Introduction

Globally, academic institutions measure their activities and output using a range of quality indicator methods. These indicators are used to support academic institutions in measuring academic performance in three areas: research; learning and teaching; and, service and engagement. As most institutions place stronger emphasis on research output, demonstrating the value of this research output to stakeholders is essential (Hajdarpasic, Brew, & Popenici, Reference Hajdarpasic, Brew and Popenici2015). However, measuring research impact has become a wicked problem with academic institutions applying their own values and metrics to demonstrate research impact (Brew, Boud, Namgung, Lucas, & Crawford, Reference Brew, Boud, Namgung, Lucas and Crawford2016; Latour & Woolgar, Reference Latour and Woolgar2013; Santos & Horta, Reference Santos and Horta2018). As noted by Head (Reference Head2019: 182) ‘wicked problems’ refer to issues that ‘are often systemic and interlinked, and therefore require integrated analysis and broad-based discussion among stakeholders’. The measurement of real-world research impact fits this description, due to the complex web of institutions, government bodies, individual researchers, practitioners, and the varying expectations, definitions, values, and metrics that exist between them. Furthermore, there is a clear problem arising, as if these expectations, definitions, values, and metrics are not consistent, or properly considered, the effectiveness and value of research at a global level is diminished.

McKiernan and Glick (Reference McKiernan and Glick2017) further argue that impact measured as translation to application is crucial, particularly when the research is publicly funded. Thus, researchers have a civic duty not only to consider the return on investment for their research, but also to ensure their research has valuable real-world implications (Greenhalgh, Raftery, Hanney, & Glover, Reference Greenhalgh, Raftery, Hanney and Glover2016; Hughes, Reference Hughes2012). However, the current, widely-used measures of research quality and ‘impact’ are impeded by political, social, and environmental pressures within academic institutions, including: competitive research funding; the belief that one must ‘publish or perish’; and the constant tension between research and teaching requirements (Santos & Horta, Reference Santos and Horta2018; Shattock, Reference Shattock2014). This wicked problem led us to pose the first research question guiding this study:

RQ1. How should we measure research impact and value?

While the varying institutional expectations discussed above make it difficult to capture and report impact using traditional metrics, there are critical global indicators that can be used as a standard to provide consistency and drive the production of valuable research. One such example is the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, also referred to as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations [UN], 2016).

The SDGs were created in response to the conclusion of the millennium development goals in 2015 (Disley, Reference Disley2013). Seventeen goals have been created, with 169 corresponding targets that relate to the world's most pressing challenges. Examples of SDGs include reducing poverty, increasing economic prosperity, promoting social inclusion and environmental sustainability, and working towards peace and governance to all by 2030. The targets, which have been developed based on the most current research, constitute a world-wide action plan to achieve sustainability in developing and developed countries (Disley, Reference Disley2013; Salvia, Leal Filho, Brandli, & Griebeler, Reference Salvia, Leal Filho, Brandli and Griebeler2019). The SDGs were accepted by all UN member states in 2015 (United Nations [UN], 2016) and – since then – have been used as a blueprint to translate these high-level goals into national strategies and plans (United Nations [UN], 2018). The UN continuously monitors its member states' efforts and achievements towards achieving the goals, and reports those, alongside areas that require further attention, in its annual ‘Sustainable Development Goals Report’ (United Nations [UN], 2019).

Recent literature has begun to recognise the potential value of using the SDGs as a means of measuring research impact (Bebbington & Unerman, Reference Bebbington and Unerman2018; Leal Filho et al., Reference Leal Filho, Azeiteiro, Alves, Pace, Mifsud, Brandli, Caeiro and Disterheft2018), and along these lines, we propose that the SDGs may be an effective way to assess research impact and real-world value. Accordingly, it becomes important to understand how research can be better aligned with the specific targets set out in the SDGs, and this formed the basis of the second research question for this study.

RQ2. How can academics, practitioners, and policymakers align their research agendas with the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Existing systems of measuring research quality and impact, such as journal rankings and citation impact metrics, have been criticised (Moosa, Reference Moosa2016; Sangster, Reference Sangster2015), yet with few alternatives available, these are still the predominant systems used by most institutions. As with any shift in policy, any potential change to the measurement of research impact and value would need to be accompanied by significant changes to institutional metrics and systems. The third research question for the study considers this issue by exploring the operational considerations that would go hand in hand with any changes made to the way that research impact is measured.

RQ3. How would alignment with the SDGs be operationalised in an academic environment?

Beyond the expectations and policies set by individual institutions, academic research is often guided by network organisations, such as conferences and special interest groups (Jordan, Sloan, Bentley, & Langerud, Reference Jordan, Sloan, Bentley and Langerud2018). As the data for this study were exclusively collected from academic gatherings under the banners of such organisations, it was appropriate to explore the potential influence that these network organisations could have.

RQ4. What role could network organisations such as the Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management (ANZAM) and the Continuous Innovation Network (CINet) fulfil in aligning research agendas with the SDGs?

The next section of the paper will explore the background to this research, highlighting the value and relevance of the SDGs to the measurement of impact and quality of academic research.

