Millions of immigrants arrived in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, drastically altering the ethnic character of the American citizenry. This dramatic social change was met with mixed reactions from the native-born population that were vividly communicated in the popular press. Cartoonists for newspapers and magazines across the country developed a language of caricature to identify and distinguish among ethnic groups, and mocked new arrivals in imagery that ranged from mild to malicious. One might assume that the masses of Eastern European Jews flooding into the country (poor, Yiddish-speaking, shtetl-bred) would have been singled out for anti-Semitic attack, just as they were in Europe at the time.Footnote 1 However, Jews were not the primary victims of visual insults in America, nor were the Jewish caricatures wholly negative.Footnote 2 Further, the broader scope of popular imagery, which, in addition to cartoons, includes a plethora of illustrations and photographs, presents a generally positive attitude toward Jewish immigrants. This evidence, which aligns with American political rhetoric, literature, newspaper editorials, and financial opportunity, documents a shift toward greater public acceptance and validation of Jews in America.Footnote 3

This article will begin by reinterpreting several immigrant-themed cartoons to debunk the claim of virulent visual anti-Semitism argued for by art historian Matthew Baigell in his recent study, The Implacable Urge to Defame: Cartoon Jews in the American Press, 1877–1935. Footnote 4 An examination of ethnically prejudiced cartoons from the late nineteenth century, most of which targeted Irish and Chinese immigrants, as well as African Americans and Native Americans, disproves the argument that “Jews, among all immigrant groups, were shown in more and as many negative ways as possible.”Footnote 5 Next, it will present examples of popular illustrations of newly arriving Jewish immigrants, and argue for their affirmative tone. While Jews had been maligned in the illustrated press at times in the preceding decades, these new arrivals were treated with extraordinary sympathy during the prosperous years of the Gilded Age. Finally, it will look specifically at images of Jews from the year 1903, heavily focused on Russian Jewish refugees fleeing the violence of the Kishinev pogrom, as a high point of American support for Jewish immigration. In so doing, this article will propose a better alignment of the visual evidence with the scholarly understanding of the essentially providential experience of Jews in America during this period.Footnote 6

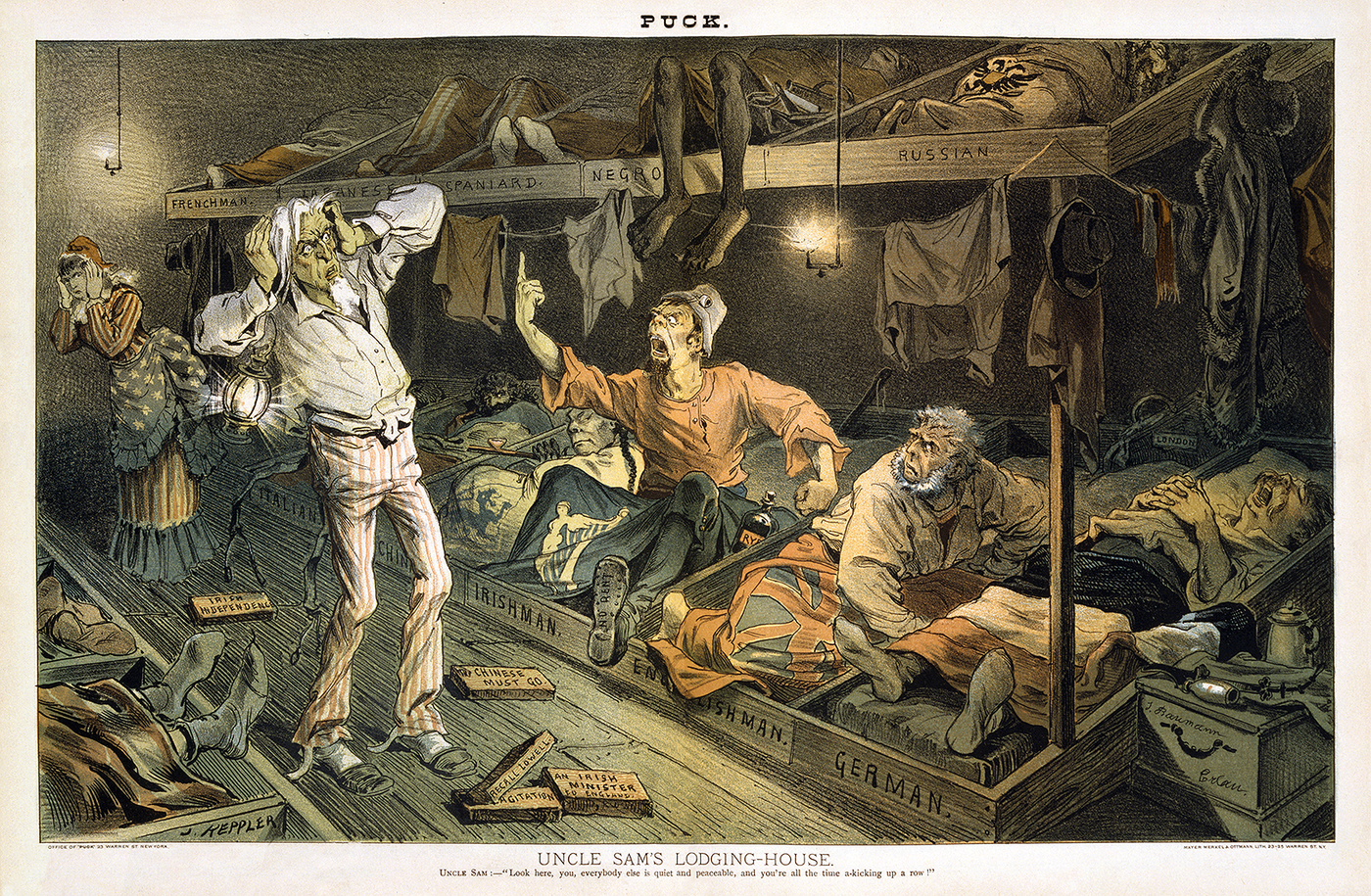

Let us begin by challenging the claim that Jews were shown more negatively than others in American cartoons of the late nineteenth century. One notices right away that cartoons that portray immigrants from a variety of countries typically include a Jew who fits with the others, even while someone else is singled out for ridicule. Joseph Keppler’s 1882 cartoon “Uncle Sam’s Lodging House”, for example, shows the dark and dingy sleeping quarters of a wide array of new immigrants (fig. 1). Each man, drawn with exaggerated ethnic features, uses for a blanket the flag from his country of origin. To leave no doubt, Keppler labeled each bunk with “German,” “Englishman,” “Irishman,” “Chinaman,” “Italian,” and so on. (This was early enough in the period of highest immigration that standard caricatures for national types had not yet been firmly established with the viewing public.) While the others try to sleep, the Irishman makes a fuss, causing Uncle Sam and Lady Liberty to cringe and cover their ears.Footnote 7

Figure 1: “Uncle Sam’s Lodging House,” Puck, June 7, 1882.

The Irish troublemaker is the only one in bed with his shoes on (primitive, poor), and he guards a bottle of rye (drunk), and throws bricks at Uncle Sam (violent) that say “The Chinese must go,” “Agitation,” etc. Almost unnoticeable on the top bunk, a Russian sleeps peacefully under the double-headed Imperial eagle. With beard, side locks, and a hooked nose, he is unmistakably a Jew.Footnote 8 Yet unlike the Negro, his feet are neatly tucked under the blanket; unlike the German, his mouth is not agape with snoring; unlike the Chinaman, he smokes no opium. This is not the only cartoon from the period that singles out the Irish as the worst of the immigrants, or “the one element that won’t mix,” according to another Puck cartoon’s caption from 1889. Many more hateful cartoons targeted the Irish and their allegedly primitive nature, a disparaging visual trope articulated most vividly by Thomas Nast in Harper’s Weekly in the 1870s and ‘80s. Cover illustrations such as that on the December 9, 1876, edition (“THE IGNORANT VOTE—HONORS ARE EASY”) normalized anti-Irish prejudice by presenting the Irishman as no better than the disdained Southern Black, and in some ways worse. The caricatured Irishman disrupts society with his violence and drunken rage in a way that the smiling Black simpleton does not.Footnote 9

Other cartoons suggest that in fact the Chinese were the one people among the many who needed to be banished. In a schoolhouse scene in an 1893 cartoon from Judge magazine captioned, “Be just—even to John Chinaman,” a judge admonishes the teacher, “Miss Columbia,” for trying to expel her Chinese student. Yet the full message, printed in the caption below, is far from accepting. “You allowed that boy to come into your school,” it reads, “it would be inhuman to throw him out now—it will be sufficient in the future to keep his brothers out.” The other pupils, who grin in amused solidarity, are a Native American, a Turk, an Indian Sikh, an African American, an Irishman, and a Jew. Here the Chinese man is the butt of the joke, as well as the victim of real discrimination in the form of racist immigration laws. The Chinese Exclusion Act, in effect since 1882, prohibited immigration of Chinese laborers, a penalty not suffered by the Jews, or the Irish for that matter, until the more broadly restrictive legislation of the 1920s. This is just one of many cartoons showing the Chinese as barred, chased, or literally kicked out of the country, imagery never employed against Jews. Cartoons like these are problematic for those looking for evidence of anti-Semitism as the most virulent of prejudices from this time.Footnote 10

