Introduction

Gastropod molluscs have uniquely transcended the ecological barriers separating marine, freshwater and terrestial ecosystems, and are common and diverse in all of these ecosystems (Strong et al., Reference Strong, Gargominy, Ponder and Bouchet2008, Reference Strong, Colgan, Healy, Lydeard, Ponder and Glaubrecht2011; Webb, Reference Webb2012). Specific lineages have radiated and now dominate in marine fringe environments (rocky-shores, estuaries, mangroves and mudflats), including the Neritomorpha, Littorinoidea and Cerithioidea (Frey & Vermeij, Reference Frey and Vermeij2008; Reid et al., Reference Reid, Dyal, Lozouet, Glaubrecht and Williams2008; Frey, Reference Frey2010; Strong et al., Reference Strong, Colgan, Healy, Lydeard, Ponder and Glaubrecht2011). Several other more limited gastropod incursions into estuarine ecosystems include those by the Buccinoidea, Muricoidea and Eupulmonata (Klussmann-Kolb et al., Reference Klussmann-Kolb, Dinapoli, Kuhn, Streit and Albrecht2008). Of the Muricoidea, rapinine snails represent the most notable estuarine forays, with the genus Indothais (Claremont, Vermeij, Williams & Reid, Reference Claremont, Vermeij, Williams and Reid2013) having a particular affinity for an estuarine existence. This genus constitutes 12 species distributed from the Arabian Gulf to Taiwan, with seven found in India and South-east Asia (Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei and Indonesia), and four in north-western Borneo, Indothais gradata (Jonas, 1846), I. javanica (Philippi, 1848), I. malayensis (Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996) and I. rufotincta (Tan & Sigurdsson, 1996) (Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996b; Claremont et al., Reference Claremont, Vermeij, Williams and Reid2013). However, despite a reasonable understanding of the geographic distributions and phylogenetic relationships of Indothais snails (Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996b; Claremont et al., Reference Claremont, Vermeij, Williams and Reid2013), ecological information is largely lacking (see Marshall, Reference Marshall2009). Their niche occupation and relative penetration of hyposaline waters is currently imprecisely reported, with all the Bornean species referred to generally as inhabiting littoral zones, rocks, muddy surfaces and mangrove trees (Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996b).

Indothais gradata is ubiquitous and abundant in the Brunei Bay and Estuarine System (BES, Brunei Darussalam, Borneo; Marshall, Reference Marshall2009; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Proum, Hossain, Adam, Lim and Santos2016). Functionally, it is the only large and significant intertidal predatory whelk in the Sungai Brunei estuary (Marshall, Reference Marshall2009; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Proum, Hossain, Adam, Lim and Santos2016). The persistence of this species in this physically and biotically highly variable system is underlain by its plasticity in physiology, feeding and reproduction (Marshall, Reference Marshall2009; Proum et al., Reference Proum, Harley, Steele and Marshall2017). Individuals can downregulate metabolism, facilitating behavioural isolation from the outside environmental conditions, and thereby avoiding exposure to extremes in pH and salinity, and polluted water (Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Santos, Leung and Chak2008; Proum et al., Reference Proum, Santos, Lim and Marshall2016, Reference Proum, Harley, Steele and Marshall2017). Flexible habitat use and feeding in this species is indicated by the migration of snails from concrete or wooden pillars, where they feed on intertidal barnacles, to nearby mudbanks, following ephemeral colonization of these banks by an energetically more lucrative sediment infaunal food source (Arcuatula mussels or Umbonium snails; Marshall, Reference Marshall2009; DJM pers. obs). The reproductive cycle and mating of I. gradata appears to synchronize with food availability, increasing the efficiency of energy conversion from food to gonad and egg production (Marshall, Reference Marshall2009).