Background

Agarwal et al. (Reference Agarwal, Durairajanayagam, Tatagari, Esteves, Harlev, Henkel and Ramasamy2016) identify more than two dozen metrics used to measure scholarly research impact, including the h-index, journal impact factor, the Eigenfactor, and article metrics. These are known as bibliometrics and they are often used as ways to measure research quality and impact within academic institutions. While bibliometrics have long been used to make comparisons between researchers and institutions, Agarwal et al. (Reference Agarwal, Durairajanayagam, Tatagari, Esteves, Harlev, Henkel and Ramasamy2016) advise that these comparisons should only be made between researchers who are in the same discipline and at the same stage in their career, as bibliometrics can increase bias if used incorrectly. For example, when one researcher is compared to another who has more experience in their field of research, the researcher with more experience will likely have a higher publication record, citation count, number of downloads, number of successful grants and research projects, journal impact factor, and Eigenfactor due to the differences in the length of time and opportunities they have had in their careers (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Durairajanayagam, Tatagari, Esteves, Harlev, Henkel and Ramasamy2016).

In addition, research institutions are often of the view that publications in highly ranked journals demonstrate impactful research because they have undergone a peer-review process by the research community, meet a minimum standard and have high citation impact factors. However, Seglen (Reference Seglen1997) argues that the latter is an overly complicated and basically useless indicator of real-world impact, because it is only a measure of scientific utility, not scientific quality. Furthermore, Agarwal et al. (Reference Agarwal, Durairajanayagam, Tatagari, Esteves, Harlev, Henkel and Ramasamy2016) warn researchers to be wary when new web-based tools are made available by databases to measure quality and impact because these measures are frequently owned by publishing companies. As a result, publishers generate a bias when promoting claims of their journals' reach and impact (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Durairajanayagam, Tatagari, Esteves, Harlev, Henkel and Ramasamy2016). Importantly though, these metrics are only measures of scholarly (or citation) impact and not real-world research impact. Thus, although there are several metrics available to measure research quality and impact, most only measure certain characteristics of research quality. They do not measure real-world impact and are far removed from being able to establish the value for investment return on research funded by tax-payer dollars.

Indicators used to measure academic performance have resulted in placing unnecessary pressure on academics and the Schools in which they are employed, leading to an increase in rewards for promotion but a decrease in research integrity and real-world impact (McKiernan & Glick, Reference McKiernan and Glick2017). These methods are detached from the overarching goal of adding value to society through understanding and solving key problems and opportunities. Jones (Reference Jones2017) believes using quantitative citation-based methods to measure quality is a fallacy and that such numbers are not a valid representation of research quality. Furthermore, Brew et al. (Reference Brew, Boud, Namgung, Lucas and Crawford2016) argue that the academic environment imposes particular ways of thinking about research upon academics that are strongly framed by quality and performance measures and metrics. These current measures are for academic institutions only and do not provide a valid representation or measurement tool for true quality or real-world, impactful research.

Moreover, these bibliometric-based methods most widely adopted by academic institutions have several additional limitations (Drew, Pettibone, Finch, Giles, & Jordan, Reference Drew, Pettibone, Finch, Giles and Jordan2016). For example, they may not recognise academics who are actively taking part in research because the research they are involved in is not necessarily measured by the current metrics in place (Brew et al., Reference Brew, Boud, Namgung, Lucas and Crawford2016; Lucas, Reference Lucas2006). Examples of this often include interdisciplinary research or research in new fields not well-served by the large publishing houses.

To maintain their employment, academics must continuously meet key performance indicators (KPIs) set by Schools and Universities, and when these KPIs are based on citation bibliometrics as pushed by the global publishing industry, there is little incentive for academics to seek to measure the real impact of their research on end-users. Rather than incentivising business academics to focus on existing business and societal challenges, Chapman (Reference Chapman2012) concludes that a focus on research outputs as measured by publication bibliometrics tends to drive Business Schools away from creating real solutions for such challenges. This is often reinforced by research institutions, where pay rises and promotions are awarded based upon publications in high-ranked journals that are of high ‘quality’, and although these citations are viewed and used by academics; industry leaders and policymakers, including large funding bodies of universities, such as the Federal Government, rarely ever read these ‘highly-ranked’ publications (Glick, Tsui, & Davis, Reference Glick, Tsui and Davis2018).

Glick, Tsui, and Davis (Reference Glick, Tsui and Davis2018) believe that current academic incentives do not reward quality or replicability, rather they reward quantity and novelty. It is argued that the current measures of quality and performance are problematic and do not encourage meaningful research impact. Nevertheless, meaningful research impact is often achieved despite the current ill-fitting and contested performance measures and, according to McKiernan and Glick (Reference McKiernan and Glick2017), this impact should go well beyond merely counting citations and media hits. We propose that the same line of argument should be applied to the current system of journal rankings.