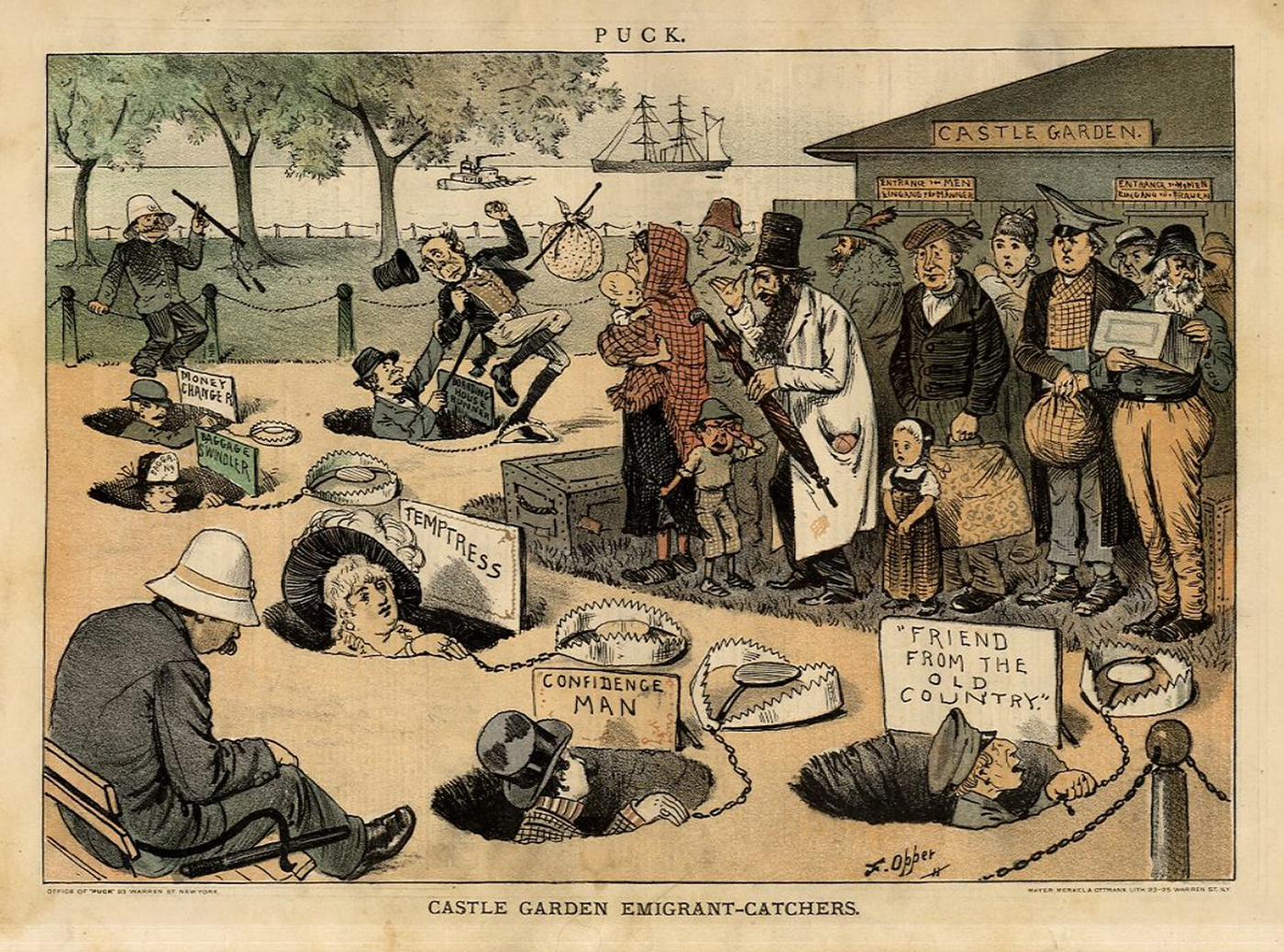

While caricatures were the norm in cartoons about ethnicity, the usual damning features with which European cartoon Jews were saddled, such as bags of gold, Masonic symbols, bloody hands, or grasping fingers, are mostly absent in American popular representations. The caricature, in this and other examples, parodies appearance but not the character or behavior of the Jew. An example of this uniquely American defanged caricature appeared in the June 1882 issue of Puck, titled “Castle Garden Emigrant-Catchers” (fig. 2). (Immigrants were processed at Castle Garden from 1855 until 1890, when Ellis Island became the point of entry.) In a scene of newly arrived immigrants, the Jew draws the eye with his classically caricatured beard, nose, hat, and stooped posture. Standing near him are other ethnic types, from the easily identifiable Irish to the left, to a few other European sorts on the right, yet he stands out with his white coat in the otherwise muted palette.

Figure 2: “Castle Garden Emigrant-Catchers,” Puck, June 14, 1882.

The Jew’s behavior, however, takes the poison out of the stereotype as he waits patiently in line and attempts to comfort the crying child whose father just got snagged in a trap. The cartoon elicits sympathy for these naïve “emigrants” who are visually identified as foreigners for the joke to make sense. Thus, they all sport different hats and have exaggerated features, but as a group they demand the viewer’s understanding and protection. A few years later in France, Edouard Drumont’s anti-Semitic paper La Libre Parole featured a similarly caricatured profile of a Jew on its cover (same nose, lips, beard, and bushy eyebrows.)Footnote 11 The French Jew’s head, though, is full of damning thoughts, including theft, cowardice, greed, and drunkenness. The Castle Garden cartoon, in contrast, looks anti-Semitic at first glance but in fact makes no accusation against Jews.Footnote 12

It is critical here to understand the function of caricature as a mode of mass communication when evaluating its meaning in context. Since they communicate through shorthand visual cues, caricatures will inevitably appear racist when their subject is ethnicity, especially to the modern eye. A caricature “typically exaggerates so as to differentiate the subject from his fellow.”Footnote 13 Thus if labels are not provided, the viewer will only understand the point if the “Chinaman” has a queue (long braid) and slits for eyes, the Irishman appears skinny and clad in shamrocks and plaid clothing, the Jew presents as hairy and hook-nosed.Footnote 14 Caricatures, described by Judith Wechsler as “the graphic exaggeration of facial and bodily features for comic effect,” are defined by absurdly generalized amplifications and thus are equally essentializing of all. In a heterogeneous population, the caricature provided a necessary common visual language for ethnic identity that allowed for the public to grapple with the dramatic transformation of the population through immigration.Footnote 15

We are particularly offended today by ethnic caricature, but it is not clear if audiences in the late nineteenth century saw things the same way. Oscar Handlin argued this point about Jewish caricature in his article, “American Views of the Jew at the Opening of the Twentieth Century,” in which he suggests, “Jews themselves accepted the caricature,” and reproduced such images in their own publications such as Der Yiddischer Puck. “In neither case,” Handlin concludes, “did the picture reflect a depreciatory attitude.”Footnote 16 There are exceptions to this claim, for example the March 13, 1881, Puck centerfold, which was met with complaints from The Jewish Immigrant that it made light of Russian violence driving Jews to American shores. Yet Joseph Keppler could reasonably defend “The Modern Moses” cartoon, co-signed by the half-Jewish Frederick Burr Opper, even though today his caricatured faces of Jews crossing the Atlantic would not be tolerated.Footnote 17

