INTRODUCTION

It is now widely accepted that variation in resistance to infectious diseases between individual hosts is largely, although not exclusively, determined by key genes. However, among parasitic infections there are still few instances where relevant genes have been unequivocally identified, and their alleles defined. In contrast to earlier views that control is based on so called ‘immune response genes’, it is now apparent that in most cases multiple genes are involved (polygenic control), and that their inter-relationships are complex (Abel and Dessein, Reference Abel and Dessein1997; Cooke and Hill, Reference Cooke and Hill2001; Quinnell, Reference Quinnell2003; Kwiatkowski, Reference Kwiatkowski2005; Vieira Benavides et al. Reference Vieira Benavides, Sonstegard, Kemp, Mugambi, Gibson, Baker, Hanotte, Marshall and Van Tassell2014).

Despite enormous efforts to identify genes that control helminth infections in domestic animals, humans and in mouse models, few clear candidate genes have emerged to-date from such studies (Williams-Blangero et al. Reference Williams-Blangero, VandeBerg, Subedi, Aivaliotis, Rai, Upadhayay, Jha and Blangero2002; Keane et al. Reference Keane, Dodds, Crawford and McEwan2008; Levison et al. Reference Levison, Fisher, Hankinson, Zeef, Eyre, Ollier, McLaughlin, Brass, Grencis and Pennock2013). However this is an important area of research, since developing more resistant breeds of domestic livestock is one of the proposed solutions for the rapidly spreading resistance to chemotherapy (Kloosterman et al. Reference Kloosterman, Parmentier and Ploeger1992; Bishop and Stear, Reference Bishop and Stear2003; Stear et al. Reference Stear, Doligalska and Donskow-Schmelter2007). Anthelmintic resistance among nematode parasites is now widespread throughout all the major pastoral regions of the world, and there are already many cases of triple resistance on farms, where none of the 3 classes of anthelmintics that dominate the markets, are effective any longer (van Wyk, Reference van Wyk, Boray, Martin and Roush1990; Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Jackson and Coop1992; Coles et al. Reference Coles, Borgsteede and Geerts1994; Kaplan, Reference Kaplan2004; Gilleard, Reference Gilleard2006; Wrigley et al. Reference Wrigley, McArthur, McKenna and Mariadas2006).

In parallel with studies in livestock, laboratory models have been used to search for candidate genes for resistance to infectious diseases, because progress can be much more rapid in these systems (Klementowicz et al. Reference Klementowicz, Travis and Grencis2012; Hurst and Else, Reference Hurst and Else2013; Levison et al. Reference Levison, Fisher, Hankinson, Zeef, Eyre, Ollier, McLaughlin, Brass, Grencis and Pennock2013). One convenient model is the mouse-Heligmosomoides bakeri system, which has been exploited effectively to identify chromosomal regions that harbour genes involved in the control of infections with this parasite (Iraqi et al. Reference Iraqi, Behnke, Menge, Lowe, Teale, Gibson, Baker and Wakelin2003; Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Iraqi, Mugambi, Clifford, Nagda, Wakelin, Kemp, Baker and Gibson2006a , Reference Behnke, Menge, Nagda, Noyes, Iraqi, Kemp, Mugambi, Baker, Wakelin and Gibson2010a ; Harris et al. Reference Harris, Pleass and Behnke2014). Major quantitative trait loci (QTL) have been described on chromosome 1 (MMU1, Hbnr1) and 17 (MMU17, Hbnr2 and Hbnr3) (Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Iraqi, Mugambi, Clifford, Nagda, Wakelin, Kemp, Baker and Gibson2006a ). These 2 chromosomal regions undoubtedly harbour the major genes for resistance in mice, and the additive effects are huge. One of the QTL (Hbnr2) on MMU17 overlies the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region; a finding that is consistent with much of the earlier work based on syngeneic and congenic mouse strains (Enriquez et al. Reference Enriquez, Brooks, Cypess, David and Wassom1988; Behnke and Wahid, Reference Behnke and Wahid1991). The QTL on MMU1 covers a relatively gene poor region and a recombination cold spot. Thus QTL mapping based on F6/7 generations of strong and poor responder mouse strains, whilst confirming the importance of this QTL, failed to refine the confidence limits relative to the earlier F2 study. Interestingly, a study using a quite different nematode parasite of rodents, Trichinella spiralis in rats concluded that there was a significant QTL for resistance on rat chromosome 9 (Suzuki et al. Reference Suzuki, Ishih, Kino, Muregi, Takabayashi, Nishikawa, Takagi and Terada2006), which is orthologous with MMU1.

