China is feeling nostalgic. Romantic reminders of the past are everywhere – an endless wave of costume dramas, fake historical trinkets, cosplaying subcultures, and kitschy themed restaurants. Observers have attributed this sentiment to a variety of factors: a search for authenticity, government promoted nationalism, the commercialization of an idealized past, or the loneliness of a generation that has been left rootless by rapid social transformation.Footnote 2 Each of these explanations will satisfy part of the phenomenon, but on its own, no one covers it completely. Chinese nostalgia is of course many things, but one thing that it is not is new – Confucius himself famously pined for the glories of a golden age, and Chinese writers have long used the past to speak metaphorically about the present. What changes are the vehicles that people use to express nostalgia, and how images of the past are shaped by evolving forces like nationalism, consumerism, or social anxiety. It seems instinctively true that nostalgic images would reinforce each other – that romantic depictions of the past in museums, film, or historically-themed tourist attractions would interact with government initiatives like Xi Jinping's “Great Rejuvenation” campaign.Footnote 3

This article examines nostalgia in China's marketplace – both nostalgia for business and the business of nostalgia – with a particular focus on food industries. Since the economic reforms of the 1980s, China's commercial nostalgia has appeared in different forms: popular literature, government campaigns to promote “old brands,” and product advertising. Although the timing and images of these three waves of nostalgic construction overlap, the latter two represent opposing views about what is worth preserving and why. We discuss these distinct approaches to authenticity and novelty as heritage and retro nostalgia. Turning to food, we see a product that is uniquely suited to nostalgia marketing, but also an example of how nostalgia conforms to the needs and opportunities of a specific sector. From the early revival of classic restaurants and local specialties, China's food industries have aspired to reach an ever-larger market, expanding through franchises and branded products. Responding to new opportunities, China's classic food brands have continued to embrace nostalgia, but their emphasis has shifted from authenticity to novelty, from scarcity to replicability, and from heritage to retro.

What is nostalgia?

Nostalgia is not a single phenomenon. It can be a sharp, personal sense of loss, or a vague longing for the beauty, simplicity, or excitement associated with another age. It may recall individual or collective experiences, or an entirely imagined distant past.Footnote 4 Nostalgia is often felt socially, growing from a sense of value, esthetic, or belonging that is shared with real or virtual peers.Footnote 5 Nostalgia can be externally woven into public images and discourse, and like any sense of shared value, the emotional pull of nostalgia is to some degree a cultural projection, and the nostalgic community an imagined one. This is why nostalgia changes with the times, the particular past that we pine for, the reasons why we miss it, and what we long for in its passing.

Among these many fault lines, manifestations of nostalgia divide across the importance of historical accuracy. An event like the sinking of the Titanic will be remembered very differently in a museum exhibit and in a cosplaying subculture – the former will prize fidelity to actual events and mundane artifacts, whereas the latter might be more drawn to the stylized romance of the era, or the fictionalized events depicted in the 1997 James Cameron blockbuster.Footnote 6 Each type of nostalgia creates value from a curated telling of events, but views differently the importance of accuracy, and more broadly how sentiment relates to historical facts. Similar to Ryoko Nakano's discussion of heritage in this issue, the former uses the authority of expertise to shape facts into a definitive narrative of historical events, often one that is designed to provoke a sense of respect, gratitude, anger, or disgust.Footnote 7 The latter is less concerned with any pretense of factual authenticity, and instead content to approach the past as an archive of symbols to be mixed and matched as needed. This is sometimes done to humorous effect, a tongue-in-cheek use of the past that “mines and mocks the past simultaneously” in what Lowenthal refers to as “postmodern ironic nostalgia.”Footnote 8 But it can also be used for more serious subjects like historical fiction that creatively arranges historical symbols and facts in order to provoke an emotional response. Even when the two approaches share images and events, they work from very different logic about the relation between fact and meaning. In this paper, we will refer to them as heritage and retro nostalgia, respectively.Footnote 9

Rebirth of China's business nostalgia

China's business nostalgia emerged from a broader rehabilitation of the pre-revolutionary past. Chinese intellectuals had already spent much of the twentieth century scrutinizing the past for value and rejecting with increasing vehemence manifestations of “backward” culture or thinking. The purge of history reached its extreme in the 1966 campaign to “destroy the four olds” 破四旧, a call to obliterate the art, architecture, and ideas of the pre-revolutionary society. With historical interpretation forced through the narrow analytical keyhole of dialectical materialism, much was left publicly unremembered. As the political changes of the Deng Xiaoping era allowed the portrayal of history to gradually look past staid themes of heroic revolutionaries and class struggle, cities like Shanghai and Tianjin initiated campaigns to preserve their old buildings, including ones that represented these cities' colonial and bourgeois past.Footnote 10 The gradual reappearance of historical topics in the press and new general-interest outlets confirmed where the new boundaries were to be drawn.Footnote 11

