Introduction

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Shanghai was made up of two central areas – the International Settlement and the French Concession, which were bordered by two Chinese-administered areas to the north (Zhabei) and the south (Nanshi, the former walled city) (see Figure 1). The film industry started early in Shanghai but its development was uneven in the different districts.

Figure 1. General map of Shanghai (main administrative urban areas), 1914–43

Source: www.virtualshanghai.net/Maps/Collection?ID=2179, accessed 22 Dec. 2018.

On 11 August 1896, at the Xu Garden in Shanghai, some films were screened by a French projectionist, an event which is generally considered by historians as the first film screening in China.Footnote 1 Subsequently, some films were screened in the Astor House Hotel, the Arcadia Hall of the Zhang Garden, the Tian Hua tea garden, the Qi Garden, the Tongqing teahouse and so on.Footnote 2 In 1908, Antonio Ramos, a Spanish businessman, established the first specialized cinema – the Hongkew Theatre, at the junction of Zhapu and Haining Road. From 1908 to 1914, the development of the film industry was fairly slow. Until 1914, there were only 8 cinemas in Shanghai.Footnote 3 This situation did not change until the late 1920s. In 1925, there were only 27 cinemas in the whole of Shanghai, but they still accounted for more than a quarter of all movie theatres in China (including Hong Kong and Macao).Footnote 4 According to my statistics, from 1908 to 1943, more than 100 cinemas were built in Shanghai and most of them were located in the foreign settlements. Why did cinema owners choose the settlements to build their theatres in? If the stable political environment in the foreign settlements was regarded as the primary factor, why was the number of movie theatres in the International Settlement much higher than that in the French Concession? In the International Settlement, why were movie theatres mostly distributed in the north of Suzhou Creek (Suzhou he) in the early twentieth century? In the late 1920s, the number of cinemas on the south bank of Suzhou Creek in the International Settlement gradually increased. What was the reason for this phenomenon? By building on previous scholarly works, and combining archival data and other historical documents, this article explores these questions by means of the Geographical Information System (GIS). It provides an in-depth analysis of the macro- and micro-level factors that caused such distribution. Through this study, readers can understand and visualize the development of movie theatres, the process of urbanization in Shanghai and the formation of its cultural space.

Characteristics of the spatial distribution of movie theatres in Shanghai from 1919 to 1943

The Hongkew Theatre built in 1908 was the first independent cinema in Shanghai. Although it was simple and crude, the emergence of such a specialized space meant that film was no longer dependent on other entertainment and leisure facilities, and began its own journey of independent development. Meanwhile, the emergence of specialized cinemas meant that a stable film market began to form, which then stimulated the development of film production, and enabled the film industry to prosper.Footnote 5 In the following years, the number of movie theatres increased gradually in Hongkew District.