Other QTL have been reported on chromosomes 5 (MMU5), 8 (MMU8) and 11 (MMU11) and these probably play a lesser, but nevertheless, important role in resistance (Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Menge, Nagda, Noyes, Iraqi, Kemp, Mugambi, Baker, Wakelin and Gibson2010a ). A further range of QTL have been described for the accompanying immune responses (Menge et al. Reference Menge, Behnke, Lowe, Gibson, Iraqi, Baker and Wakelin2003), but which genes underlie these QTL, their hierarchical relationships with one another and how their constituent alleles differ in orchestrating host-protective immunity is still far from clear. An approach to identifying the genes that contribute to each QTL is to exploit recombinant mouse strains which have been bred in a way that allows entire QTL to be switched between responder and non-responder strains or alternatively sub-sections of each QTL. The former approach has been extremely useful in elucidating the hierarchical relationships between the 3 candidate QTL in trypanosomiasis (Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Iraqi, Darvasi, Soller and Teale1997; Iraqi et al. Reference Iraqi, Clapcott, Kumar, Haley, Kemp and Teale2000) and the latter has been used to dissect the QTL regions in non-obese-diabetes (NOD) mice, seeking the underlying genes responsible for this condition (Yamanouchi et al. Reference Yamanouchi, Rainbow, Serra, Howlett, Hunter, Garner, Gonzalez-Munroz, Clark, Veijola, Cubbon, Chen, Rosa, Cumiskey, Serreze, Gregory, Rogers, Lyons, Healy, Smink, Todd, Peterson, Wicker and Santamaria2007). The NOD series of recombinant mouse strains is now extensive and fortuitously some of these are based on introgression of alleles from poor responder donors onto MMU1.

In contrast with studies on helminth resistance there has been significant progress in mapping genes for susceptibility to autoimmune diseases such as diabetes using the NOD mouse model (Makino et al. Reference Makino, Kunimoto, Muraoka, Mizushima, Katagiri and Tochino1980). By introgression of fairly short sections of the chromosomes from C57BL/10 (B10) mice (a strain that is not prone to diabetes) onto the NOD background and assessing the extent to which these alleviate, or delay the onset of diabetes, NOD researchers have been able to refine their understanding of the genes responsible for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) in NOD mice. A number of genes or regions responsible for susceptibility to type 1 diabetes have now been identified including the MHC on MMU17, and a region on MMU1, Idd5.1, which overlaps with Hbnr1 (Maier and Wicker, Reference Maier and Wicker2005; Hunter e t al. Reference Hunter, Rainbow, Plagnol, Todd, Peterson and Wicker2007; Yamanouchi et al. Reference Yamanouchi, Rainbow, Serra, Howlett, Hunter, Garner, Gonzalez-Munroz, Clark, Veijola, Cubbon, Chen, Rosa, Cumiskey, Serreze, Gregory, Rogers, Lyons, Healy, Smink, Todd, Peterson, Wicker and Santamaria2007). Of the genes contained in Idd5.1 on MMU1, those encoding the co-stimulatory molecules CTLA4 and ICOS are likely candidates for involvement in both resistance to helminth infection and susceptibility to diabetes (Redpath et al. Reference Redpath, van der Werf, Cervera, MacDonald, Gray, Maizels and Taylor2013). Indeed the molecular basis of the Idd5.1 region was confirmed to be due to a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in Ctla4 which affects the levels of expression of a ligand-independent isoform of this molecule (Araki et al. Reference Araki, Chung, Liu, Rainbow, Chamberlain, Garner, Hunter, Vijayakrishnan, Peterson, Oukka, Sharpe, Sobel, Kuchroo and Wicker2009; Stumpf et al. Reference Stumpf, Zhou and Bluestone2013).

Little is known about the response of the NOD parental mouse strain to H. bakeri, but they have been found to harbour infections for longer than BALB/c mice, although the duration of infections to complete clearance was not reported (Saunders et al. Reference Saunders, Raine, Cooke and Lawrence2007). Thus on the basis of this single report, and judging by the worm burdens in weeks 22–23, they can be considered tentatively to be intermediate-slow rather than rapid responders. It is also pertinent that this strain is not entirely inbred and that some variation in responses can be expected. In contrast, the inbred C57Bl/10 mouse is an extremely poor responder to H. bakeri (Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Lowe, Clifford and Wakelin2003), so introgression of C57Bl/10 alleles onto a NOD background would be expected to slow down further, the already slow response to H. bakeri in congenic strains, relative to pure NODs.