With this trend came a wave of popular writing on old businesses. Ranging from semi-fictionalized stories to reminiscences by former customers, shop hands, and owners (including the locally collected oral histories published as “literary and historical materials” 文史资料), these publications celebrated local business figures, as well as customs and products that had all but disappeared. One of the trendsetting publications, 1986's book Famous Old Brands of Beijing, was followed closely by similar titles about Harbin, Tianjin, Guangzhou, and Ji'nan, and even a song listing the names of famous establishments.Footnote 12 It was also joined by the work of professional historians, culminating in a ten-volume study of old businesses edited by eminent Shandong University historian Kong Lingren.Footnote 13

The portrayal of old businesses was heavily romanticized – gauzy recollections of products familiar and exotic, as well as supposedly bygone values of craftsmanship and honesty. A short article on the history of Beijing medicine shop Tongrentang 同仁堂 highlighted the three centuries of knowledge that was written into the company's proprietary recipes.Footnote 14 Another on willow comb maker Buhengshun 卜恒顺 emphasized the company's unbroken heritage of family ownership. Written by the ninth-generation descendant of the original late Ming founder, the piece praised his company's use of rare woods that were both beautiful and medicinal. Other paeans to tradition portrayed Shanghai eyeglass maker Wuliangcun 无良村as constantly seeking ways to improve production, yet never skimping on quality, while confectioner Xinghualou 杏花楼 sourced the finest ingredients from around the country for its mooncakes. One article even cited Mao Zedong praising these old companies by name: “China has some very good handicrafts, they last forever. Knives and scissors from Wangmazi 王麻子 and Zhangxiaoquan 张小泉 – these will last for ten thousand years!”Footnote 15

Depiction of how these businesses fared under socialism was mixed, with open criticism reserved for the period of the Cultural Revolution. A short piece on the Kangding 庚鼎 medicine shop in Chengdu praised the 1956 institution of “joint management” 合营 with the state, relating in the language of orthodox Marxism how the change had “harmonized the relations of capital and labor.”Footnote 16 Describing his family's comb business, Bu Zhongkuan explained that “in the old society, shop owners, factory managers, and workers were all oppressed,” and went on to note that after Buhengshun was absorbed into a production and sales cooperative in 1954, he was given a management position, and moreover selected as a youth delegate to Beijing.Footnote 17 The history of medicine shop Tongrentang was an especially sensitive subject. That large business had initially been a success story of joint management, expanding rapidly with state resources. Twelfth generation owner Le Song 乐松 became an icon of the new patriotic capitalism and was for a time the Vice Mayor of Beijing. But the shop was twice targeted in the Cultural Revolution, resulting in the destruction of countless treasures, and likely hastening the death of Le Song himself at the young age of 60. Later accounts were careful to divide the positive and negative aspects of this history, separating the gains made under early socialism from the “ten years of catastrophe” 十年浩劫, and noting that Le himself was posthumously rehabilitated in 1978 when his cremated remains were moved to the Babaoshan 八宝山 cemetery for communist heroes.Footnote 18

If some of these early accounts read like advertisements, it is because they were meant to. Melding their patina of nostalgia to contemporary sensibilities, each of these businesses was actively positioning itself for revival in the new era. This is why they included among their time-tested values a tradition of innovation. Building on centuries of careful experimentation, Tongrentang was also shown to be actively updating its production techniques, adding new products, and investing in a dedicated research institute. Others touted ambitious plans to expand retail outlets and product offerings, complementing premium handcrafted products with new cheaper everyday lines, but always emphasizing that change was the essence of their tradition.Footnote 19 Taken together, this wave of writing represented a rehabilitation of China's commercial past. Quite unlike the emphasis on capitalist perversity that one might have seen in publications just a few years earlier, small businesses were now the champions and embodiment of China's commercial tradition – honesty, craftsmanship, entrepreneurship, and innovation.

“Old Brand Revitalization Project”

But despite the optimism around the return of time-tested values, it was becoming clear that these old businesses were in fact poorly equipped to compete in the new era. According to a 1993 census by China's Department of Commerce, only 1,600 businesses remained of the 16,000 that were estimated to have existed in 1956. By the end of the 1990s, 20% of this remainder had already gone bankrupt, and another 70% were in financial trouble. Only 10% were large and strong enough to ensure survival.Footnote 20 Facing competition from a new influx of multinational enterprises (MNEs), older businesses stood by helpless as glamorous foreign brands like Sony and Nike took the Chinese market by storm, at least as aspirational purchases.Footnote 21 Local governments provided some help by linking old businesses to local tourism, building specialty shopping streets like Beijing's Dashilan 大栅栏, or subsidizing iconic shops to remain in scenic tourist areas.Footnote 22

