When we started in England, engineers had no concept of how to record something like this, so you were fighting almost everything: the technology for what it was (really low believe me) … But there’s always been a certain fascination, especially for Mick and myself, about recording. How do you get what sounds great in the front room or in the bathroom or in the bedroom, how to make it sound like that in the studio and how do you capture it? I mean, recording is a tricky business …1

Traditional analyses of music often overlook sonic elements that are difficult to notate. This is especially true of the way many fundamental aspects of sound, such as timbre, resonance, ambience, stereo placement, and countless other sonic qualities are manipulated during the recording process, but largely ignored in popular music criticism. Yet these elements, so central to recordings of popular music, are as important in conveying expression and meaning as melody, harmony, rhythm, and lyrics. They are an integral part of the music – primary colors in the recording artist’s sonic palette.2

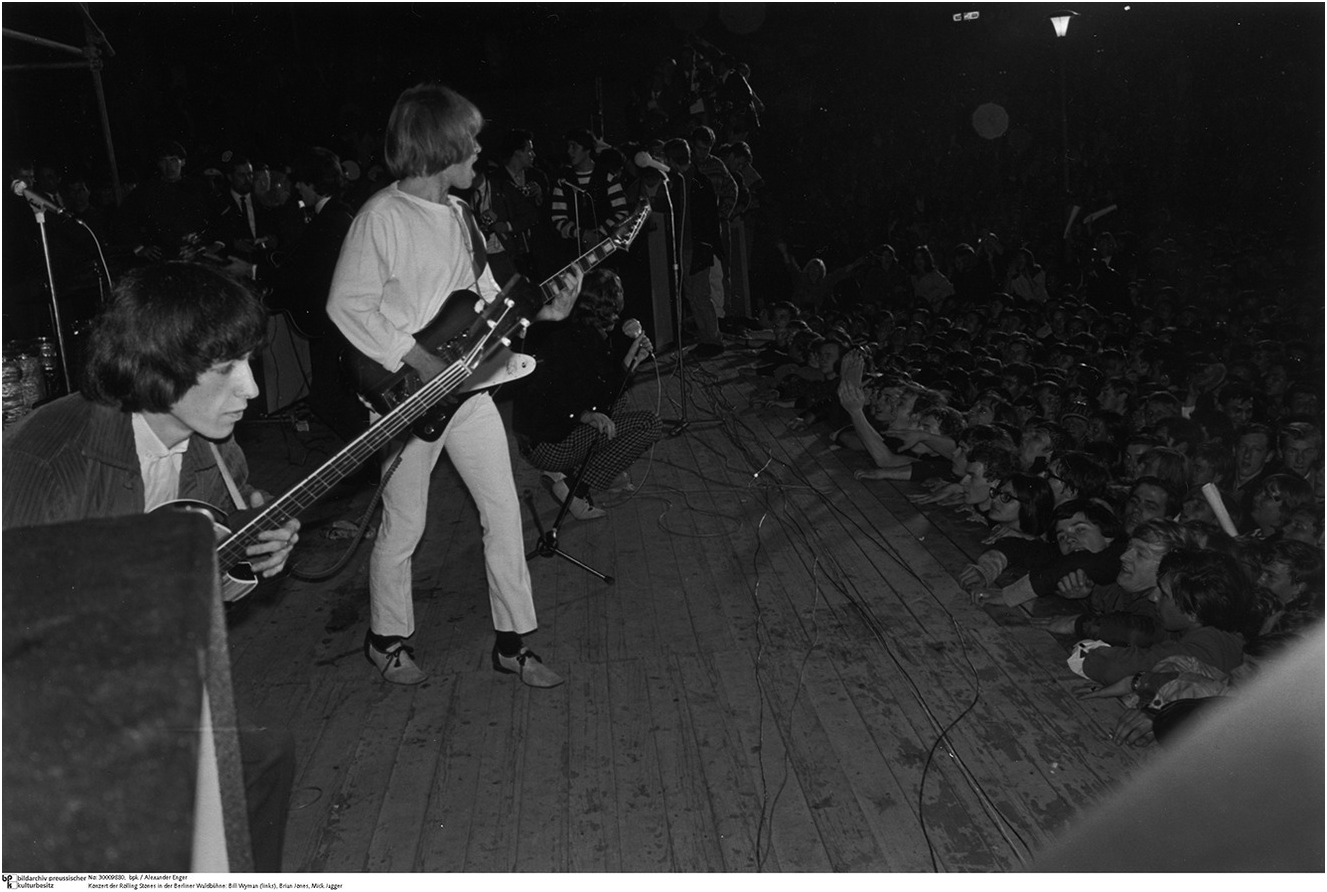

The extremely close attention paid to the sound of their musical production, both live and in the studio, is a primary reason for the enormous longevity of the Rolling Stones, now spanning well over half a century. Listening to them is like peering through the looking glass, observing how they balanced concurrent musical trends with their own fundamental roots in American blues, country, folk music, and rock and roll. As studio artists, the Stones have witnessed monumental changes in recording technology, with their own contributions in particular regarded as innovative and path breaking: One need look no further than the Stones mobile unit and its enormous legacy, the use of cassette tape recorders as “instruments” in songs like “Street Fighting Man” and “Parachute Woman,” and the melding of digital technologies with vintage recording methods on Blue and Lonesome (2016). If one constant could be found, it would be the sonic embodiment of an attitude that is immediately recognizable and undeniably Stones.

Blue Through and Through

We went for a Chicago blues sound, as close as we could get it – two guitars, bass and drums and a piano – and sat around and listened to every Chess record ever made. Chicago blues hit us between the eyes. We’d all grown up with everything else that everybody had grown up with, rock and roll, but we focused on that. And as long as we were all together, we could pretend to be black men. We soaked up the music, but it didn’t change the color of our skin.3

The British blues revival is often regarded as one of the most pivotal events in the history of popular music, and rightly so: it offered escape from the BBC’s tightly regimented program of lightweight pop; it served as a training school for eager young players and songwriters at a time when any kind of formal training outside of classical music didn’t exist; and it positioned its members as heirs apparent to a venerated lineage that was distant in both geography, race, and culture. As such, American blues was embraced as quintessentially authentic, an “early” music that existed outside of mainstream society and overtly capitalist interests in the same way that American blues musicians, their cultural heritage, and attitudes railed against conservative white society. Admittedly, the relationship between British blues bands and their African-American heroes has had more than its share of problems, its rich history often overshadowed by accusations of cultural appropriation and riddled by legal battles over copyright infringement, with many cases continuing today. In post-WWII London, however, a growing contingent of youth raised on rationing and the clearly defined social strata of an antiquated British class system could easily identify with the plight of African Americans. In retrospect, their unsettled love affair seemed predestined.

On September 2, 1964 the Rolling Stones, along with Andrew Loog Oldham, gathered at Regent Sound Studio to record “Off the Hook,” an early Jagger/Richards original, the Drifters’ “Under the Boardwalk,” and “Little Red Rooster,” which was inspired by Willie Dixon’s version of a traditional blues tune recorded by Howlin’ Wolf just three years earlier.4 A modest studio with humble facilities on Denmark Street (London’s equivalent of Tin Pan Alley), Regent typically catered to the production of demos and jingles. According to Richards, “it was just a little room full of egg boxes, and it had a Grundig tape recorder, and to make it look like a studio, the recorder was hung on the wall instead of put on a table … it made it easy for me to learn the bare bones of recording … One of the reasons we picked it was because it was mono, and what you hear is what you get.”5 Oldham recalled that it was “no larger than an average good-sized hotel room,” with the control room the size of the hotel’s bathroom, “but for us it was magic.”6 While the Stones had garnered considerable success over the past year with numerous performances at home and abroad, along with television appearances as well as recording sessions at legendary Chess Studios during their first US tour, they had yet to produce an LP or release any original music.7 Their insistent focus on blues and R&B covers (many of them B sides) is significant. Years later, Richards remembers the decision to cut “Little Red Rooster” as:

a daring move at the time, November 1964. We were getting no-no’s from the record company, management, everyone else. But we felt we were on the crest of a wave and we could push it. It was almost in defiance of pop. In our arrogance at the time, we wanted to make a statement. “I am the little red rooster/Too lazy to crow for day.” See if you can get that to the top of the charts, motherfucker.8

“Little Red Rooster” begins with a standard blues riff performed by Brian Jones on slide guitar with Bill Wyman delivering a more than credible simulation of Willie Dixon’s upright bass on his Framus Star electric. Richards doubles the riff on his single cutaway Framus Jumbo acoustic, replacing the piano and second electric guitar of Wolf’s recording while hearkening back to the Delta blues of Bukka White, Lead Belly, and the band’s recent discovery of the recordings of Robert Johnson.9 Watts, sitting far enough forward in the mix to suggest a club performance, gently applies brushes to his Ludwig kit, avoiding full snare in favor of rimshots, the bounce of his kick drum seemingly casual but tight. When Jagger enters at the first chord change of this subtly altered twelve-bar blues progression, the mild distortion that colors the edges of his voice conjures shades of the natural grit of Howlin’ Wolf’s earthy timbre. The vocal delivery and its spare accompaniment are restrained, punctuated by the occasional barnyard outburst of Jones’ slide guitar; the sparse texture, exaggerated by studio reverb, offers a perfect analog to the austerity of post-World War II Britain.