This study was stimulated by the observation of shell morphological variation in local Indothais snails, suggesting possible cohabiting congeners. Initial assessment revealed the occurrence in the Brunei (Muara district) marine waters of three species (I. gradata, I. malayensis and I. rufotincta) and two variants of I. gradata (four morphotypes). First, we aimed to determine the morphological and genetic variation of the four snail morphotypes and to assess their phylogenetic relationships (see Claremont et al., Reference Claremont, Vermeij, Williams and Reid2013). Then, we investigated niche separation of the morphotypes, and interrelated niche features with evolutionary patterns. The niche investigation was facilitated by snails inhabiting a well-studied salinity gradient, extending from the open seawater (33 psu) on the South China Sea coastline to Sungai Brunei (Figure 1; <5 psu; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Santos, Leung and Chak2008, Reference Marshall, Abdelhady, Teck Wah, Mustapha, Godeke, De Silva and Hall-Spencer2019; Proum et al., Reference Proum, Santos, Lim and Marshall2018). An assumption was that discrete distributions along this salinity gradient would indicate fundamental niche differences of the species. By relating ecology and phylogeny, we aimed to better understand the pattern and mechanism of speciation in Indothais snails.

Fig. 1. Map showing localities in the South China Sea, inner Brunei Bay, and Sungai Brunei. 1, Sungai Damuan (4.868713, 114.910759); 2, Sungai Kedayan (4.886159, 114.937194); 3, Pintu Malim (4.872369, 114.955755); 4, Sungai Bunga (4.917065, 115.007045); 5, Sungai Besar/Chermin (4.931811, 115.016691); 6, Pulau Pepatan (4.917879, 115.045679); 7, Mentiri (4.951011, 115.027038); 8, Pulau Bedukang (4.976687, 115.060573); 9, Sungai Serasa (5.006826, 115.064774); 10, Pantai Tungku (4.973252, 114.871132). Colour coding refers to the water chemistry as follows: pink, Sungai Brunei (salinity = 3.6–26.9, pH = 5.8–8.1; aragonite undersaturation), blue, the Brunei Bay (salinity = 19.6–31.2, pH = 7.7–8.3) and grey, the South China Sea (salinities typically range between 20.2–33.2, pH = 7.9–8.5).

Materials and methods

Snail collection and morphological species

We undertook to study specimens from a collection of more than 500 Indothais snails taken from 10 localities along the Brunei-Muara coastline (Sungai Brunei, Brunei Bay and South China Sea) over 14 years (2005–2019; Figure 1). Most of the snails were collected for other studies (Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Santos, Leung and Chak2008, Reference Marshall, Proum, Hossain, Adam, Lim and Santos2016; Marshall, Reference Marshall2009; Proum et al., Reference Proum, Santos, Lim and Marshall2016, Reference Proum, Harley, Steele and Marshall2017). Specimens were sourced from both muddy sediments and hard surfaces, such as rocks, mangrove trunks and pneumatophores, and wooden and concrete pilings around stilt houses in water-villages. Snails were stored in 80% ethanol at UBD (Wetlab, Environmental and Life Sciences), though many specimens were later kept dry. Originally, all snails were identified and labelled as I. gradata, including date, habitat and locality. Previously, a single record of I. rufotincta was reported from Pulau Chemin, Brunei Bay (Brunei Museum of Natural History, BMNH; Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996b). Reference specimens of the species examined in the present study are lodged in the Universiti Brunei Darussalam Museum (UBDM). Shells, external soft tissues (penis and tentacles) and egg cases of the morphotypes were described. Morphological species followed the descriptions of Tan & Sigurdsson (Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996b).

DNA sequencing

Sampling of genetic variation among the morphotypes, including the two forms of I. gradata and locality differences, was undertaken using 19 freshly-collected snails (Supplementary Table S1). Specimens were washed, preserved in 90% ethanol and stored at −20°C. A QIAGEN DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit was used for DNA extraction. The genomic DNA sample was sent to a service provider for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and DNA sequencing. Three mitochondrial genes, cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI), 12S ribosomal RNA (12S rRNA) and 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA), and one nuclear gene, 28S ribosomal RNA (28S rRNA), were amplified using previously described PCR protocols (Claremont et al., Reference Claremont, Vermeij, Williams and Reid2013) and primers (Barco et al., Reference Barco, Claremont, Reid, Houart, Bouchet, Williams, Cruaud, Couloux and Oliverio2010). With the same primers, PCR products were sequenced in both directions using an Applied Biosystems BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and Applied Biosystems Genetic Analyzer platform. MEGA X (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher, Li, Knyaz and Tamura2018) was used to assemble forward and reverse sequences, and to remove primer regions. The resulting consensus sequences were deposited in the GenBank database with accession numbers MT896359–MT896377 for COI, MT896834–MT896852 for 12S rRNA, MT896853–MT896871 for 16S rRNA, and MT896872–MT896890 for 28S rRNA. Species identification was confirmed by matching COI sequences with GenBank sequences via Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) available in the database.