Here we report an experiment in which 2 NOD congenics with introgressed B10 alleles in a region of MMU1 that overlaps with the major QTL for resistance to H. bakeri were assessed for resistance to H. bakeri and compared against a strain that had B10 inserts on MMU 3, where no H. bakeri resistance genes are known to lie, and against other mouse strains known to be extremely susceptible and resistant to infection. In an effort to further refine the identity of the candidate genes underling the QTL on MMU1, we also report the outcome of an analysis of SNPs, between the original 2 strains (CBA and SWR) that were used to identify the QTL for resistance to H. bakeri and between NOD and C57BL/10 for the congenic region, using novel recently developed software.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites

Mice were infected with the trichostrongyloid intestinal nematode H. bakeri. Until recently, this species was known as Heligmosomoides polygyrus and H. polygyrus bakeri (Cable et al. Reference Cable, Harris, Lewis and Behnke2006; Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Menge and Noyes2009; Behnke and Harris, Reference Behnke and Harris2010). In older literature this parasite has also been referred to as Nematospiroides dubius (Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Keymer and Lewis1991). We used a repeated infection protocol described by Iraqi et al. (Reference Iraqi, Behnke, Menge, Lowe, Teale, Gibson, Baker and Wakelin2003) and characterized immunologically by Behnke et al. (Reference Behnke, Lowe, Clifford and Wakelin2003), based on the administration of 125 infective larvae (L3) once weekly for 7 weeks. In fact in this case the protocol was extended to week 11 for reasons explained below in the ‘Results’ section. The methods used for infection, and the accompanying changes in worm burdens and fecal egg counts (FEC) have all been thoroughly documented in earlier publications (Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Lowe, Clifford and Wakelin2003, Reference Behnke, Mugambi, Clifford, Iraqi, Baker, Gibson and Wakelin2006b ).

Mice

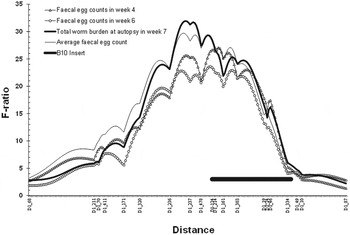

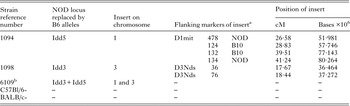

NOD congenics were provided by Linda Wicker (University of Cambridge) and were imported from the Taconic Farms in the USA to the ILRI by air. We used 3 strains, as shown in Table 1 (Further details of strains can also be found in Hunter et al. Reference Hunter, Rainbow, Plagnol, Todd, Peterson and Wicker2007 and Yamanouchi et al. Reference Yamanouchi, Rainbow, Serra, Howlett, Hunter, Garner, Gonzalez-Munroz, Clark, Veijola, Cubbon, Chen, Rosa, Cumiskey, Serreze, Gregory, Rogers, Lyons, Healy, Smink, Todd, Peterson, Wicker and Santamaria2007). The position of the B10 inserts was obtained from http://www.t1dbase.org/page/DrawStrains and details of the markers (genetic distances in cM and physical position on the chromosomes in millions of base-pairs) from the Mouse Genetics Database (http://www.informatics.jax.org/). Strain 1098 (Idd3 mice) which has B10 alleles on MMU3 (insert length is 0·808 Mb; no response genes were identified on MMU3 in earlier work) acted as our NOD control strain, and we predicted that infections in this strain should be rejected more quickly than in the other 2 strains. Strain 1094 (Idd5 mice) has a B10 insert that is between 19·4 and 28·3 Mb in size bounded by markers with NOD alleles D1Mit478 (Chr1:51 981 710) and D1mit134 (Chr1:80 264 451). If the genes in the B10 interval are involved in resistance to H. bakeri we would expect infections in this strain to be longer lasting. Figure 1 shows the exact position of the B10 insert superimposed on Hbnr1 the QTL for resistance to H. bakeri, taken from Behnke et al. (Reference Behnke, Iraqi, Mugambi, Clifford, Nagda, Wakelin, Kemp, Baker and Gibson2006a ). Strain 6109 (which has both Idd3 and Idd5 inserts) was expected to behave much like strain 1094 retaining worms longer than strain 1098. Our experiment was further controlled by the inclusion of C57Bl/6 (B6) mice, which we expected to accumulate heavy worm burdens under the repeated infection protocol and by BALB/c mice which are intermediate responders, and would be expected to reject worms more rapidly than NOD mice (Saunders et al. Reference Saunders, Raine, Cooke and Lawrence2007). We began the experiment with 15 individuals of each strain other than B6 (n = 16), and lost two B6s and one 6109 mouse before necropsy.

Fig. 1. The QTL for total worm counts and FEC in weeks 4 and 6 and averaged, on chromosome 1, identified in Behnke et al. (Reference Behnke, Iraqi, Mugambi, Clifford, Nagda, Wakelin, Kemp, Baker and Gibson2006a ), and showing the location and length of the inserts from B10 mice onto the NOD background. Three of the markers (D1mit 124, 132 and 134) were not used in the original QTL study but together with D1mit 478 are the flanking markers for the B10 insert. D1mit 132 and 134 are not illustrated on the figure to avoid overlaying markers on the x-axis, but they are located just distal to D1mit 334 and proximal to D1mit 49.

Table 1. Strains of mice used in the current work and their characteristics

a The flanking markers differ between the 2 strains of mice, B6 (C57BL/10) and NOD.

b Position of insert on chromosome 1 is exactly the same as that for strain1094 and that for chromosome 3 as in strain 1098.