Despite the monaural mix, the performance is remarkably spacious, strangely resonant, atmospheric, and bleak, the generous use of reverb particularly arresting. As a sonic resource, reverberation is an especially powerful tool: it enhances and enlarges the signal it is applied to; it transports the listener into an imaginary performance space; and it can suggest boundaries – both physical and temporal – between performer and listener. Its presence is at least as old as rock and roll, and indispensable in communicating the power of its possessor. When describing the innovative use of slap-back echo and heavy reverb in 1950s recordings of Elvis at Sun Records and RCA Studios, Richard Middleton points out: “Elvis Presley’s early records, with their novel use of echo, may have represented a watershed in the abandoning of attempts to reproduce live performance in favor of a specifically studio sound; but the effect is used largely to intensify an old pop characteristic – ‘star presence’: Elvis becomes ‘larger than life’.”10

Mimed television performances of “Little Red Rooster” become particularly interesting in this context, where the auditory cues provided by Jagger’s reverb-soaked voice are completely at odds with the visuals of the performance: The singer and his band appear unaffected by the physical laws of reality.11 Sexually charged, mysterious, and detached from the mundane, the Stones are cast in an image of power in the same way that their idols used the blues as an expression of personal and cultural empowerment.

Black and White

[Jagger:] Andrew wanted to make the Rolling Stones the anti-Beatles, so if you’ve got heroes you’ve got an anti-hero, like in a movie, you’ve got good guys and bad guys. Andrew decided that the Rolling Stones were the bad guys … It helps to have people that go along with it or fit the bill; it’s good to have an actor who will play the part …

[Richards:] The Beatles got the white hat, you know. What’s left? The black hat.12

By 1966, popular music’s sonic landscape was rapidly changing, a transformation expedited by technological advances in the production, mediation, and reception of recorded music and encouraged by the ever-expanding psychedelic movement born of the London underground scene and its American counterpart, San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district. The increasing popularity of hi-fi stereo systems, the relatively new phenomenon of immersive personal listening enabled by John Koss’ invention of the stereo headphone a scant eight years earlier, and cutting-edge trends in the stereo transmission of popular music via FM radio in the United States dramatically altered the ways in which listeners engaged with recordings.13 Their significance notwithstanding, none of these industrial advances matched the cultural impact of The Psychedelic Experience, Timothy Leary’s hallucinogenic-assisted tour of the Tibetan Book of the Dead that became the manifesto of the counterculture. For pop musicians in the latter part of the sixties, it provided an impetus for unprecedented experimentation.

Recorded at RCA Studios in Los Angeles in early December of 1965 and early March of 1966, Aftermath marked a critical turning point for the Stones.14 Jagger described Aftermath as a landmark album, noting its eclecticism, sound quality, originality, and deliberate departure from blues covers:

It’s the first time we wrote the whole record and finally laid to rest the ghost of having to do these very nice and interesting, no doubt, but still cover versions of old R&B songs – which we didn’t really feel we were doing justice, to be perfectly honest, particularly because we didn’t have the maturity. Plus, everyone was doing it. [Aftermath] has a very wide spectrum of music styles: “Paint It, Black” was this kind of Turkish song; and there were also very bluesy things like “Goin’ Home”; and I remember some sort of ballads on there. It had a lot of good songs, it had a lot of different styles, and it was very well recorded. So it was, to my mind, a real marker.15

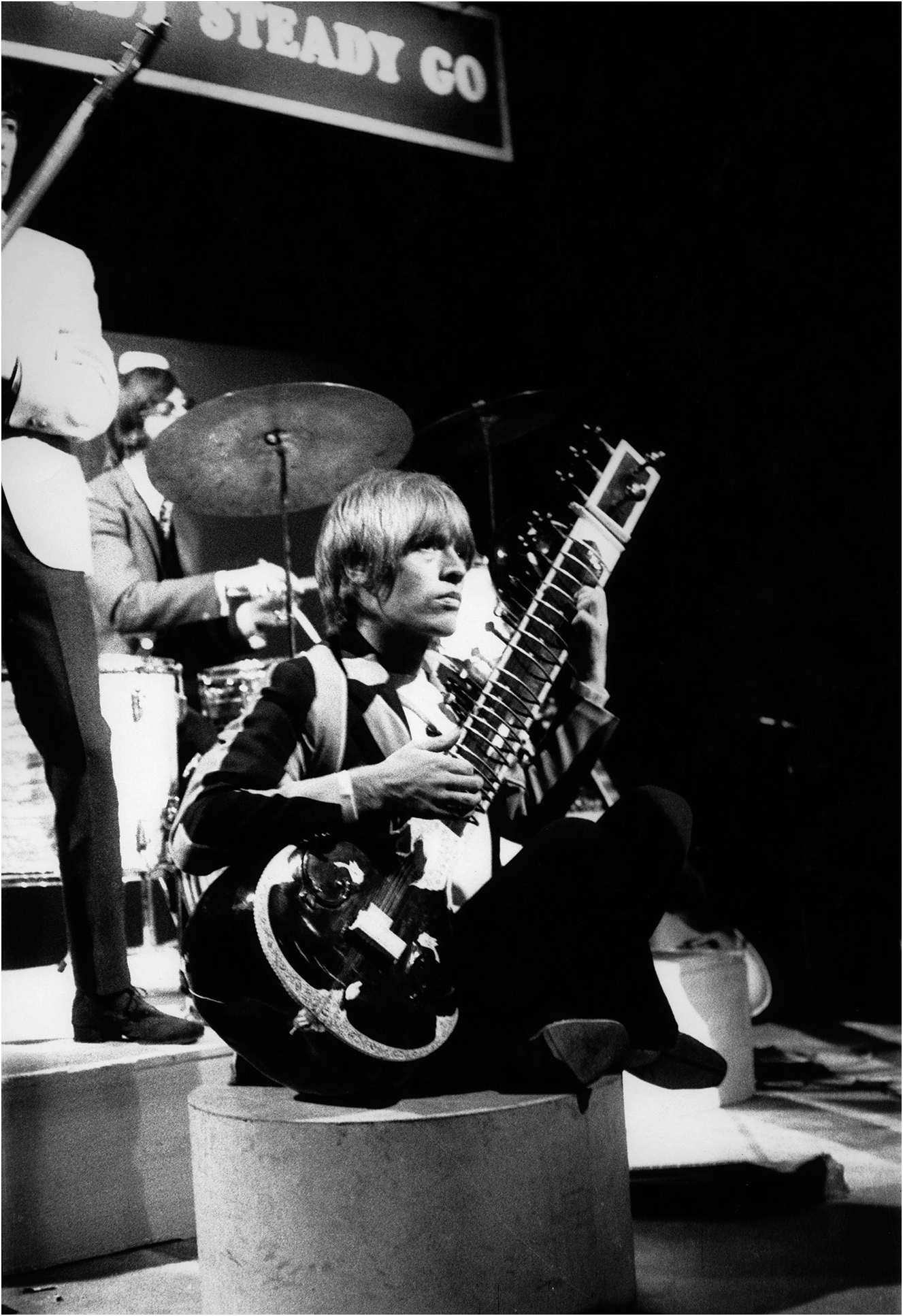

Brian Jones had become increasingly interested in instruments other than the guitar and blues harp, performing dulcimer on “Lady Jane,” marimba on “Under My Thumb,” and sitar on “Paint It, Black,” the latter released in the UK as a mono single in May, 1966 and as the opening track for the US release of Aftermath later that year in stereo. The acquisition of his first sitar likely occurred within a few days of the release on December 3, 1965 of the Beatles’ Rubber Soul, which contained George Harrison’s ground-breaking sitar-playing on “Norwegian Wood.” After initial experiments, Jones took lessons with a half-Welsh, half-Indian friend named Hari who had studied with Ravi Shankar for twelve years and was called in to coach Jones for the recording of “Paint It, Black.”16

The intentional shift away from the blues towards an eclectic style clearly illustrates the more cultural and historical inclusivity of pop music during the latter 1960s. The Stones’ songs now evoked images as diverse as Victorian England in “Lady Jane” to eastern pilgrimages along the hippie highway in “Paint It, Black,” at once demonstrating the band’s musical authority and versatility, while announcing their willingness to push forward and take stylistic risks rather than play it safe. The group’s predilection towards eclecticism takes on even greater significance when considering composer Luciano Berio’s observation that, “when instruments like the trumpet, the harpsichord, the string quartet, the recorder are used with electric guitars (or in place of them) … they seem to assume the estranged character of quotations of themselves … [and] develop into a sort of sound drama … in the form of a collage.”17 The end result of this interplay of styles and influences is the creation of a complex network of associations contained within the fabric of these songs. Building on Berio’s notion of “sound drama,” the song becomes the stage upon which a multiplicity of diverse musical characters interact, each one clothed in an immediately recognizable social/cultural/historical costume.

“Paint It, Black” certainly opens in dramatic fashion, the first iteration of its exotic minor melody heavily reverberant and in stark isolation, rhythmically unencumbered and panned far right in the stereo field. The calm, meditative pretense of its brief introduction is immediately shattered by Watts’ bellicose entrance on his four-piece Ludwig drum kit, the tom-toms cast as stand-in tablas panned far left. The full complement of players enters quickly, gathered around opposite sides of the soundstage: The sitar, overdubbed Gibson Hummingbird acoustic guitars played by Richards and Jones, as well as Richards’ performance on his Guild Freshman M-65 electric guitar, inhabit the right side of the stage; Wyman’s performance on his Vox Wyman bass along with doubling on the organ pedals of a Hammond B-3, added for weight, join Jack Nitzsche’s piano and Watts’ drums on the left;18 Jagger is the last to enter, the anti-hero in what quickly reveals itself to be an angry, menacing narrative, center stage amidst the propulsive syncopation of the instruments.