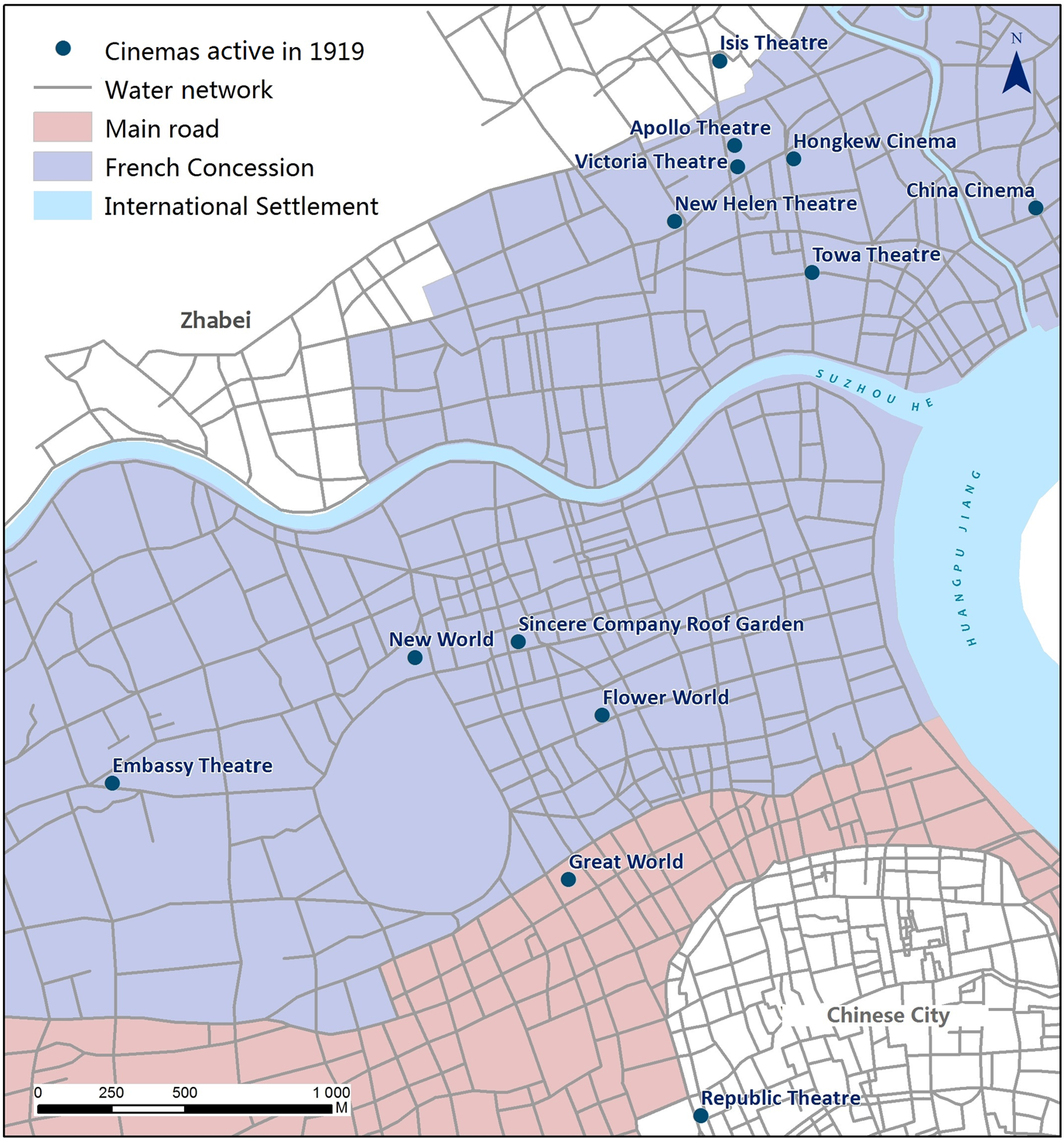

The map of the spatial distribution of movie theatres in 1919 (see Figure 2) clearly shows the location of the major locations where films were screened.Footnote 6 Hongkew District was the centre of film screenings, as many independent movie theatres were located there. But in the south of Suzhou Creek, most film screenings took place in amusement halls, such as the New World Roof Garden and the Great World. In addition, the Olympic Theatre was the first cinema in the Western District of Shanghai.Footnote 7 In addition to the above-mentioned areas, Nanshi, the old imperial city, originally a political, economic and cultural centre, attracted a large population. After the opening of the port of Shanghai, although the old city lagged behind the settlements in terms of urban construction, it was still one of the most important cultural centres in Shanghai. Besides the Republic Theatre, according to newspaper advertising at that time, there was another movie theatre, Haishenlou, which operated from 1915 to 1918 in Nanshi. These two cinemas mainly targeted the middle and lower classes, and ticket prices were relatively low.

Figure 2. The geographical distribution of movie theatres in Shanghai in 1919

In the 1920s, people became increasingly aware of movies and began to visit the theatre. In this period, the number of cinemas grew significantly, as did the projection industry. In Shanghai, especially at the centre of the settlements, many independent cinemas were established. As shown on the map of the spatial distribution of cinemas in 1926 (see Figure 3), Hongkew District, as a film screening centre, continued to exert a strong influence on surrounding areas, for example, Baoshan District (north of the International Settlement). Many movie theatres were constructed in the boundary area between the International Settlement and the Chinese territory. At the same time, in the Central and Western Districts of the International Settlement, the number of specialized cinemas increased.Footnote 8 In the French Concession, there were fewer cinemas than in the International Settlement and there were only two specialized cinemas – the Empire Theatre in Joffre District and the Republic Theatre located in Mallet District.

Figure 3. The geographical distribution of movie theatres in Shanghai in 1926

In 1927, the Nanjing National Government was established, and the external political environment of Shanghai stabilized. The newly established Shanghai Municipal Government promoted the development of the newly formed Chinese municipality. From the late 1920s to the early 1930s, the construction of cinemas in Shanghai bloomed. The archives of the International Settlement show that in 1928 the Shanghai Municipal Council (SMC, which ran the International Settlement) received six applications to build cinemas.Footnote 9 By 1932, there were 8 cinemas in the Chinese territory (see Figure 4).Footnote 10 From 1927 to the end of January 1932, the movie industry in Shanghai grew rapidly; more than 20Footnote 11 new movie theatres were established, out of which approximately 11 were in the International Settlement and 10 in the French Concession. There were approximately 5 cinemas in the Chinese territory. In addition, in the extra-settlement roads, there was a movie theatre, the Orpheum Theatre, which opened in 1927.

Figure 4. The geographical distribution of movie theatres in Shanghai in 1932

However, in 1932, the January 28 Incident meant huge economic losses for the Chinese film industry, as during this month-long war, many film production companies were destroyed by fire. At the same time, many movie theatres in the Chinese territory and at the junction of the Chinese territory and the International Settlement, such as the New Helen Theatre,Footnote 12 the Isis Theatre, the Odeon Theatre, the Universal Theatre and the Zhabei Theatre, were also destroyed.Footnote 13 Most of these studios and cinemas destroyed in the war were not re-established for economic reasons. In 1933, the number of movie theatres in the Chinese territory was reduced to four or five.Footnote 14 In the following decade, cinemas opened and closed, but there were never as many in the Chinese territory as in 1932. Although the development of the film industry in Hongkew District did not stop thanks to the continual emergence of new cinemas, it gradually declined in comparison with that in the Central District of the settlements, located to the south of Suzhou Creek. Here, luxury cinemas were built one after the other, including the Grand Theatre and the Metropole Theatre, which were constructed in 1933 and cost millions. The film industry in the French Concession was subjected to a significant change, with cinemas along Joffre Avenue newly equipped and decorated. Going to the first-run theatres – such as the Cathay Theatre and the Nanking Theatre – became a craze.Footnote 15 According to the magazines of the time, on an average day, the number of movie-goers reached 35,000.Footnote 16 Shanghai's film industry was booming, and the Chinese film industry had entered its first golden age.Footnote 17