Multiple alignment was carried out using MAFFT in GUIDANCE2 (Sela et al., Reference Sela, Ashkenazy, Katoh and Pupko2015). Rapana bezoar (Linnaeus, 1767) sequences from a previous study (Barco et al., Reference Barco, Claremont, Reid, Houart, Bouchet, Williams, Cruaud, Couloux and Oliverio2010), with GenBank accession numbers FN677421 (COI), FN677376 (12S rRNA), FN677438 (16S rRNA) and FN677476 (28S rRNA), were included as outgroups. MEGA X was used to remove any column with missing data at both ends of the alignment and to remove a few internal columns with gaps. Thus, this study analysed 658, 547, 669 and 1417 bp of COI, 12S rRNA, 16S rRNA and 28S rRNA sequences, respectively. The four genes were combined to produce a concatenated dataset, and pairwise genetic distances were calculated based on Kimura 2-parameter model using MEGA X. Nucleotide diversity (π) was calculated using DnaSP 6 (Rozas et al., Reference Rozas, Ferrer-Mata, Sanchez-Delbarrio, Guirao-Rico, Librado, Ramos-Onsins and Sanchez-Gracia2017).

MrBayes 3.2 was used for Bayesian phylogenetic inference using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method (Ronquist et al., Reference Ronquist, Teslenko, Van Der Mark, Ayres, Darling, Höhna, Larget, Liu, Suchard and Huelsenbeck2012). For each gene, the best-fit model of nucleotide substitution was selected using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) in jModelTest 2 (Darriba et al., Reference Darriba, Taboada, Doallo and Posada2012). The best-fit model for COI and 12S was a Generalized Time Reversible model with a gamma distributed parameter (GTR + G), whereas for 16S rRNA and 28S rRNA the best-fit was a Generalized Time Reversible model with invariable sites (GTR + I). Bayesian inference was performed for each gene in two independent runs. In each run, 1,000,000 generations were sampled every 500 generations, resulting in a total of 2000 trees with a burn-in of 25%. Bayesian analysis was similarly performed on the concatenated dataset with the parameters unlinked across the four gene partitions. Convergence of the two independent runs was supported by the average standard deviation of split frequencies (<0.01), potential scale reduction factor (1.00) and effective sample size (>100). Phylogenetic analysis was repeated with a Maximum likelihood algorithm for each gene and for the concatenated dataset using PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al., Reference Guindon, Dufayard, Lefort, Anisimova, Hordijk and Gascuel2010). The best-fit model was selected using AIC by Smart Model Selection (SMS) available in PhyML 3.0. The best-fit models for COI, 12S rRNA, 16S rRNA and 28S rRNA were GTR + G, GTR + G, GTR + I and GTR + G + I, respectively, whereas for the concatenated dataset, the best-fit model was GTR + G + I. A bootstrap test was performed with 1000 replicates. Bayesian and Maximum likelihood trees were visualized using FigTree 1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree).

Coastal distribution and niche differentiation

Three marine water bodies have been identified in the Brunei/Muara region on the basis of differences in salinity, pH and carbonate undersaturation (Figure 1, Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Santos, Leung and Chak2008, Reference Marshall, Abdelhady, Teck Wah, Mustapha, Godeke, De Silva and Hall-Spencer2019; Proum et al., Reference Proum, Santos, Lim and Marshall2018; Hossain et al., Reference Hossain, Marshall and Hall-Spencer2019), the Sungai Brunei (salinity = 3.6–26.9, pH = 5.8–8.1), the Brunei Bay (salinity = 19.6–31.2, pH = 7.7–8.3) and the South China Sea (salinities typically range between 20.2–33.2, and pH between 7.9–8.5). Reduced pH conditions are created largely (though not solely) by allochthonous acidified water discharge into these marine water bodies from surrounding pyritic formations (Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Santos, Leung and Chak2008, Reference Marshall, Abdelhady, Teck Wah, Mustapha, Godeke, De Silva and Hall-Spencer2019). Although drainage of acidified water from acid sulphate soils directly into the South China Sea can occur via rivulets and submarine infiltration along sandy beaches, the greatest localized effects occur on natural rocky intertidal zones (direct seepage) and is negligible on artificial seawalls (Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Abdelhady, Teck Wah, Mustapha, Godeke, De Silva and Hall-Spencer2019). We mapped the occurrence of the species at each of the 10 study localities along the observed salinity gradient, extending the length of the Brunei/Muara coastline, and recorded intertidal distributions and habitat occupation.