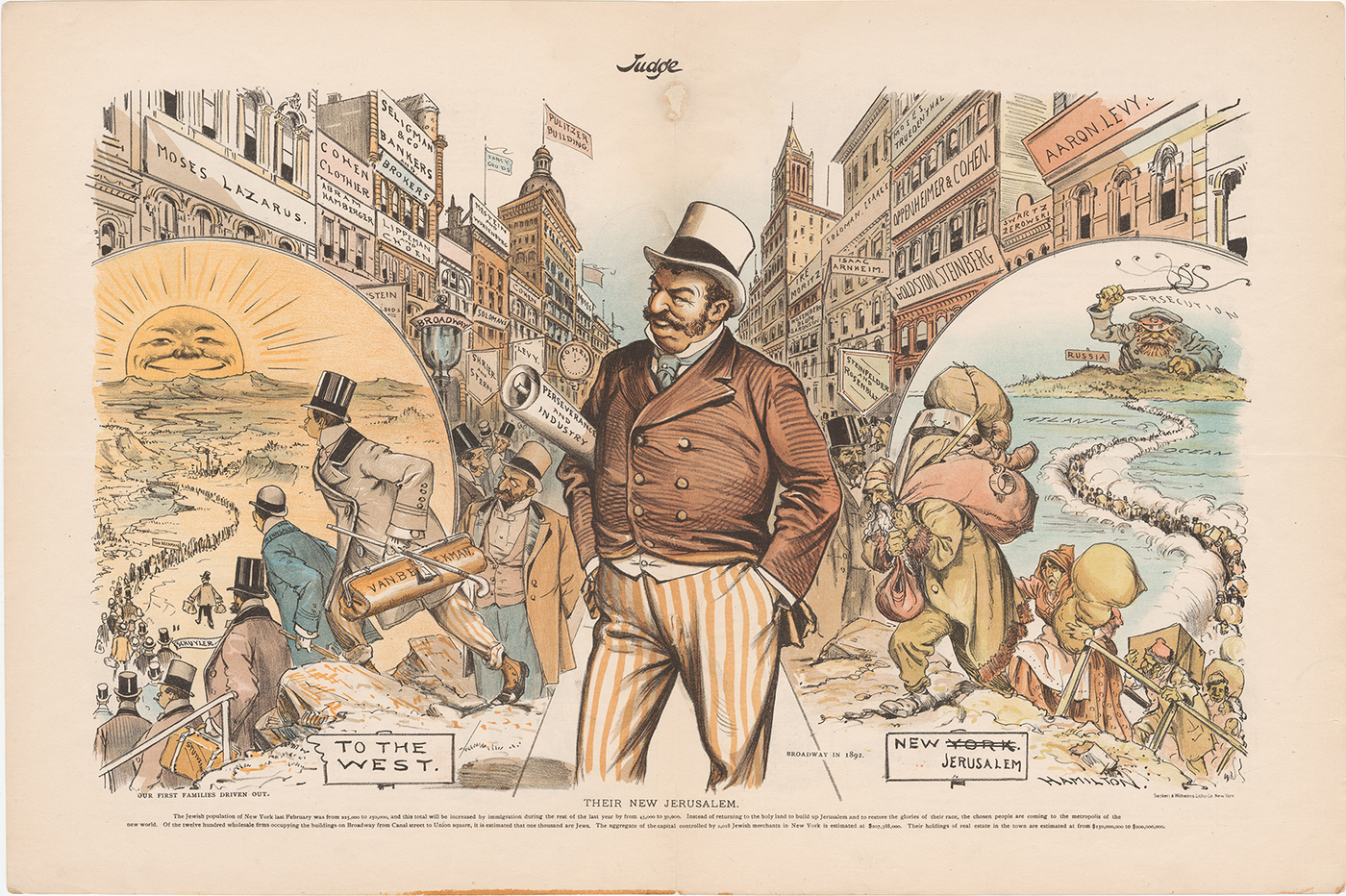

Grant E. Hamilton’s well-known cartoon titled “Their New Jerusalem”Footnote 18 is a test case for the assertion that imagery today perceived as offensive was not generally understood as such in this historical period (fig. 3). This cartoon has been referred to as anti-Semitic by Wikimedia, whose description of the image reads “An anti-semitic cartoon from Judge magazine;” Amazon, who sells a print of the cartoon where it is labeled under the tag “Judaism Antisemitism;” and Cornell University Library Digital Collections website, which refers to it as “blatantly anti-Semitic.” Further, the online journal Salon used the cartoon to illustrate an article about American anti-Semitism in the nineteenth century, as though the cartoon’s meaning is unambiguous.Footnote 19 However, a close reading does not support this overly simplistic categorization. Nor is there any evidence that viewers at the time objected to it. Instead, Hamilton’s cartoon contains contradictory meanings, some critical and some admiring.

Figure 3: “Their New Jerusalem,” Judge, January. 23, 1892.

The negative message is perhaps clearer. On the right of the scene, titled “Their New Jerusalem,” an endless parade of shabby, foreign-looking Jews trudges from Europe through the Atlantic toward America. They carry with them their meager belongings in worn-out sacks and boxes, and stream into New York City, or “New Jerusalem,” as the city is renamed on a sign at the shore. They are not the first of their people to arrive, as is clear by the Jewish names marking every building on Broadway. New York has already been taken over by this Jewish invasion, the imagery implies, and things are about to get even worse. Unlike their triumphant predecessors, gathered in the center background with their trimmed beards and expensive suits, the new arrivals appear undesirable and pitifully Old World.Footnote 20 Meanwhile, blue-blooded Americans, with names like Von Beekman, Schuyler, and Stuyvesant, cannot escape fast enough as they exit stage left toward the sunny West. “Our first families driven out,” warns the text. The contrast between these “first families,” with their stylish overcoats, shiny top hats, and spats, and the threadbare Russian Jews could not be starker, and the deliberate use of pronouns (our first families, their new Jerusalem) tells the viewer where her sympathies should lie.

This narrative plays directly to American fears at the time about an overwhelming torrent of undesirable riffraff arriving from Europe, including Eastern European Jews. While Jews had been immigrating to America all throughout the nineteenth century, the big upsurge in numbers resulted from growing anti-Semitic violence in Russia and Central Europe, as well as a huge population boom in the Pale that caused overcrowding and economic desperation. In the 1870s there were 250,000 Jews living in the United States, by 1890 about 500,000, by 1905 about 1 million.Footnote 21 With millions of immigrants, usually in desperate straits, arriving in a relatively short period of time, it is natural that Americans would worry about the possibly negative effects on their country.Footnote 22 Judge’s “Their New Jerusalem” cartoon reassures the viewer that while cities might be teeming with foreigners, at least the countryside would remain untainted by undesirable elements.Footnote 23

And yet, there are several undeniably affirmative aspects to the representation of Jews in cartoonist Hamilton’s depiction. The immigrants cross the Atlantic as the waters miraculously part, just as the Jews escaped Egypt when God parted the sea in the Exodus story. America thus becomes the Promised Land divinely given.Footnote 24 The most fundamental of all Jewish stories (Exodus) resonates powerfully with the American story of the Pilgrims escaping religious constraints in England to seek freedom in this new land. As Bruce Feiler, author of America’s Prophet: How the Story of Moses Shaped America, explains, the Pilgrims saw themselves as the new Israelites. “When they embarked on the Mayflower in 1620,” Feiler writes, “they described themselves as the chosen people fleeing their pharaoh, King James. On the Atlantic, their leader, William Bradford, proclaimed their journey to be as vital as ‘Moses and the Israelites when they went out of Egypt.’ And when they arrived in Cape Cod, they thanked God for letting them pass through their fiery Red Sea.”Footnote 25 Could Americans think poorly of the new Jewish immigrants whose journey echoed the mythic arrival of the “first” Americans, who were themselves following in the footsteps of the biblical Israelites, directed by God?

The larger-than-life figure in the center may be thought of as a contemporary Moses figure (note the sign that reads “Moses Lazarus” on the left). Although clearly Jewish, he is appealing in his stylish clothing, like the New York Jews behind him, with trousers as stylish as those of Van Beekman. He looks vital and strong, and his face expresses intelligence, warmth, and humor. The scroll under his arm reads “PERSEVERANCE AND INDUSTRY,” two highly valued qualities that were at the heart of the American ethos during the industrial period. This motto seems to be echoed in its grammatical structure by the signs on many of the buildings: “Lippeman and Choen,” “Shrier and Stern,” “Steinfelder and Rosenblat,” etc. These names include Moses Lazarus, a successful industrialist (sugar refining) whose daughter, Emma Lazarus, had written the poem “The New Colossus,” read a few years prior at a fundraising event to support the building of the Statue of Liberty and later inscribed on a plaque installed at the site. Also, a flag in the center back of the scene that flies from a soaring, domed skyscraper draws attention to the Pulitzer Building, a reference to Joseph Pulitzer and his influential newspaper the New York World. Broadway in this view looks nothing like a Jewish ghetto but instead shines forth as a splendid American metropolis with thriving businesses and beautiful architecture.

Not all cartoons encourage such a nuanced interpretation, however, for blatantly anti-Semitic imagery did appear at times in the pages of American magazines and newspapers, even though far less often than in the European press. Arguably the nastiest, a full-page feature in the December 9, 1897, issue of Life Magazine features a grotesquely caricatured Jew in the form of a drooling octopus “in his great character The Theatrical Trust” (fig. 4). With his huge nose, grasping tentacles, and gleaming diamond chest plate, this figure resembles the worst of European-style visual anti-Semitism, the variety promulgated in France by Drumont’s La Libre Parole in the 1890s and beyond. While deeply offensive, it is certainly not the case that “the reptilian octopus image was reserved for Jewish theatrical and financial interests.”Footnote 26

Figure 4: “The Theatrical Trust,” Life Magazine, December 9, 1897.

“How come,” Baigell laments, “even a handsome, WASP-looking octopus was never used to illustrate the political and economic reach of Big Oil, Big Steel, and other trusts …?”Footnote 27 This is simply untrue, however. Examples of handsome octopuses can easily be found, for example, in the October 23, 1879, Daily Graphic, which featured a killer octopus graced with the idealized visage of William Henry Vanderbilt. Another that ran in the Wasp as a full-page, color cartoon on August 19, 1882, presents a gleeful octopus labeled “Railroad Monopoly” (the WASP-y faces of Southern Pacific Railway magnates Mark Hopkins and Leland Stanford for eyes) wreaking havoc in San Francisco Bay. These two cartoons, among many others, demonstrate that the octopus at this time was not an anti-Semitic character per se but instead a visual symbol of the reach of big business and monopolies. Indeed, the octopus has proved such a useful symbol of dangerous control that it has been used since to represent everything from industrial monopolies to political machines to Communist regimes to big tech, in addition to Jews from the Gilded Age through the Nazi period and beyond.