These traditional measures of research impact, in conjunction with the current funding model for Business Schools, mean that there is very little consideration of the real impact of our business research (Doyle, Reference Doyle2018). In terms of investment, McKiernan and Glick (Reference McKiernan and Glick2017) argue against the time and effort spent for the purpose of ‘just another’ publication. Glick, Tsui, and Davis (Reference Glick, Tsui and Davis2018) further claim that stakeholders frequently pay for research that rarely benefits them. Therefore, it is becoming increasingly evident that the current measures of quality and impact of business research, and performance, are of questionable value to society. It is also evident that the current measures do not align with required current and future research agendas of government agencies and policy agendas.

Research now requires transformation and needs to serve others beyond academia to generate real-world impact (Glick, Tsui, & Davis, Reference Glick, Tsui and Davis2018). This view is gathering considerable traction in academia and business through organisations such as the Responsible Research in Business and Management (RRBM) Network initiated by a gathering of influential international academics in 2014. The network now includes over 1,000 members, at least 85 co-signers, nearly 900 endorsers, more than 55 institutional partners, and six pioneer Schools (RRBM, 2017). In their attempt to address the wicked problem of achieving meaningful research outcomes, the RRBM Network developed a 2030 vision, in which Business Schools and scholars worldwide will have transformed their research, focusing on responsible science, and the production of credible knowledge that assists with addressing the real-world problems important to business and society (RRBM, 2017).

New methods are available to measure research impact and therefore ‘quality’, which are most suited to the current institution of academia but are not being implemented. To understand how these methods can be used effectively the following question needs to be reconsidered: what is ‘real’ research impact?

According to the Australian Research Council, ‘research impact is the demonstrable contribution that research makes to the economy, society, culture, national security, public policy or services, health, the environment, or quality of life, beyond contributions to academia’ (Australian Research Council [ARC], 2015a). Research impact needs to extend beyond academia in an effort to generate legitimate and responsible research (McKiernan & Glick, Reference McKiernan and Glick2017). In the specific context of management research, Simsek, Bansal, Shaw, Heugens, and Smith (Reference Simsek, Bansal, Shaw, Heugens and Smith2018) argued research must impact ‘management practice’, but almost as a side-note also stated that management research can have significant impact through the role of the scholar as an educator and – more broadly – by contributing management research as a tool to address some of the bigger wicked problems in the world (George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi, & Tihanyi, Reference George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi and Tihanyi2016). Unfortunately, none of these authors have considered how such ‘real’ research impact can be appropriately measured within academic environments.

Additionally, more attention needs to be given to end-users, who are an integral component in determining impact (Williams & Grant, Reference Williams and Grant2018). While Simsek et al. (Reference Simsek, Bansal, Shaw, Heugens and Smith2018) suggested that the rather narrow group of management practitioners is the main end-user of management research, they also imply that students are also end-users, and by referring to management research's ability to contribute to wicked problems, they further imply another end-user of management research: society. By seeing society, more widely, as the end-user, management research could align its impact with that required of businesses as the latter should also add value to society (Wang, Tong, Takeuchi, & George, Reference Wang, Tong, Takeuchi and George2016).

Consequently, research agendas need to change, especially in Business Schools where the research focuses mainly on individuals, teams, and the organisation, but generally without consideration of the broader societal and global impact of the research. A focus on individuals, teams, and organisations and a consideration of the broader societal and global impact, however, are far from mutually exclusive. In fact, George et al. (Reference George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi and Tihanyi2016) argued that that management researchers are in a unique position to contribute to wider impact by addressing individual and organisational challenges that are ubiquitous to the solution of the bigger societal challenges in the world. George et al. (Reference George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi and Tihanyi2016) further stated that management researchers actually want to have such societal and global impact, but often feel that the academic structures (including some of the previously mentioned pressures, such as the need to measure research with academic bibliometrics) do not allow for them to contribute in this manner. Although it is difficult to capture and report this wider impact, there are critical global indicators that can be used to drive our research (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Cook, Sokona, Elmqvist, Fukushi, Broadgate and Jarzebski2018). As previously mentioned, one such example is the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, consisting of 17 SDGs and 169 corresponding targets.

The SDGs aim to enhance the globalisation of knowledge and facilitate the implementation of research across several sectors and regions (Sachs, Reference Sachs2012). Universities, with their unique position in society have a critical role to play in the achievement of the SDGs. Arguably, the SDG goals cannot be achieved without the contribution of the University sector. Sachs (Reference Sachs2012) argues that academia, governments, international institutions, private business, and society, are all required to work together to ensure the success of the SDGs. Supporting this view is a range of evidence emerging in recent reports that demonstrates a significant uptake of the SDGs as a way of measuring research impact (Körfgen et al., Reference Körfgen, Förster, Glatz, Maier, Becsi, Meyer, Kromp-Kolb and Stötter2018; Leal Filho et al., Reference Leal Filho, Shiel, Paço, Mifsud, Ávila, Brandli, Molthan-Hill, Pace, Azeiteiro, Ruiz Vargas and Caeiro2019; Saric et al., Reference Saric, Blaettler, Bonfoh, Hostettler, Jimenez, Kiteme, Koné, Lys, Masanja, Steinger, Upreti, Utzinger, Winkler and Breu2019).