The timbre and ambience of the voice are essential elements of the ensuing drama, and clear indicators of the protagonist’s inner conflict; the abrupt changes between Jagger’s relaxed, sombre lower register and his choked, aggressive upper range that demarcate each half of the first four verses highlight his turmoil. The use of reverb, applied globally over the mix, adds an additional layer of meaning and invites several potential readings. Serge Lacasse points to the use of reverb in early French radio broadcasts and later, in the films of Alfred Hitchcock, as aural indicators of a perspective taken from within the character’s mind. Drawing on the observations of French cinema and radio theorist Étienne Fuzellier, he states, “the advent of electrical vocal staging [via reverb] … allowed [for the representation of] a psychological action directly from the interior, literally eavesdropping on a character’s mind, or to create parallel worlds …”19 Here, the presence of reverb, heavy in the first half and light in the second half of each verse, highlights Jagger’s torn emotional state and implies a continually shifting discourse. This effect is amplified by the width of the voice in the mix. For example, during the opening “I see a red door and I want it painted black,” the spectrum of Jagger’s voice is incredibly wide, covering the area roughly between 40 degrees (left) and 140 degrees (right) of the 180-degree stereo field. Conversely, during the second half of the verse beginning “I see the girls walk by dressed in their summer clothes,” the sitar disappears and the stereo width of the voice suddenly collapses, suggesting the juxtaposition of internal monologue and external declamation.

Lacasse also explores pre-electronic vocal staging in past cultures and non-Western traditions, noting its universal association with ritual and spectacle, and that the diffuse quality of such resonant sounds creates the illusion of sound coming simultaneously from everywhere and nowhere, suggesting power and mystery.20 If such is the case, then any aspirations toward transcendence evoked by the ambient quality of the mix and the allusion to non-Western music/spirituality are especially ironic. Superficially, many of the song’s musical attributes might parallel the music of the Beatles and their contemporaries; but for a counterculture that looked eastward for spiritual enlightenment and an alternative to their normative Judeo-Christian upbringing, the stark juxtaposition of “Paint It, Black”’s bleak narrative with sonic links to hippie idealism borders on satire.

As “anti-Beatles,” the Stones actively cultivated their image as outsiders, a contrarianism that was particularly glaring at the height of 1960s bohemianism. The nihilistic tone of “Paint It, Black,” or later works like “Midnight Rambler,” “Stray Cat Blues,” and “Sympathy for the Devil,” embraces themes far removed from the majority of their contemporaries while remaining central to those of the satirist: madness, violence, and apocalyptic chaos. As true satirists, the Stones enacted and performed madness through their recordings and live shows. Their representations of excess – violence, obsession, addiction, and sexual glut – shone a spotlight upon the ills of society.21

After Their Satanic Majesties Request (1967), their first album without Andrew Loog Oldham, the Stones – at the recommendation of engineer Glyn Johns – began their enormously successful (and as it turned out, regrettably short) partnership with Jimmy Miller, the American producer brought to England by Chris Blackwell to work with the Spencer Davis Group. Miller’s five-year tenure with the Stones, beginning with Beggars Banquet (1968), marked what is often regarded as their finest work.22 The album’s opening song, “Sympathy for the Devil,” left no doubt – if there ever was any – as to the color of hat the Stones wore.

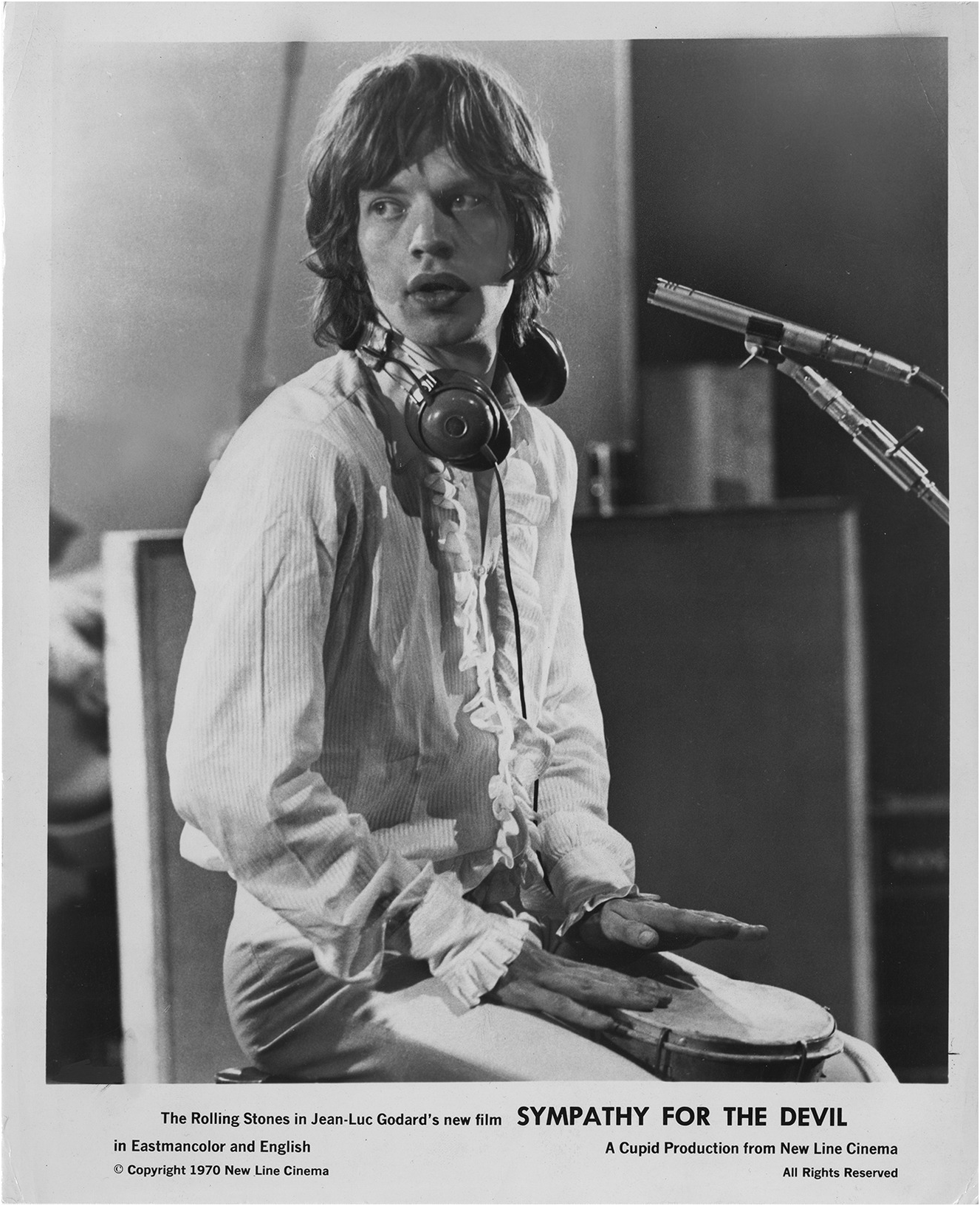

Recorded at Olympic Studios’ relatively new home on Church Road in Barnes, the two-day evolution of “Sympathy for the Devil” from its folky, Dylanesque beginning as brought into the session by Jagger into its densely textured, frenetic samba, serves as the musical centrepiece to Jean-Luc Godard’s film One Plus One. Later retitled Sympathy for the Devil, against the director’s wishes, the film documents the song’s gradual transformation interspersed with scenes depicting contemporaneous revolutionary ideology (see Figure 6.1). Although band members remain grateful for its existence, their responses to the film as a whole are at best ambivalent: “Nobody, I think, has ever quite honestly been able to figure out what the hell he was aiming at … I’m glad he filmed that but Godard! … The film was a total load of crap …”23 Issues of intelligibility aside, One Plus One offers valuable insights into the band’s characteristically free approach to recording in which seminal ideas are allowed to develop in an organic and largely spontaneous process.