But beyond this sort of temporary ringfencing, the success of MNEs also prompted examination of why China's old businesses were uncompetitive. A series of events and publications came up with similar answers: the so-called “joint management” of enterprises had in many cases pushed out the original owners, and along with them, managerial skill and responsibility. Businesses that relied on traditional or artisanal methods faced difficulty with upscaling and efficiency, leaving them unable to face competition from cheaper lookalikes. The most often cited problem was a lack of innovation. Hu Shiwei 胡沛立, manager of Beijing hotpot chain Donglaishun 东来顺 laid the blame squarely on the enterprises themselves, asking how a business like Buyingzhai 步瀛斋 could survive making traditional cloth shoes when there was simply no demand for its product. Speaking from inside Beijing's first McDonald's, Hu observed that the there was “nothing special” about the food, yet customers queued up daily because the restaurant constantly updated its consumer experience.Footnote 23 The government response echoed this sentiment. As 350-year-old scissors maker Wangmazi struggled to avoid bankruptcy, Lu Renbo 陆刃波, head of the State Council Development Institute criticized the company's resistance to innovation, coolly remarking that “when I was a child, Wangmazi sold scissors. Years later, it's still doing the same old thing.”Footnote 24

So why bother trying to save them? Despite their problems, these old companies did have a unique asset – their brand. The crisis of old business came at a crucial moment in the transition from state to private ownership. Non-productive state-owned enterprises were being allowed to go bankrupt or be sold off, a process that involved establishing the value of the company.Footnote 25 But even when saddled with debt, old enterprises still had the value of their name. When Wangmazi finally did apply to declare bankruptcy early in 2003, the ensuing legal battle for ownership of the brand showed that name recognition was among the company's most valuable remaining assets.Footnote 26 The decimation of one old business after another threatened to sell off ownership of these assets at fire-sale rates. Saving these heritage brands meant promoting the unique value of China's commercial traditions.Footnote 27

The government's answer was the “old brand revitalization project” 振兴老字号工程. Initiated by the Department of Commerce in 2006, this project awarded select businesses the title of “China Time-Honored Brand” 中华老字号 (Zhonghua laozihao, hereafter laozihao), along with a plaque that they could display in their premises, and a logo to feature in their advertising. Designation as a laozihao was a mark of distinction, based on satisfying seven selection criteria. In addition to having been founded before the commercial reforms of 1956, businesses chosen as laozihao needed to (1) own their own trademark, (2) produce a unique product, craft, or service, (3) carry on the tradition of “good Chinese business practices,” (4) have a uniquely Chinese or local flavor, historical or cultural value, and a good reputation, (5) be held by mainland, Taiwan, or Hong Kong capital stock, and (6) be commercially sustainable. The result was that the program not only protected old businesses, it also filtered them to retain only those with desirable qualities, a process that also rewrote the narrative of China's commercial history.

The program embraced the call to reform. Through support for official events and university research, it provided a platform for the call to innovate laozihao. The near death of Wangmazi was raised repeatedly as a call for laozihao to stop living in the past, and update their services, image, and products. (The scissors maker did ultimately find salvation by moving into other products, such as high-quality cooking knives, which it promotes as being uniquely suited to Chinese techniques.) Even as laozihao were being gazetted as heritage, they were also encouraged to adopt new product designs, materials, and production techniques.