Nevertheless, the film industry was not exempt from the economic recession of the early 1930s, which was aggravated by the ensuing Sino-Japanese War.Footnote 18 The development of the Chinese cinema industry slowed down, from the January 28 Incident in 1932 to 1936, when there were only two new cinemas in the French Concession. In the International Settlement, three new cinemas opened in Hongkew District, two in the Eastern District, two in the Western District and two in the Central District. When compared to the period between early 1927 to the end of January 1932, there was a general decline in the construction of cinemas. From 1936 to the middle of 1937, the film industry recovered from the economic crisis. In 1937, the ‘August 13 Incident’ marked the beginning of the Japanese attack and later the occupation of Shanghai. The period of national crisis which followed had a severe impact on the Shanghai film industry and the entire entertainment industry.

After the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, the Japanese army occupied all areas of the city except the French Concession and the International Settlement south of Suzhou Creek. At the beginning of the war, the settlement authorities enforced martial law in their respective areas where most of the shops closed down and public transportation was completely suspended.Footnote 19 Many of the cinemas were affected by the war, and some were even converted to refugee shelters.Footnote 20 According to the statistics of the SMC, after the outbreak of the war in 1937, there were only 25 cinemas in the foreign settlements, 12 fewer than in the previous year.Footnote 21 The film industry in Shanghai stagnated. However, the wartime situation was soon reversed. The battle of Shanghai ended in November 1937, but by early October, some cinemas had already opened up.Footnote 22 The SMC statistics showed that by the end of 1938 the number of cinemas in the settlements had increased to 35, and in 1939 had grown to 40, exceeding the pre-war level. In 1941, there were 48 cinemas, among which 13 were located in the French Concession, more than there had been before the war.Footnote 23 These statistics take into account the cinemas in the north of the International Settlement, which were located in the south of Suzhou Creek. After the Japanese occupation of Shanghai, most of the cinemas in the Chinese territory were expropriated by the Japanese. But since the Japanese authorities recognized the extra-territorial status of the settlement, some cinemas located in the International Settlement, north of Suzhou Creek which was occupied by the Japanese, such as the Ritz Theatre, Willie's Theatre and the Eastern Theatre, still operated as private businesses until the outbreak of the Pacific War.Footnote 24 Probably owing to the impact of the war, almost all the newly built cinemas were located in the settlements, south of Suzhou Creek. According to statistics (see Figure 5), between 1938 and 1943, in the International Settlement, nearly all of the newly built cinemas were located in the Western District, while in the French Concession, the additional cinemas were distributed mainly in Joffre District, the Central District and Foch District.

Figure 5. The geographical distribution of movie theatres in Shanghai in 1942

From the 1910s to the early 1920s, most of the movie theatres in Shanghai were in Hongkew District, north of Suzhou Creek, and extended to Baoshan District.Footnote 25 But in the south of Suzhou Creek, the film venues were based at the amusement halls. The location of amusement halls coincided not only with the geographical centre of the Shanghai settlements, but also with the urban commercial centre, which had the highest population density. As a new means of entertainment, film was promoted by the popularity of these entertainment facilities before a specific group of cinema-goers was formed. In the mid-to late 1920s, although the film screening centre of Shanghai was still in Hongkew District, the popularity of film extended beyond Suzhou Creek, to the south of the settlements. On the south bank of Suzhou Creek, the movie theatres in the Central District of the International Settlement were centred on Nanjing Road, Zhejiang Road and Ningbo Road, near the racecourse, and around Bubbling Well Road in the Western District. The cinemas in the French Concession were mainly distributed at the junction of the two settlements, such as Avenue Edward VII, Avenue Foch and Avenue Joffre. The south bank of Suzhou Creek, where the International Settlement and the French Concession were located, became the centre of movie projection, especially after the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937. There were many reasons for the geographical distribution of the cinemas in the settlements. As mentioned above, the war was an unavoidable external factor, but what were the other reasons for such a distribution?

Reasons for the changes to the spatial distribution of cinemas in the settlements

Administration policies

The settlement authorities were responsible for a certain amount of urban planning. The authorities in the French Concession were most interested in residential housing, while the International Settlement provided an unrestricted environment for economic development.Footnote 26 Following these different developmental objectives, the two authorities conducted a preliminary plan for the localization of the various industries, which would influence the geographical distribution of cinemas under their own jurisdictions. Compared to the International Settlement, the authorities in the French Concession had more influence in the construction of cinemas. In 1924, the Conseil d'administration municipale de la concession française de Changhai (CDM) began to implement the ‘classification system’ to control all businesses in its territory. According to this regulation, these businesses were classified in terms of impact on the residents’ lives. The business classification offices, as well as the business classification committee and its board, not only examined the places of business, but also conducted a detailed investigation and assessed the surrounding neighbourhood of each place (including the size of the business, the nature and content of the production, even the operator's own moral situation).Footnote 27 Large-scale industrial and commercial operations that affected residents’ lives (mainly categories A and B) were blocked outside the central area. According to an English guidebook of the time, ‘the French authorities…refuse to allow businesses and factories to be established in residential roads’.Footnote 28 The leisure and service industry, which belonged to category C, included cafés, taverns and cinemas, and was the least harmful to the environment.Footnote 29 In the French Concession, category C places were mostly located in the residential area of Rue Massenet, Avenue Joffre and the surrounding streets. In these areas, if the business was harmful in terms of noise, health, safety and even aesthetics, its licence was rejected or revoked. In 1936, the Lawn Cinema, an outdoor theatre, applied to open a door in the palisade at the junction of Route Cardinal Mercier and Avenue Joffre, and its request was refused by the CDM for reasons of aesthetics and traffic.Footnote 30 From the maps of the geographical distribution of cinemas over the years, we can see that in the French Concession, the cinemas, especially the high-end ones, were situated mainly in the above areas.