Olympic Studios is synonymous with British pop, its roster of employees and list of clients representing the most famous names in the industry. Originally located on Carlton Street near Piccadilly, it served as the location of the Stones’ first hit recording in 1963 of Chuck Berry’s “Come On.”24 In 1966 an expiring lease forced Olympic to move, settling eventually on a former television studio in the Barnes area of Richmond. A once derelict building, massive renovations for the studio included the construction of walls with no parallel surfaces in Studio One, and the design of Studio Two as a completely floating box, suspended by rubber pads on seventeen tons of steel framework.25 Revolutionary, ergonomic wrap-around mixing consoles for both rooms were conceived by studio manager and chief engineer Keith Grant, and were hand built by chief technician Dick Swettenham.26 They featured Lustraphone transformers and germanium transistors, the resulting third-order harmonic distortion a vital component to the Olympic sound. Clearly, the Stones found the venue more than acceptable: From 1966 to 1972 they recorded the better part of six albums there. In 1969, Jagger was even recruited as interior designer and decorator for Studio Two.27

“Sympathy for the Devil” is an absorbing passage through an evolving soundscape, where the music’s gradual thickening texture, its slowly increasing volume and pitch, and its increasingly harsh timbre coincide with the narrative’s path from prehistory to modernity. According to Jagger, the main character in “Sympathy for the Devil” is:

a very long historical figure – the figures of evil and figures of good – so it is a tremendously long trail he’s made as personified in this piece … It has a very hypnotic groove, a samba, which has tremendous hypnotic power … it’s also got some other suggestions in it, an undercurrent of being primitive – because it is a primitive African, South American, Afro-whatever-you-call-that rhythm. So to white people, it has a very sinister thing about it. But forgetting the cultural colors, it is a very good vehicle for producing a powerful piece.28

The introduction of “Sympathy for the Devil” opens on a primeval scene with Watts performing tablas on the far left of the stereo field, then joined by percussionist Rocky “Dijon” Dzidzomu playing congas on the far right. Jagger’s voice enters, a distant animalistic yowl panned slightly left that echoes into the far right. The setting is expansive, mysterious, even frightening. The successive layering of maracas, soft laughter, and grunts and groans positioned at various points across the soundscape quickly surround the listener, setting the stage for the following encounter and effectively foreshadowing the piece’s overall shape in miniature. The entrance of the anti-hero is startlingly abrupt, his voice dead center at the front of the mix, the complete lack of ambience suggesting an uncomfortable closeness: The devil is crooning in your ear, with carefully elongated sibilants of his prefatory, “Please allow me to introduce myself, I’m a man of wealth and taste,” unsettlingly serpentine. Flanked by Richards on bass guitar panned near-left and Nicky Hopkins on piano near-right, his importance is reinforced by their long, held chords in an ironic evocation of gospel music.29

In the ensuing discourse, various musical elements accompany the character’s relentless passage through human history. At references to the Crucifixion during verse one, the bass (played by Richards) adopts the dance rhythms of the percussion ensemble. Far right, the brief chatter of the backing singers that frames the first statement of the song’s chorus signals their growing restlessness. In verse two the story moves forward through the bloodshed of the last Russian czar and the stench of mechanized Blitzkrieg, where the piano also becomes rhythmically infected by the samba’s irresistible allure, intensified by Watts’ cymbal splashes on the downbeat. In the following verse, we are drawn into the present by the carnivalesque “oo-oohs” of the now unconfined backing singers, co-celebrants in humanity’s shared guilt at the demise of the Kennedys. Appropriately, the next musical figure to enter the soundstage is Richards’ overdubbed electric guitar just past the midway point of the song, the first incontrovertibly modern sound to appear. Playing on his Les Paul through a highly overdriven Vox AC-30 tube amplifier, his center-panned guitar is distorted and abrasive, perfectly matching Jagger’s timbre and momentarily becoming the Devil’s voice as Jagger reverts to sporadic grunts and vocalizations further back in the mix. Not surprisingly, the riffs are unmistakeably blues based.

Jagger’s vocal trajectory matches that of the instrumental texture, gradually moving from low to high and from clear to rough. In verse one, the melody occupies a fairly narrow range situated closely around b. During the first chorus, the rising melodic line is centered around d♯ʹ, at times reaching eʹ. In the first half of the second verse, Jagger’s vocal grows increasingly forced, insistent, and agitated; at “I rode a tank at the general’s rank” the vocal suddenly jumps to eʹ, becoming mildly distorted and growly, and in the following chorus the range is higher yet, circling around f♯ʹ and getting as high as g♯ʹ before returning to eʹ. The melody of verse four begins where it was left on eʹ, but now with many blue notes reaching gʹ, and during the third chorus Jagger’s vocal is distorted further with even more time spent around g♯ʹ. Here the guitar solo begins, its first two licks ending on the same note where the vocals left off, then gradually climbing to settle a full octave higher. The following, final chorus is punctuated by Jagger’s frequent deployment of gʹ blue notes, conspicuously placed on strong beats or at the beginning of phrases, his ever-growing excitement signalled by an increasingly strained vocal timbre. The closing jam session over the final 1:46 of the song sees Jagger’s falsetto extend a full octave higher, sometimes screaming, bordering on caricature in a blues-like call and response with Richards’ guitar. As the music gradually fades, the vocal returns to its primal state, echoing from near-left to far-right, apparently unaffected by the passage of time and leaving the listener to wonder if the dance will ever end.

Streets Running Red

I don’t think they understand what we’re trying to do … or what Mick’s talking about, like on “Street Fighting Man.” We’re not saying we want to be in the streets, but we’re a rock and roll band, just the reverse. Those kids at the press conferences want us to do their thing, not ours. Politics is what we were trying to get away from in the first place.30

Although some may disagree, until their inevitable transition from angry young men of the 1960s into respected post-1980s rock royalty, the Rolling Stones epitomized rock’s subversive, rebellious image – and in many ways, they still do. While it’s true they rarely engaged in overt political activities as visibly as John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Montreal “bed-in,” one can’t overlook Jagger’s arrest for participating in the 1968 anti-Vietnam protest march on the US embassy in Grosvenor Square, whose violent culmination helped inspire “Street Fighting Man.”31 Jagger later sent the song’s handwritten lyrics to New Left leader Tariq Ali, who published them in the November 1968 issue of the radical Black Dwarf newspaper. Ali and many of his brothers-in-arms felt the song’s message was perfectly clear: “Well, I thought they [the lyrics] were very ultra-left actually, when we heard the song and tried to sing it we thought, ‘God, it’s a bit far out even for us.’ But it reflected the mood. This is a sleepy town, why aren’t we doing anything!”32 Later, Jagger attributed “Street Fighting Man” to the political turmoil at home and the violent upheavals in France that resulted in the near collapse of DeGaulle’s government.33

“Street Fighting Man” opens the second side of Beggars Banquet and balances side one’s opening “Sympathy for the Devil,” the exposed positioning of both songs made all the more conspicuous on an album composed almost entirely of rural Americana. In March of 1968 the Stones, together with producer Jimmy Miller and engineer Eddie Kramer, began pre-production for the album at RG Studios in Morden where several demos were produced, including “Primo Grande,” which became “Did Everybody Pay Their Dues” and ultimately evolved into “Street Fighting Man.”34 Sessions at Olympic Studios commenced in March and lasted until June 10.35

By now, Richards was in a process of reinventing his playing style, adopting an open D-tuning (a standard open E-tuning lowered to D) following the example of blues players from the 1920s and 1930s. In addition to playing a Fender Precision bass for the song, Richards layered as many as eight acoustic guitar parts, a Gibson Hummingbird tuned variably in open D, in standard tuning, and in open five-string G-tuning using a capo in various positions. “There’s lots of guitars you don’t even hear. They’re just shadowing.”36 Other instrumental overdubs included Watts’ Ludwig kit, Jones on sitar and tambura, Nicky Hopkins on piano, and Dave Mason on shenhai, an Indian double-reed instrument brought in by Jones.

The main instrumental bed was recorded with the group huddled around a Phillips EL3302 portable recorder and its stock dynamic microphone owned by Richards, an early model cassette recorder that had no built-in limiter to prevent distortion. The idea came from Richards, who used the machine to record rough drafts of the band in his home and thought it was a shame they couldn’t get the same sound for the finished song. Jimmy Miller suggested transferring the cassette to 4-track. The session saw Richards and Jones playing acoustic guitars, positioned behind Watts playing a portable, suitcase practice kit with Jagger on maracas. This was then piped through studio monitors to an Ampex 4-track tape machine and then transferred to 8-track tape.37

It’s no wonder that “Street Fighting Man” caught the interest of Tariq Ali’s New Left. If visions of charging feet, fighting, and revolution set to a driving, hard-rock march weren’t enough to capture listeners’ attention, then the song’s powerful, rebellious sound surely would have. Aural representations of power abound, starting with Richards’ introductory cassette-recorded guitar riff, the heavy distortion of saturated tape completely subverting conventional hi-fi aesthetics and rendering its otherwise acoustic earthiness harsh, technological, and urban. Panned far-right, it begins in solitary isolation but is joined after two bars by Watts’ heavy tom-tom shots on the left. The two are soon augmented by hi-hats and a second, clean acoustic guitar on the left, Watts playing his cassette-recorded suitcase kit along with Jagger’s maracas panned right, followed by the driving ostinato of Richards’ overdubbed bass in the middle.

Jagger’s voice joins the fray, its heavily syncopated rhythm avoiding resolution until the final word of the line, “boy,” in a melodic setting clearly evoking the sound of a police siren. His track is doubled and the twin Jaggers are panned on opposite sides of the stereo field, lending additional weight to the text and suggesting strength in numbers. Upon reaching the chorus, the ranks swell further with more acoustic guitar “shadowing,” additional percussion, and the drone of Jones’ sitar highlighting the song’s hook and reinforcing its countercultural ties. This is further strengthened during the outro with the appearance of Dave Mason’s droning shenhai, surprisingly placed within the structure in a spot conventionally accorded to the guitar solo. As the principal musical forces begin to fade, Nicky Hopkins’ piano moves slowly forward in the mix performing a triplet pattern set in rhythmic opposition to the main beat and contradicting the harmonic stasis of the music. Has the fighting just begun?