Results

Morphological study

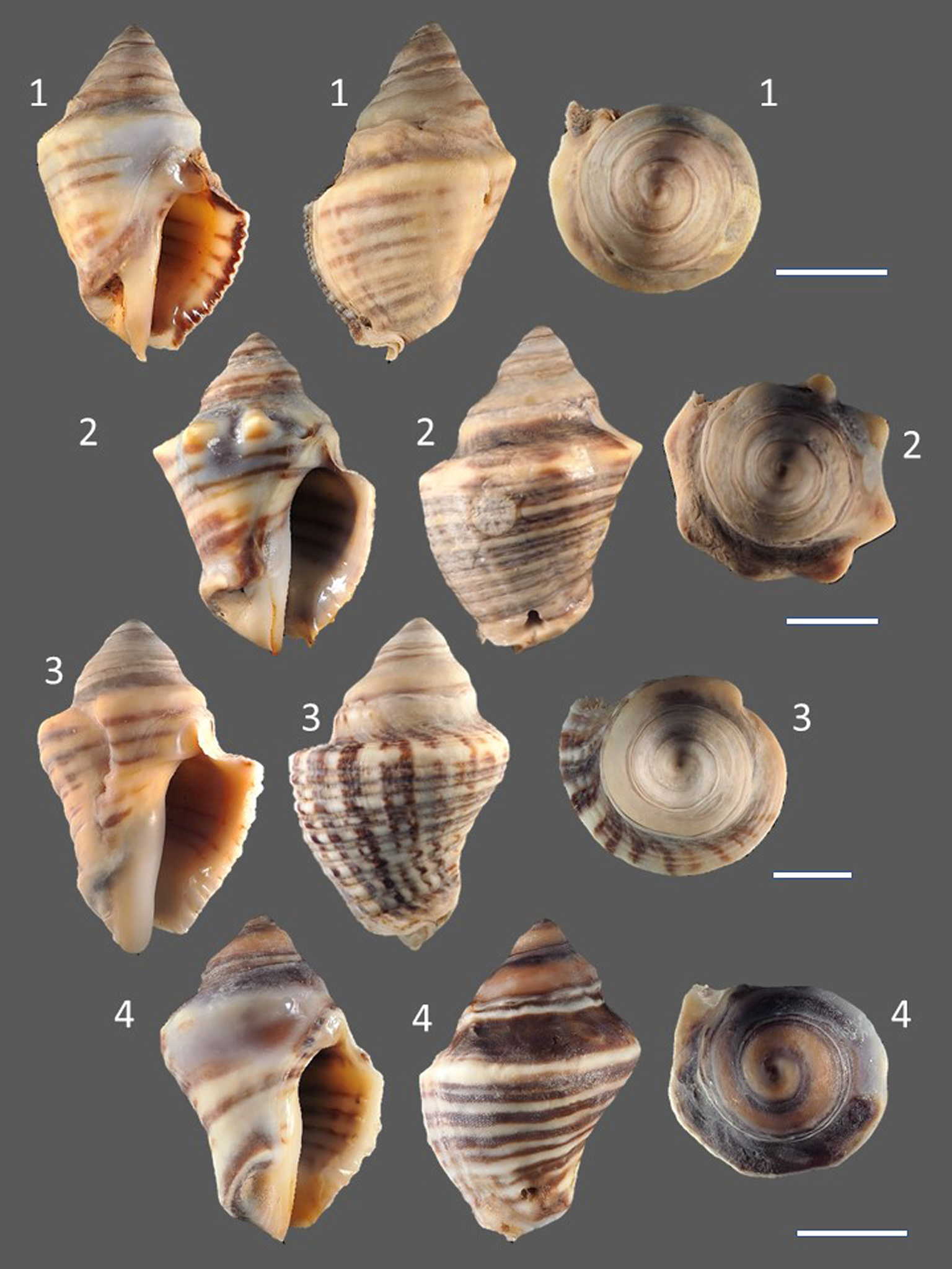

The morphological study suggested that the snail collection comprises I. gradata, I. rufotincta and I. malayensis. The shells of I. gradata are highly variable in size, shape and development of protuberances from the carina (Figure 2). The suture separating the last whorl from the penultimate whorl is directly below the carina of the penultimate whorl, and the side of the shell of the last whorl angled directly from the carina towards the anterior canal (~30 degrees), creating a triangular-shaped aperture (Figure 2). Two forms of Indothais gradata are distinguished. A relatively dark-shelled morph is characterized by the colour of the internal aperture (Figure 2), and a light morph (Figure 3) possesses a cream inner apertural colour, a thicker and rounder outer lip, and a well-developed siphonal tube. The light form typically shows greater shell erosion. The lip and siphonal tube development is suggested to characterize older, non-growing shells, and is seen in all three congeners (Tan & Siggurdson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a; Figures 2–5). The egg cases of I. gradata are consistent with previous descriptions (Figure 6; Tan & Siggurdson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a). These are triangular with longitudinal bands at each vertex, extending from the base to the opening (apex) of the egg case. The egg cases are relatively squat and curved upwards near the apex (Figure 6).

Fig. 2. Shells of Indothais gradata (non-corroded). Snail #1 shows protuberances on all whorls and snail #2 shows smaller and more numerous protuberances. Snails #3 and #4 show typical dark form used in genetic study (dark apertures and absence of narrowing of the siphonal canal). Arrows indicate the last whorl arising from the carina of the penultimate whorl. Aperture is triangular-shaped. Siphonal canal is seen in Snail #1. Numbers refer to the same individual snail. Scale bars = 10 mm.

Fig. 3. Shells of Indothais gradata (corroded). Apertural features of all shells are indicative of the light form. Numbers refer to the same individual snail. Scale bars = 10 mm.