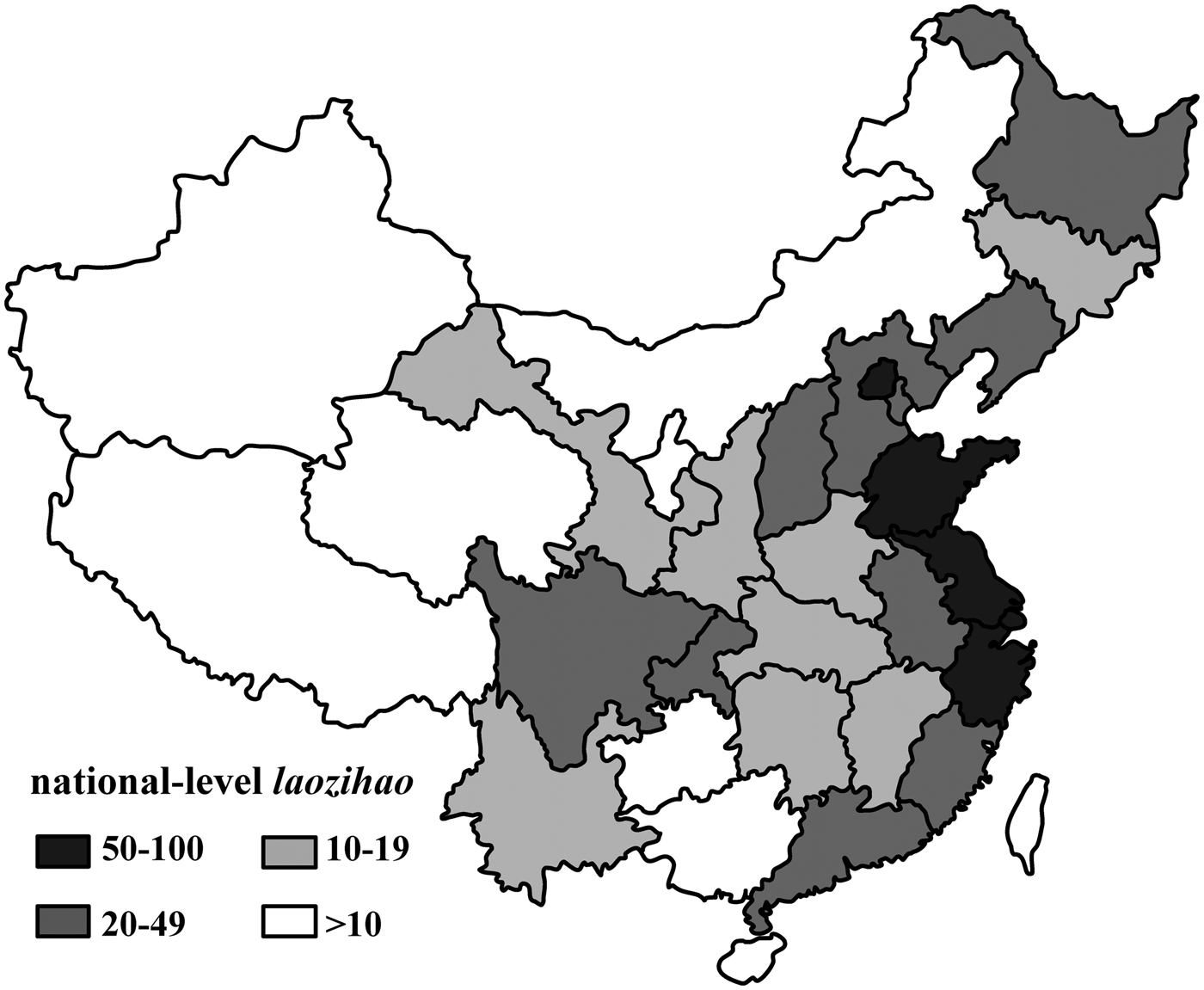

But its primary purpose was publicity and recognition. The first round of induction in 2006 recognized 429 national-level laozihao, concentrated largely in the old commercial cities and a handful of coastal provinces (Fig. 1). Over the subsequent decade, the program created designations of laozihao at provincial and city levels, and a second round of induction that expanded the number of national-level laozihao to 1,128.Footnote 28 It was anticipated that the best of these would develop into national or globally-known brands.Footnote 29 As a marketing tool, the program was a significant success: in 2011, 89.1% of laozihao managers replied that the designation had been “helpful” or “very helpful” in expanding their sales.Footnote 30 Over the next decade, this basic remit remained essentially unchanged. In preparation for a 10-year review of the program, representatives from a handful of national-level departments consulted with business leaders for ways to further energize the initiative. In 2017, sixteen of these departments jointly released the “Opinion concerning the reform and creative development of laozihao,” which extolled businesses to catch up with changing consumer demand and new marketing opportunities, especially in what was called the “internet+” space, but otherwise reiterated themes and slogans that had already been expressed over the first decade of the program.Footnote 31

Figure 1. Provincial dispersal of laozihao. Source: Map created by author using data at http://zhlaozihao.mofcom.gov.cn/searchEntps.do?method=andiqudownload#.

Like many heritage programs, the “old brand revitalization project” enshrines laozihao in a virtual museum, but does little to define them. Laozihao designation is thus a platform for many different sorts of value. It is a brand for specific retailers, supports tourism and traditional crafts,Footnote 32 and can be made to connect to a wide variety of other assumed values, such as environmental sustainability, that speak to less to the past than to anxieties about the present.Footnote 33 This catholicity of meaning allows different interests to coalesce around laozihao, but it also reflects ambiguity in what heritage programs are meant to achieve. This loose understanding of value is also seen in heritage initiatives like Intangible Cultural Heritage 非物质文化遗产 (ICH).Footnote 34 Laozihao and ICH are similar in many ways – both are state administered programs to preserve, protect, and promote enterprises, products, and crafts that are endangered by the march of time – indeed, many laozihao enterprises produce items using traditional techniques that are themselves gazetted as ICH,Footnote 35 and some even refer to laozihao businesses themselves as China's “intangible cultural heritage.”Footnote 36 But this just shows how the meaning of heritage can be misperceived. The value of ICH is in fact based on very specific criteria: the place of a particular craft or artistic form in the life of a community, rather than the sublimity of craft itself.Footnote 37 Nevertheless, even those tasked with collecting ICH often have a vague sense of what they are looking for, and many perceive it simply as a repository of elite craft, with entry into the registry marking a global recognition of being among the world's best.Footnote 38

The result is that heritage programs like laozihao can give the impression of simultaneously looking backward and forward, unsure of what exactly they value or seek to enshrine. The apparent unanimity of official backing masks the fact that these programs have many agendas, both inside and outside the government.Footnote 39 As a result, the specific appeal to nostalgia becomes muddled, the meaning of heritage designation a broad statement of generic values.