The research agenda for the SDGs moves beyond only researching for high-income countries, which often makes it difficult to transfer the research to lower income countries (Greenhalgh et al., Reference Greenhalgh, Raftery, Hanney and Glover2016). The SDGs instead require researchers to think about the global impact of their research in relation to the 17 goals and their corresponding targets. We therefore propose that the SDGs should be used as quality indicators and drivers within academia to measure real-world impact and research quality.

This paper begins to unpack current bibliometric measures of research outputs and proposes an alternative way to measure research value in line with the global ideal of measuring ‘real-world’ impact. As detailed in the Introduction, this paper addresses the following four research questions:

RQ1. How should we measure research impact and value?

RQ2. How can academics, practitioners, and policymakers align their research agendas with the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

RQ3. How would alignment with the SDGs be operationalised in an academic environment?

RQ4. What role could network organisations such as the Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management (ANZAM) and the Continuous Innovation Network (CINet) fulfil in aligning research agendas with the SDGs?

The next section of this paper will provide an explanation and justification of the qualitative approach adopted for this study, an outline of the world café methodology used to collect data for the study, and an overview of the questions that participants were asked in the world café sessions.

Method

We developed a workshop that enabled researchers to constructively and openly consider and discuss how the SDGs could be incorporated into University, particularly into Business School, research agendas. The workshop focused on exploring how researchers, as individuals and members of different academic groups, would be able to engage with the SDGs. Importantly, we wanted to understand how this engagement with the SDGs could result in real-world impact.

A world café design was implemented to aggregate dialogue data from two different workshops in an open and welcoming environment. The world café approach is a process of democratic conversation that not only enables active dialogue amongst participants in a relaxed setting, but also facilitates collaborative inquiry and cross-pollination of thoughts and ideas amongst participants (Anderson, Reference Anderson2011; Brown & Isaacs, Reference Brown and Isaacs2005; Fouché & Light, Reference Fouché and Light2011; Jorgenson & Steier, Reference Jorgenson and Steier2013). According to Anderson (Reference Anderson2011), the world café design creates an ideal setting for knowledge translation, whereby diverse opinions are shared and concepts are challenged, thus new learning occurs for each participant involved. The world café approach requires small groups of participants to sit around tables to discuss thought-provoking questions in multiple conversational rounds; in a traditional world café format, participants circulate between tables at the end of each round, thus adding to discussions with other participants and facilitating interaction across the different tables (Maskrey & Underhill, Reference Maskrey and Underhill2014). Facilitators should be placed on each table and summarise the main points of the previous round discussions at the start of each new round (Anderson, Reference Anderson2011). It was the interactive and collaborative nature of the world café format that was crucial in this study to explore and understand how participants currently engage with SDGs, how they are currently being implemented in universities, and how they could be implemented in future, resulting in real-world impact.

The workshops were conducted with nine groups at two conferences. The Continuous Innovation Network (CINet) in Ireland, September 2018, in which a total of 17 participants from diverse European countries contributed in five groups; and the Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management (ANZAM) in Auckland, New Zealand, in December 2018, where a total of 26 participants, two discussion leaders, and six facilitators partook in the workshop (six groups). Participants self-selected to participate in the workshops, thus suggesting some interest in the workshop content. The total amount of participants was 51, all of whom were researchers working at universities, at various stages of their academic careers.

Recognising that a norm of between 15 and 60 participants is likely to be considered efficient, the actual number depends on the research purpose (Saunders & Townsend, Reference Saunders and Townsend2016). Given that the purpose of the workshops was to elucidate and explore a range of insights, we contend through the demographic data, that the number and range of participants provided a sufficient and credible sample. The participants were diverse in terms of stage in their career (including research higher degree students [n = 16], early and mid-career academics [n = 21], and senior academics [n = 14]), providing an overall age range of 24–63.

The workshop began with an introduction to research impact and information about the SDGs, as well as an overview of current University engagement with the SDGs, and how Universities can improve their engagement with the SDGs derived from desk research of University websites. This part of the workshop was delivered by the discussion leaders and it set the context for the world café conversations. For the world café itself, participants were seated at round tables (between five and six participants per table), which invited open conversation, modelled after a generic café environment (Brown & Isaacs, Reference Brown and Isaacs2005). Participants were provided with a folder, which contained a consent form and information about the SDGs. All participants gave their consent to participate at the world café as a data collection approach, although provisions were available should any participants wish to be excluded from data collection.

Each table had a facilitator, whose role was to ensure that the table remained on task and that everyone was given the opportunity to express their opinion. In addition, the facilitator took notes about the discussion taking place on a large piece of paper in the centre of the table with coloured markers, and immediately after the workshop, prepared reflection notes, which included a more detailed account of their observations and richer description of the table discussions. All facilitators were researchers with experience of facilitation of group discussions and group interviews, as well as qualitative data collection and analysis, so as to fulfil their dual role of facilitating the discussions and preparing meaningful research notes (MacFarlane et al., Reference MacFarlane, Galvin, O'Sullivan, McInerney, Meagher, Burke and LeMaster2017).