Fig. 4. Shells of Indothais malayensis. Arrows show the separation between the carina and the penultimate whorl, and the bar indicates the effect of this on the aperture shape. Numbers refer to the same individual snail. Subsequent to DNA analysis this species is considered I. javanica. Scale bars = 10 mm.

Fig. 5. Shells of Indothais rufotincta. Red arrows indicate the distinctive knobs on the last whorl. Numbers refer to the same individual snail. Scale bars = 10 mm.

Fig. 6. Eggs cases were consistent with descriptions for Indothais gradata and I. malayensis (Tan & Siggurdson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996b). Both types of egg case were triangular with three longitudinal support bands at the vertices of the triangle (blue arrows), extending from the base to the opening (apex) of the egg case. The egg cases of gradata were relatively squat, and more sharply curved towards the apex (seen best in right photograph). Scale bars = 3 mm.

In I. malayensis, the suture separating the last whorl from the penultimate whorl occurs 3–4 chords below the penultimate carina, below a vertical wall (relative to the shell axis) (Figure 4). In I. malayensis, the side of the last whorl below the carina is parallel to the shell axis (see Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a), creating an ovate aperture (Figure 5). The soft tissue shows great individual variation in penis length and structure, as well as in tentacle pigmentation, and there is no brown pigment ring previously used to distinguish I. javanica from I. malayensis (Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a). Furthermore, the egg cases are triangular and relatively elongated, with support bands at vertices, matching the description for I. malayensis (Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a). They are not folded upwards as in I. gradata, and differ from the egg cases of I. javanica, described as not triangular and lacking the supporting bands (Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a).

Indothais rufotincta is easily distinguished from the above species by the presence of reddish brown axial knobs on the whorls (Figure 5; Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a). The head and proboscis of live specimens of this species are uniquely pinkish. Unlike I. gradata, the shells of I. malayensis and I. rufotincta lack carina extensions in the material examined.