Rock music has provided auditory symbols of rebellion, subversion, and empowerment for its participants since the beginning; this is nowhere more evident than in songs like “Street Fighting Man” and “Gimme Shelter,” the opening track to Beggars Banquet’s follow-up album, Let It Bleed. Of the many elements used to convey these symbols, distortion is one of the most essential. In his seminal book Running with the Devil, Robert Walser discussed its importance at length, noting its tendency to enlarge and empower the audio signal to which it is applied. Further, its subversion of hi-fi norms is an overt act of transgression and helps reinforce the music’s rebellious attitude. Finally, the sound of overdriven electronics is analogous to the sound of the overdriven, distorted cries of vocal screams and assists in communicating extreme agitation or uncontained, irrepressible emotion.38

In February of 1969, the Stones reconvened at Olympic for a series of sessions that would ultimately produce the bulk of Let It Bleed. Brian Jones’ continual deterioration and eventual dismissal from the band meant that Richards carried the bulk of the guitar duties for the majority of the songs on the album (in truth, this had already been the case for some time) until Mick Taylor was brought in as Jones’ replacement late in May. Jagger also played guitar on several tracks.39

Jagger remembered the period around the recording of Beggars Banquet and Let It Bleed as a tumultuous one:

Well, it’s a very rough, very violent era. The Vietnam War. Violence on the screens, pillage and burning. And Vietnam was not war we knew in the conventional sense … It was a real nasty war, and people didn’t like it. People objected, and people didn’t want to fight it. The people that were there weren’t doing well. There were these things that were always used before, but no one knew about them – like napalm … That’s [i.e. “Gimme Shelter”] a kind of end-of-the-world song, really. It’s apocalypse; the whole record’s like that.40

The bed tracks for “Gimme Shelter” were among the last completed for the album. Richards played an Australian-made slimline hollow-body electric Maton SE777 through a Triumph Silicon 100 amplifier whose built-in tremolo forms an integral part of the track’s sound. The guitar literally fell apart just as the last chords of the final take were struck, coming to its own apocalyptic end. Additional musicians included Nicky Hopkins on keyboards and Jimmy Miller on tambourine.41 Singer Merry Clayton was called in as a replacement for Bonnie Bramlett, originally slated for the job. According to engineer Glyn Johns, Clayton was late-term pregnant, unimpressed at being summoned from bed by a group she had never heard of, and only acquiesced to come to the late-night session to satisfy the pleas of her husband. Johns recounted, “none of us had ever heard anything quite like what she produced that night. I practically had to stand her in another room, her voice was so powerful. She did three amazing takes, standing there with her hair still in curlers, and went home.”42

The sense of rising frustration and apocalyptic dread reflected in Jagger’s previous comment are apparent within the first few iterations of the song’s opening chord progression, initially performed on Richards’ solitary Maton electric and quickly joined by backing vocals, percussion, and Watts’ light accompaniment on kick, snare, and cymbals. Several additional guitars augment the gradually thickening texture, set against a single-note ostinato played on the bass immediately imitated on the lower keys of the piano. The general direction is one of descent, both in terms of the succession of instrumental registers and the downward C#–B–A of the chord progression. At around 0:40, two bullet shots on Watts’ snare shock the instrumental collective into a single, unified statement of the riff before settling in to a monochordal groove that serves as the verse’s bed. All of the instruments are placed unusually close to the center of the soundscape, with Richards’ pulsating guitar, fat and crunchy, occupying both sides of the stereo field simultaneously.43 A final blues lick on a center-panned electric guitar, prominently forward in the mix, marks the end of the introduction and announces the arrival of Jagger’s vocal.

Jagger enters nearly overwhelmed by the crowded instrumental texture; his melody occupies the same range as the proceeding guitar and his voice sounds similarly effected and compressed. Indeed, their sonic resemblance and ongoing exchange throughout the song identify them as co-narrators. The chorus is marked by Merry Clayton’s dramatic, emotionally charged entrance, soaring above Jagger’s warning: “Oh, children, it’s just a shot away, it’s just a shot away!” She is joined at around 2:00 by her own co-narrator, a blues harp whose severely distorted sound closely matches her intense vocal quality and emotional distress. During the song’s climax, Clayton reaches the threshold of her range and the limit of self-control: Her voice breaks repeatedly with her cries of, “Rape, murder, it’s just a shot away, it’s just a shot away!” to the relentless accompaniment of the riff.

The release of Let It Bleed on December 5, 1969 just a day before the tragedy of Altamont was sadly prophetic: The deteriorating events culminating in the death of Meredith Hunter are often seen as a turning point away from the optimism of the late 1960s to the pessimism of the following decade. The gradual hardening of the Stones’ sound over the course of their first decade runs parallel with the growing frustration of the counterculture. Despite wishes to remain politically ambivalent (or at least aloof) the Stones found themselves front and center of politics. As generational spokesmen, the Stones challenged existing institutions and helped forge a new identity for youth without the need to be overtly political, bringing leftist ideology squarely into the center of mainstream consciousness.44

Earth Tones

I firmly believe that if you want to be a guitar player, you better start on acoustic and then graduate to electric. Don’t think you’re going to be Townshend or Hendrix just because you can go wee wee wah wah.45

As hard-rocking as their sound and image often is, even the most casual listener could likely name a song or two by the Stones featuring acoustic instruments; it is an aspect of their sound as fundamental as their grounding in American folk, country, and Delta blues. For a counterculture emerging from the turmoil of the late 1960s and looking to the unfolding decade with growing mistrust, acoustic music hearkened nostalgically to the innocence of the movement’s early optimism and Dylan’s assertion that the times were a-changin’. A similar situation existed for British audiences still within earshot of the skiffle craze of the late 1950s and the Marxist leanings associated with their own folk revival in the 1960s.

By the early 1970s, however, the landscape of popular music was often dominated by technological sounds: overdriven electric guitars and basses, keyboards such as the Hammond B-3, the mellotron with its “canned” orchestral sounds, and the futuristic resonances of the synthesizer and studio processing that completely transformed the natural qualities of instruments and voices. For contemporaneous listeners, recourse to acoustic instruments and “natural” vocal performances signified a shedding of the trappings of technology in a romantic return to a simpler, more authentic experience.

The use of acoustic instruments and connotations of authenticity are completely embedded in music of the period. One need only look to Bob Dylan’s controversial performance on electric guitar at the 1965 Newport Jazz Festival, where the show was repeatedly interrupted by booing. The strong link between perceived authenticity and acoustic performances also extends to the British blues revival as experienced first-hand by Richards during a performance by Muddy Waters on electric guitar around 1961: “Muddy and the band were playing great. It was a knockout band … But for this audience, blues was only blues if somebody got up there in a pair of old blue dungarees and sang about how his old lady left him … What did electric have to do with it? … They wanted a frozen frame …”46

As unfortunate as some of these perceptions were, the integration of acoustic elements by the Stones and their contemporaries fulfilled several important functions: Like their connection with the blues, it linked the Stones with earlier musical traditions, positing them as informed scholars of popular music’s greater history; it also allowed them to demonstrate their versatility and true skill as players without the benefit of modern technology (Richards’ “wee wee wah wah”); finally, it offered enormous potential for experimentation and dramatic tension, especially when acoustic and electric instruments were deliberately set against each other on an album or within a song.

In “Sister Morphine,” the Stones used the acoustic/electric dialectic to great effect. An early version of the song was released as a 1969 single sung by Marianne Faithfull with Mick Jagger on acoustic guitar, Ry Cooder on electric guitar, Charlie Watts on drums, and Jack Nitzsche on piano. Work on a Stones version began early in 1969 during the Olympic sessions for Let It Bleed and was completed for release on Sticky Fingers (1971).47 The song begins in stark isolation, with Richards’ melancholic acoustic guitar accompanying Jagger’s soft vocal, “Here I lie in my hospital bed. Tell me, Sister Morphine, when are you coming ’round again?” The lack of ambience is disquieting, especially on an album where vocal enhancement via reverb, echo effects, console saturation, and augmentation by backing vocals is more evident. Here, the thin timbre and barren soundscape convey a sense of fragility and isolation unlike any other moment on the album.

As early as 1936, film theorist and perceptual psychologist Rudolph Arnheim described the impact of sounds recorded in deadened vs. resonant spaces, noting that sounds devoid of ambience imply that the recorded sound comes from the same space that the listener occupies, since it bears the same sonic footprint. Ambient sounds, on the other hand, create the sense of listening in on a foreign space.48 In “Sister Morphine,” the protagonist is located squarely within the listener’s ambient space, narrow and focused in the center of the stereo field. Devoid of studio enhancement, accompanied by a solitary acoustic guitar, he is organic, natural, and vulnerable.