Anti-Semitic cartoons from the late nineteenth century are not hard to find in American magazines and newspapers, and express an undercurrent of prejudice that is undeniable.Footnote 28 It is not the case, however, that they disprove or weaken the thesis of this article, because these cartoons are, with very few exceptions, small, badly drawn, and hidden away deep into the back pages of the publications in which they appear. The exceptions include the Theatrical Trust cartoon, which was a large centerfold image, and the 1882 “The New Jerusalem, Formerly New York,” a detailed, color scene of Broadway “occupied” by a Jewish army dressed in Revolutionary War era uniforms.Footnote 29 One further example, found in the December 8, 1880, German-language edition of Puck, addresses two well-reported episodes of Jews denied admission to hotels (by Judge Henry Hilton and Austin Corbin), both of which happened in the 1870s. Expertly drawn by Joseph Keppler, the centerfold lithograph, titled (in English translation) “The Newest Anti-Jewish Agitation,” offers up a caricatured Jewish peddler being kicked by Bismark, Hilton, and Corbin. As with the New Jerusalem cartoon, though, the meaning here is ambiguous, with the abusers represented as small in stature relative to the Jew, cruel, and, in Corbin’s case, blind. The peddler will prevail in the end, as the caption makes clear: “but I am used to it for the past 1800 years, and I do pretty well with all.”Footnote 30

More typically cited examples of visual anti-Semitism were, in fact, artistically primitive, visually inconsequential marginalia in the back pages of Puck and other magazines. These include two Puck cartoons from 1881: Frederick Opper’s frequently reproduced “The ‘New Trans-Atlantic Hebrew Line’” with its ugly caricatures and snide tone and another by an unknown artist that shows an oceanfront boardwalk crowded with ugly, rich Jews on vacation. Another egregious example, included in the Baigell book, is artist C.M.C.’s “If You Don’t Come Up Again, Goldstein,” from the December 21, 1899, Life that depicts two caricatured Jews fighting over a huge, glittering jewel all the while drowning at sea. While these examples reveal an undercurrent of casual anti-Semitism, they should not be viewed as equal in significance to magazine covers and full-color centerpiece spreads that had much greater visual presence and were seen by many more people. It is fundamentally misleading to isolate images from the page on which they originally appeared and present them all as of equal significance, just as it would be false to equate a front-page headline with a human-interest story in the back of a newspaper. This author is not aware of any instances of American magazine covers from the 1880s and 1890s, for example, that contain virulent anti-Semitic caricatures, again in contrast to the Irish, Chinese, and African Americans, who often were mercilessly targeted on the front of Puck and other magazines.

Attempts to prove virulent anti-Semitism utilizing visual evidence from the years addressed in this article (1880–1903) are not persuasive.Footnote 31 Discrimination against Jews was present throughout the culture (hotels, universities, law firms, etc.), yet the broad consensus is that Jews enjoyed more freedom and a better life in the United States at this time than they had virtually anywhere else or at any previous time. The affirmative interpretation of the imagery thus presented in this paper derives from a historically grounded, mostly positive view of Jewish life in America that prevailed during the Gilded Age into the early years of the twentieth century. It is the American ideal of tolerance that gives context to the next group of images, those illustrations of Jewish immigrants just arriving in America.

The remarkable humanism of these representations, beginning back in 1881, reveal the power of the ideology of America as not only “tolerant” (a rather tepid term after all) but as a “haven for the oppressed.” “Columbia Welcomes the Victims of German Persecution to the ‘Asylum of the Oppressed,’” reads the instructive caption of an illustration in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (fig. 5).Footnote 32 On the left stands Columbia, personification of liberty in her Phrygian cap, with arms open to receive a long line of Jews fresh off the boat. The caption does not identify these newcomers as Jews; nevertheless it is abundantly clear that they are Jews due to their physiognomy as well as the suitcase marked “M. Levy.” Although somewhat caricatured, the Jews appear not only harmless but also sympathetic. The man at the front of the line smiles and reaches his hand toward Columbia in a gesture of trust. His older son looks on in awe while the younger son shoulders heavy bags, both evidence of future good citizenship. The men and women down the line look relatively clean and well dressed, and, though they carry heavy burdens, will not themselves become a burden to their adoptive home. A number of children strategically placed in the forefront draw on the viewer’s emotions. Babies, little girls in dresses, and dutiful young boys must be given a home, implies the artist.

Figure 5: “Columbia Welcomes the Victims of German Persecution to the ‘Asylum of the Oppressed,’” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, January 22, 1881.

At the time of this illustration’s publication, a large number of Jews began arriving from Russia in the wake of the pogroms that followed the assassination of Czar Alexander II. Thereafter, Russian Jews became the subject of many an artist’s pen. On August 5, 1882, the same publication featured a full-page illustration captioned: “NEW YORK CITY—RUSSIAN JEWS AT CASTLE GARDEN—A SCENE IN THE EARLY MORNING” (fig. 6). Whereas the German Jews were framed in an allegorical context, the Russians appear in a grittily realistic scene, and have been “quarantined” by the artist away from the mainland. Men, women, and children have all spent the night exposed to the elements in an area not unlike an animal pen. A makeshift structure in the background provides the only shelter, and most have slept, or are still sleeping, directly on the ground. They are stuck in limbo without the hopeful glimpse of the city in the background, as in the earlier image. There is no warm maternal figure to embrace them, and the artist refrains from visually clarifying the ultimate fate of these beleaguered people.

Figure 6: “Russian Jews at Castle Garden,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, August 5, 1882.

While a few of the men are marked by foreign-looking Semitic noses and beards, the people in the immediate foreground, among whom the artist places the viewer, are the least alien and most sympathetically drawn. In the front right corner, two young men are dressed in shirtsleeves and vests and sport modern haircuts and trimmed beards. They would blend right in with New Yorkers, the kind possibly reading that very newspaper. Most affecting, though, are the mother and infant in the lower left who are positioned facing the viewer (the only ones so posed). The baby clings to its mother’s arm as she lowers her blouse to nurse. This is not only a profoundly human image; it is also an undeniably Christian one, a Caravaggio-like Madonna of the ghetto. The clear parallel to Mary and baby Jesus in a rustic manger, an image geared to play on the emotions of non-Jewish viewers, adds a charge of symbolic power to an otherwise drab scene. Further, the responsibility of the society to care for these people is given as a moral imperative.

Though the poor Russian Jews caused some discomfort for their German predecessors who were successfully assimilated, they had their champions, not only from the American Jewish community, and not only based on the American sacred role as “haven for the oppressed,” but on their own unique merits. Ida Van Etten, the first secretary of the Working Women’s Society of New York, advocated for this demographic in an article published in Forum, April 1893, called “Russian Jews as Desirable Immigrants.” “It would clear away many misleading theories to remember that it is not the condition in which the immigrant comes that determines his usefulness, but the power that he shows to rise above his condition,” she writes somewhat defensively against the nativist position. “And if the ability to rise superior to adverse conditions be a proof of strength of character, we must concede that the Russian Jew possesses this quality in no mean degree.” She reminds her readers that Jews are a “temperate people,” intelligent and well-informed, and hardworking. She concludes, “Politically the Jews possess many characteristics of the best citizens.”Footnote 33

Abraham Cahan, founder and editor in chief of the major New York Yiddish paper the Jewish Daily Forward included the above van Etten quotations in a major piece (twenty-five pages) published in the July 1898 Atlantic Monthly called “The Russian Jew in America.” Addressing a general audience, he explained and defended with passion the surge of Russian Jewish immigration to the United States. Further, Cahan offered the reader endorsements by non-Jews of these new arrivals, under the principle, “Let another man praise thee, and not thine own mouth; a stranger, and not thine own lips.” Jews would be expected to speak approvingly of fellow Jews, but non-Jewish approbation carries more weight, as it cannot be viewed as self-serving.Footnote 34

One such admiring “stranger” was Jacob Riis who, in 1896, leveraged his reputation as a champion of the poor to support the Jews in a piece called “The Jews of New York” for Review of Reviews. While he acknowledged the attitude of some who saw in the Jewish immigrant community a “suffering multitude in its teeming tenements, fettered in ignorance and bitter poverty,” he countered this negative view by arguing “they do not rot in their slum but rising pull it up after them.” He continued to praise all manner of characteristics and habits of the Jews living in New York tenements, and concluded with the assertion, “I am very sure that our city has to-day no better and more loyal citizen than the Jew—be he poor or rich—and none she has less need to be ashamed of.”Footnote 35 While this editorial is not expressly about immigration, it would have influenced readers’ attitudes toward those who continued to flood into the city, so many of whom were Jews.