“Creative nostalgia”

It is no secret that nostalgia sells. Beginning in the early 1980s, the fields of psychology and marketing began trying to understand why – researching how different life circumstances prime an emotional connection to the past, and how consumers experience memory, divided by gender, income, education, and most importantly, age.Footnote 40 Known as “nostalgia marketing,” this sort of research began to make its impact in China in the mid-2000s, just around the time the old brand revitalization project was being instituted.Footnote 41 Even at this early stage, it was becoming clear that sepia images of tradition were not enough to win over younger consumers. When asked by 2005 CCTV program “Brand China” to personify their image of roast duck restaurant Quanjude 全聚德, managers described a person wearing a business suit and traveling by airplane. In contrast, customers imagined a figure wearing a traditional tangzhuang 唐装 jacket and seated in a horse cart.Footnote 42 Companies needed to take control over the meaning they wanted their heritage to convey.

It was the “creative” approach to nostalgia that would provide the alchemy to transform older brands from dowdy to classic.Footnote 43 Also known as retro, “creative nostalgia” combines past and present elements to evoke historical themes while still signaling novelty and contemporaneity. Rather than simply recycling an old image or brand, this approach updates a historical referent with a self-consciously new, humorous message – hence Lowenthal's moniker of “postmodern ironic nostalgia.” Footnote 44 Creative nostalgia is distinct from the common tactic of simply inventing a heritage, since part of the appeal is that viewers are in on the joke.Footnote 45 Employed with skill, creative nostalgia strikes a balance between past and present that maintains the emotional tie to the brand, while keeping the product itself relevant.Footnote 46

One example of successful creative nostalgia was the campaign mounted by laozihao cosmetics maker Pechoin 百雀羚 (founded 1931). Realizing that their products appealed primarily to older women, the company decided in 2008 to reinvent its image to reach the free-spending consumers born in the 1980s and 1990s (commonly known as the “after 80” and “after 90” generations). Its new campaigns followed three types: one was a series of fairly typical cosmetics advertisements featuring famous spokesmodels or the promise of high-quality ingredients. A second was straight nostalgia, consisting of classic images from the 1930s. A third followed the path of “retro” branding, creatively mixing historical and contemporary themes. The artwork in Pechoin's humorous “1931” campaign is an example of the third sort. Playfully evoking old Shanghai in a series of heavily stylized street scenes, the ad follows a mysterious woman, who is shown to be on an assassination mission. Scrolling through the scenes (vertically, since the artwork is specifically tailored to viewing on smartphones), we see glamorous and recognizable figures, and some humorous ones (a boy asking his parents for a picture with Batman is told “silly, Batman hasn't been invented yet”), as well as brief glimpses of classic billboards for Pechoin itself. In the final frame, the woman successfully dispatches her victim, who is shown to be “time,” explaining to the viewer, “it's my mission to defeat time.” While critics have noted that ad has not significantly impacted sales, at over 30 million views, Pechoin has very likely gotten more than what they wanted from the campaign.Footnote 47

Retro marketing is hardly new. Advertisers saw the humor of pairing historical figures with modern products long before the term “creative nostalgia” ever made its way into Chinese marketing literature. Nor is it possible to discern in retro advertising anything like an “end of nostalgia.” Heritage and retro nostalgia continue to visibly coexist in China's marketplace, along with a great swath of generalized nostalgic imagery in shop decor, product packaging, and advertisements. In this larger picture, commercialized nostalgia is as varied as it is ubiquitous.

Nevertheless, when set against the heritage approach of the old brand revitalization project, the prominence of retro branding in the Chinese marketplace raises two key points. The first is that this commercial use of creative nostalgia is fundamentally different from the instinct to preserve historically relevant businesses or products by sheltering them from change. The second is that the appeal of creative nostalgia itself suggests that heritage accreditation of authenticity is itself not always a significant attraction for consumers. Ads like Pechoin's 1931 campaign make no pretense of historical accuracy – just the opposite, they go out of their way to distance themselves from it, to the point of neglecting to even mention their laozihao credentials. The purpose here is irony, and in a sense, the target is the pretensions of heritage nostalgia itself.