The SMC did not implement a system of business classification, but they carried out controls on the entertainment venues based on the relevant by-laws of the Land Regulations.Footnote 31 Through the issuance of business licences, the construction of cinemas was efficiently controlled. According to the ‘Cinematograph Licence’ and the relevant documents, the SMC focused on three factors in the construction of the theatre: first, fire control security systems, secondly, the traffic concerns and thirdly, the opinion of residents near the cinema.Footnote 32 As the movie-goers usually needed to take transportation, before the opening or after the end of the film, there would be traffic jams. For example, on several occasions, at the end of a movie in the Cathay Theatre, the police would send reinforcements to direct the traffic, and prohibit any vehicles from going into Route Cardinal Mercier.Footnote 33 Hence, the surroundings of a cinema needed to include not only a parking space but also a wide road. Sometimes, in order to resolve the traffic problem, the authorities would widen the road, but that did not always work. In 1925, there was an application to open a cinema on Nanjing Road, but despite the proposed widening of Nanjing Road, the applicant's request was firmly rejected by the Shanghai Municipal Police, who based their assessment on their experience in handling traffic at the Carlton Cafe, the Olympic and the Apollo Theatres and the Town Hall.Footnote 34 Finally, the SMC allowed the applicant to open the cinema on the Bund because the latter had enough parking spaces.Footnote 35 Subsequently, the applicants applied to open small cinemas in Nanjing Road and specifically pointed out that their cinemas were mainly aimed at the less wealthy and therefore would not cause traffic congestion.Footnote 36 Finally, the application was approved, provided that the licensee agreed to co-operate with the police in traffic regulations and their construction.Footnote 37

In addition to the traffic problems, when the SMC issued a cinema construction licence, the surrounding environment of the cinema and the opinions of the surrounding institutions or residents were also taken into account.Footnote 38 For example, in 1927, a businessman wanted to build a cinema at the corner of the junction of Shandong Road and Fuzhou Road.Footnote 39 The Lester Chinese Hospital on Shandong Road strongly opposed the proposal, since the noise emanating from entertainment venues until late at night would disturb the patients.Footnote 40 The SMC refused to issue the licence in consideration of the public interest.Footnote 41 The above case shows that cinema owners had to take into consideration the authorities’ administrative regulations and follow their guidance when selecting the site of cinemas. However, as an industry, they had to make sure that cinemas would be profitable, which was the main consideration in the selection of their location. And the key to profitability was choosing sites in commercial areas where they would target larger audiences.

Population density and population structure

In urban geography, population and density are important indicators with which to define a city.Footnote 42 In the first years after the opening of Shanghai port, most of the population in the settlements was concentrated in the downtown area,Footnote 43 while the east and north area around Tilanqiao, and the area of North Sichuan Road, were more sparsely populated.Footnote 44 In 1895, the population of the Eastern and Northern Districts was almost equal to that of the Central District, and by that time, 67.5 per cent of the population of the International Settlement was concentrated in the Central District. By 1925, the population of the International Settlement had more than doubled, but in the Central and Northern Districts, the population declined by 38.9 per cent, while the population in the Eastern and Western Districts increased by 61.1 per cent. By 1935, 70 per cent of the population in the International Settlement was concentrated in the Eastern and Western Districts (see Figure 6)Footnote 45 The population density was one of the important considerations for cinema site selection, which explains why early cinemas were clustered on the north bank of Suzhou Creek. From the 1920s onwards, the number of cinemas in the Eastern and Western Districts of the International Settlement increased rapidly with the growth of the population in these regions. According to the author's study, from 1920 to 1932, there were about five cinemas in the Eastern District, and about six in the Western District without taking into account the open-air cinemas.

Figure 6. The population density in foreign settlements, 1935

Source: www.virtualshanghai.net/Maps/Collection?ID=434, accessed 22 Dec. 2018.

The Eastern District of the French Concession was a well-known commercial area with a Sino-foreign co-habitation pattern, and the population density was high. As the settlement grew, its surface area was much larger than that of the old district. In contrast, the new Central and Western Districts were characterized by luxury residences and the population density was relatively low. The total population of the French Concession in 1936 was 454,231, of which 7,370 were in the Eastern District, 64,153 in Mallet District, 154,692 in Joffre District, 181,688 in the Central District, 71,570 in Foch District and 24,758 in Pétain District.Footnote 46 It can be seen that the population of the French Concession was heavily concentrated on Avenue Joffre and in the Central District. In these two populated areas, there were not only a large number of comfortable houses, but also many entertainment facilities. The cinemas in the French Concession were also located here.