The unfolding narrative reveals an accident victim’s return to consciousness, accompanied by fleeting images of his ordeal, his growing understanding of his predicament, and the unavoidability of his approaching death.49 Although Jagger has stated that the story is meant to be taken at face value, associations with drug addiction are surely viable, especially in light of the song’s auditory cues. The first figure to disturb Jagger’s space is Ry Cooder’s slide guitar on the far right; the generous use of reverb marks it as an outsider and its thick electric timbre throws the acoustic guitar’s woody naturalness in sharp relief while Jagger confides, “The scream of the ambulance is sounding in my ears.” As his voice rises in pitch and intensity, it also becomes lightly impacted by reverb, joined now by Wyman’s fretless bass encroaching on the left during the line, “What am I doing in this place?” The final word in the closing line of verse two is heavily soaked in reverb: “Can’t you see, Sister Morphine, I’m trying to score.” In the following verse, the instrumental texture is further thickened by the palpitating heartbeat of Watts’ bass drum, dry like Jagger’s vocal and sharing his placement in the center of the stereo field. This is suddenly followed by Nicky Hopkins’ angular piano flourishes: Significantly, the sound of the keyboard is so heavily treated with reverb as to render it almost unrecognizable and place it effectively behind the vocal. Watts’ pulse quickens as he engages more of his kit, his once dry, natural sound tainted by reverb and echo. The protagonist is caged in on all sides of the soundscape, his once natural acoustic presence slowly enclosed in sounds twisted by machinery. During the song’s long fade, his final shouts of “hey” become part of the ambient wash: Has the story teller shed his mortal coil or succumbed to his addiction?50

Blues at the Crossroads

The silence is your canvas, that’s your frame, that’s what you work on; don’t try and deafen it out.51

From their inception as green but passionate artists of a nascent 1960s British blues revival through to their most recent album Blue and Lonesome (2016), the Rolling Stones have been working on their canvas for well over half a century and show no signs of stopping. Convening at Mark Knopfler’s British Grove Studios in London, sessions for Blue and Lonesome marked the first time in over a decade that the band would begin work on a new album. According to Knopfler, the studio “is probably analog’s last great shout … But it also incorporates the best of the latest digital technology …”52 Knopfler’s long-time co-producer Chuck Ainlay described the facility as “a monument to past and future technology. The studio has an API Legacy in one of the rooms and a new 96-frame Neve 88R in the other room with a bunch of older Neve-style modules. There are also two old EMI consoles …”53 After several days in British Grove with little new material to show for it, Richards suggested a new tack:

I called Ronnie up a few weeks before the session, I say, “Get this blues track down, just because we might need it to get the sound in the room together …” After two days, it proved to be true that this room is fighting us, so I said, “Ronnie, ‘Blue and Lonesome’.” And after that, it all fell into place … This record just sort-of happened … it imposed itself.54

Over the course of five days, twelve tracks were recorded, and to their own surprise the Stones produced the first album comprised entirely of blues covers in their long history.

“Just Your Fool,” the raucous Buddy Johnson/Little Walter opener on Blue and Lonesome, perfectly encapsulates the Stones’ longstanding alignment with the blues. Within the first twelve bars, before Jagger has uttered a word, the band has told us everything we need to know about their roots: the harmonica, Jagger’s surrogate voice, moans and wails front and center amidst a soundscape bristling with energy, driven by Watts’ steadfast pulse, now as in the past always a calculated hair or two behind Richards’ lead. The electric guitar is distorted and crunchy as the bass throbs below, adding to the riff’s thickness and weight. Occasionally, distant snatches of honky-tonk piano evoke the ghost of Ian Stewart. Jagger’s voice enters with authority and swagger, its timbre as crunchy as the guitar, the distortion and heavy proximity effect signalling his insistence on being heard. The club-like ambience of the track envelopes the full collective of musicians and for a moment, against all we know to be true, we are transported to a small bar in Ealing or Richmond to reconnect with the past and reaffirm long-shared beliefs.

Just how long the Stones will be guiding listeners through the Crossroads remains an open question, but according to Richards there are no immediate plans to retire: “It’s what we do man – we enjoy doing it and there’s thousands of people out there and they enjoy it too. You can’t be a party pooper, right?!”55

Fashioning identity has always been at the heart of the Rolling Stones’ music and mystique. From their origins as white English teenagers delving as deeply into black American rhythm and blues as any band in Britain (or the States, for that matter) at the time, to their post-sixties forays into glam rock, reggae, disco, and other diversions, they rode into the twenty-first century as a self-defining “classic,” parlaying their status as one of the most accomplished and longest-lasting bands of the rock era into a self-sustaining mega act. Through it all, the initial connection to the blues remains the stylistic marker to which they are most often associated, an influence that has come full circle with their recent Grammy Award-winning album of blues covers, Blue and Lonesome of 2016. As they came to public attention, the overtly African-American implications of the blues provided the Stones with an edgy cultural distinction. To be sure, other British invaders built their sound on a foundation of blues artists from the 1930s through the early 1960s, but as the Stones rose to prominence among such acts, they were drawn into a binary relationship with the Beatles, whose style was more obviously eclectic and whose identity was driven by the commercial agenda of their manager Brian Epstein. This proved especially true in the States when each group arrived for tours in 1964. It is no surprise, for example, that when the Beatles had a few days off on their initial visit to the USA in February, 1964, they remained in Miami (where they made their second appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show) to take in nightclub acts at the Deauville Hotel or fishing and riding speed boats around Miami harbor, whereas the Stones took advantage of a five-day gap in their eight-city, cross-country tour to fly to Chicago to record new songs at Chess Studios – to them, a virtual R&B Valhalla. And while they jammed there with heroes like Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, and Ray Charles, the Beatles’ only close contact with a black cultural figure came in a light-hearted photo-op with Muhammad Ali (then Cassius Clay), who was in Miami training for a title fight.

Painting the Stones “black” and the Beatles “not black” is, of course, overly simplistic to the point of being misleading. The Beatles incorporated plenty of R&B (and more still, Tamla Motown) influences into their version of the “Merseybeat” sound. But like many other influences, it is a skillful amalgamation with a wide variety of musical styles, from pre-war Music Hall tunefulness and Sun Records rockabilly, to the Bakersfield twang of Buck Owens. The Bakersfield-influenced “I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party,” recorded and released in September of 1964, predates their overt nod to Owens with the cover of “Act Naturally” in 1965. By the same token, the Stones’ cultivation of the black roots styles dug up a host of musical idioms that are tangled up in the blues. Once one travels back beyond the post-war style shifts occasioned by the introduction of the electric guitar, it becomes harder to draw distinct lines between the rural blues and white folk styles. That admixture did not surface much in the Stones’ early albums, but Beggars Banquet in 1968 saw a turn towards acoustic instruments, in the aftermath of ever trippier tracks during the preceding year. Keith Richards remarked:

There was a lot of country and blues on Beggars Banquet: “No Expectations,” “Dear Doctor,” even “Jigsaw Puzzle.” “Parachute Woman,” “Prodigal Son,” “Stray Cat Blues,” “Factory Girl,” they’re all either blues or folk music … We had barely explored the stuff where we’d come from or that had turned us on. The “Dear Doctor”s and “Country Honk”s and “Love in Vain” were, in a way catch-up, things we had to do. The mixture of black and white American music had plenty of space to be explored.1

The blues half of this equation was quickly recognized as a reboot for the group, returning to their “roots.” But the same impulse also spawned a number of country tracks across Beggars Banquet and the succeeding albums through the 1970s, a group of songs that form a distinct subset in the Stones’ songbook.

The group’s early blues covers and originals grew consistently from the electrified R&B of the 1950s. But when the Stones turned to country, they presented a far more variegated picture of an American style that (rightly or wrongly) can be seen as separate from the black musical influence that was so bound up with their own musical identity up to this point. A number of factors led to the heterogeneity of the Stones’ country songs; but, more so than the relatively specific locales – Chicago, the Delta, Texas – that the blues represented to them, the diversity in their country output allows these songs to plot a road map representing the geographic sweep of America that the label “country music” covers. Moreover, while the return to the blues in 1968–72 was marked most strongly by the push back beyond the fifties R&B that had been the Stones’ earlier inspiration (covers of Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, Chuck Berry, Howlin’ Wolf, and others on earlier LPs were replaced by ones of Robert Johnson, Fred McDowell, and Robert Wilkins), their foray into country embraced similarly retro styles but also up-to-date country-rock syntheses, reflecting the wide range of the Stones’ country influences.

Country Learnin’

Preceding any outside influences, members of the band each brought their own familiarity with country music to the table. Jagger claimed that he and Keith Richards had listened to, written, and recorded country music long before Beggars Banquet:

As far as country music was concerned, we used to play country songs, but we’d never record them – or we recorded them but never released them. Keith and I had been playing Johnny Cash records and listening to the Everly Brothers – who were so country – since we were kids. I used to love country music even before I met Keith. I loved George Jones and really fast, shit-kicking country music, though I didn’t really like the maudlin songs too much.2

A penchant for country music would not make Jagger or Richards unique among sixties British rockers (the Beatles had been penning Bakersfield-influenced songs since 1964: “I’m a Loser,” “I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party”), but they had displayed only a little interest before Beggars Banquet. At least, not on any released material. On a trio of demo recordings from the summer of 1964, Stones manager Andrew Oldham enlisted a number of outside players (members of the “Oldham Orchestra”), including several guitarists who were already highly respected (Big Jim Sullivan) or destined to become major figures (Jimmy Page and John McLaughlin). Someone among them played pedal steel guitar to lend a country tinge to the songs.3 These tracks only surfaced a decade later on the UK LP Metamorphosis (only “Heart of Stone” appeared on the US release of the LP), but demonstrate an early curiosity about country sounds, at least on the part of Oldham: Mick Jagger may have been the only member of the band participating in one or more of these recordings. Of the songs in question (all Jaggers/Richards compositions), “Some Things Just Stick in Your Mind,” “We’re Wasting Time,” and “Heart of Stone,” only the latter was rerecorded and released a few months later as a single in the USA, with the pedal steel replaced by Keith Richards’ baritone guitar.