DNA sequencing

Three mitochondrial genes (COI, 12S rRNA and 16S rRNA) and one nuclear gene (28S rRNA) from 19 specimens were successfully sequenced. In contrast to the morphological study, the species were identified by BLAST results as I. javanica, I. gradata and I. rufotincta, as their COI sequences were 99% similar to the GenBank sequences of these species in a previous study (Claremont et al., Reference Claremont, Reid and Williams2012). The four samples identified as I. javanica were slightly less similar (97%) to the COI sequence of I. malayensis reported in the same study (Claremont et al., Reference Claremont, Reid and Williams2012). Neighbour-joining analysis supported the identification of the four samples as I. javanica and not I. malayensis using either COI or 16S rRNA. However, 12S rRNA or 28S rRNA could not differentiate the samples into either species (Supplementary Figure S1).

All four Bayesian trees using single-gene datasets (COI, 12S rRNA, 16S rRNA or 28S rRNA) showed I. gradata, I. javanica and I. rufotincta formed three distinct, well-supported clades (trees not shown). Similarly, the representative Bayesian tree using concatenated-gene dataset (COI + 12S rRNA + 16S rRNA + 28S rRNA) showed these three distinct, well-supported clades (Figure 7). However, none of the trees showed any distinct separation between the light and dark forms of I. gradata. Thus, these two forms cannot be considered as genetically different groups. All Maximum likelihood trees using single-gene and concatenated-gene datasets showed similar results (trees not shown but bootstrap values are shown in Figure 7).

Fig. 7. Representative Bayesian tree of Indothais species based on concatenated-gene analysis of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI), 12S rRNA, 16S rRNA and 28S rRNA. Numbers shown at node are posterior probability for the Bayesian analysis and bootstrap percentage value for the Maximum likelihood analysis based on the concatenated-gene dataset. Rapana bezoar is used as an outgroup.

Pairwise genetic distances differed within and between the species (Supplementary Table S2). Indothais gradata and I. javanica are closely related, as is indicated by their low mean genetic distance (5.08 ± 0.06%). This relationship is also seen in the phylogenetic tree with the two species forming sister groups (Figure 7). Based on the mean genetic distances, I. rufotincta is more closely related to I. javanica (6.31 ± 0.04%) than to I. gradata (6.84 ± 0.08%). Comparison within species showed the mean genetic distance was highest in I. gradata (mean 0.22 ± 0.17%; values ranging from 0–0.43%), higher in I. javanica (0.14 ± 0.05%; 0–0.21%) and lowest in I. rufotincta (0.07 ± 0.04%; 0–0.15%). This indicates greatest genetic variation in I. gradata and least variation in I. rufotincta. Genetic variation was also assessed by measuring nucleotide diversity and a similar trend was observed (Table 1).

Table 1. Nucleotide diversity (π) based on single-gene and concatenated-gene analyses

Coastal distribution and niche differentiation

Following precedence of the molecular study, the three species distributed along the Brunei coastline are I. javanica, I. gradata and I. rufotincta. Although their distributions overlapped in the Brunei Bay, only I. rufotincta occurred in the ocean sea, fully marine, coastal waters (South China Sea), whereas I. javanica and I. gradata extended deep into the estuary (Sungai Brunei) (Figure 8). Indothais gradata was most abundant at any locality, and was most ubiquitous, occurring at all nine estuarine localities. Abundance determination for I. gradata was not undertaken as this was complicated by the spatial and habitat variability of this species (but see Marshall, Reference Marshall2009). For I. rufotincta, fewer than 10 individuals were found on any occasion at any locality, and I. javanica occurred in patches up to 15/m2 at Sungai Kedayan. Indothais gradata colonized hard substrata (wooden constructions, logs, concrete and natural rocky surfaces) and soft benthic sediments (Figure 8; Supplementary Figure S2), whereas I. javanica snails occurred on all hard surfaces and I. rufotincta was locally confined to rocky surfaces (Figure 8).

Fig. 8. Coastal distributions and niche differentiation of the species.

At all localities, all three species were found to feed on barnacles and probably other sessile organisms (mussels and polychaete worms). Indothais gradata also showed generalistic, opportunistic feeding behaviour, by feeding on ephemeral muddy sediment colonizers, Umbonium costatum and Arcuatula senhousia (formerly Musculista senhousia), and Sphaeroma terebrans tubeworms in washed-up logs (Marshall, Reference Marshall2009; Hossain & Bamber, Reference Hossain and Bamber2013; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Proum, Hossain, Adam, Lim and Santos2016). Where the snail species co-occurred at Pulau Bedukang (Oyster Rocks outcrop) or at Sungai Kedayan, I. gradata exclusively dominated the mid-shore zone (~0.5–1.5 m Chart Datum), with I. javanica and I. rufotincta occurring lower on the shore (~ below 0.5 m CD).