The conflicts in 1937 radically and definitively changed the distribution of the population in Shanghai. In 1936, there were about 1,180,000 people in the International Settlement, and about 470,000 in the French Concession. According to the survey by the Japanese army on 1 February 1942, there were 1,580,000 people in the International Settlement and 850,000 in the French Concession, with a significant increase of 780,000 people in total in the two settlements.Footnote 47 The growth of the urban population in the city stimulated not only the commodity market, but also the service industry, entertainment industry and other non-commodity markets.Footnote 48 As a result, the film industry in the settlements did not stagnate because of the war, but boomed on account of the huge consumer population. The influx of a large number of refugees expanded the market demand, while funds poured into the settlements, as refugees sought shelter. The economic activity in the settlements gradually recovered, and the desire for culture also stimulated the recovery of the film industry. The surge of population and capital provided the most fundamental conditions for the ‘deformity’Footnote 49 development of the film industry. The type of cinema was related to the nature of the population that the cinema could reach.

As mentioned above, the initial development of the cinema was partially determined by the foreign presence. After the Americans set up Hongkew District, north of Suzhou Creek, as the American Settlement, a greater number of foreigners resided there. In the following few decades, the number of foreigners in the centre of the International Settlement (Nanjing Road district) stagnated, while it increased significantly in other districts, including the Northern District (Hongkew District), Eastern District (Yangshupu area), Western District (Huxi area) and extra-settlement roads, especially in the Northern District. For example, the number of foreigners in the centre of the International Settlement in 1935 was only 1,418, accounting for only 4 per cent of the total number of foreigners in the International Settlement, while the number of foreigners in the Northern District was 11,484, accounting for 30 per cent. The number of foreigners in the extra-settlement roads was also more than 10,000, and the number of foreigners residing in the two districts was more than half that in Shanghai city.Footnote 50 This may explain why most of the early cinemas were built in the north of the International Settlement.Footnote 51 During this period, 9 out of 10 people in cinema audiences were foreigners, while there were very few Chinese.Footnote 52 According to the statistics of 1920, there were about 10,097 foreigners in Hongkew District, accounting for 43.32 per cent of the total foreign population in Shanghai.Footnote 53 Most foreigners who resided in the north of the International Settlement were Japanese. It is worth noting that their understanding of film was much greater than that of the Chinese people. In 1925, Shanghai was home to the most developed film industry in China, but it was still highly unsophisticated compared with Japan and the United States. At that time, China, including Hong Kong and Macao, had more than 100 cinemas in total, but Japan had 800 cinemas; in the United States, New York City alone had 500 cinemas. The Japanese also built several cinemas in Hongkew District, which showed Japanese movies.Footnote 54 Ramas set up the Olympic Theatre in the western area of the International Settlement, because the latter was also populated by foreigners.

The prosperity of the early film industry in Hongkew District was also connected to the Cantonese. As Canton was accustomed to foreign trade, many Chinese compradors in the foreign firms were Cantonese. As Shanghai was opened after the Opium War, one foreign business after another set up branches in Shanghai. A large number of Cantonese compradors and businessmen engaged in importing and exporting arrived in Shanghai.Footnote 55 Today's Tiantong Road (the section between Sichuan Road and Henan Road) was formerly named ‘Guangdong Street’ because the Cantonese gathered there.Footnote 56 In the 1920s, the number of Cantonese residing in Shanghai was about 50,000, of which about 60 per cent lived in Hongkew District.Footnote 57 Unlike other residents in Shanghai, many Cantonese had been abroad, and were used to seeing films. In addition, most of the locals running movie theatres were Cantonese in early Shanghai. Cantonese businessman Ziyi Deng was one of the shareholders of the New Helen Theatre. In 1917, he and another Cantonese businessman Huantang Zeng purchased the Chinese Theatre in North Sichuan Road and transformed it into the Isis Theatre, as a branch of the New Helen Theatre.Footnote 58 In 1925, Bozhao Zheng, a Cantonese businessman and comprador of the British American Tobacco Company, invested in the construction of the Odeon Theatre, which was Shanghai's most luxurious cinema in the 1920s. Muxia Yu pointed out clearly in his book that these cinemas in Shanghai were built by the Cantonese.Footnote 59 These facts indirectly confirm that the Cantonese greatly appreciated film. This may explain why the early theatres were situated away from the centre of the settlements and were concentrated in Hongkew District, north of Suzhou Creek. Until the 1920s, the number of Shanghai cinemas doubled by comparison with the 1910s. At that time, for the Shanghainese, ‘going to Hongkew District’ meant ‘watching movies’. Even now, Haining Road and Sichuan Road are still the centre of the Shanghai film industry.Footnote 60

The high population density in the Eastern and Western Districts in the International Settlement was related not only to their surface area, but also to the nature of the population in each district. There was a considerable industrial development in the early twentieth century, especially in the Hudong industrial district on the north side of the Huangpu River and the Huxi industrial district located on the south bank of Suzhou Creek and Caojiadu.Footnote 61 In the Eastern and Western Districts where workers gathered, some less prestigious theatres catered for these workers as their target audience, such as the Eastern Theatre which opened in 1929 at Haimen Road and the Western Theatre which opened in 1932 at Xinzha Road. Both cinemas catered for audiences that came from the lower strata of society, and screened three or four runs of foreign films.