It would take a while for the group to air their country interests. A live cover of Hank Snow’s “Movin’ On” from late 1965 owes more to Ray Charles’ 1959 cover than to the original. Months later, on Aftermath, the Jagger/Richards song “High and Dry” does more to validate Jagger’s claims. As a country song it is a hodgepodge: Richards’ overdubbed acoustic guitars are as much a bow to folk music as country, while the relatively loose ensemble conjures an earlier era in country recordings. As in the more frequently referenced country songs in the Stones’ output (discussed below), neither Bill Wyman nor Charlie Watts display much affinity for country rhythms. The latter’s ringing hi-hat serves to avoid a rock back-beat, but fails to capture the terse simplicity of 1960s country drumming. “I love Hank Williams and Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline, but the whole Nashville thing I’m not that enamoured of,” Watts commented years later. “I can enjoy Buck Owens and Bob Wills’s swing band and George Jones, but it’s not something I’m particularly good at.”4 At the same time, Wyman’s repeated notes in “High and Dry” oversimplify the root-fifth alternation of a typical country bassline. Both members would grow and adapt in the country songs of the coming years, but the rhythm section helped to mark these numbers as Rolling Stones tunes, no matter how deeply Richards delved into the world of “Three Chords and Truth” (a phrase widely attributed to legendary Nashville songwriter Harlan Howard) or how often Jagger affected a Southern drawl.

On Aftermath, “High and Dry” is one of several forays into new styles for the group, including the quasi-Elizabethan “Lady Jane,” the artsy “I Am Waiting,” and a smattering across the album of a variety of instruments from outside the rock band line-up.5 It shows less an interest in exploring country music than in exploring various styles beyond the band’s core blues sound. That impulse to widen their stylistic horizons led to the nearly obligatory diversion into the Summer of Love, culminating in the least Stones-like Rolling Stones album of the decade, Their Satanic Majesties Request. Though some elements of psychedelia lingered beyond Majesties, 1968 marked the band’s decisive turn, as noted above, back to the blues on Beggars Banquet. By the time the album was released at the end of that year, two critical outside influences had redirected the Stones’ stance toward country music: Gram Parsons and Ry Cooder. Their impact on and interaction with the group could hardly be more different. In May, the group encountered Parsons while he was on tour in the UK during his brief stint with the Byrds (indeed, his initial conversations with Jagger and Richards about the band’s upcoming tour of Apartheid South Africa convinced Parsons to drop out of the Byrds).

Although Parsons’ influence was more personal and more widely acknowledged, Cooder’s contribution must be considered for an understanding of what “country” meant to the Stones in the 1970s. Cooder was brought over from the USA by Jack Nitzsche in June of 1968 to jam with the Stones, in order to percolate ideas for a film project (The Performers) back in Los Angeles, for which Cooder was to write the soundtrack. While his most notable impact on the group was turning Richards onto the five-string open-G tuning (with which Richards claims he was already experimenting), Cooder also deserves credit for helping to steer the band towards pre-Chicago blues, an era when white and black “country” music were often indistinguishable, when Lesley Riddle could collaborate with the Carter family and Woody Guthrie could sing alongside Lead Belly.6 A number of the Stones’ songs, from Beggars Banquet onward, tap this earthier, organic vein of country music: “Sweet Virginia” from Exile on Main Street, and “No Expectations” from Beggars Banquet, for example. Nowadays, we might not think to label those songs country, but the concept of “country rock” was broad enough at the end of the sixties to encompass the loose Americana aura of The Band (touted on the cover of Time Magazine as “The New Sound of Country Rock”), the straight-ahead honky-tonk of the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, and the tight-harmony and steel guitar-laden styles coming out of southern California from Poco, The New Riders of the Purple Sage, and others. By contrast, Cooder was himself a product of the late-sixties LA music culture, and his own albums around this time illustrate his interest in everything that scene had to offer, not just the emerging sound of hippie-twang. Through Nitzsche, a record company insider with his own eclectic tastes, Cooder was in contact with other roots-seekers in LA: Randy Newman, Leon Russell (who had already played on many recordings there as a member of the studio band, the Wrecking Crew), and Lowell George, to name a few.7 Some of that mix probably was conveyed to the Stones in London. Although they had little (documented) contact with those artists, echoes of all the aforementioned can be heard throughout their string of albums from 1968–72, and Russell actually first recorded the Stones’ gospel-influenced song “Shine a Light” a few years before it appeared on Exile, for his eponymous album of 1970.

Just how much of those influences were directly communicated through Cooder and how much was a matter of a shared musical language is hard to gauge. The relationship between him and the band soured a year later when he was once again brought in by Nitzsche, at the planning stages for the 1969 album Let It Bleed. Although he is credited on “Love in Vain” (mandolin) here, and later on “Sister Morphine” (slide guitar) from Sticky Fingers (1971), Cooder vented in a 1970 Rolling Stone interview about his presence during the Let It Bleed sessions, claiming that his riffs were copied by Richards and formed the core sound of the album:

The Rolling Stones brought me to England under false pretenses. They weren’t playing well and were just messing around the studio … When there’d be a lull in the so-called rehearsals, I’d start to play my guitar. Keith Richards would leave the room immediately and never return. I thought he didn’t like me! But, as I found out later, the tapes would keep rolling …

In the four or five weeks I was there, I must have played everything I know. They got it all down on these tapes. Everything.8

For their part, the Rolling Stones have downplayed Cooder’s influence, allowing only as how he showed Richards many ways to utilize the open G-tuning that became a hallmark of Richards’ playing from that point on.

By contrast, Gram Parsons is often assumed to have given the Stones as much material as Ry Cooder complained that they took from him. Yet unlike Cooder, Parsons never claimed any credit or begrudged the band any bits and pieces they might have borrowed. In part, this speaks to the deep personal connection he felt to the band, and to Richards in particular, who spoke of Parsons as a “long-lost brother.”9 On three stints – the first at Richards’ Redlands estate in the summer of 1968 following Parsons’ decision to abandon the Byrds in July; the second in the fall of 1969 when the Stones took up residence in southern California to complete Let It Bleed and prepare for a US Tour; and the third in the summer of 1971 at Richards’ Villa Nellcôte in the south of France, where the Stones were recording what would become Exile – Parsons and Richards bonded in lengthy explorations of the country canon, with Parsons bringing Richards’ youthful familiarity with honky-tonk up to date. His Southern bona fides notwithstanding, Parsons himself had only warmed to country music when he arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts to attend Harvard in the fall of 1965. During his single (mostly truant) semester there, he fell in with a band that would move to the Bronx within a year and become the International Submarine Band. ISB guitarist John Nuese takes credit for immersing Parsons, along with the rest of the band, in the Bakersfield sounds of Merle Haggard and Buck Owens: “Gram knew nothing about what was going on with country music in the sixties and he quickly became an avid fan … He took on that music and made it his own.”10 Neuse recounts long nights singing through material that jibe with Parsons’ later marathon singing sessions with Richards as the latter recalls them:11

[W]e played music without stopping. Sat around the piano or with guitars and went through the country songbook. Plus some blues and a few ideas on top. Gram taught me country music – how it worked, the difference between the Bakersfield style and the Nashville style. He played it all on piano – Merle Haggard, “Sing Me Back Home,” George Jones, Hank Williams … Some of the seeds he planted in the country music area are still with me, which is why I can record a duet with George Jones with no compunction at all.12

By the time Parsons met Richards, he had cajoled the International Submarine Band into moving to Los Angeles, where they disbanded in 1968, shortly before Parsons and Neuse scored a record deal with Lee Hazelwood and produced one album (Safe at Home) with a hastily assembled new line-up. Over the next five years of his short life (he died of a drug overdose in 1973 at the age of twenty-six), Parsons established a pattern of gathering other musicians around him, only to lose interest, focus, or both, or to try the patience of his collaborators through his unreliability, which was largely fueled by his substance abuse. His fame and influence (almost entirely posthumous) are wildly disproportionate to the amount of music he wrote and recorded, and speak more to his vision of “Cosmic American Music,” in which the various strands of late 1960s popular music – country, R&B, and rock – could be harmoniously blended. Parsons recognized this quality in the Stones as he encountered them in 1968. Prompted by an interviewer’s leading comment (“‘Wild Horses’ is very unlike most of their writing”), Parsons calls the song “a logical combination between our music and their music.” As Parsons tried to explain in his ensuing remarks, the Stones had sent the original masters to Parsons’ band, the Flying Burrito Brothers, who actually released the first version of the song.13 This remark touches on a subtle but critical facet of his relationship with the Rolling Stones and on the very nature of the Stones’ country songs. For all the hours Parsons and Richards spent drilling down into the country songbook, from Hank Williams to Merle Haggard, the idea of replicating the style of those songs and the sound of those recordings was not Parsons’ agenda during the years he was close to the Stones. Rather, he was after a synthesis of various strands of American music, and it is that vision that ultimately influenced Richards and his bandmates. That, however, leaves a more nebulous mark, which makes it hard to pin down Parsons’ impact, on the one hand, and easy to imagine it everywhere, on the other. Richards says as much: “That country influence came through in the Stones. You can hear it in ‘Dead Flowers,’ ‘Torn and Frayed,’ ‘Sweet Virginia,’ and ‘Wild Horses,’ which we gave to Gram to put on the Flying Burrito Brothers record Burrito Deluxe before we put it out ourselves.”14

The fact that those four songs come across as quite different from one another stylistically speaks volumes about the Stones’ approach to country stylings in their own music. Whereas their early focus on rock and roll and R&B provided some unity to their sound through 1966, the diversity of their country-influenced numbers reflects the wide range of their country inspirations and the relative novelty of the genre for the group. Moreover, since the country influence of Ry Cooder leaned more towards what we would nowadays label “roots” music, a mix of vernacular styles from which both country and the blues would emerge, and because Gram Parsons – for all of the Nashville and Bakersfield tutorials he shared with Richards – interacted with the group while pursuing his own path of blending country, blues, and rock under the banner of Cosmic American Music, it is not surprising that Stones Country is an itinerary of disparate places that don’t connect along one road; there is no country route to replace the Highway 61 of the Stones’ blues background.