During the world café part of the workshop, four questions were addressed, one question per round, whereby each round lasted 10 min. These questions were aligned to the study's four research questions, and designed to ensure that the workshop theme, which focused on the SDGs and real-world impact, remained a central focus in each round:

(1) How can we better align our current individual research agendas to particular SDGs?

(2) What are the steps required to begin using the SDGs to help drive our institutional research agenda?

(3) What role can network organisations (such as ANZAM/CINet) play in focusing attention on the application of the SDGs in our research activities?

(4) How can we measure research quality, keeping our end-users in mind?

The design of the workshop's world-café was slightly modified from the traditional world café design. Usually, participants are required to move between tables after the conclusion of each round, which allows participants to meet other people and aims to widen their perspectives through others' differing and/or similar observations or opinions (Brown & Isaacs, Reference Brown and Isaacs2005; Prewitt, Reference Prewitt2011; Steier, Brown, & Mesquita da Silva, Reference Steier, Brown, Mesquita da Silva and Bradbury2015). However, we modified this traditional approach and instead had participants remain at the same table to discuss each of the four questions. Although this modification reduced the opportunity for participants to obtain views from other tables, it enabled participants to build on what was discussed in the previous rounds. This resulted in deeper conversations, building on the collective knowledge of the group, and also removed the need for facilitators to constantly repeat the discussion points from previous rounds. Therefore, this modification allowed us to overcome the limitations we faced due to time constraints and large numbers of participants in the workshops. At the same time, the modification allowed us to retain the strengths of the world café format as we were able to provide a space that enabled constructive and amicable discussions per round, even though the groups remained the same. In addition, the appropriate facilitation of the groups also supported democratic conversations by ensuring that no single participant dominated the discussion.

Once the four rounds concluded, an open discussion began. In the world café literature this is referred to as the harvesting phase (Brown & Isaacs, Reference Brown and Isaacs2005). During this phase, discussions that occurred at individual tables are shared with the whole group (Brown & Isaacs, Reference Brown and Isaacs2005). Firstly, we asked facilitators to briefly summarise one of the questions to explore patterns, themes, and deeper questions experienced in the smaller group conversations (Aldred, Reference Aldred2009; Fullarton & Palermo, Reference Fullarton and Palermo2008). All participants were then asked as a large group to engage in an open conversation with each other and the facilitators. This harvesting of information allowed the whole workshop group to reflect on what was discussed both verbally and visually, using the notes taken by facilitators (on the large pieces of paper and coloured markers on each table). Immediately following the workshops, we collated all notes produced during the workshop, and the facilitators were asked to provide more detailed reflections on the process. These facilitator reflections typically included observations of the discussions held at their tables, as well as richer responses to the workshop questions. All facilitators provided reflections following the workshops, and these reflections were added to the data for this study.

The harvesting phase is an integral component of the world café design. For each of the workshop groups further discoveries and insights were made through this sharing of information. According to Brown and Isaacs (Reference Brown and Isaacs2005), the harvesting phase allows for patterns to be identified and the collective knowledge of the group can be observed by everyone. It was clear that participants realised from the four rounds and the whole group discussion that the possibility for actionable research aligned with the SDGs to create real-world impact is both warranted and achievable.

Following the steps described above, the next steps in conducting the research involved an in-depth analysis of the data collected at all world café sessions and reflections collected from facilitators. This process of analysis is discussed further in the following section of this paper.