The total number of foreign residents in the French Concession in 1936 was 23,398, of which 10,012 stayed in the Central District, 8,535 were concentrated in Foch District and only 589 people were in the Eastern and Mallet Districts. In the French Concession, 80 per cent of foreigners were concentrated in the district around Avenue Joffre.Footnote 62 The International Settlement and the Eastern District of the French Concession became an office area with many foreign companies, and enjoyed commercial prosperity. Meanwhile, the west and the centre of the French Concession gradually became a residential district for the middle and upper classes.

The American and the European residents mainly lived in the north part of the central area, north of Avenue Joffre, Avenue du Roi Albert, Route Vallon, Rue Bourgeat, Route Cardinal Mercier and Avenue Foch, and especially on both sides of Avenue Joffre. Shops, public utilities and entertainment facilities that catered for their local culture and living customs were accordingly located in these districts.Footnote 63 As a high-ranking community, the Central District accommodated serious consumers. The film industry in this district started late, but the movie theatres there were high-end, such as the Cathay Theatre. The Cathay Theatre was located in Avenue Joffre where many European and American residents were concentrated. As one of the best cinemas in Shanghai, it was frequented by foreign audiences.Footnote 64

Relationship between the spatial distribution of cinemas and traffic

From the above analysis, we can see that the theatre distribution mainly followed the principle of proximity. The cinemas were built around areas with high population density and numerous target audiences. This phenomenon was particularly common in the early development of the cinema, when cinemas were usually located in foreign quarters with high population density. However, regional distribution and changes in the population were closely related to the traffic factors. Along with the development of the city and the changes in modes of transportation, the recreational activities space expanded gradually, which led to changes in the distribution of urban entertainment. The regional distribution of population, traffic factors and the distribution of entertainment facilities affected each other.

From the beginning of the twentieth century onwards in Shanghai, the sedan chair, carriage and rickshaw had gradually been superseded by the tram, car and taxi, making longer journeys possible. According to Jiajun Lou, urban entertainment venues were usually distributed in the centre of the city and their quantity decreased in proportion to the distribution of residents within the city. Before the opening of Shanghai port, Nanshi followed this traditional distribution pattern in which the entertainment venues were mainly located around the City God Temple, which was close to the County Hall. With the help of various modes of modern transportation, the public no longer followed the traditional circular motion pattern, but a regular linear pattern along the traffic path.Footnote 65 The opening of tram and bus lines which passed through important or well-known public entertainment places made visiting them more convenient and promoted the development of the entertainment industry. The number 1 tram from Jing'an Temple to Hongkew Park passed eight cinemas: including the Carter Cinema, the Embassy Theatre, the Grand Theatre, the Carlton Theatre, the Victoria Theatre, the Apollo Theatre, the Isis Theatre and the Odeon Theatre.

With the growing size and variety of urban businesses, many well-known commercial districts subsequently followed the early Nanjing Road with regard to the distribution of population density and the development of transport. Many firms and shops with a remarkable variety of commodities lined both sides of Avenue Joffre and Sichuan Road. Some business districts were also set up, such as Jing'an Temple, City God Temple and Caojiadu. Commercial prosperity dictated the routine mobility of the urban population. Therefore, the public transport companies in Shanghai, especially the foreign enterprises in the settlements, began to take the commercial networks into consideration when opening routes where there was a large degree of flux in the population.Footnote 66 In the Chinese-administered territory, the administrative office of the public bus service in the Shanghai Public Utility Alliance also recorded that bus routes ‘were subject to go through public institutions, lively markets and well-known public recreation places’.Footnote 67

Similarly, the entertainment venues were usually located in places that were convenient to reach by public transportation. In 1924, the garden of St George restaurant that served as an open-air cinema was opened in Bubbling Well Road; the bus stop for the only bus route of the International Settlement at the time was located in front of St George restaurant.Footnote 68 Three cinemas were located on East Seward Road, on the north bank of Suzhou Creek. On this road, a tram route was established early on, which made travel there more convenient.Footnote 69 The opening of the public transport lines not only made it easier to get to local amenities, but also stimulated people's desire for and awareness of entertainment and leisure. When the Rialto Theatre opened, it catered for students as the target audience. Since students did not have much money, the theatre drew attention to three economical means of transport: tram, bus and trolleybus were all mentioned in its opening advertisement in order to attract its target customers.Footnote 70

The development of rickshaws, trams, trolleybuses and other traffic routes expanded the scope of people's activities, facilitated the separation of residential and commercial/entertainment areas and accelerated the pace of the modern urbanization of Shanghai. Cinema reached a wider audience group, and played an important role in establishing a thriving entertainment industry. However, according to the statistics of the Shanghai Social Affairs Bureau, the average wage rate for all industrial workers in Shanghai from 1930 to 1934 was less than 0.6 Yuan per day (average daily working time was about 10 hours).Footnote 71 At that time, the ticket price for third-class trams was about 0.02 Yuan for one stop, and about 0.03 Yuan for 3 stops. If an industrial worker made a round-trip, it would cost 0.06 Yuan, which accounted for one tenth of his daily wage. Obviously, it was difficult for the workers to form a stable customer base for public transport enterprises.Footnote 72 So usually they had to live in the shantytowns around the factory, and formed a social group largely ignored by the tram company when creating a new transportation route.Footnote 73 But these consumers were noticed by the cinema owners. So it is easy to understand that the three- or four-run cinemas were mostly located near the workers' settlements, because they could be fairly sure of an audience. According to the transport ticket price at that time,Footnote 74 the low-income class could not afford the expense of taking the tram or bus to the office,Footnote 75 so public transport users were mainly the urban middle-income class and the higher strata of the low-income class, including some low-income foreigners. Therefore, the second-run theatres were not usually constructed around the residential areas, but were located in the area where transportation could be accessed conveniently.