PubMed search for candidate genes in the B10 insert region

The database PubMed was searched to obtain the number of titles or abstracts that contained the Ensembl ‘External ID’ and any of the words ‘Helminth’, ‘Heligmosomoides’, ‘Diabetes’ or ‘Inflammation’ (a list of the genes is included in IDD5 Supplementary data.xls). It is possible that any polymorphism that affects gene function will affect the development of both diabetes and helminth infection, since both are in some degree inflammatory conditions.

Annotated gene list

An annotated list of all SNP between C57BL/6 and NOD/LtJ in the insert region in Ensembl v67 (NCBI37) was obtained from Biomart. Gene descriptions and external IDs were added with a local Perl script. Counts of hits for gene names and Heligmosomoides were also obtained with a different local Perl script that used the National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, USA (NCBI) E-utilities API to access PubMed (Both local Perl scripts are available from the authors). Polyphen annotation for non-synonymous SNP was obtained using a local Perl script to submit jobs to the Polyphen website (Ramensky et al. Reference Ramensky, Bork and Sunyaev2002). This analysis was also extended to compare CBA mice with SWR in the entire QTL region originally described for F2 and F6/7 crosses of these 2 strains (Iraqi et al. Reference Iraqi, Behnke, Menge, Lowe, Teale, Gibson, Baker and Wakelin2003; Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Iraqi, Mugambi, Clifford, Nagda, Wakelin, Kemp, Baker and Gibson2006a ).

Statistical analysis

Where appropriate, data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). For worm counts and FEC raw data were transformed (log10(x+10) and log10(x+25), respectively) to normalize the distribution. Tests of significance were mostly on transformed values, but in the text we refer to geometric means (GM, calculated by back transformation and adjustment by subtraction of 10 or 25, respectively). The GMs for FEC are in units of eggs per gram and for worm burdens as worm counts.

FEC were analysed by repeated measures analysis of variance (rmGLM in SPSS for Windows, release 16.0.0) with time as the within subject factor and strain as the between subject factor. When the data did not meet the requirement of sphericity (Mauchly's test of sphericity) we employed the Huynh–Feldt adjustment in degrees of freedom to calculate probability levels, erring on the side of caution. Worm burden data were analysed by 1-way GLM in SPSS, with worm burden (transformed by log10(number of worms+10)) as the dependent variable and strain as the explanatory factor. In one case we used the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test in SPSS because the data did not conform to the requirements of normality and could not be suitably transformed. P<0·05 was taken as the cut-off for significance.

RESULTS

Fecal egg counts

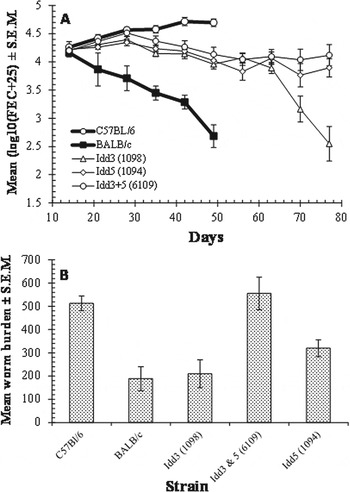

Figure 2A shows the mean FEC recorded week by week for each group of mice. B6 mice showed consistently increasing FEC, with EPG (eggs per gram of feces) values rising steadily from week 2 onwards. In contrast in BALB/c mice FEC declined consistently from week 2, both much as expected from previous work (Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Mugambi, Clifford, Iraqi, Baker, Gibson and Wakelin2006b ). All 3 recombinant groups showed intermediate FEC at this time, in agreement with Saunders et al. (Reference Saunders, Raine, Cooke and Lawrence2007), but by day 42 no clear separation between these strains was evident. Therefore, the experiment was continued for longer, beyond day 43, when normally we would have ended such experiments. However, because the FEC were rising continuously in B6 mice, and threatening their survival, for humane reasons we necropsied both control groups on days 51–53. No statistical analysis is required to support the divergent FEC with time in the 2 control groups representing slow/poor responders (B6) and intermediate/fast responders (BALB/c), which by week 7 differed by more than 2 orders of magnitude.

Fig. 2. (A) FEC during the course of the experiment by experimental group, and (B) worm burden at necropsy. For BALB/c and C57Bl/6 mice this was day 51–53, and for the congenic strains it was day 77.

The figure shows that in weeks 10 and 11, FEC began to drop sharply in strain 1098, in which the B10 insertion was on MMU3, a chromosome that has not been identified as bearing genes involved in genetic resistance to H. bakeri. However, strains 6190 and 1094, both of which had B10 inserts in the QTL region on MMU1, continued to produce high levels of parasite eggs, suggesting that protective immunity in these strains was slower to develop. Statistical analysis by rmGLM, incorporating all the days on which FEC had been conducted, indicated that FEC among these 3 groups differed significantly (F 2,39 = 4·2, P = 0·022) and post hoc analysis indicated that strain 1098 differed significantly from strains 6109 but that strain 1098 could not be separated clearly from strain 1094.