Analysis

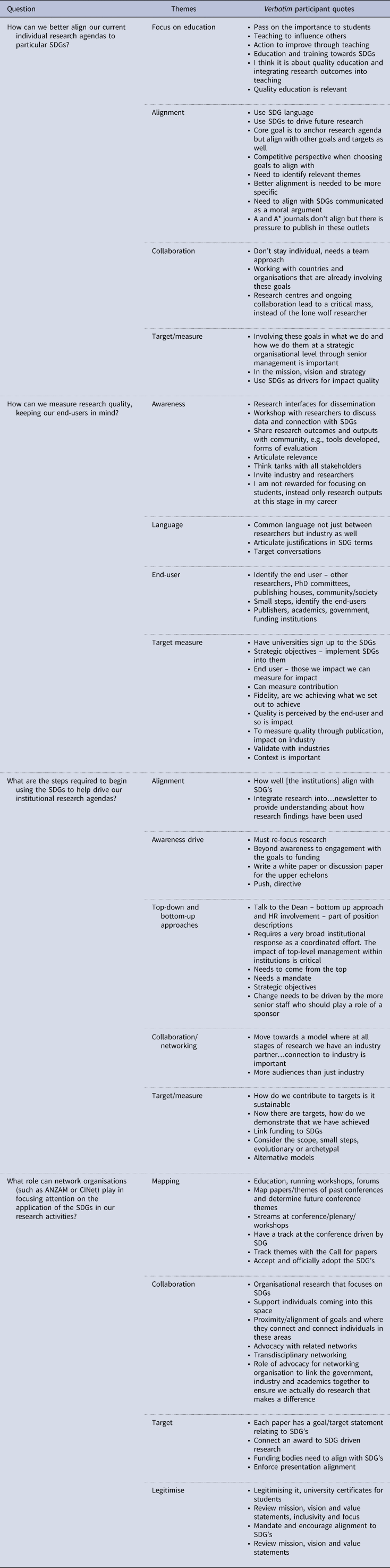

Text data were created by aggregating the discussion notes on the large pieces of paper on each table and the reflection notes and observations for each question provided by the facilitators. There were over 30 pages of reflection notes and observations entered into QSR NVivo for the purpose of organising the sources, classification codes, and themes. This allowed for integration and comparison of the different data sources with the aim to identify convergences and contrasts of the data collected. Data were analysed by two researchers via constant comparison within the questions (are participants saying the same thing?) and within the workshops (are groups saying the same thing and if not, what is different?). The process in NVivo was a staged approach commencing with organising the data, synthesising the data, and searching for patterns and determining the findings guided by the research questions. For example, reflections, notes, and observations were coded by connecting each item, word, sentence, and passage to a theme. This yielded a coding tree with themes such as ‘awareness’, ‘collaboration’, and ‘language’ (see Table 1).

Table 1. Qualitative findings – themes and supporting quotes

The meta-analysis of the data included identifying theme-connections from the perspective of the participants and examining the links and the connections between the concepts (Bryman, Reference Bryman2016; Quinlan, Babin, Carr, & Griffin, Reference Quinlan, Babin, Carr and Griffin2019). As such the themes were derived from the data but guided by the questions posed in the world café. Table 1 contains a list of themes, which emerged from the data for each of the four questions, as well as supporting quotes from the workshop participants.

In terms of seeking feedback from participants on the findings, workshop participants who viewed an earlier version of this paper 12 months after the workshop was held, commented that they had observed a considerable increase in their own and their colleagues' awareness of SDGs (as discussed within the ‘SDG awareness’ theme in the workshops) over the intervening year.

The data only derived from two workshops, with a relatively small number of participants (n = 51), which presents a limitation of this study. Nonetheless, the diversity of participants in terms of geographical location, career stage, and research focus provided diverse viewpoints, which nonetheless converged to a suite of common themes. Moreover, the data derived from the notes and reflections of workshop facilitators; although these were written up immediately after the workshops, an element of recollection bias may be present as the data depended upon the facilitators' memory of the discussions and their notes during the workshop.

Every effort was made by facilitators to note and recall the views expressed by participants, but it is possible that some meaning has been lost in the process of writing up the data, which constitutes another limitation of this study. However, as the findings discussed in the next section demonstrate, the responses from participants demonstrated a substantial level of congruency, suggesting that there was minimal loss of data clarity as a result of selective memory bias or misinterpretation. Both facilitators and participants were from the broad field of management. While this provided deep insights into the views of one particular group of researchers, it also constitutes a limitation to generalisability of the findings as scholars from other fields within the business community, such as finance or marketing, may have other views.

Results and Discussion

This section presents the findings, according to the themes that emerged in line with the four research questions. Table 1 has presented these themes in detail, alongside illustrating quotations from the workshop participants. It is interesting to note that despite the diversity within the workshops, particularly the fact that one took place in Europe and the other in New Zealand, the themes that emerged from the analysis are common across both workshops.

Research question 1 was set at the broad level of measuring research quality in general, and was addressed in the world cafés with the following workshop question:

How can we measure research quality, keeping our end-users in mind?

The measurement of research quality and/or impact was seen as a difficult step by our workshop participants because of the highly embedded nature of bibliometrics in School and University perceptions of what constitutes ‘quality’ research. The fact that such bibliometrics are also used as performance measures, and promotion criteria only add to the difficulty in making the required changes. Our workshop participants felt that better identification of the end-users of our research; developing improved measures for end-user evaluation of research outcomes; ensuring a common language is adopted by both researchers and industry/society end-users; and the establishment and promotion of improved collaboration and communication between business researchers and research end-users can all assist in the development of improved research quality and impact measures. Assistance will come with the development of the new ARC Research Impact assessment exercise, which will continue to assess how well researchers and institutions engage with end-users of research (Australian Research Council [ARC], 2015b). However, as the next round of this exercise will not take place until 2024, we need to get better at collecting end-user evaluation of our research outcomes on a timely and continuous basis. We should also be working to provide additional measures for University and School performance that include end-user evaluation of research outcomes and reduce the sole focus of such systems on citation bibliometrics and funding dollar measurements.

The second research question focused on how academics, practitioners, and policymakers can align their research agendas and measure real-world impact in an academic environment, was addressed with the following question during the world café sessions:

How can we better align our current individual research agendas to particular SDGs?

Participants felt that an integration of the SDGs into our teaching (as well as our research) was an important issue in building broad commitment to the sustainability targets and aligning individual research agendas. They also felt that the complex issues highlighted within the SDGs will require effective alignment between individual research agendas and institutional and government research performance measures and directions. This includes using common language, improved communication to the wider society, and a reduction of the focus on journal ranking as the only measure of research quality and value. Collaboration between researchers in different institutions and across different disciplines was also seen as essential in tackling these issues. Incorporating the SDGs into School and University mission and vision statements was seen as a positive way to boost awareness and involvement from academic staff regarding the SDGs and their individual targets.