Like public transport, the taxi industry also rapidly developed to meet the needs of the upper classes. In 1937, there were 44 taxi companies in Shanghai, with about 1,000–1,200 taxis and about 20,000 staff. An average of 35,984 visitors took the taxi every day which amounted to 13,134,160 passengers annually. Obviously, the taxi had become an important part of the urban public transit networks in Shanghai, and was chosen by a considerable number of the upper middle class for outside recreation or short-distance travel activities.Footnote 76 When issuing construction licences for the cinemas designed for the upper classes, the settlement authorities usually took into account the traffic conditions and the amount of parking space.

The relationship between spatial distribution of cinema and cultural space

In addition to the above factors, the owner also had to consider if the surroundings of the cinema provided a suitable cultural environment. For example, as aforementioned, in 1925 a proprietor preferred to accept the harsh requirements of the SMC for constructing a theatre in Nanjing Road rather than accept its proposal of constructing the theatre on the Bund. The principal reason lay in the different cultural atmosphere of the Nanjing Road and the Bund Districts due to their different urban functions. As the centre of the ‘Ten Miles of Luxury’, the Bund embraced the Public Garden, the Palace Hotel, the Shanghai Club, the Capitol Theatre building (the Capitol Theatre was located here) and other cultural institutes and leisure facilities, as well as the offices of major banks, such as HSBC and China Merchants Bank. Therefore, it was not only a political and cultural centre, but also a business and financial centre. However, the adjacent Nanjing Road was a famous commercial centre, where a large number of famous stores were located, such as Sincere, Wing On, Sun Sun and The Sun. As Ou-fan Lee observed, ‘moviegoing easily fits into the new lifestyle, just as movie theatres became a visible institution – together with coffeehouses, dance halls, and department stores – in the new urban space of leisure and consumption’.Footnote 77 In addition, the racecourse and its surroundings formed the earliest centre for commercial consumption, culture and entertainment in the International Settlement.

From the maps of cinema distribution in the 1930s, it can be seen that the cinemas were mainly distributed around the racecourse, and extended to the west along Nanjing Road and Bubbling Well Road, which constituted the main entertainment area of the foreign settlements, and of Shanghai city itself. Here, cinemas, cafés, Chinese traditional theatres, dance halls, parks and racecourses formed the city's cultural centre, where people could relax after a day's work on the Bund. The construction of a new cinema in such an area dedicated to leisure and entertainment could serve to promote the movies at a time when this new entertainment had not yet been universally accepted. And once generally accepted, it would fit perfectly into the surrounding cultural atmosphere and create harmony. Hongkew District north of Suzhou Creek was also one of the multifunctional centres in Shanghai, which combined commercial consumption, leisure and cultural exhibitions. In the early days after the opening of the settlements, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Japan, Italy and other countries opened up their consulates in this area.Footnote 78 Modern civilization had a subtle influence on the Hongkew people, where a free and open atmosphere promoted the exchange between Chinese and Western cultures. Secondly, compared with the central areas of the International Settlement, the land prices in Hongkew District were lower in the early years. Furthermore, it had a background in culture and education, which attracted the majority of the population. At the same time, Hongkew District was packed with foreigners. The number of foreign firms, financial institutions, factories and other institutions increased significantly in these areas, which formed a new urban entertainment consumer market. The mobility of the modern entertainment industry made Hongkew District an important area of Shanghai.

The scenery of the French Concession was serene and atmospheric, different from that of the International Settlement, especially along its main street, Avenue Joffre. As one local aficionado observed, on Avenue Joffre ‘there are no skyscrapers, no especially large structures’, but ‘every night there are the intoxicating sounds of jazz music coming from the cafés and bars that line both sides. This is to tell you that there are women and wine inside, to comfort you from the fatigue of a day's toil.’Footnote 79 Going to the cinema to watch foreign movies was more than a recreation and could also convey a comforting feeling of blending in with the surrounding exotic culture. Take the Cathay Theatre for example: it was surrounded by Shanghai Park, Verdun Garden and some senior residential communities, such as Astrid apartments and Cathay Mansion. These foreign buildings were built before or after the construction of the cinema. On the other side of the road, the French Club was also one of the city's most exclusive social venues in Shanghai. The Orthodox Church of Our Lady Hall which was located on the west of Rue P. Henry, and St Nicholas’ Church on the east, which was not far away, were also the most important religious centres for Russian expatriates. As a first-run cinema, the luxury Cathay Theatre was in harmony with the surrounding cultural environment.