However, the data were heavily biased by the first 7 weeks when the strains had overlapping and similar mean FEC. Confining the analysis to the last 4 weeks (days 56, 63, 70 and 77) when strains began to diverge, again gave a highly significant main effect of strain (F 2,39 = 5·0, P = 0·012) and indicated that the strains diverged significantly (2-way interaction time * strain, F 4·2,82·1 = 10·6, P<0·001). Post hoc tests (LSD) indicated that FEC in strain 1098 were significantly different from those of strain 1094 (P = 0·021) and of strain 6109 (P = 0·005).

Worm burdens

BALB/c and the C57Bl/6 mice, which acted as responder and non-responder controls, respectively, were culled in week 8 on days 51–53 because some of the C57Bl/6s were beginning to lose condition through having developed very high worm burdens at this time (Fig. 2B and Table 2), ranging from 278 to 682 worms. BALB/c were also culled at this time to enable comparison, their FEC on average being extremely low, but as it turned out whilst, most had rejected their worms (10 had worm burdens of fewer than 50 worms), there were some with surprisingly high worm burdens, including 3 worm burdens of 450, 549 and 603). However, FEC even in these animals were low (600, 3600 and 1800, respectively) indicating that their worm burdens were mostly non- or low-fecund, and likely to be rejected within a few more days, had the experiment been continued for longer. This variation in BALB/c mice is consistent with earlier work where they have been found to rank as intermediate responders (Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Mugambi, Clifford, Iraqi, Baker, Gibson and Wakelin2006b ). There was a highly significant difference in worm burdens between these 2 strains at necropsy (Mann–Whitney U test, 1-tailed predicting higher worm burdens in C57Bl/6 mice, z = 3·45, P<0·001).

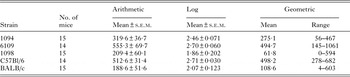

Table 2. Arithmetic, log and geometric means of worm burdens at necropsy of the 5 strains of mice utilized in the experiment

For statistical analysis see text.

Figure 2B and Table 2 show also that among the NOD congenics, strain1098 had lower worm burdens than the other strains. Confining analysis to the 3 congenic groups gave a highly significant effect of strain (1-way GLM with strain on log10(worm burden+10), F 2,41 = 11·074, P<0·001) and post hoc tests (LSD) indicated that strain 1098 differed significantly from strain 1094 (P = 0·002) and from strain 6109 (P<0·001), but there was no difference between strains 1094 and 6109.

PubMed search for candidate genes in the B10 insert region

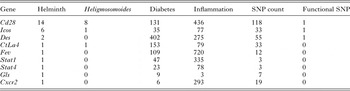

There were 9 genes associated with ‘Helminth’, of which 3 were also associated with ‘Heligmosomoides’ (Table 3) and 42 were associated with ‘Diabetes’ (‘IDD5 Supplementary data.xls’). CD28 (61Mb) had the highest number of PubMed hits for ‘Helminth’ and ‘Heligmosomoides’.

Table 3. Counts of hits in PubMed for genes in the region associated with the 4 search terms and numbers of SNP associated with each gene

SNP that have different annotations on different transcripts will have been counted more than once.

Functional SNP had one of the following annotations: INTRONIC&SPLICE_SITE, NON_SYNONYMOUS_CODING, SYNONYMOUS_CODING&SPLICE_SITE, NMD_TRANSCRIPT&INTRONIC&SPLICE_SITE, STOP_GAINED, SYNONYMOUS_CODING&NMD_TRANSCRIPT.

SNP analysis

Ensembl variation 67 contains 17 834 SNP within 284 genes in the region between D1Mit478 (Chr1:51 981 710) and D1mit134 (Chr1:80 264 451) when comparing mouse strain C57BL/6 with NOD/LtJ (‘IDD5 Supplementary data.xls’). There were only 2 positions in these genes where C57BL/6J differ from C57BL/10 so C57BL/6 should be a good proxy for C57BL/10; however, sequence coverage for C57BL/10 may be limited. The only obvious loss of function polymorphism amongst the SNP was a premature stop codon in Gm5528 at 72 Mb, but this gene is annotated in Ensembl as a processed pseudogene so the premature stop codon is unlikely to have any functional consequences. There were 115 non-synonymous SNP within 34 genes so these SNP alone are not very useful for prioritizing genes and therefore we combined the SNP data with the lists of genes with known associations with helminths.