Food nostalgia – authenticity versus novelty

Looking beyond this broad outline of nostalgia for businesses, brands, and products, it is time to delve down into specifics by looking at how these trends are realized in food, a sector that includes both branded restaurants, and packaged food items like sauces, pickles, and cooking wine. We can begin by thinking about what makes China's food nostalgia unique.

To begin, food pairs naturally with nostalgia. Food itself evokes visceral memories, both real and imagined. Chinese literature often features culinary memories as a metaphor for simpler or happier times.Footnote 48 Older consumers return to the foods of their youth, feeding the resurgence of iconic brands like White Rabbit Candy 白兔糖. China's dining sector has responded with a wave of nostalgia restaurants themed around romanticized historical settings – a recreated Song dynasty shopping street, the Qing imperial court, the early Republic, or the 1960s, each with period decor, and costumed staff.Footnote 49 Second is that food is one industry in which being “classical” is a distinct commercial advantage. While laozihao makers of scissors or eyeglasses might be hard-pressed to compete against better and cheaper modern manufactures, the opposite is true in sectors like food and traditional medicine, where real or imagined history is a meaningful asset.Footnote 50 Not surprisingly, food enterprises dominate the laozihao registry, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the total. The final piece is the revolution of China's food industry itself, notably the rise of national franchising and chain restaurants. This transformation has not only vastly increased the value of food brands, it also shifted the selling point of historical enterprises from scarcity and authenticity to a replicable nostalgic experience.

Among the earliest enterprises to revive in the reform era, heritage restaurants initially emphasized the continuity of classic traditions, flavors, and service. Founded in the late Qing, and once counted among the city's “eight great restaurants” 八大楼, Beijing's Taifenglou 泰丰楼 had hosted the city's political elite for decades before ceasing operation in 1952. In the late 1970s, the restaurant began making preparations to reopen, reportedly at the personal recommendation of Sun Yat-sen's widow, Song Qingling 宋庆龄. The years-long process prized more than anything else fidelity to the restaurant's heyday. The previous manager was called in to oversee the recreation of the dishes, personally researching 200 menu items and consulting an outside committee of “gourmets” to vouch for the authenticity of the tastes, as well as for the old standards of service.Footnote 51 Other historical restaurants emerged as shrines to their own past: showcasing artifacts, calligraphy, and photographs, as well as stories featuring the tastes enjoyed by past patrons. A pamphlet from Nanjiing's Maxiangxing 马祥兴 recounts the popular tale of wartime collaborator Wang Jingwei 汪精卫 breaking curfew to procure the restaurant's signature duck dish.Footnote 52 A memoir of Beijing's Fangshan 仿膳 credits the restaurant's survival to support from Premier Zhou Enlai 周恩来, who frequently stopped by during his walks in Beihai Park.Footnote 53 Diners need not have been famous: stories of Taifenglou's 1984 reopening mention that among the diners was a group of friends who had eaten there exactly 40 years earlier.Footnote 54 Combined with food, such details establish an intimate sense of simulated community. One can scarcely imagine ordering the Maxiangxing duck and not wondering whether Wang Jingwei's gamble was worth it. And there is an unmistakable appeal to visiting one of Zhou Enlai's favorite restaurants, and toasting his memory over the same dish of pea sprouts the Premier himself once enjoyed.

But these restaurants could not escape the pull of novelty. Even the ultra-traditional Taifenglou learned early on the value of celebrating change within clearly set parameters: welcoming new chefs to its kitchen, and adding new items to the menu. Like the early revival of laozihao, classic enterprises balanced old and new by portraying thoughtful innovation as the heart of their tradition. Qingdao's Chunhelou 春和楼 wielded its authority as an iconic standard-bearer of Shandong cuisine to adapt its menus with tastes from Shanghai and Ningbo. Here the restaurant's laozihao designation helped it to lay claim to the mantle of authenticity, allowing Chunhelou to begin setting up new branches beyond its original location, in the cause of carrying forward the spirit of Shandong cuisine even as it sought to define it.Footnote 55

The move to retro advertising represents a late stage in the embrace of novelty, one that pokes fun at heritage, but does not abandon it entirely. Like Pechoin, laozihao drink maker Wanglaoji 王老吉 has used creative nostalgia to energize its advertising strategy. Aiming to distinguish its medicinal tea within a market flooded with other sweet drinks, Wanglaoji produced the humorous animated flash short “Wanglaoji through time” 穿越古今王老吉.Footnote 56 Circulated on the popular Tencent film app, “Wanglaoji through time” draws freely on romantic images of the past, showing in cartoon form Qing-era founder Wang Zebang 王泽邦 combining medicinal herbs to produce the miraculous concoction that is sold today. The video bridges past and future on numerous levels: images of historical figures paying tribute to the founder, the evolution of the trademark over generations, and the contemporary emergence of Wanglaoji as one of China's best-known food brands. Other ads in the series show Wang Zebang bridging time to present the drink to modern-day office workers who have been done in by the contemporary excesses of career stress and an unhealthy diet of snacks. Functionally, the short pioneers a new marketing platform to sell a 200-year-old product, and to launch new ones, such as “1828” brand milk tea, named after the year of the company's founding.