What follows, then, is a tour of an imaginary musical landscape. Each of the songs discussed below has to be taken on its own merits, considered for its unique representation of country within the Rolling Stones’ core style. To help navigate them, however, I have grouped some songs together, leading from those older primordial mixtures of country and blues (The Old Country), through numbers that wear country on their sleeve – maybe a little too overtly (Deep Country), to songs that incorporate country elements in a decidedly modern manner to produce something entirely at home at the turn of the decade (Stones Country). This list hardly exhausts the songs that display country influence – much less the influence of Parsons and Cooder – but represents rather a survey of significant landmarks. Well-known examples (“Wild Horses,” “Country Honk,” “Torn and Frayed”) will be bypassed in order to focus on a handful of songs that raise particular issues of the Rolling Stones’ engagement with country music styles.

The Old Country: “No Expectations” and “Sweet Virginia”

One of the obstacles to defining Stones Country is the inherent blending of country and blues once one looks back beyond the honky-tonk era of Hank Williams and Ernest Tubb. Country music was only defined as a type in the wake of the “Big Bang” at Bristol in 1927, when Ralph Peer recorded Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family (along with numerous other aspiring regional acts) for the Victor Talking Machine Company in the first week of August. Although many white Appalachian string bands were recorded in the 1920s and early 1930s, their repertoire and playing styles often overlapped considerably with African-American blues artists (their counterparts in the “race” catalogues of Victor and other early recording companies). No one better illustrates the cross-fertilization between hillbilly music and the blues (and Tin Pan Alley, for that matter) than Rodgers himself, whose “Blue Yodel” series of songs all follow the twelve-bar blues form while borrowing vocal inflections and lyrical clichés from the black side of the “race records” divide.

At least two Stones songs from the cluster of albums between 1968 and 1972 dwell in that interstice. “No Expectations” from Beggars Banquet (1968) would seem to derive from straight blues material. Commentators frequently point to Reverend Gary Davis’ “Meet Me at the Station,” and Robert Johnson’s “Love in Vain” – which Richards claims the band had only discovered in 1967. “No Expectations” has the distinction of being the last recording to include Brian Jones, whose Hawaiian-style acoustic slide guitar quickly conjures the country blues of the 1930s. But if the lyrics vaguely tap various stock lines from early rural blues recordings (for example, “I followed her to the station,” from Johnson’s “Love in Vain,” becomes “Take me to the station” in the Stones’ hands), details in the musical setting decenter the song’s blues identity. Most notably, the verses alternate three times between a pair of chords (A major and E major), launching each iteration with a softly altered version of A major as Keith Richards lets a note from the other chord in the pair ring through in his part. Pre-war guitarists certainly may have added notes to these chords, but they would be flatted and would have added a bite, not the melancholy tone struck here. Jones’ limpid slide guitar lines do little to sharpen the effect. The result is neither blues, nor the rootsy early country of Jimmie Rodgers, Charlie Poole, and the like, but rather a comfortable blending of the two that pays homage to their interconnectedness, while injecting just enough poetry (“Our love was like the water/That splashes on a stone/Our love is like our music/It’s here, and then it’s gone”) to render the song modern. Like some other songs in Stones Country, the country element in “No Expectations” is mostly latent, as evidenced by the stronger presence of country idioms in covers that range from bluegrass renditions by John Hartford and Bill Keith, to outlaw statements from Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings, and a retro-roots version by Nancy Griffith and Son Volt.

“Sweet Virginia” (Exile on Main Street, 1972) similarly carries more country potential than it realizes (although in this case there is no bank of country covers to plead its case). The opening of the song seems as generically “country”-sounding as a song could get in 1972. Richards’ unadorned, jingle-jangle guitar could derive from any era in country music up to that time. But – as a country song – the track quickly loses its moorings. Although we could still hear “Sweet Virginia” as traditional country of one sort or another when Mick Jagger’s harmonica enters five bars in, followed in short order by Mick Taylor’s lead acoustic guitar, things start to take a right-angle turn when the drums and bass enter (0:47). A country vibe is maintained through the first verse but dissipates as the piano (Ian Stewart) and saxophone (Bobby Keys) enter with the chorus, and the entire ensemble morphs into something more like a Bayou blues jam than an Appalachian string band. In other words, “Sweet Virginia” crosses the same blurry boundary from country to blues that “No Expectations” had traversed, only here it occurs sequentially rather than simultaneously. Lost in the raucous romp into which the song extends from its mid-point on is a perfectly plausible modern country, 2/4 beat. To be sure, Charlie Watts’ snare shots are raspier and looser than one would expect from the average Nashville or Bakersfield drummer of the day (compare, for example, the drumming on Merle Haggard’s nearly contemporaneous [1971] cover of Roger Miller’s “Train of Life”); they might sound more at home in Memphis or New Orleans. Nevertheless, the underlying rhythm to Watts’ pattern can be traced back to any number of early country songs – again, Jimmie Rodgers provides a ready example in “Waiting for a Train,” in which the boom-chick of Watts’ pattern is ably represented by Rodgers’ guitar. If the drumming on “Sweet Virginia” leans towards blues or something more soulful than we tend to associate with country, it is merely a reminder of how interconnected country’s origins are with other “roots” genres.

Acknowledging the crossover from an ostensibly country opening into something “other” also helps explain the frequent suggestions (beginning with the members of the Rolling Stones themselves) that “Sweet Virginia” reflects the influence of Gram Parsons.15 On the surface this is a curious claim, as there are no Parsons songs that come close to sounding like this. Only “Do You Know How it Feels,” included on both the International Submarine Band’s Safe at Home and Burrito’s Gilded Palace of Sin, has any resemblance, sharing the underlying drum pattern (though much closer to Jimmie Rodgers than Charlie Watts). But that lack of a specific match serves as a reminder that Parsons’ influence was as much a concept as a sound. In this case, the blending of country and soul leads backwards more than forwards, and thus Parsons’ Cosmic American Music is not the best label for what the Stones achieve in “Sweet Virginia”: we are still in the Old Country. As much as Parsons’ idea was predicated on the common roots from which country, R&B, and rock and roll had sprung, he was aiming towards a newer synthesis. Stones tunes making up a second group from the period in question fall short of that ideal by seizing solely on the country explorations that Parsons and Richards undertook at Redlands and Nellcôte. Perhaps it is no surprise that these songs feel less like Rolling Stones songs, and more like role-playing or parody.

Deep Country: “Dear Doctor” and “Far Away Eyes”

For all of Keith Richards’ and Mick Jagger’s legitimate interest in and knowledge of country before encountering Ry Cooder and Gram Parsons, they defined themselves first as Rolling Stones – as asserted at the beginning of the chapter – through the passion for R&B and blues that they shared with Brian Jones. With a nod to the Animals, the Stones were the “blackest” of the British Invasion bands. Reflecting on blackness as an attitude and ominous demeanor (rather than race) after Altamont, Robert Christgau posited that whereas the Stones and the Beatles shared an appreciation for the “tough, joyous physicality of their Afro-American music,” the Stones “came from a darker angrier place.” But Christgau takes issue with the idea that Jagger was trying to be black:

Early analyses of their music veered between two poles – Jagger was either a great blues singer or a soulless thief – and both were wrong. Like so many extraordinary voices, Jagger’s defied description by contradicting itself. It was liquescent and nasal, full-throated and whiny. But it was not what Tom Wolfe once called it, “the voice of a bull Negro,” nor did it aspire to be. It was simply the voice of a white boy who loved the way black men sang – Jagger used to name Wilson Pickett as his favorite vocalist – but who had come to terms with not being black himself … His style was an audacious revelation. It was not weaker than black singing, just different, and the difference always involved directness of feeling.16

Christgau is speaking specifically of Jagger’s voice. While the adoption of black musical style might have harnessed the frustration of British youth in the post-war era, Jagger did not need to adopt black vocal mannerisms to get the point across. His verbal articulation may have been just as muddy as that of the Chicago bluesmen he studied as a teenager (Jagger claimed he would put his ear directly up to his record player’s speaker in order to decipher the lyrics of his favorite songs), but as Christgau avers, his was a different voice whose blurred diction was founded on “directness of feeling,” not verbal blackface.17 One glaring exception to this rule is Jagger’s rendition of Robert Wilkins’ “Prodigal Son” (a song that draws its refrain from Wilkins’ “That’s No Way to Get Along”) on Beggars Banquet. As the only song on that LP not penned by Jagger and Richards, Jagger could be heard to pay homage to Wilkins through his affected delivery.