The genes with literature associations with ‘Helminths’ and ‘Heligmosomoides’ were scanned for ‘interesting’ SNP (Functional SNP in Table 3). These were classified as the SNP that were most likely to have functional consequence (See Table 3) although almost any SNP could have important consequences for gene expression. Cd28 contained 63 unique SNP (the 118 SNP in Table 3 includes the SNP in multiple transcripts with different annotations) although few of these had support from multiple sources. One SNP was within a splice site, which could have a significant impact on function. Others were in regions that could affect expression or splicing but their potential effects on function are difficult to predict and no studies of the effect of these SNP have been published. Icos (Cd278) had 31 SNP of which 1 was non-synonymous although this was predicted to be benign by Polyphen (Ramensky et al. Reference Ramensky, Bork and Sunyaev2002; Adzhubei et al. Reference Adzhubei, Schmidt, Peshkin, Ramensky, Gerasimova, Bork, Kondrashov and Sunyaev2010). In the case of Ctla4 (Cd152) none of the 26 SNP could cause a structural difference in the gene product but all could potentially cause differences in expression. There was a single SNP in an intronic splice site in Des, the gene for desmin which is a subunit of the intermediate filaments in the sarcomeres of muscle tissue.

Genes in the QTL region for which no publications were found were also reviewed. The SNP with the greatest potential structural impact are those that cause nonsense mediated decay (NMD). There were 300 SNP that could cause NMD in 15 different genes; the biotype of all these genes was ‘nonsense mediated decay’. For all of these genes the NMD attribute was associated with just one of several transcripts.

Haplotype structure of chromosome 1 for CBA and SWR

The QTL on MMU1 in the F6 hybrids lies between D1Mit171 (36 800 667) and D1Mit46 (75 569 122) (Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Iraqi, Mugambi, Clifford, Nagda, Wakelin, Kemp, Baker and Gibson2006a ). Therefore, it is possible that the QTL gene/s is outside the NOD congenic region (Table 1). We have previously used haplotypes from the Perlegen mouse SNP to identify candidate genes within QTL regions (Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Menge, Nagda, Noyes, Iraqi, Kemp, Mugambi, Baker, Wakelin and Gibson2010; Goodhead et al. Reference Goodhead, Archibald, Amwayi, Brass, Gibson, Hall, Hughes, Limo, Iraqi, Kemp and Noyes2010) and here we used the same approach to identify genes that were on different haplotypes between CBA and SWR mice within the MMU1 QTL. A list of haplotypes where CBA and SWR mice have different alleles and genes within, proximal or distal to those haplotypes is shown in ‘IDD5 Supplementary data.xls’. The object of this analysis was to eliminate genes where both strains of interest have the same haplotype and this strategy can dramatically reduce gene lists (Behnke, et al. Reference Behnke, Menge, Nagda, Noyes, Iraqi, Kemp, Mugambi, Baker, Wakelin and Gibson2010a ; Goodhead, et al. Reference Goodhead, Archibald, Amwayi, Brass, Gibson, Hall, Hughes, Limo, Iraqi, Kemp and Noyes2010). On this occasion the number of candidate genes in the QTL region was reduced from 453 to 326 by this approach. A search of PubMed Titles and Abstracts with these 326 gene names and the same keywords as described above did not identify any genes with published associations with helminths or Heligmosomoides beyond those already described within the NOD congenic region. CD28, Icos and Ctla4 (see above) had different haplotypes between CBA and SWR mice; however, both strains had different haplotypes from NOD/LtJ.

DISCUSSION

Despite the relatively slow response of NOD mice to primary infection with H. bakeri (Saunders et al. Reference Saunders, Raine, Cooke and Lawrence2007) and to repeated infections, this experiment has clearly shown that when the time frame under the latter protocol was extended beyond that normally used under repeated infection regimens (6 weeks), rejection of worms did occur. However, it was further slowed when NOD alleles of genes mapping in the region between D1Mit478 (Chr1:51 981 710) and D1mit134 (Chr1:80 264 451) on MMU1 were replaced by those from the very poor responder strain C57Bl/10. In this experiment the slower response was evident in 2 congenic strains and was supported both by their FEC and by worm burdens at necropsy. This is the first experimental study to show unequivocally that the expulsion of H. bakeri worms from mice can be delayed by alleles of genes mapping in this region of mouse chromosome 1. Moreover, it is highly pertinent that this region maps well within the confidence intervals of the H. bakeri resistance QTL (Hbnr1) described in Behnke et al. (Reference Behnke, Iraqi, Mugambi, Clifford, Nagda, Wakelin, Kemp, Baker and Gibson2006a ). Since the B10 insert is relatively short, it now allows our search for resistance genes to be focused on a few candidates within this region.