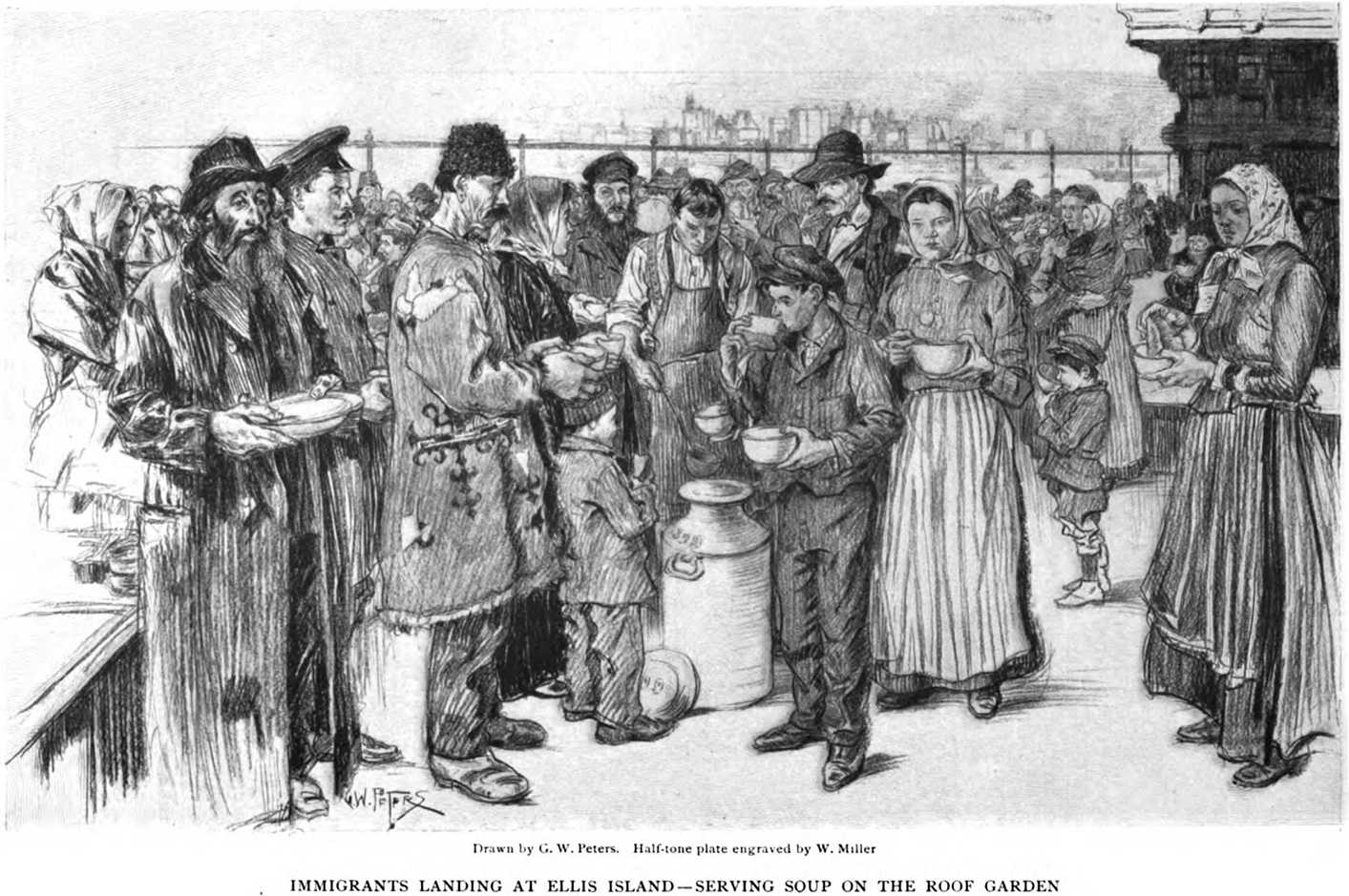

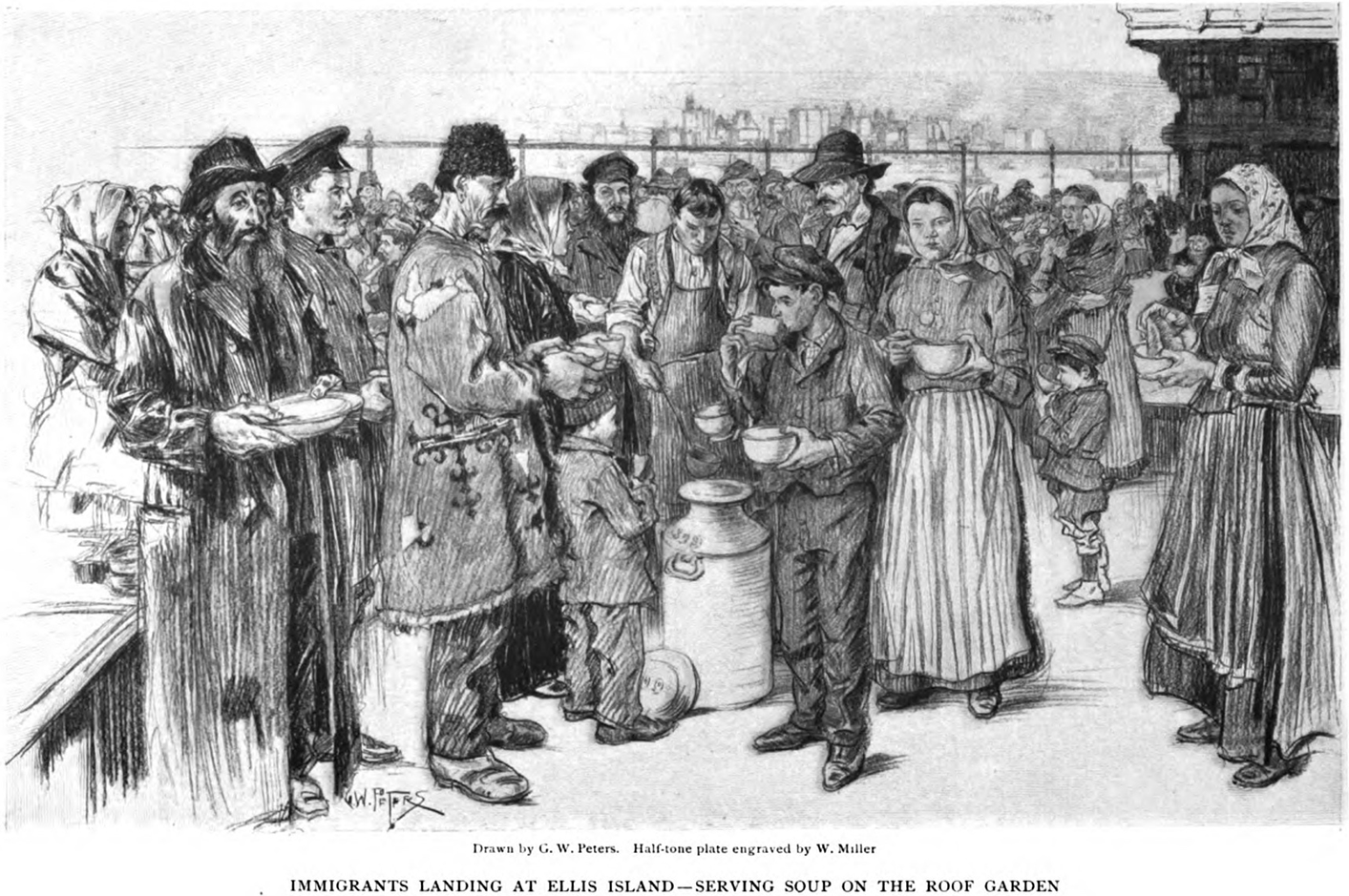

Riis expressed an appreciative view of newly arrived immigrants in general in Century Magazine.Footnote 36 In his article titled “In the Gateway of Nations,” illustrated with highly detailed engravings based on drawings by G. W. Peters, Riis reminisces about his own disorienting arrival from Europe decades earlier, and looks on with understanding and warmth at the latest arrivals. Of the four engravings that depict groups of immigrants in various moments of being “processed” at Ellis Island, two feature a Jew prominently in the foreground. The more artistically developed of the two, titled “Immigrants Landing at Ellis Island—Serving Soup on the Roof Garden,” shows a large, diverse crowd gratefully accepting hot food while they stand around in a state of visible exhaustion (fig. 7).

Figure 7: “Immigrants Landing at Ellis Island – Serving Soup on the Roof Garden,” Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, March 1903.

Unlike the illustration of Russian Jews at Castle Garden, though, this scene takes place within view of the New York skyline, a hopeful sign of their future lives as Americans. In the front left, closest to the viewer and immediately adjacent to the artist’s signature, stands a weary, somewhat shabby middle-age Jewish man. The artist transforms this anonymous refugee into a deeply sympathetic portrait of suffering and stamina through the sensitive treatment of his expression (at once tired, grateful, pained, and hopeful). The unity of these disparate people as they break bread together around a cistern of soup foretells the notion of the melting pot (a term coined a few years later by Israel Zangwill)—they will all become Americans.