Going to the cinema greatly enriched the spectators’ lives. As Ou-fan Lee noted,

it was the architecture of Shanghai's newly built movie palaces, together with its marble-floored lobbies and Art Deco design, that became the ‘spectacle’, dazzling the eyes and senses of the spectators, a world unlike anything they had experienced before, either in public or in private. This novel public setting added immeasurably to the enjoyment of the films themselves. Moviegoing in Shanghai, therefore, had become a new social ritual.Footnote 80

As mentioned earlier, the cinemas were mostly located in the cultured atmosphere of the commercial areas or the more scenic residential areas. The Western District of the International Settlement and the French Concession became the upscale residential district of Shanghai from the late Qing Dynasty onwards, with a large number of villas and garden houses. Thus, some cinemas of relatively high standing, such as first-run cinemas – the Grand Theatre and the Cathay Theatre – were situated there. These cinemas mainly screened foreign films and most of the audiences consisted of foreigners. The Chinese who went to the luxury cinemas were mostly from rich families or the bourgeoisie.Footnote 81 The second-run cinemas were located in the downtown area, such as the famous Nanjing Road, Avenue Joffre, Sichuan Road and other commercial streets. Most Chinese went to the second- or third-run cinemas, while those from the lower ranks of society could only watch the worn copies which were a few minutes shorter than the original versions in suburban districts. The third- or fourth-run cinemas were mainly located in the north and east of the International Settlement, which chiefly served the citizens from the middle and lower classes. The subsequent-run theatres, especially the cinemas that showed domestic productions, were mainly located in the east and west of Shanghai, the factory area and railway station area, Nanshi, and the Caojiadu area, inhabited by workers and peddlers in poor living conditions. In these areas, most of the houses were shantytowns with very few new public cultural facilities, just a few cinemas, and many old teahouses and Chinese traditional theatres. These cinemas were relatively basic, and lacking in cultural atmosphere.Footnote 82 So, in Shanghai, watching film there was not only a cultural enjoyment, but also a symbol of identity.

The cinema distribution in Shanghai showed the above characteristics in general before the war in 1937 which made most cinemas, including the new ones, move to the settlements. According to Davis' research, for distribution purposes, the major studios classified 30 different markets in the United States based on the well-known ‘run-zone clearance’ system.Footnote 83 According to this theory, each market contained numerous different zones, within which the theatres were further classified by run (first-, second-, third-, etc.). Downtown theatres in major cities were designated as first-run and played the newest films at the highest prices. Second-run theatres charged less and were located in a city's business districts, like subsequent-run theatres. Normally, it took two to six weeks for the films to be transmitted to the next-run theatres.Footnote 84 The spatial distribution of cinemas in Shanghai, especially in the settlements, followed the American cinema market, reflecting Shanghai's urbanization process from another angle.

Conclusion

Although Shanghai's leading daily newspaper – Shen Bao – published advertisements for films as soon as they arrived in China at the end of the nineteenth century, as a new form of art, film had not yet developed its own consumer market. Therefore, films were screened in entertainment venues along with other recreational activities. Film did not attract much attention from the media, and was popularized by word of mouth. Initially, the exhibitors adopted tour-style screening to get close to their target audiences, and slowly increased the popularity of films. At first, audiences for films were mainly composed of foreigners and some wealthy Chinese who had already experienced Western culture. So after the emergence of the dedicated cinema, the exhibitors usually selected a location with a high density of foreigners. This demonstrated that an important criterion of the cinema distribution was proximity to the public. Supplying the goods in a central place where the consumers would go furthered the development of the centre or market. This can explain why Hongkew District, north of Suzhou Creek gradually developed into a film screening centre.Footnote 85

With urban growth and the continuous development of public transport, the commercial areas were separated from the residential areas, and people's living space expanded gradually. The development of cinema depended not only on the population distribution, especially in the Central District, but also on people's demand for movies. This demand was determined by people's profession, income, wealth and social hierarchy. The local authorities’ planning and control of the city, together with the capital power (such as the economic development after the establishment of the settlements) and the non-capital factors (political and social events, such as the Sino-Japanese War) played an important role too. Western material civilization as displayed in the public roads built by the Western powers and the public transportation operated by Westerners was gradually accepted by the Shanghainese. The movies became more and more popular. Watching movies became a trend and one of the most popular daily entertainments. The cinemas ‘not only served as public markers in the geographical sense, but also were the concrete manifestations of Western material civilization in which was embedded the checkered history of almost a century of Sino-Western contact’.Footnote 86 The audiences draw on the foreign films, and accommodated themselves to Western modernity, both materially and spiritually. As Ou-fan Lee noted: ‘cinema was both a popular institution and a new visual medium which, together with journals, books, and other kinds of print culture, constituted this special cultural matrix in Shanghai’.Footnote 87

Different degrees of cinema targeted different audience groups; there was the Cathay Theatre for foreign guests, the Paris Theatre for Russians, the Rialto Theatre and the Golden Gate Cinema for college and middle school students, the Strand Theatre and the Lyric Theatre for female students and dancing girls.Footnote 88 Different theatres promoted different social etiquette and behavioural habits that were perceived as part of a new cultural identity, enabled by the diffusion of film culture. Bruno noted that in these public buildings, film reception was related once more to the perception and reception of arcades and their cafés, to railway terminals and trains arriving, to the department store and other urban public sites of modernity.Footnote 89 In different levels of cinemas in different regions in Shanghai, people from different classes gathered, experienced modern life in similar ways and generated different cultural atmospheres to influence the urban culture in return. We can see the significant urban cultural differences between the settlements and the Chinese-administrated areas. Can we then infer that the audiences in first-run or second-run theatres felt the same way as audiences in third- or subsequent-run cinemas, even when they watched the same films? This is worthy of further discussion.