Our PubMed search identified Cd28, Icos (Cd278) and Ctla4 (Cd152) as being the genes most linked in the literature with helminth infections. The gene products of Icos and Ctla4 are both members of the CD28 superfamily of costimulatory surface receptor molecules found on T cells which participate in Toll pathways and are important in expansion of Foxp3+T reg cells (CD278 in mucosal tissues), driving Th2 responses (CD152 in lymphoid tissues) and in downregulating (CD152) the signal arising from the MHC and T-cell receptor interaction (Redpath et al. Reference Redpath, van der Werf, Cervera, MacDonald, Gray, Maizels and Taylor2013). CD152, like CD28, interacts with B7 (CD80 and CD86) and has far greater affinity for the CD80/86 ligands, whilst CD278 interacts with the ICOS ligand, CD275. Functional CD80/86 and CD152 are particularly important in driving Th2, IL4-dependent antibody responses (Lu et al. Reference Lu, di Zhou, Chen, Moorman, Morris, Finkelman, Linsley, Urban and Gause1994; Greenwald et al. Reference Greenwald, Lu, Halvorson, Zhou, Chen, Madden, Perrin, Morris, Finkelman, Peach, Linsley, Urban and Gause1997), although CD28 is not, since in CD28 knockout mice the IgG1 and IgE responses to H. bakeri are not inhibited (Gause et al. Reference Gause, Chen, Greenwald, Halvorson, Lu, di Zhou, Morris, Lee, June, Finkelman, Urban and Abe1997). Blockade of the B7 (CD80/86)/CTLA4 (CD152) interaction did not impair the expulsion of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (Harris et al. Reference Harris, Peach and Ronchese1999) nor was acquired protective immunity to H. bakeri weakened in mice with antibody blocked CD28 and CTLA4 (CD152)-B7 (CD80/86) interactions (Gause et al. Reference Gause, Lu, Zhou, Chen, Madden, Morris, Linsley, Finkelman and Urban1996). CD28 knockout mice resist challenge effectively, as do also CD80/86 knockouts (Ekkens et al. Reference Ekkens, Liu, Liu, Foster, Whitmire, Pesce, Sharpe, Urban and Gause2002) and their IL-4 secretion by CD4+T cells, IgG1 and IgE responses to infection are unaffected (Gause et al. Reference Gause, Chen, Greenwald, Halvorson, Lu, di Zhou, Morris, Lee, June, Finkelman, Urban and Abe1997). Nevertheless, acquired protective immunity to H. bakeri is known to be highly dependent on IgG1 antibodies (Pritchard et al. Reference Pritchard, Williams, Behnke and Lee1983; Harris et al. Reference Harris, Spoerri, Schopfer, Nembrini, Merky, Massacand, Urban, Lamarre, Burki, Odermatt, Zinkernagel and Macpherson2006, Reference Harris, Pleass and Behnke2014; McCoy et al. Reference McCoy, Stoel, Stettler, Merky, Fink, Senn, Schaer, Massacand, Odermatt, Oettgen, Zinkernagel, Bos, Hengartner, MacPherson and Harris2008; Liu, et al. Reference Liu, Kreider, Bowdridge, Liu, Song, Gaydo, Urban and Gause2010), so polymorphisms in these genes with resultant differences in gene products affecting their roles in the immune response, may well explain some of the genetic differences between strong and weak responder mouse strains associated with the QTL on MMU1 and the results of the current experiment. It may be relevant that most of the experimental work with knockouts and antibody blocked responses has been carried out in immunized animals very soon after challenge (usually about day 10), when despite the absence of fecund adults, many worms are known to be still alive but arrested in the mucosal tissues (Behnke and Parish, Reference Behnke and Parish1979) and in mouse strains that rank as either poor or intermediate responders (Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Mugambi, Clifford, Iraqi, Baker, Gibson and Wakelin2006b ). It is therefore conceivable that SNP in this family of genes still play some decisive roles in longer term, repeated infection experiments in which differences in immune responsiveness become apparent only after several months of repeated challenge.

Consistent with the above, the SNP analysis did not reveal any obvious SNP that might be unequivocally linked to resistance to H. bakeri. In Cd28 there was only one SNP that might have affected function, but Cd28 had the strongest association with ‘Heligmosomoides’ in the literature. Icos only had one non-synonymous SNP that was probably benign. Although ICOS blockade has not been tested in H. bakeri, blockade in mice infected with T. spiralis does not delay worm expulsion (Scales et al. Reference Scales, Ierna, Gutierrez-Ramos, Coyle, Garside and Lawrence2004). In the case of Ctla4, no structural changes were predicted but many possible regulatory consequences are possible. However, there is a known splice site SNP 77 in Ctla4 exon 2 that is not present in the Biomart data set (http://www.biomart.org/martservice.html). This SNP has been shown to be the QTL SNP for the IDD5.1 diabetes QTL (Araki et al. Reference Araki, Chung, Liu, Rainbow, Chamberlain, Garner, Hunter, Vijayakrishnan, Peterson, Oukka, Sharpe, Sobel, Kuchroo and Wicker2009), the A allele of this SNP derived from C57BL/10 mice being associated with higher expression of the ligand-independent isoform of CTLA4 (liCTLA4). Ectopic expression of liCTLA4 in T cells limits T-cell activation, cytokine production and proximal TCR signalling and these effects appear to be protective against type 1 diabetes. Given the demonstrated effect of this SNP on immune function it is perhaps the best candidate SNP. The Cd28, Icos, Ctla4 cluster is clearly subject to a publication bias in favour of known immune response genes; however, in support of a role for these genes in protective immunity to helminth infections, a hypothesis free genome wide survey for SNP associated with helminth infections in humans identified Cd28 and Ctla4 as being independently subject to selection for resistance to helminths (Fumagalli et al. Reference Fumagalli, Pozzoli, Cagliani, Comi, Bresolin, Clerici and Sironi2010). The haplotype structure of CBA and SWR genotypes was also markedly different in this region of MMU1, although distinct from that of the NOD mice, and it is possible that one or more combinations of SNP in this region of MMU1, perhaps in the regulating regions rather than structural, play a decisive role in determining the responder status of mice subjected to repeated infection protocols.