Several contemporaneous publications, written by Jews as well as non-Jews, argued for the benefits of Jews in society. In 1895, Rabbi George Alexander Kohut’s Sketches of Jewish Bravery, Loyalty and Patriotism: In the South American Colonies and the West Indies was published in Philadelphia.Footnote 37 The book praised the dedication of Jews to their country and chronicles their history of brave military service. The year 1899 saw the publication of Justice to the Jew, written by the clergyman Madison Clinton Peters. Subtitled “The Story of What he has Done for the World,” the hefty tome lauds Jews in every possible way. Mostly the same material appeared in a 1903 volume by the same author titled The Jew as a Patriot that ends with a triumphant chapter called “The World’s Indebtedness to the Jew.”Footnote 38 The text praises Jewish knowledge, humor, financial ability, “longevity,” “Law-abiding spirit,” and charitable work.

Likewise, Hutchins Hapgood’s 1902 book The Spirit of the Ghetto, generously illustrated by artist Jacob Epstein, offered readers a profoundly sympathetic portrait of the recently arrived immigrants of the Lower East Side.Footnote 39 By 1903, American readers were primed to think positively of Jews, just in time for a major episode in the history of Jewish immigration to America. The attitude of acceptance toward Jews during this period culminated in the huge swell of sympathy and activism in response to the Kishinev pogrom of 1903. Those who loudly protested Russian persecution of Jews did so in full knowledge that the result would be fresh waves of desperate Eastern Jews seeking refuge and ultimately citizenship in the United States.

As immigrants continued to pour into the country in the early years of the twentieth century, the plight of Russian Jews in particular rose to a new level of public awareness in April of that year when news of a pogrom in Kishinev (sometimes written as Kishineff) began to trickle out. Pogroms (violent riots aimed at the massacre of a particular ethnic group) had terrorized the Jewish communities of Russia for at least two decades. However, the three-day spasm of violence in this Bessarabian city (Bessarabia refers to an area roughly equivalent to modern day Moldova), which left forty-nine dead, untold raped, and vast destruction of property, gripped the world’s attention in a way not seen before, as chronicled in a recent study by Steven Zipperstein.Footnote 40 Accusations that the czar himself had directed the violence outraged people around the globe, perhaps nowhere more so than in the United States, which reacted with shock to the alleged state-sponsored religious persecution. Although there was a “popular belief among the Russian peasants that the czar decreed the slaughtering of the Jews,” there is no evidence to support this charge.Footnote 41 Instead the violence was instigated by a local newspaper published by Pavel Krushevan, the man responsible for the first publication of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion in the fall of that year, in retaliation for the unrelated death of two local children.

Americans from the president on down reacted with tremendous support for the victims that took the form of speeches, rallies, fund drives, and so on. President Roosevelt spoke in defense of the Jews in the wake of the Kishinev pogrom, sending a letter to the czar that began, “I need not dwell upon a fact so patent as the widespread indignation with which the Americans heard of the dreadful outrages up on the Jews in Kishineff.”Footnote 42 Popular support poured from the pages of the press in an extraordinary surge of sympathetic imagery that both dramatized the horror of the pogrom and represented with kindness and humanism the refugees washing onto American shores.Footnote 43 The more the public bore witness to the violence perpetrated on defenseless Russian Jews, the greater the support for the victims became. Even Judge magazine, known for its nativist editorial slant, demanded of the czar: “Stop your cruel oppression of the Jews,” words spoken by President Roosevelt in a well-known cartoon from 1904 (fig. 8). The czar’s persecution should be criticized, Judge readers would have understood, because it sticks the United States with more unwanted refugees, a message somewhat lacking in real compassion for the victims. Yet even here, in the same magazine that published a cartoon the year before depicting European immigrants as rats, the old Jew with his enormous burden inspires pity.

Figure 8: “Stop your Cruel Oppression of the Jews,” Judge, September 30, 1905.

Other cartoons highlighted the brutality of the Russian perpetrator and contrasted that with the helplessness of the Jewish victims. The St. Paul Pioneer Press, the Evening Journal, and other papers published cartoons that featured a terrifyingly brutal Russian looming over his victims holding a sword dripping with blood. The San Francisco Call ran a front-page story on May 16, 1903, with the headline “Russia Permits Outrages and Terrified Jews Flee in the Thousands from Homes.” Framed photographs of the czar’s henchmen overlay a shocking illustration of a Russian soldier mercilessly clubbing a man, woman, and child. A week later the Call ran another front-page piece illustrated by a collage of photographs of Kishinev and two prominent rabbis intermixed with a drawing of a rabbi being murdered by three savage men. World’s News printed an illustration showing rioters destroying Jewish property while several victimized women react with dismay in the foreground.

In addition to these cartoons and illustrations about the pogrom itself, many newspapers published photographs of the pogrom’s victims as well as drawings based on photographic evidence. The New York American and Journal featured a full-page photograph accompanying an article titled “Photographic Evidence of Russian Mob Outrages on the Jews” on June 14, 1903. One man stands in a Jewish cemetery and, informs the caption, “The 44 mounds are the newly made graves of the massacred.”Footnote 44 The photograph provides undeniable proof of the dreadfully violent consequences of unleashed prejudice. Other papers illustrated the story with drawings based on photographs of bandaged victims in a hospital (front page, The Spokane Press, June 27, 1903), and corpses laid out on the floor (full-page article, Deseret Evening News, May 30, 1903). Although photographs first appeared in American newspapers in the 1880s, “it was not until 1919, with the launching of New York’s Illustrated Daily News, that American newspapers began to feature photographs routinely.”Footnote 45 Thus photographs presented as evidence of historical events would have had great persuasive power over contemporary readers.Footnote 46

For an unfortunately commonplace event that happened in a remote location, the Kishinev pogrom received an astonishing amount of worldwide attention due to outrage on behalf of the Jewish victims. Irish writer Michael Davitt, sent to Kishinev by William Randolph Hearst (publisher of the New York Journal), was one of several journalists who carried out extensive investigative work immediately following the pogrom. In addition to providing historical background and current facts about Jewish life in Bessarabia, Davitt’s book-length report, Within the Pale: The True Story of Anti-semitic Persecutions in Russia (1903), overflowing with vivid descriptions of horrors committed, “had a marked effect on molding public opinion.”Footnote 47 The next year saw the publication of Cyrus Adler’s Voice of America on Kishineff. After a brief introduction that recounted this atrocity, the book presented almost five hundred pages of editorial articles from newspapers around the country as well as the collected records of meetings, sermons, resolutions, relief measures, and petitions on behalf of the victims. Many of those protesting the actions of Russia and campaigning on behalf of Jewish victims were themselves Jews, but many others were not.

Several of these articles proposed ways to bring the victims to the United States and reasons why this would be a good idea. Although the most emphatic proponents tended to be Jews (rabbis, community leaders), non-Jews offered similar resolutions to offer a safe haven in America for Russian victims. The Reverend William C. Stiles of New York City, for one, suggested that Russia’s loss was America’s gain. “Without asking for help from the American people,” he wrote, “the Russian Jew was productive and patriotic because he was grateful to have escaped from Russian tyranny to the land of the free.”Footnote 48 Commander Frederick Booth-Tucker of the Salvation Army proposed in a letter to the press “to bring over to the United States 1,000 selected families” to be settled in the South, under the belief that spreading the Jews around was better than allowing them to crowd certain Northern cities.Footnote 49 H. B. Blackwell of Boston, at a meeting in Faneuil Hall on May 17, 1903, said, “If we cannot directly interfere to prevent these atrocities, let us help these fugitives to make their homes in this new world.”Footnote 50 Colorado Senator Henry M. Teller (Republican), in Denver, May 24, remarked that he was “glad that the ports of the world are open to the oppressed people, and that they can come to this country and have absolute safety and absolute justice.”Footnote 51

President Roosevelt set a tone from the top that was generally welcoming of immigrants, remarking in the late 1890s, “there are classes and even nationalities of them which stand at least on an equality with the citizens of native birth.”Footnote 52 A successful system, though, depended on the sloughing off of ethnic heritage to allow the immigrant to blend seamlessly and quickly into American society. Years later, he insisted that if “the immigrant who comes here in good faith becomes an American and assimilates himself to us, he shall be treated on an exact equality with everyone else, for it is an outrage to discriminate against any such man because of creed, or birthplace, or origin.”Footnote 53 When evaluating Roosevelt’s stance on immigration (America received fifteen million immigrants between 1900–1915), one must weigh his indignant rejection of discrimination with the restrictionist laws passed by his administration in 1903, 1906, and 1907. Indeed, by 1919 (in a letter written three days before his death) his thoughts veered in a less progressive direction: “We have room for but one flag, the American flag…. We have room for but one language here and that is the English language, for we intend to see that the crucible turns our people out as Americans…and not as dwellers in a polyglot boarding house …”Footnote 54 Joseph Keppler showed more acceptance of such a boarding house in the 1882 Puck cartoon discussed above in which, save for the Irishman, the boarders are seen as compliant wards of the nation. Keppler’s generally upbeat view was easier to espouse then as the huge waves of immigration were just getting started. By 1919, after the war had halted European immigration, the mood of the nation had turned dramatically against immigration and the level of anti-Semitism was on the rise.Footnote 55 The American response to the Kishinev pogrom was a final chapter of a history of benevolent tolerance toward Jews compared to what came later.