Like the experience of China's heritage brands more broadly, the shifting interaction of tradition and novelty in the marketing of food enterprises guides decisions about what can be updated and what is worth preserving, and more fundamentally about the meaning of heritage itself. While the food sector follows the overall shift away from the single parameter of authenticity, the speed and direction of this change is driven by several unique factors, including consumer tastes, and the specific needs of the industry. Like Pechoin's “1931” campaign, “Wanglaoji through time” highlights a signature product, but what it is really selling is the myth and persona of a brand. Other well-known food makers have built on recognition of a flagship product by branching out into new offerings. Shanghai's well-known White Rabbit Candy now offers flavored milk, ice cream, and even a scent, which comes packaged in a cellophane tube to look like a giant piece of candy.

Something similar is also seen in restaurant dining, where the food itself is only part of the attraction. Noting that China's free-spending consumers are increasingly content to approximate the experience of a famous restaurant with a branded outlet or mass-produced frozen takeaway, Jin Feng explains that China's anxious middle-class has shifted its priorities from conspicuous consumption of scarce material goods to a search for collectible experiences.Footnote 57 Many of those who do visit the original location of a famous restaurant do so not as diners but as tourists: less interested in the food than in the selfie, which they immediately crop, edit, and slap on to a social media feed. At one level, this phenomenon recreates the divide between the logic of laozihao and ICH heritagization, since diners are increasingly less interested in the objective goal of authentic taste than the subjective experience of food in culture. And it is hardly unique to China. Criticizing the heritagization of gastronomy, Marco Romagnoli notes that “The tourist does not necessarily need to understand all of the heritage constructs behind the art of the Neapolitan pizzaiuolo and the reasons behind its patrimonialization. Instead (s)he wants to live a ‘unique’ experience thanks to eating or tasting a ‘traditional’ food and following an ‘authentic’ social practice recognized by UNESCO.”Footnote 58

The elision of nostalgic messages between product and lifestyle drives the prominence of food in local tourism marketing.Footnote 59 The Chinese tourism industry has long recognized and capitalized the importance of food – as early as the 1980s, the Sichuan provincial government was supporting culinary training and contests in order to build up the spicy local cuisine as a tourist attraction.Footnote 60 Decades later, tourists to Sichuan's capital city of Chengdu cited cuisine as one of the main memories they took away from their visit.Footnote 61 Beyond external tourists, revival of landmarks like Guangdong's Western restaurant Taipingguan 太平官 also drive consumption with the return of locally known and beloved sights, tastes, and smells.Footnote 62 Food tourism drives the proliferation of historic “food streets.” Designed as pedestrian districts, food streets include tourist markers for well-known restaurants, signage explaining local dishes, preplanned routes for diners to travel, and artistic representations related to the food culture. Such streets invariably feature at least some nod to historical elements, but with enough glitzy novelty to draw in the crowds. Tourist meccas like Beijing's Gulou 鼓楼 district, Harbin's Zhongyang Street (中央大街, former Kitaiskaya ulitsa), and “Foreigner Street” 洋人街 in Yunnan's western city of Dali each build ambiance around restored and repurposed historical architecture. Yet in the spirit of retro branding, these historical locations are themselves often fronted by multilevel McDonald's and Starbucks outlets, icons of globalization that aim neither to stand out nor to blend in. Rather, like the Dali McDonald's which trades its usual signage for a traditional wooden signboard carved with an image of the golden arches, they creatively adapt their well-known branding to their location.

Branded nostalgia in the franchise age

China's food market is exploding, in both size and variety. With rising wealth allowing Chinese households to spend more on food away from home,Footnote 63 spending on China's food and beverage industry (餐饮业) grew by 480% from 1999 to 2008, from 320 to 1,540 billion yuan. The change was even more striking in cities like Beijing, where the value of the industry grew from 8.1 to 107 billion yuan or 1,320% over these same years.Footnote 64 Besides spending more on dining, urban consumers face ever more choices for where and how to do so. China's food scene has been shaped by a steady turnover of new fads, tastes, concerns, and retail experiences: the advent of Western fast food, rise of supermarket shopping, food safety scandals, and most recently, proliferation of online ordering and ratings platforms. The affinity between food and lifestyle adds new elements to how people choose where and what to eat.