An increase in desmin expression has been linked to fibrosis associated with Trichinella spp. and Fasciola hepatica infections and there is also a SNP in an intronic splice site in this gene (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Nagano and Takahashi2008; Golbar et al. Reference Golbar, Izawa, Juniantito, Ichikawa, Tanaka, Kuwamura and Yamate2013). However, at this stage it is still not clear whether increased fibrosis is linked to either of the alleles expressing the different SNP, or how they may be involved in worm expulsion from the intestine. However, fibrosis is involved in the trapping of larvae during their development in the outer mucosa, under the serosa (Liu, Reference Liu1965; Jones and Rubin, Reference Jones and Rubin1974; Behnke Parish, Reference Behnke and Parish1979), and hence variation in the fibrotic response is likely to contribute to response phenotype. Indeed, the granulomatous response (which involves fibrosis) to repeated H. bakeri infections, as quantified by visual assessment using a score ranging from 0 to 4, was linked to QTL on chromosomes 4, 8, 11, 13 and 17, but not on chromosome 1 (Menge et al. Reference Menge, Behnke, Lowe, Gibson, Iraqi, Baker and Wakelin2003; Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Menge, Nagda, Noyes, Iraqi, Kemp, Mugambi, Baker, Wakelin and Gibson2010). Moreover, at 75·356×106 bp Des is located at the extreme distal end of the QTL region, and is therefore unlikely to be the key gene in the QTL region responsible for response phenotype to H. bakeri infection.

It is also possible that the QTL may be attributable to one of the genes in the region for which there are no publications, and therefore genes with structural polymorphism were reviewed. However, among the 300 SNP that were identified, the NMD attribute was associated with just one of several transcripts and therefore could simply be an indicator of an erroneous gene model or even if that transcript was affected it is hard to predict what if any effect NMD would have on phenotype. Nothing more is known about the role of these genes, or the consequences of NMD to their structures, for resistance to H. bakeri.

Similarly the biotype for Gm5528 is ‘processed pseudogene’ and although BioGPS (http://biogps.org/#goto=welcome) shows that it is most highly expressed in dendritic plasmacytoid B220 cells and haemopoietic stem cells and almost nowhere else, it seems unlikely to have a functional role (Su et al. Reference Su, Wiltshire, Batalov, Lapp, Ching, Block, Zhang, Soden, Hayakawa, Kreiman, Cooke, Walker and Hogenesch2004). Other genes which are known to play important roles in immune responses such as Stat1 and Stat4 were within the region and had literature associations with helminths but not Heligmosomoides. However, these genes only had potentially regulatory SNP rather than structural SNP so the effect of these SNP on gene function is harder to predict.

Finally, based on the available evidence from the present study Cd28 and Ctla4 are perhaps the best candidate QTL genes within the region and could control the difference between both NOD and C57BL/6 and between SWR and CBA mice. In addition to the evidence presented above they are also close to the peak of the QTL for FEC, adult worm specific IgG1 antibody (IgG-Ad) and packed cell volume in week 6 (PCV6), which is around 52 Mb (Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Iraqi, Mugambi, Clifford, Nagda, Wakelin, Kemp, Baker and Gibson2006a ). However, it should be emphasized that the available evidence is not comprehensive at this stage and other genes could be responsible for or contribute to the observed differences in response. Furthermore, the plots of F ratios across the QTL region have multiple peaks for some phenotypes and different peaks for different phenotypes so there may well be more than one QTL gene within the region (Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Iraqi, Mugambi, Clifford, Nagda, Wakelin, Kemp, Baker and Gibson2006a ).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182014001644.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Bob King for organizing the mouse facilities at ILRI for this work, to Linda Wicker for supplying the recombinant NOD strains and to Dan Rainbow for advice about the known gene loci within the B10 insert on MMU1 in congenic NOD mice.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This work was partly supported by The Wellcome Trust (grant number GR066764MA).