Despite his conflicted views of the immigrant, Roosevelt stars as an unambiguously heroic savior to Russian immigrants in a beautifully drawn cartoon in Puck from July 1, 1903.Footnote 56 Here Roosevelt, as captain of a small boat, throws a line of Tolerance to a ship marked “Immigrants” making its way out of a dark storm of Prejudice toward the rainbow light of Liberty. The lower right of the page features a statement by Roosevelt about immigrants in which he attempts to guide the nation in this direction: “I feel that we should be peculiarly watchful over them, because of our own history, because we or our fathers came here under like conditions. Now that we have established ourselves, let us see to it that we stretch out the hand of help, the hand of brotherhood, toward the new-comers, and help them as speedily as possible to shape themselves and to get into such relations that it will be easy for them to walk well in the new life.”Footnote 57 These remarks, made just a few weeks earlier at the consecration of a church in Washington, DC, in conjunction with Keppler’s cartoon and its emphasis on prejudice, would have left little doubt in the viewer’s mind as to who was on that ship.

Newspapers with no self-serving (i.e., Jewish) agenda published feature articles replete with visuals about the benefits of Russian Jews once in America. These articles, appearing in the weeks immediately following the pogrom, promoted the acceptance of the refugees into various cities by demonstrating in text and image how well they integrate into American society. The Detroit Free Press ran a full-page article on May 31, 1903, about the substantial accomplishments of the Russian Jewish residents of that city. The article explains that Russian Jews are “intelligent, sensible, hard-working people, sober and religious, of good moral character and determined to get ahead in the world. They are men with characteristics that make any nation strong.”Footnote 58 The ten such men offered as examples, shown in oval-shaped photographic portraits, look indistinguishable from any other white-collar Americans with their smart suits and clean-shaven faces. In addition, their synagogue, shown in a photograph at the top of the page, looks like a beautiful neo-Classical temple, a desirable feature in the urban landscape.

The St. Louis Republic used a more direct approach to the subject in its front-page article “St. Louis Ghetto a Refuge for the Persecuted Jews of Russia,” June 7, 1903. While the text is all about the Kishinev pogrom, the upper half of the page is filled with photographs and illustrations of Jews recently arrived from Russia. A caption at the top of the page informs the reader “scores of money orders have been sent to suffers [sic] from this colony and many of those who escaped are en route to St. Louis.” At the center, a drawing of a beautiful young woman with dark curly hair dressed in vaguely exotic clothing captures the viewer’s attention. Cheerful and full of spunk, she looks like just the kind of energetic new American that any city would be happy to welcome. This artistic rendering allows for a degree of romantic license as compared to the realism of the photographs around her on the page, which are dark and rather badly reproduced.

Not everyone who righteously condemned the perpetrators, it should be noted, was in favor of the Jewish victims showing up in America as refugees, an ambivalence already noted in relation to the Judge cartoon of Roosevelt scolding the czar. Colonel John B. Weber, chairman of a special commission to investigate conditions in Europe in 1891, wrote quite movingly about the atrocities committed against the Jews in Kishinev. However, he proceeded to caution his reader, “We cannot look with unconcern upon the arrival of the thousands of hunted, terror-stricken human beings who come to us crushed in spirit and impoverished in substance, to enter into competition with our respected and self-respecting labor, and if any government by its acts forces such people upon us, in so unhappy and deplorable a condition, it is clearly within our international rights to object.”Footnote 59 In other words, please treat these “particles of humanity” more kindly so that they do not “become detached from their native soil.”

Hesitations notwithstanding, illustrations of this “stream of fleeing people” as they arrived in America were largely supportive and mostly lacked the reserve expressed in written editorials. On May 16, 1903, just as news of the pogrom began trickling out, the Philadelphia Inquirer ran a large, front-page allegorical drawing showing Columbia (America) comforting a woman and baby as they flee from the Russian devil (fig. 9). The devil here is clearly modeled on Satan in the ninth circle of Hell in Gustave Dore’s illustrated Inferno, a popular edition of the classic in nineteenth-century America.Footnote 60 He squats in the dark over a land labeled “Bessarabia,” and the words “RUSSIAN MISRULE” appear prominently in the lower left. Meanwhile a female allegory labeled “CIVILIZATION,” holding aloft a brilliant torch, leans over to receive the terrified mother and child who emerge from the darkness (another clear Madonna and Child reference). The figure of “Civilization” closely resembles that of Columbia as she appears in a Life cartoon that year (same drapery, star-spangled hair, and warm embrace of immigrants). The cartoon is clearly meant to affirm the God-given responsibility of the United States to welcome “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore,” in the famous words of poet Emma Lazarus.Footnote 61

Figure 9: “More Light Needed,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 16, 1903.

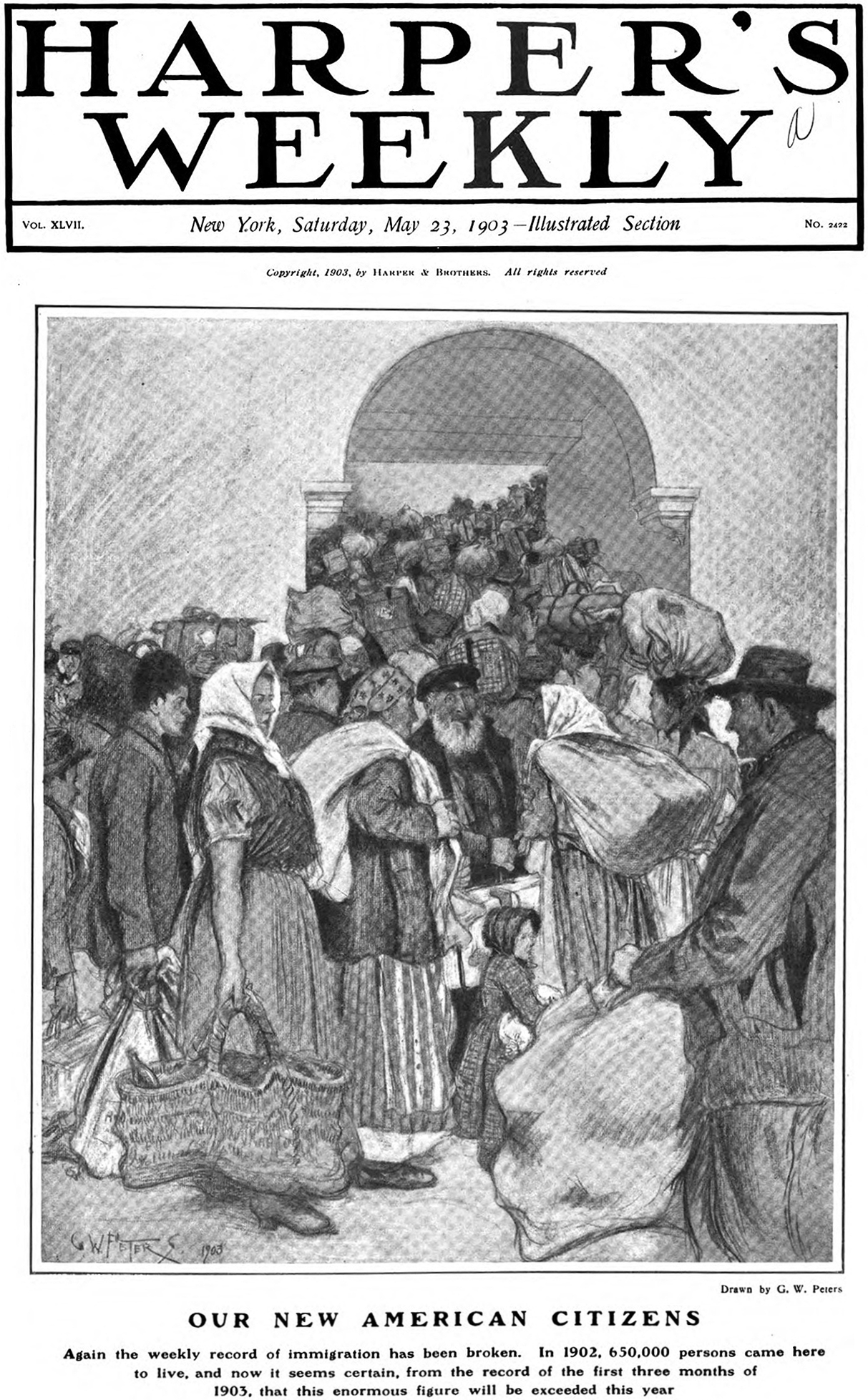

The following Saturday, Harper’s Weekly used G. W. Peter’s illustration of a crowd of immigrants with a Jewish-looking couple right at the center (man in black cap, woman in red head scarf—the original drawing is in color) for its front cover (fig. 10). Peters (about whom almost nothing is known) excelled at humanizing a scene of many people with highly developed portraits of a few individuals as a way of creating a sense of identification between the viewer and the subjects. As in the image for Century Illustrated, the Harper’s piece allows open space in the foreground for the viewer while the crowd crushes through an archway, symbol of triumph, and up the well-lit stairs in their ascent toward citizenship. “Our New American Citizens,” announces the caption, proclaiming as a fact a status that would not yet have been attained by those just off the boat still schlepping their sacks and boxes from home. The Jewish man, the only one to face the viewer, pauses wistfully and considers the momentous transition he is about to make as he leaves behind the world he knew. Thus, although the text below the illustration refers with alarm to record-breaking masses of immigrants, the image encourages one to see the individual in all of his humanity.Footnote 62

Figure 10: “Our New American Citizens,” Harper’s Weekly, May 23, 1903.