Discussion

Although four morphological Indothais species have been reported from the north-western Bornean coastline (Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996b), our molecular study shows that only three (I. gradata, I. javanica and I. rufotincta) occur in Brunei waters. However, this molecular finding conflicts with our morphological species determinations, in that the egg capsule structure better matches the description for I. malayensis, than for I. javanica (Figure 3; Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996b). This questions whether these taxa were confused by Claremont et al. (Reference Claremont, Vermeij, Williams and Reid2013), which served as a basis for our molecular analysis, or whether the diagnostic characters used to discriminate the species are unreliable (Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a). Importantly and consistent with our findings, Claremont et al. (Reference Claremont, Vermeij, Williams and Reid2013) found that the sequence divergence between I. javanica and I. malayensis was too low to discriminate these species, and relied on morphological descriptions in their analysis. We found that some genes did not discriminate these species (see Supplementary Figure S1). In view of these morphological and molecular inconsistencies, the validity of these two species deserves further investigation. In the meantime and based on our molecular findings, we refer to I. javanica as the operative species in Brunei waters. Indothais malayensis is reported from Sarawak and Sabah, on either side of Brunei, however, we show an extension of the distribution of I. javanica in north-western Borneo (Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996b). The I. gradata morphotypes (dark or light forms) did not differ genetically, or with respect to habitat or location. Their shell morphological variation can thus be attributed to developmental and/or environmental influences; we concur with Tan & Sigurdsson (Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996b) that the light form likely represents older individuals, which in our case were often exposed for longer to shell-eroding acidified water.

Intraspecific pairwise genetic distances and nucleotide diversity indicate that genetic variation is lowest in I. rufotincta and highest in I. gradata. Nucleotide diversity generally relates to mutation rate and effective population size. The relatively high nucleotide diversity of I. gradata, which is far more abundant than the other species, aligns with its capacity to establish relatively large populations. The success of this species in highly variable estuarine environments must partly relate to its physiological plasticity, specifically its capacity to regulate energy metabolism and adjust feeding and reproduction in ways appropriate to changes in the environmental conditions (Marshall, Reference Marshall2009; Proum et al., Reference Proum, Harley, Steele and Marshall2017; Marshall & McQuaid, Reference Marshall and McQuaid2020). A population with a larger and more variable gene pool has a greater potential for local adaptation and habitat diversification. From a phylogenetic perspective, I. gradata and I. javanica are more closely related to each other than to their common ancestor, I. rufotincta. The tolerance by I. rufotincta of salinity below that typically found in open-sea water suggests that this species made an initial estuarine incursion, which was followed by speciation and deeper penetration into estuaries by I. javanica and I. gradata. Claremont et al. (Reference Claremont, Vermeij, Williams and Reid2013) suggest that this speciation occurred during the Miocene period.