But even as shoppers are increasingly drawn to food brands, the value of the brand is moving away from the consumer. This is particularly true for franchises – instant restaurants that pop up with supply chains, recognizable tastes, and branding fully formed. Franchise and chain outlets more than doubled in number between 2010 and 2019, and are expected to grow further as a proportion of the entire restaurant sector.Footnote 65 Investors have poured money into chains that promise access to a national market, buying up recognizable names like Jiaheyipin 嘉和一品 and Dio Coffee 迪欧咖啡. Others like braised duck chain Zhouheiya 周黑鸭 and hot pot restaurant Haidilao 海底捞 have raised immense sums by listing on public exchanges in Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Separating the value of the company from the cash flow of day-to-day operations, investors will flock to buy a stake in companies solely on the promise of future growth. Despite a long history of losing money, Luckin 瑞幸 Coffee based its IPO on the promise that its online and delivery platforms would make Starbucks obsolete. Franchises attract investors the same way: by promising to deliver the newest taste, food fashion, or consumer experience.Footnote 66

Responding to the intensification of novelty, and the culinary Taylorism of the franchise age, some laozihao food enterprises have embraced a model of mass-market heritage and replicable nostalgia. George Ritzer's idea of “McDonaldization” is precisely this push to quality control through uniformity – and it characterizes franchises at all price points, and all levels of cultural aspiration, including those that aspire to mass produce and mass market the classic culinary experience of a heritage enterprise.Footnote 67 The Hangzhou Zhiweiguan 知味观 restaurant is an example of an especially ambitious expansion of a laozihao enterprise. Starting in the late 1990s, this 1913 restaurant aggressively built an empire of chain outlets, and a central kitchen that sells vacuum packed and frozen snacks, dumplings, and fried dishes online and in supermarkets across the country.Footnote 68

Others followed suit, only to find that expansion runs the risk of alienating a loyal base. Having listed in Shenzhen in 2007, roast duck restaurant Quanjude expanded too quickly, and failed to maintain quality across its new outlets. For this, the restaurant has been punished doubly by poor online reviews and a falling stock price. National growth also conflicts with the sense of ownership that people feel for local tastes and iconic businesses. Local governments have legally challenged attempts by outsiders to trademark the names of signature dishes like Sichuan spicy hotpot 麻辣烫 and Jinhua 金华 cured ham.Footnote 69 The sense of local ownership is equally deep for laozihao enterprises, which are iconic fixtures of the urban landscape, and the literal food on people's tables. The 2006 sale of laozihao Churin 秋林, maker of Harbin's distinct smoked pork sausage and Russian bread, to Wenzhou-owned Heilongjiang Benma Group 黑龙江奔马集团 prompted a distinct sense of loss among local residents, as a local landmark had been passed into the hands of “outsiders.”Footnote 70 As local landmarks eye expansion into new markets, they risk losing the loyalty of their oldest consumers. From the perspective of enterprise growth, the sword of consumer nostalgia clearly cuts both ways.

Concluding thoughts

China's nostalgia for old brands is a book with many authors. It springs from discernible influences: a desire in the early reform era to reconnect with the pre-Maoist past, government campaigns to protect old brands, and the maturation of China's advertising industry. The constant transfer of initiative – between cultural and commercial departments, and between government and business – shows how different groups can take the creative lead in producing meaning, in conjunction with external influences such as the influx of MNEs, or generational change in consumer preferences. In the same way, China's food nostalgia may be influenced by both government and business, but it is not owned by either one. Consumers, both of products and ideas, are active and enthusiastic participants in the creation of meaning. A daily necessity and site of deep emotional connection, food is an especially fertile site to view this constant merging of meanings and images. The precise content of food nostalgia, what is being remembered, commemorated, or shared, is highly personal and highly fluid. Like any symbolic text, food nostalgia travels between different groups creating new meanings that reflect, evolve, and reinforce each other.Footnote 71

What then should we make of the apparent shift in emphasis from authenticity to creative, and thus created nostalgia? We could see, as Jin Feng does, a generational evolution of middle-class values, a rejection of the artificial scarcity behind the search for authenticity, as represented in the actual premises of a historical restaurant, in favor of the ultimately replicable values of what that experience represents, a celebration of craftsmanship, and recreation of local tastes as a form of vicarious travel. Of course, different types can coexist: just as a single maker might sell premium and mid-range lines of the same product, the same historical experience can be strictly authentic or a brand-certified facsimile. In terms of actual sales, mass-marketization disproportionately expands the latter, yet the two experiences can still reinforce each other – as when people see vacation pictures of a famous restaurant, and then rush to buy a mass-produced version of the same meal to eat at home. What makes the two parts of this experience nostalgic will indeed be as varied as nostalgia itself, but in the rush to create nostalgia for an imagined history, producers should not forget that the strongest associations might consist of something more personal and more prosaic, a sense of comfort in childhood tastes or familiar packaging, and the sense of loss as local favorites disappear or move away.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the support of the “Beijing ‘Gaojingjian’高精尖 scholarship fund – Cultural heritage and cultural transmission” Project 00400-110631111.