This rather poetic tone is very much in evidence on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post on August 8, 1903, drawn by well-known illustrator Edward Penfield. Penfield’s Art Nouveau style, inspired by the graphic work of Toulouse-Lautrec, is more broadly drawn than most contemporary illustrations and features only a few large figures right up against the picture plane (fig. 11). Penfield does not clearly identify these newcomers as Jews, yet as this was the immigrant group receiving all of the attention in the press since May, it is probable the figures were meant to be seen as Jews. Further, the mariner’s cap on the bearded man was closely associated at the time with Russian Jewish style of dress. Majestic in scale, attractive in clean clothing, noble in quiet fortitude and perseverance, the people shown are an inspiring vision. The caption below—“Americans of To-day and To-morrow”—once again defines the subjects not merely as immigrants, or worse—refugees, but as future citizens. The article within, written by Indiana Senator Albert J. Beveridge, an intellectual leader of the Progressive Era, waxed poetic on the idea of America as a blend of materials, with God authoring the recipe. “The republic,” he wrote, “is like some vast crucible into which the High Power of the universe is till pouring various ingredients and compounding them with the pestle of events and the years.” The “Great Chemist of the ages,” he goes on, adds to the pot a dash of Slav, a bit of French, and so on, “reducing the whole to consistency.”Footnote 63 The rest of the article praises the resulting American character, formed as it is from disparate elements, as generous and honest, not doubting for a second the existence of a singular, homogenous American type.

Figure 11: “American of Today and Tomorrow,” The Saturday Evening Post, August 8, 1903.

The top of Beveridge’s article in the magazine’s interior featured a large illustration that offers a remarkably literal visual explanation of this process of Americanization. On the left, several newly arrived immigrants, dressed in traditional clothes, have just disembarked with their baggage from a huge steamship. One bearded young man, shouldering a heavy rucksack, steps into a mortar where he will be pulverized by an eagle-shaped pestle. Emerging out the other side of the bowl, the same young man, now clad in overalls and a worker’s cap, moves in the direction of a steam train, symbol of the industrial economy of the new land. Ahead of him are other “American types” who have gone through this transformation: a shirtless manual laborer, a supervisor in shirtsleeves, and several well-dressed businessmen in shiny top hats. The illustrator, H. L. Sayen, implies here that immigrants, no matter their country of origin, all inevitably become industrious Americans.

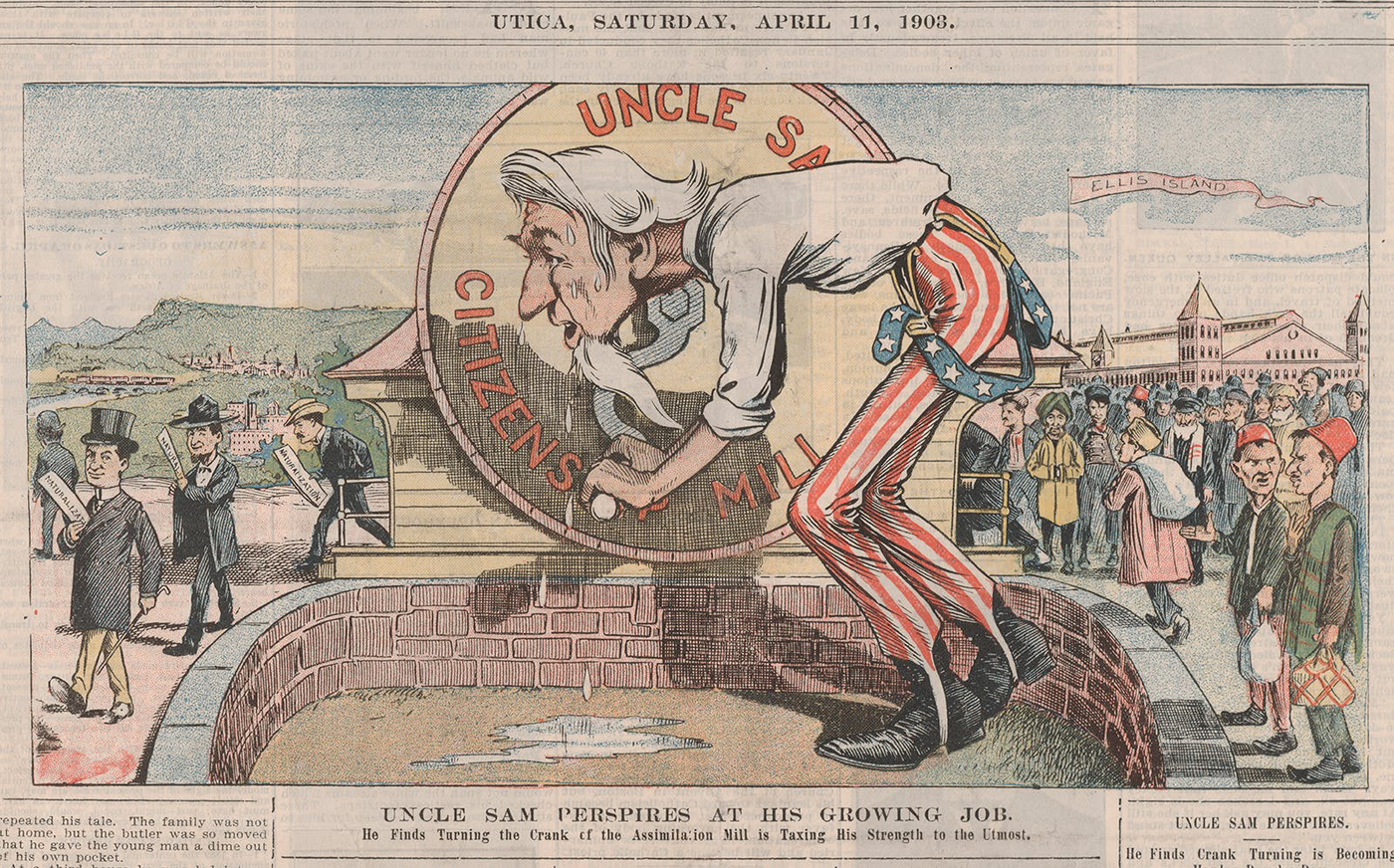

This orderly, even mechanical process was lampooned in a cartoon in the Utica Saturday Globe on April 11, 1903, that featured a heavily perspiring Uncle Sam laboring to crank his “citizenship mill” (fig. 12). A motley crew of new immigrants, including a bearded Jew wearing a tallis (prayer shawl), crowd around Ellis Island waiting their turn to enter the mill. All who enter emerge from the other side transformed into modern-looking naturalized citizens ready to succeed in the new world. The caption complains that Uncle Sam “finds turning the crank of the assimilation mill is taxing his strength to the utmost,” and the rather disdainful tone of the cartoon generally differs from the extreme sincerity of The Saturday Evening Post cover art and accompanying cartoon. Yet Uncle Sam’s efforts pay off in the creation of “real” Americans, thus it is worth it. Of course, the message of both of these cartoons is that the immigrant should leave behind all markers of his country of origin, the sooner the better. Yet even those who retain their ethnic character can find a place in Miss Columbia’s schoolhouse, Uncle Sam’s boarding house, or his Thanksgiving table, as shown on the cover of The Salt Lake Tribune in November 1903. (Caption reads, “And now, my adopted children, we will give thanks that we are all Americans.”) Even the Irishman and the Chinaman have a place at this festooned table, at which the swarthy, bearded Jew sits at the end, side locks akimbo.

Figure 12: “Uncle Sam Perspires at his Growing Job,” Utica Saturday Globe, April 11, 1903.

This article does not propose that American society during the period from 1880–1903 was free of anti-Semitism. It was not. The most infamous episodes of anti-Semitism, such as the rejection of Joseph Seligman, rich New York banker, from lodging in a Saratoga Springs hotel in 1877 and the lynching of Leo Frank in 1915, occurred on either side of the years examined in this article. Universities and law firms maintained quotas that kept Jews out. There were anti-Semitic literary characters and other forms of cultural anti-Semitism, including cartoons and illustrations. Life in America for Jews was not without its problems, but it was far, far better here than it had been anywhere else. The visual material presented supports an upbeat interpretation, in contradiction to recent scholarship on the subject. The visual material also points to another truth: the ideology of America as a haven for the oppressed and the victims of religious persecution played a powerful role in the way Jewish immigrants in particular were perceived. The belief in America as the Promised Land epitomized the nation’s ideals while at the same time encouraged Jewish refugees to hope for a brighter future.