The observed pattern of speciation was found to coincide well with the distributions of the species along the salinity gradient of the Brunei estuarine system (P = 0.1; Figures 7 and 8). Indothais rufotincta exists alone in the full salinity open-sea water, whereas I. gradata and I. javanica only occur in the more variable and hyposaline estuarine conditions (Proum et al., Reference Proum, Santos, Lim and Marshall2018). The distribution of I. rufotincta was restricted to waters having an operational salinity of above 19 psu, whereas the other species occurred where salinities fell to as low as 3.6 psu (Proum et al., Reference Proum, Santos, Lim and Marshall2018). Previous studies have found that I. gradata snails in Malaysia and Singapore are associated with freshwater-influenced environments such as estuaries or mangroves, rather than with open-sea shorelines (Tan, Reference Tan1999; Mohamat-Yusuff et al., Reference Mohamat-Yusuff, Zulkifli, Ismail, Harino, Yusoff and Arai2010). The Miocene origin of this species coincides with the geological formation of regional river basins (including the Sungai Brunei), though the ecology has until recently (Last Glacial Maximum) been significantly influenced by sea level change and the persistence of Sundaland (Morley et al., Reference Morley, Back, Van Rensbergen, Crevello and Lambiase2003; Bird et al., Reference Bird, Taylor and Hunt2005; Hossain et al., Reference Hossain, Marshall and Venkatramanan2014). Although several brackish-water and closely-related rapanine muricids have been recorded from Miocene deposits in Brunei and adjoining northern Sarawak (see Raven, Reference Raven2016), these do not include Indothais snails. Gastropods are typically poor systemic osmoregulators, suggesting that salinity tolerance by I. gradata and I. javanica relates to intracellular osmoregulation (Proum et al., Reference Proum, Harley, Steele and Marshall2017). Behavioural isolation and metabolic depression of I. gradata also facilitate the avoidance of extreme ionic and pH exposure (Proum et al., Reference Proum, Harley, Steele and Marshall2017). The javanica/gradata clade could have arisen from divergent selection (local adaptation) to sustain populations experiencing low salinity conditions, a capacity apparently limited in the ancestral rufotincta and preventing its deeper penetration into estuaries. Salinity tolerance determinations would, however, be useful to confirm this hypothesis for a differential physiological dispensation of these species.

In addition to different estuarine distributions, the species differed in tidal distributions and habitat use. Biotic factors (competition and predation) typically dictate mid to low shore distributions, and these best explain the spatial separation of the species where they cohabit (hard substrata at Bedukang and Sungai Kedayan). Indothais gradata occurred at a higher intertidal level than the other two species. Although I. rufotincta and I. javanica may be relatively intolerant of air exposure, the zone occupied by I. gradata could also coincide with maximal barnacle colonization, which would imply competitive exclusion of the other two species. Furthermore, I. gradata also occurred at a lower intertidal level in muddy sediments, below the level occupied by I. rufotincta and I. javanica (Supplementary Figure S2). In some cases, migration to these sediments was seen by snails tracking more lucrative ephemeral food sources, though inactive individuals were often found buried and presumably aestivating in the mud (Supplementary Figure S2, Marshall, Reference Marshall2009). Although I. javanica and I. rufotincta sometimes inhabited the interface between hard surfaces and muddy sediments, they were never found to feed on sediment-dwelling organisms. Likewise, benthic sediment feeding of malayensis/javanica snails should not be inferred in cases where snails might be found navigating muddy areas between mangrove trees, pneumatophores, or other hard surface habitats (this study; Tan & Sigurdsson, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996a, Reference Tan and Sigurdsson1996b).

In summary, whereas all three species feed on hard substratum sessile animals (barnacles, bivalves and polychaetes), only I. gradata feeds on organisms in the muddy sediment. Such niche expansion is underlain by complex ecological and evolutionary processes, including the likely absence of soft substratum competitors (see Marshall & Convey, Reference Marshall and Convey2004). Our observations support the hypothesis that the ancestral I. rufotincta is constrained to plesiomorphic feeding on hard rocky surfaces in relatively high salinity waters, that I. javanica expands its hard substratum feeding to both rock and wooden surfaces, and tolerates more reduced salinities, and that I. gradata tolerates low salinity waters and feeds on both hard and soft substratum prey. The generalist feeding behaviour and flexibility of metabolism and reproduction, which are underpinned by genetic variability, should benefit I. gradata under future environmental change (Monaco et al., Reference Monaco, Bradshaw, Booth, Gillanders, Schoeman and Nagelkerken2020). Further observations of habitat utilization and feeding of I. javanica and I. rufotincta from other regions would be useful to confirm this hypothesis. Likewise, there is a need to resolve the morphological/molecular inconsistency observed here for I. javanica and I. malayensis, and to assess niche differentiation between these species, should they exist. The observed patterns and mechanisms of speciation, nonetheless, improve our understanding of gastropod evolutionary incursions into tropical estuarine ecosystems.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S002531542100014X

Acknowledgements

David Relex offered valuable assistance during the execution of this study. DJM is supported by UBD grant UBD/RSCH/1.4/FIBF(b)/2018/016 and HT is supported by UBD grant UBD/RSCH/1.13/FICBF(b)/2020/018. We thank anonymous referees for useful comments.