It should be noted that this research question included the additional stakeholder groups of practitioners and policymakers, as there was the potential for representatives from these stakeholder groups to attend the workshops. However, all participants at the workshops were University researchers, and as such, the perspectives of practitioners and policymakers cannot be included. However, the important role of these stakeholder groups cannot be ignored, so the discussion will still consider implications for practitioners and policy.

Research question 3 focused on operationalising the SDGs in an academic environment, and was addressed in the world café sessions with the question below:

What are the steps required to begin using the SDGs to help drive our institutional research agenda?

The workshop participants felt that establishing a clear alignment between the SDGs and institutional research agendas was an important first step in solidifying the use of SDGs. One suggestion for how to establish this alignment was to ensure that institutional communication devices such as newsletters were used to inform staff about the importance of the SDGs, and how current research findings align with them. This focus on communicating the importance of the SDGs was also reflected in the workshop participants' view that awareness was an important early stage of driving the use of SDGs in institutional research agendas.

The question of whether the use of SDGs needs to be emphasised by senior management (top-down) or independently carried out by individual staff (bottom-up) was discussed in depth, and most workshop groups concluded that there needs to be a combination of these approaches. Many participants indicated that widespread change is only possible when senior management are driving it, yet also suggested that these senior managers would be more likely to emphasise the use of SDGs if they could see that their staff were already engaging with them. Outside of drivers within the institution itself, some workshop participants indicated that the use of the SDGs would be more feasible in a model where all stages of research were connected with an industry partner. Finally, workshop participants all referred to the importance of finding a way to set achievable targets aligned with the SDGs. One suggestion for how this could be achieved would be through the development of a funding model that specifically linked funding to the SDGs.

The fourth and final research question focused on the role of network organisations, and was addressed in the world café sessions with the question below:

What role can network organisations (such as ANZAM or CINet) play in focusing attention on the application of the SDGs in our research activities?

In response to this question, many workshop participants indicated that the way in which conferences were organised could play a major role. Specifically, suggestions were made that conferences could have a dedicated stream focused on SDGs, where researchers in this area could connect and help promote this research agenda. Going further than this, some participants suggested that conferences could align all their streams with the SDGs, to provide an even clearer focus on the importance of this agenda. However, while actions such as this were considered to be important, workshop participants typically believed that the most significant role that network organisations could play was one of legitimising and supporting collaboration between researchers focused on the SDGs. In providing this supportive and collaborative environment, network organisations are able to bridge disciplinary boundaries, which is a key element in addressing the SDGs.

Overall, there was a general agreement amongst the participants for SDGs to become part of everyday academic work. For example, participants advocated the previously mentioned model where, at all stages of research, there is an industry partner connection and a recognised alignment to the associated SDG. Additionally, because a focus on SDGs is relatively new in academia, there needs to be increased awareness of how SDGs can demonstrate real-life impact. Therefore, to create awareness of the utility of SDGs for academic work, participants suggested the need to consider SDGs and targets in both teaching and research. In an effort to fully engage with the SDGs, some participants suggested that Business Schools formally connect SDGs and targets to the curriculum, and mandate SDGs to drive future research. Therefore, we believe a focus on the SDGs in academic work is warranted.

Despite the positive response regarding the recognition that SDGs are important drivers for future academic work, the difficulty lies in how we contribute, measure, and align our performance to the current goals and targets, and therefore whether the contribution to the goals and targets is sustainable. For example, there is little expert knowledge available for academics to assist them in their endeavour to plan new research projects, examples of published work that explicitly address these goals and targets are few and far in between, and measures of what exactly constitutes measurable impact on SDG targets is not currently clarified. At present, relevant A and A* ranked journals (using the Australian Business Deans Council, ABDC journal ranking as an example) do not align with the SDGs, but there is much pressure within Universities to publish in these outlets. While some journals request impact statements, such as practice impact and policy impact, most do not make known their specific sustainable development targets. Therefore, much work is needed to support academics in their future research and dissemination pursuits. The same can be said about funding applications, although there seems to be more movement towards societal relevance and impact of the research outcomes beyond academia (Australian Research Council [ARC], 2015a, 2015b; National Health & Medical Research Council, 2018). As a result, universities are commencing mapping their research outputs to the SDGs (Griffith University, 2019).

Such mapping at a University level is an important first step towards the integration of SDGs into Universities, as highlighted in the following list of mechanisms that has been proposed by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN Australia/Pacific, 2017):

(1) Map what they are already doing in relation to the goals and their targets,

(2) Build internal capacity and ownership of the SDGs,

(3) Identify priorities, opportunities, and gaps,

(4) Integrate, implement, and embed the SDGs within University strategies, policies, and plans, and

(5) Monitor, evaluate, and communicate actions on the SDGs often.

