds a moral dimension to the material reality of new civic construction. In 1337, Villani recounts that the construction of a “grand and magnificent palazzo” was begun and specifies which taxes were collected for the completion of this work, thereby creating a link between the benefits of new construction in the city and the costs required to attain them.Footnote 163

As in most of the chronicles, destruction, reparations, and the costs of war and factionalism loom large in Villani's chronicle. Destruction is not quantified in the earlier sections of the work that rely on older sources, but as the Cronica continues and Villani relies more on eyewitness testimony and contemporary sources, the author is able to offer more precision concerning the nature and extent of damages. Villani, for example, notes that the walls of Cremona were breeched by the Milanese in 1321, and that all the goods that remained there were confiscated, and gives a monetary value (200,000 Genoese pounds) to the losses sustained by Genoese exiles in the year 1322.Footnote 164 As in other histories from after 1300, the losses due to factionalism are also chronicled and monetary sums assigned to those losses as well, such as the goods valued at 60,000 gold lire lost during the factional violence in Florence in 1342.Footnote 165 The costs of war include payment for soldiers, or the price, in monetary terms, of peace settlements and at times a mention of the taxes or fines that were imposed to make those payments.Footnote 166