As this section has shown, our data from the world café workshops support these high-level actions and add valuable insights also into individual academics' views towards these steps and what they themselves can add to achieving this integration of SDGs within the University sector.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The purpose of this paper was to unpack the current bibliometric-focused measures of research ‘quality’ and to propose an alternative way to measure research value in line with the global ideal of measuring ‘real-world’ impact, through the use of the United Nation's SDGs. In an endeavour to understand how researchers can align their research agendas and measure real-world impact, how this can be operationalised in academic environments, and what role networking organisations can play in this change, we analysed research data resulting from a number of world café workshops. The main themes that emerged from the participant narratives included: driving awareness and normalising the language around SDGs; the need for collaboration with industry partners; a call for defining the targets and how to measure the impact of research that addresses them; and, aligning research agendas to the SDGs and associated targets. Consequently, the key recommendations for Universities that came out of these findings were:

(1) Align University mission and vision statement with the SDGs and targets, in order for individual researchers to weave these goals and targets into teaching and research practices and agendas;

(2) Align the SDGs and targets to performance management practices to ensure accountability and commitment to the pursuit of these goals at individual and team levels;

(3) Encourage a closer relationship with industry to ensure sustainability and real-world focus is embedded within the research from the outset; and

(4) Commit to the professional development of academics and students to the SDGs and targets to ensure sustainability of commitment going forward into practice.

The key recommendations for networking organisations resulting from this study are as follows:

(1) Embed and advocate for the achievement of SDGs and targets being implemented; and

(2) Provide a platform for deep relationships to be created between government, industry, and network members.

This paper reported on two academic groups who we asked to rethink research impact beyond academia by considering the possible role of the 2015 UN SDGs. These recommendations may provide a platform for the acknowledgment and recognition of real research impact in Business Schools. The UN SDGs and related targets are a powerful guide to solve wicked real-world problems and may thus provide academic guides and measures that have the potential to pay back public investment in business research. It is clear from both developments in the field and the responses provided by workshop participants that the SDGs are increasingly coming to the forefront of academic institutions' and individual researchers' agendas. These rapid developments in the field, alongside the small sample size, focus on management research, and highly exploratory nature of the findings from this study, mean that further research needs to be undertaken in this area to: (i) better understand other stakeholders' views on this issue; (ii) establish clear measures of research impact aligned with the SDG targets; (iii) explore further opportunities for positive action; and (iv) provide an increased volume of evidence of researchers' views – including researchers in fields other than management – on the issues discussed in this paper.

Dr. Geoffrey R. Chapman is a Lecturer in Human Resource Management and Organisational Behaviour at CQUniversity's School of Business and Law. Since completing his PhD in 2012, his main research interests have been in the areas of personality profiling, positive psychology, group dynamics and communication.

Ashley Cully is a second year PhD candidate in the Department of Business Strategy and Innovation (BSI) at Griffith University, Australia. Her research is focusing on the development of a systematic sampling technique for qualitative researchers. Ashley holds a Bachelor of Psychological Science at Griffith University and was awarded a First-Class Honours degree (Business) from Griffith University.

Jennifer Kosiol is a PhD candidate within the Department of Business, Strategy an Innovation within the Griffith Business School. She has extensive executive experience in tertiary public healthcare services and healthcare delivery. Her interests focus on organisational behaviour and leadership and management in healthcare contexts. She is a Certified Health Executive and Fellow of Australasian College of Health Service Management and an Associate Fellow of the Higher Education Academy.

Dr. Stephanie A. Macht is Senior Lecturer in Strategic Management at CQUniversity's School of Business and Law. Her main research interests focus on entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education.

Ross L. Chapman is Professor of Management and Director of Postgraduate Studies at the School of Business and Law, CQUniversity (Sydney campus). Prior to 2014, he was Head of the Deakin University's Graduate School of Business and prior to 2010, he was Professor of Business Systems at the University of Western Sydney. Between 1979 and 1985, Ross worked for several large multinational companies in technical and QC/QA management positions. He has taught and researched predominantly in the areas of quality, innovation and technology management. He is author or co-author of three books and over 100 book chapters, refereed journal and conference papers in the above areas. Ross has been a Non-Executive Director on the Boards of three not-for-profit organisations including that of the Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management (ANZAM) where he was the 2011 President.

Janna Anneke Fitzgerald completed her PhD in Commerce in 2003. Since then she has mainly focussed on organisational behaviour and leadership in change management as well as closing the research to practice gap through research translation, implementation and sustainability in healthcare contexts. She is currently a research Professor of Health Management at Griffith University, has completed 17 Higher Degree by research Students, over 140 peer reviewed publications and a little more than $27 mil external income, leading large competitive grants.

Frank Gertsen is Professor in Innovation Management at Aalborg University, Department of Materials and Production. Gertsen has been active in teaching and research of industrial management and innovation management for more than three decades, with recent focus on radical/breakthrough/disruptive innovation processes. His international experience includes visiting professorships at the University of Western Sydney, Hong Kong City, and visiting scholar, Stanford University. He is the author of 140+ research publications, and he has acted as journal editor. He is a member of Connect Denmark (supporting entrepreneurship), and university representative of the Federation of Danish Industries (DI) group of New Product Development Managers in Northern Denmark. Gertsen holds an MSc and PhD in Industrial Management from Aalborg University.